Terahertz Squint SAR Imaging Based on Decoupled Frequency Scaling Algorithm

Highlights

- In the terahertz band, the two-dimensional coupling effect under high-squint-angle conditions is aggravated, making phase errors non-negligible and causing traditional frequency-domain algorithms to fail to achieve precise focusing. Therefore, this paper proposes a terahertz squint SAR imaging algorithm based on decoupled frequency scaling.

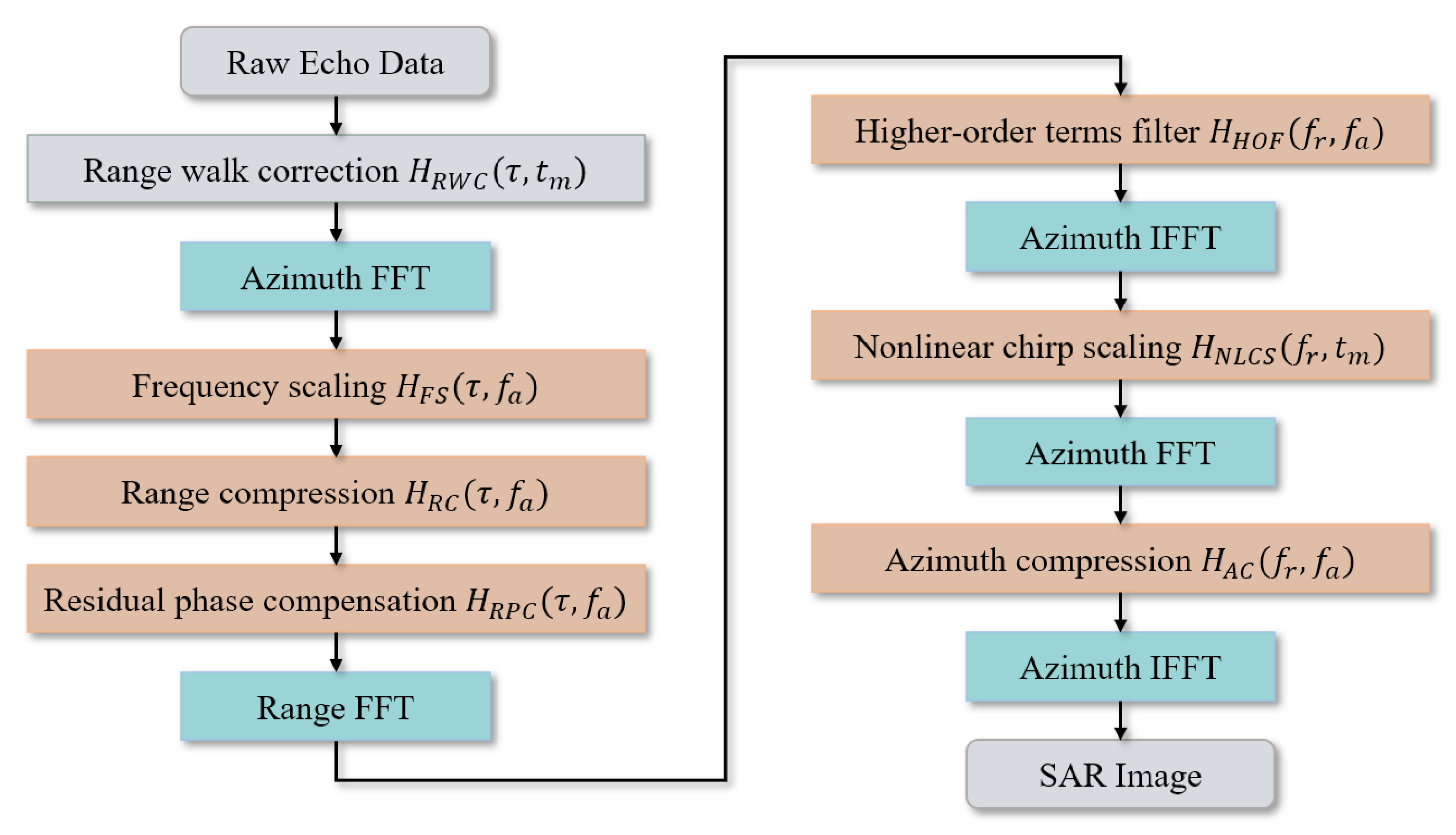

- Following time-domain decoupling, the proposed algorithm combined range frequency scaling with azimuth nonlinear chirp scaling, which can achieve better imaging results.

- The experimental results show that the proposed algorithm can achieve better imaging results and provide an effective technical approach to squint SAR imaging in the terahertz band.

- This result has application value in airborne terahertz radar detection, cooperative observation of UAV formation, and other fields.

Abstract

1. Introduction

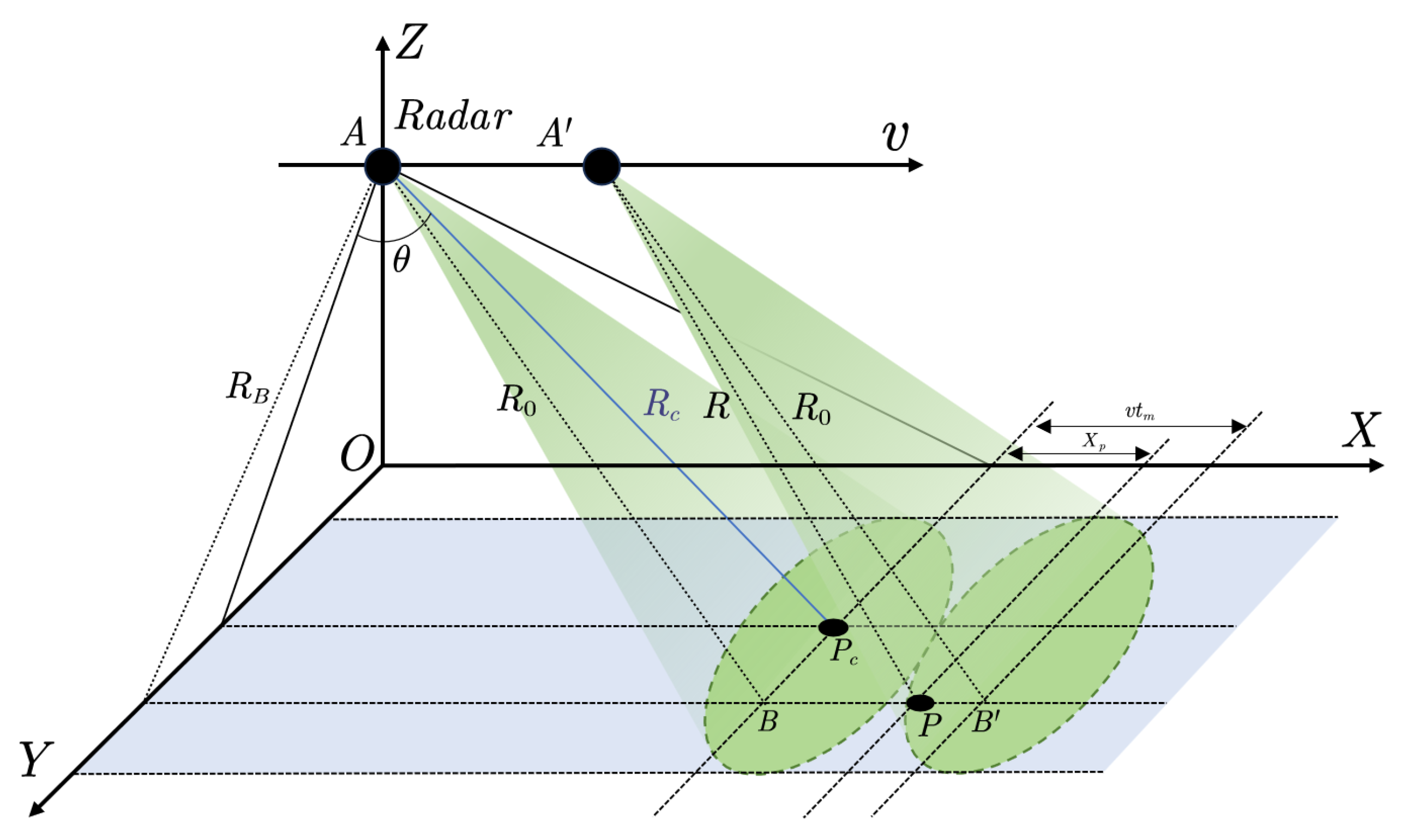

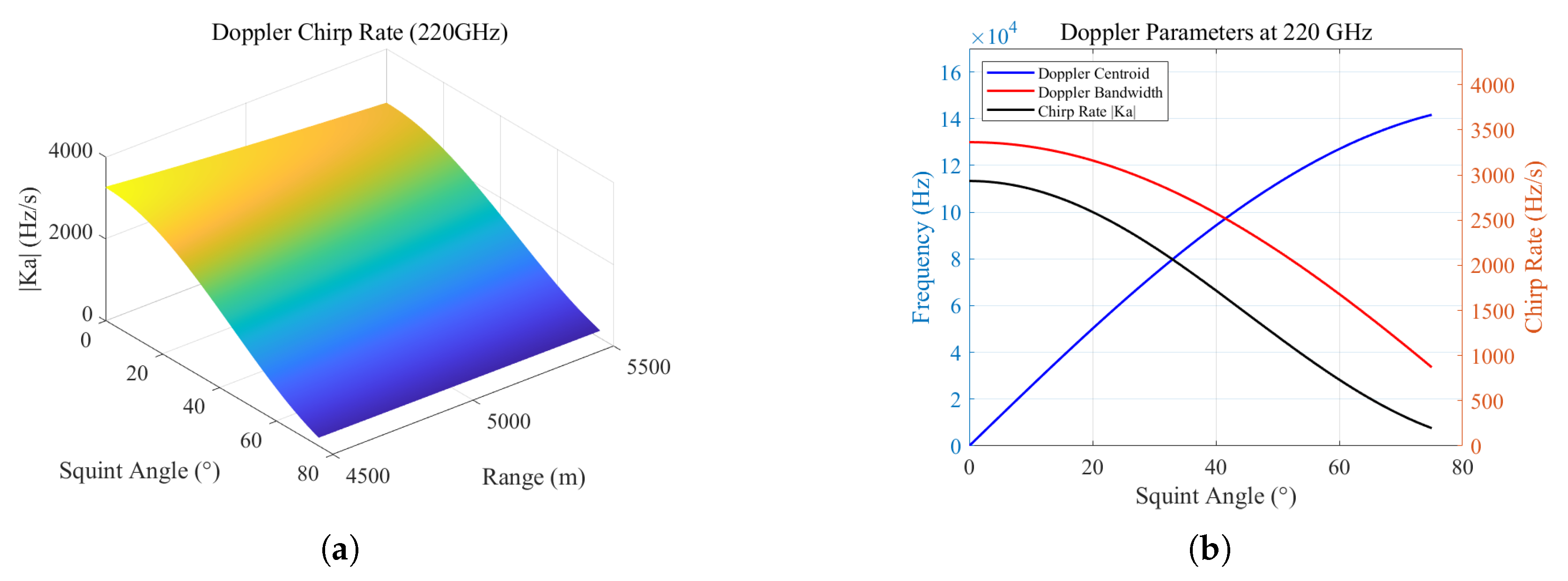

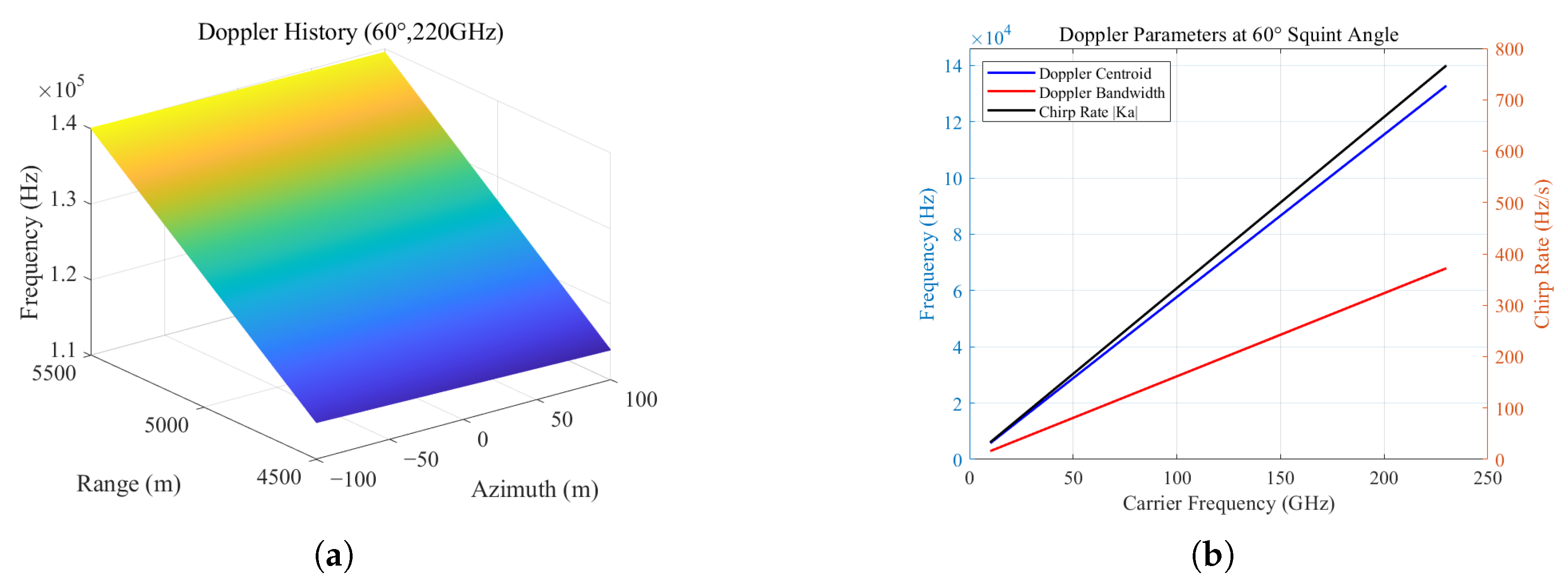

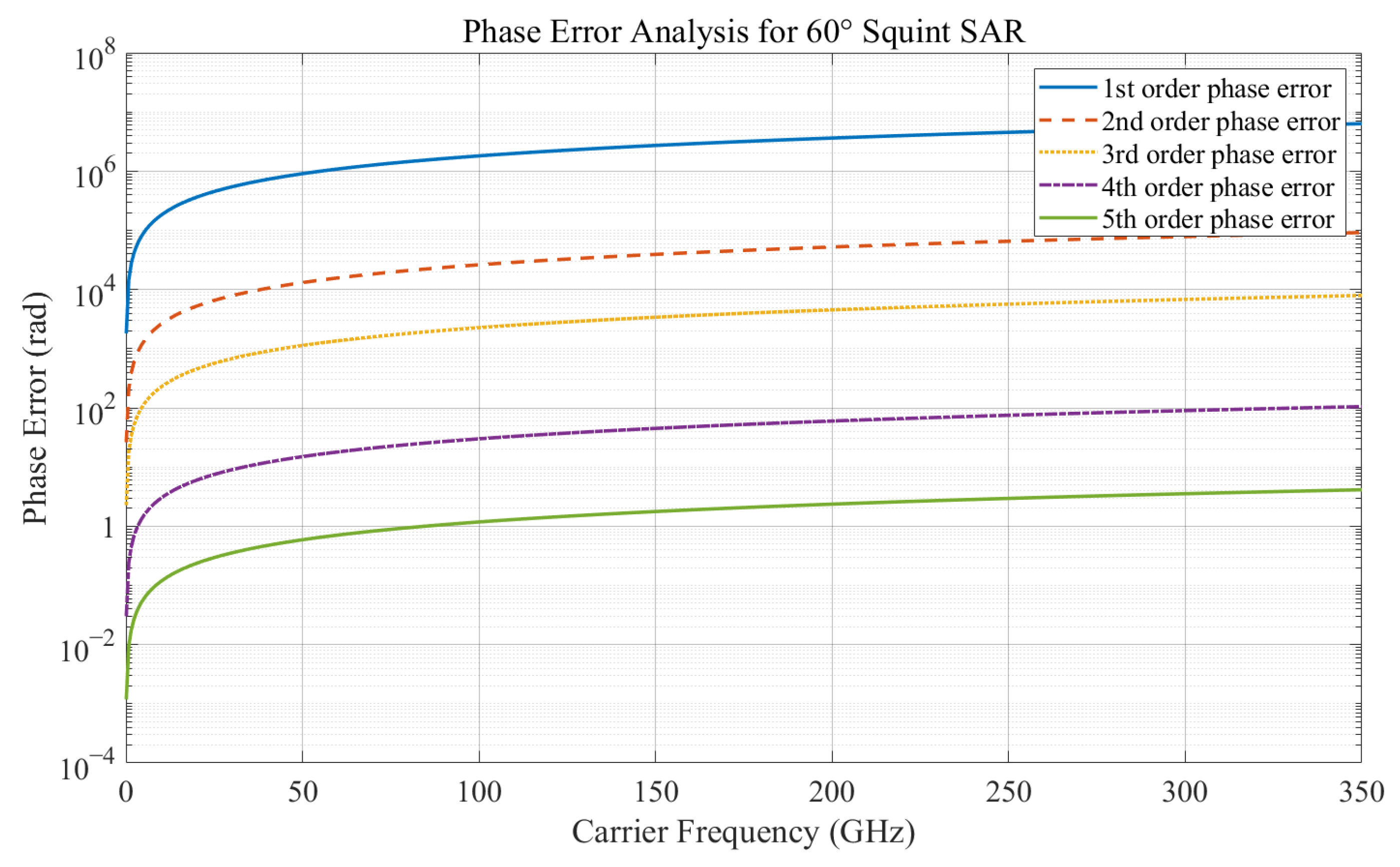

2. Signal Model

3. Methods

4. Simulations and Experimental Results

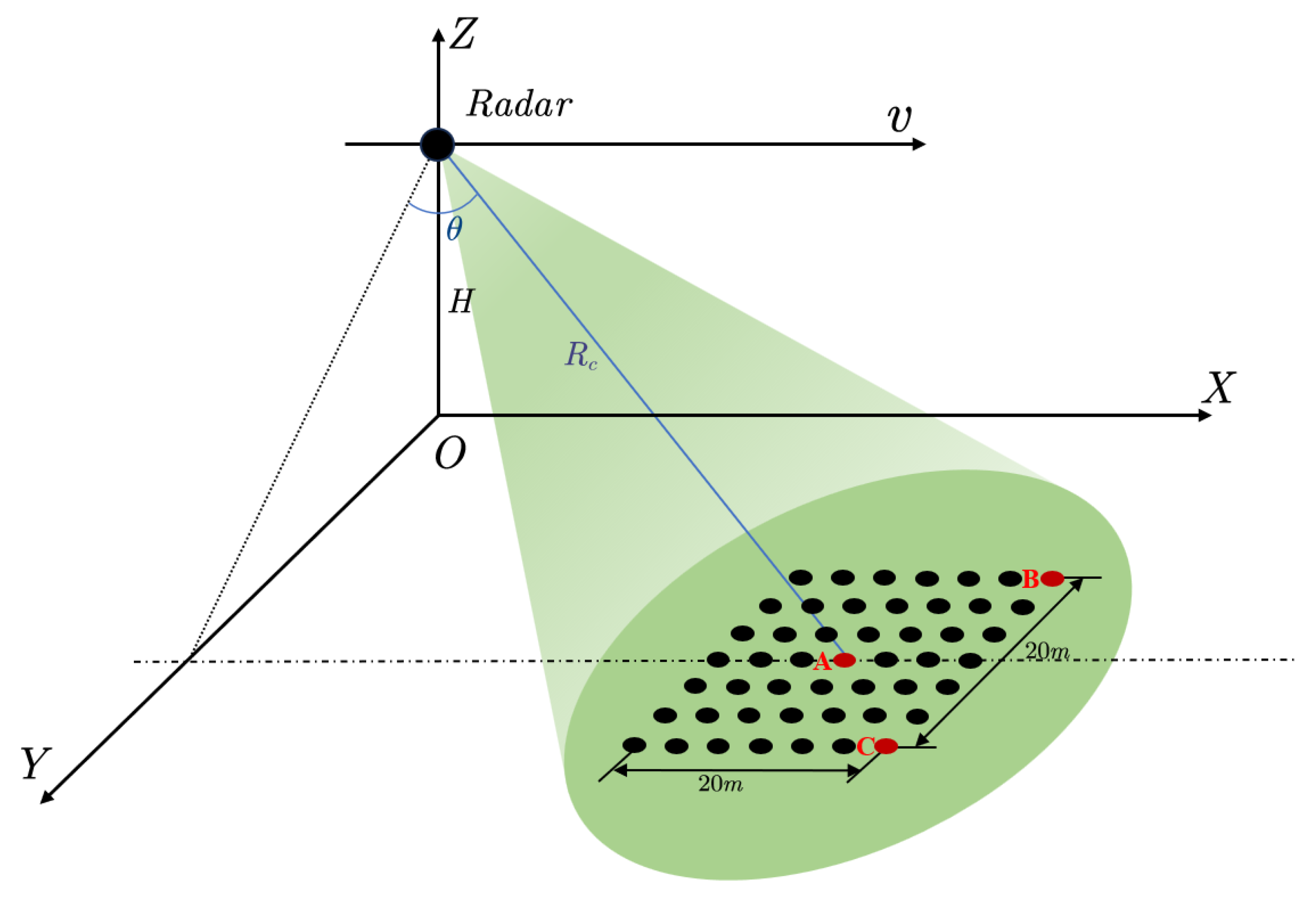

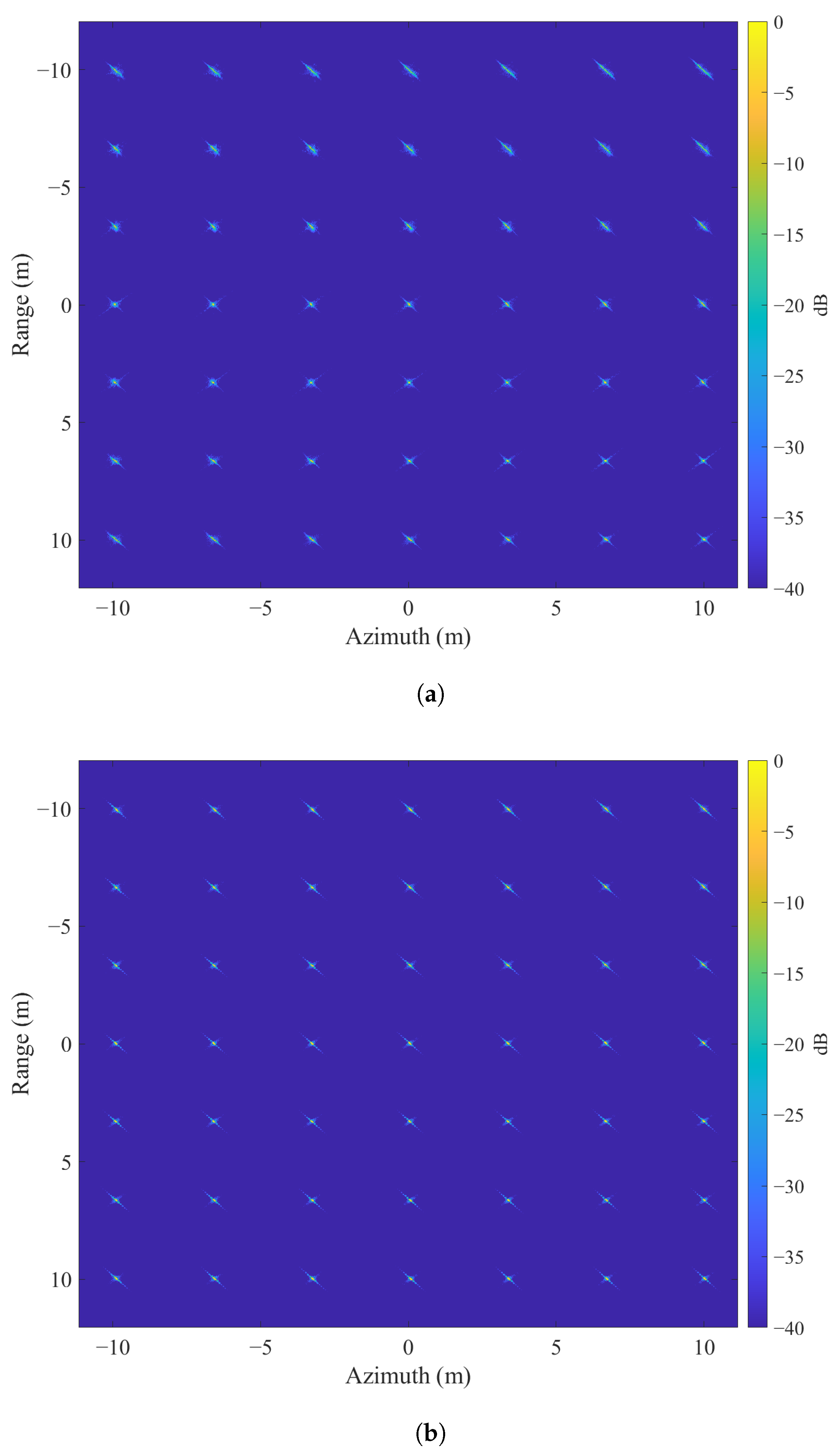

4.1. Simulations

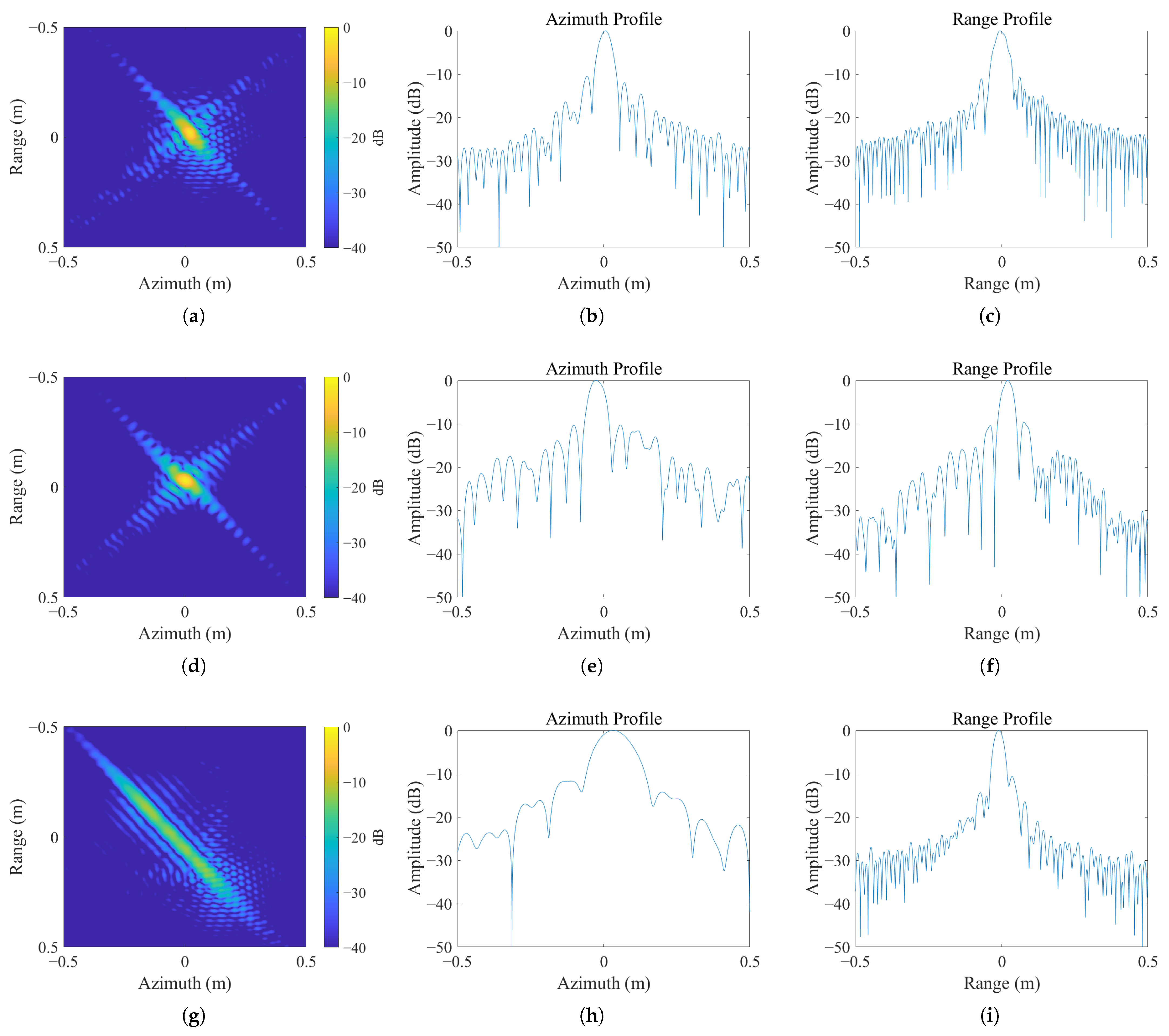

4.2. Experimental Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davidson, G.W.; Cumming, I. Signal properties of spaceborne squint-mode SAR. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2002, 35, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Fan, L.; Yi, J.; Wang, H. A Novel High Precision Terahertz Video SAR Imaging Method. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 22, 4002405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezimati, M.; Singh, G. Curved synthetic aperture radar for near-field terahertz imaging. IEEE Photon. J. 2023, 15, 5900113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Q.; Hua, X.; Wang, H. A Motion Compensation Method for Terahertz SAR Imaging with a Large Squint. Photonics 2024, 11, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, J.; Shi, S.; Li, C.; Cheng, W.; Fang, G. An efficient algorithm based on frequency scaling for THz stepped-frequency SAR imaging. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5225815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Q. A THz Video SAR Imaging Algorithm Based on Chirp Scaling. In Proceedings of the 2021 CIE International Conference on Radar (Radar), Haikou, China, 15–20 December 2021; pp. 656–660. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L.; Yang, Q.; Wang, H.; Qin, Y.; Deng, B. Sequential ground moving target imaging based on hybrid ViSAR-ISAR image formation in terahertz band. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 8738–8753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, A.; Barowski, J.; Damyanov, D.; Wiemeler, M.; Rolfes, I.; Schultze, T.; Balzer, J.C.; Göhringer, D.; Kaiser, T. Short-range SAR imaging from GHz to THz waves. IEEE J. Microw. 2021, 1, 574–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Su, F.; Gao, J.; Jin, X. High-squint SAR imaging of maritime ship targets. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 60, 5200716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Rao, B.S.M.R.; Murtada, A.; Alaee-Kerahroodi, M.; Ottersten, B. Automotive squint-forward-looking SAR: High resolution and early warning. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2021, 15, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, X. First Study on the Processing Approach of DBF for Squint Spaceborne SAR Imaging. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5217716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Bao, M.; Sun, G.; Han, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, M. Refocusing of moving ships in squint SAR images based on spectrum orthogonalization. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Min, R.; Li, L.; Ding, Z. High-squint high-frame-rate uniform-resolution video SAR: Parameter design and fast imaging. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2023, 59, 9160–9176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhou, X.; He, T.; Chen, J. A Decoupled Chirp Scaling Algorithm for High-Squint SAR Data Imaging. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5213417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, P.; Men, Z.; He, T.; Chen, J. A hybrid chirp scaling algorithm for squint sliding spotlight SAR data imaging. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 4005005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jin, S.; Li, G.; Bi, H. Frequency-Scaling-Based Spaceborne Squint SAR Sparse Imaging. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 8064–8073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Liu, X. Nonlinear frequency scaling algorithm for high squint spotlight SAR data processing. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2008, 2008, 657081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- An, D.; Huang, X.; Jin, T.; Zhou, Z. Extended nonlinear chirp scaling algorithm for high-resolution highly squint SAR data focusing. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2012, 50, 3595–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, P.; Men, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhou, X.; He, T.; Cui, L. A modified Range Doppler algorithm for high-squint SAR data imaging. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Wei, P. Modified range-Doppler algorithm for high squint SAR echo processing. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2018, 16, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Chen, J.; Xing, M.; Chen, X.; You, D.; Sun, G. 2-D frequency autofocus for squint spotlight SAR imaging with extended omega-K. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5211312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Xing, M.; Guo, L.; Zhang, P. A modified range model and extended omega-K algorithm for high-speed-high-squint SAR with curved trajectory. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5204515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Xu, H.P.; Sun, B. A parameter-adjusting polar format algorithm for extremely high squint SAR imaging. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2013, 52, 640–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, G.; Lu, J. Improved parametric polar format algorithm for high-squint and wide-beam SAR imaging. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5213916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Wu, F.; Wang, A. Extended Polar Format Algorithm (EPFA) for High-Resolution Highly Squinted SAR. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhang, B.; Wang, X.; Qi, X. An accurate and efficient BP algorithm based on precise slant range model and rapid range history construction method for GEO SAR. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, L.; Liu, Z.; Li, T.; Xie, R.; Zhang, L. An adaptive fast factorized back-projection algorithm with integrated target detection technique for high-resolution and high-squint spotlight SAR imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2017, 11, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; Sun, B.; Yan, M.; Xue, C.; Li, J. Modified auto-focusing algorithm for high squint diving SAR imaging based on the back-projection algorithm with spectrum alignment and truncation. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahay, P.; Kiran, K.L. Squint SAR Algorithm for Real-Time SAR Imaging. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Computing and Communication Technologies (CONECCT), Bangalore, India, 8–10 July 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, Z.; Hou, Z.; Li, D.; He, F.; Dong, Z. An Improved Range-Doppler Algorithm In High Squint Spaceborne SAR Imaging. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Signal, Information and Data Processing (ICSIDP), Zhuhai, China, 22–24 November 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Batra, A.; Zantah, Y.; Vu, V.T.; Wiemeler, M.; Pettersson, M.I.; Goehringer, D.; Kaiser, T. Experimental analysis of high resolution indoor THz SAR imaging. In Proceedings of the WSA 2020: 24th International ITG Workshop on Smart Antennas, Hamburg, Germany, 18–20 February 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L.; Yang, Q.; Wang, H.; Deng, B. Robust ground moving target imaging using defocused RoI data and sparsity-based ADMM autofocus under terahertz video SAR. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 2003816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Description | Value |

|---|---|

| Carrier frequency | 220 GHz |

| Bandwidth | 5 GHz |

| Pulse width | 26 µs |

| Pulse repetition frequency | 10 kHz |

| Reference distance | 3 km |

| Height | 1 km |

| Radar velocity | 60 m/s |

| Squint angle | 60° |

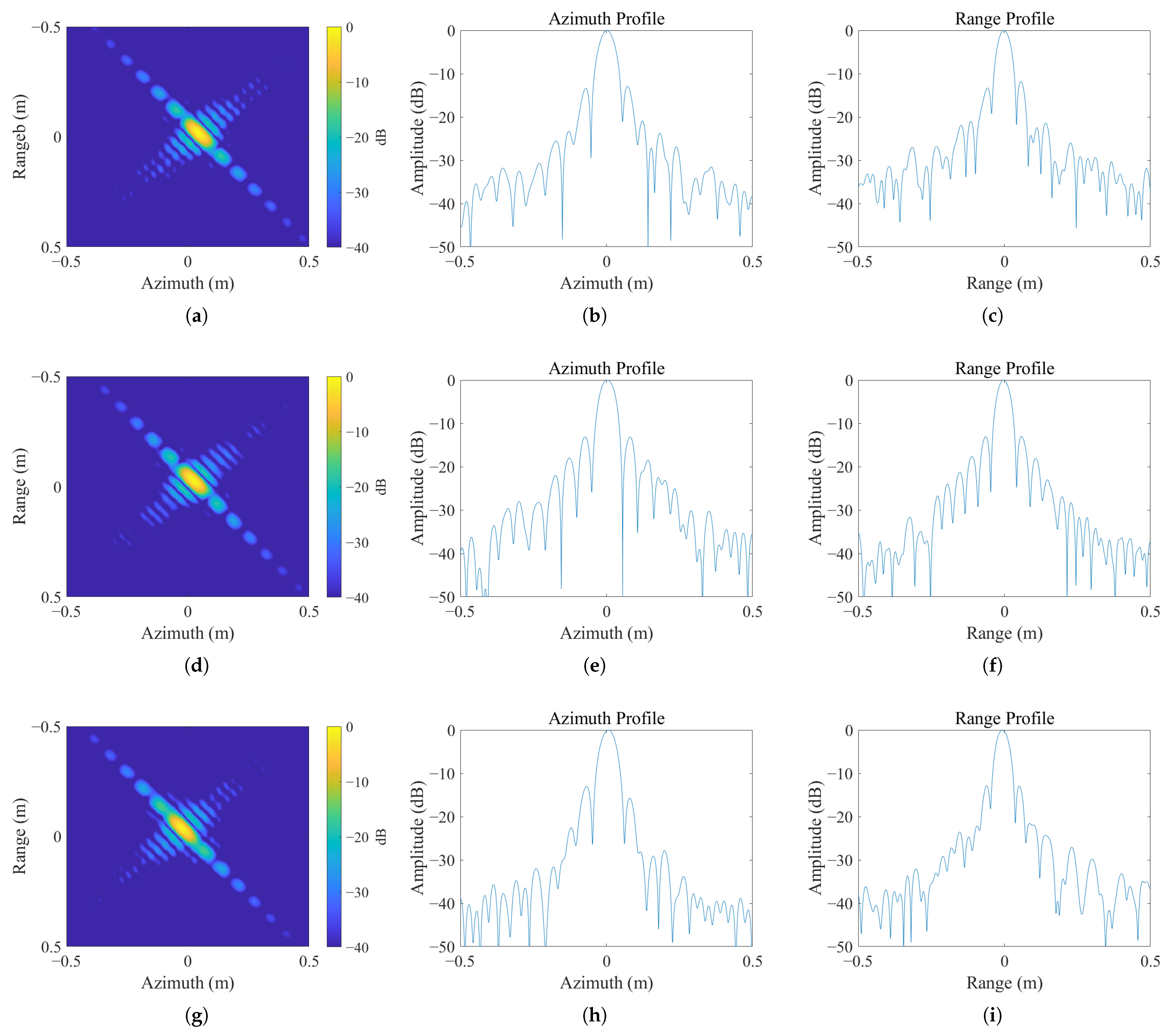

| Imaging Result of NFSA (A/B/C) | Imaging Result of the Proposed Algorithm (A/B/C) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IRW (cm) | Range | 6.48/6.72/7.21 | 6.03/6.19/6.23 |

| Azimuth | 6.63/7.91/13.15 | 6.34/6.72/6.89 | |

| PSLR (dB) | Range | −12.03/−11.14/−10.65 | −13.56/−13.93/−13.63 |

| Azimuth | −11.56/−10.98/−10.78 | −13.87/−13.06/−13.42 | |

| ISLR (dB) | Range | −10.35/−9.13/−9.01 | −11.56/−11.04/−11.32 |

| Azimuth | −9.62/−8.03/−6.47 | −11.23/−10.92/−10.39 |

| Description | Value |

|---|---|

| Carrier frequency | 220 GHz |

| Bandwidth | 900 MHz |

| Pulse repetition frequency | 15 kHz |

| Reference distance | 3 km |

| Radar velocity | 60 m/s |

| Squint angle | 60° |

| Azimuth beamwidth | 1.4° |

| Flying height | 1 km |

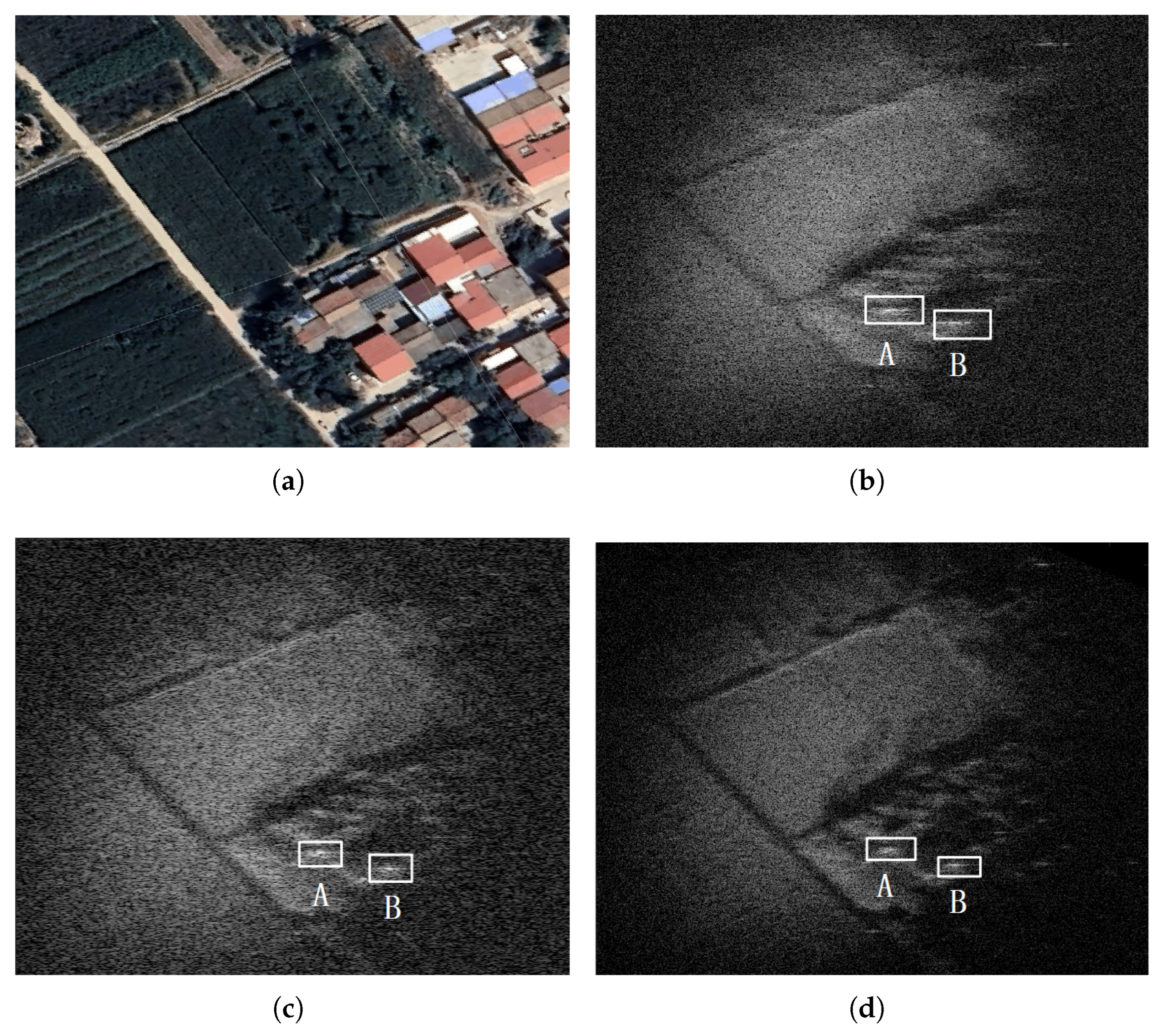

| RDA | NFSA | The Proposed Algorithm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Image entropy | 5.21 | 4.93 | 4.58 |

| Image contrast | 5.43 | 5.52 | 5.91 |

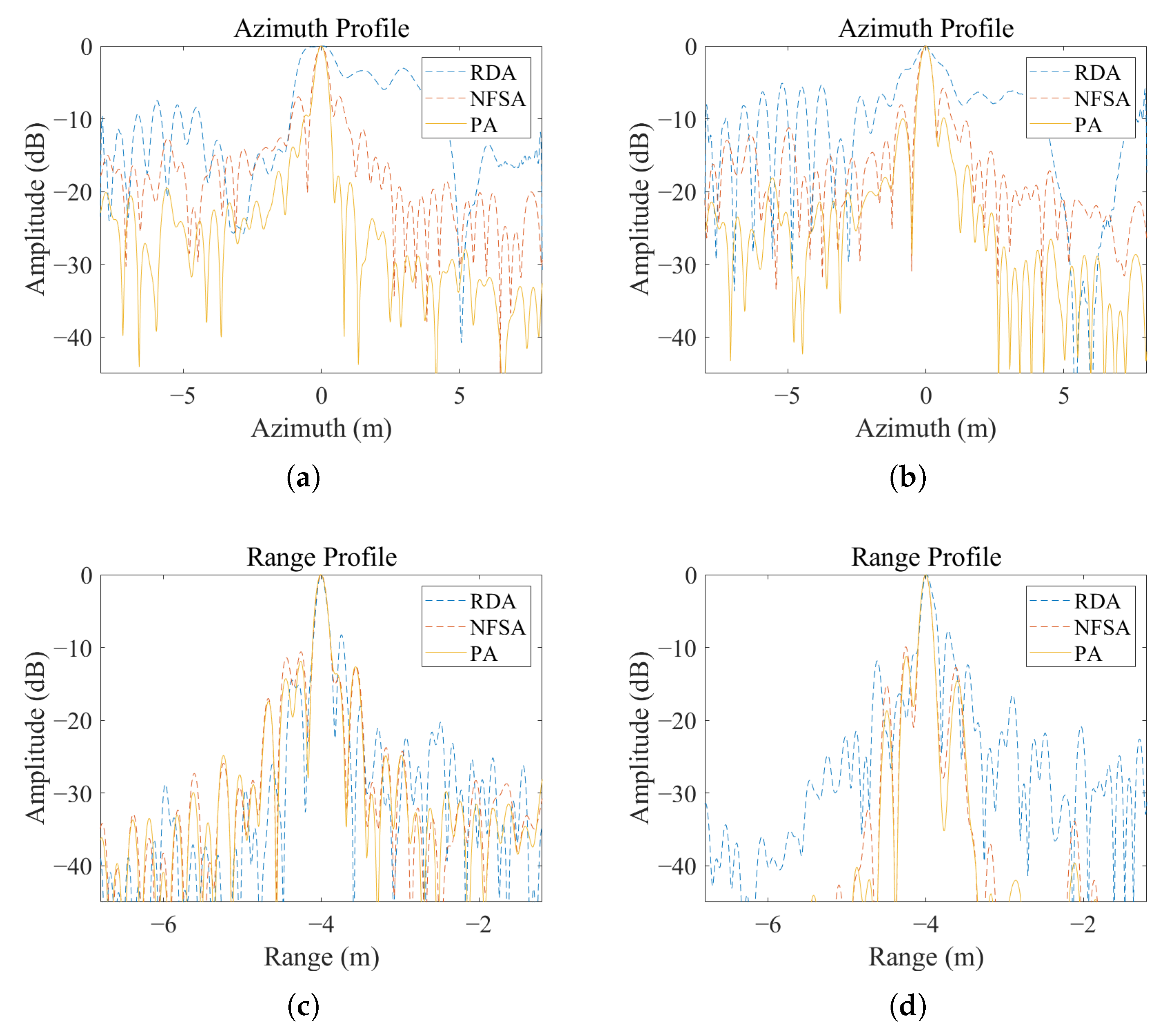

| Imaging Result of RDA (A/B) | Imaging Result of NFSA (A/B) | Imaging Result of the Proposed Algorithm (A/B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRW (m) | Range | 0.42/0.41 | 0.37/0.36 | 0.36/0.35 |

| Azimuth | 1.41/1.12 | 0.42/0.43 | 0.41/0.42 | |

| PSLR (dB) | Range | −7.65/−8.23 | −9.90/−10.58 | −11.22/−11.90 |

| Azimuth | −3.40/−3.23 | −6.91/−5.79 | −9.47/−9.99 | |

| ISLR (dB) | Range | −8.54/−8.93 | −9.22/−9.36 | −9.13/−9.64 |

| Azimuth | −3.81/−3.47 | −6.23/−6.92 | −7.29/−7.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Yi, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H.; Deng, B.; Yang, Q. Terahertz Squint SAR Imaging Based on Decoupled Frequency Scaling Algorithm. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3685. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17223685

Wang Y, Yi J, Zhao Y, Wang H, Deng B, Yang Q. Terahertz Squint SAR Imaging Based on Decoupled Frequency Scaling Algorithm. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(22):3685. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17223685

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yuang, Jun Yi, Yuzheng Zhao, Hongqiang Wang, Bin Deng, and Qi Yang. 2025. "Terahertz Squint SAR Imaging Based on Decoupled Frequency Scaling Algorithm" Remote Sensing 17, no. 22: 3685. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17223685

APA StyleWang, Y., Yi, J., Zhao, Y., Wang, H., Deng, B., & Yang, Q. (2025). Terahertz Squint SAR Imaging Based on Decoupled Frequency Scaling Algorithm. Remote Sensing, 17(22), 3685. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17223685