Abstract

Geothermal energy is a crucial component of climate adaptation and sustainability transitions, as it provides a dependable, low-carbon source of baseload power that can accelerate sustainable energy transitions and enhance climate resilience. Yet, in East Africa—one of the world’s most promising geothermal regions, with the East African Rift—a unique climate-energy opportunity zone—the harnessing of geothermal power remains slow and uneven. This study examines the contextual conditions that facilitate the successful and sustainable development of geothermal power in the region. Drawing on semi-structured interviews with 17 experienced professionals who have worked extensively on geothermal projects across East Africa, the analysis identifies how technical, institutional, managerial, and relational circumstances interact to shape outcomes. The findings indicate an interdependent configuration of success conditions, with structural, institutional, managerial, and meta-conditions jointly influencing project trajectories rather than operating in isolation. The most frequently emphasised enablers were resource confirmation and technical design, leadership and team competence, long-term stakeholder commitment, professional project management and control, and collaboration across institutions and communities. A co-occurrence analysis reinforces these insights by showing strong patterns of overlap between core domains—particularly between structural and managerial factors and between managerial and meta-conditions, highlighting the mediating role of managerial capability in translating contextual conditions into operational performance. Together, these interrelated circumstances form a system in which structural and institutional foundations create the enabling context, managerial capabilities operationalise this context under uncertainty, and meta-conditions sustain cooperation, learning, and adaptation over time. The study contributes to sustainability research by providing a context-sensitive interpretation of how project success conditions manifest in geothermal development under climate transition pressures, and it offers practical guidance for policymakers and partners working to advance SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), and SDG 13 (Climate Action) in Africa.

1. Introduction

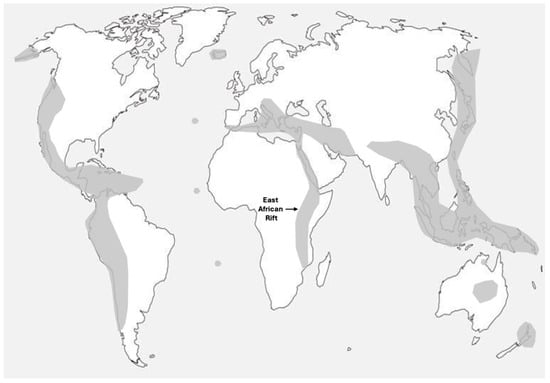

Geothermal power development is widely recognised as a promising pathway for achieving low-carbon energy transitions. Figure 1 illustrates the global geothermal hotspots and indicates how geothermal energy can serve as a baseload renewable energy source, supporting climate adaptation through enhanced energy security.

Figure 1.

Geothermal hot spots around the world, indicated with shaded areas. Adapted from [1].

The potential of geothermal energy is strong in East Africa, along the East African Rift System [2,3,4]. Geothermal offers baseload power capacity, minimal carbon emissions, and long-term reliability—making it well-suited to address energy poverty and climate mitigation goals simultaneously. This is the case for countries along the Great East African Rift, stretching over 6500 km from the Middle East to Mozambique. This is among the world’s most promising geothermal regions, characterised by high heat flow, volcanic activity, and extensive hydrothermal features. However, despite strong potential and rising energy demand, geothermal development in many East African countries remains slow and uneven, with projects often facing long lead times, early-stage uncertainty, and institutional fragmentation [5,6,7]. Kenya remains a regional leader; most other countries are at early stages of exploration or pre-feasibility. A recent study indicates a commitment by Kenyan energy companies to developing new technologies, markets and policies towards sustainable energy solutions [8]. Numerous barriers—financial, institutional, legal, and political—have, however, slowed progress along the East African Rift System. In parallel, project-based development initiatives in Africa have long struggled with underperformance. Studies have shown that for public policy reform projects, funded by donors such as the World Bank, half of the projects fail to achieve their intended impacts in terms of societal transformation [9,10]. Several factors contribute to this underperformance in Africa, including structural issues such as political, environmental, and economic challenges, as well as institutional problems such as corruption, insufficient political support or governance, and principal-agent problems. Additionally, there are direct problems stemming from a lack of effective project management practices [9,11].

The development of large energy projects cannot be fully understood through technical or financial analysis alone. These are not only energy projects but also complex, multi-stakeholder, long-duration undertakings embedded in shifting political and institutional environments [12]. Their success depends not only on the quality of the resource or the presence of funding, but also on regulatory clarity, competent leadership, effective coordination, and long-term stakeholder alignment [13,14]. The project-specific dimensions of geothermal development remain relatively underexplored in the academic literature.

Geothermal development is deeply relevant to sustainable development and climate adaptation. It supports Sustainable Development Goal 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) by providing a renewable and reliable energy source and contributes to SDG 13 (Climate Action) by reducing dependence on fossil fuels. Moreover, the process of geothermal development—which often involves international cooperation, capacity building, and long-term public investment—can foster resilience and sustainable economic growth [15]. In this way, geothermal projects serve not only as energy solutions but also as platforms for broader sustainable infrastructure development.

Within the field of project studies, there is a growing interest in the interaction between project success and contextual conditions [16,17]. Recent work has emphasised that project outcomes cannot be fully explained by project management competence alone, and that institutional, political, and structural enablers must be accounted for [18]. In the context of development and infrastructure projects, this perspective is particularly relevant. It raises questions about which conditions truly matter—and under what circumstances they enable or constrain success.

A geothermal power project, as defined in this study, is a long-duration infrastructure initiative aimed at producing electricity (and sometimes heat) by tapping into deep geothermal reservoirs through drilling, exploration, plant construction, and grid connection. Such projects are typically carried out in phases and involve actors from the public, private, and donor sectors. To explore this topic, this study is based on semi-structured interviews with 17 senior professionals who have extensive direct experience in geothermal development in East Africa. The study applies a structured qualitative methodology informed by Ika and Pinto’s typology [19], which distinguishes between structural, institutional, managerial, and meta-contextual conditions for project success. This framework enables a grounded and comparative understanding of the contextual enablers that shape geothermal development outcomes in the region. While the project management success literature is mature, its application to geothermal development remains scarce. This study, therefore, provides contextual innovation rather than methodological novelty.

While prior work on geothermal development has focused predominantly on technical risk and resource characteristics, a clear gap exists in the literature regarding the management and sustainability conditions that enable such projects to succeed, not least in the East African context. The research is thus guided by the following question: What are the necessary contextual conditions for the successful development of geothermal power projects in East Africa, as perceived by experienced professionals?

The findings are intended to support both scholarly inquiry and practical decision-making at the intersection of project governance, clean energy transitions, and sustainable development. They also offer insight into how success conditions in complex energy infrastructure projects may vary—and what this implies for adaptation-oriented investment and planning under climate constraints.

2. Theoretical Framing

2.1. Expanding the Concept of Project Success

In project management literature, the definition of success has evolved significantly over the past decades. Early frameworks emphasised the so-called “iron triangle” of time, cost, and scope [20], but these classical criteria have been widely criticised for their inability to reflect broader project outcomes or long-term value. The iron triangle is based on assumptions about objective baselines and fixed project plans—assumptions that are increasingly being challenged in complex, uncertain, or dynamic project environments.

Subsequent models introduced the distinction between project success and project management success [21,22,23], with the former focusing on strategic and stakeholder-oriented outcomes, and the latter on efficiency in execution. Shenhar et al. proposed a four-dimensional model of project success—efficiency, impact on customers, business success, and future preparedness—which emphasises that success evolves over time [24]. Overall, the perception of project success has hence evolved to include not only the traditional measures of project management success but also a broader perspective, including the needs of stakeholders and the organisation as a whole and understanding the project context, strong project commitment, stakeholder engagement, alignment of expectations and rich communication, realistic and well-defined targets [25,26].

Building on this trajectory, Silvius and others have called for a broader understanding of project success grounded in sustainability [27]. Other studies have elaborated how sustainability reframes project success from short-term efficiency toward long-term value creation, stakeholder legitimacy, ethical considerations and contribution to societal goals [28,29,30,31]. Projects are now increasingly assessed in terms of their contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and their long-term systemic effects.

Sustainable project success requires a fundamental shift toward managing the broader social, environmental, and economic value that a project creates. As Silvius et al. [32] argue, integrating sustainability makes the underlying complexity of projects more explicit, particularly in relation to stakeholder interests, long-term impacts, and contextual conditions. From this perspective, success is inseparable from a project’s contribution to sustainable adaptation and its capacity to address climate-related challenges over time.

2.2. Success Factors in Renewable Energy Projects

In the case of renewable energy projects, project success has been linked to a variety of external and internal factors. Some studies [33,34] categorise success factors into areas including leadership and governance, risk management, access to finance, community acceptance, and regulatory clarity. These studies typically apply a critical success factor (CSF) lens, seeking to identify conditions that distinguish successful from unsuccessful projects.

While the CSF approach has been influential, it has also been critiqued for oversimplifying the project environment and underestimating contextual complexity [16,24]. This is especially true for energy megaprojects in emerging economies, where systemic conditions such as political stability, institutional maturity, and cross-sector coordination play a crucial role.

Silvius [27] provides a useful lens; sustainable project success must be understood across multiple time horizons—including the resource, project, deliverable, and benefits life cycles. Furthermore, and in line with Hauschild’s notion of absolute sustainability [35], project success includes alignment with ecological boundaries and sustainable development goals, requiring that projects generate value while operating within the environmental limits of the systems on which they depend. Project outcomes contribute not only to short-term efficiency but also to long-term resilience and sustainability.

2.3. Geothermal Power Projects as a Complex Project Type

Among renewable energy technologies, geothermal power projects present a distinctive set of challenges. As outlined in the World Bank Geothermal Handbook [2], the development process spans multiple high-risk phases: surface exploration, test drilling, reservoir modelling, field development, plant construction, and grid integration. Each stage carries different risk profiles, financing needs, and technical requirements. Unlike solar or wind projects, the viability of geothermal projects can only be confirmed through costly and uncertain drilling campaigns, which creates a front-loaded risk curve and complicates investment decisions [5,36].

Geothermal projects typically require substantial capital investments, lengthy development timelines (often spanning a decade or more), and coordination among multiple stakeholders, including government ministries, national utilities, multilateral donors, and private sector developers. They also tend to involve Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs), Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) structures, or public-private partnerships (PPPs), further increasing governance complexity [37].

While geothermal energy shares characteristics with other large-scale renewable infrastructure projects (such as hydropower or wind), its specific risk profile, technical dependency on subsurface conditions, and long-term capacity-building needs justify its treatment as a distinct project type for analytical purposes. A small body of literature has begun to examine success factors specific to geothermal investments, highlighting the importance of early-stage public support, technical expertise, enabling regulations, and long-term institutional stability [2,37,38,39,40,41].

2.4. Contextual Conditions and the “Circumstances for Success” Model

A growing body of project management research has moved beyond traditional models of project success to emphasise the role of contextual conditions—political, institutional, cultural, and managerial—in shaping outcomes [17,42,43]. Recent contributions have emphasised the need to interpret project success not only in terms of internal performance, but also in terms of its long-term contribution to sustainable development [18,27]. These perspectives are especially important in large-scale infrastructure and development projects, where outcomes are not solely a function of planning tools or delivery models, but of how projects interact with their environments.

This research adopts and adapts the “circumstances for success” model proposed by Ika and Pinto [19], which offers a multi-layered framework for understanding how context shapes project outcomes. However, while Ika and Pinto provide a particularly explicit articulation of ‘circumstances for success’, the broader project management literature has long questioned universal success criteria and emphasised contextual, institutional, and systemic conditions shaping project outcomes (e.g., Refs. [42,43,44]).

Based on a review of complex development projects and their systemic drivers of success or failure, the chosen model identifies three primary contextual domains:

- Structural conditions: the physical, political, environmental, economic, geographical, and socio-cultural environment in which the project is embedded. These include, e.g., macro-level constraints and enablers such as national energy demand, geography, or conflict risk. The availability of natural resources would also be included here.

- Institutional conditions: the legal, regulatory, and governance frameworks surrounding the project, including the capabilities and behaviour of involved organisations, the presence or absence of corruption, and the clarity of decision-making roles.

- Managerial conditions: the internal organisation of projects— how they are planned, implemented, monitored, and adapted—including leadership agency, team competence, coordination mechanisms, and benefit realisation practices.

In addition to these three domains, the model identifies a fourth analytical dimension, comprising meta-conditions, which are cross-cutting enablers that influence how structural, institutional, and managerial factors are implemented in practice. These are:

- Commitment—the degree to which key stakeholders demonstrate the project value and support and sustain the project vision over time.

- Collaboration—the quality and effectiveness of multi-stakeholder collaboration across institutional and organisational boundaries.

- Alignment—the extent to which stakeholder interests, project goals, and planning assumptions are coherent and mutually reinforcing.

- Adaptation—the ability to monitor the project, revise assumptions and delivery processes in response to changing contexts and provide support and guidance.

These meta-conditions are not separate domains but rather dynamic, interrelated enablers that shape the practical feasibility of project development in complex environments. Recent empirical validation reinforces the applicability of this framework across different project types [45].

The framework is particularly relevant for geothermal energy development, which is characterised by deep technical uncertainty, phased risk exposure, and strong institutional interdependence. It provides a useful structure for examining how different contextual conditions influence project outcomes and how long-term success depends on their alignment rather than on sound engineering or financial models alone. For an exploratory qualitative study, this simplicity and contextual orientation make the framework well suited for structuring expert interviews and subsequent thematic analysis.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Rationale

The study employs a qualitative research design to explore contextual success conditions in geothermal power projects in East Africa. Recognising that conventional project management models may understate the institutional and socio-political complexity of infrastructure development in emerging economies, this study focused on expert knowledge derived from long-term involvement in geothermal project execution, planning, and governance. The “Circumstances for Success” model was selected as a guiding analytical framework.

3.2. Sampling and Interviewee Selection

A purposive sampling strategy was employed to ensure diversity in terms of background, geographical perspective, and professional experience. Seventeen experts were selected based on their extensive engagement with geothermal power projects in East Africa, including Kenya, Ethiopia and Tanzania. Participants included consultants, engineers, project managers, academics, and executive leaders. Most interviewees had over 15 years of experience in geothermal energy, with several exceeding 30 years. All of them had a direct or indirect connection to the GRÓ Centre for Capacity Development in Iceland, formerly known as the UNU Geothermal Training Programme. Table 1 summarises the anonymised characteristics of the sample, including their national background, training, and role in geothermal project development. All interviews were conducted with informed consent, and identifying information has been anonymised. No interviewees or their institutions are named.

Table 1.

Background and experience of interviewees.

3.3. Interview Protocol and Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted using a six-part interview protocol designed to elicit both general insights about geothermal project success and Africa-specific challenges. The overall objective was to explore how experienced practitioners understand the conditions under which geothermal power projects succeed or fail in East Africa, with particular attention to the interaction between technical, institutional, managerial, and contextual factors. The interview protocol was therefore designed to elicit both broad and context-specific insights, progressing from general success conditions in geothermal development to more regionally grounded project management challenges. This structure reflects the study’s interest in understanding success not as a single outcome or factor, but as a process shaped by multiple, interrelated conditions across different analytical levels. The protocol covered:

- Global success factors for geothermal development.

- Current status of geothermal development in Africa.

- Boundary conditions and challenges for geothermal industry development in Africa.

- Critical success factors for project management in African geothermal contexts.

- Specific project management differences in Africa vs. other regions.

- Final comments or observations.

Interviews were conducted between January 2023 and May 2023 and recorded with the participants’ consent.

3.4. Thematic Coding and Analytical Framework

The analysis proceeded in several steps. All interviews were transcribed and thematically analysed using the predefined thematic structure derived from the theoretical framework, ensuring consistency across interviews. The four primary domains were:

- Structural (S)—project characteristics, resource quality, technical and economic feasibility.

- Institutional (I)—governance, legal frameworks, financing, stakeholder environment.

- Managerial (M)—team capability, leadership, planning and control.

- Meta-contextual (Meta)—higher-order reflections on experience, knowledge transfer, and system maturity.

Meta-conditions were analysed as a distinct but cross-cutting domain. Each transcript was reviewed independently by the principal author. All interviews were transcribed and prepared for qualitative analysis.

The coding was iteratively reviewed and refined to ensure that categories accurately reflected the empirical material and that overlaps or ambiguities were resolved. Coded material was synthesised across interviews to identify recurring patterns and emphases within and across the structural, institutional, managerial, and meta-level categories. Finally, co-occurrence patterns between themes were examined to explore how different success conditions were discussed in relation to one another, providing insight into their interaction rather than their isolated presence.

Direct quotations were extracted for illustrative use and stored in a cross-referenced thematic matrix. The thematic coding and analysis were conducted manually in a spreadsheet, based on structured templates developed during the initial stage of data processing.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

This study involved interviews with adult professionals about their work-related experience in geothermal project development. In accordance with the ethical guidelines of Reykjavik University and the Code of Conduct of the Icelandic Universities’ Ethics Committee, the research was deemed low-risk and therefore did not require formal approval from an institutional ethics board. All participants were informed about the purpose of the study, participated voluntarily, and provided their informed consent. Interviews were anonymised, and no personal or sensitive information was collected or reported.

4. Results

4.1. Experts Interviewed

The 17 interviewees are international professionals with global experience in geothermal power projects. Most of them have been engaged with geothermal projects in East Africa for over a decade, in both technical and leadership roles. They come from five countries, and their experience working in geothermal power projects ranges from 8 to 45 years, with an average of 23 years. Table 1 gives an overview of their professional background and experience.

4.2. Results of Thematic Analysis

This section presents the results of the thematic analysis, structured around the typology of success conditions. The framework distinguishes between structural, institutional, managerial, and meta-contextual factors. Thematic coding of the seventeen interviews produced 191 distinct coded statements, distributed across four domains. While the main categories were drawn from the Ika and Pinto “Circumstances for Success” model, the sub-categories emerged inductively through a close reading and iterative coding of the interview data. This process involved identifying recurring patterns across transcripts, refining and consolidating themes in dialogue with the theoretical model, and validating the final sub-categories through systematic cross-case comparison.

A thematic summary is presented in Table 2, showing the distribution of themes across interviews.

Table 2.

Distribution of themes across interviews. S = Structural conditions (S1 Resource characteristics and confirmation; S2 Capital intensity and financing structure; S3 Context-driven success criteria); I = Institutional conditions (I1 Political and institutional stability; I2 Institutional clarity and role allocation; I3 Legal frameworks and permitting processes; I4 Early-stage financing mechanisms; I5 Context-specific institutional constraints); M = Managerial conditions (M1 Leadership and team competence; M2 Professional project management; M3 Adaptive and realistic planning; M4 Project controls and monitoring; M5 Stakeholder-facing project execution); ME = Meta-conditions (ME1 Stakeholder and leadership commitment; ME2 Multi-stakeholder collaboration; ME3 Role clarity and strategic coherence; ME4 Adaptive learning and iterative planning).

The analysis reveals a relatively balanced pattern, with Managerial conditions accounting for 32 per cent of all coded statements, Institutional conditions at 25 per cent, Structural conditions at 24 per cent, and Meta-conditions at 19 per cent. Within the domains, several sub-categories stand out for their frequency and interpretive importance. The most frequently referenced was Resource characteristics, confirmation and technical design (24 counts), followed by M1—Leadership and team competence (22 counts), M2—Professional project management and control (21), ME1—Commitment (17 counts), S2—Capital intensity and financing structure (14), and ME2—Collaboration (12). Other frequently mentioned sub-categories are I5—Context-specific institutional constraints (12), I4—Early financing mechanisms (12), I3—Legal and regulatory frameworks (11), Adaptive and realistic planning (11), M4—Stakeholder engagement and external coordination (8), ME3—Alignment and adaption (8) and S3—Context driven success criteria (7).

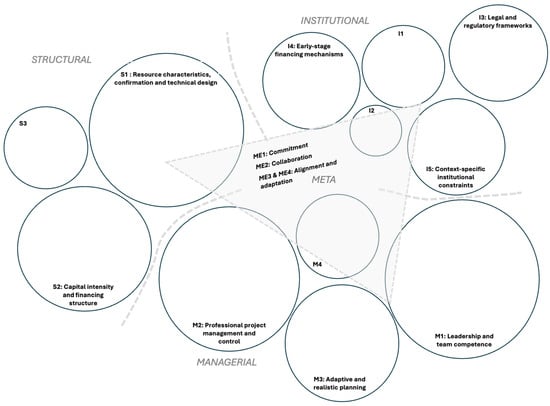

Figure 2 illustrates a visualisation of the most important conditions for success, as identified through the expert interviews.

Figure 2.

Visualisation of the most important conditions for success for sustainable Geothermal Power Development in East Africa.

Figure 2 presents a bubble diagram in which the size of each circle represents the relative prominence of a theme, based on the frequency with which it was mentioned across the interviews. The meta-conditions are depicted as a central triangular element, indicating their cross-cutting role across the structural, institutional, and managerial domains.

This overview reveals that across the dataset, respondents framed success not as a set of isolated factors, but as a combination of interlocking circumstances. Structural and institutional foundations establish the enabling context; managerial capabilities convert that context into tangible progress; and meta-conditions such as commitment and collaboration integrate the system over time. This integrated pattern provided the basis for the four domain narratives that follow. The main results are discussed below, with reference to illustrative quotations where appropriate.

4.3. Structural Conditions

Structural conditions define the external setting in which geothermal projects are conceived and executed. Four interrelated sub-themes were identified.

4.3.1. S1 Resource Characteristics, Confirmation and Technical Design

In general, the participants considered the nature of the geothermal resource to be the ultimate determinant of project feasibility. Reliable confirmation of reservoir size and temperature was considered essential for securing financing and maintaining confidence among developers. As R3 stated, “One of the most important issues has been the exploration stage, to prove that there is sufficient steam.” Another added (R10), “No reservoir, no project.” “Professional geothermal surface surveys, exploration drilling and solid reservoir modelling” are some of the preconditions for success according to R14. Some experts emphasised the importance of aligning project scale with resource size, design feasibility, and long-term sustainability. Large geothermal plants may not be suitable; smaller, modular units may be better suited to local contexts.

4.3.2. S2 Capital Intensity and Financing Structure

Respondents highlighted that the geothermal projects are capital-intensive in the early stages and involve significant risk. Financing is a major barrier at the early stages. A thorough assessment of project feasibility and due diligence is crucial to securing financing. This can be a challenge, as R8 pointed out: “Problems and risks that influence the financing can be largely attributed to the unpredictable behaviour of the geothermal reservoir.” However, if the resource has been proven, financing should not be a problem, as pointed out by more than one expert.

4.3.3. S3 Context-Driven Success Criteria

Several experts pointed out that there needs to be a market for the energy, as stated by R1, “Is there a market, is there a demand for the power? Demand has been assumed to be rising in the area, as R4 stated: “There is a huge energy shortage in East Africa, with only 10% of the population having access to safe electricity.” Another perspective was provided by R2: “Electricity demand has not grown quite as much as expected, not like in Europe.” Currency aspects can also be crucial; “Is there a shortage of currency, and how will we deal with that? (R1) Some experts stressed the importance of looking at the perspectives of different stakeholders when assessing success and focusing on economic aspects, people’s well-being and environmental issues.

4.4. Institutional Conditions

Institutional conditions refer to the organisational and regulatory arrangements through which geothermal projects are financed, governed and coordinated. Five institutional sub-conditions were identified.

4.4.1. I1 Political and Institutional Stability

A primary theme was political and institutional stability, which was considered a key to success, but often a problem in this part of the world. Issues mentioned under this subheading included country risk, corruption, and political stability, as well as community issues, religious or political conflicts. As R1 put it: “Is there corruption in the country? What about political stability?”

4.4.2. I2 Institutional Clarity and Role Allocation

A second recurring issue was institutional fragmentation and unclear responsibilities. There is a need for well-defined and coordinated roles across ministries, utilities, geological agencies, and regulators. Kenya was cited as a case of relative success where entities such as KenGen and GDC operate under coherent institutional mandates. In contrast, other countries struggle with overlap and inefficiency. As R6 explained: “Everything seems to take longer than expected, but ‘this is Africa’.”

4.4.3. I3 Legal and Regulatory Frameworks

Regulatory frameworks drew critical attention. While geothermal laws exist in some countries, several interviewees noted that practical implementation is often slow or inconsistent. In fact, lack of geothermal-specific regulation was frequently mentioned as a major obstacle to project initiation in some countries. Permitting procedures may be opaque or poorly enforced, creating uncertainty for investors and developers. A related observation is how easy or difficult it is for distant contractors to operate in the country: “What sort of incentives for developers? For instance, what about Visa for workers? This is very important for developers.” (R1)

4.4.4. I4 Early-Stage Financing Mechanisms

The capital-intensive and high-risk early phases of geothermal development were repeatedly cited as the main institutional bottleneck. Interviewees noted that private investors seldom finance exploration and that public-sector risk-mitigation instruments remain limited. R8 stated: “Financing the first steps of the development is one of the thresholds in developing geothermal power.” R3 emphasised, “The private sector is typically not involved in exploration due to high risks and lack of instruments; the governments must step in.” Similarly, R15 stated, “Government support is essential, especially in financing the riskiest stage of geothermal development, this is the resource confirmation.”

4.4.5. I5 Context-Specific Institutional Constraints

Effective inter-agency coordination was viewed as a distinguishing feature of successful geothermal systems. A local pool of people with skills and knowledge of geothermal energy was often mentioned as a precondition for success, and some respondents mentioned this as a limiting factor in Tanzania. Respondents frequently referred to Kenya as a positive example of consolidated governance and Ethiopia or Tanzania as settings where fragmented mandates impede progress. Cultural variation, government pressure, and challenging tendering situations due to local norms and bureaucracy were mentioned by many experts, as well as ethical tensions that arise from working legally in corrupt environments. In some countries, tribal politics and hierarchical decision-making are key institutional dynamics. Some experts claimed that all countries are fighting corruption, but it was also noted that, increasingly, people are aware that corruption is not tolerated. R9 stated that “corruption and dual power structures influence project execution.” R5 pointed out that “There must be zero tolerance to corruption and rent seeking.”

In some countries, too rigid rules lead to people not following them. One expert noted the complexity of adapting Western environmental standards too quickly in African contexts, which can create compliance issues. R4 stated, “The West is ‘imposing’ these rules on East Africa; it is not good to set unrealistic demands.”

4.5. Managerial Conditions

Managerial conditions encompass the leadership, planning and coordination practices that translate structural and institutional opportunities into operational results. This was the most frequently mentioned domain, reflecting the high importance attached to competent management across all interviewees.

4.5.1. M1 Leadership and Team Competence

All interviewees highlighted the importance of committed leaders who understand geothermal’s specific risks and realities. The experts described capable leadership as the principal success driver. “Leadership is crucial—coordination, communication and keeping everyone aligned on objectives,” noted expert R7. A crucial part of good leadership is being realistic. R1 phrased this in the following way: “You need to be realistic and tell it like it is, not raise the expectations of the politicians because that will just lead to disappointment.” Other experts highlighted the importance of experienced and empowered project management and firm leadership, separate from investor control.

Skilled teams to properly plan, execute and supervise geothermal projects were mentioned by many respondents. The inherent complexity of geothermal projects was addressed by R15. Creating the right culture within the project team, the technical competence of the team, and the importance of team qualifications were frequently mentioned, for example by R1: “You need qualified people, e.g., good geologist, geochemist, environmental specialist and so on.”

The importance of the project owners having knowledge and understanding of the nature of geothermal was mentioned by more than one expert, for instance the following statement by R2: “The best results are experienced when the energy companies are self-responsible for the projects.” Geothermal projects demand a mix of geological, engineering, environmental, financial, and stakeholder management expertise. R1 warned: “Some developers miss crucial things; you need to raise the flag in the early stages. Otherwise, it affects the outcome.”

4.5.2. M2 Professional Project Management and Control

Effective team dynamics and professionalism in project management are crucial to successful execution. Good project management practices prevent crises and ensure predictable, stable project implementation. Professional project management and understanding of stakeholder motivations are essential, and flexibility in practices and policies is important. R11 stated, “Project success depends on the project manager’s ability to recognise what motivates team members and other stakeholders.” R17 pointed out the importance of engaging the local communities and the local authorities. Solid project management coordination is vital due to the complexity of this type of project, which relies heavily on internationally procured equipment. As R3 put it, “you must have very good project management processes, solid coordination of logistics and financial control.” More than one expert addressed the need for experienced project managers and strong project teams. R2 pointed to a broader capacity issue: “The management of these projects must be as professional as possible. This has been lacking.”

Under-scoping, over-promising, and poor project monitoring were identified as recurring challenges in geothermal projects. At the same time, professional project management control and monitoring is crucial for success. R2 highlighted the need for robust management structures and accountability during implementation. “When this is lacking, the exploitation of geothermal energy will not be successful.”

4.5.3. M3 Adaptive and Realistic Planning

Several respondents described how rigid project structures, inflexible contracts, or donor-imposed rules had hampered progress. The ability to phase development and adapt to emerging findings was seen as essential, particularly during exploration and drilling. More than one expert explained how flexibility calls for good communication, trust, and good reporting. As R1 explained: “Flexibility is necessary in geothermal projects. Very rigid contracts may lead to bad results.” R4 similarly emphasised the importance of iterative planning and learning-by-doing approaches. R11 emphasised that agility is crucial due to variability in geothermal resource characteristics. “Iterative and collaborative management methods are needed.”

4.5.4. M4 Stakeholder Engagement and External Coordination

Several respondents spoke to the importance of “stakeholder-facing” project management. While closely related to the Meta-conditions, this was also described as a core project management function. R5 noted: “Collaborative relationships—especially with communities and local authorities—make or break projects.” This comment reflects an evolving view of project management as encompassing not only technical coordination, but also social engagement—especially in politically and culturally sensitive environments, where many geothermal projects are located. R1 discussed the importance of considering stakeholder perceptions and emphasised the need for community cooperation to prevent project disruptions. R5 added that the satisfaction of customers, the project team, and other stakeholders is central to project success. R8 stressed the importance of community and political engagement, especially local liaison officers, to ensure project continuity.

4.6. Meta-Conditions

In addition to structural, institutional, and managerial factors, most interviews yielded reflections aligned with the four meta-conditions: commitment, collaboration, alignment, and adaptation.

4.6.1. ME1 Commitment

Long-term governmental and organisational commitment was identified as the foundation for geothermal advancement. Geothermal projects outlive political cycles, and a long-term, steady commitment is needed. While the technical and financial requirements of geothermal projects are high, respondents emphasised that long-term success also depends on maintaining political will, institutional focus, and stakeholder perseverance during the early, uncertain phases. R2 emphasised the importance of long-term national focus: “The will is there! Geothermal energy is still seen as a key resource in meeting Kenya’s electricity needs.” Governmental support is required over time, especially during high-risk phases. R3 stated, “People in government need to be committed to the project—even when the going gets tough, they must be persistent.”

R4 pointed out a cultural “obstacle”—a lack of transparency, which results in ill-informed decision-making and is potentially detrimental to stakeholder commitment. “Unhindered flow of information is very important.” Furthermore, some realism by leaders is crucial, and avoiding wishful thinking and making unsubstantiated statements. In several interviews, Kenya was cited as an example where long-term institutional and political backing had created momentum in the geothermal sector.

4.6.2. ME2 Collaboration

Multi-stakeholder collaboration was discussed by most interviewees and emerged as both a challenge and an asset. Respondents emphasised the need for effective coordination among regulators, utilities, donors, and communities—particularly in contexts where overlapping mandates and fragmented governance are prevalent. R1 stated, “Gaining community support must be part of a broader collaboration strategy in project implementation.” The complex interactions with multiple governments, UNDP, and other institutional actors were often mentioned. R7 emphasised “the importance of involving both internal and external stakeholders and having the right team attitudes and readiness.” In Kenya, collaboration with global stakeholders has been instrumental in building up the geothermal sector. As R11 stated, “Collaboration with various stakeholders globally has been instrumental in building the technical capacity.” Some interviewees mentioned international training programs and cross-agency collaboration as effective in developing sectoral capacity and shared understanding.

4.6.3. ME3—Alignment and Adaptation

Adaptation was reflected in comments on learning, flexibility, and responsiveness. One expert commented on how the level of knowledge and competence in Africa has changed. R1 stated, “We have seen a big improvement in Africa in the last 10 years. Now we have projects pursued by private developers, the level of competence is rising fast, there is knowledge transfer, and we will see a rapid transformation of the situation in Africa.” Another kind of adaptation concerns the awareness in society of the dynamic nature of geothermal projects, and how this is sometimes difficult for people who are more inclined to make plans and just follow them to the end. R4 said, “The problem is that people often don’t realize that this kind of project needs to be very dynamic, if it isn’t, it’s likely that money will be wasted.” Some comments were given about the need for understanding the inherent risk in geothermal projects, where the subject is deep down in the earth and “expectation” management is needed. Similarly, several interviewees emphasized the need to adjust project plans in response to new information—whether geological, political, or financial.

The coherence of expectations, incentives, and plans among key actors emerged as a recurring theme. Some experts discussed mismatches between project phases, stakeholder mandates, or financing arrangements. R3 raised a key challenge in private sector participation: “Do the countries have legal structures for that? I mean, a private company investing and selling the power?” R9 addressed alignment by emphasising the need for structured and standardised processes that avoid reliance on heroics. Alignment with communities was also addressed, and project success involves community satisfaction, quality delivery, and good relationships: “Clients must be kept happy, neighbours must be kept happy with clean and environmentally friendly operation.” (R9).

A co-occurrence matrix was generated by counting the number of interviews in which any two sub-categories were both present.

The matrix reveals several areas of strong thematic co-occurrence. The highest was between S1—Resource characteristics and confirmation and M1—Leadership and team competence, which co-occurred in 15 of 17 interviews. Similarly, S1–M2—Professional project management and control co-occurred in 13 interviews. These patterns suggest that respondents who emphasised subsurface and exploration challenges also frequently discussed the need for strong teams and project management capacity. Moderate-to-strong co-occurrence was also found between S2—Capital intensity and both M1 (11) and M2 (9), as well as between I4—Early-stage financing mechanisms and M1 (9). A moderate link between I4 and ME1—Commitment (6) was also observed. Lower levels of co-occurrence were observed between most institutional and meta-conditions (e.g., I5–ME3 = 3), suggesting that interviewees generally discussed these conditions more discretely.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study reflect the broader shift in project management research toward more comprehensive notions of performance and value [21,22,24]. The experts interviewed in this study emphasised that geothermal success unfolds over long timescales and through cumulative phases of learning and adaptation—an understanding consistent with more recent sustainability-oriented perspectives [28]. As such, success in geothermal projects involves not only technical efficiency but also institutional maturity, stakeholder alignment, and enduring social value.

The findings show that the success of geothermal power projects in East Africa is a result of the interaction of multiple contextual factors, rather than isolated technical or managerial factors. The structural, institutional, managerial, and meta-conditions identified through the thematic analysis form an interdependent system. Verified geothermal resources and supportive infrastructure provide the technical foundation; institutional stability and coherent governance translate potential into action; managerial competence operationalises strategies; and sustained collaboration and commitment ensure continuity over time. Project success, therefore, emerges as a systemic property—circumstantial and dynamic—rather than the result of single critical success factors. By grounding this circumstantial perspective in expert accounts from geothermal projects, the findings provide empirical insight into how success conditions are experienced, combined, and prioritised in practice. This suggests that the “circumstances for success” perspective proposed in project studies may offer a useful lens for interpreting project outcomes in complex renewable-energy infrastructure contexts.

At the structural and institutional levels, the findings reaffirm the decisive role of resource confirmation and governance quality. The ability to verify the geothermal reservoir (S1) constitutes the most distinctive success condition for this project type, confirming earlier findings [5,36] that geothermal development follows a front-loaded risk curve in which exploration determines everything that follows. The study also highlights that policy clarity, infrastructure readiness, and political stability remain fundamental preconditions for investment, which is in line with earlier findings [2,10]. However, the findings further suggest that these structural and institutional conditions do not translate into project progress automatically. Instead, managerial competence functions as a mediating mechanism through which technical feasibility and institutional arrangements are converted into coordinated action under conditions of uncertainty. Equally important are coherent institutions capable of coordinating roles and financing mechanisms across agencies—conditions exemplified by Kenya’s comparatively successful model [40]. Conversely, fragmented mandates, weak transparency, or corruption can undermine even technically strong projects, echoing earlier findings regarding renewable-energy governance in emerging economies [34].

The most frequently referenced condition, leadership and team competence (M1), reflects the importance of human capability and professional experience in guiding complex, multidisciplinary projects. Effective leadership and team capability (M1) were repeatedly described as catalysts for coordination and learning, supporting earlier findings [33,34] that highlight leadership and top-management support as universal success factors for renewable energy. Professional project management and control, as well as adaptive and realistic planning (M2–M3), were similarly emphasised, but respondents repeatedly stressed the need for flexibility and iterative planning. Stakeholder engagement and external coordination (M4) was also recognised as a managerial responsibility central to project legitimacy and continuity, bridging the ethical and social dimensions of success. This indicates that in geothermal projects, leadership and professional project management play a qualitatively different role than in more predictable project environments, acting less as efficiency drivers and more as mechanisms for managing risk, expectations, and learning over long development horizons.

The meta-conditions identified—commitment, collaboration, alignment, and adaptation—represent the relational and behavioural glue that holds geothermal projects together across their long life cycles. These conditions explain how enabling structures and competent management are sustained over time. Long-term governmental and organisational commitment (ME1) was seen as indispensable for navigating lengthy exploration phases, while multi-stakeholder collaboration (ME2) facilitates capacity building and technology transfer. Taken together, these observations point to geothermal project success as being shaped by long-duration governance challenges rather than solely by a sequence of discrete delivery tasks. In addition to early-stage risk mitigation, the findings highlight the importance of institutional and organisational capacity to sustain direction, legitimacy, and coordination across political and project cycles. Alignment (ME3) between stakeholders reduces friction and expectation gaps, and adaptation ensures that projects remain responsive to evolving geological and political realities.

The interviews revealed that political turnover and short planning horizons frequently disrupt geothermal initiatives, and long-term stakeholder commitment (ME1) can be seen as a scarce but essential resource. Collaboration (ME2), both international and inter-institutional, was seen as crucial for capacity building and technology transfer, echoing [46] the role of global training networks, such as the GRÓ Centre, in developing geothermal expertise. Alignment and adaptation (ME3) reflect a focus on systemic learning capacity: only through shared purpose and continuous feedback can projects remain relevant within evolving environmental and policy contexts.

From a sustainability perspective, these meta-conditions correspond to the social and institutional “glue” that enables resilience—linking technical systems to human cooperation and ethical stewardship. They illustrate how the social dimension of sustainability (trust, learning, and partnership) interacts with the environmental (renewable resource use) and economic (stable investment) pillars of sustainable development.

Taken together, the evidence supports a circumstantial model of sustainable project success in which structural and institutional conditions establish feasibility and legitimacy, managerial competence converts these into operational results, and meta-conditions sustain long-term collaboration and learning. This model empirically extends contextual success theory by incorporating resource confirmation as a structural sub-condition unique to geothermal energy—thereby bridging project management research and energy transition studies. When considered alongside prior studies that emphasise either technical risk or more generic success factors, the findings offer additional insight into how success in geothermal projects is shaped by the interaction between geological uncertainty, institutional arrangements, and managerial practice. This perspective helps to interpret why similar projects may follow different trajectories across contexts. The findings further substantiate the proposition by [27] that sustainability and project success are convergent rather than competing objectives. Achieving SDG-related outcomes in low-carbon energy transitions requires precisely this combination of technical verification, institutional stability, professional management, and durable cooperation.

The co-occurrence matrix (Table 3) offers additional insight into how success conditions are experienced as interrelated in practice. The strong linkage between structural uncertainty (S1) and managerial competence (M1, M2) reinforces the argument that geothermal project viability depends not just on physical conditions, but also on the human and organisational capacity to respond to those conditions. Overall, the matrix adds weight to the view that geothermal project success depends not only on individual contextual conditions but on how they are integrated and reinforced across domains.

Table 3.

A co-occurrence matrix—the number of interviews in which any two sub-categories were both present.

6. Conclusions

This study set out to answer the question: What are the necessary contextual conditions for successful geothermal power project development in East Africa, as perceived by experienced professionals?

Drawing on seventeen semi-structured interviews, the findings show that the success of geothermal projects in East Africa arises from the interaction of structural, institutional, managerial, and meta-conditions, rather than from isolated technical or managerial factors. Geothermal projects are characterised by high geological uncertainty, long development horizons, and strong institutional embeddedness, which means that no single condition is sufficient on its own and project outcomes depend on how technical, institutional, and managerial conditions align and reinforce one another over time. This interaction is further supported by a co-occurrence analysis, which shows overlaps between key themes—particularly between structural and managerial subcategories.

First, the results confirm that structural circumstances—particularly the confirmation of the geothermal resource, the financing structure, and the definition of context-driven success criteria —form the essential technical and policy foundation for project progress. Without verified resource data, functioning infrastructure, and a clear market environment, even well-designed projects face financing and implementation barriers.

Second, institutional capacity and coherence emerge as decisive enablers. Political and institutional stability, clarity of roles and legal frameworks, and accessible early-stage financing mechanisms distinguish successful national programmes from those hampered by delays. Institutional maturity and continuity, therefore, represent fundamental prerequisites for long-term investment and effective risk sharing over extended project and political cycles.

Third, managerial competence serves as the operational bridge between context and performance. Leadership and team competence, together with professional project management, adaptive planning, and monitoring, were viewed as the most immediate determinants of day-to-day success, translating technical feasibility and institutional potential into tangible outcomes. This finding is reinforced by the strong co-occurrence between structural and managerial codes, suggesting that respondents view managerial capacity as essential for navigating technical risk and capital intensity.

Finally, the meta-conditions—commitment, collaboration, alignment, and adaptation—act as behavioural and relational forces that sustain projects over time. Long-term stakeholder commitment and effective multi-stakeholder collaboration were among the most frequently mentioned conditions, underscoring that trust, communication, and shared purpose are indispensable for maintaining momentum throughout multi-year development cycles. While co-occurrence between meta-conditions and other domains was generally modest, notable linkages with leadership and early-stage financing suggest that these relational enablers help support continuity and resilience in the face of uncertainty.

The study underscores that the acceleration of geothermal development in East Africa depends on integrated strategies that link geological exploration with governance reform, capacity building, and partnership continuity. Investment in these interdependent circumstances not only enhances project performance but also advances SDGs 7, 9, and 13, situating geothermal energy firmly within the broader agenda of sustainable development. Taken together, the findings indicate that a set of interdependent conditions are particularly critical for geothermal project success: early and credible resource confirmation, coherent and stable institutional arrangements, strong managerial competence, and sustained stakeholder commitment. These conditions do not operate independently but must be developed and maintained in combination.

The study provides empirical support for the circumstantial model proposed by Ika and Pinto and demonstrates its relevance for analysing complex, uncertainty-intensive energy infrastructure projects.

The research carries practical implications for policymakers and development partners. Priority attention should be given to strengthening exploration financing mechanisms, reinforcing institutional coordination and continuity, and investing in professional project management capacity alongside technical expertise. In doing so, such initiatives will accelerate geothermal deployment in East Africa and advance SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), and SDG 13 (Climate Action).

Future research could further test the circumstantial success model across renewable-energy technologies and regions, integrating quantitative and longitudinal approaches to capture how success conditions evolve. For practitioners, the central message is clear: geothermal projects succeed when technical verification, institutional stability, managerial professionalism, and sustained social partnership converge within a shared commitment to sustainable development.

Beyond its theoretical contribution, the research also provides a methodological and practical contribution consistent with the aims of this Sustainability Special Issue. It demonstrates how a structured, context-sensitive analysis can be used as a tool for understanding sustainability and resilience in complex, climate-relevant infrastructure systems. By interpreting geothermal development as a configuration of interdependent circumstances—technical, institutional, managerial, and relational—the study advances a transdisciplinary perspective on how renewable energy projects can build adaptive capacity under uncertainty. The co-occurrence matrix introduced in this study adds further empirical support for these interdependencies. While not indicating causality, it reveals that certain combinations of success conditions—such as resource confirmation and managerial competence, or early-stage financing and leadership commitment—are frequently discussed together by experts. This supports the interpretation that geothermal project success depends not only on the presence of enabling conditions but also on their alignment and interaction.

While the study benefited from the GRÓ Centre’s extensive professional network to access highly experienced geothermal specialists, this purposeful sampling approach may also introduce some degree of selection bias, as all interviewees have direct or indirect ties to the programme. However, given GRÓ’s longstanding role in geothermal capacity development across East Africa, this network represents a uniquely relevant and knowledgeable expert community for examining the contextual conditions that contribute to project success.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T.I.; methodology, H.T.I.; validation, T.V.F. and H.T.I.; formal analysis, H.T.I.; writing—original draft preparation, H.T.I.; writing—review and editing, H.T.I. and T.V.F., supervision, H.T.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study according to the guidelines of the Joint Committee on Research Ethics of the Icelandic Universities, approved 5 November 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the professionals who participated in the interviews for this research and generously shared their insights into geothermal development in East Africa. Special thanks are extended to the GRÓ Centre for Capacity Development in Iceland for its long-term contribution to knowledge exchange and training in geothermal energy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wolfson, R. Energy from Earth and Moon. In Energy, Environment, and Climate, 2nd ed.; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gehringer, M.; Loksha, V. Geothermal Handbook: Planning and Financing Power Generation; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/23712 (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- DiPippo, R. Geothermal Power Plants: Principles, Applications, Case Studies and Environmental Impact; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pasqua, C.; Chiozzi, P.; Verdoya, M.; Pasqua, C.; Chiozzi, P.; Verdoya, M. Geothermal Play Types along the East Africa Rift System: Examples from Ethiopia, Kenya and Tanzania. Energies 2023, 16, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngugi, P.K. Risks and Risk Mitigation in Geothermal Development. In United Nations University—Geothermal Training Programme. 2014. Available online: https://orkustofnun.is/gogn/unu-gtp-sc/UNU-GTP-SC-18-41.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Teklemariam, M. Overview of Geothermal Resource Utilization and Potential in the East African Rift System. In United Nations University—Geothermal Training Programme. 2008. Available online: https://orkustofnun.is/gogn/unu-gtp-sc/UNU-GTP-SC-08-02.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Georgsson, L.S. Geothermal Energy in the World from an Energy Perspective. In Exploration for Geothermal Resources—United Nations University—Geothermal Training Programme. 2015. Available online: https://orkustofnun.is/gogn/unu-gtp-sc/UNU-GTP-SC-21-0201.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Fridgeirsson, T.V.; Ingason, H.T.; Onjala, J. Innovation, Awareness and Readiness for Climate Action in the Energy Sector of an Emerging Economy: The Case of Kenya. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ika, L.A. Project management for development in Africa: Why projects are failing and what can be done about it. Proj. Manag. J. 2012, 43, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M. Public Policy Failure: ‘How Often?’ and ‘What Is Failure, Anyway’?—A Study of World Bank Project Performance; Center for International Development at Harvard University; Report No.: 344; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Available online: https://dash.harvard.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/e15a4c50-941f-4fa8-8dbe-2759ae01dcf1/content (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Ika, L.; Keeys, L.; Tuuli, M.; Sané, S.; Ssegawa, J.K. Call for Papers Special Collection: Managing and Leading Projects in Africa—Call for Papers. Project Leadership and Society. 2021. Available online: https://www.journals.elsevier.com/project-leadership-and-society/call-for-papers/journals.elsevier.com/project-leadership-and-society/call-for-papers/undefined (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Flyvbjerg, B. What you Should Know about Megaprojects and Why: An Overview. Proj. Manag. J. 2014, 45, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ika, L.A.; Donnelly, J. Success conditions for international development capacity building projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.K. Project management, governance, and the normalization of deviance. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, J.W.; Bertani, R.; Boyd, T.L. Worldwide Geothermal Energy Utilization 2015. GRC Trans. 2015, 39, 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ika, L.A.; Pinto, J.K. The “re-meaning” of project success: Updating and recalibrating for a modern project management. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2022, 40, 835–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.; Jugdev, K. Critical success factors in projects: Pinto, Slevin, and Prescott—The elucidation of project success. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2012, 5, 757–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ika, L.A.; Söderlund, J.; Munro, L.T.; Landoni, P. Cross-learning between project management and international development: Analysis and research agenda. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2020, 38, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ika, L.; Pinto, J. Dont ask what makes projects successful, but under what circumstances they work: Recalibrating project success factors. In Research Handbook on Project Performance; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; pp. 75–91. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Lavagnon-Ika/publication/369464186_Dont_ask_what_makes_projects_successful_but_under_what_circumstances_they_work_recalibrating_project_success_factors (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Atkinson, R. Project management: Cost, time and quality, two best guesses and a phenomenon, its time to accept other success criteria. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 1999, 17, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, A. Measurement of project success. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 1988, 6, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke-Davies, T. The “real” success factors on projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2002, 20, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ika, L.A. Project Success as a Topic in Project Management Journals. Proj. Manag. J. 2009, 40, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenhar, A.J.; Dvir, D.; Levy, O.; Maltz, A.C. Project Success: A Multidimensional Strategic Concept. Long Range Plan. 2001, 34, 699–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, E.S.; Birchall, D.; Jessen, S.A.; Money, A.H. Exploring project success. Balt. J. Manag. 2006, 1, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, B.A. Factors influencing project success criteria. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 7th International Conference on Intelligent Data Acquisition and Advanced Computing Systems (IDAACS), Berlin, Germany, 12–14 September 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 566–571. Available online: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6662988/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Silvius, G. Sustainability as a new school of thought in project management. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 1479–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabini, L.; Muzio, D.; Alderman, N. 25 years of ‘sustainable projects’. What we know and what the literature says. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 820–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltzman, R.; Shirley, D. Green Project Management; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; 291p; Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Green%20Project%20Management&publication_year=2011&author=R.%20Maltzman&author=D.%20Shirley (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Ingason, H.T.; Jonasson, H.I. Project ethics: The Critical Path to Project Success—Applying an ethical risk assessment tool to a large infrastructure project. In Proceedings of the International Project Management Association Research Conference 2017, Incheon, Republic of Korea, 2–4 November 2017; University of Technology, Sydney: Ultimo, Australia, 2018. Available online: https://utsepress.lib.uts.edu.au/site/chapters/10.5130/pmrp.ipmarc2017.5639/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Shokouhi, M.; Bachari, M.S. An overview of the aspects of sustainability in project management. Prog. Eng. Sci. 2025, 2, 100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvius, G.; Schipper, R.; Huemann, M.; Turner, R. Sustainable project management. In The Handbook of Project Management, 6th ed.; Huemann, M., Turner, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781003274179 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Mokan, K.V.; Lee, T.C.; Ramlan, R. The Critical Success Factors for Renewable Energy Projects Implementation. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2019, 8, 223–226. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, R.R.; Jutidamrongphan, W.; Gyawali, S.; Chowdhury, S. Managing Sustainable Energy Projects: A Review on Success Factors. NeuroQuantology 2022, 20, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauschild, M.Z.; Kara, S.; Røpke, I. Absolute sustainability: Challenges to life cycle engineering. CIRP Ann. 2020, 69, 533–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, A.M.; Dobson, P.F. Refining the Definition of a Geothermal Exploration Success Rate. In Proceedings of the 41st Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering, Stanford, CA, USA, 22–24 February 2016; p. 11. Available online: https://pangea.stanford.edu/ERE/pdf/IGAstandard/SGW/2016/Wall2.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Serdjuk, M.; Dumas, P.; Angelino, L.; Tryggvadottir, L. Geothermal Investment Guide. European Geothermal Energy Council (GEOELEC); 2013 Nov. Report No.: Deliverable No 3.4. Available online: http://www.geoelec.eu/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/D3.4.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Kombe, E.; Muguthu, J. Geothermal Energy Development in East Africa: Barriers and Strategies. J. Energy Res. Rev. 2018, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorollahi, Y.; Shabbir, M.S.; Siddiqi, A.F.; Ilyashenko, L.K.; Ahmadi, E. Review of two decade geothermal energy development in Iran, benefits, challenges, and future policy. Geothermics 2019, 77, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabzonlu, B.; Caner, E. Exploring Critical Success Factors for Geothermal Investments. In Collaboration and Integration in Construction, Engineering, Management and Technology; Ahmed, S.M., Hampton, P., Azhar, S., Saul, A.D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: London, UK, 2021; Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-48465-1 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Shortall, R.; Davidsdottir, B.; Axelsson, G. A sustainability assessment framework for geothermal energy projects: Development in Iceland, New Zealand and Kenya. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 50, 372–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesenthal, C.; Clegg, S.; Mahalingam, A.; Sankaran, S. Applying institutional theories to managing megaprojects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engwall, M. No project is an island: Linking projects to history and context. Res. Policy 2003, 32, 789–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannerman, P. Defining project success: A multilevel framework. In Proceedings of the PMI Research Conference, Warsaw, Poland, 13–16 July 2008; Project Management Institute: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2008. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Paul-Bannerman-2/publication/242331546_Defining_Project_Success_A_Multi-Level_Framework/links/02e7e51cd06e3bc91a000000/Defining-Project-Success-A-Multi-Level-Framework.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Eggleton, D.; Dacre, N.; Cantone, B.; Gkogkidis, V. From Hypothesis to Evidence: Testing the Ika and Pinto Four-Dimensional Model of Project Success; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5003846 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Georgsson, L.S.; Haraldsson, I.G.; Ómarsdóttir, M. UNU Geothermal Training Programme in Iceland: Sharing Geothermal Knowledge with Developing Countries for 41 Years. In Proceedings of the World Geothermal Congress, 24–27 October 2021; World Geothermal Congress: Reykjavik, Iceland, 2021. Available online: https://www.stjornarradid.is/library/03-Verkefni/Utanrikismal/Grein-um-UNU-GTP---starfsemi-skolans.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.