Abstract

Obesity has been linked to vitamin D (VD) deficiency and low calcium (CAL) status. In the last decade, dietary supplementation of vitamin D and calcium (VD–CAL) have been extensively studied in animal experiments and human studies. However, the physiological mechanisms remain unknown as to whether the VD–CAL axis improves homeostasis and reduces biomarkers in regulating obesity and other metabolic diseases directly or indirectly. This review sought to investigate their connections. This topic was examined in scientific databases such as Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed from 2011 to 2021, and 87 articles were generated for interpretation. Mechanistically, VD–CAL regulates from the organs to the blood, influencing insulin, lipids, hormone, cell, and inflammatory functions in obesity and its comorbidities, such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, cardiovascular disease, and type-2 diabetes mellitus. Nevertheless, previous research has not consistently shown that simultaneous VD–CAL supplementation affects weight loss or reduces fat content. This discrepancy may be influenced by population age and diversity, ethnicity, and geographical location, and also by degree of obesity and applied doses. Therefore, a larger prospective cohort and randomised trials are needed to determine the exact role of VD–CAL and their interrelationship.

1. Introduction

Due to inappropriate diets and nutrient intake, obesity has become more common in all age groups, such as children [1], adolescents [2], and the elderly [3]. Obesity is increasing in prevalence in Asia-Pacific [4], Europe [5], Africa [6], and America [7] and has become a worldwide epidemic [8]. Taking this into account, the member states of the United Nations have developed a global platform, the Sustainable Development Goals, addressing noncommunicable diseases as core priorities [9].

Obesity is caused by micronutrient deficiency [10], inadequate intake of vitamins, such as cobalamin (vitamin B12), ascorbic acid (vitamin C), fat-soluble vitamins, and folic acid [11], a deficiency of vitamin D (VD) [12], poor mineral status [13], and low calcium (CAL) diet [14]. The average plasma concentration of 25(OH)D is used to determine VD level. A less than 50 nmol/L of 25(OH)D serum concentration indicates VD deficiency. [15]. Furthermore, obesity is characterised by accumulation of >70% of body fat mass [16]. VD3, and its metabolites 25(OH)D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3, are deposited in adipocyte lipid droplets [17]. 25(OH)D is a fat-soluble metabolite disseminated to fat, muscle, liver, and in smaller amounts to other tissues. The stomach’s ability to absorb CAL depends on the presence of active VD. VD deficiency causes osteomalacia and rickets in adults and children, respectively, whereas moderate deficiency results in an upsurge in the risk of bone turnover and bone fractures [12].

On the other hand, CAL ion (Ca2+) is available in abundance in the body. Ca2+ is deposited in bones, mostly as CaPO3 (hydroxyapatite), and plays a structural role. It is required for muscle contraction and pancreatic secretion of insulin and glucagon in response to blood glucose fluctuations. Therefore, alterations in Ca2+ homeostasis can have a strong impact on tissues, including the heart and skeletal muscle, contributing to obesity and diabetes [18]. The adipocyte metabolism pathway is regulated by intracellular Ca2+. In human adipocytes, intracellular Ca2+ stimulates energy and fat storage through de novo lipogenesis (DNL) promotion and lipolysis prevention [19]. Hypocalcemia is characterized by CAL concentrations under 8 mg/dL or ionized CAL levels under 4.4 mg/dL [20].

Numerous experiments have established a link between vitamin D and calcium (VD–CAL) supplementation and the occurrence of metabolic diseases [21] such as chronic liver disease [22], osteoporosis [23], diabetes mellitus [24], and high blood pressure [25]. However, there are some discrepancies in the results, and the role of VD–CAL supplementation remains unclear [26]. Contradictory outcomes have been reported for VD levels [27] and CAL status [28] in obesity. Furthermore, an expert panel concluded that no confirmation supports the extraskeletal role of CAL or VD [29].

In light of current knowledge, this study assessed the interrelationship of VD–CAL in the onset of obesity and its comorbid conditions using scientific evidence from recent animal studies and human clinical trials. Besides that, this study also collected the relationship of VD–CAL in the metabolic functions of obesity, such as in the gut, bone, blood lipid and glucose levels, kidney, pancreas, liver, adipose tissue, and the immunoregulatory system. This review could aid in developing dietary recommendations for obese people and future studies into the influences of VD–CAL simulataneus supplementation in this group.

2. Search Strategy and Method

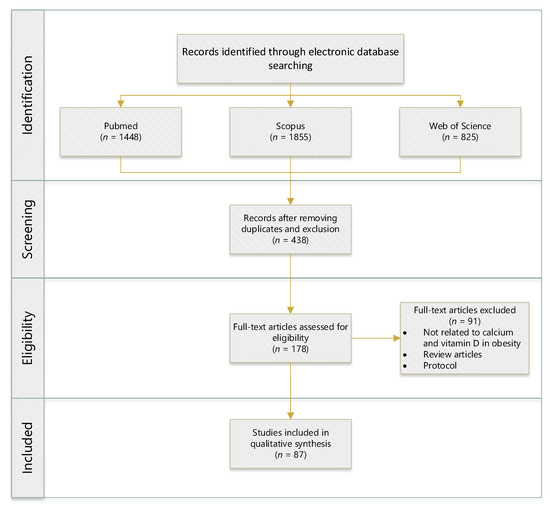

Scientific databases, such as Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed, were utilised to conduct a methodical search for relevant articles by employing the following key phrases: “correlation”, “relationship”, “link”, “association”, “vitamin-D”, “calcium”, “obesity”, “rats”, “mice”, and “human clinical trial”. The search generated 87 articles published between 2011 and 2021, which investigated the relationship of VD–CAL in obesity (Figure 1). Table 1 shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this literature search strategy. Duplicates, review articles, protocol studies, second analysis reports, articles not related to VD–CAL, and articles not published in English were excluded. The interrelationship findings were compiled by summarising them in tables.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of identifying, screening, selecting, and determining the literature search. (n = numbers).

Table 1.

Search constraints and criteria.

3. Physiological Association of VD–CAL

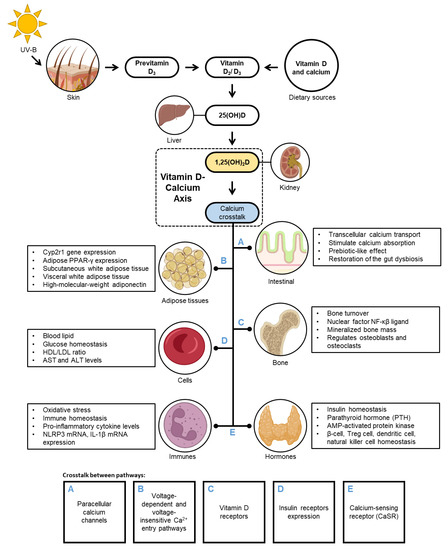

Figure 2 depicts the role of the VD–CAL axis in regulating the physiological mechanisms involved in obesity. VD–CAL status determines adipose tissue functions, body fatness, bone density, inflammatory, insulin, hormone, and cell functions.

Figure 2.

The regulation of vitamin D-calcium axis in obesity.

VD exists naturally in a limited number of food sources and is endogenously formed when solar ultraviolet rays (290–315 nm) stimulate VD synthesis in the body’s outermost layer and is then primarily kept in fat in the body [30].

The available evidence indicates that VD–CAL is involved in physiological interactions; 1,25(OH)2D, an active VD metabolite, regulates CAL transport across the intestinal wall and binds to the VD receptor (VDR) in the intestinal epithelial cells, inducing the synthesis of CAL-binding protein CaBP-9K and activating TRPV6 and TRPV5 CAL channels. CAL enters the cell through the intestinal lumen and is transported by CAL-binding protein throughout the cell and to the interstitium via an ATP-dependent mechanism [31]. In the intestinal epithelium, 1,25(OH)2D modulates paracellular CAL channels in the transepithelial electrochemical gradient by regulating claudin-2 and claudin-12 [32]. In adipose tissue, it stimulates voltage-dependent and voltage-insensitive Ca2+ access pathways and controls Ca2+ release from endoplasmic reticulum stores via inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate and ryanodine receptors [16]. In bone regulation, 1,25(OH)2D enters cells by diffusion by binding to complex VDRs and regulates mineralised bone mass by controlling intestinal CAL absorption and supplying adequate CAL to the bone matrix [33,34]. In beta cells, activated VD metabolites increase the sensitivity of insulin receptors, glucose homeostasis transcription factors, and/or CAL regulation in peripheral insulin-target cells [30,35]. CAL in the extracellular fluid stimulates CaSR on the parathyroid cells, which raises intracellular CAL levels and suppresses PTH release. In the kidneys, PTH regulates the conversion of 25(OH)D to 1,25(OH)2D, which augments intestinal CAL absorption. PTH has the ability to administer circulating IL-6 and TNF-α concentrations, which promote the production of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein [32,36].

4. Interrelationship of VD–CAL in Obesity and Its Disease States

4.1. Impact of VD–CAL on Adipose Tissue

The accumulation of a large amount of fat in adipose tissue characterises obesity. The relationship between VD–CAL and obesity, both with and without supplementation, is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

VD–CAL in adipose tissues in animal and human studies.

Adipose tissue stores most of VD, which influences CAL homeostasis and energy metabolism. A link has been shown between VD levels and CAL in adipose tissue. In obese individuals, supplementation with VD causes a significant accumulation of this vitamin in the liver and adipose tissue [38], increased leptin-to-adiponectin ratio [46], and decreased inflammation in adipose tissue [37] and hepatic steatosis by downregulating the gene expression associated with hepatic de novo lipogenesis (DNL) and oxidation of fatty acid [39]. It was also shown that administration of a high-fat diet supplemented with 1,25(OH)2D3 resulted in a reduction in macrophage infiltration in adipose tissue [40].

Besides VD intervention, supplementation of CAL in obese people was found to confer a prebiotic-like effect on the gut microbiota and decrease the stress marker expression in adipose tissue and liver inflammation [41], reduce body mass and modify glucocorticoid receptors expression and Vdr in the visceral adipose tissue [42], increase the expression of Cyp27b1/1α-hydroxylase and adipogenesis [43], decrease adipocyte hypertrophy and adipokines levels (TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1, leptin), and rise adiponectin levels [45].

Supplementation of VD and CAL may be a useful and cost-efficient strategy for preventing and treating obesity. Rosenblum et al. [47] reported that a serving of 350 mg CAL and 100 IU VD per 240 mL glasses of orange juice resulted in significant depletion of visceral adipose tissue. Similarly, Sergeev and Song [44] observed that a high intake of VD–CAL influenced the adipose tissue Ca2+-mediated apoptotic pathway. The authors noted that VD3-CAL supplementation was more potent than either of these alone in decreasing adiposity in male C57BL/6J mice aged four weeks old.

4.2. Impact of VD–CAL on Body Fatness

Obesity is commonly linked to a lack of VD–CAL, which are nutrients that regulate body fat. The relationship between these nutrients and obesity is summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

VD–CAL in body fatness.

The prevalence of obesity may be decreased by a dose of VD or CAL. Evidence suggests that VD–CAL intake can decline body fat. The higher the concentration of 25(OH)D, the lower the body fat mass [54]. Similar to VD, a low CAL intake can negatively impact the levels of various lipid metabolic markers (glucose, triglyceride, and insulin) and increase body fat [50]. BMI and body fat levels strongly correlate with 25(OH)D concentration and the CAL-phosphorus product [56]. A high-fat diet has been revealed to promote hypermethylation and hypomethylation of Cyp24a1, resulting in glutathione deficiency and an altered VD biosynthesis pathway [51]. Additionally, there was a correlation between decreased Cyp2r1 gene expression and decreased circulating 25(OH)D concentrations [52].

However, VD–CAL levels in obese people have an unsatisfactory correlation. In obese individuals, neither BMI nor body fat percentage were significantly related to VD levels [48]. After treatment, no impact of VD supplementation was obtained on body fat, subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue, and intrahepatic and intramyocellular lipids in this population [55]. Additionally, VD supplementation had no discernible effect on total body fat mass [57]. These results support the most recent finding that weekly VD3 administration at a high dose (3750 IU) had no impact on sarcopenia or adiposity indices [60].

VD–CAL have been gaining increasing interest in obesity management. These nutrients have been tested in combination and also formulated in food products. A VD-enriched Lentinula edodes preparation reduced total body fat accumulation and hepatic fat content in obese C57BL/6 mice [49]. Similarly, a study showed that consumption of VD-fortified yoghurt drink (containing 170 mg CAL and 12.5 μg VD3/250 mL) for twelve weeks led to a decrease in waist circumference, body fat mass, and truncal fat in people with type-2 diabetes aged 30–60 years old [53]. In addition, supplementation of CAL and VD3 caused a significant reduction in weight, BMI, waist circumference, and body fat percentage in obese women aged 18–48 years old [58]. In another study on overweight or obese males aged 18–25 years old, a 12-week supplementation of CAL and VD3 (600 mg of CAL and 125 IU of VD3) resulted in body fat loss and visceral fat loss [59].

4.3. Impact of VD on Bone Density

Patients and healthcare practitioners frequently overlook the importance of VD in bone health. Table 4 presents the findings of studies on the advantageous effects of VD.

Table 4.

VD on bone density.

Diet-induced obesity has been found to decrease the volume, number, and thickness of trabecular bone [63]. Diets containing saturated fatty acids and adequate amount of VD altered the metabolism of VD and bone changes, which suggests the critical role of dietary fat composition [65]. Supplementation of VD increased intestinal permeability and systemic lipopolysaccharide levels, resulting in stronger trabecular bone [61,62], and inhibited differentiation and maturation [64], as well as elevated autophagy flux of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells [66]. Furthermore, VD levels have been linked with bone loss [67], bone turnover [68], and areal bone mineral density [69].

4.4. Impact of VD–CAL on Inflammatory, Insulin, Hormone, and Cell Functions

Obesity and its associated health problems are linked to low levels of VD–CAL in the blood. VD–CAL contributes to obesity and its comorbidities by influencing inflammation, insulin sensitivity, hormone production, and cell functions (Table 5).

Table 5.

VD–CAL in inflammatory, insulin, hormone, and cell functions.

Apart from its vital role in CAL homeostasis, VD–CAL is involved in modulating inflammatory, insulin, hormone, and cell functions in obesity. Administration of VD was shown to reduce intestinal inflammation [77] and the level of inflammatory markers [82,83,94], and also regulate the concentrations of IL-1β, NF-Kβ, acetylcholine, brain-derived neurotropic factor [73], blood-brain barrier permeability [75], and pro-inflammatory cytokine levels [70]. However, previous studies suggest that VD–CAL supplementation does not affect inflammatory regulation in obesity. VD intervention did not cause any change in the concentrations of us-CRP and IL-6 [92], sICAM-1, hs-CRP, AGP [90], and inflammatory cytokines [89,91]. Similarly, a study showed that a CAL-rich diet had no beneficial impact on inflammation, fibrinolysis, and endothelial function [85].

Furthermore, a high-fat diet triggered insulin resistance [71], and VD deficiency also correlated with this condition in obese people [94]. VD intake influenced IRS-1/p-IRS-1 expression [80] and enhanced HOMA-IR [74]. CAL intake also improved insulin sensitivity, redox balance, and liver steatosis [83]. Nevertheless, VD supplementation had a negative impact on the relationship between 25(OH)D and insulin resistance [95] and HOMA-IR [87,96].

VD has been linked to cell regulation in obesity. The intake of this vitamin was shown to inhibit the expression of NF-κB [78] and regulate HIF1α in T cells [79]. However, VD intake had no significant effect on IFN-γ intracellular expression, NKG2D, and CD107a surface expression in NK cells, Vdup1 and Vdr mRNA levels [76], and T cell autophagy [72]. Apart from its role in inflammatory, insulin, and cell functions, a connection has been found between VD and hormone regulation, with VD exerting a suppressing effect on PTH levels in obese individuals [84,86,88,97].

4.5. Potential Applications of VD–CAL in Obesity Prevention

Low levels of VD–CAL have been connected with an improved risk of obesity. Supplementation of VD–CAL can be beneficial in the treatment of obesity, as summarised in Table 6.

Table 6.

The evidence of VD–CAL supplementation in obesity.

Obesity and its related conditions have been studied in relation to VD’s potential role as a treatment. Supplementing with VD lowered the rate of weight gain [99] and body mass [104], increased glucose homeostasis, and regulated energy expenditure in obese people [100]. Additionally, VD intake prevented histological damage of the colon [101], reduced hepatic steatosis, improved mitochondrial dysfunction in the liver, decreased stress oxidation, and triggered phase II enzymes [102].

Clinical studies, on the other hand, have found no link between 25(OH)D concentrations and hepatic enzymes, indicating a lack of interaction between VD deficiency and obesity [110] and no impact of VD on post-load glucose or other glycemic indices [112]. Supplementing with VD had no significant effect on weight, fat mass, or waist circumference [115]. Lack of VD increased the activity of neutral sphingomyelinases in obese people with cardiovascular disease, which had implications for chylomicron and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and very-low-density lipoprotein clearance, as well as decreased postprandial inflammation and macrophage adhesion to endothelia [111].

On the other hand, in obese patients with VD deficiency, VD supplementation significantly enhanced serum 25(OH)D levels [117], reduced the size of the left atrium [113], reduced hs-CRP and TNF-α concentrations [114], and increased insulin sensitivity [116].

Furthermore, VD intake combined with physical exercise led to a rise in peak power and VD status, reduced waist-to-hip ratio [104], and improved insulin resistance and hepatic disease [98]. However, this combination did not influence inflammatory biomarkers such as CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6 [107].

The role of diets enriched with VD–CAL has also been investigated. Faghih et al. [106] reported that diet of a daily 500 kcal deficit with daily 500–600 mg CAL (1), a daily 500 kcal deficit with daily 800 mg CAL (2), a daily 500 kcal deficit with three servings of low-fat milk (3), and a daily 500 kcal deficit with three portions of CAL-fortified soy milk (4), resulted in decreased body weight and BMI in all groups of healthy, overweight, or obese premenopausal women aged 20–50 years. Valle et al. [103] showed that supplementation of salmon peptide fraction (25% of protein) and VD (15,000 IU/kg of diet) aided in maintaining metabolic syndrome via gut–liver axis by controlling hepatic and gut inflammation (increasing Mogibacterium and Muribaculaceae) in mice fed with high-fat and high-sucrose diets containing VD (25 IU/kg of diet). Sharifan et al. [108] observed a correlation between fortified dairy products containing VD3 (1500 IU) and anthropometric indices, glucose homeostasis, and lipid profiles in adults (30–50 years old) with abdominal obesity. Similarly, Vinet et al. [109] observed that consumption of 200 mL fruit juice supplemented with VD3 (4000 IU) every morning led to the weakening of microvascular dysfunction without any impact on macrovascular function by increasing 25(OH)D levels, decreasing HOMA-IR and CRP, and improving endothelium-dependent microvascular reactivity in obese adolescents aged 12–17 years old and with a BMI of 31.2–36.2 kg/m2.

Unfortunately, prior studies could not identify a compensatory mechanism and did not exhibit the impact of VD–CAL channels, namely TRPV5 and TRPV6, which can influence the CAL transport process. According to Veldurthy et al. [118], 1,25(OH)2D3 regulated transcellular transport by influencing the epithelial CAL channel TRPV5. TRPV5 enables the entry of apical CAL entry by inducing calbindins (calbindin-D9k and calbindin-D28k). Moreover, calbindin-D9k and TRPV6 expression are administered by 1,25(OH)2D3. TRPV6 overexpression results in hypercalciuria, hypercalcemia, and calcification of soft tissues, indicating that this channel plays a key role in the intestinal absorption of CAL.

4.6. Inadequate Evidence for the Effect of VD–CAL on Obesity

Although the benefits of VD–CAL supplementation have been documented, previous reports have established that these two nutrients are incompatible. The inconsistent results about the impacts of VD–CAL observed in experiments on obese populations are summarised in Table 7.

Table 7.

The inadequate evidence of VD–CAL status in obesity.

Thomas et al. [119] demonstrated insufficient evidence for the influence of high dietary CAL (CAL carbonate) on obesity-related phenotypes, including impaired weight gain and hyperphagia, in diet-induced obese 4-week-old male C57BL/6J mice. Wood et al. [120] found no effect on physical function after VD3 supplementation (400 or 1000 IU) for one year in postmenopausal women aged 60–70 years old with a BMI of 18–45 kg/m2. Salehpour et al. [121] presented inadequate data on the impact of VD3 intake (25 μg as cholecalciferol) on glucose homeostasis in overweight or obese women with an average age of 38 ± 8 years old and a BMI of 29.9 ± 4.2 kg/m2. Brzezinski et al. [122] observed an insignificant impact of 26-week VD (1200 IU) intake on body weight reduction in overweight and obese children aged 6–15 years old who had VD insufficiency (<30 ng/mL). Additionally, Jones et al. [123] showed that supplementation of dairy (~700 mg per day of CAL with 500 kcal per day) and CAL-rich dairy (~1400 mg per day of CAL with 500 kcal per day) had no effect in increasing weight loss. However, CAL-rich dairy improved plasma levels of peptide tyrosine tyrosine in men and women aged 20–60 years old and with a BMI of 27–37 kg/m2. Kerksick et al. [124] demonstrated that the supplementation with VD–CAL did not significantly affect the alteration of body composition in overweight postmenopausal women.

Based on the literature review, it can be concluded that the role of CAL and VD in metabolic disorders and obesity is well understood. However, the results on the impact of the deficit or the supplementation used on body weight, fat content, or biochemical parameters obtained especially in human studies are often ambiguous. It seems that many factors, including population diversity, may lead to the inconsistency of results of VD–CAL in the obese. The cited studies were conducted on a variety of populations, geographies, and races. For instance, low VD status affects the occurrence of a VD deficiency in Western European residents during the wintertime periods, South Africa, Oceania, and Asian countries (Middle East, China, Mongolia, and India) [125]. In the same vein as the global VD status, many countries have low average dietary CAL ranges between 175 and 1233 mg across half the world’s nations, such as Asia, Africa, and Latin America, and only a handful of European countries [126]. Furthermore, low VD concentrations were discovered to be a significant difference between native residents with immigrant residents [127] and multi-ethnic residents [128]. Besides that, there was an association between VD levels and elevation in a population [129]. A difference of one or two degrees in latitude enormously influenced 25(OH)D serum levels and bone density amid a low VD-sufficiency population [130]. Two different continents in the same population also influenced the CAL concentrations [131]. Therefore, these variables may predominance the inadequate evidence of VD–CAL supplementation in obese populations [120,121,122,123,124].

5. Limitations

Overall, the evidence from previous studies showing the importance of the VD–CAL axis in obesity suggests that investigations carried out so far, especially human studies, could not find a clear relationship between VD–CAL status in obesity [120,121,122,123,124]. There is also data showing harmful effects caused by consuming these nutrients alone or in combination [132]. However, prior studies on animal models [98,99,100,101,102,103] and humans largely [104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117] recommend the use of VD–CAL as potential therapeutic agents for the management of obesity.

Using a comprehensive literature strategy, this article has presented results collected from the studies conducted in the last ten years on the interrelationship of VD–CAL in obesity. However, the present article also has some limitations, including the lack of discussion about the side effects of VD–CAL intake, including its toxicity, which can be helpful for designing an obesity management therapy. It should be mentioned that CAL intervention studies have provided minimal evidence [133,134] supporting the application of CAL supplements in treating obesity and its comorbidities.

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

There is little research into the effects of the concomitant use of VD and CAL on obesity and metabolic disorders. The results of the current research, where VD and CAL were used separately and in combination, are inconclusive. Mechanistically, the VD–CAL axis affects lipid status, insulin, hormones, cells, and inflammatory functions in obesity and its comorbidities from the organs to the blood. Previous research on animals and humans has not consistently supported the hypothesis that VD–CAL supplementation can accelerate weight loss or fat loss in obesity. Many factors may affect the obtained results, including the age of subjects, degree of obesity, applied doses, population diversity, ethnicity, and geographical location. Therefore, more large-scale prospective cohort studies and randomised trials are required to fully clarify the simultaneous administration of VD–CAL as well as their interrelationship for the safe use of these nutrients in the management of the global obesity epidemic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, I.A.H. and J.S.; methodology, I.A.H.; data curation, I.A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, I.A.H. and J.S.; writing—review and editing, I.A.H., J.-F.L. and J.S.; visualisation, I.A.H.; funding acquisition, J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study secured the statutory research from Poznan University of Life Sciences with No. 506-786-00-03.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Kumar, S.; Kelly, A.S. Review of Childhood Obesity: From Epidemiology, Etiology, and Comorbidities to Clinical Assessment and Treatment. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza Silva, J.; Sobrinho, S.; Elaine Pereira, S.; José Saboya Sobrinho, C.; Ramalho, A. Nutrición Hospitalaria Trabajo Original Obesidad y síndrome metabólico Obesity, related diseases and their relationship with vitamin D defi ciency in adolescents Obesidad, enfermedades relacionadas y su relación con la defi ciencia de vitamina D en adoles. Nutr. Hosp. 2016, 33, 856–864. [Google Scholar]

- Dădârlat-Pop, A.; Sitar-Tăut, A.; Zdrenghea, D.; Caloian, B.; Tomoaia, R.; Pop, D.; Buzoianu, A. Profile of obesity and comorbidities in elderly patients with heart failure. Clin. Interv. Aging 2020, 15, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoo, S.; Morris, T. Physical activity and obesity research in the Asia-Pacific: A review. Asia-Pac. J. Public Health 2012, 24, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineda, E.; Sanchez-Romero, L.M.; Brown, M.; Jaccard, A.; Jewell, J.; Galea, G.; Webber, L.; Breda, J. Forecasting Future Trends in Obesity across Europe: The Value of Improving Surveillance. Obes. Facts 2018, 11, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yako, Y.Y.; Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B.; Balti, E.V.; Matsha, T.E.; Sobngwi, E.; Erasmus, R.T.; Kengne, A.P. Genetic association studies of obesity in Africa: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenthal, R.J.; Morton, J.; Brethauer, S.; Mattar, S.; De Maria, E.; Benz, J.K.; Titus, J.; Sterrett, D. Obesity in America. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2017, 13, 1643–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaacks, L.M.; Vandevijvere, S.; Pan, A.; McGowan, C.J.; Wallace, C.; Imamura, F.; Mozaffarian, D.; Swinburn, B.; Ezzati, M. The obesity transition: Stages of the global epidemic. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019, 7, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.N.; Jewell, J.; Whiting, S.; Rippin, H.; Farrand, C.; Wickramasinghe; Kremlin Breda, J. Nutrition, Overweight and Obesity Factsheet-Sustainable Development Goals: Health Targets; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Damms-Machado, A.; Weser, G.; Bischoff, S.C. Micronutrient deficiency in obese subjects undergoing low calorie diet. Nutr. J. 2012, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas-Valdés, S.; Das, M.; Tostes, G.V.; Anunciação, P.C.; Da Silva, B.P.; Sant’ana, H.M.P.; Thomas-Vald Es, S.; Das Graças, M.; Tostes, V.; Anunciaçao, P.C.; et al. Association between vitamin deficiency and metabolic disorders related to obesity. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3332–3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.S.; Bowles, S.; Evans, A.L. Vitamin D in obesity. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2017, 24, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliburska, J.; Cofta, S.; Gajewska, E.; Kalmus, G.; Sobieska, M.; Samborski, W.; Krejpcio, Z. The evaluation of selected serum mineral concentrations and their association with insulin resistance in obese adolescents. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 17, 2396–2400. [Google Scholar]

- Marotte, C.; Bryk, G.; Gonzales Chaves, M.M.S.; Lifshitz, F.; Pita Martín de Portela, M.L.; Zeni, S.N. Low dietary calcium and obesity: A comparative study in genetically obese and normal rats during early growth. Eur. J. Nutr. 2014, 53, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Santos, M.; Costa, P.R.F.; Assis, A.M.O.; Santos, C.A.S.T.; Santos, D.B. Obesity and vitamin D deficiency: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Sergeev, I.N. Calcium and vitamin D in obesity. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2012, 25, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, R.P.; Recker, R.R.; Grote, J.; Horst, R.L.; Armas, L.A.G. Vitamin D(3) is more potent than vitamin D(2) in humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, E447–E452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruda, A.P.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Calcium homeostasis and organelle function in the pathogenesis of obesity and diabetes. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemel, M.B.; Thompson, W.; Milstead, A.; Morris, K.; Campbell, P. Calcium and dairy acceleration of weight and fat loss during energy restriction in obese adults. Obes. Res. 2004, 12, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuralli, D. Clinical Approach to Hypocalcemia in Newborn Period and Infancy: Who Should Be Treated? Int. J. Pediatr. 2019, 2019, 4318075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Garach, A.; García-Fontana, B.; Muñoz-Torres, M. Vitamin D status, calcium intake and risk of developing type 2 diabetes: An unresolved issue. Nutrients 2019, 11, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteh, J.; Narra, S.; Nair, S. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in chronic liver disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2010, 55, 2624–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, C.M.; Alexander, D.D.; Boushey, C.J.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Lappe, J.M.; LeBoff, M.S.; Liu, S.; Looker, A.C.; Wallace, T.C.; Wang, D.D. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and risk of fractures: An updated meta-analysis from the National Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporos. Int. 2016, 27, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitri, J.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Hu, F.B.; Pittas, A.G. Effects of vitamin D and calcium supplementation on pancreatic β cell function, insulin sensitivity, and glycemia in adults at high risk of diabetes: The Calcium and Vitamin D for Diabetes Mellitus (CaDDM) randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.K.; Lal, H. Role of Vitamin D Supplementation in Hypertension. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2011, 26, 88–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranić, L.; Mikolašević, I.; Milić, S. Vitamin D deficiency: Consequence or cause of obesity? Medicina 2019, 55, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Han, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y. Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on General and Central Obesity: Results from 20 Randomized Controlled Trials Involving Apparently Healthy Populations. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 76, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Chen, C.; Tang, W.; Jacobs, D.; Shikany, J.; He, K. Calcium Intake Is Inversely Related to the Risk of Obesity among American Young Adults over a 30-Year Follow-Up. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannu, P.K.; Calton, E.K.; Soares, M.J. Calcium and Vitamin D in Obesity and Related Chronic Disease, 1st ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 77. [Google Scholar]

- El-Hajj Fuleihan, G. Can the sunshine vitamin melt the fat? Metabolism 2012, 61, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lips, P. Interaction between Vitamin D and calcium. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 2012, 72, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goltzman, D.; Mannstadt, M.; Marcocci, C. Physiology of the Calcium-Parathyroid Hormone-Vitamin D Axis. In Vitamin D in Clinical Medicine; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 50, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, F.R.; Chedraui, P.; Fernández-Alonso, A.M. Vitamin D and aging: Beyond calcium and bone metabolism. Maturitas 2011, 69, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeliet, G.; Dermauw, V.; Bouillon, R. Vitamin D signaling in calcium and bone homeostasis: A delicate balance. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 29, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabesh, M.; Azadbakht, L.; Faghihimani, E.; Tabesh, M.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Effects of calcium–vitamin D co-supplementation on metabolic profiles in vitamin D insufficient people with type 2 diabetes: A randomised controlled clinical trial. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 2038–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabesh, M.; Azadbakht, L.; Faghihimani, E.; Tabesh, M.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Calcium-vitamin D cosupplementation influences circulating inflammatory biomarkers and adipocytokines in vitamin D-insufficient diabetics: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, E2485–E2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahn, D.; Dorbath, D.; Schilling, A.K.; Gildein, L.; Meier, C.; Vuille-dit-Bille, R.N.; Schmitt, J.; Kraus, D.; Fleet, J.C.; Hermanns, H.M.; et al. Intestinal vitamin D receptor modulates lipid metabolism, adipose tissue inflammation and liver steatosis in obese mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Mol. Basis Dis. 2019, 1865, 1567–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.Y.; Shin, Y.; Kim, J.H.; Zhu, S.; Jung, Y.S.; Han, S.N. Effects of high fat diet-induced obesity on vitamin D metabolism and tissue distribution in vitamin D deficient or supplemented mice. Nutr. Metab. 2020, 17, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marziou, A.; Philouze, C.; Couturier, C.; Astier, J.; Obert, P.; Landrier, J.F.; Riva, C. Vitamin d supplementation improves adipose tissue inflammation and reduces hepatic steatosis in obese c57bl/6j mice. Nutrients 2020, 12, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Cui, B.; Li, P.; Hua, F.; Lv, X.; Zhou, J.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, X. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 protects obese rats from metabolic syndrome via promoting regulatory T cell-mediated resolution of inflammation. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2018, 8, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, A.; Parra, P.; Laraichi, S.; Serra, F.; Palou, A. Calcium supplementation modulates gut microbiota in a prebiotic manner in dietary obese mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, E.P.S.; Moura, E.G.; Manhães, A.C.; Carvalho, J.C.; Nobre, J.L.; Oliveira, E.; Lisboa, P.C. Calcium reduces vitamin D and glucocorticoid receptors in the visceral fat of obese male rats. J. Endocrinol. 2016, 230, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, J.L.; Lisboa, P.C.; Peixoto-Silva, N.; Quitete, F.T.; Carvalho, J.C.; de Moura, E.G.; de Oliveira, E. Role of vitamin D in adipose tissue in obese rats programmed by early weaning and post diet calcium. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 810–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergeev, I.N.; Song, Q. High vitamin D and calcium intakes reduce diet-induced obesity in mice by increasing adipose tissue apoptosis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 1342–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Choudhuri, D. Dietary calcium regulates the insulin sensitivity by altering the adipokine secretion in high fat diet induced obese rats. Life Sci. 2020, 250, 117560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenchia, A.M.; Tosh, A.K.; Hillman, L.S.; Peterson, C.A. Correcting vitamin D insufficiency improves insulin sensitivity in obese adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. World Rev. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 109, 18–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblum, J.L.; Castro, V.M.; Moore, C.E.; Kaplan, L.M. Calcium and vitamin D supplementation is associated with decreased abdominal visceral adipose tissue in overweight and obese adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seldeen, K.L.; Pang, M.; Rodríguez-Gonzalez, M.; Hernandez, M.; Sheridan, Z.; Yu, P.; Troen, B.R. A mouse model of Vitamin D insufficiency: Is there a relationship between 25(OH) Vitamin D levels and obesity? Nutr. Metab. 2017, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drori, A.; Rotnemer-Golinkin, D.; Avni, S.; Drori, A.; Danay, O.; Levanon, D.; Tam, J.; Zolotarev, L.; Ilan, Y. Attenuating the rate of total body fat accumulation and alleviating liver damage by oral administration of vitamin D-enriched edible mushrooms in a diet-induced obesity murine model is mediated by an anti-inflammatory paradigm shift. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017, 17, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotte, C.; Weisstaub, A.; Bryk, G.; Olguin, M.C.; Posadas, M.; Lucero, D.; Schreier, L.; Pita Martín De Portela, M.L.; Zeni, S.N. Effect of dietary calcium (Ca) on body composition and Ca metabolism during growth in genetically obese (β) male rats. Eur. J. Nutr. 2013, 52, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsanathan, R.; Jain, S.K. Glutathione deficiency induces epigenetic alterations of vitamin D metabolism genes in the livers of high-fat diet-fed obese mice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roizen, J.D.; Long, C.; Casella, A.; O’Lear, L.; Caplan, I.; Lai, M.; Sasson, I.; Singh, R.; Makowski, A.J.; Simmons, R.; et al. Obesity Decreases Hepatic 25-Hydroxylase Activity Causing Low Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2019, 34, 1068–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shab-Bidar, S.; Neyestani, T.R.; Djazayery, A. Vitamin D receptor Cdx-2-dependent response of central obesity to Vitamin D intake in the subjects with type 2 diabetes: A randomised clinical trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 114, 1375–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehpour, A.; Hosseinpanah, F.; Shidfar, F.; Vafa, M.; Razaghi, M.; Dehghani, S.; Hoshiarrad, A.; Gohari, M. A 12-week double-blind randomized clinical trial of vitamin D3 supplementation on body fat mass in healthy overweight and obese women. Nutr. J. 2012, 11, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamberg, L.; Kampmann, U.; Stødkilde-Jørgensen, H.; Rejnmark, L.; Pedersen, S.B.; Richelsen, B. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on body fat accumulation, inflammation, and metabolic risk factors in obese adults with low vitamin D levels—Results from a randomized trial. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2013, 24, 644–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbaht, K.; Mercan, Y.; Kutlu, S.; Alpdemir, M.F.; Sezgin, T. Obesity with and without metabolic syndrome: Do vitamin D and thyroid autoimmunity have a role? Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 106, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, J.C.; Yalamanchili, V.; Smith, L.M. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on serum 25OHD in thin and obese women. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2013, 136, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subih, H.S.; Zueter, Z.; Obeidat, B.M.; al-Qudah, M.A.; Janakat, S.; Hammoh, F.; Sharkas, G.; Bawadi, H.A. A high weekly dose of cholecalciferol and calcium supplement enhances weight loss and improves health biomarkers in obese women. Nutr. Res. 2018, 59, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Cai, D.; Wang, Y.; Lin, N.; Hu, Q.; Qi, Y.; Ma, S.; Amarasekara, S. Calcium plus vitamin D3 supplementation facilitated Fat loss in overweight and obese college students with very-low calcium consumption: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, J.; Rahme, M.; Mahfoud, Z.R.; El-Hajj Fuleihan, G. Effect of high dose vitamin D supplementation on indices of sarcopenia and obesity assessed by DXA among older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Endocrine 2022, 76, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, C.R.; Taibi, A.; Chen, J.; Ward, W.E.; Comelli, E.M. Colonic Bacteroides are positively associated with trabecular bone structure and programmed by maternal Vitamin D in male but not female offspring in an obesogenic environment. Int. J. Obes. 2018, 42, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, C.R.; Chen, J.; Wen, B.; Sacco, S.M.; Taibi, A.; Ward, W.E.; Comelli, E.M. Maternal Vitamin D beneficially programs metabolic, gut and bone health of mouse male offspring in an obesogenic environment. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 1875–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canales, B.K.; Schafer, A.L.; Shoback, D.M.; Carpenter, T.O. Gastric bypass in obese rats causes bone loss, vitamin D deficiency, metabolic acidosis, and elevated peptide YY. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2014, 10, 878–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, K.S.; Park, C.Y.; Lee, S.E.; Kim, T.Y.; Han, S.N. The effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on markers related to the differentiation and maturation of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells from control and obese mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2020, 85, 108464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Buckendahl, P.; Sharma, K.; Miller, J.W.; Shapses, S.A. Expression of vitamin D hydroxylases and bone quality in obese mice consuming saturated or monounsaturated enriched high-fat diets. Nutr. Res. 2018, 60, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Cho, D.H.; Lee, G.Y.; An, J.H.; Han, S.N. The effects of dietary vitamin D supplementation and in vitro 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 treatment on autophagy in bone marrow-derived dendritic cells from high-fat diet-induced obese mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2021, 100, 108880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luger, M.; Kruschitz, R.; Winzer, E.; Schindler, K.; Grabovac, I.; Kainberger, F.; Krebs, M.; Hoppichler, F.; Langer, F.; Prager, G.; et al. Changes in Bone Mineral Density Following Weight Loss Induced by One-Anastomosis Gastric Bypass in Patients with Vitamin D Supplementation. Obes. Surg. 2018, 28, 3454–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamberg, L.; Pedersen, S.B.; Richelsen, B.; Rejnmark, L. The effect of high-dose vitamin D supplementation on calciotropic hormones and bone mineral density in obese subjects with low levels of circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D: Results from a randomized controlled study. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2013, 93, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Cosano, J.J.; Gracia-Marco, L.; Ubago-Guisado, E.; Migueles, J.H.; Mora-Gonzalez, J.; Escolano-Margarit, M.V.; Gómez-Vida, J.; Maldonado, J.; Ortega, F.B. Muscular fitness mediates the association between 25-hydroxyvitamin D and areal bone mineral density in children with overweight/obesity. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H.; Chen, Y.P.; Yang, X.; Li, C.Q. Vitamin D3 levels and NLRP3 expression in murine models of obese asthma: Association with asthma outcomes. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2018, 51, e6841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittichaicharoen, J.; Apaijai, N.; Tanajak, P.; Sa-nguanmoo, P.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C. Impaired Mitochondria and Intracellular Calcium Transients in the Salivary Glands of Obese Rats. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 42, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.S.; Park, C.Y.; Lee, G.Y.; Cho, D.H.; Kim, S.J.; Han, S.N. Effects of in vitro vitamin D treatment on function of T cells and autophagy mechanisms in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2021, 15, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhangi, M.A.; Mesgari-Abbasi, M.; Nameni, G.; Hajiluian, G.; Shahabi, P. The effects of vitamin D administration on brain inflammatory markers in high fat diet induced obese rats. BMC Neurosci. 2017, 18, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nameni, G.; Hajiluian, G.; Shahabi, P.; Farhangi, M.A.; Mesgari-Abbasi, M.; Hemmati, M.R.; Vatandoust, S.M. The Impact of Vitamin D Supplementation on Neurodegeneration, TNF-α Concentration in Hypothalamus, and CSF-to-Plasma Ratio of Insulin in High-Fat-Diet-Induced Obese Rats. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 61, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajiluian, G.; Nameni, G.; Shahabi, P.; Mesgari-Abbasi, M.; Sadigh-Eteghad, S.; Farhangi, M.A. Vitamin D administration, cognitive function, BBB permeability and neuroinflammatory factors in high-fat diet-induced obese rats. Int. J. Obes. 2017, 41, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.Y.; Park, C.Y.; Cha, K.S.; Lee, S.E.; Pae, M.; Han, S.N. Differential effect of dietary vitamin D supplementation on natural killer cell activity in lean and obese mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 55, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahn, D.; Dorbath, D.; Kircher, S.; Nier, A.; Bergheim, I.; Lenaerts, K.; Hermanns, H.M.; Geier, A. Beneficial effects of vitamin D treatment in an obese mouse model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benetti, E.; Mastrocola, R.; Chiazza, F.; Nigro, D.; D’Antona, G.; Bordano, V.; Fantozzi, R.; Aragno, M.; Collino, M.; Minetto, M.A. Effects of vitamin D on insulin resistance and myosteatosis in diet-induced obese mice. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0189707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.H.; Cho, D.H.; Lee, G.Y.; Kang, M.S.; Kim, S.J.; Han, S.N. Effects of vitamin d supplementation on CD4+ t cell subsets and mtor signaling pathway in high-fat-diet-induced obese mice. Nutrients 2021, 13, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Zhu, L.; Ge, Y.; Zhang, H. Improving effect of vitamin Dsupplementation on obesity-related diabetes in rats. Minerva Endocrinol. 2020, 45, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhangi, M.A.; Nameni, G.; Hajiluian, G.; Mesgari-Abbasi, M. Cardiac tissue oxidative stress and inflammation after vitamin D administrations in high fat- diet induced obese rats. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2017, 17, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhangi, M.A.; Mesgari-Abbasi, M.; Shahabi, P. Hepatic Complications of High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity: Reduction of Increased Hepatic Oxidative Stress and Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Concentration by Vitamin D Administration. Curr. Top. Nutraceutical Res. 2020, 18, 360–365. [Google Scholar]

- Conceição, E.P.S.; Moura, E.G.; Soares, P.N.; Ai, X.X.; Figueiredo, M.S.; Oliveira, E.; Lisboa, P.C. High calcium diet improves the liver oxidative stress and microsteatosis in adult obese rats that were overfed during lactation. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2016, 92, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Chandler, P.; Ng, K.; Manson, J.E.; Giovannucci, E. Obesity and efficacy of vitamin D3 supplementation in healthy black adults. Cancer Causes Control. 2020, 31, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.R.S.G.; Sanjuliani, A.F. Effects of weight loss from a high-calcium energy-reduced diet on biomarkers of inflammatory stress, fibrinolysis, and endothelial function in obese subjects. Nutrition 2013, 29, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lotfi-Dizaji, L.; Mahboob, S.; Aliashrafi, S.; Vaghef-Mehrabany, E.; Ebrahimi-Mameghani, M.; Morovati, A. Effect of vitamin D supplementation along with weight loss diet on meta-inflammation and fat mass in obese subjects with vitamin D deficiency: A double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. Clin. Endocrinol. 2019, 90, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, Z.; Kafeshani, M.; Tavasoli, P.; Zadeh, A.; Entezari, M. Effect of Vitamin D supplementation on weight loss, glycemic indices, and lipid profile in obese and overweight women: A clinical trial study. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesinovic, J.; Mousa, A.; Wilson, K.; Scragg, R.; Plebanski, M.; de Courten, M.; Scott, D.; Naderpoor, N.; de Courten, B. Effect of 16-weeks vitamin D replacement on calcium-phosphate homeostasis in overweight and obese adults. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 186, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, S.; Khadgawat, R.; Gahlot, M.; Khandelwal, D.; Oberoi, A.; Yadav, R.; Sreenivas, V.; Gupta, N.; Tandon, N. Effect of high-dose Vitamin D supplementation on beta cell function in obese Asian-Indian children and adolescents: A randomized, double blind, active controlled study. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 23, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniswamy, S.; Gill, D.; De Silva, N.M.; Lowry, E.; Jokelainen, J.; Karhu, T.; Mutt, S.J.; Dehghan, A.; Sliz, E.; Chasman, D.I.; et al. Could Vitamin D reduce obesity-Associated inflammation? Observational and Mendelian randomization study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 111, 1036–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Wilson, D.M.; Bachrach, L.K. Large doses of vitamin D fail to increase 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels or to alter cardiovascular risk factors in obese adolescents: A pilot study. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 57, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangge, H.; Zelzer, S.; Meinitzer, A.; Stelzer, I.; Schnedl, W.; Weghuber, D.; Fuchs, D.; Postolache, T.; Aigner, E.; Datz, C.; et al. 25OH-Vitamin D3 Levels in Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome—Unaltered in Young and not Correlated to Carotid IMT in All Ages. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21, 2243–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteghamati, A.; Aryan, Z.; Esteghamati, A.; Nakhjavani, M. Differences in vitamin D concentration between metabolically healthy and unhealthy obese adults: Associations with inflammatory and cardiometabolic markers in 4391 subjects. Diabetes Metab. 2014, 40, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moschonis, G.; Androutsos, O.; Hulshof, T.; Dracopoulou, M.; Chrousos, G.P.; Manios, Y. Vitamin D insufficiency is associated with insulin resistance independently of obesity in primary schoolchildren. The healthy growth study. Pediatr. Diabetes 2018, 19, 866–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirgon, O.; Cekmez, F.; Bilgin, H.; Eren, E.; Dundar, B. Low 25-hydroxyvitamin D level is associated with insulin sensitivity in obese adolescents with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2013, 7, e275–e283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorkin, J.D.; Vasaitis, T.S.; Streeten, E.; Ryan, A.S.; Goldberg, A.P. Evidence for threshold effects of 25-hydroxyvitamin D on glucose tolerance and insulin resistance in black and white obese postmenopausal women. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 734–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amini, Z.; Bryant, S.; Smith, C.; Singh, R.; Kumar, S. Is the serum vitamin d-parathyroid hormone relationship influenced by obesity in children? Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2013, 80, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marziou, A.; Aubert, B.; Couturier, C.; Astier, J.; Philouze, C.; Obert, P.; Landrier, J.-F.; Riva, C. Combined Beneficial Effect of Voluntary Physical Exercise and Vitamin D Supplementation in Diet-induced Obese C57BL/6J Mice. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2021, 53, 1883–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandan, P.; Nayanatara, A.K.; Poojary, R.; Bhagyalakshmi, K.; Nirupama, M.; Kini, R.D. Protective Role of Co-administration of Vitamin D in Monosodium Glutamate Induced Obesity in Female Rats. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2018, 110, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcotorchino, J.; Tourniaire, F.; Astier, J.; Karkeni, E.; Canault, M.; Amiot, M.J.; Bendahan, D.; Bernard, M.; Martin, J.C.; Giannesini, B.; et al. Vitamin D protects against diet-induced obesity by enhancing fatty acid oxidation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 1077–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.S.; Park, C.Y.; Seo, Y.K.; Woo, S.H.; Kim, D.Y.; Han, S.N. Vitamin D supplementation partially affects colonic changes in dextran sulfate sodium–induced colitis obese mice but not lean mice. Nutr. Res. 2019, 67, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, E.; Yan, C.; Zhao, L.; Wang, X.; Qiu, Y.; Shen, H.; Sun, X.; Feng, Z.; et al. Coral calcium hydride prevents hepatic steatosis in high fat diet-induced obese rats: A potent mitochondrial nutrient and phase II enzyme inducer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016, 103, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, M.; Mitchell, P.L.; Pilon, G.; Varin, T.; Hénault, L.; Rolin, J.; McLeod, R.; Gill, T.; Richard, D.; Vohl, M.C.; et al. Salmon peptides limit obesity-associated metabolic disorders by modulating a gut-liver axis in vitamin D-deficient mice. Obesity 2021, 29, 1635–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, C.L.; Emond, J.A.; Flatt, S.W.; Heath, D.D.; Karanja, N.; Pakiz, B.; Sherwood, N.E.; Thomson, C.A. Weight loss is associated with increased serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in overweight or obese women. Obesity 2012, 20, 2296–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, A.E.; Flynn, M.G.; Pinkston, C.; Markofski, M.M.; Jiang, Y.; Donkin, S.S.; Teegarden, D. Impact of vitamin D supplementation during a resistance training intervention on body composition, muscle function, and glucose tolerance in overweight and obese adults. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 32, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faghih, S.H.; Abadi, A.R.; Hedayati, M.; Kimiagar, S.M. Comparison of the effects of cows’ milk, fortified soy milk, and calcium supplement on weight and fat loss in premenopausal overweight and obese women. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2011, 21, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, A.E.; Flynn, M.G.; Pinkston, C.; Markofski, M.M.; Jiang, Y.; Donkin, S.S.; Teegarden, D. Vitamin D supplementation during exercise training does not alter inflammatory biomarkers in overweight and obese subjects. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 112, 3045–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifan, P.; Ziaee, A.; Darroudi, S.; Rezaie, M.; Safarian, M.; Eslami, S.; Khadem-Rezaiyan, M.; Tayefi, M.; Mohammadi Bajgiran, M.; Ghazizadeh, H.; et al. Effect of low-fat dairy products fortified with 1500IU nano encapsulated vitamin D3 on cardiometabolic indicators in adults with abdominal obesity: A total blinded randomized controlled trial. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2021, 37, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinet, A.; Morrissey, C.; Perez-Martin, A.; Goncalves, A.; Raverdy, C.; Masson, D.; Gayrard, S.; Carrere, M.; Landrier, J.F.; Amiot, M.J. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on microvascular reactivity in obese adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 2474–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naderpoor, N.; Mousa, A.; de Courten, M.; Scragg, R.; de Courten, B. The relationship between 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration and liver enzymes in overweight or obese adults: Cross-sectional and interventional outcomes. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 177, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Arroyo, S.; Hernández-Aguilera, A.; de Vries, M.A.; Burggraaf, B.; van der Zwan, E.; Pouw, N.; Joven, J.; Cabezas, M.C. Effect of vitamin D3 on the postprandial lipid profile in obese patients: A non-targeted lipidomics study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, S.S.; Pittas, A.G.; Palermo, N.J. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation to improve glycaemia in overweight and obese African Americans. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2012, 14, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacko, S.J.; Pauwaa, S.; Barengolts, E.; Ciubotaru, I.; Kansal, M.M. Vitamin D Attenuates Left Atrial Volume Changes in African American Males with Obesity and Prediabetes. Echocardiography 2016, 33, 681–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hajj, C.; Walrand, S.; Helou, M.; Yammine, K. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Inflammatory Markers in Non-Obese Lebanese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Dong, Y.; Bhagatwala, J.; Raed, A.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, H. Vitamin D3 Supplementation Increases Long-Chain Ceramide Levels in Overweight/Obese African Americans: A Post-Hoc Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefalo, C.M.A.; Conte, C.; Sorice, G.P.; Moffa, S.; Sun, V.A.; Cinti, F.; Salomone, E.; Muscogiuri, G.; Brocchi, A.A.G.; Pontecorvi, A.; et al. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Obesity-Induced Insulin Resistance: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Obesity 2018, 26, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motlaghzadeh, Y.; Sayarifard, F.; Allahverdi, B.; Rabbani, A.; Setoodeh, A.; Sayarifard, A.; Abbasi, F.; Haghi-Ashtiani, M.T.; Rahimi-Froushani, A. Assessment of vitamin D status and response to vitamin D3 in obese and non-obese iranian children. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2016, 62, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldurthy, V.; Wei, R.; Oz, L.; Dhawan, P.; Jeon, Y.H.; Christakos, S. Vitamin D, calcium homeostasis and aging. Bone Res. 2016, 4, 16041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.P.; Dunn, T.N.; Drayton, J.B.; Oort, P.J.; Adams, S.H. A high calcium diet containing nonfat dry milk reduces weight gain and associated adipose tissue inflammation in diet-induced obese mice when compared to high calcium alone. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.D.; Secombes, K.R.; Thies, F.; Aucott, L.S.; Black, A.J.; Reid, D.M.; Mavroeidi, A.; Simpson, W.G.; Fraser, W.D.; Macdonald, H.M. A parallel group double-blind RCT of vitamin D3 assessing physical function: Is the biochemical response to treatment affected by overweight and obesity? Osteoporos. Int. 2014, 25, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehpour, A.; Shidfar, F.; Hosseinpanah, F.; Vafa, M.; Razaghi, M.; Amiri, F. Does vitamin D3 supplementation improve glucose homeostasis in overweight or obese women? A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Diabet. Med. 2013, 30, 1477–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeziński, M.; Jankowska, A.; Słomińska-Frączek, M.; Metelska, P.; Wiśniewski, P.; Socha, P.; Szlagatys-Sidorkiewicz, A. Long-term effects of vitamin d supplementation in obese children during integrated weight–loss programme—A double blind randomized placebo–controlled trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.W.; Eller, L.K.; Parnell, J.A.; Doyle-Baker, P.K.; Edwards, A.L.; Reimer, R.A. Effect of a dairy-and calcium-rich diet on weight loss and appetite during energy restriction in overweight and obese adults: A randomized trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerksick, C.M.; Roberts, M.D.; Campbell, B.I.; Galbreath, M.M.; Taylor, L.W.; Wilborn, C.D.; Lee, A.; Dove, J.; Bunn, J.W.; Rasmussen, C.J.; et al. Differential impact of calcium and vitamin d on body composition changes in post-menopausal women following a restricted energy diet and exercise program. Nutrients 2020, 12, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Schoor, N.; Lips, P. Worldwide Vitamin D Status. Vitam. D Fourth Ed. 2017, 2, 15–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balk, E.M.; Adam, G.P.; Langberg, V.N.; Earley, A.; Clark, P.; Ebeling, P.R.; Mithal, A.; Rizzoli, R.; Zerbini, C.A.F.; Pierroz, D.D.; et al. Global dietary calcium intake among adults: A systematic review. Osteoporos. Int. 2017, 28, 3315–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Meer, I.M.; Middelkoop, B.J.C.; Boeke, A.J.P.; Lips, P. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among Turkish, Moroccan, Indian and sub-Sahara African populations in Europe and their countries of origin: An overview. Osteoporos. Int. 2011, 22, 1009–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakishun, N.; van Vliet, M.; von Rosenstiel, I.; Weijer, O.; Diamant, M.; Beijnen, J.; Brandjes, D. High prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency in Dutch multi-ethnic obese children. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2015, 174, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guessous, I.; Dudler, V.; Glatz, N.; Theler, J.M.; Zoller, O.; Paccaud, F.; Burnier, M.; Bochud, M. Vitamin D levels and associated factors: A population-based study in Switzerland. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2012, 142, w13719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeum, K.J.; Song, B.C.; Joo, N.S. Impact of geographic location on vitamin D status and bone mineral density. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lucia, F.; Minisola, S.; Romagnoli, E.; Pepe, J.; Cipriani, C.; Scillitani, A.; Parikh, N.; Rao, D.S. Effect of gender and geographic location on the expression of primary hyperparathyroidism. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2013, 36, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heravi, A.S.; Michos, E.D. Vitamin D and Calcium Supplements: Helpful, Harmful, or Neutral for Cardiovascular Risk? Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc. J. 2019, 15, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silk, L.N.; Greene, D.A.; Baker, M.K. The effect of calcium or calcium and Vitamin D supplementation on bone mineral density in healthy males: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2015, 25, 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omotayo, M.O.; Dickin, K.L.; O’Brien, K.O.; Neufeld, L.M.; De Regil, L.M.; Stoltzfus, R.J. Calcium supplementation to prevent preeclampsia: Translating guidelines into practice in low-income countries. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).