Abstract

Preconception and prenatal nutrition is critical for fetal brain development. However, its associations with offspring neurodevelopmental disorders are not well understood. This study aims to systematically review the associations of preconception and prenatal nutrition with offspring risk of neurodevelopmental disorders. We searched the PubMed and Embase for articles published through March 2019. Nutritional exposures included nutrient intake or status, food intake, or dietary patterns. Neurodevelopmental outcomes included autism spectrum disorders (ASD), attention deficit disorder-hyperactivity (ADHD) and intellectual disabilities. A total of 2169 articles were screened, and 20 articles on ASD and 17 on ADHD were eventually reviewed. We found an overall inverse association between maternal folic acid or multivitamin supplementation and children’s risk of ASD; a meta-analysis including six prospective cohort studies estimated an RR of ASD of 0.64 (95% CI: 0.46, 0.90). Data on associations of other dietary factors and ASD, ADHD and related outcomes were inconclusive and warrant future investigation. Future studies should integrate comprehensive and more objective methods to quantify the nutritional exposures and explore alternative study design such as Mendelian randomization to evaluate potential causal effects.

1. Introduction

Maternal nutrition is critical for fetal brain development. Maternal diet prior to pregnancy is important for optimizing nutritional status which plays a vital role in maintaining a healthy pregnancy and supporting the developing fetus [1]. Nutrition around the time of conception is important for gamete function and placental development [2]. Starting 2–3 weeks after fertilization, the embryo undergoes orchestrated processes of neuronal proliferation and migration, synapse formation, myelination, and apoptosis to develop the fetal brain [3]. In this period of rapid development, the brain has heightened sensitivity to the environment, where perturbation may predispose the fetus to postnatal neurodevelopmental disorders [4,5]. Overall, supply of nutrients during the preconception and prenatal periods not only provides the basic building blocks for the brain [6], but may also “program” the brain through epigenetic mechanisms to confer risk or resilience to neurological conditions later in life [7]. The modifiable nature of maternal nutrition during sensitive periods potentially offers opportunities for intervention.

Several nutrients have previously been identified to have a critical role in prenatal neurodevelopment. For example, folate is an essential co-factor in one-carbon metabolism responsible for DNA and RNA synthesis and DNA methylation—processes that are particularly important during periods of rapid growth and development. Inadequate folate intake has been linked to altered DNA methylation [8,9] and compromised fetal brain development [10,11], particularly in animal studies. Preconception and early pregnancy supplementation of folic acid—the synthetic form of folate—was found effective in preventing neural tube defects [12]. In addition to folate, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), particularly arachidonic acid (AA) of the omega-6 (n-6) family and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) of the omega-3 (n-3) family, are structural components of neuronal membrane phospholipids and the myelin sheath insulating the neuronal axons [13]. PUFAs accumulate rapidly in the brain starting in the third trimester and continuing into early postnatal life [14], and the membrane PUFA composition is mainly dependent on maternal dietary supply of DHA [15]. Restriction of DHA and its precursors in the perinatal period negatively impact cognitive and behavioral outcomes in animal studies [16,17].

Some minerals are also known to play important roles in prenatal neurodevelopment. For example, iron is essential for the regulation of neuronal energy metabolism during development; deficiency affects the structure and function of fetal hippocampus, compromising learning and memory [18]. Similarly, iodine is necessary to produce thyroid hormones which regulate brain growth and development; deficiency during the prenatal period results in cognitive deficit [19]. While not a nutrient, caffeine, a psychoactive substance widely consumed through coffee and tea, improves alertness by blocking adenosine receptors in the brain. Prenatal and early postnatal exposure to caffeine alters brain neurochemistry and behavior in animal studies [20]. In addition to individual nutrients and substance, foods and dietary patterns may capture the combined and interactive effects of nutrients in prenatal neurodevelopment.

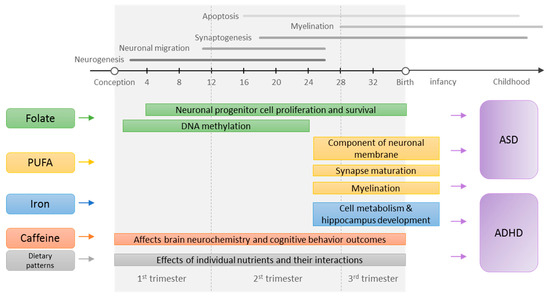

In the past decade, accumulating evidence from human epidemiological studies support the link between maternal nutrition and offspring cognitive and behavioral abilities [21,22,23,24,25]. Yet, it is unclear whether maternal nutrition is relevant to the risk of clinically defined neurodevelopmental disorders, which are characterized by deficits that produce impairments in daily functioning. A comprehensive and critical review of the evidence may shed light on the question. Limited studies previously reviewed evidence on maternal folic acid intake and offspring autism spectrum disorder (ASD) risk [26,27]; however, an updated review with a comprehensive critique of the evidence is needed. Furthermore, much of the evidence on maternal nutrition and offspring attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) risk has not been reviewed. Lastly, critical questions regarding the most sensitive time windows (i.e., before vs. during pregnancy) for nutritional exposures remain unanswered. To address these critical knowledge gaps, we conducted a systematic review of epidemiologic studies examining the association of maternal nutrition before and during pregnancy with the risk of offspring neurodevelopmental disorders; we focused on dietary factors including supplements to inform potential public health interventions specific to maternal diet. To provide quantitative syntheses of evidence, we also performed meta-analyses whenever the data were available. A summary of proposed mechanisms in which preconception and prenatal nutrition affects risks of ASD and ADHD and relevant sensitive windows are presented in a schematic figure (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed mechanisms in which preconception and prenatal nutrition affects the risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The neurodevelopmental timelines were adapted from the previous publications [3,28]. PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acids.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The systematic review included studies investigating associations of nutrition before or during pregnancy with offspring major neurodevelopmental disorders, including ASD, ADHD, and intellectual disability (ID). Maternal nutrition was evaluated at multiple levels: nutrient intake, food intake, or dietary patterns. Clinical diagnosis, a positive screening outcome, or a continuous measure of the traits or symptoms of the disorder were considered as outcomes. The studies were conducted in human populations, of case-control, cohort, or experimental design, and published in the English language. Studies were excluded if the exposures were not reflective of maternal dietary intake, such as teratogens (e.g., alcohol), chemicals, certain circulating biomarkers that are not directly reflective of maternal intake (e.g., 25-hydroxyvitamin D and ferritin), biomarkers in umbilical cord blood, or dietary counseling without quantification of actual maternal diet. We also excluded studies where outcomes were not reflective of neurodevelopmental disorders (continuous measures of Intelligence quotient (IQ), or suboptimal IQ defined by a non-clinical cutoff), outcomes were secondary to structural birth defects (e.g., neural tube defect) or chromosomal disorders (e.g., Down Syndrome), relevant associations were not reported, or full-texts were not available. Other neurodevelopmental disorders (i.e., communication disorders, motor disorders, and specific learning disorders) were not covered in this review, as a pilot search found very few epidemiologic studies investigating these disorders in association with maternal nutrition.

2.2. Literature Search, Screening and Abstraction

We searched PubMed and Embase on 27 March 2019. Search strategies were developed a priori for each database with assistance from a librarian. The search targeted title, abstract, and subject headings. Search terms consisted of neurodevelopmental disorders (either the general term or specific terms for ASD, ID, or ADHD), nutrition (nutrients, foods, or dietary patterns), prenatal or preconception periods, and observational or experimental design, combined using the Boolean Operator “AND”; additional search terms were used to exclude animal studies. The search strategy and search history are presented in Table S1.

After the systematic search, we screened the title and abstract of the records for eligibility, and then assessed the full-text of the retained records for final inclusion decisions. We also examined the bibliographies of existing literature reviews on maternal nutrition and neurodevelopmental disorders to identify additional articles not covered in the systematic search. We abstracted relevant data in the included articles using a standardized form.

2.3. Meta-Analysis

We conducted meta-analyses of associations between specific nutritional exposures and neurodevelopmental outcomes whenever three or more relevant independent estimates were available. The analysis pooled relative risks (RRs) and odds ratios (ORs) estimated from cohort studies; OR is a reasonable approximation of RR in these studies as both ASD (prevalence 1–5%) [29] and ADHD (prevalence 5–10%) [30] are relatively rare. Estimates from case-control studies were not pooled with those from cohort studies due to differences in study design and retrospective recall of the nutritional exposures in these studies (all the case-control studies are retrospective); sensitivity analysis including estimates from the case-control studies did not change the findings substantively. Estimates of hazard ratio were not pooled with the RRs, as it is a conceptually different measure [31]. Pooled effect sizes were estimated using DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model. Studies reporting the diagnosis and the screening outcomes of neurodevelopmental disorders were meta-analyzed separately. Attempts were made to separate the effects of specific nutrients from multivitamins, and between exposures at different time periods (e.g., before pregnancy and during pregnancy), whenever possible. The meta-analysis was performed in Stata version 14 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) [32].

2.4. Quality Assessment

While generic tools to evaluate the quality of observational studies exists, these tools may not sufficiently address the methodological concerns important for the topic of interest and the type of studies included. As such, we critiqued the methodological quality of the included studies throughout the narrative review whenever relevant. We also discussed common issues across exposures and outcomes in a separate section following the reviews, with an emphasis for future directions.

3. Results and Commentary

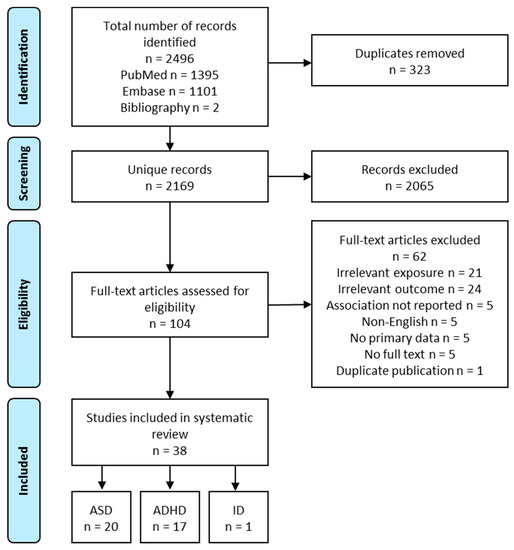

A total of 2167 unique records were obtained from the systematic literature search. After screening the titles and abstracts, 102 relevant records remained. After the full-text review, 36 articles were included. Two additional articles were identified from the bibliographies of existing literature reviews, resulting in a total of 38 studies. Overall, 20 studies reported outcomes related to ASD, 17 ADHD, and 1 ID (Figure 2). The following review focuses on ASD and ADHD. Exposures in these studies included vitamins and minerals (i.e., folate, iron, calcium, and iodine), fatty acids (i.e., PUFA), foods (i.e., fish, fruits), supplements (i.e., multivitamins), and dietary patterns. Nutrients intake or status were grouped together with relevant food sources (e.g., folate with multivitamins, PUFA with seafood) to facilitate the interpretation of the findings. Nutrients or foods reported only in a single study were not reviewed below.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of study selection process, intellectual disability (ID).

3.1. Maternal Nutrition and ASD Risk

The characteristics and main findings of the studies on the associations between maternal nutrition and ASD are presented in Table 1. Of the 20 studies, 14 are prospective study and 6 are retrospective studies. These studies were conducted in the USA, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, The Netherlands, Spain, Israel, and China.

Table 1.

Studies on maternal nutrition and offspring ASD risk or traits.

3.1.1. Maternal Folate Intake/Status, Multivitamin Intake and Offspring ASD Risk

Fourteen studies examined the association of folic acid supplementation, folate status, or multivitamin intake in relation to offspring ASD risk. Among them, ten are prospective cohort studies [33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42], and four are retrospective case-control studies [35,43,45,53]. Studies on folate and multivitamins were combined as it is difficult to separate the two exposures. Among the 12 independent studies [33,34,35,36,37,38,40,41,42,43,53] including 594,229 children (8851 ASD cases), nine found a significant inverse association between maternal folic acid or multivitamin intake during pregnancy (with or without pre-pregnancy use) and offspring ASD risk [33,34,35,37,38,40,41,42,44,45,46], one a null association [37], one a significant positive association [43], and one a curve-linear association with modest intake/status associated with lowest ASD risk [36].

Of the nine studies reporting an inverse association between maternal folic acid or multivitamin intake/status during pregnancy and offspring ASD risk [33,34,35,37,38,40,41,42,45], four were large prospective cohort studies which identified ASD cases through population-based patient registries [38,41,42] or medical records of large health care organizations [34]; the ASD cases were either confirmed by specialist providers [34,41] or independently validated [38,42]. These studies included very large sample sizes (45,000–270,000 participants) and contributed the greatest weight to the overall evidence. Three were smaller cohort studies which assessed ASD risk within the study using validated instruments for ASD diagnosis [33] or screening [40,46]. Two were retrospective case-control studies where ASD cases were identified from service registries [35,44].

There are two common methodological concerns about these studies. First, there is potential measurement error in folic acid or multivitamin intake, which were generally assessed by self-report [33,35,42] or administrative records [34,38,41]. Of note, two studies with additional data on whole blood/plasma folate levels found the self-reported measure, but not the biomarker measure, to be associated with lower ASD risk [40,46]. The inconsistent findings may be due to measurement error in either measure, or differences in measurement timing. Second, there is potential bias due to residual confounding. Women who took folic acid supplements generally had higher socioeconomic status, healthier lifestyle, and lower BMI [33,37,38,42]; some of these factors, such as a lower BMI, may contribute to lower risk of ASD [54]. These factors were not always adjusted for, making the results subject to residual confounding.

Despite the methodological concerns, additional data support an inverse association between maternal folate status and ASD risk. For example, the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene encodes the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, a rate-limiting enzyme responsible for converting folate to its bioactive form for methylation reactions [55]; the minor T allele at loci MTHFR 677 is known to confer higher susceptibility to inadequate folate status [55]. In one study, maternal folic acid supplementation was associated with a much greater reduction of children’s ASD risk when the mother and/or the child had at least one T allele, but the association was null when neither had a T allele [44]. Furthermore, two studies found maternal folic acid supplementation to be specifically associated with a lower risk of ASD, but not associated with the risk of developmental disorders other than ASD [33,44]. If maternal folic acid supplementation was spuriously associated with ASD due to residual confounding, it is likely that it would also show an association with other developmental disorders. Similarly, one study also found the risk of ASD to be specifically associated with folic acid intake, but not fish oil intake [42].

In contrast to the overall finding of an inverse association between folic acid or multivitamin intake/status and ASD risk, a study among 92,676 children in the Danish National Birth Cohort (DNBC) did not find a significant association between folic acid supplementation and ASD risk [37]. Possible explanations include better folate status without supplementation, lower frequency of T alleles at MTHFR 677, and insufficient doses of folic acid in the supplements [37,39]. In addition, a study including 1257 children in the Boston Birth Cohort found both low (<2 times/week) and high (>5 times/week) frequencies of multivitamin intake were associated with an elevated risk of ASD, compared to moderate intake (3–5 times/week) [36]. The increased risk associated with high frequencies of folic acid intake may be a result of the above normal level of folate in the study sample [36].

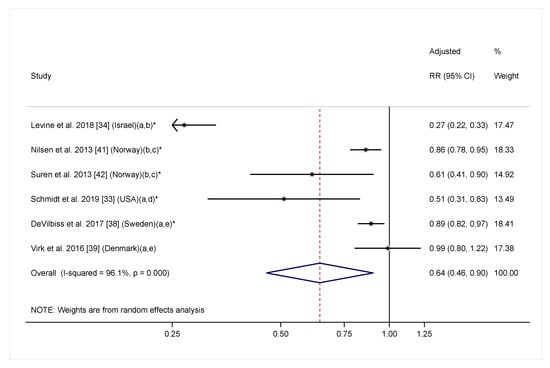

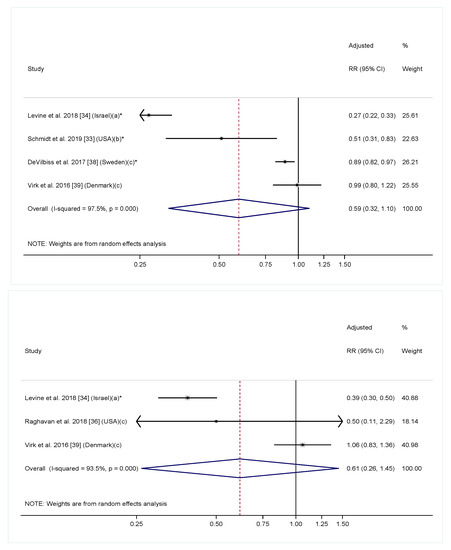

In the meta-analysis including six cohort studies reporting a linear relationship between maternal folic acid/multivitamin intake with offspring ASD diagnosis, maternal folic acid/multivitamin intake was significantly associated with a 36% reduction in offspring ASD risk (Figure 3. RR = 0.64, 95% CI: 0.46, 0.90). The heterogeneity across studies was highly significant (I2 = 96.1%, p < 0.001). To further explore the effect of timing on the association, we conducted additional meta-analyses including four studies examining folic acid/multivitamin supplementation during pregnancy only [33,34,38,39], and three studies examining supplementation before pregnancy only [34,36,39]. The overall effect estimates had a similar direction and magnitude compared to the main analysis. However, the confidence intervals were wider, and the associations were not significant for either analyses, likely due to fewer included studies (Figure 4). Of note, most studies that investigated folic acid/multivitamin supplementation during pregnancy were specific to early pregnancy [33,38,39]. Furthermore, studies that investigated supplementation at multiple times during pregnancy consistently found that supplementation in the first or second months of pregnancy, but not later in pregnancy, was associated with lower ASD risk [33,42,44]. We also separately performed meta-analyses for multivitamin or prenatal vitamins and folic acid-specific supplements. The overall effect estimates in both groups were similar to the main analysis, but not significant (Figure S1).

Figure 3.

Adjusted relative risk (RRs) of offspring ASD risk associated with maternal intake of supplement containing folic acid, multivitamin or prenatal vitamin during pregnancy (with or without pre-pregnancy use). The overall effect size was estimated using random effects models weighted by inverse variance of each study. One data point was included for each study. Estimates covering any period during pregnancy were included. When estimates for folic acid and multivitamin were both available, the one for folic acid were selected. Notes: (a) Exposure during pregnancy; (b) Intake of supplement containing folic acid vs. no; (c) Exposure before and during pregnancy; (d) Folic acid intake ≥600 mcg/day vs. <600 mcg/day; (e) Intake of multivitamin vs. never/rarely. * p < 0.05.

Figure 4.

Adjusted relative risk (RRs) of offspring risk of ASD associated with maternal intake of supplement containing folic acid, multivitamin or prenatal vitamin during (top) and before (bottom) pregnancy. The overall effect size was estimated using random effects models weighted by inverse variance of each study. Notes: (a) Intake of supplement containing folic acid vs. no; (b) Folic acid intake ≥600 mcg/day vs. <600 mcg/day; (c) Intake of multivitamin vs. never/rarely. * p < 0.05.

Although folic acid is the most widely hypothesized ingredient in multivitamin related to the risk of offspring ASD risk in existing studies, it cannot be explicitly concluded that folic acid was responsible for the observed association yet. Several biological mechanisms support the potential effect of folic acid on reducing offspring ASD risk though. Changes in maternal folate intake result in altered DNA methylation of some genes such as IGF2 in offspring [8,9], which has been implicated in neurodevelopmental disorders [56,57]. Furthermore, inadequate folate intake affects offspring brain development in animal models through decreasing progenitor cell proliferation [10] and increasing apoptosis [10,11], leading to impaired short-term memory [11]. On the other hand, more than 50 prenatal multivitamins that include folic acid also contain PUFAs [58], for example, and PUFAs are also known to affect prenatal neurodevelopment (see a summary in the introduction section).

In summary, data from the systematic review suggested an overall inverse association between prenatal folic acid/multivitamin supplementation and ASD risk. We also observed large heterogeneity in the association between folic acid/multivitamin intake and ASD risk across studies, which may reflect differences in background nutrient status [59], supplementation dose [39], and genetic polymorphism in nutrient metabolism [60]. Compared with the two earlier reviews [26,27], the present review included six additional recently published articles, thus, providing more conclusive findings. Future studies should simultaneously examine folic acid and other nutrients contained in multivitamins in order to identify the putative nutrients associated with offspring ASD risk; they should also utilize dietary folate intakes in conjunction with folate biomarkers which are more objective.

3.1.2. Maternal Iron Intake and Offspring ASD Risk

Three studies reported maternal iron supplementation and offspring ASD risk—a in large cohort of 273,107 children in Sweden [38], a small cohort of 332 children who had siblings with ASD in the US [33], and 520 ASD cases and 346 typically developing controls in the US [47]. These studies did not find an association between early pregnancy iron supplementation and ASD, regardless of the specific exposure (iron-specific supplementation, any iron supplementation, total iron supplementation). Only the retrospective study in the US examined iron supplementation later in pregnancy, and it found suggestive evidence of an association between total iron supplementation and iron-specific supplementation in the second and third trimester and a lower ASD risk, which did not reach significance. In addition, it also found a significant association between the exposures during breastfeeding and a lower ASD risk. In summary, studies on iron supplementation intakes in pregnancy and offspring ASD risk are limited. Available data do not suggest an association between prenatal iron supplementation and ASD risk.

3.1.3. Maternal PUFA Intake or Status, Seafood Intake and Offspring ASD Risk

Two studies examined maternal PUFA intake or status in relation to offspring ASD risk or traits. Among 18,045 children in the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII) in the US, total and n-6 PUFA intake before pregnancy were all significantly and inversely associated with children’s risk of ASD diagnosis as reported by mothers, whereas n-3 PUFA was not significantly associated with ASD risk [48]. In contrast, among 4624 children in the generation R study in The Netherlands, plasma n-6 PUFA levels in mid-pregnancy were significantly and positively associated with children’s ASD traits measured by Social Response Scale (SRS), the ratio of n-3 to n-6 PUFA was inversely associated with the outcome. Similar to NHSII study, plasma n-3 PUFA levels were not associated with the outcome [49]. Both studies controlled for a comprehensive set of potential confounders including other aspects of diet [48] and dietary supplements [48,49]. Both n-3 and n-6 PUFA are necessary for prenatal brain development [13]; however, an elevated n-6 to n-3 PUFA ratio—characteristic of modern western diet [61]—could potentiate inflammatory processes [62]. Discrepant findings from the two studies may be due to the use of absolute versus relative concentrations of n-3 and n-6 PUFA levels, or differences in the timing of the exposure (before pregnancy vs. mid-pregnancy) and outcome measures (clinical diagnosis vs. trait).

Fish is the main dietary source of DHA—the n-3 PUFA most relevant for brain development [15]. In secondary analysis of the above-mentioned studies on PUFA intake/status, maternal fish intake was not associated with ASD diagnosis/traits [48,49]. In contrast, two other studies suggested a potential inverse association between maternal fish intake and offspring ASD risk [42,51]. Among 1589 children in the Spanish INMA study [51], maternal total seafood intake in the first trimester was associated with lower autistic traits measured by Childhood Asperger Syndrome Test; similar associations were observed for large fatty fish and lean fish. Another study of 108 ASD cases and 108 typically developing controls in China [50] found maternal “habit” (>3 times/week) of eating grass carp reported four to 17 years after delivery to be associated with a lower risk of ASD. However, the validity of the food frequency questionnaire in recalling diet after many years was not reported. Lastly, in one study among 85,176 children in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa) [42], fish oil supplementation before and in early pregnancy was not associated with ASD risk.

In conclusion, findings of the associations between maternal PUFA or fish intake and ASD risk are inconclusive. Heterogeneity in the PUFA measurement or assessment (i.e., absolute vs. relative concentrations, intake vs. status) and ASD (i.e., clinical diagnosis vs. traits, intake vs. status) made it difficult to compare findings across studies. Furthermore, recall bias and potential residual confounding are also of concern.

3.1.4. Maternal Dietary Patterns and Offspring risk of ASD

Two studies reported associations between maternal dietary patterns and ASD risk. Among 325 children in the Newborn Epigenetics Study in the US [52], higher periconception Adherence to the Mediterranean diet was associated with a lower risk of ASD assessed by the Infant Toddler Social Emotional Assessment; the association became non-significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons. Among 374 ASD cases and 354 typically developing controls in the Autism Clinical and Environmental Database in China, maternal recall three to six years after delivery of a “mostly meat” and a “mostly vegetable” dietary pattern during pregnancy were both associated with a higher risk of ASD in children compared to a “both meat and vegetable” dietary pattern [35]. However, it appears that the dietary pattern was only assessed using a single question, and a specific definition of each dietary pattern was not given. Thus, it remains inconclusive if maternal dietary patterns are associated with offspring risk of ASD. More studies on this topic are needed in the future.

3.2. Maternal Nutrition and ADHD Risk

Characteristics and main findings of studies assessing the association between maternal nutrition and ADHD are presented in Table 2. Of the 17 studies, 16 are prospective observational study, and one was a randomized controlled trial. These studies were conducted in the UK, France, Spain, The Netherlands, Norway, Denmark, New Zealand, Japan, Brazil, and Mexico.

Table 2.

Studies on maternal nutrition and offspring ADHD risk or symptoms.

3.2.1. Maternal Folate Intake/Status, Multivitamin Intake and Offspring ADHD Risk

Three studies examined maternal folic acid supplementation in relation to offspring ADHD risk or symptoms [63,64,65,66,67], with most reporting null findings. Specifically, maternal folic acid-specific supplementation before and in early pregnancy was not associated with clinical diagnosis of hyperkinetic disorders or ADHD medication use in a large study of 35,059 children in the DNBC [65], although it was associated with a lower risk of hyperactivity-inattention problems as measured by the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) among a subgroup of children followed to age seven. Similarly, maternal intake of any folic acid supplementation before or in early pregnancy was not associated with the risk of the hyperactivity-inattention problem among 6247 children in the Growing Up in New Zealand Study [63] and 420 children in the Menorca cohort in Spain [66].

One study examined maternal folate intake from food in relation to offspring ADHD risk. In the Japanese study including 1199 children in the Kyushu Okinawa Maternal and Child Health Study (KOMCHS) [64], higher intake of folate from food during pregnancy was associated with a non-significant reduction in children’s risk of the hyperactivity-inattention problems (p-trend = 0.10), but folic acid supplementation was not accounted for. Lastly, one study examined folate status and total folate intake in relation to ADHD risk. In this small study including 136 children in the UK [67], early pregnancy red blood cell folate concentration and total folate intake from food and supplements, but not late pregnancy intake, were inversely associated with hyperactivity-inattention score. However, unlike the larger studies above, this study only adjusted for a limited set of covariates; residual confounding from maternal lifestyle factors was possible. In summary, no convincing evidence supports an association between folate intake from food or supplements and ADHD risk.

Among the studies previously mentioned, three also assessed the association between maternal multivitamin intake and child ADHD risk [63,65,66]. Overall, the findings are inconsistent. Maternal multivitamin intake was associated with a lower risk of hyperkinetic disorders and ADHD medication in the DNBC [65], but it was not associated with the hyperactivity-inattention problems in the Growing up in New Zealand Study [63]. Maternal intake of multivitamins containing no folic acid was associated with a non-significant reduction in risk of the hyperactivity-inattention problem in the Spanish Menorca cohort (OR = 0.24, 95% CI: 0.05, 1.31) [66]. However, the composition of such multivitamins was not clear. More studies are needed to assess this association further and to examine nutrients other than folate that may be related to ADHD risk.

3.2.2. Maternal PUFA and Seafood Intake and Offspring ADHD Risk

Two studies examined maternal PUFA intake in relation to children’s ADHD risk and findings did not support a significant association. More specifically, among the 1,199 children in the KOMCHS [69], neither maternal intake of total or specific n-3 and n-6 PUFA from food were associated with children’s risk of the hyperactivity-inattention problems. In a randomized controlled trial among 797 children in Mexico [70], maternal DHA supplementation of 400 mg/day from mid-pregnancy to delivery was not associated with clinical risk of ADHD measured by the Conner’s Kiddie Continuous Performance Test (K-CPT) core indicating (>70th percentile). Of note, the ability of the K-CPT to accurately identify children at risk for ADHD has been questioned [79].

Two studies examined maternal seafood intake in relation to children’s risk of hyperactivity-inattention problems. Among 219 children in the UK [71], more frequent intake of oily fish during pregnancy was associated with lower risk of the hyperactivity-inattention problem, whereas intake of all types of fish was not. In contrast, among 8946 children in Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) study in the UK [72], seafood intake was not associated with ADHD risk. However, results for oily fish intake were not reported. In summary, studies on the association between maternal PUFA or seafood intake and children’s ADHD risk are inconsistent and provide little evidence for an association; differences in exposure assessments inhibits a clear interpretation of the findings. Future studies need to have a comprehensive assessment of maternal fish, seafood, and PUFA intake/status in relation to offspring ADHD risk.

3.2.3. Maternal Caffeine, Coffee, and Tea Intake and Offspring ADHD Risk

Three cohort studies, including 3485 children in Brazil [74], 3439 children in The Netherlands [75], and 1199 children in Japan [73], consistently found no association between maternal caffeine intake during pregnancy and hyperactivity-inattention problem in children. Across the three studies, the cutoff for the highest intake category was 300–384 mg/day, which is equivalent to three to four and a half cups of coffee/day (a cup coffee is defined as 8 oz). In the meta-analysis pooling all three studies, the overall effect estimate comparing the highest to the lowest category of caffeine intake was null (OR = 0.91, 95% CI: 0.66, 1.27; I2 = 0.0%, p for I2 = 0.84).

On the other hand, two large prospective cohort studies [76,77] found suggestive evidence that extremely high levels of coffee intake in early pregnancy were associated with an increased risk of ADHD. Among 47,491 children in the DNBC [76], ≥8 cups/day of coffee in early pregnancy (OR = 1.47, 95% CI: 1.18, 1.83), but not late pregnancy (OR = 1.21, 95% CI: 0.95, 1.55), was associated with a significantly increased risk of hyperactivity inattention problems. Among 24,068 children in the Aarhus Birth Cohort in Denmark [77], ≥10 cups/day of coffee in early pregnancy was also associated with a substantial but non-significant increase in the risk for hyperkinetic disorders and ADHD diagnosis (OR = 2.3, 95% CI: 0.9, 5.9). Less coffee intake (<8 cups/day in the DNBC and <10 cups/day in the Aarhus Birth Cohort) was not associated with ADHD risk in either study. Of note, only about 3% of women had extremely high intake levels in both studies [76,77], and they appeared to be highly selective group, characterized by lower social class, much higher rate of cigarette smoking, and higher rate of hyperactivity themselves [76]. While the two studies adjusted for selected socioeconomic, lifestyle and psychological characteristic of the women [76,77], residual confounding from unmeasured variables cannot be ruled out. On the other hand, it is possible that only extreme levels of caffeine consumption affect fetal neurodevelopment [20]. The extreme levels of coffee intake were not captured in the studies examining caffeine intake. Taken together, these studies suggest a null association between moderate coffee intake and offspring ADHD risk. Further evaluation of extremely high levels of maternal coffee intake and ADHD risk is needed.

3.2.4. Maternal Dietary Patterns and Offspring ADHD Risk

Two cohort studies [56,78] suggested an association between poor dietary quality during pregnancy and increased risk of ADHD or ADHD symptoms in children. Among 1242 children in the EDEN mother-child cohort in France [56], the lowest quartile of “healthy dietary patterns” (i.e., high intake in fruit, vegetables, fish, and whole grain cereals) and the highest quartile of “western dietary pattern” (i.e., high intake in processed and snacking foods) were both associated with increased risk of hyperactivity-inattention trajectory between age three and eight years. In the ALSPAC [56], an “unhealthy dietary pattern” (i.e., high fat and sugar) score was positively associated with ADHD symptoms among 83 youths with early-onset persistent conduct problems, but not associated with ADHD symptoms among the 81 youths with low conduct problems; the association among youths with early-onset persistent conduct problems was mediated by higher levels of IGF2 DNA methylation at birth. Of note, IGF2 gene has important roles in regulating placental and fetal growth; genetic and epigenetic changes in the IGF2 gene and changes in IGF2 hormonal levels has been linked to altered development in the cerebellum and hippocampus, both of which are relevant to ADHD [56]. The significant association between maternal dietary quality and children’s ADHD risk should be further evaluated.

4. Methodological Issues and Future Directions

Two major methodological concerns among studies of maternal nutrition and offspring neurodevelopmental disorders merit further discussion. The first is potential measurement error in the exposure assessment. Studies that comprehensively characterized nutrients from both food and supplements are limited. This is relevant as the effect of the supplementation may depend on baseline nutrient sufficiency status before supplementation, as well as the supplementation dose. Similarly, the effects of a nutrient from food may be overwhelmed by supplementation. Moreover, most studies examined maternal nutritional exposures using questionnaires, including food frequency questionnaires, which are prone to recall bias. To address these concerns, future studies need to prospectively quantify nutrient intakes from both foods and dietary supplements, which may help to establish potential dose-response relations and sufficient dose to prevent offspring neurodevelopmental disorders. Future studies should also consider quantifying nutrient status using biomarkers, which complement dietary information from questionnaires and provide a source of validation.

A second methodological concern with regard to existing studies is potential bias due to residual confounding. Many maternal demographic, lifestyle, and psychosocial factors that contribute to poorer maternal nutritional status may also contribute to the risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in children [4,80]. Smaller studies frequently lack the power to adjust for a comprehensive list of potential confounders. Even in large studies where such adjustments were made, residual confounding from unknown risk factors are still possible, and a causal link cannot be established. Alternative study designs may help to ameliorate this concern and strengthen the evidence. For example, variants in MTHFR gene encoding methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase affect vulnerability to low folate intake [55]; variants in FADS gene encoding fatty acid desaturase are determinants of long change PUFA status [81]. These genetic variants have been found to modify the association between maternal intake of respective nutrients and offspring neurodevelopmental outcomes [15,44]. Futures studies may use these variants to implement Mendelian randomization in observational studies to further evaluate a potential causal effect of nutrients on offspring outcomes.

Besides these major methodological concerns, several others may merit consideration in designing future studies. First, the effect of a nutrient on neurodevelopmental disorders may vary by fetal developmental period, reflecting the underlying developmental processes affected. Many existing studies did not investigate the timing of the exposure explicitly. Future studies should have explicit hypotheses about the window of sensitivity, and use it inform study design and implementation and the interpretation of results. Longitudinal assessment of the exposures throughout relevant periods would be particularly suitable to identify the most relevant window of sensitivity to the nutrient. Knowledge of the sensitive window of exposure is essential for establishing evidence and designing interventions. Second, epigenetic modification is postulated to be major mechanism by which early life nutrition contributes to risk of health and disease later in life [82], and maternal intake of nutrients such as folate and DHA has been linked to differential DNA methylation patterns [8]. Two studies have reported promising findings where maternal diet has been simultaneously linked to altered methylation of specific genes and neurodevelopmental disorders [52,56]. More studies incorporating epigenetic data are needed to better understand the mechanism.

5. Conclusions

Maternal nutrition is a potentially modifiable factor important for fetal neurodevelopment. In the past decade, a body of research emerged examining the impact of maternal nutritional status and offspring developmental disorders. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive and systematic review of maternal nutrition during the preconception and perinatal period and offspring risk of neurodevelopmental disorders. This review included studies on maternal intake (or status) at multiple levels: nutrients (i.e., vitamins, minerals, PUFA, multivitamins), food (i.e., fish), and dietary patterns in relation to children’s risk of ASD and ADHD. Findings from the review supported an inverse association between maternal folic acid or multivitamin intake and children’s risk of ASD, although large heterogeneity existed across studies. Data on associations of other dietary factors and ASD, ADHD and related outcomes are inconclusive and warrant future investigation. Future studies that comprehensively quantify maternal nutrient intake from both food and supplements and integrate more objective measures of biomarkers reflecting intake and metabolism are warranted. In addition, incorporating genetic variants related to nutrient metabolism shall enable Mendelian randomization analyses to inform causal inferences and a better understanding of gene-diet interactions in relation to neurodevelopmental disorders. Understanding the sensitive window of exposure and gene-diet interactions may help inform precise intervention and prevention.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/11/7/1628/s1, Table S1: Search strategy and history in PubMed and Embase; Figure S1: Adjusted relative risk (RR) of offspring risk of autism spectrum disorder associated with maternal intake of multivitamin or prenatal vitamin and supplement with folic acid only formulation during pregnancy.

Author Contributions

C.Z., M.L. and S.N.H. conceptualized the study; M.L., S.N.H. and E.F. designed the study; M.L., E.F. and A.S.A. contributed to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data; M.L. wrote the first draft of the manuscript; all authors substantially revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research and the publication cost were supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

References

- King, J.C. A summary of pathways or mechanisms linking preconception maternal nutrition with birth outcomes. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 1437s–1444s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephenson, J.; Heslehurst, N.; Hall, J.; Schoenaker, D.; Hutchinson, J.; Cade, J.E.; Poston, L.; Barrett, G.; Crozier, S.R.; Barker, M.; et al. Before the beginning: Nutrition and lifestyle in the preconception period and its importance for future health. Lancet 2018, 391, 1830–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tau, G.Z.; Peterson, B.S. Normal development of brain circuits. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010, 35, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyall, K.; Schmidt, R.J.; Hertz-Picciotto, I. Maternal lifestyle and environmental risk factors for autism spectrum disorders. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linnet, K.M.; Dalsgaard, S.; Obel, C.; Wisborg, K.; Henriksen, T.B.; Rodriguez, A.; Kotimaa, A.; Moilanen, I.; Thomsen, P.H.; Olsen, J.; et al. Maternal lifestyle factors in pregnancy risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and associated behaviors: review of the current evidence. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 1028–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prado, E.L.; Dewey, K.G. Nutrition and brain development in early life. Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bale, T.L.; Baram, T.Z.; Brown, A.S.; Goldstein, J.M.; Insel, T.R.; McCarthy, M.M.; Nemeroff, C.B.; Reyes, T.M.; Simerly, R.B.; Susser, E.S.; et al. Early life programming and neurodevelopmental disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 68, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.S. Impact of maternal diet on the epigenome during in utero life and the developmental programming of diseases in childhood and adulthood. Nutrients 2015, 7, 9492–9507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steegers-Theunissen, R.P.; Obermann-Borst, S.A.; Kremer, D.; Lindemans, J.; Siebel, C.; Steegers, E.A.; Slagboom, P.E.; Heijmans, B.T. Periconceptional maternal folic acid use of 400 microg per day is related to increased methylation of the IGF2 gene in the very young child. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craciunescu, C.N.; Brown, E.C.; Mar, M.H.; Albright, C.D.; Nadeau, M.R.; Zeisel, S.H. Folic acid deficiency during late gestation decreases progenitor cell proliferation and increases apoptosis in fetal mouse brain. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadavji, N.M.; Deng, L.; Malysheva, O.; Caudill, M.A.; Rozen, R. MTHFR deficiency or reduced intake of folate or choline in pregnant mice results in impaired short-term memory and increased apoptosis in the hippocampus of wild-type offspring. Neuroscience 2015, 300, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitkin, R.M. Folate and neural tube defects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 285s–288s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yehuda, S.; Rabinovitz, S.; Mostofsky, D.I. Essential fatty acids are mediators of brain biochemistry and cognitive functions. J. Neurosci. Res. 1999, 56, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M. Tissue levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids during early human development. J. Pediatrics 1992, 120, S129–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauritzen, L.; Brambilla, P.; Mazzocchi, A.; Harsløf, L.; Ciappolino, V.; Agostoni, C. DHA effects in brain development and function. Nutrients 2016, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, J.C.; Ames, B.N. Is docosahexaenoic acid, an n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid, required for development of normal brain function? An overview of evidence from cognitive and behavioral tests in humans and animals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, S.E. Docosahexaenoic acid and arachidonic acid in infant development. Semin. Neonatol. 2001, 6, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fretham, S.J.; Carlson, E.S.; Georgieff, M.K. The role of iron in learning and memory. Adv. Nutr. 2011, 2, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeaff, S.A. Iodine deficiency in pregnancy: The effect on neurodevelopment in the child. Nutrients 2011, 3, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porciúncula, L.O.; Sallaberry, C.; Mioranzza, S.; Botton, P.H.S.; Rosemberg, D.B. The Janus face of caffeine. Neurochem. Int. 2013, 63, 594–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougma, K.; Aboud, F.E.; Harding, K.B.; Marquis, G.S. Iodine and mental development of children 5 years old and under: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2013, 5, 1384–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borge, T.C.; Aase, H.; Brantsaeter, A.L.; Biele, G. The importance of maternal diet quality during pregnancy on cognitive and behavioural outcomes in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, R.; Hunter, S.K.; Hoffman, M.C. Prenatal primary prevention of mental illness by micronutrient supplements in pregnancy. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starling, P.; Charlton, K.; McMahon, A.T.; Lucas, C. Fish intake during pregnancy and foetal neurodevelopment—A systematic review of the evidence. Nutrients 2015, 7, 2001–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, J.F.; Smithers, L.G.; Makrides, M. The effect of maternal omega-3 (n-3) LCPUFA supplementation during pregnancy on early childhood cognitive and visual development: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Li, K.; Zhao, D.; Li, L. The association between maternal use of folic acid supplements during pregnancy and risk of autism spectrum disorders in children: A meta-analysis. Mol. Autism 2017, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVilbiss, E.A.; Gardner, R.M.; Newschaffer, C.J.; Lee, B.K. Maternal folate status as a risk factor for autism spectrum disorders: A review of existing evidence. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, S.A.; Altman, J.; Russo, R.J.; Zhang, X. Timetables of neurogenesis in the human brain based on experimentally determined patterns in the rat. Neurotoxicology 1993, 14, 83–144. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data & Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html (accessed on 5 June 2019).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data & Statistics about ADHD. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/data.html (accessed on 5 June 2019).

- Tierney, J.F.; Stewart, L.A.; Ghersi, D.; Burdett, S.; Sydes, M.R. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials 2007, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp LP. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. (computer program); StataCorp LP: College Station, TX, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, R.J.; Iosif, A.M.; Angel, E.G.; Ozonoff, S. Association of maternal prenatal vitamin use with risk for autism spectrum disorder recurrence in young siblings. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, S.Z.; Kodesh, A.; Viktorin, A.; Smith, L.; Uher, R.; Reichenberg, A.; Sandin, S. Association of maternal use of folic acid and multivitamin supplements in the periods before and during pregnancy with the risk of autism spectrum disorder in offspring. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.M.; Shen, Y.D.; Li, Y.J.; Xun, G.L.; Liu, H.; Wu, R.R.; Ou, J.J. Maternal dietary patterns, supplements intake and autism spectrum disorders: A preliminary case-control study. Medicine 2018, 97, e13902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghavan, R.; Riley, A.W.; Volk, H.; Caruso, D.; Hironaka, L.; Sices, L.; Hong, X.; Wang, G.; Ji, Y.; Brucato, M.; et al. Maternal multivitamin intake, plasma folate and vitamin B12 levels and autism spectrum disorder risk in offspring. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2018, 32, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strom, M.G.C.; Lyall, K.; Ascherio, A.; Olsen, S.F. Research letter: Folic acid supplementation and intake of folate in pregnancy in relation to offspring risk of autism spectrum disorder. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVilbiss, E.A.; Magnusson, C.; Gardner, R.M.; Rai, D.; Newschaffer, C.J.; Lyall, K.; Dalman, C.; Lee, B.K. Antenatal nutritional supplementation and autism spectrum disorders in the Stockholm youth cohort: Population based cohort study. BMJ 2017, 359, j4273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virk, J.; Liew, Z.; Olsen, J.; Nohr, E.A.; Catov, J.M.; Ritz, B. Preconceptional and prenatal supplementary folic acid and multivitamin intake and autism spectrum disorders. Autism 2016, 20, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, J.M.; Froehlich, T.; Kalkbrenner, A.; Pfeiffer, C.M.; Fazili, Z.; Yolton, K.; Lanphear, B.P. Brief report: Are autistic-behaviors in children related to prenatal vitamin use and maternal whole blood folate concentrations? J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 2602–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, R.M.; Surén, P.; Gunnes, N.; Alsaker, E.R.; Bresnahan, M.; Hirtz, D.; Roth, C. Analysis of self-selection bias in a population-based cohort study of autism spectrum disorders. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2013, 27, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suren, P.; Roth, C.; Bresnahan, M.; Haugen, M.; Hornig, M.; Hirtz, D.; Lie, K.K.; Lipkin, W.I.; Magnus, P.; Reichborn-Kjennerud, T.; et al. Association between maternal use of folic acid supplements and risk of autism spectrum disorders in children. Jama 2013, 309, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSoto, M.C.; Hitlan, R.T. Synthetic folic acid supplementation during pregnancy may increase the risk of developing autism. J. Pediatric Biochem. 2012, 2, 251–261. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, R.J.; Tancredi, D.J.; Ozonoff, S.; Hansen, R.L.; Hartiala, J.; Allayee, H.; Schmidt, L.C.; Tassone, F.; Hertz-Picciotto, I. Maternal periconceptional folic acid intake and risk of autism spectrum disorders and developmental delay in the CHARGE (Childhood Autism Risks from Genetics and Environment) case-control study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, R.J.; Hansen, R.L.; Hartiala, J.; Allayee, H.; Schmidt, L.C.; Tancredi, D.J.; Tassone, F.; Hertz-Picciotto, I. Prenatal vitamins, one-carbon metabolism gene variants, and risk for autism. Epidemiology 2011, 22, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenweg-de Graaff, J.; Ghassabian, A.; Jaddoe, V.W.; Tiemeier, H.; Roza, S.J. Folate concentrations during pregnancy and autistic traits in the offspring. The Generation R Study. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 431–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, R.J.; Tancredi, D.J.; Krakowiak, P.; Hansen, R.L.; Ozonoff, S. Maternal intake of supplemental iron and risk of autism spectrum disorder. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 180, 890–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyall, K.; Munger, K.L.; O’Reilly, E.J.; Santangelo, S.L.; Ascherio, A. Maternal dietary fat intake in association with autism spectrum disorders. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 178, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenweg-De Graaff, J.; Tiemeier, H.; Ghassabian, A.; Rijlaarsdam, J.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Verhulst, F.C.; Roza, S.J. Maternal fatty acid status during pregnancy and child autistic traits: The Generation R Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 183, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Cui, S.S.; Han, Y.; Dai, W.; Su, Y.Y.; Zhang, X. Does periconceptional fish consumption by parents affect the incidence of autism spectrum disorder and intelligence deficiency? A Case-control study in Tianjin, China. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2016, 29, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julvez, J.; Mendez, M.; Fernandez-Barres, S.; Romaguera, D.; Vioque, J.; Llop, S.; Ibarluzea, J.; Guxens, M.; Avella-Garcia, C.; Tardon, A.; et al. Maternal consumption of seafood in pregnancy and child neuropsychological development: A longitudinal study based on a population with high consumption levels. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 183, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, J.S.; Mendez, M.; Maguire, R.L.; Gonzalez-Nahm, S.; Huang, Z.; Daniels, J.; Murphy, S.K.; Fuemmeler, B.F.; Wright, F.A.; Hoyo, C. Periconceptional maternal mediterranean diet is associated with favorable offspring behaviors and altered CpG methylation of imprinted genes. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.J.; Ozonoff, S.; Hansen, R.; Hartiala, J.; Allayee, H.; Schmidt, L.; Tassone, F.; Hertz-Picciotto, I. (old record 6424) Maternal periconceptional folic acid intake and risk for developmental delay and autism spectrum disorder: A case-control study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 175, S126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, Y.-M.; Ou, J.-J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, J.-P.; Tang, S.-Y. Association between maternal obesity and autism spectrum disorder in offspring: A meta-analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueland, P.M.; Hustad, S.; Schneede, J.; Refsum, H.; Vollset, S.E. Biological and clinical implications of the MTHFR C677T polymorphism. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2001, 22, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijlaarsdam, J.; Cecil, C.A.; Walton, E.; Mesirow, M.S.; Relton, C.L.; Gaunt, T.R.; McArdle, W.; Barker, E.D. Prenatal unhealthy diet, insulin-like growth factor 2 gene (IGF2) methylation, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in youth with early-onset conduct problems. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pidsley, R.; Dempster, E.; Troakes, C.; Al-Sarraj, S.; Mill, J. Epigenetic and genetic variation at the IGF2/H19 imprinting control region on 11p15. 5 is associated with cerebellum weight. Epigenetics 2012, 7, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office of Dietary Supplements; National Library of Medicine. Dietary Supplement Label Database. Available online: https://www.dsld.nlm.nih.gov/dsld/index.jsp (accessed on 7 February 2019).

- Stamm, R.; Houghton, L. Nutrient intake values for folate during pregnancy and lactation vary widely around the world. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3920–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcken, B.; Bamforth, F.; Li, Z.; Zhu, H.; Ritvanen, A.; Redlund, M.; Stoll, C.; Alembik, Y.; Dott, B.; Czeizel, A. Geographical and ethnic variation of the 677C> T allele of 5, 10 methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR): Findings from over 7000 newborns from 16 areas world wide. J. Med Genet. 2003, 40, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, G.; Ecker, J. The opposing effects of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids. Prog. Lipid Res. 2008, 47, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, E.; Wall, R.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. Health implications of high dietary omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids. J. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 2012, 539426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, S.W.; Waldie, K.E.; Peterson, E.R.; Underwood, L.; Morton, S.M.B. Antenatal and postnatal determinants of behavioural difficulties in early childhood: Evidence from growing up in New Zealand. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2019, 50, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, Y.T.K.; Okubo, H.; Sasaki, S.; Arakawa, M. Maternal B vitamin intake during pregnancy and childhood behavioral problems in Japan: The Kyushu Okinawa maternal and child health study. Nutr. Neurosci. 2018, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virk, J.; Liew, Z.; Olsen, J.; Nohr, E.A.; Catov, J.M.; Ritz, B. Pre-conceptual and prenatal supplementary folic acid and multivitamin intake, behavioral problems, and hyperkinetic disorders: A study based on the Danish National Birth Cohort (DNBC). Nutr. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julvez, J.; Fortuny, J.; Mendez, M.; Torrent, M.; Ribas-Fitó, N.; Sunyer, J. Maternal use of folic acid supplements during pregnancy and four-year-old neurodevelopment in a population-based birth cohort. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2009, 23, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlotz, W.; Jones, A.; Phillips, D.I.; Gale, C.R.; Robinson, S.M.; Godfrey, K.M. Lower maternal folate status in early pregnancy is associated with childhood hyperactivity and peer problems in offspring. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abel, M.H.; Ystrom, E.; Caspersen, I.H.; Meltzer, H.M.; Aase, H.; Torheim, L.E.; Askeland, R.B.; Reichborn-Kjennerud, T.; Brantsaeter, A.L. Maternal iodine intake and offspring attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Results from a large prospective cohort study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyake, Y.T.K.; Okubo, H.; Sasaki, S.; Arakawa, M. Maternal fat intake during pregnancy and behavioral problems in 5-y-old Japanese children. Nutrition 2018, 50, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, U.; Gonzalez-Casanova, I.; Schnaas, L.; DiGirolamo, A.; Quezada, A.D.; Pallo, B.C.; Hao, W.; Neufeld, L.M.; Rivera, J.A.; Stein, A.D.; et al. Prenatal supplementation with DHA improves attention at 5 years of age: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, C.R.; Robinson, S.M.; Godfrey, K.M.; Law, C.M.; Schlotz, W.; O’Callaghan, F.J. Oily fish intake during pregnancy—Association with lower hyperactivity but not with higher full-scale IQ in offspring. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2008, 49, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbeln, J.R.; Davis, J.M.; Steer, C.; Emmett, P.; Rogers, I.; Williams, C.; Golding, J. Maternal seafood consumption in pregnancy and neurodevelopmental outcomes in childhood (ALSPAC study): An observational cohort study. Lancet 2007, 369, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, Y.T.K.; Okubo, H.; Sasaki, S.; Arakawa, M. Maternal caffeine intake in pregnancy is inversely related to childhood peer problems in Japan: The Kyushu Okinawa maternal and child health study. Nutr. Neurosci. 2018, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Ponte, B.; Santos, I.S.; Tovo-Rodrigues, L.; Anselmi, L.; Munhoz, T.N.; Matijasevich, A. Caffeine consumption during pregnancy and ADHD at the age of 11 years: A birth cohort study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomans, E.M.; Hofland, L.; van der Stelt, O.; van der Wal, M.F.; Koot, H.M.; Van den Bergh, B.R.; Vrijkotte, T.G. Caffeine intake during pregnancy and risk of problem behavior in 5- to 6-year-old children. Pediatrics 2012, 130, e305–e313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hvolgaard Mikkelsen, S.; Obel, C.; Olsen, J.; Niclasen, J.; Bech, B.H. Maternal caffeine consumption during pregnancy and behavioral disorders in 11-year-old offspring: A Danish National Birth Cohort study. J. Pediatrics 2017, 189, 120–127.e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linnet, K.M.; Wisborg, K.; Secher, N.J.; Thomsen, P.H.; Obel, C.; Dalsgaard, S.; Henriksen, T.B. Coffee consumption during pregnancy and the risk of hyperkinetic disorder and ADHD: A prospective cohort study. Acta Paediatr. 2009, 98, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galera, C.; Heude, B.; Forhan, A.; Bernard, J.Y.; Peyre, H.; Van der Waerden, J.; Pryor, L.; Bouvard, M.P.; Melchior, M.; Lioret, S.; et al. Prenatal diet and children’s trajectories of hyperactivity-inattention and conduct problems from 3 to 8 years: The EDEN mother-child cohort. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 59, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGee, R.A.; Clark, S.E.; Symons, D.K. Does the conners’ continuous performance test aid in ADHD diagnosis? J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2000, 28, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thapar, A.; Cooper, M.; Jefferies, R.; Stergiakouli, E. What causes attention deficit hyperactivity disorder? Arch. Dis. Child. 2012, 97, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, R.A.; Pani, V.; Chilton, F.H. Genetic Variants in the FADS gene: Implications for dietary recommendations for fatty acid intake. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2014, 3, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symonds, M.E.; Sebert, S.P.; Hyatt, M.A.; Budge, H. Nutritional programming of the metabolic syndrome. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2009, 5, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).