Harnessing Endophytic Fungi for Sustainable Agriculture: Interactions with Soil Microbiome and Soil Health in Arable Ecosystems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Fungal Endophytes: Definition, Categorization, Distribution, and Ecological Niches

3.1. Definition

3.2. Classification

3.3. Global Distribution and Ecological Niches

4. Diversity and Ecological Roles of EFs in Arable Land

4.1. Diversity Patterns and Drivers in Arable Systems

4.2. Ecological Roles in Arable Land: From Plant Traits to Soil Functions

4.3. How Arable Management Reshapes EF Diversity and Function

4.4. Methodological Advances and Functional Validation

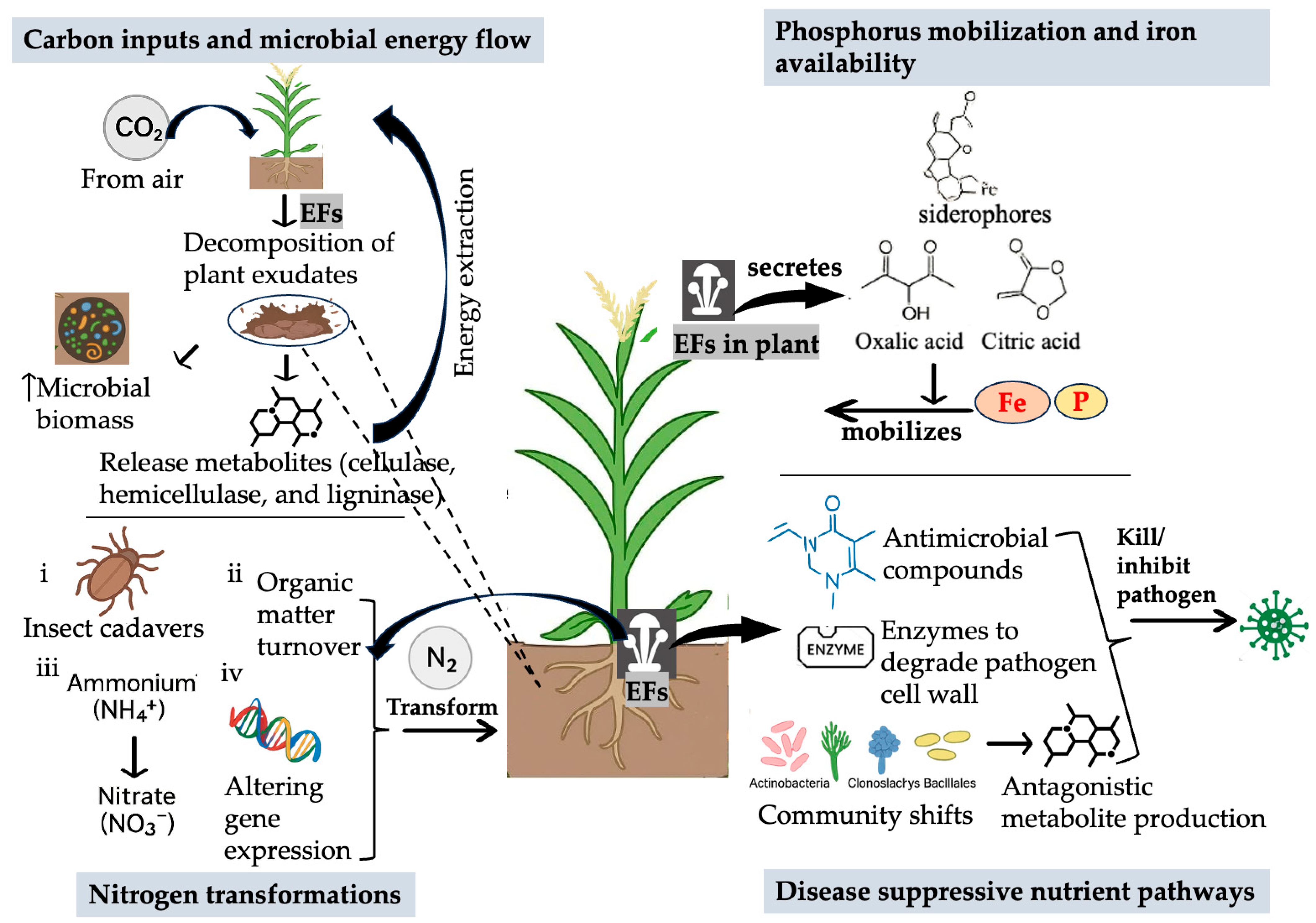

5. Mechanisms of Plant Growth Promotion by EFs

5.1. Hormone Modulation and Root System Reprogramming

5.2. Ethylene Stress Reduction via ACC Deaminase and Stress Signaling Dampening

5.3. Nutrient Mobilization: P Solubilization, Micronutrient Acquisition, and N-Use Efficiency

5.4. Indirect Growth Promotion via Microbiome Recruitment and Rhizosphere Engineering

5.5. Bioactive Metabolites, VOCs and Immune Priming That Support Growth

5.6. Evidence from Field Trials and Translational Constraints

6. EFs in Abiotic Stress Tolerance

7. EFs in Biocontrol of Plant Pathogens

7.1. Direct Antagonism of Pathogens (Contact-Dependent)

7.2. Volatile-Mediated Inhibition and “Distance Effects” (Contact-Independent)

7.3. Competition and Niche Exclusion in the Rhizosphere/Root Interface

7.4. Host-Mediated Resistance: Immune Priming and Systemic Protection ISR-like Responses and Priming

8. Interactions with the Soil Microbiome and Nutrient Cycling

8.1. Mechanisms by Which Endophytes Remodel the Soil Microbiome

8.1.1. EFs Influence on Soil Aggregation

8.1.2. Immune Priming, Exudation Shifts, and Community Assembly

8.1.3. Competitive Exclusion and Niche Preemption

8.1.4. VOCs and Signaling at a Distance

8.2. Consequences for Nutrient Cycling in Arable Soils

8.3. Complementary Soil Management Approaches That Amplify EF-Mediated Benefits

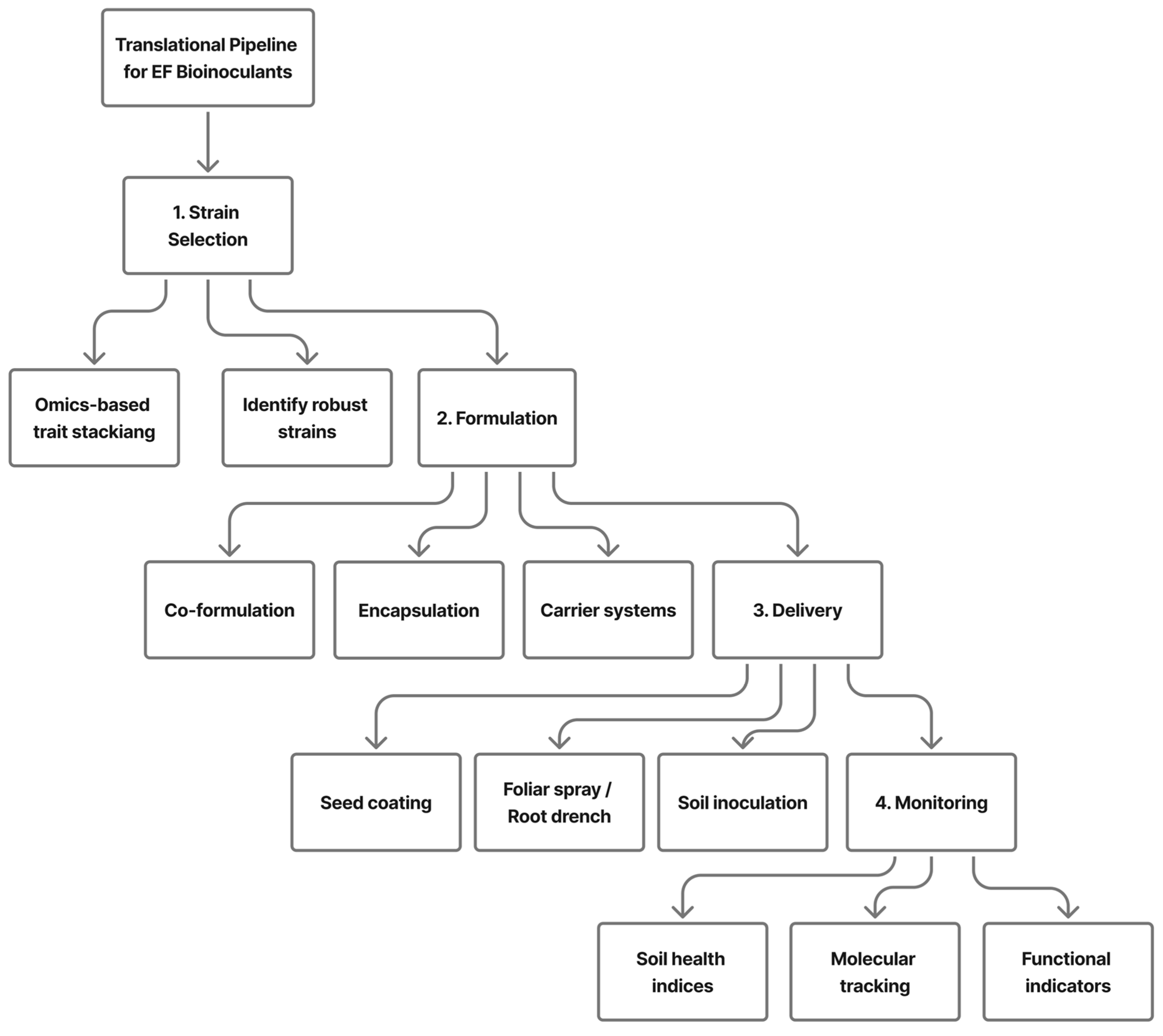

9. Translational Pipeline: Strain → Formulation → Delivery → Monitoring

9.1. Strain Selection and Trait Stacking

9.2. Formulation and Production Technologies

9.3. Delivery Methods in Arable Systems

9.4. Monitoring and Feedback Mechanisms

10. Integration with Sustainable Crop Production Practices

10.1. Methods for Integrating EFs

10.1.1. Traditional Methods

10.1.2. Advanced and Innovative Methods

11. Challenges and Limitations for EFs Application

12. Future Perspectives and Research Priorities of EFs

13. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EFs | Endophytic fungi |

| AMF | Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi |

| GRSP | Glomalin-related soil proteins |

| ISR | Induced systemic resistance |

| IPM | Integrated pest management |

| VOCs | Volatile organic compounds |

| HTS | High-throughput sequencing |

| ITS | Internal transcribed spacer (fungal barcode region) |

| qPCR | Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| SIP | Stable isotope probing |

| IAA | Indole-3-acetic acid |

| GAs | Gibberellins |

| ABA | Abscisic acid |

| JA | Jasmonic acid |

| SA | Salicylic acid |

| ET | Ethylene |

| ACC | 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate |

| EPS | Extracellular polymeric substances |

| MBC | Microbial biomass carbon |

| WSA | Water-stable aggregates |

| SOC | Soil organic carbon |

| C, N, P | Carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus |

| VAM | Vesicular–arbuscular mycorrhizae |

| PSB | Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria |

References

- Lehmann, J.; Bossio, D.A.; Kögel-Knabner, I.; Rillig, M.C. The concept and future prospects of soil health. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO; The State of Food and Agriculture. Leveraging Food Systems for Inclusive Rural Transformation; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017; p. 181. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/i7658en (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Petrini, O. Fungal endophytes of tree leaves. In Microbial Ecology of Leaves; Andrews, J.H., Hirano, S.S., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, B.; Boyle, C. The endophytic continuum. Mycol. Res. 2005, 109, 661–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.J.; White, J.F., Jr.; Arnold, A.E.; Redman, R.S. Fungal endophytes: Diversity and functional roles. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 314–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.F., Jr.; Kingsley, K.L.; Butterworth, S.; Brindisi, L.; Gatei, J.W.; Elmore, M.T.; Kowalski, K.P. Seed-Vectored Microbes: Their Roles in Improving Seedling Fitness and Competitor Plant Suppression. In Seed Endophytes: Biology and Biotechnology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.; Leach, J.E.; Tringe, S.G.; Sa, T.; Singh, B.K. Plant–microbiome interactions: From community assembly to plant health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compant, S.; Samad, A.; Faist, H.; Sessitsch, A. A Review on the Plant Microbiome: Ecology, Functions, and Emerging Trends in Microbial Application. J. Adv. Res. 2019, 19, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Heijden, M.G.A.; Martin, F.M.; Selosse, M.A.; Sanders, I.R. Mycorrhizal ecology and evolution: The past, the present, and the future. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 1406–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillig, M.C.; Mummey, D.L. Mycorrhizas and soil structure. New Phytol. 2006, 171, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, J.; Bossuyt, H.; Degryze, S.; Denef, K. A History of Research on the Link Between (Micro)Aggregates, Soil Biota, and Soil Organic Matter Dynamics. Soil Tillage Res. 2004, 79, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guhra, T.; Stolze, K.; Totsche, K.U. Pathways of Biogenically Excreted Organic Matter into Soil Aggregates. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 164, 108483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.J.; Henson, J.; Van Volkenburgh, E.; Hoy, M.; Wright, L.; Beckwith, F.; Kim, Y.O.; Redman, R.S. Stress tolerance in plants via habitat-adapted symbiosis. ISME J. 2008, 2, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.F.; Kingsley, K.L.; Zhang, Q.; Verma, R.; Obi, N.; Dvinskikh, S.; Elmore, M.T.; Verma, S.K.; Gond, S.K.; Kowalski, K.P. Review: Endophytic microbes and their potential applications in crop management. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2558–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; The State of Food and Agriculture. Sustainable Use and Conservation of Microbial and Invertebrate Biological Control Agents and Microbial Biostimulants; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023; p. 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.; Batista, B.D.; Bazany, K.E.; Singh, B.K. Plant–microbiome interactions under a changing world: Responses, consequences and perspectives. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 1951–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bary, A. Morphologie und Physiologie der Pilze, Flechten Und Myxomyceten; Smithsonian Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 1866; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Gakuubi, M.M.; Munusamy, M.; Liang, Z.X.; Ng, S.B. Fungal endophytes: A promising frontier for discovery of novel bioactive compounds. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, N.C.; Rigobelo, E.C. Endophytic fungi: A tool for plant growth promotion and sustainable agriculture. Mycology 2022, 13, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, G. Fungal endophytes in stems and leaves: From latent pathogen to mutualistic symbiont. Ecology 1988, 69, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D. Endophyte: The evolution of a term, and clarification of its use and definition. Oikos 1995, 73, 274–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardoim, P.R.; Van Overbeek, L.S.; Berg, G.; Pirttilä, A.M.; Compant, S.; Campisano, A.; Döring, M.; Sessitsch, A. The hidden world within plants: Ecological and evolutionary considerations for defining functioning of microbial endophytes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2015, 79, 293–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Shi, B. Endophytic fungi from the four staple crops and their secondary metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harman, G.E. Integrated benefits to agriculture with Trichoderma and other endophytic or root-associated microbes. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, K. Clavicipitaceous endophytes of grasses: Their potential as biocontrol agents. Mycol. Res. 1989, 92, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caradus, J.R. Epichloë fungal endophytes–a vital component for perennial ryegrass survival in New Zealand. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 2024, 67, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, G.E.; Howell, C.R.; Viterbo, A.; Chet, I.; Lorito, M. Trichoderma species—Opportunistic, avirulent plant symbionts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, S.; Johnson, L.; Teasdale, S.; Caradus, J. Deciphering endophyte behaviour: The link between endophyte biology and efficacious biological control agents. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92, fiw114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, A.E.; Lutzoni, F. Diversity and host range of foliar fungal endophytes: Are tropical leaves biodiversity hotspots? Ecology 2007, 88, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyde, K.D.; Jeewon, R.; Chen, Y.J.; Bhunjun, C.S.; Calabon, M.S.; Jiang, H.B.; Lin, C.G.; Norphanphoun, C.; Sysouphanthong, P.; Pem, D.; et al. The numbers of fungi: Is the descriptive curve flattening? Fungal Divers. 2020, 103, 219–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumpponen, A. Dark septate endophytes–are they mycorrhizal? Mycorrhiza 2001, 11, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikes, B.A.; Hawkes, C.V.; Fukami, T. Plant and root endophyte assembly history: Interactive effects on native and exotic plants. Ecology 2016, 97, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagic, M.; Faville, M.J.; Zhang, W.; Forester, N.T.; Rolston, M.P.; Johnson, R.D.; Ganesh, S.; Koolaard, J.P.; Easton, H.S.; Hudson, D.; et al. Seed transmission of Epichloë endophytes in Lolium perenne is heavily influenced by host genetics. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.K.; Kharwar, R.N.; White, J.F. The role of seed-vectored endophytes in seedling development and establishment. Symbiosis 2019, 78, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryanarayanan, T.S. Endophyte research: Going beyond isolation and metabolite documentation. Fungal Ecol. 2013, 6, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, K.; van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Wittwer, R.A.; Banerjee, S.; Walser, J.C.; Schlaeppi, K. Cropping practices manipulate abundance patterns of root and soil microbiome members paving the way to smart farming. Microbiome 2018, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrù, L.; Canfora, L.; Trinchera, A.; Migliore, M.; Pennelli, B.; Marcucci, A.; Farina, R.; Pinzari, F. How tillage and crop rotation change the distribution pattern of fungi. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 634325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, S.; Sekara, A.; Pokluda, R. Serendipita indica—A review from an agricultural point of view. Plants 2022, 11, 3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Gill, R.; Trivedi, D.K.; Anjum, N.A.; Sharma, K.K.; Ansari, M.W.; Tuteja, N. Piriformospora indica: Potential and significance in plant stress tolerance. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO; The State of Food and Agriculture. The Nineteenth Regular Session of the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023; Available online: https://www.fao.org/cgrfa/meetings/detail/Nineteenth-Regular-Session/en (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Fang, K.; Miao, Y.F.; Chen, L.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Z.P.; Dong, X.F.; Zhang, H.B. Tissue-Specific and Geographical Variation in Endophytic Fungi of Ageratina adenophora and Fungal Associations with the Environment. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseyni Moghaddam, M.S.H.; Safaie, N.; Tedersoo, L.; Hagh-Doust, N. Diversity, community composition, and bioactivity of cultivable fungal endophytes in saline and dry soils in deserts. Fungal Ecol. 2021, 49, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Sahib, M.R.; Amna, A.; Opiyo, S.O.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, Y.G. Culturable endophytic fungal communities associated with plants in organic and conventional farming systems and their effects on plant growth. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Akutse, K.S.; Saqib, H.S.A.; Wu, X.; Yang, F.; Xia, X.; Wang, L.; Goettel, M.S.; You, M.; Gurr, G.M. Fungal endophyte communities of crucifer crops are seasonally dynamic and structured by plant identity, plant tissue and environmental factors. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommermann, L.; Geistlinger, J.; Wibberg, D.; Deubel, A.; Zwanzig, J.; Babin, D.; Schlüter, A.; Schellenberg, I. Fungal Community Profiles in Agricultural Soils of a Long-Term Field Trial under Different Tillage, Fertilization and Crop Rotation Conditions Analyzed by High-Throughput ITS-Amplicon Sequencing. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.; Sharma, R.; Putatunda, C.; Walia, A. Endophytic Fungi: Role in Phosphate Solubilization. In Advances in Endophytic Fungal Research: Present Status and Future Challenges; Singh, B.P., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 183–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellouze, W.; Esmaeili Taheri, A.; Bainard, L.D.; Yang, C.; Bazghaleh, N.; Navarro-Borrell, A.; Hanson, K.; Hamel, C. Soil Fungal Resources in Annual Cropping Systems and Their Potential for Management. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 531824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Shi, L.; Wang, K.; Liu, B.; Liao, J.; An, Z.; Chang, S.X. Crop Rotation Differentially Increases Soil Bacterial and Fungal Diversities in Global Croplands: A Meta-Analysis. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 11686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, I.; Raina, A.; Choudhary, M.; Apra, S.; Kaul, S.; Dhar, M.K. Fungal Endophyte Bioinoculants as a Green Alternative towards Sustainable Agriculture. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Moslamy, S.H.; Elkady, M.F.; Rezk, A.H.; Abdel-Fattah, Y.R. Applying Taguchi Design and Large-Scale Strategy for Mycosynthesis of Nano-Silver from Endophytic Trichoderma harzianum SYA.F4 and Its Application against Phytopathogens. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade-Hoyos, P.; Silva-Rojas, H.V.; Romero-Arenas, O. Endophytic Trichoderma Species Isolated from Persea americana and Cinnamomum verum Roots Reduce Symptoms Caused by Phytophthora cinnamomi in Avocado. Plants 2020, 9, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asghar, W.; Craven, K.D.; Kataoka, R.; Mahmood, A.; Asghar, N.; Raza, T.; Iftikhar, F. The Application of Trichoderma spp., an Old but New Useful Fungus, in Sustainable Soil Health Intensification: A Comprehensive Strategy for Addressing Challenges. Plant Stress 2024, 12, 100455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, A.; Verma, S.; Sudha; Sahay, N.; Butehorn, B.; Franken, P. Piriformospora indica, a cultivable plant-growth-promoting root endophyte. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 2741–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Feng, Y.; Qi, F.; Hao, R. Research progress of Piriformospora indica in improving plant growth and stress resistance to plant. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajilogba, C.F.; Babalola, O.O. Integrated management strategies for tomato Fusarium wilt. Biocontrol Sci. 2013, 18, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, M.E.; De Lamo, F.J.; Vlieger, B.V.; Rep, M.; Takken, F.L.W. Endophyte-mediated resistance in tomato to Fusarium oxysporum is independent of ET, JA, and SA. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dargiri, S.A.; Naeimi, S.; Nekouei, M.K. Enhancing Wheat Resilience to Salinity: The Role of Endophytic Penicillium chrysogenum as a Biological Agent for Improved Crop Performance. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdappa, S.; Jagannath, S.; Konappa, N.; Udayashankar, A.C.; Jogaiah, S. Detection and Characterization of Antibacterial Siderophores Secreted by Endophytic Fungi from Cymbidium aloifolium. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, P.; Singh, M.; Sharma, A.; Chadha, P.; Kaur, A. Plant growth promoting endophytic fungus Aspergillus niger VN2 enhances growth, regulates oxidative stress and protects DNA damage in Vigna radiata under salt stress. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeano, R.M.S.; Franco, D.G.; Chaves, P.O.; Giannesi, G.C.; Masui, D.C.; Ruller, R.; Zanoelo, F.F. Plant Growth Promoting Potential of Endophytic Aspergillus niger 9-p Isolated from Native Forage Grass in the Pantanal of the Nhecolândia Region, Brazil. Rhizosphere 2021, 18, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshahawy, I.E.; Khattab, A.E.N.A. Endophyte Chaetomium globosum Improves the Growth of Maize Plants and Induces Their Resistance to Late Wilt Disease. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2022, 129, 1125–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, N.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, H.; Tang, C. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Defense Mechanism of Cotton against Verticillium dahliae in the Presence of the Biocontrol Fungus Chaetomium globosum CEF-082. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demissie, Z.A.; Foote, S.J.; Tan, Y.; Loewen, M.C. Profiling of the Transcriptomic Responses of Clonostachys rosea upon Treatment with Fusarium graminearum Secretome. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkölmez, Ş.; Özer, G.; Derviş, S. Clonostachys rosea Strain ST1140: An Endophytic Plant-Growth-Promoting Fungus, and Its Potential Use in Seedbeds with Wheat-Grain Substrate. Curr. Microbiol. 2022, 80, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yansombat, J.; Samosornsuk, S.; Khattiyawech, C.; Hematulin, P.; Pharamat, T.; Kabir, S.L.; Samosornsuk, W. Colletotrichum truncatum, an endophytic fungus derived from Musa acuminata (AAA group): Antifungal activity against Aspergillus isolated from COVID-19 patients and indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production. Asian-Australas. J. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2023, 8, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranathunge, N.P.; Sandani, H.B.P. Deceptive Behaviour of Colletotrichum truncatum: Strategic Survival as an Asymptomatic Endophyte on Non-Host Species. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2016, 56, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shahir, A.A.; El-Tayeh, N.A.; Ali, O.M.; Abdel Latef, A.A.H.; Loutfy, N. The effect of endophytic Talaromyces pinophilus on growth, absorption and accumulation of heavy metals of Triticum aestivum grown on sandy soil amended by sewage sludge. Plants 2021, 10, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, P.; Singh, S.; Chaudhary, A.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, G. Overview of biofertilizers in crop production and stress management for sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 930340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, F.M.; Machado, T.I.; Torres, C.A.R.; Souza, H.R.D.; Celestino, M.F.; Silva, M.A.; Monnerat, R.G. Purpureocillium lilacinum SBF054: Endophytic in Phaseolus vulgaris, Glycine max, and Helianthus annuus; Antagonistic to Rhizoctonia solani; and Virulent to Euschistus heros. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo Lopez, D.; Zhu-Salzman, K.; Ek-Ramos, M.J.; Sword, G.A. The Entomopathogenic Fungal Endophytes Purpureocillium lilacinum (Formerly Paecilomyces lilacinus) and Beauveria bassiana Negatively Affect Cotton Aphid Reproduction under Both Greenhouse and Field Conditions. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, F.E. The use of fungal entomopathogens as endophytes in biological control: A review. Mycologia 2018, 110, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, Y.; Taibo, A.D.; Jiménez, J.A.; Portal, O. Endophytic establishment of Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae in maize plants and its effect against Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) larvae. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2020, 30, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.L.; Scorsetti, A.C.; Vianna, M.F.; Cabello, M.; Ferreri, N.; Pelizza, S. Endophytic effects of Beauveria bassiana on corn (Zea mays) and its herbivore, Rachiplusia nu (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Insects 2019, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.P.; Oliveira, J.A.S.; Polonio, J.C.; Pamphile, J.A.; Azevedo, J.L. Recombinants of Alternaria alternata endophytes enhance inorganic phosphate solubilization and plant growth hormone production. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 51, 102784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.H.; Abd El-Megeed, F.H.; Hassanein, N.M.; Youseif, S.H.; Farag, P.F.; Saleh, S.A.; Abdel-Wahab, B.A.; Alsuhaibani, A.M.; Helmy, Y.A.; Abdel-Azeem, A.M. Native rhizospheric and endophytic fungi as sustainable sources of plant growth promoting traits to improve wheat growth under low nitrogen input. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; ITPS; GSBI; SCBD; EC. State of Knowledge of Soil Biodiversity—Status, Challenges and Potentialities; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; p. 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Khan, A.L.; Kamran, M.; Hamayun, M.; Kang, S.M.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, I.J. Endophytic fungi produce gibberellins and indoleacetic acid and promotes host-plant growth during stress. Molecules 2012, 17, 10754–10773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poveda, J.; Eugui, D.; Abril-Urías, P.; Velasco, P. Endophytic fungi as direct plant growth promoters for sustainable agricultural production. Symbiosis 2021, 85, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitnis, V.R.; Suryanarayanan, T.S.; Nataraja, K.N.; Prasad, S.R.; Oelmüller, R.; Shaanker, R.U. Fungal endophyte-mediated crop improvement: The way ahead. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 561007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, B.R. Bacteria with ACC deaminase can promote plant growth and help to feed the world. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 169, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.E.; Barea, J.M.; McNeill, A.M.; Prigent-Combaret, C. Acquisition of phosphorus and nitrogen in the rhizosphere and plant growth promotion by microorganisms. Plant Soil 2009, 321, 305–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujvári, G.; Turrini, A.; Avio, L.; Agnolucci, M. Possible role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and associated bacteria in the recruitment of endophytic bacterial communities by plant roots. Mycorrhiza 2021, 31, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Gao, Y.; Liu, H.; Gao, Y.B.; van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Ren, A.Z. Plant endophytes and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi alter plant competition. Funct. Ecol. 2018, 32, 1168–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.X.; Chen, S.J.; Hong, X.Y.; Wang, L.Z.; Wu, H.M.; Tang, Y.Y.; Gao, Y.Y.; Hao, G.F. Plant exudates-driven microbiome recruitment and assembly facilitates plant health management. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2025, 49, fuaf008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morath, S.U.; Hung, R.; Bennett, J.W. Fungal volatile organic compounds: A review with emphasis on their biotechnological potential. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2012, 26, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechulla, B.; Lemfack, M.C.; Kai, M. Effects of discrete bioactive microbial volatiles on plants and fungi. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 2042–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadiji, A.E.; Babalola, O.O. Elucidating mechanisms of endophytes used in plant protection and other bioactivities with multifunctional prospects. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, B.; Javed, J.; Rauf, M.; Khan, S.A.; Arif, M.; Hamayun, M.; Gul, H.; Khilji, S.A.; Sajid, Z.A.; Kim, W.C.; et al. ACC deaminase-producing endophytic fungal consortia promotes drought stress tolerance in M. oleifera by mitigating ethylene and H2O2. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 967672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suebrasri, T.; Harada, H.; Jogloy, S.; Ekprasert, J.; Boonlue, S. Auxin-producing fungl endophytes promote growth of sunchoke. Rhizosphere 2020, 16, 100271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Shameem, N.; Jatav, H.S.; Sathyanarayana, E.; Parray, J.A.; Poczai, P.; Sayyed, R.Z. Fungal endophytes to combat biotic and abiotic stresses for climate-smart and sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 953836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safi, H.; Hussain, A.; Shah, M.; Hamayun, M.; Qadir, M.; Iqbal, A. Heavy Metal-Tolerant Endophytic Fungus Aspergillus welwitschiae Improves Growth, Ceases Metal Uptake, and Strengthens the Antioxidant System in Glycine max L. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 15501–15515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Li, X.; Perumal, A.B.; Zhu, J.; Lu, X.; Dai, M.; Liu, X.; Lin, F. The endophytic fungus Piriformospora indica-assisted alleviation of cadmium in tobacco. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, A.; Tafteh, M.; Roudbari, N.; Pishkar, L.; Zhang, W.; Wu, C. Piriformospora indica Augments Arsenic Tolerance in Rice (Oryza sativa) by Immobilizing Arsenic in Roots and Improving Iron Translocation to Shoots. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 209, 111793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeshwari Nanda, R.N.; Veena Agrawal, V.A. Piriformospora indica, an Excellent System for Heavy Metal Sequestration and Amelioration of Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage in Cassia angustifolia Vahl under Copper Stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 158, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, P. Endophytic fungi as regulators of phytohormones production: Cytomolecular effects on plant growth, stress protection and importance in sustainable agriculture. Plant Stress 2025, 17, 100978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Vargas, A.T.; López-Ramírez, V.; Álvarez-Mejía, C.; Vázquez-Martínez, J. Endophytic fungi for crops adaptation to abiotic stresses. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Xie, Q.; Tao, J.; Jia, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Tang, Z.; Li, Q.; Yuan, M.; Bu, T. Exploring plant growth-promoting traits of endophytic fungi isolated from Ligusticum chuanxiong Hort and their interaction in plant growth and development. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.K.; Sahu, P.K.; Kumar, K.; Pal, G.; Gond, S.K.; Kharwar, R.N.; White, J.F. Endophyte roles in nutrient acquisition, root system architecture development and oxidative stress tolerance. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 131, 2161–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, M.; Kailoo, S.; Khan, R.T.; Khan, S.S.; Rasool, S. Harnessing fungal endophytes for natural management: A biocontrol perspective. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1280258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perumalsamy Priyadharsini, P.P.; Thangavelu Muthukumar, T.M. The root endophytic fungus Curvularia geniculata from Parthenium hysterophorus roots improves plant growth through phosphate solubilization and phytohormone production. Fungal Ecol. 2017, 29, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asomadu, R.O.; Ezeorba, T.P.C.; Ezike, T.C.; Uzoechina, J.O. Exploring the Antioxidant Potential of Endophytic Fungi: A Review on Methods for Extraction and Quantification of Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC). 3 Biotech 2024, 14, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Liao, X.; Yan, Q.; Xie, Y.; Chen, J.; Liang, G.; Liu, J. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi improve the growth, water status, and nutrient uptake of Cinnamomum migao and the soil nutrient stoichiometry under drought stress and recovery. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hestrin, R.; Kan, M.; Lafler, M.; Wollard, J.; Kimbrel, J.A.; Ray, P.; Pett-Ridge, J. Plant-associated fungi support bacterial resilience following water limitation. ISME J. 2022, 16, 2752–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fracchia, F.; Guinet, F.; Engle, N.L.; Tschaplinski, T.J.; Veneault-Fourrey, C.; Deveau, A. Microbial colonisation rewires the composition and content of poplar root exudates, root and shoot metabolomes. Microbiome 2024, 12, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Asiegbu, F.O.; Wu, P.; Ma, X.; Wang, K. Advances in the beneficial endophytic fungi for the growth and health of woody plants. For. Res. 2024, 4, e028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseyni Moghaddam, M.S.; Safaie, N.; Rahimlou, S.; Hagh-Doust, N. Inducing tolerance to abiotic stress in Hordeum vulgare L. by halotolerant endophytic fungi associated with salt lake plants. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 906365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, Z.S.; Wei, X.; Umar, M.; Abideen, Z.; Zulfiqar, F.; Chen, J.; Hanif, A.; Dawar, S.; Dias, D.A.; Yasmeen, R. Scrutinizing the application of saline endophyte to enhance salt tolerance in rice and maize plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 770084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, K.; Ibrahim, B.; Ahmad Bawadikji, A.; Lim, J.W.; Tong, W.Y.; Leong, C.R.; Khaw, K.Y.; Tan, W.N. Recent developments in metabolomics studies of endophytic fungi. J. Fungi 2021, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; He, Z.; He, X.; Lin, Y.; Kong, X. Tracing microbial community across endophyte-to-saprotroph continuum of Cinnamomum camphora (L.) Presl leaves considering priority effect of endophyte on litter decomposition. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1518569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Murrell, J.C. When metagenomics meets stable-isotope probing: Progress and perspectives. Trends Microbiol. 2010, 18, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Priyanka; Sharma, S. Metabolomic Insights into Endophyte-Derived Bioactive Compounds. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 835931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantigoso, H.A.; Newberger, D.; Vivanco, J.M. The rhizosphere microbiome: Plant–microbial interactions for resource acquisition. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 133, 2864–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsharif, N.A.; El Awamie, M.W.; Matuoog, N. Will the Endophytic Fungus Phomopsis liquidambari Increase N-Mineralization in Maize Soil? PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0293281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Yin, D.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Cao, Y.; Chen, T.; Wang, D. Succession of Endophytic Fungi and Rhizosphere Soil Fungi and Their Correlation with Secondary Metabolites in Fagopyrum dibotrys. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1220431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fite, T.; Kebede, E.; Tefera, T.; Bekeko, Z. Endophytic fungi: Versatile partners for pest biocontrol, growth promotion, and climate change resilience in plants. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1322861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoresh, M.; Harman, G.E.; Mastouri, F. Induced systemic resistance and plant responses to fungal biocontrol agents. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2010, 48, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koprivica, M.; Petrović, J.; Simić, M.; Dimitrijević, J.; Ercegović, M.; Trifunović, S. Characterization and evaluation of biomass waste biochar for turfgrass growing medium enhancement in a pot experiment. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.W.; Rice, C.W.; Rillig, M.C.; Springer, A.; Hartnett, D.C. Soil aggregation and carbon sequestration are tightly correlated with the abundance of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: Results from long-term field experiments. Ecol. Lett. 2009, 12, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinale, F.; Sivasithamparam, K.; Ghisalberti, E.L.; Marra, R.; Woo, S.L.; Lorito, M. Trichoderma–plant–pathogen interactions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.B.; Li, S.D.; Ren, Q.; Xu, J.L.; Lu, X.; Sun, M.H. Biology and applications of Clonostachys rosea. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, J.C.; Liu, W.; Ma, J.; Brown, W.G.; Stewart, J.F.; Walker, G.D. Evaluation of the fungal endophyte Clonostachys rosea as an inoculant to enhance growth, fitness and productivity of crop plants. In Proceedings of the IV International Symposium on Seed, Transplant and Stand Establishment of Horticultural Crops, San Antonio, TX, USA, 3–6 December 2006; Translating Seed and Seedling. ISHS: Leuven, Belgium, 2006; Volume 782, pp. 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.C.L.; Silva, G.A.; Abib, P.H.N.; Carolino, A.T.; Samuels, R.I. Endophytic colonization of tomato plants by the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana for controlling the South American tomato pinworm Tuta absoluta. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2020, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.; Feng, L.; Li, Y.; Yue, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y. Endophytic fungi volatile organic compounds as crucial biocontrol agents used for controlling fruit and vegetable postharvest diseases. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddes, A.; Fauconnier, M.L.; Sassi, K.; Nasraoui, B.; Jijakli, M.H. Endophytic fungal volatile compounds as solution for sustainable agriculture. Molecules 2019, 24, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdiri, Y.; Lopes, T.; Rodrigues, N.; Silva, K.; Rodrigues, I.; Pereira, J.A.; Baptista, P. Biocontrol ability and production of volatile organic compounds as a potential mechanism of action of olive endophytes against Colletotrichum acutatum. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonglom, P.; Ito, S.I.; Sunpapao, A. Volatile Organic Compounds Emitted from Endophytic Fungus Trichoderma asperellum T1 Mediate Antifungal Activity, Defense Response and Promote Plant Growth in Lettuce (Lactuca sativa). Fungal Ecol. 2020, 43, 100867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, D.C.; de Paula, S.; Torres, A.G.; de Souza, V.H.M.; Pascholati, S.F.; Schmidt, D.; Dourado Neto, D. Endophytic fungi: Biological control and induced resistance to phytopathogens and abiotic stresses. Pathogens 2021, 10, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.A.; Ahmed, T.; Ibrahim, E.; Rizwan, M.; Chong, K.P.; Yong, J.W.H. A review on mechanisms and prospects of endophytic bacteria in biocontrol of plant pathogenic fungi and their plant growth-promoting activities. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akram, S.; Ahmed, A.; He, P.; He, P.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Munir, S.; He, Y. Uniting the role of endophytic fungi against plant pathogens and their interaction. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, G.E. Overview of mechanisms and uses of Trichoderma spp. Phytopathology 2006, 96, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Yang, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, X.; Wen, T.; Yuan, J. Learning from seed microbes: Trichoderma coating intervenes in rhizosphere microbiome assembly. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e03097-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Yang, J.; Zhao, S.; Yu, Q.; Weng, L.; Xiao, C. Root exudates influence rhizosphere fungi and thereby synergistically regulate panax ginseng yield and quality. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1194224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Lin, H.; Dong, Y.; Li, B.; He, Y. Effects of endophytes inoculation on rhizosphere and endosphere microecology of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) grown in vanadium-contaminated soil and its enhancement on phytoremediation. Chemosphere 2020, 240, 124891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, P.; Hrynkiewicz, K.; Szuba, A.; Jagodziński, A.M.; Al-Rashid, J.; Mandal, D.; Mucha, J. Metabolic niches in the rhizosphere microbiome: Dependence on soil horizons, root traits and climate variables in forest ecosystems. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1344205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Latorre, C.; Rodrigo, S.; Marin-Felix, Y.; Stadler, M.; Santamaria, O. Plant-growth promoting activity of three fungal endophytes isolated from plants living in dehesas and their effect on Lolium multiflorum. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A. Shaping plant growth beneath the soil: A theoretical exploration of fungal endophyte’s role as plant growth-promoting agents. MicrobiologyOpen 2025, 14, e70026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.; Tanvir, A.; Barasarathi, J.; Alsohim, A.S.; Mastinu, A.; Sayyed, R.; Nazir, A. Endophytes: Key role players for sustainable agriculture: Mechanisms, omics insights and future prospects. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 105, 1969–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Bhowmick, S.; Yadav, S.; Rashid, M.M.; Chouhan, G.K.; Vaishya, J.K.; Verma, J.P. Re-vitalizing of endophytic microbes for soil health management and plant protection. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, M.J.; Zabalgogeazcoa, I.; Vazquez de Aldana, B.R.V.; Martinez-Medina, A. Untapping the potential of plant mycobiomes for applications in agriculture. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2021, 60, 102034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, M.A.; Durán, P.; Hacquard, S. Microbial interactions within the plant holobiont. Microbiome 2018, 6, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisdall, J.M. Possible Role of Soil Microorganisms in Aggregation in Soils. Plant Soil 1994, 159, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyer, J.S.; Zuberer, D.A.; Nichols, K.A.; Franzluebbers, A.J. Soil Microbial Community Function, Structure, and Glomalin in Response to Tall Fescue Endophyte Infection. Plant Soil 2011, 339, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaughter, L.C.; Nelson, J.A.; Carlisle, A.E.; Bourguignon, M.; Dinkins, R.D.; Phillips, T.D.; McCulley, R.L. Tall Fescue and E. coenophiala Genetics Influence Root-Associated Soil Fungi in a Temperate Grassland. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Liang, X.; Zhang, G.; Li, Z.; Yang, Z.; Zhan, F. The coexistence of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and dark septate endophytes synergistically enhanced the cadmium tolerance of maize. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1349202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, Y.; Martínez, C.E.; Kao-Kniffin, J. Three Important Roles and Chemical Properties of Glomalin-Related Soil Protein. Front. Soil Sci. 2024, 4, 1418072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; McCulley, R.L.; McNear, D.H., Jr. Tall Fescue Cultivar and Fungal Endophyte Combinations Influence Plant Growth and Root Exudate Composition. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, O.Y.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Kuramae, E.E. Microbial Extracellular Polymeric Substances: Ecological Function and Impact on Soil Aggregation. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Tan, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, J. Unraveling the Role of Dark Septate Endophytes and Extracellular Polymeric Substances in Soil Aggregate Formation and Alfalfa Growth Enhancement. Rhizosphere 2025, 34, 101093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, B.A.; Strem, M.D.; Wood, D. Trichoderma Species Form Endophytic Associations within Theobroma cacao Trichomes. Mycol. Res. 2009, 113, 1365–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaszkó, T.; Szűcs, Z.; Kállai, Z.; Csoma, H.; Vasas, G.; Gonda, S. Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) of Endophytic Fungi Growing on Extracts of the Host, Horseradish (Armoracia rusticana). Metabolites 2020, 10, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, B.S. Volatile Hydrocarbons from Endophytic Fungi and Their Efficacy in Fuel Production and Disease Control. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2018, 28, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.X.; Lin, F.C.; Su, Z.Z. Endophytic Fungi—Big Player in Plant–Microbe Symbiosis. Curr. Plant Biol. 2025, 42, 100481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoysted, G.A.; Field, K.J.; Sinanaj, B.; Bell, C.A.; Bidartondo, M.I.; Pressel, S. Direct Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Carbon Exchanges between Mucoromycotina “Fine Root Endophyte” Fungi and a Flowering Plant in Novel Monoxenic Cultures. New Phytol. 2023, 238, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haichar, F.E.Z.; Heulin, T.; Guyonnet, J.P.; Achouak, W. Stable isotope probing of carbon flow in the plant holobiont. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2016, 41, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Valderrama, I.; Toapanta, D.; Miccono, M.D.L.A.; Lolas, M.; Díaz, G.A.; Cantu, D.; Castro, A. Biocontrol Potential of Grapevine Endophytic and Rhizospheric Fungi against Trunk Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 614620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, D.; Sharma, P.L.; Paul, P.; Baruah, N.R.; Choudhury, J.; Begum, T.; Karmakar, R.; Khan, T.; Kalita, J. Harnessing endophytes: Innovative strategies for sustainable agricultural practices. Discov. Bact. 2025, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stummer, B.E.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Warren, R.A.; Harvey, P.R. Quantification of Trichoderma afroharzianum, Trichoderma harzianum and Trichoderma gamsii Inoculants in Soil, the Wheat Rhizosphere and In Planta Suppression of the Crown Rot Pathogen Fusarium pseudograminearum. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 971–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabka, R.; d’Entremont, T.W.; Adams, S.J.; Walker, A.K.; Tanney, J.B.; Abbasi, P.A.; Ali, S. Fungal Endophytes and Their Role in Agricultural Plant Protection against Pests and Pathogens. Plants 2022, 11, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, M.; Ballard, R.A.; Wright, D. Soil microbial inoculants for sustainable agriculture: Limitations and opportunities. Soil Use Manag. 2022, 38, 1340–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomanga, K.E.; Lucas, S.S.; Mgenzi, A.R.; Simba, R.F.; Kiurugo, M.G.; Biseko, E. Review on the Mutual effects of Conservation Agriculture and Integrated Pest Management on Pest and Disease Control in Agriculture. Int. J. Curr. Sci. Res. Rev. 2022, 5, 3928–3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Reis, G.A.; Martínez-Burgos, W.J.; Pozzan, R.; Pastrana Puche, Y.; Ocán-Torres, D.; de Queiroz Fonseca Mota, P.; Rodrigues, C.; Lima Serra, J.; Scapini, T.; Karp, S.G.; et al. Comprehensive review of microbial inoculants: Agricultural applications, technology trends in patents, and regulatory frameworks. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syamsia, S.; Idhan, A.; Latifah, H.; Noerfityani, N.; Akbar, A. Alternative Medium for the Growth of Endophytic Fungi. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 886, 012045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Srivastava, A.; Garg, S.K.; Singh, V.P.; Arora, P.K. Incorporating omics-based tools into endophytic fungal research. Biotechnol. Notes 2024, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.R.; Doohan, F.M.; Hodkinson, T.R. From concept to commerce: Developing a successful fungal endophyte inoculant for agricultural crops. J. Fungi 2018, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Doilom, M.; Jeewon, R.; Hyde, K.D.; Manawasinghe, I.S.; Chethana, K.W.T.; Balasuriya, A.; Thakshila, S.A.D.; Luo, M.; Mapook, A.; et al. Challenges and update on fungal endophytes: Classification, definition, diversity, ecology, evolution and functions. Fungal Divers. 2025, 131, 301–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alori, E.T.; Babalola, O.O. Microbial inoculants for improving crop quality and human health in Africa. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saad, M.M.; Eida, A.A.; Hirt, H. Tailoring plant-associated microbial inoculants in agriculture: A roadmap for successful application. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 3878–3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.W.; Yang, Q.; Zhu, Y.L.; Zhou, J.; Sun, K.; Mei, Y.Z.; Dai, C.C. The construction of CRISPR-Cas9 system for endophytic Phomopsis liquidambaris and its PmkkA-deficient mutant revealing the effect on rice. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2020, 136, 103301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Huang, R.; Yin, W.B. An optimized and efficient CRISPR/Cas9 system for the endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis fici. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Batta, A.; Singh, H.B.; Srivastava, A.; Garg, S.K.; Singh, V.P.; Arora, P.K. Bioengineering of fungal endophytes through the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1146650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagita, R.; Quax, W.J.; Haslinger, K. Current state and future directions of genetics and genomics of endophytic fungi for bioprospecting efforts. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 649906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bünemann, E.K.; Bongiorno, G.; Bai, Z.; Creamer, R.E.; De Deyn, G.; De Goede, R.; Fleskens, L.; Geissen, V.; Kuyper, T.W.; Mäder, P.; et al. Soil quality–A critical review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 120, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaduri, D.; Sihi, D.; Bhowmik, A.; Verma, B.C.; Munda, S.; Dari, B. A review on effective soil health bio-indicators for ecosystem restoration and sustainability. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 938481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Class of Endophytes | Representative Fungal Genera | Common Host/Colonized Tissues | Transmission Mode | Ecological/Functional Roles | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 Clavicipitaceous (C-endophytes) | Epichloë, Neotyphodium | Grasses (Poaceae); mainly leaf sheaths, stems, and seeds | Vertical (seed-borne); occasionally mixed | Systemic colonization, drought tolerance, herbivore resistance via alkaloid production, and stress resilience | [5,25,26] |

| Class 2 Non-clavicipitaceous root-associated endophytes | Trichoderma, Clonostachys, Fusarium, Penicillium | Roots of cereals, legumes, and vegetables | Horizontal (soil- and rhizosphere-acquired) | Nutrient mobilization, abiotic stress tolerance, induced systemic resistance (ISR) induction, and VOC-mediated pathogen suppression | [5,27,28] |

| Class 3 Non-clavicipitaceous foliar/stem endophytes | Aspergillus, Alternaria, Colletotrichum, Cladosporium | Leaves and stems of various crops (e.g., maize, rice, and wheat) | Horizontal (airborne or phyllosphere sources) | VOCs and secondary metabolites for pathogen defense, stress mitigation, and sometimes latent pathogens | [22,29,30] |

| Class 4 Endophytic mycorrhiza-like (Dark septate fungi, AMF-related) | Phialocephala, Cadophora, Rhizophagus, Glomus | Root cortical tissues of cereals, pulses, and oilseeds | Horizontal (soil propagules and hyphal contact) | Nutrient acquisition (especially N and P), improved water uptake, modulation of rhizosphere microbiome, and soil aggregation | [5,31,32] |

| Seed-associated and reproductive endophytes | Epichloë, Trichoderma, Fusarium spp. | Seeds and reproductive organs of crops | Vertical or mixed (seed + environment) | Early plant protection, enhanced germination, seedling vigor, and microbiome assembly | [33,34] |

| Endophytic Fungus | Host Plant/Crop | Mechanism of Plant Growth Promotion | Observed Benefits | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trichoderma harzianum | Tomato, avocado, maize, and rice | Production of IAA, phosphate solubilization, siderophore release, and antagonism against soil pathogens | Enhanced germination, root growth, and disease resistance | [50,51,52] |

| Piriformospora indica (Serendipita indica) | Barley, maize, and rice | Symbiotic association enhancing nutrient uptake (P, N, and Zn), hormone modulation, and stress tolerance | Improved biomass, drought, and salt tolerance | [53,54] |

| Fusarium oxysporum (non-pathogenic strains) | Tomato and cucumber | Secretion of growth hormones (IAA and gibberellins), enhanced antioxidant enzyme activity, and induced systemic resistance | Increased yield and tolerance to abiotic stress | [55,56] |

| Penicillium chrysogenum | Wheat, lettuce, cabbage, croccoli, and orchid | Phosphate solubilization, siderophore production, and ACC deaminase activity | Improved nutrient uptake and shoot biomass | [57,58] |

| Aspergillus niger | Mung bean, cassava, and forage grass | Organic acid secretion, phosphate solubilization, and enzyme production | Enhanced P availability and root elongation | [59,60] |

| Chaetomium globosum | Maize, cotton, and wheat | Antagonistic metabolites, cellulase/chitinase production, and induced systemic resistance | Protection against root pathogens and improved vigor | [61,62] |

| Clonostachys rosea | Tomato, wheat, and soybean | Mycoparasitism, production of antifungal compounds, and phytohormones | Disease suppression and growth enhancement | [63,64] |

| Colletotrichum truncatum | Pepper, snakeweed, and cucumber | Modulation of host metabolism and nitrogen uptake and IAA synthesis | Enhanced photosynthesis and biomass accumulation | [65,66] |

| Talaromyces pinophilus | Wheat, rice, and maize | Production of siderophores, phosphate solubilization, and secretion of stress-protective enzymes | Improved nutrient efficiency and drought resilience | [67,68] |

| Purpureocillium lilacinum | Soybean, cotton, and cucumber | Root colonization, phytohormone production, and nematode antagonism | Improved root growth, yield, and nematode resistance | [69,70] |

| Beauveria bassiana | Maize and corn | Endophytic colonization, secondary metabolite production, insect deterrence, and growth promotion | Enhanced biomass and biocontrol potential | [71,72,73] |

| Alternaria alternata | Wheat, rice, and tomato | IAA synthesis, phosphate solubilization, and antioxidant modulation | Improved germination, nutrient uptake, and stress tolerance | [74,75] |

| Functional Category | Response Variable | Reported Effect Size (Range) | System/Context | Key Notes | Representative References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant growth | Shoot or total biomass | +10–35% | Cereals, legumes, and horticultural crops | Stronger under nutrient limitation and abiotic stress | [6,27,78] |

| Root biomass/root length | +15–50% | Root endophytes and AMF | Increased absorptive surface area | [5,38] | |

| Nutrient acquisition | Phosphorus uptake/P-use efficiency | +15–60% | AMF and non-AMF EFs | Organic acids + hyphal foraging | [10,81] |

| Nitrogen use efficiency | +10–40% | EF-primed rhizosphere | Microbiome-mediated mineralization | [111,112] | |

| Iron availability | +20–70% (relative uptake) | Siderophore-mediated | Enhanced micronutrient capture | [46] | |

| Soil microbiome | Microbial biomass C (MBC) | +10–45% | Conservation and low-input systems | Carbon-driven assembly | [36,112] |

| Enzyme activities (C, N, and P cycling) | +15–50% | EF-inoculated soils | Enhanced turnover rates | [113,114] | |

| Pathogen abundance | −20–70% | IPM and EF-based systems | Competitive exclusion + antibiosis | [115,116] | |

| Soil structure | Aggregate stability (WSA) | +5–30% | AMF-rich arable soils | GRSP-driven stabilization | [10,97] |

| Soil organic carbon | +5–25% (relative increase) | Long-term EF presence | Protected within aggregates | [117,118] | |

| Stress resilience | Drought/salinity tolerance indices | +15–45% | Abiotic stress conditions | Improved water and nutrient uptake | [102,103] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sadia, A.; Munshi, A.R.; Kataoka, R. Harnessing Endophytic Fungi for Sustainable Agriculture: Interactions with Soil Microbiome and Soil Health in Arable Ecosystems. Sustainability 2026, 18, 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020872

Sadia A, Munshi AR, Kataoka R. Harnessing Endophytic Fungi for Sustainable Agriculture: Interactions with Soil Microbiome and Soil Health in Arable Ecosystems. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):872. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020872

Chicago/Turabian StyleSadia, Afrin, Arifur Rahman Munshi, and Ryota Kataoka. 2026. "Harnessing Endophytic Fungi for Sustainable Agriculture: Interactions with Soil Microbiome and Soil Health in Arable Ecosystems" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020872

APA StyleSadia, A., Munshi, A. R., & Kataoka, R. (2026). Harnessing Endophytic Fungi for Sustainable Agriculture: Interactions with Soil Microbiome and Soil Health in Arable Ecosystems. Sustainability, 18(2), 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020872