Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Real-time PPP using multi-GNSS (GPS, Galileo, and BDS3) effectively retrieves precipitable water vapor with consistent performance across multiple analysis centers.

- Integrating multi-GNSS observations significantly improves the stability and reliability of ZTD estimation and PWV retrieval compared with single-system solutions.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The performance of ZTD and PWV retrieval are better than 11 mm and 3.5 mm, respectively, meeting the precision requirements for meteorological applications.

Abstract

Precipitable water vapor (PWV) is an important component of atmospheric spatial parameters and plays a vital role in meteorological studies. In this study, PWV retrieval by real-time precise point positioning (PPP) technique is validated by using global navigation satellite system (GNSS) observations and four real-time products from different analysis centers, which are Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES), Internation GNSS Service (IGS), Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), and Wuhan University (WHU). To comparatively analyze the performance of each scenario, the single-system (GPS/Galileo/BDS3), and multi-system (GPS + Galileo + BDS) PPP techniques are applied for zenith tropospheric delay (ZTD) and PWV retrieval. Then, the ZTD and PWV are evaluated by comparison with the IGS final ZTD product, the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) Reanalysis v5 (ERA5) data, and radiosondes observations provided by the University of Wyoming. Experimental results demonstrate that the root mean squares error (RMS) of ZTD differences from multi-system solutions are below 11 mm with respect to the four-product series and the RMS of PWV differences are below 3.5 mm. As for single-system solution, the IGS real-time products lead to the worst accuracy compared with the other products. Besides the scenario of BDS3 observations with IGS real-time products, the RMS of ZTD differences from the GPS-only and Galileo-only solutions are all less than 15 mm compared to the four-product series, as well as the RMS of PWV differences is under 5 mm, which meets the accuracy requirement for GNSS atmosphere sounding.

1. Introduction

As an important parameter in meteorology and climate research, precipitable water vapor (PWV) is of great significance for weather forecasting, climate monitoring, and extreme weather warning. In 1992, Bevis et al. proposed a method for retrieving atmospheric precipitable water using Global Positioning System (GPS), laying the theoretical foundation for Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) meteorology [1,2]. Compared with traditional water vapor radiometers and radiosondes, GNSS meteorology has gradually become an important means of meteorological observations due to its advantages of continuous operation, high accuracy, and low cost [3,4,5,6]. The further study of the troposphere delay modeling is carried out, which provides a new theory troposphere modeling for subsequent studies [7,8,9,10].

After the construction of the ground-based GNSS network, ground-based GNSS retrieval of PWV also became a research hotspot [11,12,13]. Zhao et al. analyzed PWV trends based on GNSS and ERA5 data in North America, which revealed that mean PWV generally remains under 20 mm in most areas, exceeding this threshold primarily in the Southeast [14]. Zhang et al. reported a mean PWV precipitation correlation coefficient of 0.73 by Chinese stations derived from ground-based GPS observations, which shows a significant positive correlation between monthly PWV mean content and precipitation measurements [15]. GPS retrieval of PWV has subsequently been widely used in meteorology, numerical weather prediction (NWP) and extreme weather events [16,17,18].

In addition, although the accuracy of zenith tropospheric delay (ZTD) estimation and PWV retrieval with precise point positioning (PPP) technique is sufficiently high, certain latency exists due to the acquisition of precise satellite orbit and clock products [19,20]. And, in GNSS meteorology, it is especially critical to ensure that the data are sufficiently real-time. Therefore, research on ZTD estimation and PWV retrieval using real-time products has attracted more attention [21,22,23].

Since the International GNSS Service (IGS) launched its real-time service in 2013 [24], related scholars conducted experiments on real-time retrieval of GPS PWV and used for precipitation monitoring and forecasting. Yuan et al. evaluated the accuracy of real-time GPS ZTD and PWV estimation and compared the results with IGS tropospheric products and radiosonde data, which shows the RMS values less than 13 mm and 3 mm, respectively [25]. Similarly, Shi et al. analyzed two rainfall cases using real-time GPS PPP technique to verify the feasibility of this technique in the PWV retrieval for precipitation detection [26]. The advent of multi-GNSS brings new opportunities for GNSS meteorology. After the completion of the BeiDou satellite navigation System (BDS2), Lu et al. obtained PWV accuracy of 1.3–1.8 mm based on real-time GPS and BDS observations [27].

Subsequently, various analysis centers, such as Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES), Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), and Wuhan University (WHU), have been able to launch multi-system real-time precise products [28]. In the meantime, the Galileo and the third generation of BDS (BDS3) have experienced major upgrades [29,30]. Numerous scholars have conducted experienced on zenith wet delay (ZWD) estimation of real-time PPP and PWV retrieval by using multi-system GNSS observations [31,32,33,34]. Ding et al. established a modified version of the PPP with integer and zero-difference ambiguity resolution demonstrator (PPP-WIZARD) to estimate real-time GNSS ZTD, which shows the average accuracy of the ZTD estimation can reach about 8 mm [35]. Wang et al. evaluated the ZTD estimation from BDS3 PPP-B2b service and compared it to the IGS tropospheric final product with the RMS values approaching 15 mm, which is inferior to ZTD estimation from the CNES final product [36]. In addition, researchers and scholars also conducted ZTD estimation experiments by using the state-space representation (SSR) real-time product. Zhou et al. utilized BDS PPP-B2b, Galileo HAS, and QZSS MADOCA-PPP services to estimate real-time ZTD and compared with IGS final ZTD, which had the standard deviations (STD) of 20.0 mm, 17.5 mm, and 9.5 mm, respectively [37]. Yao et al. evaluated the real-time positioning performance using GPS, Galileo, and BDS3 observations, as well as their ZTD estimation accuracy, using the SSR products from CAS, GMV, CNES, and WHU analysis centers, respectively, which shows the highest RMS accuracy of 6.06 mm with WHU [38].

The above studies have shown that the ZTD estimation and PWV retrieval from single-system PPP have sufficient accuracy, but studies about BDS3 real-time PWV retrieval are still deficient. To verify the accuracy of BDS-only and GNSS real-time PWV retrieval, in this research, real-time products from four analysis centers, which are CNES, IGS, JAXA, and WHU utilized to perform real-time PPP for the ZTD estimation. The GPS-only, Galileo-only, BDS3-only, and GPS + Galileo + BDS observations, which are chosen from 32 MGEX stations around the world, are utilized in the PPP processing. Finally, the ZTD estimations and PWV retrieval are evaluated by comparing with the IGS final ZTD product, the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) Reanalysis v5 (ERA5) data, and radiosondes provided by the University of Wyoming.

This paper is organized as follows: followed by the introduction in Section 1, Section 2 describes the basic methodology of PPP for ZTD estimation and PWV retrieval, as well as the methodology for PWV calculation from radiosonde data and adjusting ECMWF meteorological information. Section 3 evaluates the accuracy of real-time precise products from different analysis centers. Then, in Section 4, the estimated ZTD from different PPP solutions are compared with the IGS final ZTD products, and finally, the PWV are retrieved and compared with the ERA5 and the radiosonde data, respectively. A summary of this study is described in Section 5.

2. Methods

2.1. Precise Clock Product Evaluation Through All-Satellite Reference Method

Different analysis centers (ACs) introduce distinct reference benchmarks (i.e., timescales) when estimating satellite clock offsets, resulting in a systematic constant bias between their products. To address this issue, the all-satellite reference method is employed. This method forms single-differenced precise clock products between each AC and a designated reference AC to eliminate this system bias. This procedure allows us to establish a unified and stable datum for evaluating the precision of real-time clock products from different GNSS (GPS, BDS, Galileo) and, ultimately, to provide high-quality clock corrections for our multi-GNSS PPP. Then, taking the average of single differences from all visible satellites on the current epoch as the reference to make the double-differenced calculation. The formula can be expressed as [39]

where is the epoch and is the satellite; is the double-differenced clock correction between two different analysis centers; and are the clock correction from pending evaluation and reference analysis center; is the average of single differences; is the number of satellites.

2.2. PWV Retrieval from PPP Technique

The satellite signal is affected by the ionosphere and troposphere to produce a certain delay when it passes through the atmosphere, and the tropospheric delay could be estimated in PPP technique. The raw pseudorange and phase [40]:

where is the distance from the satellite to the receiver; and are the receiver clock bias and satellite clock bias, respectively; is the tropospheric delay; is the ionospheric delay at the first frequency; and is the conversion factor of the ionosphere from frequency to the first frequency ; and is the ambiguity at the frequency ; , and , are the hardware delays of the receiver and satellite code and carrier phases in the unit of meters, respectively; while and refer to the receiver and satellite; and are the unmodeled errors such as multipath, observation noise, etc., on the pseudorange and carrier phase, respectively. Other errors corrected using empirical models are not listed, including relativistic effects, solid tides, antenna phase center correction, etc.

Other errors such as antenna phase center corrections and phase-windup effects were corrected using conventional models. In the stochastic model, an elevation-dependent weighting strategy was applied to the observations: the standard deviations for carrier-phase and pseudorange measurements were set to 0.003 m and 0.3 m, respectively, and weighted by the reciprocal of the square of the sine of the elevation angle. Among the estimated parameters, the receiver clock correction was estimated as white noise, and the ambiguity parameters were estimated as constants. The zenith tropospheric delay (ZTD) was estimated as a random walk process with a process noise set to 0.1 mm/sqrt(s).

Since receiver clock corrections and hardware delays are not separable, satellite clock corrections are estimated from combined ionosphere-free observations. Thus, the satellite clock products are biased by the effect of the satellite pseudorange hardware delay apart from satellite clock correction [41]; that is,

where is an externally precise satellite clock correction and is a combination of satellite pseudo-ranging hardware delays. After parameter reformulation, the observation equation is as follows [41]:

and are the pseudorange and carrier observations of the ionosphere-free combination, respectively. and are the reparameterized receiver clock offsets and ambiguity parameters, respectively. Specifically expressed as , and .

The tropospheric delay is modeled as the product of the zenith direction and their projection functions. The zenith direction delay can be categorized into zenith hydrostatic delay (ZHD) caused by gases in hydrostatic equilibrium and ZWD caused by gases in non-hydrostatic equilibrium [42]. ZHD can be obtained from the Saastamonien empirical model [43]:

where , , are all constants taken as , , ; and denote the latitude and height of the station, respectively; P is the surface air pressure. ZWD can be obtained from the difference between ZTD and ZHD:

PWV is obtained by calculating ZWD and conversion factor according to Equation (7):

The conversion factor is a function of the weighted average temperature:

where is the density of liquid water; is the water vapor gas constant ; is the molar mass of wet atmosphere, which is taken as ; is the molar mass of dry atmosphere, take ; , , and are physical constants, which are taken as , , and , respectively.

can be calculated from meteorological data of ECMWF [44]. is the water vapor pressure, is the temperature; is the height of GNSS station.

2.3. PWV Retrieval from Radiosonde Data

The University of Wyoming collects and organizes and publishes radiosonde data from observatories around the globe, available for download at (University of Wyoming Atmospheric Science Radiosonde Archive). The time resolution is 12 h, which includes information on altitude, barometric pressure, temperature, and dew point temperature.

First, the water vapor pressure (in hPa) at each altitude is calculated from the measured dew point temperature at each altitude, calculated as

where is the atmospheric temperature (in ). When , , ; , , .

The specific humidity can be calculated from the measured barometric pressure at each altitude and the water vapor pressure calculated in Equation (11):

In turn, the PWV is calculated:

Prior to comparison, the radiosonde-PWV (RS-PWV) was normalized to the PWV value at the station height by interpolation [45]:

and are the at the and , respectively, where and denote the geometric height of the GNSS station and the radiosonde launch site.

2.4. Adjustment of Meteorological Data

The ECMWF dataset provides temperature and pressure data at specific elevations for grid points. These data need to be harmonized on the same elevation datum before they can be used. Temperature data can be adjusted according to the following linear equations [46]:

where and are the temperatures at the GNSS station and ECMWF reference level in Kelvin, and are the geodetic height of GNSS station and the ECMWF reference level. In this paper, we use the mean sea level pressure from the ECMWF dataset, and the pressure can be adjusted according to the following equation [47]:

where and are the barometric pressure and the mean sea level pressure at the GNSS station, respectively. Due to ECMWF, it provides the mean sea level pressure, which has to be converted to barometric pressure in subsequent experiments. is the geopotential height of the GNSS station. The ECMWF reanalysis data refers to geopotential heights. Therefore, it is necessary to take into account the conversion between the various elevation systems and then interpolate the adjusted data to the GNSS station positions according to the inverse distance weighted (IDW) interpolation.

3. Results and Analysis

In this section, four real-time precise satellite orbit and clock products, which are from analysis center of CNES, IGS, JAXA, and WHU, are selected for analysis over the duration of day of year (DOY) 214–243, 2024. Meanwhile, the final precise product provided from Center for Orbit Determination in Europe (CODE) was selected as the reference. It should be clearly noted that, to ensure the continuity of experiment data, the real-time products are not real-time SSR streams, but instead, are saved in sp3 format with special latency, which can be downloaded from ftp of each analysis center.

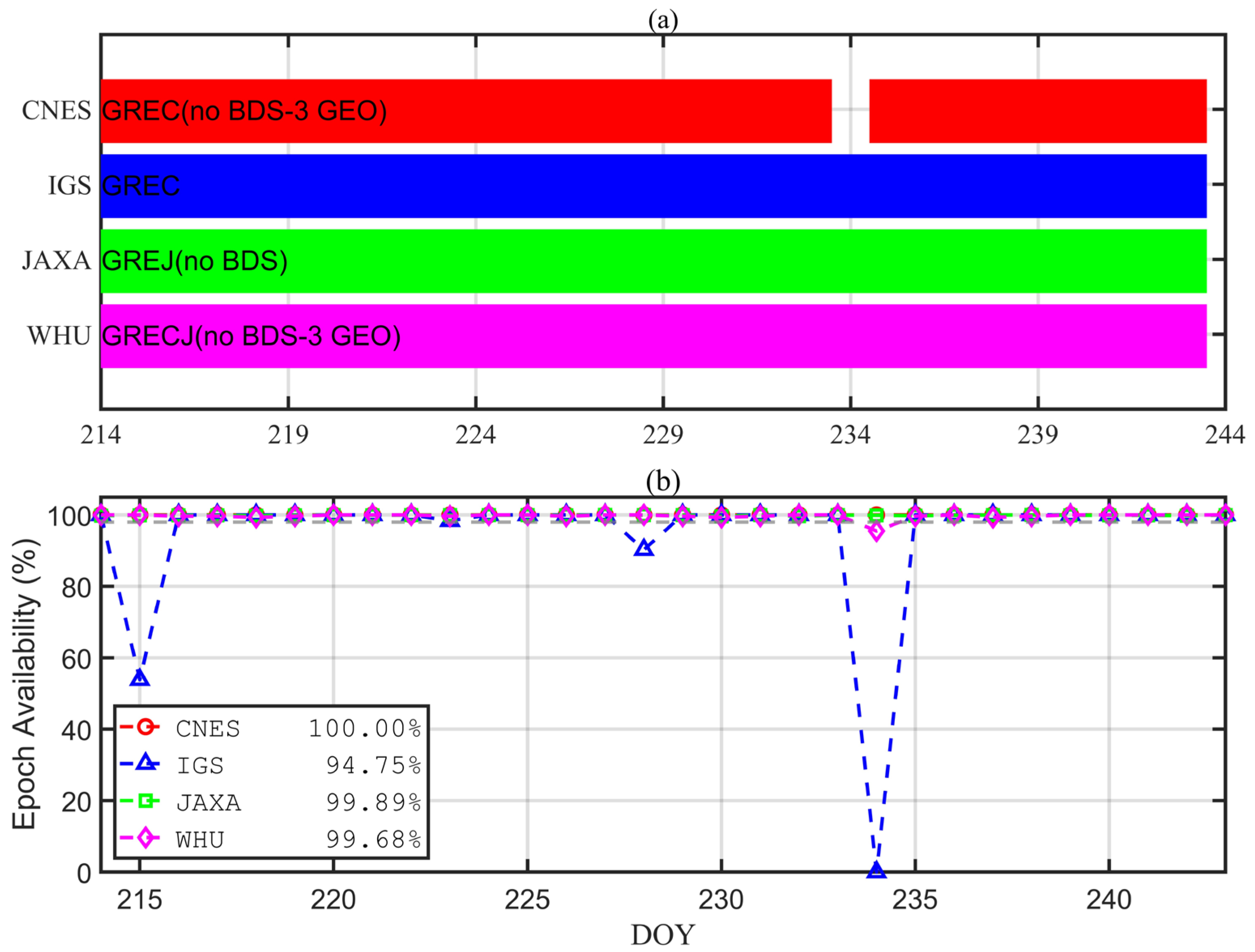

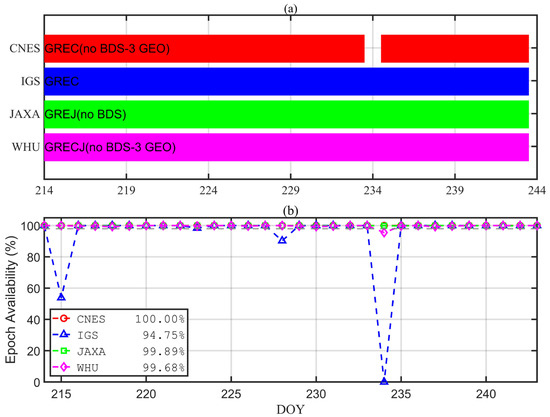

The product availability of the four analysis centers is shown in Figure 1, which shows that BDS3 GEO satellites are missing in the products of CNES and WHU, and the entire BDS3 satellite is missing in the products of JAXA. Over the duration of 30 days, the products of CNES, JAXA, and WHU have data completeness above 95% for each day, and the products from IGS are with only 53% completeness at DOY215 and one day missing at DOY234. While the overall product availability and data completeness of the four analysis centers were high, with 30-day average data completeness of 100%, 94.75%, 99.89%, and 99.68% for CNES, IGS, JAXA, and WHU, respectively. Since the BDS products are not included in the JAXA center, only the products of CNES, IGS, and WHU are processed in BDS3-only and multi-system PPP experiments.

Figure 1.

Product availability at four analysis centers. (a) Data availability of different analysis centers products in DOY214-243; (b) Data availability rate of different analysis centers products in DOY214-243.

3.1. Precise Product Evaluation from Different Analysis Center

3.1.1. Precise Orbit Product Evaluation

In this part, the accuracy of precise orbit products from four analysis centers are validated by comparing with the reference products. The average RMS value of GPS, Galileo, and BDS real-time orbits are evaluated in the satellite orbital coordinate system in radial (R), along (A), and cross (C) directions.

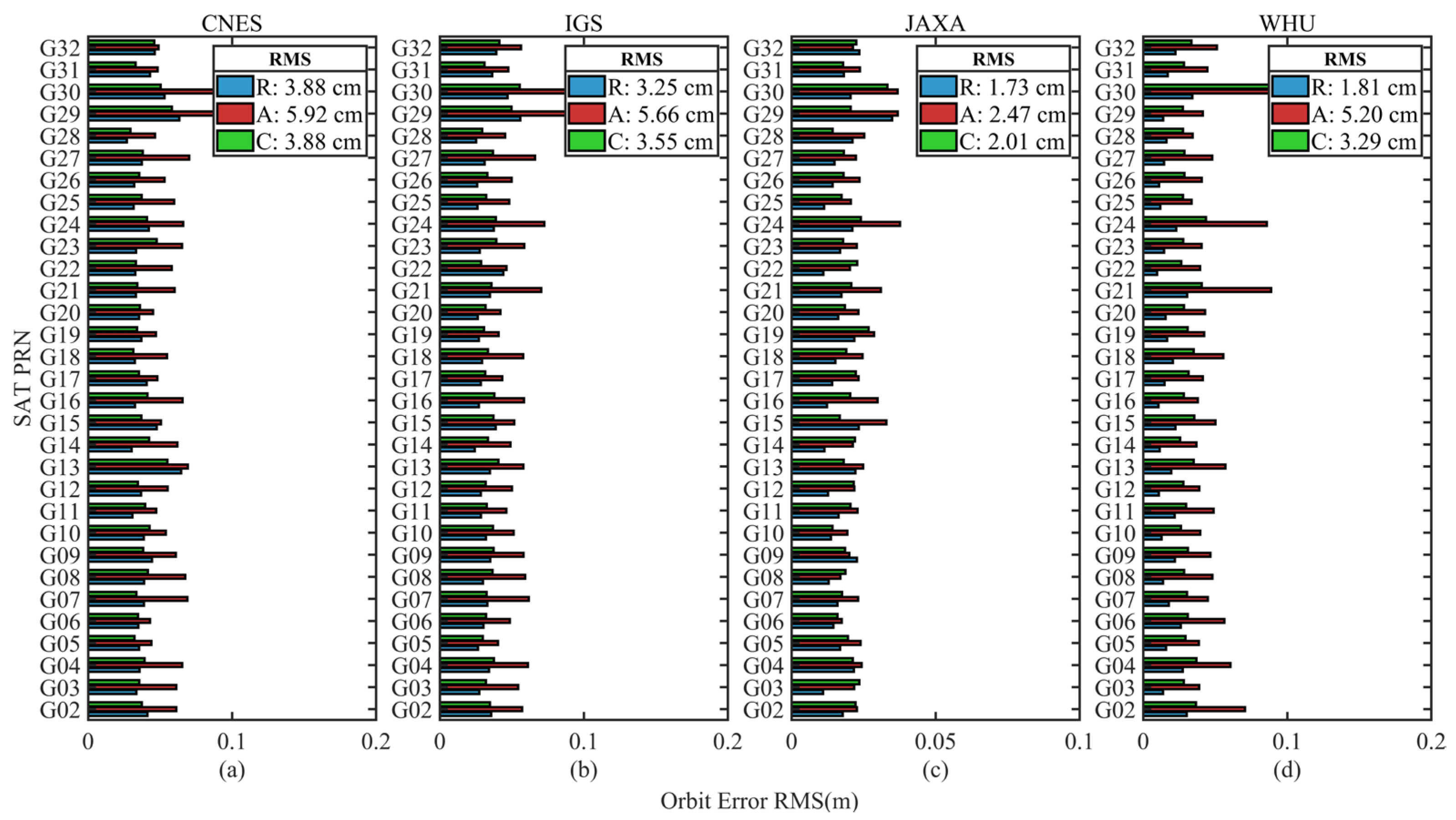

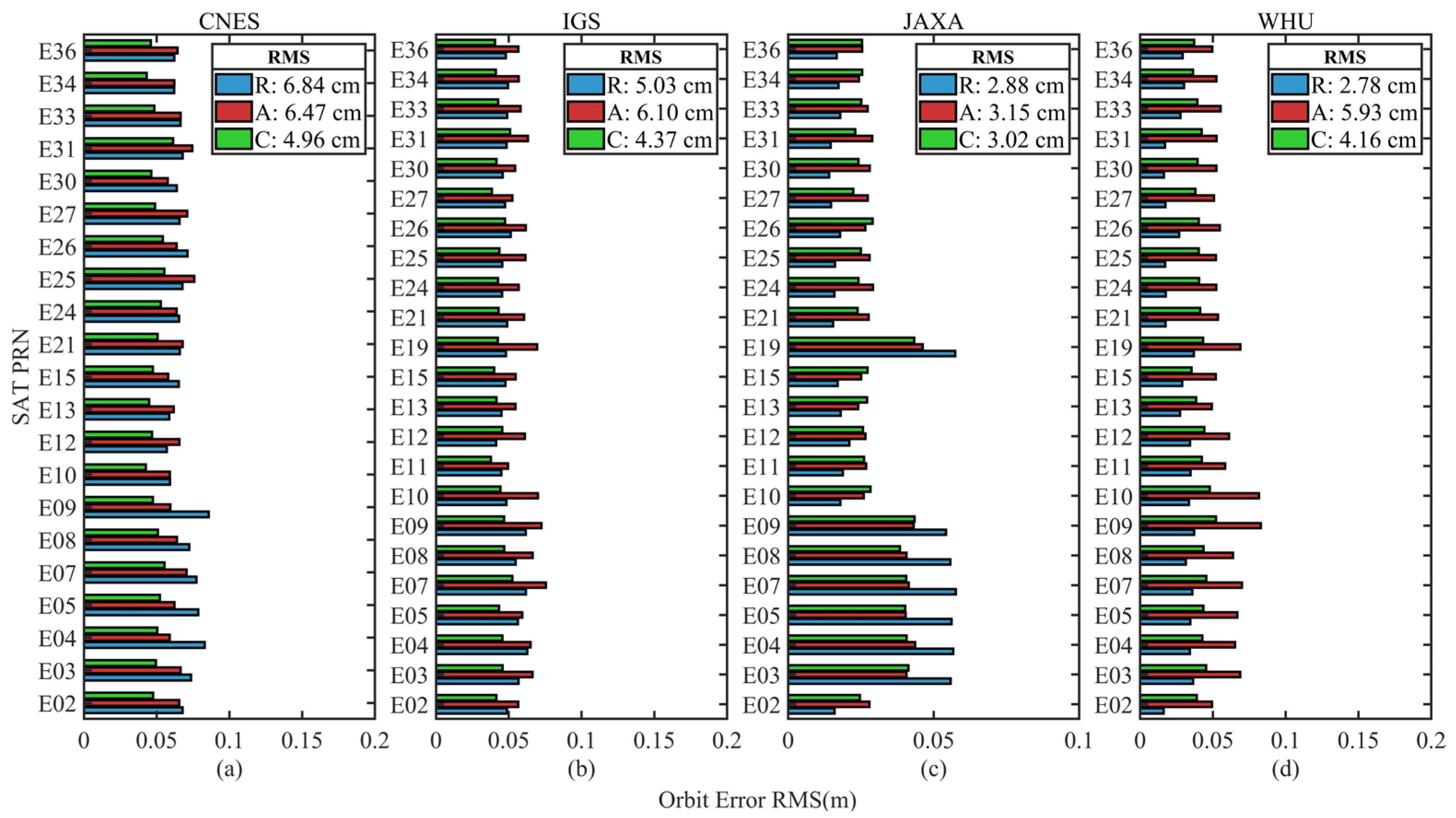

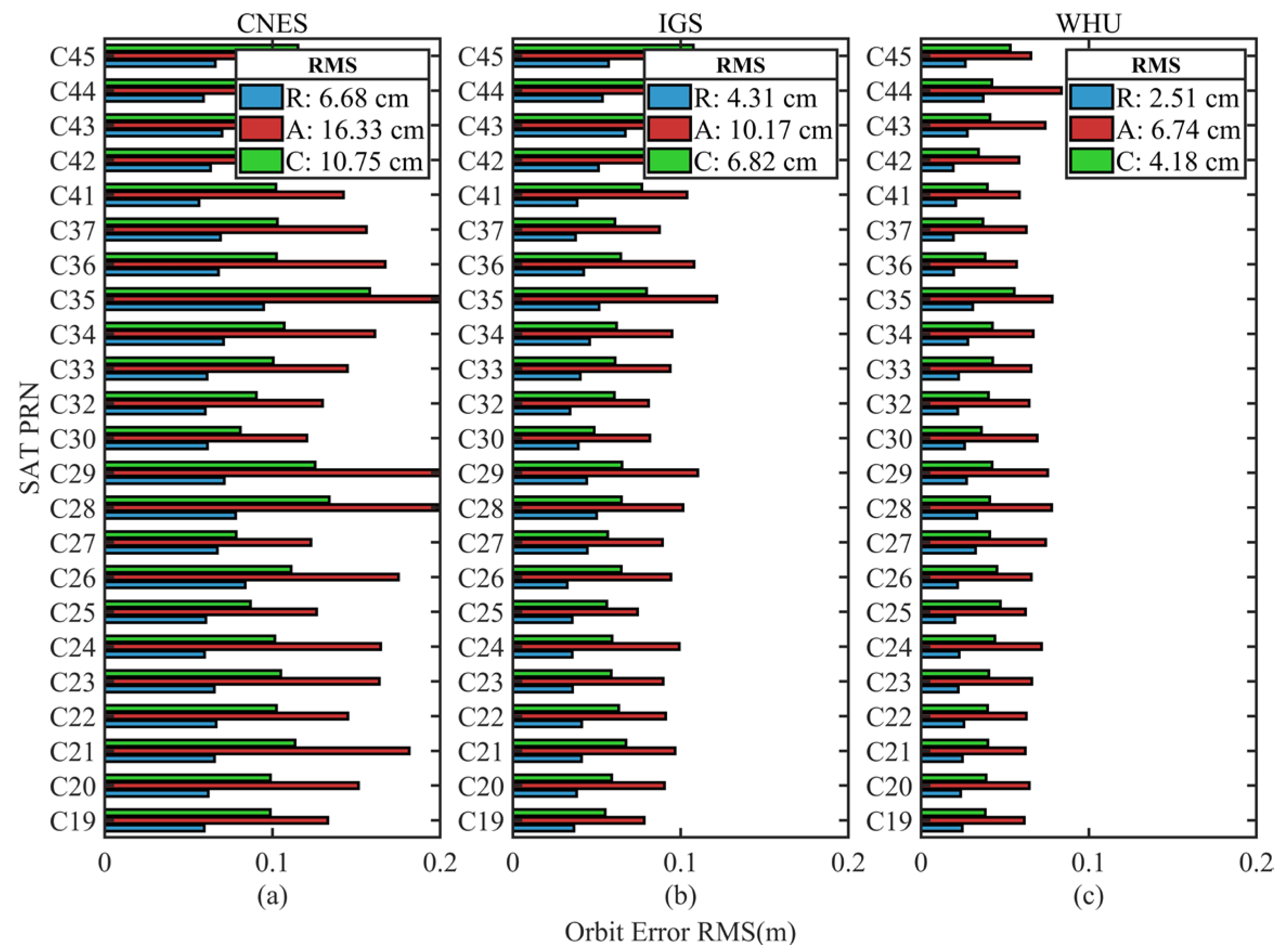

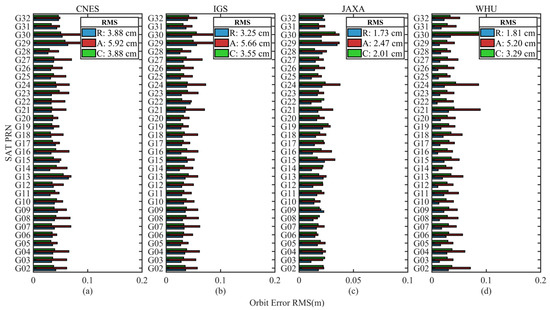

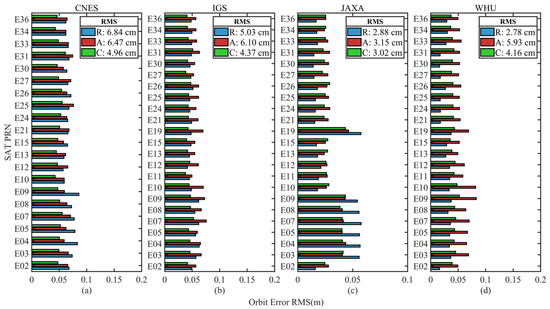

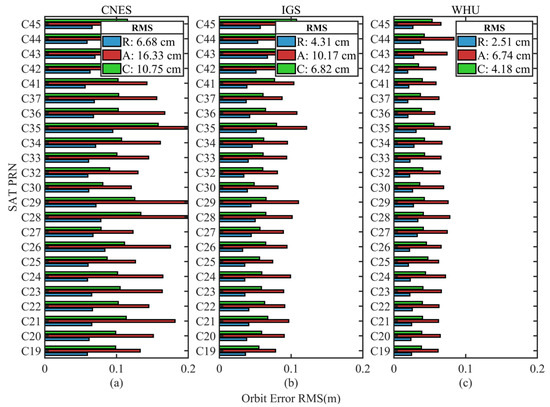

The RMS of GPS, Galileo, and BDS from four analysis centers are shown in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, respectively. While Figure 2a–d and Figure 3a–d present the evaluation results for CNES, IGS, JAXA, and WHU, respectively, Figure 4a–c present the evaluation results of CNES, IGS, and WHU, respectively. The average RMS of the satellites for each system are also shown in each subfigure in the R, A, and C directions. Since BDS GEO satellite products are not included in the CNES and WHU analysis center, the BDS satellite orbit errors are evaluated only for MEO satellites.

Figure 2.

Root Mean Square (RMS) of orbit differences in radial (R), along (A), and cross (C) directions with respect to the final reference products of GPS satellites. (a) RMS of orbit differences from CNES products; (b) RMS of orbit differences from IGS products; (c) RMS of orbit differences from JAXA products; (d) RMS of orbit differences from WHU products.

Figure 3.

RMS of orbit differences in R, A, and C directions with respect to the final reference products of Galileo satellites. (a) RMS of orbit differences from CNES products; (b) RMS of orbit differences from IGS products; (c) RMS of orbit differences from JAXA products; (d) RMS of orbit differences from WHU products.

Figure 4.

RMS of orbit differences in R, A, and C directions with respect to the final reference products of BDS satellite. (a) RMS of orbit differences from CNES products; (b) RMS of orbit differences from IGS products; (c) RMS of orbit differences from WHU products.

It is shown from Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 that the RMS in R, A, C directions are 1.73~3.88 cm, 1.74~5.92 cm, and 1.29~3.88 cm for GPS, 1.89~6.84 cm, 1.80~6.47 cm, and 1.58~4.96 cm for Galileo, and 2.51~6.68 cm, 2.50~16.33 cm, and 2.20~10.75 cm for BDS MEO satellites, respectively. Compared with GPS orbit error, Galileo and BDS orbit accuracy are lower, apparently.

Figure 2 shows that JAXA product has the highest GPS satellite orbit accuracy in R, A, C directions, which are 1.73 cm, 2.47 cm, and 2.01 cm, respectively. While CNES orbit accuracy in R, A, C directions is the worst in the four analysis centers, which are 3.88 cm, 5.92 cm, and 3.88 cm, respectively. Then, WHU product orbit accuracy is higher than IGS product. The orbit accuracy comparison result in Figure 2 can also be shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, where WHU orbit accuracy higher than IGS and IGS orbit accuracy is higher than CNES. Additionally, as shown in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, GPS demonstrates higher orbit accuracy than Galileo and BDS, and Galileo higher than BDS.

Table 1 lists the RMS values of each constellation for R, A, C, and 3D directions. GPS and Galileo orbit errors from JAXA products deliver the best accuracy among all products of the four analysis centers, with R, A, C, and 3D orbital errors of 1.73 cm, 2.47 cm, 2.01 cm, 3.62 cm for GPS satellite, and 2.88 cm, 3.15 cm, 3.02 cm, 5.23 cm for Galileo satellite, respectively. On the other hand, the BDS orbital error is optimal for the WHU product, with R, A, C, and 3D orbital errors of 2.51 cm, 6.74 cm, 4.18 cm, and 8.32 cm, respectively.

Table 1.

R, A, C, and 3D orbital errors of GPS, Galileo, and BDS for each analysis Center product.

3.1.2. Precise Clock Product Evaluation

Due to the different processing strategies and references from different clock products, nanosecond deviations of system bias exist between products from different analysis centers. The all-satellite reference method is applied to evaluate the accuracy of the precise clock product, since system bias in PPP would be absorbed by receiver clock parameter, and other errors have no influence in PPP accuracy, which would be absorbed by ambiguity parameter. Therefore, the average STD of precise clock corrections compared with the reference clock products is used as an index to evaluate the accuracy of precise clock product.

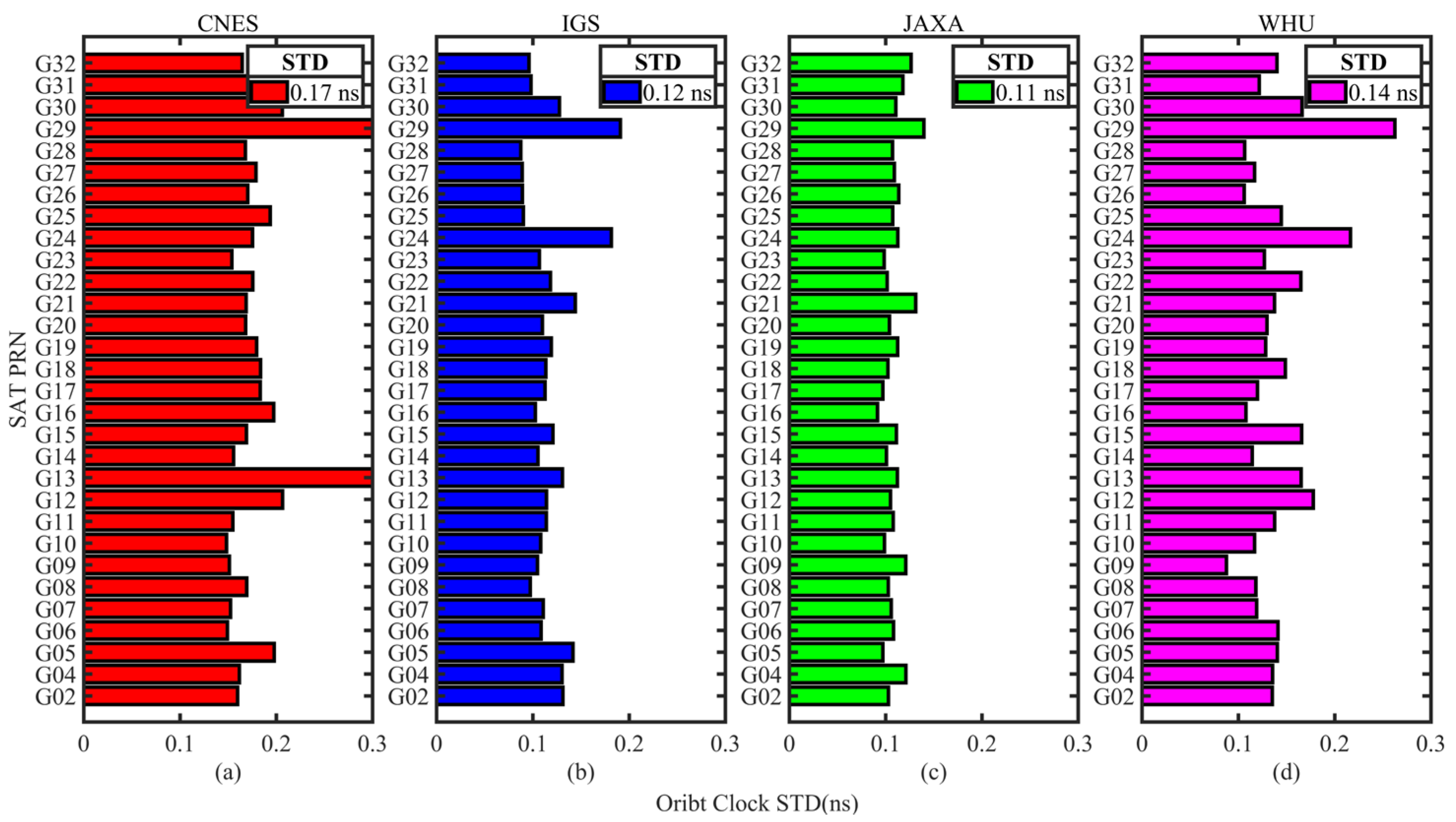

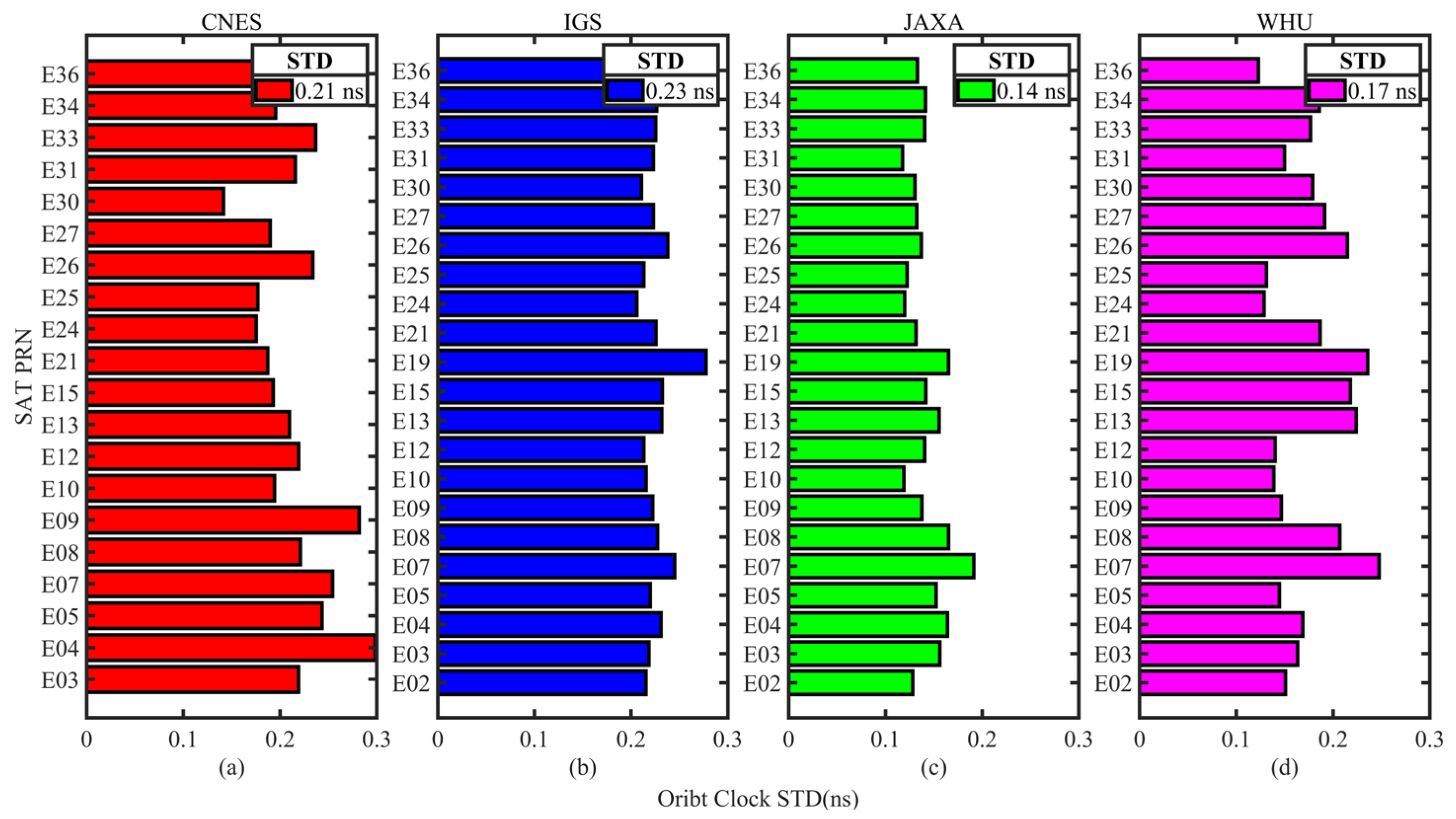

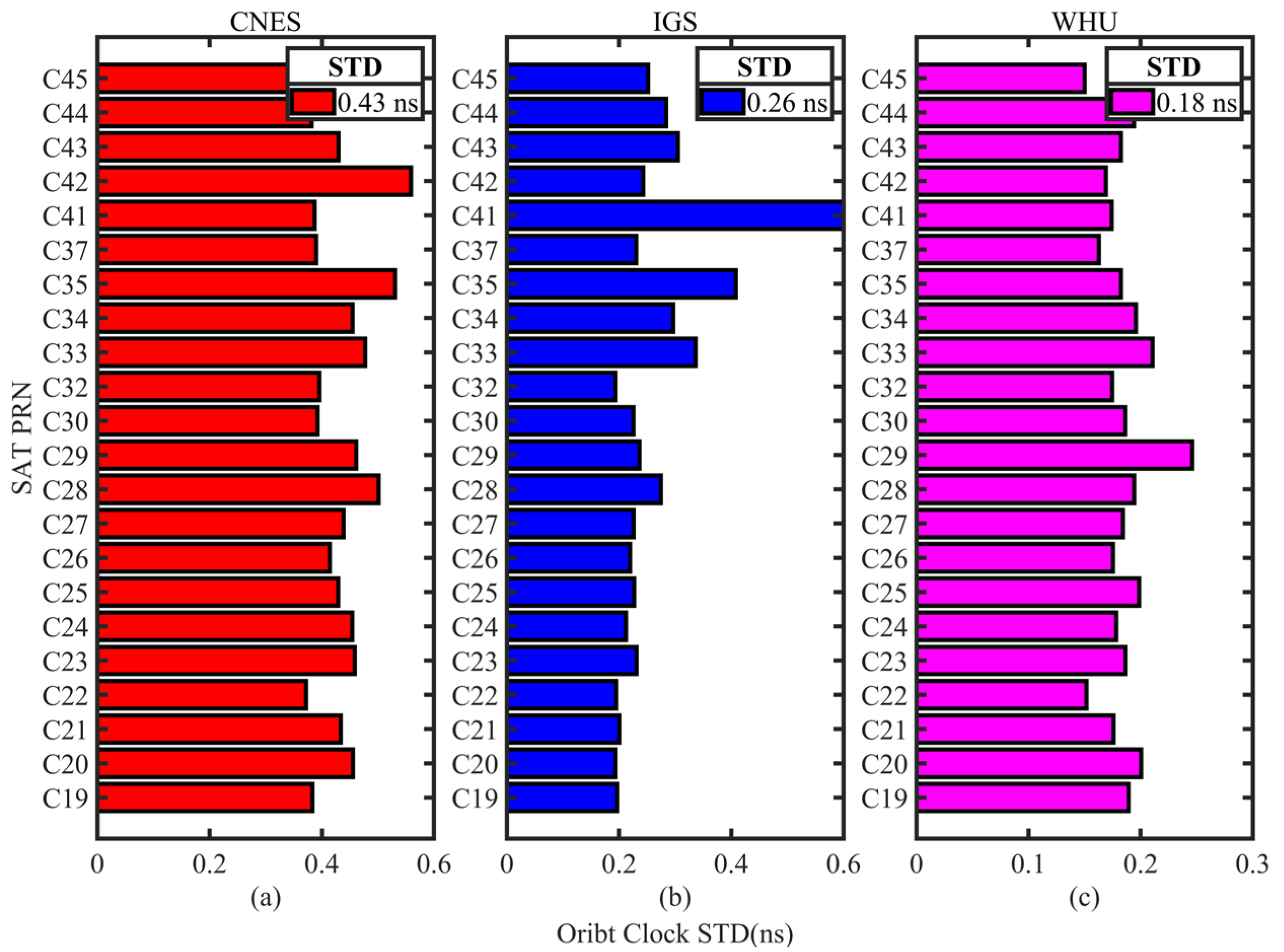

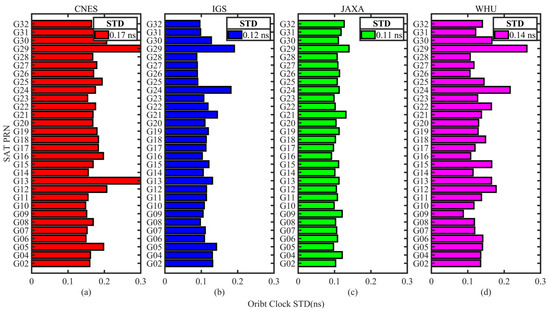

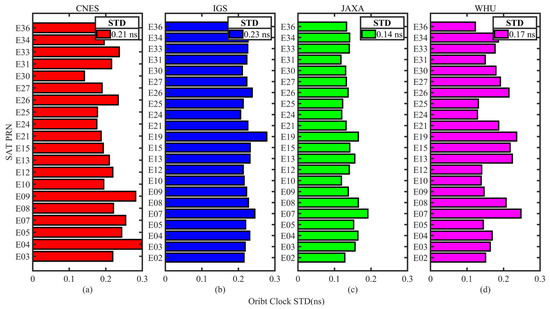

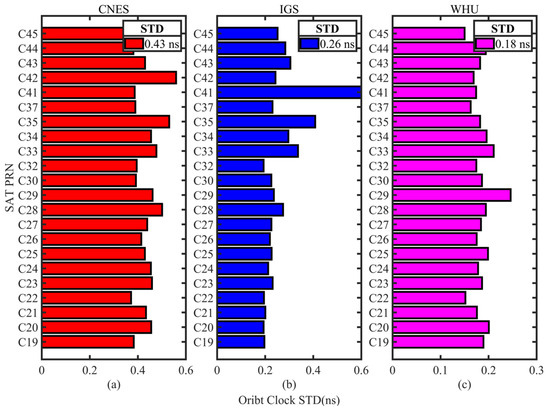

The average STD of GPS, Galileo, and BDS real-time clock corrections for the four analysis centers are displayed in Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7. CNES is shown in red, IGS in blue, JAXA in green, and WHU in magenta, where BDS only counts the MEO satellite clock corrections. Figure 5a–d and Figure 6a–d show the evaluation results of CNES, IGS, JAXA, and WHU, respectively, and Figure 7a–c show the evaluation results of CNES, IGS, and WHU, respectively. The average STDs of the satellites of each system are also given in the figure. According to the results given in Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7, it can be seen that the STD of GPS and Galileo clock corrections of CNES products are 0.17 ns and 0.21 ns, respectively, but the error of BDS satellite clock differentials is larger, with an STD of 0.43 ns. The GPS clock corrections of IGS products are the best, with an STD of 0.12 ns, while the Galileo and BDS are worse, with an STD of 0.23 and 0.26 ns, respectively. The GPS clock corrections accuracy of JAXA is 0.11 ns, the same as that of CNES, and the Galileo clock corrections STD is 0.14 ns. The clock accuracies of GPS, Galileo, and BDS in WHU products are 0.14 ns, 0.17 ns, and 0.18 ns, respectively, and the accuracy of the clock corrections of the three systems is close to each other, with 0.05 ns for GPS and Galileo, and 0.08 ns for BDS. In summary, the results show that GPS has the highest clock correction accuracy among the clock products of the four analysis centers, followed by Galileo, while the accuracy of BDS is lower than that of GPS and Galileo.

Figure 5.

Standard deviation (STD) of each GPS satellite clock corrections with respect to the final reference products. (a) STD of clock differences from CNES products; (b) STD of clock differences from IGS products; (c) STD of clock differences from JAXA products; (d) STD of clock differences from WHU products.

Figure 6.

STD of each Galileo satellite clock corrections with respect to the final reference products. (a) STD of clock differences from CNES products; (b) STD of clock differences from IGS products; (c) STD of clock differences from JAXA products; (d) STD of clock differences from WHU products.

Figure 7.

STD of each BDS satellite clock corrections with respect to the final reference products. (a) STD of clock differences from CNES products; (b) STD of clock differences from IGS products; (c) STD of clock differences from JAXA products.

3.2. Estimation of ZTD and PWV

This section first describes the GNSS datasets used for the experiment and its processing strategy of real-time PPP. Utilizing MGEX station datasets, the ZTD is estimated by PPP technique based on real-time precise products from different analysis centers and the PWV is then retrieved. Finally, the ZTD and PWV are evaluated by comparing with the IGS final tropospheric products, the ECMWF reanalysis products, and the radiosonde data, respectively.

3.2.1. Data Selection and Processing Strategy

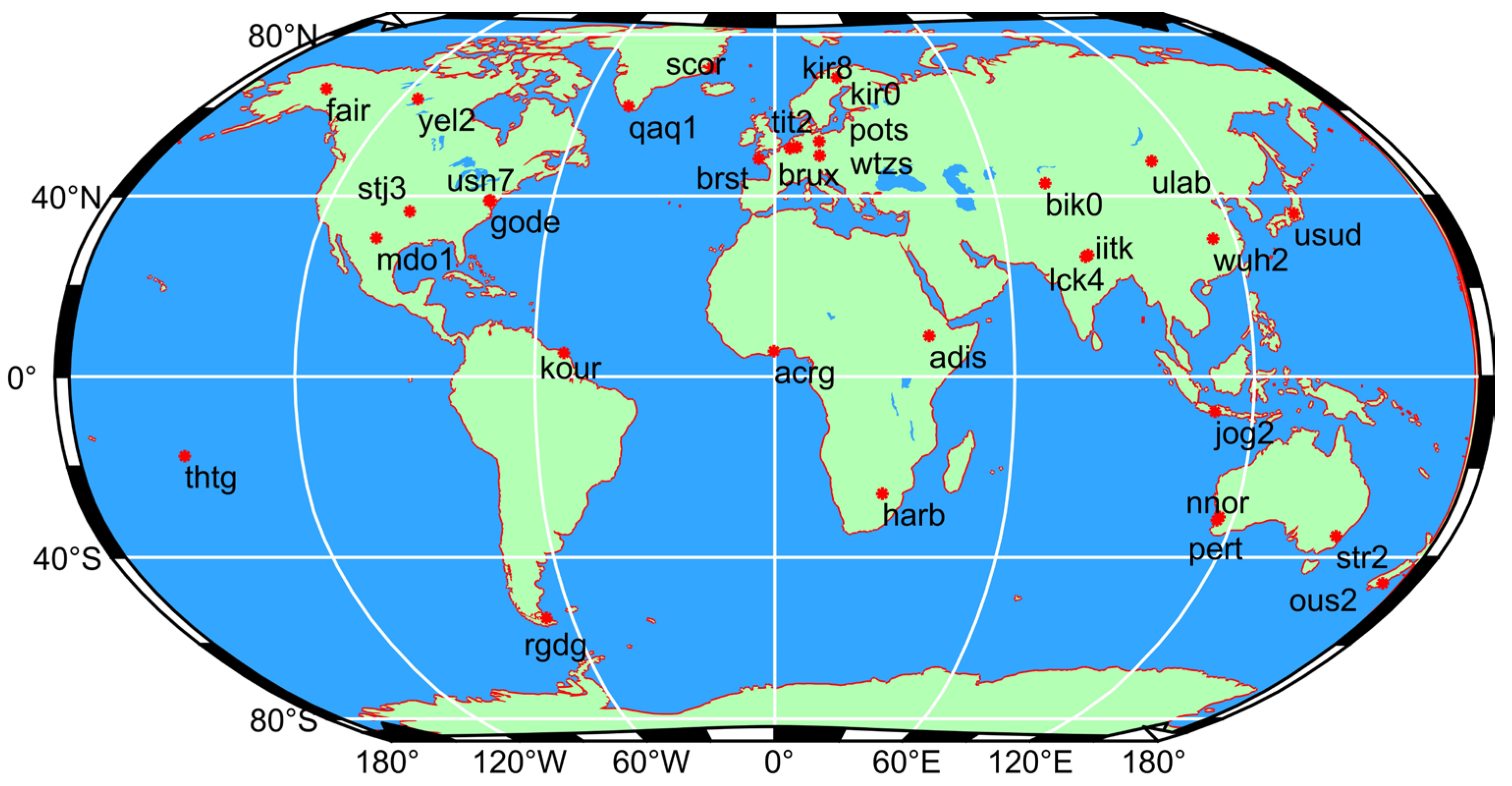

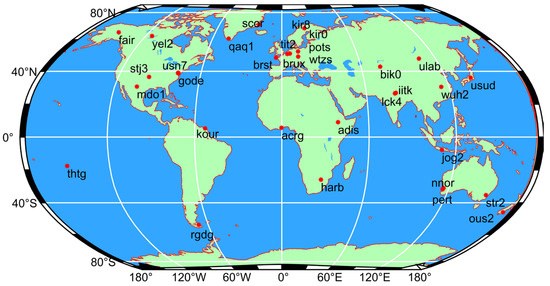

In this research, the 32 stations selected for the experiment are distributed across all major continents worldwide (except Antarctica). Furthermore, when selecting these stations, full consideration was given to the continuity of station data from DOY 214 to 243 in 2024. All selected MGEX stations support tracking GPS, Galileo, and BDS observations. The distribution of the selected stations is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Distribution of selected global stations.

Table 2 shows the data processing strategy. First, four real-time products from analysis center of CNES, IGS, JAXA, and WHU are used in DF-PPP. Four different ZTD solutions, including GPS-only, Galileo-only, BDS3-only, and GPS + Galileo + BDS3 PPP processing, are generated for comparative analysis. GPS, Galileo, and BDS3 signal selections are L1&L2, E1&E5a, and B1C&B2a, respectively. The time resolution of IGS final troposphere products is 5 min with an accuracy of 4 mm, which are therefore selected as the reference value for validating the accuracy of estimable ZTD from real-time PPP [48]. The global grid data with horizontal resolution of from ERA5 single-level data and the radiosonde dataset from the University of Wyoming, including geopotential, temperature, and mean sea level pressure, are collected to verify the validate accuracy of PPP-PWV [49]. Since the temporal resolution of the ERA5 and radiosonde dataset is 1 h and 12 h, respectively, the PPP-PWV are compared with the PWV from ERA5 and radiosonde dataset separately.

Table 2.

Data processing strategy.

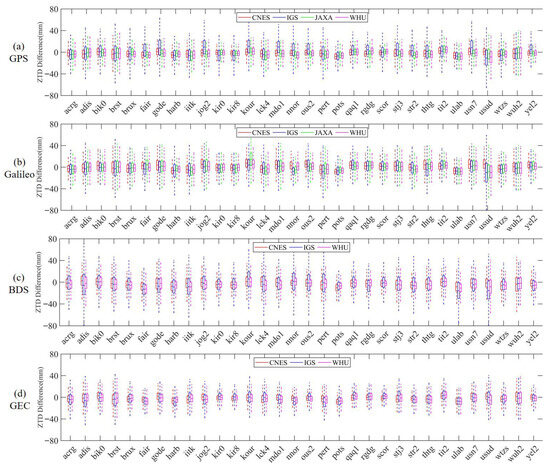

3.2.2. ZTD Validation

The ZTDs derived from four DF-PPP processing are compared with the IGS tropospheric final products. Figure 9 exhibits the ZTD difference of 32 MGEX stations for four solutions by box plot, and Figure 9a–d show the ZTD difference for GPS-only, Galileo-only, BDS3-only, and GPS + Galileo + BDS, respectively. The center line of the box represents the median, and the distance between the upper and lower margins with the 25% quartile and the 75% quartile represent Inter-Quartile Range (IQR), respectively. Based on the statistical results shown in Figure 9, it can be seen that the STD of most stations are lower than 14 mm, while the statistical results of USUD station are worst among the 32 stations. It can be concluded that the statistical results of ZTD difference can reflect the observation quality of the stations.

Figure 9.

ZTD difference at 32 stations in the processing of GPS-only, Galileo-only, BDS-only, and GPS + Galileo + BDS solutions.

Table 3 gives the average mean, STD, and RMS statistics of ZTD estimates at 32 stations in the four solutions. The mean values of four analysis centers demonstrate a good consistency, which differences in four centers in single-system solutions are under 1 mm and multi-system solution difference is under 0.5 mm. Both the STD and RMS statistics show that GPS + Galileo + BDS3 solutions are best, GPS-only ones are secondary, and Galileo-only and BDS3-only are slightly worse. Take RMS, for example; this phenomenon can be seen clearly in the example of CNES statistical data. The RMS statistics from CNES in four solutions are 7.78 mm, 10.17 mm, 11.02 mm, and 7.72 mm, respectively. Compared with GPS-only, Galileo-only, and BDS3-only solutions, multi-system solution RMS reduces 7.8%, 31.7%, and 42.7%, respectively.

Table 3.

Average of zenith tropospheric delay (ZTD) statistics from 32 stations under different solutions with each analysis center products.

As for the other three analysis centers data, ZTD RMS of GPS-only and Galileo-only solutions from JAXA real-time product are 9.06 mm and 11.79 mm, respectively. WHU RMS for GPS-only is 9.55 mm and 10.94 mm for Galileo-only. Compared with other analysis centers, IGS has the worst RMS accuracies with 12.90 mm, 14.04 mm, 16.05 mm, and 10.16 mm of four solutions, respectively. Based on the above relevant statistics, it can be seen that the processing results of IGS products are worse under the comparison in the same solution. And, the IGS products are weighted according to the products of various other analysis centers, which may also lead to a decrease in the accuracy of data processing.

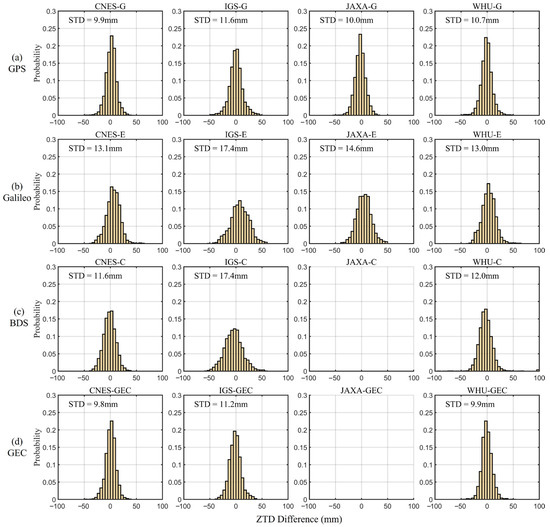

Figure 10 gives the histogram of the ZTD differences between different analysis centers for USN7 station under the four solutions of GPS-only, Galileo-only, BDS3-only, and GPS + Galileo + BDS3. It is shown in each subplot that the histogram of the ZTD difference follows the normal distribution. Additionally, the GPS-only STDs of four analysis centers are relatively close to each other, which STD from CNES products best with 9.9 mm and STD from IGS products worst with 11.6 mm. From Figure 10b–d, STD from CNES products with the best accuracy and STD from IGS products with the worst accuracy are also shown.

Figure 10.

The distribution of the ZTD differences between precise point positioning (PPP) solutions and IGS ZTD products at USN7 station.

Subfigures from left to right column are the histogram evaluation of ZTD solutions with CNES, IGS, JAXA, and WHU products, respectively. Due to the JAXA product not providing BDS signals, JAXA results in Figure 10c,d are absent. According to the statistical results of USN7 station, it can be seen that accuracy of GPS + Galileo + BDS3 is better than that of single-system. Among single-system accuracy, GPS-only solution is the best, followed by BDS3-only solution, and Galileo-only has the worst accuracy.

Taking the first column (CNES products) as an example, STD of four solutions with 9.9 mm, 13.1 mm, 11.6 mm, and 9.8 mm, respectively. Both the IGS and WHU columns show that the STD accuracy increases from single-system solution to multi-system solution. Compared with BDS3-only, multi-system solution for CNES, IGS, and WHU increases 18.3%, 35.6%, and 17.5%, respectively, which shows multi-system can enhance the ZTD accuracy effectively compared with single-system solution.

3.2.3. PWVs Validation by Radiosonde and ERA5 Data

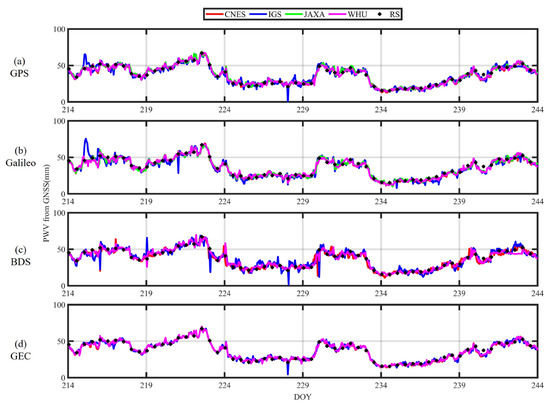

After validating ZTD accuracy from PPP technique, PWV are calculated from the method in Section 2, then the PWV results are validated against the ECMWF reanalysis dataset and radiosonde dataset. Taking the USN7 station as an example, Figure 11 shows the time series of PWV retrieval from GNSS data and radiosonde data during DOY214–243 in 2024, while Figure 11a–d represent PPP PWV from the GPS-only, Galileo-only, BDS3-only, and GPS + Galileo + BDS3 solutions, respectively.

Figure 11.

Time series plot of precipitable water vapor (PWV) retrieval from global navigation satellite system (GNSS) vs. radiosonde data.

As seen from Figure 11, the four solutions have a good agreement with the peaks and troughs in the DOY214~243 time series curves of the radiosonde data. Compared with Galileo-only and BDS-only solutions results, the GPS-only data have better fitting and shorter convergence time, while the IGS products have longer convergence time under the Galileo-only and BDS3-only solutions, and this situation is improved under the multi-system solution.

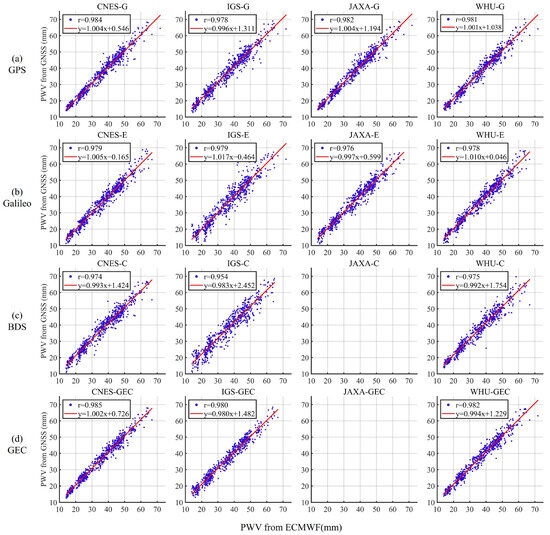

Figure 11 shows a good agreement between PPP-PWV and PWV derived from radiosonde data. However, due to the fact that radiosonde data is solely available twice each day (00:00 and 12:00), there are only 60 RS datasets during 30 days. Thus, a correlation analysis between GNSS PWV and radiosonde PWV time series is solely of limited significance. Figure 12 shows the correlation between PPP-PWV and ECMWF data of the four solutions by the linear fitting. Horizontal and vertical axes are PWV from ECMWF and PPP-PWV, respectively. JAXA results in Figure 12a,d are also absent. Each column shows that multi-system solution correlation coefficient higher than single-system correlation coefficients, and GPS-only solution has the highest correlation in the single-system solution.

Figure 12.

Linear correlation of PPP-PWV to ECMEF-derived PWV at station USN7.

From Figure 12a–d it can be seen that the CNES product has the highest correlation coefficients, with the correlation results of multi-system solution arriving at 0.985. In the other three analysis centers, WHU has the highest correlation coefficient of GPS-only and Galileo-only, which has almost the same correlation coefficients compared with the CNES rapid product. The correlation coefficients of the JAXA product in GPS-only and Galileo-only are slightly different from the CNES results, with a correlation coefficient of 0.982 for the former and 0.976 for the latter. The correlation coefficients for IGS products are only 0.954 of Galileo-only and BDS3-only solutions, but multi-system correlation coefficient has 0.980, which shows multi-system solution potential in PWV retrieval. WHU real-time product has the best results in BDS3-only solution with a correlation coefficient of 0.975, which is an advantage over the real-time products of CNES and IGS. In summary, these analysis centers have good agreement with ECMWF data both in single-system and multi-system solutions.

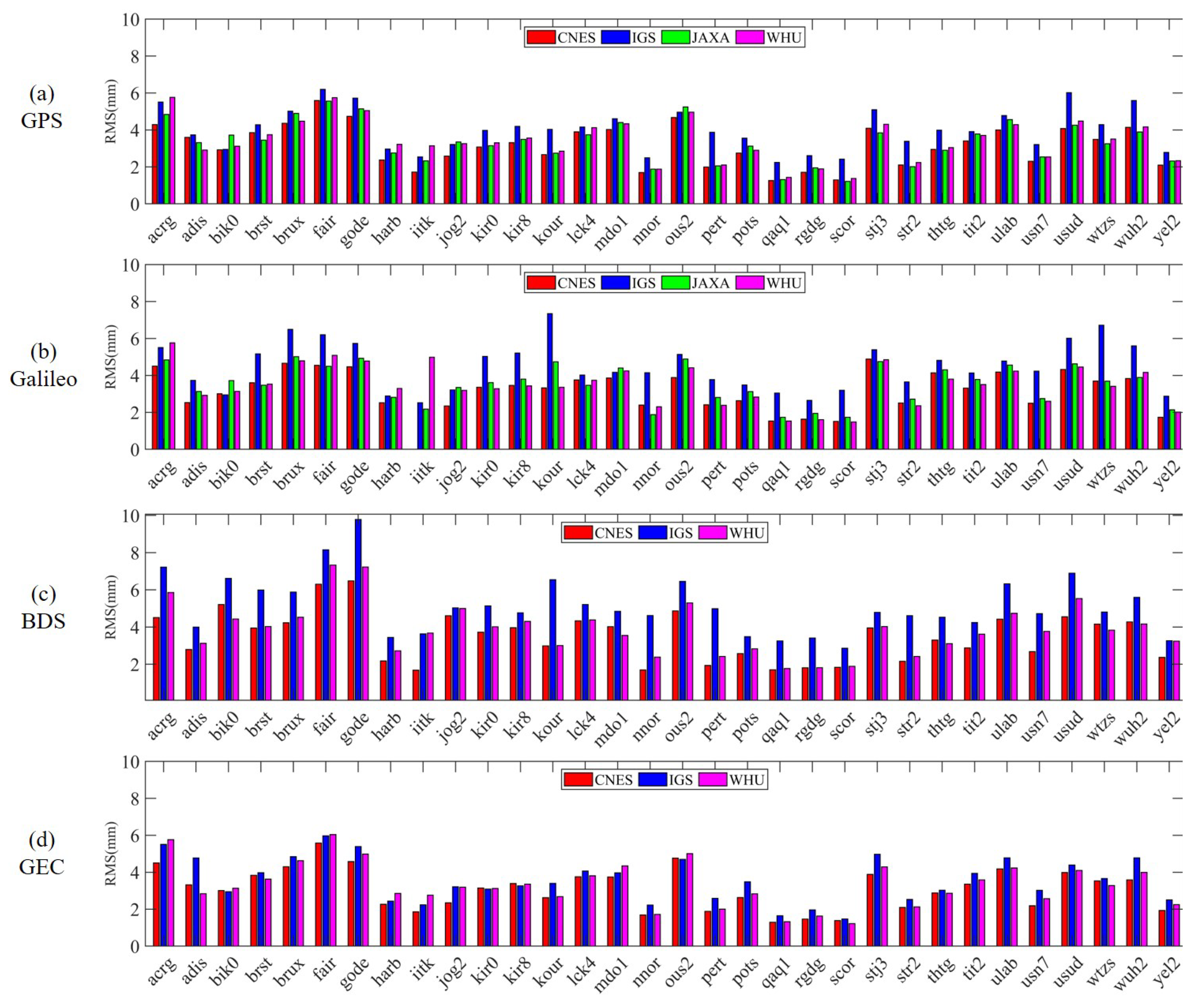

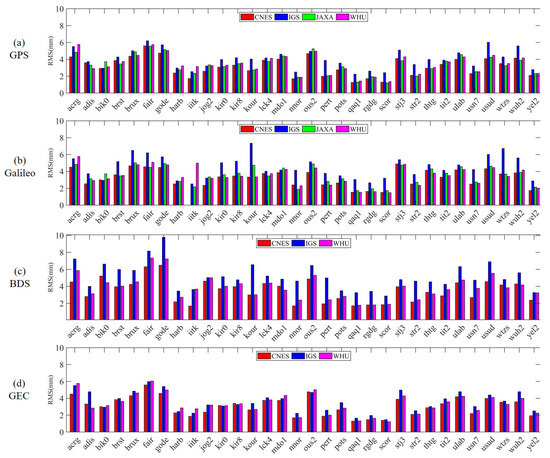

After the correlation between ECMWF-PWV and PPP-PWV has been verified, PPP-PWV accuracy should obtain further quantitative evaluation. The results of the statistical PPP-PWV and EAR5 reanalysis data differences for each processing solution are shown in Figure 13a–d. In Figure 13a, it is shown that in the GPS-only solutions, PWV difference from the ERA5 data at 32 stations are almost all less than 5 mm. In Figure 13b, most station results are similar to GPS-only, besides some station PWV difference from IGS product that exceed 6 mm. In Figure 13c, RMS of PWV difference between most stations are under 6 mm. In Figure 13d, PWV difference in multi-GNSS solutions show better accuracy than single-system, apparently, with difference in the most stations below 4 mm. Therefore, multi-system observation can help to improve PWV retrieval from real-time products.

Figure 13.

The RMS of PWV differences between PPP solutions and ECMWF solution at 32 MGEX stations.

To evaluate the overall performance of PPP-PWV retrieval, Table 4 summarizes the average PWV statistics of the 32 stations. As shown in Table 4, the RMS of the differences between the PWV and ERA5 data obtained from the retrieval of each analysis center is below 5 mm. Take RMS of PWV from CNES products as an example, multi-system solutions are with the best accuracy, and GPS-only accuracy is higher than Galileo-only and BDS3-only. The RMS of PWV from CNES products for four solutions are 3.15 mm, 3.25 mm, 3.50 mm, and 3.09 mm, which are higher than IGS, JAXA, and WHU solutions. RMS of PWV from IGS products for four solutions are unsatisfactory, where PWV accuracy of single-system and multi-system solutions are more than 3.78 mm, 4.10 mm, 4.59 mm, and 3.34 mm, respectively. The PWV retrieval from WHU real-time product outperforms IGS product in all four solutions, yielding RMS values of 3.42 mm, 3.48 mm, 3.87 mm, and 3.31 mm, respectively, which generally meet the accuracy requirement. Notably, PWV retrieval from CNES products has the best accuracy than the other analysis centers.

Table 4.

Average PWV statistics of 32 stations under different solutions in each analysis center.

Based on the distribution of observation stations and the PWV results in Figure 13, it can be observed that stations such as GODE and USUD are located in subtropical monsoon climate regions or near coastal areas. Given the abundant water vapor and high variability in these regions, significant fluctuations in PWV are more likely to occur.

4. Discussions

The aim of this study was to evaluate the performance of real-time ZTD estimation and PWV retrieval using multi-GNSS PPP based on real-time products from four analysis centers (CNES, IGS, JAXA, WHU). The experimental results consistently show that multi-system integration (GPS + Galileo + BDS3) markedly enhances both the accuracy and stability of ZTD and PWV retrieval compared with single-system solutions. The following discussion summarizes the implications of the findings, highlights the technical contributions, and outlines the limitations and future research directions.

This study provides a comprehensive evaluation of four real-time products, detailing their respective advantages and shortcomings in orbit accuracy, clock stability, and product completeness. While previous research has focused primarily on GPS and Galileo, our results explicitly demonstrate the capability of BDS3 for real-time PWV retrieval, reinforcing its value for future multi-GNSS-based meteorological applications. Moreover, the findings confirm that a combined GPS + Galileo + BDS3 strategy not only improves ZTD and PWV accuracy but also enhances system reliability under single-system outages or data interruptions.

Despite its broad coverage, the IGS real-time product exhibits lower data completeness (94.75%) compared with the other centers, which may limit its operational applicability. Full constellation utilization is also limited because BDS3 products are unavailable from JAXA, and GEO satellites are not included in the CNES and WHU products. Furthermore, although this study uses a global set of MGEX stations, it does not explicitly examine performance variations across climatic regions or seasons. PWV retrieval accuracy may fluctuate under extreme weather or in areas with strong atmospheric instability.

The findings of this study demonstrate that the multi-system GNSS PWV retrieval, based on real-time products from multiple analysis centers, holds potential for operational applications in near real-time weather monitoring and forecasting. High-precision real-time PWV products can be directly utilized in data assimilation systems to enhance the characterization of the initial moisture fields in numerical weather prediction models, proving particularly valuable for nowcasting of extreme weather events such as heavy rainfall and typhoons. Future work will focus on evaluating the performance of this method across different climatic regions and seasons.

5. Conclusions

Experiment of product evaluation shows real-time products have good data quality. Except for IGS analysis center, the data completeness rates in the real-time products provided by the selected analysis centers can achieve 99%. The GPS and Galileo orbital errors of JAXA were the smallest, with 3D RMS of 3.6 cm and 5.2 cm, respectively. The highest BDS orbital accuracy was achieved by WHU with 3D RMS of 8.3 cm, whereas the highest GPS and Galileo clock correction accuracy was achieved by CNES, both of which were 0.11 ns, and the highest BDS clock correction accuracy was achieved by WHU, with STD of 0.18 ns.

The ZTD comparison results show that the BDS3-only solution provides the most significant deviation in PPP, with CNES, IGS and WHU RMSs of 11.02 mm, 16.05 mm, and 12.71 mm, respectively. Although the BDS3-only method is less effective than GPS-only and Galileo-only, the processing of the system combination enhances the accuracy of ZTD derivation with RMSs of 7.72 mm, 10.16 mm, and 8.89 mm, respectively, which meet the requirements of the PWV retrieval experiment. In addition, since the IGS product is weighted by multiple analysis centers, this may have led to a degradation in accuracy.

The comparison of PWV reveals that the BDS3-only solution performs comparably to the GPS solution. PWV results obtained from all processing strategies show good agreement with the ECMWF PWV data, which is further supported by the high correlation coefficients presented in the table. Furthermore, integrating multi-GNSS data enhances the stability and accuracy of the PWV estimates. Specifically, compared to single-system PPP-PWV, the RMS of multi-system PPP-PWV from different analysis centers shows an improvement ranging from 0.06 mm to 1.25 mm. It is also noted that the IGS final product, being a weighted combination of products from other analysis centers, might lead to its PWV accuracy being slightly lower than that of some individual center products.

These experiments demonstrated that the real-time products from different analysis centers that retrieve PWV have good consistency. Compared with GPS and Galileo, BDS3 has exhibited sufficient accuracy, which has great potential for retrieving atmospheric parameters and reveals applications in severe weather monitoring and forecasting. As the BDS3 real-time product is released and refined, further work needs to be performed to identify the performance of the BDS3 real-time retrieval atmosphere and make the BDS3 available for more situations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.L. and L.H.; software, H.G.; validation, W.L., H.G. and B.D.; writing—original draft preparation, W.L. and H.G.; writing—review and editing, F.Y., H.L. and L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42474020), the science and technology innovation Program of Hunan Province, China (Grant No. 2023RC3217), the Key R&D Program of Hunan Province (Grant No. 2025JK2059), Hunan Engineering Research Center of BeiDou High-Precision Satellite Navigation and Location Based Service (Grant No. KFKT2025-N002).

Data Availability Statement

The ERA5 data is provided by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets (accessed on 12 December 2025). The radiosonde data is provided by the University of Wyoming https://weather.uwyo.edu/upperair/sounding.shtml (accessed on 12 December 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts and the University of Wyoming for providing the ERA5 data and the radiosonde data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bevis, M.; Businger, S.; Chiswell, S.; Herring, T.A.; Anthes, R.A.; Rocken, C.; Ware, R.H. GPS meteorology: Mapping zenith wet delays onto precipitable water. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 1994, 33, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevis, M.; Businger, S.; Herring, T.A.; Rocken, C.; Anthes, R.A.; Ware, R.H. GPS meteorology: Remote sensing of atmospheric water vapor using the global positioning system. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1992, 97, 15787–15801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Huang, K.; Fang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, R.; Yi, F. Seasonal and Diurnal Changes of Air Temperature and Water Vapor Observed with a Microwave Radiometer in Wuhan, China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Chen, B.; Wang, W.; Yu, W.; Dai, W. Evaluating precipitable water vapor products from Fengyun-4A meteorological satellite using radiosonde, GNSS, and ERA5 Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4106512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, T.; Su, K.; Zhang, J.; Hu, H.; Wang, H. Precipitable Water Vapor Retrieval Based on GNSS Data and Its Application in Extreme Rainfall. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. The Zenith Total Delay Combination of International GNSS Service Repro3 and the Analysis of Its Precision. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3885. [Google Scholar]

- Bhm, J.; Mller, G.; Schindelegger, M.; Pain, G.; Weber, R. Development of an improved empirical model for slant delays in the troposphere (GPT2w). GPS Solut. 2015, 19, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallon, E.; Joerger, M.; Pervan, B. Robust modeling of GNSS tropospheric delay dynamics. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2021, 57, 2992–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhu, G.; Peng, H.; Liu, L.; Ren, C.; Jiang, W. An improved global grid model for calibrating zenith tropospheric delay for GNSS applications. GPS Solut. 2023, 27, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüller, T. The TropGrid2 standard tropospheric correction model. GPS Solut. 2014, 18, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonoglou, N.; Balidakis, K.; Wickert, J.; Dick, G.; de la Torre, A.; Bookhagen, B. Water-Vapour Monitoring from Ground-Based GNSS Observations in Northwestern Argentina. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, T.-Y.; Yeh, T.-K.; Wang, C.-S.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, N.; Yang, S.-C. Accuracy verification of the precipitable water vapor derived from COSMIC-2 radio occultation using ground-based GNSS. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 73, 4597–4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marut, G.; Hadas, T.; Kaplon, J.; Trzcina, E.; Rohm, W. Monitoring the water vapor content at high spatio-temporal resolution using a network of low-cost multi-GNSS receivers. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5804614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, S.; Xu, Y.; Yu, H. Trends in precipitable water vapor in North America based on GNSS observation and ERA5 reanalysis. Clim. Dyn. 2025, 63, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgered, G.; Johansson, J.M.; Rönnäng, B.O.; Davis, J.L. Measuring regional atmospheric water vapor using the Swedish Permanent GPS Network. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 24, 2663–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chan, P.W.; Hon, K.K. Assimilating GNSS PWV and radiosonde meteorological profiles to improve the PWV and rainfall forecasting performance from the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model over the South China. Atmos. Res. 2023, 286, 106677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Peng, H.; Liu, L.; Xiong, S.; Xie, S.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; He, H. GNSS precipitable water vapor retrieval with the aid of NWM data for China. Earth Space Sci. 2021, 8, e2020EA001550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, S.; Zhang, K.; Fu, E.; Xu, Y.; Qiu, C.; Zhang, J.; Li, L. A new method for determining an optimal diurnal threshold of GNSS precipitable water vapor for precipitation forecasting. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Fan, L.; Zhang, W.; Shi, C. Long-term correlation analysis between monthly precipitable water vapor and precipitation using GPS data over China. Adv. Space Res. 2022, 70, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H. Quality Control in Monitoring Precipitable Water Vapor with GNSS Precise Point Positioning. Master’s Thesis, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Lu, C.; Han, X.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, B.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. Real-time shipborne multi-GNSS atmospheric water vapor retrieval over the South China Sea. GPS Solut. 2023, 27, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhang, F.; Chen, X.; Yang, Z. Accuracy analysis of real-time precise point positioning—Estimated precipitable water vapor under different meteorological conditions: A case study in Hong Kong. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhao, P.; Wang, J. Precipitable water vapor retrieval for rainfall forecasting using BDS-3 PPP-B2b signal in the coastal region of China. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 116309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsobeiey, M.; Al-Harbi, S. Performance of real-time Precise Point Positioning using IGS real-time service. GPS Solut. 2016, 20, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhang, K.; Rohm, W.; Choy, S.; Norman, R.; Wang, C.S. Real-time retrieval of precipitable water vapor from GPS precise point positioning. J. Geophys. Res. D Atmos. JGR 2014, 119, 10043–10057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Xu, C.; Guo, J.; Gao, Y. Real-Time GPS Precise Point Positioning-Based Precipitable Water Vapor Estimation for Rainfall Monitoring and Forecasting. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2015, 1, 3452–3459. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.; Li, X.; Nilsson, T.; Ning, T.; Heinkelmann, R.; Ge, M.; Glaser, S.; Schuh, H. Real-time retrieval of precipitable water vapor from GPS and BeiDou observations. J. Geod. 2015, 89, 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Cao, X.; Ge, Y.; Li, W. Assessment of the positioning performance and tropospheric delay retrieval with precise point positioning using products from different analysis centers. GPS Solut. 2020, 24, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Ren, X. Featured services and performance of BDS-3. Sci. Bull. 2021, 66, 2135–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Xiao, G.; Du, L. Initial performance assessment of Galileo High Accuracy Service with software-defined receiver. GPS Solut. 2024, 28, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Xiufeng, H.; Vagner, F.; Shengyue, J.; Ying, X.; Susu, S. Assessment of precipitable water vapor retrieved from precise point positioning with PPP-B2b service. Earth Sci. Inform. 2023, 16, 315–328. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.; Feng, G.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, K.; Tan, H.; Dick, G.; Wickert, J. Real-Time Retrieval of Precipitable Water Vapor From Galileo Observations by Using the MGEX Network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 4743–4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Deng, M.; Chen, B. Real-time GNSS meteorology: A promising alternative using real-time PPP technique based on broadcast ephemerides and the open service of Galileo. GPS Solut. 2024, 28, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhao, P.; Wang, J.; Meng, X. Performance assess of BDS-3 PPP-B2b signal service and its application in precipitable water vapor retrieval. In Proceedings of the China Satellite Navigation Conference, Beijing, China, 26–28 April 2023; pp. 118–131. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, W.; Teferle, F.N.; Kazmierski, K.; Laurichesse, D.; Yuan, Y. An evaluation of real-time troposphere estimation based on GNSS Precise Point Positioning. J. Geophys. Res. D Atmos. JGR 2017, 122, 2779–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q. Assessment of BDS-3 PPP-B2b Service and Its Applications for the Determination of Precipitable Water Vapour. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1048. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, P.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Lyu, D.; Xiao, G.; Xiao, K.; Du, L. Real-time precise zenith tropospheric delay estimation with BDS PPP-b2b, Galileo HAS, and QZSS MADOCA-PPP services. Geosci. Remote Sens. IEEE Trans. 2024, 62, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Huang, H.; Ma, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yao, Y.; Lin, X.; Zhao, Q.; Huang, Y. Multi-Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) real-time tropospheric delay retrieval based on state-space representation (SSR) products from different analysis centers. Annales Geophys. (ANGEO) 2024, 42, 09927689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; He, Y.; Yi, W.; Song, W.; Cao, C.; Chen, M. Method for evaluating real-time GNSS satellite clock offset products. GPS Solut. 2017, 21, 1417–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Dong, D.; Li, W.; Jiang, X.; Schuh, H. GAMP: An open-source software of multi-GNSS precise point positioning using undifferenced and uncombined observations. GPS Solut. 2018, 22, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wang, N.; Tan, B.; Chen, Y. Multi-GNSS precise point positioning (MGPPP) using raw observations. J. Geod. 2016, 91, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astudillo, J.M.; Lau, L.; Tang, Y.T.; Moore, T. Analysing the Zenith Tropospheric Delay Estimates in On-line Precise Point Positioning (PPP) Services and PPP Software Packages. Sensors 2018, 18, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saastamoinen, J. Contributions to the theory of atmospheric refraction. Bull. Géod. (1946–1975) 1972, 105, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Dai, A. Global estimates of water-vapor-weighted mean temperature of the atmosphere for GPS applications. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2005, 16, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, S.; Bengtsson, L.; Gendt, G. On the determination of atmospheric water vapor from GPS measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2003, 16, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dousa, J.; Elias, M. An improved model for calculating tropospheric wet delay. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 4389–4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, T.A.; Amir, S.; Othman, R.; Ses, S.; Omar, K.; Abdullah, K.; Lim, S.; Rizos, C. GPS meteorology in a low-latitude region: Remote sensing of atmospheric water vapor over the Malaysian Peninsula. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2011, 73, 2410–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, S.H.; Bar-Sever, Y.E. A new type of troposphere zenith path delay product of the international GNSS service. J. Geod. 2009, 83, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zheng, D.; He, C.; Ye, F.; Yuan, P.; Yao, Y.; Liao, M.; Xie, J. Ionospheric Response to the 24–27 February 2023 Solar Flare and Geomagnetic Storms Over the European Region Using a Machine Learning–Based Tomographic Technique. Space Weather 2025, 23, e2024SW004146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).