HG-RSOVSSeg: Hierarchical Guidance Open-Vocabulary Semantic Segmentation Framework of High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images

Highlights

- We propose HG-RSOVSSeg, a novel, open-vocabulary framework that enables the segmentation of arbitrary land cover classes in high-resolution remote sensing images without model retraining.

- The introduced hierarchical guidance mechanism, which progressively aligns text and visual features, significantly outperforms state-of-the-art methods on six public benchmarks.

- Our framework provides a flexible and effective solution for segmenting arbitrary categories in remote sensing imagery, moving beyond the limitations of fixed-class segmentation models.

- The comprehensive evaluation of various Vision–Language Models for this task provides a valuable guideline and benchmark for future research in remote sensing OVSS.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A positional embedding adaptive (PEA) strategy is introduced, allowing the pre-trained model to freely adapt to inputs of different sizes while ensuring prediction accuracy.

- To bridge the semantic gap between text and image features, we develop a feature aggregation (FA) module that enables fine-grained alignment and interaction between pixel-level image and text embeddings, enhancing the model’s capacity to distinguish complex land cover categories.

- We design a hierarchical decoder (HD) guided by text feature alignment to densely integrate class label features into visual features, achieving high-resolution and fine-grained decoding through a hierarchical and progressive decoding process.

- The proposed framework was trained and tested on six representative datasets, and extensive experiments demonstrate that our framework significantly outperforms existing methods in OVSS, showing superior generalization to unseen classes.

2. Related Works

2.1. Pre-Training Vision–Language Models

2.2. Open-Vocabulary Semantic Segmentation

3. Methodology

3.1. Text Encoder

3.2. Adaptive Positional Embedding Image Encoder

| Algorithm 1: Positional embedding adaptive (PEA) strategy | |

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | ) |

| 5 | ) |

| 6 | ′) |

| 7 | ′) |

| 8 | |

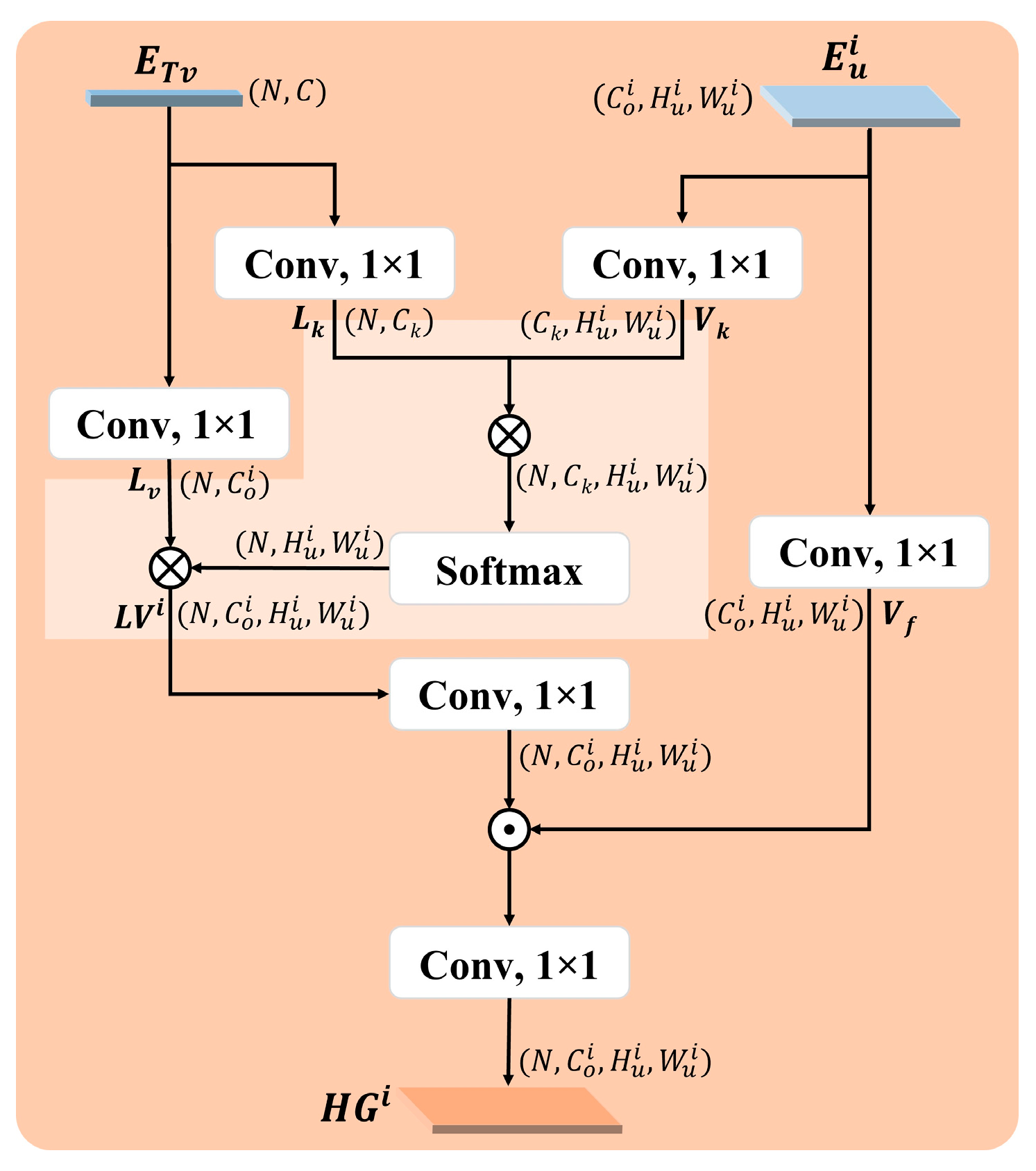

3.3. Feature Aggregation

3.4. Hierarchical Decoder

3.4.1. Text Attention Module

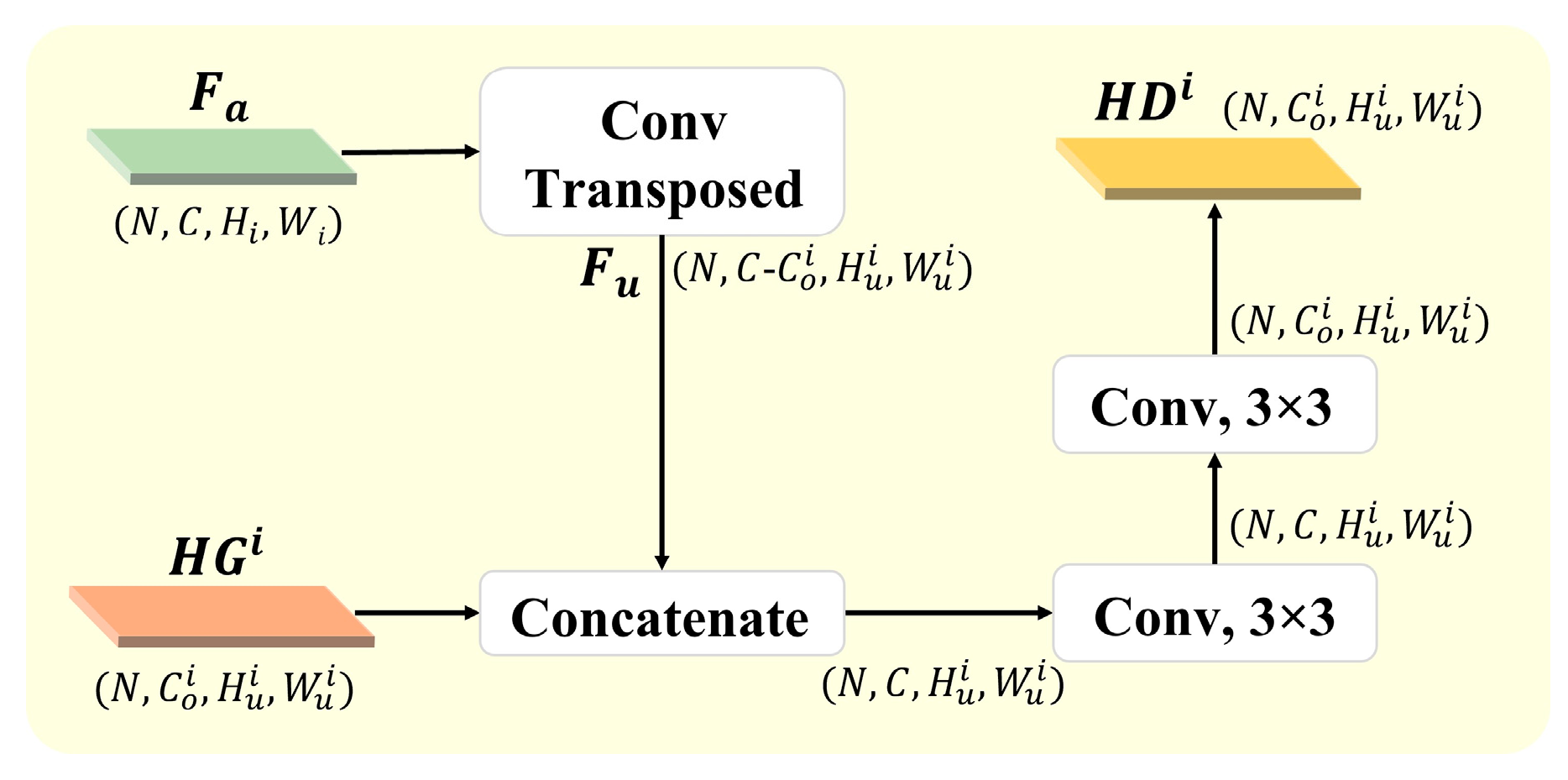

3.4.2. Hierarchical Guidance Upsampling Module

4. Experimental

4.1. Datasets

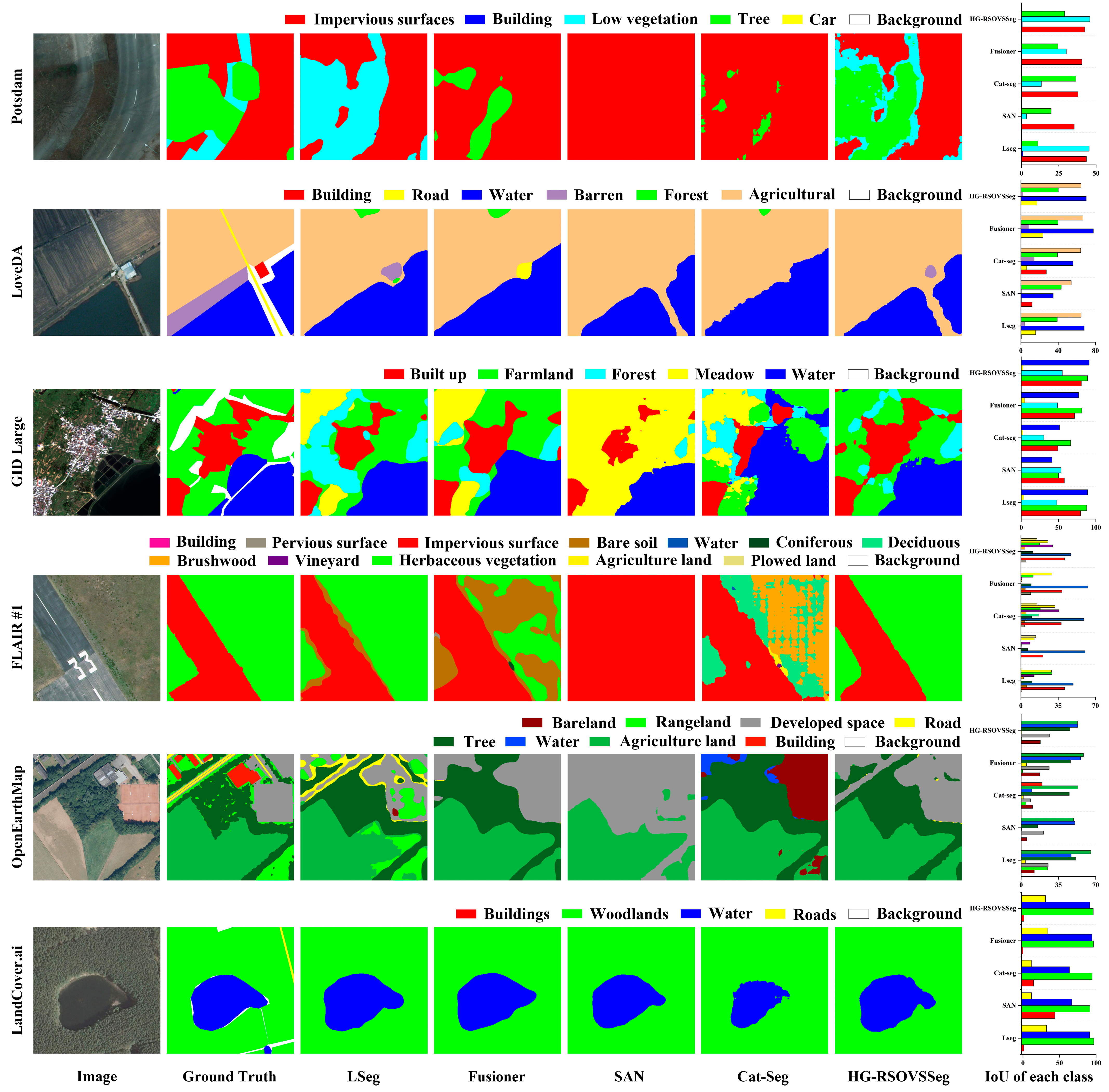

- (1)

- ISPRS Potsdam dataset (https://www.isprs.org/resources/datasets/benchmarks/UrbanSemLab/Default.aspx (accessed on 9 December 2024)): It is a typical historical city with large architectural complexes, narrow streets, and dense settlement structures. It consists of 38 remote sensing images with a spatial resolution of 0.05 m, each with a size of 6000 × 6000 pixels. These images were cropped into 512 × 512 patches with an overlap of 128 pixels. The dataset includes six classes: impervious surfaces, building, low vegetation, tree, car, and background. For training, we used images with IDs: 2_10, 2_11, 2_12, 3_10, 3_11, 3_12, 4_10, 4_11,4_12, 5_10, 5_11, 5_12, 6_10, 6_11, 6_12, 6_7,6_8, 6_9, 7_10, 7_11, 7_12, 7_7, 7_8, 7_9; the remaining 14 images were used for testing.

- (2)

- LoveDA dataset [54]: It is a land cover domain-adaptive semantic segmentation dataset that contains 5987 high-resolution images from three different cities and rural areas: Nanjing, Guangzhou, and Wuhan. It has multi-scale objects, complex backgrounds, and inconsistent class distributions. The images have a resolution of 0.3 m and are sized 1024 × 1024 pixels. During preprocessing, these images were cropped into non-overlapping patches of 512 × 512 pixels. The dataset contains seven classes: buildings, road, water, barren, forest, agriculture, and background. This dataset has default dataset splitting criteria.

- (3)

- GID Large dataset [55]: It is a large-scale land cover dataset constructed from Gaofen-2 satellite images, offering extensive geographic coverage and high spatial resolution. It consists of 150 images with a size of 7200 × 6800 pixels, which we cropped into non-overlapping patches of 512 × 512 pixels. The dataset includes six classes: built up, farmland, forest, meadow, water, and background. We selected 30 images for validation, and the remaining 120 images were used for training.

- (4)

- Globe230k dataset [56]: It is a large-scale global land cover-mapping dataset, which has three significant advantages: large scale, diversity, and multimodality. It contains 232,819 annotated images, each of size 512 × 512 pixels, with a spatial resolution of 1 m. The dataset comprises eleven classes: cropland, forest, grass, shrubland, wetland, water, tundra, impervious, bareland, ice, and background. This dataset has default dataset splitting criteria.

- (5)

- FLAIR #1 dataset [57]: It is a part of the dataset currently used at IGN to establish the French national land cover map reference, and includes 50 different spatial domains with high spatiotemporal heterogeneity. It consists of 77,412 remote sensing images with a spatial resolution of 0.2 m, all 512 × 512 pixels in size. The dataset contains thirteen classes of labels: building, pervious surface, impervious surface, bare soil, water, coniferous, deciduous, brushwood, vineyard, herbaceous vegetation, agricultural land, plowed land, and background. This dataset has default dataset splitting criteria.

- (6)

- OpenEarthMap dataset [58]: It is a global benchmark for high-resolution land cover mapping, including a mixed image set taken from different platforms. It covers 97 regions in 44 countries across 6 continents, with a spatial resolution ranging from 0.25 m to 0.5 m. During preprocessing, the images were cropped to 512 × 512 pixels. The dataset includes nine classes: bareland, rangeland, developed space, road, tree, water, agriculture land, building, and background. This dataset has default dataset splitting criteria.

- (7)

- LandCover.ai dataset [59]: It is an aerial image dataset covering 216.27 km2 of rural areas in Poland, with a spatial resolution ranging from 0.25 m to 0.5 m. During preprocessing, the images were cropped to 512 × 512 pixels. The dataset includes five classes: buildings, woodlands, water, roads, and background. This dataset has default dataset splitting criteria.

4.2. Implementation Details

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

4.4. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

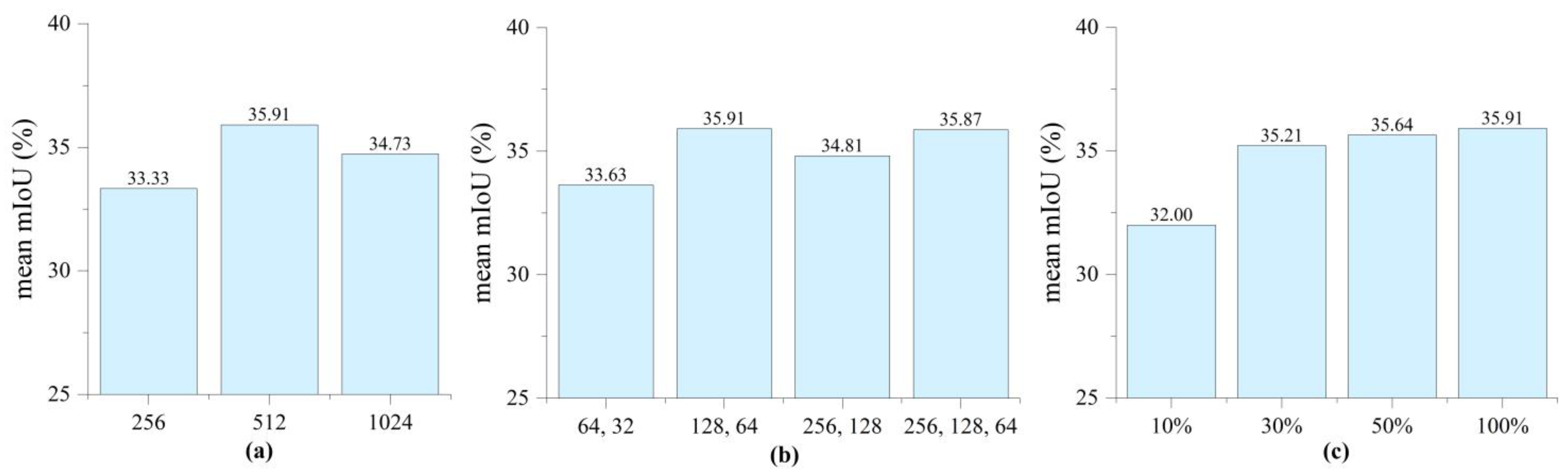

4.5. Parameter Analysis

4.5.1. Effect of Different in TAM

4.5.2. Effect of Different in HGU

4.5.3. Effect of Different Numbers of Training Samples

4.5.4. Effect of Different Templates in Text Encoder

4.6. Ablation Study

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison of the Different Pre-Trained VLMs and Frozen Stages

5.2. Influence of Different Training Datasets on Model Performance

5.3. Limitations and Future Works

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheng, J.; Deng, C.; Su, Y.; An, Z.; Wang, Q. Methods and datasets on semantic segmentation for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle remote sensing images: A review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 211, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, G.; Wang, W.; Wang, Q.; Dai, F. Object-Based Land-Cover Supervised Classification for Very-High-Resolution UAV Images Using Stacked Denoising Autoencoders. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2017, 10, 3373–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Lei, Y.; Sun, X.; Guan, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, D. Knowledge-guided land pattern depiction for urban land use mapping: A case study of Chinese cities. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 272, 112916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Ji, S. Graph Convolutional Networks for the Automated Production of Building Vector Maps From Aerial Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetang, C.; Xue, H.; Le, C.; Yue, T.; Wang, W.; He, Y. Segment Anything Model for Road Network Graph Extraction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 2556–2566. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Ding, M.; Huang, W.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, J.; Peng, J. A Generalized Deep Learning-based Method for Rapid Co-seismic Landslide Mapping. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 16970–16983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Ding, M.; Li, Z.; Yu, J.; Ge, D.; Liu, Q.; Yang, J. Landslide susceptibility mapping and dynamic response along the Sichuan-Tibet transportation corridor using deep learning algorithms. Catena 2023, 222, 106866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, C.; Duan, C.; Wang, L.; Atkinson, P.M. ABCNet: Attentive bilateral contextual network for efficient semantic segmentation of Fine-Resolution remotely sensed imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 181, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, R.; Zhang, C.; Fang, S.; Duan, C.; Meng, X.; Atkinson, P.M. UNetFormer: A UNet-like transformer for efficient semantic segmentation of remote sensing urban scene imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 190, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, X.; Pun, M.O. RS3Mamba: Visual State Space Model for Remote Sensing Image Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 6011405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, J. BFMNet: Bilateral feature fusion network with multi-scale context aggregation for real-time semantic segmentation. Neurocomputing 2023, 521, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Deng, F.; Liu, H.; Ding, M.; Yao, Q. Multiscale Semantic Segmentation of Remote Sensing Images Based on Edge Optimization. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5616813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Shao, X. A lightweight network for real-time smoke semantic segmentation based on dual paths. Neurocomputing 2022, 501, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shi, T.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Wang, Z.; Li, H. Learning deep semantic segmentation network under multiple weakly-supervised constraints for cross-domain remote sensing image semantic segmentation. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 175, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Ding, M.; Deng, F. Domain-Incremental Learning for Remote Sensing Semantic Segmentation With Multifeature Constraints in Graph Space. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5645215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourpanah, F.; Abdar, M.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, R.; Lim, C.P.; Wang, X.Z.; Wu, Q.M.J. A Review of Generalized Zero-Shot Learning Methods. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 4051–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ouyang, S.; Zhang, Y. Combining deep learning and ontology reasoning for remote sensing image semantic segmentation. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 243, 108469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, H.; Xia, X.; Wang, L.; Sun, J. Semantic-Embedded Knowledge Acquisition and Reasoning for Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 8–11 October 2023; pp. 2360–2364. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Li, Z.; Yang, X. Knowledge Reasoning for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Toronto, ON, Canada, 6–11 June 2021; pp. 2340–2344. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Kong, D.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, Y.; Chen, L. Robust deep alignment network with remote sensing knowledge graph for zero-shot and generalized zero-shot remote sensing image scene classification. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 179, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Geng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Pan, J.Z.; He, Y.; Zhang, W.; Horrocks, I.; Chen, H. Zero-Shot and Few-Shot Learning With Knowledge Graphs: A Comprehensive Survey. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 653–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Virtual Event, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wen, C.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, N. RS-CLIP: Zero shot remote sensing scene classification via contrastive vision-language supervision. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 124, 103497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Sun, Y.; Lei, L.; Kuang, G.; Ji, K. AdaptVFMs-RSCD: Advancing Remote Sensing Change Detection from binary to semantic with SAM and CLIP. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 230, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Shin, H.; Hong, S.; An, S.; Lee, S.; Arnab, A.; Seo, P.H.; Kim, S. CAT-Seg: Cost Aggregation for Open-Vocabulary Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 4113–4123. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Li, X.; Xu, S.; Yuan, H.; Ding, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Tong, Y.; Jiang, X.; et al. Towards Open Vocabulary Learning: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 5092–5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Li, L.; Yu, L.; El Kholy, A.; Ahmed, F.; Gan, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, J. Uniter: Universal image-text representation learning. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 104–120. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.H.; Yatskar, M.; Yin, D.; Hsieh, C.-J.; Chang, K.-W. Visualbert: A simple and performant baseline for vision and language. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.03557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Bansal, M. LXMERT: Learning cross-modality encoder representations from transformers. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), Hong Kong, 3–7 November 2019; pp. 5100–5111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Yang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Chen, Y.-T.; Parekh, Z.; Pham, H.; Le, Q.; Sung, Y.-H.; Li, Z.; Duerig, T. Scaling Up Visual and Vision-Language Representation Learning with Noisy Text Supervision. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Virtual Event, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 4904–4916. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Selvaraju, R.; Gotmare, A.; Joty, S.; Xiong, C.; Hoi, S.C.H. Align before fuse: Vision and language representation learning with momentum distillation. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Virtual Event, 6–14 December 2021; pp. 9694–9705. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Xiong, C.; Hoi, S. Blip: Bootstrapping language-image pre-training for unified vision-language understanding and generation. In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–23 July 2022; pp. 12888–12900. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Chen, D.; Guan, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, J.; Ye, Q.; Fu, L.; Zhou, J. RemoteCLIP: A Vision Language Foundation Model for Remote Sensing. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5622216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, T.; Guo, Y.; Yin, J. RS5M and GeoRSCLIP: A Large-Scale Vision—Language Dataset and a Large Vision-Language Model for Remote Sensing. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5642123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Prabha, R.; Huang, T.; Wu, J.; Rajagopal, R. Skyscript: A large and semantically diverse vision-language dataset for remote sensing. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), Honolulu, HI, USA, 7–14 January 2024; pp. 5805–5813. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckreja, K.; Danish, M.S.; Naseer, M.; Das, A.; Khan, S.; Khan, F.S. GeoChat: Grounded Large Vision-Language Model for Remote Sensing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 27831–27840. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Pang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, L.; Dang, B.; Lao, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Tan, Y. Skysensegpt: A fine-grained instruction tuning dataset and model for remote sensing vision-language understanding. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.10100. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Cai, M.; Zhang, T.; Zhuang, Y.; Mao, X. EarthGPT: A Universal Multimodal Large Language Model for Multisensor Image Comprehension in Remote Sensing Domain. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5917820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhtar, D.; Li, Z.; Gu, F.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, P. LHRS-Bot: Empowering remote sensing with vgi-enhanced large multimodal language model. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Cham, Switzerland, 23–27 September 2024; pp. 440–457. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.; Chen, L. A Survey on Open-Vocabulary Detection and Segmentation: Past, Present, and Future. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 8954–8975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, F.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Bai, X. A Simple Baseline for Open-Vocabulary Semantic Segmentation with Pre-trained Vision-Language Model. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2022; pp. 736–753. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.; Xue, N.; Xia, G.-S.; Dai, D. Decoupling zero-shot semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–22 June 2022; pp. 11583–11592. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, F.; Wu, B.; Dai, X.; Li, K.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, P.; Vajda, P.; Marculescu, D. Open-vocabulary semantic segmentation with mask-adapted clip. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 19–25 June 2023; pp. 7061–7070. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Weinberger, K.Q.; Belongie, S.; Koltun, V.; Ranftl, R. Language-driven Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual Event, 25–29 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, W. Open-vocabulary semantic segmentation with frozen vision-language models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.15138. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, F.; Hu, H.; Bai, X. SAN: Side Adapter Network for Open-Vocabulary Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 15546–15561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Cao, J.; Xie, J.; Khan, F.S.; Pang, Y. SED: A simple encoder-decoder for open-vocabulary semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 3426–3436. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Bruzzone, L. Toward Open-World Semantic Segmentation of Remote Sensing Images. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Pasadena, CA, USA, 16–21 July 2023; pp. 5045–5048. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Liu, R.; Cao, X.; Meng, D.; Wang, Z. SegEarth-OV: Towards Traning-Free Open-Vocabulary Segmentation for Remote Sensing Images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 16–22 June 2025; pp. 10545–10556. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, C.; Zhuge, Y.; Zhang, P. Towards Open-Vocabulary Remote Sensing Image Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–11 February 2025; pp. 9436–9444. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Ma, C.; Yang, X. Open-Vocabulary High-Resolution Remote Sensing Image Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Li, H.; Zhang, S.; Deng, F. Reducing semantic ambiguity in open-vocabulary remote sensing image segmentation via knowledge graph-enhanced class representations. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2026, 231, 837–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Ma, A.; Lu, X.; Zhong, Y. LoveDA: A Remote Sensing Land-Cover Dataset for Domain Adaptive Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems Track on Datasets and Benchmarks (NeurIPS), Virtual Event, 6–12 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, X.-Y.; Xia, G.-S.; Lu, Q.; Shen, H.; Li, S.; You, S.; Zhang, L. Land-cover classification with high-resolution remote sensing images using transferable deep models. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 237, 111322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; He, D.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Xue, J. Globe230k: A Benchmark Dense-Pixel Annotation Dataset for Global Land Cover Mapping. J. Remote Sens. 2023, 3, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garioud, A.; Peillet, S.; Bookjans, E.; Giordano, S.; Wattrelos, B. FLAIR #1: Semantic segmentation and domain adaptation dataset. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.12979. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, J.; Yokoya, N.; Adriano, B.; Broni-Bediako, C. Openearthmap: A benchmark dataset for global high-resolution land cover mapping. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–7 January 2023; pp. 6254–6264. [Google Scholar]

- Boguszewski, A.; Batorski, D.; Ziemba-Jankowska, N.; Dziedzic, T.; Zambrzycka, A. LandCover. ai: Dataset for automatic mapping of buildings, woodlands, water and roads from aerial imagery. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Virtual Event, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 1102–1110. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, C.; Huang, J.; Zhang, L. TPOV-Seg: Textually Enhanced Prompt Tuning of Vision-Language Models for Open-Vocabulary Remote Sensing Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zermatten, V.; Castillo-Navarro, J.; Marcos, D.; Tuia, D. Learning transferable land cover semantics for open vocabulary interactions with remote sensing images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 220, 621–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | mean mIoU | FLOPs (T) | Params (G) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potsdam | LoveDA | GID Large | FLAIR #1 | OpenEarthMap | LandCover.ai | ||||

| LSeg | 20.18 | 31.99 | 61.50 | 15.09 | 28.72 | 55.33 | 35.47 | 1.246 | 0.551 |

| Fusioner | 19.05 | 36.11 | 56.49 | 13.91 | 26.35 | 56.20 | 34.69 | 1.078 | 0.462 |

| SAN | 11.72 | 24.16 | 40.60 | 10.24 | 17.74 | 53.43 | 26.32 | 1.066 | 0.436 |

| Cat-Seg | 17.59 | 34.48 | 39.81 | 19.77 | 19.28 | 46.05 | 29.50 | 1.022 | 0.433 |

| HG-RSOVSSeg (Ours) | 22.85 | 36.15 | 67.63 | 12.54 | 27.74 | 57.71 | 37.44 | 1.036 | 0.433 |

| Templates | Number | mean mIoU | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potsdam | LoveDA | GID Large | FLAIR #1 | OpenEarthMap | LandCover.ai | |||

| vild | 14 | 23.53 | 32.36 | 63.58 | 16.28 | 24.70 | 55.01 | 35.91 |

| imagenet_select_clip | 32 | 22.27 | 29.76 | 63.24 | 15.51 | 25.18 | 54.98 | 35.16 |

| imagenet | 80 | 24.02 | 34.23 | 65.06 | 14.98 | 23.34 | 53.97 | 35.93 |

| PEA | FA | HD | mean mIoU | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HGU | TAM | Potsdam | LoveDA | GID Large | FLAIR #1 | OpenEarthMap | LandCover.ai | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | 14.37 | 24.81 | 45.56 | 12.32 | 19.10 | 50.91 | 27.85 | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 15.50 | 33.53 | 55.85 | 14.11 | 25.18 | 56.67 | 33.47 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 23.53 | 32.36 | 63.58 | 16.28 | 24.70 | 55.01 | 35.91 |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 21.94 | 33.55 | 61.70 | 15.50 | 25.42 | 54.62 | 35.46 | |

| mean mIoU | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potsdam | LoveDA | GID Large | FLAIR #1 | OpenEarthMap | LandCover.ai | ||

| Similarity-based | 21.26 | 29.09 | 63.36 | 14.56 | 24.36 | 51.07 | 33.95 |

| Cost | 18.78 | 32.04 | 66.25 | 14.51 | 22.13 | 53.83 | 34.59 |

| Ours | 23.53 | 32.36 | 63.58 | 16.28 | 24.70 | 55.01 | 35.91 |

| Pre-Trained VLMs | Frozen Stages | mean mIoU | Globe230k | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image Encoder | Text Encoder | Potsdam | LoveDA | GID Large | FLAIR #1 | OpenEarthMap | LandCover.ai | |||

| CLIP ViT-L/14 | ✓ | ✓ | 23.53 | 32.36 | 63.58 | 16.28 | 24.70 | 55.01 | 35.91 | 68.31 |

| CLIP ViT-L/14 | ✓ | 19.63 | 33.13 | 66 | 14.07 | 26.01 | 55.2 | 35.67 | 74.95 | |

| CLIP ViT-L/14 | ✓ | 19.17 | 27.02 | 22.53 | 9.75 | 9.04 | 50.57 | 23.1 | 68.57 | |

| CLIP ViT-L/14 | 13.47 | 19.44 | 20.78 | 9.01 | 9.86 | 46.83 | 19.90 | 74.82 | ||

| CLIP ViT-B/16 | ✓ | ✓ | 17.09 | 30.86 | 60.95 | 14.57 | 19.31 | 46.62 | 31.57 | - |

| CLIP ViT-B/32 | ✓ | ✓ | 16.43 | 28.4 | 47.32 | 12.41 | 13.06 | 47.94 | 27.59 | |

| CLIP ViT-L/14@336 | ✓ | ✓ | 24.01 | 31.39 | 65.66 | 15.7 | 25.25 | 55.69 | 36.28 | |

| RemoteCLIP ViT-B/32 | ✓ | ✓ | 10.31 | 18.03 | 50.34 | 12.09 | 14.06 | 50.46 | 25.88 | |

| RemoteCLIP ViT-L/14 | ✓ | ✓ | 16.42 | 27.48 | 65.6 | 14.9 | 17.1 | 55.29 | 32.80 | |

| GeoRSCLIP ViT-B/32 | ✓ | ✓ | 20.01 | 31.87 | 44.24 | 12.82 | 12.79 | 52.01 | 28.96 | |

| GeoRSCLIP ViT- L/14 | ✓ | ✓ | 22.77 | 34.61 | 67.5 | 14.46 | 25.83 | 58.71 | 37.31 | |

| GeoRSCLIP ViT-L/14@336 | ✓ | ✓ | 22.85 | 36.15 | 67.63 | 12.54 | 27.74 | 57.71 | 37.44 | |

| SkyCLIP ViT- B/32 | ✓ | ✓ | 6.25 | 27.44 | 39.27 | 11.79 | 14.32 | 50.27 | 24.89 | |

| SkyCLIP ViT-L/14 | ✓ | ✓ | 25.63 | 31.05 | 62.03 | 14.96 | 24.08 | 55.74 | 35.58 | |

| Training Dataset | mean mIoU | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potsdam | LoveDA | GID Large | Globe230k | FLAIR #1 | OpenEarthMap | LandCover.ai | ||

| Potsdam | 80.78 | 9.27 | 10.99 | 7.85 | 14.41 | 18.23 | 33.31 | 15.68 |

| LoveDA | 10.18 | 64.56 | 51.98 | 18.63 | 14.37 | 28.41 | 72.72 | 32.72 |

| GID Large | 22.65 | 37.25 | 95.22 | 18.38 | 7.32 | 21.21 | 56.86 | 27.28 |

| Globe230k | 22.85 | 36.15 | 67.63 | 69.25 | 12.54 | 27.74 | 57.71 | 37.44 |

| FLAIR #1 | 41.83 | 43.14 | 37.25 | 23 | 59.82 | 25.36 | 75.8 | 41.06 |

| OpenEarthMap | 39.59 | 62.58 | 58.21 | 28.02 | 14.92 | 62.56 | 87.23 | 48.43 |

| LandCover.ai | 26.86 | 33.71 | 30.13 | 11.63 | 12.16 | 19.45 | 94.2 | 36.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, W.; Deng, F.; Li, H.; Yang, J. HG-RSOVSSeg: Hierarchical Guidance Open-Vocabulary Semantic Segmentation Framework of High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020213

Huang W, Deng F, Li H, Yang J. HG-RSOVSSeg: Hierarchical Guidance Open-Vocabulary Semantic Segmentation Framework of High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(2):213. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020213

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Wubiao, Fei Deng, Huchen Li, and Jing Yang. 2026. "HG-RSOVSSeg: Hierarchical Guidance Open-Vocabulary Semantic Segmentation Framework of High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images" Remote Sensing 18, no. 2: 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020213

APA StyleHuang, W., Deng, F., Li, H., & Yang, J. (2026). HG-RSOVSSeg: Hierarchical Guidance Open-Vocabulary Semantic Segmentation Framework of High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sensing, 18(2), 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020213