Abstract

Schedule risks are the main threat for high efficiency of schedule management in power grid engineering projects (PGEP). This paper aims to build a systematical framework for schedule risk management, which consists of three dimensions, including the personnel dimension, method dimension and time dimension, namely supervisory personnel, management methods and the construction process, respectively. Responsibilities of staff with varied functions are discussed in the supervisory personnel part, and six stages and their corresponding 40 key works are ensured as the time dimension. Risk identification, analysis, evaluation and prevention together formed the method dimension. Based on this framework, 222 schedule risks occur in the whole process of PGEPs are identified via questionnaires and expert interviews. Then, the relationship among each risk is figured out based on the Interpretative Structure Model (ISM) method and the impact of each risk is quantitatively assessed by establishing evaluation system. The actual practice of the proposed framework is verified through the analysis of the first stage of a PGEP. Finally, the results show that this framework of schedule risk management is meaningful for improving the efficiency of project management. It provides managers with a clearer procedure with which to conduct risk management, helps them to timely detect risks and prevent risks from occurring. It is also easy for managers to judge the influence level of each risk, so they can take actions based on the level of each risk’s severity. Overall, it is beneficial for power grid enterprises to achieve a sustainable management.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

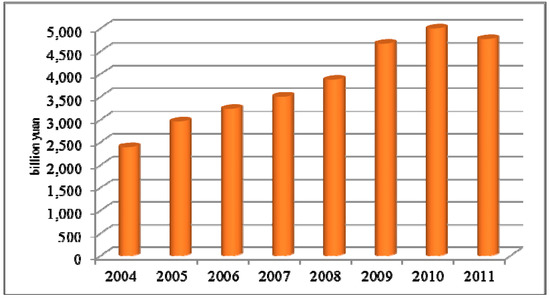

As a result of macro-economic controls, the growth rate of national power demand keeps growing in China [1]. From Figure 1, the annual production capacity of electricity went up to over 45,000 kWh in 2011, nearly three times of that in 2002. The growth rate of electricity production in each year kept positive as well. It is forecasted that the total electricity consumption will grow at an annual growth rate of 7.8% during the “12th Five-Year Plan” period (2011–2015), which will be more than 6 × 1012 kWh in 2015. In addition, the annual growing rate will be 6.1% during the “13th Five-Year Plan” period, and the total figure will reach nearly 8.2 × 1012 kWh in 2020 [2]. From Figure 2, the amount of fixed asset investment in electricity and heat production and supply industry achieved RMB 4762 billion Yuan in 2011, at an annual average growth rate of 14.2% in the past 7 years.

Figure 1.

Annual electricity production in China. Source: National Bureau of Statistics.

Figure 2.

Annual fixed asset investment in electricity and heat production and supply industry. Source: National Bureau of Statistics.

Accordingly, the amounts of power grid engineering projects (PGEPs) will be expanded. Different from general projects, PGEPs are endowed with many characteristics, such as high cost, complex technology, masses of departments involved, tight schedule requirements, long construction cycle, complex construction environment and other factors. All these determine that the construction process of a PGEP is subject to a number of unstable factors, which leads to easy occurring of risks. Schedule risks are identified as risks whose appearance would lead to the extension of project’s lifecycle. Except for project duration’s expanding, this kind of risk also causes a substantial increase of project costs, plan changes, reduction of the effectiveness and efficiency of corporate management and so on.

Nowadays, the electricity grid market is mainly occupied by two companies in China, namely the State Grid Corporation and China Southern Power Grid Corporation. The provinces and regions supervised by these two enterprises are shown in Figure 3. Though the Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system, a highly integrated system, covering business, projects and plans, is comprehensively applied in these two power grid companies, information related to schedule risk management is not covered. Therefore, if there were no systematical schedule risk management framework considering organizational structure, construction phase and workflow for these two companies, they would easily suffer losses caused by schedule risks. As a result, it is essential to concentrate on a variety of schedule risks during a PGEP’s construction process.

This paper aims to build a systematic schedule risk management framework for PGEPs’ sustainability. A literature review is conducted in the latter part of Section 1. The framework is put forward and discussed in Section 2, which is a three-dimensional framework based on three aspects, including management personnel, construction process and management practices. Further, the paper shows the operation process of the proposed framework and deeply analyzes the schedule risk throughout the construction process in Section 3. With specific case study in feasibility study stage, the first stage of PGEP construction, the paper verifies the feasibility of the established framework. Ultimately, Section 4 concludes this paper.

Figure 3.

Provinces and regions covered by two power enterprises in China.

1.2. Literature Review

Project Risk Management (RM) was not an essential component of project management until the end of the 1970s [3]. For risk management process, a large number of researchers have proposed various views. Chapman [4] presented Project Risk Analysis and Management (PRAM) model, which covered the key elements of project management and established procedures and methods of analysis for the project’s risks in a progressive way. The Institute of Risk Management [5] defined the Risk Management System (RMS), and described the formation of risks and risk levels and divided risk management system into five parts, including risk source, risk factors, risk assessment, risk control and post-evaluation. The Project Management Institute [6] proposed the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBoK), which summarized the process of risk management as containing six steps, namely risk management plan, risk identification, qualitative risk assessment, quantitative risk estimate, risk response plans and risk control. In general, effective risk management involves a four-phase process, constituting risk identification, risk analysis, risk evaluation and risk response.

The number of risks inherent in the power grid project is extremely large, so risk identification needs risk classification first. Some methods for classification have been suggested in previous studies. For examples, some researchers focused on the risk origin [7,8] and some concentrated on the hierarchical relationship among risks [9,10].

For risk analysis, different scholars have focused on diverse analytical goals. Liu [11] analyzed non-additive effects under the influence of multiple risks and put attention to the correlation between various risks [12]. In addition, some other researchers focused on the link relationship between risks [13,14,15]. Moreover, a wide range of methods could be used to effectively carry out risk analysis, such as Fault Tree Analysis, Sensitivity Analysis, Estimation of System Reliability and Effect Analysis [16], Fuzzy Set [13,17], Bayesian networks [18,19] and others.

Various approaches have been adopted for assessing project risks. At first, many scholars carried out statistical methods to deal with the schedule risk and gradually, many concluded that human factors, professional experience and personal judgment were essential for risk evaluation [20]. Moreover, the indicators used to evaluate the risks can be summarized as predictability, exposure, manageability and controllability in the previous literature [21,22,23,24], and risk cost has been used as an important risk impact measurement as well [25,26,27]. In addition, diversified models could be utilized for risk assessment. It is evident that AHP, developed by Thomas Saaty [28], has received a worldwide recognition. It is an effective and systematical method for assessing impact of risks and allocating impact weight and many researchers have verified it [29,30,31]. Besides, Monte Carlo simulation [32], Entropy Weight, TOPSIS model [33,34] and other methods have been widespread employed as well.

Amongst the exiting research, some focus on project schedule management, and some put emphasis on risk management [20,35,36,37,38]. However, researchers seldom concentrate on PGEPs, schedule management and risk management together. In addition, the current risk management of engineering projects presents scattered feature in China, which means managers seldom consider risk control from an integrated view. For example, managers always concentrate on the significant risks, while leave out those which own low frequency or little impact; it is common to trace the risk responsibility after accident occurring instead of beforehand. Under these circumstances, managerial deviations and omits easily happen, which contribute to extraordinary losses. Therefore, it is indispensable to carry out comprehensive identification, adequate analysis and thorough prevention of schedule risks.

2. The Framework of Schedule Risk Management

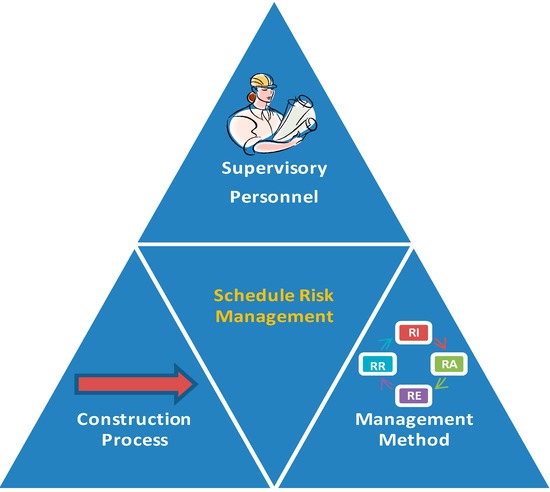

In order to make schedule risk management more comprehensive, a three-dimensional framework is established. This framework considers three important factors in PGEPs, namely people, time and management methods, which are supervisory personnel, construction stages and risk managing methods respectively (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Schedule risk management framework.

In the State Grid Corporation and China Southern Power Grid Corporation, the organizational structure is composed of headquarter, the provincial and the city level subsidiary companies. The PGEPs have to be centralized and approved by the headquarters every year, then decentralized to the provincial companies. Eventually the city level subsidiaries are responsible for implementation. Personnel in these two companies work as proprietors, besides, designers, contractors and supervisors are very important in PEGPs as well. More details are discussed in Section 2.1.

In accordance with the general way of division in project management, the construction process contains six stages, namely Feasibility study stage, Preliminary design stage, Construction preparation stage, Construction stage, Completion and acceptance stage and Appraised stage. Further, every stage comprises several key works, which are fully discussed in Section 2.2.

A risk management cycle is normally divided into four parts, namely risk identification (RI), risk analysis (RA), risk evaluation (RE) and risk response (RR). Relevant details are discussed in Section 2.3.

As shown in Figure 5, every manager needs to carefully identify, analyze and prevent the potential risks at every stage and every work during the construction process. The content of the risks in this framework keeps updating after every PGEP, and this frame works as a guide book for every manager, which helps them to judge the impact of every risk, prevent risks and control risks. Therefore, a coherent risk managing framework has been formed.

Figure 5.

Practical application of schedule risk management framework.

2.1. Supervisory Personnel

Generally, the participants of a PGEP conclude proprietors, designers, contractors and supervisors. The power companies play the role of proprietors, whose risk responsibility covers the whole process from project approval to post-project evaluation. The designer’s responsibility mainly manifests in understanding the use of new materials and new techniques, providing reasonable technical solutions and complete design documents, and being ability to fulfill contractual obligations. The main shows of contractors’ responsibility are providing rational preparation of production plans and construction programs, being suitable project managers and technical experts, being well aware of safety awareness, and successfully following construction specification requirements. Main shows of supervisors include providing well reports about contractor’s illegal activities, having qualified ability and a good control of practical experience and providing sufficient professional support.

2.2. Construction Process

This paper divides construction process of PGEPs into 6 stages as stated above. Further, every stage is comprised of several key works, which are the milestones in the schedule management. The delay of these works will bring negative impacts on follow-up works and eventually expand the total time limit of the project. 40 key works are determined through visiting 12 experts of project management and are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Grid project construction phase and the corresponding working nodes.

| Stage | Key works | Stage | Key works |

|---|---|---|---|

| A Feasibility study stage | W1 Preparation of project proposals W2 Project feasibility study W3 Preparation of project feasibility study report W4 Project feasibility assessment W5 Project Approval W6 Feasibility study approved | B Preliminary design stage | W7 Design tender W8 Construction units commissioned W9 Establishment of owner project department W10 Completion of pre-planning documents W11 Preliminary Design W12 Review of preliminary Design |

| C Construction preparation stage | W13 Issued annual plan W14 Material and non-material bidding W15 Contact signed W16 Approval of preliminary design W17 Funds demand planning and disbursement W18 Completion of construction permits W19 Construction drawing design W20 Review of construction drawings and design handover W21 Land expropriation W22 Connected waterways, circuits, roads and other | D Constructionstage | W23 Starting Report application W24 Start W25 Safety and quality supervision of the production process W26 Project meetings W27 Construction (foundation construction) W28 Foundation construction acceptance and handover W29 Process Conversion W30 Installation project W31 System Debug W32 Supervision Acceptance |

| E Completion and acceptance stage | W33 Completion of the project pre-acceptance W34 Debugging and test running W35 Project data compilation and archiving | F Appraised stage | W36 Financial completion of settlement W37 Financial completion of final accounts W38 Standard production acceptance W39 Project Auditing W40 Project appraised |

Where, Wi is the number of key works, i = 1, 2, 3, …, 40.

2.3. Management Method

2.3.1. Risk Identification

Schedule risk identification is to identify and categorize various risks that would affect the schedule plan of projects and then document these risks. Generally, the outcome of risk identification is a list of risks (Appendix Table A1). Risk source identification is an important part of risk identification, which includes risk property identification and risk responsibility identification.

2.3.1.1. Risk Property Identification

In this paper, risk property can be roughly divided into eight kinds, including natural risk (NR), economic risk (ER), financial risk (FR), social risk (SR), management risk (MR), technical risk (TR), policy-legal risk (PLR) and environmental risk (EnR).

Natural risks are those caused by change of climate, geology, environment and other factors. It mainly includes earthquakes, typhoons, geological disasters and other force majeure as well as storms, floods, snow and other severe weather conditions.

Economic risks are those arise from project external economic environmental changes or internal economic relation changes, such as market forecast errors, changes in state investment, changes in debit and credit policies, financing difficulties, cash flow difficulties, interest rate fluctuations, currency fluctuations, inflation, an unreasonable economic structure and others.

Social risks are those caused by the social instability or differences of social culture and habits, such as risks of theft and people’s conflict.

Financial risks are those caused by the deficiency of fund or the excessiveness of financing cost, which will lead to the financing delay and project interrupt.

Management risks are those arise from failures of planning, organization, coordination, control or other management works, such as personnel risks, sub-contracting risks, data transfer risks and contract risks.

Technical risks are those generated by changes due to technology’s advancement, reliability, applicability and availability, which may lead to a lower utilization of production capacity, an increased operational cost and a failure of the quality expectations, such as geological exploration risks, design risks and construction technology risks.

Policy-legal risks are those caused by major changes in political and economic conditions or in government policies, which will lead to a failure of achieving project’s target.

Environmental risks are those brought by changes in social conditions and environmental factors surrounding the project, which will lead to a project’s delay or stop.

2.3.1.2. Risk Responsibility Identification

Risk responsibility identification is mainly used to identify the personnel who should bear the risk if an accident occurred. Generally, there are four responsible parties sharing losses from risks, including proprietors, designers, contractors and supervisors as stated above.

2.3.2. Risk Analysis

Risk analysis is a part of the risk management process for each project, which further identifies potential issues and negative impacts based on the data of risk identification. In a PGEP, it is obvious that the appearance of one kind of risk will often change the occurrence probability of other one or more risks. From this angle, risk analysis aims to analyze the relationship of schedule risks in PGEPs and establish a schedule risk hierarchy diagram based on ISM (Interpretative Structure Modeling) Method. ISM method is an analytical method widely used in the modern system engineering, which could decompose a complex system into several subsystem elements and ultimately form a multi-level hierarchical structure based on practical experience and computers. It is especially suitable for analyzing numerous variables and a complex relationship. Detailed process is discussed in Section 3.2.

2.3.3. Risk Evaluation

Risk evaluation is concerned with assessing the risk impact quantitatively according to the consequences of risk occurrence. It comprehensively considers the probability of occurrence and extent of losses of every risk based on the risk identification and risk analysis. To conduct a risk evaluation always need to build an evaluation index system and apply scientific methods, ultimately obtain the evaluation results. The detailed evaluation process is shown in Section 3.3.

2.3.4. Risk Prevention

Risk identification, risk analysis and risk assessment are important transitions to carry out more appropriate risk prevention measures. Risk prevention is an extremely significant aspect of risk management, and also a crucial part of achieving the full control of the progress. To effectively conduct a risk prevention, one always has to form a list of prevention measures, which helps managers to prevent risks in advance and control negative impacts when risks occur in time.

3. Actual Practice of Schedule Risk Management Framework

The framework of schedule risk management is composed of 3 parts, namely supervisory personnel, construction process and management method. This section shows the relationship among these three parts and gives an instruction for managers about how to operate according to the framework. To be more clear and logical, this section will conduct the analysis following the order of risk management process.

3.1. Risk Identification

By questionnaires and interviews, whose respondents include project managers, supervisors, designers and construction personnel, we have identified a total of 222 risks, which occur in the whole process of PGEPs. These risks are also sourced from a wide range of literatures including journal articles and books [39,40,41,42]. The quantity of risks in each stage and each work are counted (Figure 6) and the specific content of every risk is displayed in the Appendix Table A1.

Based on Section 2.3.1, 222 risks and their corresponding attributes are confirmed (Table 2, an example of Feasibility Study Stage).

3.2. Risk Analysis

3.2.1. Classification of Risk Category

R is a PGEP schedule risk set. Ri is the type of a risk, R = (R1, R2,…, R8), R1 is nature risk, R2 is economic risk, R3 is social risk, R4 is financial risk, R5 is policy-legal risk, R6 is technical risk, R7 is management risk, R8 is environment risk.

Based on the relevant experts’ views within the industry, the mutual influence among risks is analyzed and the relationship matrix is obtained. In this paper, there is only negative influence of a risk occurring. When a risk happens, it will only increase the probability of subsequent risks, instead of preventing them.

Figure 6.

The number of risks of every key work node in each stage.

Table 2.

Identification of risks and risk sources in Feasibility Study Stage.

| Key Work | Risk | Serial Number | Risk Category | Responsible Party |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | Infeasible economic and technical indicators | r1 | TR | P(proprietor) |

| Uncertain trends of objective things and forecast deviation | r2 | TR | P | |

| Mistakes existed in preparation of project proposals | r3 | TR | P | |

| Project content is inconsistent with the actual | r4 | TR | P | |

| W2 | Preliminary geological exploration is blocked | r5 | SR | P |

| Missing or delay in obtaining of relevant departments’ professional assessment report, reviewing comments and relevant agreements | r6 | MR | P | |

| Changes of national policy, company operating conditions and other conditions | r7 | PLR | P | |

| Incorrect or imperfect project proposal, conflicts against the organization’s strategic | r8 | TR | P | |

| W3 | Survey data and information is not complete, untrue or incorrect | r9 | TR | P |

| Infrastructure sites and the path information is not detailed, project site and planning, engineering geology is wrong. | r10 | TR | P | |

| Power planning changes | r11 | ER | P | |

| W4 | Project evaluation and audit is incorrect | r12 | MR | P |

| Experts or consultants are assessed unqualified | r13 | MR | P | |

| W5 | Project approval application report prepared is imperfect, and not timely submitted to the National Development and Reform Commission(NDRC) | r14 | TR | P |

| Planning advice, land pretrial opinion and other approved data are incomplete | r15 | TR | P | |

| Projects are not approved or delay | r16 | MR | P | |

| Comments of provincial feasibility review are missing or delayed | r17 | MR | P | |

| W6 | Deviation of feasibility size and scale approved is too large | r18 | TR | P |

| Documents of approved feasibility study of State Grid Corporation and other documents are not issued or delay | r19 | MR | P |

3.2.2. Judgment of Risk Relevance

In the relationship matrix, relationship value is in accordance with

Then the Boolean matrix of the various risk factors Ri is confirmed (Table 3).

Table 3.

Grid project schedule risk relationship matrix.

| Rj | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | R7 | R8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ri | |||||||||

| R1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| R2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| R3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| R4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| R5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| R6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| R7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| R8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

3.2.3. Establishment of Reachability Matrix

Reachability matrix

Then the reachability matrix is obtained as

3.2.4. Domain Decomposition

In the reachability matrix, reachability set Equation (1) can be divided according to different locations of each element in the system.

where, is the reachability set, which means all the element sets that can be reached from the element Ri; D(Ri) is the forward set, which means all the element sets that can arrive at element Ri; T(Ri) is the common set, which meets the requirements of formula (2).

Then, the domain decomposition can be conducted according to formula (2) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of domain decomposition.

| i | L(Ri) | D(Ri) | L(Ri)∩D(Ri) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,3,6,7,8 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2,3,4,7,8 | 2,4,5 | 2,4 |

| 3 | 3,7,8 | 1,2,3,4,5,6 | 3 |

| 4 | 2,3,4,7,8 | 2,4,5 | 2,4 |

| 5 | 2,3,4,5,6,7,8 | 5 | 5 |

| 6 | 3,6,7,8 | 1,5,6 | 6 |

| 7 | 7,8 | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 | 7,8 |

| 8 | 7,8 | 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 | 7,8 |

Therefore, R1 and R5 are in the same domain. Then all the elements can be deduced in the same domain similarly.

3.2.5. Classification of Elements in the Same Domain

When the intersection of reachability set and forward set is equal to reachability set; the most superior unit can be obtained. That is to say; the elements which could not reach other elements in the system are called as the first-level elements.

where, is the number of levels, is the complete set.

According to the decomposition results, schedule risks can be divided into four levels. From the top to the bottom in turn is

- ;

- ;

- ;

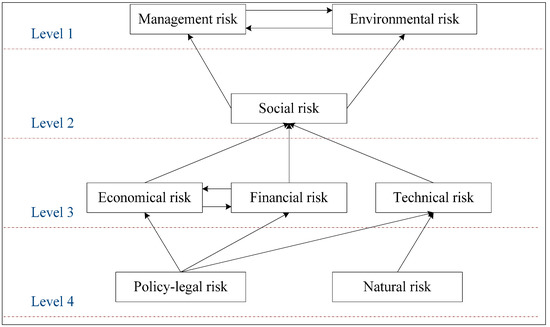

As a result, the multilevel structure of PGEP schedule risks is established (Figure 7).

From Figure 6, both policy-legal risk and natural risk are at the bottom place, whose occurrence would produce a domino effect and be the potential driving force for other risks. It is not difficult to understand that these kinds of risks are always external, and are not controlled by project managers. For example, the government issues a new national policy, by which it may change the external financing conditions, material prices, technology used in the project and other conditions. Via theses occurrences, economic risk, financial risk and technical risk would take place. Besides, sometimes a region may be devastated by an earthquake or other natural disasters. In this case, all the manpower, materials and other resources must have to be put into the reconstruction and PGEP construction would naturally be terminated. On the other hand, management risk and environment risk are at the top of the structure, which means they are vulnerable to the impact of other risks. These two risks are closely related to a project itself, one that is caused by non-standard behaviors of project managers and the other generally occurs in the complex environment of the construction site. Moreover, there is an interaction between economic risk and financing risk, which directly results from the natural properties of the two risks. In addition, attention must be paid to that technical risk has implied effect on the social risk, which is also impacted directly by economic and financial risks. Due to the discrepancy of levels of economy and education among districts, the technical risk, which exits throughout the period of engineering survey, design, construction, equipment manufacturing and production, may leads to conflicts in multi-regional and multi-party projects. Therefore, because of the potential domino effect among risks, it is sensible for project managers to strengthen the earlier prediction of risks and cope with them in time once they occurred.

Figure 7.

Grid project schedule risk multilevel structure based on ISM.

3.3. Risk Evaluation

3.3.1. Establishment of the Evaluation Index System

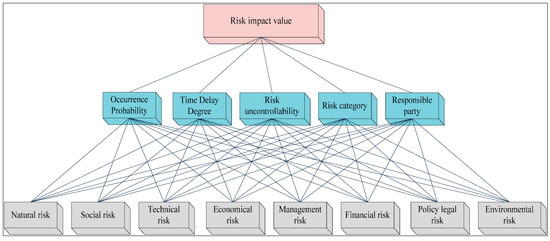

An evaluation index system is established based on Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), in which there are 5 indicators being used to examine the impact of the risks, including traditional indicators as risk probability, risk uncontrollability and duration extension size [22,23,24,25] as well as innovative indicators like risk category and risk responsibility party (Figure 8). In the course of establishing the index system, the authors considered that impact of risks would partly depend on the inherent attributes of risks as the result of risk analysis based on ISM, thus risk category is added as an important indicator. Moreover, it is essential to take responsibility partly into account, since it is obvious that the power company would bear a greater risk if the responsibility party were proprietor, while less risk in other situation.

Based on AHP, the evaluation index system consists of three layers. The top is the goal of this risk assessment, which is the risk impact value. The second layer is the evaluation criterion, which involves risk probability, risk uncontrollability, duration extension size, risk category and risk responsibility party. The bottom layer is the evaluation objects, including natural risk, economic risk, finance risk, social risk, management risk, technical risk, policy-legal risk and environmental risk.

Figure 8.

Risk evaluation index system.

3.3.2. Determination of Risk Impact Value Model

The risk impact value model is:

where, is the impact value of risk ; is the number of survey object ; is the risk probability value; is the length of delayed construction period; is the risk uncontrollability value; represents the risk responsibility party; represents the risk category. represents the weight of risk probability, construction period delay and risk uncontrollability, risk category and risk responsibility party in overall impact value respectively.

3.3.3. Determination of Indicator Scoring Criteria

The rating criteria of the 5 indicators are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Risk evaluation rating rules. (a) Rating rules for occurrence probability, time delay degree and risk uncontrollability; (b) Rating rules for risk category and risk responsibility party.

(a)

| Score | 10 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occurrence probability | Occur in all projects | Occur in 80% projects | Occur in 60% projects | Occur in 40% projects | Occur in 20% projects | Never occur | |

| Time delay degree | Schedule delays 15 weeks or more | Schedule delays 12 weeks | Schedule delays 8 weeks | Schedule delays 4 weeks | Schedule delays 2 weeks | No delays | |

| Risk uncontrollability | Completely uncontrollable | Uncontrollable in many cases | Uncontrollable in 50% cases | Uncontrollable in some cases | Uncontrollable in rare cases | Fully controllable | |

| Remark | When the case is located between the two standards‚ score 1˴3˴5˴7˴9. | ||||||

(b)

| Score | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | |||||

| Risk category | MR, EnR | SR | ER,FR,TR | PLR,NR | |

| Risk responsibility party | designer, contractor, supervisor | proprietor | |||

3.3.4. Determination of index weights

Based on Satty’s 1–9 scale method, the weight judgment matrix is established (Table 6).

Table 6.

Weight judgment matrix.

| p | t | u | c | r | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | 1 | 0.33 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| t | 3 | 1 | 7 | 8 | 8 |

| u | 0.33 | 0.14 | 1 | 5 | 5 |

| c | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 |

| r | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 |

Then, the weights of the 5 indicators are obtained.

Correspondingly,

the consistency index ;

the average random consistency index ;

the test coefficient , approved.

Therefore, the weights of different indicators shown in formula (5) are reasonably practicable.

3.3.5. Original Data of the Value of Each Index

Through questionnaires, 91 respondents have expressed their views based on their professional knowledge and work experience. These respondents include project managers, supervisors, designers and workers on site. The data in Table 7 is the average value of each indicator’s scores.

Table 7.

Scoring value of risks in feasibility study stage.

| Serial Number | Occurrence Probability | Time Delay Degree | Risk Uncontrollability | Risk Categories | Responsible Party |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r1 | 1.24 | 3.75 | 1.03 | 3 | 3 |

| r2 | 2.25 | 3.99 | 3.75 | 3 | 3 |

| r3 | 1.24 | 3.49 | 1.52 | 3 | 3 |

| r4 | 2.48 | 3.75 | 2.51 | 3 | 3 |

| r5 | 2.99 | 2.25 | 2.75 | 2 | 3 |

| r6 | 4.35 | 7.25 | 8.24 | 1 | 3 |

| r7 | 1.48 | 3.50 | 3.11 | 4 | 3 |

| r8 | 0.90 | 2.75 | 1.75 | 3 | 3 |

| r9 | 4.52 | 4.49 | 3.25 | 3 | 3 |

| r10 | 4.79 | 5.75 | 5.12 | 3 | 3 |

| r11 | 3.47 | 6.25 | 4.24 | 3 | 3 |

| r12 | 3.39 | 4.49 | 3.24 | 1 | 3 |

| r13 | 4.02 | 3.99 | 3.52 | 1 | 3 |

| r14 | 1.25 | 3.90 | 1.57 | 3 | 3 |

| r15 | 2.99 | 5.50 | 4.51 | 3 | 3 |

| r16 | 1.50 | 5.97 | 3.25 | 1 | 3 |

| r17 | 2.01 | 5.69 | 4.23 | 1 | 3 |

| r18 | 1.75 | 4.88 | 3.75 | 3 | 3 |

| r19 | 1.25 | 6.46 | 2.12 | 1 | 3 |

3.3.6. Results of the Impact Value of Each Risk

Based on Equation (4), the impact value of all the risks identified could be calculated. For example, the corresponding answers in the project feasibility study stage are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Impact value of risks in feasibility study stage of PGEPs.

From the results, it shows that R6 (the deficiency or delay in obtain relevant departments’ professional assessment report, reviewing comments and relevant agreements) owns maximum potential hazards in feasibility study stage. Followed by two risks whose score is between 5 and 6, they are unclear infrastructure sites and the path information, a wrong project siting as well as power planning changes.

From the perspective of risk properties, we could classify and count the number of risks in different group (Table 8). Though the policy-legal risk is the one with the most serious consequences and would lead to other risks’ appearance based on ISM analysis, it has a relatively low-level risk impact value in the feasibility study stage. The reason may lie in the low probability of occurrence of this kind of risks, such as the risk of changes of national policy, company operating conditions and other conditions. Such risk always occurs following a certain rule or is able to provide a buffer period for managers to get well prepared. Moreover, management risks have a relatively high risk value in this stage and mainly manifest in the deficiency of documents or mistakes in work procedure, as well as unqualified personnel. In addition, technology risks also occupy a significant proportion of all the risks in this stage, and its impact value keeps at a moderate level, which mainly results from the process of investigation, design work in the feasibility study stage.

Table 8.

The number of risks with different properties in different value group.

| Property | TR | SR | MR | PLR | ER | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (2,3) | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| (3,4) | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| (4,5) | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| (5,6) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| (6,7) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

3.4. Risk Prevention

For each risk, specific risk-preventing measures have been ensured through interviews with 12 engineers who have years of experience of engaging in PGEPs. For example, the appropriate risk prevention measures in the feasibility study stage are shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Risk prevention measures in the feasibility study stage.

| Key Work Node | Risk Node | Prevention Measures |

|---|---|---|

| W1 | r1 | Selecting scientific and reasonable economic and technical indicators |

| r2 | Using scientific methods to improve the accuracy of the forecasts | |

| r3 | Collecting data of similar projects, comparing and analyzing the actual situation of the proposed project, and advisable decision-making | |

| r4 | Qualifying the preliminary survey | |

| W2 | r5 | An appropriate increase of compensation standards |

| r6 | Coordination of the relevant departments under the provincial subsidiary company; Planning and design units enhancing communication with other industries | |

| r7 | Adjusting the range of capital-using plan | |

| r8 | Improving the level of program design | |

| W3 | r9 | Qualifying preliminary investigation, strengthening geological prospecting ensuring the information accurate and practical |

| r10 | Enhancing the assessment to the survey and design entities | |

| r11 | Formulating a rational plan of funds’ using | |

| W4 | r12 | Improving the assessment accuracy and quantifying the judgment |

| r13 | Enhancing the assessment to consulting entity | |

| W5 | r14 | Improving the efficiency of work |

| r15 | Strengthen the communication with relevant departments, timely prepare the whole material | |

| r16 | Strengthening the communication with relevant departments | |

| r17 | Strengthening the communication with the provincial subsidiary company | |

| W6 | r18 | Reducing subjective factors and improving the depth and accuracy feasibility study |

| r19 | Strengthening the communication with the State Grid Corporation |

4. Conclusions

In order to make the schedule risk management of PGEPs more systematic and more comprehensive, maintain the sustainable management of PGEPs and promote the sustainable development of these two grid corporations, this paper establishes a three-dimensional risk management system, including management personnel, management periods and management methods. Through questionnaires and expert interviews, the paper identifies 40 key works in the PGEPs and 222 risks throughout the whole construction process. Further, the risk category and the responsible party of each risk are determined. Based on ISM model method, a structural analysis of risks is implemented. Results show that policy-legal risks and natural risks are located at the bottom of the structure, whose occurring will increase the probabilities of other risks’ happening. In contrast, management risks and environmental risks are located on the top, which are the most vulnerable and easily affected by other risks. Social risks are located on the third floor, which can be induced by the economic, financial and technical risks, and financing and economic risks have an interaction on each other. In the risk assessment phase, based on the AHP theory, a three-tier evaluation system is established, where indexes contain risk probability, risk uncontrollability, duration extension size, risk category and risk responsibility party. Based on the survey results, risks of a deficiency or a delay in obtaining relevant departments’ professional assessment report and relevant agreements are the greatest risks during the feasibility study period in a PGEP, followed by the risks of unclear infrastructure information as well as power planning changes. Meanwhile, managing and technical risks have accounted for the largest proportion at this stage and their value of impact is relatively high. In contrast, the impact value of political-legal risks, which locate in the basic position in the ISM analysis, is low at this stage, due to the lower probability of their occurrence. Finally, pre-control measures are suggested and formulated for all the risks.

Based on the proposed framework of schedule risk management for PGEPs, managers can easily find the severity of each risk, be aware of their responsibilities, take actions in advance and keep updating the list. The schedule risk management within the company and throughout the entire construction process can improve the efficiency of risk management of PGEPs and optimize their sustainability, and this framework may obtain some inspiration and reference value for the participants of PGEPs.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous referees and the editor of this journal and gratefully acknowledge equally to the experts and staffs involved in the survey and interviews. The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71173075 and 71373077), Beijing Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 9142016), Beijing Planning Project of Philosophy and Social Science (Grant No. 13JGB054), Ministry of Education Doctoral Foundation of China (Grant No. 20110036120013), Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-12-0850), and the Fundamental Research Funds of the Central Universities of China (Grant No. 2014XS61).

Author Contributions

In this paper, Rao Rao committed to accomplish risk identification, complete questionnaire research and establish the framework of schedule risk management; Xingping Zhang and Zhongfu Tan developed the research ideas and implemented research programs; Zhiping Shi organized and conducted the expert interviews and obtained the corresponding results; Kaiyan Luo carried out the work of risk evaluation and Yifan Feng was responsible for implementing risk analysis based on ISM model.

Appendix

Table A1.

The content of risks in every work node.

| Key Work Node | Risk Node | Serial Number | Key Work Node | Risk Node | Serial Number | Key Work Node | Risk Node | Serial Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | Infeasible economic and technical indicators | r1 | W19 | Design drawings of equipment and materials fail to be recognized on time by relating units. | r75 | W28 | Acceptance file is not complete. | r149 |

| Uncertain trends of objective things & forecast deviation | r2 | Poor design quality, incomplete design content and design conflict among different profession, which lead increase in design changes. | r76 | Civil engineering is not done on time. | r150 | |||

| Mistakes existed in preparation of project proposals | r3 | Design not considers or ill-considers the possibility of the construction. | r77 | Pile foundation of line is lost. | r151 | |||

| Project content is inconsistent with the actual | r4 | Construction drawing fails to be reviewed, signed and published on time. | r78 | Acceptance work delays. | r152 | |||

| W2 | Preliminary geological exploration is blocked | r5 | W20 | Not timely provide the required construction drawings. | r79 | W29 | The existence of quality defects. | r153 |

| Relevant departments’ professional assessment report, reviewing comments and relevant agreements are missing or delay in obtaining | r6 | A full set of construction drawings’ missing, which leads to failure ofcarrying out the review. | r80 | W30 | Equipment has quality problems or does not conform to the requirements of relevant standards. | r154 | ||

| National policy, company operating conditions and other conditions change. | r7 | The owner project department doesn’t send information to the contractors in advance. | r81 | The drawings provided by the equipment suppliers do not tally with the equipment. | r155 | |||

| Project proposal is incorrect or imperfect, a conflict existed against the organization's strategic | r8 | Design and construction drawings are checked as a mere formality, cannot effectively find design errors or omissions. | r82 | Equipment material record is wrong. | r156 | |||

| W3 | Survey data and information is not complete, untrue or incorrect | r9 | Construction drawings’ review and design handover delays. | r83 | Owners project department managers cannot handle engineering problems, resulting in the conflict between construction units and suppliers of materials and equipment. | r157 | ||

| Infrastructure sites and the path information is not detailed, project siting and planning , engineering geology is wrong. | r10 | W21 | Low efficiency of the relevant government departments | r84 | Design field personnel cannot timely, solve design problems in construction process. | r158 | ||

| Power planning changes | r11 | Reply of land expropriation supportive information delays or expires. | r85 | Supervisors’ professional quality is poor, or quantity is small, and fails to guarantee the engineering construction. | r159 | |||

| W4 | Project evaluation and audit is incorrect | r12 | Planning of city, county (district), township’s planning departments is not completely consistent, resulting in delay in boundary survey and planning permission. | r86 | The quality of construction workers cannot meet the construction needs, which leads to rework. | r160 | ||

| Experts or consultants are assessed unqualified | r13 | The nature of the substation land changes. | r87 | Equipment and material’s procurement cycle is long, and the supply is not timely; materials quality cannot meet the construction requirements | r161 | |||

| W5 | Project approval application report prepared is imperfect, and not timely submitted to the NDRC | r14 | Station site environment, topography and geological conditions change | r88 | Less labor contractor or inadequate supply of construction machinery. | r162 | ||

| Planning advice, land pretrial opinion, the EIA and other approved data are incomplete | r15 | Construction site overlies mineral resources and cultural relics, which leads to the change in site. | r89 | Appearing slowdown phenomenon, which results in construction disputes. | r163 | |||

| Projects are not approved through the approval or delay | r16 | Land acquisition costs cannot be timely disbursement and compensation does not reach the designated position | r90 | Existence of various safety and quality risks, providing risks to the progress of the project. | r164 | |||

| Comments of Provincial feasibility review are missing or delayed | r17 | Local residents blocked and other external environmental factors lead to land expropriation obstacles. | r91 | Line channels’ changes caused by external environmental factors. | r165 | |||

| W6 | Deviation of feasibility size and scale approved is too large | r18 | Land use formalities delay. | r92 | Major changes in engineering design. | r166 | ||

| Approved feasibility study of State Grid Corporation and other documents are not issued or delay | r19 | W22 | Environment and weather effects | r93 | Construction workers reduce due to the busy seasons or national holidays, | r167 | ||

| W7 | Approved document of NDRC is not approved and feasibility review comments are not released. | r20 | Path planning adjustment | r94 | Rainy, winter , high temperatures and other weather factors. | r168 | ||

| Tender documents is not rigorous | r21 | Uncertainty of government projects or emergency project of large users causes engineering changes or abnormal duration. | r95 | Construction units have insufficient funds, or unreasonable arrangement. | r169 | |||

| Evaluation methods is not clear | r22 | The compensation does not reach the designated position. | r96 | Equipment and materials’ inventory is wrong, which leads to omissions or insufficient number of procurement. | r170 | |||

| Design tender fails | r23 | Power, water supply and others do not pass, resulting in construction obstacles. | r97 | Project Management Unit cannot timely pay for work according to the contract. | r171 | |||

| W8 | Not entrusted construction management unit | r24 | Slow implementation of municipal roads block station road. | r98 | Water supply, electricity supply facilities and construction machinery equipment for construction always fails. | r172 | ||

| Field leveling progress lags behind. | r99 | Key materials, equipment, machines and tools are theft or damaged. | r173 | |||||

| W9 | Owner project department’s establishment is delayed and staffing does not meet engineering requirements | r25 | Project department and other temporary facilities’ construction lags behind. | r100 | Rework due to substandard construction process.. | r174 | ||

| W10 | Project management framework, safe and civilized construction planning and other pre-planning documentation is not timely issued and of poor feasibility. | r26 | W23 | Contractors and construction supervision is not prepared to timely approach. | r101 | Rework due to the error of construction drawing and other design reasons. | r175 | |

| Collection of market and environmental information concerning substation sites and line channels is not complete. | r27 | Not timely supply adequate materials. | r102 | The management of construction project department cannot meet the needs of the construction, which appears contradictions between each type of work and process.. | r176 | |||

| Progress untimely or incomplete planning. | r28 | Operating conditions are not qualified, so the project manager cannot approve commencement report. | r103 | W31 | Power grid blackout.during the period of national (or local) important festival or activities, and special summer peaks. | r177 | ||

| Information about sites, paths and other is not detailed and incomplete | r29 | Supporting information about the construction permit cannot be approved. | r104 | Line channels’ changes and clearing difficulties caused by external environmental factors. | r178 | |||

| Incomplete external conditions agreement | r30 | Work-start reports attachment is not complete or lack of standardization. | r105 | Equipment manufacturer is not in place, so technical support is not enough. | r179 | |||

| Flow calculation, short circuit current calculation is imperfect, equipment selection does not match. | r31 | W24 | Construction organization design, construction scheme’s analysis is incorrect. | r106 | Design field personnel cannot timely, solve design problems in construction process. | r180 | ||

| Design technology program comparison and other is imperfect. | r32 | Construction progress plan is short of timeliness or operability. | r107 | The overall project is not completed, which leads to normal joint commissioning failure. | r181 | |||

| Poor design feasibility. | r33 | Project land acquisition procedures are not complete. | r108 | Equipment damages or requirements are not uniform, etc., affecting the normal debugging. | r182 | |||

| Equipment prices change; policy-based charge changes; budget estimate is wrong. | r34 | Construction personnel’s qualifications, experience, level and number cannot meet the construction needs. | r109 | Improper arrangement of Scheduling Communication Departments. | r183 | |||

| Municipal planning changes. | r35 | Related procedures and implementation of temporary power supply and water supply projects are not timely. | r110 | W32 | Inspector doesn’t find the quality problems. | r184 | ||

| A grater change exists between sites or line channels’ external environment and the feasibility study stage. | r36 | Works on the table for examination is not completed. | r111 | Self-test problem is not timely rectified. | r185 | |||

| W12 | Designing unit fails to report preliminary design information timely. | r37 | W25 | Disputes caused by poor communication. | r112 | W33 | Difficult to set up kick-off meeting because of inappropriate or incomplete staff. | r186 |

| Construction unit audit is not timely and not seriously; OIA comments fails being submitted timely; preliminary design review of the plan is not submitted in advance. | r38 | Loopholes in safety management. | r113 | Construction unit self test is not serious. | r187 | |||

| Adjustment in municipal planning causes changes in sites, resulting in the need to supplement preliminary information. | r39 | Construction workers do not understand the safety and security of operational knowledge. | r114 | Acceptance department does not fulfill the corresponding duties. | r188 | |||

| Walking trails change and needs to supplement channel protocol. | r40 | No technical measures for safety and quality. | r115 | Production acceptance does not pass. | r189 | |||

| Engineering budgetary estimate exceeds cost estimation. | r41 | Safety and quality technical measure is not perfect. | r116 | The defect in the process of production acceptance is not timely eliminated. | r190 | |||

| Preliminary design scale does not match that of feasibility studies and project approved. | r42 | Disciplinary and violation jobs occur. | r117 | Technical information reported to the dispatch department does not meet all the requirements. | r191 | |||

| Examination is not passed, and a long time needed for modifying. | r43 | Staff does not meet the requirements. | r118 | Commissioning plan is not submitted timely and accurate. | r192 | |||

| Consultant or expert’s assessment is wrong. | r44 | High-risk project is not equipped with safe construction work ticket, and on-site supervision does not reach the designated position. | r119 | Text information is missing. | r193 | |||

| W13 | Projects are not included in the investment plan. | r45 | Special construction work does not have special safety and quality plan; special plan review delays or is not strict. | r120 | W34 | Work which needs to be implemented is unfinished. | r194 | |

| Projects are not included in the provincial annual milestone plan | r46 | W26 | Meeting not being prepared adequately leading to inefficient information transmission. | r121 | ||||

| W14 | Preliminary design review is not in time. | r47 | The errors and omissions in conference, lead to fail reflecting and solving problems in a timely manner. | r122 | W35 | Data transfer exceeds the predetermined time. | r195 | |

| ERP, bidding platform system is not timely established. | r48 | The owner, supervision and construction project department personnel cannot reach the designated position. | r123 | Information transferred is incomplete or non-standard. | r196 | |||

| Design department does not timely reportmaterial and non-material goods tender information. | r49 | Project meetings become a mere formality. | r124 | W36 | Engineering Change Certificate is incomplete or non-standard. | r197 | ||

| Construction management unit’s plans for applying tender is not complete | r50 | W27 | Construction project department management cannot meet the needs of the construction, construction organization and schedule is unreasonable, which appears contradictions between each type of work and process, then affecting the schedule. | r125 | Drawing examination summary is not standardized. | r198 | ||

| Actual bidding is not in accordance with the milestone plan. | r51 | Design field personnel cannot timely, according to the requirement, solve design problems in construction process. | r126 | Construction budget preparation delays and has omissions. | r199 | |||

| Review of tender documents delays. | r52 | Compensation standard along the channel is not consistent. | r127 | BOQ preparation is inaccurate. | r200 | |||

| Bidding content appears missing. | r53 | Appearing slowdown phenomenon, results in construction disputes. | r128 | Controversy existed between construction management unit and construction unit. | r201 | |||

| Quote explain and price adjustment is not clear; BOQ appears big error. | r54 | The owner project department managers cannot handle engineering problems in a timely manner. | r129 | W37 | Incomplete accounts information | r202 | ||

| The tender documents is not rigorous. | r55 | Existence of various safety and quality risks, providing risks to the progress of the project. | r130 | Account transfer risk. | r203 | |||

| The evaluation method is not clear. | r56 | Project Management Unit cannot timely pay for work according to the contract. | r131 | Engineering financial management and control’s specification risk. | r204 | |||

| The bid opening and bid assessment process is not legal. | r57 | Water supply, electricity supply facilities and construction machinery equipment for construction always fails. | r132 | Cash flow problems and other fund management risk. | r205 | |||

| The bidding does not meet standard. | r58 | Experiencing excessive groundwater, quicksand, geological faults, caverns; discovering buried underground cultural relics; discovering remnants of war ammunition in the construction. | r133 | W38 | Engineering archived data’s quality has defects. | r206 | ||

| Project pre-tender estimate leaks. | r59 | Earthquakes, floods and other force majeure risks to the progress of the project. | r134 | Quality accident happens after putting into operation. | r207 | |||

| The bidding documents issued lag behind. | r60 | Major political events, social activities, and changes in the economic situation. | r135 | Substandard project post-maintenance work. | r208 | |||

| W15 | Dispute exists against principal terms, resulting in signing delay. | r61 | Line channels’ changes caused by external environmental factors. | r136 | The time of engineering final accounts and approval is long. | r209 | ||

| Differences exist in technical parameters of equipment and materials, resulting in supplies contract delay. | r62 | Major changes in engineering design. | r137 | Project is poorly operated after putting into operation. | r210 | |||

| The contract is not signed within the required time, bringing engineering specifications management risk. | r63 | Construction workers reduce during the busy seasons or national holidays. | r138 | Environmental protection, water conservation and other special inspection does not pass. | r211 | |||

| W16 | The approval from the feasibility study delays, and no approval basis for preliminary design. | r64 | Rainy, winter, high temperatures and other weather factors. | r139 | W39 | The contract check is not serious. | r212 | |

| Provincial companies, consulting organizations fails to issue the preliminary design review comments file on time. | r65 | Construction units have insufficient funds, or arrange unreasonable. | r140 | Inspection records of concealed works are incomplete. | r213 | |||

| State Grid Corporation fails to issue the preliminary design review comments file on time. | r66 | Less labor contractor or inadequate supply of construction machinery. | r141 | Design Change Certificate is not standardized. | r214 | |||

| W17 | Capital budget request delays. | r67 | Construction materials’ high market price, long procurement cycle and substandard quality. | r142 | Engineering quantity’s check is not accurate. | r215 | ||

| Cost estimate is incorrect. | r68 | Equipment and materials’ inventory is wrong, lead to omissions or insufficient number of procurement. | r143 | Pricing not accords with the contract terms. | r216 | |||

| Improper arrangement of operating expense budget. | r69 | The level of construction workers cannot meet the construction needs, which leads to rework. | r144 | Fee calculation errors. | r217 | |||

| Application review and disbursement of project funds delays. | r70 | Standard construction process fails, resulting in rework. | r145 | The auditor is not in conformity with the quality standard. | r218 | |||

| W18 | Procedures dealing with construction permits more than enough time. | r71 | Rework due to the error of construction drawing and other design reasons. | r146 | W40 | Project image data does not meet the requirements. | r219 | |

| W19 | Technical obstacles caused by inaccurate infrastructure sites, detailed geological exploration path information and others. | r72 | Supervisors’ professional quality is poorer, or quantity is small, who fail to take effective measures to guarantee the engineering construction. | r147 | Quality accident happens after putting into operation. | r220 | ||

| Construction design changes caused by geological conditions and channel environment change. | r73 | W28 | Civil engineering’s quality does not meet the requirements. | r148 | Environmental protection, water conservation and other special inspection does not pass. | r221 | ||

| Equipment manufacturers cannot timely deliver drawings, so design units do not timely receive information. | r74 | Standard work preview and review work does not meet the standard. | r222 |

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gu, Y.G.; Luo, Z.; Shan, B.G. Outlook 2013 of Power Supply and Demand in China and Related Suggestions. Electr. Power 2013, 46, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.B.; Chen, B.; Yu, Y.S. Research on Rorecasting Electricity Demand oR the12th Rive-year and 2020. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2011, 21, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Merna, T.; Al-Thani, F.F. Corporate Risk Management; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, C. Project risk analysis and management-the PRAM generic process. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 1997, 15, 273–281. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Risk Management. A Risk Management; Standard Institute of Risk Management: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Project Management Institute. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge; Project Management Institute Standards Committee: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, P.J.; Bowen, P.A. Risk and risk management in construction: A review and future directions for research. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 1998, 5, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Vasconcelos, A.; Numes, M. Supporting decision making in risk management through an evidence-based information systems project risk checklist. Inf. Manag. Comput. Secur. 2008, 16, 166–186. [Google Scholar]

- Tah, J.H.M.; Thorpe, A.; McCaffer, R. Contactor project risks contingency allocation using linguistic approximation. Comput. Syst. Eng. 1993, 4, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirba, E.N.; Tah, J.H.M.; Howes, R. Risk interdependencies and natural language computations. J. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 1996, 3, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Wang, Z.F. Non-additivity analysis on scheduling risks based on Bayesain networks. Syst. Eng.-Theory Pract. 2011, 31, 1517–1523. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.Y. Correlation analysis of scheduling risks based on BN-CPM. J. Hydroelectr. Eng. 2011, 30, 199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.B.; Lu, G.S.; Li, P.; Zhang, C.S. Grid Construction Project Schedule Risk Analysis Based on Rough Set Theory. East China Electr. Power 2012, 40, 1325–1327. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.L.; Wang, D.Y.; Liu, X.J. Study on the risk analysis and benefit sharing in BT construction project. J. Hunan Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2012, 39, 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.Q.; Liu, Y.J.; Yu, J.R. Applying research of SCERT on risk analysis and management of large project. China Soft Sci. 2002, 7, 105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.; Kayis, B.; Amornsawadwatana, S. A review of techniques for risk management in projects. Benchmarking 2007, 14, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Morote, A.; Ruz-Vila, F. A fuzzy approach to construction project risk assessment. Int. J. Project Manag. 2011, 29, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, Y.J.; Song, T. Study on engineering project risk management based on Bayesian network. J. Shenyang Univ. Technol.: Soc. Sci. Ed. 2008, 1, 239–244. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.Y. Bayesian network inference on risks of construction schedule cost[C]. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference of Information Science and Management Engineering, Xi’an, China, 7–8 August 2010; Volume 2, pp. 15–18.

- Taroun, A. Towards a better modeling and assessment of construction risk: Insights from a literature review. Int. J. Project Manag. 2014, 32, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T. The two-dimensionality of project risk. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 1996, 14, 185–186. [Google Scholar]

- Jannadi, O.A.; Almishari, S. Risk assessment in construction. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2003, 129, 492. [Google Scholar]

- Aven, T.; Vinnem, J.; Wiencke, H. A decision framework for risk management, with application to the offshore oil and gas industry. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2007, 92, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagno, E.; Caron, F.; Mancini, M. A multi-dimensional analysis of major risks in complex projects. Risk Manag. 2007, 9, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioffi, D.F.; Khamooshi, H. A practical method of determining project risk contingency budgets. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2009, 60, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.F.; Yu, Y.C. BBN-based software project risk management. J. Syst. Softw. 2004, 73, 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Molenaar, K.R. Programmatic cost risk analysis for highway megaprojects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2005, 131, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Analytic hierarchy process. In Encyclopedia of Biostatistics; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Tah, J.; Carr, V. A proposal for construction project risk assessment using fuzzy logic. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2000, 18, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, B.Q. Comprehensive risk assessment model of complex product systems innovation based on Fuzzy AHP. J. Tongji Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2008, 36, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, L.; Qi, Y.; Li, Q.M. Information security risk assessment based on AHP and fuzzy comprehensive evaluation. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2009, 45, 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.S.; Wang, S.F.; Guo, X.L. Research on evaluation risk of power market based on Monte Carlo simulation. Relay 2007, 35, 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.H.; Song, Y.X.; Song, CH.Q. Risk evaluation of wartime equipment supply chain based on TOPSIS method with fuzzy ameliorated Entropy Weight. Comput. Digit. Eng. 2012, 40, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, S.X.; Zhang, Y. Credit risk evaluation in commercial bands using TOPSIS model based on Entropy Weights. J. Inf. 2008, 27, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.L.; Zhou, Y.N.; Zheng, L. The process variance analysis model distinguishing the critical and non-critical path. Constr. Manag. Modern. 2009, 23, 502–504. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.X.; Ye, J.; Zhang, X. Project object cost and time control research. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. 2001, 14, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, P.X.W.; Zhang, G.M.; Wang, J.Y. Understanding the key risks in construction projects in China. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2007, 25, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sara, M.S.; Amaya, P.E.; Angel, M.E.L.; Pedro, V. Project risk management methodology for small firms. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2013, 32, 327–340. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, R.; Norman, G. Risk Management and Construction; Blackwell Science Pty Ltd.: Victoria, Australia, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.Q.; Tiong, R.L.K.; Ting, S.K.; Ashley, D. Evaluation and management of foreign exchange andrevenue risks in China’s BOT projects. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2008, 18, 197–207. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, W.; Reid, H. Identifying and Managing Risk; Pearson Education: French Forest, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, L.Y.; Wu, G.W.C.; Ng, C.S.K. Risk assessment for construction joint ventures in China. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2001, 127, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).