Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Extremely Lightweight Model: WSNet achieves state–of–the–art efficiency with only 0.054 M parameters and 1.050 G FLOPs, making it the lightest model to date in the field of Infrared Small Target Detection (IRSTD).

- Wide and Shallow Architecture: Contrary to conventional deep networks, WSNet adopts a wide and shallow design, which is more suitable for infrared images that lack rich semantic information. Excessive depth leads to performance degradation in IRSTD.

- Superior Performance–Speed Trade–off: WSNet achieves competitive detection accuracy (e.g., highest IoU on SIRST, and best Pd on NUDT–SIRST) while offering the fastest inference speed (up to 146 FPS on GPU, 30 FPS on CPU).

What is the implication of the main finding?

- Practical Deployment in Resource–Limited Environments: WSNet’s lightweight design and real–time CPU compatibility enable its deployment in embedded systems, drones, and portable infrared devices, where computational resources are limited but low–latency detection is critical.

- Paradigm Shift in IRSTD Architecture Design: The success of a wide and shallow network challenges the prevailing “deeper is better” assumption in deep learning for IRSTD, encouraging the community to reconsider architecture tailoring based on domain–specific characteristics.

Abstract

Designing lightweight yet competitive models remains a challenging problem across the computer vision community—Infrared Small Target Detection (IRSTD) is no exception. To address this challenge, we propose WSNet, a novel model that achieves competitive performance while significantly reducing computational cost and memory consumption, without relying on deeper architectures or complex fusion mechanisms. The core innovation of WSNet lies in its extremely simple yet highly efficient network architecture, tailored to the specific demands of the IRSTD task. To the best of our knowledge, WSNet is the lightest existing model in the IRSTD field, containing only 0.054 M parameters—hundreds of times fewer than state–of–the–art alternatives—and requiring merely 1.050 G FLOPs. Extensive experiments on multiple benchmark datasets show that WSNet not only performs on par with leading methods but also delivers substantially faster inference speeds, making it highly suitable for real–time applications on embedded and resource–constrained devices.

1. Introduction

Infrared imaging offers unique advantages over radar and visible light imaging, such as strong anti–interference capabilities, smoke penetrability, and adaptability to both day and night scenes [1,2]. As a critical downstream task, Infrared Small Target Detection (IRSTD) has become a key focus in various infrared applications. IRSTD plays an essential role in diverse fields, including traffic management, maritime rescue, and military operations [3,4,5]. However, due to long–distance imaging and significant interference from complex backgrounds, targets in infrared images are often very small and dim, typically covering less than pixels [6]. Furthermore, thermal imagers capture only thermal radiation, lacking sufficient hue and texture information needed for effective feature extraction, making Infrared Small Target Detection especially challenging.

Traditional methods, such as those cited in [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17], have made significant historical contributions to the field. However, they are fundamentally limited by their reliance on handcrafted features and conventional image processing techniques, which inherently lack the adaptive generalization capacity needed for robust performance in complex real–world environments.

In recent years, deep learning–based methods have achieved notable progress in Infrared Small Target Detection (IRSTD). Unlike traditional approaches, deep learning models can automatically extract target–related features and contextual cues from the background, thereby significantly improving generalization. Representative works include those cited in [6,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. However, as shown in Figure 1, these models often require substantial computational and memory resources, limiting their practicality for real–world deployment. This inefficiency primarily stems from the adoption of very deep network architectures inherited from conventional vision tasks, which overlook a key characteristic of IRSTD: infrared targets and their surroundings typically contain limited semantic information, as illustrated in Figure 2. This property reduces the necessity for deep hierarchies and suggests that more efficient designs are possible without sacrificing performance.

Figure 1.

The trend of Params and FLOPs in mainstream deep learning–based methods for IRSTD. Although models such as MSHNet and later approaches have achieved significant reductions in both parameters and computational cost, they still typically contain several million parameters and require several GFLOPs of computation. This level of complexity makes them unrealistic for deployment on embedded and resource–constrained hardware.

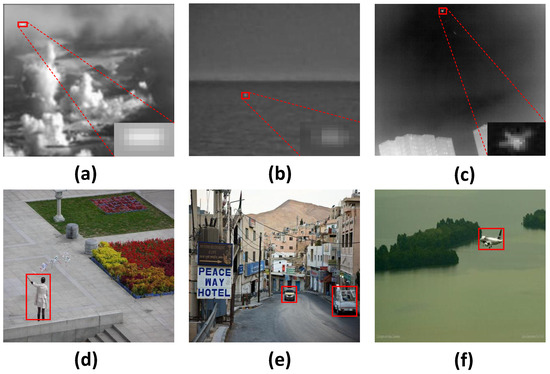

Figure 2.

Comparison between infrared images and conventional images. Compared to conventional images, targets and their surrounding environments in infrared images generally lack rich semantic information due to the absence of hue and detailed texture [31]. (a–c): Infrared images; (d–f): conventional images. The object inside red box is our detection target.

Motivated by this observation, we propose WSNet—a lightweight network that diverges from common architectural paradigms in IRSTD, such as U-Nets, ResNets, and Vision Transformers. Instead of pursuing greater depth, our design emphasizes a shallow yet wide structure to enhance representational capacity efficiently. Moreover, we introduce a streamlined building block that replaces conventional concatenation and complex fusion modules with simple yet effective summation and multiplication operations. This design offers a new perspective for efficient model development in IRSTD and may inspire further research into lightweight detection architectures.

The contributions of this study are as follows:

- (1)

- We design an extremely simple and efficient architecture named WSNet, which contains only 0.054 M parameters and requires 1.050 G FLOPs. It represents the most lightweight model in the field of IRSTD and achieves the fastest inference speed to date. The code is available at https://github.com/CPaul33/WSNet on 15 January 2025.

- (2)

- To fit the scarcity of hierarchical semantic content in IRSTD tasks, we introduce a Width Extension Module (WEM) that enhances feature representation by expanding the network’s width. Furthermore, building upon the CBAM module [32], we propose a customized Channel–Spatial Hybrid Attention (CSHA) mechanism. This is the first work to incorporate Lp Pooling into such a structure, which effectively smooths outliers while preserving the overall trend of features.

- (3)

- Extensive experiments on multiple benchmark datasets—SIRST [19], NUDT–SIRST [20], and IRSTD–1K [21]—show that WSNet achieves performance comparable to state–of–the–art models, while delivering the fastest inference speed, several times faster than current SOTA approaches. Furthermore, experiments demonstrate that WSNet can be directly deployed on resource–constrained devices such as CPUs while still maintaining real–time detection capability, making it highly suitable for practical real–time applications and large–scale deployment in real–world IRSTD scenarios.

2. Related Work

2.1. Infrared Small Target Detection

The study of IRSTD has evolved significantly over several decades. In its early stages, traditional approaches predominantly utilized image processing techniques and handcrafted feature engineering. These methodologies can be systematically classified into three principal categories: background suppression–based methods [7,8,9], human visual system–inspired approaches [10,11,12], and optimization–driven techniques [13,14,15,16,17]. Although these conventional methods made substantial historical contributions to the field, they exhibit notable limitations in handling complex background interference and adapting to diverse target morphologies and scales [21]. These constraints primarily stem from their inherent reliance on manual feature engineering and conventional image processing, which fundamentally lack the adaptive generalization capabilities required for robust performance in complex, real–world operational environments.

With the success of deep learning across various domains such as computer vision, natural language processing, and speech recognition, researchers have increasingly turned to deep learning techniques for IRSTD [33]. Notable deep learning–based methods include [6,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. With the advent of deep learning, considerable progress has been achieved in Infrared Small Target Detection (IRSTD) in recent years. In contrast to traditional approaches, deep learning–based methods excel at autonomously extracting target features and contextual information from complex backgrounds, substantially enhancing model generalization. Among the notable contributions, Wang et al. [18] proposed the MDvsFA model to balance miss detection and false alarm rates, while Dai et al. [19] developed an Asymmetric Contextual Modulation (ACM) network to capture multi–level contextual features. Zhang et al. [21] introduced ISNet, incorporating a Taylor Finite Difference–inspired edge block and a Two–Orientation Attention Aggregation mechanism to retain target structure. Li et al. [20] designed a Dense Nested Attention Network (DNA–Net) to mitigate target information loss during pooling operations. Further architectural innovations include UIU–Net by Wu et al. [6], which employs nested U–Net connections for enhanced feature aggregation. More recently, Vision Transformers have also been leveraged for IRSTD—for instance, Wu et al. [22] adopted a ViT–based framework to integrate multi–scale features. Other advanced strategies include AGPCNet [23], which augments contextual perception in cluttered environments, and MSHNet by Liu et al. [24], which introduces a scale– and location–sensitive loss to improve detection performance. Additionally, Zhang et al. [26,27] incorporate frequency–domain insights from earlier studies into model design. Yuan et al. [28] proposed SCTransNet, utilizing a spatial–embedded channel–cross block for hierarchical multi–level feature fusion and decoding guidance. BGM [29] enhances Infrared Small Target Detection by forcing the network to focus exclusively on the targets through random masking/forgetting of irrelevant background information during training, thereby improving detection performance without increasing inference complexity. HFMNet [30] advances Infrared Small Target Detection by integrating cross–pooling, hybrid local–global feature mining, and focused fusion in a lightweight framework.

Although this deep learning–based methods have improved detection accuracy, they often introduce high computational and memory overhead. This is largely because they inherit complex network designs from general–purpose vision models without adapting to the inherently low semantic information in infrared scenes, thereby limiting their practical applicability.

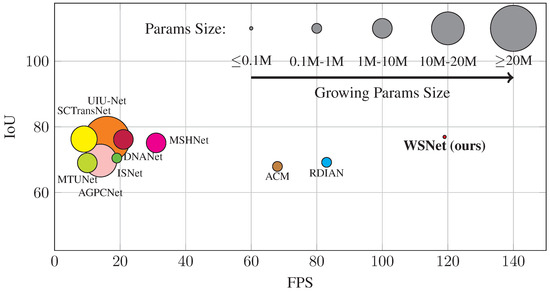

To overcome these challenges, we propose WSNet—a novel lightweight approach that not only achieves competitive performance on the IRSTD task but also drastically reduces computational and memory demands. As a result, WSNet delivers faster inference and offers an optimal balance between efficiency, accuracy, and resource consumption, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Trade–off among IoU, Params and FPS, tested on SIRST dataset. Our WSNet achieves the smallest model size and the fastest inference speed, while simultaneously maintaining a competitive IoU performance.

2.2. Lightweight Network

Currently, many researchers focus on improving performance in the IRSTD task by enhancing Intersection over Union (IoU), Probability of Detection (Pd), and reducing False Alarm Rate (Fa). However, these improvements are often achieved by stacking multiple feature fusion modules or modifying the network structure based on heavyweight baselines. While this can lead to marginal performance gains, it results in a sharp increase in computational resource usage and memory consumption, which hinders the realistic deployment of models.

Fortunately, there is a growing group of researchers dedicated to exploring lightweight network paradigms. Notable examples include [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43], all of which have achieved remarkable success in reducing the computational burden while maintaining performance. In the context of IRSTD, Zhao et al. [44] pioneered lightweight network design, while Wu et al. [45] introduced RepISD–Net, which significantly accelerates inference speed without sacrificing detection accuracy. Kou et al. [46] developed LW–IRSTNet, aiming for a balance between computational efficiency and detection performance.

Although these lightweight models have made significant progress in IRSTD, they still face challenges when high detection accuracy is required alongside low computational cost and memory usage. In contrast, our proposed WSNet features only 0.054 M parameters and 1.050 G FLOPs—substantially smaller than any existing IRSTD models. Despite its lightweight nature, WSNet can maintain the performance of some SOTA models across multiple datasets, offering a superior trade–off between efficiency and detection accuracy.

2.3. Width Extension Learning

The width and depth are two fundamental components in the design of a neural network architecture. Both play crucial roles in determining the network’s performance and should be carefully balanced. Depth governs the level of abstraction, enabling the network to learn hierarchical representations, while width influences the capacity to retain and process information during the forward pass [47].

In the pursuit of optimizing neural network architectures, Cheng et al. [48] introduced the wide and deep learning framework, which combines the benefits of both wide linear models and deep neural networks. Zagoruyko et al. [49] proposed Wide Residual Networks (WRNs), demonstrating that these architectures, with their wider structures, outperform their deeper and thinner counterparts. Szegedy et al. [50,51] developed the Inception architecture, achieving high–quality performance by striking a balance between network width and depth. Similarly, Hou et al. [52] utilized multiple convolution kernel sizes within a single layer to better capture contrasting features of small targets, while Sun et al. [53] introduced a multi–receptive–field feature extraction module (MRFE) to enhance the extraction of local features.

Building on these insights, we propose a custom Width Extension Module (WEM) designed to effectively capture a broader range of features from both the targets and their surrounding context.

2.4. Attention Mechanism

The attention mechanism is a powerful technique in machine learning and artificial intelligence, designed to enhance model performance by focusing on the most relevant information within the input data. It allows models to selectively prioritize different parts of the input by assigning varying levels of importance or weights to each element, thereby improving the accuracy and efficiency of processing.

In the domain of computer vision, numerous groundbreaking studies have leveraged attention mechanisms to advance model performance [32,54,55,56]. In the context of IRSTD, Li et al. [20] introduced a cascaded Channel and spatial attention Module (CSAM) to adaptively enhance multi–level feature representations. Wu et al. [6] proposed the Interactive–Cross Attention (IC–A) module, which encodes local context information between low–level details and high–level semantic features. Zhang et al. [21] designed the Two–Orientation Attention Aggregation (TOAA) block, which employs the attention mechanism to extract low–level information along both row and column directions. Additionally, Sun et al. [53] utilized a multi–directional guided attention mechanism to improve the representation of targets in low–level feature maps.

In this study, we refine the CBAM module [32] and propose a Channel–Spatial Hybrid Attention (CSHA) module. This is the first work to incorporate Lp Pooling into such a structure, which effectively smooths outliers while preserving the overall trend of features. The CSHA module combines both channel–wise and spatial attention to selectively emphasize relevant features, thereby improving the model’s ability to detect small infrared targets in challenging environments.

3. Methodology

3.1. Overall Architecture

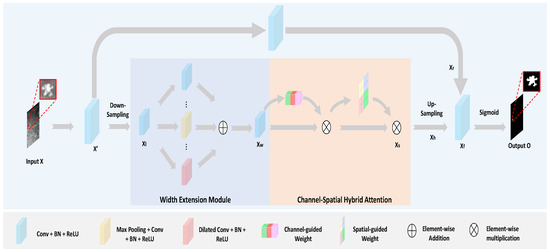

The overall architecture of WSNet is illustrated in Figure 4. The network processes infrared images as input, which are extracted to initial infrared feature maps through a convolutional layer. The architecture subsequently diverges into two parallel branches: The main branch sequentially performs: (1) down–sampling via a convolutional layer with stride 2, generating low–resolution feature maps ; (2) WEM to enhance feature representation across a broader spectrum; (3) CSHA to suppress irrelevant noise while emphasizing salient features; and (4) up–sampling through bilinear interpolation to reconstruct high–resolution feature maps . In parallel, the skip connection branch implements a convolutional layer to adjust the dimensionality of feature maps . To optimize computational efficiency, we employ an element–wise addition operation instead of complex fusion modules, effectively reducing both model parameters and FLOPs. The network culminates in a Fully Convolutional Network Head (FCN Head) [57] followed by a Sigmoid activation function, producing the final prediction output .

Figure 4.

The overall architecture of the proposed WSNet. It leverages a highly streamlined architecture, comprising only a few convolutional layers and the attention–guided mechanism, to deliver compelling model performance.

The process described above can be expressed mathematically as

where and denote element–wise addition and bilinear interpolation, respectively, and denotes the Sigmoid activation function.

3.2. Width Extension Module

Wider networks, with more neurons (or blocks) per layer, provide greater expressive power, enabling them to capture diverse features simultaneously [47].

In light of this, we design a custom Width Extension Module (WEM) to enhance the model’s feature representation capability through systematic network widening. The detailed structure of WEM is illustrated in Figure 5. The module integrates multiple computational pathways: the yellow pathway uses Max Pooling to highlight the most salient regions of the feature maps, which typically contain target–related information; the blue pathway utilizes convolutional layers with progressively increasing kernel sizes (3 × 3, 5 × 5, and 7 × 7) to enrich feature diversity—enabling the network to capture visual features at multiple scales within the same level, where the 3 × 3 kernel extracts local patterns, while the 5 × 5 and 7 × 7 kernels provide a wider range of patterns and spatial correlations; and the red pathway utilizes dilated convolutions with different dilation rates to capture contextual information—an aspect often under–represented in shallow networks. To reduce computational complexity, we incorporate 1 × 1 convolutional kernels in each branch to reduce the number of channels while preserving critical feature representations. We then use summation () rather than concatenation () to integrate the multi–scale features. This choice is motivated by two factors: first, the multi–scale features exhibit semantic similarity and have identical dimensions, making them suitable for direct fusion; second, summation is computationally more efficient than concatenation, as it does not increase the channel count or computational overhead—a conclusion supported by the ablation study in Section 4.5, Impact of the Design Choice of WEM. It is also worth noting that the multi–branch architecture tends to introduce extraneous noise (particularly due to the inclusion of Max Pooling), which can mislead subsequent layers and lead to higher false alarm (FA) rates. To mitigate this risk, we apply a 3 × 3 convolutional layer for feature refinement.

Figure 5.

The detailed structure of Width Extension Module (WEM). The WEM consists of multiple branches, each with a different receptive field (RF).

The following is the mathematical formula expression for this module:

where () denotes a convolutional layer, and represents a dilated convolutional layer with a dilation rate of either 3 or 4. The output of each Branch in WEM is denoted as , where indicates the number of branches in WEM. Note that in Equations (7) and (8), corresponds to the convolutional branches, while corresponds to the dilated convolutional branches.

Eventually, the final output of WEM can be attained by sequentially performing the operation and the Convolutional layer:

3.3. Channel–Spatial Hybrid Attention

The attention mechanism can significantly enhance detection performance by guiding the model to focus on regions with distinctive features, thereby reducing the chances of missing small targets. Additionally, by assigning lower weights to irrelevant regions, such as cluttered backgrounds or noisy areas, the attention mechanism effectively filters out unnecessary information, making it highly suitable for addressing the challenges of the IRSTD task.

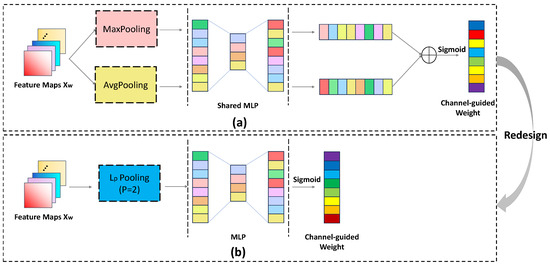

Inspired by this, we build up our Channel–Spatial Hybrid Attention (CSHA) module which has two sequential sub–modules: channel attention (CA) and Spatial Attention (SA).

The motivation behind CA lies in our belief that Max and Average Pooling used in conventional channel attention (e.g., SENet [55], and CBAM [32]) are suboptimal for IRSTD tasks, whereas Lp Pooling offers a better alternative. Specifically: (1) Max Pooling is sensitive to outliers (e.g., extremely high activation values), potentially amplifying noise; (2) Average Pooling tends to dilute salient features and lacks robustness to noise; (3) Lp Pooling (e.g., when p = 2) balances these issues by smoothing outliers while preserving overall feature trends—making it more suitable for the inherently noisy nature of infrared images, specially considering the purpose of channel attention is to better promote feature dimensionality reduction and inter–channel information aggregation. Our ablation studies (described in Section 4.5) confirm this: CSHA with Lp Pooling significantly outperforms SENet and CBAM in IRSTD performance.

The mathematical definition of the Pooling can be formulated as

where , n and y denote the input feature maps, and the total numbers of input feature maps and outcome of the Pooling, respectively. Furthermore, is a parameter used to control pooling behavior, and here, in this study, we set . Similar to conventional channel attention mechanisms, we compute Equation (10) over the spatial dimensions.

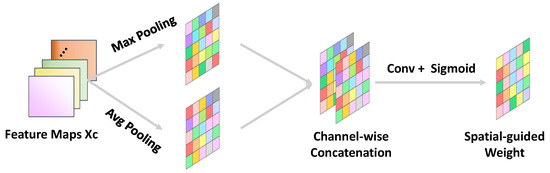

For SA, our goal is to guide the model to focus on regions with distinctive features—such as the salient parts of the target—while minimizing the introduction of noise. To achieve this, we employ both Max Pooling and Average Pooling: Max Pooling highlights the most prominent features, while Average Pooling provides a smooth representation by considering all values within the region.

The feature maps (here is , the output feature maps of WEM) as input are fed into the CSHA where it sequentially performs CA and SA to gain channel–guided weight and spatial–guided weight. In detail, Figure 6 and Figure 7 depict the computation process.

Figure 6.

The channel attention (CA) of our CSHA. (a) Channel attention of the typical CBAM [32]. (b) Redesigned channel attention of our CSHA.

Figure 7.

The spatial attention (SA) of our CSHA.

Mathematically, the whole process of CSHA can be, respectively, formulated as

where denotes a multi–layer perceptron with one hidden layer, and denotes the concatenation operation. and ⊗ denotes the Sigmoid function and the element–wise multiplication, respectively.

3.4. Fully Convolutional Network Head

After finishing the processes described in Section 3.2 and Section 3.3, we incorporate skip connection to integrate low–level and high–level features, and subsequently employ a Fully Convolutional Network (FCN) Head to generate the final output prediction .

The process can be formulated as

4. Experiment

4.1. Implementation Details

Evaluation Metrics. To provide a comprehensive evaluation, we use six performance metrics to assess the effectiveness of different methods: Intersection over Union (), Probability of Detection (), False Alarm Rate (), Frames Per Second (), Model Parameters (), and Floating–Point Operations (). Note that all these metrics refer to the average value. These metrics allow us to evaluate both the detection accuracy and the efficiency of the models, offering a well–rounded comparison across various approaches.

Dataset. To demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed method and evaluate its generalization capability, we conduct experiments using three well–known datasets: SIRST [19], NUDT–SIRST [20], and IRSTD–1K [21]. In line with previous works on these datasets [20,21], we adopt the same experimental settings. Specifically, we set the train–to–test ratio to 1 for both the SIRST and NUDT–SIRST datasets, and the train–to–test ratio of 4 for the IRSTD–1K dataset. This setup ensures consistency with prior research while allowing us to effectively assess the proposed method’s performance across different data distributions.

Experimental Settings. During training, all images were normalized and randomly cropped into patches of size 256 × 256, except for the IRSTD–1K dataset, where the patch size was set to 512 × 512. To augment the training data, we applied random flipping and rotation. The Soft–IoU loss function as well as the Adam optimizer with a batch size of 8 and an initial learning rate of 5 × 10−4 were used. The learning rate was reduced by a factor of 10 at the 200th and 300th epochs. Training was terminated after 500 epochs. A fixed segmentation threshold of 0.5 was applied during inference to filter out low–response regions and retain high–response areas for the final prediction. All models were implemented using the PyTorch 1.2.0 or higher framework and were both trained and tested on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU to ensure a consistent experimental environment. For fair comparison, in the comparison experiments, we used the same hyper–parameters and experimental settings as reported in the original papers of the competing methods. All models were retrained from scratch on the three datasets to ensure consistency.

4.2. Comparison to State–of–the–Art Methods

In this subsection, we compare our proposed WSNet model to nine traditional methods—Top–Hat [7], Max–Median [8], WSLCM [12], TLLCM [11], IPI [13], NRAM [14], RIPT [15], PSTNN [16], and MSLSTIPT [17]—as well as nine state–of–the–art (SOTA) deep learning–based methods, including ISNet [21], DNA–Net [20], UIU–Net [6], AGPCNet [23], MTU–Net [22], MSHNet [24], SCTransNet [28], BGM [29], and HFMNet [30].

Quantitative results are presented in Table 1. Our WSNet model achieves competitive performance across multiple evaluation metrics while exhibiting superior efficiency compared to all other state–of–the–art deep learning–based methods. Specifically, WSNet has the smallest number of parameters (only 0.054 M—more than ten times fewer than the previous best model) and the lowest computational cost (only 1.050 G FLOPs—an order of magnitude lower than the best–performing alternative). It also delivers the highest inference speed, reaching 119 , 146 , and 60 on the SIRST [19], NUDT–SIRST [20], and IRSTD–1K [21] datasets, respectively, which is several times faster than previous SOTA models. A key challenge was maintaining high detection performance while achieving such extreme efficiency. Remarkably, WSNet excels in this regard, attaining outstanding results across various detection metrics. For instance, it achieves the highest on SIRST and the best on NUDT–SIRST. Although minor decreases are observed in certain metrics, WSNet’s exceptional efficiency more than compensates for these slight shortcomings. Overall, WSNet represents the best trade–off currently available in terms of computational cost, inference speed, and accuracy for infrared small target detection.

Table 1.

Quantitative results of different SOTA methods. Results for the metrics of , , , , , and in different datasets are presented. ‘↓’ denotes lower is better and ‘↑’ denotes higher is better. The best results are in bold.

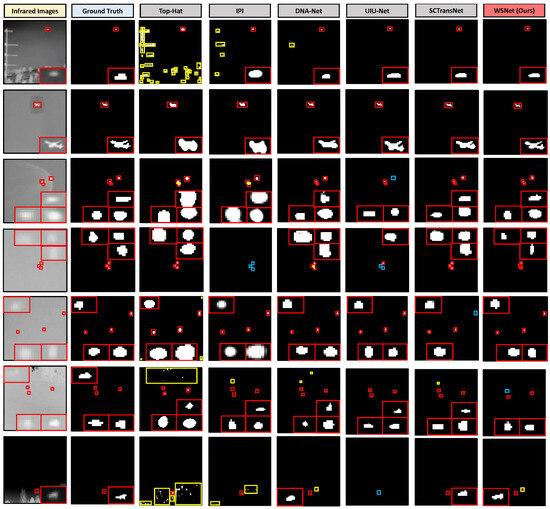

Qualitative results are shown in Figure 8. We present several representative detection examples to highlight the superiority of our proposed method. In the first row of images, traditional methods are clearly hindered by noise interference, leading to a substantial number of false alarms. In contrast, the second row demonstrates that WSNet achieves significantly better fine–grained segmentation. This improvement can be attributed to the enhanced feature representation capability provided by our WEM. Traditional methods and even some previous deep learning–based approaches struggle to effectively extract features from small–scale and low–contrast targets, often resulting in false alarms and missed detections. However, WSNet effectively addresses these challenges by sequently incorporating WEM and CSHA, achieving superior performance in terms of both fine–grained segmentation and overall detection accuracy. Even though some false alarms and missed detections may still occur in semantically rich scenarios, this effect can be alleviated by stacking additional convolutional layers in the initial stage of the network.

Figure 8.

Qualitative comparison with state–of–the–art methods on several infrared images. Correctly detected targets are marked in red, missed targets in blue, and false alarms in yellow. For better visualization, a close–up view of the target is shown in a larger box.

4.3. Comparison to Lightweight Methods

To further emphasize the superiority of our approach, we compare our WSNet model with several of the most lightweight methods in the IRSTD field, including ACM [19], ALCNet [58], ISNet [21], RDIAN [53], LW–IRSTNet [46], RepISD [45], and HFMNet–Tiny [30].

Quantitative results are presented in Table 2. Compared to other lightweight models in the IRSTD field, WSNet not only maintains superior efficiency—remaining the most lightweight approach—but also achieves the fastest inference speed. Specifically, WSNet runs approximately 1.5× faster in FPS than the previous fastest model. In terms of detection performance, WSNet also outperforms other lightweight models across most evaluation metrics, further solidifying its status as the optimal trade–off among computational cost, inference speed, and accuracy.

Table 2.

Quantitative results of various lightweight models. Results for the metrics of , , , , , and in different datasets are presented. The best results are in bold.

4.4. Deployment in Resource–Constrained Device

To evaluate the practical applicability of the proposed model in real–world scenarios, we conducted comparative experiments on a resource–constrained platform (Intel Xeon Platinum 8352V CPU). For simplicity, a set of representative models—including both state–of–the–art and lightweight approaches—were deployed on the same CPU platform. As shown in Table 3, WSNet achieves the highest inference speed among all models, reaching 30 , which is approximately twice as fast as the compared alternatives. This performance meets the basic requirements for real–time detection even under limited computational resources.

Table 3.

Inference speed comparison evaluated on the SIRST dataset using an Intel Xeon Platinum 8352 V CPU.

4.5. Ablation Study

In this subsection, we compare our WSNet with several variants to investigate the potential advantages brought by our network modules and design choices.

Why Width, Not Depth? This design choice may seem counterintuitive from the perspective of conventional deep learning theory, where deep and narrow architectures are typically considered more effective for most computer vision tasks. However, this assumption often does not hold in the context of Infrared Small Target Detection (IRSTD). To validate our perspective, we conducted an experiment by replacing the Width Extension Module (WEM) with standard ResBlocks [59], progressively stacking them to construct deeper networks. This allows us to examine how increasing model depth affects performance. As shown in Table 4, increasing network depth does not lead to consistent gains across benchmark datasets. Beyond a certain depth, performance declines—a trend attributable to the limited semantic complexity in infrared images, which makes excessively deep architectures unnecessary and often counterproductive. Furthermore, infrared targets are typically small and dim, making them prone to overfitting and information loss (fine–grained feature of target) in deeper layers. Although techniques such as multi–layer feature fusion can mitigate this issue, they often introduce significant computational and parameter overhead. Given these observations, we shift focus from depth to width, offering a more efficient and task–appropriate strategy for IRSTD.

Table 4.

Results by stacking different numbers of ResBlocks. The parts in bold font are the best results.

Impact of WEM and CSHA. As shown in Table 5, we conduct ablation studies to validate the effectiveness of WEM and CSHA on different datasets. For WSNet without both WEM and CSHA, a dramatic decrease in all metrics is observed compared to the standard WSNet. When WSNet is modified to exclude either WEM or CSHA, all metrics show varying levels of improvement; however, there remains a significant performance gap between these variants and the standard WSNet model.

Table 5.

Ablation study of the WEM and CSHA in , , on different datasets.

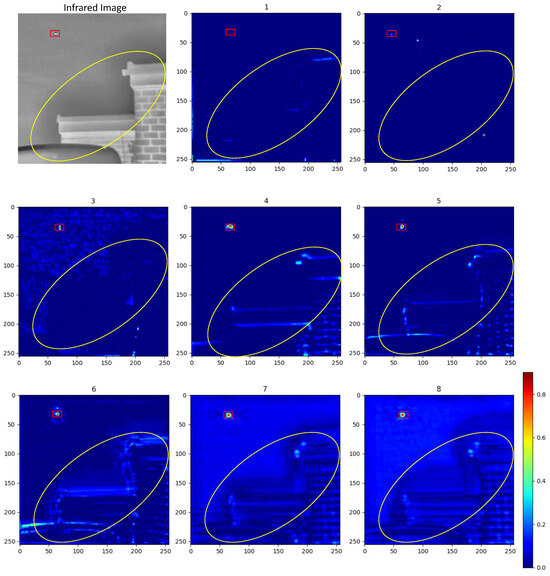

Impact of the Number of WEM Blocks. As shown in Table 6, we conduct ablation experiments to evaluate the impact of using different numbers of WEM blocks. For the first six blocks, we adopt the same configuration as illustrated in Figure 5. For additional blocks beyond that, we continue to expand the model’s receptive field to capture richer contextual information. The results indicate that increasing the number of blocks generally improves performance within the first six WEM blocks, which can be attributed to the enhanced feature representation capacity resulting from a systematic expansion of the network’s width. However, as more blocks are added, a slight performance degradation is observed. This may be due to the fact that while the feature representation ability improves initially with more blocks, beyond a certain point, the gains diminish and the model becomes more susceptible to overfitting. Visualized heatmaps in Figure 9 support the idea that the structured integration of pooling, convolution, and dilated convolution within the WEM significantly enhances its ability to highlight salient regions, increases feature diversity, and captures contextual information more effectively. Although, when the number of blocks exceeds a certain threshold, further increasing them may result in the over–amplification of contextual information.

Table 6.

Ablation study on the different number of WEM blocks in , , and on different datasets. The parts in bold font are the standard WEM.

Figure 9.

Heatmaps of WEM outputs with varying numbers of blocks. Target is marked in red, useful contextual information is marked in yellow.

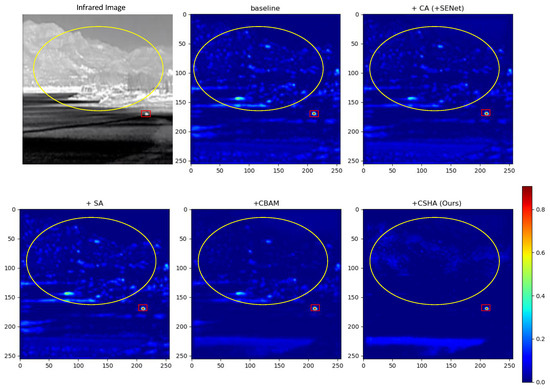

Impact of the Design Choice of CSHA. As shown in Table 7, we conduct ablation experiments to evaluate the effectiveness of different design choices for the CSHA module, including the selection of the parameter p in Lp pooling. The baseline model, which does not include the CSHA module, exhibits inferior performance. Adding either channel attention (CA) or spatial attention (SA) individually improves performance, with each component playing a distinct role: CA suppresses irrelevant regions by modulating channel–wise contributions, while SA directs spatial attention toward discriminative local features, thereby reducing the likelihood of missed detections. Furthermore, compared to the widely used CBAM—which relies on Max and Average Pooling in its channel attention component—our CSHA module adopts Lp pooling for more effective feature aggregation. We also explore the influence of the pooling parameter p, noting that corresponds to Average Pooling and approximates Max Pooling, both of which yield suboptimal results for IRSTD. In contrast, balances the preservation of global feature distribution with robustness to outliers, leading to better overall performance. Visual results in Figure 10 further illustrate that CSHA enhances the saliency of meaningful target regions while suppressing noise that could otherwise trigger false alarms.

Table 7.

Ablation study on the design choice and parameter p selection of CSHA in , , and on different datasets.

Figure 10.

Heatmaps of CSHA outputs with different design choices. Target is marked in red, noise information is marked in yellow.

The Impact of Low–level and High–level Feature Fusion Choice and the Multi–scale Feature Fusion Choice in WEM. As shown in Table 8, we conduct ablation studies to evaluate the effectiveness of different design choices for low–level and high–level feature fusion, as well as for multi–scale feature fusion in the WEM. The results indicate that using a simple skip connection with summation to integrate low–level and high–level features yields better performance across most datasets, despite minor degradations in compared to AFF–ResBlock [60]. For multi–scale feature fusion in the WEM, the summation operation consistently outperforms concatenation across all metrics. These empirical findings suggest that even simple fusion strategies can be highly effective in our model.

Table 8.

Ablation study on the design choice of low–level and high–level feature fusion and WEM’s multi–scale features fusion in , , and on different datasets. The parts in bold font are the original design choice of WSNet on different datasets.

4.6. The Experimental Findings

Our experimental results confirm that in Infrared Small Target Detection, expanding network width is more effective than increasing depth, as excessive depth leads to performance degradation. The proposed Width Extension Module (WEM) and Channel–Spatial Hybrid Attention (CSHA) are both essential, with their removal causing significant performance drops. The optimal configuration uses six WEM blocks, beyond which returns diminish. CSHA, with its Lp pooling design, outperforms conventional attention mechanisms by better suppressing noise and emphasizing meaningful features. Furthermore, simple summation–based feature fusion proves more effective than complex fusion strategies. These findings collectively demonstrate that a width–prioritized, lightweight architecture with streamlined modules is well suited to the low–semantic nature of infrared imagery.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we propose WSNet, a wide and shallow network tailored for IRSTD. By leveraging a wide and shallow architecture and introducing the Width Extension Module and Channel–Spatial Hybrid Attention, WSNet effectively enhances feature representation while maintaining an extremely lightweight structure. With only 0.054 M parameters and 1.050 G FLOPs, WSNet matches SOTA methods on multiple benchmarks, yet requires significantly less computation and memory. Its efficient design enables real–time inference on CPUs, making it highly suitable for deployment in embedded and resource–constrained environments. WSNet provides a practical and effective solution for real–world IRSTD applications and offers a new inspiration for lightweight model design in this field.

Limitation. Although WSNet achieves an excellent balance between detection accuracy and inference speed, it exhibits a relatively high False Alarm Rate (Fa) in semantically complex scenes. This limitation arises from its shallow architecture, which is less effective at extracting high–level semantic features, leading to increased false alarms. While stacking additional convolutional layers at the initial stage could enhance semantic representation which help lower Fa, it would also raise computational costs. Since WSNet is designed for real–time deployment on resource–limited devices such as CPUs and embedded platforms, a deliberate trade–off among detection performance, false alarms, and inference efficiency was made to ensure practical usability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.L. and Y.L. (Yihan Luo); methodology, P.L. and Y.L. (Yihan Luo); software, P.L., X.Z. and H.J.; validation, X.Z. and H.J.; formal analysis, S.X. and H.J.; investigation, S.X. and Y.L. (Yaqing Liu); resources, Y.L. (Yihan Luo); data curation, Y.L. (Yaqing Liu); writing––original draft preparation, P.L.; writing––review and editing, Y.L. (Yihan Luo) and H.J.; visualization, X.Z.; supervision, Y.L. (Yihan Luo) and H.J.; project administration, Y.L. (Yihan Luo); funding acquisition, Y.L. (Yihan Luo). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (62271468).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets utilized in this study are publicly accessible. All data supporting the findings of this work, including those used for training and testing, can be found in the repository associated with this project (accessed on 15 January 2025) at https://github.com/CPaul33/WSNet.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhao, M.; Li, W.; Li, L.; Hu, J.; Ma, P.; Tao, R. Single-frame infrared small–target detection: A survey. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2022, 10, 87–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, R.; Wang, C.; Peng, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Han, J.; Huang, F.; Yu, Y.; Fu, Q. Infrared small target segmentation networks: A survey. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 143, 109788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Sun, X.; Liu, M.; Ye, C.; Zhou, X. Small infrared target detection based on weighted local difference measure. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 54, 4204–4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tao, D. Empowering things with intelligence: A survey of the progress, challenges, and opportunities in artificial intelligence of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 7789–7817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teutsch, M.; Krüger, W. Classification of small boats in infrared images for maritime surveillance. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Waterside Security Conference, Carrara, Italy, 3–5 November 2010; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Hong, D.; Chanussot, J. UIU–Net: U–Net in U–Net for infrared small object detection. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 32, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivest, J.F.; Fortin, R. Detection of dim targets in digital infrared imagery by morphological image processing. Opt. Eng. 1996, 35, 1886–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, S.D.; Er, M.H.; Venkateswarlu, R.; Chan, P. Max–mean and max–median filters for detection of small targets. In Signal and Data Processing of Small Targets 1999; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1999; Volume 3809, pp. 74–83. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.; Bruzzone, L.; Gao, C.; Li, B. Infrared small target detection based on facet kernel and random walker. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 7104–7118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.P.; Li, H.; Wei, Y.; Xia, T.; Tang, Y.Y. A local contrast method for small infrared target detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2013, 52, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Moradi, S.; Faramarzi, I.; Liu, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Q. A local contrast method for infrared small–target detection utilizing a tri–layer window. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 17, 1822–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Moradi, S.; Faramarzi, I.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, N. Infrared small target detection based on the weighted strengthened local contrast measure. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2020, 18, 1670–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Meng, D.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Hauptmann, A.G. Infrared patch–image model for small target detection in a single image. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2013, 22, 4996–5009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Peng, L.; Zhang, T.; Cao, S.; Peng, Z. Infrared small target detection via non–convex rank approximation minimization joint l2,1 norm. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Wu, Y. Reweighted infrared patch–tensor model with both nonlocal and local priors for single–frame small target detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2017, 10, 3752–3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Peng, Z. Infrared small target detection based on partial sum of the tensor nuclear norm. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, J.; An, W. Infrared dim and small target detection via multiple subspace learning and spatial–temporal patch–tensor model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 59, 3737–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhou, L.; Wang, L. Miss detection vs. false alarm: Adversarial learning for small object segmentation in infrared images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 8509–8518. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Barnard, K. Asymmetric contextual modulation for infrared small target detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2021; pp. 950–959. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Xiao, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Li, M.; An, W.; Guo, Y. Dense nested attention network for infrared small target detection. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 32, 1745–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, R.; Yang, Y.; Bai, H.; Zhang, J.; Guo, J. ISNet: Shape matters for infrared small target detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 877–886. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.; Li, B.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, C.; Liu, T.; Yang, J.; An, W.; Guo, Y. MTU–Net: Multilevel TransUNet for space–based infrared tiny ship detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, L.; Cao, S.; Pu, T.; Peng, Z. Attention–guided pyramid context networks for detecting infrared small target under complex background. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 4250–4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, R.; Zheng, B.; Wang, H.; Fu, Y. Infrared small target detection with scale and location sensitivity. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 17490–17499. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhang, J. IRSAM: Advancing segment anything model for infrared small target detection. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Xu, L.; Yu, Z.; Shi, Y.; Mu, C.; Xu, M. Deep–IRTarget: An automatic target detector in infrared imagery using dual–domain feature extraction and allocation. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2021, 24, 1735–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Yang, B.; Xu, L.; Huang, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, Y. A benchmark and frequency compression method for infrared few–shot object detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5001711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Qin, H.; Yan, X.; Akhtar, N.; Mian, A. Sctransnet: Spatial–channel cross transformer network for infrared small target detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zhu, W.; Li, N.; Li, C.; Xiong, K.; Wang, Z.; Feng, W.; Jiang, J.; Quan, Y. Forgetting the background: A masking approach for enhanced infrared small target detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5005615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Ma, T.; Fei, R.; Li, J. A Lightweight Feature Enhancement Model for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 15224–15234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, F.; Liu, T.; Lin, Z.; An, W.; Guo, Y. Monte Carlo linear clustering with single–point supervision is enough for infrared small target detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 1009–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Du, H.Y.; Zhao, Y.J.; Dong, L.Q.; Hui, M.; Wang, S.X. Image small target detection based on deep learning with SNR controlled sample generation. In Current Trends in Computer Science and Mechanical Automation; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Q.; Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Xu, C. Ghostnet: More features from cheap operations. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 1580–1589. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chu, G.; Chen, L.C.; Chen, B.; Tan, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V.; et al. Searching for mobilenetv3. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1314–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Iandola, F.N.; Han, S.; Moskewicz, M.W.; Ashraf, K.; Dally, W.J.; Keutzer, K. SqueezeNet: AlexNet–level accuracy with 50× fewer parameters and <0.5 MB model size. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.07360. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, M.; Lai, S.; Huang, J.; Wei, X.; Chai, Z.; Luo, J.; Wei, X. Rethinking bisenet for real–time semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 9716–9725. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Lin, M.; Sun, J. Shufflenet: An extremely efficient convolutional neural network for mobile devices. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 6848–6856. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. Mixconv: Mixed depthwise convolutional kernels. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.09595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, F. Xception: Deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1251–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, H.T.; Sun, J. Shufflenet v2: Practical guidelines for efficient cnn architecture design. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 116–131. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Cheng, L.; Yang, X.; Feng, P.; Liu, L.; Wu, N. TBC–Net: A real–time detector for infrared small target detection using semantic constraint. arXiv 2019, arXiv:2001.05852. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Xiao, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; An, W. Repisd-net: Learning efficient infrared small-target detection network via structural re-parameterization. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5622712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, R.; Wang, C.; Yu, Y.; Peng, Z.; Yang, M.; Huang, F.; Fu, Q. LW-IRSTNet: Lightweight infrared small target segmentation network and application deployment. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5621313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Pu, H.; Wang, F.; Hu, Z.; Wang, L. The expressive power of neural networks: A view from the width. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.T.; Koc, L.; Harmsen, J.; Shaked, T.; Chandra, T.; Aradhye, H.; Anderson, G.; Corrado, G.; Chai, W.; Ispir, M.; et al. Wide & deep learning for recommender systems. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Deep Learning for Recommender Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 15 September 2016; pp. 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zagoruyko, S.; Komodakis, N. Wide residual networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1605.07146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2818–2826. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Q.; Wang, Z.; Tan, F.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, W. RISTDnet: Robust infrared small target detection network. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 19, 7000805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Bai, J.; Yang, F.; Bai, X. Receptive-field and direction induced attention network for infrared dim small target detection with a large–scale dataset IRDST. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5000513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, W.; Hu, X.; Yang, J. Selective kernel networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 510–519. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze–and–excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Barnard, K. Attentional local contrast networks for infrared small target detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 9813–9824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Y.; Gieseke, F.; Oehmcke, S.; Wu, Y.; Barnard, K. Attentional feature fusion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2021; pp. 3560–3569. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.