1. Introduction

As a technological revolution after RTK and network RTK technology, Precise point positioning (PPP), with advantages such as stand-alone operation and flexible mobility, is widely used in location service [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Nevertheless, GNSS PPP typically requires tens of minutes for convergence without a precise atmospheric parameter, presenting a significant hurdle to the real-time applications. Benefiting from the rapid geometric changes, Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellites can expedite the convergence process of GNSS PPP [

6,

7]. Thus, LEO-augmented PPP has attracted considerable attention from researchers, which is poised to be a pivotal component of the next-generation satellite navigation system [

8,

9,

10,

11]. The basic mathematical model of LEO-augmented PPP is established based on the conventional GNSS observation model. In addition, the contribution of the LEO navigation enhancement constellation to PPP has been systematically analyzed in previous studies [

12,

13,

14]. Ke et al. (2015) simulated and compared the positioning accuracy and convergence time of GPS-only PPP, GPS/GLONASS PPP and GPS/LEO PPP, which shows that LEO satellites have more contribution to PPP convergence than MEO satellites [

15]. Ge et al. (2024) analyzed the impact of LEO satellites on the spatial geometry based on simulated LEO and real GNSS data, and evaluated the LEO constellation-augmented Navigation performance with ionosphere-free (IF), undifferenced and uncombined (UDUC), and ionosphere-weighted (IW) models [

16]. Li et al. (2019) comprehensively analyzed the influence of constellation configuration with simulation experiments [

17]. Li et al. (2023) and Chang et al. (2025) analyzed the impact of LEO on PPP in terms of convergence time and positioning accuracy, integrating CENTISPACET™ satellites with GNSS [

18,

19]. The above studies demonstrate the superiority of LEO-augmented PPP in convergence.

Despite the similarities in mathematic models between LEO-augmented and traditional PPP, the unique challenges introduced by the deployment of new LEO constellations, which have also become studies’ focus beyond convergence performance. The technology and experience of utilizing space-borne GPS data for post-processing precise orbit determination of satellites, both domestically and internationally, have reached a high level of maturity. Satellite series such as GOCE, CHAMP, GRACE, HY2A, and the JASON series satellites, among others, are all capable of achieving centimeter-level orbit accuracy [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. The LEO satellite orbit calculated by on-board GNSS data is referenced to the center of mass, and the clock error is relative to the LEO onboard GNSS receiver [

25,

26,

27,

28]. To unify the spatial relationship in LEO-augmented PPP, it is necessary to convert the center-of-mass orbit to the phase-center references of the downlink navigation signals. Hence, the high-precision phase-center offsets (PCO) of the downlink navigation signals with respect to the center-of-mass must be determined to convert the orbit parameter. Typically, there is an initial calibration value for the downlink signal PCO on the ground. The clock error relative to the onboard GNSS receiver must also be converted to the downlink signal transmitter, which we call the downlink signal transmitter equipment delay relative to the onboard GNSS receiver here. Both types of hardware delays can be calibrated on the ground before launching LEO satellites. For example, Li et al. (2023) adopted factory-calibrated downlink antenna PCO values for correction in the CENTISPACET-based LEO augmentation experiments [

18]. However, during in-orbit operation, factors such as structural deformation and shifts in the satellite’s center of mass can cause the actual phase center to deviate from the pre-launch calibration. Such deviations may reach several centimeters, and equipment delays may also drift over time, making it impractical to rely solely on static calibration values for long-term applications [

29]. Moreover, due to the low orbital altitude, rapid geometric variation, and short ground visibility of LEO satellites, along with the foreseeable limitation in the number of ground stations capable of receiving LEO navigation signals within China, it is essential to develop dedicated algorithms for estimating the downlink signal PCO and equipment delay.

The equipment delay, as an inherent component of the pseudorange and carrier-phase measurements from downlink signals received at ground monitoring stations, exhibits different physical characteristics from the downlink signal transmitting antenna phase center offset (PCO). While the PCO is generally a stable geometric parameter, the equipment delay is more susceptible to temperature variations and electronic fluctuations, showing time-varying behavior. Therefore, these two parameters should be estimated simultaneously using different modeling strategies.

In this context, GNSS observations can provide high-precision solutions for station-related parameters such as receiver clock offset and ZTD, serving as important auxiliary information for the estimation of LEO downlink parameters [

18,

30]. However, when combining GNSS and LEO observations, inter-system biases (ISB) between the two systems may arise and must be properly accounted for. Liu et al. (2024) [

30] explored the feasibility of jointly estimating the downlink signal PCO and equipment delay of LEO satellites using pseudorange and carrier-phase observations from GNSS and LEO downlinks. In their simulations based on Sentinel-3B and Sentinel-6A downlink data over 10 globally distributed stations for 6 processing days, the post-processed least-squares solution equipment delay 3.5 mm for PCO and 3 cm for equipment delay. Additionally, Li et al. (2023) [

18] proposed a “Three-Step Approach” in their experiments with CENTISPACET satellites. This method first uses GNSS data to estimate station clock offsets and tropospheric delays, then fixes these parameters to estimate LEO satellite equipment delays and ambiguities via static PPP, and finally derives epoch-wise delay corrections. This approach is particularly effective under conditions with only a small number of LEO satellites.

Although Liu et al. (2024) and Li et al. (2023) have made valuable contributions to the estimation of downlink signal PCO and equipment delay for LEO satellites, their studies are primarily based on single or a small number of experimental satellites under static conditions [

18,

30]. For practical deployment in future large-scale LEO navigation constellations, several key limitations remain:

- (1)

Existing approaches typically assume that receiver clock offsets and tropospheric delays at ground stations are already estimated using GNSS data, and that LEO observations serve solely to estimate satellite-side parameters. The potential of large volumes of LEO observations to enhance the estimation of ground station parameters has not been explored, particularly under constellation-scale expansion.

- (2)

There is currently no comprehensive evaluation of how key system factors—such as LEO satellite orbital altitude, constellation size, and orbit/clock bias error levels—affect the accuracy of PCO and equipment delay estimation. This limits support for constellation design and performance optimization.

- (3)

Given the practical limitations of ground station deployment in China, it remains unclear whether reliable estimation of LEO downlink signal PCO and equipment delays is achievable under conditions with only a small number of regionally ground stations within China.

To address the aforementioned issues, this study proposes a joint estimation method for the downlink signal PCO and equipment delay of LEO satellites. The method builds upon pseudorange and carrier-phase observations collected from ground stations simultaneously tracking both LEO and GNSS downlink signals. In the first stage, a batch least-squares strategy is employed to estimate the parameters of the PCO and posteriori equipment delay. With the estimated PCO parameters fixed, the equipment delays are further refined using a PPP approach. Notably, the method is designed with practical constraints in mind, particularly the limited deployment of ground stations in China. Therefore, the estimation framework is implemented and validated using only a limited number of regionally distributed ground stations within China. Additionally, this study conducts a systematic evaluation of how factors such as orbital altitude, constellation size, number of ground stations, and orbit/clock bias errors affect the estimation performance.

2. Downlink Signals Transmitting Antenna PCO and Equipment Delay Estimation of LEO Satellites

As mentioned before, the LEO satellite orbit and clock error are estimated with respect to the center-of-mass rather than the phase-center references of the downlink navigation signals, which is essential to consider the PCO and equipment delay of downlink signals for LEO satellites.

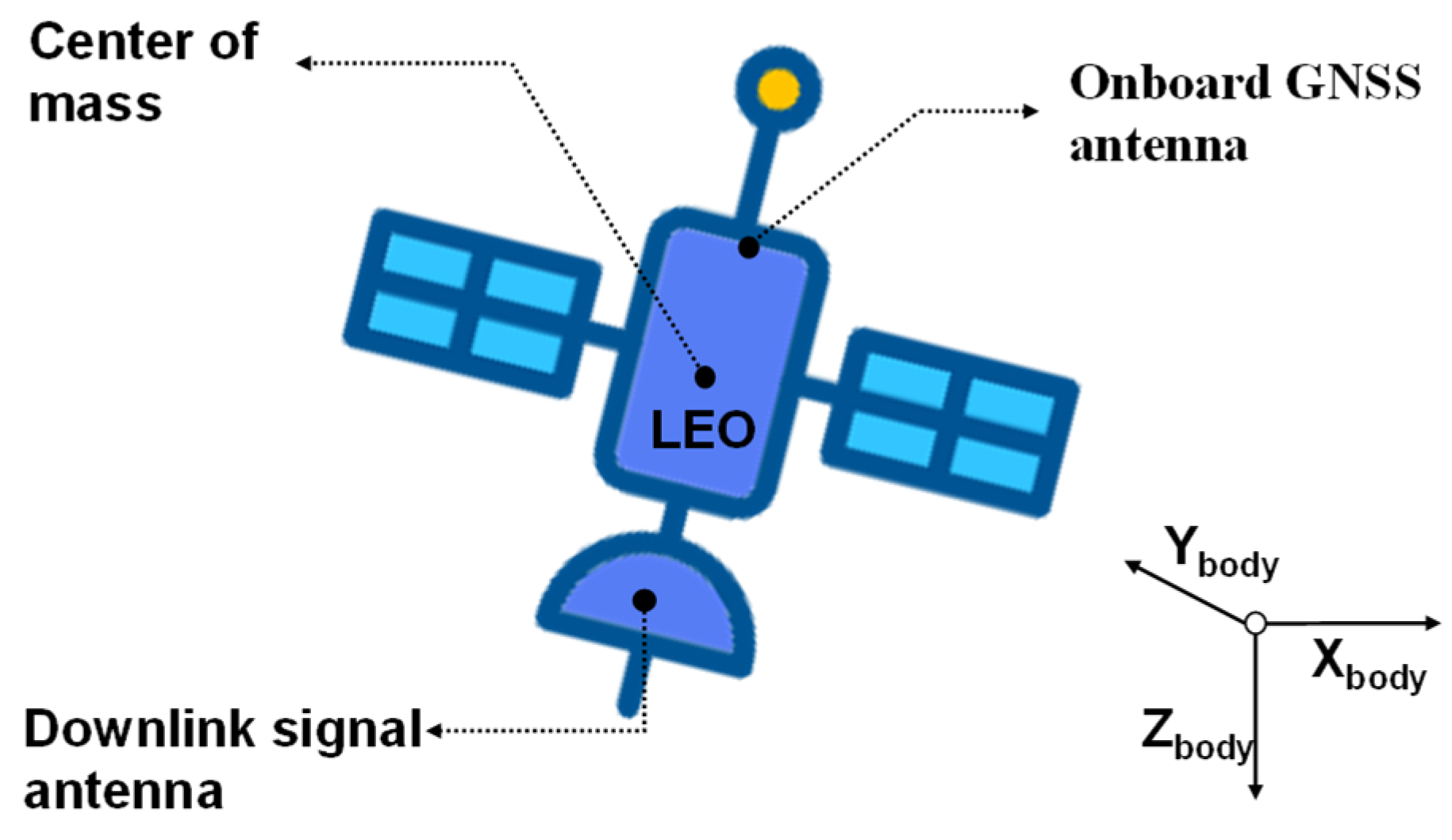

Figure 1 shows spacecraft body-fixed system and different antenna systems of the LEO satellite. To ensure the reliable estimation of these parameters, it is necessary to incorporate accurate station positions, station clock bias, and tropospheric delay corrections. GNSS observations provide high-precision solutions for these related parameters, which can serve as critical auxiliary information for estimating the downlink parameters of LEO satellites. Thus, it is necessary to jointly process the GNSS satellite observations and LEO downlink navigation observations.

2.1. Mathematical Model

The LEO satellite downlink signal PCO and equipment delay are included in the pseudorange and phase observations of the ground receivers. The impact of PCO errors on downlink observations differs from that of equipment delays due to their distinct physical characteristics [

30]. Thus, the two parameters can be separated due to their distinct characteristics in observations. Since the ionosphere-free combination is commonly used in the LEO-augmented PPP, we mainly focus on the dual-frequency ionosphere-free equivalent values of PCO and equipment delay for LEO satellites.

The pseudorange and phase observation include satellite-related errors, receiver-related errors, and signal transmission-related errors. Since the relativistic effects, earth rotation effect and tide effect can be precisely corrected with model. The observation equation can be simplified as follows [

31,

32,

33,

34]:

where

s and

r denote the satellite and the ground receiver respectively;

k stands for the satellite system (BDS or LEO);

is the satellite wavelength;

is the geometric distance between the satellite antenna phase center and the receiver antenna phase center;

is the clock error;

is the Ionospheric delay;

is the tropospheric delay.

denotes the measurement noise and multipath in the satellite pseudorange observations, and

denotes the measurement noise and multipath in the carrier-phase observations, respectively.

The ionospheric-free combination can eliminate the effect of first-order ionospheric delay. Thus, the ionospheric-free combination model of the BDS satellite and the LEO satellite can be derived as follows:

with:

where

represents ionospheric-free combination;

and

are the ionospheric-free combination coefficient.

and

represent the signal frequencies used by the GNSS satellite and the LEO satellite, respectively.

The geometric distance

between the satellite downlink signal antenna phase center and the receiver phase center is calculated with the center-of-mass position for the satellite and receiver according to the PCO correction. The procedure can be depicted with the following equation [

34,

35]:

with

where

denotes the center-of-mass position vector of the ground antenna;

denotes the PCO vector of the ground receiver, defined from the receiver’s center of mass to the antenna phase center;

denote the center-of-mass position vector for the satellite;

denotes the PCO vector of the satellite in the earth-fixed system;

denotes the satellite PCO vector in the satellite-fixed coordinate systems, which can be shown in

Figure 2;

is the rotation matrix from the spacecraft body-fixed system to the earth-fixed system, which is determined by the satellite attitude control mode. The attitude model of BDS satellites follows the definition provided in the BeiDou Signal-in-Space Interface Control Documentd [

35]. All LEO satellites used in this study are assumed to be three-axis stabilized, which is consistent with the configuration of most LEO satellites deployed for navigation or Earth observation missions.

In the LEO-augmented PPP, the clock error relative to the onboard GNSS receiver must be converted to downlink signal transmitter. An equipment delay introduces the observation equation:

Under the condition of a sparse regional ground station network, where station numbers are limited and spatial geometry is weak, the observation model must be carefully adapted to ensure separability between satellite-side and ground-side parameters. An inter-system bias (ISB) term is introduced for each station to absorb residual differences between the GNSS and LEO systems. The combined use of LEO and GNSS observations enables joint estimation of receiver clock offsets, tropospheric delays, LEO satellite PCOs, and equipment delays. The systematic bias between LEO and GNSS time system is also introduced in the observation equation:

Combining Equations (2)–(7), the unified observation model for estimating the downlink signal PCO and equipment delays of the full LEO constellation can be expressed as follows:

where

h denotes the zenith projection of satellite and receiver.

According to Equation (8), LEO downlink signals the PCO and equipment delay can be estimated through jointly processing the GNSS satellite observations and LEO downlink navigation observations.

It is important to note that, in the case of single-satellite estimation, the equipment delay is strongly correlated with

. As a result, the estimated equipment delay

in a single-satellite solution inherently includes the

component, and can be expressed as

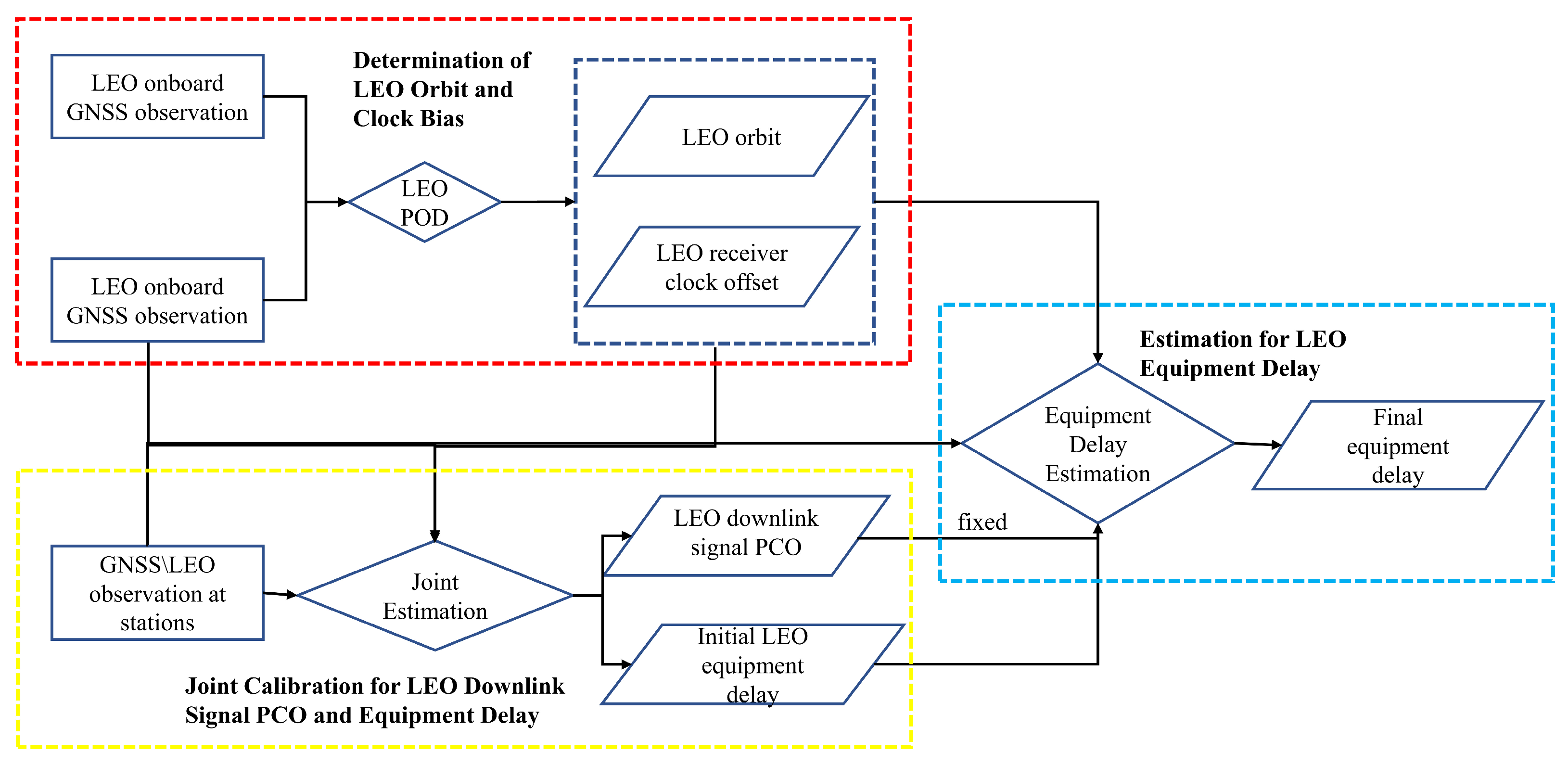

2.2. Calculation Process

Based on the above analysis, we establish a joint estimation framework for the downlink antenna phase center offset (PCO) and equipment delay of LEO constellation satellites. The overall workflow, as illustrated in

Figure 3, consists of the following three main steps:

Step 1: The center-of-mass orbits of LEO satellites and the satellite clock offsets with respect to the onboard GNSS receiver are derived from onboard GNSS observations. These serve as the reference for downlink signal modeling in subsequent steps.

Step 2: A batch least-squares estimation is applied to the downlink observations of LEO satellites to jointly estimate the downlink PCO and equipment delay parameters. Considering the short visible arcs of LEO downlink observations and the limited number of ground stations expected to be available within China in the foreseeable future, GNSS downlink observations are incorporated to assist in the estimation of ground station-related parameters such as receiver clock offset and zenith tropospheric delay (ZTD). This auxiliary information helps to decouple ground station parameters from satellite-specific parameters. In this step, inter-system bias (ISB) between the LEO and GNSS systems must also be estimated to maintain consistency in the joint observation model.

Step 3: Considering the temporal stability of the downlink PCO parameters for LEO satellites, the PCOs estimated in the second step are fixed. The corresponding equipment delays are used as initial values. A bidirectional filtering strategy under static PPP mode is then applied to further refine the equipment delay estimates. Subsequently, the estimation process can be simplified by executing only the first and third steps, allowing for continuous updates of the equipment delay to support long-term operational needs.

3. Simulation Results

Previous studies have demonstrated the feasibility of jointly estimating the downlink signal PCO and equipment delay using observations from single or a small number of LEO satellites. However, there remains a lack of systematic, comprehensive, and statistical evaluation regarding how estimation accuracy is affected by factors such as constellation size, orbital altitude, spatial-temporal error characteristics, and the number of ground stations. Therefore, this section aims to conduct a series of simulation-based experiments to assess the impact of these key factors on estimation performance, providing insights for future system design and deployment. Due to the unavailability of real-world observation data from ground receivers tracking the downlink signals of LEO satellites, simulation-based methods are adopted to generate representative datasets for the following experiments.

3.1. Data Simulation and Parameter Estimation Strategy

3.1.1. Constellation Simulation

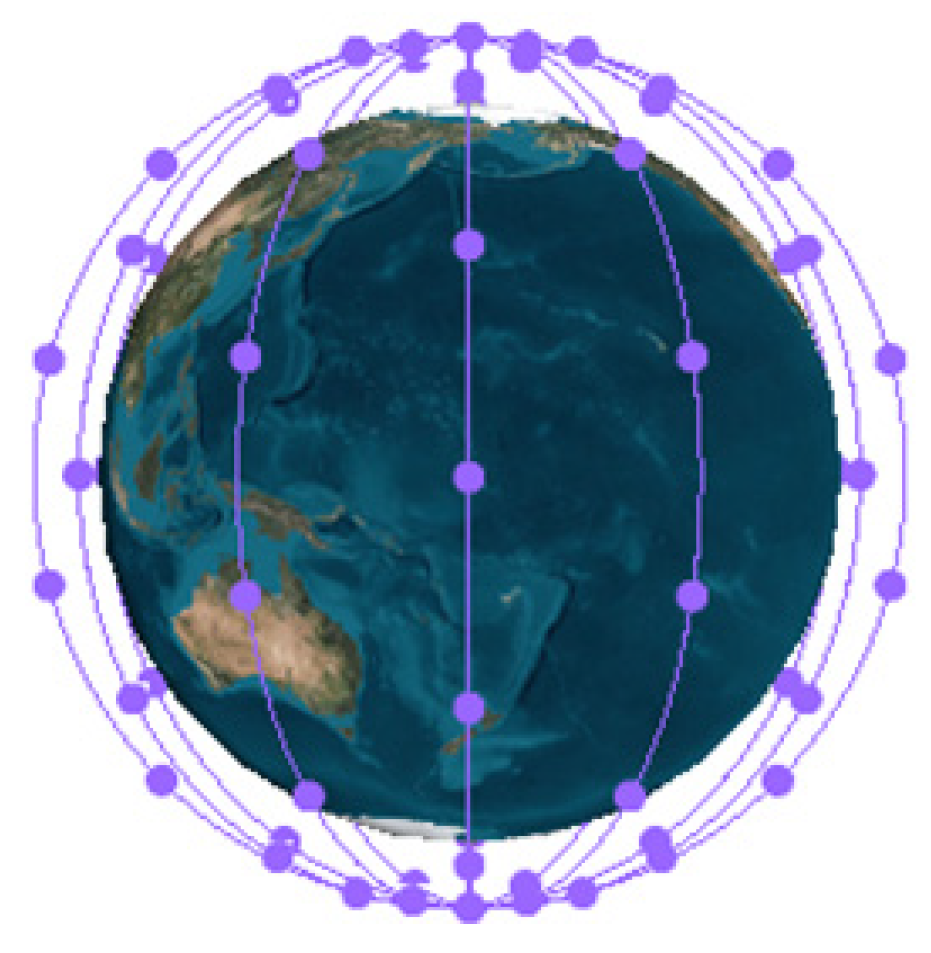

To meet the requirements of the simulation experiments in this study, five polar LEO constellation configurations—labeled as Schemes A, B, C, D, and E were designed. The constellation parameters were inspired by the system architecture proposed in the paper for LEO-based navigation enhancement [

14]. Detailed configuration parameters are listed in

Table 1. These schemes span a range of satellite numbers, orbital altitudes, and distribution patterns, enabling a comprehensive evaluation of how constellation design affects the estimation accuracy of PCO and equipment delay.

Figure 4 illustrates the configuration of the simulated Scheme A LEO constellation. In this simulation, a polar LEO constellation is configured with 144 satellites evenly distributed across 6 orbital planes, with an approximate altitude of 1000 km. The LEO satellites are numbered sequentially as L01, L02, …, L144. For GNSS reference, the BDS-3 (BeiDou-3) constellation is adopted in the joint simulation and evaluation.

To better approximate real-world conditions, this study adopts a realistic error modeling approach for the simulated LEO satellite orbits and clock biases. Orbital errors in LEO satellites are typically characterized by distinct periodic patterns, primarily resulting from imperfections in the dynamic force models, such as atmospheric drag and solar radiation pressure. In contrast, clock errors arise from a combination of systematic periodic variations (e.g., thermal drift or orbit-dependent effects) and stochastic noise introduced by the onboard oscillator. Accordingly, the orbital errors are modeled using deterministic periodic functions (e.g., cosine terms), while the clock errors are represented as a superposition of periodic components and Gaussian white noise [

13]. This composite modeling strategy ensures a more faithful representation of orbit and clock bias behaviors, thereby enhancing the reliability of simulation-based performance evaluations.

Figure 5 illustrates a representative example of the simulated orbit and clock bias errors.

3.1.2. Observation Simulation and Ground Station Distribution

The ambiguities in phase observations linked to distinct receivers and frequencies are simulated as distinct integer ambiguities assigned to each satellite-frequency combination. The equipment delay parameters for LEO satellites are assumed as a constant ranging from tens to hundreds of nanoseconds, which vary with each satellite. In addition, the PCO corrections of GNSS satellites are simulated according to the precise ephemeris.

Based on the aforementioned configuration, the ionosphere-free downlink signal PCO parameters are defined in the satellite-fixed coordinate system, which follows the convention adopted by the GRACE-C satellite with the X-axis pointing along the flight direction, the Z-axis pointing toward the Earth’s center, and the Y-axis completing the right-handed system. Different parameter values are assigned to individual LEO satellites to account for variations in onboard equipment delays.

The tropospheric delay is simulated according to the IGS precise ZTD parameters. The observation noises are set as zero-mean normal distributions with standard deviations of 0.3 m and 3 mm for pseudorange and phase observations, respectively. The other simulation configurations are outlined in

Table 2.

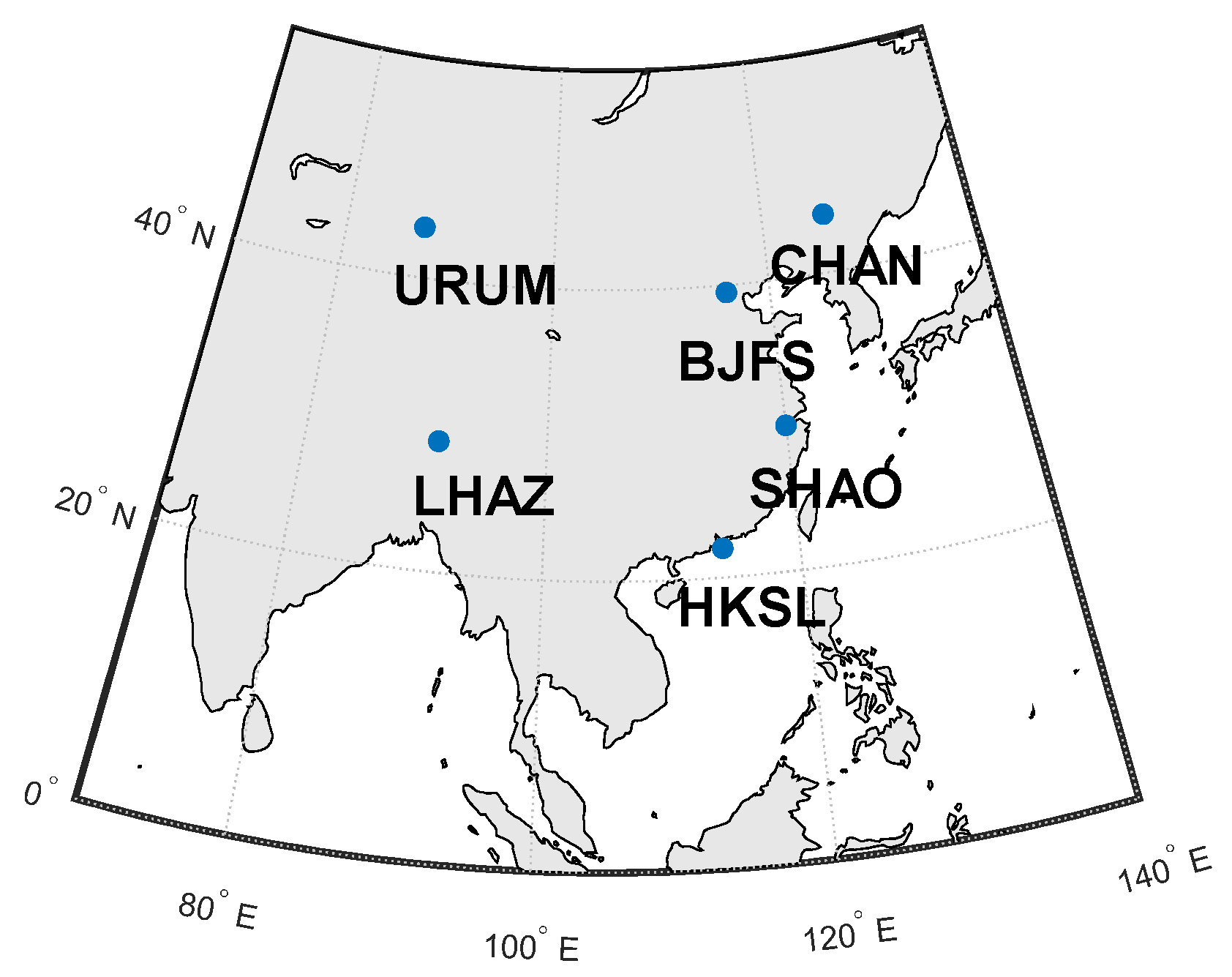

In the initial stages of the development of the LEO satellite navigation system, it is conservatively estimated that the number of ground stations capable of tracking its navigation signals will be severely limited. This requires taking into account the scenario where global station deployment is not feasible and the number of available monitoring stations is scarce. Therefore, six network stations located in China are selected to simulate GPS and LEO observation shown in

Figure 6, which are SHAO, URUM, CHAN, LHAZ, BJFS, and HKSL, respectively.

3.1.3. Experimental Data and Processing Strategy

The configuration of precise ephemeris and observation data used for estimating the LEO downlink antenna phase center offset (PCO) and equipment delay is summarized in

Table 3 and

Table 4. It is important to note that, in order to analyze the impact of different factors on the estimation of LEO downlink PCO and equipment delay, several parameters are provided with multiple configuration options. In addition, considering that a single LEO satellite typically passes over a ground station for only a few to several minutes—much shorter than the multi-hour visibility of GNSS satellites—a high-frequency observation interval of 5 s is adopted to enhance the utilization of observation data and improve the estimation accuracy.

For clarity and brevity, the following abbreviations are used in the tables to represent different types of simulated errors:

P: Periodic error (e.g., “P2 cm” denotes a periodic error with an amplitude of 2 cm)

W: White noise error (e.g., “W1 cm” denotes white noise with a standard deviation of 1 cm)

P + W: Combined periodic and white noise error (e.g., “P2 cm + W1 cm”)

Unless otherwise specified, the baseline scheme is the one highlighted in bold and marked with an asterisk (*) in the table.

The downlink signal PCO and equipment delay are estimated using a least-squares estimation (LSE) method based on combined BDS and LEO downlink observations. the estimated state vector includes the LEO downlink signal IF PCO, the IF equipment delay of the LEO satellite, the IF carrier phase ambiguities for both BDS and LEO satellites, the receiver clock bias, the receiver tropospheric delay, and the station ISB for LEO system (BDS as the reference). The overall estimation strategy is summarized in

Table 5. After obtaining a reliable solution for the LEO antenna PCO, the PCO values are fixed, and estimation of the equipment delay is performed.

3.2. Comparison of Parameter Correlations in Single LEO Satellite and LEO Constellation Modes

Since the correlation between parameters is a key factor affecting estimation accuracy, the parameter correlations in the context of LEO satellites are analyzed in detail. Two estimation modes are considered:

- (1)

Single LEO Satellite Mode: Only the downlink signal PCO and the corresponding equipment delay parameters of a single LEO satellite are estimated [

30].

- (2)

LEO Constellation Mode: The downlink signal PCOs and equipment delays of all LEO satellites within the constellation are jointly estimated in a unified solution.

The correlation characteristics of the estimated parameters under both modes are compared to evaluate the impact of joint estimation across a constellation on parameter separability.

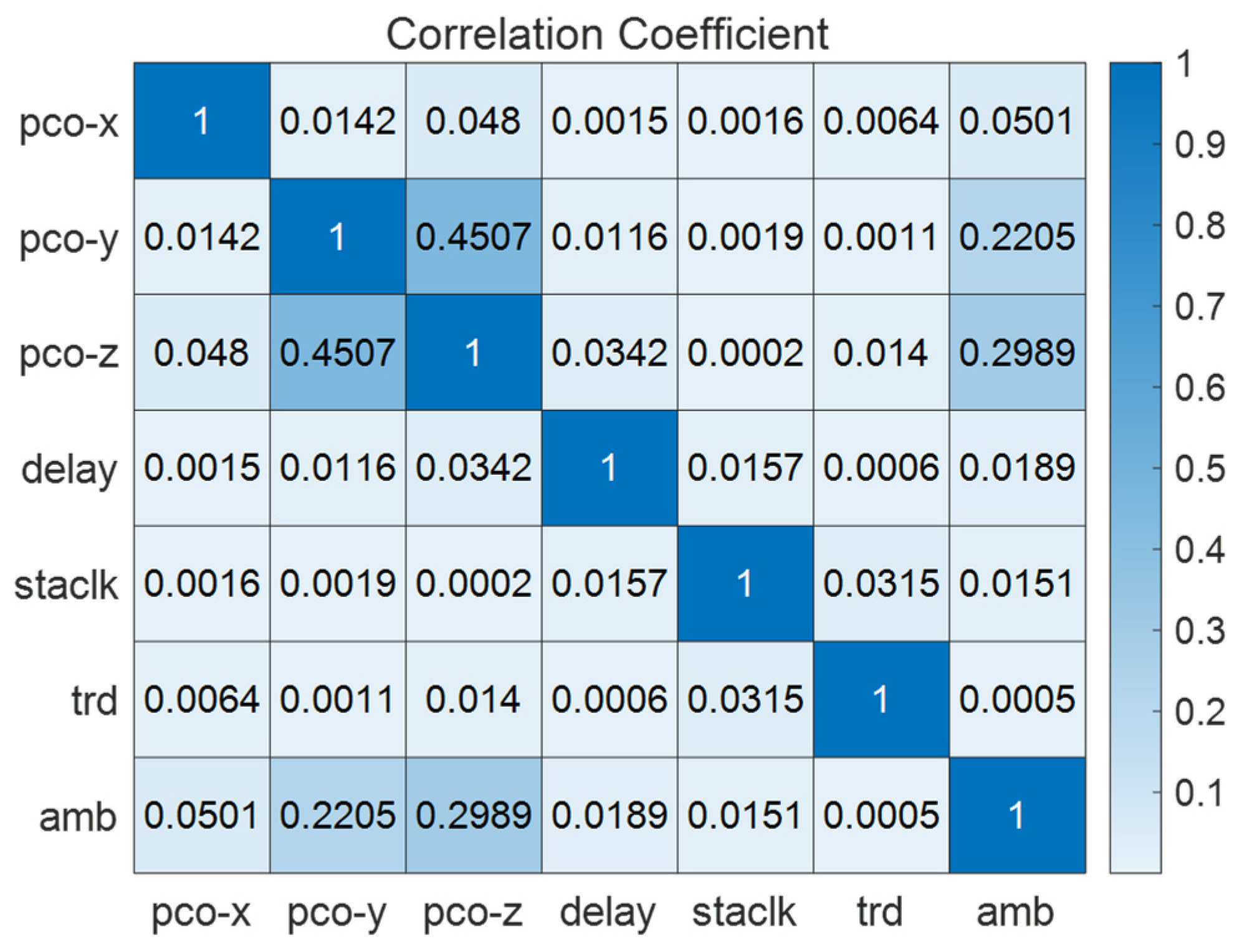

Figure 7 illustrates the mean correlation coefficient matrix of downlink signal PCO parameter, equipment delay parameter, LEO satellite ambiguity parameter, station clock parameter and station tropospheric delay parameters. The mean coefficient that is less than 1% indicates a low correlation between X direction of the downlink signal PCO and with other direction of PCO parameters. The mean correlation coefficients between Y direction and Z direction of the downlink signal PCO is approximately 47%. The mean correlation coefficients are less than 3% between LEO satellite equipment delay and other parameters. The mean correlation coefficients between LEO satellite ambiguity parameter with Y direction, Z direction of the downlink signal PCO parameter are approximately 24% and 33% respectively.

The correlation of estimated parameters in LEO satellite can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

The X direction of the downlink signal PCO and equipment delay parameters are basically independent of other parameters;

- (2)

The Y direction and Z direction of the downlink signal PCO have a strong correlation;

- (3)

LEO satellite ambiguity parameter has a closely correlation with the Y direction and Z direction of the downlink signal PCO parameter.

- (4)

The station estimated parameters are independent of the parameters to be estimated of LEO satellite.

Figure 8 illustrates the mean correlation coefficient matrix for LEO Constellation Mode. The result shows that while the overall correlation structure remains similar in both modes, the mean correlation coefficients are significantly reduced in the constellation mode. This suggests improved parameter separability, making the constellation-based estimation more favorable. Therefore, the LEO constellation mode is adopted in the subsequent analysis throughout this paper.

3.3. Comprehensive Evaluation of Factors Influencing LEO Downlink PCO and Equipment Delay Estimation

The feasibility of estimating LEO downlink signal PCO and equipment delay has been acknowledged. However, systematic, comprehensive, and statistically supported conclusions are still lacking with respect to the influence of key factors such as constellation size, orbital altitude, spatiotemporal accuracy requirements, and the number of ground stations on the estimation performance of these parameters. This section aims to perform a thorough evaluation of these factors to assess their respective impacts on the estimation accuracy, thereby providing valuable insights for the design and deployment of future LEO-based navigation augmentation systems.

To obtain a generalized assessment of the constellation-level estimation performance, statistical analysis is carried out based on the average PCO and equipment delay results across all satellites in the constellation. Simulation-based and statistical evaluations are used to support these findings. Specifically, the accuracy of PCO is assessed as the difference between the estimated value and its known true value from simulation, while the accuracy of the equipment delay is quantified by computing the root mean square (RMS) of the difference between the estimated and true values across all epochs.

3.3.1. Impact of Orbital Altitude on the Estimation Accuracy

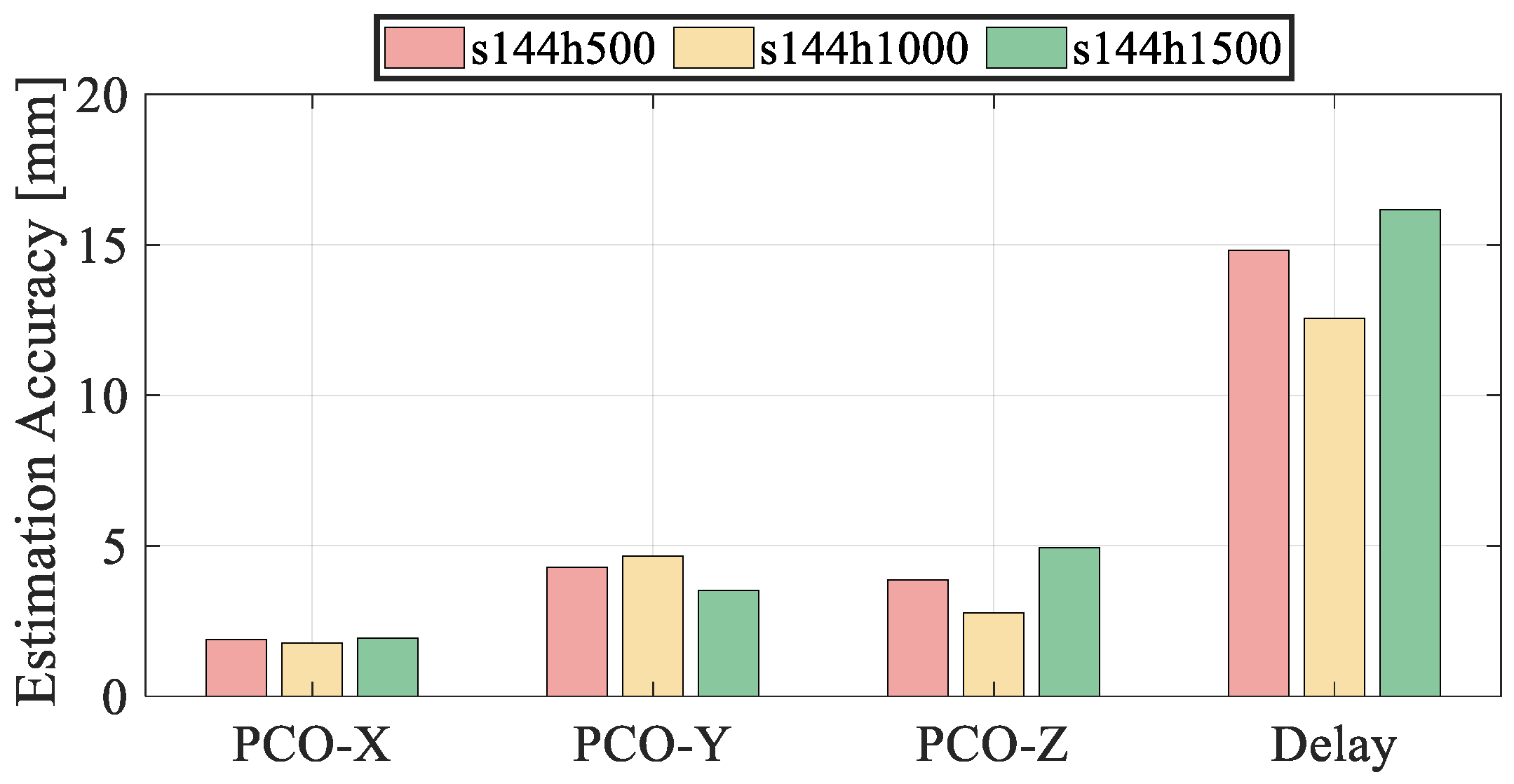

Under a fixed constellation size, the impact of orbital altitude on the estimation accuracy of LEO downlink signal PCO and equipment delay is primarily reflected in two aspects: higher orbital altitudes result in more visible LEO satellites for ground stations, whereas lower altitudes lead to faster relative motion between satellites and the ground, enhancing the geometric variation but reducing the number of visible satellites. To investigate these effects systematically, three representative polar-orbit constellation schemes A, B, and C were selected, with orbital altitudes of 500 km, 1000 km, and 1500 km, respectively, and all containing 144 satellites.

Figure 9 illustrates the estimation accuracy of PCO and equipment delay under LEO constellations with identical scale but different orbital altitudes. The corresponding statistical results are summarized in

Table 6. The results show that the estimation accuracy in the X-direction is consistently higher than that in the Y and Z directions, with values better than 2 mm and relatively insensitive to changes in orbital height. This may be attributed to the alignment of the X-direction with the satellite velocity vector, which leads to faster changes in the corresponding partial derivatives in the design matrix and improves estimation sensitivity. In contrast, the Y and Z directions exhibit greater sensitivity to orbital altitude. At 500 km, the estimation accuracies of Y and Z directions are nearly equal; at 1000 km, the Y-direction performs worse than Z; while at 1500 km, the Z-direction accuracy deteriorates significantly. Regarding equipment delay, the best estimation accuracy is achieved at 1000 km, followed by 500 km, with the poorest performance at 1500 km. Nevertheless, all three configurations maintain equipment delay accuracy within 2 cm. Overall, these results confirm that orbital altitude has a significant impact on the estimation accuracy of LEO downlink PCO and equipment delay, through its influence on satellite visibility and geometric variation. Therefore, both factors should be carefully considered in constellation design and system implementation to optimize estimation performance.

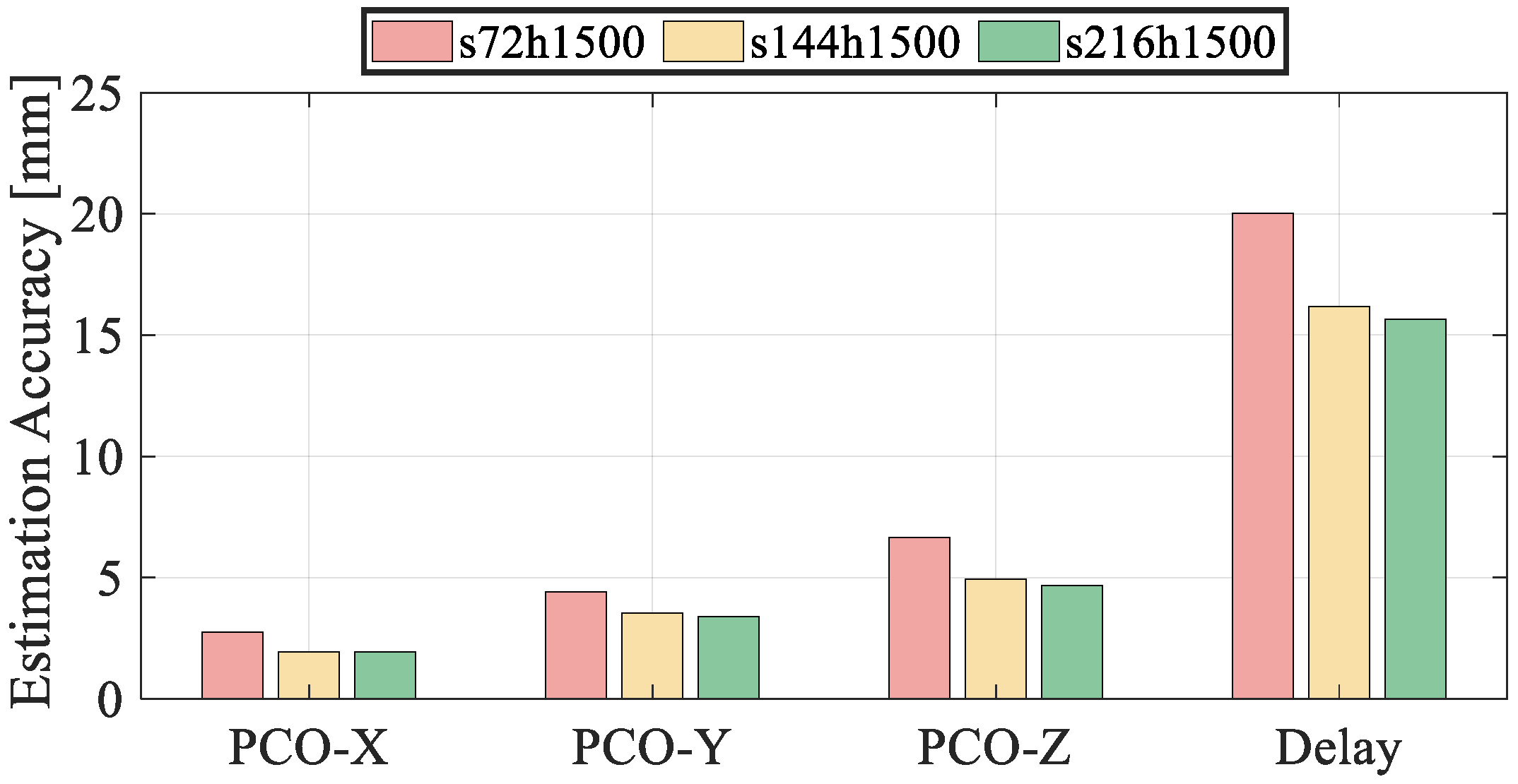

3.3.2. Impact of Constellation Scale on the Estimation Accuracy

To investigate the influence of constellation scale on the estimation accuracy of downlink signal PCO and equipment delay, three polar-orbit LEO constellation schemes C, D, and E were selected, consisting of 72, 144, and 216 satellites respectively. All constellations share the same configuration of 12 orbital planes and an altitude of 1500 km. The 72-satellite constellation can be extended to 144 or 216 satellites by progressively densifying the number of satellites per orbit.

Figure 10 illustrates the estimation accuracy of PCO and equipment delay under different constellation scales, with detailed statistics provided in

Table 7. As shown in

Table 7, increasing the number of satellites in the constellation improves the estimation accuracy of both PCO and equipment delay. The X component of LEO downlink signal PCO remains relatively stable across configurations, consistently better than 3 mm. In contrast, the Y and Z directions show more substantial improvement—from 4.41 mm and 6.64 mm in the 72-satellite scheme to 3.40 mm and 4.68 mm in the 216-satellite configuration. Similarly, the equipment delay estimation improves from 20.01 mm to 15.65 mm as the satellite number increases. These results demonstrate that, under consistent orbital geometry, increasing the constellation scale enhances the observation redundancy and overall geometric strength, thereby improving the observability and estimation precision of key parameters.

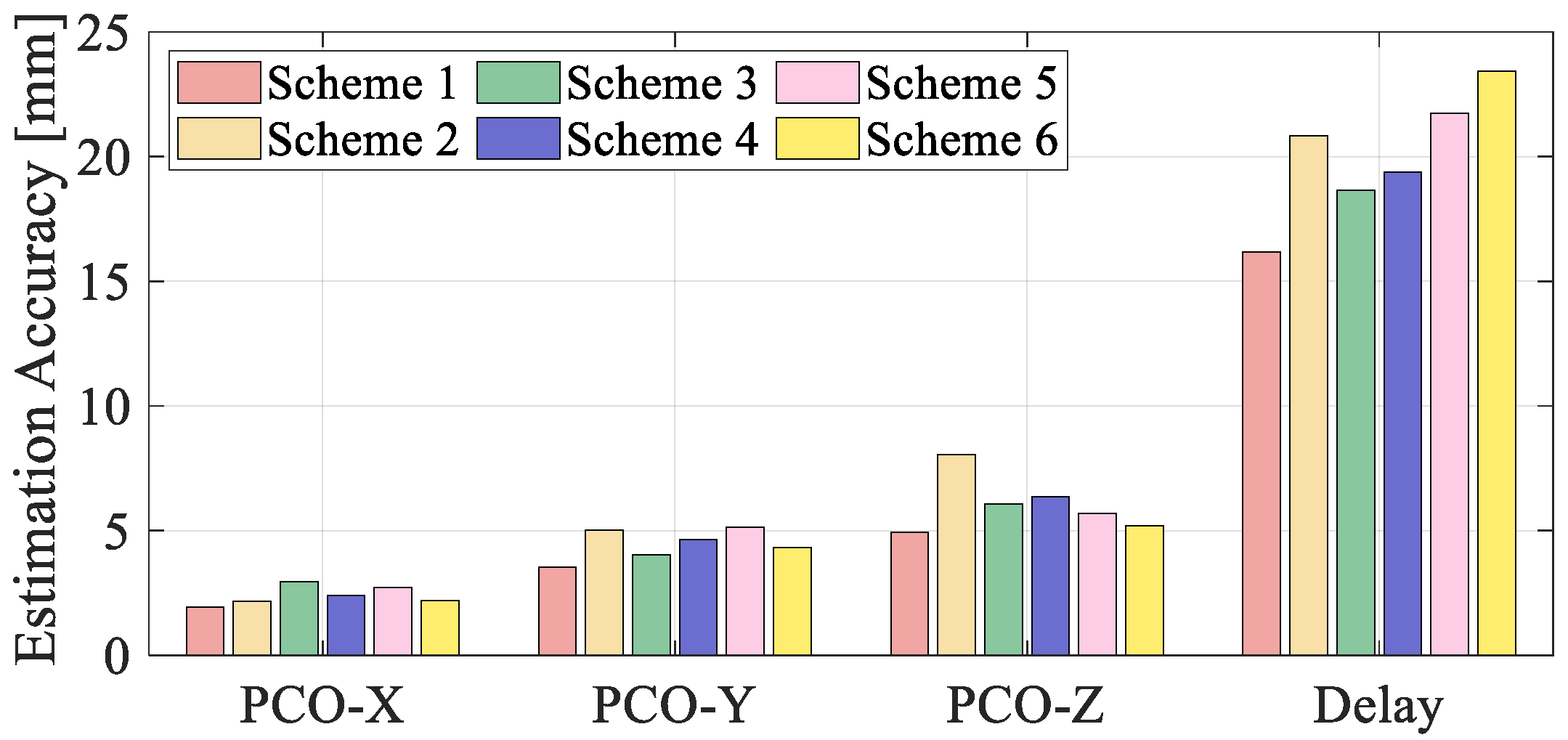

3.3.3. Impact of Orbit and Clock Bias Errors on the Estimation Accuracy

In practical precise orbit determination and satellite clock bias estimation, the results are inevitably affected by residual errors. Unmodeled orbit and clock errors in LEO satellites may be absorbed by estimable parameters such as the downlink antenna phase center offset (PCO) and equipment delay, thereby degrading the overall estimation accuracy. Therefore, the precision of orbit and clock products plays a critical role in the reliable estimation of downlink parameters. This section investigates the impact of orbit and clock errors on the estimation accuracy of PCO and equipment delay by simulating five combinations of error configurations.

Figure 11 illustrates the estimation results under different error settings, with detailed statistics provided in

Table 8.

A comparative analysis of all test schemes demonstrates that both orbit and clock errors significantly affect the estimation accuracy of LEO downlink parameters. Among the three components, the Z direction of the PCO is the most sensitive, with its estimation error increasing from 4.94 mm in Scheme 1 to 8.06 mm in Scheme 2 and 6.36 mm in Scheme 4 when periodic errors are introduced in the radial (R) and normal (N) orbit directions, respectively. The equipment delay estimation is also notably degraded, reaching 23.73 mm under intensified white noise conditions (Scheme 6), representing an increase of approximately 47% compared to the best-case configuration. A comparison among Scheme 1,2 and Scheme 3, and 4 reveals that periodic errors in the R direction exert a more pronounced impact on estimation performance than those in the T or N directions. The contrast between Scheme 1, Scheme 5 and Scheme 6 further indicates that periodic errors in clock bias mainly degrade PCO estimation, while white noise errors predominantly affect the accuracy of equipment delay estimation. Additionally, the X component consistently exhibits the highest estimation accuracy across all schemes, indicating that its geometric sensitivity to orbit and clock errors is relatively low. In conclusion, achieving high-precision orbit and clock products is essential for improving the estimation accuracy of downlink antenna PCO and equipment delay.

3.3.4. Impact of Ground Station Number and Processing Duration on Estimation Accuracy

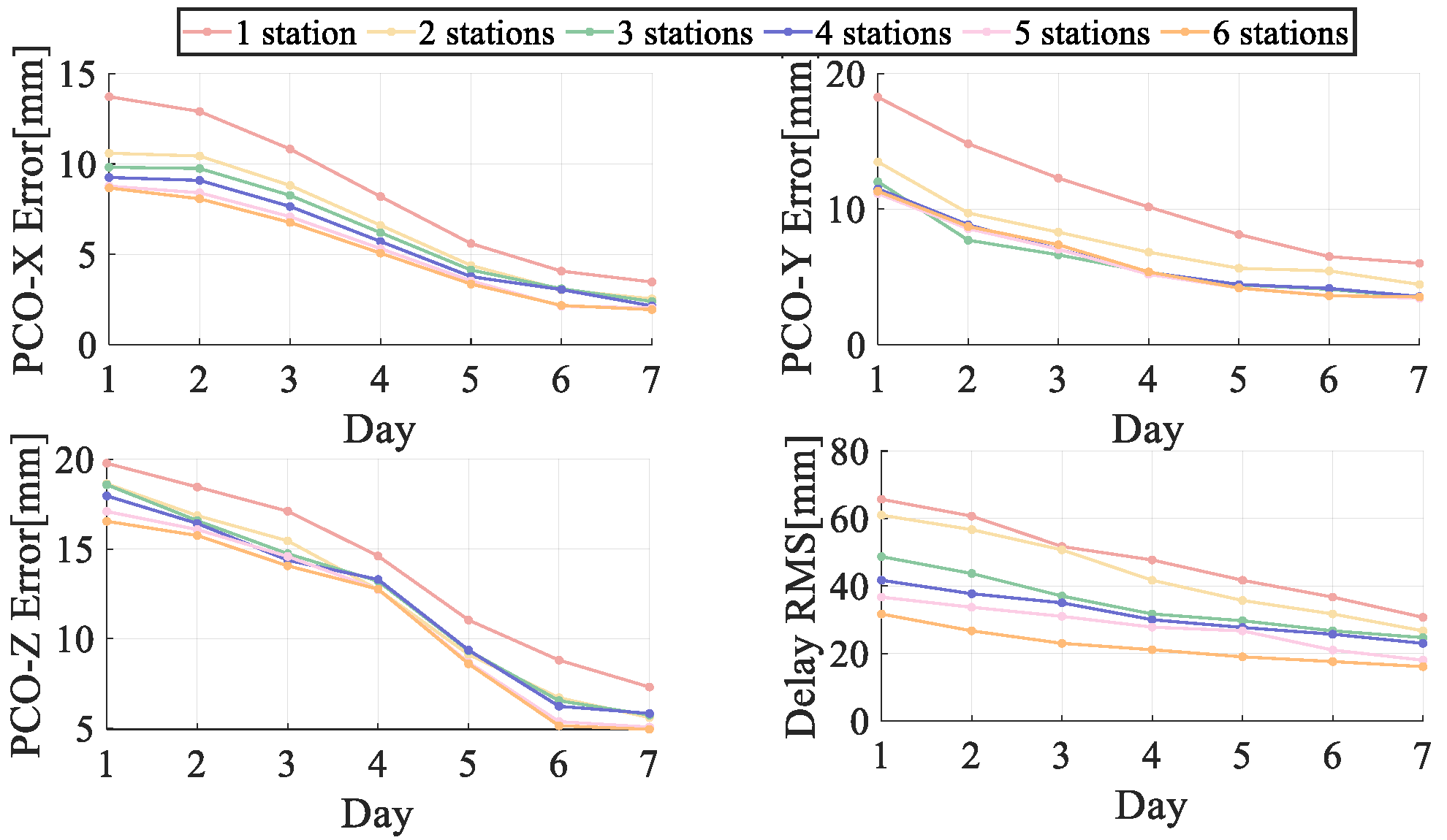

To investigate the influence of ground station quantity and data processing duration on the estimation accuracy of downlink signal phase center offset (PCO) and equipment delay, a series of simulation experiments were designed with varying combinations of tracking stations and processing durations.

Figure 12 illustrates the variation trends of estimation biases for the three PCO components and equipment delay under different numbers of stations (1–6) and processing durations (1–7 days).

Table 9 and

Table 10 respectively summarize the results for fixed 7-day processing with varying station numbers, and for fixed three-station configurations with varying durations.

The results show that even with only one ground station, the 7-day processing configuration yields sub-centimeter estimation accuracy for PCO, demonstrating acceptable feasibility. Moreover, when the processing duration is held constant, increasing the number of ground stations leads to noticeable improvements in estimation performance. For instance, as shown in

Table 9, increasing the station number from 1 to 3 reduces the X direction bias from 3.47 mm to 2.40 mm and the equipment delay bias from 30.71 mm to 24.89 mm. Further increases up to 6 stations continue to improve the estimates but with diminishing returns, indicating that 3–4 stations are sufficient to provide stable geometric coverage, while additional stations offer marginal improvements.

When the number of stations is fixed at three, extending the processing duration significantly enhances estimation accuracy, as shown in

Table 10. From day 1 to day 7, estimation biases for all PCO components and equipment delay steadily decrease. During the first three days, the Y-direction PCO shows the most rapid improvement, while the X and Z directions exhibit more substantial gains from days 3 to 7, particularly the Z direction, whose bias decreases from 18.59 mm to 5.74 mm. The equipment delay estimate improves considerably within the first four days, with subsequent improvements tapering off, indicating that while longer observation periods improve observability, the marginal benefit diminishes beyond a certain point.

In summary, increasing the number of ground stations (preferably 3–4) and extending the processing time (ideally 5–7 days) can significantly improve the estimation accuracy of downlink PCO and equipment delay. The Z direction of PCO and equipment delay are particularly sensitive to these factors.

3.4. Discussion

The simulation results demonstrate that the proposed joint estimation framework can achieve sub-centimeter accuracy for PCO and centimeter-level accuracy for equipment delays, even with only 3–4 regionally distributed ground stations. Compared with previous studies [

18,

30], which mainly relied on single or a few experimental satellites under static scenarios, this work extends the evaluation to constellation-scale conditions, systematically analyzing the impacts of orbital altitude, constellation size, orbit/clock bias errors, and ground station configurations. These results highlight the practical applicability of the method for large-scale LEO navigation constellations.

A key finding is that the X-direction PCO component is consistently the most stable across different scenarios, while the Y- and Z-directions are more sensitive to orbital and clock errors. This observation aligns with the geometric characteristics of LEO orbits but also reveals new insights into parameter separability at the constellation level. Another important observation is the diminishing returns as constellation size increases: while additional satellites improve estimation accuracy, the marginal benefits decrease beyond a certain constellation scale. Similarly, increasing the number of ground stations improves parameter observability, but 3–4 well-distributed stations are generally sufficient to ensure robust performance.

Despite these encouraging results, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the simulations are based on idealized assumptions of data availability and error modeling. In real-world scenarios, factors such as thermal deformation, structural instability, and long-term hardware drifts could impact PCO and equipment delay behavior. Second, the simplified modeling of orbit and clock errors may underestimate their influence on parameter estimation.

Future research should focus on validating the proposed framework using real LEO downlink observations. Additionally, integrating multi-frequency GNSS observations, assessing the long-term stability of LEO equipment delays, and developing real-time implementation strategies will be crucial to advancing the operational deployment of LEO-augmented navigation systems.