Abstract

Sustainable development affects the quality of life of spatially diverse populations, and the pursuit of improved living conditions—both objective and subjective—is often associated with residential relocation. This article examines population movements from urban to rural areas outside agglomerations. Quantitative research was first conducted to assess population changes in rural areas in Poland between 2002 and 2024 and to determine the role of urban-to-rural migration in this process. The second stage consisted of qualitative research conducted among residents of selected Polish villages. The results indicate that the largest scale of migration from urban to rural areas outside agglomerations occurred in the western part of the country, particularly in the Dolnośląskie and Wielkopolskie Voivodeships, which are characterised by high levels of socio-economic development and good spatial accessibility. New residents—counterurbanists—primarily selected areas with high natural values. The decision to relocate to the countryside stemmed mainly from a desire for lifestyle change. In many cases, the opportunity to live in rural areas enabled newcomers to realise their aspirations of establishing their own businesses, which improved both their quality of life and that of the local community.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development affects the quality of life of the population, defined both by objective living conditions—reflecting material well-being [1,2,3]—and subjective personal assessments—reflecting psychological states such as satisfaction, contentment, and happiness [4,5,6]. Place of residence plays a crucial role in the assessment of quality of life [7,8,9]. A change of place of residence is closely related to the phenomenon of migration, which has attracted the interest of scholars in economics [10,11], sociology [12,13], and geography [14,15]. Migration can be treated either as a consequence or as a cause within the chain of interconnections between population and environment [16]. The reasons for population mobility over time are most effectively explained by Everett Lee’s push–pull theory [12,17]. Migration decisions are made based on a comparison of the characteristics of the place of origin and the destination. The place of origin is usually well known to the individual, whereas the assessment of a potential destination is characterised by considerable imperfection in the available information and, consequently, a high degree of uncertainty (as a result, pull factors must be relatively more convincing) [18]. Each place is characterised by a specific set of features, which makes the decision to relocate highly subjective. It results from a range of individual preferences of the potential migrant, who seeks to maximise their own expectations. The dominant migration trend in the rural–urban direction has traditionally been associated, among other factors, with improvements in material living conditions, such as labour market opportunities, higher income, and housing standards [19]. In contrast, migration from cities to rural areas—referred to as counterurbanisation [20]—is primarily driven by a desire to improve quality of life, including aspects related to the natural and socio-cultural environment [21,22,23]. At the same time, it is important to note that individuals relocating from cities to the countryside often seek a balance between urban and rural amenities [24,25]. As a result, urban out-migration manifests in two characteristic spatial forms: suburban areas [17] and rural areas located outside agglomerations [26,27,28,29]. In the context of residential relocation motives, it should be emphasised that migration from cities to rural areas first emerged in highly developed countries [26,30]. Counterurbanites select distinct locations for residence based on a combination of tangible attributes (e.g., clean air and water, natural diversity, recreational opportunities) [31] and intangible factors (e.g., escape from personal and/or social burdens of everyday life) [32]. This phenomenon was first identified on a large scale in North America [33,34,35]. In Poland, interest in migration from cities to rural areas has been increasing for at least two decades. Research has primarily focused on migration to suburban areas, often analysed in a socio-cultural context, including perceptions of rural space, relationships and social ties between different groups of inhabitants, and cultural diversity [36,37,38], as well as ongoing spatial, functional, and demographic changes in suburban zones [39,40]. By contrast, migration from cities to rural areas located outside agglomerations remains relatively under-researched. Existing studies have addressed this phenomenon mainly within broader analyses of migration processes [41], while counterurbanisation itself has been examined in more detail in selected works [42,43,44,45]. Accordingly, the analyses presented in this article address an important research gap in studies on rural counterurbanisation in Poland and contribute to the broader discussion on rural development shaped by urban migrants, particularly through insights derived from qualitative data. An additional contribution of this study lies in its consideration of counterurbanisation as an opportunity for local policy, offering a contemporary perspective on migration and development.

The aim of this article is to characterise the directions and scale of counterurbanisation in rural areas outside agglomerations, to identify the socio-demographic profile of individuals migrating to the countryside, and to determine the reasons for selecting rural areas as a place of residence. In particular, the study seeks to answer the following research questions:

- What were the dynamics of population change in rural areas between 2002 and 2024?

- What role did counterurbanisation play in this process, and did it exhibit a spatial dimension?

- Who were the migrants relocating from cities to rural areas outside agglomerations, and what factors contributed to their decision to change their place of residence?

The authors argue that addressing this research problem facilitates a better understanding of the factors shaping contemporary transformations of settlement structures and their implications for local development, as well as spatial and social policy. In addition to Section 1, the article comprises the following sections: Section 2 (spatial and temporal scope of the research, data sources, and research procedure), Section 3 (main empirical findings), Section 4 (interpretation of results in relation to previous studies), and Section 5.

2. Materials and Methods

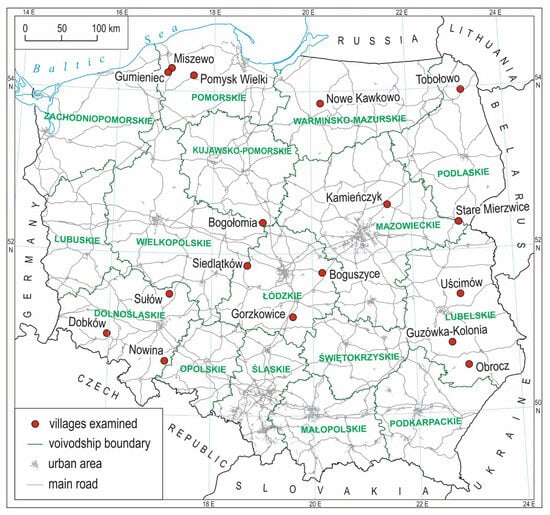

The aim of the study defined the research area, which included rural areas in Poland, understood as rural communes and the rural parts of urban–rural communes, excluding communes classified by the Central Statistical Office (CSO) as agglomeration areas [46]. As a result, the spatial analysis covered 1769 municipalities. During the research process, this scope was further refined to 17 villages located in six voivodeships (Figure 1). The selection of villages was guided primarily by the specificity of their functional and spatial structure, identified during field observations. Rural units were selected in which intensive development was evident, as indicated by the share of newly developed building plots, accounting for approximately 20–50% of all developed settlement plots within a village. Particular attention was also paid to villages located outside the so-called agglomeration belts. The selection of villages, taking into account their genetic and structural characteristics, enabled the observation of processes occurring in statu nascendi. This was particularly important for social research, as it allowed for the collection of information that had not yet faded from participants’ memories. It was also essential that the transformation process had already reached an advanced stage of implementation and that participants possessed a certain body of experience. An additional criterion for village selection was the presence of local social environments composed of both newly arrived and long-established residents, who observed one another and potentially influenced their satisfaction with their place of residence (living environment). Accordingly, villages were selected in which noticeable changes in social structure had occurred, reflected in an increasing share of residents who had been living in the village for a relatively short period. Furthermore, the selection of study locations was influenced by the researchers’ familiarity with the local context and long-term accessibility to the study areas.

Figure 1.

Research area. Source: authors’ elaboration based on [47].

The part of the study that examined population changes in rural areas and the extent to which urban-to-rural migration influenced this process between 2002 and 2024 used statistical data from the Central Statistical Office in Poland [47]. The part of the study addressing the motivations underlying decisions to relocate from urban to rural areas drew on interviews conducted in 2023–2024. In particular, the research focused on identifying the motives that prompted new settlers to move from cities to the countryside using a standardised survey questionnaire. A total of 419 residents of the selected villages who had relocated at least five years prior to the study were surveyed. Due to difficulties in recruiting participants, the study employed convenience sampling. Furthermore, to complement and deepen the questionnaire-based research, open-ended interviews were conducted using a standardised list of guiding questions with purposively selected representatives of the studied rural communities. This group included individuals holding important positions within their communities, such as representatives of Local Action Groups, local entrepreneurs, and community leaders (local witnesses) promoting local rural capital. This group consisted of 40 participants and was selected using the snowball sampling method, based on local residents’ opinions regarding community leaders. A relatively small number of respondents was selected in each village, as the objective was to examine the phenomenon in greater depth rather than breadth.

This article addresses selected issues related to the impact of counterurbanisation on rural areas outside agglomerations. The research problem largely aligns with the socio-cultural approach to rural geography. Accordingly, the study adopted a mixed-methods research design, combining quantitative and qualitative data. This approach enabled a broader contextual analysis while simultaneously allowing for a deeper exploration of respondents’ motivations, opinions, and experiences. Therefore, the case study method was applied as the primary research strategy, as it facilitates a comprehensive explanation of phenomena shaping the character of the studied units (e.g., village, region, city). Owing to the use of field observation and engagement with individual cases, case studies rarely leave researchers indifferent to the reality they investigate and interpret. This often creates a connection between what is being discovered—the object of study—and the discoverer, i.e., the researcher engaged in understanding what they experience. In the authors’ view, the subject matter required such an in-depth approach, as the geographical perspective adopted here necessitated integration with concepts derived from human geography. The aim was to capture and present a broader reflection on the role of the countryside as a place of residence in shaping the living conditions and quality of life of new settlers.

The process of population migration from urban to rural areas and the reasons underlying these decisions were examined using a research procedure consisting of the following stages:

Quantitative Research Stage:

- Step I:

- Literature Analysis and Selection of Statistical Indicators.

- Step II:

- Determining the migration trend between 2002 and 2024 based on its direction (a—rural-to-urban migration; b—migration from urban to rural areas; c—migration from urban to urban; d—migration from rural to rural areas).

- Step III:

- Identifying population changes in rural areas and the impact of urban-to-rural migration on these changes based on statistical data (dynamics of population change—percentage share) and registration in rural areas from cities (in absolute numbers and per 1000 inhabitants) and their spatial distribution, and examining existing relationships.

Qualitative Research Stage:

- Step IV:

- Preparing a questionnaire based on the literature to identify the factors influencing the decision to relocate from urban to rural areas outside agglomerations.

- Step V:

- Conducting interviews (field research) and analysing the obtained results.

The results presented in this article are derived from a multidimensional research project conducted in several stages between 2022 and 2025 as part of the National Science Centre project entitled Urban–Rural Knowledge Transfer–Models of Interdependence.

3. Results

3.1. The Geography of Counterurbanisation

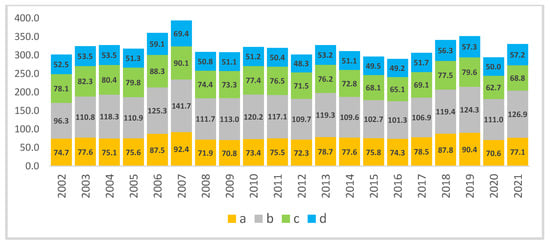

In Poland, for at least two decades, there has been a growing interest in population movements from cities to rural areas, and this trend has increasingly extended not only to rural areas within agglomeration catchment zones but also to rural areas located outside agglomerations. Based on statistical data, between 2002 and 2021, this movement involved nearly 2.3 million people and accounted for almost 36% of all internal population movements in Poland during the analysed period (Figure 2). According to estimates by the Central Statistical Office in Poland, approximately 2 million people are expected to move from cities to rural areas by 2035 [47].

Figure 2.

Internal migration in Poland by direction of permanent residence, 2002–2021 (thousands). Note: a—rural-to-urban migration; b—urban-to-rural migration; c—urban-to-urban migration; d—rural-to-rural migration. Source: authors’ elaboration based on [48].

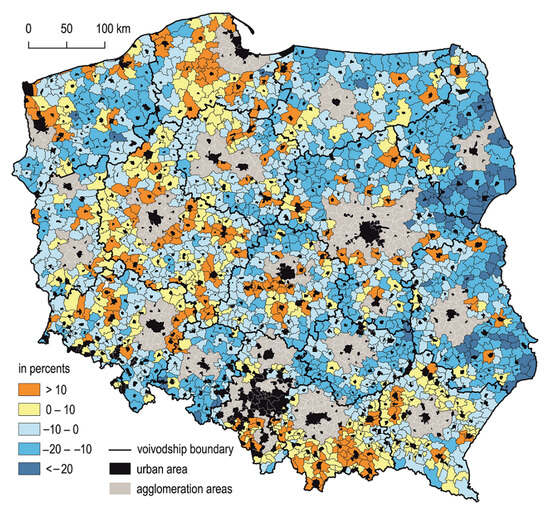

An analysis of population change dynamics between 2002 and 2024 in rural areas outside agglomerations revealed significant spatial variation (Figure 3). Municipalities experiencing population growth were concentrated primarily in the Wielkopolskie Voivodeship (42 municipalities, representing 68% of the total) and the Małopolskie Voivodeship (39 municipalities, representing 52% of the total). An examination of the spatial distribution of these municipalities indicates that, in the Małopolskie Voivodeship, population growth resulted from the strong influence of the Kraków agglomeration and the proximity of the Tatra Mountains, characterised by high natural values In the Wielkopolskie Voivodeship, population growth was recorded not only in municipalities located near the Poznań agglomeration but also in municipalities situated in peripheral areas near the voivodeship borders. Voivodeships in which significant population decline affected over 90% of municipalities included the Świętokrzyskie, Lubelskie, and Podlaskie Voivodeships. Particularly noteworthy are the Podlaskie and Lubelskie Voivodeships, which recorded the highest numbers of municipalities—26 and 24, respectively—experiencing population declines exceeding 20%. These voivodeships are located along Poland’s eastern border, which also constitutes the external border of the European Union. By contrast, in the Lubuskie and Podkarpackie Voivodeships, more than 75% of municipalities experienced either population growth or population decline not exceeding 10%.

Figure 3.

Population changes in non-agglomeration rural municipalities in Poland, 2002–2021 (%). Source: authors’ elaboration based on [47,48] (accessed 21 July 2025).

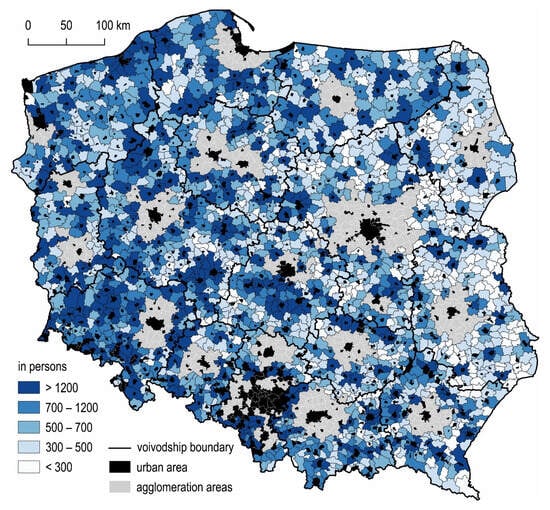

The largest scale of migration from urban to rural areas outside agglomerations was observed in western Poland (Figure 4). The results indicate that municipalities receiving an influx of more than 1200 urban residents accounted for 19% of all municipalities included in the analysis. These municipalities were concentrated primarily in the Dolnośląskie and Wielkopolskie Voivodeships. By contrast, an influx of fewer than 300 urban residents was recorded in 16% of municipalities located in the Lubelskie, Podlaskie, and Mazowieckie Voivodeships, forming a compact spatial pattern in eastern Poland.

Figure 4.

Urban registrations in rural non-agglomeration municipalities in Poland, 2002–2021 (persons). Source: authors’ elaboration based on [49] (accessed 21 July 2025).

A Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.690 was identified between the population change index for 2002–2021 and the influx of urban residents into rural areas outside agglomerations, indicating a significant relationship between these variables. At the voivodeship level, the strongest correlations between these indicators were observed in the Wielkopolskie (0.812), Mazowieckie (0.805), and Warmińsko–Mazurskie (0.796) Voivodeships.

3.2. Motives for Migration: Quality of Life in the Countryside?

In the studied group of migrants relocating from cities to the countryside, middle-aged individuals (40–59 years) predominated, accounting for 41.0% of respondents, followed by younger adults aged 26–39 years (24%). Within this group, 64.0% of respondents relocated to the countryside from large cities, defined as urban centres with populations exceeding 100,000. Among newly arrived rural residents, 52% reported having completed higher education, while nearly 40.0% held tertiary-level qualifications.

The analysis of respondents’ motivations for relocating to the countryside revealed a dominant theme associated with the rural idyll and a positive, traditional vision of rural life, which the literature classifies as amenity migration. This reflects the fact that, to a large extent, decisions to relocate to the countryside were driven by non-material factors. The desire to experience nature and traditional agriculture, achieve a higher quality of life in a natural setting, gain access to organic food, and adopt a healthy lifestyle were particularly significant factors motivating relocation to rural areas. This is evidenced by the statement of a respondent: “I have been living here for about 7–8 years. […] I came from France, where everyday life is burdened by functional and ecological constraints. In Poland, I established an organic farm without fertilisers or pesticides. Initially, it was for personal use, but over time it expanded, and I now sell the products […]”.

Lifestyle changes experienced after relocation to the countryside, combined with respondents’ understanding of the local labour market, often led them to establish their own businesses Prior to relocation, respondents were employed in a range of institutions, including banks, television stations, schools, and international corporations. Survey results indicate that living in the countryside opened up new opportunities, enabling respondents to pursue aspirations related to self-employment. The respondent group also included individuals who continued to operate businesses in the cities from which they relocated, such as a lawyer, a photographer, and owners of insurance or construction companies. As a result, approximately one in three counterurbanites was self-employed. The examples of the integration of rural-specific attributes with respondents’ skills and passions following relocation include the establishment of enterprises such as agritourism facilities offering accommodation, horseback riding, and organic meals (“Ptasi Folwark”), therapeutic activity centres (“Alpaki-Cudaki”), Border Collie breeding, lavender production (“Living Museum of Lavender”), and artisanal pottery workshops (“Cegielnia Artystyczna”). The following statements confirm how the move to the countryside affected the lives of the respondents:

“About ten years ago, I decided to change my life. […] I am a trained psychologist, and while working at a children’s support centre […] I realised that contact with animals greatly helps children with difficulties. I wanted to establish my own therapeutic centre for children, and I managed to do so, although the beginnings were not easy.”

“I had owned a plot of land in […] for a long time, but I decided to become a permanent resident about 6–7 years ago, once it became possible to work outside the city. Professionally, I provide media services […], and my hobby—which also generates income—is breeding Border Collie dogs.”

“My parents moved here in the 1970s after studying in Warsaw. […] I lived in the UK for some time, where I studied art, but I did not want to stay there. I returned to Poland and currently work in agritourism and ceramics, running workshops and selling ceramic products.”

It is worth emphasising that through their activities, newcomers influence the quality of life of long-established village residents. First, newcomers primarily utilise local natural and social resources, thereby influencing local labour markets and generating added value within rural environments. Their activities often offer jobs and shape new, informal networks of social contacts and exchanges, which may in the future lead to new economic activities. Second, they actively seek to strengthen and enhance the communities in which they operate. The nature of their entrepreneurial activity also indicates the need for their active involvement in the local community and, at the same time, the cultivation of activities traditionally connected to the village and its traditions. Examples of such initiatives include the establishment of the Museum of History and Tradition, or the establishment of the “Rękodzieło” Association operating at the Lavender Living Museum.

Although respondents’ individual migration narratives and motivations varied, a recurring theme was the need for freedom, frequently contrasted with the perceived constraints of urban life. As one respondent stated:

“The countryside is freedom. […] Contrary to appearances, even though you live in a small and relatively closed community, rural life offers more freedom than the city. […] In the countryside, life follows a different rhythm; it is more tangible and more conducive to living.”

This perception was often accompanied by a critical assessment of urban systems and norms, as reflected in another respondent’s statement:

“The city creates culture and new ideas, but it poisons itself with these ideas and, in the process, destroys people’s lives. The city is noisy and tense; everything must be done immediately. It is a kind of unhealthy organisation. In the countryside, life is different—it follows a different rhythm. It is more concrete and more conducive to life.”

4. Discussion

The discussion of counterurbanisation occupies a prominent place in geography [29,43,50], sociology [34,51], and urban studies [52,53]. The discussion of counterurbanisation occupies a prominent place in geography [29,43,50], sociology [34,51], and urban studies [52,53]. The course of the counterurbanisation process, including its pace and intensity, varies considerably across European countries [54,55]. Classic counterurbanisation in Western Europe was already pronounced in the 1970s–1980s and involved population outflows from city centres to smaller towns and villages, often at distances exceeding 50 km from metropolitan cores [26,56]. At the same time, the differentiation of counterurbanisation effects depended on the spatial distribution of socio-economic disparities between northern and southern regions, commonly referred to as the “north–south divide.” In contrast, in Poland and other Central and Eastern European countries, tendencies toward the deconcentration of population and economic activity—from urban centres to metropolitan outskirts and from metropolitan to non-metropolitan areas—emerged much later [54]. Compared to Western European countries, counterurbanisation in Poland remains less intense and is largely characterised by periurbanisation, with migration from cities primarily affecting suburban areas rather than remote villages. Migration is predominantly short-distance and directed mainly toward suburban zones surrounding large agglomerations such as Warsaw, Kraków, Wrocław, and the Tricity. This process has not yet resulted in substantial changes in rural real estate markets, with limited price increases observed mainly in suburban areas of large cities [57]. In Poland, the economic impact of counterurbanisation remains limited, whereas in Western and Southern Europe it plays a more pronounced role in shaping local real estate markets and demographic structures. Three waves of counterurbanisation can be identified in Poland. The first wave emerged in the second half of the 1970s and was associated with initiatives that later influenced broader socio-cultural and economic development processes. This wave involved artistic communities that relocated festivals, workshops, and art exhibitions to rural spaces, free from institutional and commercial constraints. The second wave of migration, associated with the early 1990s, stemmed from a fascination with organic farming and agritourism [58]. This wave reflected a desire to protect traditional ways of life and local cultural identities. The third wave of migration, which began in the 1990s and continues to the present, includes individuals with clearly articulated values who consciously reject consumerist lifestyles [38]. Given the focus of this study, the authors concentrated on the most recent wave of migration, associated with lifestyle changes frequently driven by quality-of-life considerations. The results of this study indicate that the largest population growth in rural areas outside agglomerations occurred primarily in western Poland (Wielkopolskie and Małopolskie Voivodeships), while population decline predominated in eastern Poland (Lubelskie and Podlaskie Voivodeships). This spatial pattern reflects historical conditions associated with levels of socio-economic development [59,60,61]. Voivodeships located along Poland’s eastern border are characterised by less favourable demographic and economic structures compared to other regions of the country, as well as a low level of technical infrastructure, which translates into poor quality of life for the population [62,63,64]. As a result, these challenges tend to accumulate, generating additional costs for residents seeking to maintain an adequate standard of living.

In response to the second research question, the study demonstrates that counterurbanisation in Poland is spatially differentiated. The highest influx of urban migrants was recorded in the voivodeships that experienced the greatest population growth between 2002 and 2021, namely Dolnośląskie and Wielkopolskie. Compared to other regions of the country, these voivodeships are characterised by high levels of socio-economic development [59] and good transport accessibility [65]. Living in communes located outside urban cores within these voivodeships allows residents to combine proximity to nature with a high quality of life, without compromising access to social and technical infrastructure. Pearson correlation analysis revealed a strong relationship between population change in rural areas and the influx of urban migrants during the analysed period, particularly in the Wielkopolskie Voivodeship. This finding is consistent with previous research and was also observed, notably, in the Mazowieckie and Warmińsko–Mazurskie Voivodeships. These patterns can be attributed in part to population outflows from Poland’s largest metropolitan area, Warsaw, the national capital. Such decisions may be motivated by a combination of spatial accessibility and high natural amenity values. Living in municipalities located on the periphery of the Mazowieckie Voivodeship enables residents to benefit from rural living conditions, resulting from a higher quality natural environment and lower living costs, while still being well-connected to Warsaw. Choosing a village in the Warmińsko–Mazurskie Voivodeship is associated with relatively limited transport accessibility compared to other regions of the country, but also with exceptionally high natural amenity values [66]. This voivodeship is commonly referred to as the “land of a thousand lakes,” reflecting its distinctive natural landscape [67]. Moreover, the desire to reside in rural areas became particularly pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic. State measures aimed at limiting the spread of COVID-19 significantly disrupted migration mechanisms and exposed existing inequalities and forms of exclusion affecting migrants [68]. The COVID-19 pandemic led to a significant decline in daily urban mobility flows and constrained migration related to work and education [69]. The continuous presence of household members in confined residential spaces often intensified domestic tensions. As a result, many individuals sought opportunities to acquire housing offering greater privacy and comfort. The COVID-19 pandemic intensified population movements toward rural areas, which increasingly functioned as refuges for urban residents [70]. Consequently, urban-to-rural migration increased, producing measurable demographic effects in small towns and rural settlements [71].

Addressing the research question of who migrated from cities to rural areas outside agglomerations and what motivated their relocation aligns with the concept of rurality, often framed as the rural idyll [50,72,73,74]. The image of the countryside remains strongly embedded in the minds of urban residents, perceived as a place that is healthier, more affordable, and conducive to fulfilling the long-postponed aspiration of property ownership [43]. The Central Statistical Office rarely publishes real estate prices for administrative units smaller than counties. However, an analysis of real estate transaction dynamics indicates that urban areas clearly outperform rural areas in terms of prices [57,75]; as of September 2025, the highest indicative prices were recorded in Warsaw, ranging from PLN 16,400 to PLN 18,700 per square metre, while prices in rural areas ranged from PLN 4500 to PLN 8500 per square metre [76]. As previous studies have shown, migrants who decided to relocate to the countryside were primarily united by the desire to improve their quality of life, associated with the opportunity to live in a natural environment and gain access to organic food. The interviews indicate that the pattern described in the literature—according to which lower-level needs are satisfied before higher-level ones [77]—also applies to the studied group of respondents. Urban dwellers who chose to settle in the countryside were characterised by high levels of education and professional experience and, consequently, by relatively stable financial situations. Furthermore, survey results indicate that through lifestyles promoting health and through entrepreneurial activity, these migrants improved not only their own quality of life but also that of the communities they joined. In this context, there is a high likelihood that counterurbanists will seek to remain in rural areas where they can meet their needs and pursue their goals. This connection between individuals and their place of residence—conceptualised in the literature as bondedness and rootedness [78]—is particularly important in the context of ongoing demographic processes and socio-cultural transformations in rural areas. Equally important is the development of relationships between long-established residents and newcomers. Historically, villages relied heavily on kinship and neighbourly ties [79], and the influx of new residents may generate conflicts framed in terms of “us versus them” or “newcomers as better, locals as worse” [80]. Such conflicts are often rooted in mismatches between value systems and expectations regarding rural lifestyles held by members of these two groups [43]. There are examples of villages in which newcomers, aspiring to a rustic atmosphere, oppose initiatives to pave local roads [81], while others are disturbed by crowing roosters or the intensity of agricultural work during early morning harvest hours [43]. However, over time, these initially hostile relationships between long-established residents and newcomers often evolve into cooperative and friendly relations, driven by mutual acceptance of differences and a shared concern for the village in which they live.

5. Conclusions

Counterurbanisation encompasses both quantitative changes, reflected in the growing number of people migrating to rural areas outside agglomerations, and qualitative changes, expressed, among other aspects, in the socio-cultural transformation of rural areas. As the results demonstrate, the directions and scale of this process remain spatially diverse, with population migration to rural areas outside agglomerations occurring to a greater extent in western than in eastern voivodeships of Poland. The economic activities of these new rural residents, together with their involvement and commitment to improving local living conditions, contribute to an enhanced quality of life within the rural communities they have joined. In pursuing these research objectives, the authors encountered several limitations. These limitations included difficulties in recruiting participants, reluctance to disclose information, the subjective nature of responses, and the need to maintain confidentiality. Some potential respondents declined to participate in the study due to the time commitment required for interviews. The analyses presented in this article address a significant gap in research on rural counterurbanisation in Poland and make an important contribution to the discussion on rural development influenced by urban migrants, particularly in light of insights derived from qualitative data analysis. An additional contribution of this study is its consideration of counterurbanisation as an opportunity for local policy, offering a contemporary perspective on migration and development. In summary, counterurbanisation can be an important tool for the sustainable development of rural areas through specific actions initiated by new residents: investments in both social infrastructure (e.g., establishing a nursery or kindergarten) and technical infrastructure (improving communication accessibility or expanding water and sewage networks), as well as the development of entrepreneurship. Undoubtedly, the increasing attractiveness of rural areas as places of residence leads to an affirmative answer to the question posed in the title of this article.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.W. and A.K.; methodology, M.W. and A.K.; software, M.W. and A.K.; validation, M.W., A.K. and M.G.-G.; formal analysis M.W., A.K. and M.G.-G.; investigation, M.W. and A.K.; resources, M.W. and A.K.; data curation, M.W. and A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.W., A.K. and M.G.-G.; writing—review and editing, M.W., A.K. and M.G.-G.; visualisation, M.W.; supervision, M.W. and A.K.; project administration, M.W. and A.K.; funding acquisition, M.W. and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The article is based on data collected during research as part of a project funded by the National Science Centre: 2021/41/B/HS4/02055 RURAL-URBAN KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER—MODELS OF INTERDEPENDENCIES.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the fully anonymized nature of all collected data, which aligns with the exemptions outlined in both Polish national law and the GDPR. The research utilized surveys and interviews that were designed and processed in strict compliance with the Personal Data Protection Act of 10 May 2018 and Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (GDPR). All directly identifying personal data, such as full names and addresses, were removed during data processing. The resulting dataset was irreversibly anonymized in accordance with Article 4 of the GDPR, ensuring the data could no longer be attributed to a specific individual without the use of separately and securely held additional information. Consequently, the processed data falls outside the GDPR’s definition of personal data. The study adhered to the principle of data minimization (Article 5, GDPR) and was conducted voluntarily with adult participants. The procedure included a clear informational statement advising participants of anonymity and their right to refrain from answering questions. Given that the research involved no processing of personal data, posed no risk to participant privacy, and collected no sensitive information, it did not meet the threshold requiring formal ethics committee approval under applicable regulations.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cummins, R.A. Objective and Subjective Quality of Life: An Interactive Model. Soc. Indic. Res. 2000, 52, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churski, P.; Perdał, R. Geographical differences in the quality of life in Poland: Challenges of regional policy. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 164, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwiaździńska-Goraj, M.; Jezierska-Thöle, A.; Dudzińska, M. Assessment of the Living Conditions in Polish and German Transborder Regions in the Context of Strengthening Territorial Cohesion in the European Union: Competitiveness or Complementation? Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 163, 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reig-Martínez, E. Social and economic wellbeing in Europe and the Mediterranean Basin: Building an enlarged human development indicator. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 111, 527–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sompolska-Rzechuła, A. Pomiar i ocena jakości życia. Wiadomości Stat. Pol. Stat. 2013, 58, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltramo, R.; Peira, G.; Pasino, G.; Bonadonna, A. Quality of life in rural areas: A set of indicators for improving wellbeing. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amérigo, M.; Juan Ignacio Aragonés, J.I. A theoretical and methodological approach to the study of residential satisfaction. J. Environ. Psychol. 1997, 17, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, M. Quality of place. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 5212–5315. [Google Scholar]

- Murgaš, F.; Macků, K.; Petrovič, F. Quality of life and its disparities in districts of Slovakia. GeoJournal 2025, 90, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borjas, G.J. Immigration Economics; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Todaro, M.P.; Smith, S.C. Economic Development; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.S. A Theory of Migration. Demography 1966, 3, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, Z. Globalization: The Human Consequences; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zelinsky, W. The Hypothesis of the Mobility Transition. Geogr. Rev. 1971, 61, 219–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, P.; McCarthy, L. Urbanization: An Introduction to Urban Geography; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Janicki, W. Przegląd Teorii Migracji Ludności; UMCS: Lublin, Poland, 2007; Volume 62, pp. 285–304. [Google Scholar]

- Dolińska, A.; Jończy, R.; Śleszyński, P.; Rokitowska-Malcher, J.; Rokita-Poskart, D.; Ptak, M. Migracje z Miast na Wieś. Determinanty oraz Wybrane Konsekwencje w Wymiarze Ekonomicznym i Przestrzenno-Środowiskowym (na Przykładzie Strefy Podmiejskiej Wrocławia); Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Górny, A.; Kaczmarczyk, P. Uwarunkowania i Mechanizmy Migracji Zarobkowych w Świetle Wybranych Koncepcji Teoretycznych (Conditions and Mechanisms of Labor Migration in Selected Theoretical Concepts); Prace Migracyjne No 49; ISS Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego: Warszawa, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ravenstein, E.G. The Laws of Migration. J. Stat. Soc. Lond. 1885, 46, 167–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfacree, K. Rural Populations. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Kitchin, R., Thrift, N., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijker, R.; Haartsen, T.; Strijker, D. Migration to less-popular rural areas in the Netherlands: Exploring the motivations. J. Rural Stud. 2012, 28, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.; Schafft, K. Leaving Athens: Narratives of counterurbanisation in time of crisis. J. Rural Stud. 2002, 32, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyers, W.; Nelson, P.B. Contemporary development forces in the nonmetropolitan West: New insights from rapidly growing communities. J. Rural Stud. 2000, 16, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vias, A.C. Micropolitan areas and urbanization processes in the US. Cities 2012, 29, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjarnason, T.; Stockdale, A.; Shuttleworth, I.; Eimermann, M.; Shucksmith, M. At the intersection of urbanisation and counterurbanisation in rural space: Microurbanisation in Northern Iceland. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 87, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, B.J.L. Urbanization and Countrurbanization; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Haandrikman, K.; Hedberg, C.; Chihaya, G.K. New immigration destinations in Sweden: Migrant residential trajectories intersecting rural areas. Sociol. Rural. 2023, 64, 280–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzeszczak, J. Kontrurbanizacja—Idea i rzeczywistość. Przegląd Geogr. 2000, 72, 373–393. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, C.J.A. Making sense of counterurbanization. J. Rural Stud. 2004, 20, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, A.G. Counterurbanisation; Arnold: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, L. The Amenity Migrants; CAB Institute: Oxfordshire, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, M.; O’reilly, K. Migration and the search for a better way of life: A critical exploration of lifestyle migration. Sociol. Rev. 2009, 57, 608–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beale, C.L. Rural development, population and settlement prospects. J. Soil Water Conserv. 1974, 29, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, P.; Halfacree, K.; Robinson, V. Exploring Contemporary Migration; Rout-Ledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barrington-Leigh, C.; Millard-Bal, A. A century of sprawl in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 8244–8249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szmytkowska, M.; Masik, G. Społeczne aspekty suburbanizacji w obszarze metro politarnym Trójmiasta. In Problem Suburbanizacji; Lorens, P., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Urbanista: Warszawa, Poland, 2005; pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Laskowska-Otwinowska, I. Globalne Przepływy Kulturowe a Obecność Nowoosadników na wsi Polskiej; Muzeum Archeologiczne i Etnograficzne: Łódź, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wrona, A. Przeprowadzki z miast do wsi: Spotkanie dwóch kultur i co z niego wynika dla lokalnych społeczności. Górnośląskie Stud. Socjol. Ser. Nowa 2020, 6, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilnicki, D. Przekształcenia wybranych elementów struktur demograficznych miejscowości charakterystycznych dla strefy podmiejskiej Wrocławia. Bull. Geogr. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2002, 1, 202–216. [Google Scholar]

- Rejter, M. Suburbanizacja po łódzku na przykładzie Starej Gadki zlokalizowa nej w strefie podmiejskiej Łodzi. Stud. Miej. 2018, 32, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, D.; Biegańska, J. Fenomen urbanizacji i procesy z nim związane. In Studia Miejskie; Słodczyk, J., Śmigielska, M., Eds.; Uniwersytet Opolski: Opole, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Grzeszczak, J. Przesunięcie Miasto-Wieś w Przemyśle Krajów Unii Europejskiej; Zeszyty IGiPZ PAN, 55; IGiPZ PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kajdanek, K. Pomiędzy Miastem, a Wsią. Suburbanizacja na Przykładzie Osiedli Podmiejskich Wrocławia; Zakład Wydawniczy NOMOS: Kraków, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kajdanek, K. Suburbanizacja po Polsku; Zakład Wydawniczy NOMOS: Kraków, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dej, M.; Zajda, K. Kontrurbanizacja i jakość życia na wsi. Acta Univ. Lodz. Folia Sociol. 2016, 57, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/statystyka-regionalna/jednostki-terytorialne/delimitacja-obszarow-wiejskich-dow-/ (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/BDL (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/migracje-wewnetrzne-ludnosci/migracje-wewnetrzne-ludnosci-na-pobyt-staly-wedlug-wojewodztw-w-latach-1974-2023,3,1.html (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Available online: https://www.geoportal.gov.pl/en/data/national-register-of-boundaries/ (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Halfacree, K. The importance of ‘the rural’ in the constitution of counterurbanization: Evidence from England in the 1980s. Sociol. Rural. 1994, 34, 164–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newby, H. Green and Pleasant Land?: Social Change in Rural England; Hutchinson of London: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Champion, T. Urbanization, suburbanization, counterurbanization and reurbanization. Handb. Urban Stud. 2001, 160, 143–161. [Google Scholar]

- Batty, M. The New Science of Cities; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Grzeszczak, J. Tendencje kontrurbanizacyjne w krajach Europy Zachodniej, Prace Geograficzne; Instytut Geografii i Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 1996; Volume 167. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, H.S. Explanations for Long-Distance Counter-Urban Migration into Fringe Areas in Denmark. Popul. Space Place 2009, 17, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milbourne, P.; Kitchen, L. Rural mobilities: Connecting movement and fixity in rural places. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 34, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sołtysiak, M.; Zając, D. Differences in the local residential real estate market in Poland depending on population density. Real Estate Manag. Valuat. 2024, 32, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikowski, R. Syntetyczne Metody Badań Produktywności i Towarowości Rolnictwa: Zastosowania w Badaniach Geograficznych w Polsce; IGiPZ PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stanny, M. Przestrzenne Zróżnicowanie Rozwoju Obszarów Wiejskich w Polsce; IRWiR PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Polak, E. Jakość życia w polskich województwach—Analiza porównawcza wybranych regionów. Nierówności Społeczne A Wzrost Gospod. 2020, 4, 66–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, R.; Lipska, K. Zróżnicowanie regionalne jakości życia w Polsce w kontekście wybranych obszarów—Wielowymiarowa analiza porównawcza. Metod. Ilościowe Badaniach Ekon. 2024, 25, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bański, J.; Dobrowolski, J.; Flaga, M.; Janicki, W.; Wesołowska, W. Wpływ granicy państwowej na kierunki rozwoju społeczno-gospodarczego wschodniej części województwa lubelskiego. In Studia Obszarów Wiejskich; IGiPZ PAN-PTG: Warszawa, Poland, 2010; Volume 21. [Google Scholar]

- Wesołowska, M. (Ed.) Wiejskie obszary peryferyjne-uwarunkowania i czynniki aktywizacji = Peripheral rural areas-conditions and factors stimulating to activity. In Studia Obszarów Wiejskich; IGiPZ PAN-PTG: Warszawa, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Flaga, M.; Wesołowska, M. Demographic and social degradation in the Lubelskie Voivodeship as a peripheral area of East Poland. Bull. Geogr. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2018, 41, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanny, M.; Rosner, A.; Komorowski, Ł. Monitoring Obszarów Wiejskich. Etap IV. Dekada Przemian Społeczno-Gospodarczych (Wersja Pełna); IRWIR PAN, FEFRWP: Warszawa, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gwiaździńska-Goraj, M.; Goraj, S. The contribution of the natural environment to sustainable development on the example of rural areas in the Region of Warmia and Mazury. J. Rural Dev. 2013, 6, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, E. Warmia i Mazury; Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie: Wrocław, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Adamski, J. COVID-19 i jego wpływ na migracje—Splot relacji polityki-pracy-przemocy. Władza Sądzenia 2020, 18, 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullano, G.; Valdano, E.; Scarpa, N.; Rubrichi, S.; Colizza, V. Population mobility reductions during COVID-19 epidemic in France under lockdown. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wesołowska, M.; Gwiaździńska-Goraj, M. Construction attractiveness of Poland’s rural areas during the COVID-19 pandemic. GIS Odyssey J. 2025, 5, 161–174. [Google Scholar]

- González-Leonardo, M.; Rowe, F.; Fresolone-Caparrós, A. Rural revival? The rise in internal migration to rural areas during the COVID-19 pandemic. Who moved and Where? J. Rural Stud. 2022, 96, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfacree, K. To revitalise counterurbanisation research? Recognising an international and fuller picture. Popul. Space Place 2008, 14, 479–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfacree, K. Trial by space for a “radical rural”: Introducing alternative localities, representations and lives. J. Rural Stud. 2007, 23, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfacree, K. Heterolocal identities? Counter-urbanisation, second homes, and rural consumption in the era of mobilities. Popul. Space Place 2012, 18, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://eu-nieruchomosci.pl/wzrost-cen-nieruchomosci-gus (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- Available online: https://investropa.com/blogs/news/poland-property-how-much-really-duplicate (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- Maslow, A.H. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, R. Sense of place in developmental context. J. Environ. Psychol. 1998, 18, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieruszewska-Adamczyk, M. Wieś polska w perspektywie stulecia. Refleksje rocznicowe 1918–2018. Zesz. Wiej. 2018, 24, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zborowski, A.; Pawlak, H.; Gałka, J. Relacje społeczne między mieszkańcami wsi i ludnością napływową z miasta w strefie podmiejskiej Krakowa—Przestrzeń konfliktu czy współpracy? Konwersatorium Wiedzy Mieście 2019, 4, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadura, P.; Murawska, K.; Włodarczyk, Z. Wieś w Polsce 2017: Diagnoza i Prognoza; Fundacja Wspomagania Wsi: Warszawa, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.