Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A new state-space denoising approach for the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) spherical harmonic solutions suppresses striping more effectively than conventional DDK3/4 filters while preserving geophysical signals. Combined with a generalized three-cornered hat uncertainty analysis, it ranks alternative solutions and selects an optimal estimate of total water storage and groundwater.

- A mechanistic climate linkage shows a 2–3-month lag from El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) to precipitation and total water storage anomalies. In California’s Central Valley, precipitation explains ≈65% of groundwater variability. Extremes are quantified: two prolonged droughts (2008, 2013) caused ≈91.45 km3 groundwater loss, whereas the 2006 flood replenished ≈19.81 km3.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The lagged ENSO–water storage relationship supports earlier, more reliable drought outlooks and operational groundwater monitoring, with fewer false alarms due to improved denoising and quantified uncertainty.

- Quantified losses with uncertainty bounds provide actionable benchmarks for water allocation, managed aquifer recharge, and drought mitigation in the Central Valley; the workflow is transferable to other basins.

Abstract

To mitigate the impact of north–south strip errors inherent in Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) spherical harmonic coefficient solutions, this research develops a state-space model to generate a more robust solution. The efficacy of the state-space model is demonstrated by comparing its performance with that of conventional filtering methods and hydrological modeling schemes. The method is subsequently applied to estimate the GRACE Groundwater Drought Index in the California Central Valley basin, a region significantly affected by drought during the GRACE observation period. This analysis quantifies the severity of droughts and floods while investigating the direct influences of precipitation, runoff, evaporation, and anthropogenic activities. By incorporating the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, the study offers a detailed causal analysis and proposes a novel methodology for water resource management and disaster early warning. The results indicate that a moderate-duration flood event in 2006 resulted in a recharge of 19.81 km3 of water resources in the California Central Valley basin, whereas prolonged droughts in 2008 and 2013, lasting over 15 months, led to groundwater depletion of 41.53 km3 and 91.45 km3, respectively. Precipitation and runoff are identified as the primary determinants of local drought and flood conditions. The occurrence of ENSO events correlates with sustained precipitation variations over the subsequent 2–3 months, resulting in corresponding changes in groundwater storage.

1. Introduction

Drought, one of the most pervasive natural disasters, exerts profound and far-reaching impacts on the natural environment because of its prolonged duration, frequent recurrence, and extensive spatial extent. It can be defined as a severe and persistent water shortage over a large region, often arising from anomalous weather conditions and imbalances between regional water supply and demand [1]. Drought typically develops in areas experiencing below-normal precipitation for extended periods, ranging from several months to multiple year [2]. Groundwater, whose cumulative global volume exceeds the combined storage of reservoirs, rivers, and lakes, serves as a vital water resource for much of the world’s population [3]. Consequently, the preservation and responsible management of groundwater resources are of paramount importance. However, rapid groundwater depletion in recent decades has intensified the occurrence and severity of regional drought events [4].

Multiple studies have revealed substantial groundwater depletion in California’s Central Valley (CCV), though the estimated magnitudes vary depending on data sources and methodologies. Using GRACE satellite observations, Famiglietti et al. (2011) estimated a groundwater loss of about 20 km3 from October 2003 to March 2010 [5], while Scanlon et al. (2012) reported a cumulative depletion of approximately 80 km3 since the 1960s, mainly concentrated in the southern Tulare Basin [6]. In contrast, Xiao et al. (2017), based on a combined GRACE and water balance approach, estimated groundwater losses of 16.5 km3 during 2007–2009 and 40.0 km3 during 2012–2016 [7]. The extreme drought events in the California region in 2014 intensified the pre-existing drought situation from 2012 to 2013. Over three consecutive years, these significant drought events surpassed the severity of the droughts of 1976–1977 and the late 1980s, representing the most severe drought event in the region within at least the last millennium [8]. Continuous high temperatures and limited rainfall are key factors that contribute significantly to the frequent occurrence of drought events in the California region [9], resulting in a cascade of impacts affecting rangelands [10], forests [11,12], groundwater [13,14,15,16], agriculture and socioeconomics [17].

Accurate and reliable drought monitoring is essential for assessing drought severity and for implementing effective strategies for mitigation, resilience, and prevention. Numerous indices are also available for drought detection. The Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) is often used in meteorological drought monitoring [18,19]. The Standardized Groundwater level Index (SGI) builds on the SPI to account for differences in the form and characteristics of water table and precipitation time series. The SGI is estimated using a nonparametric normal fraction conversion of water table data for each calendar month [20]. The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) is based on precipitation and temperature data, and its strength lies in the combination of multi-scale characteristics with the ability to include temperature changes in the assessment of drought impacts [21]. The Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) was first proposed by Palmer (1965) as a monitoring tool for agricultural droughts in the USA, using historical records of precipitation and temperature to calculate surface water balances [22,23,24].

While such indices can effectively indicate the drought severity within a region over a specific period, they provide limited insight into the underlying causal mechanisms. The El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) refers to a large-scale climate phenomenon characterized by anomalously warm sea surface temperatures (SST) in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. A decadal variability associated with ENSO, termed the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), influences the global mean temperature on a decadal scale and plays an important role in climate prediction. Hallack-Alegría et al. [25] analyzed precipitation variability in the semiarid Guadalupe River Basin of northwest Baja California, Mexico, and demonstrated that ENSO-related SST patterns are significant predictors of seasonal precipitation. They further applied the Standardized Precipitation Index and regional L-moment frequency analysis to assess drought characteristics, providing useful tools for drought monitoring and management in the region [25]. Wang et al. [9] reported that the dipole-like atmospheric circulation observed over California’s Central Valley was not directly driven by typical ENSO or PDO phases. Instead, it appeared to be linked to an early-stage ENSO-related anomaly—a so-called precursor signal—that may play a role in modulating regional atmospheric dynamics [9]. By analyzing large ensembles and multi-model simulations, Yoon et al. predicted that severe droughts and transitional flooding will increase by at least 50% in the California region by the end of the 21st century, and that extreme water cycling is strongly associated with enhanced ENSO [26]. It is evident that ENSO is intricately linked to droughts in California. Quantifying this relationship has increasingly become a focal point of scientific research, as understanding the extent and nature of ENSO’s influence is essential for improving regional climate predictions and enhancing drought and flood risk management strategies.

The Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellite mission has been widely used to investigate variations in terrestrial water storage anomalies (TWSA), mass changes in the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets, and fluctuations in eustatic sea level [26,27,28,29,30,31]. The spherical harmonic (SH) coefficient inversion method has been widely applied and extensively studied in the field of terrestrial mass redistribution. However, the inversion results are inevitably affected by various factors, including the inherent limitations in the design of the GRACE satellite orbits, errors in background models, and the finite accuracy of satellite instrumentation [32,33]. As a result, the mass change estimates derived directly from Level-2 SH coefficients do not fully represent the true terrestrial mass variations. Therefore, post-processing techniques such as noise reduction and stripe removal are necessary. Kusche introduced a regularization approach that considers the temporal correlation between adjacent months in GRACE Level-2 data. This method, known as the Decorrelation and Denoising Kernel (DDK), has been demonstrated to outperform traditional Gaussian filtering [34]. Wang et al. pointed out that the error magnitude in GRACE data is reflected in the covariance matrix and applied stochastic filtering techniques to effectively separate the true gravity signal from striping noise [35]. Building on this work, Wang et al. further implemented Kalman filtering for destriping and proposed a multi-factor fitting method to correct leakage errors caused by the truncation of SH coefficients [36]. Qian et al. extended the traditional DDK method by proposing two enhanced techniques: sparse DDK and adaptive DDK [37,38]. The former employs L1-norm regularization, while the latter automatically determines optimal filtering parameters based on individual months.

Compared with these approaches, the JPL-mas solution offers a stable, pre-regularized estimate of terrestrial water storage anomalies; however, its strong spatial smoothing inevitably restricts the detection of localized hydrological variations. To address this limitation, a state-space-model-based denoising method is adopted, which differs from previous Kalman filtering approaches by defining the state vector solely with true geophysical spherical harmonic coefficients, deriving its covariance matrix from a power-law model, employing the full error covariance of the SH coefficients as the observation covariance, and selecting the smoothed solution as the final model output. Regardless of the specific inversion method used, the estimation of regional terrestrial mass variations inevitably involves a certain degree of bias. Therefore, this study applies the Generalized Three-Cornered Hat (GTCH) method to quantitatively evaluate the magnitude and uncertainty of all candidate TWSA solutions. The solution with the lowest error and highest reliability is ultimately selected for the calculation of drought and flood indices. Previous studies employing state-space models have faced notable limitations, either due to inherent methodological deficiencies or the persistence of excessive noise residuals. Nevertheless, these shortcomings underscore the necessity of developing more robust approaches to improve the reliability and interpretability of the results. In summary, this study proposes a novel state-space modeling approach to estimate terrestrial water storage variations in California’s Central Valley. Based on the selected GRACE-derived TWSA and the water balance equation, non-groundwater components are removed and seasonal variations are excluded. The result is standardized to derive the GRACE Groundwater Drought Index (GGDI) [39]. In comparison with the ENSO results, the study provides a plausible explanation of the underlying causes of drought events in California’s Central Valley. The major acronyms employed in the manuscript are summarized in Table 1, and the overall research framework is illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 1.

The collected data type, name, years, sources, and explanation in this study.

Figure 1.

Research process flowchart.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

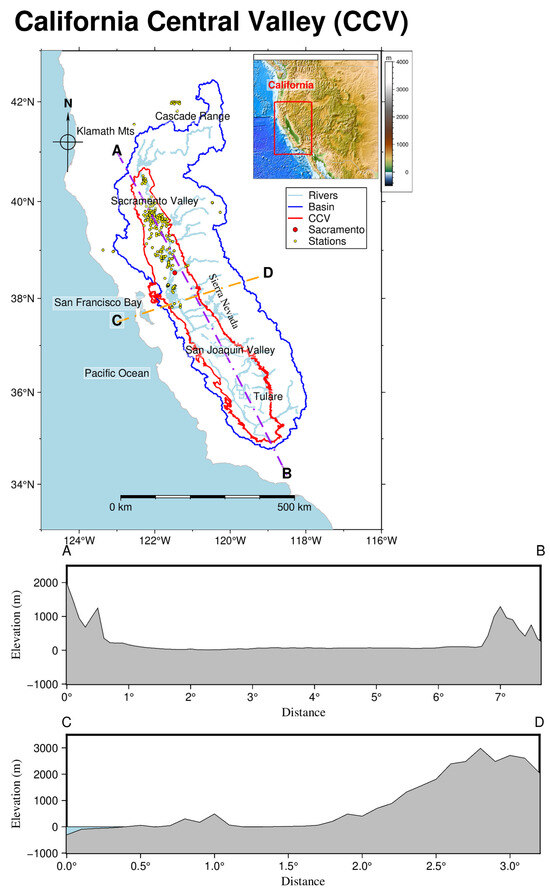

The Central Valley, also known as the Great Valley of California, covers an area of some 52,000 km2 and is one of the more prominent structural depressions in the world. It occupies the heart of California with the Cascade Mountains to the north, the Sierra Nevada to the east, the Tehachapi Mountains to the south and the Coastal Mountains and San Francisco Bay to the west and the valley is a huge agricultural area. As shown in Figure 2, the study area covers a vast region, with elevations rising from sea level up to a maximum of 4374 m. The valley can be divided into two main parts, with the northern third known as Sacramento Valley and the southern two-thirds of San Joaquin Valley divided into the San Joaquin Basin and the Tulare Basin [13,40]. Selection of four points (Figure 2) in the approximate north–south and east–west directions to plot the contour changes shows that the magnitude of elevation change in the north–south direction of the CCV is small, while the east–west direction shows a gradual climbing trend from west to east [41]. Figure 2 was plotted using GMT (v6.5.0, Generic Mapping Tools).

Figure 2.

Study area and its elevation changes in AB and CD directions.

The valley belongs to a semi-arid area, and the available surface water content is very limited. The generation of crops precisely requires abundant surface water and groundwater, so the local area must extract a large amount of groundwater to meet irrigation needs, which often leads to a rapid decline in groundwater levels. The relevant departments must timely grasp real-time data on groundwater subsidence to resist natural disasters caused by groundwater level decline [42].

2.2. Data

The Center for Space Research at the University of Texas (CSR) currently only publishes covariance matrices for the Release Level (RL)05 spherical harmonic (SH) coefficient solutions, so the RL06 data were not selected for processing. These 136 months (April 2002–June 2014, contains missing months) of data are sufficient to verify the performance of the State Space Decorrelation and Denoising Kernel (SS-DDK) method. The data were pre-processed as follows: the C20 coefficients were replaced by the satellite laser ranging results [43], the first-degree coefficients of the geocenter were estimated from the combined GRACE satellite and ocean model, glacial isostatic adjustment (GIA) was performed using the ICE-6G_D model, and the forward-modeling method approach was used for leakage error reduction [44]. Moreover, taking into account the presence of 11 missing months in the GRACE monthly SH, the cubic spline method was applied for interpolation. The Decorrelation and Denoising Kernel (DDK) 3 and 4 filters were selected for comparison with the SS-DDK, and Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) releases mascon v02 (JPL-mas) was chosen as a reference object (Table 1).

The GLDAS simulates satellite and ground-based observations using four land surface models, namely Noah, Mosaic, Community Land Surface Model (CLSM), and Variable Infiltration Capacity (VIC) [45]. Due to its superior performance in simulating soil moisture dynamics and its closer representation of actual hydrological responses, the CLSM was selected for use in this study. Detailed information on the precipitation products, along with the series of indicator factors described above, is provided in Table 1. The WaterGAP Global Hydrology Model (WGHM) provides large-scale gridded hydrological products. In this study, the WGHM data were used as an auxiliary hydrological reference to evaluate the consistency of GRACE-derived terrestrial water storage anomalies. The Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) provides monthly precipitation data with a spatial resolution of 0.25°, which was used to capture regional precipitation variability and to validate the temporal evolution of water fluxes.

2.3. Methods

The state space modeling framework aims to suppress north–south striping noise and correlated errors inherent in GRACE spherical harmonic solutions. By representing the time-varying gravity field as a dynamic system, it enables optimal filtering and temporal smoothing while preserving physically consistent hydrological signals, thereby yielding more robust estimates of terrestrial water storage anomalies than conventional decorrelation filters. First, we discuss how to perform state space modeling of the GRACE SH solutions, followed by the uncertainty estimation using GTCH for each alternative solution, and finally we introduce the assessment index for drought or flood events.

- (1)

- State-space modeling

The SH coefficient , which represents the true geophysical signal in kth month, is the variable to be estimated, and is the SH coefficients provided by CSR RL05. The observation model of the SS-DDK is represented as follows.

The observation matrix is the identity matrix. denotes the observation error covariance matrix. The observation error generally includes high-frequency error and strip noise, and statistical information of is included in . Therefore, it is unnecessary to manually specify the strip-noise statistics, which simplifies model implementation and enhances the reliability of the estimation. This represents the main difference between the SS-DDK approach proposed in this study and previous method [35,36].

The state transition equation (process model) is expressed as follows.

In this formulation, the state transition matrix is the identity matrix. represents process noise and denotes the process noise covariance matrix. The parameter α is a variance component factor used to scale the process noise covariance, with a constant value adopted for all months. (For further details, please refer to [46].) GRACE primarily observes large-scale mass variations, which are typically represented by low-degree SH coefficients, whereas high-degree coefficients correspond to small-scale variations or noise-dominated signals with relatively low natural variability. As a result, the process noise covariance decreases rapidly with an increasing degree, following a power-law decay () [47,48]. Consequently, the matrix is diagonal, represents the degree of spherical harmonic coefficient, and denotes a power exponent.

Given these modeling parameters, Kalman filtering or smoothing is generally applied to obtain the optimal state vector estimation [49]. The standard equations of the Kalman filter are formulated as follows.

Variables with ^ represent the estimated value of the corresponding variables. The initial value is set to , and the initial covariance matrix is empirically chosen to be diagonal and sufficiently large to reflect the uncertainty associated with the initial estimate. Notations such as represent the estimated value of using all available observations up to the jth epoch. The matrix denotes the Kalman gain matrix.

Rauch–Tung–Striebel (RTS) smoothing is one of the most commonly used fixed intervals smoothing methods, and the equation is as follows [50].

Here, denotes the Kalman smoothing gain matrix, and represents the cross-covariance matrix between and . With initial values and obtained directly from the Kalman filter solution, the following equation is obtained.

According to Equation (11), the matrix is positive semi-definite, indicating that the nominal uncertainty of the smoothed estimate is smaller than that of the filtered estimate . Therefore, the RTS smoothing result is adopted as the final state-space solution of the SS-DDK mode [46].

- (2)

- Uncertainty analysis

The GTCH method is employed to quantify the uncertainty of GRACE-derived terrestrial water storage anomalies. It extends the classical Three-Cornered Hat approach by accounting for correlated errors among multiple solutions, thereby providing a statistically consistent estimation of individual model uncertainties without requiring a priori error information. The GTCH method was employed to estimate the uncertainty associated with each type of solution. Before estimating the uncertainty of the solutions, the TWS time series was preprocessed by subtracting its mean over the period 2004–2009 to obtain the TWSA series. The magnitude of uncertainty for all alternative solutions is estimated using the GTCH method. Using (the number of alternative solutions, n = 6) to represent the various different solutions, each observation sequence can be expressed as,

denotes the true signal and ε is the error of the observed sequence. Since the true value is not available, either observation series is chosen as the reference value [51,52,53].

In this paper, the TWSA calculated from the JPL-mas solution is chosen as the reference field. The difference series is obtained by subtracting the inversion results of other products from the reference value, and the covariance matrix of the difference series is calculated. The constraints are iteratively applied to obtain the solution that minimizes the objective function, and this solution is then used as the estimate of uncertainty [54,55,56].

- (3)

- GRACE Groundwater Drought Index (GGDI)

Groundwater storage variations are estimated using the water mass balance equation, which integrates multiple auxiliary datasets to isolate the groundwater storage signal from total water storage variations. It is assumed that total water storage anomalies (TWSA) consists of variations in several hydrological components, including soil moisture anomalies (SMAs), snow water anomalies (SWAs), canopy water anomalies (CWAs), reservoir storage anomalies (RSAs), and groundwater storage anomalies (GWSAs). Accordingly, GWSA can be expressed as,

To eliminate the seasonal influence on groundwater storage changes, the monthly climatological mean of GWSA is removed so that each GWSA value represents the deviation from the mean of its corresponding calendar month:

where i and j represent year and month indexes, respectively (j = 1, 2, 3, … 12). The standardized groundwater storage deviation (GSD) is then computed by subtracting its mean and dividing by its standard deviation,

where μ and σ denote the mean and standard deviation of GSD, respectively. The rankings of drought or flood events corresponding to the GGDI are obtained as shown in Table 2 [39,57].

Table 2.

Classification standardized for drought and flood levels of GGDI.

- (4)

- Terrestrial water storage anomalies change (TWSAC)

The change in TWSA between consecutive months can be estimated in two ways. The first approach derives the inter-monthly TWSA difference directly from GRACE observations, whereas the second applies the water balance equation, in which total hydrological inputs over time are subtracted from total outputs to obtain the regional water storage change between adjacent months. For the GRACE-based approach, the TWSA change (TWSAC) is computed as,

where jth represents month indexes (j ≥ 2). Alternatively, the water balance equation can be expressed as,

where the terms on the right-hand side represent total precipitation (P), actual evapotranspiration (ET), discharge (Q) into oceans, lakes, etc., and actual water consumption (WC), respectively [58].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Geoid Degree Error and Time Series Analysis

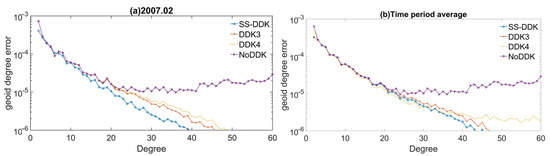

To evaluate the relative contributions of signal and noise in the GRACE-derived TWSA, spherical harmonic (SH) analysis is performed to obtain degree variances of the SH coefficients. The degree variance reflects the average signal power associated with each SH degree, enabling assessment of the transition from signal-dominated to noise-dominated components. Typically, lower degrees (below 20) capture large-scale hydrological signals, while higher degrees (above 30) are dominated by noise [59,60]. Figure 3 presents the degree variance spectra for both unconstrained and constrained solutions, using February 2007 and the temporal average over the study period as examples. The results indicate that the proposed SS-DDK approach effectively preserves low-degree hydrological signals while exhibiting superior suppression of high-degree noise compared to the DDK3 and DDK4 filters.

Figure 3.

Geoid degree error of unconstrained and various constrained solutions in February 2007 and averaged over the whole study period.

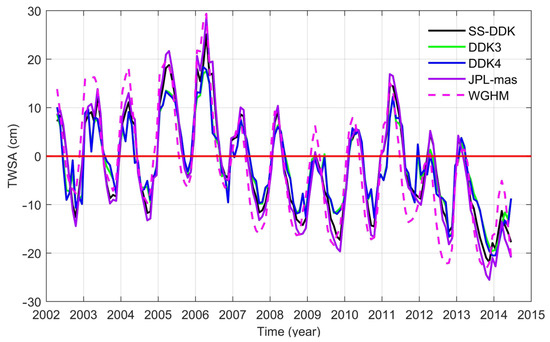

The above shows the performance of some of the alternative solutions in terms of signal and noise, but it is the annual variations and trends in TWSA that are the focus of this study. Figure 4 illustrates the temporal trends of all alternative TWSA solutions, from which the consistency among the different estimates can be clearly observed, and statistically obtained root mean square error (RMSE) and correlation coefficients are shown in Table 3; meanwhile, the TWSA time series are fitted to obtain the Mean Annual Amplitude (MAA) and phase changes (PCs).

Figure 4.

Time series plots of all solutions over the entire study period (the solid red line indicates the zero-horizontal line).

Table 3.

Statistical information on alternative solutions.

The WGHM is a global water balance model that integrates surface and subsurface hydrological processes to estimate total water storage changes. In this study, the WGHM-derived TWSA is used as an independent hydrological reference to validate the GRACE-based estimates. As shown in Figure 4 and Table 3, the WGHM results exhibit similar temporal variations to the GRACE-based solutions, though with a slightly larger amplitude due to model-driven runoff and evaporation parameterizations. Using the JPL-mas solution as the reference value, the state space model solution has the lowest RMSE and the highest correlation coefficient, and is closer to the reference value in terms of the anniversary amplitude and phase, highlighting its performance advantages in preserving signal strength and removing noise. Overall, the SS-DDK solution is found to be closer to the reference value and to have a smaller error.

3.2. Uncertainty Analysis and RMSE

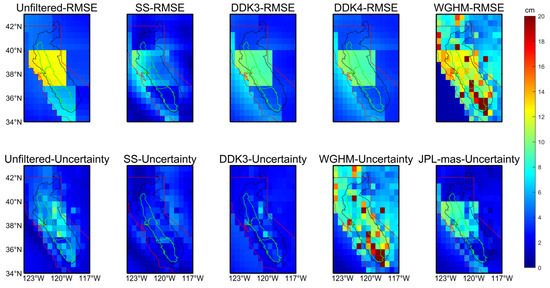

Using the GTCH method, it is possible not only to count the uncertainty in the total TWSA of the region, but also to estimate the magnitude of the uncertainty in each grid (Figure 5) point individually, as is the case for the calculation of the RMSE (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Grid uncertainty and RMSE of alternative solutions (Uncertainty: The respective error variances between multiple independent time series. The red line indicates the California border, the light green lines represent the Central Valley core area, and the black line is the study area).

The SS-DDK solution is dominant in terms of uncertainty magnitude and RMSE at almost all grid points. Focusing on the uncertainties of the SS-DDK and JPL-mas solutions, the former has a smaller uncertainty while having a similar ability to represent TWSA changes as the latter. This is the significance of the state space modeling approach proposed in this paper to deal with GRACE data.

3.3. TWSAC Analysis

By incorporating multi-source datasets, the performance of the state-space model is further assessed using the water balance equation. Precipitation in the water balance equation is derived from TRMM, and the variables Q, ET, and WC are from WGHM. Table 4 examines both the CCV basin as a whole and in chunks, separately counting the differences between the results of the time-series differences in all alternative solutions and the solutions to the water balance equation. Figure A1 highlights the convergence of the two approaches in terms of time series.

Table 4.

Differences between the two methods for solving TWSAC.

In the TWSAC dimension, the SS-DDK solution is essentially identical to the JPL-mas correlation and RMSE. For the study area chunking statistics, SS-DDK similarly demonstrated superior performance to DDK3-4 filtering. Especially when SS-DDK expressivity is comparable to mascon and possesses better stability, in comparison with the DDK3-4 filtering approach, the state-space model proves to be more suitable for assessing TWSA in the CCV basin. The water balance approach is employed as an auxiliary comparison to evaluate the temporal consistency of the SS-DDK results. Given that water balance estimates are subject to large uncertainties, particularly in water consumption. This comparison is intended only to assess general correspondence rather than to quantitatively rank model accuracy.

3.4. GGDI Analysis

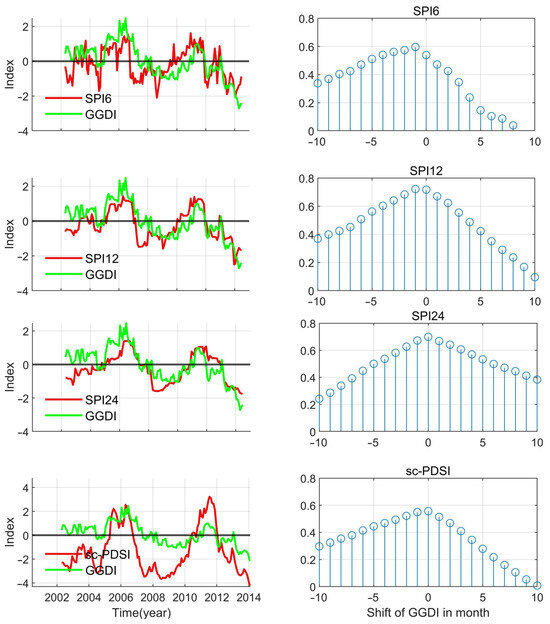

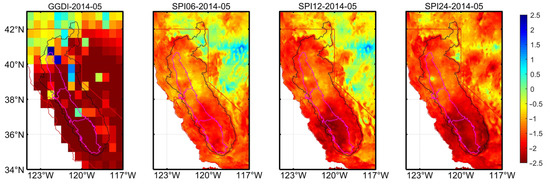

To assess the agreement between GGDI and established hydro-climatic indices and to summarize flood and drought characteristics over the study period, we compared GGDI with SPI (at multiple accumulation scales) and sc-PDSI. As shown in Figure 6, GGDI exhibits positive and statistically meaningful correlations with these indices: all pairwise correlations exceed 0.55, and the correlations with SPI-6, SPI-12, and SPI-24 reach ≥ 0.60. Event counts, durations, and severities derived from the adopted classification scheme are summarized in Table 5.

Figure 6.

Time-series plots of indexes (the left column), leading or lagging correlation coefficients (the right column), “Shift of GGDI in month”: “Lag applied to GGDI (months)” (positive = GGDI lags; negative = GGDI leads). The black line represents the bold zero-level line.

Table 5.

Peak and total groundwater changes during several moderate or greater flood and drought events.

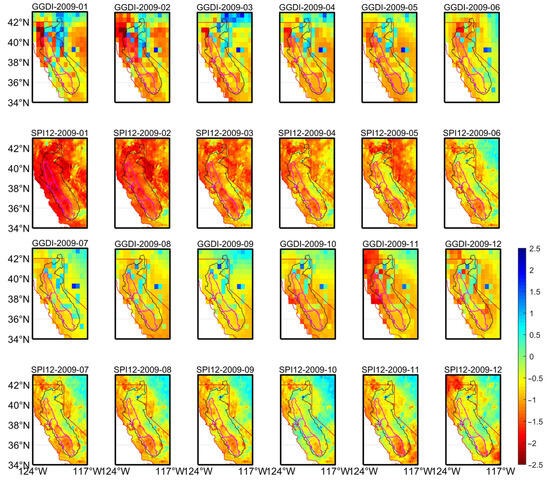

There were two moderate or greater drought events between April 2002 and June 2014, and both sustained events lasted more than 15 months. The first drought event persisted for up to 20 months (see Table 5 for details), whereas the second event, although shorter in duration, led to a groundwater depletion of 91.45 km3, with a peak groundwater deficit of up to 8.81 km3 in a single month, which is consistent with the results of previous studies [7]. Prior to 2007, there was a flooding event that lasted approximately 9 months and resulted in nearly 19.81 km3 of local groundwater recharge in CCV basin. Figure A2 and Figure A3 highlight the ability of the GGDI to describe the magnitude of a drought or flood event in terms of an entire year and a single month, respectively. Although the spatial resolution of the GGDI is not fine enough, it is perfectly adequate for the detection of large regions and drought events of moderate or higher magnitude.

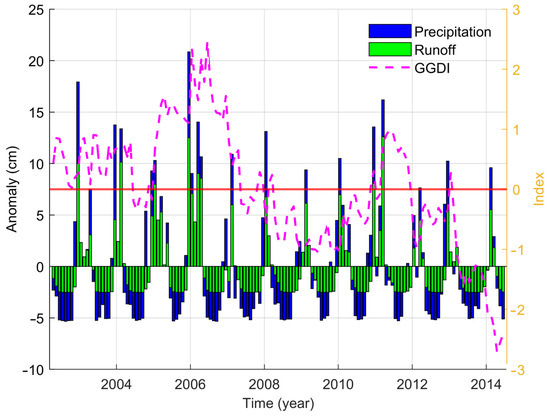

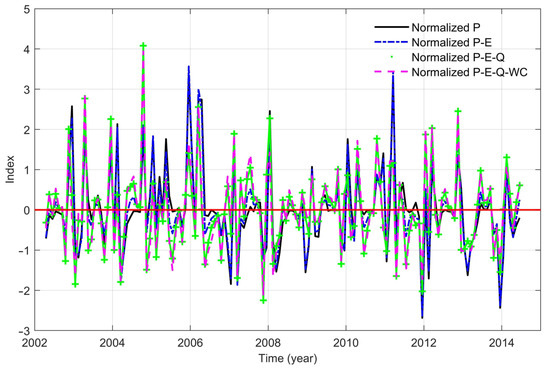

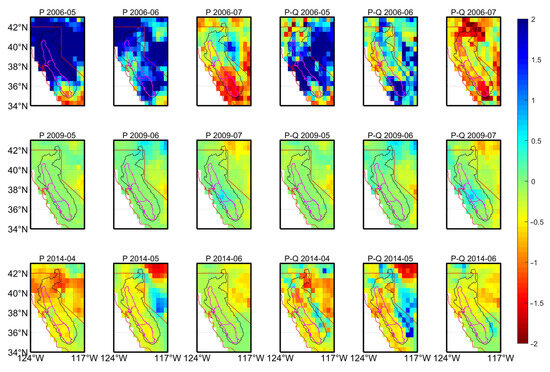

3.5. Direct Factors in Flood and Drought Events

The most likely cause of directly induced flooding and drought events is changes in precipitation, evapotranspiration, or runoff over a period of time in an area. Figure 7 easily identifies high-intensity increases or decreases in precipitation anomalies and runoff anomalies around 2006 and 2014, coinciding with large-scale flood or drought events during the time period, enough to suggest that in the CCV basin precipitation and runoff variability is a direct cause of regional groundwater surpluses or deficits. The normalized precipitation index and the precipitation residual (precipitation minus ET, Q, and WC) are shown in Figure 8, following the same processing steps as those applied to GGDI, where each monthly series is de-seasonalized by subtracting its climatological mean and then standardized by dividing by its standard deviation. Deducting ET or WC from precipitation and runoff only, the correlation between pre and post removal maintains above 0.99, which once again validates that P and Q are the most significant contributors to natural hazards. Months with increased precipitation had a corresponding increase in runoff. The trends of all folds are generally consistent with those of precipitation, side by side indicating that precipitation plays a dominant role in flood and drought events. The spatial variation in the precipitation index and its associated indexes for selected periods of the 2006 flood and the 2009, 2014 drought shown in Figure 9. Runoff mitigates the regional flooding phenomenon to some extent, whereas during a drought, changes in runoff have a negligible effect on the drought event.

Figure 7.

Precipitation anomaly, runoff anomaly and GGDI time series. (Anomaly in precipitation and runoff correspond to the left vertical axis, while GGDI values correspond to the right vertical axis). The red line represents the zero-level reference line of the index.

Figure 8.

Normalized precipitation series indicators. (“P-E” represents precipitation with evapotranspiration subtracted; “P-E-Q” represents precipitation with evapotranspiration and runoff subtracted; “P-E-Q-WC” represents precipitation with evapotranspiration, runoff, and water consumption subtracted). The red line represents the zero-level reference line of the index.

Figure 9.

Precipitation index and deduction of runoff index for key time periods.

Based on the event-phase analysis summarized in Table 5, runoff exhibits a noticeable moderating effect during flood periods, whereas its influence under drought conditions is comparatively minor. This finding suggests that runoff primarily contributes to the short-term regulation of flood responses, while its role in drought evolution remains limited.

3.6. Deeper Mechanisms of Flood and Drought

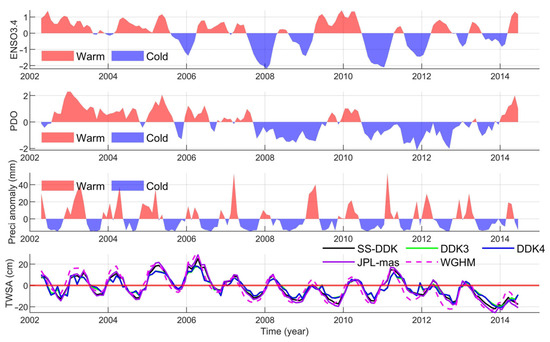

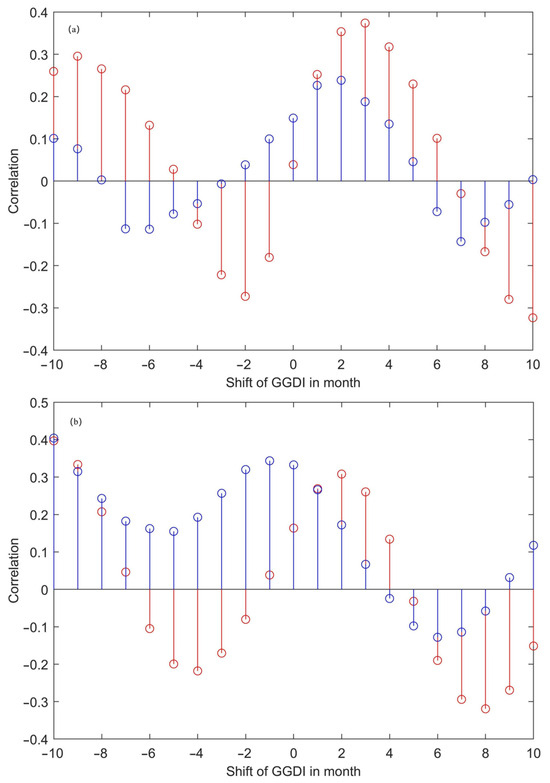

The discussion in the previous section identified precipitation variability as the dominant factor influencing regional drought or flooding. The CCV basin is close to the Pacific Ocean, and during the El Niño phase, the sea surface temperature (SST) in the Pacific Equatorial Zone increases, inducing changes in the atmospheric circulation pattern and leading to increased precipitation in the coastal areas. To visualize the effect of SST changes on regional precipitation, ENSO3.4 and PDO were read and plotted directly, and the relationship with precipitation and TWSA was calculated in Figure 10 and Figure A4. Both have a 2–3-month delay relative to ENSO3.4, precipitation is similarly delayed by 2 months compared to the PDO, and TWSA is essentially in phase with the PDO. The correlation between precipitation without lag and ENSO3.4 reaches 0.37, highlighting that ENSO is a major underlying factor influencing regional precipitation variability. The correlations of TWSA time series based on SS-DDK with ENSO3.4 and PDO are above 0.3, which laterally indicates that ENSO directly brings about the addition or reduction in regional precipitation, which leads to the change in surface water storage, and ultimately the formation of localized drought or flooding phenomena.

Figure 10.

Indicator series and TWSA time series.

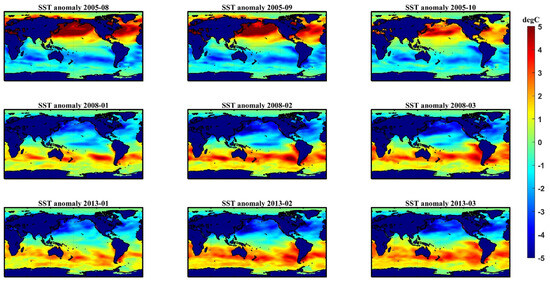

Figure A5 shows the global SST anomalies for three consecutive months prior to the drought and flood events counted in this paper, and the persistence of El Niño and La Niña events in the waters around the CCV basin provides an additional piece of supporting material for the mechanistic inquiry of drought and flood.

3.7. Limitation of This Work

The ability to characterize droughts or floods is constrained by the size of the region because the spatial resolution of the surface that can be inverted by GRACE itself is too coarse, and the leakage of the signal is even worse in regions close to the ocean, which creates a considerable problem for inverting surface material migration. Although the state-space model is chosen in this paper to obtain a smoothing solution with higher accuracy, it is clear from the analysis of the actual situation that the parameter α for each month is time-varying, and simply fixing α to a single value seems to be not reasonable enough. There are various types of right-hand end components of the water balance equation (as shown in Equation (20)), and the solutions obtained by selecting different components for the calculations vary.

Future work should incorporate in situ groundwater-well observations to better validate and refine the model estimates. Recent studies, such as Stevens et al. (2025), have demonstrated that combining GRACE-derived estimates with in situ water level data can significantly improve the characterization of groundwater storage changes in the Central Valley [61]. Building on this insight, subsequent research will integrate well-based observations to calibrate the state-space model and improve the reliability of the drought and flood assessments. Furthermore, once the covariance matrices associated with the GRACE CSR RL06 spherical harmonic coefficients become publicly available, we plan to conduct additional experiments using these updated datasets to further verify and refine the proposed framework.

4. Conclusions

Considering the advantages of state-space modeling for spatio-temporal GRACE data processing, we adopt an RTS smoothing-based implementation (SS-DDK) in place of the standard Kalman filter to more effectively attenuate striping and high-frequency errors. Comprehensive evaluations demonstrate that SS-DDK outperforms DDK3-4 and WGHM in terms of geoid degree error, RMSE, time-series fit, and uncertainty, while remaining comparable to JPL-mas. Leveraging multivariate data within a water-balance framework, we further assess the TWSA consistency across the three sub-areas of the CCV basin; the SS-DDK solution exhibits the highest degree of compliance among all alternatives, reinforcing both the reliability and interpretability of the proposed approach for regional hydrological analyses.

Building on the SS-DDK estimates, we identify three major drought/flood events in the CCV basin and, in combination with the GGDI, quantify their magnitudes. Two prolonged droughts lasting more than 15 months occurred around 2008 and 2013; the latter actually began in 2012, with a peak monthly groundwater loss of 8.81 km3 and a cumulative groundwater loss of 91.45 km3 by June 2014. These results highlight the capability of the SS-DDK framework, together with GGDI, to detect event timing and intensity at the basin scale, and to characterize groundwater depletion dynamics during multi-year droughts. From the perspective of local hydro-climatic drivers, and after accounting for evapotranspiration and other water-balance terms, precipitation and runoff are confirmed to be the primary controls of drought and flood conditions in the CCV, consistent with widely recognized hydrological understanding. Comparisons between ENSO time series and global grid maps indicate that ENSO variability particularly modulates coastal precipitation; a typical ~2–3-month lag is observed between ENSO anomalies and precipitation increases along the U.S. West Coast, which subsequently promotes regional groundwater recharge. Although the identified drought and flood events in the Central Valley are consistent with known hydrological records, the SS-DDK framework provides additional scientific value beyond event detection. It enables more precise quantification of groundwater depletion and recovery magnitudes, reduces striping and correlated errors compared with conventional GRACE filtering methods, and rigorously propagates uncertainty through the state-space formulation. Moreover, by linking the filtered TWS anomalies with climate indices, the method reveals lagged cause–effect relationships (e.g., ENSO–precipitation–groundwater) that are less discernible in traditional datasets. These capabilities collectively enhance the reliability of GRACE-based hydrological interpretation and provide a transferable framework for drought monitoring and groundwater management in other regions.

Notwithstanding these advances, the coarse native resolution of GRACE requires sufficiently large analysis areas for event attribution, and potential biases may arise from time-varying state-space parameters and uncertainties in water-balance components; these issues warrant further evaluation against in situ groundwater-well observations. Future work will relax the assumption of a constant variance-component factor (α) by allowing α to adapt over time and will incorporate tighter physical constraints and additional data sources to further strengthen the robustness and interpretability of the SS-DDK solution.

Author Contributions

Y.F.: conceptualization, methodology, software, and writing—original draft; N.Q.: data curation, formal analysis, reviewing, and editing; Q.T.: formal analysis, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation; Y.C.: data curation, writing—review and editing; Y.H.: investigation, writing—original draft preparation; Y.Z. and D.Y.: writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42504028); the Basic Research Program of Jiangsu (Grant No. BK20241665); the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. 2025QN1109, 2024ZDPYCH1003); the Graduate Innovation Program of China University of Mining and Technology (Grant No. 2025WLKXJ196); the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities; the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. KYCX25_2886).

Data Availability Statement

The GRACE monthly solutions used in this study are available through ICGEM’s official website (https://icgem.gfz-potsdam.de/home) and accessed on 20 January 2025. The JPL Mascon RL06v02 product can be obtained from https://grace.jpl.nasa.gov/data/get-data/monthly-mass-grids-land/, accessed on 20 January 2025. The WGHM v2.2d hydrological model outputs are available from https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.918447?format=html#download, accessed on 20 January 2025. The GLDAS-2.1 CLSM product can be accessed via https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datasets?keywords=GLDAS_CLSM10&page=1, accessed on 20 January 2025. The TRMM_3B43 precipitation data are available at https://disc.gsfc.nasa.gov/datasets?keywords=trmm&page=1, accessed on 20 January 2025. The other data and code presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Wei Feng for providing the GRACE MATLAB Toolbox Version 1.0.0.1 (GRAMAT), Roelof Rietbroek for DDK filtering code (https://github.com/strawpants/GRACE-filter, accessed on 11 November 2024). Thanks to W. R. Peltier for the GIA ICE-6G_D model. We are grateful to our colleagues and students for their assistance during the research and manuscript preparation. Finally, we sincerely thank the reviewers for their constructive and insightful comments that helped improve the quality of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no financial interests, commercial affiliations, or other potential conflicts of interest that could have influenced the objectivity of this research or the writing of this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GRACE | Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment |

| ENSO | El Niño–Southern Oscillation |

| SST | sea surface temperature |

| GLDAS | Global Land Data Assimilation System |

| PDO | Pacific Decadal Oscillation |

| CCV | California Central Valley |

| SH | spherical harmonic |

| TWSA | terrestrial water storage anomalies |

| DDK | Decorrelation and Denoising Kernel |

| SS-DDK | State Space Decorrelation and Denoising Kernel |

| GTCH | Generalized Three-Cornered Hat |

| GGDI | GRACE Groundwater Drought Index |

| RTS | Rauch–Tung–Striebel |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

TWSAC time series obtained for the SS-DDK variance and water balance equations, respectively. The red line represents the bold zero-level line.

Figure A2.

Grid map of GGDI and SPI6, 12, 24 for the CCV basin in May 2014.

Figure A3.

CCV basin regional grid for GGDI and SPI12 for 12 months 2009.

Figure A4.

(a) Sliding correlation between precipitation and ENSO3.4 (red), PDO (blue). (b) Sliding correlation between TWSA based on SS-DDK and ENSO3.4 (red), PDO (blue).

Figure A5.

Global sea surface temperature anomalies (Positive values for El Niño and negative values for La Niña in the Pacific).

References

- Gleeson, T.; Wada, Y. Assessing regional groundwater stress for nations using multiple data sources with the groundwater footprint. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 044010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhite, D.A.; Buchanan-Smith, M. Drought as hazard: Understanding the natural and social context. In Drought and Water Crises: Science, Technology, and Management Issues; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; Volume 3, p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, A.K.; Singh, V.P. Drought modeling—A review. J. Hydrol. 2011, 403, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholarin, E.A.; Awange, J.L. Environmental Project Management: Principles, Methodology, and Processes; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Famiglietti, J.S.; Lo, M.; Ho, S.L.; Bethune, J.; Anderson, K.J.; Syed, T.H.; Swenson, S.C.; de Linage, C.R.; Rodell, M. Satellites measure recent rates of groundwater depletion in California’s Central Valley. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, B.R.; Faunt, C.C.; Longuevergne, L.; Reedy, R.C.; Alley, W.M.; McGuire, V.L.; McMahon, P.B. Groundwater depletion and sustainability of irrigation in the US High Plains and Central Valley. Environ. Sci. 2012, 109, 9320–9325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, M.; Koppa, A.; Mekonnen, Z.; Pagan, B.R.; Zhan, S.A.; Cao, Q.A.; Aierken, A.; Lee, H.; Lettenmaier, D.P. How much groundwater did California’s Central Valley lose during the 2012–2016 drought? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 4872–4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, D.; Anchukaitis, K.J. How unusual is the 2012–2014 California drought? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 9017–9023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Hipps, L.; Gillies, R.R.; Yoon, J.H. Probable causes of the abnormal ridge accompanying the 2013–2014 California drought: ENSO precursor and anthropogenic warming footprint. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 3220–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, R.E.; Horney, M.R.; Macon, D. Update of the 2014 drought on California rangelands. Rangelands 2014, 36, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baguskas, S.A.; Peterson, S.H.; Bookhagen, B.; Still, C.J. Evaluating spatial patterns of drought-induced tree mortality in a coastal California pine forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 315, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asner, G.P.; Brodrick, P.G.; Anderson, C.B.; Vaughn, N.; Knapp, D.E.; Martin, R.E. Progressive forest canopy water loss during the 2012–2015 California drought. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E249–E255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faunt, C.C.; Sneed, M.; Traum, J.; Brandt, J.T. Water availability and land subsidence in the Central Valley, California, USA. Hydrogeol. J. 2016, 24, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.Y.; Lee, S.-I. Integration of GRACE, ground observation, and land-surface models for groundwater storage variations in South Korea. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2016, 37, 5786–5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunwar, G.; Saharia, M.; Getirana, A.; Pandey, A. Detection and socio-economic attribution of groundwater depletion in India. Hydrogeol. J. 2024, 32, 1801–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikraftar, Z.; Parizi, E.; Saber, M.; Hosseini, S.M.; Ataie-Ashtiani, B.; Simmons, C.T. Groundwater sustainability assessment in the Middle East using GRACE/GRACE-FO data. Hydrogeol. J. 2024, 32, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howitt, R.; Medellín-Azuara, J.; MacEwan, D.; Lund, J.R.; Sumner, D. Economic Analysis of the 2014 Drought for California Agriculture; Center for Watershed Sciences University of California: Davis, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, T.B.; Doesken, N.J.; Kleist, J. The relationship of drought frequency and duration to time scales. In Proceedings of the Eighth Conference on Applied Climatology, Anaheim, CA, USA, 17–22 January 1993; pp. 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, S.; Steinemann, A.C.; Lettenmaier, D.P. Drought Monitoring for Washington State: Indicators and Applications. J. Hydrometeorol. 2011, 12, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, J.P.; Marchant, B.P. Analysis of groundwater drought building on the standardised precipitation index approach. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 17, 4769–4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VicenteSerrano, S.M.; Beguería, S.; López-Moreno, J.I. A multiscalar drought index sensitive to global warming: The standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 1696–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, W.C. Meteorological Drought; US Department of Commerce, Weather Bureau: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 1965; Volume 30.

- Alley, W.M. The Palmer drought severity index: Limitations and assumptions. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 1984, 23, 1100–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, A.; Trenberth, K.E.; Qian, T. A global dataset of Palmer Drought Severity Index for 1870–2002: Relationship with soil moisture and effects of surface warming. J. Hydrometeorol. 2004, 5, 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallack-Alegria, M.; Ramirez-Hernandez, J.; Watkins, D.W. ENSO-conditioned rainfall drought frequency analysis in northwest Baja California, Mexico. Int. J. Climatol. 2012, 32, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.H.; Wang, S.Y.S.; Gillies, R.R.; Kravitz, B.; Hipps, L.; Rasch, P.J. Increasing water cycle extremes in California and in relation to ENSO cycle under global warming. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapley, B.D.; Bettadpur, S.; Ries, J.C.; Thompson, P.F.; Watkins, M.M. GRACE measurements of mass variability in the Earth system. Science 2004, 305, 503–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Luo, Z. Satellite gravity technology oriented towards data-scenario-model driven approach: Developments, challenges and outlook. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 2025, 54, 1537–1560. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Xu, C.; Jian, G.; Xu, G.; Liu, S. Unveiling North-South stripe patterns in the GRACE gravity field using dimensionality reduction. Geophys. J. Int. 2025, 242, ggaf235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Shen, Y.; Chen, Q.; Chen, J.; Geng, J. Global Sea Level Change Rate, Acceleration and Its Components from 1993 to 2016. Mar. Geod. 2023, 47, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Q.; Jürgen, M.; Wu, H.; Annike, K.; Zhong, M. Satellite gradiometry based on a new generation of accelerometers and its potential contribution to Earth gravity field determination. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 73, 3321–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahr, J.; Swenson, S.; Zlotnicki, V.; Velicogna, I. Time-variable gravity from GRACE: First results. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2004, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awange, J.L.; Sharifi, M.A.; Ogonda, G.; Wickert, J.; Grafarend, E.W.; Omulo, M.A. The falling Lake Victoria water level: GRACE, TRIMM and CHAMP satellite analysis of the lake basin. Water Resour. Manag. 2008, 22, 775–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusche, J. Approximate decorrelation and non-isotropic smoothing of time-variable GRACE-type gravity field models. J. Geod. 2007, 81, 733–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Davis, J.L.; Hill, E.M.; Tamisiea, M.E. Stochastic filtering for determining gravity variations for decade-long time series of GRACE gravity. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2016, 121, 2915–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Luo, Z.C.; Zhong, B.; Wu, Y.H.; Huang, Z.K.; Zhou, H.; Li, Q. Separation and Recovery of Geophysical Signals Based on the Kalman Filter with GRACE Gravity Data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, N.J.; Chang, G.B.; Ditmar, P.; Gao, J.X.; Wei, Z.Q. Sparse DDK: A Data-Driven Decorrelation Filter for GRACE Level-2 Products. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, N.J.; Chang, G.B.; Gao, J.X.; Shen, W.B.; Yan, Z.W. Adaptive DDK Filter for GRACE Time-Variable Gravity Field with a Novel Anisotropic Filtering Strength Metric. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.F.; Famiglietti, J.S.; Landerer, F.W.; Wiese, D.N.; Molotch, N.P.; Argus, D.F. GRACE Groundwater Drought Index: Evaluation of California Central Valley groundwater drought. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 198, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valley, S. Groundwater Availability of the Central Valley Aquifer, California; US Geological Survey Professional Paper: Reston, VA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ukasha, M.; Ramirez, J.A.; Niemann, J.D. An improved rescaling algorithm for estimating groundwater depletion rates using the GRACE satellite. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2023, 44, 1069–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strassberg, G.; Scanlon, B.R.; Chambers, D. Evaluation of groundwater storage monitoring with the GRACE satellite: Case study of the High Plains aquifer, central United States. Water Resour. Res. 2009, 45, W0541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.K.; Tapley, B.D.; Ries, J.C. Deceleration in the Earth’s oblateness. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2013, 118, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.L.; Wilson, C.R.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.Z. Reducing leakage error in GRACE-observed long-term ice mass change: A case study in West Antarctica. J. Geod. 2015, 89, 925–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodell, M.; Houser, P.R.; Jambor, U.; Gottschalck, J.; Mitchell, K.; Meng, C.J.; Arsenault, K.; Cosgrove, B.; Radakovich, J.; Bosilovich, M.; et al. The global land data assimilation system. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2004, 85, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Chang, G.; Qian, N.; Wei, Z.; Huan, Y.; Yang, Y. RTS state smoothing of GRACE Level-2 data. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 2023, 52, 1858–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gledzer, E.B.; Golitsyn, G.S. Kaula’s rule–a consequence of probability laws by AN Kolmogorov and his school. Russ. J. Earth Sci. 2019, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amitrano, D. Variability in the power-law distributions of rupture events: How and why does b-value change. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2012, 205, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D. Optimal State Estimation: Kalman, H∞, and Nonlinear Approaches; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, H.E.; Tung, F.; Striebel, C.T. Maximum likelihood estimates of linear dynamic systems. AIAA J. 1965, 3, 1445–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koot, L.; de Viron, O.; Dehant, V. Atmospheric angular momentum time-series: Characterization of their internal noise and creation of a combined series. J. Geod. 2006, 79, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.; Pan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Hou, X.Y.; Hong, Y.; Scanlon, B.R.; Longueyergne, L. Global analysis of spatiotemporal variability in merged total water storage changes using multiple GRACE products and global hydrological models. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 192, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatolazadeh, F.; Eshagh, M.; Goita, K. A new approach for generating optimal GLDAS hydrological products and uncertainties. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 730, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, F.J.; Palacio, J. Post-processing ROA data clocks for optimal stability in the ensemble timescale. Metrologia 2003, 40, S237–S244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, F.J.; Palacio, J. Estimating the instabilities of N correlated clocks. In Proceedings of the 31th Annual Precise Time and Time Interval Systems and Applications Meeting, Dana Point, CA, USA, 7–9 December 1999; pp. 285–296. [Google Scholar]

- Torcaso, F.; Ekstrom, C.R.; Burt, E.; Matsaki, D. Estimating frequency stability and cross-correlations. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual Precise Time and Time Interval Systems and Applications Meeting, Reston, VA, USA, 1–3 December 1998; U.S. Naval Observatory: Washington, DC, USA; pp. 69–82.

- Zhang, L.; Shen, Y.Z.; Chen, Q.J.; Wang, F.W. Influence factors and mechanisms of 2015-2016 extreme flood in Pearl River Basin based on the WSDI from GRACE. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2023, 47, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller Schmied, H.; Eisner, S.; Franz, D.; Wattenbach, M.; Portmann, F.T.; Flörke, M.; Döll, P. Sensitivity of simulated global-scale freshwater fluxes and storages to input data, hydrological model structure, human water use and calibration. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 18, 3511–3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didova, O.; Gunter, B.; Riva, R.; Klees, R.; Roese-Koerner, L. An approach for estimating time-variable rates from geodetic time series. J. Geod. 2016, 90, 1207–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthcke, S.B.; Rowlands, D.D.; Lemoine, F.G.; Klosko, S.M.; Chinn, D.; McCarthy, J.J. Monthly spherical harmonic gravity field solutions determined from GRACE inter-satellite range-rate data alone. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.D.; Ramirez, S.G.; Martin, E.-M.H.; Jones, N.L.; Williams, G.P.; Adams, K.H.; Ames, D.P.; Pulla, S.T. Groundwater Storage Loss in the Central Valley Analysis Using a Novel Method Based on In Situ Data Compared to GRACE-Derived Data. Environ. Model. Softw. 2025, 186, 106368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).