Highlights

What are the main findings?

- This review systematically summarizes the theoretical foundations of optical and synthetic aperture radar (SAR) imaging, clarifying their complementarity for remote-sensing image interpretation.

- It highlights the key role of optical and SAR data fusion (OPT-SAR fusion) while outlining the evolution of related methods, open data and code resources, and emerging development trends.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- This review enables readers to quickly and comprehensively grasp the current status of OPT-SAR fusion methods and their applications in relevant Earth observation missions from a technical perspective.

- By consolidating future research directions in OPT-SAR fusion, this review outlines a technical roadmap toward more reliable, generalizable, and practically deployable fusion systems.

Abstract

Remote sensing technology has become an indispensable core means for Earth observation. As two of the most commonly used remote sensing modalities, the fusion of optical and synthetic aperture radar (SAR) (OPT-SAR fusion) can effectively overcome the limitations of a single data source, achieve information complementarity and synergistic enhancement, thereby significantly improving the interpretation capability of multi-source remote sensing data. This paper first discusses the necessity of OPT-SAR fusion, systematically reviews the historical development of fusion technologies, and summarizes open-source resources for various tasks, aiming to provide a reference for related research. Finally, building upon recent advances in OPT-SAR fusion research and cutting-edge developments in deep learning, this paper proposes that future fusion technologies should develop in the following directions: interpretable fusion models driven by both data and knowledge, general fusion perception driven by multimodal large models, and lightweight architectures with efficient deployment strategies.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The rapid advancement of remote sensing technology has provided essential data support for critical domains, such as environmental monitoring [1], urban planning [2], disaster warning [3], and national defense security [4]. Different types of remote sensing sensors have their own advantages in terms of imaging resolution, spectral characteristics, or spatiotemporal coverage. However, due to limitations in imaging mechanisms and hardware conditions, single-modal sensors often suffer from inherent bottlenecks such as incomplete information and discontinuous observations, making it difficult to achieve a comprehensive representation of the scene and meet the needs of complex applications [5,6,7]. To overcome the bottlenecks above, multi-source fusion technology is essential for improving the efficiency of remote sensing information utilization and interpretation accuracy [8]. Currently, common multi-source remote sensing data fusion objects mainly include panchromatic and multispectral fusion [9], lidar and optical fusion [10], optical and thermal infrared fusion [11], and optical and synthetic aperture radar (SAR) fusion [12].

Among various multi-source remote sensing fusion objects, optical imagery and SAR imagery stand out due to their high complementarity in physical mechanisms and information dimensions [13]. The fundamental differences in imaging mechanisms lead to significant differences between optical and SAR images, as illustrated in Figure 1.

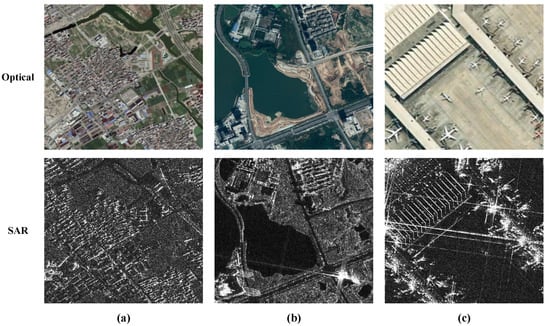

Figure 1.

Example of Optical and SAR Image Pairs. The images in (a,b) are obtained from the FUSAR-Map dataset [14]. The SAR image in (c) is obtained from the FAIR-CSAR dataset [15], and the corresponding optical image in (c) is sourced from Google Maps.

Optical remote sensing relies on sunlight and can provide rich spectral and textural details; however, its imaging quality is highly susceptible to atmospheric and lighting conditions [16]. In contrast, SAR, as an active microwave remote sensing system, can acquire data under various weather conditions, and its echo intensity is particularly sensitive to surface geometry and dielectric properties [17]. Nevertheless, SAR images are often affected by speckle noise and complex geometric distortions [18], and lack spectral information, making their visual interpretation much less intuitive than that of optical images. Consequently, the fusion of optical and SAR (OPT-SAR fusion) not only compensates for the observational limitations of a single data source under specific environmental conditions but also achieves information complementarity and feature enhancement in the feature space, thereby contributing to a more robust and comprehensive surface representation. It is widely used in downstream tasks such as land-cover classification [19], image translation [20], cloud removal [21], target detection [22], target recognition [23], change detection [24], and 3D reconstruction [25]. In addition, OPT-SAR fusion also has provided crucial support for ecological monitoring and climate change studies [26].

1.2. Motivation for This Survey

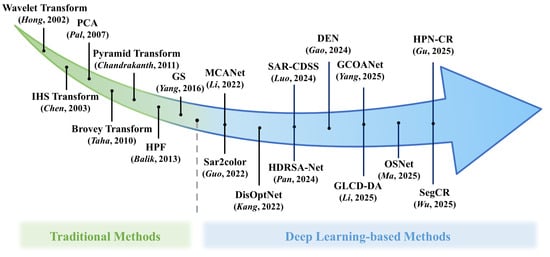

In recent years, data-driven deep network models, with their end-to-end cross-modal feature extraction and nonlinear mapping capabilities, have significantly advanced the development of fusion research [27]. In particular, the continuous evolution of deep-learning technologies [28,29,30,31,32,33], has ushered in a new wave of methodological innovation in OPT-SAR fusion research. The milestones in the development of OPT-SAR fusion technology are illustrated in Figure 2, chronicling the field’s progression from early traditional schemes to the contemporary dominance of deep learning frameworks.

Figure 2.

The milestones in the development of OPT-SAR fusion technology. (PCA [34], GS [35], IHS Transform [36], Brovey Transform [37], HPF [38], Pyramid Transform [39], Wavelet Transform [40], HPN-CR [41], DEN [42], OSNet [43], Sar2color [44], SegCR [45], SAR-CDSS [46], GLCD-DA [47], GCOANet [48], MCANet [49], HDRSA-Net [50], DisOptNet [51]).

Although several reviews on OPT-SAR fusion have been published, many were written years ago and primarily focus on traditional methodological paradigms that predate the rise of deep learning [52]. Some surveys still fail to comprehensively summarize the latest advances within the past years [53]. In addition, a few surveys expand their scope to multimodal remote sensing data fusion as a whole, yet lack an in-depth analysis dedicated to OPT-SAR fusion [54,55]. Meanwhile, several studies concentrate on a single downstream task of OPT-SAR fusion, such as target detection or change detection [56,57,58,59]. On this basis, this paper conducts a systematic review of OPT-SAR fusion, focusing on the following five key aspects:

- Theory-oriented: Elucidates the intrinsic complementarity between optical and SAR imaging, thereby underscoring the fundamental necessity for their integration.

- Systematicness: Systematically examines OPT-SAR fusion methods, spanning from traditional frameworks to deep learning paradigms.

- Comprehensiveness: Reviews the applications of OPT-SAR fusion across diverse downstream tasks, providing a holistic understanding of the field beyond single-task perspectives.

- Openness: Compiles open-source datasets and code repositories for OPT-SAR fusion to facilitate reproducible research and standardized benchmarking.

- Future-oriented: Identifies emerging research directions and future trends in OPT-SAR fusion through an analysis of its historical and technological evolution.

1.3. Scope and Organization

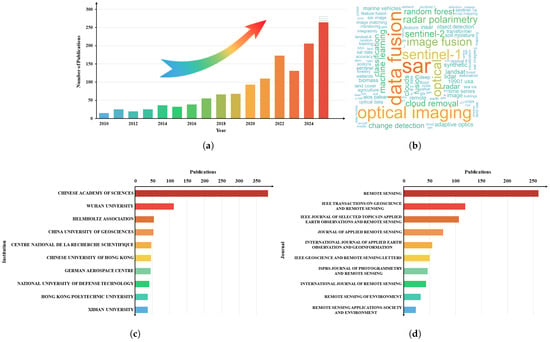

To systematically review the research progress in the field of OPT-SAR fusion, this paper conducts a literature search based on the Web of Science database. The search strategy was “(Optical OR “Optical imagery” OR “Optical image”) AND (SAR OR “Synthetic Aperture Radar”) AND (Fusion OR Integration OR “Joint interpretation”)”, the document type was “Academic Journal Article”, and the time range was limited to 2010 to 2025 (up to October 2025). After format standardization and deduplication, a total of 1361 valid documents were obtained. Detailed information about the search results is shown in Figure 3. As shown in Figure 3a, the sharp increase in the number of publications highlights the growing importance of and expanding research interest in this field.

Figure 3.

The collected publications by (a) Year, (b) Cloud map of high-frequency keywords, (c) Institution, (d) Journal.

Given that OPT-SAR fusion studies shown in Figure 3 are quite extensive, it is impractical to provide an exhaustive overview within a single article. Therefore, this paper mainly focuses on the following aspects:

(i) Literature sources: Peer-reviewed papers published in high-impact international journals and top academic conferences, as well as representative research that has pioneering significance in the field of remote sensing;

(ii) Time span: Tracing the evolution of OPT-SAR fusion technology through its journey from early traditional methodologies to the current mainstream adoption of deep learning technology;

(iii) Scope of tasks: Primarily targeting OPT-SAR fusion methods and their application in various scenarios.

For the topic of OPT-SAR registration, this paper identifies it as an independent research direction for future work.

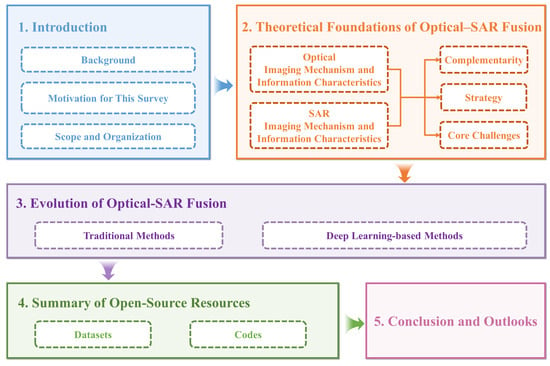

The remainder of this article is organized as follows, and the overall framework is illustrated in Figure 4. Section 2 outlines the theoretical foundation of OPT-SAR fusion, analyzes their complementarity from the perspectives of imaging mechanisms and information characteristics, and summarizes typical fusion strategies and core challenges. In Section 3, the history of OPT-SAR fusion methods is reviewed. Section 4 provides a comprehensive review of open-source resources in the field of OPT-SAR fusion from the perspective of downstream applications. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the entire paper and explores possible future research directions.

Figure 4.

The overall framework of this review.

2. Theoretical Foundations of OPT-SAR Fusion

2.1. Optical Imaging Mechanism and Information Characteristics

Optical remote sensing is a typical passive imaging technique that relies on external illumination sources, primarily solar radiation. When sunlight reaches the Earth’s surface, ground objects with distinct spectral properties reflect, absorb, and transmit the radiation to varying degrees. Then, the electromagnetic signals reflected from ground objects are captured and quantized by optical sensors. Afterward, a detector array converts them into digital signals to form multidimensional imagery encompassing spatial, spectral, and radiometric information [16].

Optical remote sensing sensors span the visible, near-infrared, short-wave infrared, and thermal infrared regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. Among these, the visible band captures the color of ground objects, closely resembling human visual perception [60]. The near-infrared band is highly sensitive to vegetation parameters such as vigor, chlorophyll content, and water content, making it particularly suitable for ecological vegetation monitoring [61]. In contrast, the thermal infrared band directly reflects the temperature distribution and radiation energy characteristics of the Earth’s surface [62]. As a result, optical provides information on both spatial structure and spectral characteristics, offering both high interpretability and strong discriminative capacity for surface features. In recent years, optical remote sensing satellites have experienced explosive growth globally, with countries successively launching a new generation of observation platforms with higher spatial resolution, stronger imaging capabilities, and higher revisit frequencies. Table 1 summarizes some representative optical remote sensing satellites.

Table 1.

Representative optical remote sensing satellites.

Based on the number of spectral bands, optical images are typically classified into panchromatic (PAN), multispectral (MS), and hyperspectral (HS) imagery. PAN imagery, displayed in grayscale, offers the highest spatial resolution, making it well-suited for characterizing geometric shapes and textural features of ground objects [63]. MS imagery collects radiance data across multiple bands spanning the visible to near-infrared regions, effectively balancing spatial detail with spectral information. This combination makes it particularly valuable for vegetation monitoring and land cover classification [64]. HS imagery acquires contiguous measurements across hundreds of narrow spectral bands, enabling precise classification and detailed analysis of material composition [65]. In practical applications, these three types of imagery are often integrated to produce data products that achieve both high spatial detail and rich spectral information [66,67].

Consequently, optical imagery, characterized by its high spatial resolution, rich spectral information, and intuitive visual representation, has played an irreplaceable role across a wide range of fields. However, optical imaging’s reliance on solar illumination and limited spectral penetration makes it highly susceptible to interference from atmospheric and environmental factors, which attenuate electromagnetic signals and severely compromise data quality, ultimately leading to information loss and observational unreliability.

2.2. SAR Imaging Mechanism and Information Characteristics

To overcome the shortcomings of optical imaging in terms of weather adaptability and penetration, SAR, as an active microwave imaging system, has shown significant advantages in all-weather observation capabilities. SAR imaging operates on the principles of Doppler frequency shift and coherent processing. By actively emitting electromagnetic waves and capturing the backscattered signals from terrain features, SAR systems eliminate the need for external illumination sources. Moreover, the microwave frequencies employed in SAR possess significant penetration capacity, allowing them to penetrate vegetation canopies, dry soil, and snow cover [68,69]. This capability renders SAR particularly valuable for applications including forest biomass estimation and subsurface target identification [70]. Table 2 summarizes some representative SAR remote sensing satellites. As shown in the table, SAR missions have experienced rapid global expansion. The listed satellites cover a wide range of frequency bands, including the commonly used C-, X-, and L-bands, enabling diverse imaging capabilities for different application scenarios.

Table 2.

Representative SAR remote sensing satellites.

The high-resolution imaging capability of SAR relies on two core mechanisms: the synthesis of a virtual long antenna through platform motion to enhance azimuth resolution, and the application of linear frequency modulated signals combined with pulse compression techniques to improve range resolution [17]. These mechanisms collectively enable SAR to overcome the resolution limitations of conventional real-aperture radar systems while delivering consistent high-resolution imagery under complex weather and lighting conditions. Beyond its stable imaging capabilities, SAR data contains rich and unique multidimensional information. The amplitude component captures structure-dependent variations of ground targets and reliably characterizes their backscattering signatures: smooth surfaces exhibit low backscatter due to specular reflection, rough surfaces produce stronger backscatter through diffuse scattering, and vertical structures generate extremely high backscatter as a result of the dihedral corner reflection effect [71]. The unique phase information is the core of interferometric SAR (InSAR) technology, which can be used to extract surface elevation and deformation information, playing an important role in geological disaster prevention and urban subsidence monitoring [72]. Furthermore, SAR polarization information provides an extra observational capability. Different polarization channels (HH, HV, VH, VV) exhibit distinct sensitivities to the scattering mechanisms of ground targets, thereby enabling applications such as detailed crop classification and sea ice type discrimination [73]. On the whole, the three complementary information dimensions of amplitude, phase, and polarization together constitute the core advantage of SAR data, establishing its indispensable role in various application fields.

However, despite its all-weather imaging capability, strong penetration ability, and sensitivity to surface structure and scattering properties, SAR imagery remains inherently susceptible to coherent noise and geometric distortions. Mitigating these effects requires dedicated speckle-suppression and geometric-correction algorithms [74]. Furthermore, SAR images lack spectral and color information, resulting in grayscale and texture characteristics that differ from human visual experience, which complicates image interpretation. Therefore, jointly exploiting the structural and scattering properties of SAR data together with the spectral and visual cues from optical imagery has become a powerful means to improve the accuracy and robustness of remote sensing analysis.

2.3. Complementarity of OPT-SAR Fusion

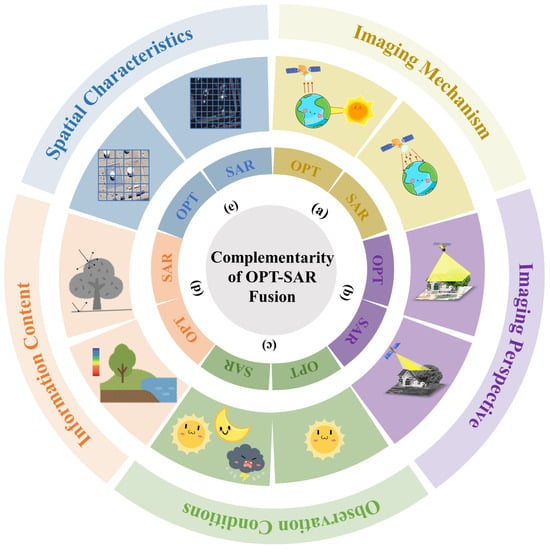

Based on the above analysis of the imaging mechanisms and information characteristics of optical and SAR, this section summarizes the complementarity of their fusion in terms of imaging mechanism, imaging perspective, observation conditions, information content, and spatial characteristics, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The complementarity of OPT-SAR fusion in (a) Imaging mechanism, (b) Imaging perspective, (c) Observation conditions, (d) Information content, (e) Spatial characteristics.

- Imaging Mechanism: Optical remote sensing imaging is a passive imaging technology that relies on solar illumination and the spectral reflectance characteristics of ground objects. In contrast, SAR operates as an active imaging system, which transmits and receives microwave signals to probe the geometric structure and dielectric properties of surface targets.

- Imaging Perspective: Optical systems typically employ a vertical viewing geometry to acquire primarily two-dimensional information of the top surfaces of ground objects. In comparison, SAR operates on a side-looking imaging geometry, making it highly sensitive to topographic variations and vertical structures.

- Observation Condition: Optical imaging is susceptible to meteorological factors such as clouds, rain, and fog, as well as variations in solar illumination. By contrast, SAR, owing to the penetration capability of microwave signals, provides consistent all-weather observation capacity.

- Information Content: Optical imagery provides intuitive spectral and color characteristics that are well-suited for object recognition and classification. In contrast, SAR data contains valuable scattering mechanisms and phase information, enabling effective surface deformation monitoring and three-dimensional structural analysis.

- Spatial Characteristic: Optical images present easily understandable planar macroscopic features, while SAR often has higher spatial resolution and is more sensitive to point targets and subtle changes.

In summary, these complementary relationships between optical and synthetic aperture radar remote sensing provide a theoretical basis and practical advantages for their deep integration.

2.4. Strategy of OPT-SAR Fusion

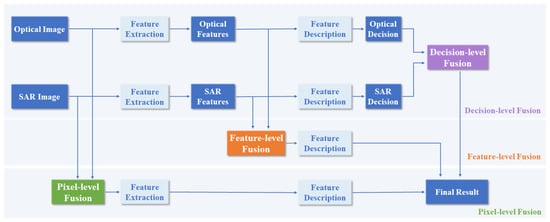

The goal of image fusion is to fully extract and utilize the complementary information contained in multi-source imagery, thereby producing integrated representations that are richer in information content and more effective in characterizing complex scenes. Based on the hierarchy of information fusion, OPT-SAR fusion are generally categorized into pixel-level, feature-level, and decision-level fusion, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

OPT-SAR fusion strategy.

Pixel-level fusion, based on rigorous image registration, directly fuses the original data at the image pixel level. This strategy not only yields richer and more accurate detailed information but also uncovers potential targets, preserving as much of the original image information as possible [52,75]. However, pixel-by-pixel fusion mechanism requires extremely high image registration accuracy, have high computational complexity, and are time-consuming, making them unsuitable for real-time processing.

Feature-level fusion places greater emphasis on extracting and analyzing semantic features from images, with the goal of more comprehensively characterizing the essential attributes of targets [58]. In this strategy, relevant features of interest, such as targets or regions, are extracted separately from optical and SAR first. Information modeling and fusion are then performed in the feature space to achieve complementarity and enhancement of cross-modal characteristics. As a result, feature-level fusion not only preserves key information adequate to support decision-making, but also alleviates certain limitations in pixel-level fusion, such as sensitivity to noise and the demand for extremely high image registration accuracy. Furthermore, the feature extraction stage is often accompanied by compression and dimensionality reduction. While this subsequent processing step reduces the amount of data required for fusion and improves real-time processing efficiency, it inevitably leads to the loss of some information, which may affect the completeness and richness of detail of the final fused output.

As the highest-level strategy in the fusion hierarchy, decision-level fusion is a cognitive-based high-level information fusion method. This strategy first extracts features from optical and SAR to generate preliminary decisions, and then employs predefined rules or models to jointly evaluate these independent decision outputs, thereby producing an optimized final decision. Compared to the previous two fusion strategies, decision-level fusion requires the least computation and can integrate multimodal information without high-precision registration [76]. However, the effectiveness of this strategy heavily relies on the initial decision outcomes from each modality. Any errors occurring in the preceding processing stages tend to be propagated and amplified throughout the fusion procedure. In addition, since decision-level fusion operates at a high-level decision-making level, it struggles to fully capture the detailed information embedded in low-level pixels or mid-level features. Therefore, it has inherent limitations in terms of fine target representation and preservation of complex spatial structures.

2.5. Core Challenges in OPT-SAR Fusion

Although OPT-SAR fusion has made significant progress across a wide range of downstream tasks, existing methods still face substantial challenges in achieving stable, generalizable, and efficient performance under complex real-world conditions. As illustrated in Figure 7, the challenges in OPT-SAR fusion are systematically organized by categorizing the main difficulties into two types: data-related challenges and technology-related challenges.

Figure 7.

The challenges in OPT-SAR fusion.

(i) Data-related Challenges: The fundamental differences between optical and SAR in terms of physical nature and representation form bring difficulties to their fusion.

First, the core obstacle lies in the semantic gap between optical and SAR. Optical imagery is typically based on a vertically downward-looking geometry, recording the spectral reflectance characteristics of surface features. In contrast, SAR imagery utilizes side-looking geometry and captures the microwave scattering mechanisms of targets. This fundamental difference in imaging principles results in the same object exhibiting drastically different geometric appearances and spatial backgrounds in the two modalities, leading to significant differences in feature representation. Consequently, models struggle to directly establish effective correspondences between the two modalities.

Secondly, the utility of OPT-SAR fusion is also constrained by spatiotemporal asynchrony and data imbalance. Because optical imaging is susceptible to adverse weather conditions and the revisit cycles of two satellites may not match, acquiring high-quality, time-synchronized optical and SAR images is extremely challenging. Moreover, prevalent class imbalance and long-tail distributions in datasets not only hinder model training but also severely diminish generalization and robustness in practical applications.

Third, the scarcity of high-quality fusion datasets has become a bottleneck in the development of current data-driven fusion models. Constructing an OPT-SAR dataset with complete labels faces two main challenges: first, acquiring multi-source data is costly and relies on precise spatiotemporal matching techniques; second, dataset annotation demands a very high level of expertise, requiring annotators to be proficient in optical and SAR image interpretation, which further increases the difficulty of data preparation. As a result, large-scale, high-quality OPT-SAR fusion datasets remain scarce. To mitigate this data dependency and enhance model robustness, recent studies have increasingly explored cross-modal representation learning under low-data regimes, including semi-supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and leveraging representations from large-scale pre-trained or foundation models [77,78,79].

(ii) Technology-related Challenges: In addition to the difficulties at the data level, the fusion model itself also has many technical bottlenecks, which limit its robust and efficient deployment in practical applications.

First, achieving cross-modal feature alignment and representation consistency between optical and SAR data presents a substantial challenge. Optical images are characterized by spectral and texture properties, whereas SAR images convey structural and scattering properties. This inherent difference leads to considerable divergence in their feature distributions and semantic representations. Although deep learning models can extract relevant features from both modalities, the absence of physically informed constraints often leads to fusion outputs plagued by information redundancy or modality bias. Consequently, effectively aligning and achieving semantic coherence between optical and SAR features remains difficult.

Secondly, in the case of modal inconsistency, it is often difficult to ensure the robustness and generalization ability of the model. In practice, optical images are susceptible to cloud occlusion and variations in illumination, whereas SAR images are frequently degraded by speckle noise and geometric distortions. When one modality degrades in quality or is missing, most existing methods cannot adaptively balance the informational contributions from different modalities, making them vulnerable to being dominated by noisy or anomalous inputs, which ultimately compromises the stability and generalization performance of the model. This limitation is further exacerbated in dynamically changing environments, such as seasonal variations, land-cover evolution, or rapid urbanization, where optical and SAR observations may exhibit pronounced temporal inconsistencies that challenge fusion models trained under static assumptions.

Third, model complexity and computational efficiency severely restrict engineering deployment. Most state-of-the-art multimodal fusion networks exhibit substantial architectural complexity and large parameter counts, making them difficult to deploy for real-time inference on resource-constrained edge devices. Consequently, achieving model lightweighting and accelerated inference while maintaining fusion performance remains a critical bottleneck in the engineering deployment of OPT-SAR fusion.

Overall, these challenges suggest that future OPT-SAR fusion methods may need to progressively move beyond static, task-specific designs toward more adaptive, data-efficient, and environment-aware fusion paradigms.

3. Evolution of OPT-SAR Fusion

The development of OPT-SAR fusion technology reflects the evolution from model-driven traditional methods to data-driven deep learning methods. Its core challenge has always been overcoming the inherent differences in physical mechanisms and geometric representations between the two types of data, thereby achieving effective alignment and collaborative fusion of multi-source information in complex scenarios while fully preserving the characteristics of the source information.

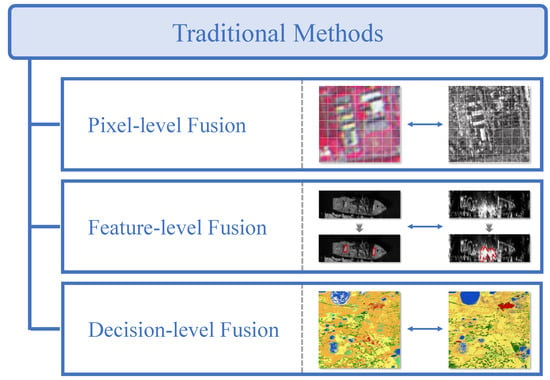

3.1. Traditional Methods

Traditional OPT-SAR fusion methods primarily relied on physical priors and manually designed rules to achieve complementarity between spectral information and structural features through explicit modeling. Following the fusion strategies introduced in Section 2.4, traditional OPT-SAR fusion approaches can be categorized into pixel-level, feature-level, and decision-level fusion, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

The traditional methods of OPT-SAR fusion, including pixel-level fusion methods [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88], feature-level fusion methods [89,90,91], and decision-level fusion methods [76,92,93].

(1) Pixel-Level Fusion Methods: As the most basic fusion method, pixel-level fusion mainly utilizes mathematical transformations and statistical properties to directly transform and reassemble pixels of images. Following the classic framework proposed in Ghassemian [80], pixel-level fusion methods for OPT-SAR fusion include component substitution (CS), multiresolution analysis (MRA), hybrid methods, and model-based algorithms.

Among them, CS-based methods transform optical images into alternative domains to decouple spatial and spectral components, substitute the extracted spatial component with SAR information, and then apply an inverse transform to reconstruct the fused image in the original space. Mainstream techniques in this strategy include Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [34], Gram-Schmidt (GS) Transform [35], Intensity-Hue-Saturation (IHS) Transform [36], Brovey Transform (BT) [37], and High Pass Filtering (HPF) [38]. The main advantage of CS-based methods lies in their conceptual simplicity and low computational cost, which makes them attractive for large-scale or time-sensitive fusion tasks. However, their dependence on cross-modal correlation makes them vulnerable to spectral distortion when the SAR and optical components mismatch [81].

To overcome these limitations, researchers have developed MRA-based methods. The core idea of MRA is to decompose an image into multiple scales, fuse the information of the corresponding subbands at each scale according to predefined rules, and reconstruct the final image through an inverse transform, thereby mitigating spectral distortion. Commonly used multi-scale decomposition techniques include the Pyramid Transform [39] and the Wavelet Transform [40], which can effectively separate the low-frequency contours and high-frequency details of an image, providing flexible support for subsequent fine-grained fusion. By explicitly separating structural information and detail components, MRA-based methods generally achieve better spectral preservation than CS-based approaches while still enhancing spatial details [82]. Nevertheless, their performance is sensitive to the selection of decomposition levels and fusion rules, and improper parameter settings may introduce artifacts [83].

Furthermore, hybrid methods combine CS and MRA [84], which is beneficial for achieving the synergistic fusion of spatial details and spectral features. By jointly exploiting domain transformation and multi-scale analysis, hybrid methods can achieve a more balanced trade-off between spatial enhancement and spectral fidelity [85]. However, this advantage is obtained at the cost of increased algorithmic complexity and parameter tuning, which limits their robustness and general applicability across diverse datasets.

In addition, researchers have proposed model-based algorithms, which mainly include variational models [86] and sparse representation-based models [87]. These methods typically optimize the fusion effect by constructing energy functions or sparse constraint terms, which can maintain spatial details and spectral consistency to some extent, but their computational complexity is high. Their main strength lies in the explicit incorporation of prior knowledge, which enables better control over the preservation of spatial detail and spectral consistency. Despite their effectiveness, model-based methods usually suffer from high computational complexity and limited scalability, making them less suitable for large-scale or real-time remote sensing applications [88].

(2) Feature-Level Fusion Methods: Unlike pixel-level fusion, traditional OPT-SAR feature-level fusion methods do not rely on explicit transformations in the pixel space. Instead, they establish a mapping between multi-source images features and the mission objective in the feature space through a learned model. These approaches generally employ shallow statistical learning models, such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests (RF), or Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), which directly act on the fused feature vectors to achieve joint modeling of multi-modal information and mission prediction. Liu et al. [89] generated initial candidate regions using optical images, and then further filtered targets using SAR images; subsequently, constructed OPT-SAR fusion features and used OC-SVM to achieve robust detection and identification of ships. Räsänen et al. [90] targeted peatland water level monitoring by extracting vegetation and moisture indices from Sentinel-2 optical imagery and scattering/polarization features from Sentinel-1 SAR imagery. Combining these with measured groundwater levels, a feature-level fusion relationship was established using random forest, achieving quantitative inversion of groundwater levels from multiple remote sensing sources. Breunig et al. [91] utilized an MLR model to fuse PlanetScope optical imagery and Sentinel-1 SAR imagery, achieving high-precision estimation of cover crop biomass in southern Brazil.

(3) Decision-Level Fusion Methods: It mainly integrates the preliminary decision results from optics and SAR, respectively, through decision-making methods to improve the robustness of the final decision. Commonly used decision-making methods include weighted voting, Dempster-Shafer Evidence Theory, and Bayesian Inference. Chen et al. [76] extracted GLCM texture features from Sentinel-1 SAR and Landsat-8, performed single-source classification using SVM, and then used a majority voting algorithm to aggregate the optimal crop classification results. Yang and Moon [92] used Dempster-Shafer evidence theory to study OPT-SAR decision-level fusion. Maggiolo et al. [93] proposed a Bayesian Inference decision fusion method for ground cover classification.

The performance ceiling of traditional model-driven approaches is often constrained by the completeness of human prior knowledge. Therefore, when dealing with the complex nonlinear modal differences between optical and SAR images, reliance on handcrafted features and rules often fails to achieve comprehensive and precise adaptation. With the significant improvement in computing power and the emergence of large-scale open-source remote sensing datasets, data-driven methods, represented by deep learning, have gradually become mainstream in fusion research. These methods learn the optimal fusion rules and feature representations directly from large-scale data through end-to-end training, thereby eliminating the dependence on manual feature design and significantly improving the model’s generalization ability in complex scenarios.

3.2. Deep Learning-Based Methods

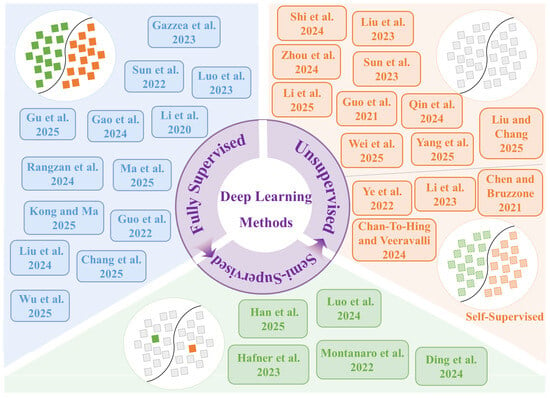

Deep learning, with its end-to-end nonlinear mapping capabilities, enables models to automatically learn the intrinsic connections and complementary characteristics between optical and SAR images directly from massive amounts of data, thus driving the paradigm shift in OPT-SAR fusion from manually designed features to automatic feature learning. At this stage, the importance of data is significantly amplified. This section focuses on deep learning-based OPT-SAR fusion methods, systematically summarizing existing research and categorizing these methods into three types based on the degree of dependence of model training on labeled information: fully supervised, semi-supervised, and unsupervised (self-supervised) learning methods, as shown in Figure 9. In addition to the supervision-based taxonomy, representative methods are further discussed from the perspective of network architectures and model paradigms, including CNN-based, Transformer-based, generative, and foundation model-based approaches.

Figure 9.

The deep learning-based methods of OPT-SAR fusion, including fully supervised [23,41,42,43,44,45,94,95,96,97,98,99,100], semi-supervised [46,77,101,102,103], unsupervised [22,47,48,78,104,105,106,107,108,109], and self-supervised learning [110,111,112,113].)

(1) Fully Supervised Learning Methods: The fully supervised learning paradigm refers to training models using large-scale, precisely registered paired data during the training phase. Its optimization objective is to minimize the difference between the network’s predicted output and the ground-truth supervision signals. To fully exploit the complementary information between optical and SAR modalities, researchers have systematically refined network architectures. Sun et al. [23] introduced a modified symmetric U-Net with non-uniform convolutional kernels to enhance the network’s focus on target characteristics. Similarly, Gazzea et al. [94] adapted an enhanced U-Net for OPT-SAR fusion, enabling high-resolution mapping of forest structural parameters. Luo et al. [95] employed a dual-branch decoder with feature interaction mechanisms to improve texture details and structural fidelity in fused images. Considering the inherent heterogeneity between optical and SAR features, Gu et al. [41] proposed a heterogeneous parallel network, which utilizes separate Transformer and CNN encoder branches to extract modality-specific features. In addition to architectural innovations, various optimization strategies have been incorporated to enhance model representation capacity and generalization. To address noise interference and sample imbalance, Gao et al. [42] designed a dual-channel feature enhancement and noise suppression module, which facilitates efficient cross-modal fusion and significantly improves land cover classification performance. With the increasing depth and complexity of networks, attention mechanisms are widely adopted to guide models in adaptively selecting relevant features. Li et al. [96] proposed a collaborative attention-based heterogeneous gated fusion network, which adaptively models the complementary relationship between optical and SAR features. Rangzan et al. [97] combined channel attention with a global-local attention module to enhance model performance. Ma et al. [43] specifically enhanced the fusion effect on edge structure regions by designing Laplacian convolution and a multi-source attention fusion module. Differing from conventional attention mechanisms, Kong and Ma [98] proposed a fine-grained fusion strategy based on uncertainty principles, introducing a statistical prediction interval mechanism for adaptive feature selection and transmission. Several studies have also emphasized the importance of contextual information. Guo et al. [44] designed a light-ASPP structure to enhance the utilization of multi-scale spatial contextual information. Liu et al. [99] used structural priors from SAR to guide the reconstruction of missing regions in optical, achieving more accurate cloud removal. Chang et al. [100] introduced a matching attention module to solve the cross-modal alignment problem and combined it with a long short-term memory network to achieve accurate semantic segmentation. In addition, Wu et al. [45] proposed a multimodal, multi-task complementary fusion network, which significantly improves the overall performance under complex weather conditions by jointly learning semantic segmentation and cloud removal tasks. From an architectural perspective, fully supervised OPT-SAR fusion models can be broadly categorized into CNN-based architectures, which emphasize local feature extraction and multi-scale spatial modeling, and Transformer-based or hybrid CNN–Transformer architectures, which are more effective in capturing long-range dependencies and complex cross-modal interactions. Recent studies increasingly adopt hybrid designs to balance representation capacity and computational efficiency. Because the fully supervised training paradigm uses labeled data as input during training, its model learning objectives are clear, the process is controllable, and its performance is powerful and easy to evaluate. However, precisely because of this, its performance heavily relies on large-scale, high-precision labeled data, resulting in high dataset acquisition costs. Furthermore, the model is prone to overfitting to a specific training set distribution, leading to insufficient cross-domain generalization ability. When faced with phenomena such as sensor switching, changes in imaging conditions, or geographical migration, the model’s performance is likely to degrade significantly. Therefore, research paradigms are gradually shifting towards reducing supervised signals to alleviate core bottlenecks such as high labeling costs, difficulties in cross-modal registration, and poor model generalization.

(2) Semi-supervised Learning Methods: Compared to fully supervised learning paradigms that rely entirely on labeled data, semi-supervised learning paradigms combine a small amount of labeled data with a large amount of unlabeled data for training. It typically employs methods such as pseudo-labels, consistency regularization, and self-supervised pre-training to enhance the supervision signal. Among these, pseudo-label-based methods utilize the model’s predictions of unlabeled data to generate pseudo-labels, which are then used for subsequent training. Han et al. [101] introduced a difference-guided complementary learning mechanism into the OPT-SAR fusion to characterize modal differences, and improves the usability of pseudo-labels through a multi-level label reassignment strategy. In a related development, Luo et al. [46] extended the concept of pseudo-labeling to cross-domain feature adaptation for target detection, constructing a semi-supervised detection framework that transfers knowledge from optical to SAR domain. Consistency regularization-based methods utilize unlabeled data by applying perturbations and forcing the model to maintain consistency in its predictions across different perturbations. Hafner et al. [102] proposed a semi-supervised change detection framework based on consistency regularization. This framework leverages semantic consistency constraints between optical and SAR data on unlabeled samples to penalize inconsistencies in cross-modal outputs, thereby improving the model’s robustness in complex urban scenarios. In addition, semi-supervised methods based on self-supervised pre-training typically begin by leveraging large amounts of unlabeled data for pre-training, followed by supervised fine-tuning with a limited set of annotated samples. For example, Montanaro et al. [77] first performed self-supervised pre-training on unlabeled SAR and multispectral data, and then fine-tuned it using only a small amount of labeled data to complete the land cover classification task. Furthermore, contrastive learning can be integrated into semi-supervised frameworks as a self-supervised pre-training strategy. Ding et al. [103] first classified samples by confidence levels using multi-level probability estimation, then employed contrastive learning strategies to fully exploit the latent information embedded in unreliable samples. This approach effectively mitigates pseudo-label noise while enhancing the generalization capability of the fusion model. From an architectural perspective, most semi-supervised OPT-SAR fusion methods adopt backbone networks similar to their fully supervised counterparts, with the primary innovations lying in training strategies rather than network structures. In summary, the semi-supervised learning paradigm constructs fusion models by jointly leveraging a small amount of labeled data and a large volume of unlabeled data. This approach significantly reduces dependence on manual annotation and associated costs while effectively enhancing model generalization. However, the performance of this paradigm remains constrained not only by the quality and quantity of annotated samples but also heavily relies on the reliability of pseudo-labels or consistency constraints. When initial model predictions contain systematic biases, such errors can be progressively amplified through iterations over unlabeled data, leading to error accumulation and eventual model performance degradation.

(3) Unsupervised Learning Methods: When labeled samples become increasingly scarce or even missing, unsupervised learning will become a key direction for OPT-SAR collaborative interpretation. These methods typically unfold along two main lines: domain adaptation and generative modeling. Unsupervised domain adaptation aims to leverage knowledge from a labeled source domain to address tasks in an unlabeled target domain. Shi et al. [78] proposed an unsupervised domain adaptation method based on progressive feature alignment, gradually reducing the feature distribution differences through feature-calibrated domain alignment and feature-enhanced class alignment, thereby improving ship classification performance under cross-modal conditions. Liu et al. [104] used a feedback-guided mechanism to suppress interference regions during cross-reconstruction domain adaptation. Zhou et al. [22] developed a latent feature similarity-based cross-domain few-shot SAR ship detection algorithm, which exploits implicit spatial consistency between optical and SAR images to achieve domain-adaptive feature transfer, significantly enhancing detection performance under limited sample conditions. In addition, generative modeling aims to learn the mapping relationship between optical and SAR domains without relying on strictly paired training data. From a model paradigm perspective, generative models constitute a representative class of architectures for cross-modal OPT-SAR translation. Mainstream research in this area primarily revolves around cycle-consistent generative adversarial networks (CycleGAN) [114] and diffusion models [32], which have been widely applied to downstream tasks such as cross-modal image translation and generation. The core innovation of CycleGAN lies in its introduction of cycle-consistency loss, which effectively captures intrinsic relationships between optical and SAR modalities. This enables the model to maintain semantic consistency even in real-world scenarios where paired samples are unavailable [47,105,106]. Diffusion models adopt a probability-based modeling approach. By explicitly learning the forward noising and reverse denoising processes of data distribution, and employing multi-step iterative refinement for generating the target image, they achieve theoretically more stable training and higher fidelity in synthesis [48,107,108,109].

Self-supervised learning, as a specialized form of unsupervised learning, enables models to learn powerful feature representations by designing pretext tasks that generate supervisory signals directly from the data itself, eliminating reliance on external annotations. Mask-based reconstruction methods randomly mask portions of input data and train the model to recover the masked content, thereby learning contextual representations of the data [110]. Contrastive learning methods, on the other hand, construct positive and negative sample pairs to learn a feature space, making the representations of similar samples close together and the representations of dissimilar samples far apart [111,112]. Additionally, image reconstruction methods treat the restoration task itself as a pretext task, ensuring the model can recover original information from corrupted or noisy inputs, thereby learning useful features [113]. Self-supervised methods eliminate the dependence on expensive labeled data, demonstrating enormous application potential and excellent cross-domain generalization ability in application scenarios with scarce annotations and weak registration. However, the main challenge lies in the objective gap between the pretext task and the downstream fusion task, which generally results in a performance ceiling lower than that of fully supervised approaches. Moreover, due to the complexity of training strategies, improper design may lead the model to learn shortcut features irrelevant to the core task.

Discussion on Foundation Model-based Approaches: Finally, beyond conventional task-oriented architectures, recent advances in large-scale representation learning have led to the emergence of foundation model paradigms. Foundation models generally refer to models pre-trained on large-scale datasets using self-supervised or weakly supervised objectives [115], which learn general-purpose representations and can be adapted to various downstream tasks with minimal task-specific training, thereby demonstrating strong transferability across tasks and domains [116,117]. In the context of remote sensing, preliminary studies have explored large-scale pre-training and foundation model paradigms for multi-source Earth observation data, showing improved robustness under limited supervision and cross-domain settings [79,118]. Although applications of foundation models to OPT-SAR fusion remain limited at present, these developments indicate a promising direction for learning more generalizable cross-modal representations, complementing existing supervised and generative fusion frameworks.

4. Summary of Open-Source Resources

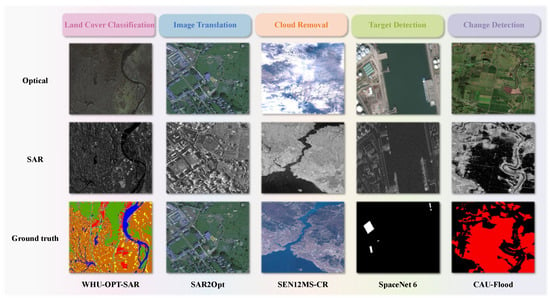

In recent years, a variety of OPT-SAR fusion datasets and code repositories covering multiple tasks and scenarios have been progressively developed and made publicly available. These resources primarily support the following downstream tasks: land cover classification, image translation, cloud removal, target detection, and change detection.

Land cover classification integrates the geometric structural information from SAR with the spectral characteristics of optical imagery to achieve accurate land cover mapping. The core challenge lies in mitigating SAR speckle noise and minimizing the impact of illumination and seasonal variations in optical data. Image translation focuses on converting between optical and SAR modalities. The primary difficulty of this task is to achieve cross-domain style transfer without altering the structural semantics of ground objects, while avoiding detail blurring and artifact generation. This capability is particularly valuable for compensating for data gaps in either modality. Cloud removal leverages SAR data to reconstruct cloud-free optical imagery by recovering texture and spectral information obscured by cloud cover, thus overcoming the long-standing limitations of optical remote sensing. Additionally, a substantial body of research focuses on enhancing the detection accuracy of specific targets by synergistically combining the complementary advantages of optical and SAR imagery. It is also noteworthy that multi-source change detection utilizes temporally mismatched optical and SAR data to monitor surface changes caused by extreme weather events and geological disasters, as well as urbanization. This approach effectively overcomes the observation interruptions that often affect single-source data due to adverse atmospheric conditions or inconsistent imaging schedules.

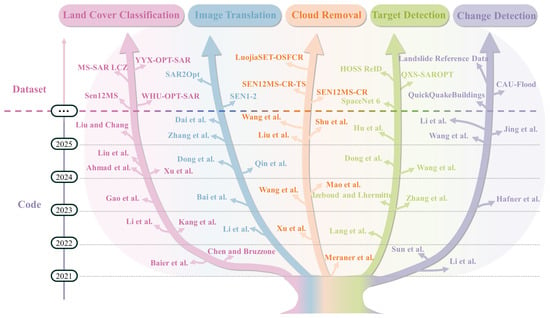

This chapter aims to provide a systematic review of publicly available OPT-SAR fusion datasets and open-source codes for these five representative tasks, as illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

The open-source resources of OPT-SAR fusion, including datasets [20,49,50,75,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129] and codes [21,47,49,51,102,109,111,122,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155].

4.1. Datasets

This section systematically summarizes open-source datasets relevant to typical OPT-SAR fusion applications. Table 3 provides a structured overview of commonly used open-source datasets across multiple dimensions, including application task, dataset name, data source, and access method, to facilitate the selection of appropriate data resources for different OPT-SAR fusion tasks.

Table 3.

Open-source datasets for different tasks in OPT-SAR fusion.

- Land Cover Classification

Sen12MS Dataset [119]: Comprises 180,662 spatiotemporally aligned patch pairs of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 from global coverage, accompanied by MODIS land cover labels. This dataset is characterized by its large volume, global coverage, and seasonal diversity, making it one of the most widely used benchmark datasets for OPT-SAR fusion. It is particularly suitable for large-scale land cover classification tasks that require global coverage and multi-seasonal training data.

MS-SAR LCZ Dataset [120]: Integrates 10-band multispectral imagery from Sentinel-2 and dual-polarization SAR data from Sentinel-1, with annotations covering 10 land cover categories. This dataset is mainly used for urban land cover and local climate zone (LCZ) classification in OPT-SAR fusion studies.

WHU-OPT-SAR Dataset [49]: Contains 100 high-resolution, accurately co-registered image pairs from Chinese satellites, with each optical image sized 5556 × 3704 pixels. Optical data are sourced from the Gaofen-1 (GF-1) satellite and SAR data from the Gaofen-3 (GF-3) satellite. It encompasses diverse terrains in Hubei Province, China. The dataset is suitable for fine-grained land cover classification and feature extraction in high-resolution OPT-SAR fusion scenarios.

YYX-OPT-SAR Dataset [75]: Consists of 150 high-resolution SAR and optical image pairs with a ground resolution of 0.5 m. The optical images are sourced from Google Earth, and the dataset covers three distinct scene types—urban, suburban, and mountainous—around Weinan City, Shaanxi Province. It is commonly used to evaluate land cover classification and fusion performance under high-resolution OPT-SAR fusion scenarios.

- Image Translation

SEN1-2 Dataset [121]: This is the world’s largest and most widely used benchmark dataset for paired OPT-SAR imagery. It comprises over 280,000 globally covered, all-season sampled Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 image pairs. The dataset is specifically designed to support OPT-SAR image translation and cross-modal generation tasks.

SAR2Opt Dataset [20]: This dataset consists of SAR data acquired by TerraSAR-X and optical images obtained from Google Earth Engine. It includes paired geospatial data from ten cities, collected between 2007 and 2013. It is commonly used to evaluate generative models for SAR-to-optical translation, with an emphasis on structural and semantic consistency.

- Cloud Removal

SEN12MS-CR Dataset [122]: A multimodal single-temporal dataset specifically designed for cloud removal research. Its radar and optical data are sourced from Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2, respectively. Focusing on urban landscapes, the dataset features an average cloud coverage of 48% across all samples, encompassing various typical cloud conditions from clear and cloud-free images to semi-transparent haze or broken clouds, and even dense, large cloud obstructions.

SEN12MS-CR-TS Dataset [123]: A multimodal, multi-temporal dataset designed for global, all-season cloud removal research. It covers 53 globally distributed regions of interest and provides Sentinel-1, Sentinel-2, and binary cloud masks for model training and evaluation.

LuojiaSET-OSFCR Dataset [50]: This dataset is derived from Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2. The test set contains 4000 samples, categorized by cloud coverage gradients from 0–20% to 80–100%. It can be used to investigate the substantial impact of land cover type and cloud coverage extent on reconstructing missing information.

- Target Detection

SpaceNet 6 Dataset [124]: This dataset comprises SAR data provided by Capella Space and paired optical imagery from Maxar’s WorldView-2 satellite, along with highly detailed building footprint polygon annotations. It serves as a challenging benchmark for evaluating the performance of fusion models in target detection and footprint extraction within complex urban scenarios.

QXS-SAROPT Dataset [125]: This dataset includes 20,000 GF-3 SAR images and corresponding Google Earth optical images collected over Chinese regions, covering three port cities: Santiago, Shanghai, and Qingdao. It is commonly used for port target detection tasks.

HOSS ReID Dataset [126]: A ship re-identification dataset that integrates data from the Jilin-1 optical constellation and the TY-MINISAR satellite constellation. It contains images of the same ships captured at different times, from various angles, and under different imaging modes by multiple satellites over extended periods. The dataset is designed to evaluate the effectiveness of optical and SAR low Earth orbit constellations in ship tracking tasks.

- Change Detection

CAU-Flood Dataset [127]: A cross-modal flood detection dataset that aggregates pre-disaster Sentinel-2 optical imagery and post-disaster Sentinel-1 SAR imagery from 18 study areas worldwide, with a total coverage area of 95,142 km2. It is mainly used for OPT-SAR flood change detection and disaster response analysis.

QuickQuakeBuildings Dataset [128]: The dataset integrates SAR imagery acquired by Capella Space on 9 February with optical data from WorldView-3 obtained on 7 February. It is designed to support rapid building damage assessment using multi-source remote sensing data, providing critical information for emergency response and reconstruction planning.

Landslide Reference Dataset [129]: Contains annotated samples of multiple major landslides occurring globally since July 2015, with each event supported by Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2. The dataset covers landslides of various scales and types across diverse environmental and climatic contexts, predominantly rainfall-induced, and includes both single landslides and clustered landslide events. It is suitable for remote sensing intelligent analysis tasks such as automated landslide identification, change detection, and disaster assessment.

Representative image samples from the aforementioned open-source datasets are presented in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Representative image samples from open-source dataset.

4.2. Codes

In recent years, the open-source ecosystem for OPT-SAR fusion research has been progressively maturing. Table 4 summarizes representative publicly available algorithm codes from the past five years, covering typical tasks such as land cover classification, image translation, cloud removal, target detection, and change detection.

Table 4.

Representative open-source codes for OPT-SAR fusion (2021–2025).

- Land Cover Classification

Early work by Baier et al. [134] synthesized paired optical and SAR data from land-cover maps and evaluated fusion consistency under controlled experimental settings, providing an early benchmark for multimodal land-cover modeling. Chen and Bruzzone [111] investigated self-supervised OPT-SAR fusion for land-cover classification and compared learned fusion representations with single-modality baselines on the DFC2020 dataset. Building upon optical-guided knowledge transfer, Kang et al. [51] proposed DisOptNet and conducted comparative experiments on urban building segmentation datasets, demonstrating improved SAR segmentation robustness through optical-guided knowledge distillation. With the introduction of task-oriented benchmarks, Li et al. [49] released the WHU-OPT-SAR dataset and proposed a multimodal cross-attention network (MCANet) for OPT–SAR fusion, validating its effectiveness through comparative experiments on land use classification tasks against single-modality baselines. Focusing on agricultural applications, Gao et al. [133] proposed a fully automated rice mapping (FARM) framework and conducted comparative experiments on multi-temporal Sentinel-1/2 data for large-scale rice mapping, comparing fusion-based models with optical-only approaches across different growing seasons. To address adverse observation conditions Xu et al. [132], proposed a multimodal learning framework, termed CloudSeg, for robust land-cover mapping under cloudy conditions, and evaluated its performance through comparative experiments on the M3M-CR and WHU-OPT-SAR datasets. Similarly, Ahmad et al. [131] proposed an ensemble-based urban impervious surface extraction framework (UISEM) and conducted comparative experiments on ESA WorldCover, ESRI Land Cover, and Dynamic World datasets to assess the effectiveness of optical–SAR fusion across multiple machine-learning classifiers. Liu et al. [130] systematically compared CNN- and Transformer-based fusion models on large-scale urban land-cover datasets, demonstrating that the proposed SAR–Optical fusion transformer (SoftFormer) more effectively captures long-range dependencies in OPT-SAR fusion. Finally, Liu and Chang [109] proposed one of the first diffusion-based models for multimodal clustering, termed CDD, and conducted comparative experiments against ten state-of-the-art multimodal clustering methods on public benchmark datasets.

- Image Translation

Early studies focused on generative adversarial networks for SAR-to-optical image translation. Li et al. [140] evaluated SAR-to-optical image translation on the SEN1-2 dataset using a multiscale generative adversarial network based on wavelet feature learning (WFLM-GAN), and conducted comparative analyses focusing on visual fidelity and structural consistency against alternative fusion strategies. More recently, diffusion-based models have been introduced to address the limitations of GAN-based approaches. Bai et al. [139] investigated conditional diffusion-based SAR-to-optical image translation on the GF-3 and SEN1-2 datasets, and compared diffusion-based models with GAN-based methods to demonstrate improved structural detail preservation. To further improve efficiency, Qin et al. [138] proposed an efficient end-to-end diffusion model, termed E3Diff, and conducted comparative experiments on the UNICORN and SEN1-2 datasets against eight state-of-the-art image-to-image translation methods, highlighting its efficiency advantages over multi-step diffusion baselines. Beyond single-temporal settings, Dong et al. [137] proposed a multi-temporal SAR-to-optical image translation network (MTS2ONet) and evaluated its performance on the SEN1-2 dataset with missing optical observations, comparing fusion-based reconstruction results with single-temporal baseline methods. In parallel, Zhang et al. [136] conducted cross-modality domain adaptation research from optical to SAR imagery, comparing the proposed semantic graph learning framework (SGLF) with conventional domain adaptation baselines. Collectively, these studies demonstrate the evolution of image translation in optical and SAR from GAN-based models to diffusion and multi-temporal fusion frameworks, with increasing emphasis on robustness, efficiency, and fair comparison on public benchmark datasets. Dai et al. [135] further extended this line of research by proposing a periodic imputation generative adversarial network (PIGAN) for reconstructing large-scale systematically missing NDVI time series, and validated its effectiveness through comparative optical–SAR fusion experiments.

- Cloud Removal

Early studies explored SAR-assisted cloud removal using deep learning on multimodal time-series datasets. Meraner et al. [122] evaluated SAR-guided cloud removal using the proposed DSen2-CR model on the SEN12MS-CR time-series dataset, demonstrating the effectiveness of SAR information for reconstructing cloud-contaminated optical imagery. Building upon this line of research, Xu et al. [21] proposed a global–local fusion–based cloud removal framework (GLF-CR) and conducted comparative experiments on the SEN12MS-CR dataset, showing improved reconstruction performance under dense cloud coverage. To further enhance spatial–spectral consistency, Wang et al. [145] proposed a unified spatial–spectral residual network (USSRN-CR) and evaluated its performance on multiple cloud-contaminated datasets, including spaceborne, airborne, and SEN12MS-CR datasets, achieving superior cloud removal accuracy compared with existing baselines. Beyond single-image reconstruction, Mao et al. [144] investigated spatio-temporal SAR–optical fusion for NDVI time-series reconstruction and compared regression-based fusion strategies on long-term satellite observations, highlighting the benefits of incorporating temporal context. Focusing on vegetation-covered regions, Liu et al. [143] proposed a spatiotemporal optical reflectance interpolation framework (STORI) and conducted comparative evaluations against baseline methods for SAR–optical reflectance time-series reconstruction. More recently, diffusion-based models have been introduced for cloud removal and time-series restoration. Shu et al. [142] proposed a diffusion Transformer–based multimodal fusion framework, RESTORE-DiT, and evaluated its performance on public multimodal satellite time-series datasets, demonstrating improved reliability in reconstructing missing observations. In parallel, Wang et al. [141] proposed a multilayer translation generative adversarial network (MT-GAN) for SAR–optical cloud removal and conducted comprehensive comparative experiments on multiple benchmarks, including SEN1-2, SEN12MS-CR, and QXS datasets, validating its effectiveness across diverse cloud scenarios.

- Target Detection

Lang et al. [151] evaluated multisource heterogeneous transfer learning (MS-HeTL) using optical-guided fusion for SAR ship classification on HR-SAR and FUSAR datasets. Focusing on structural feature extraction, Zhang et al. [150] proposed a keypoint detection method, named the multilevel attention Siamese network (SKD-Net), for keypoint detection in optical and SAR images, and compared Siamese fusion networks with conventional feature-matching baselines. Izeboud and Lhermitte [149] proposed the normalised radon transform damage detection (NeRD) method to detect damage features and their orientations from multi-source satellite imagery. Wang et al. [148] introduced the boundary information distillation network (BIDNet), and compared it with the existing state-of-the-art methods for building footprint extraction in SAR images on the SpaceNet 6 MSAW dataset. Addressing cross-domain generalization, Dong et al. [147] proposed an end-to-end cross-domain multisource ship detection network (OptiSAR-Net) and compared results with baselines on four single-domain datasets and one cross-domain dataset. Hu et al. [146] conducted aircraft detection experiments using a complementarity-aware feature fusion detection network (CFFDNet) and compared classical single-modal and multimodal detection models on CORS-ADD and MAR20 datasets, demonstrating improved detection accuracy under complex backgrounds.

- Change Detection

Early work by Li et al. [155] evaluated a deep translation based change detection network (DTCDN) on four representative datasets from Gloucester I, Gloucester II, California, and Shuguang village. To better capture structural consistency between heterogeneous images, Sun et al. [154] proposed a nonlocal patch similarity graph (NPSG)–based method, which exploits nonlocal self-similarity to measure structural consistency and demonstrated improved performance on heterogeneous change detection benchmarks. Addressing the scarcity of labeled data, Hafner et al. [102] investigated semi-supervised multimodal change detection and conducted comparative experiments on heterogeneous datasets, highlighting the effectiveness of fusion models under limited supervision settings. Focusing on emergency response scenarios, Wang et al. [153] proposed a refined heterogeneous remote sensing image change detection method (HRSICD) and evaluated its performance on low-resolution heterogeneous datasets for disaster monitoring applications. More recently, Jing et al. [152] proposed a fully supervised heterogeneous change detection framework, HeteCD, and conducted comparative evaluations against recent deep learning–based baselines, demonstrating improved feature consistency alignment across modalities. Finally, Li et al. [47] introduced a global and local change detection network with diversified attention (GLCD-DA), and performed extensive comparative experiments on public heterogeneous change detection benchmarks, showing enhanced global–local feature alignment and robustness through OPT–SAR fusion.

From the technical framework perspective, most of these open-source projects are developed based on the PyTorch framework. In terms of model architecture, CNN and ResNet variants remain the predominant backbone networks, while some works have begun incorporating Transformers to enhance global modeling capabilities for cross-modal features [130]. An analysis of the structural implementations in these OPT-SAR fusion codes reveals three mainstream design patterns. First, the dual-encoder single-decoder framework represents the most typical and widely adopted architecture [152]. Models of this type generally employ two independent encoders to extract optical and SAR features separately, achieve fusion at the feature level through concatenation, weighting, or attention mechanisms, and finally generate fused outputs using a shared decoder. Second is the generative adversarial framework, primarily applied to image translation and cloud removal tasks [135,141]. This framework enables high-fidelity cross-modal image reconstruction through generator-discriminator adversarial optimization. Finally, there is the cross-modal knowledge transfer framework [151], which primarily acquires semantic or boundary knowledge from optical modal models to guide the training of SAR models, thereby effectively alleviating the problem of insufficient SAR labeled samples.

In addition, several representative studies report comparative evaluations on widely used public benchmarks across different OPT-SAR fusion tasks, serving as useful reference points for understanding the relative performance of different fusion strategies [47,130,136,141,146]. The continuous emergence of these open-source resources has significantly enhanced the learnability and reproducibility of OPT-SAR fusion research, facilitating rapid model iteration and optimization. Furthermore, recent model development trends indicate that researchers, while pursuing performance improvements, are also increasingly focusing on model efficiency, generalization ability, and practical deployment feasibility. This development marks a significant step towards a more open and sustainable direction for OPT-SAR fusion technology.

5. Conclusions and Outlooks

In this paper, we present a comprehensive review of optical and SAR image fusion, covering its theoretical foundations, core challenges, methodological evolution, and open-source resources. By analyzing key scientific issues at both the data and technology levels, we summarize the major challenges faced by current OPT-SAR fusion methods and discuss the strengths and limitations of existing fusion paradigms. Building upon these analyses, we further outline several prospective directions for future research in OPT-SAR fusion.

Interpretable Fusion Models Driven by both Data and Knowledge: The limitations of purely data-driven fusion paradigms have made the inherent “black box” nature of deep neural networks increasingly evident, motivating a shift toward hybrid fusion frameworks that integrate physical mechanisms with data-driven modeling. By incorporating physical priors and domain knowledge constraints during model optimization, such approaches aim to enhance the credibility, interpretability, and physical consistency of fusion outcomes. This evolution reflects a transition from empirically dominated learning toward knowledge-guided fusion intelligence that systematically embeds domain expertise into model design.

General Fusion Perception Driven by Multimodal Large Models: In response to challenges related to data scarcity, limited supervision, and cross-scene generalization, large-scale multimodal models have emerged as a promising direction for OPT-SAR fusion. While large language models and multimodal foundation models have demonstrated strong open-ended understanding capabilities in general vision tasks, their potential remains largely unexplored in OPT-SAR fusion. Future research may focus on leveraging language or multimodal semantic priors to guide cross-modal alignment and representation unification, thereby reducing reliance on large-scale labeled data and promoting more generalizable, task-agnostic fusion models. Such advances may enable OPT-SAR fusion to move beyond task-centric designs toward more general-purpose and scalable intelligent remote sensing perception.

Lightweight Architectures with Efficient Deployment Strategies: Considering the increasing complexity of fusion models and practical deployment constraints, lightweight architectures and efficient deployment strategies have become critical research priorities. With growing demands in application scenarios such as emergency monitoring and disaster assessment, future efforts should emphasize low-latency, low-power fusion models that balance performance and efficiency. Integrating lightweight network design with edge–cloud collaboration and on-orbit intelligent computing may enable end-to-end real-time fusion and inference from satellite to ground systems, substantially enhancing the operational applicability of OPT-SAR fusion technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Z., Y.Y. and Z.L.; methodology, R.Z. and Y.Y.; software, R.Z.; validation, R.Z., Y.Y. and Z.L.; formal analysis, R.Z.; investigation, R.Z.; resources, R.Z. and P.L.; data curation, R.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.Y. and Z.L.; visualization, R.Z.; supervision, H.W.; project administration, H.W.; funding acquisition, H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62271153).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, J.; Chen, S.; Fu, R.; Li, D.; Jiang, H.; Wang, C.; Peng, Y.; Jia, K.; Hicks, B.J. Remote sensing big data for water environment monitoring: Current status, challenges, and future prospects. Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellmann, T.; Lausch, A.; Andersson, E.; Knapp, S.; Cortinovis, C.; Jache, J.; Scheuer, S.; Kremer, P.; Mascarenhas, A.; Kraemer, R.; et al. Remote sensing in urban planning: Contributions towards ecologically sound policies? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 204, 103921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, R.; Fisher, J.B.; Schimel, D.S.; Kareiva, P.M. Applying tipping point theory to remote sensing science to improve early warning drought signals for food security. Earth’s Future 2020, 8, e2019EF001456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoni, M.; Haelterman, R.; Perneel, C. Hypersectral imaging for military and security applications: Combining myriad processing and sensing techniques. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2019, 7, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gao, H.; Zhao, G.; Tseng, K.H. A high-resolution bathymetry dataset for global reservoirs using multi-source satellite imagery and altimetry. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 244, 111831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; He, J.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, S.; Chu, X.; Zhang, L. Automated glacier extraction using a Transformer based deep learning approach from multi-sensor remote sensing imagery. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 202, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanam, V.; Motagh, M.; Garg, S.; Jain, K. Multi-sensor remote sensing analysis of coal fire induced land subsidence in Jharia Coalfields, Jharkhand, India. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 102, 102439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.; Zhu, X.X. Data fusion and remote sensing: An ever-growing relationship. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2016, 4, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Zhao, W.; Li, X.; Hou, B.; Jiao, C.; Ren, Z.; Ma, W.; Jiao, L. A Semantically Non-redundant Continuous-scale Feature Network for Panchromatic and Multispectral Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5407815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, C.; Li, W.; Jia, S.; Yue, H. Hybrid model for estimating forest canopy heights using fused multimodal spaceborne LiDAR data and optical imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 122, 103431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, T.; Sagan, V.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ren, H.; Sun, Y.; Xu, W.; et al. Optical and thermal remote sensing for monitoring agricultural drought. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 5092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Ahmad, M.N.; Javed, A. Comparison of random forest and XGBoost classifiers using integrated optical and SAR features for mapping urban impervious surface. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tupin, F. Fusion of optical and SAR images. In Radar Remote Sensing of Urban Areas; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 133–159. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Fu, S.; Chen, J.; Wang, F.; Xu, F. Object-Level Semantic Segmentation on the High-Resolution Gaofen-3 FUSAR-Map Dataset. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 3107–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Suo, Y.; Meng, Q.; Dai, W.; Miao, T.; Zhao, W.; Yan, Z.; Diao, W.; Xie, G.; Ke, Q.; et al. FAIR-CSAR: A Benchmark Dataset for Fine-Grained Object Detection and Recognition Based on Single-Look Complex SAR Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5201022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, L.M.B.S.; Bruce, L.M.; Chanussot, J.; Prasad, S. Optical Remote Sensing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]