Highlights

What are the main findings?

- We propose a novel framework combining multi-path 3D convolution, hierarchical cooperative attention, and cross-attention fusion for adaptive multi-scale spectral–spatial learning. The model achieves an Overall Accuracy (OA) of 0.9929 and reaches zero misclassification for certain classes.

- We design a hybrid CNN–Transformer architecture that overcomes fixed receptive fields and weak global perception. It shows strong adaptability under small-sample conditions, capturing long-range dependencies while preserving spatial detail.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The proposed framework provides a new paradigm for hyperspectral classification that balances local detail and global context. It can directly replace traditional 3D-CNNs as a strong baseline, supporting fine-grained land-cover monitoring and complex object recognition applications.

- The validated “CNN–Transformer + multi-scale attention” architecture demonstrates strong cross-dataset generalization capability. It can be extended to multi-source remote sensing tasks, offering an interpretable and transferable technical pathway for lightweight deployment and real-time processing.

Abstract

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been extensively applied for the extraction of deep features in hyperspectral imagery tasks. However, traditional 3D-CNNs are limited by their fixed-size receptive fields and inherent locality. This restricts their ability to capture multi-scale objects and model long-range dependencies, ultimately hindering the representation of large-area land-cover structures. To overcome these drawbacks, we present a new framework designed to integrate multi-scale feature fusion and a hierarchical attention mechanism for hyperspectral image classification. Channel-wise Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) and Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) spatial attention are combined to enhance feature representation from both spectral bands and spatial locations, allowing the network to emphasize critical wavelengths and salient spatial structures. Finally, by integrating the self-attention inherent in the Transformer architecture with a Cross-Attention Fusion (CAF) mechanism, a local-global feature fusion module is developed. This module effectively captures extended-span interdependencies present in hyperspectral remote sensing images, and this process facilitates the effective integration of both localized and holistic attributes. On the Salinas Valley dataset, the proposed method delivers an Overall Accuracy (OA) of 0.9929 and an Average Accuracy (AA) of 0.9949, attaining perfect recognition accuracy for certain classes. The proposed model demonstrates commendable class balance and classification stability. Across multiple publicly available hyperspectral remote sensing image datasets, it systematically produces classification outcomes that significantly outperform those of established benchmark methods, exhibiting distinct advantages in feature representation, structural modeling, and the discrimination of complex ground objects.

1. Introduction

Hyperspectral remote sensing image classification is regarded as a central issue in hyperspectral data analysis, with extensive applications in fields such as vegetation cover statistics [1], resource exploration [2], military target detection and operations [3], agricultural development [4], urban planning monitoring, and meteorological and environmental monitoring [5]. While hyperspectral remote sensing images offer abundant information, they also present some challenges, such as high dimensionality, strong redundancy, scarce samples, wide intra-class scatter coupled with narrow inter-class margins [6]. These challenges make it difficult for traditional classification methods to perform high-precision identification tasks in complex scenes. Traditional classification methods mainly rely on manually designed shallow features and machine learning algorithms. Although they have a certain interpretability in specific tasks, they still have significant shortcomings in deep feature extraction, generalization ability, and modeling complex land structures [7].

Currently, representative methods for hyperspectral image classification include 1D-CNN-based spectral feature extraction [8], 2D-CNN-driven spatial feature extraction [9], and 3D-CNN-enabled spectral-spatial feature extraction [10]. However, most of these methods employ fixed-size convolutional kernels, making it difficult to adapt to the features of geospatial objects of different scales. Meanwhile, the local perceptual scope of these models limits their ability to perform global modeling of distant objects of the same class during classification [11]. Mou et al. [12] input spectral band sequences as time-series data into recurrent neural networks and optimized activation functions, improving land cover classification accuracy but with limited capability in modeling long-sequence spectral data. Li et al. [13] proposed a grouped multi-kernel convolution strategy to enhance intra-group discriminative information and preserve spectral integrity, yet failing to effectively distinguish different land cover components at the spatial scale. Three-dimensional convolutional networks have gained traction in their ability to simultaneously extract multi-scale fusion of spectral and spatial dimensions in hyperspectral analysis [14]. Roy et al. [15] proposed HybridSN, a hybrid spectral CNN integrating 3D-CNN’s spectral-spatial joint modeling and 2D-CNN’s deep feature extraction. It effectively addressed similar texture classification but tends to over-model redundant spectral bands. Li et al. [16] introduced an end-to-end 3D-CNN method for joint spectral-spatial feature extraction and pixel-level classification, but the model was prone to misclassifying edges and small targets and lacked adaptive spectral band selection, resulting in coarse handling of the spectral dimension. He et al. [17] proposed the ResNet, which effectively addressed the training difficulties of deep networks through shortcut connections. Zhong et al. [18] developed SSRN (Spectral-Spatial Residual Network), which jointly optimized spectral-spatial features to enhance feature transfer and reuse, improving classification efficiency but suffering from accuracy degradation due to redundant pixels and invalid bands.

In order to solve the redundant pixel issue, researchers introduced attention mechanisms for hyperspectral image classification [19]. Zhu et al. [20] combined 2D residual CNNs with the spectral-spatial attention mechanism (SSAM) to obtain more discriminative spectral-spatial features, but they did not adopt 3D convolution—SSAM relied on local weighting and lacked global context modeling capability. Ma et al. [21] proposed CPDB-Net, a center-pixel-based dual-branch network, which integrated a novel frequency-aware attention mechanism into the ViT-based spatial branch. This mitigated non-target interference from expanded spatial windows, yet high-dimensional spectral data increased computational complexity, making it hard for the network to capture subtle spectral differences in land covers in high-dimensional space.

To address challenges posed by high-dimensional data, Dai et al. [22] proposed the SDAE method. It used noise in unsupervised steps and fine-tunes with supervision, effectively alleviating the Hughes phenomenon and noise interference in high-dimensional data. Since it ignored spatial info, it often misclassified land types that looked similar in space but had tiny spectral differences. Zhao et al. [23] proposed a multi-scale cross-convolution method. It mined spatial-spectral correlation features at different scales, and fused cross-scale semantic info, effectively addressing spectral confusion and high-dimensional redundancy. However, its dataset generalization needed improvement. Mei et al. [24] proposed a group-aware hierarchical method. It divided bands into groups via grouping strategies, fused spatial neighborhood info to better utilize high-dimensional data, but lacked sufficient use of spatial details.

As GPU computing performance improved, various deep learning models had been developed. Early deep learning used shallow networks for spectral or spatial feature extraction [25,26,27,28]. Later, deep and multi-layer architectures enabled efficient fusion of spectral and spatial information. Now, multi-scale and multi-view CNNs accurately capture subtle changes in hyperspectral images [29,30]. Models combining attention mechanisms and Transformers excel at capturing long-range dependencies, improving classification accuracy and generalization [31,32]. Spectral, spatial, and central attention methods have been increasingly proposed and applied. Spectral methods exploit subtle spectral differences. Shu et al. [33] used separated attention to strengthen spectral and spatial features but lacked feature interaction and struggled with complex objects. Duan et al. [34] applied spectral attention for discriminative bands but was weak against noise. Chhapariya et al. [35] achieved high accuracy with low parameters using residual-dual branch attention, though settings relied on experience. Han et al. [36] modeled sub-pixel spectral uncertainty for robustness but could not precisely focus on core features. Spatial methods simulated ground object distributions. Multi-scale CNNs used varied receptive fields to capture diverse spatial patterns [37,38]. Ge et al. [39] proposed a pyramid network with channel-spatial separation to address fixed receptive fields and attention redundancy, though kernel scales were not fully adaptive. Central attention methods focused on key features and cross-domain fusion. Feng et al. [40] developed the CAT Transformer, using hierarchical spectral-spatial tokens to target central pixels, but it struggled with certain ground object categories. Zhang et al. [41] introduced S2CABT, which handled spectral reduction, feature extraction, and context refinement simultaneously, yet its generalization in complex scenes was limited. Jia et al. [42] presented CenterFormer, which precisely focused on core features and enhances spectral-spatial collaboration, but fell short in capturing edge details.

In unsupervised remote sensing algorithms, breakthroughs addressed challenges like scarce labels and mixed-pixel interference through spatial-spectral learning, unsupervised representation mining, low-rank sparse modeling, and graph topology analysis. Wang et al. [43] proposed OraL, a two-stage (observation-regeneration) pixel-level change detector. It narrowed the supervised performance gap but depends on initial pseudo-label quality and needed validation for extreme spectral variations. Zhou et al. [44] developed LRSnet, combining low-rank feature extraction with noise suppression and CDnet for change mining. It achieved high accuracy but struggled with large-scale pseudo-changes and hyperparameter sensitivity. Li et al. [45] introduced EDIP-Net, a two-stage unsupervised super-resolution network. It generated scene-aware coarse estimates (ZSL) and refined results (DIG) without external data, offering strong robustness but high computational costs and noise sensitivity. Wang et al. [46] created CAN, using PCA compression and attention modules for adaptive spatial-spectral feature weighting. However, it showed limited accuracy for spectrally similar objects and complex classifications. Mei et al. [47] combined multi-scale low-rank representation (for hierarchical feature separation) with bidirectional recursive filtering (for spatial-spectral enhancement). The method risked blurring fine object boundaries due to over-smoothing. Wang et al. [48] proposed a dual stochastic graph-based projection clustering method for global topological relationship mining. While scalable, it lacked spatial neighborhood integration, causing confusion for similarly distributed objects.

These algorithms had achieved good classification performance, and new architecture-based algorithms had been proposed in recent years. To address overfitting and poor generalization of models under small-sample scenarios, Hong et al. [49] proposed SpectralFormer for hyperspectral image classification, achieving breakthroughs in spectral sequence modeling via local spectral embedding (GSE) and cross-layer fusion (CAF) modules but ignoring local spectral continuity with insufficient spectral detail capture. Zhong et al. [50] proposed SSTN, which effectively addressed long-range dependency modeling in hyperspectral classification by introducing Transformer yet lacked a unified spectral-spatial joint modeling mechanism. Zhang et al. [51] proposed the SSSAN model, which simultaneously performed spatial and spectral self-attention and employed pixel-wise sliding window prediction, applying attention to each individual pixel. This resulted in a large amount of redundant computation. Moreover, the model did not incorporate spatial positional encoding, making it prone to overfitting and attention degradation in scenarios with limited training samples or complex boundaries. Li et al. [52] proposed the end-to-end CNN-based CVSSN, fusing spectral-spatial information efficiently with a center-pixel-oriented mechanism, but this mechanism amplified interference when neighborhood pixel categories were inconsistent in class boundary regions. Xu et al. [53] proposed the robust self-ensemble network (RSEN) for hyperspectral classification, achieving high accuracy with extremely few labeled samples via self-ensemble learning. Fu et al. [54] proposed ReSC-net, enhancing inter-channel non-linear expression via the ECA mechanism and optimizing deep feature representation with dual attention, but it did not consider spectral non-linear mixing and had poor adaptability to datasets with large band number differences. Cui et al. [55] proposed DEMUNet, cascading bidirectional Mamba scanning, CNN-Transformer dual-branch encoding, and U-Net decoding to aggregate long-range spectral-spatial features with linear complexity; however, it insufficiently exploited spectral 3D continuity, and bidirectional scanning plus dual-path fusion increased computation and parameters.

Although existing research has validated that the introduction of attention mechanisms or multi-scale convolution can improve the performance of hyperspectral image classification, significant gaps persist under scenarios of extreme sample scarcity. Most models rely solely on single-scale token modeling and lack explicit representation of multi-level granularity, causing spatial details to be suppressed by global averaging. Secondly, although lightweight convolutions are employed, fixed kernel sizes are used which fail to adaptively adjust the receptive field according to the target scale. This often leads to non-negligible discriminative confusion in boundary regions; and the introduction of unidimensional attention—either channel-wise or spatial-wise—lacks the joint optimization of the three-dimensional coupling among “channel, space, and context,” making it difficult to suppress noise and amplify common features. Therefore, this paper proposes a “Multi-scale and Multi-level” joint modeling framework. For the first time, it couples three-dimensional multi-path parallel convolution with a progressive channel-spatial self-attention mechanism into a unified optimization objective. This framework achieves the simultaneous recalibration of discriminative weights at the pixel, scale, and channel levels. Consequently, it effectively resolves the challenging problem of dynamic fusion of different-sized features—a dilemma that existing methods struggle to balance under small-sample conditions—thereby significantly improving both the classification accuracy and boundary preservation capability for hyperspectral images.

In this study, we concentrate on the following pivotal work:

- (1)

- To tackle the multi-scale representation challenge inherent in hyperspectral imagery, a multi-scale spectral-spatial feature extraction mechanism is suggested. By leveraging three parallel 3D convolutional pathways, the model builds receptive fields to hierarchically extract spectral–spatial features, spanning fine local textures to coarse global contexts. These convolutional operations not only strengthen local structural representations but also support channel reconstruction and feature refinement.

- (2)

- To adaptively enhance feature representations, both spatial and channel attention mechanisms are incorporated. The 3D-SE channel attention module is adopted to reinforce local semantic information and facilitate the efficient aggregation of cross-scale key features. Additionally, the CBAM mechanism is utilized to emphasize significant spectral bands and enhance focus on spatial regions of interest.

- (3)

- To capture global spectral dependencies, self-attention is adopted, and relative positional encoding is introduced to maintain the sequential order of channels. A cross-attention fusion mechanism is then leveraged to achieve bidirectional integration between the local spatial features extracted by CNN and the global spectral features modeled by Transformer.

The rest of this paper is structured in the following: Section 2 presents the main research methods of this paper, including the algorithm of the model, dataset introduction, evaluation indicators, model training strategies, loss function construction, and the experimental environment in which the model operates. In Section 3, we show and analyze the model’s experimental results, and comparative and ablation experiments are included. In Section 4, we critically discuss the advantages and drawbacks of the algorithm shown in this paper. Finally, in Section 5, we provide a comprehensive summary of this paper.

2. Research Methods

2.1. Proposed Model and Algorithm

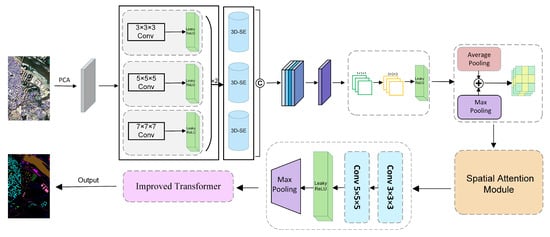

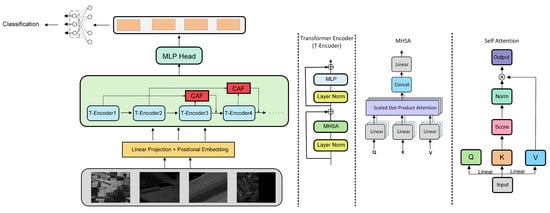

Traditional 3D-CNN architectures employ a fixed receptive field, making it difficult to adequately capture features from different-sized targets. Concurrently, the inherent limitation of the convolution operation’s receptive field hinders the capture of long-range dependencies, which compromises the model’s ability to model large-scale ground object structures [56]. To address these challenges, this paper introduces a multi-path, multi-scale parallel architecture based on the conventional 3D-CNN framework. This design enhances the diversity of the receptive field and, when combined with a hybrid pooling strategy and a 2D convolutional spatial optimization module, effectively facilitates the synergistic modeling of spectral and spatial features. Furthermore, the model integrates the Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) channel attention mechanism and the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) spatial attention mechanism. These mechanisms respectively augment feature representation from the spectral channel and spatial position dimensions, thereby enhancing the model’s capacity to focus on key spectral bands and critical spatial structures. Finally, by leveraging the self-attention from an improved Transformer architecture, a local-global feature fusion module is constructed to capture the long-distance dependencies inherent in hyperspectral remote sensing images, further boosting the overall discriminative performance of the model. Figure 1 illustrates the complete architecture of the proposed method.

Figure 1.

Architecture of the model presented in this article.

2.1.1. Multi-Scale Spectral-Spatial Feature Extraction Module

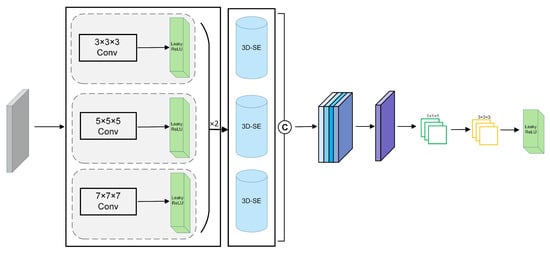

In the feature extraction stage, after the input of the hyperspectral data block, three parallel three-dimensional convolution kernel branches of 3 × 3 × 3, 5 × 5 × 5, and 7 × 7 × 7 are used to capture spectral-spatial features under different receptive fields. LeakyReLU activation functions are applied separately to introduce non-linear transformations. Smaller convolution kernels focus on modeling fine structures, such as edges, textures, and noise suppression; medium-scale convolutions are suitable for modeling medium-scale regional structures, while larger convolution kernels can better capture wide-range contextual information. Each branch internally stacks two layers of the same-scale 3D convolutional layers, which deepens the network’s non-linear modeling capabilities, and through inter-layer information integration, achieves a gradual abstraction from shallow edge responses to deep structural semantics. Multi-layer convolutional networks can maintain the original scale feature representation while enhancing the model’s semantic abstraction and context-awareness capabilities. This “deep receptive field enhancement” strategy has been widely proven to have significant advantages in image classification and object detection tasks [17].

After the 3D-SE channel attention mechanism module, the feature tensors outputted from the three scale branches are concatenated and fused, introducing a channel compression and local enhancement module. This module first uses 1 × 1 × 1 three-dimensional convolution kernels to compress the fused feature map, reducing the number of channels and suppressing redundant information while retaining key spectral-spatial information. Subsequently, 3 × 3 × 3 three-dimensional convolution kernels are introduced to enhance the modeling capability of local spatial semantics. Through element-wise weighted fusion, combined with the LeakyReLU activation function, channel dimension information reconstruction and feature enhancement are achieved. This structure is widely used in image recognition and semantic segmentation tasks, effectively compressing features and enhancing spatial modeling capabilities [57,58]. The multi-scale spectral-spatial feature extraction module is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Multi-scale Spectral-Spatial Feature Extraction Module.

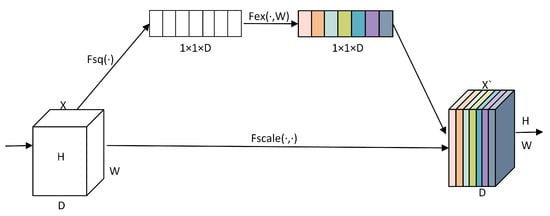

2.1.2. Channel Attention and Spatial Attention Modules

Due to the varying contributions of features extracted by 3D convolution kernels at different scales to classification, applying a uniform channel attention to the overall fusion result of multi-scale features may mask key responses at certain scales. Therefore, the 3D-SE module is independently embedded at the end of each scale branch, allowing it to learn the importance of corresponding channels within that scale separately. This facilitates fine-grained spectral enhancement and redundant suppression within each scale, enhancing the representational capacity and selectivity of multi-scale features. Figure 3 depicts the 3D-SE channel-attention module.

Figure 3.

3D-SE Channel Attention Mechanism Module.

The SE Attention block’s core idea is to model global response relationships on the channel dimension of convolutional feature maps, allowing the model to automatically learn the importance of each channel and perform weighted calibration accordingly. In the squeeze stage, global average pooling is used to aggregate the spatial features of each channel, obtaining a channel-level description vector as follows:

denotes the value of channel at position . In the excitation stage, channel weights are produced by a two-layer fully connected network, incorporating non-linear activation to enhance fitting capability. The derivation is given in the following:

, are learnable weight matrices, is the sigmoid activation function used to compress the weight range to 0 to 1. In the recalibration stage, this attention vector element-wise multiplies the original feature map to produce a weighted enhancement:

Given that the hyperspectral remote sensing images processed in this paper are five-dimensional tensors [batch, ], and the original SE module only supports 2D feature maps, a three-dimensional adaptation of the structure is carried out, focusing on modifying the pooling operation in the Squeeze stage. Specifically, a three-dimensional global average pooling is employed to compress both the spectral dimension and spatial dimensions simultaneously to extract the global responses of each channel as follows:

indicates the feature response of channel at position , resulting in a channel feature vector of length . The excitation and recalibration stage structures remain unchanged, and the output attention weights are used to weight the original 3D feature tensor.

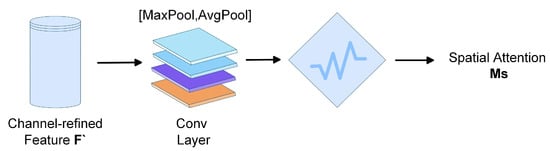

To further optimize the spatial information modeling capabilities, after the extraction and fusion pooling of a multi-scale 3D-CNN and before the 2D-CNN module, a spatial attention branch of the CBAM is introduced. This module adaptively adjusts the response intensity of each spatial position before sending the features to the 2D-CNN for spatial modeling, guiding the network to focus on key regions and suppress redundant background interference. CBAM first extracts spatial saliency features and global distribution information through max pooling and average pooling, respectively. After concatenating the two along the channel dimension, they are inputted into a 7 × 7 convolutional layer to output the spatial attention map. The spatial structure optimization module is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Spatial Attention Module.

2.1.3. Transformer Architecture

Although the model incorporates channel and spatial attention, its overall structure still mainly relies on the local receptive field of CNNs for feature weighting, lacking the capacity to uniformly model spectral–spatial relationships from a global view. To tackle this, this paper introduces an improved Transformer local–global fusion method (as shown in Figure 5) based on the existing architecture. It uses the self-attention mechanism to model long-range dependencies in hyperspectral images, thereby enhancing the overall discriminative ability [59]. The core of the Transformer is to achieve global feature interactions through self-attention, with the calculation formula as follows:

Figure 5.

Architecture diagram of the improved Transformer.

Given that directly applying the traditional Transformer to hyperspectral images leads to high computational costs, this paper adopts SpectralFormer as the backbone for spectral dimension modeling and embeds it after CNN feature extraction. A cross-dimensional interaction mechanism is also designed for fusion. First, we convert the 3D feature map extracted by the CNN (with shape (, , , )) into a sequence compatible with the Transformer. The computation process is as follows:

This flattens the image into token sequences, enabling attention application in the spectral dimension and capturing global dependencies. Then, the sequence is input into SpectralFormer for multi-head self-attention (MHSA) modeling:

Relative positional encoding is added in the spectral dimension to enhance sequential relationship modeling among channels and compensate for spatial perception deficiencies [60]. A feed-forward network (FFN) is also combined to further boost global expressiveness [61,62]. After obtaining global spectral features, a cross-dimensional cross-attention fusion (CAF) is designed for bidirectional interaction between SpectralFormer and CNN representations, with calculations as follows:

Finally, the cross-attention fused features are weighted and combined, and then input into a fully connected layer for classification:

2.2. Datasets

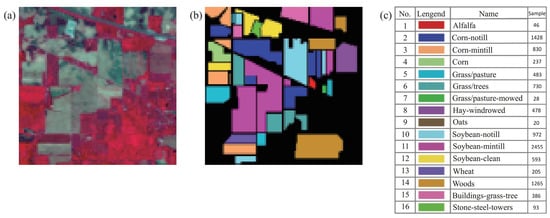

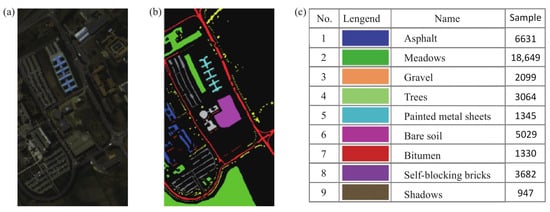

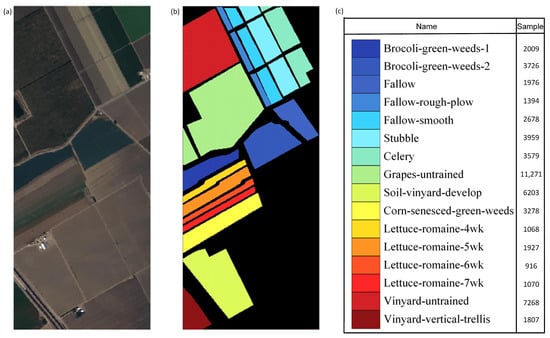

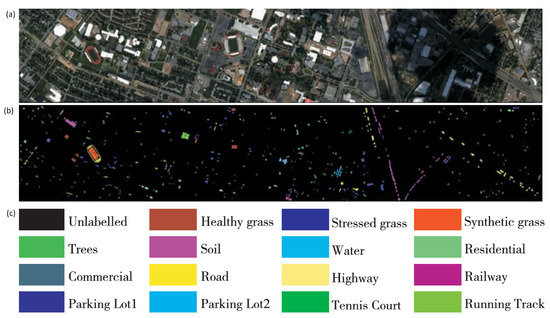

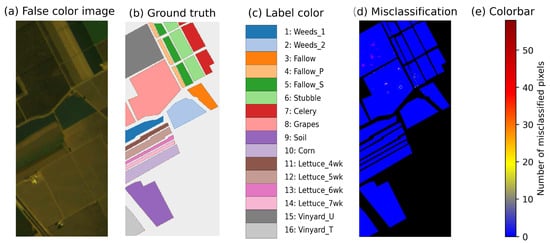

To assess the proposed model’s classification performance, four widely used hyperspectral remote sensing image datasets are employed: Indian Pines, Pavia University, Salinas Valley, and Houston 2013. Specifically, the Indian Pines dataset contains 10,249 pixels across 16 land-cover classes for classification experiments. The Pavia University dataset consists of 42,776 pixels belonging to 9 classes. The Salinas Valley dataset includes 54,129 pixels distributed over 16 classes. Finally, the Houston 2013 dataset comprises 15,029 pixels categorized into 15 classes. Table 1 and Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 show complete dataset specifications.

Table 1.

Details of the Datasets Used in This Study.

Figure 6.

Information of the Indian Pines dataset. (a) False-color image. (b) Ground truth. (c) Number of samples per class.

Figure 7.

Information of the Pavia University dataset. (a) False-color image. (b) Ground truth. (c) Number of samples per class.

Figure 8.

Information of the Salinas Valley dataset. (a) False-color image. (b) Ground truth. (c) Number of samples per class.

Figure 9.

Information of the Houston 2013 dataset. (a) False-color image. (b) Ground truth. (c) per class information.

2.3. Evaluation Metrics

To ensure a fair comparison, we train all methods using the same dataset to minimize the impact of random selection. Overall Accuracy (OA), Average Accuracy (AA), Kappa coefficient, Weighted-F1, and Macro-F1 are employed as evaluation metrics for comparing the methods [63]. OA reflects the model’s overall classification accuracy across all samples, while AA calculates the average accuracy across all categories. The Kappa coefficient quantifies inter-class confusion and is more sensitive to errors in minority classes; when used together with OA, it provides a complementary characterization of model performance from the dual perspectives of “global accuracy” and “class confusion”. The calculation methods are as follows:

Relying solely on OA makes it difficult to comprehensively reflect the model’s true performance across different categories. Therefore, this paper further employs the F1 to evaluate the classification results. The F1, by integrating Precision and Recall, is more sensitive to category distribution and can more effectively reflect the model’s recognition performance on small-sample and challenging categories. This paper adopts two calculation methods for category-specific F1: Macro-F1 and Weighted-F1. Macro-F1 completely eliminates the influence of category sample size on the metric, ensuring equal importance for each category in the evaluation. Weighted-F1, on the other hand, assigns weights to the F1 according to the sample size of each category, aligning more closely with the true data distribution and providing evaluation results that better reflect overall classification performance. By conducting a dual evaluation from both the “category equality perspective” and the “data distribution perspective,” this approach enables a more objective and comprehensive performance analysis and more accurately reveals the model’s robustness and generalization capability on imbalanced remote sensing datasets. The calculation methods are as follows:

2.4. Model Training Strategy

The optimizer employs the Adam (Adaptive Moment Estimation) method, which combines the advantages of Momentum and RMSProp, dynamically adjusting the learning rate based on first-order and second-order moment estimates during parameter updates. The fundamental update rule is as follows:

Here, represents the gradient at iteration , is the learning rate, .9 controls the decay of the first-order moment estimate, .999 sets the decay factor for the second-order moment estimate, and is a small constant for computational stability, with a default value of 10−8. To prevent gradient explosion during the early stages of training, a gradient clipping mechanism is further introduced, which restricts the gradient norm from exceeding the threshold . The computation process is as follows (where = 5.0):

2.5. Loss Function Construction

In terms of the loss function, the model employs the standard Softmax to evaluate the mismatch between predicted outcomes and actual label distributions. represents the total number of classes. is the one-hot encoded true label, and is the output probability after Softmax normalization [64]. Its mathematical form is as follows:

To prevent model overfitting and to simulate the weight-decay mechanism in the AdamW optimizer, this study incorporates an regularization term into the training objective to penalize trainable parameters such as convolutional kernels and fully connected weights. The coefficient is adaptively adjusted throughout the optimization process. Through this dynamic mechanism, the regularization strength automatically varies across different training stages: stronger regularization is imposed during the early iterations when parameter updates are highly unstable, while the penalty gradually weakens as the model converges. This design enhances training stability, reduces the risk of overfitting, and makes the overall optimization process more robust and self-regulating. The total loss function is shown in Equation (26).

is the regularization coefficient, typically set within the range of to accommodate different model and dataset complexities [65].

Furthermore, this paper adopts a combined dynamic learning rate scheduling strategy that integrates a linear Warmup phase with a Cosine Decay. This approach is designed to mitigate instability during the initial stages of training and to achieve smooth convergence in the later stages. The calculation process is as follows:

, while in the subsequent cosine annealing phase, the learning rate decays to the minimum value in the form of a cosine function, calculated as follows:

, where is the count of epochs already trained in the current cosine phase, and is the total number of periods in the cosine decay. This strategy achieves a good balance between rapid convergence in the early stage and fine optimization in the later stage, and has demonstrated strong performance in image classification, semantic segmentation, and related tasks [66].

2.6. Experimental Environment

The experimental configuration is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Experimental Environment Configuration.

3. Experiments and Results

To circumvent the spatial leakage issue caused by pixel-level random partitioning, we employed a K-Fold Cross-Validation experimental design [67]. Specifically, the entire hyperspectral image was divided into K non-overlapping subsets (patches). In each iteration, K-1 subsets were selected as the training set, while the remaining 1 subset served as the test set. This process was repeated K times, ensuring that each subset was used exactly once as the test set. This approach guaranteed an evaluation of the model’s generalization capability across different spatial locations and class distributions. In this study, we set K = 5. Within each fold, a small portion of samples was further extracted from the training set to serve as the validation set for early stopping and hyperparameter tuning during the training process. We calculated the mean results and variances as the final performance metrics. The best results are shown in bold. During the network training phase, the Adam optimizer was utilized to update parameters, with an initial learning rate of 0.0001, a batch size of 32, and 100 training epochs to ensure convergence.

3.1. Comparative Experiments

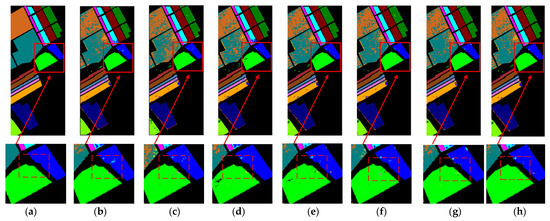

To validate the efficacy of the hyperspectral image classification method presented in this study, which integrates multi-scale feature fusion with a multi-level attention mechanism, comparative experiments are conducted between the proposed model and several state-of-the-art approaches: SpectralFormer [49], SSTN [50], SSSAN [51], CVSSN [52], RSEN [53], and DEMUNet [55]. Experiments are conducted on four widely adopted benchmark datasets: Indian Pines, Pavia University, Salinas Valley, and Houston 2013. Results are assessed with OA, AA, Kappa, Macro-F1 and Weighted-F1. In the classification maps, regions where significant classification differences exist among different models have been individually marked.

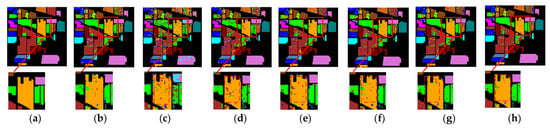

Evaluated on Indian Pines data, the model proposed in this paper outperforms the comparative methods across most metrics, demonstrating a distinct performance advantage. The Macro-F1 score reaches 0.8881, indicating that our method effectively addresses the prevalent class imbalance issue within the dataset and successfully mitigates the resultant misclassification. The Weighted-F1 score is 0.8817. Although slightly outperforming the sub-optimal model DEMUNet, it still demonstrates strong classification capability in dominant categories, with overall classification performance remaining good. Class 11 has historically been regarded as a quintessential example of a “highly confusing and difficult-to-discriminate” category. Its spectral curve exhibits only a subtle difference of 2–3 nm within the 720–760 nm red-edge region compared to the adjacent Soybean-notill and Corn-mintill classes. Furthermore, its spatial patches are fragmented, with edges intricately interspersed with roads and bare soil, making it prone to misclassification by conventional methods. Our proposed method achieves a classification accuracy of 0.9333 for this class, the highest among all compared algorithms. This result fully substantiates the efficacy of the introduced Transformer self-attention mechanism in capturing long-range spatial-spectral dependencies. The dual-attention mechanism, comprising SE and CBAM, further improves the model’s performance: in the channel dimension, it amplifies the weights of the red-edge features while suppressing noise from bare soil; in the spatial dimension, it generates a high-response mask outlining the plant contours. The specific effects are illustrated in Figure 10 and detailed in Table 3.

Figure 10.

Classification maps obtained with different methods on the Indian Pines dataset: (a) Reference (b) Spectral-Former, (c) SSTN, (d) SSSAN, (e) CVSSN, (f) RSEN, (g) DEMUNet, (h) Ours.

Table 3.

Quantitative classification results on the Indian Pines dataset.

Evaluated on Pavia University dataset, the presented method achieves a Weighted-F1 score significantly superior to all comparative algorithms, which fully demonstrates that it not only maintains robust high performance on dominant classes with extremely skewed category distributions and large disparities in sample size, but also leverages the synergy of multi-scale 3D convolution and dual attention (SE-CBAM) to transform the abundant sample advantages of dominant classes into more discriminative global decision boundaries, thereby avoiding the polarization of overfitting on large classes and underfitting on small classes typical of traditional methods. For category 2 with complex terrain features, the classification accuracy reaches 0.9934, still surpassing all comparative methods. This directly validates the effectiveness of the “multi-scale + channel-spatial dual attention” mechanism: it amplifies subtle spectral differences in edge pixels and suppresses redundant background in mixed pixels, ultimately enabling the model to output high-confidence joint feature representations even under severe spatial-spectral confusion in class 2, thus achieving comprehensive leadership in both overall and local performance. For category 5, several classical methods achieve zero false detection, whereas the classification accuracy of our proposed method nears 100%, indicating strong classification capability in easily identifiable categories. For category 3 and category 7, our method shows minor shortcomings with relatively small overall gaps, likely because the spatial features of these categories are relatively simple, rendering the rich feature mechanisms somewhat redundant and slightly affecting classification accuracy. The specific effects are illustrated in Figure 11 and detailed in Table 4.

Figure 11.

Classification maps obtained with different methods on the Pavia University dataset: (a) Reference (b) Spectral-Former, (c) SSTN, (d) SSSAN, (e) CVSSN, (f) RSEN, (g) DEMUNet, (h) Ours.

Table 4.

Quantitative classification results on the Pavia University dataset.

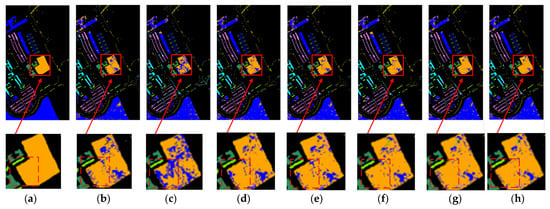

On the Salinas Valley dataset, the proposed model attains an Overall Accuracy (OA) of 0.9929, surpassing all comparative methods. Furthermore, the Average Accuracy (AA) reaches 0.9949, demonstrating exceptional class balance, while the Kappa coefficient of 0.9916 further corroborates the method’s stability and generalization capability. The classification accuracy of classes 1, 2, and 3 reached 0.9995, 0.9998, and 0.9836, respectively, which is higher than other comparison methods, demonstrating the effectiveness of multi-scale spatial-spectral fusion and attention mechanism in distinguishing fine-grained classes. These three classes exhibit extreme spectral similarity and subtle spatial texture differences; all show comparable reflectance slopes at the 550 nm green peak and 700 nm red edge, and their adjacent plots with interlaced strips often lead to misclassification in traditional methods due to “inter-class spectral confusion and intra-class spatial heterogeneity”. Ultimately, the proposed method accomplishes fine-grained separation of these three easily confused classes with ultra-high accuracy, comprehensively outperforming the second-best algorithm. This success fully reveals the progressive amplification pathway—from differential feature extraction via 3D convolution, to spectral weighting by SE, and spatial recalibration by CBAM—wherein subtle differences are progressively magnified across both channel and spatial dimensions. The performance on category 8 and category 15 is relatively unsatisfactory, prompting us to conduct further error visualization analysis (as shown in Figure 12). The qualitative and quantitative analysis results of the model are presented in Figure 13 and Table 5, respectively.

Figure 12.

Misclassification Visualization on the Salinas Valley Dataset.

Figure 13.

Classification maps obtained with different methods on the Salinas Valley dataset: (a) Reference (b) Spectral-Former, (c) SSTN, (d) SSSAN, (e) CVSSN, (f) RSEN, (g) DEMUNet, (h) Ours.

Table 5.

Quantitative classification results on the Salinas Valley dataset.

As shown in Figure 12d, misclassified pixels of Class 8 (Grapes) appear as a few local bright spots, mostly along field borders or in sparsely vegetated areas. Their reflectance is highly variable because of differences in vine density, exposed soil and shadowing, leading to substantial overlap with the spectral signatures of Fallow and Soil; edge pixels further exhibit mixed-pixel characteristics. For Class 15 (Vinyard), errors concentrate in untrimmed inter-rows where weeds are intermixed with vines, displaying a “spotty–diffuse” pattern; the weeds’ elevated green peak and shallow red trough make the canopy appear “excessively green”, causing the model to label it as grape foliage. Although SE, CBAM and Transformer modules are employed to enhance spectral-spatial modeling, the attention mechanisms in SE and CBAM are readily distracted by high-gradient edge regions, while the global attention of Transformer attenuates fine-grained spectral differences after patch embedding, thereby amplifying local noisy pixels and producing small-area misclassification. Overall, the model still has limited capability in handling mixed pixels.

On the Houston 2013 dataset, the scene is complex, the classes are diverse, and the samples are highly imbalanced. Our model outperforms all comparative methods across multiple metrics, including AA, Kappa, and Weighted-F1. This indicates that the multi-scale 3D convolution first captures cross-scale textures of roofs, roads, and vegetation; the SE-CBAM dual attention mechanism suppresses noise along the spectral axis and sharpens edges; and the Transformer module further establishes long-range dependencies across the full image. Together, these components enable balanced recognition across all 16 classes while maintaining robust performance on dominant classes, achieving dual optimization in both overall performance and statistical consistency. The specific effects are illustrated in Figure 14 and detailed in Table 6.

Figure 14.

Classification maps obtained with different methods on the Houston 2013 dataset: (a) Reference (b) Spectral-Former, (c) SSTN, (d) SSSAN, (e) CVSSN, (f) RSEN, (g) DEMUNet, (h) Ours.

Table 6.

Quantitative classification results on the Houston 2013 dataset.

The experimental results on the four datasets demonstrate that the classification method proposed in this paper exhibits outstanding overall performance. Compared with methods such as SpectralFormer, SSTN, SSSAN, CVSSN, RSEN, and DEMUNet, the proposed method achieves improvements in OA, AA, and Kappa coefficient across all datasets. The multiscale 3D convolutional operations, through spectral subdivision and spatial blocking mechanisms, not only fully exploit the physicochemical information embedded in high-dimensional spectral signals, but also effectively leverage spatial context to mitigate interference from mixed pixels and noise. By embedding the dual attention mechanism (SE and CBAM) into the 3D convolutional backbone, the model significantly enhances the adaptive suppression of noisy bands while simultaneously improving recognition accuracy for edge and small targets. The spatial attention submodule of CBAM performs max-pooling and average-pooling along the spectral axis on the multiscale 3D feature maps to generate a 2D spatial weight map. This weight map explicitly amplifies regions with significant edge gradients while suppressing homogeneous backgrounds. For small targets, the channel attention highlights the spectral bands most relevant to the target, while the spatial attention generates high-response weights within the target’s local window, suppressing surrounding background interference. Spectral signatures of edge pixels are often affected by adjacent endmember mixing, leading to frequent misclassifications in traditional CNNs. The dual attention mechanism, through a “channel + spatial” dual gating strategy, preserves the effective spectral features of edge pixels while suppressing mixed noise, thereby enhancing classification confidence for these pixels. The Transformer self-attention mechanism completes the final piece of the puzzle in the hyperspectral classification network, complementing the “convolution + dual attention” framework. In the spectral dimension, it establishes global dependencies across hundreds of bands, effectively distinguishing subtle spectral differences. In the spatial dimension, it overcomes the limitations of local receptive fields by aggregating semantic context from the entire image, thereby achieving true global context modeling.

To further evaluate model behavior under extremely small-sample conditions, we conduct restricted-sample experiments using only 5% and 10% of the original training data. On the SA and PU datasets, the proposed approach still reaches 0.9212 and 0.9234 overall accuracy, respectively. Reducing the training set from 100% to 10% decreased OA by only 0.05~0.07 on each dataset, indicating robust performance even when training data are severely limited. At 5% of the training data the model continues to deliver high accuracy, demonstrating its ability to extract discriminative spectral–spatial features in extreme few-shot scenarios. Meanwhile, performance improves steadily as more samples are added, gradually approaching saturation with the full training set; detailed results are given in Table 7.

Table 7.

Small-Sample Performance Across Different Datasets.

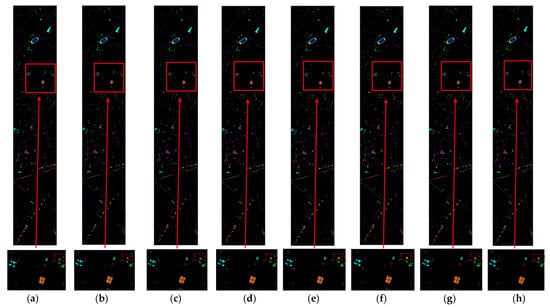

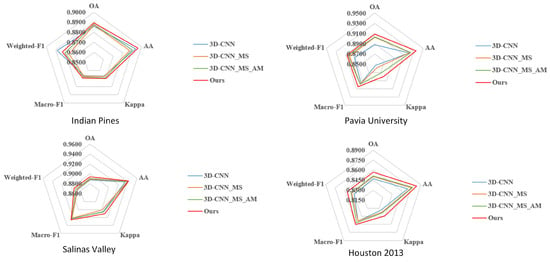

3.2. Ablation Study

To evaluate the efficacy of the improvement strategies introduced in this classification method and to investigate the specific impacts of these different strategies on model performance, this section conducts ablation experiments. For this purpose, starting from a baseline 3D-CNN model, the following components are progressively introduced: a multi-scale spectral-spatial feature extraction module (3D-CNN_MS), channel and spatial attention mechanisms (3D-CNN_MS_AM), and finally a local-global feature fusion module (Ours). The experimental results are analyzed by using the aforementioned datasets and evaluation metrics, with the overall outcomes illustrated in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Comparison of classification metrics for diverse methods across datasets.

The experimental results demonstrate that after incorporating the multi-scale spectral-spatial feature extraction module (3D-CNN_MS), the model achieves improvements in overall classification accuracy, average classification accuracy, Kappa coefficient, and F1-Score across all datasets compared to the baseline 3D-CNN model. This demonstrates that this structure succeeds in more thoroughly extracting spatial and spectral features at different scales in hyperspectral remote sensing images, thereby enhancing feature representation capability and model performance. Furthermore, with the introduction of channel and spatial attention mechanisms (3D-CNN_MS_AM), the model’s performance improves again, particularly on the Pavia University and Salinas Valley datasets. This suggests that attention mechanisms play a crucial role in suppressing redundant information and highlighting key features, further strengthening the model’s discriminative ability. Finally, after incorporating the Transformer-based local-global feature fusion module (Ours), the model attains optimal performance on every metric, with especially significant improvements in OA and Kappa coefficient on structurally complex datasets such as Houston 2013 and Pavia University. This demonstrates that the introduced Transformer structure can model broader contextual dependencies, effectively compensating for the limitations of convolutional models in global modeling. It promotes richer local-global feature fusion, boosting both classification accuracy and stability.

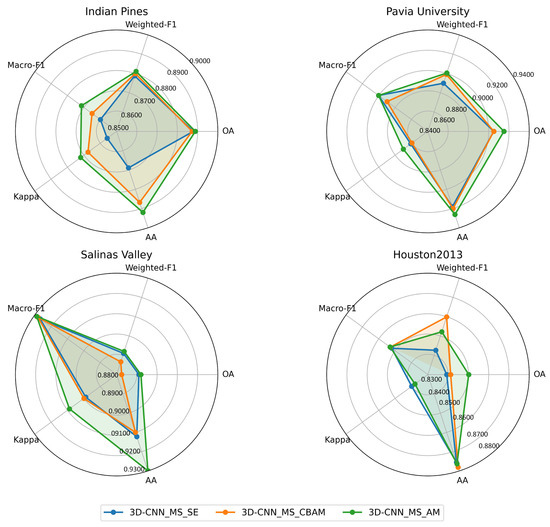

To further analyze the independent effects and synergistic gains of attention mechanisms, this study further supplemented ablation experiments to evaluate the individual contributions of the SE and CBAM. The newly added groups include 3D-CNN_MS with only SE (3D-CNN_MS_SE) and 3D-CNN_MS with only CBAM (3D-CNN_MS_CBAM), which are compared with the 3D-CNN_MS_AM group (with the synergistic combination of SE and CBAM). From the multi-indicator distribution in the radar chart, it can be observed that when the SE or CBAM is introduced individually, the model’s performance in various tasks is superior to that of the basic 3D-CNN_MS, but the improvement is limited. In contrast, the 3D-CNN_MS_AM group, which combines SE and CBAM, achieves a more significant leap in performance across most indicators. The results clearly demonstrate that SE and CBAM do not simply produce additive effects; instead, they form a synergistic gain under the complementary mechanism of channel attention and spatial attention, serving as one of the key factors for enhancing model performance. The experimental results are shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Synergistic Performance Analysis of SE and CBAM.

3.3. Performance Analysis

Table 8 presents the computational complexity of the proposed method compared with other models. Our model achieves a superior balance between efficiency and representational capacity. Although the model has a relatively large number of parameters due to the introduction of the Transformer structure, it maintains high inference efficiency. This is mainly because the computational structure is highly parallelized and the computation paths are well-organized. From the overall architecture shown in Figure 1, it can be clearly seen that the input is first preprocessed with PCA and mapped into a relatively compact low-dimensional space, directly reducing the computational base of the convolutional and attention modules and avoiding the extra overhead caused by high-dimensional inputs in deep layers. Next, we use small 3 × 3 × 3 convolutional kernels to extract local spectral–spatial features, enabling local representations to be computed at very low cost and providing efficient features for subsequent global modeling. Channel attention (SE) and spatial attention (CBAM) are then sequentially introduced; and their adaptive reweighting mechanisms enhance important features and suppress redundant information, significantly improving representational efficiency and enabling the model to achieve higher information density. The improved Transformer structure optimizes the patch processing pipeline, significantly reducing the number of attention tokens. The main operations of the network consist of convolutions and matrix multiplications, both of which are highly parallelizable on GPUs, allowing large-scale parameters to be executed in batch with high throughput. This “parameter-concentrated yet computation-controlled” design enables the model to maintain very low inference latency while achieving high accuracy, striking a dual balance between performance and efficiency.

Table 8.

Model Computational Complexity on the PU Dataset.

Some comparative models adopt complex mechanisms such as multi-scale pyramids, recursive stacking, and adaptive neighborhood construction. These architectures often involve numerous serial dependencies, multi-branch merging, and frequent shape-varying feature map operations, making it difficult to achieve true parallelism on GPUs. Additionally, some modules require dynamically generating attention weights or performing complex spatial resampling during inference. The scattered computation paths and complex scheduling ultimately lead to significantly slower inference. Specifically, the SSSAN model applies both spatial and spectral self-attention on high-dimensional hyperspectral patches, generating a large number of tokens. The computational complexity of self-attention grows quadratically with the number of tokens. Moreover, SSSAN employs a pixel-wise sliding window prediction, requiring the two attention branches to be recalculated for each overlapping patch, resulting in substantial redundant computation. During inference, the model frequently constructs attention matrices and performs high-dimensional inner products and normalization operations, incurring considerable memory access overhead and computational delay.

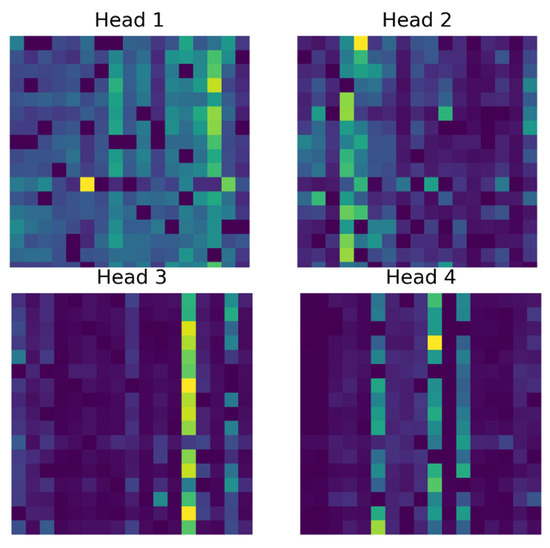

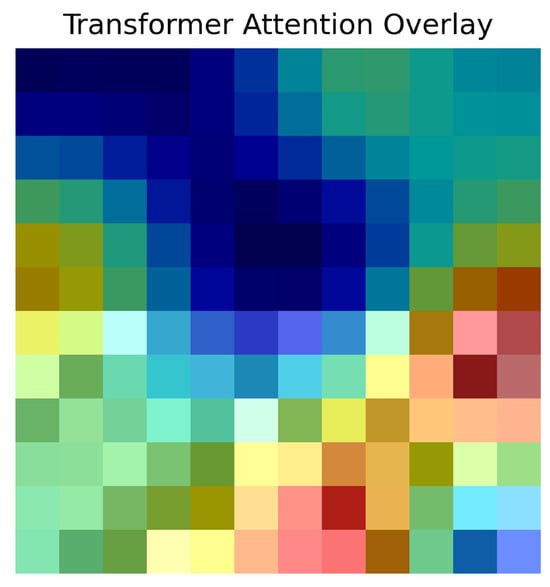

To further verify the interpretability of the proposed model during the feature extraction process and to evaluate the effectiveness of its attention mechanism, a visualization analysis of the multi-head attention weights in the Transformer model was conducted. This analysis allows an intuitive observation of the regions that the model focuses on in the spatial–spectral domain, revealing its capability to model features in complex areas such as land-cover boundaries and mixed pixels. Figure 17 illustrates the attention weight distributions of different attention heads in the proposed Transformer model. It can be observed that the attention heads exhibit distinct focus patterns across spatial and spectral dimensions, indicating that the multi-head attention mechanism successfully captures diverse spatial–spectral dependencies. Some attention heads show concentrated responses in specific spectral channels, while others mainly focus on spatial boundary regions of land-cover classes. Figure 18 presents the integrated attention overlay map obtained by averaging the multi-head attention matrices. The integrated attention map reveals that the model assigns higher attention weights to the boundaries of land-cover classes and mixed pixels—areas that are typically difficult to distinguish by using conventional methods. This finding demonstrates that the Transformer effectively models spatial contextual relationships, thereby enhancing the discriminative capability of the learned feature.

Figure 17.

Attention distributions of four heads.

Figure 18.

Integrated attention overlay.

4. Discussion

In this paper, we propose a novel remote sensing image classification model that utilizes multi-scale feature fusion, a multi-level attention mechanism (SE and CBAM), and a Transformer self-attention module to realize effective integration of local and global features. Ultimately, our model achieves leading classification accuracy on four benchmark datasets: Indian Pines, Pavia University, Salinas Valley, and Houston 2013. Compared to baseline models, our approach employs multi-scale feature fusion and a multi-level attention mechanism. Multi-scale convolution breaks free from the confines of a fixed, single-scale receptive field. The channel attention (3D-SE) performs band selection, effectively suppressing noise and water absorption bands. While algorithms like CVSSN demonstrate the utilization of spatial and spectral information and can efficiently fuse them, they exhibit deficiencies in identifying class boundary regions. Our CBAM-style spatial attention focuses on positional information, enhancing edges and small targets. The cascaded combination of these two attentions forms a multi-level recalibration mechanism, enabling the network to provide high-confidence discrimination for pixels that are “spectrally similar but spatially different” or “spatially similar but spectrally distinct”. The global self-attention establishes long-range dependencies between “any pixel and any band”, addressing the limited receptive field problem of traditional convolutions. Concurrently, positional encoding preserves spatial location information, allowing the network to perceive relationships between pixels that are spectrally similar but spatially distant, or spatially adjacent but spectrally different. Local CNN features (with strong inductive bias) and global Transformer features (with high expressive power) are fused layer by layer through gating or cross-attention mechanisms. This preserves the translation equivariance of convolutions while introducing the dynamic weights, ensuring the network maintains stable performance and significantly reduces edge misclassification.

Despite the significant advantages demonstrated by our method, it also has some limitations. Our model exhibits suboptimal performance on certain classes within the four training datasets. This may stem from the joint contribution of the global self-attention and the CNN’s dual attention, which amplifies the “tail dilution” effect. In the global softmax of the Transformer’s long-range attention, the feature responses of rare classes are suppressed as they are dominated by neighboring majority-class pixels, causing a sharp drop in recall for the extremely small classes. Overall, our model shows a tendency of being “farmland-friendly and city-sensitive” in terms of recall. It achieves near-zero missed detections in scenarios with low-to-medium-resolution imagery, continuous land parcels, and sufficient training samples, such as the Indian Pines, Salinas Valley, and Houston 2013 datasets. The spatial resolutions of these three datasets range from 2 to 20 m, where farmland or suburban parcels are distributed in large, continuous areas with high spectral homogeneity and few mixed edge pixels. This indicates that our spectral-spatial feature fusion strategy is highly effective for large-scale homogeneous regions. However, the recall is less ideal in the high-resolution urban scene of Pavia University. The very high resolution exposes the sharp boundaries of roofs, roads, and trees, resulting in a large number of mixed edge pixels with complex spectra. The model shows a slight weakness in distinguishing mixed edge pixels.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposed a novel hyperspectral image (HSI) classification framework that effectively integrates multi-scale feature fusion with a hierarchical attention mechanism. To overcome the limitations of conventional 3D-CNNs—such as restricted receptive fields and inadequate global contextual modeling—our model incorporates three key technical contributions: (1) a multi-path parallel 3D convolutional structure for adaptive multi-scale spectral-spatial feature extraction; (2) a coordinated channel-spatial attention mechanism that dynamically enhances discriminative features while suppressing spectral noise and spatial redundancy; and (3) a lightweight Transformer module with spectral-relative positional encoding, which efficiently captures long-range dependencies between spatio-spectral tokens. By bridging the local feature learning capability of CNNs with the global representational power of Transformers, the proposed approach establishes an end-to-end architecture that achieves a more coherent integration of local and global information.

Extensive experiments on four public HSI benchmarks demonstrate the superiority of our method. It consistently outperforms state-of-the-art models in overall accuracy, recall, and boundary preservation, particularly under limited and imbalanced training samples. Notably, the model achieves a recall higher than 0.85 for minority classes and maintains over 90% overall accuracy even in challenging few-shot scenarios. These results validate its robustness and strong generalization across diverse landscapes and category distributions.

In future work, we plan to extend this research in two main directions. First, we will explore contrastive self-supervised pre-training on large-scale unlabeled HSI sequences to mine inherent spectral-spatial consistencies, with the goal of enabling few-shot or even zero-shot transfer learning for regions with scarce labels. Second, we intend to investigate neural architecture search (NAS) strategies and hybrid convolution-attention modules to dynamically adapt network structures—such as kernel scales and attention windows—to varying sensor characteristics, spatial resolutions, and land-cover complexities. The ultimate objective is to develop a general-purpose, cross-platform HSI analysis engine with good scalability and applicability to a wide range of remote sensing tasks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.H., W.S. and C.L.; methodology, W.S. and C.L.; software, W.S.; validation, W.S.; formal analysis, W.H., Y.L. and W.S.; investigation, W.S.; resources, W.S. and C.L.; data curation, W.S.; writing—original draft preparation, W.S. and C.L.; writing—review and editing, W.H., Y.L. and W.S.; visualization, W.H., Y.L. and W.S.; supervision, W.H., Y.L. and W.S.; project administration, W.H. and Y.L.; funding acquisition, W.H., Y.L. and L.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Sichuan Science and Technology Program under Grant 2024YFFK0414, and supported in part by Key Projects of Global Change and Response of Ministry of Science and Technology of China under Grant 2020YFA0608203.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are readily available at the openly accessible repository linked herein freely: https://www.ehu.eus/ccwintco/index.php/Hyperspectral_Remote_Sensing_Scenes (accessed on 20 September 2025); https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1N9czbGBoJXVHycuXoTq8ba32eebydYPp (accessed on 5 October 2025). The code is publicly available at https://github.com/CoffeeChocolate1/CSMT (accessed on 6 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sun, H.; Zheng, X.; Lu, X. A supervised segmentation network for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 2810–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, M.; Huang, J.J.; Zhang, C.; Ye, F.W.; Pan, W. Anew approach for mineral mapping using drill-core hyperspectral image. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bernabé, S.; García, C.; Igual, F.D.; Botella, G.; Prieto-Matias, M.; Plaza, A. Portability study of an OpenCL algorithm for automatic target detection in hyperspectral images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 9499–9511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Wang, Z.; Hu, M.; Zhai, G. Active learning plus deep learning can establish cost-effective and robust model for multichannel image: A case on hyperspectral image classification. Sensors 2020, 20, 4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamisi, P.; Dalla Mura, M.; Benediktsson, J.A. A survey on spectral–spatial classification techniques based on attribute profiles. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2014, 53, 2335–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, R.; Alhichri, H.; Bazi, Y. Selective data augmentation approach for remote sensing scene classification. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computer and Information Sciences (ICCIS), Sakaka, Saudi Arabia, 13–15 October 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hamida, A.B.; Benoit, A.; Lambert, P.; Amar, C.B. 3D deep learning approach for remote sensing image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 4420–4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Huang, Y.; Wei, L.; Zhang, F.; Li, H. Deep convolutional neural networks for hyperspectral image classification. J. Sens. 2015, 2015, 258619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Du, S. Spectral–spatial feature extraction for hyperspectral image classification: A dimension reduction and deep learning approach. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 54, 4544–4554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Li, B.; Chen, H. Multi-scale 3D deep convolutional neural network for hyperspectral image classification. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Beijing, China, 17–20 September 2017; pp. 3904–3908. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, D.; Luo, B. CSA-MSO3DCNN: Multiscale octave 3D-CNN with channel and spatial attention for hyperspectral image classification. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, L.; Ghamisi, P.; Zhu, X.X. Deep recurrent neural networks for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 3639–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ding, M.; Pižurica, A. Group convolutional neural networks for hyperspectral image classification. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Taipei, Taiwan, 22–25 September 2019; pp. 639–643. [Google Scholar]

- Qing, Y.; Huang, Q.; Feng, L.; Qi, Y.; Liu, W. Multiscale feature fusion network incorporating 3D self-attention for hyperspectral image classification. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Krishna, G.; Dubey, S.R.; Chaudhuri, B.B. HybridSN: Exploring 3D–2D CNN feature hierarchy for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 17, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Shen, Q. Spectral–spatial classification of hyperspectral imagery with 3D convolutional neural network. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Z.; Li, J.; Luo, Z.; Chapman, M. Spectral–spatial residual network for hyperspectral image classification: A 3D deep learning framework. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 56, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Manna, S.; Song, T.; Bruzzone, L. Attention-based adaptive spectral–spatial kernel ResNet for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 59, 7831–7843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Jiao, L.; Liu, F.; Yang, S.; Wang, J. Residual spectral–spatial attention network for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 59, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Xu, S.; Jiang, Z.; Yuan, Y. Central Pixel-Based Dual-Branch Network for Hyperspectral Image Classification. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; He, X.; Guo, S.; Liu, S.; Ji, F.; Ruan, H. Research on hyper-spectral remote sensing image classification by applying stacked de-noising auto-encoders neural network. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 21219–21239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Qiu, T.; Liu, G. Hyperspectral Remote Sensing Image Classification Based on Multi-scale Cross Graphic Convolution. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.14804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; Song, C.; Ma, M.; Xu, F. Hyperspectral image classification using group-aware hierarchical transformer. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5539014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Pun, C.-M. Multiscale superpixel-based hyperspectral image classification using recurrent neural networks with stacked autoencoders. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2020, 22, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, R.L.; Liu, Q.S.; Hong, D.F.; Ghamisi, P. Cascaded recurrent neural networks for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 5384–5394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshaghani, M.; Davari, A.; Hatamian, F.N.; Maier, A.; Riess, C. Bayesian convolutional neural networks for limited data hyperspectral remote sensing image classification. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.09250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.N.; Liu, Q.W.; Du, B.; Zhang, L.P. Weighted feature fusion of convolutional neural network and graph attention network for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 31, 1559–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Lei, Z.; Liu, L.; Ma, K.; Shang, R.; Jiao, L. Efficient evolutionary multi-scale spectral-spatial attention fusion network for hyperspectral image classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 262, 125672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, R.; Yang, J.; Feng, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, S. Hyperspectral image classification based on ConvGRU and spectral-spatial joint attention. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 174, 112949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wan, Y.; Ma, A.; Zhong, Y. A lightweight multi-scale and multi-attention hyperspectral image classification network based on multi-stage search. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5509418. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; He, M.; Chen, Q.; Sun, L.; Ma, C. Integrating multi-scale spatial-spectral shuffling convolution with 3D lightweight transformer for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote. Sens. 2025, 18, 5378–5394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Tang, S.; Yu, Z.; Wu, X.-J. Spatial–spectral split attention residual network for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 16, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Chen, C.; Fu, M.; Li, Y.; Gong, X.; Luo, F. Dimensionality reduction via multiple neighborhood-aware nonlinear collaborative analysis for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 9356–9370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhapariya, K.; Buddhiraju, K.M.; Kumar, A. A deep spectral–spatial residual attention network for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 15393–15406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Yang, J.; Gao, L.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, B.; Chanussot, J. Subpixel spectral variability network for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5504014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Yang, R. Lithological classification by hyperspectral remote sensing images based on double-branch multi-scale dual-attention network. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 14726–14741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Sheng, R.; Chen, Z.; Liu, H.; Xu, S.; Zhang, B. Multiscale random-shape convolution and adaptive graph convolution fusion network for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5508414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Wang, L.; Liu, M.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, Y.; Pan, H.; Liu, Y. Pyramidal multiscale convolutional network with polarized self-attention for pixel-wise hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5516017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, G.; Jia, X.; Yin, J. CAT: Center attention transformer with stratified spatial–spectral token for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5615415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Mi, P.; Han, D. Spectral-spatial center-aware bottleneck transformer for hyperspectral image classification. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Zhang, X.; Meng, H.; Xia, S.; Jiao, L. CenterFormer: A center spatial-spectral attention transformer network for hyperspec tral image classification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 5523–5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, X.; Peng, Z.; Tian, S.; Zhang, T.; Tang, X.; Jiao, L. Oral: An observational learning paradigm for unsupervised hyperspectral change detection. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 5380–5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; He, Z.; Dong, J.; Li, Y.; Ren, J.; Plaza, A. Low-Rank and Sparse Representation Meet Deep Unfolding: A New Interpretable Network for Hyperspectral Change Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zheng, K.; Gao, L.; Han, Z.; Li, Z.; Chanussot, J. Enhanced deep image prior for unsupervised hyperspectral image super-resolution. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5504218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Yang, A.; Cui, Z.; Ding, Y.; Xue, Y.; Su, Y. Capsule attention network for hyperspectral image classification. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L.U.; Jiatian, L.I.; Wen, L.I.; Mihong, H.U.; Jiaxin, Y.A.N.G. Fusion of Multiscale Low-rank Representation and Two Way Recursive Filtering for Hyperspectral Image Classification. Remote Sens. Technol. Appl. 2024, 39, 393–404. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Cui, Z.; Lan, Y.; Zhang, C.; Xue, Y.; Su, Y.; Li, A. Large-Scale Hyperspectral Image-Projected Clustering via Doubly Stochastic Graph Learning. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Han, Z.; Yao, J.; Gao, L.; Zhang, B.; Plaza, A.; Chanussot, J. SpectralFormer: Rethinking hyperspectral image classification with transformers. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4509416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.L.; Li, Y.; Ma, L.F.; Li, J.; Zheng, W.-S. Spectral spatial transformer network for hyperspectral image classification: A factorized architecture search framework. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5514715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.M.; Sun, G.Y.; Jia, X.P.; Wu, L.X.; Zhang, A.Z.; Ren, J.C.; Fu, H.; Yao, Y. Spectral-spatial self-attention networks for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5512115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.S.; Liu, Y.K.; Xue, G.K.; Huang, Y.W.; Yang, G.P. Exploring the relationship between center and neighborhoods: Central vector oriented self-similarity network for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 33, 1979–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Du, B.; Zhang, L. Robust Self-Ensembling Network for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 3780–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, C.; Du, B.; Zhang, L.P. ReSC-net: Hyperspectral image classifi cation based on attention-enhanced residual module and spatial-channel attention. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5518615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Zhang, L. DEMUNet: Dual Encoder Mamba U-Net for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 19, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Xu, W.; Yang, M.; Yu, K. 3D convolutional neural networks for human action recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2012, 35, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A.; Liu, W.; et al. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, X.; Pan, E.; Ma, Y.; Dai, X.; Huang, J.; Fan, F.; Du, Q.; Zheng, H.; Ma, J. Spectral-spatial attention networks for hyperspectral image classification. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Slavkovikj, V.; Verstockt, S.; De Neve, W.; Van Hoecke, S.; Van de Walle, R. Hyperspectral image classification with convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2015, 23rd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, New York, NY, USA, 26–30 October 2015; pp. 1159–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.05101. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, P.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; Noordhuis, P.; Wesolowski, L.; Kyrola, A.; Tulloch, A.; Jia, Y.; He, K. Accurate, large minibatch sgd: Training imagenet in 1 hour. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.02677. [Google Scholar]

- Nalepa, J.; Myller, M.; Kawulok, M. Validating hyperspectral image segmentation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 16, 1264–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).