Highlights

What are the main findings?

- The integration of multi-source SAR data and multiple techniques addresses the limitations of isolated data or methods in monitoring mining-induced ground deformation.

- The spatiotemporal deformation revealed by the InSAR-based integrated approach strongly correlates with mining activity and observed fissures, with 2–3 m of maximum displacement validating the method’s robustness against field data.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- The findings further deepen the understanding of rock strata movement and surface displacement parameters in Shendong coalfield.

- The dynamic monitoring strategy proposed in this study enhances the observational effectiveness of InSAR technology for surface deformation due to coal mining.

Abstract

In the semi-desert aeolian sand areas of Northern China, surface deformation monitoring with SAR is challenged by loss of coherence due to mobile dunes, seasonal vegetation changes, and large-gradient, nonlinear subsidence from underground mining. This study utilizes PALSAR-2 (L-band, 3 m resolution) and Sentinel-1 (C-band, 30 m resolution) data, applying InSAR and Offset tracking methods combined with differential, Stacking, and SBAS techniques to analyze deformation monitoring effectiveness and propose an efficient dynamic monitoring strategy for the Shendong Coalfield. The main conclusions can be summarized as follows: (1) PALSAR-2 data, which has advantages in wavelength and resolution (L-band, multi-look spatial resolution of 3 m), exhibits better interference effects and deformation details compared to Sentinel-1 data (C-band, multi-look spatial resolution of 30 m). The highly sensitive differential-InSAR (D-InSAR) can promptly detect new deformations, while Stacking-InSAR can accurately delineate the range of rock strata movement. SBAS-InSAR can reflect the dynamic growth process of the deformation range as a whole, and SBAS-Offset is suitable for observing the absolute values and morphology of the surface moving basin. The combined application of Stacking-InSAR and Stacking-Offset methods can accurately acquire the three-dimensional deformation field of mining-induced strata movement. (2) The spatiotemporal process of surface deformation caused by coal mining-induced strata movement revealed by InSAR exhibits good correspondence with both the underground mining progress and the development of ground fissures identified in UAV images. (3) The maximum displacement along the line of sight (LOS) measured in the mining area is approximately 2 to 3 m, which is close to the 2.14 m observed on site and aligns with previous studies. The calculated advance influence angle of the No. 22308 working face in the study area is about 38.3°. The influence angle on the solid coal side is 49°, while that on the goaf side approaches 90°. These findings further deepen the understanding of rock movement and surface displacement parameters in this region. The dynamic monitoring strategy proposed in this study is cost-effective and operational, enhancing the observational effectiveness of InSAR technology for surface deformation due to coal mining in this area, and it enriches the understanding of surface strata movement patterns and parameters in this region.

1. Introduction

The disasters caused by underground coal mining, such as ground fissures, collapse, and subsidence, not only damage the surface ecology but also threaten buildings, infrastructure, and roads. Furthermore, they may redirect airflow to the working face, leading to spontaneous combustion of underground coal, which poses a serious threat to the safety of mining personnel and the layout of mining operations [1,2,3]. Interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) can rapidly obtain large-scale ground deformation and is currently one of the most effective methods for studying surface strata movement in coal mining areas. It has numerous advantages, including comprehensive coverage, non-contact measurement, no need for on-site instrument installation, the ability to archive data for historical deformation analysis, and the capacity to dynamically track changes based on the regular imaging of satellites. Therefore, the dynamic monitoring of surface deformation induced by coal mining through Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) is essential for the rapid and timely acquisition of the spatial distribution and magnitude of ground subsidence in the area. This monitoring is crucial for accurately assessing the impacts of coal mining activities, adjusting mining plans, predicting geological safety in and around the mines, and addressing issues related to land reclamation and ecological reconstruction in the mining region.

The Shendong coalfield in northern China is one of the largest coalfields in the world. This shallow and thick coalfield is located in a typical region that transitions between the aeolian sand and the loess hilly and gully area, characterized by a fragile geological environment. Coal mining has a significant impact on the environment, which has led researchers to conduct extensive InSAR monitoring and assessment of mining-induced subsidence in the Shendong mining area. Previous studies successfully applied differential-InSAR (D-InSAR) technology to monitor mining-induced subsidence in the Shendong district, Shaanxi province [4,5]. To address the limitations of traditional D-InSAR technology, researchers have attempted to apply improved InSAR techniques for monitoring. Several multi-temporal InSAR (MT-InSAR) techniques have been successively employed, such as small baselines subset InSAR (SBAS-InSAR) [6], persistent scatterer InSAR (PS-InSAR) [7], and distributed scatterer InSAR (DS-InSAR) [8]. These techniques have been demonstrated to effectively reduce the impacts of spatiotemporal incoherence as well as atmospheric phase delay [9], thus making InSAR more suitable for monitoring. To better monitor fast and large gradient subsidence, scholars have attempted to combine InSAR with coal mining subsidence prediction models [10,11], sub-pixel offset tracking (Offset) technology [12,13,14], and light detection and ranging (LiDAR) technology [15], achieving favorable results. Additionally, some researchers have proposed a time-series three-dimensional (3D) displacement inversion model based on a single geometric InSAR dataset to obtain multi-temporal 3D surface displacement [16].

However, these studies primarily focus on monitoring of deformation within large surface areas or individual working faces, and they do not integrate closely with ground fissure observations and underground mining data, which is not conducive to a comprehensive analysis of the developmental feature and formation mechanism of mining subsidence. Furthermore, the Shendong mining area is located in the semi-desert aeolian sand area, characterized by significant deformation and rapid subsidence, which presents the following adverse effects on InSAR observations: (1) Surface environment: The surface of the semi-desert region is primarily composed of sandy and gravelly terrain, which exhibits certain mobility due to strong wind effects. Some areas have been artificially modified with planted low shrubs, xerophytic grasses, and wormwoods. The vegetation is lush in the summer and autumn but sparse in the winter and spring, with limited and unevenly distributed precipitation. Its unique climatic characteristics and geological morphology complicate surface scattering. Frequent ground activities and changes in vegetation can easily lead to temporal decorrelation, while long baselines between SAR images can cause spatial decorrelation. These factors may affect the coherence of SAR images, thereby impacting the quality of InSAR interferograms. Due to the stronger penetration of SAR data at longer wavelengths, PALSAR-2 data with L-band is utilized to better penetrate vegetation, thus enhancing the coherence of InSAR. (2) Coal mining induced strata movement: The surface deformation caused by large-scale and high-intensity underground mining has characteristics such as large deformation gradient, spatial discontinuity, and high temporal nonlinearity, often resulting in loss of coherence between two SAR images, leading to the loss of information in areas with high gradient deformation [17,18]. Moreover, the interference fringes in coherent regions are often oversaturated and aliased, making it difficult to be restored with phase unwrapping algorithms, which in turn leads to phase unwrapping errors or incorrect deformation results [19]. However, the Offset method is suitable for measuring meter-level large deformations and can serve as a beneficial complement to the InSAR method. (3) Methods and technologies: The subsidence models of multi-baseline InSAR technology, such as PS-InSAR and SBAS-InSAR, are typically designed for monitoring small deformations, making it difficult to capture large gradient deformations [20]. Previous studies mostly adopted a single method and a single SAR data source. The differences in performance and applicability among various SAR data and InSAR methods for the identification of integrated mining subsidence in the Shendong coalfield require further comparison. How to enhance the monitoring effectiveness of surface deformation in shallow buried thick coal seams in the semi-desert aeolian sand area by integrating multiple methods remains to be further explored. Therefore, it is planned to use a combination of various processing techniques along with InSAR and the Offset method to process SAR data from two sources and conduct comparative analysis.

To address the above issues, this paper focuses on the SGT mine in Shenmu City, Shaanxi Province, China, as a representative research area. Two mainstream SAR data sources, Sentinel-1 and PALSAR-2, are employed, utilizing InSAR and Offset methods. Through three data optimization strategies—Different, Stacking, and SBAS—and their various combinations, monitoring results are obtained. These results are subsequently compared and validated against underground mining progress and ground fissures identified from unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) images, as well as observation data from global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) and leveling. This research establishes an SAR dynamic monitoring strategy for surface deformation in coal mining areas applicable to the region and reveals the development laws and key parameters of subsidence.

This study aims to enhance the effectiveness and application value of InSAR technology in detecting mining-induced ground subsidence in this region, which holds significant implications for the further application of InSAR methods in detecting subsidence in the Shendong mining area. Furthermore, rapidly and timely obtaining the spatial distribution range and deformation magnitude of surface subsidence in this area can provide valuable references for geological disaster prevention, ecological protection, and sustainable development in similar mining regions.

2. Data and Technical Methods

2.1. Data

Previous studies have shown that short-wavelength radar waves are more sensitive to ground deformation. Long wavelengths exhibit better penetration capabilities and are more suitable for low-coherence environments and areas with large deformation gradients; however, they are less sensitive to minor mining subsidence compared to short-wavelength waves. For the monitoring of location and deformation of the SGT coal mine in the Shendong coalfield, this study used two types of SAR data with different time intervals, wavelengths, and resolutions. Sentinel-1 is an Earth observation satellite developed by the European Space Agency, operating in the C-band with a wavelength of approximately 5.6 cm. It has a short revisit time of 12 days, and the ascending data spans from 9 January 2022 to 18 September 2022, comprising 14 periods. Its high temporal resolution can enhance observation effectiveness to a certain extent. The Advanced Land Observing Satellite (ALOS) is Japan’s Earth Observation satellite. The Phased-Array L-Band Synthetic Aperture Radar-2 (PALSAR-2) on the ALOS operates in the L-band with a wavelength of about 23.8 cm; the ascending data from 24 January 2022 to 5 September 2022, encompasses 6 periods (Table 1). The terrain data used for InSAR processing is a 30-m resolution ALOS World 3D Digital Surface Model (DSM), published by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA).

Table 1.

SAR data parameters.

Aerial photography was conducted using a DJI M300 RTK drone (Shenzhen DJI Innovations Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, Guangdong province, China) equipped with a Zenmuse P1 camera to generate a 0.05 m resolution Digital Orthophoto Map (DOM) and Digital Surface Model (DSM) of the study area. The deformation for the No. 31305 working face is determined by the complete subsidence measured jointly by GNSS and leveling instruments after the stabilization of mining-induced deformations. The observation time and resolution are presented in Table 2. Through comparative analysis with data such as field surveys, ground fissures extracted from UAV-derived DOM and DSM images, underground mining progress, and the deformation data of No. 31305 working face, the ground deformation results obtained from InSAR observations are validated.

Table 2.

Verification Data Information.

2.2. Method

2.2.1. Main Technical Methods

This study employs various strategies, including the differential processing of InSAR and Offset, as well as Stacking and SBAS, for calculations and mutual verification. The specific process is outlined as follows.

D-InSAR processing: The D-InSAR method is the most fundamental, simplest, and most effective InSAR observation method for surface deformation, featuring advantages such as low cost, high accuracy, and extensive spatial coverage [21]. By differencing data from at least two periods, an interferogram is formed. In this interferogram, the phase contains not only the topographic phase but also contributions from ground effects, deformation signals, atmospheric disturbances, and noise components. Since the differenced interferometric phase remains wrapped, it is necessary to resolve the remaining phase components. Specifically, appropriate phase unwrapping techniques are employed to retrieve the integer ambiguity, while precise orbital information is utilized to eliminate ground effects. An external Digital Elevation Model (DEM) is introduced to remove the topographic phase obtained from the InSAR interferogram, filtering techniques are applied for noise reduction, and atmospheric phases are eliminated using external data or atmospheric models. Finally, the resultant differenced interferometric phase can be converted into surface displacement by multiplying by a constant factor. The conventional applications of D-InSAR are primarily limited by temporal and spatial decorrelation and atmospheric phase screening [22,23].

Stacking processing: When using D-InSAR technology to measure ground deformation, the atmospheric phase caused by water vapor refraction acts as interference noise, which can severely affect the accuracy of the results. Additionally, due to the limited number of SAR images involved in the calculation, it is quite difficult to directly eliminate the interference from this atmospheric phase. Stacking-InSAR technology is a method that estimates average line-of-sight (LOS) deformation by performing a weighted average on multiple unwrapped interferograms based on the time span, thereby minimizing atmospheric errors and improving deformation accuracy [24]. Although the Stacking-InSAR method can achieve more accurate results than D-InSAR in certain cases, it still requires a more refined ground model to reduce topographic errors and obtain continuous subsidence results [23,25].

SBAS processing: To improve the accuracy of InSAR monitoring, Berardino et al. proposed the SBAS-InSAR technique in 2002. This method enhances the temporal sampling rate by combining a series of differential interferograms with short temporal and spatial baselines and then connects isolated SAR datasets that result from large spatial baselines using the SVD method. It also increases the spatial density of deformation measurements. This technique is robust to potential errors in the DEM used during the generation of differential interferograms and effectively removes atmospheric phase screens from the results [26]. However, SBAS-InSAR is only suitable for pixels with sufficiently high coherence [27].

Offset method: Offset is based on the intensity of two or more SAR images and employs normalized cross-correlation (NCC) maximization to extract the pixel offset in the range and azimuth direction, thereby calculating deformation. The process mainly comprises two core steps: intensity registration and systematic error elimination [12,28]. This method offers the following advantages: (1) It performs offset calculations using the intensity values of SAR images without utilizing phase information, which reduces the impact of temporal decorrelation and allows for the calculation of deformation over long time intervals, thus avoiding the issues associated with fragile spatiotemporal unwrapping. (2) It has a large measurement range and is generally used to calculate deformations of the order of meters or more, addressing problems of decorrelation caused by significant gradients in surface deformation.

2.2.2. Technical Strategies for SAR Observations

Currently, there are primarily two core methods for measuring surface deformation using SAR remote sensing images: InSAR [21,29] and Offset [28,30]. The deformation measurement accuracy of InSAR phase images can reach the centimeter to sub-centimeter level [18]. However, the prerequisite for achieving this measurement accuracy is that the InSAR images must have coherence, the deformation gradient should not be too large, and the time interval between SAR image acquisitions should not be too long [17,24]. The Offset technique can measure large gradient deformations but has relatively low accuracy, with theoretical accuracy only reaching 1/10 to 1/30 of the pixel resolution of the SAR images. For example, the measurement accuracy of the Offset technique based on PALSAR-2 SAR data is approximately several tens of centimeters [9,12,31,32].

To fully utilize multi-temporal SAR data, effectively eliminate errors, and enhance the accuracy of deformation measurements, various data optimization combination algorithm strategies have been developed by previous researchers. (1) The simplest and most direct D-InSAR method using two scenes of SAR data is straightforward, quick, and retains details well; however, it is susceptible to error interference, lacks redundant measurements, and cannot eliminate various errors. (2) Based on multi-temporal D-InSAR data, a time-weighted overall deformation strategy named Stacking has been developed, which eliminates random errors such as atmospheric and ionospheric effects through multi-temporal Stacking; however, the result yields only an overall average rate. (3) By employing a strategy that combines the “minimum” temporal and spatial baselines, the SBAS computes the deformation time series through least squares (LS) and singular value decomposition (SVD) [26]. While this method can determine the temporal process of deformation, it is affected by the smoothing strategy, which may obscure abrupt changes and significant deformations.

Based on the two measurement methods and three optimization strategies mentioned above, previous researchers have proposed methods such as D-InSAR [21], Stacking-InSAR [24], PS-InSAR [33,34], SBAS-InSAR [26], Offset [12,28], SBAS-Offset [31] and Stacking-Offset [35].

For the characteristics of the study area and objectives, it is necessary to comprehensively apply various methods and optimization strategies (Table 3). The rapid and sensitive D-InSAR will be utilized to timely detect new surface moving basins; the time-series SBAS-InSAR will measure the development and changes in deformation to analyze its dynamic failure process; the Stacking-InSAR, which emphasizes overall intensity, will identify the locations, extent, and deformation rates of changes; and the Offset method will fill the measurement gaps for deformations ranging from one meter to ten meters. Additionally, two mainstream datasets, Sentinel-1 and PALSAR-2, will be used to explore the impacts of data wavelengths in deformation monitoring. Based on these datasets, using suitable SAR observation techniques can reveal the pattern of strata movement associated with underground coal mining.

Table 3.

Data, methods, strategies, and the issues to be addressed.

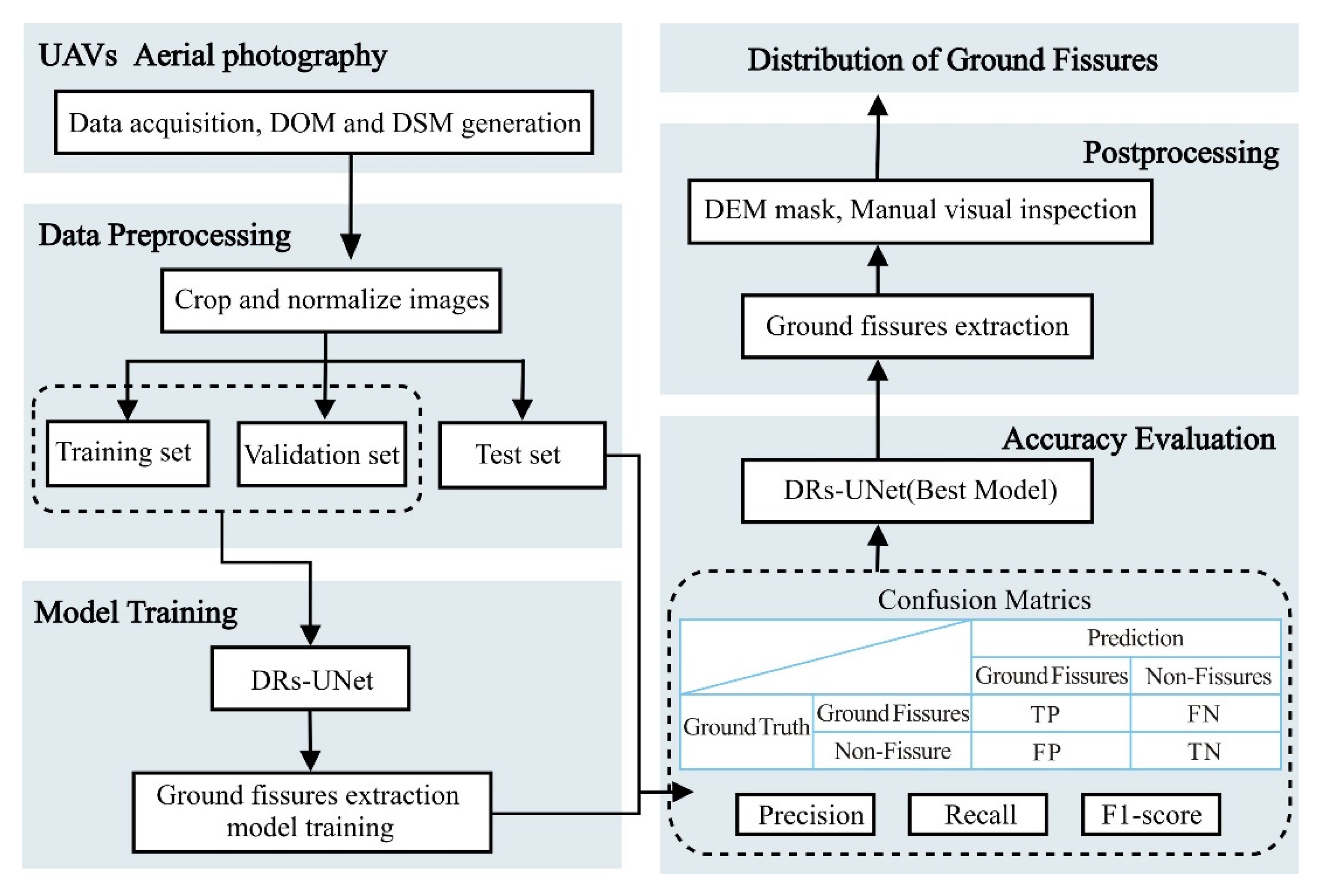

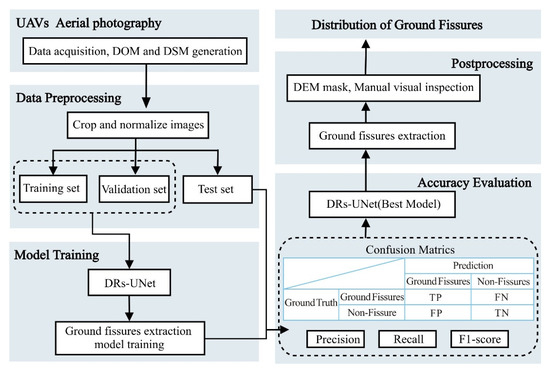

2.2.3. Ground Fissure Identifying Method Based on DRs-UNet

The DRs-UNet (Deep Residual Shrinkage U-Net) method enables end-to-end extraction of geological faults. It is a convolutional encoder–decoder network that combines the U-Net and ResNet models’ structures with the soft thresholding method [36,37]. The process for extracting ground fissures from UAV images using DRs-UNet is shown in Figure 1 and is completed in six steps. (1) Stitching together the images captured by UAVs to create a digital orthophoto map (DOM) and a digital surface model (DSM) of the study area. (2) Visually interpreting and labeling the ground fissures in the DOM images, clipping the labeled data into image patches, normalizing them, and splitting them into three datasets: training, validation, and testing. (3) Constructing and training the model using the DRs-UNet method. (4) A confusion matrix for the binary classification task of fissure extraction. True positives (TP) represent “predicted as fissure, and the prediction was correct.” True negatives (TN) mean “predicted as no fissure, and the prediction was correct.” False negatives (FN) refer to “predicted as fissure, but the prediction was incorrect.” False positives (FP) indicate “predicted as no fissure, but the prediction was incorrect.” The trained model is quantitatively evaluated using Precision, Recall, and F1-score. (5) Utilizing the trained DRs-UNet model to identify and extract ground fissures in the mining area, followed by manual visual inspection, supplementing any unrecognized fissures and removing misclassified information. (6) Obtain the real distribution data of ground fissures.

Figure 1.

A flowchart of extraction ground fissures from UAV images based on DRs-UNet.

A confusion matrix is established by comparing the extracted results of DRs-UNet with the real distribution. The accuracy evaluation employs common quantitative assessment metrics such as Precision, Recall, and F1-score, with values of 86.07%, 86.12%, and 86.08%, respectively [36].

3. Study Area

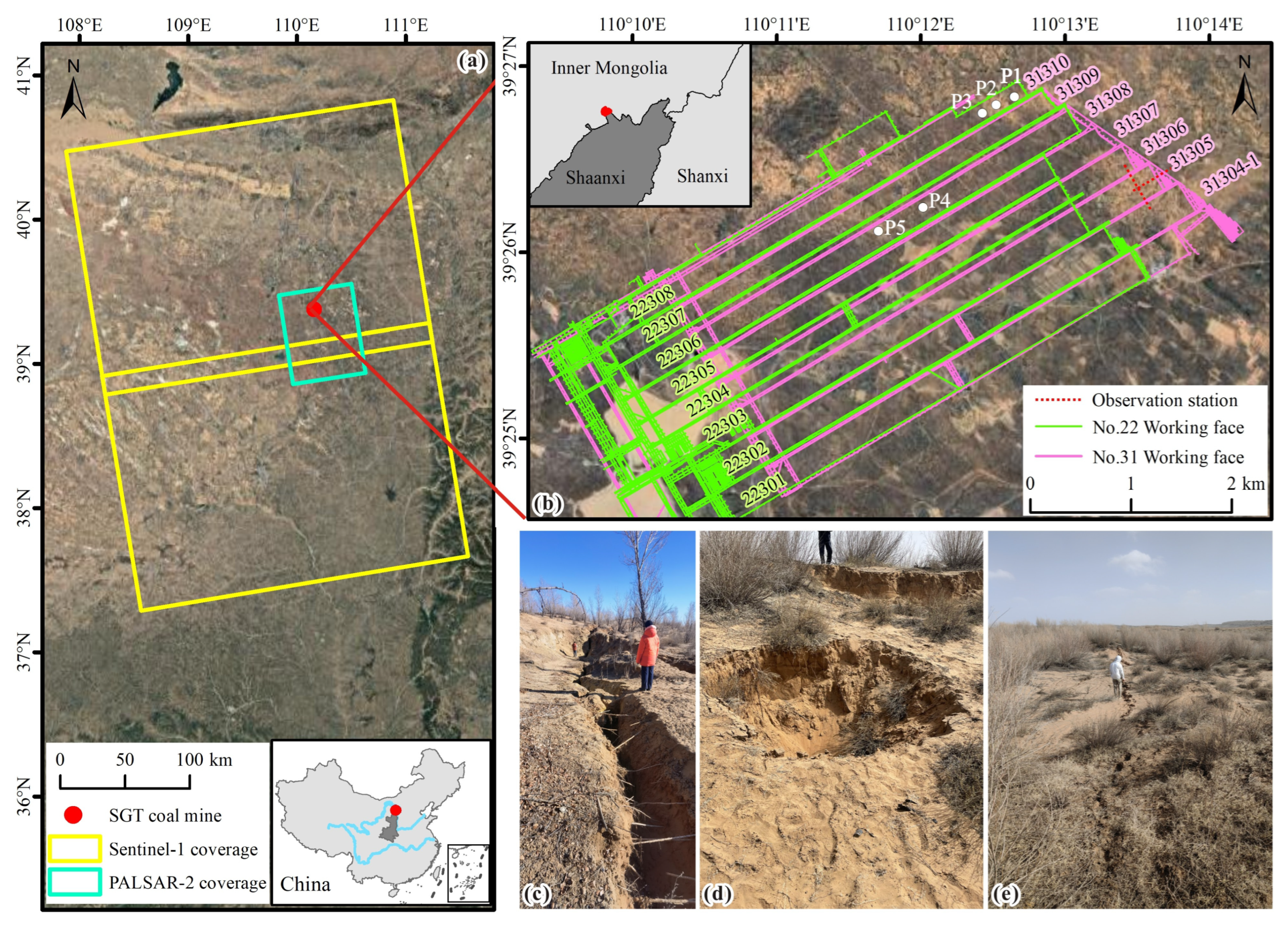

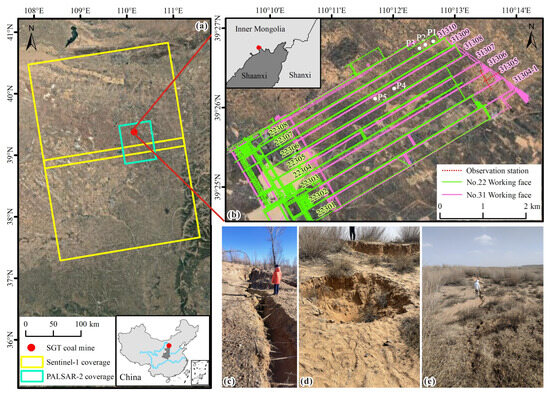

The SGT Coal Mine in Daliuta Town, northern Shendong Mining Area, is located at the junction of the northern part of the Loess Plateau in northern Shaanxi and the southeastern edge of the Mu Us Desert (Figure 2). The geomorphic units can be divided into two categories. One is the aeolian sand area in the northern part of the coal mine, where the dunes are continuous and undulating with relatively flat terrain. The other is the loess hilly–gully region in the southern part of the coal mine, characterized by alternating ridges and mounds and narrow valleys. The ridges are featured with wide, gentle flat tops, while the bedrock is intermittently exposed on both sides of the valleys. The topography features higher elevation in the east and lower elevation in the west, with an average altitude of 1250 m and a relative elevation difference not exceeding 250 m. The ground vegetation consists mainly of artificially planted sand-fixing poplars and sand willows, as well as wild drought-resistant grasses and wormwoods. This area has a semi-arid continental monsoon climate in the northern temperate zone, with severe soil and water erosion. The coal-bearing strata of study area, forming part of the Lower-Middle Jurassic Yan’an Formation, developed in the Ordos Basin. It consists mainly of sandstone and mudstone [36]. Most of the bedrock in the coal mine is covered by Quaternary deposits, and the average thickness of the loose layer is about 8 m. The strata generally trend north-northwest and dip to the west-southwest. The geological structure of the mine is simple, with no folds, gentle strata, and an overall dip angle of less than 3°, which is close to horizontal. It exhibits a monocline structure that tilts westward, without any igneous rock bodies.

Figure 2.

Research background map. (a) The approximate location of SGT coal mine (red point). The yellow and green polygons indicate the coverages of Sentinel-1 and PALSAR-2, respectively. (b) The approximate location of study area, which lies at the junction of Inner Mongolia Province and Shaanxi Province in China. The mining area, and the distribution of working faces. The background image illustrates the semi-desert aeolian sand area environment. There are 30 observation stations in the direction of the strike and 41 in the direction of the dip at the No. 31305 working face, with a spacing of 15 m. (c) Scene photos of deep and large fissures in the open-cutting. (d) Collapse pit and step large fissures in the center deformation area above the working face. (e) Vegetation and geomorphology and ground fissures above the laneway at the edge of the face parallel to the direction of mining.

The SGT coal mine utilizes the fully mechanized longwall mining method and the complete collapse method for the roof management, making it susceptible to large-scale surface subsidence in the mining area. Currently, No. 22 and No. 31 coal seams are being mined simultaneously: (1) No. 22 coal seam is located above, with an average burial depth of approximately 97 m, a thickness of 1 to 6 m, and an average thickness of 3.30 m. The thickness of the coal seam varies significantly, and it is classified as a stable, medium-thick coal seam. (2) No. 31 coal seam is located below, with an average burial depth of about 134 m, a thickness of 2 to 4 m, and an average thickness of 3.82 m. It is a stable, thick coal seam featuring approximately homogenous thickness and simple structure. The surrounding rock of the tunnels is sedimentary layered clastic rock, predominantly composed of mudstone and sandstone, with medium-thick and thin layered structures and significant variations in mechanical strength.

Generally, the No. 31 coal seam below is mined approximately three years after the No. 22 coal seam working face has been mined. In this article, the naming convention for the working faces is as follows: the working face of the No. 22 coal seam begins with “No. 22”, while the working face of the No. 31 coal seam begins with “No. 31”.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. InSAR Results

Due to the characteristics of surface coverage and backscattering in semi-desert aeolian sand areas, technical methods described in Section 2.2 are employed for comparative observations to enhance accuracy and reliability.

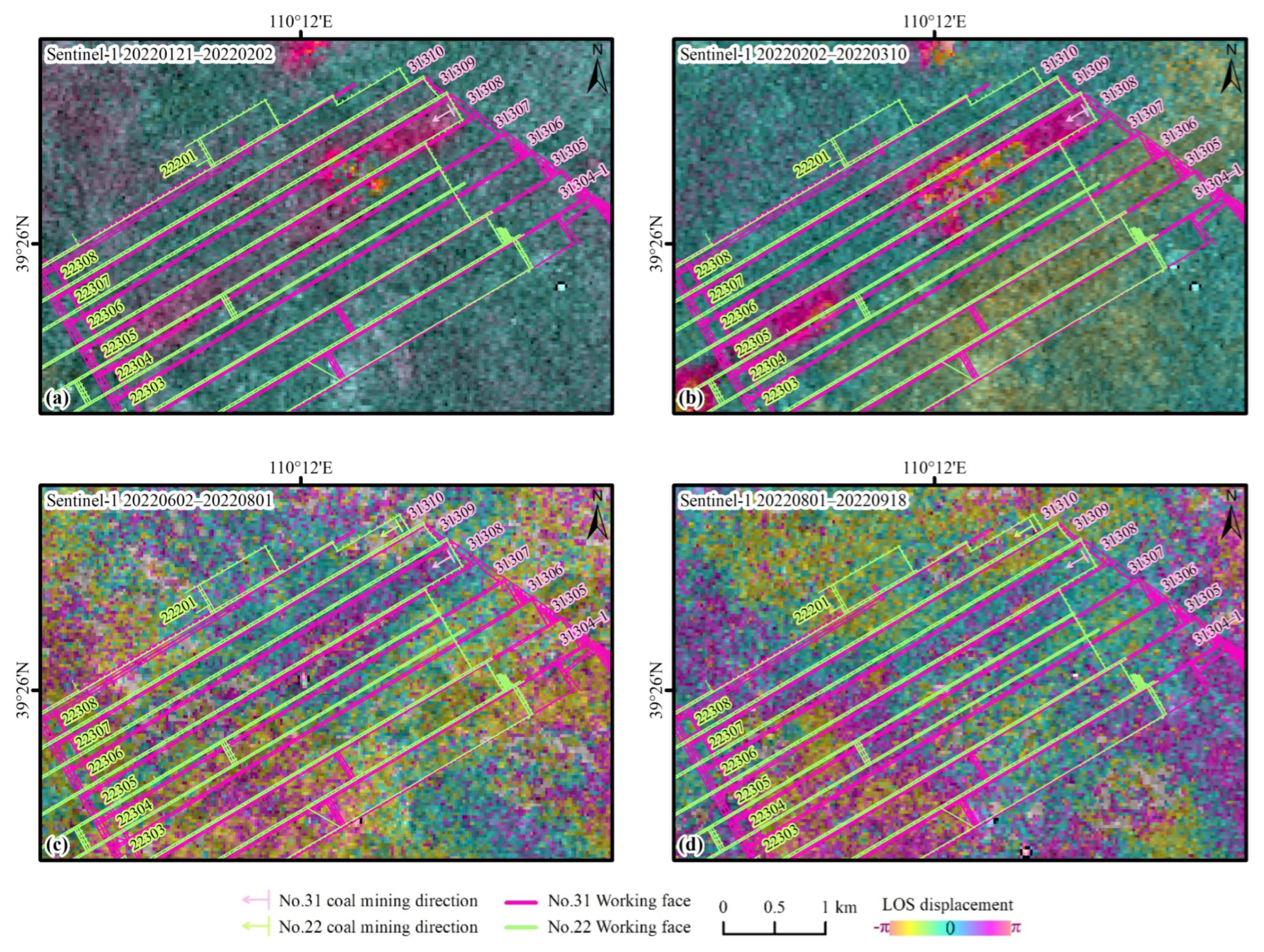

4.1.1. Seasonal Results Resolved by the D-InSAR Method Using Different SAR Data

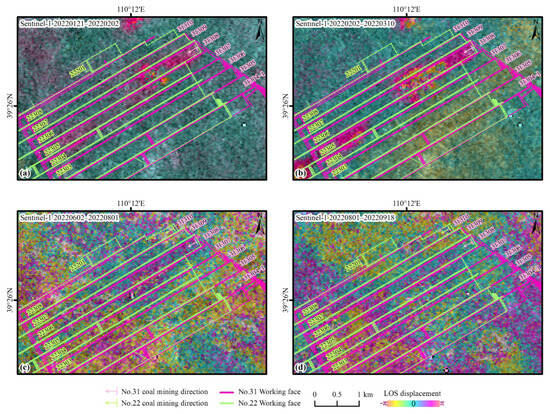

- Seasonal Results Resolved using Sentinel-1 Data

The 12-day revisit period of Sentinel-1 enables timely observation of changes in mining progress and continuous monitoring of the ground surface. Representative interferograms from the four seasons of winter, spring, summer, and autumn are selected for analysis (Figure 3). In the interferograms, blue indicates stable areas, while red and yellow denote deformation regions. Overall, the Sentinel-1 interferograms perform better in the winter and spring, with a clear correspondence between the deformation zones and the active working faces during these periods. The deformation in past working faces is minimal, and there are essentially no deformation patches in non-mining areas. The observation result is consistent with surface deformation laws and exhibits virtually no artifacts. However, interference effects are poorer in summer and autumn, with obvious atmospheric error artifacts that are so strong that they blur the coal mining deformation areas. Due to the short wavelength of Sentinel-1 C-band, which is sensitive to deformation, residual deformation after large surface deformation caused by strata movement can be recorded in the image. Spatial dynamic observations in winter and spring show that the range of strata movement deformation at the working face gradually expands, forming a strip-like distribution with obvious directionality. This indicates the progression of the deformation range, which is consistent with the mining schedule.

Figure 3.

Seasonal results resolved by D-InSAR method using Sentinel-1 data. (a) Winter: 21 January 2022–2 February 2022 (12 days); (b) Spring: 2 February 2022–10 March 2022 (36 days); (c) Summer: 2 June 2022–1 August 2022 (60 days); (d) Autumn: 1 August 2022–18 September 2022 (48 days).

- 2.

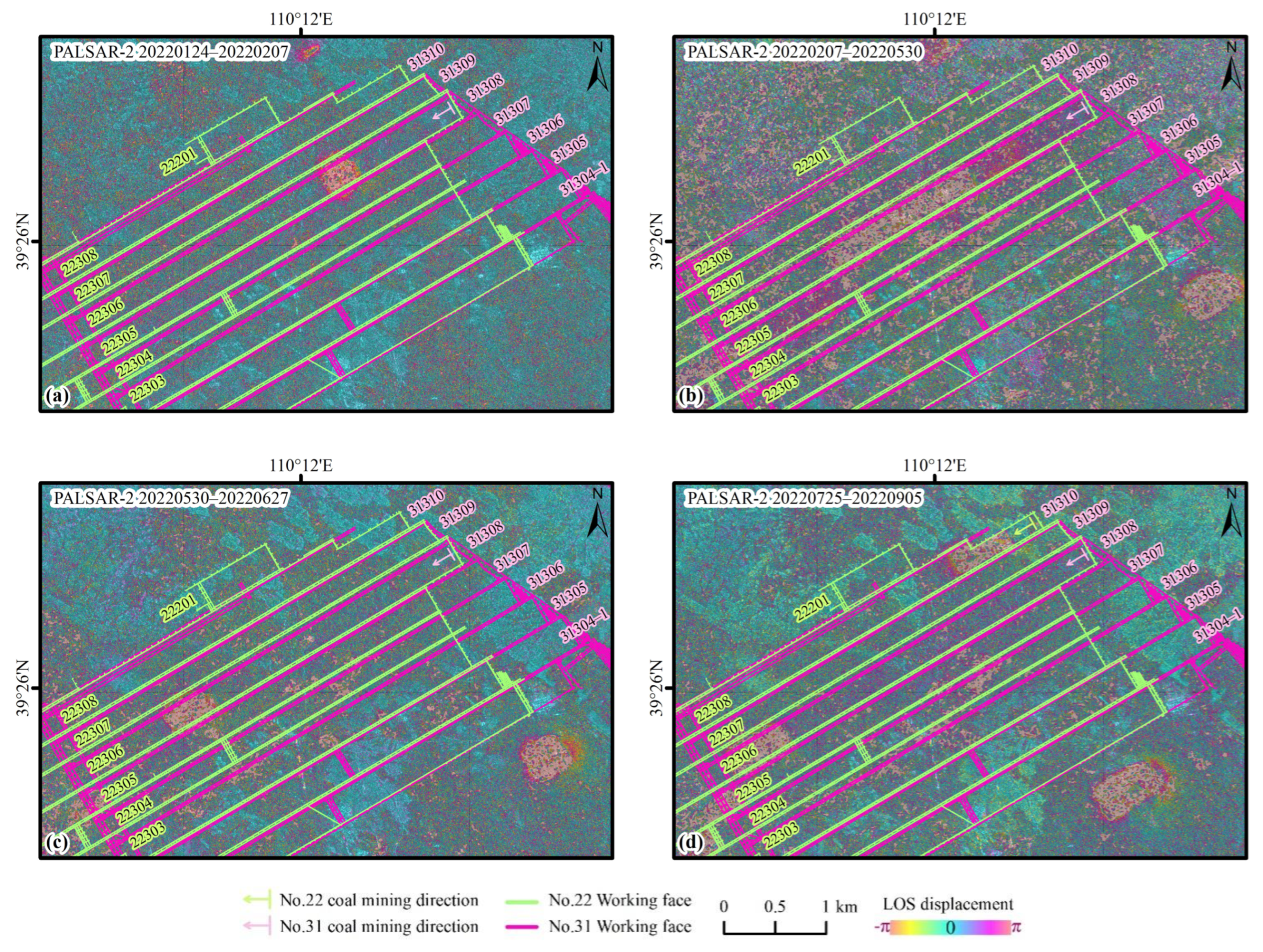

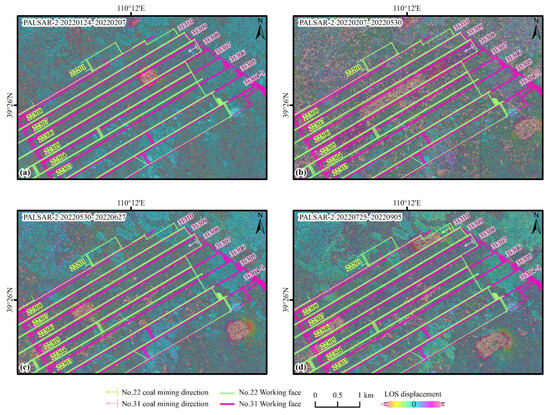

- Seasonal Results Resolved using PALSAR-2 Data

PALSAR-2 SAR data not only has high resolution but also features a long wavelength and good coherence, which can enhance the quality of ground deformation observations and yield more stable D-InSAR imaging results. The deformation zones primarily manifest as several near-circular or elliptical surface-moving basins, without the strip-like surface deformation features observed by Sentinel-1 D-InSAR. This is mainly due to the L-band of PALASR-2 being insensitive to minor deformations, which prevents the manifestation of slight strip-like residual strata movement.

The PALSAR-2 data exhibit excellent interferometric performance during the winter, summer and autumn. However, due to the lack of data between 7 February and 30 May 2022, the time baseline extends to 112 days, resulting in slightly poorer interferometric performance for this season, although it is still better than the effect of Sentinel-1’s short baseline in spring (Figure 3b). The large gradient deformation in the central region of the subsidence area caused by intensive mining leads to InSAR decorrelation, making it impossible to measure the maximum subsidence. In contrast, the boundary of the subsidence area shows relatively small deformation, with no decorrelation due to large gradient deformation, allowing InSAR to clearly observe distinct deformation values and well-defined deformation boundaries (Figure 4). In contrast, the deformation magnitude at the boundaries of the subsidence area is relatively small, with no incoherence due to large-gradient deformation, allowing InSAR to clearly observe the deformation magnitude and well-defined deformation boundaries (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Seasonal results resolved by D-InSAR method using PALSAR-2 data. (a) Winter: 24 January 2022–7 February 2022 (14 days); (b) Spring: 7 February 2022–30 May 2022 (112 days); (c) Summer: 30 May 2022–27 June 2022 (28 days); (d) Autumn: 25 July 2022–5 September 2022 (42 days).

4.1.2. Mining-Induced Ground Deformation Through Various Technologies

Comparative analysis of the SAR data at the above two wavelengths indicates that PALSAR-2 L-band data exhibits better coherence and resolution than Sentinel-1 C-band data. Therefore, the following sections will utilize different methods and strategies to process six periods of PALSAR-2 SAR data to reveal the surface deformation process of the underground mining.

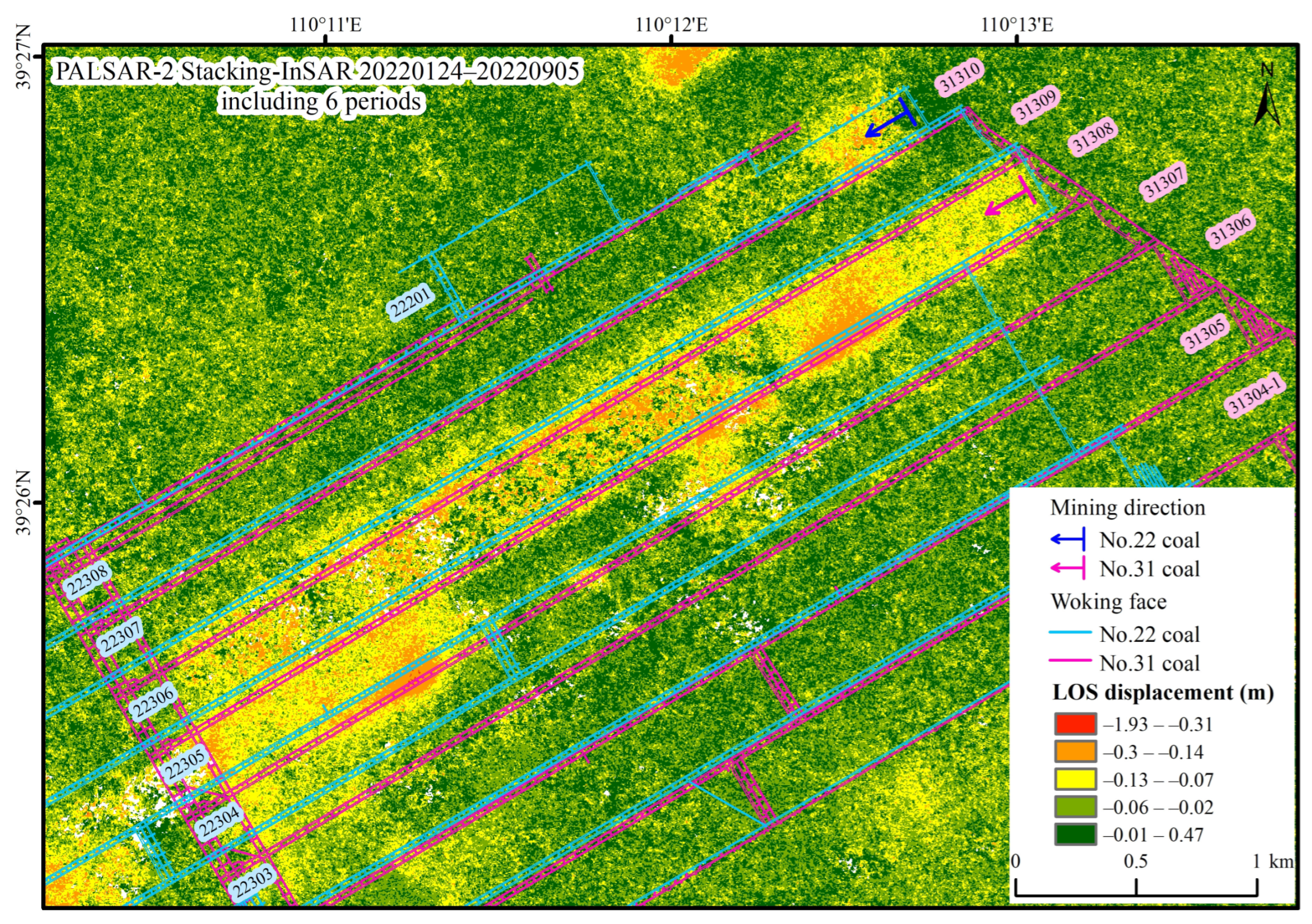

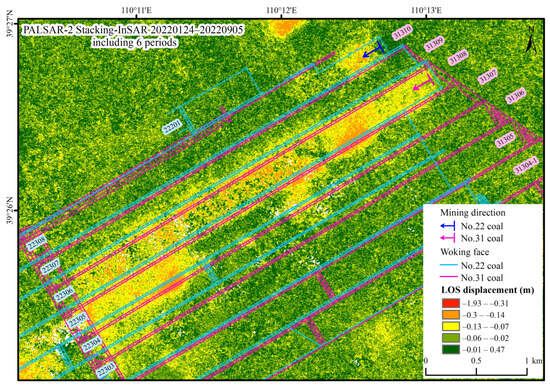

- Stacking-InSAR

Overall, we used the Stacking-InSAR technique to identify the mining-induced ground deformation from 24 January 2022 to 5 September 2022 (224 days). The mining-induced ground deformation is mainly concentrated in the last one-third section of the No. 31307 working face, the entirety of the No. 31308 working face, and the initial section of the No. 22308 working face. These subsidence patterns captured the development of the working faces. This is attributed to the use of D-InSAR “partial union” parameter selection during the Stacking process, which avoided the appearance of null value areas and allowed for a complete display of the deformation range. However, this method comes at the cost of sacrificing some measurement accuracy. Additionally, due to the decorrelation caused by large deformation gradients in InSAR, the Stacking-InSAR deformation maps exhibit issues such as local spatial discontinuities, insignificant differences in deformation values of subsidence basins, and the maximum cumulative deformation of only 0.3 m (Figure 5). The deformation range is concentrated above the mining face and extends less on both sides of the working face. This is primarily because the No. 31 coal seam is subjected to repeated mining, with the upper coal seams No. 12 and No. 22 already having been mined out, resulting in surface deformation primarily characterized by vertical surface collapse.

Figure 5.

The LOS displacement (24 January 2022–5 September 2022, 224-day interval) resolved by the Stacking-InSAR method using the PALSAR-2 data.

- 2.

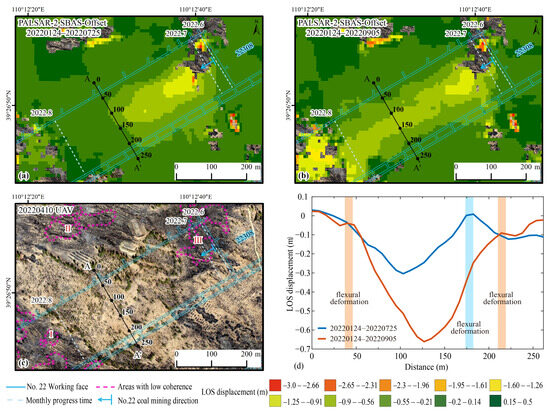

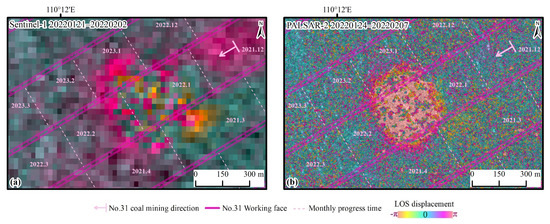

- SBAS-Offset

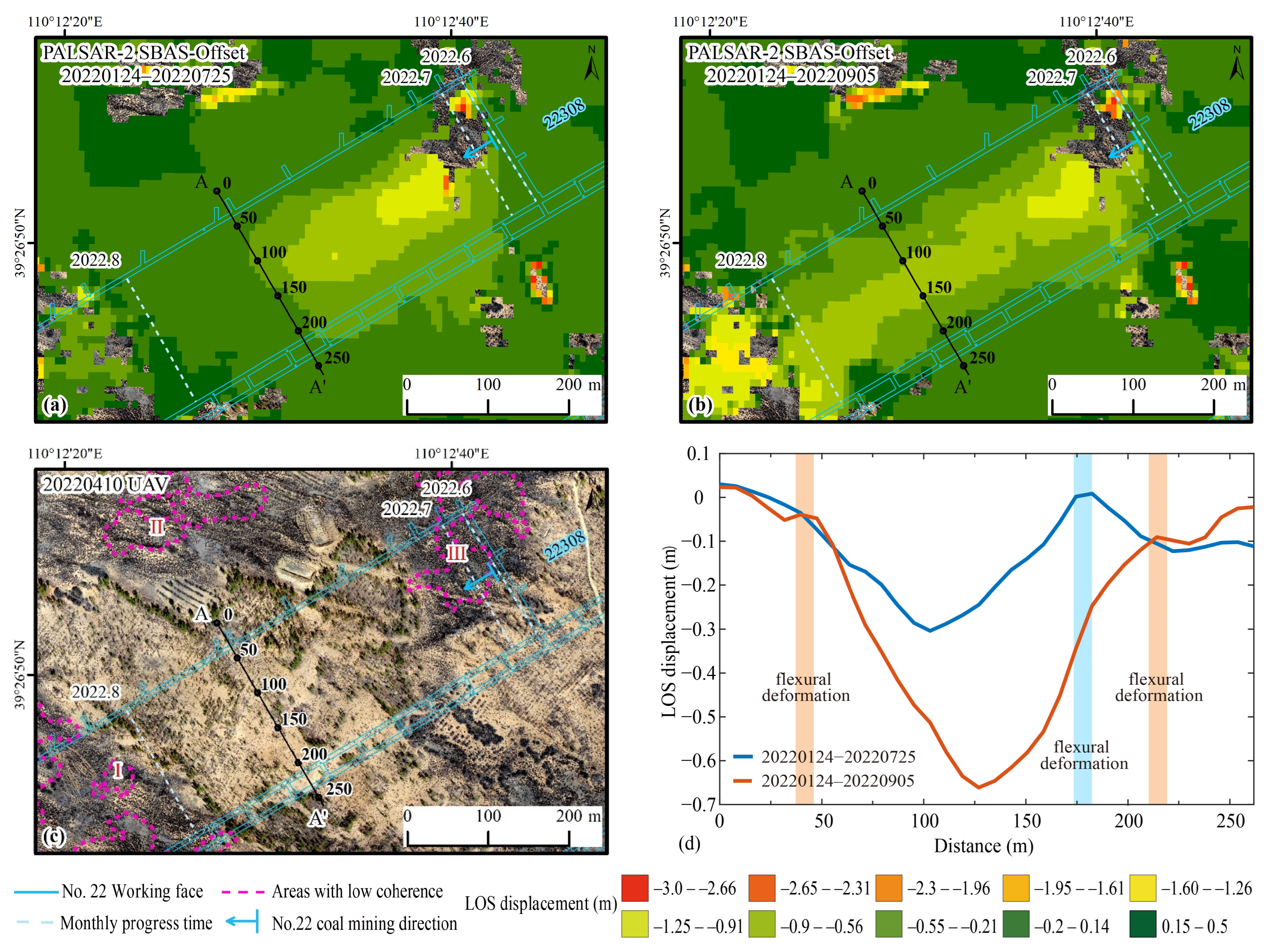

Due to significant surface deformation, the D-InSAR displacement field experiences phase decorrelation, leading to monitoring blind spots in the central area of the working face, which makes it difficult to accurately capture the large subsidence in the central collapse zone. The Offset approach can provide a more accurate estimate of large deformation subsidence, serving as a good complement to the D-InSAR. First, a SBAS baseline network is constructed based on PALSAR-2 parameters; then, the offset deformation values for each pair in the baseline network are calculated; finally, the time-series deformation map is estimated using SVD.

The results resolved by the SBAS-Offset approach clearly demonstrate the actual large deformation values, mining subsidence range, and surface moving basin growth process around the northeastern open-cutting of the No. 22308 working face during July and August 2022 (Figure 6a,b). More importantly, the measured large deformation values reveal the true subsidence pattern of the surface moving basin that cannot be observed by InSAR—a centrally symmetric structure with significant deformation in the middle and gradually decreasing on the sides. This closely aligns with the spatial and temporal distribution of the working face in July and August, and through comparison with underground data, it can also reflect the underground mining pressure, air leakage, and water seepage to some extent.

Figure 6.

Time-series monitoring of deformation resolved by the SBAS-Offset method using PALSAR-2 data at the No. 22308 working face. LOS deformation and monthly mining progress within the interval of (a) 24 January 2022–25 July 2022 (182 days) and (b) 24 January 2022–5 September 2022 (224 days). (c) UAVs aerial photography observed on 10 April 2022. (d) The cumulative time-series LOS displacement on section line A-A’. The orange and blue background rectangles indicate the flexural deformation position during the periods of 24 January–25 July 2022 and 24 January–5 September 2022, respectively.

The cross-sectional deformation diagram also shows a similar pattern (Figure 6d, line A-A’). During the period from 24 January to 25 July 2022, the maximum cumulative deformation is 0.30 m, with a small amount of subsidence and insufficient surface settlement. As mining continues to advance, the central point keeps sinking. During the period from 24 January to 5 September 2022, the maximum cumulative deformation reached 0.66 m. The deformation amplitude of the subsidence basin along the cross-section displays an overall symmetrical distribution, with mining-induced effects extending to the edge of line A-A’.

At the same time, this result shows a sensitive response to the subtle deformational features of coal mining-induced subsidence basins. For example, it reveals the flexural deformation of the subsidence basin, where “reverse arching” patterns were observed at the 180 m mark along the profile line AA’ from 24 January to 25 July 2022, and at the 45 m and 210 m marks along the profile line AA’ from 24 January to 5 September 2022 (Figure 6d).

It should be emphasized that Figure 6a,b both contain three similar “null value” areas. We found the reason through analyzing the UAV aerial photography. It is due to the low cross-correlation of image intensity caused by dense grass and shrub coverage on the ground surface (Figure 6c: Areas I, II, and III circled by the pink dashed line). This results in high registration errors in the SAR images, which prevent the calculation of deformation values. This indicates that the SBAS-Offset method is more suitable for SAR data with good correlation covering mining areas; otherwise, the benefits of establishing the SBAS network are limited.

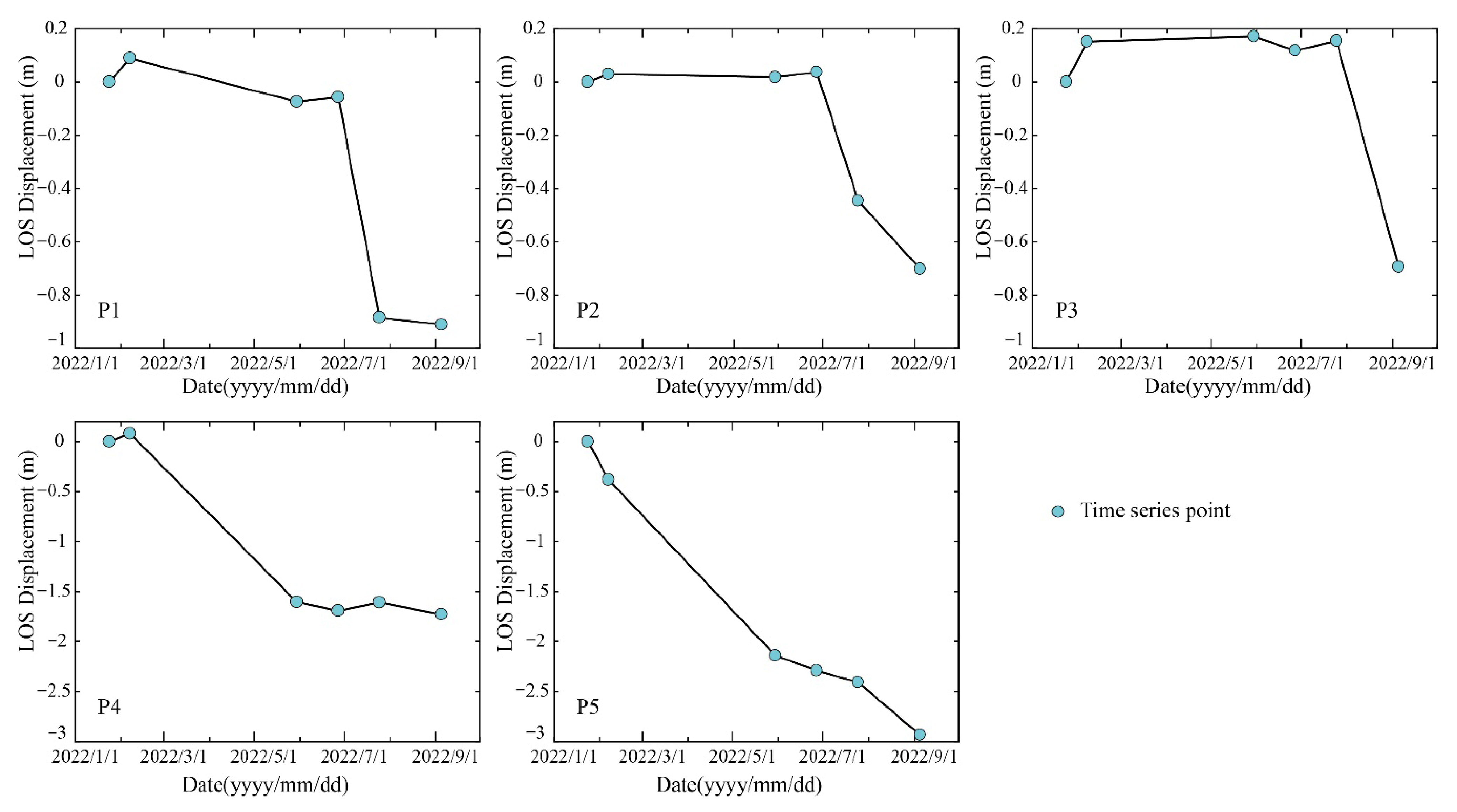

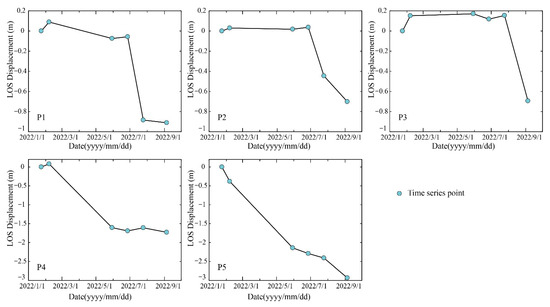

To further analyze the impact of underground mining activities on surface deformation, the time series change curves for characteristic points P1 to P5 (Figure 2) were obtained based on SBAS-Offset temporal results from January to September 2022 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Deformation time series from P1 to P5 in the study area from 24 January 2022 to 5 September 2022.

P1, P2, and P3 are sequentially arranged near the open-cutting of No. 22308 working face. The mining of P1 began in early July, where rapid deformation occurred in July, with a relatively small deformation and essentially stabilizing in August, resulting in a cumulative deformation of 0.91 m. P2 was mined in mid-July, with a deformation value of 0.45 m observed on 25 July, followed by a continuous increase, reaching 0.70 m on September 5. P3 began mining at the end of July, showing no deformation on 25 July, and a deformation of 0.69 m was observed on 5 September. P4 and P5 are located in the middle of No. 31308 working face. P4 was mined in early March, with deformation essentially stabilizing from June to September, resulting in a cumulative deformation of 1.73 m. P5 is situated in a low-lying area, about 5 m lower than the surrounding terrain, and was mined in early April. Deformation growth slowed from June to July, with deformation occurring again in August, leading to a cumulative deformation of 2.96 m, which is the maximum deformation value observed.

The time series diagram of the characteristic points shows the sequential mining of different locations along the strike of the working face and the corresponding generation of deformation over time, with gradual increases in deformation values. The subsidence amount at No. 22308 working face is generally 1 m; while at No. 31308 working face is typically 2 m, with local values reaching up to 3 m. The upper part of No. 31308 working face is a mined-out area over the 22 coal seams. Due to the influence of mining-induced activation, the surface deformation at No. 31308 working face is generally greater than that at No. 22308 working face. After underground mining, surface deformation begins approximately 10 days later, with an active period of surface movement and deformation lasting 2 to 3 months; areas that have already deformed may experience additional subsidence due to the influence of the overlying mined-out area and topography.

- 3.

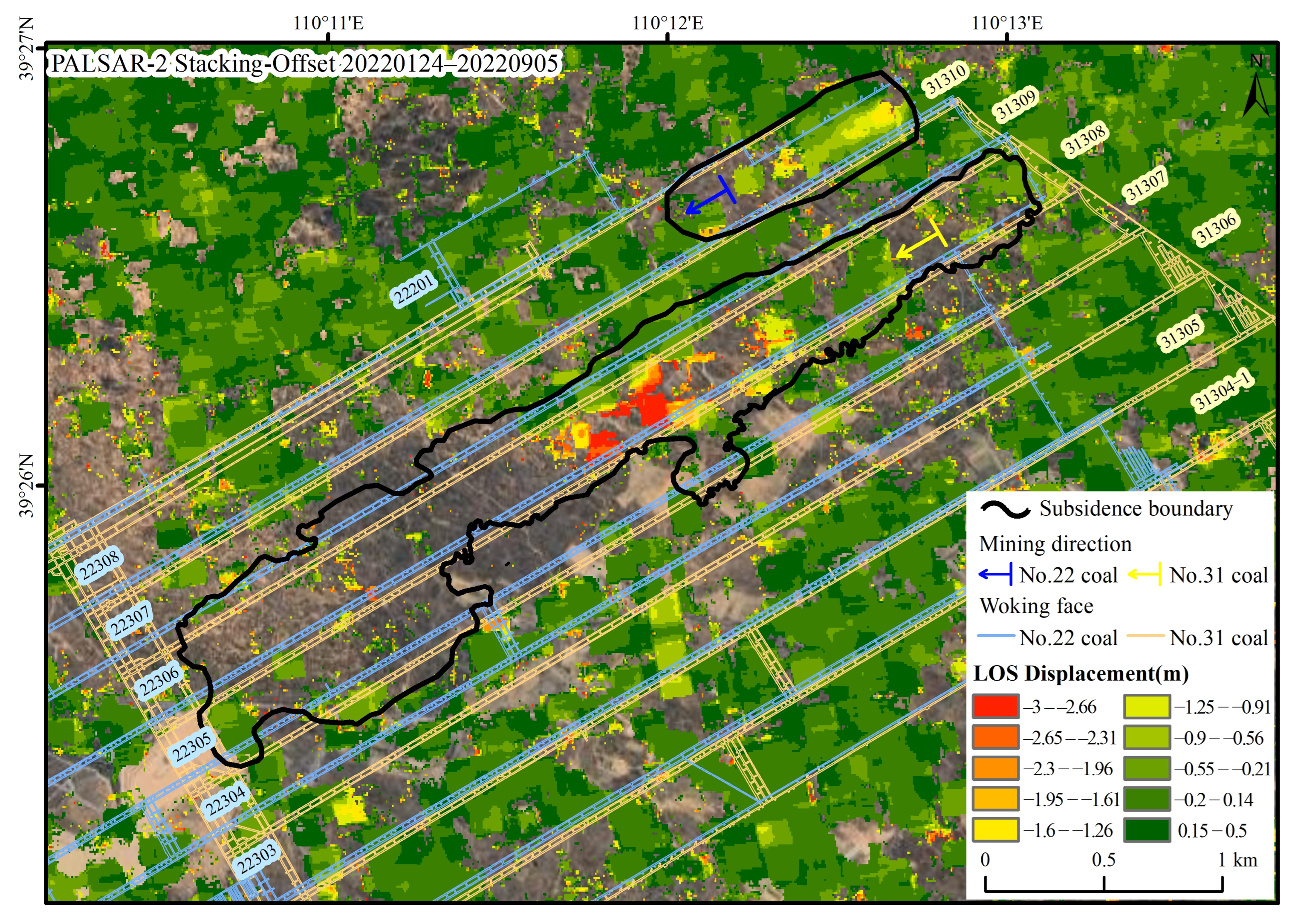

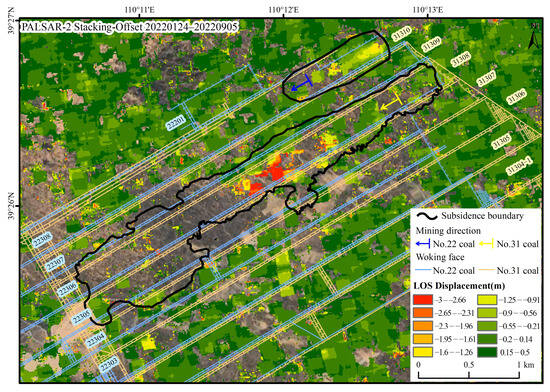

- Combined method to Identify Deformation Range and Values (Stacking-InSAR and Stacking-Offset)

Previous studies have shown that the best accuracy for Offset measurements in the distance and azimuth directions is approximately 1/30 of a SAR pixel. In this paper, L-band PALSAR-2 data with a resolution of 1.5 to 1.8 m is employed, with an optimal theoretical accuracy of around 5 to 6 cm. However, due to various errors, the actual accuracy typically reaches about 1/10 of a SAR pixel, approximately 15 to 20 cm, which is at the decimeter level and much lower than the phase measurement accuracy of InSAR (centimeter to sub-centimeter level) [12,31,32].

For the excavation of the No. 31308 working face, the Stacking-InSAR approach fully presents the deformation range of the mining area, but in the area with large subsidence in the middle of the working face, only a maximum deformation value of 0.3 m is obtained (Figure 5), which is obviously underestimated. The Stacking-Offset can capture larger deformation values, observing a maximum LOS direction deformation of 3 m in the central subsidence zone of No. 31308 working face. However, due to its low accuracy, it cannot detect centimeter-level deformation, making it unable to comprehensively and accurately delineate the rock strata movement boundaries. Additionally, this method has high requirements for the correlation of SAR images and is sensitive to the computational parameters set, resulting in the ability to only detect deformations in certain areas (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Deformation in the mining area synthesized from the subsidence boundary by the Stacking-InSAR method and maximum deformation value monitored by the Stacking-Offset method (data source: PALSAR-2, 24 January 2022–5 September 2022, including six SAR images).

Therefore, a combination of two methods—small gradient deformation areas measured using Stacking-InSAR phase measurements (black solid line in Figure 8) and large gradient deformation measured using Stacking-Offset measurements (deformation base map revealing in Figure 8)—is used to characterize the 3D deformation field of coal mining rock strata movement.

According to the aforementioned results, the surface data obtained from SAR processing can rapidly, comprehensively, and accurately present the extent and degree of ground surface deformation while saving a significant amount of manpower and re-sources compared to traditional observation stations and field surveys. For the two types of SAR data, multiple SAR methods and processing technologies were combined to maximize their advantages in enhancing monitoring effectiveness. Compared to Sentinel-1 data, the long-wavelength PALSAR-2 data maintains high coherence in vegetated areas and exhibits stable interferometric effects across all seasons. While the traditional InSAR method allows for rapid calculations, the Offset method compensates for the loss of coherence in areas with large gradient deformations due to coal mining, achieving meter-level deformation measurements in the central subsidence area of the working face. Therefore, for mining-induced surface deformation marked by both extensive coverage and steep gradients, the strategy proposed in this study reconciles observation efficiency with accuracy. It overcomes the limitations inherent in relying on a single method or data source, demonstrating its practical value.

4.2. Characteristics of Mining-Induced Rock Strata Movement

4.2.1. Verifying SAR Processing by Correlating InSAR Results with Mining Progress and Ground Fissures

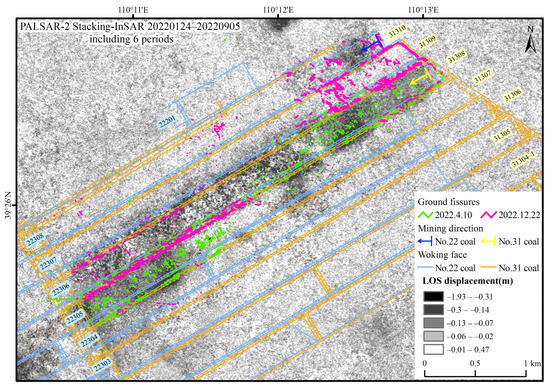

The main manifestations of mining-induced ground damage include ground fissures, collapse pits, and collapse troughs. In UAVs optical images, ground fissures are widely distributed and exhibit significant regularity in ground subsidence, serving as an important indicator of strata movement during coal mining. Based on UAV aerial images captured on 10 April 2022, and 22 December 2022, mining-induced ground fissures are identified using the DRs-UNet deep learning method [36,37]. The ground fissures are overlaid and compared with the ground deformation revealed by the Stacking-InSAR method using the PALSAR-2 data (24 January 2022–5 September 2022, a total of 6 SAR images) for validation (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Comparison and verification of the deformation resolved by the Stacking-InSAR method using PALSAR-2 data (24 January 2022–5 September 2022, including six SAR images) and ground fissures extracted from UAV images.

The last 1/3 section of the No. 31307 working face was mined from late July to October 2021. The InSAR image shows that the deformation is relatively small, indicating that it is in the post-mining deformation decay stage. The Stacking-InSAR observations record the residual surface deformation during the late post-mining period. Surface fissures develop densely and exhibit a clear pattern: above the laneway on both sides of the working face, the parallel fissures aligned with the mining direction are predominant, while straight fissures perpendicular to the mining direction are found in the middle of the working face. This is because the thicker the loose overburden layer, the smaller the surface deformation, but the range of the surface moving basin increases; when the loose overburden layer consists mainly of clayey soil, the likelihood of ground fissures appearing increases. The loose layer in this area is relatively thick, with the thickest known section reaching 62.45 m, and the bottom 12.37 m consisting of silty clay, resulting in pronounced fissures.

The No. 31308 working face was mined from November 2021 to September 2022. The InSAR image for the first 1/2 section of the working face (mining from November 2021 to March 2022) shows relatively large deformation and good coherence, particularly in the subsidence basin centered around January to February 2022. In this area, surface fissures are densely developed and exhibit a clear pattern. The InSAR image of the last 1/2 of the working face (mining from April 2022 to September 2022) shows significant ground deformation, and the subsidence area in the middle of the working face has lost coherence due to the large deformation gradient. The loose layer in this area is relatively thin, at 51.82 m or even thinner, and the surface is covered with dense low shrubs and grasses. There are few ground fissures, and they are not clearly patterned, mainly consisting of fissures parallel to the laneway.

At the northeastern part of the No. 22308 working face (directly above the No. 31310 working face) in the No. 22 coal seam, near the open-cutting, the mining period was from June to September 2022. The InSAR image shows an elliptical light gray to dark gray subsidence basin centered on July 2022. This area has fewer surface fissures, attributed to the sandy soil with regularly planted trees, allowing fissures to be filled and covered by loose sand easily. Nevertheless, the InSAR image shows good interference quality, revealing the elliptical surface deformation basin.

Near the open-cut area of the No. 31309 working face, the mining period is from the end of September to December 2022, and the ground fissures are captured by UAVs aerial photographs taken in December 2022. Since it is outside the data collection timeframe of PALSAR-2, no deformation is displayed on the InSAR map.

Overall, the degree and extent of surface deformation observed by the Stacking-InSAR method using PALSAR-2 data from 24 January 2022 to 5 September 2022, closely correspond with the mining-induced surface fissures interpreted from UAV optical imagery captured in April and December 2022. Spatially, there is a good relationship and a clear distribution pattern: above the laneway on both sides of the working face, predominantly parallel fissures align with the mining direction (same as the strike of the working face), while in the center of the working face, most of the fissures are perpendicular to the mining direction. Surrounding the surface deformation of the rock strata movement basin are inner arcuate ground fissures in the shape of “O.” Temporally, it closely corresponds to the progress of mining monthly and the range of excavation. Even in regions with fewer ground fissures, surface deformation can be effectively observed, making it a valuable supplementary observation method for such regions. This validates the effectiveness and accuracy of InSAR in monitoring coal mining-induced rock strata movements.

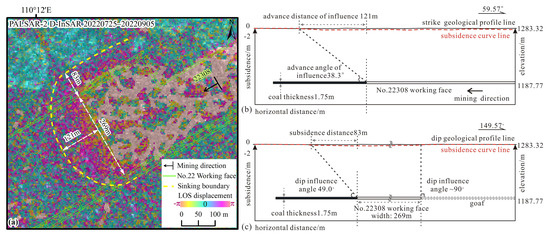

4.2.2. Advance Influence Angle Calculation (Angular Parameter Inversion)

As the working face advances, the area affected by surface movement continues to expand. The dynamic moving basin is a basin formed during the advancement of the working face. During this advancement, the ground surface in front of the working face subsides due to mining activity, a phenomenon known as advance influence. The advance influence distance refers to the horizontal projection distance between the ground subsidence boundary (defined as a subsidence of 10 mm) affected by mining activities in front of the working face and the boundary of the goaf. The angle between the line connecting the point where the surface begins to move (defined as a subsidence of 10 mm) in front of the working face and the horizontal line on the coal pillar side is referred to as the advance influence angle. By extracting angular parameters of ground surface movement, one can intuitively understand the degree and morphological characteristics of the impact of the goaf on the surface moving basin during different mining stages, thereby effectively grasping the general laws and characteristics of surface subsidence.

The mining of the No. 22308 working face began in June 2022, with solid coal on the north side and the historical goaf of the No. 22307 working face (mined from January to April 2020) on the south side. The mining depth is 95.55 m, with a designed length of 4421 m. There is one instance of widened mining of the working face, which starts with a width of 174 m at the initial open-cutting. After mining 695 m, the width of the working face is increased to 269 m. Based on the surface subsidence basin boundary extracted from InSAR observation results, the advance influence distance is approximately 121 m, and the northern subsidence boundary lies 83 m outside the horizontal projected outline of the goaf boundary (Figure 10a). The advance influence angle in the strike direction of the No. 22308 working face is calculated to be approximately 38.3° (Figure 10b). The dip influence angle adjacent to solid coal on the north side of the working face is 49.0° (Figure 10c). The south side of the working face is affected by the activation of the goaf, resulting in a nearly vertical collapse, with a dip influence angle approaching 90°.

Figure 10.

Advance influence angle calculation. (a) Surface deformation at the widening section of the No. 22308 working face from 25 July 2022, to 5 September 2022 (42 days), revealed by the D-InSAR technique using PALSAR-2 data; (b) Schematic diagram of the advance influence angle calculation for the No. 22308 working face (along the strike section); (c) Schematic diagram of the dip influence angle calculation for the No. 22308 working face (along the dip section).

5. Discussion

5.1. The Impact of Different SAR Data on Ground Deformation Monitoring

Comparing the D-InSAR interference images from Sentinel-1 (C-band) and PALSAR-2 (L-band) with similar time intervals, it can be observed that the shorter wavelength of Sentinel-1 SAR data performs well in winter and spring when surface vegetation is sparse. However, during the summer and autumn, the interference effects are adversely affected by the dense vegetation, and decoherence occurs. The C-band wavelength of Sentinel-1, being relatively short, is sensitive to surface deformation and can accurately capture the residual deformation of the surface after mining activities. However, in regions experiencing rapid and extensive deformation, it is prone to coherence loss, making it difficult to obtain true and accurate subsidence values at the center of the basin (Figure 11a). Due to the longer wavelength and high spatial resolution of PALSAR-2, it possesses good penetration and coherence, enabling satisfactory interference results even in the summer and autumn, which are characterized by lush vegetation. These make it particularly suitable for regions experiencing rapid surface deformation; however, it is not sensitive to minor surface deformations (Figure 11b).

Figure 11.

Comparison of D-InSAR interference images between Sentinel-1 and PALSAR-2 (mining at No. 31308 working face from January to February 2022). (a) Sentinel-1 data with a resolution of 30 m; (b) PALSAR-2 data with a resolution of 3 m.

Previous studies have demonstrated through comparisons of multi-source SAR data that the longer L-band is less sensitive to changes caused by vegetation than the shorter C-band. Therefore, L-band data is more suitable for monitoring subsidence in mining areas with relatively dense vegetation [38]. The PALSAR-2 data show greater robustness than Sentinel-1 data in low coherence areas. Additionally, the longer wavelength is more appropriate for observing surface deformation in regions with rapid large gradient deformations, capable of detecting larger subsidence values. It is less affected by phase aliasing caused by significant deformation gradients and by time decorrelation due to changes in surface scattering characteristics over time [39,40].

Furthermore, from the perspective of resolution comparison, the D-InSAR image of Sentinel-1 appears as a blurred and incomplete near-circular shape, with the center being unwrappable due to significant deformation, presenting a chaotic pattern of deformation. There is a certain amount of residual deformation in the direction of the working face, and the interference fringes caused by mining are almost impossible to identify in the image (Figure 11a). PALSAR-2 D-InSAR images have high resolution and provide a clearer and more complete characterization of deformation areas. They can distinctly illustrate the elliptical shape of the subsidence basin caused by mining activities. The central area of coherence loss can also serve as indirect evidence of significant deformation in the subsidence basin. The position of the edges corresponds with the location of the coal mining area, indicating a clear relationship between mining activities and the measured displacements, which aligns with the deformation characteristics of the subsiding basin during the advancement of the working face (Figure 11b).

5.2. Applicability of Different Methods

Previous research indicates that the range of mining-induced subsidence basins in the Yushenfu coal mining area of Shaanxi is generally larger than that of the working face. In flat terrain, the basin tends to have a flat-bottomed shape in the center, with gentle slopes along the periphery of the working face formed due to subsidence, usually with a depth of 1–3 m [41]. This study utilized D-InSAR, Stacking-InSAR, SBAS-InSAR, SBAS-Offset, and Stacking-Offset methods to calculate the range of the subsidence basin and the LOS deformation of the working face in the SGT mining area. To validate the accuracy of the surface deformation values obtained from SAR data processing, a comparison with field observational data from the SGT mine and other mines in the region is conducted (Table 4). The layout and spatial relationships of observation stations used for verification on No. 31305 working face are shown in Figure 2. The No. 31305 and No. 31308 working faces are only 560 m apart and share nearly identical mining geological conditions. These coal mines are all located in the Shendong area, employing the same mining methods and possessing similar geological conditions, buried depths, and coal seam thicknesses. Therefore, they can serve as ideal comparative validation data.

Table 4.

Comparison of Surface Deformation at Shendong Coal Field.

D-InSAR is the most fundamental measurement method for using the difference between two SAR images, facilitating the highlighting of details and abrupt changes. The Stacking-InSAR enhances the observation range through the adjustment and complement of multi-period data; however, the maximum deformation obtained after averaging is only 0.3 m, which is lower than the actual subsidence of 2–3 m. The SBAS-InSAR utilizes InSAR time-series decomposition for sequential observations to measure the growth process of surface deformation range. This method is prone to the smoothing of deformation features due to the effects of time-series decomposition.

To facilitate comparison, we standardized the color ramp for the monitoring results of Stacking-InSAR and SBAS-InSAR. The deformation areas obtained using both processing strategies are similar. The Stacking-InSAR model calculates the linear deformation rate through weighted unwrapped differential interferograms without selecting coherent points, while SBAS-InSAR requires the selection of points that maintain high coherence over a certain time span, discarding points with lower temporal coherence [23]. Consequently, in areas of surface deformation covered by dense vegetation, the point density monitored by SBAS-InSAR is sparser than that of Stacking-InSAR, and the values of surface deformation are smaller (the maximum deformation values in the subsidence areas for both technologies from January to September 2022 are 0.15 m and 0.3 m, respectively). Compared to the subsidence data from nearby coal mines in Table 4, it is evident that both InSAR methods based on these strategies are not suitable for observing large deformation values.

The Offset method proves effective for monitoring substantial surface deformation values. Nevertheless, as it relies on the pixel displacement within SAR images, its accuracy is susceptible to various factors, including dense vegetation coverage, alterations in ground features, and agricultural activities. These elements can readily induce a loss of coherence. Additionally, when compared to InSAR techniques, the Offset method exhibits comparatively lower resolution. The SBAS-Offset allows for the observation of the overall development process of large gradient deformations. The SBAS-Offset result for the same location in the significant subsidence area at the center of the No. 31308 working face from January to September 2022 is 1.53 m, while the Stacking-Offset result is 2.96 m. The maximum LOS deformation values measured by the two processing technologies are approximately 2 m and 3 m, respectively.

Additionally, considering that the adjacent No. 31307 working face completed its mining in 2021, the subsidence of No. 31308 working face is relatively sufficient. The No. 31305 working face is located 560 m away from the No. 31308, and the geological conditions are similar. Therefore, the surface measurement data from the No. 31305 working face holds important reference value, and the LOS surface deformation values obtained from the Offset method are close to the field observation value of the No. 31305 working face.

Based on the observational results from the SGT coal mine and the Shendong area, the LOS maximum subsidence of 2–3 m measured using the Offset method under different processing strategies demonstrates a high level of reliability.

In conclusion, by comparing and analyzing the monitoring results of different SAR processing methods with the progress of underground mining operations, it is observed that the movement of the ground subsidence basin detected via SAR processing is spatially and temporally consistent with the advancement position of the underground mining. The InSAR results accurately identify the edges of the deformation areas, demonstrating strong robustness and sensitivity to minor deformations. It is suitable for straightforward and precise observation the deformation locations, boundaries and variations in ranges of rock strata movements with excavation progress. However, significant deformation can lead to decorrelation caused by excessive phase gradient, making it impossible to obtain the maximum deformation value. Unlike the phase measurement principle of InSAR, the Offset method relies on the dense and fine registration of pixels in two SAR images, allowing for the measurement of slant range displacements with sub-pixel accuracy, ranging from the meter level to tens of meters [28,30,46,47]. Therefore, if the deformation in the mining area is substantial, reaching several tens of centimeters or more (sub-pixel posting of a SAR image), measurements using the Offset method can closely approximate the true value [12]. This is particularly suitable for areas of significant deformation, especially the central subsidence zone of working faces, and can further reveal the centrally symmetric morphological structure of surface movement basins. Nevertheless, a limitation is that the Offset method has relatively weaker robustness. Differential processing can intuitively and quickly display short-term deformations of extensive areas affected by coal mining, but are susceptible to atmospheric effects. Stacking processing can stably demonstrate the surface deformations caused by long-term mining, while SBAS processing can present the development process of mining-induced deformations. However, both processing techniques have requirements regarding the number of D-InSAR interferometric pairs or may encounter issues with robustness.

Therefore, the combination of InSAR and Offset method, along with the application of differential, Stacking, and SBAS processing techniques as needed, is more reasonable for monitoring surface deformations in mining areas. This enables a more accurate delineation of the subsidence deformation range and surface displacement values, thereby revealing the surface deformation process associated with underground extraction. This can be analyzed in conjunction with the development of ground fissures and the advancement of mining, assessing the impact of underground coal mining on rock strata movement.

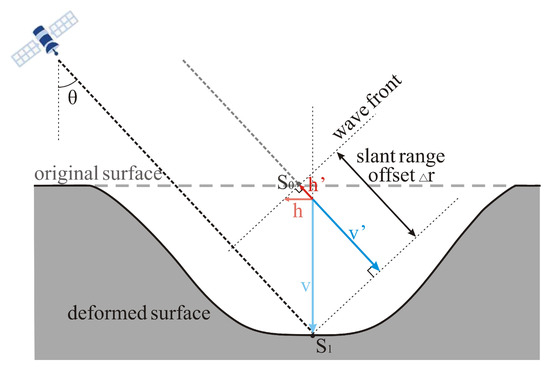

5.3. Main Sources of Measurement Errors

Surface deformation in mining areas occurs in three-dimensional space, comprising vertical, east–west, and north–south directions. The azimuth of SAR affects the sensitivity of the radar sensor to deformation, and vertical displacement usually relates to two LOS deformation measurements (ascending and descending). This requires acquiring identical SAR data in two directions over the same time period. However, using SAR data from a single orbital direction in this study only allows for the acquisition of one-dimensional LOS deformation in the mining area, and the observed deformation information is insufficient to accurately represent the surface subsidence in the mining area.

Surface deformation is a three-dimensional phenomenon. Utilizing one-dimensional observations from InSAR for three-dimensional surface deformation cannot differentiate vertical from horizontal displacements. Therefore, prior knowledge, such as the laws of coal mining induced rock strata movement and parameters for horizontal displacement, is employed to estimate the error in horizontal displacement. In Equation (1), b is the horizontal displacement coefficient, Ucm and Wcm represent the maximum horizontal displacement value and the maximum surface subsidence value, respectively, under conditions of full extraction [48]. In Equation (2) and Figure 12, S0 is the observation point on the original ground surface, and S1 is the position of the observation point after ground deformation. The h and v represent the horizontal and vertical displacements, respectively, that occurs between two SAR images can be calculated from the slant range difference Δr. The h’ and v’ denote the horizontal and vertical displacement components observed by satellites in the LOS direction, and θ is the incidence angle. Using the horizontal displacement coefficients of the Bulianta (b = 0.127) and Daliuta coal mines (b = 0.29) in the Shendong coalfield as reference values [48] in Equation (2), the ratio of the horizontal displacement h’ to the total displacement in the LOS direction (h’ + v’) is calculated to be 11.6–21.3% (θ = 43°). And the proportion of the vertical displacement v’ to the total displacement in the LOS direction calculated from Equation (3) is 78.7–88.4%. It is evident that the horizontal displacement accounts for a very small proportion of the total displacement, which is primarily contributed by vertical displacement.

Ucm = b·Wcm

Figure 12.

Geometry of slant range offset measurement relative to vertical and horizontal deformation.

Therefore, we assume that the deformation in the LOS direction is entirely caused by vertical subsidence of the surface. This calculation of vertical deformation is based on geometric imaging principles, which undoubtedly introduces some error. Assuming that horizontal deformation can be neglected, the vertical deformation (v) that occurs between the two SAR images can be calculated using the slant range difference Δr, as in Equation (4) [12]. Based on the above equation, we find that the maximum vertical subsidence in the central subsidence zone of the mining area approximately ranges from 2.7 to 4.1 m (θ = 43°, and the Δr derived from the SBAS-Offset method and the Stacking-Offset method is 2 m and 3 m, respectively). It should be noted that the surface subsidence process in coal mining areas is highly complex and nonlinear [49]. Directly converting LOS deformation to vertical subsidence using the cosine of the incident angle may slightly affect the accuracy of the estimated subsidence.

In the processing of the Offset method, unlike the phase-based measurements used in traditional interferometry, the vertical baseline is not the primary limiting factor for offset estimation; instead, the temporal variation in the SAR backscattering intensity images serves as the main constraint. Since offset estimation relies on intensity cross-correlation algorithms, variations in environmental factors such as near-surface humidity and vegetation can alter the SAR backscattering echoes, thereby reducing the accuracy of the offset estimation. Therefore, using SAR data obtained in winter, when vegetation and precipitation are relatively sparse, results in more accurate offset calculations.

In addition, the SBAS method uses a temporal decomposition approach for time series observation of surface deformation, which generally assumes that the deformation exhibits uniform or linear characteristics. However, the actual ground subsidence in mining areas can experience sudden collapses, resulting in surface deformation with large gradients and nonlinear features. Thus, the use of the SBAS method may lead to the smoothing of deformation characteristics, which is also reflected in the results obtained through the Stacking and SBAS technologies in this study. For PALSAR-2 data (January–September 2022), the Stacking-Offset method shows a max LOS deformation of ~3 m in the central subsidence area of No. 31308 working face, while the SBAS-Offset method indicates ~2 m. Although both methods yield reliable meter-level substantial subsidence, the deformation value obtained from the Stacking-Offset is larger. This is likely due to the SBAS process smoothing the data, resulting in smaller values for the same time and location.

5.4. Discussion of the Influence Angle

The advance influence angle calculated by InSAR for No. 22308 working face is 38.3°, which is smaller compared to the generally reported values of 40° to 60° for this region (Table 5). Previous observations indicated that the advance influence angle for the No. 31305 working face at the SGT mine is 47.4°, while it ranged from 44° to 55° for the Selian No. 2 coal mine, located approximately 20 km away. The reasons for this difference are analyzed as follows.

Initial mining and repeated mining. No. 31305 working face is a second mining operation, where the overlying No. 22 coal seam was mined seven years ago, leaving behind internal fractures and goaf that have experienced subsidence. During the re-mining of the No. 31 coal seam beneath the No. 22 coal seam, the existing fractures in the rock strata lead to further subsidence, which is why the advance influence angle for the secondary mining is relatively large. While the advance influence angle for No. 22308 working face, which is being mined for the first time, is smaller.

This is also reflected in the subsidence range and angles observed at the No. 22308 working face and its adjacent working faces. InSAR results indicate extensive surface deformation in the adjacent unmined solid coal on the northern side, and the northern subsidence boundary lies 83 m outside the horizontal projected outline of the goaf boundary. The dip influence angle adjacent to the unmined solid coal on the north side is calculated to be 49.0°. Conversely, on the southern side, near the historical goaf of No. 22307 working face, significant gradient deformation caused decoherence along the boundary of the laneway, which is presumed to represent a collapse trough associated with vertical subsidence.

Degree of mining activity. In the western mining area, during insufficient mining, the advance influence angle decreases as the mining extent increases; however, once sufficient mining is achieved, the advance influence angle begins to show an increasing trend [50]. The No. 22308 working face is currently being mined and is in a state of insufficient mining, resulting in a relatively small value for the advance influence angle.

Overlying strata lithology and the working face advance rate. The weaker the overburden rock, the smaller the advance influence angle; conversely, the greater the advance rate of the working face, the larger the advance influence angle [51]. Near the open-cutting of No. 22308 working face, there is an area of aeolian sand, characterized by a loose surface layer and weak overburden, which results in a relatively small advance influence angle. The overburden in the western mining area consists of weakly cemented rock, characterized by strong expansion and easy disintegration in the early stage and easy to be compacted in the later stage [50,52]. During the initial stage of mining (insufficient mining), the fractured-caving zone of the overlying rock is relatively high, and the rock mass remains uncompacted, leading to mitigated surface subsidence and a larger influence range of the surface moving basin, as reflected in a larger advance influence distance and a smaller advance influence angle. In the later stages of mining (sufficient mining), the weakly cemented rock is more easily compacted, allowing voids within the rock mass to be rapidly transferred to the surface, accelerating surface subsidence, and even causing a cut-and-fall subsidence. The influence range of surface movement basins decreases, as evidenced by the dip influence angle of No. 22308 working face adjacent to the southern historical goaf approaching 90°, resulting in nearly vertical collapse.

Differences in measurement methods. The advance influence angle is generally measured by installing surface observation devices (such as total stations or leveling instruments) in the mining area, with specific points determined based on subsidence values of 10 mm. Although this method is more precise, the data obtained from observation points located along the observation line at the center of the working face are point data. In contrast, the results derived from InSAR are surface data. The advance influence angle is determined through a comprehensive assessment of the overall deformation field data from InSAR, allowing for a more comprehensive representation of the range and extent of surface deformation compared to point data. This leads to a broader determination of the boundary limits and subsequently smaller values for the influence angle.

Currently, dynamic studies of surface mining subsidence primarily reference angular parameters to reflect the range, magnitude, and extent of the influence of goaf on surface movement basin. The advance influence angle can predict the impact range on the surface ahead during the advancement of the working face. Therefore, using the InSAR method to calculate the influence angle can serve as a reference, aiming to provide a methodological approach for efficient and comprehensive observation of surface deformation in mining areas and for the rapid calculation of surface movement parameters. This facilitates the acquisition of important parameters (such as advance influence distance and advance influence angle) that can be used to predict the degree of mining subsidence, thereby providing significant reference value for the dynamic protection of surface structures and facilities in the western mining area.

Table 5.

Comparison of advance angle of influence in the Shendong coalfield.

Table 5.

Comparison of advance angle of influence in the Shendong coalfield.

| No. | Coal Mine | Working Face No. | Dip Length/Strike Length (m) | Dip Angle (°) | Buried Depth (m) | Coal Thickness (m) | Advance Distance of Influence (m) | Advance Angle of Influence (°) | Data Acquisition Method | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SGT | 22308 | 269, 4420 | 0° | 95.5 | 1.75 | 121 | 38.3 | D-InSAR | This study |

| 2 | SGT | 31305 | 285.2, 4583 | 1–3° | 140 | 2.7 | 131.5 | 47.4 | field survey | Internal work report for the mining area |

| 3 | Bu’ertai | 22201–1/2 | 300, 3950 | 1–3° | 260 | 2.2–2.9 | / | 50.5 | SBAS-InSAR | [53,54] |

| 4 | Bu’ertai | 22201–1/2 | 300, 3950 | 1–3° | 260 | 2.2–2.9 | / | 53.5 | D-InSAR | [53,54] |

| 5 | Daliuta | 52304 | 301, 4547.6 | 1–3° | 230 | 6.6–7.3 | 88.5–146 | 57.59–68.95 | D-InSAR | [55,56] |

| 6 | Daliuta | 52304 | 301, 4547.6 | 1–3° | 230 | 6.6–7.3 | / | 53.69 1, 48.1 2 | field survey | [55,56] |

| 7 | Daliuta | 22201 | 349, 643 | 1–3° | 73 | 3.9 | / | 50.8 1 | field survey | [57,58] |

| 8 | Selian No. 2 | 12314 | 240, 2850 | 1.8° | 398 | 3.6 | 270–408 | 44.14–55.71 | SBAS-InSAR | [50] |

Note: The coal mining uses the mechanized longwall method, and the roof management adopts the fully caving method. 1 Boundary angle in the strike direction. 2 Boundary angle in the dip direction.

6. Conclusions

The semi-arid aeolian sand environment in the northern Shendong Mining Area challenges InSAR monitoring of coal mining deformation. Focusing on the Shenmu SGT mine, this study used D-InSAR, Stacking-InSAR, SBAS-InSAR, SBAS-Offset, and Stacking-Offset methods to process PALSAR-2 (L-band) and Sentinel-1 (C-band) SAR data. The ground deformations are then analyzed and validated against coal mining parameters and field survey data. The main findings are drawn as follows:

(1) InSAR can effectively capture mining-induced rock strata movement, yet it is sensitive to factors like surface covers, wavelength, and data processing methods. For observing coal mining strata movement, it is necessary to employ two types of deformation calculation methods, InSAR and Offset, along with three calculation optimization strategies: differential, Stacking, and SBAS. This combination allows us to obtain different observational results that can meet the needs of various SAR data and observational targets in the research area.

(2) Integrating PALSAR-2 (L-band) and Sentinel-1 (C-band) data in the Shenmu SGT mine yields comprehensive observations. PALSAR-2 data with a longer wavelength ensures ideal penetration, robust interferometry, and a wide measurement range year-round, suitable for vegetated, high-deformation areas. Sentinel-1 data with a shorter wavelength is more sensitive to minor deformations, providing clear imaging in winter/spring and revealing finer deformation edges.

(3) Combining high-precision InSAR phase measurements with Offset methods adept at capturing large-gradient deformations provides a robust way to characterize the 3D spatial deformation field of coal mining rock strata. The InSAR method is highly robust and sensitive to minor deformations, enabling straightforward and accurate measurement of deformation positions, boundaries, and range changes with mining progress. Although the Offset method is relatively less robust, it can accurately measure true large deformations. This capability not only reveals the extent and variations in surface movement but also, more critically, uncovers the centrally symmetric structural morphology of the surface movement basin. It responds sensitively to centimeter-scale rock movement features like “flexure” and can further facilitate the analysis of issues such as underground pressure, air leakage, and water seepage.

(4) The fusion of InSAR and offset observations provides an effective means to accurately unveil mining-induced subsidence. Surface deformation monitored by InSAR aligns well with ground fissures identified in UAV imagery, showing strong spatial and temporal correlations with monthly mining progress. This combination enables us to obtain the key surface movement parameter. Under the SBAS and Stacking strategy, the Offset method measures maximum LOS deformations of ~2 m and ~3 m, close to field surveys (2.14 m) and prior data. InSAR results indicate a 121 m advance influence distance and an advance influence angle of 38.3° for the No. 22308 working face.

In summary, InSAR technology can monitor mining-induced ground subsidence on a cost-effective and operational basis. Through the optimization in the three areas of data, processing methods, and application analysis, the range, accuracy, and reliability of observations can be improved, making it an important tool for research on coal mining strata movement and surface subsidence. This study successfully addresses the dual challenge of extensive coverage and steep gradients in mining-induced surface deformation, achieving a balance between observation efficiency and accuracy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.T. and X.Y.; methodology, X.Y. and T.T.; software, Z.Z.; validation, T.T., X.Y. and X.T.; formal analysis, T.T.; investigation, T.T., X.Y. and X.T.; resources, X.Y., Z.W., Z.Z.; data curation, T.T. and Z.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, T.T.; writing—review and editing, X.Y. and T.T.; visualization, T.T.; supervision, X.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CCTEG Ecological Environment Technology Co., Ltd., project 2022-2-ZD004, National Institute of Clean-and-Low-Carbon Energy project NICE_RD_2021_220, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Science and Technology Program project 2023YFSW0022 and China Geology Survey Project DD20230600105.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the study is available upon request to the author.

Conflicts of Interest

Z.W. was employed by CCTEG Ecological Environment Technology Co., Ltd., the other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jiang, L.; Lin, H.; Ma, J.; Kong, B.; Wang, Y. Potential of Small-Baseline SAR Interferometry for Monitoring Land Subsidence Related to Underground Coal Fires: Wuda (Northern China) Case Study. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wen, G.; Dai, L.; Sun, H.; Li, X. Ground Subsidence and Surface Cracks Evolution from Shallow-Buried Close-Distance Multi-Seam Mining: A Case Study in Bulianta Coal Mine. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2019, 52, 2835–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Qiu, H.; Ma, S.; Liu, Z.; Du, C.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, M. Slow Surface Subsidence and Its Impact on Shallow Loess Landslides in a Coal Mining Area. Catena 2022, 209, 105830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]