Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Summarizes and analyzes the advantages and limitations of various soil moisture monitoring techniques.

- Compiles and evaluates existing soil moisture datasets, highlighting their respective strengths and weaknesses.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Provides a systematic and comprehensive structural summary of soil moisture monitoring methods.

- Conducts a trend analysis of the development of major monitoring methods and soil moisture datasets.

Abstract

Soil moisture (SM) is a key variable regulating land–atmosphere energy exchange, hydrological processes, and ecosystem functioning. Though important, there are still unresolved problems in accurate SM monitoring and the practical application and validation of existing methods. In this review, we integrate mechanistic classification and applicability and constraint discussions to develop a coherent understanding of current SM monitoring approaches. Within this framework, in situ measurements, optical and thermal infrared methods, active and passive microwave remote sensing (RS) techniques, and model-based simulations are compared, and publicly accessible SM dataset products are comparatively analyzed in terms of product characteristics and application limitations. Different from other published reviews, this study covers a large scope of SM monitoring methods varying from in situ observation to RS inversion, and classifies them based on their mechanisms, thereby constructing a complete comparative framework for SM research. Moreover, three types of open-access SM dataset products are investigated, optical and microwave RS products, model simulation and data fusion products, and reanalysis dataset products, and evaluated according to their resolution, depth, applicability, advantages, and limitations. By doing so, it is concluded that in situ observations remain essential for calibration and validation but are spatially limited. Optical and thermal infrared methods are restricted by atmospheric conditions and a shallow penetration depth, while microwave techniques exhibit varying performances under different vegetation and soil conditions. Existing datasets differ significantly in resolution, consistency, and coverage, making no single product universally applicable. Future research should focus on multi-source and spatiotemporal data fusions, the integration of machine learning with physical mechanisms, enhancement for cross-sensor consistency, the establishment of standardized uncertainty evaluation frameworks, and the refinement of high-order RTMs and parameterization.

1. Introduction

Soil moisture (SM) is a fundamental component of the terrestrial water cycle, influencing global climate regulation, agricultural productivity, water management, and ecosystem stability [1]. It mediates land–atmosphere exchanges of water and energy, thereby affecting plant growth [2], evapotranspiration, and surface runoff [3]. Consequently, SM data are widely applied in climate change research [4], drought monitoring, irrigation scheduling [5], water resource management [6], flood forecasting [7], and ecological assessments. SM variability is controlled by factors such as surface cover, vapor transport, and temperature, which jointly determine soil infiltration, groundwater recharge, and runoff generation. Accurate and real-time SM monitoring is therefore crucial for understanding climate change impacts, wetland conservation [8], efficient irrigation management [2], disaster prediction [9], and sustainable water use. Moreover, it provides essential data support for hydrological and climatic studies [10,11], ecosystem health evaluation [12], environmental protection, and agricultural development [13,14]. Its accurate monitoring is vital for sustainable agriculture, optimized water use, and studies of climate–ecological processes.

In recent years, SM research has advanced significantly with the development of in situ observation and remote sensing (RS) technologies. In situ methods provide high-precision measurements at small scales [9] but are limited by instrument operability, portability, and cost [15]. RS enables large-scale, multi-temporal inversion, but its accuracy is affected by sensor type, observation conditions, and calibration. Optical techniques offer high spatial resolutions [8] but are sensitive to atmospheric, evapotranspiration (ET), vegetation, and soil conditions [16], whereas microwave techniques are more robust and can penetrate soil but have limited spatial resolutions and are influenced by soil roughness [17]. Multi-source data fusion has emerged to integrate the strengths of different approaches, improving accuracy, spatial coverage, and temporal continuity [18,19]. However, data complexity and environmental variability can limit regional performance. Future research should focus on high-precision, high-resolution inversion, efficient data assimilation and fusion algorithms, predictive and adaptive models [13,20], and novel sensors to enhance accuracy. By combining RS, ground measurements, and data analysis, a comprehensive understanding of SM spatiotemporal dynamics can be achieved, providing critical support for global-scale research and sustainable development.

At the same time, numerous reviews have been conducted, such as some focusing on specific techniques such as the GNSS method [21,22], machine learning models [23,24], or physical mechanisms of active and passive microwave inversion [25], or others diving into certain applications [26]. They generally lack a comprehensive coverage of SM monitoring methods and fail to provide a clear and systematic classification framework. While other reviews touch upon various techniques [27], they primarily emphasize explanation and comparison between features of different SM monitoring methods, omitting reviewing dataset products to guide practical application. In view of these considerations, this paper aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic synthesis of SM monitoring methods, indices, and models, and provides a critical analysis of their respective advantages and disadvantages in practical applications of recent research trends. In order to achieve these goals, all reviewed methods are categorized into in situ observations, optical RS, thermodynamic and energy balance approaches, and microwave RS, and each category is thoroughly compared and summarized. In addition, a comparison of different public soil moisture datasets is also made, thereby providing a more practical and unified perspective for the research community.

This survey is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a detailed overview of in situ soil moisture observation techniques. RS-based inversion approaches and their underlying principles are explicated in Section 3. Section 4 reviews the characteristics and distinctive features of publicly available datasets generated from active and passive RS observations in combination with reanalysis products. Building upon these foundations, in Section 5, we discuss methodological advances from the perspective of different categories of approaches, with an emphasis on their future directions and applicability.

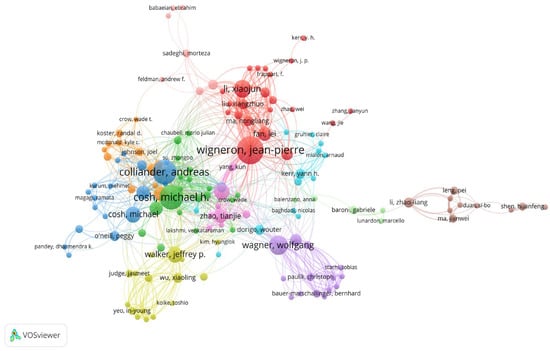

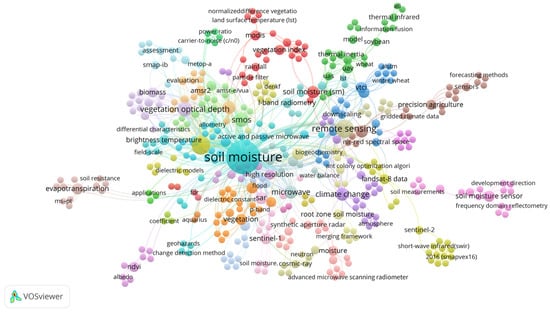

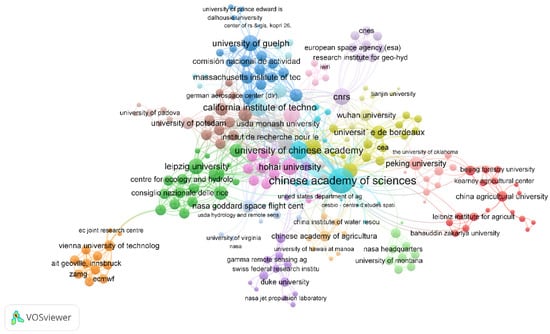

Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrate the keywords, author affiliations, and author citation relationships from the referenced literature in this paper, providing a helpful guide to analyze the research outcomes of different institutions and authors.

Figure 1.

Author co-citation network map cited by this article.

Figure 2.

Keyword co-occurrence network map cited by this article.

Figure 3.

Author–institution collaboration network map cited by this article.

2. In Situ Observation-Based Soil Moisture Monitoring Methods

Soil moisture (SM) monitoring methods based on in situ observation can be categorized into invasive and non-invasive techniques. The choice of method during measurement is often influenced by various factors, including the environment, user expertise, the cost of usage and maintenance, operational complexity, portability, offline availability, and environmental impact [15].

2.1. Invasive Detection Technologies

Invasive detection technologies refer to methods where sensors or probes are directly inserted into the soil for moisture measurement. The traditional gravimetric method is based on the weight difference in soil samples under constant temperature and humidity conditions to calculate SM. However, this method is destructive to the observation site, is significantly dependent on environmental conditions, and is time-consuming [28]. Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR) and Frequency Domain Reflectometry (FDR) determine SM by measuring the propagation period or phase shift in electromagnetic waves, but they require specific calibration with high-cost and complex operation [27,29]. The dielectric constant is also commonly used in SM monitoring, but it is usually affected by soil texture, structure, organic matter content, salinity, and moisture [30]. Capacitance and Impedance Dielectric Reflectometry (CIDR) uses the dielectric constant to analyze the complex impedance of the soil, separating the real and imaginary components of the dielectric constant to distinguish the energy storage and loss of electromagnetic waves, which helps to differentiate salinity, temperature, spatial variability, and moisture between the sensor and soil. Furthermore, it introduces numerical solutions of Maxwell’s equations to improve accuracy [31,32]. However, the accuracy of this method decreases with high-moisture soil and needs calibration to address the nonlinearity between voltage and moisture.

2.2. Non-Invasive Detection Technologies

Non-invasive technologies do not directly touch the soil or cause damage. Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) in the L-band can sensitively detect changes in SM. Although these methods offer a high precision and tolerance to surface cover and soil roughness, their accuracy is susceptible to radio-frequency interference (RFI) from the surroundings. So, scholars have proposed a dual-antenna design and a method based on the chirp ratio to measure SM by utilizing phase shifts in LoRa signals, effectively reducing signal interference and improving measurement accuracy [29]. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) measures SM by detecting atomic resonance in a magnetic field. This method is highly accurate but requires expensive equipment, is hard to operate, and has high demands for the magnetic field [33]. A Cosmic Ray Neutron Probe (CRNS) infers SM by measuring the number of slow neutrons generated from collisions between fast neutrons and hydrogen atoms in the soil. The number of slow neutrons is proportional to the SM [33]. The novel CRNS-FINAPP detector, based on scintillators, offers a high sensitivity and is suitable for large-scale SM monitoring. However, it faces challenges such as high operation costs, radiation exposure, and a limited observation range [34]. The applicability of in situ observation-based monitoring methods varies significantly across different situations. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics and applicability of current in situ observation methods.

Table 1.

Comparison of advantages and limitations of in situ soil moisture monitoring techniques.

2.3. Key SM Field Experiments and the Global Role of the ISMN

In recent years, major international SM field experiments have provided essential datasets that support algorithm development, product validation, and improvements in the global applicability of passive and active microwave RS. The CanEx-SM10 field experiment established a high-resolution ground–airborne L-band observation benchmark that enabled the pre-launch validation of SMOS/SMAP products, providing essential datasets for the calibration and parameter optimization of SM retrieval algorithms [45,46]. SMAPVEX12 and SMAPVEX16 further contributed through coordinated airborne L-band radiometry and a temporary SM network, offering robust references for SMAP algorithm calibration and accuracy assessment [47,48]. Similarly, the SMAPEx provided dense multi-season observations that have been critical for evaluating SMAP performance in arid and semi-arid regions [49].

Regional programs have also played an important role. THEXMEXs generated systematic datasets on SM heterogeneity in drylands, supporting microwave model evaluation for complex surfaces [50]. The MicroWEXs, through plot-scale networks and surface flux observations, advanced the understanding of microwave brightness temperature–SM relationships and scale transition modeling [47]. The AMMA project established a multi-scale SM observations system widely used for evaluating satellite product stability and studying land–atmosphere feedback [51,52].

In addition, the International Soil Moisture Network (ISMN) provides standardized, quality-controlled global in situ SM records, serving as a consistent foundation for satellite validation, model calibration, and uncertainty assessment [53,54]. Its continuous expansion greatly enhances the global verifiability and cross-regional applicability of satellite SM products.

The establishment of a comprehensive and well-organized ground-based SM observation network has fundamentally improved the previously fragmented validation practices of satellite SM products. As demonstrated by the work of Gruber et al., the network enables a complete and standardized validation workflow—from data selection and preprocessing to uncertainty quantification—effectively resolving the long-standing issue of non-comparable evaluation results caused by the heterogeneity of traditional reference datasets [55].

3. Remote Sensing-Based Soil Moisture Inversion Methods

Remote sensing (RS) inversion offers significant advantages for large-scale ground exploration, with the ability to provide coherent information across spatial and temporal scales. Therefore, RS-based observation methods have been widely applied to soil moisture (SM) inversion.

3.1. Optical RS-Based Estimation Methods

Optical RS technology operating in the visible light spectrum (0.3–0.76 µm) provides a preliminary analysis of the physics of the soil surface and vegetation cover by capturing reflections from the surface of vegetation, soil, and others across different wavelengths, which is highly sensitive to water movement and can indirectly offer valuable information for SM inversion. Within the infrared wavelength range (0.76–100 µm), the thermal radiation properties of soil and vegetation serve as key indicators, and variations in SM significantly affect the thermal inertia and thermal–hydrological balance, thereby altering the soil surface temperature distribution. Consequently, these temperature differences can be precisely detected by infrared RS to effectively invert SM dynamics [11]. The fusion of visible and infrared RS technologies provides a more stable observation approach for accurate and efficient SM inversion compared with using a single RS method [56,57].

3.1.1. RS Index Method

The RS index, as a key parameter for surface conditions, is a sensitive indicator of humidity-related information for the land surface and atmosphere. However, the index method is primarily limited by its shallow sensing depth and is susceptible to interference from spatiotemporal relationships, spatial heterogeneity, surface biological properties, and evapotranspiration (ET) [58,59], making it difficult to effectively invert dynamic changes in the vertical soil profile. By using the Soil Water Index (SWI) [60], the spatiotemporal variation characteristics of SM can be incorporated into a two-layer water balance model to consider moisture at different layers, avoiding interference and more fully accounting for the moisture balance and natural water storage changes in soil. Therefore, it improves the accuracy and spatial resolution of SM inversion [58,61]. The water balance relationship under the two-layer model performs well in inversing SM and soil aridity, but it heavily relies on prior data, environmental parameters, and the algorithms employed [62]. Thus, it is not suitable for regions where environmental parameters are hard to obtain or where there is no support from in situ measurements. Moreover, this method may overestimate drought severity in arid areas [63]. The complexity of surface vegetation also influences the inversion results. The Vegetation Temperature Condition Index (VTCI) and SWI focus on surface covering, since vegetation has a clear response to water volume inside roots. Therefore, the relationship between vegetation and land surface temperature (LST) can effectively reveal the SM result [64,65]. However, this method is easily influenced by the vegetation density [66], and spectral reflections of vegetation can be easily interfered with by atmospheric status, the scale and type of observation, and vegetation growth [67,68]. Carlson et al. constructed a feature space for pixels using the vegetation index (VI) and LST by treating the geometric distribution of pixels as the boundary. Known as the triangular method, this approach does not require detailed atmospheric status or prior soil data and reduces the need for atmospheric calibration by scaling the observation variables [69,70]. However, the dry–wet boundary is highly influenced by atmospheric forcing and unreal dry–wet points, inaccurate dry–wet boundaries, and incorrect ET estimation exist in large-scale space [71]. This method cannot accurately capture deep SM and vegetation water volume. For the trapezoidal method, an improvement over the triangular method, the subjective determination of pixel windows, and the assumption of similar atmospheric conditions for a comparison of each pixel’s spatial distribution are required [72]. Moreover, LST is influenced not only by SM but also by environmental atmospheric conditions, making the triangle and trapezoidal methods difficult to apply across different regions and times since they significantly rely on empirical or semi-empirical models [73]. Inge Sandholt and colleagues proposed a simpler Temperature Vegetation Drought Index (TVDI) based on Carlson’s research [74]. This method does not require meteorological or ground observation data. Instead, it parametrizes the relationship between the temperature of the surface (Ts) and the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) to perform inversion, providing more detailed vegetation and moisture information [75]. However, it is suitable for low vegetation coverage areas (vegetation coverage < 35%), which should not be too low, as insufficient vegetation coverage can lead to inaccurate identification for drought, and should not be too high, since too much vegetation covering reduces NDVI sensitivity and causes large deviations. This method is also sensitive to the directional anisotropy of LST, which can cause inconsistencies in results at different observation angles [76]. The temporal error in LST and NDVI can affect the extraction of the dry–wet boundary, leading to inversion errors [77]. Additionally, precipitation and ET are closely related to hydrological processes. Incorporating ET into the index calculation can improve the accuracy of SM evaluation [78]. The modified perpendicular drought index (MPDI) reflects SM variations, playing a significant role in assessing the spatiotemporal distribution of drought under global climate change [79], monitoring spatial heterogeneity of drought in agricultural areas, constructing global drought index datasets [80,81], and monitoring global warming and wetting trends [79]. There are numerous methods for inversing SM using RS indices. The examples mentioned above focus on spatial complexity, biological influences, and ET. More methods are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of soil moisture inversion methods and functions based on remote sensing indices in published order. Strong correlation: can be directly used for quantitative inversion of soil moisture; weak correlation: indirect inversion of soil moisture through vegetation status.

3.1.2. Thermodynamic and Energy Balance Methods

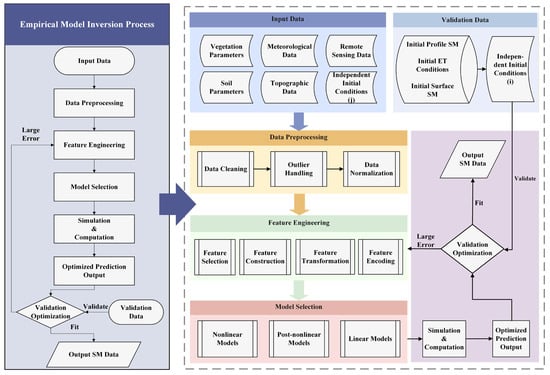

Changes in the thermodynamic state of soil are the key indicators for the movement of moisture. The thermodynamic characteristics of soil, such as thermal capacity and thermal conductivity, are significantly influenced by SM and changes in thermal properties, caused by thermodynamic variations, which directly reflect SM. By building empirical or semi-empirical models to describe a relationship between thermodynamic variables and SM, it is possible to invert the changes in SM under more complex scenarios. The general process for this SM inversion is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

SM inversion process based on empirical and semi-empirical models.

Among thermodynamic approaches, thermal–infrared RS (TIR)-based inversion remains one of the most widely used and physically interpretable methods. By combining LST with VI, texture indices, and thermal infrared vegetation indices, TIR-based approaches capture the sensitivity of surface temperature to SM, particularly in sparsely vegetated regions where the thermal signal is strongly controlled by soil evaporation [92]. Recent work has further shown that red-edge and short-wave infrared bands from Sentinel-2 improve SM retrieval in mixed vegetation–soil pixels, extending their applicability to more heterogeneous conditions [93]. For complex terrain, topographic correction using MODIS LST products has been shown to reduce the retrieval biases caused by temperature discontinuities [70].

A second major category is the thermal inertia (TI) method, which exploits the dampening effect of SM on diurnal temperature variations. The classical TI framework [92] has been simplified through the apparent thermal inertia (ATI) formulation [94], and subsequently improved by incorporating soil porosity and simulating multiple soil textures [95,96]. These advances reduce parameter uncertainty and enhance applicability across varying soil structures and vegetation cover. High-resolution multispectral and thermal infrared data from UAV platforms further refine thermal property estimation and significantly enhance SM inversion accuracy in heterogeneous landscapes [97]. Although TI-based approaches remain computationally intensive, they are among the most thermodynamically consistent methods for retrieving SM at diurnal to seasonal scales.

In addition, surface energy balance-based SM estimation provides a physically grounded and generalizable framework. Rather than relying on full evapotranspiration (ET) modeling, recent SM-oriented applications focus on the relationship between LST, VIs, and the partitioning of available energy, enabling the identification of dry and wet endmembers and deriving SM through normalized evaporative indices [98]. This family of methods builds on the premise that SM strongly regulates the ratio of sensible to latent heat fluxes, and recent studies have demonstrated an improved performance when incorporating high-resolution LST, vapor pressure deficit, and land–surface coupling metrics [99]. These developments significantly enhance the robustness of energy balance-based SM estimation while avoiding the limitations of ET-focused models such as SEBAL or the Penman–Monteith equation, whose detailed parameterization is not primarily designed for SM retrieval.

Collectively, these thermodynamic and energy balance approaches provide an important complementary pathway to microwave-based SM inversion. Their strengths include high responsiveness to surface evaporative conditions, strong physical interpretability, and the ability to leverage optical, thermal, and UAV data sources for improving spatial detail and extending applicability across diverse land surface conditions [100].

3.2. Active and Passive Microwave Radiation and Radiation Transfer Modeling-Based Methods

Changes in SM lead to fluctuations in dielectric constants, causing significant differences in the propagation characteristics of microwave signals in the soil layer (phase and polarization). By investigating the changes in these signals, SM can be inverted. The microwave method relies primarily on the dielectric properties of soil, which are strongly influenced by SM. Microwave inversion can be categorized into passive microwave RS and active microwave RS. Commonly used frequency bands include P-band (0.3–1 GHz), L-band (1–2 GHz), C-band (4–8 GHz), X-band (8–12 GHz), Ku-band (12–18 GHz), and Ka-band (26.5–40 GHz). Different bands have respective advantages towards SM, soil texture (sand or clay), soil salinity, and the ability to penetrate vegetation cover [101]. In practical applications, the X-, Ku-, and Ka-bands are generally unsuitable for SM retrieval. These higher-frequency signals are strongly attenuated by vegetation canopies and have limited penetration depths compared with the L-band [102]. They are also more sensitive to surface roughness, causing scattering contributions to dominate and thereby suppressing inversion sensitivity [103,104]. Studies further show that X-band SAR performs poorly in densely vegetated areas [105], and earlier analyses indicate that Ku- and Ka-band responses to soil parameters are weak, with variations driven mainly by surface scattering and vegetation rather than SM [106,107,108].

In contrast, P-, L-, and C-band microwaves provide more favorable characteristics for SM inversion. The P-band penetrates surface roughness and sparse vegetation and is sensitive to deeper soil dielectric variations, with minimal roughness or vegetation interference [109]. The L-band offers the best balance between soil dielectric sensitivity and vegetation penetration, which is why it is adopted by major missions such as SMOS, SMAP, and ALOS-PALSAR [110,111,112]. The C-band retains useful sensitivity to surface moisture, especially in sparsely vegetated regions, and its high revisit frequency is valuable for trend analysis and data assimilation [112].

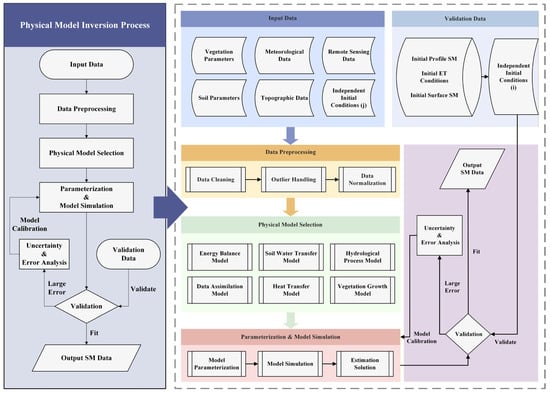

The direct connection between microwave signals and SM inversion or the relationship between the radiation signal and the physical processes can be utilized, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

SM inversion process based on physical models.

3.2.1. Active and Passive Microwave Radiation-Based Method

Active microwave radiation imaging has a high spatial resolution and thus is extremely sensitive to surface structure, but its temporal resolution is low. The image processing is complex and is susceptible to the influence of surface roughness. In contrast, passive microwave radiation has a higher temporal resolution, but a lower spatial resolution, since the passive method receives radiation from the surface, which is sensitive to surface moisture and can obtain deeper SM information, but is also sensitive to surface structure.

- (a)

- Active Microwave Radiation RS-Based Methods

Sentinel-1, equipped with C-band active microwave radar, has a wide spatial coverage, is effective in harsh weather conditions, and performs well in areas with vegetation coverage. SAOCOM’s L-band, on the other hand, is more sensitive to SM and can effectively avoid the impact of surface structure on the signal. Rana et al. combined the data from both satellites to effectively reduce the impact of soil surface roughness and atmospheric interference on the data [113]. Xing et al. proposed a method to calibrate soil and vegetation parameters using the Water Cloud Model (WCM) and the Ulaby soil model. By integrating Sentinel-1 data with a random forest (RF) algorithm, they achieved high-spatial-resolution inversion of SM and generated a 1 km resolution product (SMS-1), which helps address the accuracy issues caused by a complex vegetation canopy structure [114]. Fan et al. used the τ-ω two-layer radiation transfer model with dual-polarization (VV and VH) to obtain brightness temperature observation data, creating a microwave polarization difference index to calculate SM and vegetation optical depth (VOD). Polarization observation data can capture more detailed surface features and canopy information, reducing the reliance on auxiliary parameters like surface temperature and improving SM inversion accuracy while providing higher spatial resolution products [115]. Combining C-band SAR data with optical data can effectively reduce the impact of vegetation and enhance the temporal and spatial accuracy of inversion data. Wu et al. combined Landsat 8 optical data with SAR data and applied RF models along with optimization algorithms such as Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) and Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA). By constructing ACO-RF and SSA-RF hybrid models, they addressed the problem of a low spatial resolution and insufficient observation depth in single data source inversions, improving SM inversion accuracy at different depths (0–40 cm) [116]. Optical data can help to optimize empirical or semi-empirical model parameters, thus reducing the impact of vegetation moisture content (VMC) on microwave signal attenuation. Additionally, based on GF-1/3 data, multi-model coupling and background knowledge coupling strategies were used to develop a combined VI model to estimate VWC, enabling high-precision SM inversion in complex surface areas [117]. To better utilize SAR time series data to improve inversion accuracy, a new dual-station radiation transfer modeling framework (RT1) has been applied to process time series data and obtain high-resolution SM information [118]. To describe the nonlinear relationship between radar scattering coefficients and SM, based on AirMOSS-P band radar data, simulated annealing optimization algorithms were proposed to significantly improve inversion accuracy [119].

- (b)

- Passive Microwave RS-Based Inversion Methods

Key parameters affecting the passive microwave RS moisture response include vegetation effective scattering albedo (ω), soil roughness, and VOD, which makes passive microwave susceptible to interference. There are many empirical or semi-empirical parameters when modeling, making the accuracy and applicability of these parameters vary across different regions and scales [120,121,122]. The uncertainty in model parameters and signal complexity directly affects the accuracy of SM inversion [123,124]. SM is often coupled with vegetation signals. To avoid the influence of multiple parameters, the single-channel algorithm (SCA) is used, which only relies on polarized brightness temperature and VWC to calculate SM, thus reducing the degree of inversion data accuracy degradation caused by multi-parameter coupling. Sharma et al. introduced VWC into the SCA calculation to enhance its application in agricultural irrigation areas, resulting in smaller deviations and stronger correlations compared with the original methods [125]. However, SCAs are based on optical VWC, which is susceptible to weather and cloud interference and is inconsistent with microwave frequencies. To overcome the dependency on vegetation parameters in SCAs, the Dual-Channel Algorithm (DCA) has been widely applied, which relies only on brightness temperature data, without needing VWC, and uses H/V polarization channels for richer information [126]. Although the DCA does not depend on vegetation parameters, its performance is relatively poor, its algorithm is complex, and its inversion for VWC still requires auxiliary data. In areas with bare soil or sparse vegetation coverage, the difference is insignificant, leading to unstable inversion [127]. Vegetation signal scattering and interannual variations in vegetation optical depth pose a challenge to the accuracy of SM inversion. The fusion of multi-angular observations with active–passive microwave data fusion is a key direction for improving inversion precision [128]. The AMSR2 IB algorithm considers factors such as vegetation coverage, soil texture, and moisture content. Since observation signals are easily influenced by soil roughness, by calibrating ω and soil roughness, it uses the τ-ω radiation transfer model for the inversion of SM and VOD [126,129]. Similarly, using the Deterministic Ensemble Kalman Filter (DEnKF) and other filters for data assimilation [130], along with different land surface data to improve soil parameter estimation, can enhance precipitation estimation and SM inversion accuracy [131].

- (c)

- Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) Reflection Methods

In recent years, the use of Global Navigation Satellite System Reflection (GNSS-R) signals for SM inversion has gained significant attention. This includes GNSS-R, GPS Interferometric Reflection Measurement (GNSS-IR), and Multi-GNSS Interferometric Reflection Measurement (Multi-GNSS) technologies [22,132]. The principle of GNSS-R, which is like the SMAP satellite, considers multipath effects, signal-to-noise ratio analysis, geometric relationships, and interference patterns. GNSS signals refract as they pass through soil, and the intensity of the signals is related to the dielectric constant of the soil, achieving SM inversion [133]. GNSS technology does not require extra transmitters and can make full use of existing satellite signals and ground receiving stations, making it low-cost. Its data processing is simple, making it easy to implement large-scale, long-term inversion. By integrating GPS, GLONASS, Galileo, and BDS multi-constellation data, GNSS technology can achieve global coverage, compensate for missing data series, and improve applicability. With advanced algorithms, GNSS technology can process data in real time, offering a high temporal resolution and the ability to capture rapid changes in SM.

3.2.2. Radiation Transfer Modeling-Based Methods

The soil dielectric constant changes with SM, which in turn affects the brightness temperature observed by microwave radiometers. SM can be inverted by establishing models between the brightness temperature and SM, which primarily have three categories: dielectric model methods, soil roughness model methods, and vegetation–surface radiation transfer process simulation methods (RTMs).

- (a)

- Dielectric Model Method

SM directly influences the dielectric constant of the soil. By applying the Fresnel reflection equation, a mathematical relationship can be established between reflectance and the dielectric constant of the surface, which can then be used to invert SM [134]. As early as 2014, several dielectric methods have been proposed to estimate SM for SMAP satellite data, such as the Mironov, Dobson, Wang_Schmugge, and Hallikainen models [135]. In 2015, Mialon et al. compared the response of various dielectric models on a global scale, finding that the Mironov model required fewer input parameters while exhibiting a higher correlation [136]. Meanwhile, in 2021, Suman et al. tested the response of mixed dielectric models in complex terrains, providing valuable insights for selecting the most suitable model in various terrain and climate conditions [137]. But other factors, such as surface roughness [138], vegetation cover, soil texture [139], soil salinity [140], and temperature, can also impact the accuracy of dielectric constant measurements. While the dielectric constant method provides the foundational physics for RTM inversion, the research focus is shifting towards the roughness of soil and vegetation water content, aiming to achieve a higher precision by mitigating the effects of interference and scale discrepancies.

- (b)

- Soil Roughness Model Method

Soil roughness is a crucial parameter influencing microwave signal interactions, and traditional models often rely on semi-empirical methods by comparing the reflection differences between bare soil and smooth surfaces [141]. However, actual soil surface conditions are more complex, and the presence of numerous nonlinear factors can make it hard for simplified linear models to represent the surface conditions. To overcome this, some researchers has proposed using the τ-ω model along with TB and in situ data to simulate soil roughness as a dynamic parameter h rather than a static constant when inversing SM [142]. Meanwhile, another team suggested combining a multi-scale roughness model to invert soil roughness and achieved a good SM validation result in SMAPVEX12 and SMAPVEX15 [143]. In 2021, Yin et al. used a scattering model and combined it with a dual-channel convolutional neural network (CNN) to build the nonlinearity between SM and roughness, allowing for the more precise inversion of SM variations [144]. A method for implementing the RF model to calibrate global soil roughness for SMOS-IC SM inversion was also published [145]. More recent research has taken a geometric perspective. By using the Integral Equation Model (IEM) with SAR data, multi-scale soil roughness estimates have been obtained, enhancing SM inversion accuracy [146]. With more studies and research into soil roughness, we can be convinced that soil roughness performs as a coupled system with SM, making it difficult to accurately invert each parameter in isolation [147]. Moreover, in densely vegetated areas, the vegetation interference further obscures their individual signatures and becomes the primary source of retrieval error [138].

- (c)

- Vegetation–Surface Radiation Transfer Process Simulation Method

Vegetation–surface RTMs are essential for microwave-based SM retrieval in vegetated landscapes because they explicitly separate soil emission from canopy scattering and attenuation [122]. The τ–ω model remains foundational: SM influences soil emissivity via dielectric changes, while vegetation optical depth (τ) and single-scattering albedo (ω) control the vegetation contribution. Recent parameter refinements, accounting for canopy structure and VOD-SM coupling, improve robustness under moderate to dense vegetation [148].

Advanced schemes such as joint SM-VOD-ω retrievals, exemplified by the spatially constrained multi-channel algorithm (S-CMCA), simultaneously estimate these three parameters from L-band observations. This reduces trade-offs and stabilizes SM estimates in heterogeneous cover [104]).

The L-MEB model and simplified variants (e.g., modified τ-ω, H-Q-N) efficiently simulate vegetation–soil interactions with a lower computational cost, improving retrieval in structurally complex canopies [126,149]. Two-stream (2S) models offer more realistic canopy representations by modeling upward and downward radiation, which enhances SM retrieval in tall or multi-layer vegetation compared with τ-ω alone [150].

Frequency-dependent inversion has also advanced: P-band τ–ω modeling improves penetration through dense biomass, reducing bias in forested areas relative to L-band [151]. Finally, 3D and hybrid RTMs, including discrete or stochastic canopy architectures, address the limitations of 1D/2D models by better capturing canopy heterogeneity and structural scattering, which significantly enhances SM estimation in forests [152,153].

In summary, these radiative transfer approaches, ranging from classic τ-ω to multi-parameter inversion and 3D modeling, directly contribute to more accurate, physically grounded SM retrieval across different vegetation types.

4. Soil Moisture Products: Main Datasets

Over the years, researchers have accumulated a vast number of soil moisture (SM) datasets by employing different inversion methods across various geographical regions, soil types, and vegetation covers.

In this study, publicly available SM datasets are classified into four primary categories based on their sensor type and inversion method: passive microwave-based, active microwave-based, multi-sensor merged, and reanalysis data-based products. From a physical perspective, this categorization reflects the fundamental differences in sensor characteristics, received signals, and data processing principles.

Passive microwave-based datasets typically rely on brightness temperature (Tb) measured by radiometers or estimating soil dielectric properties via radiative transfer models (RTMs) to invert SM. These products provide long-term time series, global coverage, and a stable large-scale performance, but they generally feature a low spatial resolution and are sensitive to vegetation cover and soil surface roughness.

Active microwave-based datasets are primarily produced using radar observations (SAR or scatter meters) that actively transmit microwave pulses and record the backscattered signals and invert SM through backscattering models. These products offer a higher spatial resolution, ranging from the meter to kilometer scale. Yet they remain vulnerable to the effects of vegetation and surface roughness.

From the perspective of data processing strategies, SM datasets can also be categorized as multi-sensor merged products or reanalysis data-based products. Reanalysis data-based SM is generally not inverted directly from satellite observations. Instead, it is generated by land surface models (LSMs) coupled with data assimilation techniques. These datasets exhibit strong spatial–temporal continuity, but their accuracy may be influenced by model inputs and parameterization processes.

In contrast, multi-sensor merged products typically estimate SM indirectly using variables such as land surface temperature (LST), vegetation indices (NDVI), and evapotranspiration models. Such products usually have higher spatial resolutions; however, because they predominantly rely on optical RS, they are generally limited to shallow surface SM, are susceptible to cloud contamination, and their accuracy can be affected by the indirect nature of the modeling workflows.

These datasets provide critical data for in-depth analysis and research. To comprehensively explain these datasets and provide precise data sources for subsequent research, the following table (Table 3) summarizes existing publicly available SM data products and describes the characteristics of each dataset.

Table 3.

Summary of publicly available soil moisture products, with all links verified as of 4 December 2025; the information in the table is primarily based on Fan et al. [115], with updates, improvements, and additional data contributed by us.

5. Analysis and Discussion

Despite remarkable progress in soil moisture (SM) monitoring over the past decades, existing methods still suffer from significant limitations in their practical applications. In situ observations are constrained by spatial scale, deployment conditions, and maintenance costs. Optical remote sensing (RS) approaches are highly sensitive to atmospheric, vegetation, and other environmental factors. Active and passive microwave techniques are strongly affected by surface cover, topography, and spatial heterogeneity, while model-based methods are often limited by parameter uncertainties and oversimplified assumptions. These shortcomings highlight the pressing need for further advancements in SM monitoring, moving beyond single-method frameworks towards integrated systems that combine multi-source data, advanced physical models, and machine learning. Furthermore, the development of standardized validation protocols and cross-regional benchmarks will be essential to ensure the robustness and global applicability of future SM products.

5.1. Overview of Soil Moisture Monitoring Methods

In this section, we summarize and discuss the limitations of several SM monitoring approaches mentioned above, including in situ observation methods, optical RS-based inversion, thermodynamic and energy balance-based approaches, and passive/active microwave remote sensing combined with radiation transfer models.

5.1.1. In Situ Soil Moisture Measurements

In situ observation techniques provide real-time, high-accuracy SM measurements that are essential for applications in agriculture, water resources management, and related fields, thereby supporting timely production and engineering decision-making [196]. However, in practical scenarios, these methods are typically restricted to small-scale and high-sensitivity studies and are unable to provide large-scale or multi-perspective observations. Their broader deployment is further limited by power supply constraints, network and communication requirements [197], operational complexity, environmental disturbances, and the need for long-term maintenance [198]. These limitations often lead to increased costs [199], potential ecological disturbance, and even health risks to operators, particularly in systems involving cosmic ray neutron sensing [200,201]. In addition, the performance is strongly influenced by site-specific soil properties such as salinity, which may introduce measurement uncertainties or degrade sensor stability [202]. Consequently, the spatial applicability of in situ techniques remains limited to a certain extent. Nevertheless, these methods continue to serve as indispensable tools for obtaining high-precision SM observations and remain fundamental for small-scale process studies as well as for the calibration and validation of remotely sensed SM products.

5.1.2. Optical RS and Index-Based Methods

Index-based SM inversion is strongly affected by vegetation cover, atmospheric conditions, terrain and surface roughness, and the physical dependencies embedded in each index. These factors introduce substantial variability in retrieval accuracy. This section provides a simplified yet rigorous explanation of these influences.

- (a)

- Vegetation Cover-Driven Variations in Index Sensitivity

In sparsely vegetated or bare soil areas (NDVI < 0.3), brightness temperature and related microwave indices such as SWI and MPDI maintain a strong sensitivity to SM. Low-frequency microwave observations couple effectively with soil dielectric properties under minimal canopy conditions [203], enabling the direct inversion of near-surface moisture. Temperature-based indices such as TVDI, although constrained by difficulty in defining the dry–wet edge, often show stable LST–VI relationships [204]. Incorporating NDVI improves the statistical connection with shallow-layer SM, as evidenced in multiple field evaluations [205].

In moderately vegetated regions (0.3 ≤ NDVI ≤ 0.6), canopy energy dissipation alters the thermal signal, reducing the application of TVDI, CWSI, WDI, and TSMI. The mixed response from transpiration and soil evaporation the requires joint consideration of vegetation status and water availability. For microwave indices such as SWI and MPDI, inversion sensitivity declines [206], necessitating corrections using LAI or VWC or the use of coupled soil–vegetation modeling approaches [207].

In dense vegetation (NDVI > 0.6), both microwave and thermal infrared signals are dominated by canopy water fluxes. Indices such as TVDI and TSMI thus reflect hydrological water stress rather than SM. Accurate inversion requires canopy scattering or radiative transfer models [208] or integration with root water content and reanalysis with ground observations [21]. Vegetation structural differences further introduce systematic inversion biases [209].

- (b)

- Atmospheric, Topographic, and Surface Roughness Effects

Thermal infrared indices (TVDI, TSMI, VTCI, CWSI) are sensitive to atmospheric conditions because accurate LST inversion depends on atmospheric correction. Clouds, aerosols, and water vapor affect radiative transfer, generating LST errors or observation gaps, and weakening VI–LST relationships [210]. In practice, methods such as cloud masking, temporal compositing, and constructing dry–wet boundaries from clear-sky samples are typically employed for mitigation. Topographic features (e.g., slope, and shadow) introduce distortions in illumination and BRDF effects, affecting both the absolute values and the structure relationship between vegetation indices and LST, thereby necessitating topographic correction or terrain-stratified modeling. CWSI depends on canopy–air temperature differences and meteorological variables, particularly VPD; its accuracy relies heavily on the correct construction of the non-water stress baseline [211]. Biases in wind speed, VPD, or reference temperature can significantly distort the correspondence between CWSI and SM.

In contrast, microwave indices (SWI, MPDI) are less influenced by atmospheric interference but exhibit brightness temperature anomalies shortly after rainfall [212], requiring rainfall filtering or temporal smoothing. Additionally, microwave backscatter and brightness temperature exhibit high sensitivities to incidence angle, needing rigorous geometric correction, particularly over undulating terrain [213]. Surface roughness further alters microwave scattering and polarization behavior [214], which affect the response of the soil dielectric constant changes, requiring parameterization or multi-polarization and time series strategies to reduce its impact [215].

5.1.3. Thermodynamics and Energy Balance Methods

Methods based on thermodynamics and surface energy balance offer notable advantages for inverting land surface temperature and, subsequently, SM. However, they also present several limitations. These approaches are highly sensitive to meteorological conditions, land surface temperature, vegetation cover, and aerodynamic resistance [216], which may lead to data loss or reduced accuracy [217]. The surface energy balance equation involves multiple physical process variables, and in practice, substantial uncertainties arise in the estimation of net radiation, soil heat flux, sensible heat flux, and latent heat flux [218]. Calculations of sensible and latent heat fluxes often rely on empirical parameterizations, which hinder accurate flux partitioning and frequently result in incomplete energy balance closure [219], thereby reducing inversion accuracy. In complex terrains such as mountainous regions, spatial heterogeneity in soils, topography, and vegetation structure further complicates land surface temperature inversion and increases the difficulty of achieving energy balance at the pixel scale [220], limiting the applicability of these methods across different study areas. Moreover, in detecting dynamic processes such as precipitation events, these approaches often exhibit time lags or biases, making it difficult to capture rapid changes in SM [221]. Such limitations are particularly prominent in seasonally frozen regions, where errors in regional SM inversion may become more significant [222,223].

5.1.4. Microwave RS Methods and Radiation Transfer Method

Microwave RS-based SM inversion is inherently dependent on the parameterization of electromagnetic scattering and radiative transfer processes and therefore is highly sensitive to perturbations from signal contamination, vegetation canopy conditions, surface roughness, terrain heterogeneity, and sensor frequency. First, radio-frequency interference (RFI) can introduce systematic biases and increase uncertainties in passive L-band observations, often resulting in data distortion or increased uncertainty, particularly in regions with strong RFI sources [224]. Second, vegetation coverage, canopy structure, and vegetation water content alter the observable vegetation optical depth (VOD) and single-scattering characteristic, substantially attenuating the microwave signal from soil. Standard τ–ω and semi-empirical scattering models rely heavily on prior assumptions related to vegetation type and growth stage, which constrains cross-regional model applicability and leads to inaccuracies in complex vegetated areas [225]. Third, surface roughness and soil texture impose nonlinear impacts on radar scattering. Commonly used semi-empirical models (e.g., Dubois, Oh, IEM) often fail to represent realistic heterogeneous field conditions [226], and roughness parameters are difficult to estimate accurately at large scales, thereby amplifying inversion uncertainties. Fourth, the vertical sensing depth of microwave signals varies with frequency, because shorter wavelengths respond mainly to the near-surface layer, whereas longer wavelengths penetrate deeper, resulting in depth mixing effects influenced by the vertical SM gradient, soil texture, and vegetation cover. Consequently, SM retrieved from a single band or polarization represents an average moisture which may not correspond to the desired soil layer [227]. Fifth, cross-sensor fusion and data assimilation remain challenging due to inconsistencies in observation frequency, polarization, orbital phases, and spatial resolution, which collectively hinder the continuity between temporal sequences and spatial data [228]. Although empirical or semi-empirical priors may improve local retrieval performance, they also introduce additional parameter uncertainties and facilitate bias propagation.

In theory, high-dimensional numerical models from radiative transfer models (RTMs) provide a more comprehensive description of the transmission, scattering, and absorption processes within the soil–vegetation canopy–atmosphere system, thereby offering superior physical interpretability under complex surface conditions. However, these models often suffer from parameterization complexity, sensitivity to canopy multi-scattering and structural heterogeneity, and substantial demands for training data and computational resources [229]. These limitations restrict their operational utility, particularly in regions with a high canopy optical depth or dense vegetation. Overall, although microwave- and RTM-based methods offer a theoretically robust foundation for SM inversion, practical applications require the integration of multi-frequency and multi-polarization observations, robust in situ measurements, and the explicit quantification of parameter uncertainty, such as through sensitivity analysis, error propagation analysis, and other diagnostic tools, to enhance model stability, transferability, and reliability across diverse land surface conditions.

5.2. Analysis of Soil Moisture Data Products

Publicly available SM datasets provide an indispensable foundation for hydrological, agricultural, and climate research by offering long-term and large-scale observations. However, different types of datasets exhibit fundamental differences in spatial scale, temporal coverage, physical interpretability, and uncertainty sources. A systematic evaluation of these differences is essential for clarifying application boundaries and supporting subsequent data assimilation, downscaling, and multi-source fusion strategies.

5.2.1. Optical and Microwave Remote Sensing Datasets

Satellite-based SM products (e.g., SMOS, SMAP, ASCAT, AMSR2, and ESA-CCI) deliver surface SM (approximately 0–10 cm) at global scales with strong temporal continuity, making them valuable for climate analysis and drought monitoring. However, several inherent limitations remain. First, their native spatial resolution is typically low (e.g., 25–50 km), which constrains their applicability in agricultural or watershed-scale studies. Although downscaling approaches can improve spatial detail, their generalization ability strongly depends on the representativeness of the training environment. Second, microwave signals primarily respond to surface moisture, and their penetration depth varies across frequencies, making the retrieved average moisture an imperfect proxy for root water or depth moisture. Deeper-layer inversion therefore requires in situ measurements or physically based models. Third, retrieval accuracy is strongly affected by environmental factors such as vegetation cover [230], surface roughness, freeze–thaw cycles, snow cover, radio-frequency interference (RFI), and soil salinity. These influences vary dynamically in space and time [231], leading to substantial uncertainties when transferring algorithms across regions. To mitigate these issues, satellite–in situ joint validation, triple collocation analysis, and field-based error modeling are commonly employed to assess and correct remote sensing products [232].

5.2.2. Model Simulation and Data Fusion Products

SM datasets derived from land surface models (e.g., Noah, CLM), hybrid modeling frameworks, and multi-source fusion systems (e.g., GLDAS and regional fusion products) offer continuous spatiotemporal coverage and multi-layer SM information, addressing the observational gaps inherent to satellite and ground networks. Their performance, however, is highly sensitive to the quality of data (PET, ET, and soil parameters). Errors in inputs or inaccurate parameters (e.g., soil texture, rooting structure) can propagate through the modeling or assimilation chain. Furthermore, fusion algorithms, from simple weighted averaging to advanced machine learning architectures, can enhance spatial resolution but also introduce new uncertainties related to training bias, the dependence on prior assumptions, and potential overfitting [233]. Purely data-driven fusion products often lack physical constraints and may perform poorly during extreme hydrological events such as droughts, floods, or freeze–thaw transitions [234]. Recently, physics-guided machine learning approaches have emerged as a promising direction, integrating physical laws with data-driven flexibility. To ensure reliability, sensitivity analyses, triple collocation analyses, and calibrations with representative in situ observations are recommended.

5.2.3. Reanalysis Datasets

Reanalysis datasets (e.g., ERA5-Land, MERRA-2, GLDAS) integrate physical models with observational data assimilation to produce long-term, multi-layer SM inversion suitable for climate and hydrological trend analyses. Their errors primarily originate from model assumptions and the inaccuracy of data. Their performance can degrade substantially in regions with complex terrain (e.g., mountainous areas) or extreme climate regimes (e.g., freeze–thaw and seasonal snow processes) [235]. Recent studies further indicate that reanalysis products exhibit large discrepancies in spatial–temporal correlation and bias patterns, with some datasets tending to overestimate SM in arid areas and underestimate it in humid regions [236]. Consequently, the broad use of reanalysis SM still requires bias correction and continuous evaluation by ground-based observations.

5.3. Research Trends and Future Outlook

The future of SM monitoring will increasingly depend on the integration of multi-disciplinary technologies, particularly artificial intelligence, big data analytics, advanced RS systems, and next-generation ground observation networks. With the upcoming NISAR and ROSE-L missions providing high-quality L-/S-band and multi-polarization SAR observations [237,238,239,240,241], long-standing limitations related to vegetation penetration, multi-scale surface roughness representation, and model structural uncertainty are expected to be substantially mitigated. These datasets will support physics-informed machine learning and deep learning frameworks, enhancing the accuracy and robustness of SM inversion under diverse surface conditions. Future developments are expected to focus on four main directions.

5.3.1. Multi-Source Data Fusion—Enhancing Consistency and Spatiotemporal Coverage

A promising trend is the fusion of L-band SAR, GNSS-R, optical/thermal infrared, reanalysis, and in situ measurements to jointly improve both the accuracy and applicability of SM products [242]. For instance, Zhang et al. in 2023 developed an LSTM-based model integrating GNSS-R data with radiometer observations, yielding a standard deviation of 0.013 m3/m3 in SM retrieval [243]. However, fusion is challenged by inconsistent calibration, mismatched spatial and temporal resolutions, and different sensing mechanisms. Researchers often mitigate these issues via data assimilation, cross-scale normalization, and uncertainty-weighted fusion. Yet, uncertainty quantification across different sources is not yet standardized, and high-accuracy, globally distributed data remain sparse in coverage. Future work needs to optimize multi-source cooperation strategies and leverage deep learning to enhance the robustness and global generalization of SM inversion.

5.3.2. Deep Learning and Physics-Guided Machine Learning—Improving Generalization and Interpretability

Machine learning, especially deep learning, increasingly appears in SM monitoring, often combined with physical priors such as radiative transfer models (RTMs) to boost accuracy [244,245]. For example, Singh & Gaurav in 2024 proposed a physics-informed neural network (PIML-SM) that incorporates an improved integral equation model into the loss function. Their model achieved an R of 0.94 and RMSE of 0.019 m3/m3 when using Sentinel-1/2 imagery [246]. Despite their success, these methods still face challenges: the limited representativeness of training samples, overfitting risks, and “black-box” behavior with weak interpretability. To address these, future research should incorporate strategies such as transfer learning, domain adaptation, physics-constrained networks, and uncertainty quantification (e.g., ensemble methods or Bayesian neural networks).

5.3.3. High-Order Radiative Transfer Models and Multi-Scale Roughness—Reducing Structural Bias

L-band signals are highly sensitive to vegetation structure and surface roughness. High-order RTMs that include multiple scattering mechanisms can more realistically estimate scattering, while multi-scale roughness parameterizations help reduce the biases inherent in empirical models [247]. For example, in 2023, Munoz-Martin et al. demonstrated that the precise modeling of surface roughness is critical for GNSS-R SM inversion: roughness variations can induce tens of dB differences in reflectivity, significantly affecting retrieval errors [248]. Yet, deploying these models in practice is challenging because they require high-dimensional parameters (e.g., roughness spectra, 3D vegetation structure) that are difficult to measure directly. One method is to use high-fidelity RTMs in local regions to train machine learning models that can generalize these parameters to broader scales, thereby balancing physical realism with computational tractability.

5.3.4. SM Data Product Development via Multi-Source Fusion and AI—Toward Standardized, High-Resolution Products

The next generation of SM products is likely to emerge from the fusion of multi-sensor observations (e.g., GNSS-R, SAR, optical) and AI-optimized algorithms, yielding high-resolution, multi-scale, cross-regional, and standardized datasets. For example, Li et al. employed AutoML frameworks within a multi-sensor fusion architecture to build automated SM inversion models [245].

To further address the issue of regional inconsistency in data products, approaches that utilize fusion algorithms calibrated with physical models to generate refined downscaled datasets can be carried out. Additionally, an uncertainty quantification framework needs to be established to mitigate disparities in data validation scales, thereby ensuring both the precision and applicability of data products. Solutions may involve unified data formats (e.g., grid, temporal), physics model-calibrated fusion schemes, and hierarchical product structures that balance accuracy and applicability. Ultimately, by establishing systematic uncertainty frameworks and calibration procedures, these products can achieve both regional precision and applicability.

5.4. Key Challenges in Future

Looking ahead, several core challenges remain in SM monitoring:

The exploration of fusion technology of multi-source data and the establishment of uncertainty analysis frameworks for data evaluation standards

The interpretability and regional generalization of physics-guided ML models.

The practical deployment and validation of high-order RTMs and multi-scale parameterizations.

The development of standardized, high-resolution SM products through data assimilation and AI optimization.

Next-generation, high-quality L-band and multi-source observations are expected to provide the technical foundation to address these challenges, accelerating the construction of a more accurate, scalable, and globally applicable SM monitoring system.

6. Conclusions

Soil moisture, as a crucial variable in the hydrological cycle and energy balance, is a key component in water resource management, agricultural production, ecological protection, and disaster early warning. In recent years, advances in different approaches have significantly improved soil moisture monitoring, enabling large-scale, long-term, and multi-source observations and enhancing the understanding of land–atmosphere interactions. This review systematically surveyed the main soil moisture monitoring methods, including in situ measurements, optical and microwave remote sensing, thermodynamic and energy balance approaches, and methods based on radiation transfer models. In addition, the advantages and limitations of each method were analyzed and representative publicly available datasets were compared to provide research references and illustrate data diversity. Despite notable improvements in monitoring capability, challenges remain in complex environmental conditions, parameter uncertainty, and cross-regional applicability. Future research should focus on multi-source data integration, combining physical models with machine learning, establishing a standardized validation principle, and developing cross-regional benchmarks to enhance product robustness and global applicability. Multi-source data fusion, deep learning optimization, and the construction of soil moisture data-sharing platforms will play key roles in improving accuracy and real-time monitoring.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, and writing—original draft preparation, R.L.; data curation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, C.C. and R.Z.; project administration and funding acquisition, R.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (Third Xinjiang Scientific Expedition Program, Grant No. 2021xjkk0403), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (National Natural Science Foundation project, Grant No. 42071049), and the Xinjiang Tarim River Basin Authority, China (Project for Efficient Utilization of Water Resources in the Tarim River Basin, Grant No. TGJJG-2022KYXM0002).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this research was completely sourced from public repositories. Detailed references are provided in the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all co-authors for their support and assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. Special appreciation is extended to Zhong Ruisen, for securing the financial support for this work. The authors are also grateful to the reviewers and editors for their valuable comments and constructive suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SM | Soil Moisture |

| RS | Remote Sensing |

| RTM | Radiative Transfer Model |

| ET | Evapotranspiration |

| TDR | Time Domain Reflectometry |

| FDR | Frequency Domain Reflectometry |

| CIDR | Capacitance and Impedance Dielectric Reflectometry |

| GPR | Ground-Penetrating Radar |

| RFI | Radio-Frequency Interference |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| CRNS | Cosmic Ray Neutron Probe |

| VTCI | Vegetation Temperature Condition Index |

| SWI | Soil Water Index |

| LST | Land Surface Temperature |

| VI | Vegetation Index |

| TVDI | Temperature Vegetation Drought Index |

| Ts | Temperature of the Surface |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| MPDI | Modified Perpendicular Drought Index |

| TIR | Thermal–Infrared Remote Sensing |

| ATI | Apparent Thermal Inertia |

| SEBAL | Surface Energy Balance Algorithm for Land |

| WCM | Water Cloud Model |

| RF | Random Forest |

| VOD | Vegetation Optical Depth |

| ACO | Ant Colony Optimization |

| SSA | Sparrow Search Algorithm |

| VMC | Vegetation Moisture Content |

| SCA | Single-Channel Algorithm |

| DCA | Dual-Channel Algorithm |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| IEM | Integral Equation Model |

| S-CMCA | Spatially Constrained Multi-Channel Algorithm |

| Tb | Brightness Temperature |

| LSM | Land Surface Model |

References

- Saboori, M.; Ghag, K.S.; Panchanathan, A.; Patro, E.R.; Haghighi, A.T. Assessing feature importance for forecasting soil moisture in subarctic regions using gridded historical and forecasted climate data. Geoderma 2025, 458, 117304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, S.I.; Corti, T.; Davin, E.L.; Hirschi, M.; Jaeger, E.B.; Lehner, I.; Orlowsky, B.; Teuling, A.J. Investigating soil moisture–climate interactions in a changing climate: A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2010, 99, 125–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, A.A.; Leng, P.; Li, Y.-X.; Liao, Q.-Y.; Geng, Y.J.; Ma, J.; Sun, Y.; Song, X.; Duan, S.-B.; Li, Z.-L. Remote sensing of root zone soil moisture: A review of methods and products. J. Hydrol. 2025, 656, 133002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, I. Soil moisture forecasting from sensors-based soil moisture, weather and irrigation observations: A systematic review. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 10, 100692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, X.; Zhu, W.; Han, Y.; Lv, A. Enhancing root-zone soil moisture estimation using Richards’ equation and dynamic surface soil moisture data. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 312, 109460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susha Lekshmi, S.U.; Singh, D.N.; Shojaei Baghini, M. A critical review of soil moisture measurement. Measurement 2014, 54, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xu, C.; Long, J.; Zhang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Li, L. Soil moisture deficits triggered by increasing compound drought and heat events during the growing season in Arid Central Asia. J. Hydrol. 2025, 660, 133397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Albergel, C.; Balenzano, A.; Brocca, L.; Cartus, O.; Cosh, M.H.; Crow, W.T.; Dabrowska-Zielinska, K.; Dadson, S.; Davidson, M.W.J.; et al. A roadmap for high-resolution satellite soil moisture applications—Confronting product characteristics with user requirements. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 252, 112162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mane, S.; Das, N.; Singh, G.; Cosh, M.; Dong, Y. Advancements in dielectric soil moisture sensor Calibration: A comprehensive review of methods and techniques. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 218, 108686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Wigneron, J.-P.; Kumar, S.; Dong, J.; Wagner, W.; Cosh, M.H.; Bosch, D.D.; Collins, C.H.; Starks, P.J.; Seyfried, M.; et al. Global scale error assessments of soil moisture estimates from microwave-based active and passive satellites and land surface models over forest and mixed irrigated/dryland agriculture regions. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 251, 112052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhou, G. Estimation of Soil Moisture from Optical and Thermal Remote Sensing: A Review. Sensors 2016, 16, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, T.K.; Feng, J.; Bilawal, F.; Shehab, S.H.; Trinh, K.T.; Yang, Y.; Rudiger, C.; Walker, J.P.; Karmakar, N.C. Lightweight and Compact Radiometers for Soil Moisture Measurement: A review. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2022, 10, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Y. Advances in the Quality of Global Soil Moisture Products: A Review. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaeian, E.; Paheding, S.; Siddique, N.; Devabhaktuni, V.K.; Tuller, M. Estimation of root zone soil moisture from ground and remotely sensed soil information with multisensor data fusion and automated machine learning. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 260, 112434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya Moreshwar Meshram, S.; Adla, S.; Jourdin, L.; Pande, S. Review of low-cost, off-grid, biodegradable in situ autonomous soil moisture sensing systems: Is there a perfect solution? Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 225, 109289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Kong, J.; Wang, L.; Zhong, Y. Estimating evapotranspiration using an improved two-source energy balance model coupled with soil moisture in arid and semi-arid regions. J. Hydrol. 2025, 659, 133283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.-H.; Yuan, Z.-R.; Wang, Z.Z.; Liu, X. Improved rainfall infiltration model for probabilistic slope stability assessment considering transition layers and spatial variability. Eng. Geol. 2025, 353, 108096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, D.; Manfreda, S.; Keller, K.; Smithwick, E.A.H. Predicting root zone soil moisture with soil properties and satellite near-surface moisture data across the conterminous United States. J. Hydrol. 2017, 546, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Qiu, T.; Wang, T.; Zeng, C.; Zhang, B.; Shen, H. Seamless global daily soil moisture mapping using deep learning based spatiotemporal fusion. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 139, 104517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yang, Q.; Li, J.; Jin, T.; Yuan, Q.; Shen, H.; Zhang, L. Global multi-scale surface soil moisture retrieval coupling physical mechanisms and machine learning in the cloud environment. Remote Sens. Environ. 2025, 329, 114928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edokossi, K.; Calabia, A.; Jin, S.; Molina, I. GNSS-Reflectometry and Remote Sensing of Soil Moisture: A Review of Measurement Techniques, Methods, and Applications. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Mao, K.; Guo, Z.; Shi, J.; Bateni, S.M.; Yuan, Z. Review of GNSS-R Technology for Soil Moisture Inversion. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamichhane, M.; Mehan, S.; Mankin, K.R. Soil Moisture Prediction Using Remote Sensing and Machine Learning Algorithms: A Review on Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senanayake, I.P.; Pathira Arachchilage, K.R.L.; Yeo, I.-Y.; Khaki, M.; Han, S.-C.; Dahlhaus, P.G. Spatial Downscaling of Satellite-Based Soil Moisture Products Using Machine Learning Techniques: A Review. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Paul, P.K.; Dobesova, Z. Present status of soil moisture estimation by microwave remote sensing. Cogent Geosci. 2015, 1, 1084669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Zhang, R.; Pham, H.; Sharma, A. A Review of Satellite-Derived Soil Moisture and Its Usage for Flood Estimation. Remote Sens. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 2, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, M.W.; Tang, J.; Sarwar, A.; Shah, S.; Saddique, N.; Khan, M.U.; Imran Khan, M.; Nawaz, S.; Shamshiri, R.R.; Aziz, M.; et al. Soil Moisture Measuring Techniques and Factors Affecting the Moisture Dynamics: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Gao, W.; Shamshiri, R.R.; Tao, S.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Su, G. Review of research progress on soil moisture sensor technology. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2021, 14, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Xiong, J.; Ma, J.; Jin, B.; Zhang, D. Sensor-free Soil Moisture Sensing Using LoRa Signals. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2022, 6, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, T.J.; Bell, J.P.; Baty, A.J.B. Soil-moisture measurement by an improved capacitance technique. J. Hydrol. 1987, 93, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.; Elhajj, I.H.; Asmar, D.; Bashour, I.; Kidess, S. Experimental Evaluation of Low-Cost Resistive Soil Moisture Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Multidisciplinary Conference on Engineering Technology (IMCET), Beirut, Lebanon, 2–4 November 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodasingi, V.K.; Rao, B.; Pillai, H.K. Laboratory Evaluation of a Low-Cost Soil Moisture and EC Sensor in Different Soil Types. IEEE Trans. AgriFood Electron. 2024, 2, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robock, A.; Vinnikov, K.Y.; Srinivasan, G.; Entin, J.K.; HoIIinger, S.E.; Speranskaya, N.A.; Liu, S.; Namkhai, A. The global soil moisture data bank. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2000, 81, 1281–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianessi, S.; Polo, M.; Stevanato, L.; Lunardon, M.; Ahmed, H.S.; Weltin, G.; Toloza, A.; Budach, C.; Biro, P.; Francke, T.; et al. Assessment of a new non-invasive soil moisture sensor based on cosmic-ray neutrons. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Agriculture and Forestry (MetroAgriFor), Trento-Bolzano, Italy, 3–5 November 2021; pp. 290–294. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S.B.; Wraith, J.M.; Or, D. Time domain reflectometry measurement principles and applications. Hydrol. Process. 2002, 16, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarantino, A.; Ridley, A.M.; Toll, D.G. Field Measurement of Suction, Water Content, and Water Permeability. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2008, 26, 751–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.H.; Jeong, J.; Choi, M. Extension of cosmic-ray neutron probe measurement depth for improving field scale root-zone soil moisture estimation by coupling with representative in-situ sensors. J. Hydrol. 2019, 571, 679–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannes, M.; Wollschläger, U.; Schrader, F.; Durner, W.; Gebler, S.; Pütz, T.; Fank, J.; von Unold, G.; Vogel, H.J. High-resolution estimation of the water balance components from high-precision lysimeters. Hidrol. Earth System. Sci. Discuss. 2015, 12, 569–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, A.; Nehls, T.; Schonsky, H.; Wessolek, G. Separating precipitation and evapotranspiration from noise—A new filter routine for high-resolution lysimeter data. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 18, 1189–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, J.A.; Sperl, C.; Bouten, W.; Verstraten, J.M. Soil Water Content Measurements at Different Scales Accuracy of Time. J. Hydrol. 2001, 245, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, A.; Ning, D.; Liu, Z.; Duan, A.; Wang, J. Analysis of the Accuracy of an FDR Sensor in Soil Moisture Measurement under Laboratory and Field Conditions. J. Sens. 2021, 2021, 6665829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulos, G.P.; Ireland, G.; Barrett, B. Surface soil moisture retrievals from remote sensing: Current status, products & future trends. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2015, 83-84, 36–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhli, M.; Schrön, M.; Zreda, M.; Schmidt, U.; Dietrich, P.; Zacharias, S. Footprint characteristics revised for field-scale soil moisture monitoring with cosmic-ray neutrons. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 5772–5790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]