Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Proposed a zoning strategy based on the KNN-Ward method, enabling fine-scale delineation of the phenology spatial pattern of winter wheat.

- Developed yield estimation models based on phenological zoning, which achieved higher accuracy and lower error variability within each zone.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The phenology-zoning-based winter wheat yield estimation modeling strategy demonstrates superior performance compared to models based on non-zoning, traditional agricultural zoning, and provincial administrative zoning, exhibiting enhanced robustness and broader applicability.

- This study provided a new methodology and reference for high-precision monitoring of winter wheat yield the regional scale.

Abstract

Phenology is a key factor influencing the accuracy of regional-scale winter wheat-yield estimation. This study proposes a yield-estimation modeling framework centered on phenological zoning. Based on the remote sensing monitoring results of the heading stage of winter wheat in the Huang-Huai-Hai region from 2016 to 2021, the KNN-Ward spatial constraint clustering method was adopted to divide the Huang-Huai-Hai region into four consecutive wheat phenological zones. The results indicate a consistent spatio-temporal gradient in the phenology of winter wheat across the Huang-Huai-Hai region, characterized by later development in the northern areas and earlier development in the southern areas. The median day of year (DOY) for the heading stage in each zone varies by approximately 4 to 5 days, demonstrating a high degree of interannual stability. Building upon the phenological zoning outcomes, a multi-source data-driven random forest model was developed for wheat-yield estimation by integrating remote sensing data and meteorological variables during the wheat grain filling stage. This model incorporates remote sensing vegetation indices, crop growth parameters, and climatic factors as key input variables. Results show that the phenological zoning strategy significantly improves model prediction performance. Compared with the non-zoning model (R2 = 0.46, RRMSE = 13.02%), the phenological zone model shows strong performance under leave-one-year-out cross-validation, with R2 ranging from 0.54 to 0.68 and RRMSE below 12.50%. The phenological zoning model also exhibits more uniform residuals and higher prediction stability than models based on non-zoning, traditional agricultural zoning, and provincial administrative zoning. These results confirm the effectiveness of phenology-based zoning for regional yield estimation and provide a reliable framework for fine-scale crop yield monitoring. The phenological zoning model also demonstrates superior residual uniformity and prediction stability compared with models based on non-zoning, traditional agricultural zoning, and provincial administrative zoning. These results confirm the effectiveness of the multi-factor-driven modeling framework based on crop phenological zoning for regional yield estimation, providing a robust methodological foundation for fine-scale yield monitoring at the regional level.

1. Introduction

According to the FAO (2024), winter wheat, a crucial food crop globally, is grown on around 224 million hectares, accounting for 29% of worldwide grain production [1]. It commands about 50% of the international cereal trade, underscoring its pivotal role in the global food economy [2,3]. Wheat is essential for national food security, fostering sustainable agricultural development, and preserving social stability [4,5,6]. As a principal region for winter wheat cultivation, the Huang-Huai-Hai area of China is characterized by extensive and diverse wheat-growing systems and contributes over 70% of the nation’s total winter wheat production each year, playing a vital role in ensuring food security [7,8]. It has been demonstrated that crop growth processes are influenced by the interaction of environmental factors such as climate, soil, and phenological processes, and that crop responses to environmental factors vary not only regionally but also with phenological periods. So it is difficult to accurately estimate large-scale yields due to the region’s significant spatial and temporal heterogeneity of crop growth, the frequency of extreme weather events, and the significant climatic variations [9,10]. The growth process of winter wheat from heading to maturity in different geographical units shows a gradient difference of 5 to 15 days at different growth stages [11]. Meanwhile, the contribution of environmental factors was spatially dependent, e.g., winter wheat yield in Denmark was highly sensitive to high summer temperatures (p < 0.01) [12]. In contrast, the main production areas in China were subjected to water stress at the winter wheat heading stage [13]. This relationship showed significant spatial heterogeneity and nonlinearity at the regional scale. Therefore, examining the regional heterogeneity of crop growth and its influencing factors is of critical importance for accurate crop-yield estimation and effective growth management.

Developing high-accuracy and generalizable regional-scale crop-yield prediction models is of great significance for optimizing agricultural resource allocation, ensuring national food security, and facilitating strategic grain planning [14]. Remote sensing technology, characterized by its rapid, large-scale, dynamic, and non-invasive capabilities in acquiring surface information, has emerged as an important tool for monitoring crop growth and estimating yield [15]. Vegetation indices derived from remote sensing imagery provide a direct assessment of crop growth conditions and serve as a reliable data source for crop-yield estimation on a large scale. Typical remote sensing-based approaches for crop-yield estimation can be broadly classified into several categories, including statistical correlation models linking yield with spectral indices, yield potential–stress factor models, yield three-component models, and crop biomass–yield models, as summarized by Xu et al. [16]. These variables are often combined with ancillary non-remote sensing data through statistical or process-driven techniques to generate yield estimates. In recent years, the fusion of multi-source remote sensing and meteorological data, along with advancements in machine learning algorithms, has significantly enhanced the accuracy of crop-yield estimation at regional scales [17,18]. Machine learning models, including Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Machine (SVM), have been extensively utilized for yield estimation across various regions and crops. This widespread adoption is attributed to their capacity to process high-dimensional nonlinear data, their independence from assumptions regarding the distribution of input variables, and their robustness against overfitting [19,20,21]. Satellite remote sensing time-series imagery offers comprehensive insights into crop growth patterns, capturing systematic variations caused by phenological differences as well as random variations resulting from agricultural management practices, such as fertilization and irrigation. Conventional crop-yield estimation models frequently neglect phenological heterogeneity, potentially compromising model accuracy and robustness [22,23,24]. For instance, studies on crop-yield estimation in the Yellow River Delta region of China have demonstrated that overlooking phenological variations can elevate the root mean square error (RMSE) of yield predictions to 1.02 t/ha [25].

In recent years, increasing attention has been devoted to explicitly integrating crop phenology into yield-estimation frameworks. Various approaches have been developed, ranging from the assimilation of remotely sensed phenological stages into process-based models to the use of stage-specific vegetation indices and the alignment of time-series data based on key phenological markers. For example, Tang et al. incorporated satellite-derived sowing, heading, and maturity stages into the Wheat Grow model to improve dynamic yield simulations [26]; Shrestha et al. identified the tasseling stage as a critical period for maize-yield prediction, revealing that chlorophyll-sensitive indices exhibit the strongest correlations with yield during this phase [27]; and Zhang et al. proposed a phenology-alignment strategy by synchronizing multi-source time-series data using field-level phenological peaks, which significantly enhanced the performance of deep learning yield models under extreme drought conditions [28]. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that accurate phenological characterization is fundamental for improving the temporal realism and predictive reliability of yield models. However, most existing studies treat phenology as an auxiliary temporal predictor rather than as a spatially explicit modeling basis. This study extends the use of phenological information by constructing phenology-based zoning units that capture both spatial and temporal variations in crop development, thereby providing a new framework for improving model generalization across heterogeneous agro-ecological regions. Zone-based modeling approaches have increasingly become a prominent strategy for regional crop-yield estimation. Traditional agricultural zoning methods were largely based on expert knowledge and climatic parameters such as isohyets. For example, agricultural zones were often defined using visual differences in Landsat imagery or through temperature and precipitation indicators, upon which empirical yield models were subsequently developed [29,30]. However, traditional zoning approaches often rely heavily on subjective expert experience, have limited spatial resolution, and rarely incorporate crop phenological dynamics. As a result, they may produce zones that do not fully reflect the temporal variability of crop growth, leading to estimation uncertainties. To overcome these limitations, several studies have introduced remote sensing time-series data (e.g., NDVI, EVI) into clustering analyses. By using methods such as spectral angle clustering (SAC), these studies dynamically delineated zones based on phenological trajectories, thereby improving both the accuracy and the interpretability of the zoning process [31].

To address the issue of insufficient consideration of phenological heterogeneity in current winter wheat-yield estimation, this study proposes a framework for constructing a remote sensing and climate multi-factor driven model for winter wheat-yield estimation based on phenological zoning. The study first employs time-series remote sensing data to extract the winter wheat heading stages in the Huang-Huai-Hai region. Subsequently, the Dynamic K-Nearest Neighbors-Ward (KNN-Ward) spatial clustering algorithm is applied to derive phenological zones with high internal consistency within the study area. Based on this foundation, a Bayesian-optimized random forest model was constructed to estimate regional winter wheat-yields, incorporating crop vegetation indices, growth parameters, and meteorological data relevant to yield formation during the winter wheat growth period. The study conducted comparative analyses of the accuracy and robustness of yield-estimation models using traditional administrative and agricultural zoning systems, aiming to evaluate the role of phenological zoning in enhancing the adaptability of regional yield-estimation models.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of Research Area

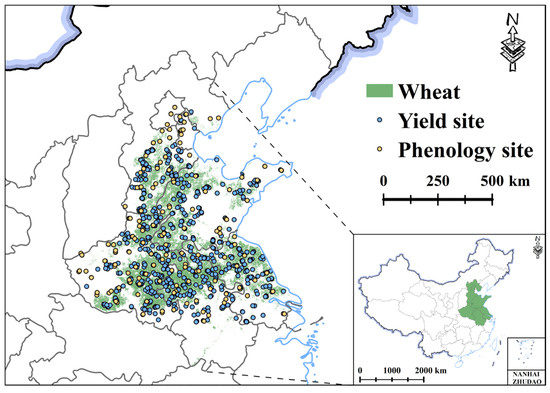

This study focuses on the Huang-Huai-Hai region of China (Figure 1), which is located in a warm-temperate, semi-humid to semi-arid continental monsoon climate zone and covers approximately 590,200 km2, encompassing Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Henan, Shandong, Jiangsu, and Anhui provinces. The region is characterized by cold, dry winters and hot, rainy summers, with a mean annual temperature of about 15 °C and annual precipitation ranging from 600 mm to 900 mm. January, the coldest month, averages between −5 °C and −1 °C, while July and August typically range from 26 °C to 32 °C. Winter wheat is generally sown in October of the previous year and harvested around June of the following year. During winter, low temperatures promote vernalization and tillering, while warm and humid spring conditions support vigorous jointing and heading growth. Moderately elevated summer temperatures facilitate grain maturation, although excessive heat may reduce grain filling and quality. Across the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain, the heading (or anthesis) period varies by about 20 days from south to north, reflecting the spatial heterogeneity of climatic conditions and management practices. The region’s stable climate, extensive cropland, and high productivity make it one of China’s most important winter wheat-producing areas, playing a vital role in ensuring national food security.

Figure 1.

Location of the experimental area in this study.

2.2. Data Acquisition

2.2.1. Remote Sensing Data

In this study, the MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) imagery acquired at 8-day intervals during the winter wheat growth period in the Huang-Huai-Hai region between 2016 and 2021 was utilized. The satellite data were accessed via the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform, which serves as a cloud-based platform providing access to and processing of multi-source remote sensing datasets. The MODIS products offer high temporal resolution (8-day composites) and moderate spatial resolution (500 m), which makes them well-suited for large-scale crop growth monitoring and the analysis of dynamic changes over time. Based on the MOD09A1 product, five vegetation indices were calculated and used for subsequent data analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Vegetation index table.

The Leaf Area Index (LAI) and the Fraction of Absorbed Photosynthetically Active Radiation (FPAR) are two essential plant biophysical parameters that describe canopy structure and the rates of associated energy exchange processes. In this study, MODIS MOD15A2 data covering the winter wheat growth period in the Huang-Huai-Hai region from 2016 to 2021 were acquired from the NASA Earth data website (https://ladsweb.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov/, accessed on 4 January 2025). This dataset provides 8-day composite Level-4 products of LAI and FPAR at a spatial resolution of 500 m [37].

Solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF) is a rapidly developing vegetation remote sensing technology that has emerged over the past decade. It addresses the limitations of traditional optical remote sensing methods that rely on vegetation indices such as “greenness”, thereby offering essential technical support for studies focused on the retrieval of physiological and biochemical parameters and productivity of terrestrial ecosystems, the early detection of abiotic stress, the extraction of photosynthetic phenology, and the monitoring of vegetation transpiration [38]. In this study, the Global OCO-2 Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence (GOSIF) dataset, which also includes gross primary productivity (GPP) data, was utilized in winter wheat-yield estimation modeling. The dataset provides global, continuous 8-day temporal resolution SIF and GPP data at a spatial resolution of 0.05° over the period 2000–2024, derived using the algorithm proposed by Li and Xiao (2019) [39,40]. All data are publicly accessible on the website at http://globalecology.unh.edu/data/GOSIF.html (accessed on 4 January 2025).

To ensure spatial and temporal consistency among multi-source datasets, all data (including MODIS, LAI/FPAR, GOSIF/GPP) were harmonized to an 8-day temporal resolution and a 500 m spatial grid in this study.

2.2.2. ERA5-Land Data

The ECMWF Reanalysis v5 (ERA5) is the fifth-generation global climate and weather reanalysis product developed by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). The ERA5-Land dataset has a spatial resolution of 11.1 km (0.1°) and can be accessed by registering and downloading directly from the Climate Data Store (CDS) of the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) or via the CDS API. In this study, the meteorological variables considered included daily maximum temperature (tmmx), minimum temperature (tmmn), precipitation (pr), 10 m wind speed (vs), and soil moisture (soil), all derived from the ERA5 climate data [41]. The ERA5-Land meteorological variables were resampled to 500 m spatial resolution using the bilinear interpolation method.

2.2.3. Winter Wheat Distribution Maps

In this study, winter wheat planting area data from 2016 to 2021 were obtained from the winter wheat identification dataset provided by the National Ecological Science Data Center (https://www.nesdc.org.cn/, accessed on 4 January 2025).

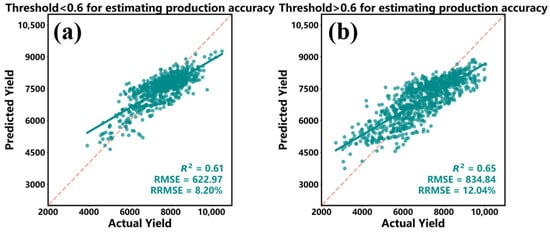

The wheat distribution map was first binarized at a 30 m resolution, where pixel values of 1 and 0 represent wheat-growing and non-wheat-growing areas, respectively. To match the spatial resolution of other datasets, the binary map was resampled from 30 m to 500 m using the minimum pooling method [42,43]. A 500 m pixel containing any non-wheat (0) value was identified as a mixed pixel. To ensure reliable yield estimation, pixels with a fractional wheat coverage above 0.6 were classified as wheat-dominant pixels. We further analyzed the residual differences in yield estimation between pixels with coverage fractions above and below this 0.6 threshold (Appendix A.1).

2.2.4. Ground Observation Data

The wheat yield data in this study were collected manually during the winter wheat maturity periods from 2016 to 2021. Yield surveys were conducted across multiple winter wheat fields in six provincial-level administrative regions, including Beijing Municipality and the provinces of Shandong, Henan, Hebei, Anhui, and Jiangsu (Figure 1). For each field, the five-point sampling method was employed, with five representative wheat sample plots (1 m2 each) selected for harvest and yield measurement. The harvested wheat spikes were threshed, dehulled, air-dried, and subsequently measured for grain weight and moisture content. Final yields were standardized to a moisture content of 14% and expressed in units of kg/hm2. A total of 1814 yield observations were collected over the six-year period. These measured wheat-yield data served as the foundation for developing and validating the wheat-yield estimation model, thereby ensuring the accuracy and regional representativeness of the study.

The phenological data used in this study were collected from field surveys carried out at phenology observation stations under the administration of the China Meteorological Administration, spanning the period from 2016 to 2021. For each observation station, the dataset contains geographic coordinates (latitude and longitude) along with key phenological information of the crops. The variable DOY represents the Day of Year, which is calculated using the following equation:

D: the day of the current month (1–31), M: the current month (1–12),: the total number of days in the i-th month.

For a common year: T = {31,28,31,30,31,30,31,31,30,31,30,31};

For a leap year: T = {31,29,31,30,31,30,31,31,30,31,30,31}.

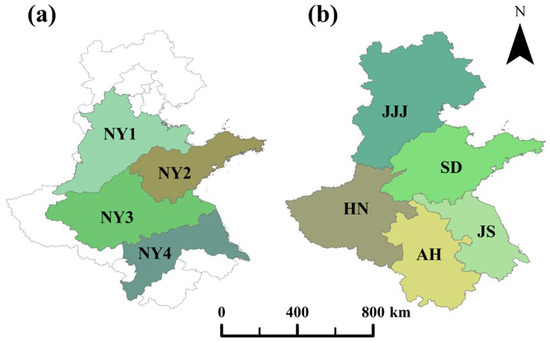

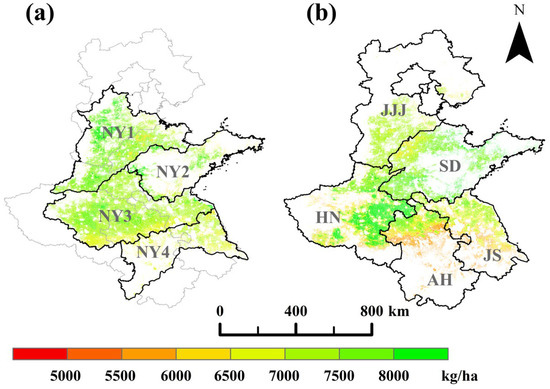

2.2.5. Agricultural Resource and Environment Zoning Data

This study evaluated and compared the accuracy of winter wheat-yield estimation models based on three different zoning approaches: the phenological zoning proposed in this research, the traditional Chinese agricultural resource and environmental zoning, and the provincial administrative zoning. The wheat planting regionalization data is from the Dataset of Agricultural Resource and Environment Zoning of China [44]. This dataset classifies specific geographical units of China’s land into distinct agricultural resource and environmental zones, based on regional characteristics of agricultural production, resource suitability, and environmental challenges. This study primarily focuses on the winter wheat-producing regions of the Huang-Huai-Hai region, selecting the following zones for comparative experiments: NY1: North China Plain Zone; NY2: Shandong Hilly Zone; NY3: Huang-Huai-Hai Plain Zone; and NY4: Jianghuai Region (Figure 2a). Provincial administrative zoning is based on the current administrative boundaries of the provinces in the Huang-Huai-Hai region (Figure 2b), including JJJ: Beijing, Tianjin, and Hebei Province; SD: Shandong Province; HN: Henan Province; AH: Anhui Province; and JS: Jiangsu Province.

Figure 2.

Agricultural resource and environmental zoning (a) and provincial administrative divisions (b).

2.3. Data Analysis Methods

2.3.1. Winter Wheat Heading Stage Identification

The heading stage is a crucial phase in which wheat transitions from vegetative to reproductive growth. This stage directly influences subsequent processes such as flowering, grain filling, and maturation, and plays a key role in predicting the timing of crop maturity [45]. During this stage, notable changes occur in the structure of wheat leaves and spikes, leading to increased chlorophyll absorption and light scattering, particularly manifesting as a significant rise in near-infrared reflectance. Field vegetation coverage reaches its maximum during the heading stage, and vegetation indices such as NDVI and EVI2 typically attain their peak values at this time. Consequently, the maximum vegetation index method is widely employed for monitoring the wheat heading stage [46].

In this study, MOD09A1 imagery from the GEE platform was used for phenology extraction. The time range was restricted to October 1 of the previous year to June 30 of the current year. Cloud and shadow masking were conducted using the StateQA band from MOD09A1 via bit extraction, and atmospheric correction was applied. Missing or cloud-contaminated pixels were filled using temporal interpolation. The EVI2 index was then calculated, missing values were interpolated, and the resulting time series were smoothed using the Savitzky–Golay (SG) filter to reduce atmospheric noise and residual cloud effects. Based on previous studies on winter wheat phenology extraction [47,48], the SG filter was implemented with a three-observation window (approximately 24 days) and a third-order polynomial. To account for regional variations in phenological responses, a curve-stretching method was applied to align local EVI2 maxima and minima with the regional mean curve. This normalization adjusted amplitude and temporal scale without altering the relative peak position of local curves, thereby improving the robustness and spatial consistency of heading-stage detection [49].

Note: NIR and R bands represent near-infrared and red bands, respectively.

2.3.2. Phenological Zoning Method

- (1)

- Dynamic K-Nearest Neighbors

To appropriately characterize the spatial autocorrelation of the DOY values at the heading stage, this study employed the Dynamic K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithm to construct a spatial weight matrix [50]. Through an adaptive neighborhood selection mechanism, the KNN algorithm effectively achieves a balance between capturing local details in small-sample scenarios and suppressing noise in large-scale contexts, thereby ensuring a robust and computationally efficient representation of the spatial dependency of heading stage DOY values [51].Specifically, the Euclidean distance between units was first calculated based on the heading stage DOY values and spatial coordinates within the study area’s geographic units (Equation (3)). Subsequently, the number of neighbors K was determined using the dynamic KNN algorithm (Equation (4)), where the constant 6 represents an empirical value commonly used in spatial statistics and KNN classification to balance capturing local spatial dependencies with maintaining statistical stability [52]. This process constructed a binary adjacency matrix (Equation (5)). Finally, the adjacency matrix is normalized to eliminate density biases across units, yielding the standardized weight matrix (Equation (6)). The resulting weight matrix quantifies the spatial co-variation of DOY values among adjacent units, providing geographic constraints for subsequent clustering. The relevant equations are shown as follows.

is the Euclidean distance between units and used to measure geographical proximity and are the latitude and longitude coordinates of unit ;

k is the dynamic domain size, adaptively adjusted to accommodate data of different scales; N is the number of valid observation points remaining after dynamic grid sampling;

- (2)

- Improving the Ward hierarchical clustering algorithm

Based on the spatial weight matrix , this study proposes an improved Ward hierarchical clustering algorithm that simultaneously minimizes within-cluster DOY heterogeneity while enforcing spatial contiguity, thereby preventing the formation of “disconnected” clusters and ensuring that the resulting regions are both feature-homogeneous and geographically continuous. The algorithm employs a bottom-up agglomerative strategy, in which, at each iteration, only geographically adjacent units or clusters with the smallest DOY differences are merged. This approach minimizes within-cluster variance while maintaining the natural continuity of cluster boundaries [53]. The algorithm was defined as follows.

is the variance increment of the two clusters DOY; and represent the sample sizes of clusters a and b, respectively; and represent the average DOY values of clusters a and b, respectively; is the average DOY value after the two clusters are merged.

By incorporating the aforementioned spatial constraints and optimization criteria into the clustering process, this method ensures that the resulting clusters of heading stage DOY values are both temporally coherent and geographically contiguous, thereby delineating phenological distinct regions. This approach establishes a robust foundation for further analyses of regional variability and for optimizing model zoning configurations.

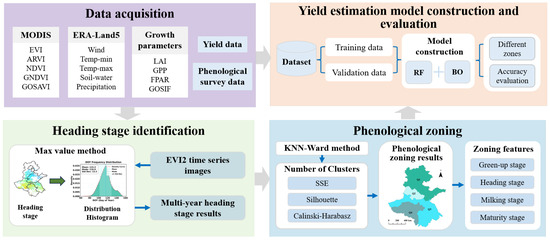

2.3.3. Yield-Estimation Model Construction Method

This study utilizes data from the wheat grain-filling stage to construct and validate the yield-estimation model based on phenological zoning. Figure 3 illustrates the overall technical route research in this study. The yield model is developed through the integration of RF and Bayesian Optimization (BO) algorithms. RF is an ensemble learning method that generates multiple decision trees applied to training samples. Among existing algorithms, RF is recognized for its high accuracy and stability, and it can effectively handle large datasets with high-dimensional features [54]. It also exhibits strong robustness to noise, rendering it particularly suitable for crop-yield modeling scenarios characterized by nonlinear relationships among variables [55]. However, the performance of RF models is highly dependent on the proper tuning of key hyperparameters, including the number of trees, maximum depth, and minimum sample split. To address the limitations of traditional parameter tuning methods, such as grid search and random search, this study employs Bayesian Optimization to automate the hyperparameter tuning of the RF model. Bayesian Optimization constructs a surrogate model of the parameter space—here using the Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) sampler—and iteratively selects promising parameter combinations based on the current posterior distribution, with the objective of minimizing validation RMSE and applying over- and under-fitting penalties [56]. Various RF hyperparameters (e.g., number of trees, maximum depth) were explored during the search, and the complete search space, iteration budget, and implementation details are provided in the Table A1. Hyperparameter optimization and model evaluation were conducted using a temporal cross-validation scheme, in which each year from 2016 to 2021 was used once as the validation fold while the remaining years served as the training set (leave-one-year-out), ensuring temporal independence during tuning.

Figure 3.

Technical flowchart.

2.4. Accuracy Evaluation Methods

2.4.1. Determining the Number of Clusters

To determine the optimal number of clusters, the range of cluster numbers (M) was set from 2 to 7. The Silhouette Coefficient, Calinski–Harabasz Index, and the corresponding sum of squared errors (SSEs) based on the elbow method were calculated to comprehensively evaluate the compactness and separability of the clustering results, thereby enabling the selection of the optimal cluster count. The silhouette coefficient is a metric that assesses the consistency of similarity among samples within clusters (Equation (9)). It is commonly employed to evaluate both the compactness of individual samples within their respective cluster and their degree of separation from the nearest neighboring cluster [57]. The coefficient is formally defined as [58]:

denotes the silhouette coefficient of sample ; is the average distance from sample to all other samples within its own cluster; is the average distance from sample to all samples in the nearest neighboring cluster; represents the average silhouette value across all samples.

Calinski–Harabasz (CH) Index (Equation (11)), also referred to as the variance ratio criterion, evaluates the ratio of between-cluster dispersion to within-cluster dispersion. A higher CH value indicates superior clusters and increased compactness within clusters [59]. It is formally defined as [60].

denotes the trace of the between-cluster covariance matrix; denotes the trace of the within-cluster covariance matrix; n is the total number of samples; m is the number of clusters.

The elbow method assesses clustering performance by computing the total within-cluster SSE across varying numbers of clusters. While the SSE decreases progressively as the number of clusters (M) increases, the rate of reduction eventually diminishes significantly, resulting in an “elbow” shape in the plotted curve. The value of M at this inflection point is commonly selected as the optimal number of clusters [61]. This method is mathematically defined as Equation (12).

where is the set of all data points in the i-th cluster; is the centroid of the i-th cluster; is the Euclidean distance from data point x to the centroid.

2.4.2. Accuracy Assessment of Yield-Estimation Model

This study employed a leave-one-year-out (LOYO) cross-validation approach, in which the models were trained on data from all years except one and subsequently validated on the excluded year in an iterative manner. Model performance, with respect to generalization ability and predictive accuracy, was evaluated using three statistical metrics: the coefficient of determination (R2), root mean square error (RMSE), and relative root mean square error (RRMSE) [62,63].

is the i-th predicted value; is the i-th predicted value; is the average of the observed values; n is the number of training samples.

3. Results

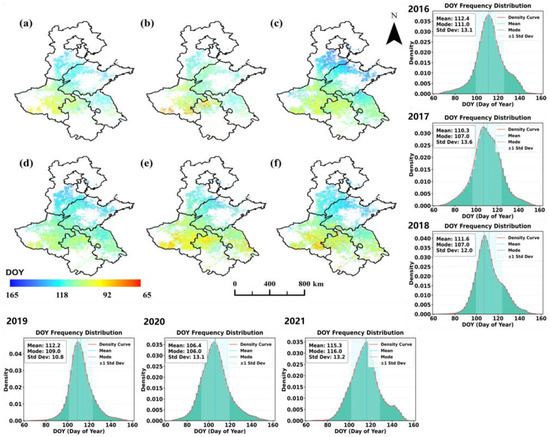

3.1. Wheat Heading Stage Monitoring Results

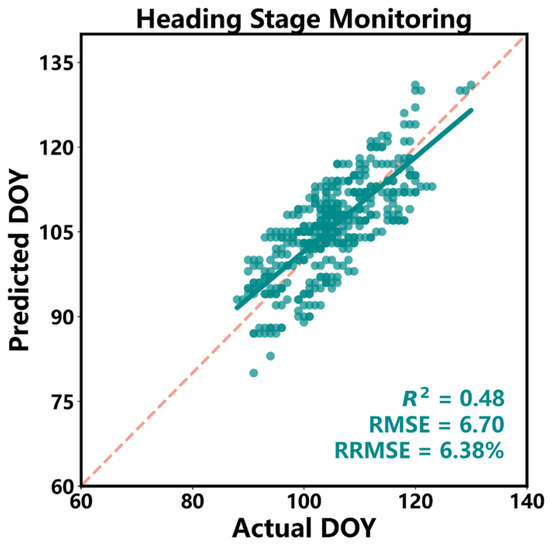

The maximum value method was used to monitor the heading stage of winter wheat in the Huang-Huai-Hai region from 2016 to 2021. Figure 4 presents the monitoring results.

Figure 4.

Winter wheat heading stage results from 2016 to 2021 and the DOY frequency distribution histogram: (a–f) represent the monitoring results from 2016 to 2021, respectively.

The monitoring accuracy of the winter wheat heading stage was evaluated by the ground measurement data from the phenology observation stations in the Huang-Huai-Hai region, with R2 = 0.48 and RMSE = 6.7 days. According to the frequency distribution histogram, the average DOY value for the heading stage of winter wheat in the Huang-Huai-Hai region from 2016 to 2021 ranged between 106.0 and 115.0, with the median ranging from 106.0 to 116.0 and a standard deviation varying between 10.8 and 13.6 days. There were certain differences in the central tendency and dispersion of the heading stage between different years. From the spatial distribution characteristics, it is evident that the DOY values exhibit a ‘north-high, south-low’ gradient pattern, gradually decreasing from north to south. Since higher DOY values correspond to later heading dates, this pattern indicates that the heading stage of winter wheat occurs earlier in the southern regions and later in the northern regions. This spatial gradient in heading timing provides the basis for subsequent phenology-based zoning and yield estimation.

3.2. Phenological Zoning of Winter Wheat Based on the Multi-Year Heading Stage Maps

3.2.1. Zoning Parameters and Cluster Evaluation

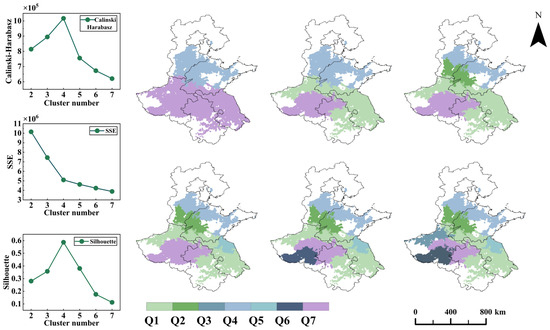

Based on the monitoring results of the heading stage of winter wheat from 2016 to 2021, the KNN-Ward spatial constraint clustering method was used to perform phenological zoning. Cluster numbers ranging from two to seven were tested, and the resulting cluster configurations were comprehensively evaluated to determine the optimal number of clusters. The clustering outcomes for groupings of two to seven clusters are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Clustering zoning results.

As illustrated in Figure 5, when the number of clusters is set to 4, all clustering evaluation metrics demonstrate optimal clustering performance. Specifically, the Silhouette coefficient reaches its maximum value of 0.58; the Calinski–Harabasz index peaks at 1,016,910.85 under the same clustering configuration; and the inflection point identified by the elbow method also occurs at four clusters. Taken together, these three indicators suggest that the clustering results are most effective when the number of clusters equals 4, reflecting the best balance between cluster cohesion and in-cluster separation. Based on this comprehensive evaluation, this study concludes that the study area should be partitioned into four spatially continuous phenological zones (Figure 6a).

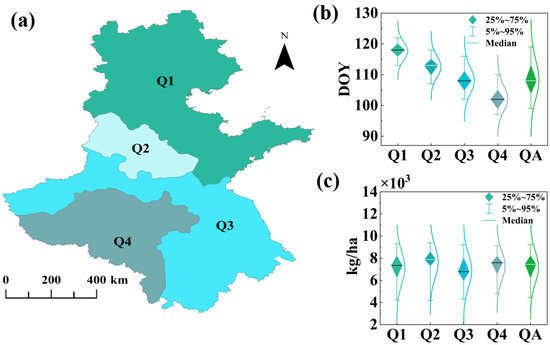

Figure 6.

Phenological zoning results (a) heading stage statistics (b) and yield statistics (c): zoning (Q1–Q4); entire region (QA).

3.2.2. Phenological Zoning Characteristics Analysis

According to the zoning results, the DOY values for the heading period exhibit a significant spatial gradient across different regions. The Q1 region (northern Hebei, Beijing, Tianjin, and northern Shandong) experiences the latest heading period, with a median DOY of approximately 117; the DOY across the entire Q1 region ranges from approximately 114 to 120. The median DOY for the Q2 region (northwestern Shandong, southern Hebei) is approximately 112, while that for the Q3 region (Jiangsu, southwestern Anhui, northwestern Henan, southwestern Shandong) is 108. The Q4 region (central and southern Henan, northern and western Anhui) has the earliest heading period, with a median DOY of approximately 103. The overall median DOY across all regions is 108, with a maximum variation span of nearly 20 days. These differences indicate significant inter-regional variation in the heading period and highlight the evident spatial heterogeneity in phenological processes. Regarding yield, the median across the four regions is approximately 7500 kg/ha, with the Q2 region achieving a maximum of 8000 kg/ha. The primary yield distribution ranges between 4500 and 8500 kg/ha, showing relatively minor inter-regional differences in yield.

In the phenology-based zones, the median green-up dates ranged from 49 to 62 DOY across zones Q4 to Q1, with an overall median of 55 DOY for the entire study area and a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 36–75 DOY. The median milking stage dates across zones Q4 to Q1 ranged from 137 to 148 DOY, with an overall median of 140 DOY for the entire QA area and a 95% CI of 129–155 DOY. The median maturity dates for the same zones ranged from 148 to 161 DOY, with an overall median of 155 DOY for the QA area and a 95% CI of 140–166 DOY. From Zone Q1 to Zone Q4, the green-up stage, milking stage, and maturity stage all showed progressively earlier occurrence, with median values between adjacent zones differing by approximately 4 to 5 days. This observation further supports the applicability of phenological zoning based on the heading stage of winter wheat in the Huang-Huai-Hai region to other developmental stages as well (Table 2).

Table 2.

Statistical results of winter wheat phenological data in different phenology zones.

3.3. Wheat-Yield Estimation Results and Accuracy Verification

This study used wheat-yield data from the Huang-Huai-Hai region spanning the years 2016 to 2020 as the training dataset for the wheat-yield estimation model and employed actual yield data from 2021 for model validation. The five spectral indices—GNDVI, EVI, GOSAVI, ARVI, and NDVI—along with four winter wheat growth parameters—GOSIF, GPP, LAI, and FPAR—and four ERA5 meteorological variables—temperature, precipitation, wind speed, and soil moisture—were used as input variables for winter wheat-yield estimation. All variables were temporally aggregated to an 8-day time scale and spatially resampled to a 500 M resolution to ensure both temporal and spatial consistency, thereby creating a coherent time series dataset. The yield model was estimated based on data focusing on the grain-filling stage of winter wheat. In the Huang-Huai-Hai region, this stage primarily takes place from early May to early June. To investigate the impact of crop phenological differences on yield estimation, we modeled and estimated wheat yields based on phenological zoning and compared the results with those derived from agricultural zoning and administrative zoning.

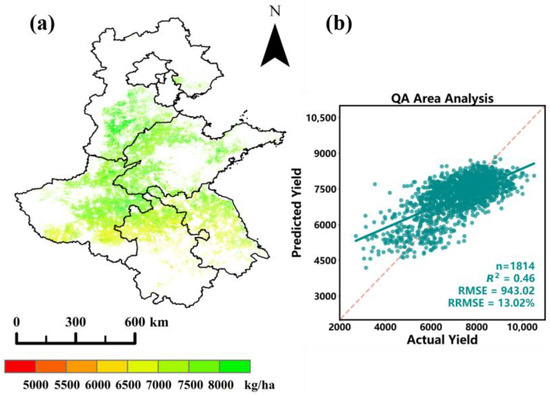

3.3.1. Wheat-Yield Estimation Based on Phenological Zoning

In this study, data collected from the entire Huang-Huai-Hai region during 2016–2021 were used to develop and evaluate the winter wheat-yield estimation model using a LOYO strategy. In this approach, each year from 2016 to 2021 was sequentially used as the validation set, while the remaining five years were used for model training. Figure 7a presents the spatial distribution of estimated yields for 2021 as an example, and Figure 7b shows the overall scatter plot combining cross-validation results from all six years. The model achieved an R2 of 0.46, an RMSE of 943.02 kg/ha, and an RRMSE of 13.02% across the entire region.

Figure 7.

Yield-estimation result based on data from overall region. (a) Spatial yield distribution map; (b) Scatter plot of estimated vs. observed yield.

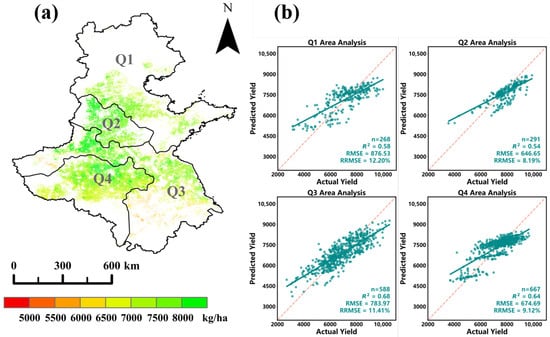

Figure 8 presents the winter wheat-yield estimation results based on four phenology-based zoning models (Q1–Q4). Figure 8a shows the spatial distribution of estimated yields for 2021 as an example, while Figure 8b displays the overall scatter plots combining the cross-validation results from all six years (2016–2021). As illustrated in Figure 8, the modeling accuracy (R2) of the four zonal models exceeded 0.54. Among them, Zone Q3 exhibited the highest accuracy, with an R2 of 0.68 and an RMSE of 783.97 kg/ha. Based on the cross-validation results, the R2 values across the four zones ranged from 0.54 to 0.68. Compared with the non-zonal model for the entire Huang-Huai-Hai region (Figure 7), the phenology-based zoning approach substantially reduced the RRMSE, with all zonal values below 12.50%. These results indicate that the application of phenological zoning effectively improved both the modeling and validation accuracy of winter wheat-yield estimation.

Figure 8.

Yield-estimation result based on data from phenological zoning. (a) Spatial yield distribution map; (b) Scatter plot of estimated vs. observed yield.

Compared with the non-zonal yield-estimation approach, the phenology-based zonal modeling strategy achieved notable improvements, with even the weakest zonal model (Q2) showing a 17.39% increase in cross-validated R2 relative to the non-zonal baseline. Statistical analysis (p < 0.001) further confirmed that phenological zoning significantly improves the model’s stability and generalization capability, demonstrating the feasibility and effectiveness of adopting a phenology-driven zoning approach.

3.3.2. Yield-Estimation Results Based on Other Multi-Zone Schemes

This study also conducted wheat-yield estimation modeling based on the traditional Chinese agricultural resource and environmental zoning, as well as the provincial administrative divisions within the Huang-Huai-Hai region. The results are presented in Figure 9. Specifically, Figure 9a displays the spatial distribution of estimated yields for 2021 based on traditional resource and environmental zoning, while Figure 9b illustrates the 2021 estimation results according to provincial administrative boundaries.

Figure 9.

Yield-estimation results based on agricultural resource and environmental zoning (a) and provincial administrative divisions (b).

Table 3 summarizes the construction and validation accuracy of yield models based on various zonal schemes.

Table 3.

Estimated yield accuracy by agricultural zone and provincial administrative division.

The yield-estimation model based on agricultural resource and environmental zoning exhibited moderate predictive performance, with R2 values ranging from 0.42 to 0.52, RMSE values between 816.78 and 1227.41 kg/ha, and RRMSE values from 12.54% to 16.68%. When the data were aggregated by provincial administrative divisions, the model achieved R2 values of 0.40–0.53, RMSE values of 892.33–1099.55 kg/ha, and RRMSE values of 12.47–14.61%, indicating slightly higher variability in model accuracy across provinces.

4. Discussion

The heading stage of winter wheat is a critical transition point between vegetative growth and reproductive growth, directly influencing the subsequent grain formation and grain filling accumulation rate, thereby significantly impacting the wheat final yield [44]. The grain filling stage involves a gradual accumulation of grain biomass, during which remote sensing signals change relatively smoothly, and the maturity stage signifies the conclusion of the crop’s life cycle, marked by a significant decline in remote sensing signals. This stage reflects more the final-yield outcomes than the dynamic growth process, and thus is less effective in capturing variations in crop development patterns or management practices [64,65]. This study utilizes the heading stage as the basis for phenological zoning and establishes yield-estimation models for each zone. The developed models effectively capture the spatial characteristics of yield-influencing factors during critical physiological stages of wheat within each zone, thereby significantly enhancing estimation accuracy and model generalization capability [66].

4.1. Wheat Heading Stage Monitoring

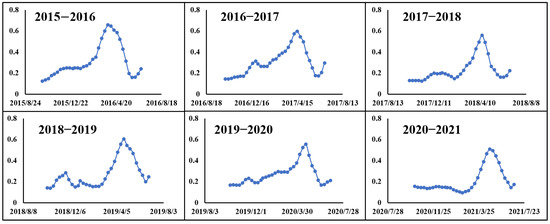

The heading stage is primarily regulated by external environmental factors such as temperature, light, and moisture, exhibiting strong regional specificity and ecological response sensitivity [67]. Several years of EVI2 time-series data were examined and found that double-peak patterns occasionally occurred under extreme weather or stress conditions (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

EVI2 time-series data.

In this study, a first-order differential method was applied to identify and exclude abnormal peaks, retaining only those with values greater than 0.45 and within the DOY range of 70–170 [68]. In this study, the regional curve-stretching procedure was applied solely for amplitude and temporal normalization, without altering the relative peak positions of the local EVI2 curves [49]. The station-by-station residual map and representative site stability tests further confirm the reasonableness of the results (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Accuracy of heading stage monitoring.

4.2. Phenological Zoning Based on KNN-Ward Spatial Constraint Clustering

With the rapid advancement of clustering algorithm-based zoning methods, algorithms such as K-means and CAST have exhibited notable performance improvements in terms of zoning significance, spatial consistency, and model prediction accuracy [69]. Research has indicated that intelligent zoning not only facilitates more accurate delineation of fertility variation zones but also enhances the stability and generalization ability of regional models, thereby emerging as a key developmental direction in current yield-estimation modeling [70].

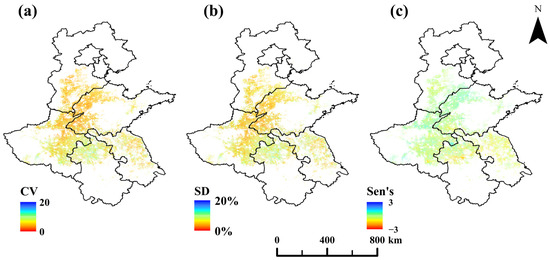

To characterize the interannual variability and temporal trends of the winter wheat heading stage from 2016 to 2021, we employed the coefficient of variation (CV), standard deviation (SD), and Sen’s slope for analysis. The results (Figure 12) indicated that the mean CV across the Huang-Huai-Hai region was 5.98%, with an average SD of 6.39 days. Both the mean and median Sen’s slope values were −0.5, suggesting a slight advancing trend of approximately 0.5 days per year. Overall, the spatial distribution of the heading stage remained stable across the study period, with only minor interannual fluctuations observed in localized areas and a high degree of temporal consistency.

Figure 12.

Fluctuation and trend analysis of heading stage results: CV (a); SD (b); Sen’s slope (c).

This study applied the KNN-Ward spatially constrained clustering method, which effectively combines phenological similarity with spatial adjacency, thereby enhancing the coherence and consistency of regional delineations compared to conventional attribute-based clustering techniques such as K-means and DBSCAN [71]. According to the findings, the spatial autocorrelation (Moran’s I) within each region ranged from 0.58 to 0.67, which is notably higher than that achieved through traditional K-means clustering (0.35–0.52). This indicates that the proposed method better preserves spatial compactness and ecological homogeneity within regions, thus enhancing the spatial robustness of the regional model [72].

4.3. Comparison of Yield Estimates for Multi-Zone Schemes

Table 4 presents the accuracy of crop-yield estimation models and model validation results under three different zoning schemes. As shown in the table, the R2 value of the overall regional yield-estimation model without zoning is only 0.46. For the provincial zoning approach, R2 values range from 0.40 to 0.53, while for agricultural zoning, they vary between 0.42 and 0.52. These results demonstrate inconsistent predictive performance and considerable fluctuations in estimation errors. In contrast, the phenological zoning model achieves R2 values ranging from 0.54 to 0.68, with RRMSE maintained below 12.50%, indicating a significantly superior performance compared to the other two zoning schemes.

Table 4.

Comparison of different partition accuracy.

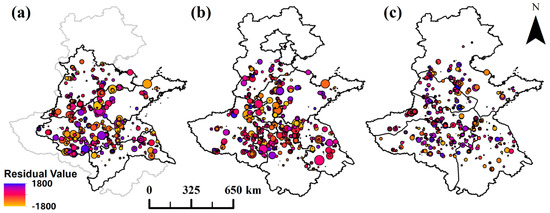

A residual analysis was performed by comparing the yield-estimation results for different zoning schemes (Figure 8 and Figure 9a,b) with the overall regional yield-estimation results (Figure 13). Models based on traditional agricultural or administrative zoning exhibited noticeable error clustering in southern Henan and northern Anhui, whereas the phenological zoning model produced a more uniform residual distribution and greater within-zone consistency. Quantitatively, Moran’s I for the phenological zoning model (0.2595, p < 0.001) was lower than that of the non-zonal model (0.3038, p < 0.001), confirming reduced spatial autocorrelation of residuals. Paired-sample tests also indicated significantly smaller absolute errors for the zonal model (p < 0.001), and bootstrap resampling (n = 1000) showed a higher R2 (0.6628 vs. 0.4600) with a robust improvement of 0.2028 (95% CI: 0.1821–0.2269). These findings demonstrate that phenological zoning improves not only model accuracy and stability but also spatial consistency and robustness in yield estimation.

Figure 13.

Residual distribution maps of the three zoning yield estimates: agricultural zoning results (a) administrative zoning results (b) phenological zoning results (c).

4.4. Analysis of the Relative Contribution of Multi-Source Feature Factors to Wheat-Yield Estimation

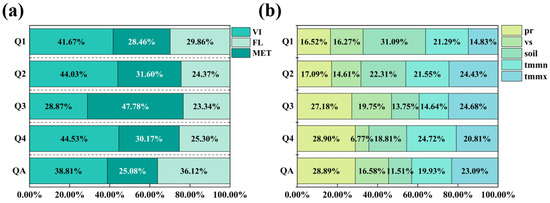

This study incorporated vegetation indices (VI:GNDVI, EVI, GOSAVI, ARVI, NDVI) and growth parameters (FL:GOSIF, GPP, LAI, FPAR) of winter wheat during the grain filling period—from early May to early June—in the Huang-Huai-Hai region. These variables were combined with concurrent ERA5 meteorological data (MET), including temperature, precipitation, wind speed, and soil moisture, to serve as input features. A wheat yield-estimation model was developed using a hybrid approach integrating the RF algorithm with BO. The results demonstrated that the yield-estimation model based on phenological zoning exhibited significantly higher accuracy and generalizability compared to the non-zoning model. Furthermore, the SHAP (Shapley Additive explanations) method was applied to systematically evaluate the feature importance of the zoned model, as illustrated in Figure 14. SHAP analyses were performed separately for each phenological zone, with all variables standardized within zones prior to model training to ensure comparability of SHAP magnitudes.

Figure 14.

Multi-source feature factors’ contribution to wheat-yield estimation. (a) VI, FL, and MET contribution proportions and (b) Meteorological factor contribution proportions; VI, MET, and FL represent vegetation indices, meteorological variables, and growth parameters, respectively. pr, vs, soil, tmmn, and tmmx denote precipitation.

Whole regional yield modeling averages meteorological factors spatially and temporally across the entire Huang-Huai-Hai region throughout the crop growth period, which may reduce the impact of climatic stress during critical growth stages and lead to an imbalanced distribution of feature weights [18]. In this study, the non-zoning model revealed that meteorological factors accounted for 25.08% of the variance in yield estimation, whereas vegetation indices (38.80%) and growth parameters (36.12%) demonstrated relatively greater explanatory power. In contrast, a phenological zoning strategy based on the heading stage can enhance the integration of variables within each subregion, thereby more effectively capturing the dominant factors specific to each area. For example, meteorological factors contributed 47.78% in Q3, whereas vegetation indices contributed 41.67%, 44.03%, and 44.53% in Q1, Q3, and Q4, respectively, indicating notable variations in the distribution of feature contributions across different regions. Additionally, the contributions of different meteorological factors to wheat-yield estimation vary across regions (Figure 14b). Therefore, the phenological zoning model not only outperforms overall regional modeling in terms of yield-estimation accuracy and spatial adaptability but also demonstrates greater effectiveness in depicting the spatial heterogeneity of winter wheat growth processes. By avoiding the dilution of local characteristics that can occur due to varying ecological conditions in overall regional modeling [73], the model enables a more nuanced exploration of the potential effects of multiple factors within each sub-region, thereby enhancing the precision of yield estimation.

4.5. Analysis of the Application Limitations and Development Directions of Phenological Zoning Models

Although the phenological zoning model developed in this study demonstrated strong performance in estimating winter wheat yield across the Huang-Huai-Hai region, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the current zoning framework primarily relies on a single phenological stage (heading stage) and does not fully integrate dynamic information from multiple critical growth stages—such as green-up, jointing, grain-filling, and maturity—potentially overlooking the influence of other stages on spatial yield variability. Moreover, cultivar and management practices (e.g., sowing date, irrigation regime) may co-vary with phenological development and yield formation, suggesting that the derived zones may partly reflect combined effects of both climatic and management gradients. Future research should incorporate multi-stage phenological indicators and management-related proxies to develop a multi-source, data-driven zoning framework with enhanced explanatory power [74,75]. Second, model uncertainty remains insufficiently characterized, partly due to the limited and uneven validation data, which may constrain model robustness under different cropping systems. Conventional metrics such as RRMSE cannot fully capture zone-specific or stress-dependent uncertainties. Future studies should integrate ensemble or probabilistic approaches with broader field observations to better quantify uncertainty and improve model generalizability. Finally, although this study primarily employs traditional machine learning algorithms, in future work, we plan to explore deep learning architectures—such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and graph neural networks (GNNs)—to more effectively capture complex spatial structures and nonlinear relationships, thereby enabling automated and more generalizable regional yield estimation under diverse climatic and management conditions [76,77,78,79]. Future studies should integrate high-resolution remote sensing, extensive field observations, and regional surveys, and establish cross-regional, multi-year phenological zoning frameworks to enhance the model’s robustness and transferability under varying environmental and management contexts.

5. Conclusions

This study focuses on the spatial heterogeneity in winter wheat-yield estimation in the Huang-Huai-Hai region. Based on remote sensing monitoring of heading stage information, a spatially continuous phenological zoning was constructed. On this basis, remote sensing and meteorological variables were integrated to construct a zoning-driven yield-estimation model. The conclusions of this study are as follows:

- The phenological zones of winter wheat in the Huang-Huai-Hai region, constructed using KNN-Ward spatial clustering, exhibit distinct boundaries and high internal phenological consistency. The notable differences in phenological stages across these zones demonstrate that the method effectively captures the spatiotemporal heterogeneity inherent in crop growth processes.

- This study uses the heading stage as the basis for phenological zoning and constructs yield-estimation models for different phenological zones. This helps eliminate differences in crop growth systems caused by phenology when modeling large areas, as these differences often do not directly indicate abnormalities in crop yields. The model focuses on the spatial heterogeneity of key physiological stages caused by other factors within the zone, significantly improving estimation accuracy and model generalization capabilities.

- Compared to the non-zoning yield-estimation model, the random forest yield-estimation model based on phenological zones demonstrates improved accuracy and reduced error variability across individual zones. Furthermore, in comparison to wheat yield models developed using agricultural zoning and administrative divisions, the phenological zoning-based model exhibits a more balanced residual distribution and enhanced model robustness, thereby confirming the scientific validity and practical applicability of the phenology-driven modeling approach.

Author Contributions

Q.W. and X.S. processed and analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. G.Y. guided the experimental design, participated in data collection, advised on data analysis, and revised the manuscript. J.Z., Y.M., C.Z. and T.W. were involved in the experiments, ground data collection, and/or manuscript revision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFB3906204).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the help from Pingping Li, Hong Chang and Weiguo Li during field data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Figure A1.

Comparison of Accuracy between Wheat Proportion Less than 0.6 (a) and Greater than 0.6 (b).

Appendix A.2

Table A1.

Hyperparameter search space and optimization settings for the Bayesian-Optimized Random Forest (BO-RF) model.

Table A1.

Hyperparameter search space and optimization settings for the Bayesian-Optimized Random Forest (BO-RF) model.

| Parameter | Search Space/Values | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Number of decision trees | [50, 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, 700, 800, 900, 1000] | Discrete |

| Maximum depth of each tree | 3–30 | Integer |

| Minimum number of samples required to split an internal node | 2–50 | Integer |

| Minimum number of samples required to be at a leaf node | 1–20 | Integer |

| Number of features to consider when looking for the best split | {‘sqrt’, ‘log2’, None} | Categorical |

| Whether bootstrap samples are used when building trees | {True, False} | Binary |

| Total number of optimization iterations | 50 | |

| Number of parallel processes | 16 | |

| Reproducibility control | 42 |

References

- FAO. World Food and Agriculture–Statistical Yearbook 2024; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; ISBN 978-92-5-139255-3. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.U.; Guo, Z.; Jiang, F.; Peng, X. Does Straw Return Increase Crop Yield in the Wheat-Maize Cropping System in China? A Meta-Analysis. Field Crops Res. 2022, 279, 108447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Song, N.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; He, J. Estimating the Potential Yield and ETc of Winter Wheat across Huang-Huai-Hai Plain in the Future with the Modified DSSAT Model. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, M.P.; Slafer, G.A.; Foulkes, J.M.; Griffiths, S.; Murchie, E.H.; Carmo-Silva, E.; Asseng, S.; Chapman, S.C.; Sawkins, M.; Gwyn, J.; et al. Author Correction: A Wiring Diagram to Integrate Physiological Traits of Wheat Yield Potential. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyene, A.N.; Zeng, H.; Wu, B.; Zhu, L.; Gebremicael, T.G.; Zhang, M.; Bezabh, T. Coupling Remote Sensing and Crop Growth Model to Estimate National Wheat Yield in Ethiopia. Big Earth Data 2022, 6, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, M.P.; Braun, H.-J. (Eds.) Wheat Improvement. In Wheat Improvement; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 3–15. ISBN 978-3-030-90672-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Yu, S.; Yu, Z. Spatiotemporal Coupling of Grain Production, Economic Development, and ecological protection in China’s major grain-Producing areas. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2025, 45, 1659–1673. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Xu, X.; Liu, S.; Jia, J.; Li, M.; Huang, H.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, C. Optimizing Wheat Prosperity: Innovative Drip Irrigation and Nitrogen Management Strategies for Enhanced Yield and Quality of Winter Wheat in the Huang-Huai-Hai Region. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1454205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, S.; Tao, F.; Aboelenein, R.; Amer, A. Improving Winter Wheat Yield Forecasting Based on Multi-Source Data and Machine Learning. Agriculture 2022, 12, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, Q.; Pei, Z.; Wang, L.; Ma, Z.; Pan, X. Winter Wheat Yield Forecast Multi-Stage Model. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2012, 43, 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Schierhorn, F.; Hofmann, M.; Gagalyuk, T.; Ostapchuk, I.; Müller, D. Machine Learning Reveals Complex Effects of Climatic Means and Weather Extremes on Wheat Yields during Different Plant Developmental Stages. Clim. Change 2021, 169, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, K.; Schelde, K.; Olesen, J.E. Winter Wheat Yield Response to Climate Variability in Denmark. J. Agric. Sci. 2011, 149, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shi, J.; Shen, Y. Climate Change and Its Effect on Winter Wheat Yield in the Main Winter Wheat Production Areas of China. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2022, 30, 723–734. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Wang, L.; Guo, Y.; Cui, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, T.; Li, H. A Comprehensive Evaluation of Dual-Polarimetric Sentinel-1 SAR Data for Monitoring Key Phenological Stages of Winter Wheat. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Donohue, R.J.; McVicar, T.R.; Waldner, F.; Mata, G.; Ota, N.; Houshmandfar, A.; Dayal, K.; Lawes, R.A. Nationwide Crop Yield Estimation Based on Photosynthesis and Meteorological Stress Indices. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 284, 107872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wu, B.; Meng, J.; Li, Q.; Huang, W.; Liu, L.; Wang, J. Research Advances in Crop Yield Estimation Models Based on Remote Sensing. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2008, 24, 290–298. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Gao, L.; Fan, C.; Xu, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Niu, F.; Li, Z. Time Phase Selection and Accuracy Analysis for Predicting Winter Wheat Yield Based on Time Series Vegetation Index. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhu, W.; Zhao, C.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, H. Phenological Piecewise Modelling Is More Conducive than Whole-Season Modelling to Winter Wheat Yield Estimation Based on Remote Sensing Data. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2022, 55, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Hu, L.; Wu, H.; Ren, H.; Qiao, H.; Li, P.; Fan, W. Integration of Crop Growth Model and Random Forest for Winter Wheat Yield Estimation From UAV Hyperspectral Imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 6253–6269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Tang, C.; Cao, Q.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.; Liu, X. Estimation of Rice Growth Parameters Based on Linear Mixed-Effect Model Using Multispectral Images from Fixed-Wing Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.T.; Awange, J.; Kuhn, M.; Nguyen, B.V.; Bui, L.K. Enhancing Crop Yield Prediction Utilizing Machine Learning on Satellite-Based Vegetation Health Indices. Sensors 2022, 22, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.K.; Kalra, N. Simulating Impact of Climatic Variability and Extreme Climatic Events on Crop Production. MAUSAM 2016, 67, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Villegas, J.; Koehler, A.-K.; Challinor, A.J. Assessing Uncertainty and Complexity in Regional-Scale Crop Model Simulations. Eur. J. Agron. 2017, 88, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouadio, L.; Newlands, N.K. Building Capacity for Assessing Spatial-Based Sustainability Metrics in Agriculture. Decis. Anal. 2015, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Huang, C.; Liu, Q.; Cai, C.; Liu, G. Spatial Heterogeneity of Winter Wheat Yield and Its Determinants in the Yellow River Delta, China. Sustainability 2019, 12, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhou, R.; He, P.; Yu, M.; Zheng, H.; Yao, X.; Cheng, T.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.; Tian, Y. Estimating Wheat Grain Yield by Assimilating Phenology and LAI with the WheatGrow Model Based on Theoretical Uncertainty of Remotely Sensed Observation. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 339, 109574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; Bheemanahalli, R.; Adeli, A.; Samiappan, S.; Czarnecki, J.M.P.; McCraine, C.D.; Reddy, K.R.; Moorhead, R. Phenological Stage and Vegetation Index for Predicting Corn Yield under Rainfed Environments. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1168732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Guan, K.; Chen, Z.; Hipple, J.; Huang, Y.; Peng, B.; Wang, S.; Xu, X.; Jin, Z.; Zhao, K.; et al. Aligning Satellite-Based Phenology in a Deep Learning Model for Improved Crop Yield Estimates over Large Regions. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2025, 372, 110675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Zhao, Z. An Inquiry into Method of Monitoring Growth Vigour of Winter Wheat and Estimating It Yield Using NOAAAVHRR, Landsat MSS and Spectral Data. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 1987, 274–284+323. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, G.; Chen, H.; Yu, W.; Su, W.; Cheng, Y. WOFOST Model Parameter Calibration Based on Agro-Climatic Division of Winter Wheat. J. Appl. Meteorol. Sci. 2021, 32, 38–51. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhang, J.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, W.; Hu, T. Division of Winter Wheat Yield Estimation by Remote Sensing Based on MODIS EVI Time Series Data and Spectral Angle Clustering. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2012, 32, 1899–1904. [Google Scholar]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Merzlyak, M.N. Use of a Green Channel in Remote Sensing of Global Vegetation from EOS-MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 58, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.; Didan, K.; Miura, T.; Rodriguez, E.P.; Gao, X.; Ferreira, L.G. Overview of the Radiometric and Biophysical Performance of the MODIS Vegetation Indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondeaux, G.; Steven, M.; Baret, F. Optimization of Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 55, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, Y.J.; Tanre, D. Atmospherically Resistant Vegetation Index (ARVI) for EOS-MODIS. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1992, 30, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.; Haas, R.H.; Deering, D.; Schell, J.A.; Harlan, J. Monitoring the Vernal Advancement and Retrogradation (Green Wave Effect) of Natural Vegetation; Great Plains Corridor; Texas A&M University: College Station, TX, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Myneni, R.; Knyazikhin, Y.; Glassy, J.; Votava, P.; Shabanov, N. User’s Guide FPAR, LAI (ESDT: MOD15A2) 8-Day Composite NASA MODIS Land Algorithm. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236770629 (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Zhang, Z.; Guanter, L.; Porcar-Castell, A.; Rossini, M.; Pacheco-Labrador, J.; Zhang, Y. Global Modeling Diurnal Gross Primary Production from OCO-3 Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 285, 113383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xiao, J. A Global, 0.05-Degree Product of Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence Derived from OCO-2, MODIS, and Reanalysis Data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xiao, J. Mapping Photosynthesis Solely from Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence: A Global, Fine-Resolution Dataset of Gross Primary Production Derived from OCO-2. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Dutra, E.; Agustí-Panareda, A.; Albergel, C.; Arduini, G.; Balsamo, G.; Boussetta, S.; Choulga, M.; Harrigan, S.; Hersbach, H.; et al. ERA5-Land: A State-of-the-Art Global Reanalysis Dataset for Land Applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 4349–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurjar, S.B.; Padmanabhan, N. Study of Various Resampling Techniques for High-Resolution Remote Sensing Imagery. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2005, 33, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, M.B.; Keith, D.A.; Phinn, S.R.; Mason, T.J.; Elith, J. A Comparison of Resampling Methods for Remote Sensing Classification and Accuracy Assessment. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 208, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, E. Dataset of Agricultural Resource and Environment Zoning of China. J. Glob. Change Data Discov. 2021, 5, 19–26+132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, J.; Liang, S.; Hou, D. Crop Area Estimation Based on MODIS-EVI Time Series According to Distinct Characteristics of Key Phenology Phases: A Case Study of Winter Wheat Area Estimation in Small-Scale Area. J. Remote Sens. 2011, 15, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Wu, B.; Liu, C.; Luo, Z. Methods of Monitoring Crop Phonological Stages Using Time Series of Vegetation Indicator. Trans. CSAE 2004, 20, 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Xie, Z.; Zhuo, W.; Huang, R. Extraction Method of Growth Stages of Winter Wheat Based on Accumulated Temperature and Remote Sensing Data. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2019, 50, 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Luo, W.; Gao, W. Summer Maize Phenology Monitoring Based on Normalized Difference Vegetation Index Reconstructed with Improved Maximum Value Composite. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2019, 35, 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, L.; Yan, H.; Bao, Y.; Chen, H. Remote Sensor Monitoring Method for Winter Wheat Growth Based on Key Development Periods. Chin. J. Agrometeorol. 2012, 33, 424–430. [Google Scholar]

- Dudani, S.A. The Distance-Weighted k-Nearest-Neighbor Rule. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1976, SMC-6, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cover, T.; Hart, P. Nearest Neighbor Pattern Classification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1967, 13, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getis, A.; Aldstadt, J. Constructing the Spatial Weights Matrix Using a Local Statistic. Geogr. Anal. 2004, 36, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavent, M.; Kuentz-Simonet, V.; Labenne, A.; Saracco, J. ClustGeo: An R Package for Hierarchical Clustering with Spatial Constraints. Comput. Stat. 2018, 33, 1799–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.H.; Resop, J.P.; Mueller, N.D.; Fleisher, D.H.; Yun, K.; Butler, E.E.; Timlin, D.J.; Shim, K.-M.; Gerber, J.S.; Reddy, V.R.; et al. Random Forests for Global and Regional Crop Yield Predictions. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstra, J.; Bardenet, R.; Bengio, Y.; Kégl, B. Algorithms for Hyper-Parameter Optimization. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Granada, Spain, 12–15 December 2011; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 2546–2554. [Google Scholar]

- Nanjundan, S.; Sankaran, S.; Arjun, C.R.; Anand, G.P. Identifying the Number of Clusters for K-Means: A Hypersphere Density Based Approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.00643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A Graphical Aid to the Interpretation and Validation of Cluster Analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, G.W.; Cooper, M.C. An Examination of Procedures for Determining the Number of Clusters in a Data Set. Psychometrika 1985, 50, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calinski, T.; Harabasz, J. A Dendrite Method for Cluster Analysis. Comm. Stats.-Theory Methods 1974, 3, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodinariya, T.M.; Makwana, P.R. Review on Determining Number of Cluster in K-Means Clustering. Int. J. 2013, 1, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña Villota, T.M.; Cotes Torres, J.M. Comparison of Statistical Indices for the Evaluation of Crop Models Performance. Rev. Fac. Nac. Agron. Medellín 2021, 74, 9675–9684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meij, B.; Kooistra, L.; Suomalainen, J.; Barel, J.M.; De Deyn, G.B. Remote Sensing of Plant Trait Responses to Field-Based Plant–Soil Feedback Using UAV-Based Optical Sensors. Biogeosciences 2017, 14, 733–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Huang, J.; Peng, D. Detecting Major Growth Stages of Paddy Rice Using MODIS Data. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 2021, 13, 1122–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Bai, J.; Xu, B.; Zhao, J.; Zeng, Y. Validation and Analysis of Remote Sensing Phenology Products in the Heihe River Basin. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 2021, 21, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Moiwo, J.P.; Tao, F.; Yang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Xu, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, F. Spatiotemporal Variability of Winter Wheat Phenology in Response to Weather and Climate Variability in China. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2015, 20, 1191–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Tao, F.; Shen, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, R. Sensitivity of Response of Winter Wheat to Climate Change in the North China Plain in the Last Three Decades. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2014, 22, 430–438. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Kuang, M.; Shi, L.; Zhong, L.; Yi, M. Extracting the Phenological Periods of Winter Wheat at Field Scale Based on the Characteristics of NDVI Time Series Curves from Multisource Remote Sensing Image. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2025, 41, 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, F.; Casa, R.; Tolomio, M.; Dalponte, M.; Mzid, N. Soil Properties Zoning of Agricultural Fields Based on a Climate-Driven Spatial Clustering of Remote Sensing Time Series Data. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 150, 126930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Dai, J.; Ji, Z.; Pan, Y. Yield Estimation Model of Staple Crops in Heilongjiang: Taking Rice, Soybean and Corn as Examples. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2024, 24, 3638–3645. [Google Scholar]

- Młodak, A. K-Means, Ward and Probabilistic Distance-Based Clustering Methods with Contiguity Constraint. J. Classif. 2021, 38, 313–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Tan, S.; Zhang, L. Influences of Different Land Use Spatial Control Schemes on Farmland Conversion and Urban Development. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Cao, J. Spatiotemporal Patterns of Winter Wheat Phenology and Its Climatic Drivers Based on an Improved pDSSAT Model. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2021, 64, 2144–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Y. Winter Wheat Yield Prediction Based on Crop Growth Time Series Characteristics Combined with Multi-Source Data and Deep Learning. Master’s Thesis, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zheng, G.; Guo, Y.; He, J.; Cheng, Y. Prediction of Winter Wheat Yield Based on Fusing Multi-Source Spatio-Temporal Data. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2022, 53, 198–204,458. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, H.; Wang, P.; Tansey, K.; Wang, J.; Quan, W.; Liu, J. Attention Mechanism-Based Deep Learning Approach for Wheat Yield Estimation and Uncertainty Analysis from Remotely Sensed Variables. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 356, 110183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Tansey, K.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S. Enhancing Winter Wheat Yield Estimation With a CNN-Transformer Hybrid Framework Utilizing Multiple Remotely Sensed Parameters. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, S.M.M.; Abbasi-Moghadam, D.; Sharifi, A.; Farmonov, N.; Amankulova, K.; Lászlź, M. Multispectral Crop Yield Prediction Using 3D-Convolutional Neural Networks and Attention Convolutional LSTM Approaches. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaki, S.; Wang, L. Crop Yield Prediction Using Deep Neural Networks. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).