Highlights

What are the main findings?

- The proposed SCMT-Net integrates single-frame and multi-frame sub-networks, achieving superior performance in infrared small target detection, particularly under low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) conditions.

- The decoder incorporates a Motion-Aware Enhancement Block (MAEB), composed of Motion-Driven Three-dimensional Pooling (MotionPool3d) and a Temporal Consistency Enhancement Module (TCEM). These components jointly extract stable motion features and effectively suppress short-term loss and positional drift.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- SCMT-Net provides a unified and interpretable detection network that leverages spatial–temporal feature synergy to address weak target responses and background interference in complex infrared scenes.

- MAEB features a concise and efficient design tailored to the motion characteristics of infrared small targets, offering strong scalability and robustness for applications in remote sensing and intelligent perception.

Abstract

Infrared small target (IRST) detection remains a challenging task due to extremely small target sizes, low signal-to-noise ratios (SNR), and complex background clutter. Existing methods often fail to balance reliable detection with low false alarm rates due to limited spatial–temporal modeling. To address this, we propose a multi-frame network that synergistically integrates spatial curvature and temporal motion consistency. Specifically, in the single-frame stage, a Gaussian Curvature Attention (GCA) module is introduced to exploit spatial curvature and geometric saliency, enhancing the discriminability of weak targets. In the multi-frame stage, a Motion-Aware Encoding Block (MAEB) utilizes MotionPool3D to capture temporal motion consistency and extract salient motion regions, while a Temporal Consistency Enhancement Module (TCEM) further refines cross-frame features to effectively suppress noise. Extensive experiments demonstrate that the proposed method achieves advanced overall performance. In particular, under low-SNR conditions, the method improves the detection rate by 0.29% while maintaining a low false alarm rate, providing an effective solution for the stable detection of weak and small targets.

1. Introduction

Infrared Small Target Detection (IRSTD) plays a vital role in vision systems and maritime surveillance [1,2,3]. However, targets are typically characterized by extremely small sizes [4], a lack of distinctive shapes [5,6,7], and low signal-to-noise ratios (SNR), often submerged in heavy background clutter. Traditional methods, such as multi-filter approaches [8,9], sparse low-rank decomposition [10,11,12,13], and HVS-inspired models [14], rely on handcrafted features. While effective in simple scenarios, they lack adaptability to dynamic real-world environments.

In recent years, deep learning has advanced single-frame detection (SIRST). Methods like ACM [15], DNANet [5], and UIU-Net [16] have introduced mechanisms like asymmetric context modulation and dense nested attention to enhance feature representation. Despite these improvements, relying solely on spatial information remains insufficient for extremely dim targets, as they are easily confused with background noise without temporal cues. To break through the performance bottleneck of single-frame processing, recent remote sensing research [17,18,19] has shifted towards sequence-based analysis, aiming to leverage rich motion context for more reliable perception. In this context, Multi-frame Infrared Small Target Detection (MIRST) exploits spatiotemporal correlations to differentiate moving targets from background noise. Approaches such as DTUM [20], LVNet [21], MOCID [22], and SSTNet [23] have made significant strides. For instance, DTUM [20] utilizes direction-coded blocks for motion mapping, while MOCID [22] employs spatiotemporal attention to capture motion context. However, existing methods often struggle to effectively accumulate weak target signals against intense noise interference. Consequently, under low-SNR conditions, the target features remain submerged in complex background clutter, leading to unstable detection and frequent missed targets.

To address the aforementioned challenges, this paper proposes a Spatial Curvature and Motion-Temporal Feature Synergistic Network (SCMT-Net), which integrates two functionally complementary sub-networks within a unified end-to-end network. First, the single-frame spatial curvature enhancement sub-network, built upon ResUNet [24], introduces a Gaussian Curvature Attention (GCA) module to enhance the spatial geometric saliency and local peak response of weak targets. This design improves target discriminability under complex backgrounds and provides more stable spatial feature representations for subsequent temporal modeling. Second, the core of the multi-frame motion-temporal consistency sub-network is a motion-consistency encoder, which aims to deeply exploit and accurately model cross-frame temporal dependencies, thereby capturing stable target representations along the temporal dimension. The encoder is sequentially composed of a Motion-Aware Encoding Block (MAEB) and a Temporal Consistency Enhancement Module (TCEM): MAEB explicitly extracts inter-frame motion differences through motion-driven 3D pooling and generates local displacement information, while TCEM accumulates and propagates stable motion responses over time using this displacement information, thereby reinforcing temporally consistent target features and suppressing inconsistent background noise. The sequential integration of these components, optimized in an end-to-end manner, achieves simultaneous improvements in detection accuracy and robustness against interference.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

- We propose an attention mechanism that incorporates curvature priors. Explicitly modeling local geometric variations enhances the spatial features and discriminability of weak targets, effectively suppressing background interference and providing high-quality spatial representations for subsequent temporal consistency modeling.

- We design an enhancement module that accumulates and propagates stable motion responses along the temporal dimension using local displacement information. This strengthens cross-frame motion-consistent target features and effectively suppresses inconsistent background noise, thereby improving the robustness of multi-frame detection.

- We introduce an integrated encoding structure that combines motion pooling, temporal consistency enhancement, and convolutional fusion. Specifically, motion-driven 3D pooling is employed to explicitly extract inter-frame motion differences and generate local displacement information; TCEM is then invoked within the block to generate consistency response maps; finally, the enhanced features are fused via convolution, yielding multi-frame feature representations that are both motion-sensitive and temporally stable.

- Extensive experiments on public MIRST datasets demonstrate that the proposed method significantly outperforms existing state-of-the-art approaches in terms of detection accuracy and robustness against interference, with particularly strong performance under low-SNR conditions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Single-Frame Infrared Small Target Detection

Early studies on single-frame infrared small target detection largely relied on handcrafted features and prior assumptions. Main approaches include filtering-based enhancement, human visual system (HVS) modeling, and low-rank sparse decomposition. Filtering-based methods [8,9], such as maximum median/mean filtering and top-hat transformations, suppress background textures but often confuse high-frequency edges with targets. HVS-based methods, such as WSLCM [25] and TLLCM [26], detect targets by exploiting local contrast differences. However, these methods depend strongly on priors and exhibit limited adaptability. Low-rank decomposition methods, such as NRAM and IPI [6,11], separate targets by modeling the background’s low-rank property and the target’s sparsity. Nevertheless, they are prone to false detections in backgrounds with strong edges or bright spots and are highly sensitive to parameter settings.

With the development of deep learning, researchers have proposed various structural innovations to enhance feature representation and computational efficiency. MSHNet [27] combines scale-sensitive losses with multi-scale detection heads to improve accuracy across varying target sizes. FC3-Net [28] explores feature compensation and cross-layer correlation to mitigate the attenuation of small-target features during downsampling. Regarding efficiency, SPMixQ [29] maintains high detection accuracy under mixed-precision quantization, while IRPruneDet [30] leverages wavelet regularization and soft channel pruning to reduce model size. Although these methods achieve strong performance in spatial feature modeling, they fundamentally lack the exploitation of temporal information. Consequently, in video scenarios—particularly when detecting moving targets under low-SNR conditions—they often suffer from discontinuous trajectories and elevated false alarm rates.

2.2. Multi-Frame Infrared Small Target Detection

Due to the inherent lack of temporal information in single-frame detection, the field of remote sensing target perception is increasingly favoring multi-frame analysis [31,32,33], as leveraging continuous frame sequences can significantly enhance the robustness of moving target perception. Following this trend, Multi-frame Infrared Small Target Detection (MIRST) exploits spatiotemporal correlations to differentiate moving targets from background noise. A typical paradigm first extracts spatial features from individual frames and then employs temporal aggregation modules. For instance, NeurSTT [34] introduced a low-rank informed background approximation network to enhance spatial–temporal representation; TransVOD [35] adopted a temporally deformable Transformer to aggregate multi-frame features; and SSTNet [23] employed a slice-based spatiotemporal network to learn motion patterns across slices. While these methods demonstrate strong capabilities in temporal aggregation, their spatial feature modeling often remains relatively simple and fails to effectively integrate motion information for fine-grained localization.

Beyond simple aggregation, recent approaches explicitly model motion dependencies. DTUM [20] models motion differences between targets and background through motion-to-data mapping. Luo et al. [36] proposed deformable feature alignment to improve cross-frame robustness. Other methods leverage convolutions [37] or establish global dependencies using spatiotemporal Transformers [38]. Although these methods outperform single-frame approaches, they still face challenges in capturing reliable motion features of weak targets under low-SNR scenarios, where weak target signals are easily overwhelmed by intense noise, leading to detection failures.

2.3. Geometric Priors and Geometry-Informed Networks

Geometric priors and structural constraints play an important role in remote sensing image analysis, where diverse manually designed descriptors [39,40] are extensively employed to characterize the intrinsic spatial patterns and saliency of targets. Given that infrared small targets typically manifest as blob-like structures, utilizing these geometric properties to distinguish targets from background clutter has proven effective. However, traditional manually designed priors often lack adaptability in complex dynamic target scenarios.

Recently, deep networks have begun embedding mathematical priors to enhance interpretability. For instance, RKformer [41], ISNet [42], and RDIAN [43] incorporate Runge–Kutta methods, Taylor expansions, and directional attention, respectively. Notably, GCI-Net [44] introduces a Gaussian curvature branch to preserve target texture. However, as a single-frame method, it ignores crucial temporal consistency. In low-SNR scenarios, spatial geometric features alone are easily corrupted by noise. This motivates us to integrate Gaussian Curvature Attention (GCA) with temporal motion modeling, where enhanced spatial geometric features serve as a robust foundation for subsequent temporal consistency extraction, thereby achieving robust detection in complex environments and for low signal-to-noise ratio targets.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Overall Architecture

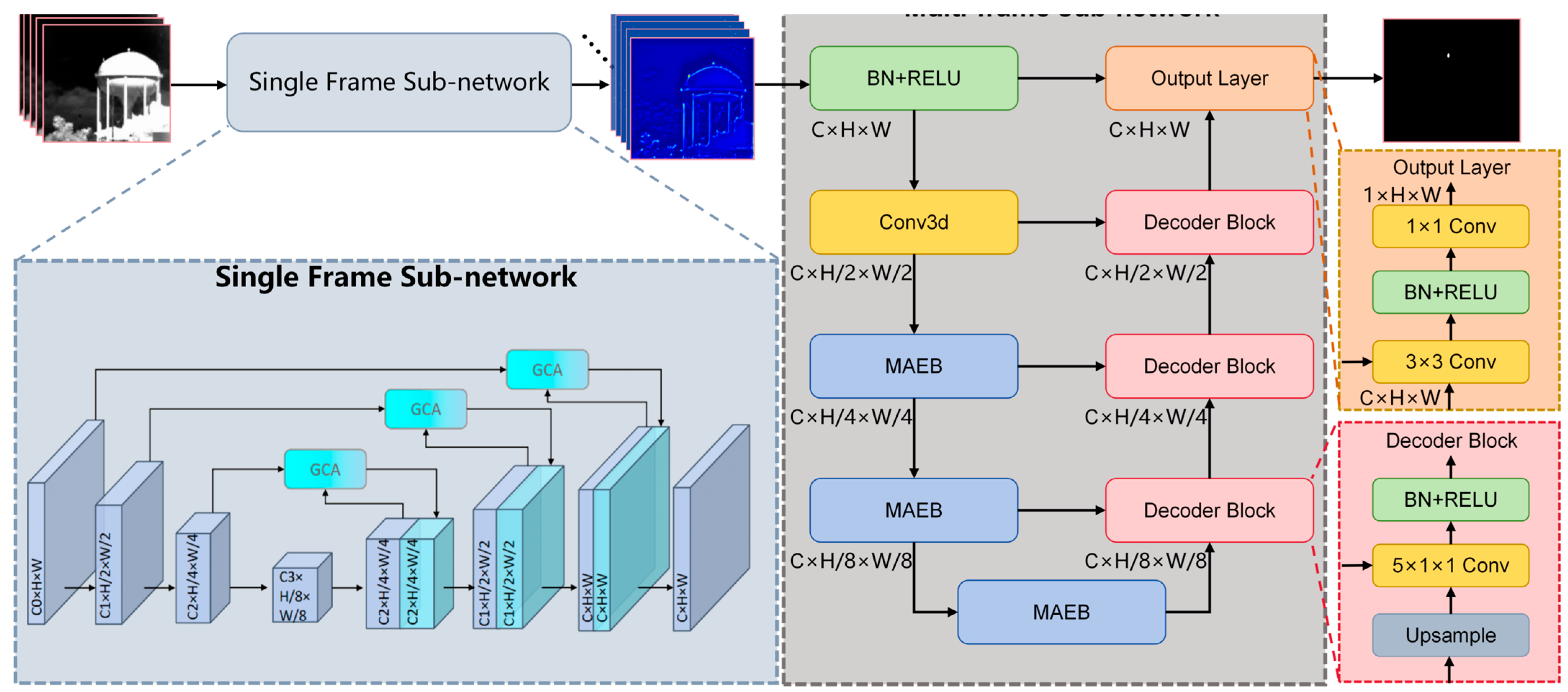

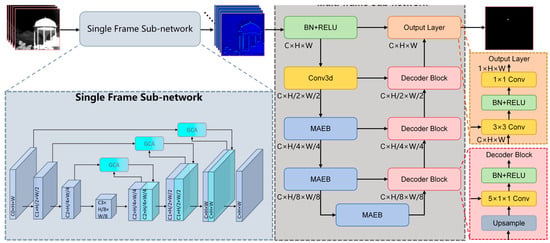

Figure 1 presents the overall architecture of the proposed SCMT-Net. The network is sequentially composed of a single-frame spatial curvature enhancement sub-network and a multi-frame motion-temporal consistency sub-network.

Figure 1.

Overall architecture of SCMT-Net. The network consists of a single-frame subnetwork and a multi-frame subnetwork. A sequence of five consecutive input frames is first processed by the single-frame subnetwork to extract spatial feature representations. These features are then fed into the multi-frame subnetwork, where cross-frame temporal dependencies are modeled to achieve target detection.

In the single-frame sub-network, we adopt a lightweight four-layer ResUNet [24] as the backbone. Compared with the standard five-layer structure, one encoder–decoder depth is removed to avoid excessive downsampling of infrared small targets [45], which could otherwise lead to detail loss, while also reducing computational cost by decreasing the parameter count from 14.56 M to 3.61 M, a reduction of approximately 75.2%. Gaussian Curvature Attention (GCA) modules are embedded into three key skip connections of the encoder–decoder, enhancing geometric saliency in shallow and intermediate features before fusion. This design highlights the spatial morphology of weak targets and effectively suppresses background noise. The single-frame sub-network ultimately outputs spatial feature maps with a fixed number of channels, which serve as the input to the multi-frame branch.

In the multi-frame sub-network, the encoder employs Motion-Aware Encoding Blocks (MAEB) to perform cross-frame feature aggregation and motion information extraction. Referring to the decoder design in [20], the decoder adopts a progressive upsampling and skip-connection structure: at each stage, features are first upsampled and concatenated with the corresponding encoder outputs, followed by feature fusion through a 5 × 1 × 1 convolution, batch normalization, and ReLU activation. This temporal kernel is specifically designed to aggregate context across frames. In the final output layer, the result of the last decoder stage is concatenated with the skip-connected features from the initial convolutional layer, and then sequentially processed by a 3 × 3 convolution, batch normalization [46], and ReLU activation, before a 1 × 1 convolution generates the detection results. The rationale for employing a 3 × 3 spatial convolution here is to introduce a local receptive field for feature refinement, effectively smoothing out isolated high-frequency noise. This sub-network leverages motion-driven 3D pooling to extract salient motion regions and employs a temporal consistency enhancement mechanism to accumulate and propagate stable cross-frame target responses, while suppressing inconsistent background interference, thereby improving detection robustness in dynamic scenarios. Overall, SCMT-Net provides high-quality geometrically enhanced features in the spatial domain through the GCA module, while capturing stable cross-frame target features in the temporal domain via MAEB, achieving high-precision infrared small target detection under low-SNR conditions.

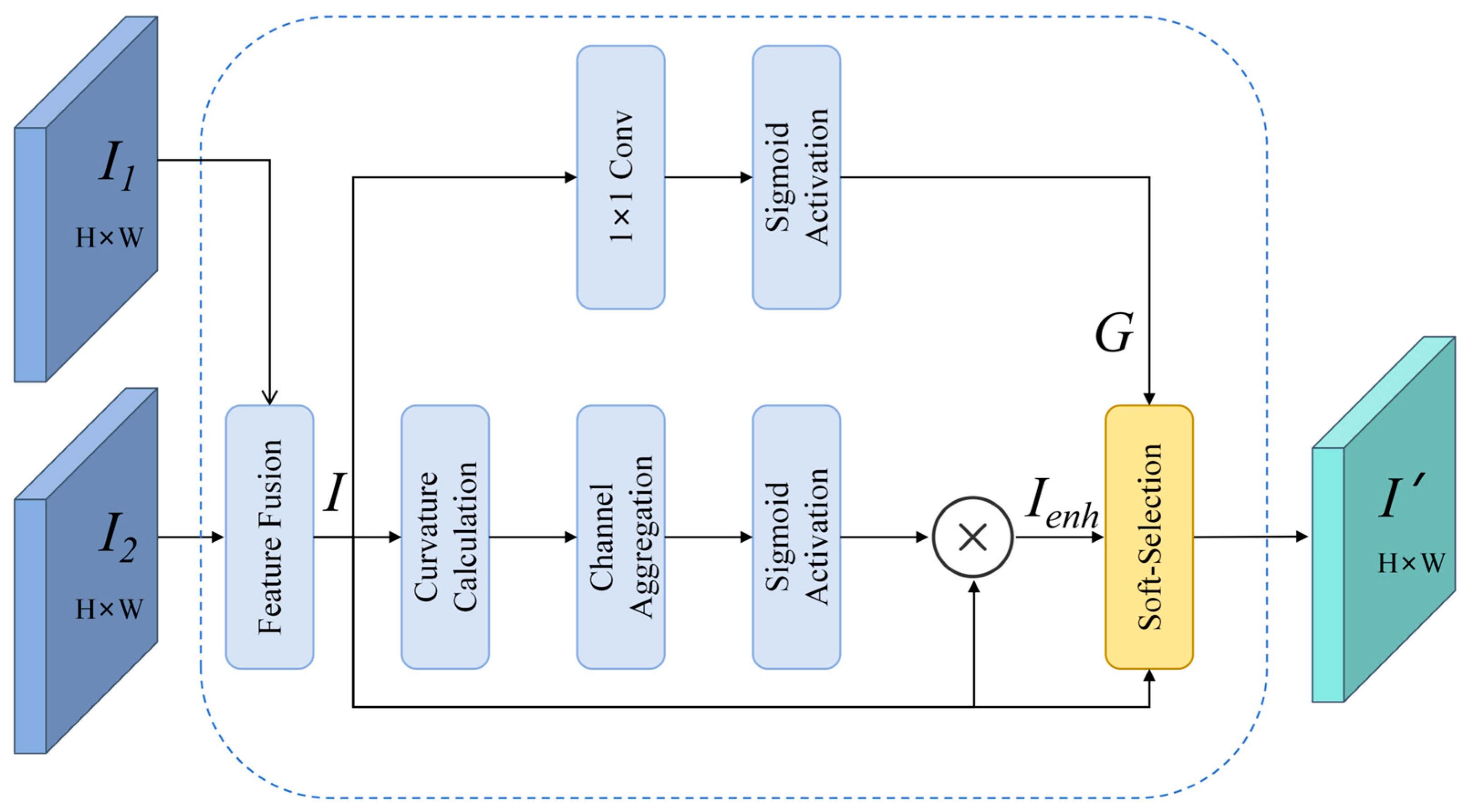

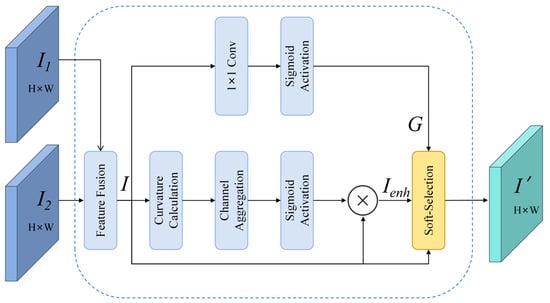

3.2. Gaussian Curvature Attention Modules

In the single-frame spatial curvature enhancement sub-network, we construct a feature extraction network based on a lightweight four-layer Res-UNet backbone. To enhance geometric saliency, Gaussian Curvature Attention (GCA) modules are embedded into three key skip connections, where shallow and intermediate features are refined prior to fusion. This design is inspired by [44], but differs significantly in implementation by operating directly on high-dimensional feature maps and incorporating a dynamic gating mechanism to robustly amplify saliency responses. As a result, the proposed design effectively suppresses noise interference in complex backgrounds. The detailed structure is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The specific structure of GCA.

Unlike methods that rely on grayscale preprocessing, our module computes geometric derivatives on the input feature maps via convolutions to preserve channel-wise semantic information. Subsequently, first-order convolution kernels (Sobel operators) are applied to compute gradients in the horizontal and vertical directions :

In this formulation, , represents the grayscale matrix of the input feature map, and the symbol * denotes the two-dimensional convolution operation. The first-order derivatives characterize both the direction and magnitude of intensity variations, serving as the foundation for edge and texture extraction. Subsequently, second-order convolution kernels are employed to compute the second-order partial derivatives :

Second-order derivatives characterize the surface’s curvature and variation trends, forming an indispensable component of curvature computation. Combining first- and second-order information enables a more comprehensive description of local geometric structure. Based on these derivatives, we compute the Gaussian curvature K:

where ϵ denotes a numerical stabilization term. Given the multi-channel nature of the feature maps, we require a unified descriptor to represent global spatial saliency. To achieve this, we aggregate the curvature responses by computing the mean of their absolute values along the channel dimension. This approach captures the magnitude of geometric variations (both protrusions and depressions) while mitigating channel-specific noise. Subsequently, a Sigmoid activation is applied to map the aggregated values to [0, 1], generating the attention weights A:

The enhanced feature representation Ienh is then obtained by element-wise multiplication: .

Finally, to address the issue where curvature operators might amplify high-frequency noise in flat backgrounds, we introduce a Dynamic Gating Mechanism. A parallel branch computes a pixel-wise confidence gate G using a 1 × 1 convolution followed by a Sigmoid function. The final output I’ is produced via a soft-selection strategy:

It should be noted that while the GCA effectively filters random clutter, the module may also respond to certain static noise components that share similar geometric characteristics (e.g., high curvature) with the targets. Nevertheless, this enhancement is beneficial as it enables the recovery of more complete target contour details and more accurate shape reconstruction. These static noise responses can be effectively suppressed in the subsequent multi-frame motion-temporal consistency sub-network, thereby preserving the fine structural information of the target while eliminating irrelevant interference. In this way, spatial detail preservation and temporal robustness complement each other.

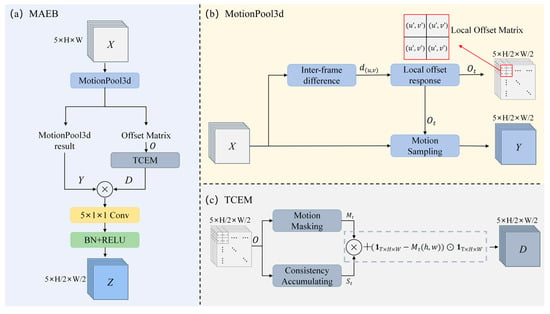

3.3. Motion-Aware Enhancement Block

3.3.1. Motion-Driven Three-Dimensional Pooling

In multi-frame infrared small target detection, conventional spatial pooling operations (e.g., max pooling and average pooling [47]) are prone to mis-sampling when processing motion features. When a pooling window contains background noise or reflection points that are brighter than the target pixels, conventional pooling directly samples these interfering pixels, thereby contaminating the motion features. This limitation arises because traditional pooling selects pixels solely based on absolute intensity, without considering the direction and magnitude of intensity variations.

From the perspective of motion feature modeling, the direction of intensity variation carries important semantic information about motion. Intensity enhancement (positive difference) typically corresponds to the appearance, approach, or radiation strengthening of a target, serving as the most direct signal of motion saliency. Conversely, intensity attenuation (negative difference) may correspond to the disappearance, recession, or partial occlusion of a target. Without distinguishing between these cases, pooling not only introduces static high-intensity noise but may also cause the loss of trajectory continuity when the target undergoes short-term intensity attenuation.

To this end, we design MotionPool3d, which introduces a motion sampling strategy based on variation types. Within each local window, the module first determines whether there exists a brightness-enhancement response; if so, the position with the maximum enhancement magnitude is selected. If no significant enhancement is detected, the position with the minimum brightness-attenuation magnitude is chosen instead. According to the global index of the selected position, the corresponding feature is directly sampled from the original feature map to generate the pooled output. This strategy suppresses static interference already at the sampling stage and, in cases of brightness decay, preserves the spatio-temporal trajectory of the target. As a result, it provides more stable motion features for subsequent temporal consistency modeling. The overall framework of this process is illustrated in Figure 3b.

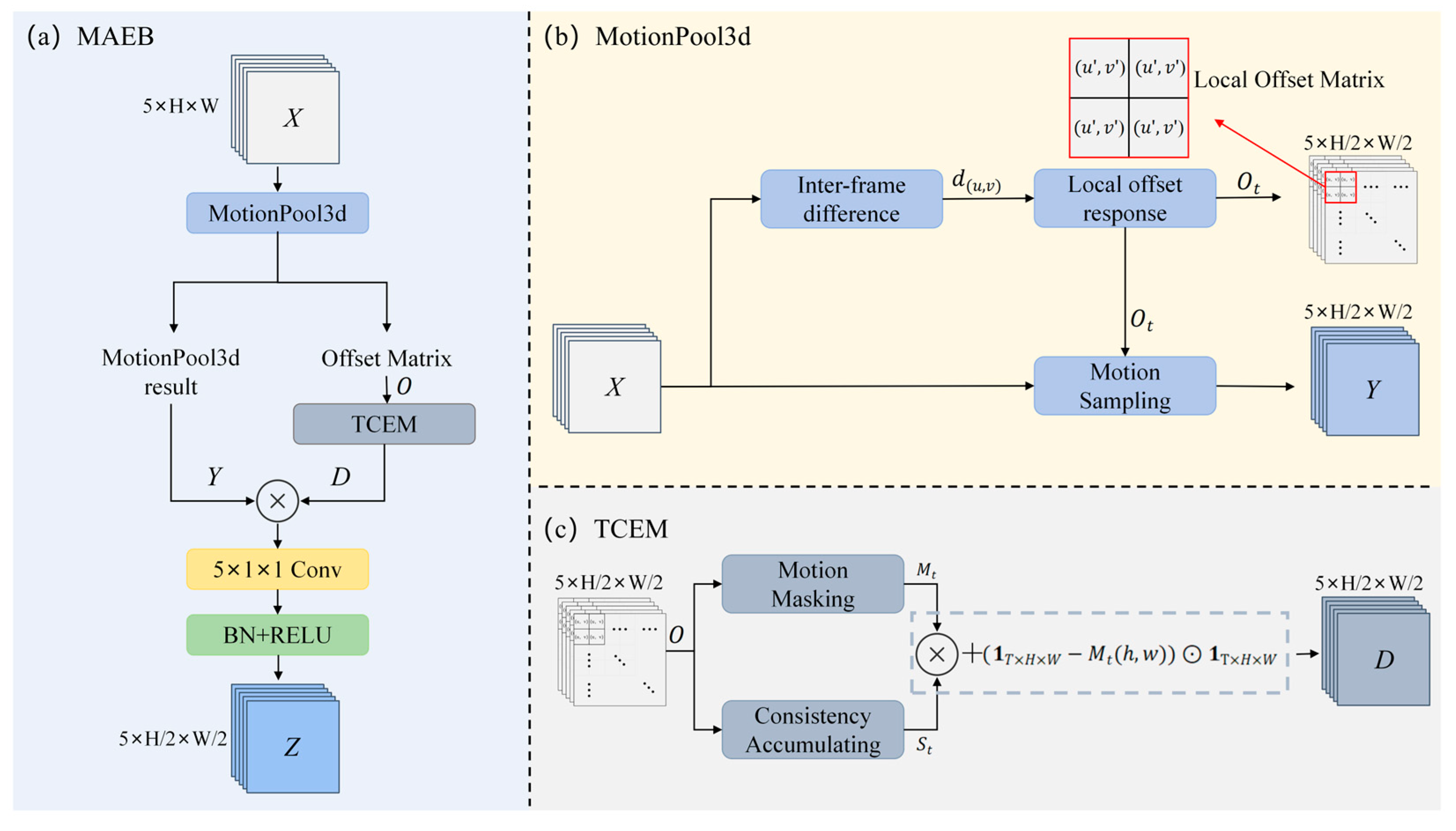

Figure 3.

Framework of MAEB. (a) Overall architecture of MAEB. (b) Structure of MotionPool3d within MAEB. (c) Structure of TCEM within MAEB.

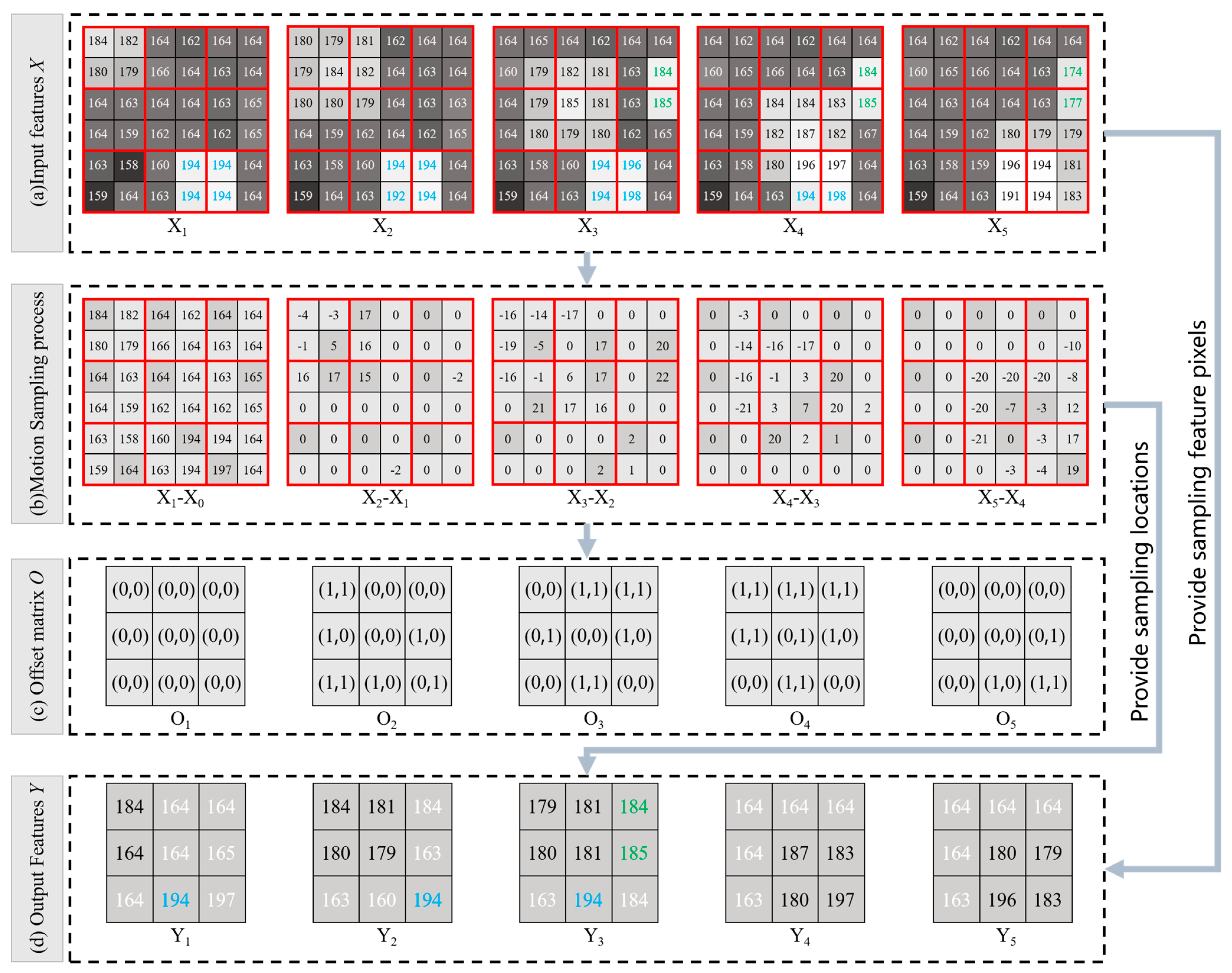

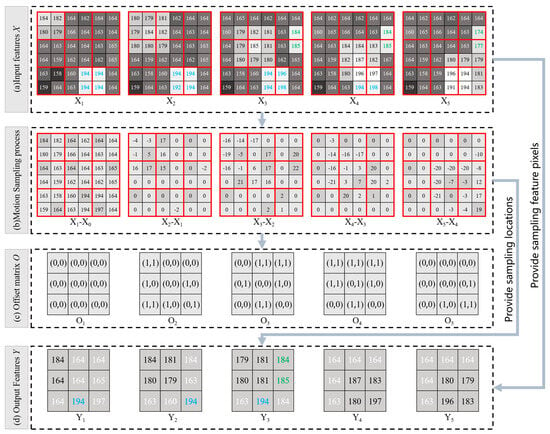

The detailed operations are illustrated in Figure 4. Specifically, given the input feature , where B denotes the batch size, C the number of channels, T the number of temporal frames, and H, W the spatial dimensions, zero-padding is first applied along the spatial dimensions to ensure that the pooling window fully covers the boundary regions. Subsequently, temporal differences between adjacent frames are computed along the time dimension:

where denotes a zero tensor. The differencing results preserve pixel variations induced by motion, while the static background ideally approaches zero.

Figure 4.

The red box denotes the sampling window. In subfigures (a,d), black characters represent target pixels, white characters represent background pixels, blue characters indicate background interference pixels, and green characters denote occasional noise pixels. In subfigure (b), the dark pixel blocks mark the sampling positions. In subfigure (c), coordinate rule is that 0 means no motion and 1 means motion, with the first value indicating x-direction and the second indicating y-direction.

Within each 2 × 2 local window, the differencing values are denoted as , where u and v represent the row and column coordinates inside the window, respectively, as illustrated in Figure 4c. When a target pixel exhibits displacement along either the row or column direction between consecutive frames, it is marked as a displacement response with a value of 1; otherwise, no response is recorded, and the value is set to 0. To emphasize motion saliency, a motion sampling strategy is adopted:

Priority is given to selecting the position with a positive differencing response; if no positive response exists, the position with the smallest magnitude of negative response is chosen instead. This strategy ensures that the most salient variations are captured within motion regions, while still providing stable responses in the absence of significant motion. As these local windows slide across the entire image, all local displacement values are naturally concatenated into a complete displacement matrix:

where stores the local displacement results of the tt-th frame within the window corresponding to spatial position , denoted as . The output features of MotionPool3d are then constructed by sampling the original input at the response positions indicated by . The resulting output feature map is expressed as follows:

Finally, MotionPool3d outputs the motion-sampled features , while simultaneously producing the local displacement matrix , which is utilized by the subsequent temporal consistency enhancement module to propagate stable motion responses along the temporal dimension. In this manner, MotionPool3d not only reduces spatial redundancy but also captures inter-frame motion variations more effectively, thereby maintaining stable detection performance in complex dynamic scenarios.

3.3.2. Temporal Consistency Enhancement Module

Although MotionPool3d can preferentially sample motion-salient pixels, two types of instability may still occur in video sequences. First, short-term loss: due to target brightness fluctuations, partial occlusions, or background interference, the motion response in certain frames may weaken or even vanish, resulting in discontinuities in the temporal detection sequence. Second, positional drift: under low signal-to-noise ratio conditions, the motion sampling positions may be perturbed by local noise, causing the target trajectory to become temporally inconsistent. The root cause of these issues lies in the lack of cross-frame constraints in motion features, which prevents the enforcement of spatial and intensity consistency between adjacent frames.

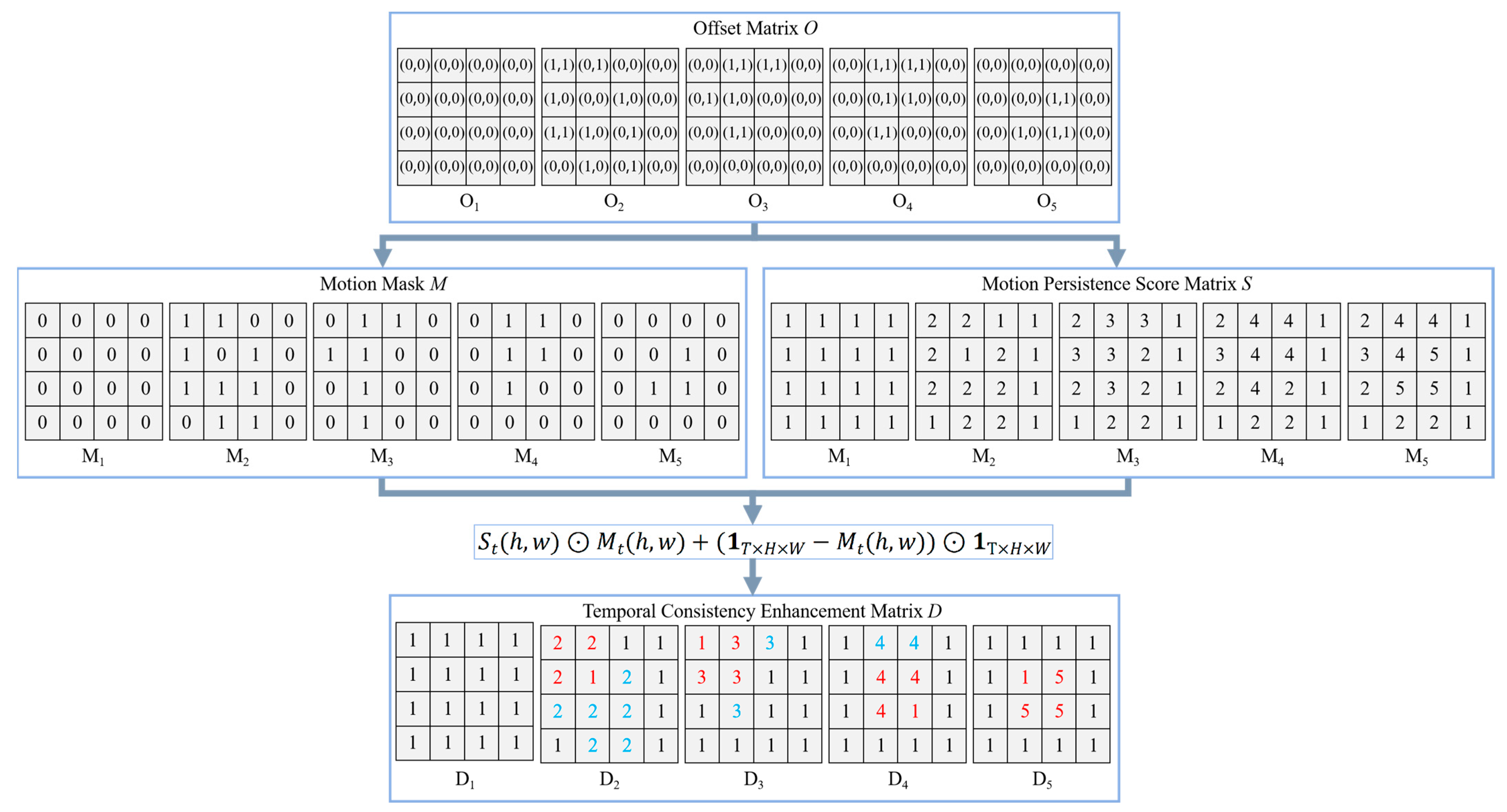

To address this, we design a Temporal Consistency Enhancement Module (TCEM), which leverages the local displacement tensor output by MotionPool3d to perform spatial inheritance and continuity scoring along the temporal dimension, thereby reinforcing stable motion trajectories. The overall framework of this process is illustrated in Figure 3c.

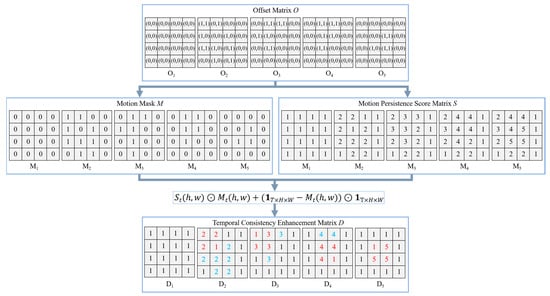

The detailed procedure is illustrated in Figure 5. Specifically, TCEM first determines whether each pixel in the current frame exhibits motion based on the local displacement, and defines a binary motion mask as:

where indicates whether pixel exhibits motion in frame t. Subsequently, a recursive accumulation of continuous motion scores is performed along the temporal dimension. At the initial frame , the score matrix is initialized as an all-zero matrix. For frame the score at each position is first updated by taking the maximum value of the scores from the previous frame within its spatial neighborhood:

Figure 5.

Temporal consistency enhancement operation. In the temporal consistency enhancement matrix, red characters indicate target positions, while blue characters denote clutter interference.

The neighborhood is defined as a 3 × 3 region centered at , including the target pixel itself together with its four adjacent and four diagonal neighbors, i.e., a total of nine positions. The motion continuity score matrix of the current frame is then updated as:

This method effectively models continuous motion features across frames. When the target undergoes slight spatial displacements between adjacent frames, as long as the displacement remains within the defined neighborhood, the score from the previous frame can be inherited and accumulated, thereby forming a continuous high-score trajectory. Finally, TCEM outputs the complete accumulated score matrix , which reflects the temporal length of continuous motion for each pixel. After processing all frames, a temporal consistency enhancement matrix is simultaneously generated:

Let denote an all-ones matrix. In this way, the newly activated motion positions in the current frame can be highlighted in the score map, and the temporal consistency enhancement matrix is obtained.

Through this local-displacement-based temporal consistency scoring, TCEM can directly enhance stable target responses during the inference stage without requiring additional loss function training. This effectively suppresses short-term loss and positional drift, enabling the detection results to exhibit higher continuity and robustness across image sequences.

3.3.3. Overall Structure of Motion-Aware Enhancement Block

The Motion-Aware Enhancement Block (MAEB) is designed to simultaneously exploit spatial saliency and temporal consistency information for multi-frame infrared small target detection. MAEB is composed of MotionPool3d and TCEM, integrating the advantages of both into a unified structure that highlights motion-salient regions while maintaining stable responses along the temporal dimension. Considering the significant differences in motion patterns between infrared small targets and background clutter, a relatively simple structure with shallow semantic representations is sufficient to accomplish this task, particularly with the introduction of variation-type-based priority sampling and continuous motion scoring mechanisms. Therefore, we construct this module to improve detection accuracy while suppressing the interference of clutter noise. The detailed architecture is illustrated in Figure 3c.

In the concrete implementation, MAEB directly integrates the motion-driven sampling results from MotionPool3d with the temporal consistency scoring matrix from TCEM into the feature computation. The input multi-frame features are first processed through MotionPool3d pooling:

where denotes the motion-driven pooled features, and represents the corresponding local displacement tensor. Subsequently, TCEM computes the temporal consistency score matrix based on the displacement information, which characterizes the continuous motion intensity of each position along the temporal dimension. The pooled features are then element-wise multiplied with the score map and passed through a 5 × 1 × 1 3D convolution, followed by batch normalization (BN) and ReLU activation, to obtain the enhanced feature representation:

where denotes the final output features, and ⊙ represents element-wise multiplication. By directly integrating the outputs of MotionPool3d and TCEM in this manner, MAEB can effectively suppress short-term loss and positional drift across different scenarios, thereby providing more stable and discriminative feature representations for subsequent detection.

4. Results

4.1. Dataset

This study employs the NUDT-MIRSDT dataset [20] to validate the proposed method. The dataset is specifically constructed for multi-frame infrared small target detection and contains 100 sequences with a total of 10,000 infrared frames. Among them, 80 sequences (8000 frames) are used for training and 20 sequences (2000 frames) for testing, with 9523 targets annotated in total.

The vast majority of targets have spatial sizes no larger than 9 × 9 pixels, covering diverse background complexities ranging from homogeneous sky to heterogeneous sea and urban terrain. All sequences are derived from real infrared imagery with artificially injected targets. To increase sample diversity and simulate realistic motion, the target shapes exhibit dynamic variations throughout the sequences, while the motion trajectories are modeled as regular curves superimposed with randomly generated jitter. While this semi-synthetic setup may introduce minor domain gaps regarding target thermal signatures, it preserves authentic background clutter statistics, thereby ensuring the credibility of the experimental results in verifying false alarm suppression. Following the partition strategy of the original dataset [20], we categorize the test set into two subsets based on Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) to strictly evaluate performance under different noise conditions: one containing 8 sequences with SNR < 3, and another containing 12 sequences with SNR ranging from 3 to 10.

The annotation method adopts pixel-level point labeling, i.e., recording the position of the brightest pixel within the target region. The annotation process is automatically completed by a self-developed program. To increase sample diversity, the targets exhibit morphological variations within the sequences, and their motion trajectories follow regular curves with random perturbations. The test portion of the dataset is pre-divided into two subsets according to the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which is defined as:

where denotes the maximum gray value within the target region, while and represent the mean and standard deviation of an 11 × 11 background window centered on the target, respectively. The first subset contains 8 sequences from 3, representing extremely weak target scenarios; the second subset contains 12 sequences from 10 3, representing normal-intensity target scenarios. This division facilitates the separate evaluation of the proposed method under low-SNR and normal-SNR conditions.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively and objectively evaluate the performance of the proposed method in multi-frame infrared small target detection, this study adopts Probability of Detection (Pd), False Alarm Rate (Fa), and Area Under Curve (AUC). Compared to conventional metrics like F1-score and Recall, these metrics are better suited for the characteristics of infrared small targets. Due to the extreme class imbalance (vast background vs. tiny targets), the F1-score is overly sensitive to precision fluctuations caused by minor false alarms. In contrast, Fa offers a global measure of background suppression independent of target size, while Fa emphasizes object-level localization rather than pixel-level coverage, providing a more practical evaluation for early warning tasks. Therefore, the combination of Pd, Fa, and AUC offers a more practical and holistic evaluation of detection reliability. A concise overview of these metrics is presented below, while detailed calculation standards are documented in [20]

(1) Probability of Detection (Pd) [20]

The Probability of Detection (Pd) is used to measure the ability of an algorithm to correctly detect true targets, and is defined as:

where denotes the number of true targets correctly detected, and represents the total number of annotated ground-truth targets.

(2) False Alarm Rate (Fa) [20]:

where denotes the number of non-target pixels that are incorrectly detected as targets, and represents the total number of pixels in the entire image.

(3) Area Under Curve (AUC) [20]

The Area Under Curve (AUC) comprehensively reflects the detection performance by calculating the area under the Pd-Fa curve. A value closer to 1 indicates better detection effectiveness.

4.3. Implementation Details

All deep learning experiments were conducted on a unified computing platform to ensure the comparability of results. The experimental environment consisted of an Intel i7-9700K CPU and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU, using Python 3.9, PyTorch 2.2.1, and CUDA 11.8. During network training, the Adam optimizer [48] was employed for parameter updates, with a total of 30 training epochs. The initial learning rate was set to 0.001 and decayed by a factor of 0.5 after each epoch. Convolutional layer weights were initialized using the Kaiming method [49], while bias terms were randomly sampled from a uniform distribution. The input data consisted of consecutive 5-frame infrared image sequences. For original frames with a resolution smaller than 512 × 512, zero-padding was applied to the right and bottom sides until the target size was reached, thereby maintaining spatial alignment and avoiding information loss. For loss design, Soft-IoU [50] was adopted as the optimization objective to more accurately measure the overlap between predictions and ground-truth annotations, thereby enhancing the localization performance of small targets.

4.4. Comparison with State of the Art

To validate the effectiveness of SCMT-Net, we conducted comparative experiments against twelve representative infrared small target detection methods on the NUDT-MIRSDT dataset. These methods cover both traditional detection approaches and deep learning-based detection methods. In the comparative experiments, the experimental results for traditional detection approaches and a portion of the deep learning-based methods were cited from the existing literature [20,51], while results not available in the literature were obtained through re-implementation. All re-implemented models were executed using the default parameters from their publicly available codes. To ensure fairness, all comparisons are based on the identical dataset partition and evaluation metric definitions.

4.4.1. Quantitative Analysis

We conducted separate tests for the cases of SNR≤ 3 and SNR > 3, and the results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Performance comparison of different state-of-the-art methods on the NUDT MIRSDT dataset. The table reports detection probability Pd (×10−2), false alarm rate Fa (×10−5), and AUC. The best results are highlighted in red, while the second-best results are highlighted in blue. Upward arrows (↑) indicate higher values are better, while downward arrows (↓) indicate lower values are better.

As observed, traditional methods rely on handcrafted spatial features and can stably distinguish targets from the background under SNR > 3 conditions. However, their detection performance exhibits significant fluctuations in scenarios with complex background textures or considerable target shape variations. Under SNR ≤ 3 conditions, they struggle to reliably separate weak targets from clutter, generally resulting in low detection rates and high false alarm rates. Deep learning-based methods demonstrate superior feature representation and generally achieve higher AUC values, performing consistently under SNR > 3 conditions. In contrast, deep learning algorithms that incorporate temporal information from multiple frames achieve further improved performance: they effectively enhance the detection rate of weak targets and significantly suppress false alarms under SNR ≤ 3 conditions, delivering competitive results across both SNR regimes. In terms of efficiency, our method achieves 8.929 FPS, which is competitive with the multi-frame Res-DTUM at 7.147 FPS and reasonably close to the single-frame DNANet at 12.133 FPS. This demonstrates that while temporal modeling introduces additional computational overhead compared with single-frame approaches, our algorithm maintains a favorable balance between detection robustness and computational efficiency.

DeepPro exhibits outstanding performance on the SNR ≤ 3 subset, and SCMT-Net further improves Pd by 0.29% compared with DeepPro. Furthermore, it matches the optimal detection rate under SNR > 3 conditions and maintains favorable Fa and AUC levels. This indicates that the proposed spatio-temporal feature fusion strategy considerably enhances target responses for both weak and strong targets. It is worth noting that DeepPro by default uses 40 consecutive frames as input to strengthen temporal information integration, thereby gaining an advantage in false alarm control. SCMT-Net, on the other hand, achieves higher Pd even with shorter sequence lengths, though it is more sensitive to target-like background details, leading to a slightly higher Fa. This discrepancy stems partly from differences in input configuration and optimization objectives, which impose certain limitations on direct comparison. Nevertheless, the results still reflect SCMT-Net’s performance advantages under the current setup.

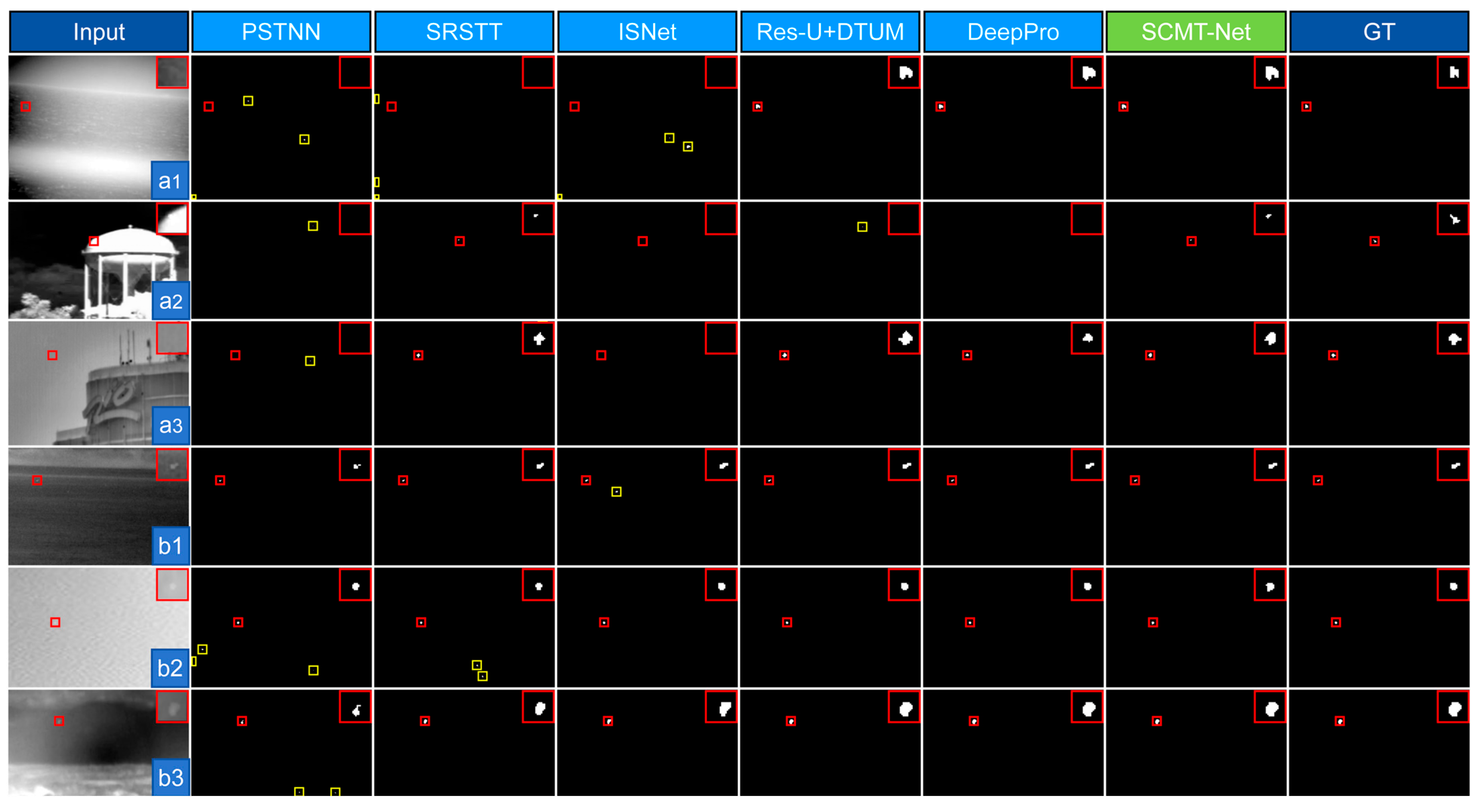

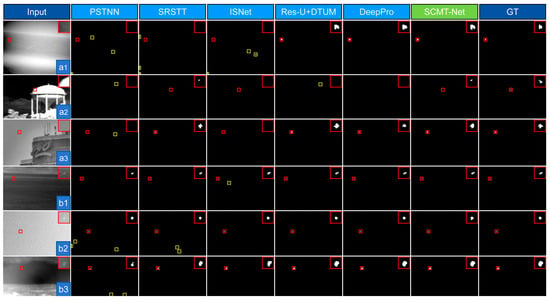

4.4.2. Qualitative Analysis

As illustrated in Figure 6, six representative sequences were selected from the SNR ≤ 3 subset and the entire NUDT-MIRSDT dataset to compare the output results of various detection methods. Among them, Figure 6(a1–a3) are drawn from the SNR ≤ 3 subset, while Figure 6(b1–b3) correspond to representative scenarios with SNR > 3.

Figure 6.

Visual comparison on the NUDT-MIRSDT dataset. Subfigures (a1–a3) show detection results on the NUDT-MIRSDT subset with SNR ≤ 3, while subfigures (b1–b3) present results on the subset with SNR > 3. For better visualization, the target regions are enlarged in the upper-right corner and highlighted with red bounding boxes, whereas false alarm regions are marked with yellow bounding boxes.

Under SNR ≤ 3 conditions, the target signal is extremely weak, making it nearly impossible to accurately localize the target in a single frame by visual inspection. Consequently, single-frame methods generally fail to provide reliable detection results, often suffering from missed detections or targets being overwhelmed by noise. For example, in SNR ≤ 3 scenarios, traditional single-frame methods produce almost no effective responses, while deep learning-based single-frame methods may generate detections in certain regions but with significant noise and blurred target contours. Some multi-frame methods (e.g., SRSTT [54], ResUNet + DTUM [20]) leverage temporal saliency to capture partial targets, yet their detection accuracy remains insufficient. In contrast, SCMT-Net not only maintains a high detection probability in these extremely weak target scenarios but also effectively suppresses background clutter, producing detection results that are more concentrated at the target location with clearer contours, thereby stably separating targets from the background.

Under SNR > 3 conditions, targets are easier to distinguish, and most methods perform better than in the SNR ≤ 3 scenarios. However, in complex background structures (e.g., scenes b2 and b3), traditional methods and deep learning-based single-frame methods are still prone to false alarms, especially when background textures resemble target features. Multi-frame methods perform relatively more robustly in such scenarios by exploiting cross-frame information to suppress part of the false alarms. In these scenarios, SCMT-Net not only achieves a detection probability that is comparable to, or surpasses, that of leading multi-frame approaches, but also significantly reduces the incidence of false alarms. This results in cleaner output representations and more precise delineation of target boundaries. These results clearly demonstrate that SCMT-Net can efficiently fuse spatial and temporal information under different SNR conditions, enhancing the response of weak or blurred targets while suppressing interference from complex backgrounds.

4.5. Ablation Study

4.5.1. Effectiveness Analysis of Each Module

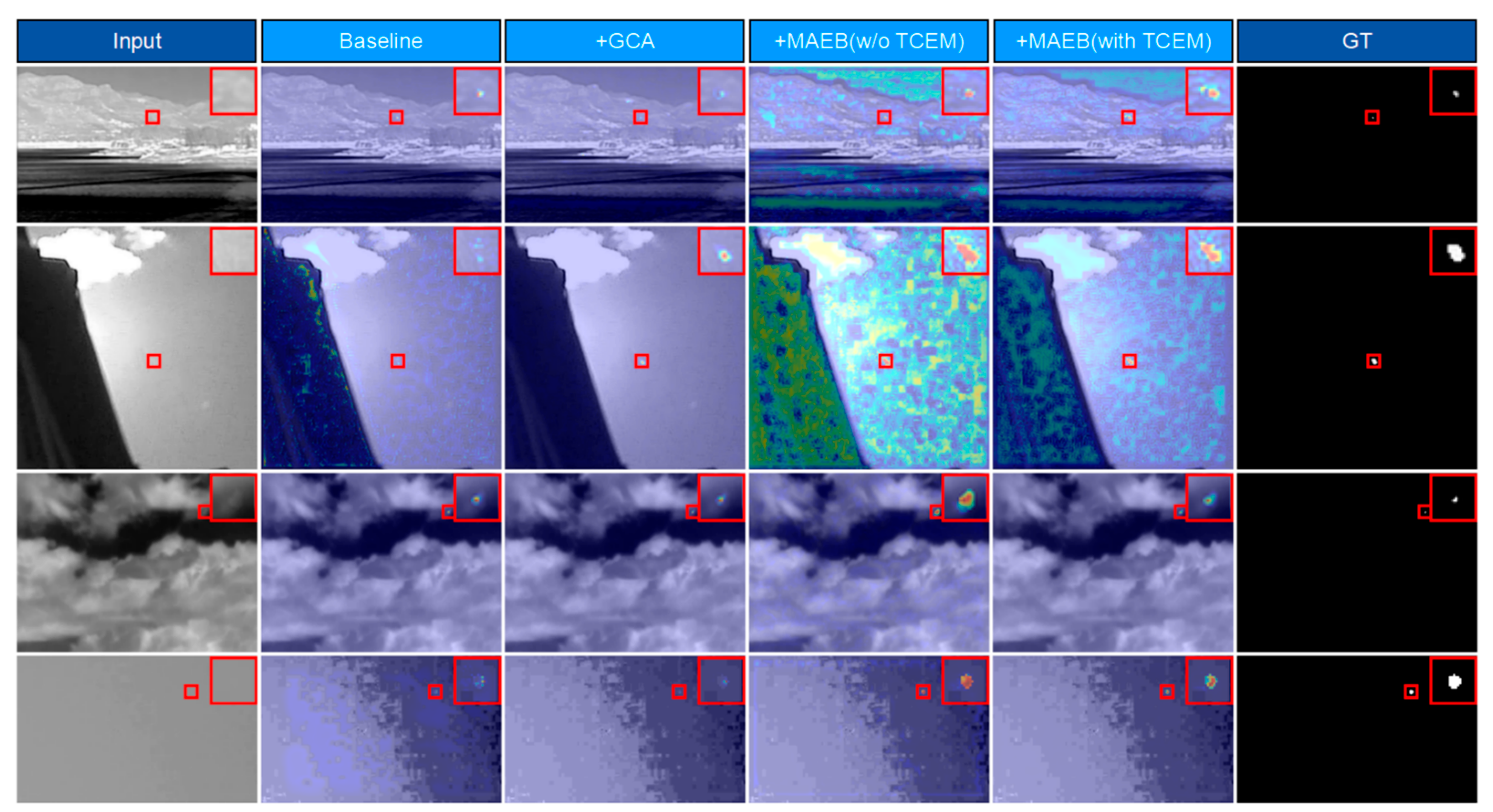

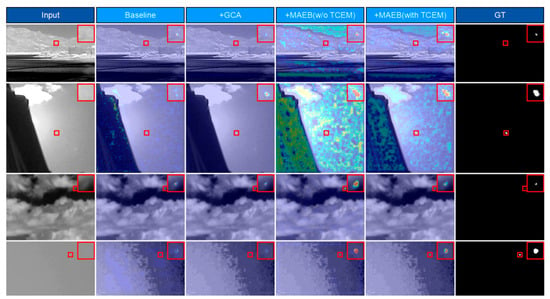

To systematically evaluate the independent contributions of each core module in the proposed method as well as their synergistic gains, we conducted an ablation study by constructing variant models. Specifically, we replaced the Gaussian Curvature Attention (GCA) module with a standard residual block, and substituted the proposed temporal decoding block with a baseline unit comprising Batch Normalization (BN), ReLU activation, and 3D Convolution. Crucially, the channel dimensions were strictly aligned across all variants to ensure structural consistency under a unified network and training configuration. Rigorous comparisons were then performed on the same dataset, with the specific combinations and corresponding metrics summarized in Table 2 and Figure 7. To provide a more intuitive visual comparison, Figure 7 presents the prediction heatmaps superimposed on the original images, where non-linear normalization is applied to distinctively demonstrate the network’s differential responses to targets and background clutter.

Table 2.

Effectiveness analysis of different module combinations on the NUDT MIRSDT dataset. The table reports detection probability Pd (×10−2), false alarm rate Fa (×10−5), and AUC. The best results in the table are highlighted in bold. Upward arrows (↑) indicate higher values are better, while downward arrows (↓) indicate lower values are better. the check mark (√) indicates that the corresponding module has been added.

Figure 7.

Comparative visualization of the SCMT-Net ablation study. The first column shows the input image. The middle four columns display the prediction heatmaps fused with original images, corresponding to the baseline model, the model with GCA, the model with MAEB (w/o TCEM), and the full MAEB (w/ TCEM), respectively. The final column displays the ground truth. The red frame marks the target to be enlarged.

As shown in the results, the baseline model without GCA spatial attention and temporal consistency modeling is clearly insufficient in target response. Introducing spatial attention significantly enhances the geometric saliency of weak targets, thereby directly improving the probability of detection, particularly for targets with low contrast. However, the sustained response to extremely weak targets remains unstable. Incorporating temporal consistency modeling alone (i.e., MAEB without TCEM) enhances target visibility and continuity across frames; nevertheless, in the absence of explicit spatial guidance and trajectory constraints, the attention focus is easily distracted by background structures, leading to simultaneous increases in both detection rate and false alarms.

When MAEB is integrated with TCEM, the temporal domain modeling of dynamic features becomes more selective, effectively improving detection probability in low-SNR regions while suppressing pseudo-motion consistency. This results in notable improvements in both AUC and sensitivity at low false alarm rates. Furthermore, the joint incorporation of spatial attention and temporal consistency yields cumulative synergistic benefits: the spatial domain provides precise target localization and interference suppression, while the temporal domain ensures cross-frame stability and weak-signal accumulation. Ultimately, this optimal configuration achieves the best overall performance across Pd, Fa, and AUC, and consistently outperforms all other combinations in multiple independent runs.

As evidenced in Table 2, the synergistic integration of the GCA module and the complete MAEB architecture (incorporating TCEM) yields optimal performance, demonstrating high stability across both the low-SNR subset (SNR ≤ 3) and the entire dataset. Particularly under low-SNR conditions, this configuration achieves a Pd of 96.13% while maintaining an extremely low Fa of 2.33 × 10−5, surpassing the performance of single-module baselines or incomplete ablation variants.

4.5.2. Effectiveness Analysis of MotionPool3d

Using MAEB without TCEM as the baseline network, we replaced the proposed MotionPool3d with common downsampling methods, namely AvgPool3d [47] and MaxPool3d [47], for comparative experiments. The results, as summarized in Table 3, show that under low-SNR conditions, MotionPool3d achieves superior performance compared with AvgPool3d and MaxPool3d: it yields higher detection probability, lower false alarm rate, and consistently better AUC, demonstrating stronger robustness against weak targets and complex backgrounds. Under high-SNR conditions, the overall performance gap narrows; however, MotionPool3d still maintains advantages across all three metrics (Pd, Fa, and AUC), reflecting more stable detection capability.

Table 3.

Analysis results of different pooling strategies on the NUDT MIRSDT dataset. The table reports detection probability Pd (×10−2), false alarm rate Fa (×10−5), and AUC. The best results in the table are highlighted in bold. Upward arrows (↑) indicate higher values are better, while downward arrows (↓) indicate lower values are better.

AvgPool3d tends to excessively smooth features, thereby weakening weak targets, while MaxPool3d is prone to amplifying instantaneous noise. In contrast, MotionPool3d leverages inter-frame difference information to select more discriminative responses within local windows, effectively suppressing interference from pseudo-salient regions while preserving temporally stable target features. Overall, MotionPool3d delivers particularly significant improvements under low-SNR conditions and maintains stable gains under high-SNR conditions, validating the effectiveness and generality of motion-driven pooling in temporal modeling.

4.5.3. Impact of Different Loss Functions

To verify the effectiveness of the adopted Soft-IoU [50] Loss, we conducted comparative experiments using Focal [56] Loss and BCE + IoU [57] Loss under identical experimental settings, with the results summarized in Table 4. As observed, in the high-SNR subset (SNR > 3), both Soft-IoU and BCE + IoU strategies achieve a 100% detection rate, while Focal Loss follows closely with 99.75%. This indicates that for distinct targets, the choice of loss function has a marginal impact on performance.

Table 4.

Analysis results of different Loss Functions on the NUDT MIRSDT dataset. The table reports detection probability Pd (×10−2), false alarm rate Fa (×10−5), and AUC. The best results in the table are highlighted in bold. Upward arrows (↑) indicate higher values are better, while downward arrows (↓) indicate lower values are better.

However, performance diverges significantly under low-SNR conditions (SNR ≤ 3). Focal Loss yields the lowest detection rate (89.13%) with a moderate false alarm rate (0.91 × 10−5), suggesting that its focusing mechanism may struggle to capture extremely weak targets dominated by noise. BCE + IoU Loss achieves the lowest false alarm rate (0.38 × 10−5) and a competitive detection rate of 95.03%, demonstrating strong background suppression capabilities but missing slightly more targets than the proposed method. In contrast, Soft-IoU Loss achieves the highest detection rate (96.13%) and the best AUC (0.9965). Although it exhibits a slightly higher false alarm rate (2.33 × 10−5) compared to the other methods, this represents a strategic trade-off: Soft-IoU provides the best gradient stability and sensitivity for extremely weak targets. In infrared surveillance, maximizing the target discovery rate (Pd) is often prioritized, and Soft-IoU effectively limits the false alarm rate to an acceptable magnitude while ensuring the best overall performance.

4.5.4. Effectiveness Analysis of GCA Modules

In the ablation study of inserting GCA at different layers of the single-frame subnetwork, we constructed six configurations (1, 2, 3, 1 + 2, 2 + 3, and 1 + 2 + 3). Under identical training settings, their detection performance was compared to analyze the effect of GCA on features at different layers. The experimental results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Analysis results of different GCA insertion layer combinations on the NUDT MIRSDT dataset. The table reports detection probability Pd (×10−2), false alarm rate Fa (×10−5), and AUC. The best results in the table are highlighted in bold. Upward arrows (↑) indicate higher values are better, while downward arrows (↓) indicate lower values are better.

In the single-layer insertion setting, placing GCA at the first layer (shallow level) is easily affected by high-frequency noise and background textures. Without stable semantic priors, the attention tends to respond to pseudo-salient regions such as cloud edges or ocean waves, leading to an increase in Pd but accompanied by a noticeable rise in Fa. When inserted at the second layer, structural details and local context are better balanced, yielding more averaged performance; however, semantic discrimination for extremely weak targets remains insufficient, and the overall gain is limited. Inserting GCA only at the third (deepest) layer helps suppress background consistency, but due to the lower spatial resolution, it struggles to precisely focus on small targets and fine-grained edges, resulting in only marginal improvements in Pd.

For dual-layer combinations, 1 + 2 can partially suppress shallow noise while retaining details, but the lack of deep semantic constraints on attention leads to misfocusing in complex backgrounds. 2 + 3, on the other hand, benefits from stronger semantic priors, providing better background suppression and overall robustness; yet, the absence of shallow fine textures and edge guidance limits its responsiveness to small displacements and weak targets, reflected in lower detection probability compared with the optimal configuration and higher sensitivity to threshold variations.

Overall, the 1 + 2 + 3 hierarchical combination proves to be the most effective: shallow layers provide details and edges to guide pixel-level attention placement; middle layers capture local structures and regional context to stabilize cross-frame correlations; and deep layers contribute global semantics and background priors to suppress pseudo-saliency and clutter. Consequently, under low-SNR and complex background conditions, this configuration achieves higher Pd, lower Fa, and more stable AUC. These results indicate that the full-layer collaboration of GCA forms a complementary chain of “detail–structure–semantics,” which significantly outperforms any single-layer or dual-layer combination.

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed Gaussian Curvature Attention (GCA) module for capturing weak target features, we compared it with two classic attention mechanisms, SE [58] and CBAM [59], under identical experimental settings. Results are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Analysis results of different Attention Modules on the NUDT MIRSDT dataset. The table reports detection probability Pd (×10−2), false alarm rate Fa (×10−5), and AUC. The best results in the table are highlighted in bold. Upward arrows (↑) indicate higher values are better, while downward arrows (↓) indicate lower values are better.

In the high-SNR subset, all three attention modules perform excellently and comparably, with detection probabilities approaching 100%, indicating that standard channel or spatial attention is sufficient for targets with clear features.

Under low-SNR conditions, however, differences become pronounced. SE, which models only channel-wise dependencies, shows the weakest detection performance because it fails to capture subtle spatial structural cues. CBAM adds a spatial attention branch but still relies on global pooling operations that limit its ability to describe the fine geometric characteristics of infrared small targets, yielding only modest gains over SE.

By contrast, GCA achieves the highest detection rate and AUC in the low-SNR regime. By exploiting local curvature information instead of simple intensity pooling, GCA increases sensitivity to dim, point-like targets. This improved sensitivity results in a slightly higher false alarm rate compared with the more conservative baselines, but GCA delivers the best overall stability and is most effective at reducing missed detections in extremely noisy environments.

4.5.5. Analysis of MAEB Insertion Layers

To determine the optimal insertion-layer combination of the MAEB module within the multi-frame subnetwork, we designed six configuration schemes by inserting MAEB into different feature layers. Under identical training settings, their detection performance was compared to analyze the effect of MAEB at different feature layers. The experimental results are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Analysis results of different MAEB insertion layer combinations on the NUDT MIRSDT dataset. The table reports detection probability Pd (×10−2), false alarm rate Fa (×10−5), and AUC. The best results in the table are highlighted in bold. Upward arrows (↑) indicate higher values are better, while downward arrows (↓) indicate lower values are better.

In the ablation study of inserting MAEB at different layers, it can be observed that features at different layers have a significant impact on performance. At the shallow layer (1st layer), although the richest details are preserved, the module is heavily affected by noise and texture interference, resulting in a noticeably higher false alarm rate. Inserting MAEB only at the 2nd or 3rd layer achieves a certain balance between detail and semantics, but the lack of complementarity limits its ability to capture weak targets and fine-grained structures. At the deepest layer (4th layer), stronger semantic priors help suppress background interference; however, due to the lowest spatial resolution, the enhancement of small targets remains insufficient.

Dual-layer combinations alleviate these issues to some extent. The 1 + 2 configuration suppresses part of the shallow noise while retaining details, but lacks deep semantic constraints. The 2 + 3 configuration is more robust in balancing semantics and structure, yet its response to extremely weak targets is still inferior to the optimal scheme. The 3 + 4 configuration compensates for the shortcomings of the 4th layer by introducing details from the 3rd layer, but without the bridging role of the 2nd layer, its overall stability is slightly weaker. The full-layer insertion (1 + 2 + 3 + 4), however, propagates shallow noise throughout the network, leading to an increased false alarm rate and over-suppression of certain targets.

Overall, deploying MAEB at the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th layers forms an effective complementarity among detail, structure, and semantics. This configuration avoids the amplification of shallow noise, preserves the bridging role of mid-layer features, and leverages the global priors of deep features, thereby achieving the highest Pd, lowest Fa, and best AUC under low-SNR and complex background conditions.

5. Discussion

Below, we briefly discuss the experimental findings and design choices. The two subnets of SCMT-Net complement each other across spatial and temporal dimensions: the single-frame subnet enhances spatial geometric saliency and local peak responses to provide stable, discriminative spatial features, while the multi-frame subnet focuses on extracting motion differences and accumulating temporal consistency to strengthen cross-frame target responses and suppress inconsistent background noise. GCA can enhance target intensity by leveraging curvature information. MotionPool3d effectively extracts motion features and preserves temporally stable target responses, and TCEM applies cross-frame constraints to retain target information while suppressing instantaneous noise. Overall, these design choices enable clearer separation of targets from clutter under low-SNR and complex backgrounds and maintain a favorable accuracy–efficiency balance with relatively short input sequences.

Some limitations remain: GCA and MotionPool3d can sometimes amplify background noise or pseudo-salient structures; the fixed temporal window and local association strategy are less adaptive for high-velocity or large-displacement targets, potentially degrading trajectory continuity; and the added temporal modeling increases computational cost, which requires further optimization for real-time or resource-constrained deployments. Future work should explore adaptive temporal windows and more robust cross-frame association mechanisms to improve generalization and practicality.

6. Conclusions

This paper addresses the challenge of achieving accurate infrared small target detection under complex backgrounds by proposing a detection network that integrates spatial attention with temporal consistency modeling. A GCA module is designed to enhance target focusing in the spatial domain, while an MAEB module equipped with TCEM is constructed to strengthen cross-frame consistency and weak target responses in the temporal domain. Through studies of different experiments, we analyzed the algorithm’s effectiveness and the individual contributions and synergistic gains of each module. The results demonstrate that SCMT-Net achieves significant improvements across all evaluation metrics, particularly under low-SNR conditions, and maintains stable performance across diverse scenarios. Overall, the proposed method exhibits superior detection performance under challenging conditions such as low SNR and complex backgrounds, providing an efficient and generalizable solution for infrared small target detection tasks.

Author Contributions

Methodology, R.Y., Y.L., and M.Z.; Software, R.Y. and Y.Y.; Writing—original draft, R.Y., Y.L., and H.Z.; Writing—review and editing, M.Z., Y.L., and Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key Laboratory of Space Target Awareness.

Data Availability Statement

The data utilized in this study are the publicly available NUDT-MIRSDT dataset. The dataset, along with access instructions, can be found at: https://github.com/TinaLRJ/Multi-frame-infrared-small-target-detection-DTUM. For a detailed description of the dataset, please refer to the original publication: DOI: 10.1109/TNNLS.2023.3331004. Accessed on 20 November 2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhao, M.; Li, W.; Li, L.; Hu, J.; Ma, P.; Tao, R. Single-Frame Infrared Small-Target Detection: A Survey. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2022, 10, 87–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teutsch, M.; Krüger, W. Classification of Small Boats in Infrared Images for Maritime Surveillance. In Proceedings of the 2010 International WaterSide Security Conference, Carrara, Italy, 3–5 November 2010; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, R.; Wang, C.; Peng, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Han, J.; Huang, F.; Yu, Y.; Fu, Q. Infrared small target segmentation networks: A survey. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 143, 109788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Sun, X.; Liu, M.; Ye, C.; Zhou, X. Small Infrared Target Detection Based on Weighted Local Difference Measure. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 54, 4204–4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xiao, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Li, M.; An, W.; Guo, Y. Dense Nested Attention Network for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 32, 1745–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Peng, L.; Zhang, T.; Cao, S.; Peng, Z. Infrared Small Target Detection via Non-Convex Rank Approximation Minimization Joint l2,1 Norm. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, B.; Fan, F.; Liang, K.; Fang, Y. A Robust Infrared Small Target Detection Algorithm Based on Human Visual System. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2014, 11, 2168–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, S.D.; Er, M.H.; Venkateswarlu, R.; Chan, P. Max-Mean and Max-Median Filters for Detection of Small Targets. In Signal and Data Processing of Small Targets 1999; SPIE: Orlando, FL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rivest, J.-F.; Fortin, R. Detection of Dim Targets in Digital Infrared Imagery by Morphological Image Processing. Opt. Eng. 1996, 35, 1886–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Meng, D.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Hauptmann, A.G. Infrared Patch-Image Model for Small Target Detection in a Single Image. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2013, 22, 4996–5009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Wu, Y. Reweighted Infrared Patch-Tensor Model with Both Nonlocal and Local Priors for Single-Frame Small Target Detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2017, 10, 3752–3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Xiang, S.; Ye, J. Robust Principal Component Analysis via Capped Norms. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD ‘13), Chicago, IL, USA, 11–14 August 2013; pp. 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, J.; An, Q. Small Infrared Target Detection Based on Low-Rank and Sparse Representation. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2015, 68, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Yang, Y.; Lee, J.; Park, Y. Small Target Detection Utilizing Robust Methods of the Human Visual System for IRST. J. Infrared Millim. Terahertz Waves 2009, 30, 994–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Barnard, K. Asymmetric Contextual Modulation for Infrared Small Target Detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 5–9 January 2021; pp. 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Hong, D.; Chanussot, J. UIU-Net: U-Net in U-Net for Infrared Small Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 32, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zhang, H.; Huang, K.; Zhu, X.; Arun, P.V.; Jiang, W.; Li, S.; Pei, X.; Zhou, H. SASU-Net: Hyperspectral Video Tracker based on Spectral Adaptive Aggregation Weighting and Scale Updating. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 272, 126721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhao, D.; Wang, C.; Yu, X.; Arun, P.V.; Asano, Y.; Xiang, P.; Zhou, H. Hyperspectral Video Object Tracking with Cross-Modal Spectral Complementary and Memory Prompt Network. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 330, 114595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Wang, M.; Huang, K.; Zhong, W.; Arun, P.V.; Li, Y.; Asano, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhou, H. OCSCNet-Tracker: Hyperspectral Video Tracker based on Octave Convolution and Spatial-Spectral Capsule Network. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; An, W.; Xiao, C.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Guo, Y. Direction-Coded Temporal U-Shape Module for Multiframe Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 555–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhang, T.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ji, R.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, X. Low-Level Matters: An Efficient Hybrid Architecture for Robust Multiframe Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 23757–23766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ouyang, Y.; Gao, F.; Guo, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J. MOCID: Motion Context and Displacement Information Learning for Moving Infrared Small Target Detection. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2025, 39, 10022–10030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Ji, L.; Zhu, J.; Ye, M.; Yao, X. SSTNet: Sliced Spatio-Temporal Network with Cross-Slice ConvLSTM for Moving Infrared Dim-Small Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5000912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Lian, S.; Luo, Z.; Li, S. Weighted Res-UNet for High-Quality Retina Vessel Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Information Technology in Medicine and Education (ITME), Hangzhou, China, 13–15 October 2018; pp. 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Moradi, S.; Faramarzi, I.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, N. Infrared Small Target Detection Based on the Weighted Strengthened Local Contrast Measure. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 18, 1670–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Peng, X.; Bai, Y.; Zheng, S. An Improved TLLCM Infrared Small Target Detection Method Based on Difference of Gaussians. In Proceedings of the 44th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Chongqing, China, 9–11 July 2025; pp. 7552–7557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, R.; Zheng, B.; Wang, H.; Fu, Y. Infrared Small Target Detection with Scale and Location Sensitivity. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 17490–17499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yue, K.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Gao, X. Exploring Feature Compensation and Cross-Level Correlation for Infrared Small Target Detection. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia (MM ‘22), Lisbon, Portugal, 10–14 October 2022; pp. 1857–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wu, T.; Lin, Z.; Li, M.; An, W.; Guo, Y. Mixed-Precision Network Quantization for Infrared Small Target Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5000812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, H.; Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhang, J. IRPruneDet: Efficient Infrared Small Target Detection via Wavelet Structure-Regularized Soft Channel Pruning. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2024, 38, 7224–7232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, H.; Hu, B.; Huang, K.; Arun, P.V.; Jia, X.; Zhao, D.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, H.; Yang, S. DSP-Net: A Dynamic Spectral–Spatial Joint Perception Network for Hyperspectral Target Tracking. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 5510905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zhong, W.; Ge, M.; Jiang, W.; Zhu, X.; Arun, P.V.; Zhou, H. SiamBSI: Hyperspectral Video Tracker based on Band Correlation Grouping and Spatial-Spectral Information Interaction. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2025, 151, 106063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Hu, B.; Jiang, W.; Zhong, W.; Arun, P.V.; Cheng, K.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, H. Hyperspectral Video Tracker based on Spectral Difference Matching Reduction and Deep Spectral Target Perception Features. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2025, 194, 109124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Liu, S.; Wang, H.; Tao, B.; Luo, J.; Peng, Z. Neural Spatial–Temporal Tensor Representation for Infrared Small Target Detection. Pattern Recognit. 2026, 169, 111929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Li, X.; He, L.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, G.; Tong, Y.; Ma, L.; Tao, D. TransVOD: End-to-End Video Object Detection with Spatial-Temporal Transformers. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 7853–7869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, D.; Xiang, Y.; Wang, H.; Ji, L.; Li, S.; Ye, M. Deformable Feature Alignment and Refinement for Moving Infrared Dim-Small Target Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.07289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Zuo, Z.; Su, S.; Wei, J.; Sun, X.; Wu, P.; Zhao, Z. ST-Trans: Spatial-Temporal Transformer for Infrared Small Target Detection in Sequential Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5001819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, X.; Liu, L.; Lin, Z.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Cao, X.; Li, B.; Zhou, S.; An, W. Infrared Small Target Detection in Satellite Videos: A New Dataset and a Novel Recurrent Feature Refinement Framework. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5002818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Yan, W.; You, M.; Zhang, J.; Arun, P.V.; Jiao, C.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, H. Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection based on Empirical Mode Decomposition and Local Weighted Contrast. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 33847–33861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zhang, H.; Arun, P.V.; Jiao, C.; Zhou, H.; Xiang, P.; Cheng, K. SiamSTU: Hyperspectral Video Tracker based on Spectral Spatial Angle Mapping Enhancement and State Aware Template Update. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2025, 150, 105919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Bai, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Wang, C.; Guo, J.; Gao, X. RKformer: Runge-Kutta Transformer with Random-Connection Attention for Infrared Small Target Detection. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia (MM ‘22), Lisbon, Portugal, 10–14 October 2022; pp. 1730–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, R.; Yang, Y.; Bai, H.; Zhang, J.; Guo, J. ISNet: Shape Matters for Infrared Small Target Detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Bai, J.; Yang, F.; Bai, X. Receptive-Field and Direction Induced Attention Network for Infrared Dim Small Target Detection with a Large-Scale Dataset IRDST. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5000513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yue, K.; Li, B.; Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Gao, X. Single-Frame Infrared Small Target Detection via Gaussian Curvature Inspired Network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5005013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, W.; Zhao, W.; Wang, W.; Xie, H.; Wang, F.L.; Wei, M. Lost in UNet: Improving Infrared Small Target Detection by Underappreciated Local Features. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5000115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioffe, S.; Szegedy, C. Batch Normalization: Accelerating Deep Network Training by Reducing Internal Covariate Shift. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML’15), Lille, France, 6–11 July 2015; pp. 448–456. [Google Scholar]

- Zafar, A.; Aamir, M.; Mohd Nawi, N.; Arshad, A.; Riaz, S.; Alruban, A.; Dutta, A.K.; Almotairi, S. A Comparison of Pooling Methods for Convolutional Neural Networks. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Delving Deep into Rectifiers: Surpassing Human-Level Performance on ImageNet Classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1026–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ning, X.; Blaschko, M.B. Jaccard Metric Losses: Optimizing the Jaccard Index with Soft Labels. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2302.05666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; An, W.; Ying, X.; Wang, Y.; Dai, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, M.; Guo, Y.; Liu, L. Probing Deep into Temporal Profile Makes the Infrared Small Target Detector Much Better. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.12766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, J.; An, W. Infrared Dim and Small Target Detection via Multiple Subspace Learning and Spatial-Temporal Patch-Tensor Model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 3737–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, S.; Xia, C.; Zhao, L. IMNN-LWEC: A Novel Infrared Small Target Detection Based on Spatial–Temporal Tensor Model. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5004022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z. Sparse Regularization-Based Spatial–Temporal Twist Tensor Model for Infrared Small Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5000417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Hou, R.; Duan, X.; Yue, C.; Wang, X.; Cao, X. STDMANet: Spatio-Temporal Differential Multiscale Attention Network for Small Moving Infrared Target Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5602516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Wang, Y. Optimizing Intersection-Over-Union in Deep Neural Networks for Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Visual Computing (ISVC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 12–14 December 2016; pp. 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.