Abstract

The sustainability of the beef and dairy industry requires a systems approach that integrates environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and economic viability. Over the past two decades, global genetics consortia have advanced data-driven germplasm programs (breeding and conservation programs focusing on genetic resources) to enhance sustainability across cattle systems. These initiatives employ multi-trait selection indices aligned with consumer demands and supply chain trends, targeting production, longevity, health, and reproduction, with outcomes including greenhouse gas mitigation, improved resource efficiency and operational safety, and optimized animal welfare. This study analyzes strategic initiatives, germplasm portfolios, and data platforms from leading genetics companies in the USA, Europe, and Brazil. US programs combine genomic selection with reproductive technologies such as sexed semen and in vitro fertilization to accelerate genetic progress. European efforts emphasize resource efficiency, welfare, and environmental impacts, while Brazilian strategies focus on adaptability to tropical conditions, heat tolerance, and disease resistance. Furthermore, mathematical models and decision support tools are increasingly used to balance profitability with environmental goals, reducing sustainability trade-offs through data-driven resource allocation. Industry-wide collaboration among stakeholders and regulatory bodies underscores a rapid shift toward sustainability-oriented cattle management strategies, positioning genetics and technology as key drivers of genetically resilient and sustainable breeding systems.

1. Introduction

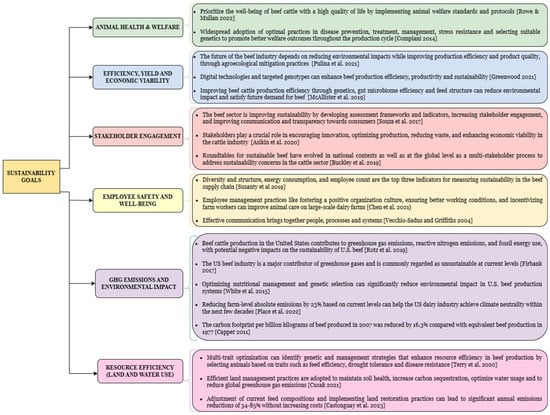

The global beef and dairy production industries are encountering various challenges, which include maintaining sustainability metrics, competitiveness amid declining prices, rising costs, intense competition, and increasing public scrutiny. These challenges require solutions that are sustainable, appropriate, technically feasible, cost-effective, and publicly acceptable [1]. The transition to sustainable beef and dairy production is inevitable, regardless of the challenges. The multi-trait optimization of germplasm and advanced reproductive technologies offers a vital solution by addressing these challenges holistically. This approach enables the industry to achieve the balanced alignment of various objectives (Figure 1), including air and greenhouse gas emissions, land and water resources, employee safety, and animal health and well-being, as well as efficiency and yields [2,3,4,5]. However, this multi-trait complex system optimization process will not happen spontaneously; rather, it must be coordinated with the policy implementation plans of governments, policymakers, and NGOs [6]. Policymakers are increasingly called upon to evaluate the impacts of their policies and strategies concerning sustainable development. This requires the use of agricultural systems decision models as tools and data to identify and assess the potential environmental, economic, and social effects of different policy options [7]. Advances in computer modeling and artificial intelligence, coupled with the complexity and interconnectedness of global sustainability challenges, will likely drive the demand for credible, realistic, transparent, and useful models, necessitating a multi-dimensional and interdisciplinary approach [8].

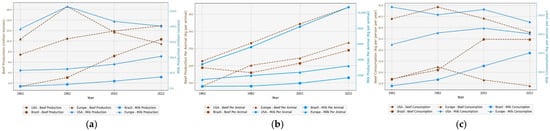

Figure 1.

The changing landscape of beef and dairy production: production trends and transformations over time [9]. They are listed as (a) beef and milk production across the USA, Europe, and Brazil (1962–2022); (b) beef and milk production per animal in the USA, Europe, and Brazil (1962–2022); (c) per capita beef and milk consumption in the USA, Europe, and Brazil (1962–2022).

Our study aims to investigate sustainability-enhancing activities in the global beef and dairy industries through three objectives: (1) emphasizing the multi-trait nature of sustainability dimensions in the US, Europe, and Brazil; (2) exploring the propagation of multi-trait optimized germplasm by cattle genetic consortia, aligned with dynamic sustainability metrics designed by stakeholders, including consumers; and (3) highlighting the need to integrate decision models and data-driven platforms to make informed decisions, ensuring continuous progress towards evolving sustainability targets.

2. Regional Trends in Beef and Dairy Population, Production, and Consumption Patterns in the USA, Europe, and Brazil

Cattle production involves breeding animals to produce meat, milk, and other dairy products for human dietary intake [10]. Beef and milk production faces challenges in balancing food needs and sustainable development; however, new technologies can aid in optimal development and biodiversity conservation [11]. The USA, Brazil, and Europe are the three largest beef- and milk-producing regions globally. An analysis of historical and current trends in cattle population, beef production, and milk production across the USA, Brazil, and Europe from 1962 to 2022 reveals distinct regional patterns. Cattle production is a major source of agricultural income in the United States, accounting for 18% (USD 66.2 billion) of the total cash receipts from agricultural commodities in 2019 [12]. In the USA, the cattle population peaked at 250.65 million in 1985 but declined to 87.2 million in 2024. According to the United States Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Statistics Service (USDA NASS), the American cattle inventory comprised 28.2 million beef cattle and 9.36 million dairy cattle as of 2024, collectively representing the world’s second-largest cattle population. In contrast, Brazil has experienced substantial expansion in its cattle herd through intensified production systems and productivity enhancements, positioning it as the global leader in cattle production and beef export volumes. Conversely, European cattle populations have undergone systematic contraction, declining from approximately 197.9 million head in 1962 to 113.22 million head in 2022, a reduction of 42.7% over this six-decade period. These dynamic trends in cattle populations highlight regional differences in cattle production and its economic and environmental impacts. The USA and Europe have experienced a decline in cattle numbers, yet their beef and milk production per animal have increased significantly, indicating advancements in productivity and efficiency.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [9], beef production trajectories diverged significantly across regions between 1962 and 2022. United States beef production increased by 74.1%, from 7.41 to 12.89 million tonnes, while European production peaked at 16.56 million tonnes in 1982 before declining by 42.8% to 9.47 million tonnes by 2022. Brazil experienced the most substantial expansion, increasing by 661%, from 1.36 to 10.35 million tonnes. Dairy production similarly reflected regional heterogeneity. The United States’ milk output increased by 79.5% to 102.75 million tonnes, while European production peaked at 264.08 million tonnes in 1982 before declining by 24.1% to 200.44 million tonnes by 2022. Brazil demonstrated pronounced growth of 550%, rising from 5.53 to 35.94 million tonnes (Figure 1a). Despite declining cattle inventories, per animal beef productivity increased substantially in the USA (73.6%, from 213.20 to 370.30 kg) and Europe (91.6%, from 139.4 to 267.20 kg), whereas Brazil showed modest gains of 26.3% (194 to 245 kg). Similarly, the milk yield per animal improved dramatically in the USA (3400.2 to 10,667.5 kg), Europe (1428.4 to 3164.9 kg), and Brazil (556.8 to 1669.4 kg), reflecting advancements in dairy management and efficiency (Figure 1b). Even though Brazil has witnessed a substantial rise in its cattle population (from 57.7 million in 1962 to 234.3 million in 2022) and total production, its per capita beef and milk consumption remain lower compared to the USA and Europe.

Per capita meat consumption varies significantly across countries, often reflecting economic transitions and social–economic development trends. Globally, the average per capita meat consumption has risen, indicating that meat production has increased at a rate surpassing that of human population growth [9]. Regardless of the fact that meat intake among individuals in European and North American regions remains substantially higher than global averages [13,14], per capita beef consumption declined in the USA (43.87 to 37.81 kg) and Europe (16.82 to 13.88 kg) from 1962 to 2021, while per capita beef consumption in Brazil has nearly doubled, with a rise of approximately 16.96 to 34.66 kg, reflecting a growing domestic market. There is a strong positive correlation between per capita meat consumption and the average gross domestic product (GDP) per capita; wealthier nations tend to exhibit higher levels of meat consumption. Similarly, milk consumption decreased in the USA (271.14 to 231.39 kg) and Europe (172.28 to 200.74 kg), whereas Brazil experienced a significant rise (62.78 to 150.03 kg), indicating improved availability and dietary preferences (Figure 1c).

Globally, sustainable food and agriculture (SFA) plays a crucial role in supporting all four pillars of food security, namely availability, access, utilization, and stability, while also addressing the key dimensions of sustainability, including environmental, social, and economic aspects [14].

3. Multi-Dimensional Sustainability Analysis in Beef Production: Insights from the USA, Europe, and Brazil

Sustainability is a dynamic property of complex adaptive systems, characterized by continuous evolution that requires persistent governance and adaptive management. The beef industry is improving its sustainability through various assessment frameworks, stakeholder engagement, and increased transparency, but it needs to clarify the concept of sustainability and strengthen cooperation among national roundtables [15]. The multi-stakeholder (including input from the United States National Cattlemen’s Beef Association—NCBA) Global Roundtable for Sustainable Beef (GRSB) recently defined sustainable beef as a product that is socially responsible, environmentally sound, and economically viable. This definition emphasizes prioritizing the planet (focusing on natural resources, efficiency, and innovation), people (including community well-being and food safety), animals (addressing animal health, welfare, and efficient practices), and progress (encompassing natural resources, community, animal welfare, food quality, and innovation) [16]. The numerous trade-offs between environmental and economic goals make it difficult to meet the challenge of sustainable beef production on a global scale [17]. Enhancing traditional husbandry practices and addressing welfare concerns through evidence-based research, practical interventions, consumer perception analysis, and educational initiatives can improve the beef industry’s sustainability [18].

Global meat production had increased more than threefold by 1975, surpassing 350 million tonnes annually. Meat, especially beef, is the agricultural commodity that contributes the most to the US economy in terms of agricultural receipts. However, it is also the most dependent on natural resources and generates the highest environmental impact per kilocalorie or gram of protein among available food resources for the human population [19]. Protein-based nutraceuticals derived from highly mineralized, collagen-rich beef have high amino acid potential, making them a valuable source of specialized biologically active additives [20], and offer a promising approach to address escalating global protein needs [21]. Ruminant meat lipids provide heart-healthy cis-monounsaturated fatty acids and bioactive phospholipids, which can improve human health and contribute to global food security [22]. Furthermore, the increasing genetic potential for marbling increases the likelihood of achieving higher yields and better-quality grade outcomes in commercial beef cattle [23].

The beef yield per animal has increased over time in the USA, Brazil, and Europe due to advances in genetics, production, and management practices and environmental management. Beef production in the USA is highly technology-intensive, incorporating advanced reproductive management techniques, genetic improvement strategies, and various feed processing methods to improve its efficiency and cost of production [24]. Likewise, the European Union is among the leading beef producers worldwide, holding the third-largest share, with strong production efficiency and adaptability driven by a diverse range of animal types, including cows, bulls, steers, and heifers, and various farming systems, such as intensive, extensive, mixed breeders, and feeders [25]. However, the European beef sector faces challenges in production efficiency, sustainability, and animal welfare, necessitating new strategies and research to adapt to changing market demands and evolving research objectives [26]. Analogously to the USA and Europe, the achievement of sustainable beef cattle development in Brazil necessitates the integration of advanced digital technologies and the implementation of resilient, environmentally responsible supply chain management practices with strategies that can promote human, environmental, and animal welfare [27]. As an example, the Sustainable Tension Index can help to identify areas in the Brazilian pampa biome with potential for sustainable beef production, aiding decision making for farm managers and politicians [28]. Intensive beef farming has expanded to the Brazilian Amazon, where confinement practices have led to higher productivity rates and reduced deforestation [29]. These productivity gains and land-saving strategies have significantly contributed to growth in Brazilian beef production, reducing the need for extensive pasture expansion [30]. Multiple initiatives and knowledge dissemination efforts regarding sustainable practices within the beef supply chain are being implemented to enable a coordinated approach to production, processing, and distribution across diverse organizations, as they capitalize on market opportunities for sustainable livestock in Brazil [31]. Differences in beef production across countries reflect factors like natural resource availability, climatic conditions, population demographics, cultural traditions, and the level of economic development [32]. Cultural and lifestyle differences influence the sustainability of beef production in different regions [33]. In addition, vegetation and demographic pressures pose significant challenges to the sustainability of regionally interconnected beef production systems. However, advancements in beef cattle production are necessary to secure the industry’s future sustainability [21].

Beef cattle are one among the most important sources of atmospheric CH4, and the mitigation of this gaseous emission has been highlighted as a tool to slow global climate change [34]. Among major animal-source foods, beef production per kilogram demands the most land and energy resources and contributes the highest greenhouse gas emissions, with pork, chicken, eggs, and milk having progressively lower impacts [35]. In recent decades, the beef industry has faced increasing scrutiny from both climate scientists and the public due to its perceived contribution to climate change [36]. Hence, concerns related to climate change and animal welfare necessitate balanced breeding objectives and selection strategies that prioritize sustainability, including traits such as health and longevity [37]. Tedeschi and Beauchemin [38] stated that US beef cattle emissions account for about 2.2% of the total anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, equating to 22.6% of the total US agricultural emissions. Feed additives could reduce these emissions by 5 to 15% and would align with efforts to enhance the environmental sustainability of beef production. US beef cattle emissions were reduced by about 30% from 1975 to 2021, and potential improvements in livestock and crop production systems could result in a 4.6% reduction in global CO2e emissions by 2030. Efforts to minimize the environmental burden of beef production are anticipated to be the most critical determinant of enhanced sustainability outcomes [38].

Carbon-reduced beef production, processing, and trade techniques must be encouraged and supported to alleviate the effects of global warming and enable progress towards climate neutrality. The carbon footprint of beef production in Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas is estimated at 18.3 ± 1.7 kg CO2e per kg of carcass weight, with the cow–calf phase accounting for most of the emissions [39]. According to the USDA Meat Animal Research Center, the beef production system has decreased its carbon footprint by 6%, but its water footprint has increased by 42% due to increased irrigated corn production [40]. Meanwhile, beef production in Europe has high potential for the mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions, with an average carbon footprint of 20.5 kg CO2e per kg carcass [41]. The carbon footprint of beef cattle production ranges from 8 to 22 kg CO2e per kg of live weight, with significant reductions in Canada, the US, Europe, Australia, and Brazil over the last 30 years due to sustainable land management practices [42]. Minimizing the carbon footprint of beef cattle through crossbreeding, genetic improvement, and improved productivity per constant unit can effectively mitigate the effects of climate change [43]. The net greenhouse gas emissions from beef production can be significantly reduced through improved management practices, achieving up to a 46% reduction per unit of beef via carbon sequestration strategies on grazed land and an additional 8% reduction through enhanced growth efficiency [44]. These initiatives prioritize preserving and enhancing carbon stocks in soils and landscapes. According to [45], soil carbon sequestration offers the greatest potential for mitigating GHG emissions from beef production, accounting for up to 80%, followed by growth enhancement technologies (16%), grazing management improvements (7%), and dietary modifications (6%).

The efficient use of resources like feed, water, and land is critical for sustainable beef production. Relative to other livestock systems, beef production exhibits lower efficiency in transforming natural resource inputs into edible outputs [4]. Organic beef production systems are slightly more profitable but have a stronger influence on global warming and land use [5]. As competition for land and water resources escalates, enhancing the efficiency of livestock systems becomes imperative for sustainability [46]. Numerous producers and farmers already make contributions towards environmental stewardship, ensuring that, through responsible resource management and ecosystem restoration, the global beef value chain can achieve net positive environmental outcomes [47]. Each component of the beef supply chain can be optimized to reduce the water footprint by optimizing and integrating grazing systems (selecting water-efficient forage species like C4 plants), methods (utilizing precision agriculture techniques like soil mapping to optimize water use), and external inputs (optimizing fertilizer applications to increase dry matter production with fewer water requirements) to enhance ecosystem services, thereby decreasing the overall environmental impact of livestock production [48]. In many instances, producers are adopting soil health and water conservation practices that can enhance agricultural sustainability in water-limited environments by increasing soil organic carbon storage, water infiltration, and microbial activity and decreasing nitrogen fertilizer inputs [49]. A multi-indicator approach combining carbon and water footprints can facilitate more extensive awareness of the environmental impacts in beef cattle production systems [50]. Such approaches are designed to preserve and restore grazing areas, improve resilience, safeguard forests and natural habitats, enhance biodiversity, and reverse environmental decline [51].

4. Innovations in Dairy Production: Enhancing Cattle Welfare, Genetic Improvements, Technological Advancements, and Herd Management Strategies for Dairy Sustainability

Dairy production provides high-quality nutrients, animal welfare, and environmental sustainability while maintaining economic viability for dairy farmers [52]. Dairy herd turnover and sensible culling decisions improve profitability, welfare, and sustainability [53]. Sustainability in the dairy industry involves achieving competitive growth and efficiency in dairy farming and processing, while addressing environmental, economic, and social aspects [54]. The dairy industry endeavors to harmonize environmental stewardship, economic sustainability, and community well-being while adapting to evolving resources, technological advancements, and consumer preferences. Sustainable dairy management practices should complement international perspectives from export markets, international organizations, and dairy corporations. Sustainable agriculture relies on emphasizing genetic diversity and resilience in dairy cattle, employing adaptive genetic improvement techniques, and ensuring a consistent and accurate data flow [55].

Strategic interventions can significantly improve dairy production in developing countries, addressing challenges like feed, management, health, and food safety, contributing to meeting the global demand and UN Sustainable Development Goals [56]. Leading dairy countries in the EU focus on implementing sustainability principles, focusing on environmental impacts, animal welfare, health, and breed management issues [57]. Climate change may positively impact dairy cow production in Central Europe by potentially increasing the fodder quantity through prolonged growing seasons and slight rises in ambient temperature and CO2 levels. However, mitigation strategies will be essential to ensure adequate nutrition and maintenance of performance [58]. Brazil’s dairy farming plays a vital role in the country’s economy, with public policies supporting milk quality and safety. In Brazil, dairy products contribute significantly to the intake of key nutrients, providing 6.1–39.9% of daily energy, 7.3% of protein, 16.9% of saturated fat, 11.1% and 4.3% of total sugars, and 10.2–37.9% of calcium, vitamin D, phosphorus, vitamin A, and vitamin K. However, the average daily consumption is only 142 g per person, which is less than one standard portion and fails to satisfy the 2006 Brazilian dietary guidelines, with a recommendation of three portions of milk and dairy products per day [59]. However, its limited per capita availability in Brazil is primarily due to high production costs and lower milk quality [60]. There is a need for policies and practices that align with local and international expectations, particularly in the dairy industry of Brazil [61]. In Brazil, dairy farms face common welfare and production issues, such as subclinical mastitis and tick infestations, but also specific issues like lameness and hock injuries [62]. Sustainability objectives prioritize the well-being of dairy cattle by promoting the widespread adoption of optimal practices in disease prevention, treatment, management, and stress resistance and selecting suitable genetics to promote better welfare outcomes throughout the production cycle. In Parana, Brazil, large dairy operations exhibit greater economic, environmental, and social sustainability, increasing their likelihood of enduring over the medium and long term [63].

According to Borawski et al. [64], the US milk market experienced notable changes between 2009 and 2018. During this period, the number of dairy cows increased slightly by 2%, from 9.2 million to 9.4 million. However, the milk yield per cow saw a significant rise of 13%, leading to a 15% overall increase in milk production. Despite this growth in production, the per capita consumption of liquid milk decreased from 112 kg in 1975 to 66 kg in 2018, while the total dairy product consumption per person increased from 244 kg to 293 kg over the same period. A life cycle assessment of the US dairy industry in 2008 highlighted its environmental impact, and, by 2017, advancements in dairy farming practices had reduced water use by 30%, land use by 21%, and the carbon footprint by 19% per gallon of milk compared to 2007 [65]. The dairy sector aims to be greenhouse gas-neutral and improve both water use and water quality by the year 2050, with US dairy farmers committed to enhancing soil health and protecting biodiversity [66]. Beef-on-dairy breeding strategies enhance profitability and sustainability in dairy production, and it is a potential solution to mitigate the GHG footprint of beef [67]. Increasing animal productivity, improving the genetic potential, and reducing the herd size can substantially reduce GHG emissions from livestock production systems [68]. Beef production from dairy calves has lower environmental impacts than that from suckler herds. Nevertheless, adopting sustainable management approaches is critical for better environmental performance [69]. The sustainability of the dairy and beef industry encompasses a range of factors that provide a roadmap with interconnected actions that can support countries in selecting and prioritizing resources to accelerate the transition towards sustainable approaches (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sustainability goals pursued by the global beef and dairy industries. Multiple competing animal and environmental traits of interest are being optimized by cattle geneticists and production management experts (indicating an intensive multi-trait optimization approach) [3,15,17,44,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84].

5. Landscape Analysis of Genetic Consortia in the Beef and Dairy Industries of the USA, Europe, and Brazil: Driving Sustainability Through Adaptive Genomic Selection Indices and Germplasm Innovation

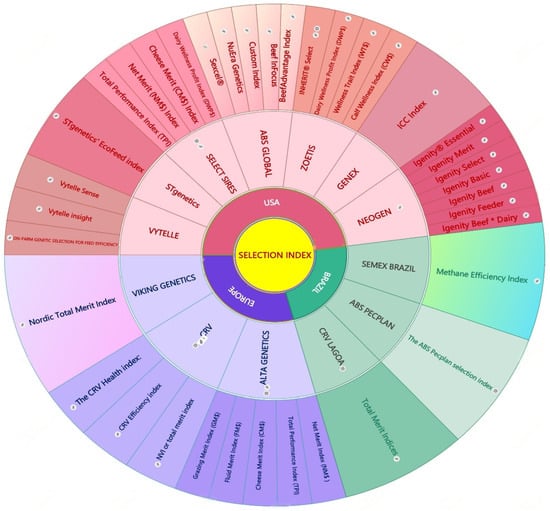

Genomic information and genetic selection indices integrated into genetic evaluations significantly benefit traits linked to welfare and sustainable production in both beef and dairy systems. In the USA, several genomic selection indices are utilized by companies to enhance the cattle breeding efficiency and profitability. ABS Global’s Beef Advantage Index uses multi-trait optimization to select beef sires for dairy operations, emphasizing traits crucial for reproductive success, growth, feed intake, and carcass quality. Integrating growth and carcass characteristics into breeding goals for combined dairy and beef production systems can boost economic returns and improve self-reliance [85]. The Custom Index of ABS Global allows dairy producers to tailor genetics to their specific needs, leading to faster genetic progress and improved profitability. The EcoFeed Index by ST Genetics focuses on feed efficiency and environmental sustainability, targeting animals that maximize production while minimizing feed resources and GHG emissions. Innovative monitoring technologies for the assessment of dairy cattle phenotypic traits can enable more sustainable production by lowering greenhouse gas emissions [86]. Zoetis offers the Dairy Wellness Profit Index (DWP$), focusing on maximizing productivity, efficiency, and sustainability across the dairy and beef industries. The Net Merit and Cheese Merit indices, developed by Select Sires and Alta Genetics, provide comprehensive tools for the prediction of profit potential in various milk markets, emphasizing key traits like milk yields, fertility, and longevity (Figure 3). Targeting traits related to welfare, health, longevity, environmental efficiency, and resilience in breeding programs is advancing sustainability and operational efficiency in dairy cattle [87].

Figure 3.

Genomic selection tools and multi-trait optimized selection indices of genetic consortia in the USA, Europe, and Brazil, which are being periodically redesigned to contribute to the sustainability aspirations of the cattle industry. Figure credit: https://www.edrawmind.com/app/editor/uArp5zpmZyJppxS3RLUBEqy1lvx0Yrsc?share=1&page=8889934692 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

In Europe, genomic selection indices are geared towards optimizing both productivity and sustainability. Viking Genetics’ Nordic Total Merit (NTM) index focuses on enhancing herd profitability and functionality by prioritizing health, reproduction, and production traits. CRV’s Health and Efficiency Indexes guide dairy farmers in improving herd health, fertility, and overall efficiency, leading to increased profitability and sustainability. Similarly, the NVI or Total Merit Index used in the Netherlands and Flanders integrates production, longevity, fertility, and cow health to guide breeding programs towards enhanced farm income and consumer acceptance. These European indices place a strong emphasis on health and sustainability, aligning with regional goals of improving cattle welfare while boosting production (Figure 3).

In Brazil, genomic selection tools are pivotal in driving cattle production advancements, and several companies in Brazil utilize specific selection indices to improve livestock genetics and enhance the production efficiency (Figure 3). Semex Brazil employs the Methane Efficiency Index, which focuses on selecting animals based on their methane emissions efficiency, contributing to environmentally sustainable livestock production. Incorporating low-emission traits into dairy cattle selection strategies can lower the environmental burden of dairy production [88]. The methane intensity could be decreased by 24% by 2050 through the incorporation of CH4 production into breeding objectives [89]. However, genetic progress in feed efficiency and lowering methane outputs in replacement heifers offer a pathway to more sustainable beef cattle systems [90]. In particular, selecting for residual methane emissions holds significant potential, as it allows for the selection of low-emission animals while maintaining performance in key economic traits [91]. Bell and Jauernik [92] argued for incorporating a customized profit and carbon merit index as a practical tool for the identification of sustainable dairy cows and replacement heifers, ultimately increasing profitability and reducing carbon emissions in commercial dairy herds. These methods maximize profit without compromising welfare [93]. The ABS Pecplan company in Brazil utilizes the ABS Pecplan Selection Index, a comprehensive system designed to prioritize animals according to genetic and economic characteristics essential for success in the beef and dairy industries. Similarly, CRV Lagoa uses the Total Merit Index, an index that evaluates overall animal performance by incorporating multiple economic and genetic factors, ultimately aiming to improve herd efficiency and profitability. Additionally, the CRV Health Indexes aim to improve dairy herd health and efficiency in Brazil, similarly to Europe, ensuring that Brazilian farmers can produce healthier, more sustainable cattle while maintaining profitability. Brazilian genetic consortia, including ABS Pecplan, CRV Brasil, and Semex Brazil, emphasize multi-breed and indigenous cattle programs, particularly focusing on the integration of European and Zebu germplasm for tropical environments. These companies are instrumental in driving genetic advancement and promoting sustainable livestock production in Brazil.

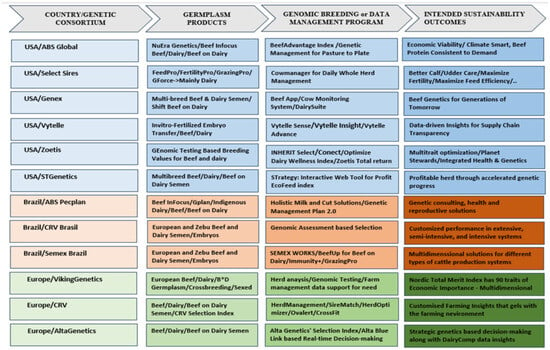

Figure 4 presents a variety of germplasm products offered by different genetic consortia across the USA, Brazil, and Europe, focusing on enhancing cattle genetics for beef and dairy production. These products include multi-breed semen and embryos, with companies like ABS Global, Genex, and CRV Brasil providing crossbreeding solutions to improve productivity and adaptability. Fertility and reproductive technology, such as in-vitro-fertilized embryo transfer, is offered by companies like Vytelle to improve the reproduction efficiency in both beef and dairy operations. Reproductive efficiency and health improvements are achieved through genomic selection and fertility-focused germplasm, leading to higher conception rates, reduced calving difficulties, and improved animal welfare. Targeted genetic solutions from organizations like Select Sires aim to maximize feed efficiency and reproductive success. Genetic strategies and management innovations can improve the beef production efficiency and sustainability by minimizing feed for maintenance and incorporating appropriate indicator traits in national cattle evaluation systems [94]. However, beef-on-dairy programs from ABS Global, Semex, and STGenetics introduce beef genetics into dairy operations to increase the value of dairy bull calves while maintaining dairy herd performance. Genomic testing-based selection from companies like Zoetis helps producers to make informed breeding decisions, enhancing genetic diversity and productivity and supporting precision breeding strategies for sustainable and profitable cattle production.

Figure 4.

Global genetic consortia in cattle breeding: germplasm products, genomic programs, and sustainability outcomes.

The sustainability outcomes of these genetic programs focus on economic viability, climate-smart solutions, enhanced herd health, and optimized production systems. Additionally, evaluating genetic resistance to disease, climate tolerance, and resilience-associated traits can provide objective, measurable phenotypes or suitable biomarkers [95] for genomic selection in beef and dairy cattle. Companies like ABS Global and STGenetics emphasize economic profitability and feed efficiency through accelerated genetic progress and improved herd management. Genomic selection based on data sources from new precision livestock technologies—that is, data-driven phenotyping strategies—can improve feed efficiency and increase sustainability in dairy cattle [96], especially by focusing on fitness, health, welfare, and milk quality [97]. Meanwhile, companies like Select Sires and Zoetis highlight multi-trait optimization to ensure that breeding decisions align with economic and environmental sustainability. Climate-smart and resource-efficient livestock systems are supported by genetic programs like ABS Global’s Beef Advantage Index, which ensures optimal beef protein supplies while reducing resource waste, and VikingGenetics’ Nordic Total Merit Index, which incorporates 90 economically important traits for multi-dimensional sustainability goals. Companies like Vytelle and ABS Pecplan provide data-driven reproductive solutions to enhance supply chain transparency and genetic health. Data-driven decision making for long-term sustainability is emphasized by companies like AltaGenetics, which use genomic data to ensure optimized breeding strategies that align with long-term sustainability goals. Digital technologies and targeted genotypes can further improve productivity and overall sustainability in beef herds [73]. Customized solutions for different production systems are offered by Brazilian genetic consortia, including CRV Brasil and Semex Brazil, ensuring adaptability to various management conditions. Companies like CRV and Alta Genetics integrate farm management insights to create customized breeding programs suited to different environments.

6. Decision Making for Beef and Dairy Sustainability: The Need for Systems-Level Food Value Chain Modeling

Agri-food chains function as multi-faceted systems that encompass a variety of firms, and various modeling approaches can help to evaluate decision making and information flows in these complex systems [98]. The adoption of digital tools for the fast capture and application of environmental and cattle performance data, even within large-scale systems, enhances productivity, efficiency, welfare, and sustainability in beef and dairy production. These findings underscore the role of data-driven decision making in modern animal breeding, enabling optimized livestock productivity while maintaining ethical and sustainable farming practices. The use of interactive web tools, herd monitoring, and modeling platforms aids in providing customized farming insights, linking sustainability with economic and environmental resilience.

Mathematical modeling (MM) is the process of constructing computer models systematically, and they have a critical role in enhancing the sustainability of beef and dairy production by enabling the optimization of production processes, resource allocation, and overall management strategies (Table 1). These models, which include linear programming, stochastic simulations, and dynamic systems modeling, help producers to make decisions by predicting outcomes under various scenarios, such as feed strategies, herd management, and the environmental impacts and operational efficiency of farming. The use of MM to facilitate research is lacking because potential users are not aware of the capabilities and benefits of MM, or they believe that model development is complex and difficult [99]. In the USA, the Integrated Farm System Model (IFSM) evaluates the economic as well as environmental impacts of dairy farm practices, while the Cornell Net Carbohydrate and Protein System (CNCPS) optimizes ruminant nutrition. Meanwhile, in Brazil, the Linear Programming Mathematical Model helps to optimize livestock–crop systems for sustainability. Brazil’s Bioeconomic Model [100] and Linear Programming Mathematical Model [101] emphasize resource allocation and livestock health management, particularly in mixed crop–livestock systems. In the United States and Brazil, mathematical models have played a crucial role in optimizing cattle production systems. Simulation modeling can serve as an effective tool for assessing the impacts of policy decisions on interorganizational fairness within European food value chains, with broad applicability across various case studies [102]. By integrating economic analysis, precision nutrition, and environmental assessment, these models provide data-driven decision-making frameworks that support risk management, sustainable farm operations, and long-term profitability.

Nutrition models based on mathematical approaches can assist in determining the biological efficiency of mature beef cattle [103]. Beef supply chain performance can be improved by using a model-driven decision support system based on system dynamics, projecting that optimizing the beef weight and carcass percentage will reduce deficits and achieve a surplus by 2028, contributing to national food self-sufficiency [104]. Several models, such as the farm optimization model FARMDYN [105] and ORFEE: A European Framework for Economic and Environmental Optimization of Ruminant Farming [106], can simulate the cost of beef cattle production and analyze its risk management and profit management [107]. The multi-objective linear programming (MOLP) model effectively balances economic and environmental goals in beef logistics networks, highlighting the importance of distances and green tax incentives for sustainability [108]. Similarly, the MINLFP model (USA) and Linear Programming Model (Brazil) incorporate multi-objective optimization to balance these goals in beef logistics networks. These models aid in improving sustainability in European beef systems by incorporating economic, environmental, and social sustainability metrics. Additionally, models like the pasture simulation model PaSim [109] and the Nordic feed evaluation system (NorFor model) [110] simulate pasture and feed interactions and optimize livestock production while assessing emissions and carbon sequestration strategies. Such approaches support the implementation of precision agriculture techniques, improving productivity and reducing the environmental footprint of cattle farming, while USA models like the Dynamic Cattle Growth Model and discounted cash flow (DCF) models evaluate profitability and cash flows in cow–calf operations. Additionally, the Brazilian Bioeconomic Model simulates the impact of tick infestations on beef systems, aiding in improved animal health and welfare. The integration of various data sources with random forest and linear regression models can contribute to accurately predicting beef production and quality at the national level, aiding in sustainable livestock production [111].

Optimizing dairy supply chains to account for environmental and social dimensions can lead to higher profits, lower economic costs, and improved social sustainability [112]. For example, the DigiMilk model [113] optimizes the dairy supply chain by integrating digital technologies to enhance traceability, resource efficiency, and sustainability. Kristensen [114] suggested that a stochastic dynamic model for dairy cow production and food intake can predict income from milk and calves, aiding in the development of a replacement model. Similarly, the random forest algorithm-based model predicts the daily milk yield under heat stress, enhancing sustainability and efficiency in the dairy sector [115]. The model proposed by Hassani et al. [116] focuses on improving the resilience and sustainability of industrial dairy farms, increasing profitability and reducing environmental degradation. Meanwhile, the Gamede model effectively explains differences in sustainability indicators between dairy farms, aiding decision making and supporting resource-efficient production [117]. Shamsuddoha et al. [118] used a system dynamics approach and simulation modeling to optimize dairy waste management and value addition, achieving sustainable outcomes for the industry and surrounding community. Additionally, the Deterministic Whole Herd Simulation model [119] and the Forage and Cattle Analysis and Planning (FORCAP) model [120] focus on evaluating dairy herd management and dual-use forage systems to maximize profitability and sustainability. In dairy farming, European models like the Nordic dairy cow model Karoline optimize feeding by simulating digestion and metabolism; the Moorepark Dairy Systems Model (MDSM) enhances herd management for profitability while Pasture-Based Herd Dynamic Milk Model [121] Simulate and predict milk production in pasture-based dairy systems; and the DairyWise model improves farm sustainability by reducing disease risks. Meanwhile, the Financial and Renewable Multi-Objective Optimization (FARMOO) model integrates economic and environmental goals. Intrafarm simulation models focus on subsystems within a farm, such as nutrition, genetics, or reproductive management, while whole-farm simulation models take a systems-level approach, integrating multiple farm components, including livestock, crops, labor, economics, and environmental factors to assess overall farm performance and sustainability. Whole-farm system models serve as effective tools in designing and assessing GHG mitigation strategies in beef and dairy cattle production, with improvements in animal productivity and fertility potentially reducing emissions. Models can optimize nutrition, milk production, and reproductive strategies in dairy farming, while, in the beef industry, they assist in managing supply chains, evaluating economic sustainability, and improving animal health and welfare. Combining multiple statistical analyses and investigating the purpose of the mathematical model is crucial in assessing their adequacy and usefulness for predictive purposes [122]. Ultimately, these models contribute to more efficient, sustainable, and profitable livestock operations.

Table 1.

Simulation and optimization models for sustainable beef and dairy systems: insights from the USA, Europe, and Brazil.

Table 1.

Simulation and optimization models for sustainable beef and dairy systems: insights from the USA, Europe, and Brazil.

| MODEL | PREDICTIVE VARIABLES AND SUSTAINABILITY OUTCOMES | REGION | FARM TYPE | METHODOLOGY AND SCOPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Models | ||||

| Farm model (FM) [123] | Evaluate dairy farm resilience by simulating production plan adjustments to adapt to external challenges and uncertainties | Europe | Dairy | Whole-Farm Optimization |

| Bioeconomic model implemented using GAMS (General Algebraic Modeling System) software [124] | Assess farmers’ adoption of precision agriculture practices by evaluating its economic and biological impacts on Greek dairy cattle farms | Europe | Dairy | Whole-Farm Optimization |

| ScotFarm [125] | Assess the financial vulnerability of Scottish dairy farms by simulating Johne’s disease and payment support impacts to optimize economic resilience and sustainability | Europe | Dairy | Whole-Farm Optimization |

| Dynamic stochastic simulation model [126] | Optimize dry period decisions in dairy herds by simulating impacts on milk production, cash flow, and emissions, accounting for farm variability | Europe | Dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

| Moorepark Dairy Systems Model (MDSM) [127] | Evaluate the financial performance of Holstein Friesian strains in different systems to identify the most profitable breeding and management strategies | Europe | Dairy | Whole-Farm Simulation |

| Dairy Farm Model [128] | Evaluate manure policy impacts on profitability, nutrient management, and emissions after milk quota abolition | Europe | Dairy | Whole-Farm Optimization |

| Mathematical programming model [129] | Optimize dairy management to meet somatic cell count targets, improving milk quality and profitability while reducing mastitis control costs | USA | Dairy | Intrafarm Optimization |

| Dynamic cattle growth model Discounted cash flow (DCF) models [130] | Evaluate profitability, risks, and cash flow in cow–calf operations by simulating cattle growth and financial performance to guide investment decisions | USA | Beef | Intrafarm Simulation; Optimization |

| Forage and Cattle Analysis and Planning (FORCAP) model [120] | Simulate and evaluate the feasibility of dual-use forage systems in cow–calf operations to optimize management for profitability and sustainability | USA | Beef; dairy | Whole-Farm Simulation |

| Bioeconomic model [100] | Simulate the economic and biological impacts of tick infestations on Brazilian beef systems to optimize management, reduce losses, and improve cattle health | Brazil | Beef | Whole-Farm Simulation |

| Bioeconomic farm model [131] | Assess the viability of conservation agriculture in Brazil’s mixed crop–livestock systems by optimizing resource use for profitability and ecological resilience | Brazil | Beef; Dairy | Whole-Farm Optimization |

| Nutritional/Farm System Management Models | ||||

| DigiMilk model [113] | Optimize the dairy supply chain by integrating digital technologies to enhance traceability, resource efficiency, and sustainability in milk production and distribution | Europe | Dairy | Whole-Farm Simulation |

| Pasture-Based Herd Dynamic Milk Model (PBHDM) [121] | Simulate and predict milk production in pasture-based dairy systems, considering herd size, pasture availability, and seasonal variations | Europe | Dairy | Whole-Farm Simulation |

| DairyWise [132] | Simulate dairy farm processes to optimize herd management, improve profitability, and reduce gastrointestinal nematode risk under varying conditions | Europe | Dairy | Whole-Farm Simulation |

| Multiscale agent-based simulation model of a dairy herd (MABSDairy) [133] | Simulate interactions between animals, herd dynamics, and management to optimize dairy herd health, productivity, and economic outcomes | USA | Dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

| Stochastic dynamic simulation modeling [134] | Evaluate reproduction and selection strategies in dairy herds to optimize performance and economic outcomes, considering farm uncertainty and variability | USA | Dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

| Multi-objective mixed-integer nonlinear fractional programming (MINLFP) model [135] | Optimize organic mixed farming by balancing profitability, resource efficiency, and sustainability through nutrient recycling | USA | Beef; Dairy | Whole-Farm Optimization |

| Farm System Management Models | ||||

| Mathematical model developed at Czech University [136] | Optimize milking parlor performance by simulating management scenarios to enhance efficiency and profitability in dairy farms | Europe | Dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

| Moorepark Dairy Systems Model (MDSM) Pasture-Based Herd Dynamic Milk Model (PBHDM) [137] | Simulate pasture-based dairy systems to optimize herd management, maximizing milk production and profitability | Europe | Dairy | Whole-Farm Simulation |

| Mathematical model created in the Czech Republic [138] | Improve operational efficiency and economic performance by simulating different milking systems under farm-specific conditions | Europe | Dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

| Farm optimization model FARMDYN [105] | Simulate and optimize farm decisions by integrating economic, environmental, and social sustainability in European beef systems | Europe | Beef; Dairy | Whole-Farm Optimization and Simulation |

| Deterministic whole herd simulation model [119] | Optimize dairy herd management by simulating milking capacity, housing, and fat quota impacts on economics, productivity, and herd dynamics | USA | Dairy | Intrafarm Optimization |

| Organic Dairy Model [139] | Optimize forage and supplement use on southeastern US organic dairy farms to enhance profitability, sustainability, and resource efficiency | USA | Dairy | Whole-Farm Optimization |

| Nutritional Models | ||||

| Stochastic and dynamic mathematical model [140] | Simulate dairy farm performance under varying management and environmental conditions to optimize decision making amid operational uncertainty | Europe | Dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

| Nordic Dairy Cow Model, Karoline [141,142] | Simulate digestion, metabolism, and nutrient use in dairy cows to optimize feeding and improve milk efficiency in Nordic systems | Europe | Dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

| Molley model [143] | Simulate metabolic processes in lactating cows to optimize feeding and improve milk production efficiency | USA | Dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

| Feed Optimization Models | ||||

| Feed pusher robot, designed and simulated using Simulink tools [144] | Automate feed pushing process to improve efficiency and reduce labor in dairy and livestock farms | Europe | Dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

| Linear program optimization (LPO) model [145] | Optimize nutritional resource allocation in a dairy herd by minimizing feed costs while meeting dietary, health, and farm constraints efficiently | Europe | Dairy | Whole-Farm Optimization |

| Linear programming (LP) and weighted goal programming (WGP) techniques [146] | Optimize dairy cow rations on organic farms by balancing feed costs, nutrition, and organic farming constraints | Europe | Dairy | Intrafarm Optimization |

| Nordic feed evaluation system (NorFor model) [110] | Optimize ruminant feeding by predicting nutrient needs and feed use to improve milk and meat production efficiency and farm profitability | Europe | Beef; Dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

| Rostock feed evaluation system [147,148] | Assess nutrient supply and utilization in ruminants by modeling digestion to optimize feeding efficiency and improve livestock productivity and sustainability | Europe | Beef; Dairy | Intrafarm Evaluation Model with Simulation Components |

| Multi-period LP feed model [149] | Optimize dairy feed selection by evaluating economic and nutritional trade-offs over time to improve profitability and efficiency | USA | Dairy | Intrafarm Optimization |

| Farm-scale diet optimization model [150] | Optimize energy and protein efficiency in dairy diets to reduce land, water use, and emissions and enhance sustainability and profitability | USA | Dairy | Whole-Farm Simulation |

| Cornell Net Carbohydrate and Protein System (CNCPS) [151,152,153,154] | Predict ruminant nutrient needs by modeling digestion and metabolism to optimize diets for improved performance and efficiency | USA | Dairy; Beef | Intrafarm Simulation |

| Ruminant Nutrition System (RNS) [155] | Predict ruminant nutrient needs, intake, and performance, optimizing diets for productivity and sustainability | USA | Dairy; Beef | Intrafarm Simulation |

| Environmental Models | ||||

| Financial and Renewable Multi-Objective Optimization (FARMOO) model [156] | Integrate economic profitability with environmental sustainability by maximizing financial returns, minimizing carbon footprint, and optimizing renewable energy in agricultural systems | Europe | Dairy | Intrafarm Optimization |

| HolosNor [157] | Assess approaches to lowering emissions intensity without compromising, and ideally improving, economic performance at the farm level | Europe | Dairy | Whole-Farm Optimization and Simulation |

| Optimization of Ruminant Farm for Economic and Environmental Assessment (Orfee) [106] | Optimize biotechnical and economic performance of mixed herds by balancing profitability and sustainability under different management strategies | Europe | Beef; Dairy | Whole-Farm Optimization |

| Pasture Simulation Model (PaSim) [109] | Simulate climate, soil, and pasture interactions to assess livestock production, emissions, and carbon sequestration under various management and climate scenarios | Europe | Beef; Dairy | Intrafarm Simulation |

| Integrated Farm System Model (IFSM) [158] | Simulate environmental and economic impacts of farm practices, focusing on sustainability metrics like emissions, nutrient cycling, and resource efficiency in grazing dairy farms | USA | Dairy | Whole-Farm Simulation and Optimization |

| N-CyCLES (Nutrient Cycling: Crops, Livestock, Environment, and Soil) [159] | Optimize nutrient cycling between crops, livestock, soil, and environment to reduce nutrient imbalances and enhance sustainability and profitability on dairy farms | USA | Dairy | Whole-Farm Optimization |

| Linear programming mathematical model [101] | Optimize livestock–crop systems by efficiently allocating resources to maximize profitability while considering environmental sustainability | Brazil | Dairy | Whole-Farm Optimization |

| Economic, Environmental, and Feed Optimization Models | ||||

| Nonlinear multi-objective diet optimization [160] | Optimize cattle feeding by minimizing costs and GHG emissions while maximizing productivity and nutritional efficiency | Europe | Beef | Intrafarm Optimization |

7. Conclusions

The global beef and dairy industries are facing significant sustainability challenges, with a pressing need for innovative solutions to balance environmental, social, and economic factors. Region-specific strategies are essential, as differences in resource availability, climate, and economic conditions influence cattle production and sustainability outcomes in countries like the USA, Brazil, and Europe. Genomic selection and multi-trait optimization have emerged as vital tools in achieving sustainable beef and dairy production by improving feed efficiency, reducing methane emissions, and promoting animal welfare without compromising productivity. Additionally, the adoption of digital technologies, data-driven decision models, and environmental monitoring systems enhances both operational efficiency and sustainability across various production environments. Mathematical models and decision support systems play a crucial role in optimizing cattle production systems, from logistics and herd management to environmental impact assessments. These models enable producers to make decisions by simulating outcomes under various scenarios, improving resource allocation and helping the industry to navigate complex challenges. To accelerate progress towards sustainability, policies should incentivize genomic selection and precision livestock technologies while integrating carbon and water footprint metrics into certification programs. Moreover, governments and industry must invest in decision support models and digital infrastructure to enable data-driven resource optimization and climate-smart livestock practices. A coordinated approach that integrates scientific advancements, technological innovation, and sustainable practices is necessary to meet the rising meat and milk demands and food security needs while reducing their environmental footprints.

Author Contributions

K.K. and M.G. conceived the idea for the review. M.P.S. performed the literature search and data analysis and drafted the manuscript. K.K. critically revised and refined the final version of the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the Artificial Intelligence for Sustainable Livestock Systems (AISLS) Lab at Texas A&M University. We extend our sincere appreciation to Texas A&M AgriLife Research for enabling this work through its research environment and collaborative infrastructure. We also thank the Department of Animal Science at Texas A&M University for their academic support, resources, and continuous encouragement throughout the development of this review. During the preparation of this review, the authors used ChatGPT 5.1 solely for paraphrasing and grammar refinement. All content was thoroughly reviewed, verified, and edited by the authors, who take full responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NASS | National Agricultural Statistics Service |

| SFA | Sustainable Food and Agriculture |

| GRSB | Global Roundtable for Sustainable Beef |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| MM | Mathematical modeling |

| CNCPS | Cornell Net Carbohydrate and Protein System |

| MOLP | Multi-objective linear programming |

| FORCAP | Forage and Cattle Analysis and Planning |

| FARMOO | Financial and Renewable Multi-Objective Optimization |

References

- Bishop, S.C.; Woolliams, J.A. Genetic approaches and technologies for improving the sustainability of livestock production. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2004, 84, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeten, J.M. Environmental management for the beef cattle industry. In Proceedings of the American Association of Bovine Practitioners Conference, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 22–25 September 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Firbank, L.G. The beef with sustainability. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 2, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, P.J.; Mottet, A.; Opio, C.I.; Falcucci, A.; Teillard, F. Environmental impacts of beef production: Review of challenges and perspectives for durability. Meat Sci. 2015, 109, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, F.P.; Meuwissen, M.P.M.; Oude Lansink, A.G.J.M. Evaluation of beef sustainability in conventional, organic, and mixed crop-beef supply chains. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Life Cycle Assessment in the Agri-Food Sector, San Francisco, CA, USA, 8–10 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lerma, L.M.; Díaz Baca, M.F.; Burkart, S. Sustainable beef labelling in Latin America and the Caribbean: Initiatives, developments, and bottlenecks. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1148973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, P.; Bréchet, T. Models for policy-making in sustainable development: The state of the art and perspectives for research. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 55, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrieciu, S.; Varga, L.; Zimmermann, N.; Chalabi, Z.; Freeman, R.; Dolan, T.; Borisoglebsky, D.; Davies, M. An inquiry into model validity when addressing complex sustainability challenges. Complexity 2022, 2022, 1193891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Per Capita Consumption of Other Meat. FAO. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/per-capita-meat-consumption-by-type-kilograms-per-year (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Mahmud, M.S.; Zahid, A.; Das, A.K.; Muzammil, M.; Khan, M.U. A systematic literature review on deep learning applications for precision cattle farming. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 187, 106313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, M.; Petrovic, V.; Gorlov, I.; Slozenkina, M.; Selionova, M.; Nikolaevna, I.; Itckovich, Y. Perspectives and challenges of global cattle and sheep meat and milk production. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 848, 012084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA-ERS. Farm Income and Wealth Statistics: U.S. and State-Level Farm Income and Wealth Statistics. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/ (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- Daniel, C.; Cross, A.; Koebnick, C.; Sinha, R. Trends in meat consumption in the USA. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 14, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henchion, M.; Moloney, A.; Hyland, J.; Zimmermann, J.; McCarthy, S. Trends for meat, milk and egg consumption for the next decades and the role played by livestock systems. Animal 2021, 15, 100287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, D.; Petre, R.; Jackson, F.; Hadarits, M.; Pogue, S.; Carlyle, C.; Bork, E.; McAllister, T. Sustainability enhancements in the beef value chain: State-of-the-art and recommendations. Animal 2017, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, D. Sustainability of the beef industry. In Encyclopedia of Food and Agricultural Ethics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castonguay, A.C.; Polasky, S.; Holden, M.H.; Herrero, M.; Mason-D’croz, D.; Godde, C.; Chang, J.; Gerber, J.; Witt, G.B.; Game, E.T.; et al. Navigating sustainability trade-offs in global beef production. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyles, J.; Calvo-Lorenzo, M. Practical developments in managing animal welfare in beef cattle: What does the future hold? J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 92, 5334–5344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eshel, G.; Shepon, A.; Shaket, T.; Cotler, B.D.; Gilutz, S.; Giddings, D.; Raymo, M.E.; Milo, R. A model for “sustainable” US beef production. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 2, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezenova, N.; Agafonova, S.; Mezenova, O.; Baidalinova, L.S.; Grimm, T. Potential of protein nutraceuticals from collagen-containing beef raw materials. Theory Pract. Meat Process. 2021, 6, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbart, J.A.; Blake, N.; Holásková, I.; Padrino, D.M.; Walker, M.; Wilson, M. Challenges in sustainable beef cattle production: A subset of needed advancements. Challenges 2023, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahmani, P.; Ponnampalam, E.; Kraft, J.; Mapiye, C.; Bermingham, E.N.; Watkins, P.J.; Proctor, S.D.; Dugan, M.E. Bioactivity and health effects of ruminant meat lipids. Meat Sci. 2020, 165, 108114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, N.; DeVuyst, E.; Brorsen, B.; Lusk, J. Yield and quality grade outcomes influenced by molecular breeding values. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 93, 2045–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouillard, J. Current situation and future trends for beef production in the United States. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 31, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocquette, J.; Ellies-Oury, M.; Lherm, M.; Pineau, C.; Deblitz, C.; Farmer, L. Current situation and future prospects for beef production in Europe. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 31, 1017–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocquette, J.; Chatellier, V. Prospects for the European beef sector over the next 30 years. Anim. Front. 2011, 1, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagranda, Y.G.; Wiśniewska-Paluszak, J.; Paluszak, G.; Mores, G.d.V.; Moro, L.D.; Malafaia, G.C.; de Azevedo, D.B.; Zhang, D. Emergent research themes on sustainability in the Brazilian beef cattle industry. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, D.; Oliveira, T.; Oliveira, J. Sustainability in the Brazilian pampa biome: A composite index to integrate beef production, social equity, and ecosystem conservation. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 98, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, P.; Gibbs, H.; Vale, R.; Christie, M.; Florence, E.; Munger, J.; Sabaini, D. The expansion of intensive beef farming to the Brazilian Amazon. Glob. Environ. Change 2019, 57, 101922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martha, G.; Alves, E.; Contini, E. Land-saving approaches and beef production growth in Brazil. Agric. Syst. 2012, 110, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruviaro, C.; Gianezini, M.; Barcellos, J.; Oliveira, T.; Dewes, H. Sustainability and market orientation in the Brazilian beef chain. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2014, 4, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. Muscle biology and meat quality—Challenges, innovations, and sustainability. Anim. Agric. 2020, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Place, S.; Miller, M.; Amy, M.S. Beef production: Human and environmental impacts. Nutr. Today 2020, 55, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, R.; Henchion, M.; Hyland, J.J.; Gutiérrez, J.A. Creating a rainbow for sustainability: The case of sustainable beef. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vries, M.; Boer, I. Comparing environmental impacts for livestock products: A review of life cycle assessments. Livest. Sci. 2010, 128, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stackhouse-Lawson, K.R.; Thompson, L.R. Climate change and the beef industry: A rapid expansion. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100, 32–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasmus, L.; van Marle-Köster, E. Moving towards sustainable breeding objectives and cow welfare in dairy production: A South African perspective. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2021, 53, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, L.; Beauchemin, K. A holistic perspective of the societal relevance of beef production and its impacts on climate change. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 101, skad024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotz, C.; Asem-Hiablie, S.; Dillon, J.; Bonifacio, H. Cradle-to-farm gate environmental footprints of beef cattle production in Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 93, 2509–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotz, C.; Isenberg, B.; Stackhouse-Lawson, K.; Pollak, E. A simulation-based approach for evaluating environmental footprints of beef production systems. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 5427–5437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pishgar-Komleh, S.H.; Beldman, A. Literature Review of Beef Production Systems in Europe. Wageningen Livestock Research Report. 2022, p. 39. Available online: https://saiplatform.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/19012022-beef-literature-review.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- Desjardins, R.; Worth, D.; Vergé, X.; Maxime, D.; Dyer, J.; Cerkowniak, D. Carbon footprint of beef cattle. Sustainability 2012, 4, 3279–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtz, M.; Steyn, Y.; Marle-Köster, E.; Theron, H. Improved production efficiency in cattle to reduce carbon footprint. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 42, 450–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusack, D.; Kazanski, C.; Hedgpeth, A.; Chow, K.; Cordeiro, A.L.; Karpman, J.; Ryals, R. Reducing climate impacts of beef production: A synthesis of life cycle assessments across management systems. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 1721–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Kreuter, U.; Davis, C.; Cheye, S. Climate impacts of alternative beef production systems depend on the functional unit used. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2321245121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, B.J.; Lewin, H.A.; Goddard, M. The future of livestock breeding: Genomic selection for efficiency, reduced emissions intensity, and adaptation. Trends Genet. 2013, 29, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragaglio, A.; Braghieri, A.; Pacelli, C.; Napolitano, F. Environmental impacts of beef as corrected for the provision of ecosystem services. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipp, D.; Putman, B.; Thoma, G. ASAS-CSAS Annual Meeting Symposium on Water Use Efficiency at the Forage-Animal Interface: Life cycle assessment of forage-based livestock production systems. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 1865–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilahyane, A.; Ghimire, R.; Acharya, B.; Schipanski, M.; West, C.; Obour, A. Overcoming agricultural sustainability challenges in water-limited environments through soil health and water conservation: Insights from the Ogallala Aquifer Region, USA. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2023, 21, 2211484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridoutt, B.; Sanguansri, P.; Harper, G. Comparing carbon and water footprints for beef cattle production in Southern Australia. Sustainability 2011, 3, 2443–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, B.; Murphy, B.; Cowie, A. Sustainable Land Management for Environmental Benefits and Food Security; A Synthesis Report for the GEF; Global Environment Facility: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; p. 127. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, B.; Briggs, K.; Nydam, D. Dairy production sustainability through a one-health lens. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2022, 261, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.T.; Briggs, K.R.; Eicker, S.; Overton, M.; Nydam, D.V. Herd turnover rate reexamined: A tool for improving profitability, welfare, and sustainability. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2023, 84, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaskó, B. An analysis of the Hungarian dairy industry in the light of sustainability. Reg. Bus. Stud. 2011, 3, 699–711. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, A. Sustainable dairy breeding: Working within the US national evaluation system. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesogan, A.; Dahl, G. MILK Symposium introduction: Dairy production in developing countries. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 9677–9680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greblikaite, J.; Astrovienė, J.; Rakštys, R. Analysis of sustainable dairy farming practices in the EU and foreign countries. Rural Dev. 2019, 10, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauly, M.; Bollwein, H.; Breves, G.; Brügemann, K.; Dänicke, S.; Daş, G.; Demeler, J.; Hansen, H.; Isselstein, J.; König, S.; et al. Future consequences and challenges for dairy cow production systems arising from climate change in Central Europe—A review. Animal 2013, 7, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.; Barraj, L.; Toth, L.; Harkness, L.; Bolster, D. Daily intake of dairy products in Brazil and contributions to nutrient intakes: A cross-sectional study. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 19, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, A.; Alves, E.; Melo, F.; Barroso, I.; Soares, A.; Imazaki, P.; Medeiros, E. Overview of the milk production chain in Brazil: Development and perspectives. Rev. Cient. Multidiscip. Núcl. Conhecimento 2023, 1, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, R.; Fregonesi, J.A.; Vieira, A.D. Sustainable dairy cattle production in Southern Brazil: A proposal for engaging consumers and producers to develop local policies and practices. In Know Your Food; Wageningen Academic: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Hötzel, M.; Longo, C.; Balcão, L. A survey of management practices that influence production and welfare of dairy cattle on family farms in southern Brazil. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankuti, F.; Prizon, R.; Damasceno, J.; De Brito, M.; Pozza, M.; Lima, P. Farmers’ actions toward sustainability: A typology of dairy farms according to sustainability indicators. Anim. Int. J. Anim. Biosci 2020, 14, s417–s423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borawski, P.; Kalinowska, B.; Mickiewicz, B.; Parzonko, A.; Klepacki, B. Changes in the milk market in the United States on the background of the European Union and the world. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, XXIV, 1010–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Dairy. Environmental Sustainability. U.S. Dairy. Available online: https://www.usdairy.com/sustainability/environmental-sustainability (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- Innovation Center for U.S. Dairy. 2021–2022 U.S. Dairy Sustainability Report. Available online: https://usdairyexcellence.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/en_2021-Sustainability.pdf?_t=1742571167/ (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Berry, D.P. Invited review: Beef-on-dairy—The generation of crossbred beef × dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 3789–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hristov, A.; Ott, T.; Tricarico, J.; Rotz, A.; Waghorn, G.; Adesogan, A.; Dijkstra, J.; Montes, F.; Oh, J.; Kebreab, E.; et al. Special topics—Mitigation of methane and nitrous oxide emissions from animal operations: III. A review of animal management mitigation options. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 5095–5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Hermansen, J.; Mogensen, L. Environmental consequences of different beef production systems in the EU. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 756–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, E.; Mullan, S. Advancing a “good life” for farm animals: Development of resource tier frameworks for on-farm assessment of positive welfare for beef cattle, broiler chicken and pigs. Animals 2022, 12, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compiani, R. Strategies to Optimize the Productive Performance of Beef Cattle. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Veterinary Sciences for Animal Health, Animal Production and Food Safety, University of Milan, Milan, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulina, G.; Acciaro, M.; Atzori, A.S.; Battacone, G.; Crovetto, G.M.; Mele, M.; Pirlo, G.; Rassu, S.P. Animal board invited review—Beef for future: Technologies for a sustainable and profitable beef industry. Animal 2021, 15, 100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, P. Review: An overview of beef production from pasture and feedlot globally, as demand for beef and the need for sustainable practices increase. Animal 2021, 15, 100295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, T.; Basarab, J.; Guan, L. 177 Strategies to improve the efficiency of beef cattle production. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asikin, Z.; Baker, D.; Villano, R.; Daryanto, A. Business models and innovation in the Indonesian smallholder beef value chain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, K.J.; Newton, P.; Gibbs, H.K.; McConnel, I.; Ehrmann, J. Pursuing sustainability through multi-stakeholder collaboration: A description of the governance, actions, and perceived impacts of the roundtables for sustainable beef. World Dev. 2019, 121, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanty, A.; Puspitasari, N.; Purwaningsih, R.; Hazazi, H. Prioritization of an indicator for measuring sustainable performance in the food supply chain: Case of beef supply chain. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Macao, China, 15–18 December 2019; pp. 881–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; von Keyserlingk, M.; Magliocco, S.; Weary, D. Employee management and animal care: A comparative ethnography of two large-scale dairy farms in China. Animals 2021, 11, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio-Sadus, A.; Griffiths, S. Marketing strategies for enhancing safety culture. Saf. Sci. 2004, 42, 601–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotz, C.; Asem-Hiablie, S.; Place, S.; Thoma, G. Environmental footprints of beef cattle production in the United States. Agric. Syst. 2019, 169, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.; Brady, M.; Capper, J.; McNamara, J.; Johnson, K. Cow–calf reproductive, genetic, and nutritional management to improve the sustainability of whole beef production systems. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 93, 3197–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Place, S.; McCabe, C.; Mitloehner, F. Symposium review: Defining a pathway to climate neutrality for US dairy cattle production. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 8558–8568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capper, J. The environmental impact of beef production in the United States: 1977 compared with 2007. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 89, 4249–4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, S.; Basarab, J.; Guan, L.; McAllister, T. Strategies to improve the efficiency of beef cattle production. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 101, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hietala, P.; Juga, J. Impact of including growth, carcass and feed efficiency traits in the breeding goal for combined milk and beef production systems. Animal 2017, 11, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, M.; Tzimiropoulos, G. Novel monitoring systems to obtain dairy cattle phenotypes associated with sustainable production. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 2, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, L.; Bédère, N.; Douhard, F.; Oliveira, H.; Arnal, M.; Peñagaricano, F.; Schinckel, A.; Baes, C.; Miglior, F. Review: Genetic selection of high-yielding dairy cattle toward sustainable farming systems in a rapidly changing world. Anim. Int. J. Anim. Biosci 2021, 15, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, Y.D.; Pszczoła, M.; Soyeurt, H.; Wall, E.; Lassen, J. Invited review: Phenotypes to genetically reduce greenhouse gas emissions in dairying. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 855–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, Y.; Veerkamp, R.; Jong, G.; Aldridge, M. Selective breeding as a mitigation tool for methane emissions from dairy cattle. Animal 2021, 15, 100294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renand, G.; Vinet, A.; Decruyenaere, V.; Maupetit, D.; Dozias, D. Methane and carbon dioxide emission of beef heifers in relation with growth and feed efficiency. Animals 2019, 9, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzanilla-Pech, C.; Løvendahl, P.; Gordo, D.; Difford, G.; Pryce, J.; Schenkel, F.; Wegmann, S.; Miglior, F.; Chud, T.; Moate, P.; et al. Breeding for reduced methane emission and feed-efficient Holstein cows: An international response. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 8983–9001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.; Jauernik, G. Selecting the “sustainable” cow using a customized breeding index: Case study on a commercial UK dairy herd. Agriculture 2023, 13, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger-Danner, C.; Cole, J.; Pryce, J.; Gengler, N.; Heringstad, B.; Bradley, A.; Stock, K. Invited review: Overview of new traits and phenotyping strategies in dairy cattle with a focus on functional traits. Animal 2014, 9, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]