Highlights

What are the main findings?

- The proposed KGE-SwinFpn model, a novel RS landslide segmentation framework, effectively integrates knowledge graph embeddings with multi-scale image features, improving landslide segmentation accuracy across multiple datasets.

- Experiments demonstrate that incorporating domain knowledge enhances feature representation and model generalization, particularly in complex terrains.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The results highlight the potential of knowledge-guided deep learning as a powerful framework for remote sensing-based disaster analysis.

- The approach provides a foundation for developing more robust, interpretable, and transferable models for landslide monitoring and risk management.

Abstract

Landslide disasters are complex spatiotemporal phenomena. Existing deep learning (DL) models for remote sensing (RS) image analysis primarily exploit shallow visual features, inadequately incorporating critical geological, geographical, and environmental knowledge. This limitation impairs detection accuracy and generalization, especially in complex terrains and diverse vegetation conditions. We propose Knowledge Graph Embedding in Swin Feature Pyramid Networks (KGE–SwinFpn), a novel RS landslide segmentation framework that integrates explicit domain knowledge with deep features. First, a comprehensive landslide knowledge graph is constructed, organizing multi-source factors (e.g., lithology, topography, hydrology, rainfall, land cover, etc.) into entities and relations that characterize controlling, inducing, and indicative patterns. A dedicated KGE Block learns embeddings for these entities and discretized factor levels from the landslide knowledge graph, enabling their fusion with multi-scale RS features in SwinFpn. This approach preserves the efficiency of automatic feature learning while embedding prior knowledge guidance, enhancing data–knowledge–model coupling. Experiments demonstrate significant outperformance over classic segmentation networks: on the Yuan-yang dataset, KGE–SwinFpn achieved 96.85% pixel accuracy (PA), 88.46% mean pixel accuracy (MPA), and 82.01% mean intersection over union (MIoU); on the Bijie dataset, it attained 96.28% PA, 90.72% MPA, and 84.47% MIoU. Ablation studies confirm the complementary roles of different knowledge features and the KGE Block’s contribution to robustness in complex terrains. Notably, the KGE Block is architecture-agnostic, suggesting broad applicability for knowledge-guided RS landslide detection and promising enhanced technical support for disaster monitoring and risk assessment.

1. Introduction

Landslides are among the most pervasive and destructive geological hazards worldwide, causing significant casualties and substantial economic losses annually [1,2]. Accurate and timely mapping of landslide extent is therefore a prerequisite for effective disaster-risk reduction, yet it remains a central challenge in geomorphological and GIScience research [3]. Conventional inventory approaches rely on intensive field surveys that, while accurate, are time-consuming, require expert knowledge, and often lack precise quantitative descriptions [4]. With advances in remote sensing (RS)—particularly multispectral, high-resolution, and synthetic aperture radar (SAR) imaging—landslide detection has evolved significantly, leading to three main methodological categories: expert-driven visual interpretation, shallow machine learning (ML) classifiers, and deep learning (DL) architectures [5]. Visual interpretation, though reliable, is limited by manual effort and subjectivity, making it unsuitable for large-scale applications. ML models, such as support vector machines, random forests, and artificial neural networks, reduce subjectivity through handcrafted features; however, their generalizability is constrained by the quality and completeness of these features [6].

Building on these developments, DL-based semantic segmentation networks have become the core technique for pixel-level landslide mapping in RS imagery. Early applications were inspired by fully convolutional networks and encoder–decoder designs, where architectures such as U-Net and DeepLabV3+ were adapted from generic computer vision tasks to RS scenarios, enabling end-to-end learning of hierarchical spatial features directly from raw or minimally preprocessed images [7]. More recently, residual backbones (e.g., ResNet) and lightweight models (e.g., EfficientNet) have been coupled with feature pyramid networks, attention mechanisms, and Transformer-based architectures [8,9,10,11,12], progressively improving multi-scale context aggregation and long-range dependency modeling for complex terrains. Ongoing research continues to refine the trade-off between model complexity and computational efficiency to enhance both accuracy and practical utility in landslide disaster monitoring and mitigation [3]. Despite these advances, critical limitations persist when DL-based RS landslide segmentation models are deployed in real-world geographical settings. Landslides are governed by internal structures, deformation mechanisms, and failure processes that are rarely encoded in RGB or even multispectral feature spaces, and statistics indicate that more than 70% of catastrophic failures occur outside previously mapped hazard zones, suggesting that purely data-driven models underutilize existing geoscientific knowledge [13]. This underuse of domain knowledge reduces model generalization, particularly in complex terrain or under varying vegetation coverage conditions and makes predictions susceptible to background noise and spurious correlations.

Knowledge Graphs (KGs) [14] formalize the description of concepts, entities, attributes, and their interrelationships in the physical world, to provide systematic, comprehensive, and structured domain knowledge. As a structured form of landslide knowledge representation, landslide KGs offer a complementary modality for RS images and DL models by explicitly encoding causal relationships among geoenvironmental entities (e.g., lithology, faults, land cover, slope curvature, rainfall anomalies, etc.) in a machine-readable format [15]. Integrating KGs with DL models has recently improved scene classification and land-cover mapping [16]. Li et al. [17,18] constructed geoscience and land cover knowledge graphs to guide shallow feature learning in deep networks, offering new perspectives for the field. However, their approach primarily focuses on concept-level knowledge, leading to coarse-grained representations that may introduce noisy or irrelevant information. Cui et al. [19,20] proposed a Knowledge and Geo-Object Based Graph Convolutional Network (KGGCN) to address contextual distortion and spectral similarity issues in remote sensing by introducing object-level prior knowledge into graph neural networks. Xu et al. [21] incorporated landslide concepts and instance knowledge into ResNet for RS-based landslide recognition. However, its feature integration is superficial, mainly relying on simple feature concatenation and fusion at the decision layer, lacking deep interaction between multimodal features. Furthermore, generic geographical KGs rarely formalize landslide process-oriented concepts such as shear strength, pore-water pressure, complex terrain, or failure kinematics that are central to slope instability [17]. Moreover, existing KGs embedding techniques are often tightly coupled to specific network backbones, restricting their transferability and generalization across models [22,23]. Additionally, most KGs operate at the scene or object level, whereas landslide inventories require pixel-level delineation [17].

To address these limitations, this study proposes a generalized knowledge-embedding mechanism that injects geographic knowledge reasoning into DL architectures. Based on this mechanism, we introduce Knowledge Graph Embedding in Swin Feature Pyramid Networks (KGE–SwinFpn), a semantic-segmentation framework that fuses multi-scale Swin-Transformer [24] features from RS images with geological and geographical knowledge from landslide KGs. We design a lightweight, end-to-end differentiable embedding layer that converts subgraph vectors into pixel-wise attention maps, enabling seamless fusion with feature-pyramid networks. KGE–SwinFpn can substantially enhances landslide identification and segmentation accuracy, providing more reliable technical support for disaster monitoring and risk assessment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Basic Idea of KGE–SwinFpn

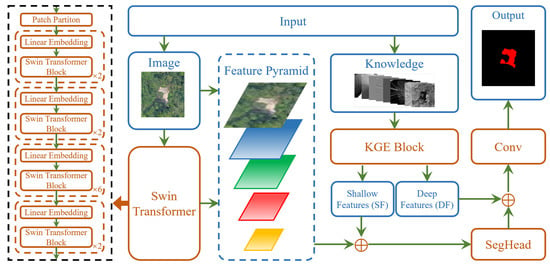

Conventional RS-based landslide feature extraction primarily captures low-level visual cues, inadequately representing the complex and heterogeneous nature of landslides. Additionally, regional variations in geological settings, driving forces, and terrain conditions lead to substantial differences in landslide morphology, scale, and kinematics, thereby limiting model generalizability. Therefore, integrating high-level semantic knowledge with low-level image features is therefore essential for improving landslide segmentation accuracy and robustness across diverse environments. We propose KGE–SwinFpn, a coupled framework that synergistically integrates Swin Transformer features with landslide knowledge graph (KG) embeddings (Figure 1). RS images are first processed through a hierarchical Swin Transformer, which employs window-based multi-head self-attention with shifted window mechanisms to capture local–global contextual interactions across four stages. This architecture progressively reduces feature map resolution while increasing channel depth, generating a multi-scale feature pyramid that transitions from high-resolution shallow details to low-resolution deep semantics, thus providing a rich hierarchical representation for landslide segmentation.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of deep coupling between the landslide knowledge graph and deep neural networks. KGE, Knowledge Graph Embedding; SegHead, Segmentation Head.

The KGE Block extracts high-level semantic features (e.g., terrain structure, geomorphology, lithology, etc.) from the landslide KG through specialized embedding techniques that quantify domain knowledge into dense vector representations. Optimized via a pretraining strategy that balances intra-class compactness and inter-class separability, these embeddings preserve meaningful semantic structures while being dimensionally aligned with each pyramid level. An attention mechanism dynamically modulates feature importance, while a progressive fusion mechanism (denoted by ⊕ in Figure 1) integrates knowledge embeddings with multi-scale image features through learnable weighted summation. This adaptive balancing, updated via backpropagation, enables deep interaction between semantic knowledge and visual cues rather than superficial concatenation, significantly enhancing feature expressiveness.

The Segmentation Head (SegHead) subsequently processes these fused features through progressive upsampling and convolution operations, effectively combining fine-grained spatial details from shallow layers with global semantic information from deep layers. This multi-level integration mitigates scale discrepancies between high-resolution and low-resolution features, reducing missed detections of small landslides while enhancing boundary precision. Final convolutional layers refine the representation to produce a clear binary segmentation map.

This fusion strategy leverages KG-encoded semantic relationships to guide RS image interpretation, enriching contextual understanding of disaster-prone environments and causal factors while enhancing reasoning capabilities under scarce data or weak annotation conditions. Moreover, the KGE Block is architecture-agnostic and can be seamlessly transplanted into arbitrary segmentation networks. We validate its generalization by systematically integrating it into multiple classical architectures and evaluating performance in different landslide geographic environments.

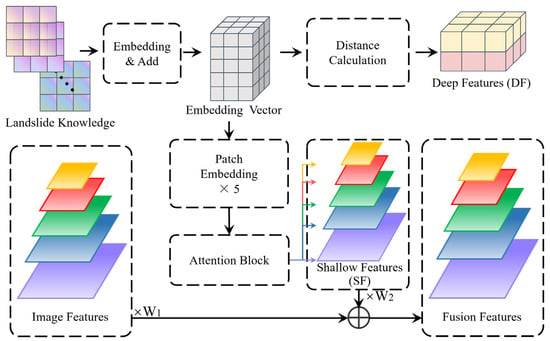

2.2. Landslide Knowledge Graph Embedding Block

The KGE Block’s working principle for fusing landslide knowledge-based features with RS image features is illustrated in Figure 2. First, heterogeneous knowledge features from multiple sources are embedded into a unified feature space, standardizing their representation format and reducing distributional discrepancies to ensure seamless alignment with the multi-scale image feature pyramid. These embedded features then undergo patch embedding [25] and attention mechanisms [26,27,28], generating shallow features (SFs) that preserve spatial distribution and local details. This complements the high-resolution features extracted from RS images and enhances the model’s representational capacity.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram illustrating the structure of the KGE Block model.

Meanwhile, a distance-based computation mechanism extracts deep features by measuring similarity or disparity between landslide feature representations, yielding more discriminative semantic features. These representations emphasize global contextual information and category differentiation, which are crucial for semantic segmentation. The SFs are fused with image features to enhance local detail representation and spatial consistency, while deep features integrate with segmentation outputs in the SegHead (discussed in Section 2.3).

By integrating both shallow and deep features, the KGE Block enhances the model’s capacity to leverage multi-source data, providing hierarchical, multi-scale, and semantically rich feature support for landslide segmentation. This significantly improves adaptability to complex terrains and diverse landslide types.

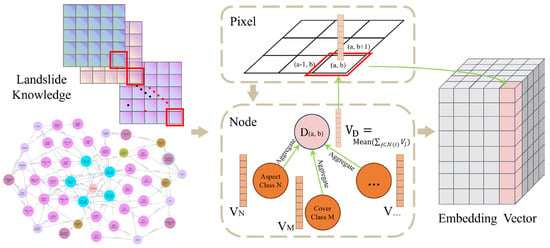

- (1)

- Feature Embedding and Add Module

Figure 3 illustrates the feature embedding module operating at the pixel level. Heterogeneous landslide knowledge (e.g., terrain, climatic, environmental factors, etc.) is discretized per pixel into categorical classes and embedded as fixed-dimensional vectors encoding semantic attributes. Each pixel node D(a, b) at spatial location (a, b) connects to corresponding attribute nodes. Through mean-aggregation message passing, D(a, b)’s embedding is computed as the average of its neighboring attribute node vectors, effectively integrating multi-source knowledge at pixel resolution. After computing all pixel embeddings via this graph-based aggregation, they are mapped back to the original geographic space, forming a pixel-aligned representation that synthesizes diverse knowledge types for subsequent segmentation tasks.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram depicting the structure of the Embedding and Add module.

- (2)

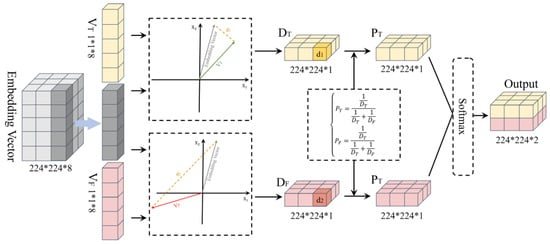

- Distance Calculation

The Distance Calculation module (Figure 4) establishes discriminative class centroids by computing average embedding vectors for landslide-positive (VT) and non-landslide (VF) samples. These reference points anchor the decision space. For each embedded knowledge feature, Euclidean distances to both centroids are calculated (DT to VT, DF to VF), quantifying relative proximity and encoding class-specific similarity relationships. Probabilistic classification scores (PT, PF) are subsequently derived from the following distance measurements:

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram showing the structure of the Distance Calculation module.

The final segmentation decision is obtained by applying Softmax normalization to these scores, yielding a posterior distribution that determines cluster membership based on embedding proximity. This distance-based computation mechanism emphasizes global contextual information and category differentiation at the decision level, providing robust representations that enhance discriminative capacity and improve segmentation accuracy in complex terrain.

- (3)

- Patch Embedding and Attention Block

Patch embedding converts input feature maps (RS image and knowledge-guided features) into compact token representations compatible with the Swin-based encoder. The input tensor is partitioned into non-overlapping patches along spatial dimensions, each projected to a latent vector via a small convolutional layer where kernel size and stride equal the patch size. This design provides flexible control: patch size determines spatial resolution and token count, while embedding dimension dictates vector length and representation capacity. An optional lightweight normalization layer stabilizes feature distribution before feeding into subsequent Swin blocks. By balancing spatial detail against computational cost, smaller patches preserve fine-scale information at the expense of more tokens, whereas larger patches yield compact sequences suitable for deeper layers, facilitating alignment with the FPN decoder’s multi-scale feature maps.

After patch embedding and before fusion with the SwinFpn backbone, an attention block refines the convolutional feature maps into attention-refined representations. Specifically, the block computes importance weights along channel and/or spatial dimensions to reweight original responses, preserving tensor shape while emphasizing knowledge-relevant and landslide-sensitive patterns and suppressing redundant background signals. Implemented modularly, different attention mechanisms share the same input–output interface and can be plugged in without altering the architecture. Section 4.5 systematically compares three representative instantiations—CBAM [26], SE [27], and ECA [28]—to select the optimal mechanism based on segmentation accuracy within the KGE–SwinFpn framework.

- (4)

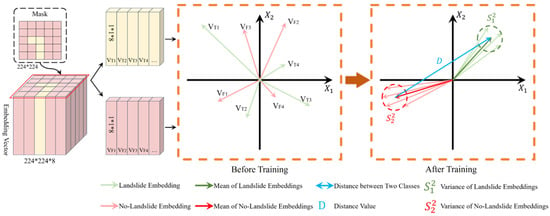

- Pretraining Strategy for KGE–SwinFpn

A pretrained KGE Block was integrated as the second branch of the KGE–SwinFpn model to enhance the distinction between landslide and no-landslide samples in the embedding space (Figure 5). The pretraining strategy optimizes the embedding distribution by simultaneously minimizing intra-class variances (S12 for landslide, S22 for non-landslide embeddings) and maximizing inter-class distance (D) between cluster centroids. Formally, the loss function is defined as:

Figure 5.

Pretraining strategy of the KGE Block.

This joint optimization compels tighter clustering within each class while pushing class centroids further apart, transforming initially overlapping distributions into well-separated, compact clusters. By balancing intra-class compactness with inter-class separability, the strategy significantly enhances representational capacity and discriminative performance, proving particularly effective for high-precision landslide segmentation tasks.

The pretrained KGE Block generates structured embeddings that seamlessly fuse with image features, boosting segmentation accuracy and robustness. Critically, after pretraining, the KGE Block’s node embedding weights remain frozen when integrated into the full KGE–SwinFpn network. This preserves the learned knowledge structure while subsequent training focuses exclusively on adapting the segmentation backbone, ensuring efficient knowledge transfer and preventing catastrophic forgetting during end-to-end fine-tuning.

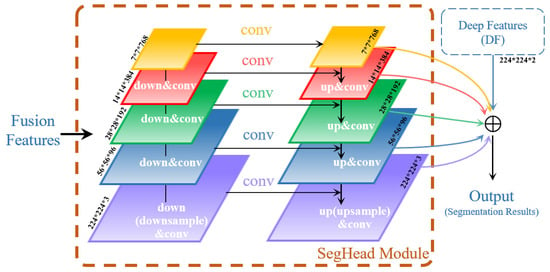

2.3. Segmentation Head Module

The SegHead Module (Figure 6) processes fusion features—generated by integrating multi-scale image features with knowledge-guided shallow features—through a hierarchical refinement pipeline. At each pyramid level, convolution and addition operations enhance local representation while preserving cross-scale information flow. Progressive upsampling then restores low-resolution deep semantic features to higher resolutions, fusing them sequentially with high-resolution shallow features to maintain spatial detail integrity. After aggregating multi-scale features across all pyramid levels, they are combined with deep features to generate final segmentation outputs, thereby integrating semantic knowledge throughout the entire feature hierarchy.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram illustrating the structure of the SegHead Module.

This hierarchical fusion strategy is essential for leveraging both local and global features to enhance multi-scale target recognition in complex terrain scenarios. In RS imagery, landforms exhibit significant scale variations, and landslide regions present diverse textures, shapes, and spatial distributions that challenge conventional single-scale approaches. The SegHead architecture enables low-level features to retain rich spatial details such as object boundaries, textures, and local shapes, while high-level features capture stronger semantic information including object categories and regional consistency. By progressively fusing multi-scale features with deep features through learnable parameters, the model constructs segmentation results that effectively integrate deep semantic understanding with fine-grained boundary information. This significantly improves segmentation accuracy and robustness, enhancing the model’s adaptability to complex terrain variations.

2.4. Focal Loss Function

In object detection tasks, the number of positive and negative samples is often highly imbalanced, with negative samples greatly outnumbering positive ones. This imbalance hinders model convergence and degrades performance. Conventional loss functions, such as Binary Cross Entropy (BCE) Loss, are ill-suited for such scenarios as it treats all samples equally, failing to emphasize hard-to-learn samples. Focal Loss [29] addresses this by introducing a modulation factor to BCE:

where αt balances positive/negative sample importance, and (1 − pt)γ serves as the modulation factor. When classification confidence pt approaches 1 (easy samples), the modulation factor tends toward 0, reducing their contribution to the total loss. This prevents the model from overemphasizing easily classified samples and focuses its learning on difficult, misclassified samples.

The γ parameter controls the attenuation rate, enabling fine-tuned sensitivity to hard samples. This is particularly crucial for landslide segmentation in RS imagery, where landslide regions (landslide regions) are spatially sparse compared to background areas (non-landslide regions). By dynamically reweighting samples based on classification difficulty, Focal Loss effectively mitigates class imbalance, enhancing model robustness and segmentation accuracy in complex terrain scenarios.

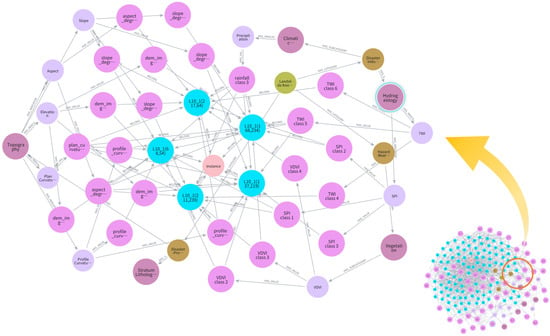

2.5. Landslide Knowledge Graph Construction

Two complementary datasets were curated: (1) a landslide disaster dataset comprising visible-light RS images with corresponding pixel-wise segmentation masks, and (2) a landslide knowledge dataset encoding geographic and climatic attributes (e.g., elevation, slope, aspect, planar/profile curvature, TWI, SPI, annual precipitation, VDVI, etc.) derived via RS processing techniques (Table 1). The Yuan-yang dataset served as the primary resource for training, validation, and testing, while the Bijie dataset independently validated model generalizability. While the disaster dataset provides direct landslide annotations, the knowledge dataset enriches the model with essential geological and environmental context crucial for complex terrain analysis.

Table 1.

Examples of Landslide Knowledge and Sources.

A landslide KG was constructed [31] (Figure 7) to formalize multi-dimensional relationships among disaster-prone environmental factors and causative mechanisms. Continuous variables (e.g., elevation, slope, precipitation, etc.) were discretized into ordered categorical classes, with each class represented as a distinct node. Inherently discrete variables (e.g., lithology, land-cover type, etc.) were directly encoded as category nodes. Each pixel was then linked to corresponding attribute nodes matching its local conditions (e.g., slope class, aspect, land-cover, etc.), establishing pixel–knowledge connections that convert domain expertise into computable features. This integration compensates for the limited environmental context in raw RS imagery, enabling the model to leverage both spatial-textural image features and geological/geographical knowledge for enhanced landslide identification. The graph centers on key triggering factors to explicitly model their causal interdependencies to provide structured domain knowledge, such as terrain attributes (e.g., elevation, slope, aspect), climatic variables (e.g., precipitation), and environmental characteristics (vegetation cover), etc.

Figure 7.

Landslide Knowledge Graph (KG) example.

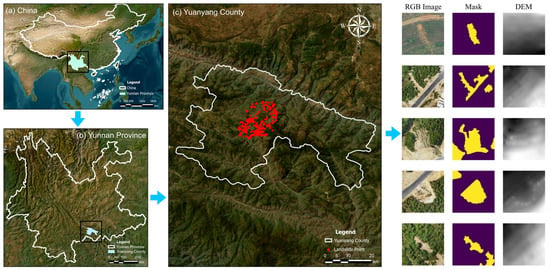

3. Study Area and Datasets

The primary study area, Yuan-yang County in Yunnan Province, China (23.22°N, 102.83°E), features rugged terrain with elevations from 144 m to 2939.6 m and a relative difference of 2795.6 m. Its steep, V-shaped valleys, variable slope morphology, and escarpments create favorable conditions for geological hazards such as landslides, collapses, and debris flows, with abundant loose materials accumulating in gullies. The spatial distribution of landslides in this region is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Landslide locations in the Yuan-yang Landslide Dataset. DEM, digital elevation model.

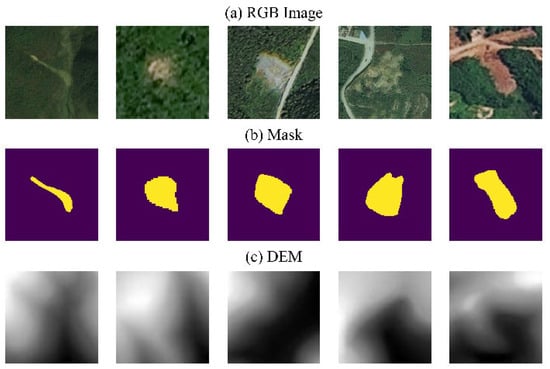

To verify the model’s adaptability across diverse topographic and remote sensing conditions, the Bijie Landslide Dataset [32] was employed for cross-regional validation. Covering several landslide-prone zones in Bijie City, Guizhou Province, this dataset features complex terrain, dense vegetation, and varied image resolutions, providing a robust test for the KGE–SwinFpn model’s segmentation accuracy and generalization in heterogeneous RS environments. Representative samples are shown in Figure 9, and experimental results demonstrate the model’s stability and applicability across multi-regional and multi-task RS scenarios.

Figure 9.

Samples from the Bijie Landslide Dataset.

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Experimental Environment

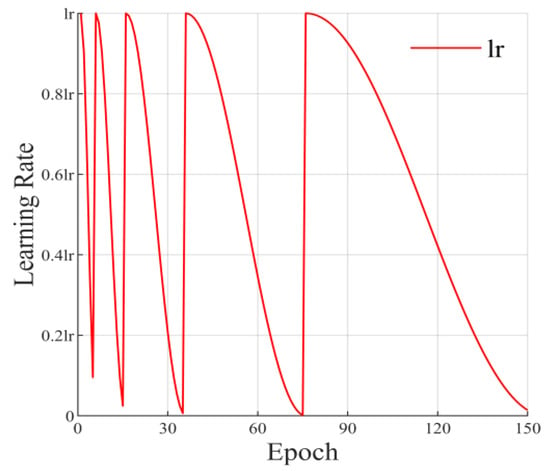

All experiments were conducted on a 64-bit Windows 11 system with an Intel i9-11900 K CPU, NVIDIA RTX 3080 Ti GPU, and 32 GB RAM. The implementation utilized Python 3.11, CUDA 12.3, and PyTorch 2.3.0. Models were trained on 224 × 224 pixels image patches for 150 epochs using Focal Loss and the Adam optimizer. The learning rate schedule employed Cosine Annealing Warm Restarts [33] (T_0 = 5, T_mult = 2), enabling periodic escapes from local minima followed by extended decay cycles for convergence (Figure 10). The checkpoint with the lowest validation loss was selected for final testing, ensuring a consistent and reproducible protocol across all model variants and ablation studies.

Figure 10.

Cosine Annealing Warm Restarts learning rate strategy.

The dataset splitting strategy is summarized in Table 2, both datasets were partitioned following an 8:1:1 ratio. The Yuan-yang dataset comprised 864 training, 108 validation, and 108 test samples, totaling 1080 images. The Bijie dataset, used for external generalization evaluation, contained 614 training, 77 validation, and 77 test samples, totaling 770 images.

Table 2.

Dataset Splitting Strategy.

To comprehensively evaluate the model’s segmentation performance, three standard metrics—pixel accuracy (PA), mean pixel accuracy (MPA), and mean intersection over union (MIoU)—were adopted [34]. PA measures overall classification accuracy but may be affected by class imbalance. MPA averages accuracy across all categories, mitigating imbalance bias, while MIoU emphasizes boundary precision and regional consistency, making it the most representative indicator for segmentation quality.

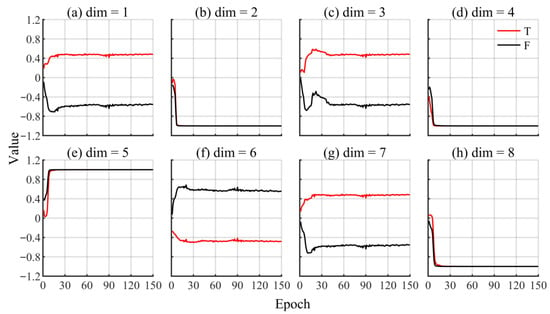

4.2. Knowledge Embedding Block Pretraining

Figure 11 illustrates the KGE Block’s pretraining dynamics across eight embedding dimensions (subplots a–h), with training epochs on the horizontal axis and embedding values on the vertical. Red and black solid lines represent landslide and non-landslide sample averages, respectively. Each subplot reveals distinct discriminative capacities. As training progresses, embedding values progressively diverge, evolving from initially overlapping distributions to well-separated, stable clusters—confirming the pretraining strategy’s effectiveness in enhancing class discrimination. Notably, dimensions 1, 3, 6, and 7 exhibit rapid divergence, demonstrating strong class separation capabilities, while remaining dimensions show minimal differentiation, indicating limited contribution to discriminative performance. This dimensional variation demonstrates that the KGE Block effectively encodes class distinctions across complementary feature subspaces, with each dimension capturing different aspects of landslide characteristics.

Figure 11.

KGE Block pretraining effect.

The pretraining strategy simultaneously learns positive–negative distinctions while reinforcing inter-class separability, establishing a robust embedding foundation. During subsequent KGE–SwinFpn joint training, these pretrained node embedding weights remain frozen, allowing downstream segmentation layers to adapt while preserving the learned knowledge structure. This significantly enhances overall segmentation accuracy and model robustness across diverse terrain conditions.

4.3. Learning Rate and Hyperparameters

The Adam optimizer with Cosine Annealing Warm Restarts was employed to optimize model convergence. We systematically investigated learning rate and batch size, the two hyperparameters most influential on performance. For learning rate (lr) analysis (batch size fixed at 2), Table 3 reveals optimal performance at lr = 2 × 10−4, achieving PA = 96.7%, MPA = 87.9%, and MIoU = 81.1%. This moderate rate enables stable convergence and effective landslide feature capture, whereas higher learning rates destabilized training, causing performance degradation. For batch size evaluation (lr fixed at 2 × 10−4), Table 4 demonstrates peak accuracy with batch size = 2, with deviations consistently reducing segmentation quality. According to Table 4, the SwinFpn model achieved its highest accuracy with a batch size of 2. Deviating from this optimal batch size resulted in a decline in segmentation accuracy. Both learning rate and batch size significantly affect the SwinFpn model’s performance in landslide segmentation. A well-balanced configuration enhances segmentation accuracy, facilitating more precise identification of landslide-prone areas. Based on these findings, we set the learning rate to 2 × 10−4 and the batch size to 2 for the final experiments.

Table 3.

Landslide Segmentation Performance of the SwinFpn Model under Different Learning Rates.

Table 4.

Landslide Segmentation Performance of the SwinFpn Model under Different Batch Sizes.

4.4. Comparison with Other Models

To systematically evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed KGE–SwinFpn model and quantify the contributions of the KGE Block, we conducted comprehensive comparative experiments on the Yuan-yang Dataset against state-of-the-art semantic segmentation networks: Segment Anything Model (SAM) [35,36], DeepLabV3+ [10], SwinUnet [37], PSPNet [38], and the landslide-specific LandsNet [39]. Additionally, to isolate the impact of our knowledge embedding design, we constructed two graph-based variants by replacing the KGE Block with a four-layer graph attention network (GAT) and a four-layer graph convolutional network (GCN), respectively, each with an embedding dimension of 128; these models are denoted as SwinFpn (GAT) and SwinFpn (GCN). For SAM, we adopted a partially fine-tuned configuration: the image encoder remained frozen, while the prompt encoder and mask decoder were fine-tuned on the training set. Point prompts were automatically generated from the ground-truth masks by taking the centroid of each connected landslide region and applying a random 10–30% offset constrained within mask boundaries. All models were trained under the same training regime for fair comparison. Table 5 summarizes the number of parameters (Params (M)) and the evaluation metrics—PA, MPA, and MIoU—for different models on the Yuan-yang Dataset.

Table 5.

Comparison of Landslide Segmentation Performance across Models on the Yuan-yang Dataset.

KGE–SwinFpn achieved the highest scores across all metrics, demonstrating superior segmentation accuracy, improved class balance, and enhanced regional consistency. Compared to SwinFpn (GAT) and SwinFpn (GCN), which already benefit from graph-based aggregation of attribute information, KGE–SwinFpn’s dedicated pretraining strategy yields a more organized embedding space, resulting in stable and precise segmentation. This confirms that integrating landslide domain knowledge effectively strengthens feature representation, significantly enhancing the model’s ability to segment complex landslide regions.

In contrast, while the original SwinFpn model maintains strong global feature representation, it exhibits limitations in capturing fine details. The SwinFpn (GAT) and SwinFpn (GCN) variants partially alleviate this issue by introducing explicit neighborhood aggregation on the knowledge attributes, but they still fall short of the overall performance and boundary consistency achieved by the pretrained KGE Block. Among the other classical models, DeepLabV3+ performed well in capturing global information, leading to satisfactory overall segmentation; however, it showed limitations in handling boundary details. SAM achieved an MPA comparable to that of KGE–SwinFpn but lagged behind in MIoU, indicating strong general segmentation capability yet limited adaptability to landslide-specific boundaries. SwinUnet, despite its advantage in local detail extraction, lacks sufficient global semantic representation in complex environments, resulting in reduced segmentation performance. PSPNet integrates multi-scale information reliably but faces challenges with small-scale landslides.

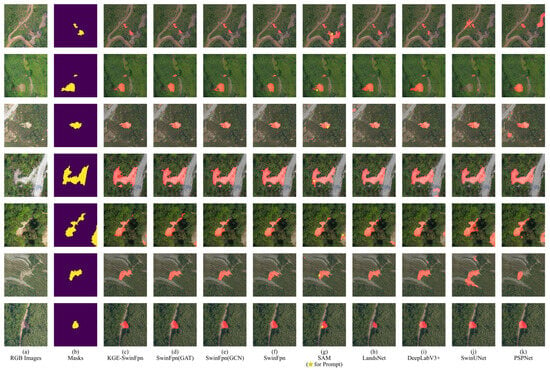

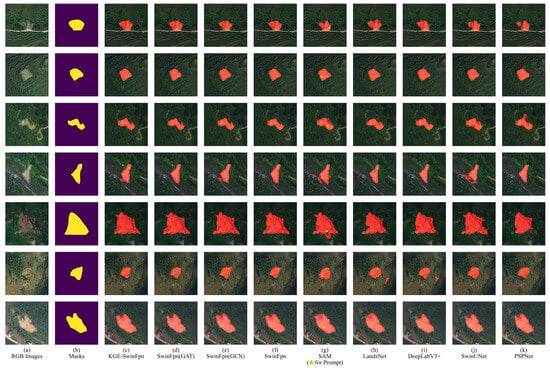

Overall, KGE–SwinFpn successfully balances global and local information through knowledge-embedding integration. Although MIoU improvement over baseline SwinFpn appears modest, qualitative analysis reveals substantial gains in boundary delineation precision and reduced omission of fragmented landslides. Figure 12 demonstrates that KGE–SwinFpn produces segmentations most faithful to ground truth, accurately delineating landslide boundaries while minimizing background misclassification. This underscores the critical importance of domain knowledge incorporation for advancing landslide detection accuracy. SwinFpn (GAT) and SwinFpn (GCN) generate plausible results with improved localization over baseline SwinFpn, yet they exhibit subtle boundary irregularities and omissions compared to KGE–SwinFpn’s more coherent outputs. Baseline SwinFpn shows minor edge omissions despite robust region identification. SAM demonstrates moderate boundary alignment but suffers from prompt-dependent under-segmentation and fragmentation. LandsNet delivers competitive performance with smooth region predictions in homogeneous areas, yet it tends to over-smooth boundaries and struggles with edge preservation in complex terrain, causing contour distortions and background leakage. DeepLabV3+ exhibits elevated false positives/negatives in complex backgrounds, reflecting limited fine-feature capture. SwinUnet and PSPNet similarly show deficiencies in segmentation completeness, particularly along ambiguous boundaries where landslides are under-segmented or misclassified.

Figure 12.

Landslide segmentation prediction results on the Yuan-yang Dataset.

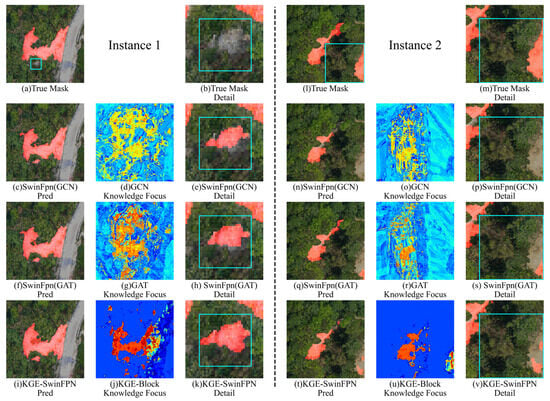

Figure 13 presents challenging scenarios comparing SwinFpn (GCN), SwinFpn (GAT), and KGE–SwinFpn predictions alongside “knowledge focus” visualizations. In low-contrast or vegetation-obscured areas, SwinFpn (GCN) and SwinFpn (GAT) produce under-segmented results with spatially diffuse focus maps, whereas KGE–SwinFpn yields coherent landslide shapes with cleaner boundaries, and knowledge responses concentrated within true landslide extent, effectively suppressing background regions. Although minor omissions persist in extremely difficult scenes, these comparisons indicate that the KGE Block provides more focused, interpretable guidance than standard GNN alternatives and leads to more structurally consistent segmentations in complex terrain.

Figure 13.

Visual illustration of segmentation details in complex terrain conditions.

Cross-region validation on the Bijie dataset (Table 6) further demonstrates KGE–SwinFpn’s robust generalizability, achieving consistently high PA, MPA, and MIoU scores that outperform baseline SwinFpn and match or exceed established methods. These results confirm that knowledge-guided components maintain superior performance across diverse geographic contexts, reinforcing the model’s practical utility for real-world landslide monitoring applications requiring accurate delineation across varied terrain conditions.

Table 6.

Comparison of Landslide Segmentation Performance across Different Models on the Bijie Dataset.

Figure 14 compares segmentation masks on Bijie dataset samples. KGE–SwinFpn demonstrates superior alignment with ground truth, particularly for irregular boundaries, diffuse textures, and dense vegetation. SwinFpn (GAT) and SwinFpn (GCN) improve upon baseline SwinFpn but exhibit slight boundary roughness and local omissions. SAM (ViT-B) generates prompt-sensitive predictions with occasional region omissions, while LandsNet over-smooths masks, compromising boundary precision in narrow or fragmented shapes. DeepLabV3+, SwinUnet, and PSPNet suffer from segmentation drift, fragmentation, or under-segmentation, especially in elongated or visually complex regions. These results confirm that domain knowledge integration enhances robustness and boundary preservation across geographically diverse and structurally heterogeneous terrains.

Figure 14.

Landslide segmentation prediction results on the Bijie Dataset.

In summary, from both the experimental results of Yuan-yang and Bijie datasets, KGE–SwinFpn consistently produces results aligned with ground truth across diverse conditions, highlighting the benefits of incorporating landslide-specific knowledge for achieving stable performance in varying geographic contexts.

4.5. Impact Analysis of Fusion Methods on Remote Sensing Landslide Segmentation

To evaluate the effectiveness of different feature fusion strategies for landslide segmentation on the Yuan-yang dataset, we conducted a series of comparative experiments assessing the contributions of shallow features (SFs), deep features (DF), and their fusion approaches. The results are summarized in Table 7. Specifically, two model variants were designed: KGE–SwinFpn without SF, which removes shallow features while retaining DF, and KGE–SwinFpn without DF, which eliminates deep features while keeping SF. The experiments elucidate the distinct roles of SF and DF in RS-based landslide segmentation.

Table 7.

Ablation Study: Impact of shallow and Deep Features Fusion in KGE–SwinFpn.

The experimental results indicate that removing either SF or DF degrades segmentation performance. The absence of DF notably reduces the model’s global semantic comprehension, underscoring its importance in capturing macro-level landslide characteristics. Without DF, the model fails to delineate accurate overall contours and internal semantic relations, leading to lower segmentation accuracy. In contrast, removing SF has a relatively smaller impact, though its role in fine-detail representation remains clear: SF enhances the model’s capacity to capture intricate structures, especially along boundaries, thereby refining segmentation outputs.

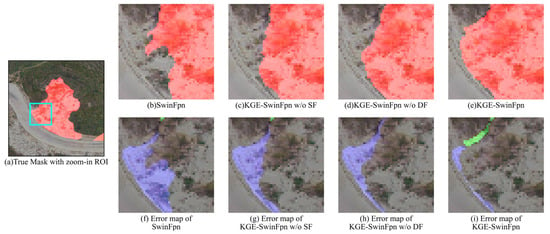

For further visualization, Figure 15 displays a zoomed region-of-interest alongside prediction and error maps for SwinFpn and its KGE-enhanced variants, where purple expressing false negatives and green indicating false positives. The baseline SwinFpn shows clear boundary deviations and local omissions along the landslide–road interface, corresponding to a broad error band. The variants retaining only SF or only DF partially mitigate these issues but still exhibit residual false positives and fragmented errors near edges. In comparison, the full KGE–SwinFpn model yields a segmentation mask that aligns closely with the ground-truth contour, and its error map displays a much thinner, more localized error region. This demonstrates that jointly leveraging SF and DF allows the model to better align landslide edges with geoenvironmental contexts, producing sharper boundaries and fewer misclassifications in transitional zones.

Figure 15.

Effect of Shallow and Deep Features on Landslide Boundary Segmentation (Purple: False Negatives, Green: False Positives, Cyan box: the ROI displayed in subfigures (b–i)).

Overall, these findings confirm the complementary nature of shallow and deep features. A well-designed fusion strategy enhances both global contextual understanding and local detail capture, showing strong potential for real-world applications—especially in multi-scale, complex-background segmentation where robustness and adaptability are critical.

To further evaluate the influence of attention mechanisms on landslide segmentation, we integrated three widely-used attention modules—Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) [26], Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) [27], and Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) [28]—into the KGE–SwinFpn framework. As summarized in Table 8, CBAM achieved the highest scores across all metrics (PA, MPA, MIoU). Its dual channel-spatial attention enables selective emphasis on semantically important features while enhancing structural detail, effectively balancing global context and local precision for segmenting landslides of diverse shapes and scales.

Table 8.

Comparison of Landslide Segmentation Performance Using Different Attention Mechanisms.

Based on Table 8, CBAM proved most robust by leveraging both global and local feature interactions, marginally outperforming SE and ECA. These results highlight the importance of attention in handling complex, multi-scale landslide segmentation, ultimately improving model generalization and practical utility. So that we adopt CBAM as the default Attention Block in the final KGE–SwinFpn framework.

4.6. Impact Analysis of Different Types of Knowledge on Remote Sensing–Based Landslide Segmentation

To systematically evaluate the contribution of individual knowledge features to landslide segmentation performance on the Yuan-yang Dataset, we performed ablation experiments by sequentially excluding each feature and analyzing its impact on accuracy. The tested features—slope aspect, elevation, planar curvature, profile curvature, precipitation, slope, SPI, TWI, and VDVI—collectively capture terrain morphology, climatic factors, and vegetation conditions relevant to landslides. Using the KGE–SwinFpn model, we assessed how removing each feature influences segmentation, with results presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Impact of Individual Knowledge Features on Landslide Segmentation Performance of KGE–SwinFpn.

The experiments reveal that excluding individual knowledge features variably degrades segmentation performance. Notably, removing elevation or slope causes a pronounced drop in MIoU, underscoring their importance in characterizing landslide shape and boundaries. These terrain attributes are closely linked to topographic variation in landslide-prone areas; their absence weakens the model’s capacity to delineate core landslide regions. Similarly, omitting hydrological features (SPI and TWI) leads to noticeable fluctuations in MPA, indicating their role in identifying zones susceptible to water accumulation and erosion. Without these indicators, segmentation accuracy in hydrologically sensitive areas declines. In contrast, excluding VDVI has minimal impact, suggesting vegetation cover offers limited predictive value in this context.

To further examine feature interactions, we grouped these attributes into three categories—terrain (aspect, elevation, slope, planar/profile curvature), hydrological (precipitation, SPI, TWI), and vegetation (VDVI)—and evaluated the effect of removing each group (Table 10). Results show that terrain feature removal causes the most substantial decline across all metrics, with MIoU decreasing by 6.5‰, confirming their central role in representing landslide morphology. Excluding hydrological features also leads to notable performance degradation, particularly in MPA, highlighting their relevance in discriminating moisture-affected areas. Vegetation removal again yields only minor changes, aligning with earlier observations.

Table 10.

Impact of Knowledge Feature Group Exclusion on Landslide Segmentation Performance of KGE–SwinFpn.

Overall, these ablation studies demonstrate that while individual contributions vary, terrain and hydrological features are essential for robust landslide segmentation. Their combined inclusion through knowledge-guided learning effectively enhances model accuracy and geospatial reasoning.

4.7. Generalization Analysis of the KGE Block

To evaluate the impact of KGE-Block on various segmentation models, we enhanced several representative landslide segmentation networks by integrating KGE-Block, testing their performance on the Yuan-yang dataset. The results (Table 11) show that KGE-Block consistently improves segmentation across all models.

Table 11.

Comparison of Landslide Segmentation Performance among Different Models.

Regardless of a model’s primary strength—global context modeling (DeepLabV3+), fine-detail preservation (SwinUnet), or multi-scale fusion (PSPNet)—KGE-Block boosts accuracy, detail recovery, and output consistency. In DeepLabV3+, KGE-Block aids semantic identification in complex terrain; in SwinUnet, it refines boundary delineation; and in PSPNet, it strengthens multi-scale feature integration. Overall, KGE-Block enhances both adaptability and generalization across architectures, effectively compensating for individual network limitations. These findings validate the broad utility of KGE-Block in remote-sensing landslide segmentation and offer insights for designing more robust models.

5. Discussion

The proposed KGE–SwinFpn model addresses the limitations of purely data-driven landslide detection by integrating knowledge graph embedding with a deep segmentation backbone. It explicitly links RS image patterns to underlying failure mechanisms by incorporating domain knowledge (e.g., lithology, terrain, land cover, triggering factors, etc.) into the feature learning process, moving beyond reliance on spectral–spatial similarity alone. This knowledge-guided design enhances interpretability and aligns the decision process with expert understanding of landslide formation.

Unlike previous landslide models that employ knowledge graphs at slope-unit or catchment scales and often couple them with traditional classifiers, our approach operates at pixel level and integrates knowledge directly into a modern encoder–decoder architecture via a dedicated branch. Experimental results on Yuan-yang and Bijie datasets demonstrate that KGE–SwinFpn consistently outperforms CNN-based, Transformer-based, and landslide-specific models in PA, MPA, and MIoU under the same training conditions.

Nevertheless, the method has several limitations. First, the performance gain depends heavily on the availability, quality, and coverage of the underlying knowledge graph; in data-sparse regions, knowledge embeddings may introduce bias or offer little discriminative benefit. Second, the current implementation focuses on static pre-failure conditions and does not explicitly model temporal dynamics such as rainfall sequences or seismic triggers, limiting its use for real-time warning or post-event assessment. Third, the embedding and fusion processes increase computational overhead compared to purely RS image-based models, which may constrain large-scale or real-time deployment without further optimization.

6. Conclusions

This study proposes KGE–SwinFpn, a deep learning model for landslide segmentation based on knowledge graph embedding. By integrating a landslide knowledge graph into the segmentation framework, the model effectively couples intrinsic landslide mechanisms with remote sensing observations and aligns knowledge graph features with image features via a dedicated KGE Block. Experimental results on the Yuan-yang and Bijie datasets demonstrate that KGE–SwinFpn consistently outperforms the SwinFpn baseline as well as several mainstream segmentation models, achieving PA = 96.85%, MPA = 88.46%, MIoU = 82.01% on Yuan-yang dataset, and PA = 96.28%, MPA = 90.72%, MIoU = 84.47% on Bijie dataset, which reflects its strong cross-regional generalization capability.

Compared with methods that rely mainly on spectral–spatial information, the proposed approach depends on the quality and coverage of the knowledge graph, and its transferability to globally diverse environments and extreme conditions require further validation. Additionally, the extra embedding and fusion operations increase computational cost, which may limit real-time applications. Future work will focus on evaluating the model on globally distributed datasets, integrating temporal and triggering factors (e.g., rainfall, seismicity), and developing lightweight implementations to support operational early-warning systems. These efforts aim to advance KGE–SwinFpn into a widely applicable framework for knowledge-guided landslide risk monitoring and management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z. and X.Z. (Xiangyu Zhao); methodology, X.Z. (Xiangyu Zhao); software, C.Z. and X.Z. (Xiangyu Zhao); validation, C.Z., X.Z. (Xiangyu Zhao), Y.P. and C.L.; formal analysis, C.Z. and X.Z. (Xiangyu Zhao); investigation, C.Z. and X.Z. (Xiangyu Zhao); resources, C.Z., P.Y., X.Z. (Xueying Zhang) and M.W.; data curation, X.Z. (Xiangyu Zhao), C.L. and Y.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Z. and X.Z. (Xiangyu Zhao); writing—review and editing, C.Z. and X.Z. (Xiangyu Zhao); visualization, X.Z. (Xiangyu Zhao); supervision, C.Z., P.Y., X.Z. (Xueying Zhang) and M.W.; project administration, C.Z. and X.Z. (Xueying Zhang); funding acquisition, C.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42171453) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. JZ2024HGTG0288).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The source code used in this study is publicly available at: https://github.com/ZhaoFyin/KGE_Swin_Fpn (accessed on 22 October 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their detailed and constructive comments and suggestions, which greatly helped in improving the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Samia, J.; Temme, A.; Bregt, A.; Wallinga, J.; Guzzetti, F.; Ardizzone, F.; Rossi, M. Do landslides follow landslides? Insights in path dependency from a multi-temporal landslide inventory. Landslides 2017, 14, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Xiong, H.; Jiang, S.-H.; Yao, C.; Fan, X.; Catani, F.; Chang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Huang, J.; Liu, K. Modelling landslide susceptibility prediction: A review and construction of semi-supervised imbalanced theory. Earth Sci. Rev. 2024, 250, 104700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deijns, A.A.; Michéa, D.; Déprez, A.; Malet, J.-P.; Kervyn, F.; Thiery, W.; Dewitte, O. A semi-supervised multi-temporal landslide and flash flood event detection methodology for unexplored regions using massive satellite image time series. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 215, 400–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, B.; Ercanoglu, M. Landslide identification and classification by object-based image analysis and fuzzy logic: An example from the Azdavay region (Kastamonu, Turkey). Comput. Geosci. 2012, 38, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drăguț, L.; Csillik, O.; Eisank, C.; Tiede, D. Automated parameterisation for multi-scale image segmentation on multiple layers. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 88, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghuis, A.; Chang, K.; Lee, H. Comparison between automated and manual mapping of typhoon-triggered landslides from SPOT-5 imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2007, 28, 1843–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, W.; Pun, M.-O.; Shi, W. Cross-domain landslide mapping from large-scale remote sensing images using prototype-guided domain-aware progressive representation learning. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 197, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakogiannis, F.I.; Waldner, F.; Caccetta, P.; Wu, C. ResUNet-a: A deep learning framework for semantic segmentation of remotely sensed data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 162, 94–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; He, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yao, S.; Yang, W.; Fang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gao, B. A landslide extraction method of channel attention mechanism U-Net network based on Sentinel-2A remote sensing images. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 552–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-H.; Shi, A.-C.; Xiao, H.-X.; Niu, Z.-H.; Jiang, N.; Li, H.-B.; Hu, Y.-X. Robust Landslide Recognition Using UAV Datasets: A Case Study in Baihetan Reservoir. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Chen, F.; Wang, L.; Zhao, H.; Yu, B. Swin Transformer-Based Multiscale Attention Model for Landslide Extraction From Large-Scale Area. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4415314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Wang, Z.; Huang, C.; Yang, Y.; Hu, J.; Yan, X.; Tan, Y.; Liao, L.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; et al. Advances in Deep Learning Recognition of Landslides Based on Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, G.; Janowicz, K.; Hu, Y.; Gao, S.; Yan, B.; Zhu, R.; Cai, L.; Lao, N. A review of location encoding for GeoAI: Methods and applications. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2022, 36, 639–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, A.; Blomqvist, E.; Cochez, M.; D’amato, C.; De Melo, G.; Gutierrez, C.; Kirrane, S.; Gayo, J.E.L.; Navigli, R.; Neumaier, S.; et al. Knowledge graphs. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ye, P. Geoscience Knowledge Graph (GeoKG): Development, construction and challenges. Trans. GIS 2022, 26, 2480–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Luo, P.; Cui, W.; Xia, C.; Xu, X.; Feng, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Xun, W.; Chen, C. Geographical Scenario Knowledge-Informed Graph Structure Attention for Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4401016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, L.; Wang, J.; Chen, J. DKDFN: Domain Knowledge-Guided deep collaborative feature network for zero-shot remote sensing image scene classification. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 186, 170–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kong, D.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, Y.; Chen, L. Robust deep alignment network with remote sensing knowledge graph for zero-shot and generalized zero-shot remote sensing image scene classification. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 179, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Yao, M.; Hao, Y.; Wang, Z.; He, X.; Wu, W.; Li, J.; Zhao, H.; Xia, C.; Wang, J. Knowledge and Geo-Object Based Graph Convolutional Network for Remote Sensing Semantic Segmentation. Sensors 2021, 21, 3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; He, X.; Yao, M.; Wang, Z.; Hao, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, W.; Zhao, H.; Xia, C.; Li, J.; et al. Knowledge and Spatial Pyramid Distance-Based Gated Graph Attention Network for Remote Sensing Semantic Segmentation. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Zhang, C.; Liu, W.; Huang, J.; Su, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Sun, W. Landslide identification method based on the FKGRNet model for remote sensing images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, G.; Janowicz, K.; Cai, L.; Zhu, R.; Regalia, B.; Yan, B.; Shi, M.; Lao, N. SE-KGE: A location-aware knowledge graph embedding model for geographic question answering and spatial semantic lifting. Trans. GIS 2020, 24, 623–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; He, Y.; Zhang, L.; Lu, J.; Gao, B.; Yang, W.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y. A landslide susceptibility assessment method considering the similarity of geographic environments based on graph neural network. Gondwana Res. 2024, 132, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16×16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.; Li, P.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q. ECA-Net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11534–11542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.02002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, A.M.; Gomes, R.; Schwartz, D.M.; Franzen, D.W. Large-Window Curvature Computations for High-Resolution Digital Elevation Models. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 3000620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, B.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Chu, C.; Zhou, K. Enhancing semantic accuracy in geographic knowledge graph embeddings through temporal encoding. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2025, 39, 2126–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Yu, D.; Shen, C.; Li, W.; Xu, Q. Landslide detection from an open satellite imagery and digital elevation model dataset using attention boosted convolutional neural networks. Landslides 2020, 17, 1337–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutter, I.L.F. SGDR: Stochastic gradient descent with warm restarts. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1608.03983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yuan, H.; Fu, T.; Yu, Z.; Zheng, B.; Chen, S. Multispectral semantic segmentation for UAVs: A benchmark dataset and baseline. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1002117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.Y.; et al. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 4015–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wei, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, Z. A feature fusion method on landslide identification in remote sensing with Segment Anything Model. Landslides 2025, 22, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q.; Wang, M. Swin-Unet: Unet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid scene parsing network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2881–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Zhang, W. A new deep-learning-based approach for earthquake-triggered landslide detection from single-temporal RapidEye satellite imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 6166–6176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.