Abstract

Food security and income generation remain a critical issue for small-scale farming households in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) due to population growth, climate change, and market instability. Indigenous leafy vegetables (ILVs) offer high nutritional value and have the capability to mitigate food insecurity but are underutilized due to social stigma. This review aims to systematically analyze the food and income contribution of cultivation and utilization of ILVs by small-scale farming households in Sub-Saharan Africa. This review analyses the literature on the role of ILV cultivation in enhancing food security and household income over the past two decades. A systematic search across five databases was conducted and identified 53 relevant studies. Findings indicate that ILVs contribute significantly to household nutrition and income through consumption and surplus sales. However, ILV cultivation faces barriers such as climate change, pest infestations, land degradation, water scarcity, insecure land tenure, limited agricultural training, poor communication networks, and restricted market access. Policy interventions are necessary to support small-scale farmers in ILV cultivation by providing agricultural extension services, promoting sustainable farming practices, and integrating ILVs into food security strategies. Further research should examine policy frameworks and supply chain mechanisms to enhance farmer participation and economic benefits from ILV production.

1. Introduction

Globally, several challenges such as a growing population, climate change, and the double burden of malnutrition continue to hinder overall livelihood and development. Meanwhile, indigenous leafy vegetables (ILVs) remain underutilized, despite their considerable nutritional and medicinal benefits. ILVs provide essential nutrients, including vitamins, minerals, proteins, dietary fibre, and antioxidants [1]. These nutrients contribute to manage chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, anemia, and cancer, thereby improving overall health and well-being [1,2]. However, the underutilization of ILVs poses significant challenges to the overall livelihood of small-scale farming households including health, food security, and income generation. This underuse is closely linked to malnutrition, reduced life expectancy, and limited income generation opportunities, which further hinder the overall development of these communities [3,4].

Several barriers contribute to the low cultivation and utilization of ILVs, particularly among small-scale farmers. These include limited access to inputs, negative perceptions, low government support, and limited market access. Due to this, small-scale farmers often rely on seeds from previous harvests, which limits their yield [5]. Negative perceptions include that ILVs are often perceived as “food for the poor,” which reduces their recognition, causing their nutritional and economic benefits to be overlooked [6]. Government interventions generally focus on staple crops and commercial farming, leaving ILV small-scale farmers with insufficient support, particularly in areas lacking infrastructure, which limits their ability to access markets [7]. Consequently, small-scale farmers find it hard to reach mainstream markets, preventing communities from obtaining ILVs’ full health and economic potential.

The limited production and consumption of ILVs directly affect the ability of households to provide nutritious food and generate income through sales in local markets. Growing interest in traditional knowledge about food and medicinal plants highlights the potential of ILVs for sustainable livelihoods and economic opportunities [8]. Although several studies have focused on the nutritional value (e.g., vitamins, minerals, zinc) of ILVs [1,2,9], there is a lack of systematic sorting out of data based on the broader socio-economic impact of ILV cultivation and use, particularly at a regional or global level. This data includes the income growth achieved by small-scale farmers in SSA through ILVs. Understanding the cultivation and utilization of ILVs is essential for empowering small-scale farmers and cooperatives to enhance productivity, income generation, and overall community well-being.

This review aims to address the gap by systematically synthesizing relevant research on the socio-economic contributions of ILV cultivation and utilization by small-scale farming households between 2005 and 2024. The study will focus on the Sub-Saharan Africa region and examine the types of ILVs cultivated, the challenges involved, and the factors influencing ILV cultivation and use. The main aim is to assess the role of ILV production in enhancing food security and income generation for small-scale farmers, promoting sustainable agricultural practices and improving community well-being. Moreover, the specific objectives of this review are to (1) document the ILVs produced in SSA; (2) determine the challenges in ILV cultivation and utilization; and (3) evaluate the food and income contribution of producing and utilizing these vegetables.

By exploring the relationship between ILV cultivation, food security, and economic stability, this review aligns with several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Specifically, it supports SDG 1 (poverty reduction), SDG 2 (eliminating hunger), SDG 3 (improving health and well-being), and SDG 8 (promoting sustainable economic growth and employment). The findings from this review contribute to academic research and policy development, emphasizing the potential of ILVs to enhance the livelihoods of small-scale farming households while supporting socio-economic development and environmental sustainability.

Conceptual Framework

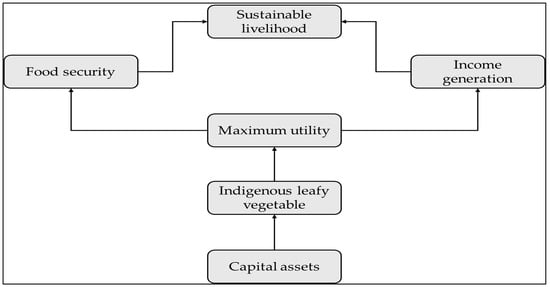

This study adopted a conceptual framework for enhancing the food and income contribution of ILV cultivation and utilization by small-scale farming households as illustrated in Figure 1. From this framework, it can be deduced that small-scale farming households in SSA rely on various capital assets, which can be categorized into human (skills, knowledge, and health), social (relationship, trust, and networks), natural (land, water, and resources), physical (infrastructure, tools, and equipment), and financial (cash, savings, credit). These factors determine the production of ILVs, which is crucial for food security and income generation. Indigenous leafy vegetables, being well-adapted to local environmental conditions, and exhibiting low resource requirements and resilience to climate change impacts, are suitable for small-scale farming households in SSA [10]. Despite their nutritional abundance, potential to diversify diets, and ability to improve health, these vegetables often face constraints such as limited access to quality seeds, lack of extension services, and social stigma that undervalues their utilization [11].

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for enhancing food and income contribution of ILVs by small-scale farming households. Source: author’s compilation (2025).

Overcoming these constraints can help maximize the utility of ILVs, allowing households to not only use these vegetables for nutritional diets, but also to generate income through sales [12]. This would foster food security and income, thus leading to the attainment of sustainable livelihood. This is because the initiative of integrating ILVs into smallholder farming systems offers a roadmap to achieving sustainable livelihoods. This is accomplished through the linkage of traditional knowledge with modern agricultural practices and market opportunities. When smallholder farmers enhance ILV production and utilization, they invest in climate-resilient strategies that provide ongoing nutritional and economic benefits, which reduce the dependency on costly inputs.

2. Materials and Methods

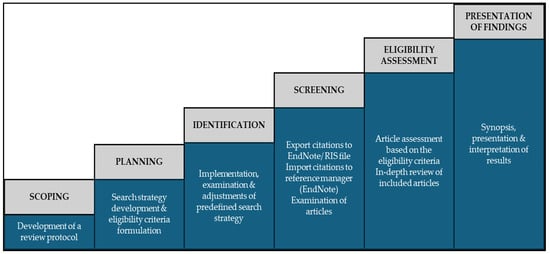

This review adopted the systematic review framework developed by Koutsos, et al. [13] which provides a structured roadmap for conducting systematic reviews in agricultural research. This framework was built upon the core principles of the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) methodology. It consists of six stages namely (1) scoping, (2) planning, (3) identification, (4) screening, (5) eligibility/assessment, and (6) presentation as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Systematic review framework in agricultural research. Source: adopted from Koutsos, et al. [13].

2.1. Scoping

Scoping refers to the process of laying out the key concepts, evidence types, and research gaps in the field of study [13]. In this review, scoping is employed to map the existing evidence on the food and income contribution of cultivating and utilizing indigenous leafy vegetables (ILVs) by small-scale farming households in Sub-Saharan Africa. The focus of the review is on understanding the contribution of ILV cultivation and utilization to food security and income generation among small-scale farming households in Sub-Saharan Africa with evidence from the year 2005 to 2024. To structure the review and ensure clarity, the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) method is used as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

PICO framework for reviewing the food and income contribution of producing and utilizing ILVs by small-scale farming households in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Furthermore, a series of keywords was formulated using the PICO alignment with the review to ensure logical and comprehensive data collection. These keywords are set to ensure easy selection of words used in the search query with the ability to draw conclusions based on the food and income contribution of the cultivation and utilization of ILVs by small-scale farming households in the selected region. The keywords formulated are shown in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Keywords associated with each PICO element.

2.2. Planning

Planning is an essential procedure to ensure the study progresses in the correct way. It consists of the search strategy (how the search is to be conducted and why is it conducted in that way) and eligibility criteria (to ensure the selection of relevant reports and exclusion of irrelevant ones).

2.2.1. Search Strategy Development

Database Selection

This study employed a systematic approach to review the literature, utilizing databases, namely (1) ScienceDirect, (2) Web of Science, (3) EBSCOhost Web, (4) University of Zululand (UNIZULU) Library Ultimate Search Collection, and (5) PubAg (USDA). These databases were chosen for their strong relevance to small-scale farming, food security, and agricultural research. ScienceDirect provides high-quality, peer-reviewed studies on agriculture, food security, and nutrition, while Web of Science ensures access to widely cited, high-impact research across multiple disciplines [14]. EBSCOhost Web offers a rich collection of academic literature covering the socio-economic aspects of farming and rural development [15]. The UNIZULU Library Ultimate Search Collection provides institutionally curated resources, ensuring access to both local and international studies relevant to Sub-Saharan Africa [16]. Finally, PubAg, managed by the USDA (United States Department of Agriculture), specializes in agricultural and food research [17], making it particularly useful for exploring the production and economic benefits of indigenous leafy vegetables. Together, these databases provide a good foundation for understanding the intersection of food production, income generation, and food security among small-scale farmers. The following is a detailed explanation on why each filter used was designed and conducted in the manner presented.

Keywords

The keywords (“small-scale farmers” OR “small scale farmers” AND “indigenous leafy vegetables” OR “ILVs” AND “food security” AND “income generation”) were selected due to their relevance to the study, ensuring that the aim of the study is maintained. The inclusion of “small-scale farmers” captures research focused on smallholder agricultural practices, while “indigenous leafy vegetables” (ILVs) specifically targets studies on these vegetables. “Food security” aligns with the study’s objective of assessing the contribution of ILVs to household food security, and “income generation” ensures that the economic implications are considered. The use of Boolean operators (AND, OR) helps enhance the search strategy by broadening the scope to include variations in terminology while maintaining focus on the study’s main themes.

Region

The study focuses on Sub-Saharan Africa as the scope of origin due to the region’s significant reliance on small-scale farming for food production and livelihoods. Indigenous leafy vegetables (ILVs) play a crucial role in household nutrition and income generation, particularly among rural and peri-urban farming communities. Sub-Saharan Africa faces persistent food security challenges, making it an ideal setting to assess how ILVs contribute to dietary diversity and economic resilience [18]. This geographical focus ensures the study’s findings are relevant to policy interventions aimed at improving agricultural sustainability and food security.

Years

The review chose studies published between 2005 and 2024 to ensure a comprehensive and up-to-date analysis of the contribution of indigenous leafy vegetables (ILVs) to food security and income generation among small-scale farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa. This timeframe captures two decades of research, reflecting both historical trends and recent developments in agricultural practices, climate change impacts, and policy interventions. Selecting studies from 2005 onwards allows for the inclusion of more recent advancements in agricultural technology, food security policies, and economic shifts affecting smallholder farming. Moreover, this period aligns with global and regional efforts, such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (2000–2015) and the SDGs (2015–2030) [19], which emphasize food security and poverty reduction. The inclusion of research up to 2024 ensures that findings remain relevant to current academic and policy discussions.

Source Types/Resource Type/Document Type/Article Type

This study prioritizes research articles, full-text sources, academic journals, and scholarly articles to ensure credibility and academic rigour. Research articles provide original findings and methodologies relevant to ILVs, food security, and small-scale farming. Full-text sources allow for a deeper analysis of data and conclusions, while academic journals ensure peer-reviewed, high-quality research. Scholarly articles contribute expert insights, grounding the study in established theories and empirical evidence. By focusing on these resource types, the research maintains reliability, depth, and scholarly integrity.

Access Type

This study prioritizes open access, open archive, peer-reviewed, and full-text sources to ensure accessibility, credibility, and academic rigour. Open access and open archive sources allow unrestricted access to scholarly research, enabling comprehensive data collection without financial barriers. Peer-reviewed articles ensure that the study is based on high-quality, rigorously evaluated research, enhancing reliability [20]. Full-text sources provide complete studies rather than abstracts, allowing for a thorough analysis of methodologies, results, and conclusions. By focusing on these access types, the study ensures transparency, academic integrity, and inclusivity.

Language

This review only selected reports written in English language to ensure accessibility to a broad academic audience and facilitate engagement with a wide range of scholarly literature. English is the dominant language in academic publishing, particularly in disciplines related to agriculture, food security, and economic development. Many high-impact peer-reviewed journals, research articles, and policy reports are published in English, allowing for comprehensive data collection and analysis [21]. Additionally, using English ensures that the study can be widely disseminated and referenced in international research and policy discussions, contributing to the broader discourse of this review.

Research Areas/Publication Title

The primary research area for this study is agriculture, as it directly relates to the cultivation, utilization, and economic significance of indigenous leafy vegetables (ILVs) among small-scale farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa. This field encompasses key themes such as crop production, food security, sustainable farming practices, and rural livelihoods, aligning with the study’s objectives. Publications in agricultural sciences, food security, rural development, and agribusiness will be prioritized, as they provide empirical research, policy discussions, and scientific advancements relevant to ILVs and their contribution to income generation and nutrition. By focusing on agriculture-related research areas and journals, the study ensures that findings are contextually relevant, evidence-based, and applicable to smallholder farming systems in the region.

Publisher

The study prioritizes MDPI, Wiley Online Library, Elsevier, Springer Nature, as well as Taylor & Francis as key publishers due to their strong reputation in producing high-quality, peer-reviewed journals in the fields of agriculture, economics, and sustainability. MDPI is known for its open access journals, such as ‘Sustainability’, which often cover agricultural sustainability and food security topics. Wiley Online Library publishes journals like ‘Agricultural Economics’ and ‘Global Food Security’, which explore the intersection of agriculture, economics, and policy. Elsevier is a trusted source for journals like ‘Food Policy’ and ‘Field Crops Research’, which provide insights into agricultural systems and socio-economic impacts. Springer Nature offers publications like ‘Agriculture and Human Values’. Taylor & Francis is also renowned for its work in agricultural systems and sustainability. These publishers ensure access to credible, peer-reviewed resources that are necessary for this review to be conducted.

Subject/Subject Area/Journal Title

The study is situated within the subject areas of Agricultural and Biological Sciences, Economics, Econometrics, and Finance, as these fields are critical for understanding the relationship between small-scale farming, food security, income generation, and livelihoods in Sub-Saharan Africa. These disciplines provide a holistic approach to examining agricultural systems, crop production, and the economic impact of indigenous leafy vegetables (ILVs) on rural households. Relevant journal titles for this research include the International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, which focuses on sustainable agricultural practices and their socio-economic effects, aligning with the study’s goals. Additionally, Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment offers insights into the environmental and agricultural systems related to ILVs, while Food Policy addresses the connection between food security, agricultural practices, and policy.

Databases

The study made use of Academic Search Complete, Library and Information Science Source, and Africa-Wide Information databases to ensure a thorough and well-rounded collection of research. Academic Search Complete provides access to a broad range of peer-reviewed journals across disciplines like agriculture, economics, and sustainability, making it a valuable resource for studying small-scale farming and food security. Library and Information Science Source offers insights into how agricultural knowledge is shared and used, which is important for understanding policy development in rural communities. Africa-Wide Information is essential for accessing region-specific research on Sub-Saharan Africa, providing key insights into the local agricultural and socio-economic contexts.

2.2.2. Eligibility Criteria

To select relevant reports, the following inclusion criterion was set:

- (1)

- Reports issued within the past 20 years (2005 to 2024) are used to ensure the relevance of the research. Using these years ensures that the findings reflect trends and development as it consists of findings from the past years till the recent years.

- (2)

- Reports that focus on Sub-Saharan Africa are used to ensure consistency with the aim of the review/study. Moreover, this region faces several challenges pertaining to food security, income generation, and ILV production and utilization.

- (3)

- Reports published in English language are used as it is the medium of instruction. This is to ensure uniformity in analysis and avoid translation bias.

- (4)

- Studies that investigate the contribution of ILV cultivation and/or utilization towards food security and income generation are used. This focus helps to capture evidence interlinking the practical realities of ILV production and utilization at the household level with livelihood dynamics.

- (5)

- Studies involving farmers, agricultural workers, or any individuals directly involved in ILV cultivation will be considered. This ensures that the target population is used as a unit of analysis.

- (6)

- Peer-reviewed papers, research articles, and relevant publications that meet the criteria for eligibility will be included. This is so as to ensure data accuracy and credibility of the articles used.

To ensure that the papers included in this systematic review do not deviate from the original purpose, the following exclusion criteria were established:

- (1)

- Reports issued outside the range of 2005 to 2024 were excluded to ensure acknowledgement of relevant and consistent findings. This is because outside this timeframe, the information may not be able to reflect all current trends or even look outside the times where this issue was not addressed properly or adequately.

- (2)

- Book chapters were avoided to gather real-time results. This is because book chapters often present theoretical discussions rather than empirical findings, which are pivotal for assessing measurable outcomes related to ILV cultivation and utilization.

- (3)

- Reports that were still in progress or unpublished were excluded to gather reliable results. This was to ensure that only information that was validated and publicly accessible is included.

- (4)

- Studies written in languages other than English were removed. This was to avoid interpretation errors and keep consistency in data analysis.

- (5)

- Studies that did not focus on one or more of these terms (indigenous leafy vegetables/small-scale farmers/food security/income security) were considered unfeasible. Terms outside the above-mentioned did not contribute to the core aim of the review.

- (6)

- Reports focusing on regions other than the Sub-Saharan Africa region were excluded. This was mainly for maintaining contextual uniformity and ensuring relevance to the review.

2.3. Identification

The search query was conducted in line with the search strategy development outlined above. To conduct the search, keywords were used to identify the literature with the terms that formulate the overall purpose of the search. For filtering, the region, years, article type, access types, and other relevant filters were used in each database. Following is a detailed search from each database used in this review:

ScienceDirect

On ScienceDirect, the keywords were used and resulted in a total of 160,654 reports. After the region, years, article types, subject area, language, publication title, and access type were applied, respectively, and a total of 372 reports were retrieved. Table 3, as seen below, is a step-by-step summary of how the search for this database was conducted.

Table 3.

Step-by-step search and filter in the ScienceDirect database.

Web of Science

On the Web of Science database, the keywords resulted in 5771 reports. The search was filtered to focus on the region, years, document type, language, research areas, publishers, and access type, resulting in a total of 304 reports retrieved. Table 4, as seen below, is a summary of the search conducted for this database.

Table 4.

Step-by-step search and filter in the Web of Science database.

EBSCOhost Web

On EBSCOhost Web, the use of keywords resulted in a total of 7946 reports. Filters used include the region, years, source types, publishers, language, access type, and databases which limited the number of reports retrieved to 378. Table 5, as seen below, is a summary of the search conducted for this database.

Table 5.

Step-by-step search and filter in the EBSCOhost Web database.

University of Zululand Library Ultimate Search Collection

On this database, the keywords were applied and resulted in a total of 8034 reports. Region, years, language, databases, article type, source type, and publisher were the filters employed, which provided a total of 229 reports. Table 6, as seen below, is a summary of the search conducted for this database.

Table 6.

Step-by-step search and filter in the University of Zululand Library Ultimate Search Collection database.

PubAg

Using PubAg, the keyword search resulted in a total of 2774 reports. Secondly, the search was filtered to look at the region, years, language, resource type, subject, and journal title, whereby a total of 171 reports were retrieved. Table 7, as seen below, is a summary of the search conducted for this database.

Table 7.

Step-by-step search and filter in the PubAg database.

After filtering, the total retrieved from each database was added to the other databases to keep a record of the number of reports left after identification. The following equation was used to sum up the totals retrieved (Equation (1)):

Total retrieved (Σn) = ScienceDirect + Web of Science + EBSCOhost Web +

University of Zululand Library Ultimate Search Collection + PubAg

University of Zululand Library Ultimate Search Collection + PubAg

Σn = 372 + 305 + 378 + 229 + 171

Σn = 1455

The total number of reports retrieved after filtering from the five selected database search engines is 1455.

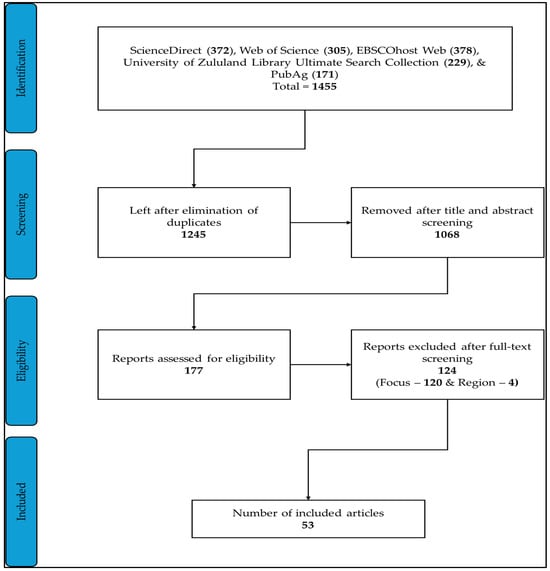

2.4. Screening

After the identification step, 1455 reports were exported to an RIS file and imported into EndNote for proper reference management. In EndNote, a total of 210 duplicates were found and removed. After the removal of duplicates, the remaining 1245 reports were screened using the title and abstract against the inclusion criteria. A total of 177 reports were retrieved after screening, eliminating 1068 articles. The eligibility criteria, referred to as the full-text screening, was then applied to recognize the relevant reports to be included and the irrelevant ones to be excluded. The screening process was performed independently by all authors to minimize selection bias. Any disagreements were discussed and resolved to ensure consistency and transparency throughout the screening process.

2.5. Eligibility

The reports obtained after title and abstract screening were retrieved and evaluated against the predefined eligibility criteria to determine whether they aligned with the study’s objectives. A total of 124 articles were deemed not suitable and were removed based on the requirements, which resulted in 53 articles being considered eligible. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) was then used to check the quality of each report. This framework provides a structured checklist specifically designed for appraising systematic reviews. This checklist comprises 10 key questions that guide reviewers in evaluating the validity, results, and relevance of a systematic review. Table 8 shows the quality assessment using the CASP systematic review checklist.

Table 8.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Systematic Review Checklist.

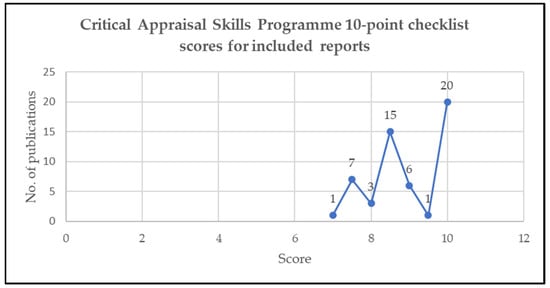

The results for the quality of reports used are shown in Appendix A, Table A1, which reveal how well each article met each criterion. The scores were presented as “No” = 0; “Could not tell” = 0.5; and “Yes” = 1. Studies below a score of 5 out of 10 were removed, while those with a higher score were kept, ensuring high-quality input for the review. Figure 3 outlines the scores of the retrieved reports against the quality checklist.

Figure 3.

CASP quality test scores for included studies. Source: Author’s compilation (2025).

After quality testing, no studies were found to have a quality of less than 5, emphasizing that they were all valid, reliable, and relevant to the review. The scores for each study are outlined in Table A1. The total number of reports to be included in the systematic review was found to be 53. Figure 4, as seen below, is a summary of the review process using the PRISMA framework. The PRISMA checklist (see Supplementary Materials), adopted from Page, et al. [23], was used in this review to ensure it meets the specifications of a systematic review.

Figure 4.

PRISMA framework for the review process of the food and income contribution of cultivating and utilizing ILVs by small-scale farming households in SSA. Source: Authors’ compilation (2025).

Data Collection and Analysis

The reports included for the review were exported to a new library in EndNote for reference management and downloaded for further reading to collect relevant data. The quantitative data obtained was recorded and analyzed in Microsoft Excel 365, while the qualitative data was analyzed using themes and focus areas.

3. Results

This part of the review offers a thorough analysis of the findings obtained from the 53 reports included in the review. Key results to be discussed include analysis concerning the publication, structure of the paper, and the link between the studies and the purpose of the review.

3.1. Years of Publication

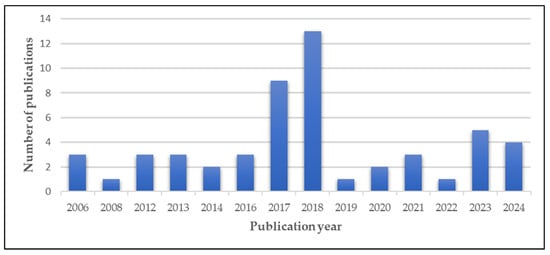

The inclusion of specific years is essential for understanding the relevance and progression of the study. This review indicates that the theme under investigation remains pertinent across both decades selected for analysis. As shown in Figure 5, the distribution of articles by year reveals that 2018 had the highest number of publications, with thirteen reports, followed by 2017 with nine reports. The years 2023 and 2024 featured five and four reports, respectively. Other years with moderate representation include 2006, 2012, 2013, 2016, and 2021, with each contributing three reports. The years 2014 and 2020 had two reports each, while the least number of publications were found in 2008, 2019, and 2022, with only one report per year. These findings highlight 2018 as the year with the most significant research output related to the key themes of this review.

Figure 5.

Publication year vs. number of articles published. Source: Synthesis data (2025).

3.2. Publication Study Area

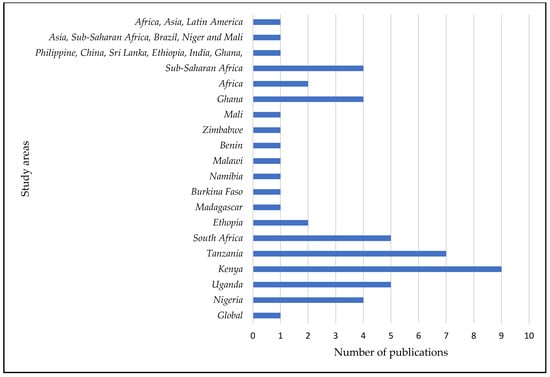

The study area highlights the geographical locations where the research was conducted, helping to assess the relevance of the issue across different regions. As illustrated in Figure 6, Kenya leads with nine publications, followed by Tanzania with seven publications. South Africa and Uganda each contribute five publications, while Sub-Saharan Africa, Ghana, and Nigeria each have four publications. Ethiopia and Africa are represented by two publications each, and the remaining regions are represented by a single publication. These findings indicate that Kenya is the region where most of the themes discussed in this review are most prominently observed.

Figure 6.

Relevance of studies in different areas. Source: Synthesis data (2025).

3.3. Journals and Publishers

Publishers and journals play a crucial role in assessing the scope and impact of research. For this study, reports were extracted from five publishers, each representing journals within specific subject areas. As shown in Table 9, Elsevier stands out as the publisher with the highest number of reports, contributing 26 publications. It is followed by Wiley Online Library with thirteen reports, Springer Nature with eight reports, MDPI with five reports, and Taylor & Francis with a single report. These findings suggest that Elsevier is the most significant publisher in terms of relevance to the themes of this review, followed by Wiley Online Library, Springer Nature, MDPI, as well as Taylor & Francis.

Table 9.

The number of reports found from each relevant journal along with the publisher.

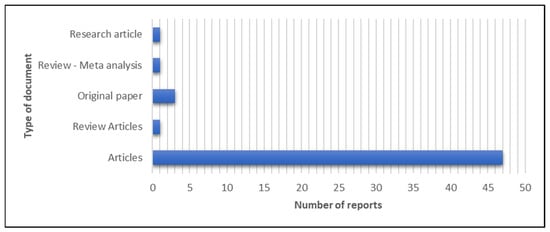

3.4. Types of Documents

The types of documents retrieved in this study provide insight into the credibility and readability of the reports. As shown in Figure 7, most of the reports retrieved are articles, comprising 47 of the total publications. These are followed by original papers with three reports. The remaining types of documents, including research articles, meta-analysis reviews, and review articles, each account for one publication. The use of these document types enhances the clarity and comprehensibility of the results, ensuring ease of understanding for readers.

Figure 7.

Graph showing the number of different types of documents included in the review. Source: Synthesis data (2025).

3.5. Indigenous Leafy Vegetables Documented

Indigenous leafy vegetables (ILVs) play a vital role in supporting livelihoods due to their significant nutritional and health benefits. Table 10 highlights the various ILVs documented in the included reports.

Table 10.

Indigenous leafy vegetables cultivated with its relevance across the SSA region.

3.6. Challenges in ILV Cultivation

This review outlines the different cultivation challenges that are associated with the cultivation of ILVs. These challenges stem from the natural/environmental, social, economic, technological, knowledge, and policy factors as outlined in Table 11. The following is a dissemination of results and how they pose as a challenge.

Natural challenges significantly impact agricultural productivity. These challenges often stem from climatic factors, such as fluctuations in temperature and precipitation, including rainfall patterns [24,34,35,36]. Climate uncertainty, linked to long-term global warming, further exacerbates these challenges [37,38,39]. Another critical concern is the perishable nature of agricultural products, which complicates price evaluations and market stability [40]. Effective natural resource management is essential for mitigating the risks posed by these uncertainties in production [41]. Among the key resources influencing agricultural outcomes are soil type [40] and soil fertility, which are vital for the nutritional quality of vegetables [42,43,44]. The varying weather conditions and management practices across different regions often result in distinct agricultural outcomes [45].

Social challenges are an inherent part of daily life and can lead to either positive or negative outcomes. One of the most pressing issues is food security, which is influenced by farm intensification and the modernization of agricultural product market channels. These changes can contribute to increased agricultural productivity [34]. This creates an opportunity for government intervention to protect public interests in food security, along with fostering the development of research communities [46]. Local cooperatives and farmer groups play a critical role in ensuring that households can access necessary inputs and markets, while also supporting one another [47]. However, challenges such as poor information sharing, language barriers, and fear of technology in smallholder communities limit the flow of knowledge needed for vegetable cultivation [48]. Additionally, land tenure systems are often seen as a significant constraint in farming [49]. Cooperatives, due to their geographical and organizational advantages, also serve a vital role in providing in-depth technology training within rural communities [50].

Azadi, et al. [46] emphasize the importance of increasing farmers’ income to alleviate poverty and enhance food security. Direct participation in agricultural activities contributes to higher food income, which improves food access and boosts the overall income of existing farmers, indirectly enhancing food stability. However, limited market access prevents farmers from generating sufficient income to ensure long-term sustainability [51,52]. This challenge is often influenced by natural factors such as climate variability [53], soil erosion, and land degradation [54], which are major drivers of food price and supply fluctuations. Issues within the market include consumer preferences [24], property rights or land tenure systems [55], credit access [47], and nutritional deficiencies [35]. Smallholder farmers often underutilize agricultural inputs due to economic constraints, such as the absence of financial markets, uninsured risks, and high transportation and transaction costs [40,56,57]. Household income and consumption are also influenced by these economic challenges [58]. In some cases, farmers lack knowledge about market operations [59], which is unlike market-oriented farmers who base their decisions on economic factors [33,42]. Competition also plays a role for market-oriented farmers [60], as does limited access to high-quality seed sources [36]. This highlights the importance of integrating biodiversity with agriculture, which is beneficial for improving food production, ecosystem health, and achieving economically sustainable growth [32].

Krone and Dannenberg [61] argue that technology plays a crucial role in supporting farmers by addressing several constraints they face. This signifies that knowledge in farming is essential for successful innovation and productivity. However, farmers in SSA face persistent challenges such as limited access to inputs and advanced farming techniques, which can be overcome through the promotion of technology adoption [24,35,46,50,51,62]. Information and Communication Technology is identified as a major driver of agricultural output, both in the short and long term [48,55]. It can provide farmers with tools for better planning and overall management [63], making it easy for incorporation to markets and the sharing of knowledge. However, its effectiveness depends on farmers’ literacy, resources, and willingness to adopt [59]. Extension services often lack capacity to tailor information to local needs [60], restricting knowledge transfer and skills development [64]. Additionally, extension services frequently lack the resources to tailor available materials and knowledge to local contexts and address the specific issues farmers face [65]. This restricts farmers’ ability to operate machinery [41,56], predict climate impacts [37], engage in digital communication [48,61], analyze soil [43], and manage irrigation systems [59]. Understanding the constraints and local knowledge surrounding farming practices is crucial for designing effective extension services, agricultural policies, and interventions tailored to specific geographical contexts [54]. Laube, et al. [40] show that when farmers are empowered with knowledge, such as the practice of Sustainable Groundwater Irrigation (SGI), they can independently drive innovation and productivity

Policy plays a crucial role in promoting sustainable farming by providing small-scale farmers with the necessary inputs and knowledge. One of the primary challenges for policymakers is understanding the extent to which smallholder farmers commercialize their operations and how to strengthen the linkages between these farmers and agricultural input suppliers and processors [51]. It is essential for policymakers to plan for a future without hunger [46]. However, Leeuwen [49] highlights that policymakers’ uncertainty regarding decentralization adds complexity to defining land-governance responsibilities at the local level. Also, Munyua and Stilwell [41] emphasize that those involved in policymaking for small-scale farmers should document both successes and failures in integrating local and external agricultural knowledge. This documentation would provide valuable insights for enhancing current Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strategies [45].

Table 11.

Different challenges associated with ILV cultivation.

Table 11.

Different challenges associated with ILV cultivation.

| Factor | Challenge | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Natural and Environmental | Climate change impacts; soil erosion and organic matter; pests and disease outbreaks; water availability; land degradation and production. | [34,36,37,40,42,43] |

| Social | Food insecurity; low resilience of rural households; lack of land ownership; limited training opportunities; and awareness of sustainable practices. | [34,46,47,48,49,50] |

| Economical | Limited market access; lack of supplier reliability; lack of financial resources and infrastructure; and high input costs. | [24,32,35,36,42,46,51,53,54,55,56,58,59,60] |

| Technological and Knowledge | Lack of technological/ICT knowledge, availability, and adoption. | [24,33,35,48,50,55,57,59,60,63,66] |

| Policy | Policy ineffectiveness; land tenure insecurity; lack of enforcement; and limited access to agricultural extension services. | [41,45,46,49,51] |

Source: Synthesis data (2025).

3.7. Contribution to Food Security and Income Generation

Indigenous leafy vegetables are of great importance as they have the potential to eradicate hunger through consumption and sale. The consumption of these vegetables promotes food security and the sales obtained increase the generation of income, thus increasing the accessibility of food. Table 12 below shows the different findings from included reports that disseminate the food security and income contribution of cultivating and utilizing ILVs.

3.7.1. Food Security

Food security is one of the measures of socio-economic development and has been a topic of discussion from the last century. This measure consists of four dimensions, namely availability (production and reserve volumes of food within an area), accessibility (economic and physical means to obtain food), utilization (use of food), and stability (consistent access of food). In addition to these dimensions, the nutrient composition and diversity of food is crucial as it also ensures that nutrition security which is closely related to food security.

Food availability is a key component of food security, ensuring that all populations have access to adequate, diverse, and nutritious food. The cultivation of ILVs plays a significant role in ensuring food availability, as many households prefer farming over other forms of employment [51]. ILVs offer a wide range of cultivars, as seen in the case of Amaranth cultivars, which cater to farmers’ preferences [24]. These cultivars thrive under various conditions and meet different farmer goals, whether related to yield or nutrition. The cultivation of ILVs is often associated with organic farming practices, which could contribute to improving the livelihoods of small-scale farmers [65]. The importance of ILVs to food security, combined with their intensive production practices, makes them an ideal model for examining economic and climate trade-offs in farming management strategies [42]. However, challenges such as the availability of quality seeds [36] and soil erosion [44] hinder the growth and availability of these crops. Despite these challenges, the production of ILVs remains one of the most effective methods to enhance agricultural productivity and, by extension, increase food availability [46].

Access to adequate food is a crucial step in achieving food security [67]. However, it is influenced by various factors that can limit its contribution to household food security, including demographics, income, and access to agricultural inputs [31,66,68]. Indigenous leafy vegetables, however, can be easily intercropped with other crops, increasing the number of crops grown and, in turn, making food more accessible [35].

Food utilization, another key pillar of food security, ensures that the food consumed provides necessary nutrients for a healthy and active life, complementing food availability and access. In this context, ILVs are utilized through both consumption and sales [58]. One of the primary reasons these vegetables are utilized is their potential to positively impact nutritional status, thereby enhancing human productivity [32]. Improvements in the utilization of ILVs have been found to significantly improve food security status, even more so than poverty status. These findings suggest that ILVs can play a vital role in enhancing agricultural productivity and food security for households [55].

Food stability refers to the preservation of food for future and sustained use. Indigenous leafy vegetables provide nutritious food and are well-suited for various specific food uses [36]. The stability and production of these vegetables are closely linked to factors such as the amount of land owned [49] and how the land is prepared for cultivation [53]. The relationship between farm size and production volume offers insights into how long small-scale farmers can sustain their livelihoods through farming [69]. To ensure food stability, farmers often employ proper handling techniques [70], provide insurance, and implement pest management strategies [25]. These practices help maintain the availability of food over time, supporting both immediate and long-term food security.

Crop and dietary diversity are essential for food security as they enhance access to a wide range of nutrients, helping to reduce the risk of malnutrition and improve resilience to food system shocks. This idea is supported by Ngcoya and Kumarakulasingam [27], who emphasize the importance of diversity in both crops and diets for overall food security. Mutyasira, et al. [38] further argue that crop diversity is crucial for increasing agricultural productivity, enhancing resilience in agro-ecosystems, and reducing the variability of agricultural income, especially in relation to fluctuations in production and market conditions [31]. Mulumba, et al. [45] note that the potential of traditional crop varietal diversity, including mixtures or multi-lines, to reduce pest and disease damage has not been given sufficient attention. Farmers often value market access for products they do not produce themselves, helping to diversify their diets [71]. Crop diversity is particularly important for rural livelihoods, contributing to food security and offering pathways to support farmers in maintaining mechanisms for development [30]. Additionally, it has been suggested that more focus should be placed on the sustainable intensification of local food systems, such as the cultivation of ILVs, which could help increase rather than decrease genetic resources supporting diverse food production [26].

Nutrient content is critical to food security by ensuring that available food provides essential vitamins and minerals for growth, health, and disease prevention. While crops are often regarded as the main source of nutrition, inputs such as soil [44] and fertilizers [41] are also vital for ensuring healthy plant growth. ILVs, in particular, are a valuable source of vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, contributing to the overall quality of the food consumed and supporting food security [65]. These vegetables can provide between 50% and 102% of the daily requirements of essential amino acids, such as histidine, isoleucine, lysine, threonine, and valine, for children aged six to twenty-three months [24].

3.7.2. Income Generation

The generation of income is essential for small-scale farmers to meet their daily needs. Ntshangase, et al. [72] note that small-scale farmers often lack critical infrastructure, such as fencing material, which requires additional income to acquire. Participation in the market can increase farmers’ income, which can then be reinvested in purchasing inputs or fulfilling household needs [51]. However, several challenges impact the income a farmer can generate in each production cycle. These challenges include access to quality water [40], market-based food systems and consumer preferences [26], insufficient markets, and high transaction costs [27], as well as the involvement of middlemen or agents [71,73].

On the other hand, there is a growing global demand for organically produced vegetables, creating new, lucrative markets that can generate income for small-scale farmers in African economies [33]. This presents an opportunity to bridge the income disparities highlighted by Misaki, et al. [63]. However, planting a variety of crops, rather than uniform planting, is often more costly [45]. In remote areas, agriculture is seen as the primary source of income and the main provider for various enterprises, including both farm and non-farm activities [55]. These factors demonstrate the importance of market access, infrastructure, and diversification in boosting the income of small-scale farmers.

Table 12.

Contribution of ILV cultivation and utilization towards food security and income generation for small-scale farming households.

Table 12.

Contribution of ILV cultivation and utilization towards food security and income generation for small-scale farming households.

| Contribution | Source | Summary of Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Food availability | [24,36,42,44,46,51,65] | ILVs increase the availability of food, thus contributing to food security |

| Food accessibility | [31,35,66,68] | ILVs are easily accessible as they grow anywhere and can withstand harsh climatic conditions |

| Food utilization | [32,55,58] | These ILVs promotes the utilization of food, assisting farmers to overcome the issue of food insecurity. |

| Food stability | [25,36,49,53,69,70] | These vegetables help enhance the production of food for farming families during unfavourable conditions. |

| Crop/dietary diversity | [26,27,30,31,38,45,71] | ILVs are diverse and can be incorporated to diets in many ways which poses a positive influence on the dietary diversity score of a household. |

| Nutritional content | [24,41,44,65] | ILVs are a source of diverse nutrients, offering both nutrition and health benefits. |

| Income generation | [26,27,33,40,45,51,55,63,71,73] | These crops increase the presence of nutritious foods, thus promoting its compatibility for market inclusion. Moreover, ILVs have a growing market demand, contributing to the generation of income. |

Source: Synthesis data (2025).

4. Discussion

This review included 53 reports in which 13 of the reports were published in 2018. The area where most studies were conducted is Kenya with nine (9) reports. The publisher with the most reports included in this review was Elsevier with 26 publications. Forty-seven (47) of these reports are articles with others being reviews or original paper. Results from this review reveal that the documented ILVs include Amaranthus spp., Vigna Ugnicuilanta, Cleome gynandra, Solanum nigrum/Solanum scabrum, Moringa oleifera, Brassica spp., and Ipomoea batatas. However, several challenges pose a threat towards their cultivation and utilization, which threatens the farmer’s ability to be food secure and generate income for sustaining livelihood. This review therefore selected these 53 reports to investigate the food and income contribution of ILV cultivation and utilisation by small-scale farming households in Sub-Saharan Africa in two decades.

The ILVs identified possess key characteristics that make them essential in addressing food insecurity. For smallholder farmers, these vegetables are not only a vital source of food and nutrition but also serve as high-value crops that contribute to income generation [74]. Each ILV contains a variety of nutrients that are fundamental for health and well-being [75,76]. Incorporating these vegetables into diets can significantly improve both nutritional intake and food security. However, despite their considerable potential, several challenges persist that limit their widespread cultivation and use. These challenges can be grouped into five categories: (1) natural and environmental factors, (2) social factors, (3) economic factors, (4) technological factors, and (5) knowledge-related factors. Each of these categories presents specific challenges that hinder the effective utilization of ILVs.

Natural and environmental factors significantly affect the cultivation of ILVs, including climate change, pests and diseases, land degradation, and water availability. Climate change has increased the frequency of extreme weather events, such as droughts, floods, temperature fluctuations, and changes in atmospheric conditions like carbon dioxide and ozone levels, which negatively impact vegetable crop yield and quality [77]. Pests and diseases can slow or halt growth, with unchecked infestations potentially leading to wilting and stunted development [78,79]. Land degradation, driven by rising cultivation intensities and climate change, results in the loss of arable soil suitable for cultivation [80,81]. Water scarcity is another critical issue, particularly in remote areas where the competition for water from more water-intensive crops limits the availability for ILVs, leading to lower yields [82]. These environmental challenges, which are largely beyond the control of small-scale farmers, leave them vulnerable to uncertainty, as they often lack access to advanced technologies that would allow for sustainable crop management and yield predictions.

Social factors such as household resilience, food insecurity, land tenure, illiteracy, language barriers, and limited access to training and awareness of sustainable practices play a crucial role in shaping agricultural dynamics and food security. These factors highlight the importance of land and labour availability, as well as agricultural knowledge, in influencing household food production and resilience, which are increasingly important in current policy discussions [18]. Addressing these factors is essential for combating food insecurity and ensuring proper nutrition. According to Yar and Yasouri [83], rural residents’ lack of awareness about sustainable development methods, low levels of knowledge, and widespread illiteracy contribute to challenges such as limited participation in farming and market activities. Language barriers further hinder farmers’ ability to communicate with consumers in the market [84]. Additionally, limited land availability and ownership threaten the preservation of various species, impacting biodiversity and food and nutritional security [85]. Bokelmann, et al. [86] emphasized the critical role of land in accessing credit, as land often serves as collateral. Moreover, the lack of training opportunities for farmers hinders their ability to improve yields. Training helps farmers develop a better understanding of farming practices, pest management, and technology adoption [87]. Supporting farmers through training and the normalization of sustainable development practices can significantly enhance food security and improve the well-being of marginalized communities [88].

Several economic factors affect small-scale farming households, including farm income, market access, and participation in markets. Mayekiso [6] points out that farm income and the employment status of the household head negatively influence the use of ILVs as a source of income or food, which is a significant issue in South Africa, where rural communities often face high levels of poverty and malnutrition. ILVs have been identified as an alternative vegetable source that can help alleviate food insecurity at the household level. In terms of the commercial viability of indigenous crops, Shelembe, et al. [12] found a link between the sale of these crops and food insecurity. Their study also revealed that households selling indigenous crops through formal markets are more likely to achieve food security than those relying on informal markets. This suggests that those primarily engaging with informal markets are at greater risk of food insecurity. Moreover, while wage and salary levels were found to have a negative but statistically insignificant impact on ILV consumption, these income variables had a significant positive effect on food security [4]. This indicates that as household wages increase, families can diversify their diets by purchasing a variety of nutrient-rich foods, such as vegetables, fruits, and proteins, thereby reducing malnutrition and improving food security within households.

Technological factors significantly influence the cultivation and utilization of ILVs by small-scale farming households, particularly in the context of technological adoption. According to Amfo and Baba-Ali [89], farmers often lack awareness of new technologies due to limited access to extension services. The adoption of such technologies could enhance farmers’ yields and provide them with information about various opportunities and strategies for improving food security and income. Additionally, embracing these technologies could enable farmers to cultivate ILVs year-round [90]. These are mostly associated with knowledge, which plays a critical role in decision-making, as it allows farmers to understand the potential outcomes of their actions. Shayanowako, et al. [91] emphasize the need to develop appropriate processing techniques for ILVs to maximize nutrient retention and extend shelf life. Knowledge of current practices and their impact on product quality is essential for developing such systems, making knowledge a vital area of focus. On the other hand, Leakey, et al. [92] argue that a participatory approach to the domestication of ILVs, where benefits flow to local communities, is crucial, especially when the traits being selected are based on traditional knowledge. This highlights the importance of knowledge, regardless of its source.

Despite the challenges faced, ILVs have the potential to significantly contribute to food security and income generation for small-scale farming households. Agriculture plays a pivotal role in supporting household resilience, sustaining livelihoods, and ensuring food security. Food security consists of four key dimensions: availability, accessibility, utilization, and stability. These dimensions can be enhanced by incorporating the nutrient content and crop diversity of ILVs, which strengthen food security elements.

Food availability refers to the amount of food produced or made accessible to farmers, consumers, and households. This dimension is influenced by numerous factors, including reliance on specific crop types [93] and socio-economic factors such as household income and expenditure on food. The irregular availability of ILVs can affect their market presence and consumer access, ultimately impacting food security [94]. Ensuring the consistent availability of these vegetables is critical for maintaining food security.

Food accessibility refers to a household’s ability to obtain available food, and ILVs are recognized as an alternative that enhances food availability and accessibility for small-scale farming households. ILVs are cost-effective and contribute to achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), making them an integral part of household food security [12]. To improve food accessibility across South Africa, the food security policy was implemented, aiming to reduce the number of people with inadequate access to food in Southern Africa [95].

Food utilization refers to how households use the food they have access to, to meet their nutritional needs. ILVs can be used in culinary dishes or incorporated into daily meals to achieve food and nutrition security [85]. However, Ogwu [96] warned that the underutilization of these vegetables could lead to their extinction, despite their potential as both food and medicinal plants. Therefore, the preservation and increased utilization of ILVs is critical.

Food stability refers to the ability to maintain access to food over time. ILVs have long been part of the food system and culture. They are often readily available, inexpensive, and improve the micronutrient quality and diversity of local diets, helping to reduce ‘hidden hunger’ and extend the availability of food, thus promoting better health [97].

Crop and dietary diversity are crucial elements in preventing both undernutrition and overnutrition, as each nutrient plays a specific role in the human body. Indigenous leafy vegetables (ILVs) contribute to a more diversified diet, providing a rich source of essential macro and micronutrients, which helps reduce vulnerability to diseases [98]. These vegetables are also highly resistant to environmental changes and can serve as an alternative for local communities during droughts or food shortages. Integrating ILVs into cropping systems promotes both crop and dietary diversity, enhancing nutrition and boosting food security for rural households. This is supported by Tanimonure, et al. [99], who concluded that incorporating underutilized ILVs into cropping systems in rural and urban areas of developing countries could address nutrition insecurity.

The nutritional content of ILVs is beneficial for health, reducing the likelihood of chronic illnesses. These vegetables are high in dietary fibre, which supports digestive health, helps maintain a healthy body weight, and reduces the risk of cardiovascular diseases and possibly colon cancer. ILVs are also rich in proteins, vitamin A, and zinc, and contribute to brain function, stress relief, optimal gut health, immune system support, and bone health [100]. Therefore, ILVs are a valuable resource for improving food and nutritional security in households [101].

Indigenous leafy vegetables are essential to the livelihoods of small-scale farming households, as they contribute to the availability, accessibility, and utility of food, thereby promoting food stability within the household. Additionally, they enhance crop diversity and nutrient retention, which supports the health of small-scale farmers [102]. ILVs not only play a critical role in food security but also have the potential to generate income. Mabuza [103] highlighted that, if properly exploited, ILVs could improve food security, nutrition, and income for rural populations.

Small-scale farming households typically produce agricultural goods for household consumption and sell surplus produce [104]. These households often sell their produce at the farm gate or participate in local markets as part of their livelihood. Imathiu [75] further emphasized that cultivating and selling ILVs provides employment opportunities, contributing to income generation. ILVs can fetch higher prices than non-indigenous crops, particularly during dry seasons, as they are more resilient to adverse weather conditions. However, Olowo, et al. [105] argued that the lack of recognition of the importance of indigenous fruits and vegetables among consumers may reduce demand, thereby lowering income and profits from these crops. Qwabe and Zwane [106] concluded that indigenous crops should be included in mainstream food discussions and recognized as a tool to enhance the livelihoods of small-scale farming households.

5. Conclusions

The overall aim of this review was to examine the food and income contributions of cultivating and utilizing indigenous leafy vegetables (ILVs) by small-scale farming households in Sub-Saharan Africa, drawing relevant insights from studies conducted over the past two decades. The review synthesized findings from 53 reports documenting various ILVs and their associated challenges in cultivation, as well as their contribution to food security and income generation.

The ILVs analyzed in this review include Amaranthus spp., Vigna unguiculata, Cleome gynandra, Solanum nigrum/Solanum scabrum, Moringa oleifera, Brassica spp., and Ipomoea batatas. The cultivation and utilization of these vegetables were found to have the potential to enhance household food security and generate income through household consumption and the sale of surplus produce. However, their cultivation faces significant challenges, which can be attributed to natural, environmental, social, economic, technological, and knowledge-related factors. Key challenges include climate change, pest and disease infestations, land degradation, water availability, land ownership issues, illiteracy, limited access to agricultural training and technology, and communication and adoption barriers. Additionally, the underutilization, stigmatization, and low recognition of these vegetables in some parts of Sub-Saharan Africa may contribute to their eventual extinction.

This highlights the need for policy intervention to promote ILV cultivation among small-scale farming households, particularly by facilitating their entry into formal markets. Improved extension services are also essential to provide farmers with training on sustainable agricultural practices, as well as to enhance their access to advanced technologies. This review strongly advocates for the promotion of ILV cultivation as a livelihood source for small-scale farmers, ensuring both food and nutrition security and generating income to meet daily household needs. Areas for future research include examining the policies governing ILV cultivation on small-scale farms. These policies can be examined by comparing the subsidy policy effects of ILV cultivation in different SSA countries and analyzing the bureaucratic barriers and farmers’ participation in policy implementation. Secondly, market supply chain analyses of ILVs available in formal markets can be conducted for tracking the intermediate links of ILVs from farmers to markets. Furthermore, the impact of supply chain efficiency on farmers’ income could be measured. Moreover, a cost–benefit analysis could provide valuable insights to help farmers understand how they can benefit from adopting ILV cultivation practices.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18031187/s1, The supporting information include the PRISMA checklist adopted from Page et al. [23].

Author Contributions

N.N., M.S. and N.Z.K. formulated the review investigation, N.N. was responsible for data collection, analysis, interpretation, and original draft preparation, and M.S. and N.Z.K. supervised, reviewed, and edited the final draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data to support the findings from this review utilized numerous databases including Google Scholar and specified databases used in this review.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge all sources of information used for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CASP | Critical Appraisal Skills Programme |

| ILV | Indigenous leafy vegetables |

| MDG | Millennium Development Goals |

| PICO | Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| SSA | Sub-Saharan Africa |

| UNIZULU | University of Zululand |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Quality testing scores for the included reports using CASP framework.

Table A1.

Quality testing scores for the included reports using CASP framework.

| Source | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [34] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 8 |

| [54] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 8 |

| [46] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [24] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8.5 |

| [35] | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7.5 |

| [65] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 05 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| [32] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 05 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| [47] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 05 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8.5 |

| [56] | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 05 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 7 |

| [68] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| [53] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| [37] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8.5 |

| [61] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8.5 |

| [59] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8.5 |

| [60] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8.5 |

| [42] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8.5 |

| [36] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8.5 |

| [58] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8.5 |

| [40] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8.5 |

| [49] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8.5 |

| [66] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8.5 |

| [50] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8.5 |

| [55] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9.5 |

| [33] | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| [57] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 05 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| [63] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 7.5 |

| [48] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 7.5 |

| [43] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 7.5 |

| [51] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 05 | 7.5 |

| [45] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 05 | 7.5 |

| [41] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 05 | 7.5 |

| [38] | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 05 | 8.5 |

| [107] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [44] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [27] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [31] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [72] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [39] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [62] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [25] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [69] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [28] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 8.5 |

| [108] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [29] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [71] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [109] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [73] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [52] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [70] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [67] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [30] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [26] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [64] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

Note: The database search and quality testing for articles used were collected in March 2025. Source: Author’s compilation (2025).

References

- Gunamoni, D. Green Leafy Vegetables of Tripura: A Case study. Pharmacogn. Res. 2024, 16, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, T.; Salauddin, M.; Roy, S.; Chakraborty, R.; Rebezov, M.; Shariati, M.A.; Thiruvengadam, M.; Rengasamy, K.R.R. Underutilized green leafy vegetables: Frontier in fortified food development and nutrition. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 11679–11733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayekiso, A.; Belete, A.; Hlongwane, J. Analysing contribution and determinants of indigenous leafy vegetables (ILVs) to household income of rural households in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. J. Agribus. Rural Dev. 2023, 67, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngidi, M.S.C.; Zulu, S.S.; Ojo, T.O.; Hlatshwayo, S.I. Effect of Consumers’ Acceptance of Indigenous Leafy Vegetables and Their Contribution to Household Food Security. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, R.; Moncur, Q. Small-scale farming: A review of challenges and potential opportunities offered by technological advancements. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayekiso, A. Exploring the Determinants of Indigenous Leafy Vegetables Utilization as a Development Strategy for Enhancing Food and Nutrition Security in Alfred Nzo District, South Africa. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2024, 25, 26707–26724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, A.R.; Zander, K.K.; Lassa, J.A. Smallholder farming during COVID-19: A systematic review concerning impacts, adaptations, barriers, policy, and planning for future pandemics. Land 2023, 12, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, G.; Wang, Z.; Maundu, P.; Hunter, D. The role of traditional knowledge and food biodiversity to transform modern food systems. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 130, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olusanya, R.N.; Kolanisi, U.; Ngobese, N.Z.; Mayashree, C. Dynamics of Amaranthus in Urban and Rural Value Chains in Communities of KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. Resources 2024, 13, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mphande, W. Research gaps in neglected indigenous vegetables in sub-Saharan Africa: A roadmap to mainstreaming. J. Underutil. Crops Res. 2025, 4, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qwabe, Q.N.; Munialo, S.; Swanepoel, F. The role of underutilized indigenous and traditional food crops in enhancing rural livelihoods and food security in South Africa. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1605773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelembe, N.; Hlatshwayo, S.I.; Modi, A.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Ngidi, M.S.C. The Association of Socio-Economic Factors and Indigenous Crops on the Food Security Status of Farming Households in KwaZulu-Natal Province. Agriculture 2024, 14, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsos, T.M.; Menexes, G.C.; Dordas, C.A. An efficient framework for conducting systematic literature reviews in agricultural sciences. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 682, 106–117. [Google Scholar]

- Gassara, G.; Chen, J. Household food insecurity, dietary diversity, and stunting in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samrgandi, N. Usability evaluation of research database websites. Life Sci. J. 2021, 18, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ocholla, D. Reflections on Trends, Challenges and Opportunities of LIS Research in South Africa. A Contextual Discourse. In Information, Knowledge, and Technology for Teaching and Research in Africa: Information Behavior in Knowledge and Economy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 161–193. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton, S.C.; Dinsmore, C.S.; Van Kleeck, D.; Ma, X. Computer-assisted indexing complements manual selection of subject terms for metadata in specialized collections. Coll. Res. Libr. 2021, 82, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nontu, Y.; Mdoda, L.; Dumisa, B.M.; Mujuru, N.M.; Ndwandwe, N.; Gidi, L.S.; Xaba, M. Empowering rural Food Security in the Eastern Cape Province: Exploring the role and determinants of Family Food gardens. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, F.; Tahir, F.; Qureshi, N.A. Millennium development goals (MDGs-2000-2015) to sustainable development goals (SDGs-2030): A chronological landscape of public sector health care segment of Pakistan. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2021, 71, 596–601. [Google Scholar]

- Ajayi, F.A.; Udeh, C.A. Review of crew resilience and mental health practices in the marine industry: Pathways to improvement. Magna Sci. Adv. Biol. Pharm. 2024, 11, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldashev, K.; Tleuov, A. Response of Local Academia to the Internationalization of Research Policies in a Non-Anglophone Country. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2022, 30, n56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Research Checklist; Critical Appraisal Skills Programme: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinssa, F.F.; Yang, R.Y.; Ledesma, D.R.; Mbwambo, O.; Hanson, P. Effect of leaf harvest on grain yield and nutrient content of diverse amaranth entries. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 236, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochieng, J.; Kirimi, L.; Ochieng, D.O.; Njagi, T.; Mathenge, M.; Gitau, R.; Ayieko, M. Managing climate risk through crop diversification in rural Kenya. Clim. Change 2020, 162, 1107–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, C.W.; Tabuti, J.R.S.; Hensel, O.; Yeh, C.-H.; Gebauer, J.; Luedeling, E. Homegardens and the future of food and nutrition security in southwest Uganda. Agric. Syst. 2017, 154, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngcoya, M.; Kumarakulasingam, N. The Lived Experience of Food Sovereignty: Gender, Indigenous Crops and Small-Scale Farming in Mtubatuba, South Africa. J. Agrar. Change 2017, 17, 480–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, N.A.; Larbi, A.; Kotu, B.; Tetteh, F.M.; Hoeschle-Zeledon, I. Does Nitrogen Matter for Legumes? Starter Nitrogen Effects on Biological and Economic Benefits of Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.) in Guinea and Sudan Savanna of West Africa. Agronomy 2018, 8, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakariyahu, S.K.; Indabo, S.S.; Aliyu, A.; Muhammad, H.U.; Ahmed, H.O.; Mohammed, S.B.; Adamu, A.K.; Aliyu, R.E. Cowpea landraces in northern Nigeria: Overview of seedling drought tolerance. Biologia 2024, 79, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, C.; Luedeling, E.; Tabuti, J.S.; Nyamukuru, A.; Hensel, O.; Gebauer, J.; Kehlenbeck, K. Crop diversity in homegardens of southwest Uganda and its importance for rural livelihoods. Agric. Hum. Values 2018, 35, 399–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noromiarilanto, F.; Brinkmann, K.; Faramalala, M.H.; Buerkert, A. Assessment of food self-sufficiency in smallholder farming systems of south-western Madagascar using survey and remote sensing data. Agric. Syst. 2016, 149, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahane, R.; Hodgkin, T.; Jaenicke, H.; Hoogendoorn, C.; Hermann, M.; Keatinge, J.; d’Arros Hughes, J.; Padulosi, S.; Looney, N. Agrobiodiversity for food security, health and income. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 33, 671–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]