Gender Differences in Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Its Association with Obesity Among Korean Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Study Variables

2.2.1. Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods

2.2.2. Dietary Assessment

2.2.3. General Characteristics and Obesity Variables

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics by Gender

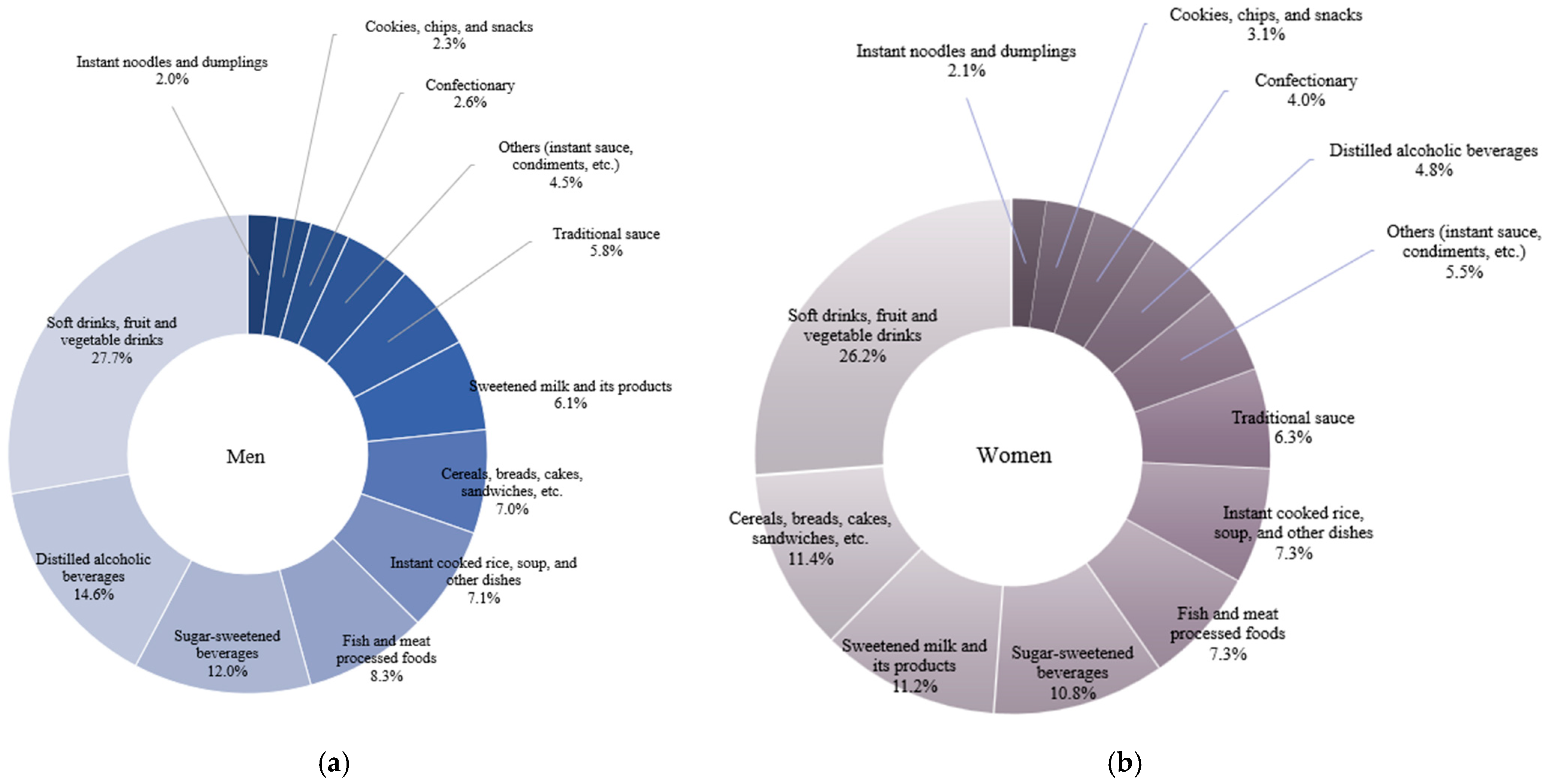

3.2. Status of Ultra-Processed Food Consumption by Gender

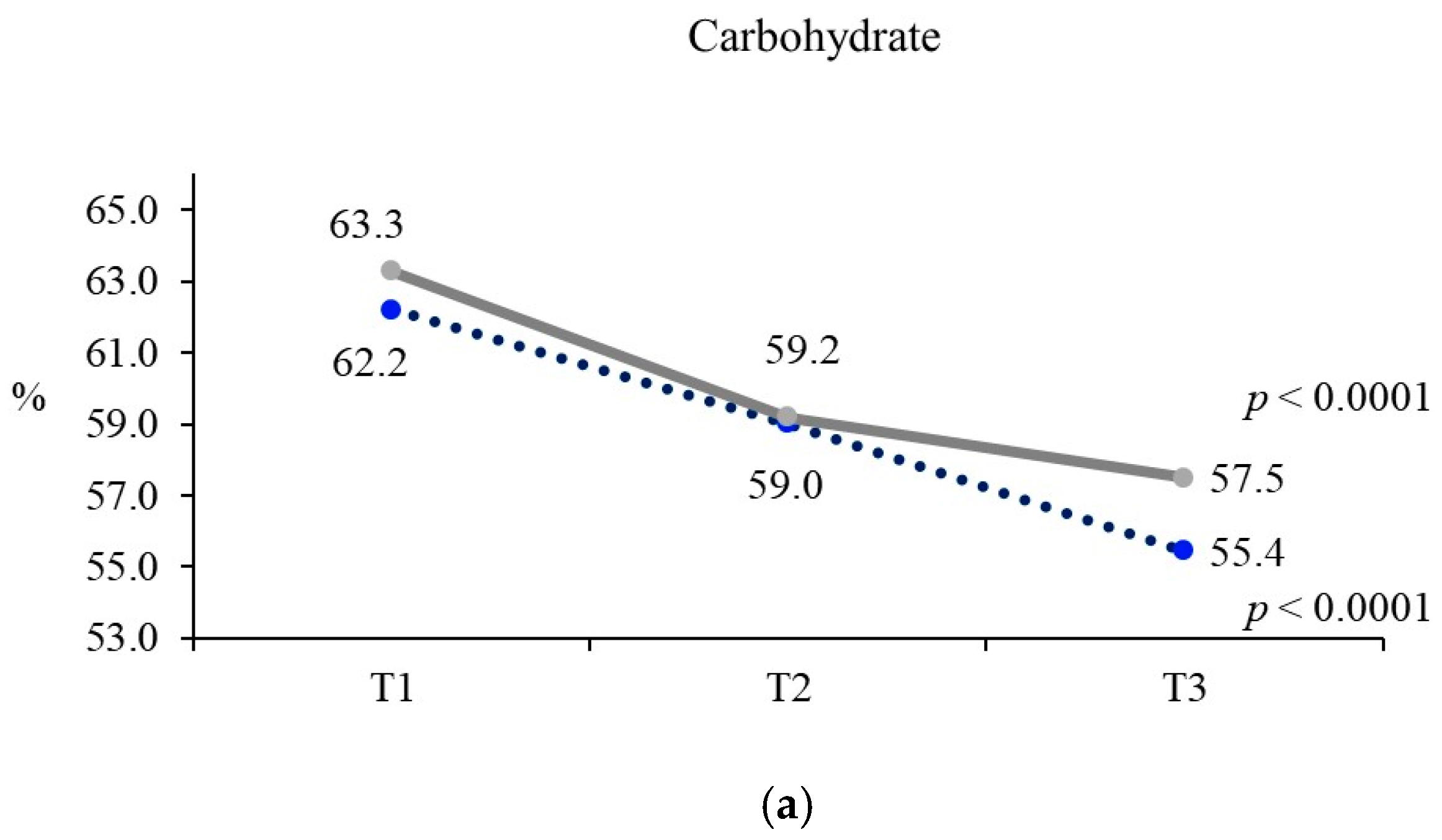

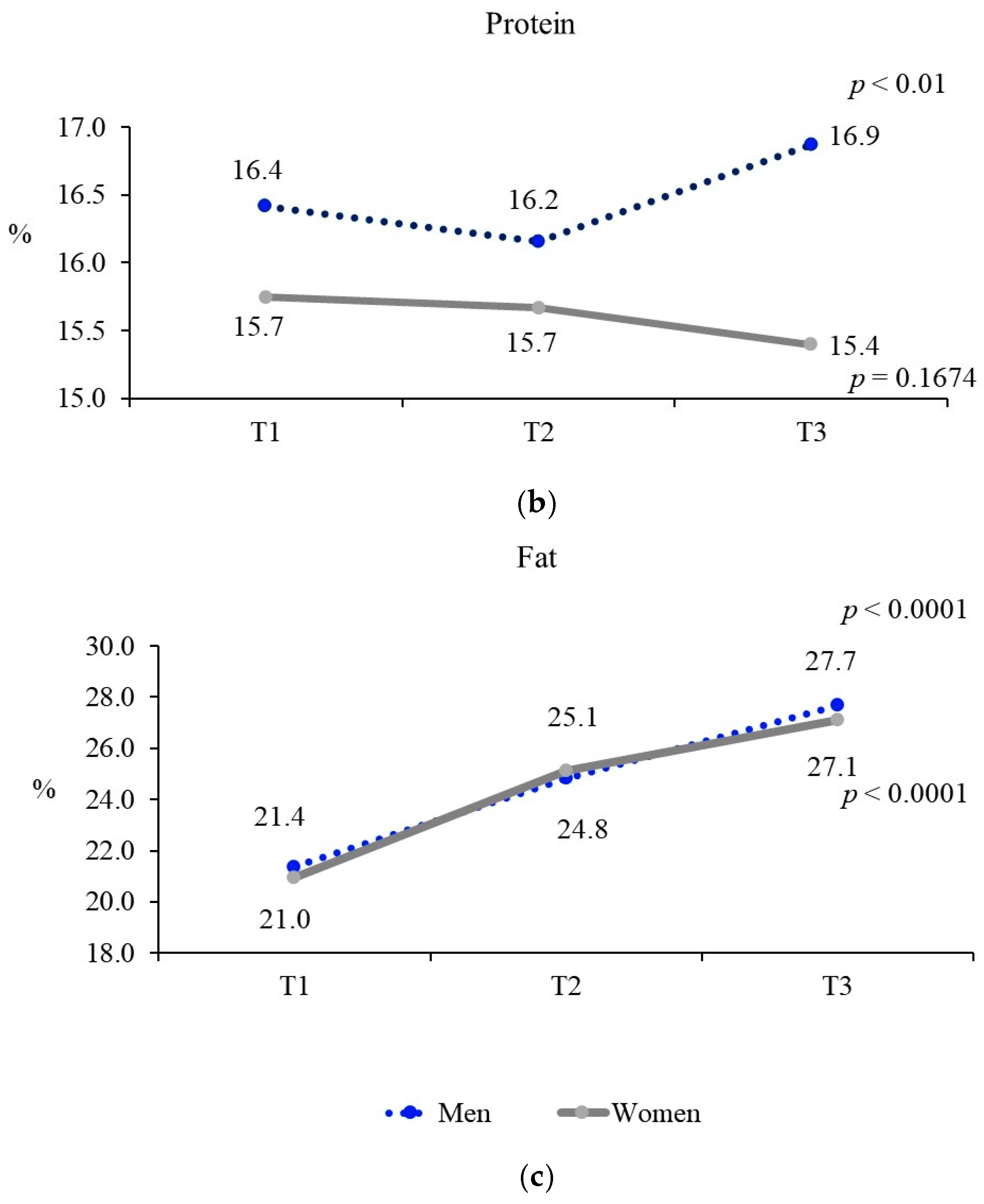

3.3. Nutrient Intake According to Ultra-Processed Food Consumption by Gender

3.4. Obesity Prevalence According to Ultra-Processed Food Consumption by Gender

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Canella, D.S.; Levy, R.B.; Martins, A.P.B.; Claro, R.M.; Moubarac, J.C.; Baraldi, L.G.; Cannon, G.; Monteiro, C.A. Ultra-processed food products and obesity in Brazilian households (2008–2009). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Moubarac, J.C.; Levy, R.B.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Jaime, P.C. The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Levy, R.B.; Claro, R.M.; Castro, I.R.R.; Cannon, G. A new classification of foods based on the extent and purpose of their processing. Cad. Saúde Pública 2010, 26, 2039–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.B.; Moubarac, J.C.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Rauber, F.; Khandpur, N.; Cediel, G.; Neri, D.; Martinez-Steele, E.; et al. Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, J.S.; Shim, S.Y.; Cha, H.J.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.C. Socioeconomic characteristics and trends in the consumption of ultra-processed foods in Korea from 2010 to 2018. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, A.W.; Kim, W.K. The food and nutrient intakes from daily processed food in Korean adults: Based on the 6th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data (2013~2015). J. Nutr. Health 2019, 52, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.; Gamage, E.; Du, S.; Ashtree, D.; McGuinness, A.J.; Gauci, S.; Baker, P.; Lawrence, M.; Rebholz, C.M.; Srour, B.; et al. Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: Umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses. BMJ 2024, 384, e077310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juul, F.; Steele, E.M.; Parekh, N.; Monteiro, C.A.; Chang, V.W. Ultra-processed food consumption and excess weight among US adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 120, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccio, M.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Costanzo, S.; De Curtis, A.; Persichillo, M.; Sofi, F.; Cerletti, C.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L. Ultra-processed food consumption is associated with increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the Moli-sani Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Ryu, S.; Kim, R.; Shin, M.J.; Oh, H. Ultra-processed food intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in Korean adults. J. Nutr. 2024, 154, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Khandpur, N.; Desjardins, C.; Wang, L.; Monteiro, C.A.; Rossato, S.L.; Fung, T.T.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C.; Rimm, E.B.; et al. Ultra-processed food consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: Three large prospective U.S. cohort studies. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 1335–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, N.; Du, S.; Bernard, L.; Kim, H.; Matsushita, K.; Rebholz, C.M. Ultra-processed food consumption and risk of incident hypertension in US middle-aged adults. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e035189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chernet Elias, A.A.; Chernet, A.; Tagese, Y.; Daniel, G. Prevalence of overweight/obesity and its association with fast food consumption among adolescents in Southern Ethiopia, 2022: A community-based cross-sectional study. Front. Nutr. 2025, 11, 1475116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahzari, M.; Mamun, A. Does Consumption of Refined Carbohydrates Predict the Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Rom. J. Diabetes Nutr. Metab. Dis. 2020, 27, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonestedt, E.; Øverby, N. Carbohydrates—A scoping review for Nordic Nutrition Recommendations. Food Nutr. Res. 2023, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breeze, P.; Sworn, K.; McGrane, E.; Abraham, S.; Cantrell, A. Relationships between sodium, fats and carbohydrates on blood pressure, cholesterol and HbA1c: An umbrella review of systematic reviews. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health. 2024, 21, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.S. Ultra-processed food consumption and obesity: A narrative review of their association and potential mechanisms. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2025, 34, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, K.D.; Ayuketah, A.; Brychta, R.; Cai, H.; Cassimatis, T.; Chen, K.Y.; Chung, S.T.; Costa, E.; Courville, A.; Darcey, V.; et al. Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: An inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 67–77.e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monda, A.; de Stefano, M.I.; Villano, I.; Allocca, S.; Casillo, M.; Messina, A.; Monda, V.; Moscatelli, F.; Dipace, A.; Limone, P.; et al. Ultra-processed food intake and increased risk of obesity: A narrative review. Foods 2024, 13, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordova, R.; Kliemann, N.; Huybrechts, I.; Rauber, F.; Vamos, E.P.; Levy, R.B.; Wagner, K.-H.; Viallon, V.; Casagrande, C.; Nicolas, G.; et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods associated with weight gain and obesity in adults: A multi-national cohort study. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 5079–5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauber, F.; Chang, K.; Vamos, E.P.; da Costa Louzada, M.L.; Monteiro, C.A.; Millett, C.; Levy, R.B. Ultra-processed food consumption and risk of obesity: A prospective cohort study of UK Biobank. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 2169–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauber, F.; Steele, E.M.; Louzada, M.L.d.C.; Millett, C.; Monteiro, C.A.; Levy, R.B. Ultra-processed food consumption and indicators of obesity in the United Kingdom population (2008–2016). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. 2023 National Health Statistics: Prevalence of Obesity; Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency: Osong, Republic of Korea, 2023; Available online: https://www.index.go.kr/unity/potal/main/EachDtlPageDetail.do?idx_cd=2705 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Pi-Sunyer, F.X. The medical risks of obesity. Obes. Surg. 2002, 12, 6S–11S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordeiro, J.; Mosca, S.; Correia-Costa, A.; Ferreira, C.; Pimenta, J.; Correia-Costa, L.; Barros, H.; Postolache, O. The association between childhood obesity and cardiovascular changes in 10 years using special data science analysis. Children 2023, 10, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.; Gastaldelli, A.; Yki-Järvinen, H.; Scherer, P. Why does obesity cause diabetes? Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.J.; Qin, X.Z.; Zhou, J.; He, B.F.; Shrestha, S.; Zhang, J.; Hu, W.P. Adipocyte dysfunction promotes lung inflammation and aberrant repair: A potential target of COPD. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1204744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sines, J.; Cai, K.; Cashman, B.; Abbott, P.; Zengin, A.; Manolios, N.; Wong, P. The burden of rheumatologic disease in aboriginal and torres strait islander Australians. Intern. Med. J. 2024, 54, 1603–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandacoomarasamy, A.; Caterson, I.; Sambrook, P.; Fransen, M.; March, L. The impact of obesity on the musculoskeletal system. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle, E.E.; Thun, M.J. Obesity and cancer. Oncogene 2004, 23, 6365–6378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.T.; Minh Nguyet, N.T.; Nga, V.T.; Thai Lien, N.V.; Vo, D.D.; Lien, N.; Nhu Ngoc, V.T.; Son, L.H.; Le, D.H.; Nga, V.B.; et al. An update on obesity: Mental consequences and psychological interventions. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2019, 13, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, L.J.; Vogel, M.; Stein, R.; Hilbert, A.; Breinker, J.L.; Böttcher, M.; Kiess, W.; Poulain, T. Mental health in children and adolescents with overweight or obesity. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.J.; Park, S.; Kim, J.Y. Development of Korean NOVA food classification and estimation of ultra-processed food intake among adults: Using 2018 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Korean J. Community Nutr. 2022, 27, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.S.; Shim, S.Y.; Cha, H.J.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.C. Association between ultra-processed food consumption and dietary intake and diet quality in Korean adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 122, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. User Guide for the 8th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VIII); Report No. 117002; Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency: Cheongju City, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, H.; Park, J.M.; Oh, S.U.; Ha, K.; Joung, H. Consumption of ultra-processed foods increases the likelihood of having obesity in Korean women. Nutrients 2021, 13, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiolero, A.; Faeh, D.; Paccaud, F.; Cornuz, J. Consequences of smoking for body weight, body fat distribution, and insulin resistance1. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strine, T.W.; Okoro, C.A.; Chapman, D.P.; Balluz, L.S.; Ford, E.S.; Ajani, U.A.; Mokdad, A.H. Health-related quality of life and health risk behaviors among smokers. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.; Nimmo, L.; Elatrozy, T.; Anyaoku, V.; Hughes, C.; Robinson, S.; Richmond, W.; Elkeles, R.S. Smoking is associated with increased hepatic lipase activity, insulin resistance, dyslipidaemia and early atherosclerosis in Type 2 diabetes. Atherosclerosis 2001, 156, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, A.A.; Rohrer, J.E. Patterns of alcohol drinking and its association with obesity: Data from the third national health and nutrition examination survey, 1988–1994. BMC Public Health 2005, 5, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, P.M.; Tremblay, A. Is Alcohol Consumption a Risk Factor for Weight Gain and Obesity? Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2005, 42, 197–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Kwon, S.; Yon, M.; Kim, D.; Lee, J.Y.; Nam, J.; Park, S.; Yeon, J.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.; et al. Dietary total sugar intake of Koreans: Based on the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), 2008–2011. J. Nutr. Health 2014, 47, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, E.K. Current status of Korean sugar intake and reduction policy. Food Ind. Nutr. 2018, 23, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, V.S.; Hu, F.B. Sweeteners and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes: The role of sugar-sweetened beverages. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2012, 12, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, L.; Imamura, F.; Lentjes, M.A.; Khaw, K.T.; Wareham, N.J.; Forouhi, N.G. Prospective associations and population impact of sweet beverage intake and type 2 diabetes, and effects of substitutions with alternative beverages. Diabetologia 2015, 58, 1474–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, G.A. How bad is fructose? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 527–529. [Google Scholar]

- Stanhope, K.L. Sugar consumption, metabolic disease and obesity: The state of the controversy. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2016, 53, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, M.B.; Lavine, J.E. Dietary fructose in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2013, 57, 2525–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.S.; Mietus-Snyder, M.; Valente, A.; Schwarz, J.M.; Lustig, R.H. The role of fructose in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and the metabolic syndrome. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 7, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, N.J.; Heitmann, B.L. Intake of calorically sweetened beverages and obesity. Obes. Rev. 2009, 10, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Li, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Q.; Sun, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, T.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Q.; et al. Sugar and artificially sweetened beverages and risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and all-cause mortality: A dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, I.; Rathmanner, T.; Kunze, M. Eating and dieting differences in men and women. J. Mens. Health Gend. 2005, 2, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scander, H.; Monteagudo, C.; Nilsen, B.; Tellström, R.; Yngve, A. Beverage consumption patterns and energy contribution from beverages per meal type: Results from a national dietary survey in Sweden. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 3318–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elslami, A.A.; Bastami, F.; Ardalan, A.; Almasian, M.; Alibakhshi, M. Energy drink consumption and increased risk of smoking and alcohol and sweetened beverages use among university students. Health Behav. Policy Rev. 2022, 9, 894–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemelä, O.; Aalto, M.; Bloigu, A.; Bloigu, R.; Halkola, A.S.; Laatikainen, T. Alcohol drinking patterns and laboratory indices of health: Does type of alcohol preferred make a difference? Nutrients 2022, 14, 4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keefe, J.H.; Bhatti, S.K.; Bajwa, A.; DiNicolantonio, J.J.; Lavie, C.J. Alcohol and cardiovascular health: The dose makes the poison…or the remedy. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2014, 89, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osna, N.A.; Donohue, T.M.; Kharbanda, K.K. Alcoholic liver disease: Pathogenesis and current management. Alcohol Res. 2017, 38, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moubarac, J.C.; Parra, D.C.; Cannon, G.; Monteiro, C.A. Food classification systems based on food processing: Significance and implications for policies and actions: A systematic literature review and assessment. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2014, 3, 256–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julia, C.; Martinez, L.; Allès, B.; Touvier, M.; Hercberg, S.; Méjean, C.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Contribution of ultra-processed foods in the diet of adults from the French NutriNet-Santé study. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louzada, M.L.d.C.; Ricardo, C.Z.; Steele, E.M.; Levy, R.B.; Cannon, G.; Monteiro, C.A. The share of ultra-processed foods determines the overall nutritional quality of diets in Brazil. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Steele, E.; Popkin, B.M.; Swinburn, B.; Monteiro, C.A. The share of ultra-processed foods and the overall nutritional quality of diets in the US: Evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. Popul. Health Metr. 2017, 15, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, M.; Heshmati, J.; Shahinfar, H.; Tripathi, N.; Daneshzad, E. Ultra-processed food and the risk of overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int. J. Obes. 2020, 44, 2080–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaak, E.E. Sex differences in the control of glucose homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2008, 11, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovejoy, J.C.; Sainsbury, A. Sex differences in obesity and the regulation of energy homeostasis. Obes. Rev. 2009, 10, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, K.D.; Kahan, S. Maintenance of lost weight and long-term management of obesity. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 102, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rico-Campà, A.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Alvarez-Alvarez, I.; de Deus Mendonça, R.; de la Fuente-Arrillaga, C.; Gómez-Donoso, C.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Association between consumption of ultra-processed foods and all cause mortality: SUN prospective cohort study. BMJ 2019, 365, l1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjibade, M.; Andreeva, V.A.; Lemogne, C.; Touvier, M.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Assmann, K.E.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Ultra-processed food intake and the risk of depressive symptoms: Results from the NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Men (n = 4105) | Women (n = 5557) | Total (n = 9662) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| N (%) | 4105 (50.2) | 5557 (49.8) | 9662 (100.0) | 0.7384 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 19–64 years | 41.9 ± 0.2 | 42.6 ± 0.2 | 42.5 ± 0.3 | 0.0055 |

| 19–29 | 769 (22.0) | 858 (21.1) | 1627 (21.6) | 0.0022 |

| 30–39 | 763 (21.5) | 1020 (19.9) | 1783 (20.7) | |

| 40–49 | 972 (23.8) | 1375 (23.8) | 2347 (23.8) | |

| 50–59 | 1011 (24.4) | 1501 (24.8) | 2512 (24.6) | |

| 60–64 | 590 (8.2) | 803 (10.4) | 1393 (9.3) | |

| Income level | ||||

| Low | 1039 (24.3) | 1341 (23.0) | 2380 (23.6) | 0.3575 |

| Middle-low | 1018 (25.2) | 1371 (24.9) | 2389 (25.1) | |

| Middle-high | 1025 (25.0) | 1407 (25.8) | 2432 (25.4) | |

| High | 1023 (25.5) | 1438 (26.3) | 2461 (25.9) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 2830 (64.2) | 4459 (74.8) | 7289 (69.5) | <0.0001 |

| Single | 1275 (35.8) | 1098 (25.2) | 2373 (30.5) | |

| Household types | ||||

| Single-person household | 546 (12.3) | 452 (6.9) | 998 (9.6) | <0.0001 |

| Multi-person household | 3559 (87.7) | 5105 (93.1) | 8664 (90.4) | |

| Educational level | ||||

| Elementary school or less | 146 (2.3) | 343 (4.5) | 489 (3.4) | <0.0001 |

| Middle school | 248 (4.6) | 428 (6.1) | 676 (5.4) | |

| High school | 1620 (40.4) | 2119 (38.9) | 3739 (39.6) | |

| College or higher | 2091 (52.7) | 2667 (50.5) | 4758 (51.6) | |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Paster/no smoker | 2682 (65.8) | 5245 (93.8) | 7927 (79.8) | <0.0001 |

| Current Smoker | 1423 (34.2) | 312 (6.2) | 1735 (20.2) | |

| Alcohol consumption (1) | ||||

| yes | 2894 (70.5) | 2574 (48.3) | 5468 (59.4) | <0.0001 |

| no | 1211 (29.5) | 2983 (51.7) | 4194 (40.6) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.9 ± 0.1 | 23.1 ± 0.1 | 23.3 ± 0.0 | <0.0001 |

| Obesity | 1859 (45.8) | 1504 (25.9) | 3363 (35.9) | <0.0001 |

| Men (n = 4105) | Women (n = 5557) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultra-processed food intake | 401.3 ± 8.0 | 260.1 ± 4.6 | <0.0001 |

| Ultra-processed food subgroup intake | |||

| (1) Cereals, breads, cakes, sandwiches, etc. | 28.1 ± 1.3 | 29.6 ± 1.2 | 0.3553 |

| (2) Distilled alcoholic beverages | 58.6 ± 2.9 | 12.4 ± 1.3 | <0.0001 |

| (3) Sugar-sweetened beverages (1) | 48.2 ± 2.3 | 28.1 ± 1.4 | <0.0001 |

| (4) Fish and meat processed foods | 33.4 ± 1.7 | 19.0 ± 0.9 | <0.0001 |

| (5) Instant noodles and dumplings | 8.0 ± 0.7 | 5.7 ± 0.4 | 0.0032 |

| (6) Traditional sauce | 23.4 ± 0.5 | 16.3 ± 0.3 | <0.0001 |

| (7) Sweetened milk and its products | 24.6 ± 1.5 | 29.2 ± 1.5 | 0.0335 |

| (8) Others (instant sauce, condiments, etc.) | 17.5 ± 0.6 | 14.2 ± 0.5 | <0.0001 |

| (9) Cookies, chips, and snacks | 9.2 ± 0.5 | 8.2 ± 0.4 | 0.0932 |

| (10) Soft drinks, fruit and vegetable drinks | 111.1 ± 4.5 | 68.1 ± 2.8 | <0.0001 |

| (11) Instant cooked rice, soup, and other dishes | 28.4 ± 1.8 | 18.9 ± 1.1 | <0.0001 |

| (12) Confectionary | 10.6 ± 0.7 | 10.5 ± 0.6 | 0.8433 |

| Men (n = 4105) | Women (n = 5557) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | p | T1 | T2 | T3 | p | |

| Energy (kcal) | 1837.6 ± 20.7 | 2197.2 ± 21.7 | 2703.2 ± 25.0 | <0.0001 | 1348.9 ± 12.6 | 1630.6 ± 15.0 | 1950.3 ± 18.4 | <0.0001 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 276.1 ± 3.1 | 305.8 ± 3.4 | 329.7 ± 3.6 | <0.0001 | 209.7 ± 2.2 | 237.3 ± 2.4 | 265.3 ± 2.6 | <0.0001 |

| Protein (g) | 74.0 ± 1.1 | 84.5 ± 1.1 | 101.0 ± 1.3 | <0.0001 | 52.2 ± 0.7 | 62.8 ± 0.8 | 72.0 ± 1.0 | <0.0001 |

| Fat (g) | 43.8 ± 0.9 | 59.4 ± 1.0 | 76.0 ± 1.3 | <0.0001 | 31.6 ± 0.5 | 45.4 ± 0.7 | 58.2 ± 0.9 | <0.0001 |

| Dietary fiber (g) | 26.3 ± 0.4 | 27.9 ± 0.4 | 28.2 ± 0.4 | 0.0024 | 21.8 ± 0.3 | 23.4 ± 0.3 | 23.4 ± 0.3 | 0.0001 |

| Calcium (mg) | 473.2 ± 8.3 | 546.7 ± 8.5 | 583.0 ± 9.5 | <0.0001 | 378.0 ± 5.8 | 472.3 ± 7.0 | 526.3 ± 7.8 | <0.0001 |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 1086.9 ± 13.9 | 1221.1 ± 13.6 | 1356.7 ± 15.2 | <0.0001 | 820.0 ± 9.8 | 959.5 ± 10.7 | 1054.7 ± 11.9 | <0.0001 |

| Iron (mg) | 9.6 ± 0.2 | 11.1 ± 0.2 | 13.0 ± 0.3 | <0.0001 | 7.2 ± 0.1 | 8.8 ± 0.1 | 10.1 ± 0.2 | <0.0001 |

| Sodium (mg) | 3501.3 ± 56.5 | 3916.9 ± 58.0 | 4360.3 ± 64.3 | <0.0001 | 2333.1 ± 34.4 | 2885.9 ± 41.2 | 3141.2 ± 43.2 | <0.0001 |

| Potassium (mg) | 2800.1 ± 38.4 | 3049.8 ± 37.6 | 3168.3 ± 39.1 | <0.0001 | 2283.3 ± 29.7 | 2562.9 ± 32.7 | 2626.0 ± 33.1 | <0.0001 |

| Vitamin A(μg RAE) | 380.5 ± 13.5 | 432.3 ± 10.9 | 469.8 ± 15.7 | <0.0001 | 324.9 ± 6.7 | 406.6 ± 11.7 | 422.8 ± 8.9 | <0.0001 |

| Vitamin B1 (mg) | 1.2 ± 0.0 | 1.3 ± 0.0 | 1.6 ± 0.0 | <0.0001 | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.1 ± 0.0 | <0.0001 |

| Vitamin B2 (mg) | 1.6 ± 0.0 | 1.9 ± 0.0 | 2.2 ± 0.0 | <0.0001 | 1.2 ± 0.0 | 1.5 ± 0.0 | 1.7 ± 0.0 | <0.0001 |

| Niacin (mg) | 12.9 ± 0.2 | 14.8 ± 0.2 | 18.1 ± 0.3 | <0.0001 | 9.3 ± 0.1 | 11.1 ± 0.2 | 12.8 ± 0.2 | <0.0001 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 54.5 ± 1.6 | 65.3 ± 2.2 | 88.1 ± 6.5 | <0.0001 | 57.7 ± 1.6 | 65.6 ± 2.2 | 71.8 ± 2.2 | <0.0001 |

| Men (n = 4105) | Women (n = 5557) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | p for Trend | T1 | T2 | T3 | p for Trend | |

| Obesity | ||||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.00 | 1.02 (0.86–1.21) | 1.16 (0.98–1.38) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 0.87 (0.73–1.04) | 0.77 (0.64–0.92) | <0.0001 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 | 1.05 (0.88–1.25) | 1.26 (1.03–1.54) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 0.95 (0.79–1.15) | 0.98 (0.81–1.18) | <0.0001 |

| Model 3 | 1.00 | 1.03 (0.88–1.24) | 1.28 (1.05–1.55) | 0.0003 | 1.00 | 1.02 (0.83–1.23) | 1.02 (0.84–1.24) | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.J.; Lee, K.W. Gender Differences in Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Its Association with Obesity Among Korean Adults. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17122027

Lee SJ, Lee KW. Gender Differences in Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Its Association with Obesity Among Korean Adults. Nutrients. 2025; 17(12):2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17122027

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Seung Jae, and Kyung Won Lee. 2025. "Gender Differences in Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Its Association with Obesity Among Korean Adults" Nutrients 17, no. 12: 2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17122027

APA StyleLee, S. J., & Lee, K. W. (2025). Gender Differences in Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Its Association with Obesity Among Korean Adults. Nutrients, 17(12), 2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17122027