Enhanced Co-Registration Method for Long-Baseline SAR Images

Highlights

- An enhanced fine co-registration method for long-baseline InSAR is proposed, integrating an elevation-dependent term to compensate for terrain-induced local offsets.

- Validated with China’s LuTan-1 (LT-1) satellite data across two distinct test sites (Madrid, Spain; Shannan, China), the method significantly improves interferometric coherence and Digital Elevation Model (DEM) accuracy in rugged terrain.

- Addresses the inapplicability of conventional polynomial models in complex terrain under long-baseline conditions, advancing high-quality InSAR processing.

- Provides a reliable technical co-registration solution for China’s LuTan-1 (LT-1) and similar long-baseline SAR satellite missions, facilitating precise topographic mapping and the development of interferometry-related applications.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- To investigate the effect of terrain height on the co-registration of long-baseline SAR images.

- (ii)

- To propose an enhanced model for the fine co-registration of a long-baseline InSAR pair.

- (iii)

- To evaluate the performance of the proposed method for DEM retrieval using L-band LuTan-1 SAR data.

2. Research Background

3. Methodology

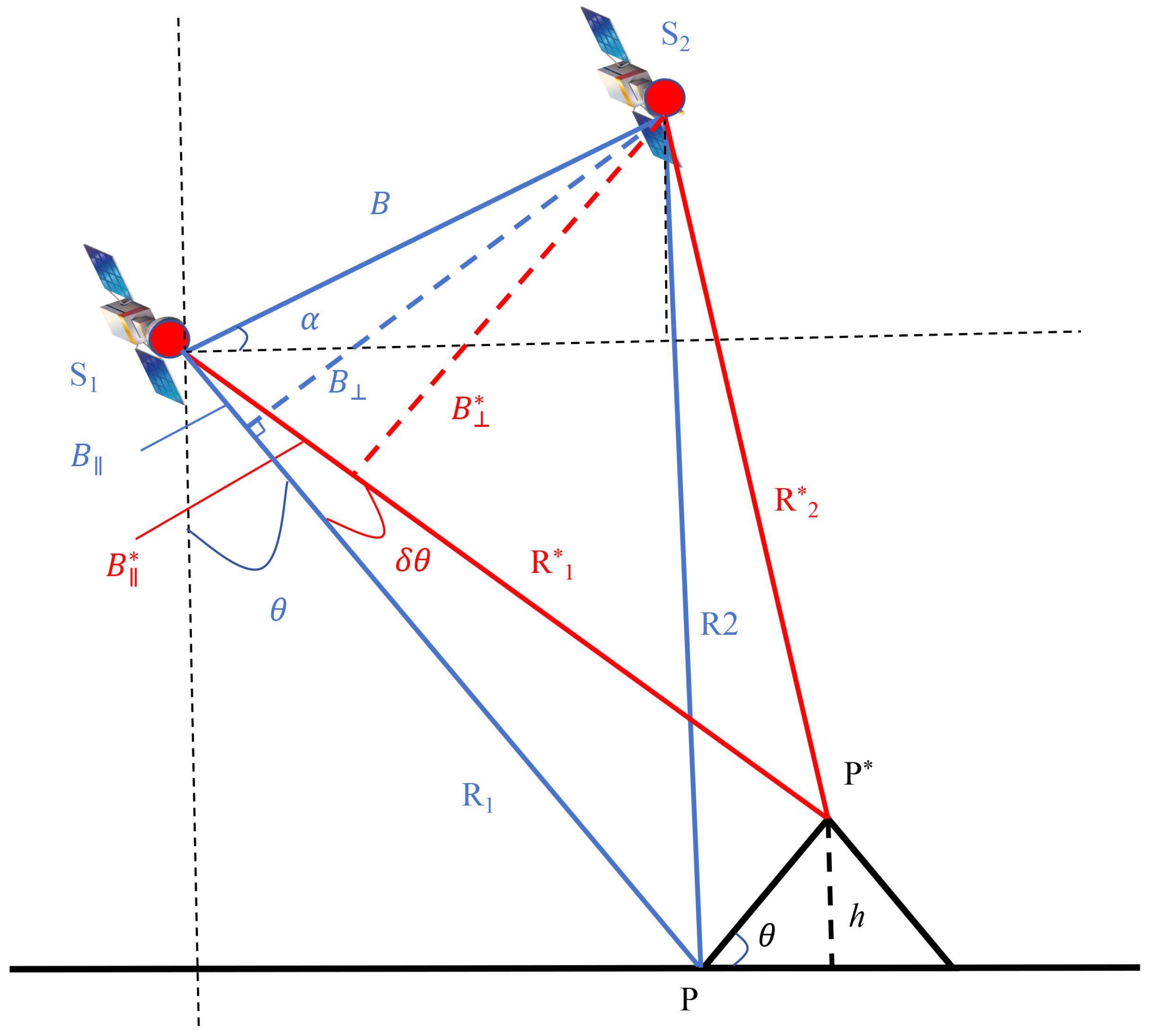

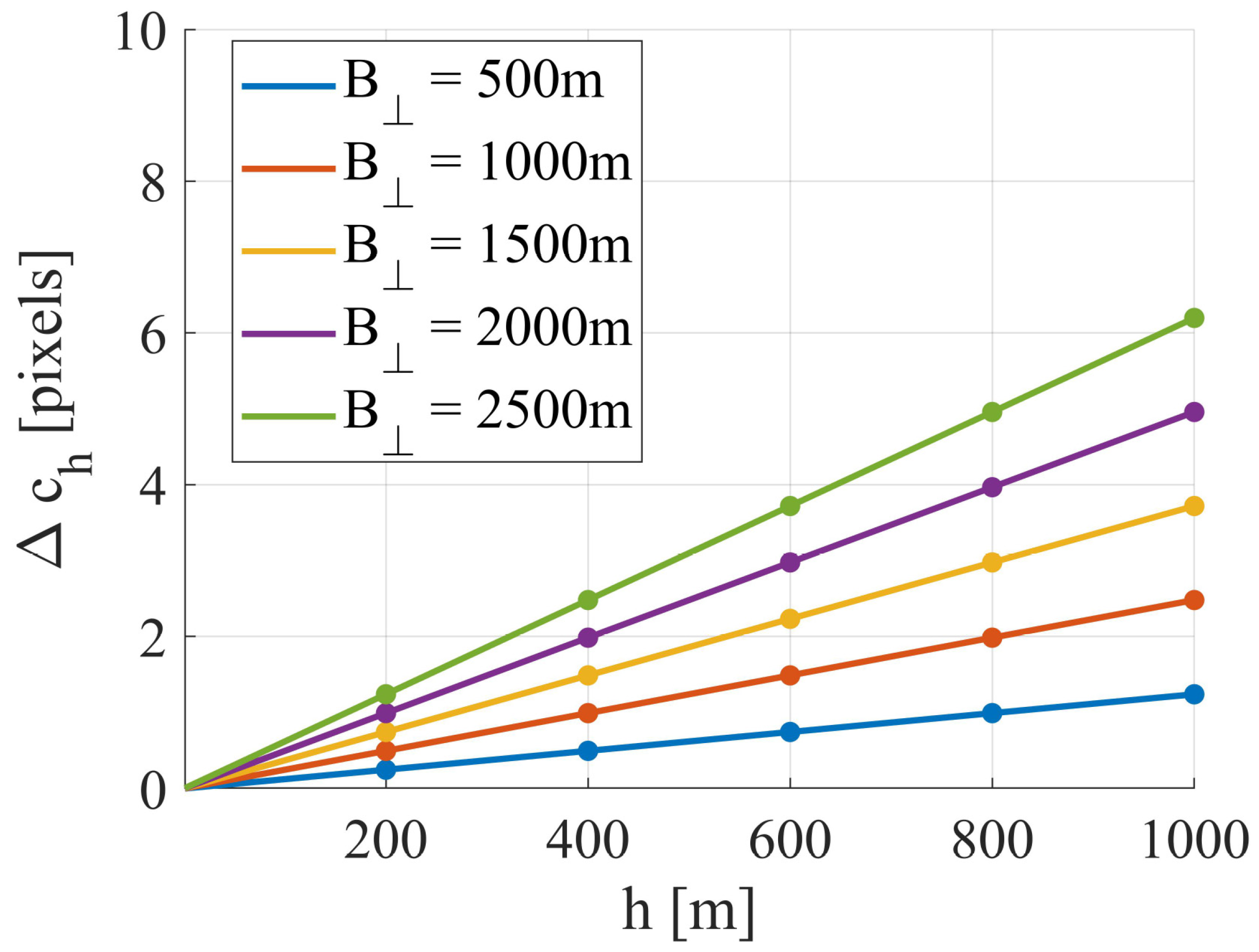

3.1. Enhanced SAR Images Co-Registration Model

3.2. Parameter Determination

3.3. InSAR DEM Generation Based on the New Method

4. Study Areas and Datasets

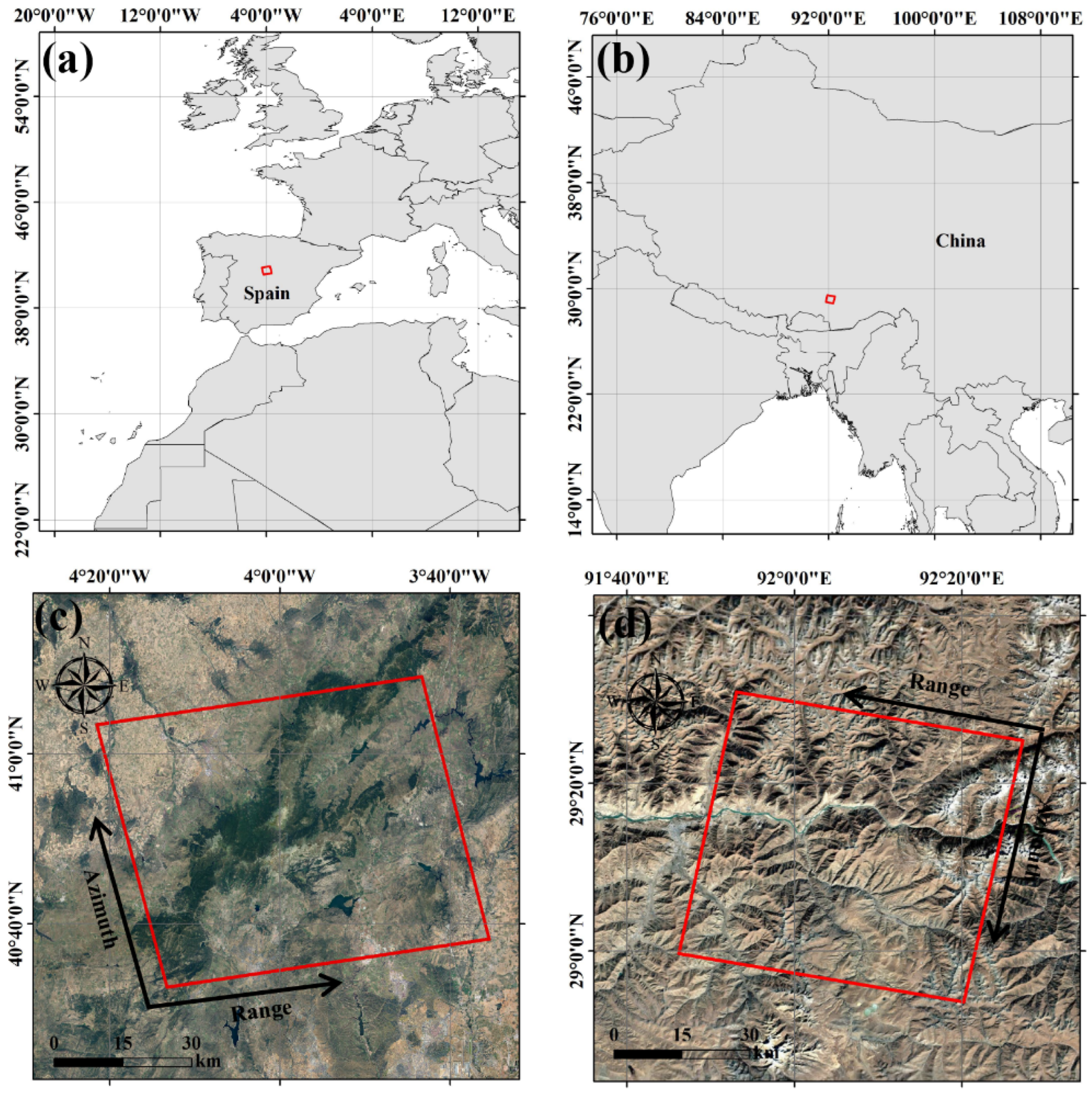

4.1. Study Area

4.2. SAR Data

4.3. Reference DEM

5. Results

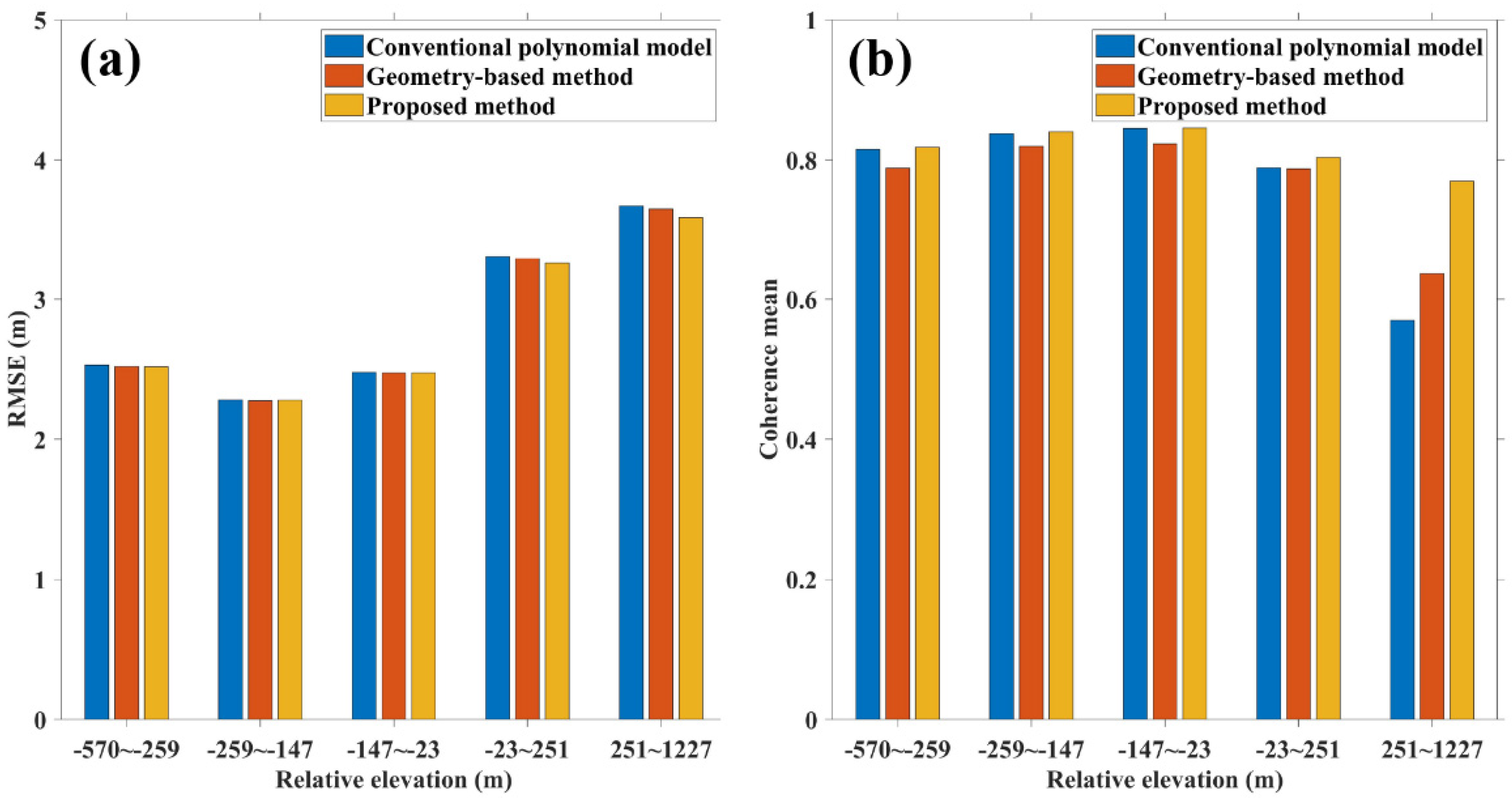

5.1. Madrid Test Site

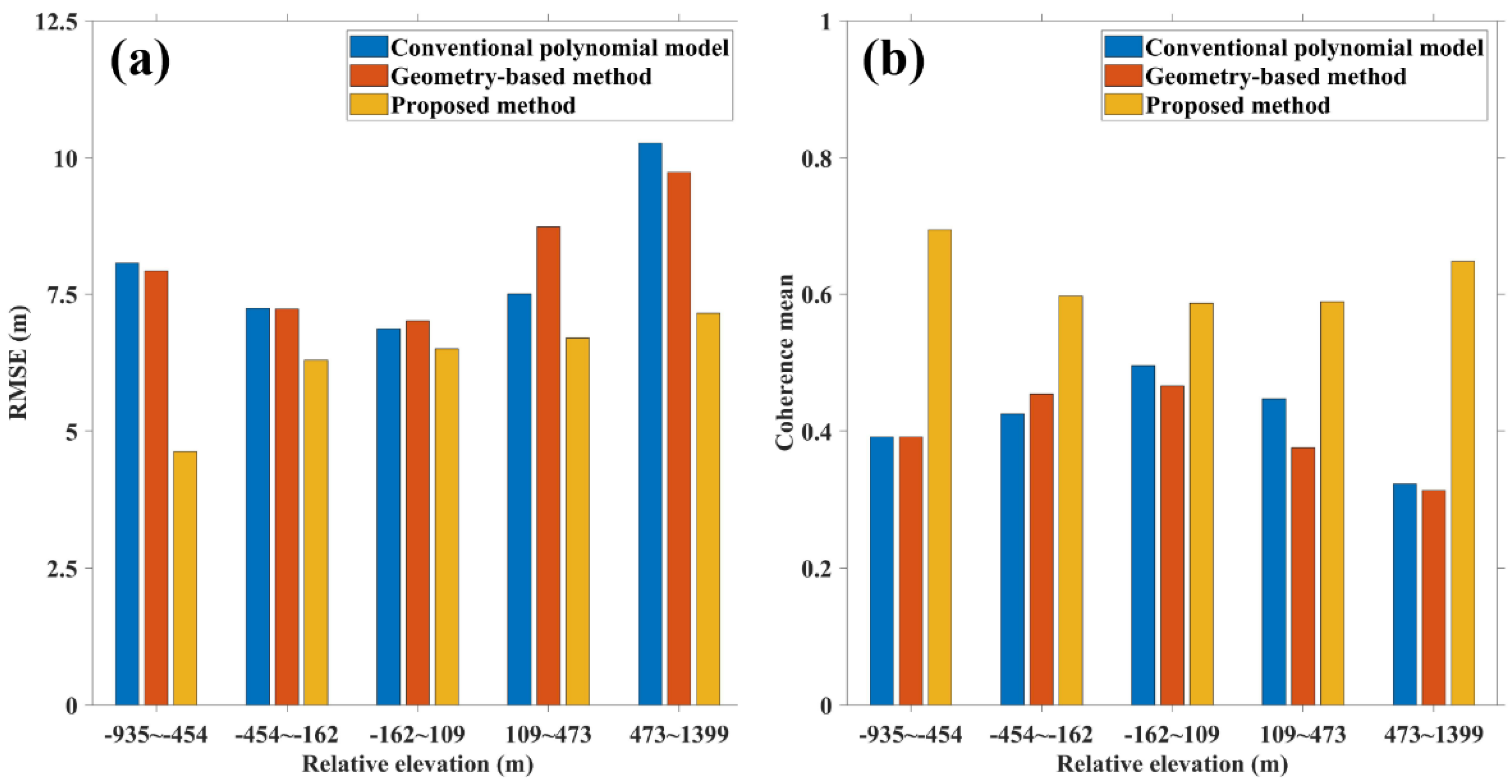

5.2. Shannan Test Site

6. Discussion

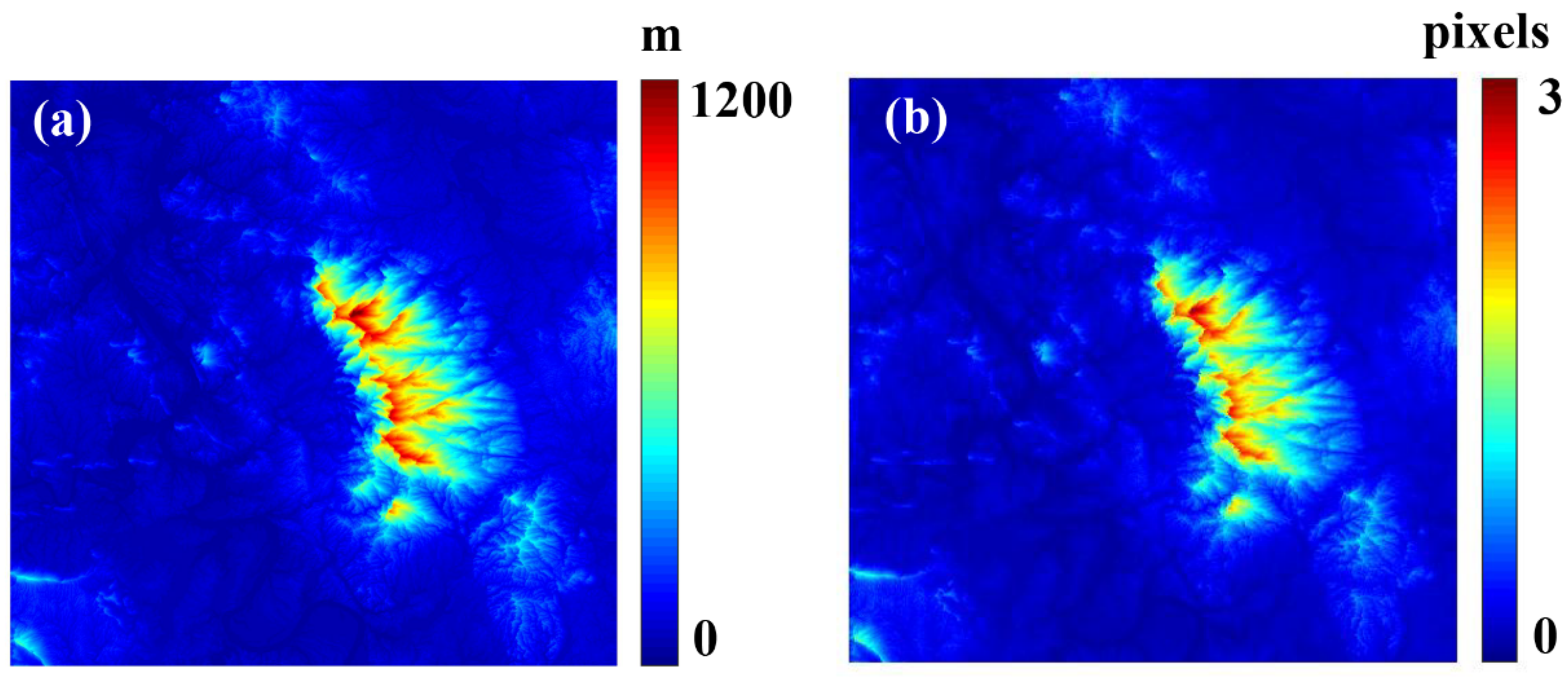

6.1. Topographic Influence Mechanisms in SAR Fine Co-Registration

6.2. Impact of External DEM on the Proposed Method

6.3. Effects of Different Terrain Conditions on InSAR DEM Generation

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mustieles-Perez, V.; Kim, S.; Krieger, G.; Villano, M. New Insights Into Wideband Synthetic Aperture Radar Interferometry. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, P.; Haener, D.; Frey, O. Detection of Railway Track Anomalies Using Interferometric Time Series of TerraSAR-X Satellite Radar Data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 11750–11760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.; Wang, J.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Jia, X.; Deng, Y. Dual-Frequency Four-Stage Polarimetric SAR Interferometry for Forest Height Estimation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, F.; Shreve, T.; Borgstrom, S.; León-Ibáñez, P.; Castillo, J.; Poland, M. A Global Assessment of SAOCOM-1 L-Band Stripmap Data for InSAR Characterization of Volcanic, Tectonic, Cryospheric, and Anthropogenic Deformation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y. A Hierarchical Feature Fusion and Attention Network for Automatic Ship Detection From SAR Images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 13981–13994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Sandwell, D.T.; Tymofyeyeva, E.; González-Ortega, A.; Tong, X. Tectonic and Anthropogenic Deformation at the Cerro Prieto Geothermal Step-Over Revealed by Sentinel-1A InSAR. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 5284–5292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcantarilla, P.F.; Bartoli, A.; Davison, A.J. KAZE Features. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2012: 12th European Conference on Computer Vision, Florence, Italy, 7–13 October 2012; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 214–227. [Google Scholar]

- Bay, H.; Ess, A.; Tuytelaars, T.; Van Gool, L. Speeded-up Robust Features (SURF). Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2008, 110, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwind, P.; Suri, S.; Reinartz, P.; Siebert, A. Applicability of the SIFT Operator to Geometric SAR Image Registration. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2010, 31, 1959–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellinger, F.; Delon, J.; Gousseau, Y.; Michel, J.; Tupin, F. SAR-SIFT: A SIFT-like Algorithm for SAR Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2014, 53, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manduchi, R.; Mian, G.A. Accuracy Analysis for Correlation-Based Image Registration Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 1993 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems, Chicago, IL, USA, 3–6 May 1993; Volume 1, pp. 834–837. [Google Scholar]

- Maes, F.; Collignon, A.; Vandermeulen, D.; Marchal, G.; Suetens, P. Multimodality Image Registration by Maximization of Mutual Information. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 1997, 16, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, J.; Longstaff, I. Minimising the Tie Patch Window Size for SAR Image Co-Registration. Electron. Lett. 2003, 39, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, J. InSAR Image Registration Using Modified Correlation Coefficient Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2006 7th International Symposium on Antennas, Propagation & EM Theory, Guilin, China, 26–29 October 2006; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Zhang, Y. A Fast Offset Estimation Approach for InSAR Image Subpixel Registration. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2012, 9, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallotta, L.; Giunta, G.; Clemente, C. Subpixel SAR Image Registration Through Parabolic Interpolation of the 2-D Cross Correlation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 4132–4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegmuller, U.; Werner, C.; Strozzi, T. SAR Interferometric and Differential Interferometric Processing Chain. In Proceedings of the IGARSS ’98. Sensing and Managing the Environment. 1998 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing. Symposium Proceedings. (Cat. No.98CH36174), Seattle, WA, USA, 6–10 July 1998; Volume 2, pp. 1106–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Simonetto, E.; Follin, J.-M. An Overview on Interferometric SAR Software and a Comparison Between DORIS and SARSCAPE Packages. In Geospatial Free and Open Source Software in the 21st Century; Bocher, E., Neteler, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 107–122. ISBN 978-3-642-10595-1. [Google Scholar]

- Reigber, A.; Hellwich, O. RAT (Radar Tools): A Free SAR Image Analysis Software Package. In Proceedings of the EUSAR, Ulm, Germany, 25–27 May 2004; Volume 4, pp. 997–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Nitti, D.O.; Hanssen, R.F.; Refice, A.; Bovenga, F.; Nutricato, R. Impact of DEM-Assisted Coregistration on High-Resolution SAR Interferometry. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2011, 49, 1127–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Hanssen, R.; Kianicka, J.; Marinkovic, P.; Van Leijen, F.; Ketelaar, G. Sensitivity of Topography on InSAR Data Coregistration. In Proceedings of the ENVISAT & ERS Symposium, Salzburg, Austria, 6–10 September 2004; pp. 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- She, J.; Tan, Y. Research on Runge Phenomenon. Comput. Math. Biophys. 2019, 8, 1500–1510. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Li, Z.; Wu, J. A Large Width SAR Image Registration Method Based on the Compelex Correlation Function. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Beijing, China, 10–15 July 2016; pp. 6476–6479. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhong, L.; Wang, J. Generation of Pixel-Level SAR Image Time Series Using a Locally Adaptive Matching Technique. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2014, 80, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, J.; Wang, Y.; Hong, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, A.; Sun, S.; Liu, G. First Assessment of Bistatic Geometric Calibration and Geolocation Accuracy of Innovative Spaceborne Synthetic Aperture Radar LuTan-1. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansosti, E.; Berardino, P.; Manunta, M.; Serafino, F.; Fornaro, G. Geometrical SAR Image Registration. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2006, 44, 2861–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, R.; Avouac, J.-P.; Taboury, J. Measuring near Field Coseismic Displacements from SAR Images: Application to the Landers Earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1999, 26, 3017–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhu, J.; Fu, H.; Feng, G.; Wang, C. Modeling and Robust Estimation for the Residual Motion Error in Airborne SAR Interferometry. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 16, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Ke, C.-Q.; Zhou, X.; Shen, X.; Yu, X.; Lhakpa, D. Glacier Mass-Balance Estimates over High Mountain Asia from 2000 to 2021 Based on ICESat-2 and NASADEM. J. Glaciol. 2023, 69, 500–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippen, R.; Buckley, S.; Agram, P.; Belz, E.; Gurrola, E.; Hensley, S.; Kobrick, M.; Lavalle, M.; Martin, J.; Neumann, M.; et al. NASADEM Global Elevation Model: Methods and Progress. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2016, 41, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yao, T.; Zhang, G.; Li, F.; Zheng, G.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, F. Towards Ice Thickness Inversion: An Evaluation of Global DEMs by ICESat-2 in the Glacierized Tibetan Plateau. Cryosphere Discuss. 2021, 16, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolie, C.J.; Mills, J.P.; Adeleke, A.K.; Smit, J.L.; Peppa, M.V.; Altunel, A.O.; Arungwa, I.D. Assessment of the Global Copernicus, NASADEM, ASTER and AW3D Digital Elevation Models in Central and Southern Africa. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 27, 1362–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, M.H.; Malz, P.; Sommer, C.; Farías-Barahona, D.; Sauter, T.; Casassa, G.; Soruco, A.; Skvarca, P.; Seehaus, T.C. Constraining Glacier Elevation and Mass Changes in South America. Nat. Clim. Change 2019, 9, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, M.; Jones, S.; Reinke, K. Vertical Accuracy Assessment of Freely Available Global DEMs (FABDEM, Copernicus DEM, NASADEM, AW3D30 and SRTM) in Flood-Prone Environments. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2024, 17, 2308734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Datasets | Range Pixel Spacing (m) | Look Angle (°) | Slant Range (m) | Critical Perpendicular Baseline (m) | Wavelength (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LT-1 | 1.66 | 21.7 | 656,967 | 18,759 | 23.81 |

| Study Area | Sensor | Acquisitions Date | Radar Look Angle (°) | Pixel Spacing (Range/Azimuth) (m) | Effective Baseline (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madrid, Spain | LT-1A | 23 October 2022 | 26.31 | 1.67/2.13 | −1352 |

| LT-1B | 26.11 | ||||

| Shannan, China | LT-1A | 26 October 2022 | 25.43 | 1.67/2.10 | −2489 |

| LT-1B | 25.59 |

| Conventional Polynomial Model | Geometry-Based Method | Proposed Method | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madrid test site | Mean | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.79 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.16 | |

| Pixel ratio with coherence less than 0.3 (%) | 5.30 | 4.70 | 4.20 | |

| Shannan test site | Mean | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.48 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.25 | |

| Pixel ratio with coherence less than 0.3 (%) | 52.9 | 56.1 | 31.2 |

| Conventional Polynomial Model | Geometry-Based Method | Proposed Method | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madrid test site | Mean (m) | 0.04 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| RMSE (m) | 2.92 | 2.89 | 2.87 | |

| Shannan test site | Mean (m) | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.15 |

| RMSE (m) | 8.12 | 8.23 | 6.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeng, D.; Fu, H.; Zhu, J.; Han, Q.; Wang, A.; Zhang, M.; Wu, K.; Liu, Z.; Li, Z. Enhanced Co-Registration Method for Long-Baseline SAR Images. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 4034. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244034

Zeng D, Fu H, Zhu J, Han Q, Wang A, Zhang M, Wu K, Liu Z, Li Z. Enhanced Co-Registration Method for Long-Baseline SAR Images. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):4034. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244034

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Dong, Haiqiang Fu, Jianjun Zhu, Qijin Han, Aichun Wang, Mingxia Zhang, Kefu Wu, Zhiwei Liu, and Zhiwei Li. 2025. "Enhanced Co-Registration Method for Long-Baseline SAR Images" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 4034. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244034

APA StyleZeng, D., Fu, H., Zhu, J., Han, Q., Wang, A., Zhang, M., Wu, K., Liu, Z., & Li, Z. (2025). Enhanced Co-Registration Method for Long-Baseline SAR Images. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 4034. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244034