Morphometric Analysis and Emplacement Dynamics of Folded Terrains at Avernus Colles, Mars

Highlights

- Nineteen distinct folded terrains with arcuate morphologies have been analyzed via remote sensing to determine strain rates and emplacement duration.

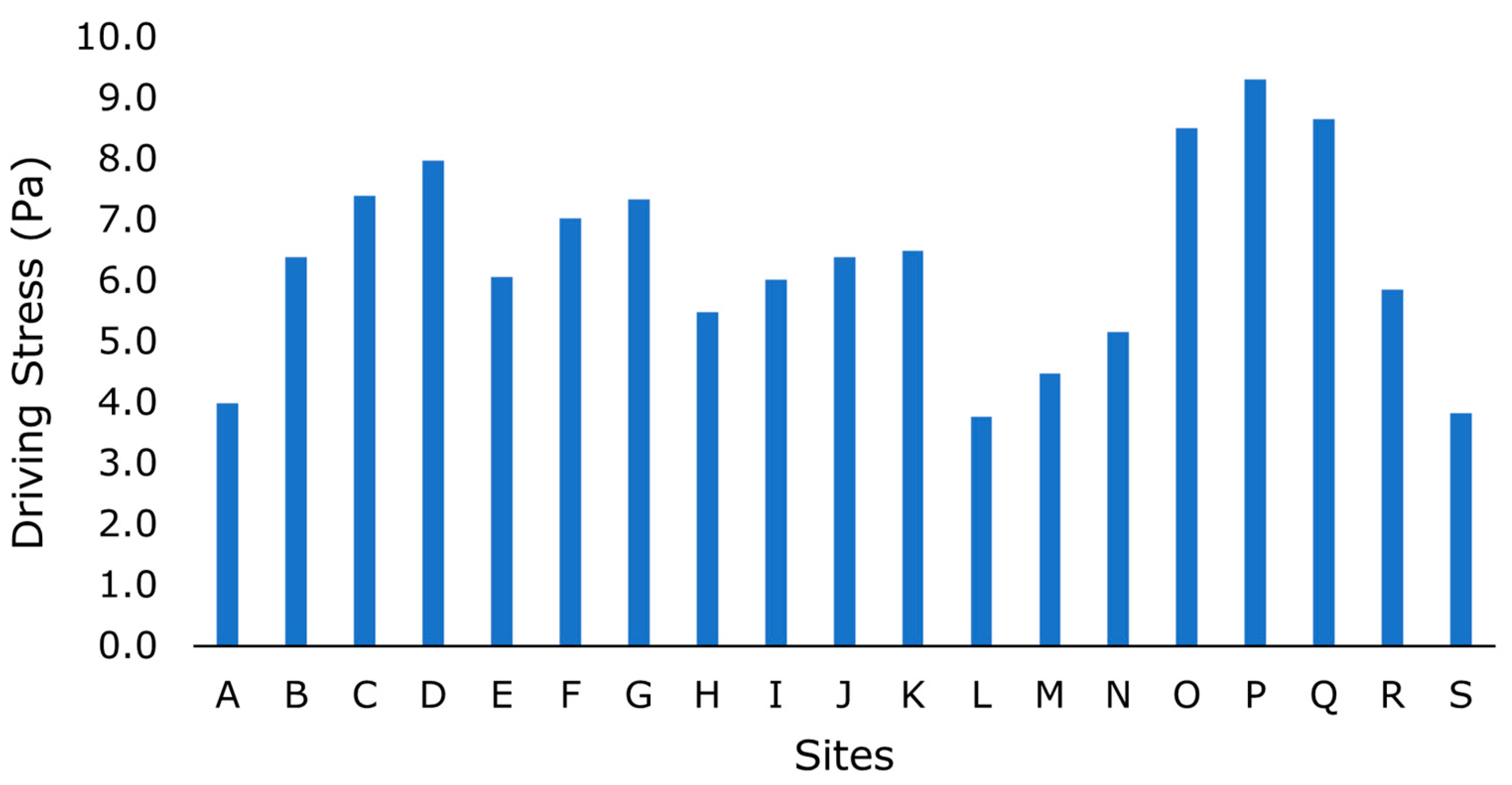

- Calculated driving stress using a simple two-layer model.

- The derived model shows strain rates approximately 10−7 s−1.

- Duration estimates of these terrains ranged from 16–38 days, consistent with surrounding Martian geology.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of Key Observations

4.2. Possible Folding Mechanisms and Diagnostic Criteria

4.3. Integration of Regional Tectono-Volcanic Context

4.4. Substrate Structure and Heterogeneity

4.5. Interpretation of the North–South Cyclic Pattern

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| JMARS | Java Mission-planning Analysis for Remote Sensing |

| MOLA | Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter |

| THEMIS | Thermal Emission Imaging System |

| CTX | Context Camera |

| MRO | Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter |

| MGS | Mars Global Surveyor |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Models |

| CRISM | Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars |

References

- Mouginis-Mark, P.J.; Wilson, L.; Head, J.W.; Brown, S.H.; Hall, J.L.; Sullivan, K.D. Elysium Planitia, Mars: Regional geology, volcanology, and evidence for volcano-ground ice interactions. Earth Moon Planets 1984, 30, 149–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohm, J.M.; Anderson, R.C.; Barlow, N.G.; Miyamoto, H.; Davies, A.G.; Taylor, G.J.; Baker, V.R.; Boynton, W.V.; Keller, J.; Kerry, K.; et al. Recent geological and hydrological activity on Mars: The Tharsis/Elysium corridor. Planet. Space Sci. 2008, 56, 985–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangold, N.; Loizeau, D.; Poulet, F.; Ansan, V.; Baratoux, D.; LeMouelic, S.; Bardintzeff, J.; Platevoet, B.; Toplis, M.; Pinet, P.; et al. Mineralogy of recent volcanic plains in the Tharsis region, Mars, and implications for platy-ridged flow composition. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2010, 294, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crown, D.A.; Ramsey, M.S. Morphologic and thermophysical characteristics of lava flows southwest of Arsia Mons, Mars. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2017, 342, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, E.R.; Head, J.W., III. Amazonis Planitia: The role of geologically recent volcanism and sedimentation in the formation of the smoothest plains on Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2002, 107, 11-1–11-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, C.W.; Fagents, S.A.; Wilson, L. Explosive lava-water interactions in Elysium Planitia, Mars: Geologic and thermodynamic constraints on the formation of the Tartarus Colles cone groups. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2010, 115, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platz, T.; Michael, G. Eruption history of the Elysium volcanic province, Mars. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2011, 312, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerber, L.; Dickson, J.L.; Head, J.W.; Grosfils, E.B. Polygonal ridge networks on Mars: Diversity of morphologies and the special case of the Eastern Medusae Fossae Formation. Icarus 2017, 281, 200–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crumpler, L. Sites of Potential Long Term Sub-surface Water, Mineral-rich Environments, and Deposition in South Elysium Planitia, Hellas-Dao Vallis, Isidis Basin, and Xanthe-Hypanis Vallis: Candidate Mars Science Laboratory Landing Sites. In Proceedings of the First Landing Site Workshop for the 2009 Mars Science Laboratory, Pasadena, CA, USA, 31 May–2 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, R.P. Mars: Fretted and chaotic terrains. J. Geophys. Res. 1973, 78, 4073–4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, H.J.; Wilson, L.; Mitchell, K.L. Formation of Aromatum Chaos, Mars: Morphological development as a result of volcano-ice interactions. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2006, 111, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meresse, S.; Costard, F.; Mangold, N.; Masson, P.; Neukum, G. Formation and evolution of the chaotic terrains by subsidence and magmatism: Hydraotes Chaos, Mars. Icarus 2008, 194, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roda, M.; Kleinhans, M.G.; Zegers, T.E.; Oosthoek, J.H. Catastrophic ice lake collapse in Aram Chaos, Mars. Icarus 2014, 236, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzzi, E.; Rossi, A.P.; Carli, C.; Altieri, F. Tectono-magmatic, sedimentary, and hydrothermal history of Arsinoes and Pyrrhae Chaos, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2020, 125, e2019JE006341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzzi, E.; Rossi, A.P.; Massironi, M.; Pozzobon, R.; Corti, G.; Maestrelli, D. Caldera collapse as the trigger of Chaos and fractured craters on the Moon and Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL092436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, G.B.M. Chaotic Terrain (Mars). In Encyclopedia of Planetary Landforms; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, N.H.; Gupta, S.; Kim, J.-R.; Muller, J.-P.; Le Corre, L.; Morley, J.; Lin, S.-Y.; McGonigle, C. Constraints on the origin and evolution of Iani Chaos, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2011, 116, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, M.G.; Tanaka, K.L. Related magma–ice interactions: Possible origins of chasmata, chaos, and surface materials in Xanthe, Margaritifer, and Meridiani Terrae, Mars. Icarus 2002, 155, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.; Sasaki, S.; Kuzmin, R.; Dohm, J.; Tanaka, K.; Miyamoto, H.; Kurita, K.; Komatsu, G.; Fairen, A.; Ferris, J. Outflow channel sources, reactivation, and chaos formation, Xanthe Terra, Mars. Icarus 2005, 175, 36–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, N.M. Martian megaflood-triggered chaos formation, revealing groundwater depth, cryosphere thickness, and crustal heat flux. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2005, 110, S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargel, J.S.; Furfaro, R.; Prieto-Ballesteros, O.; Rodriguez, J.A.P.; Montgomery, D.R.; Gillespie, A.R.; Marion, G.M.; Wood, S.E. Martian hydrogeology sustained by thermally insulating gas and salt hydrates. Geology 2007, 35, 975–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrens, C.; Cataldo, V.; Leone, G. Volcanic Eruptions on Mars, Lava Flow Morphology, and Thermodynamics. In Mars: A Volcanic World; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theilig, E.; Greeley, R. Lava flows on Mars: Analysis of small surface features and comparisons with terrestrial analogs. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1986, 91, E193–E206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerekos, C.; Grima, C.; Steinbrügge, G.; Thakur, S.; Scanlan, K.M.; Young, D.A.; Bruzzone, L.; Blankenship, D.D. Martian roughness analogues of Europan terrains for radar sounder investigations. Icarus 2021, 358, 114197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, R.W.; Fink, J.H. The morphology of lava flows in planetary environments: Predictions from analog experiments. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1992, 97, 19739–19748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, T.K.; Fink, J.H.; Griffiths, R.W. Formation of multiple fold generations on lava flow surfaces: Influence of strain rate, cooling rate, and lava composition. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1998, 80, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, A.C.; Preuss, L.J. On the origin of south polar folds on Enceladus. Icarus 2010, 208, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, J.H.; Fletcher, R.C. Ropy pahoehoe: Surface folding of a viscous fluid. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1978, 4, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbelman, J.R. Emplacement of long lava flows on planetary surfaces. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1998, 103, 27503–27516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twidale, C.R.; Bourne, J.A. Fractures as planes of dislocation and two-way translocation: Their significance in landform development. Phys. Geogr. 2007, 28, 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasckert, J.H.; Hiesinger, H.; Reiss, D. Rheologies and ages of lava flows on Elysium Mons, Mars. Icarus 2012, 219, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plescia, J.B. Recent flood lavas in the Elysium region of Mars. Icarus 1990, 88, 465–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloga, S.M.; Mouginis-Mark, P.J.; Glaze, L.S. Rheology of a long lava flow at Pavonis Mons, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2003, 108, 5066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, D.M.; Fassett, C.I.; Head, J.W.; Wilson, L. Formation of an eroded lava channel within an Elysium Planitia impact crater: Distinguishing between a mechanical and thermal origin. Icarus 2010, 210, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukkonen, S.; Kostama, V.P. Modification history of the Harmakhis Vallis outflow channel, Mars, based on CTX-scale photogeologic mapping and crater count dating. Icarus 2018, 299, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viviano, C.E.; Murchie, S.L.; Daubar, I.J.; Morgan, M.F.; Seelos, F.P.; Plescia, J.B. Composition of Amazonian volcanic materials in Tharsis and Elysium, Mars, from MRO/CRISM reflectance spectra. Icarus 2019, 328, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelkey, S.M.; Mustard, J.F.; Murchie, S.; Clancy, R.T.; Wolff, M.; Smith, M.; Milliken, R.; Bibring, J.; Gendrin, A.; Poulet, F.; et al. CRISM multispectral summary products: Parameterizing mineral diversity on Mars from reflectance. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2007, 112, S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, J. Surface folding and viscosity of rhyolite flows. Geology 1980, 8, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollkind, D.J.; Alexander, J.I.D. A Newtonian fluid model of the onset of plane folding in a single rock layer with surface tension effects. Math. Model. 1981, 2, 319–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.W.; Fink, J.H. Crease structures: Indicators of emplacement rates and surface stress regimes of lava flows. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1992, 104, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, R.W. The dynamics of lava flows. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2000, 32, 477–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeley, R.; Foing, B.H.; McSween, H.Y., Jr.; Neukum, G.; Pinet, P.; van Kan, M.; Werner, S.C.; Williams, D.A.; Zegers, T.E. Fluid lava flows in Gusev crater, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2005, 110, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevrel, M.O.; Baratoux, D.; Hess, K.U.; Dingwell, D.B. Viscous flow behavior of tholeiitic and alkaline Fe-rich martian basalts. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2014, 124, 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, N.H.; Gregg, T.K. Evolved lavas on Mars? Observations from southwest Arsia mons and Sabancaya volcano, Peru. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2003, 108, 5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basilevskaya, E.A.; Neukum, G.; HRSC Co-Investigator Team. The Olympus volcano on Mars: Geometry and characteristics of lava flows. Sol. Syst. Res. 2006, 40, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiriet, M.; Michaut, C.; Breuer, D.; Plesa, A.C. Hemispheric dichotomy in lithosphere thickness on Mars caused by differences in crustal structure and composition. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2018, 123, 823–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.I.; Christensen, P.R.; Clarke, A.B. Lava flow eruption conditions in the Tharsis volcanic province on Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2021, 126, e2020JE006791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, M.E.; Rowland, S.K.; Mouginis-Mark, P.J.; Garbeil, H. Thick lava flows of Karisimbi Volcano, Rwanda: Insights from SIR-C interferometric topography. Bull. Volcanol. 1998, 60, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauber, E.; Brož, P.; Jagert, F.; Jodłowski, P.; Platz, T. Very recent and wide-spread basaltic volcanism on Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauer, M.; Breuer, D. Constraints on the maximum crustal density from gravity–topography modeling: Applications to the southern highlands of Mars. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2008, 276, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnas, J.; Mustard, J.; Lollar, B.S.; Stamenković, V.; Cannon, K.; Lorand, J.-P.; Onstott, T.; Michalski, J.; Warr, O.; Palumbo, A.; et al. Earth-like habitable environments in the subsurface of Mars. Astrobiology 2021, 21, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, P.J.; Solomon, S.C. State of stress, faulting, and eruption characteristics of large volcanoes on Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 1993, 98, 23553–23579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, K.E.N.; Kauahikaua, J.I.M.; Denlinger, R.; Mackay, K. Emplacement and inflation of pahoehoe sheet flows: Observations and measurements of active lava flows on Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1994, 106, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, G.B.M.; Head III, J.W. Chaos formation by sublimation of volatile-rich substrate: Evidence from Galaxias Chaos, Mars. Icarus 2011, 211, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerber, L.; Head, J.W.; Madeleine, J.-B.; Forget, F.; Wilson, L. The dispersal of pyroclasts from Apollinaris Patera, Mars: Implications for the origin of the Medusae Fossae Formation. Icarus 2011, 216, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, N.P.; Ahrens, C.; Farrell, A.K. The Origin and Evolution of Volcanism at Martian Highland Paterae: A Review of the Current State of Knowledge. In Mars: A Volcanic World; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 231–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, B. Geodynamics and tectonic stress model for the Zagros fold–thrust belt and classification of tectonic stress regimes. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 155, 106340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehn, D.; Lindenfeld, M.; Rümpker, G.; Aanyu, K.; Haines, S.; Passchier, C.W.; Sachau, T. Active transsection faults in rift transfer zones: Evidence for complex stress fields and implications for crustal fragmentation processes in the western branch of the East African Rift. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2010, 99, 1633–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleacher, J.E.; Greeley, R.; Williams, D.A.; Werner, S.C.; Hauber, E.; Neukum, G. Olympus Mons, Mars: Inferred changes in late Amazonian aged effusive activity from lava flow mapping of Mars Express High Resolution Stereo Camera data. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2007, 112, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, D.G.; Moitra, P.; Hamilton, C.W.; Craddock, R.A.; Andrews-Hanna, J.C. Evidence for geologically recent explosive volcanism in Elysium Planitia, Mars. Icarus 2021, 365, 114499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetterlein, J.; Roberts, G.P. Postdating of flow in Athabasca Valles by faulting of the Cerberus Fossae, Elysium Planitia, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2009, 114, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.L.; Skinner, J.A., Jr.; Dohm, J.M.; Irwin, R.P.; Kolb, E.J.; Fortezzo, C.M.; Platz, T.; Michael, G.G.; Hare, T.M. Geologic Map of Mars; USGS: Reston, VA, USA, 2014.

- Andrews, G.D.; Kenderes, S.M.; Whittington, A.G.; Isom, S.L.; Brown, S.R.; Pettus, H.D.; Cole, B.G.; Gokey, K.J. The fold illusion: The origins and implications of ogives on silicic lavas. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2021, 553, 116643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaze, L.S.; Baloga, S.M. Dimensions of Pu’u O’o lava flows on Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 1998, 103, 13659–13666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaze, L.S.; Baloga, S.M. Rheologic inferences from the levees of lava flows on Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2006, 111, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, D.M.; Grier, J.A.; McEwen, A.S.; Keszthelyi, L.P. Repeated aqueous flooding from the Cerberus Fossae: Evidence for very recently extant, deep groundwater on Mars. Icarus 2002, 159, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, J.W.; Wilson, L.; Mitchell, K.L. Generation of recent massive water floods at Cerberus Fossae, Mars by dike emplacement, cryospheric cracking, and confined aquifer groundwater release. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site | Latitude (°N) | Longitude (°E) | Average Wavelength [km] |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2.22 | 178.69 | 0.75 |

| B | 2.124 | 178.37 | 1.2 |

| C | 1.73 | 177.80 | 1.39 |

| D | 1.716 | 177.46 | 1.5 |

| E | 1.6 | 177.226 | 1.14 |

| F | 1.606 | 176.39 | 1.32 |

| G | 1.312 | 176.36 | 1.38 |

| H | 1.004 | 176.498 | 1.03 |

| I | 1.032 | 176.968 | 1.13 |

| J | 0.672 | 176.54 | 1.2 |

| K | 0.087 | 175.911 | 1.22 |

| L | −0.2887 | 175.732 | 0.71 |

| M | −0.697 | 175.94 | 0.84 |

| N | −0.258 | 175.38 | 0.97 |

| O | −1.261 | 174.64 | 1.6 |

| P | −1.368 | 173.211 | 1.75 |

| Q | −2.293 | 173.046 | 1.63 |

| R | −2.238 | 173.606 | 1.1 |

| S | −3.013 | 172.939 | 0.72 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahrens, C.; Slank, R.A. Morphometric Analysis and Emplacement Dynamics of Folded Terrains at Avernus Colles, Mars. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3946. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243946

Ahrens C, Slank RA. Morphometric Analysis and Emplacement Dynamics of Folded Terrains at Avernus Colles, Mars. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):3946. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243946

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhrens, Caitlin, and Rachel A. Slank. 2025. "Morphometric Analysis and Emplacement Dynamics of Folded Terrains at Avernus Colles, Mars" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 3946. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243946

APA StyleAhrens, C., & Slank, R. A. (2025). Morphometric Analysis and Emplacement Dynamics of Folded Terrains at Avernus Colles, Mars. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 3946. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17243946