Abstract

Greenwashing by unvalidated environmental labelling is increasingly common and highly problematic due to the potential to mislead consumers. This is especially concerning for products that pose health risks, including alcohol. As environmental sustainability becomes more important to consumers, it is vital to assess changes in the use of potentially misleading claims over time. Among the first studies of its kind globally, this study aimed to (i) develop a typology of environmental claims displayed on alcohol products in Australia, (ii) examine the prevalence of these claims to establish baseline data for ongoing tracking, and (iii) assess the provision of recycling information. Four claim categories were identified: sustainability, planet friendly, bio-related and carbon-related. Claims featured on 8% of the 5982 sampled products, with considerable variation between alcohol categories. Sustainability claims were the most prevalent (5%). Recycling information appeared on 72% of products. The results suggest ambiguous environmental claims are present although not yet widespread. In contrast, recycling information is much more common although not universal. These findings highlight the need to consider restrictions on unsubstantiated environmental claims on alcohol products that can mislead consumers. Further, a nationally standardised mandatory recycling label should be introduced to assist consumers in reducing their environmental impacts.

1. Introduction

Environmental issues are increasingly important to consumers, and companies across sectors have responded by displaying environmental sustainability information on their products [1]. This information can be useful if it is accurate and true, and if its meaning is clear; however there is growing concern that many manufacturers misrepresent the environmental impacts of their offerings through false, misleading or unsubstantiated environmental sustainability claims (hereafter referred to as ‘environmental claims’)—a practice known as greenwashing [2].

Greenwashing occurs when a company disseminates inaccurate, false or misleading information regarding its environmental impacts or goals [3,4]. While this practice is viewed by some as a deliberate “cynical attempt to boost sales without any meaningful underlying sensitivity or change in practice” [5], others suggest it can also occur inadvertently when a business has a poor understanding of its supply chain and environmental impacts [4,6]. Greenwashing commonly occurs through unsubstantiated or exaggerated claims about the environmental benefits of a product, vague or unclear environmental claims and the use of third-party certifications and logos in a misleading or confusing manner [3,7].

Greenwashing may be difficult to detect because the environmental information provided by a company to be entirely true and accurate yet still be misleading by diverting attention from harms [8]—such as those linked to the product itself (e.g., alcohol) or its broader environmental impact, which may be insubstantially remediated by the company’s green initiatives [4]. For example, marketing an alcohol product as having a ‘lower carbon footprint’, while possibly true, could distract from the harms associated with alcohol and therefore be misleading [9]. Similarly, marketing a product as having ‘recyclable packaging’ may be true but it could still be misleading if it does little to counter significant production-related environmental costs [4]. Concerns about this kind of marketing have led to calls for bans on the use of environmental claims by high-polluting businesses and sectors because such claims often contradict their overall environmental impact [10].

Regardless of how the greenwashing occurs, it is problematic, as evidence indicates that such claims are used as cues by consumers when making purchasing decisions, despite their credibility [11]. Meaningless environmental claims that provide no objectively useful information have been found to positively impact consumers’ perceptions, even among more environmentally knowledgeable and sceptical consumers [12]. Therefore, greenwashing can hinder consumers’ ability to make informed choices [4] and can result in consumers being willing to pay more for products with such claims due to the belief that they offer genuine environmental benefits [13].

While greenwashing is problematic across industries, it is especially an issue when it is used on products that cause health harms, such as alcohol, because of the potential to confuse consumers and encourage them to purchase the products. Alcohol consumption is a major risk factor for death and disease [14]. In recognition of the health harms it causes, many countries have introduced restrictions on the advertising of alcoholic beverages [15]. To enhance brand image in a manner that potentially sidesteps alcohol advertising restrictions, alcohol companies are adopting various strategies, such as the use of marketing claims on product packaging [16], including environmental claims [17]. Not only can greenwashing of alcohol products increase the appeal of a product, brand or alcohol use in terms of its environmental ‘credentials’ [18], it may distract consumers from properly evaluating information about the health harms of alcohol. This is likely to be especially problematic for young people, who are both highly impacted by alcohol-related harms [14] and more vulnerable to greenwashing because of their heightened concern with environmental issues [19]. As alcohol sales among youth have declined in recent decades [20], the use of greenwashing on products may be seen as an effective strategy to bolster sales to this group in particular.

Although there are growing concerns about greenwashing in the alcohol industry [17,21], research on the prevalence of alcohol products featuring environmental claims remains limited. From the one identified study, it appears that the prevalence of environmental claims on alcohol products has increased over time [18]. This study analysed the prevalence of eco-oriented claims on the packaging of 4024 new alcohol products released in the Australian market between 2013–2023, finding that while the prevalence of eco-oriented claims on newly introduced products was modest (6.3%), there was a significant increase in the prevalence of these claims over that time period (+8.3%). New wines demonstrated the highest prevalence of eco-oriented claims (12%); however, new beers saw the greatest increase in eco-oriented claims over the time period (+15.2%). Claims relating to sustainable production methods were the most prevalent type of eco-oriented claim (4.2%), followed by local ingredients claims (1.6%) and carbon neutral claims (1.1%).

In addition, little is known about the provision of recycling information on alcohol products. This information provides consumers with guidance on how to reduce their environmental impact through their disposal of product packaging [22]. Compared to the display of environmental claims, the provision of recycling information provides consumers with a direct mechanism for reducing their environmental footprint associated with their alcohol use. The extent of difference between industry use of these two approaches is therefore of interest.

To our knowledge, no recent study has comprehensively examined the prevalence of environmental claims on alcohol products available for sale. Up-to-date evidence is important because of the rapid emergence of environmental claims in other markets, including cosmetics, fashion and food [7,13,23], indicating that a similar trend may be occurring in the alcohol market. This study is among the first globally to analyse the use of environmental claims on a harmful product (i.e., alcohol), addressing a critical gap in understanding how greenwashing is being used by a health-harming commodity. Further, we did not locate any studies that assessed the prevalence of the provision of packaging recycling information, although some work regarding the prevalence of recycling information has been conducted for other products such as food, household goods and cosmetics [23].

The present study addresses these evidence gaps in the Australian context, where alcohol consumption levels are high by international standards [24], and where policy discussions are underway regarding greenwashing and packaging regulatory reform [25,26]. These policy developments could influence the presentation of environmental claims and recycling information on consumer goods in the future. In anticipation of these changes, we aimed to (i) develop a typology of environmental claims displayed on alcohol products, (ii) examine the prevalence of these claims to establish baseline data for ongoing tracking and (iii) assess the provision of recycling information. We assessed the prevalence of both claims and recycling information by product type and product origin (local (i.e., Australian) versus imported) to determine whether differences existed according to these attributes. Understanding these patterns offers valuable insights into the types and extent of environmental messaging and recycling information currently reaching Australian alcohol consumers via product packaging.

2. The Australian Regulatory Context

In Australia, there are no specific regulations that apply directly to the use of environmental claims on alcohol products. However, the Australian Consumer Law applies, which is monitored and enforced by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) [4]. Specifically, manufacturers are prohibited from making false or misleading representations or engaging in misleading or deceptive conduct or conduct that is likely to mislead or deceive [27]. Determining whether an environmental claim is in breach of these requirements is an objective question of fact for the court to determine [28,29]. However, the ACCC has outlined eight principles to help manufacturers comply with their obligations under the Australian Consumer Law when making environmental claims: “make accurate and truthful claims”, “have evidence to back up your claims”, “do not hide or omit important information”, “explain any conditions or qualifications on your claims”, “avoid broad and unqualified claims”, “use clear and easy-to-understand language”, “visual elements should not give the wrong impression” and “be direct and open about your sustainability transition” [4]. Environmental claims that do not comply with these principles may be considered ‘greenwashing’ and therefore in breach of Australian Consumer Law.

In addition to the Australian Consumer Law, various industry and government requirements may apply to specific types of environmental claims. For example, the Sustainable Winegrowing Australia certification is an industry standard that serves as an environmental claim when its logo is displayed on wine products [30]. Similarly, the Climate Active Carbon Neutral Organisation certification is a government standard that functions as a claim when its corresponding logo is featured on products [31]. A representation that a product or producer holds the certification may depend on certain standards being met and/or independent assessment and accreditation. The use of all such environmental claims also remains subject to the Australian Consumer Law as outlined above.

The regulatory environment for the provision of recycling information is even more complex. Along with observing the requirements of Australian Consumer Law when providing recycling information, the national co-regulatory framework for packaging—per the National Environmental Protection (Used Packaging Materials) 2011 Measure (Cth) (National Measure)—is also relevant [32]. Under this framework, brand owners have three regulatory options: they must either comply with the obligations set out by the relevant state or territory, adhere to the Australian Packaging Covenant or follow another approved arrangement that achieves equivalent outcomes [33]. Within this framework, a “brand owner” is defined as a person who owns the trademark under which a product is sold or distributed in Australia [33]. This definition extends to licensees and franchisees operating in Australia, as well as the first person to sell the product domestically in the case of imported goods [33]. However, this definition varies across Australian states and territories [32].

In New South Wales—the state in which the present study was conducted—the relevant regulation giving effect to the National Measure is the Protection of the Environment Operations (Waste) Regulation 2014 (NSW) (Waste Regulation) [34]. The definition of a “brand owner” under the Waste Regulation is similar to the National Measure [33,34]. The Waste Regulation does not apply to all brand owners—they are exempt if they meet one of the following criteria: (i) they are a signatory to the Covenant; (ii) they have another arrangement approved by the Environmental Protection Authority that produces the same outcomes as the Covenant; or (iii) they have a gross annual income in Australia of less than $5 million (AUD) [34]. Under the Waste Regulation, brand owners are obliged to ensure that consumers are provided with adequate information to manage packaging materials after use, including guidance on where to dispose of the materials and how to recycle or reuse them [34]. Notably, the Waste Regulation does not prescribe a requirement for recycling information to be present on the label of a product, or in a particular form.

The Australian Packaging Covenant (the Covenant) is an industry-led part of the national co-regulatory framework [35]. If a brand owner becomes a signatory to the Covenant (and therefore a member of the Australian Packaging Covenant Organisation (APCO)), they are required to submit an annual report based on the Packaging Sustainability Framework [36]. One of the criteria under this framework relates to disposal labelling and considers the extent to which packaging includes labelling that helps consumers understand how to dispose of it after use [36]. Recycling “symbols” and “advice” are considered relevant labels, along with the Australasian Recycling Label (ARL) [36]—an industry-designed recycling label for consumer packaging available to APCO members [25]. This criterion serves as a benchmark against which a brand owner’s performance is assessed and rated, rather than a legal requirement to provide recycling information [37].

Although the co-regulatory framework strongly encourages brand owners to include recycling information on consumer packaging, there are no mandatory recycling labelling requirements for such packaging in Australia [25]. An independent review of the framework highlighted the difficulties brand owners face in identifying their liability and obligations under the current framework, partly owing to its inconsistent implementation across states and territories [32]. Moreover, it found that inadequate monitoring and enforcement has “undermined confidence in the co-regulatory arrangement, enabled free riders and disincentivised participation in the Covenant” [32]. In response, the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water recently considered reforms to packaging regulation and proposed three regulatory reform options, two of which included mandatory recycling labelling [25]. However, the existing co-regulatory arrangement applies until new regulations are introduced [38].

In summary, environmental claims are voluntary, but if used must comply with the Australian Consumer Law, which prohibits false, misleading or deceptive representations/conduct. Claims may breach these requirements in a number of ways, including when they are broad, unqualified or hard to understand. In some cases, a manufacturer may have to abide by additional industry or government standards for the use of certain claims. Similarly, recycling information must not contravene Australian Consumer Law by being false, misleading or deceptive. Although there is currently no mandatory requirement for recycling labels on consumer packaging in Australia, the provision of recycling information is strongly encouraged under the existing co-regulatory framework and may become mandatory in the future.

In addition to regulations on environmental claims and the provision of recycling information, those governing country-of-origin information are relevant to this study. Australia has mandatory country-of-origin labelling requirements that apply to food per the Country of Origin Food Labelling Information Standard 2016 (Cth) [39]. Alcoholic beverages are considered ‘non-priority food’ under this standard. While the requirements that apply to food for standard marks and the placement of origin statements in a box are voluntary for non-priority foods, these foods are still required to carry a text statement regarding country of origin, such as ‘made in Australia’ [39].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

Data were collected from three major alcohol retailers (ALDI, Dan Murphy’s and BWS) between May and June 2024. Each store was located in the Sydney metropolitan area in NSW, Australia. Trained data collectors captured images of all sides of each product using a smartphone application [40]. Data entry personnel then analysed the images and extracted necessary information from the images, including product name, product type, ingredients, claims and recycling information and product origin information (manufactured within vs. outside Australia). This information was subsequently coded for analysis. Quality management procedures were in place to check the quality of images and the accuracy of coding. If the same product was present in multiple sizes (such as multi-pack and single-item products), these were treated as separate products to accurately represent the number of alcohol products in the market. Data from the outer layer of packaging on multi-pack products were extracted rather than the information on each individual item within a multi-pack product to reflect the information consumers have access to at the point of sale.

The dataset included 6239 products. Alcohol products were defined as those with over 1.15% alcohol by volume (ABV), resulting in the exclusion of 257 products. The final sample of 5982 products was divided into five categories for analysis: cider, spirits, beer, wine and premix. Products were classified as locally made if the label identified Australia as the country of origin; otherwise, they were classified as imported.

3.2. Types of Claims

An environmental claim was defined as any on-pack information that related to the natural environment or sustainability. Consistent with previous research [18], claims were excluded that could potentially meet the definition of an environmental claim but had stronger associations with health. These included claims containing the following words or their derivatives: ‘natural’, ‘organic’, ‘vegan’ and ‘GMO free’.

As part of a larger study, all claims in the dataset were classified according to their primary type (e.g., nutrition claims, environmental claims, country-of-origin claims). For the present study, the environmental claims were extracted for analysis. Using an approach aligned with ‘ideal-type analysis’, which is used to construct typologies from qualitative data by identifying groupings within the dataset [41], a single coder (LB) then grouped the claims by common characteristics. For example, ‘Sustainably farmed’ and ‘Sustainable’ share the concept of ‘Sustainability’, and were therefore grouped as ‘sustainability claims’. Similarly, ‘Carbon neutral’ and ‘Carbon positive’ are both related to carbon and were therefore grouped as ‘carbon claims’. This resulted in a typology of claim categories that was subsequently reviewed and refined by the broader research team, and all assessed claims were allocated to one environmental claim category.

3.3. Type of Recycling Information

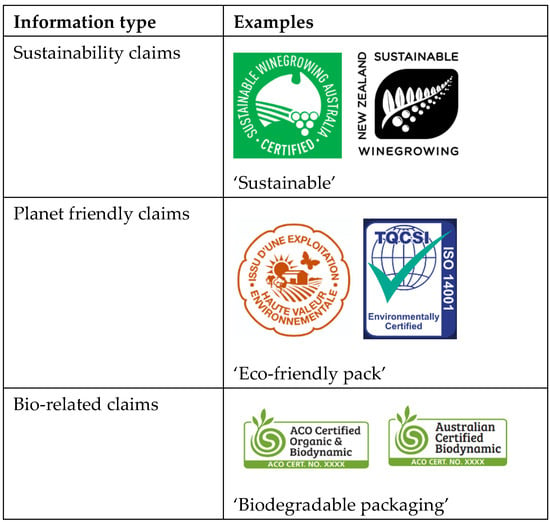

A product was considered to display recycling information if it featured text or images indicating that the product packaging was recyclable and/or provided instructions on how to recycle the packaging. To guide our identification, we referred to previous research that identified commonly used recycling claims and symbols in the Australian marketplace [23]. Figure 1 provides examples of the types of information that were classified as recycling information.

Figure 1.

Examples of environmental claims and recycling information on alcohol products.

3.4. Statistical Methods

Descriptive analyses were conducted in Stata 19.0, StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA, to determine the type and prevalence of environmental claims and recycling information. Analyses were conducted overall, by product type and by product origin (local or imported). To test whether the proportion of products featuring environmental claims differed across alcohol product categories, Fisher’s exact tests were used due to small sample sizes. When significant, post hoc pairwise z-tests with Bonferroni-adjusted alpha levels (α = 0.005) were conducted. The same procedure was used to compare environmental claims by country of origin, with a Bonferroni-adjusted alpha of 0.05. For recycling information, chi-squared tests were used to examine differences by product category, followed by post hoc pairwise z-tests (Bonferroni-adjusted α = 0.005). Comparisons by country of origin were also conducted using chi-squared tests and the same post hoc approach, with a Bonferroni-adjusted alpha of 0.05.

4. Results

Environmental claims were present on 8% of the sampled alcohol products. Four major categories of environmental claims were identified: sustainability, planet friendly, bio-related and carbon-related (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Typology of environmental claims identified on alcohol packaging.

Assessed environmental claims included both text and logo claims on any part of the product packaging, including in the product or manufacturer’s name. Among the different claim categories, sustainability claims were the most common (5%), followed by carbon-related claims (2%), planet friendly claims (1%) and bio-related claims (<1%) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Number and percentage of products with environmental claims and recycling information (n = 5982).

Beer products had a significantly higher prevalence of environmental claims compared to all other product types, with 15% of sampled beers featuring at least one claim (see Table 3). Almost all claims on beer products were carbon-related (14%), with smaller proportions being planet friendly (1%) and sustainability claims (<1%).

Table 3.

Prevalence of environmental claims by product and claim type.

One in 10 wine products (10%) featured at least one environmental claim. Among these, sustainability claims were the most common (8%), being significantly more prevalent on wines than all other product types except cider. Planet friendly claims were the next most prevalent environmental claim type on wine products (1%), followed by carbon-related (1%) and bio-related claims (<1%).

Claims were infrequently displayed on spirits, premix or ciders, with a prevalence of between 2–3% in these product categories. Carbon-related claims were the most prevalent claim type on spirits (1%) and premix (2%), while sustainability claims were the only claim type observed on cider products (2%).

The prevalence of environmental claims was relatively similar between imported (7%) and locally made products (8%); however, variations were observed within product categories (see Table 4). Claims were significantly more common on locally made beers compared to imported products (18% vs. 0%). Similarly, the prevalence of claims on locally made ciders (3% vs. 0%), spirits (3% vs. 1%) and premix (3% vs. 0%) was higher relative to imported products. By contrast, a significantly lower prevalence of claims was found on local (9%) versus imported wines (12%).

Table 4.

Prevalence of environmental claims and recycling information by product type and by product origin.

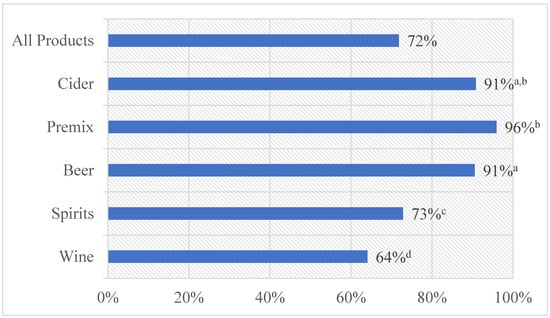

With respect to recycling information, almost three-quarters (72%) of the assessed products featured this information (see Figure 2). However, once again, prevalence varied considerably by product category. Premix products (96%), beers (91%) and ciders (91%) were most likely to display recycling information. Spirits (73%) and wines (64%) had a significantly lower prevalence compared to the other product categories.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of recycling information by product type. Note: Proportions with the same superscript letter did not significantly differ from each other at a Bonferroni adjusted alpha level of 0.005.

The prevalence of recycling information was significantly lower on local (70%) compared to imported (75%) products. When assessed by product category, recycling information appeared on a significantly higher proportion of locally made spirits (81%) and beers (92%) compared to imported spirits (61%) and beers (83%). Local wines had a significantly lower prevalence of recycling information than imported wines (60% vs. 70%), while there was no difference in prevalence between local and imported premix products (both 96%).

5. Discussion

5.1. Environmental Claims

Environmental claims were present but not widespread on the alcohol products assessed in this study. Overall prevalence was 8%, but there was variation across alcohol product categories, perhaps reflecting differing marketing strategies that are tailored to appeal to specific consumer segments [13]. For instance, sustainability claims were the most common overall—being most prevalent on wine products. However, the beer category had a significantly higher overall prevalence of environmental claims. This may reflect manufacturers’ efforts to orient their products toward particular consumer groups [42]. For instance, as young people are drinking less alcohol, with especially large reductions seen in beer consumption [43], manufacturers may be increasing the use of environmental claims to boost sales in this demographic group. This could be an effective strategy, given that young people tend to be more concerned about environmental issues than other groups [44]. About 14% of beers sampled featured a carbon-related claim—a significantly greater proportion than for any other product category and nearly seven times more prevalent than carbon-related claims on premix, the next highest contender. It is unclear whether this finding reflects a strategic attempt by industry to appeal to a particular market segment. Further research is needed to understand consumer perceptions of the environmental impacts associated with different types of alcohol products and whether this influences their purchasing intentions.

Rather than providing useful information, many of the identified claims were broad and unclear in their meaning and as such could constitute greenwashing [4]. For example, some products carried ‘sustainably made’ and ‘eco-friendly’ claims without providing further substantiating information. With these types of claims, it is not possible to know whether the producer is referring to the raw ingredients used to make the alcoholic beverage, the process of manufacturing the beverage, the packaging and labelling or the delivery methods. Similar claims have been identified across a range of other consumer product sectors and described as warranting particular attention due to their potential to confuse or mislead consumers [7].

The emergence of such claims is particularly concerning because the production of alcohol contributes to environmental harms such as high water usage, wastewater pollution and greenhouse gas emissions [17], despite what some claims may imply [21]. Of the environmental claims analysed, sustainable claims were by far the most common, appearing most frequently on wine products. This may reflect industry efforts to align with consumer demand—recent industry research found that a majority of wine consumers across five major international wine markets cared about sustainability and were increasingly seeking to purchase sustainably produced wines [45]. Omitting information about the overall environmental impacts of production of the product while simultaneously using ‘broad and unqualified’ claims could be considered greenwashing because of the potential to mislead consumers into believing that the product is environmentally beneficial overall when this may not be the case. The ACCC has therefore advised that it is good practice to make any evidence that substantiates a claim as easy to locate and understand as possible, such as by providing the evidence alongside the claim; or if it cannot be provided directly on the packaging, using a brochure, dedicated website or QR code to provide further details [4]. Although the vague nature of many claims in our sample indicates greenwashing, further research is needed to determine the extent to which these claims are false or inaccurate. Further research is also needed to understand whether such claims, while technically accurate, might mislead consumers in the sense that they distract from other environmental harms or health harms associated with the product.

Locally made and imported products featured roughly the same prevalence of claims overall; however differences were observed by product category. Notably, claims were significantly more prevalent on local beers, with nearly one-fifth of local beers but no imported beers featuring a claim. Most locally produced beer is consumed within the Australian market and beer consumption in Australia is the lowest it has been in 65 years [46]. Moreover, the Australian brewing industry is said to be among the “most advanced in the world”, and many Australian brewers are investing in technology aimed at reducing their emissions and overall environmental impacts [47]. As such, local producers may be seeking to boost sales by highlighting their ‘world class’ environmentally positive practices through environmental claims. The reasons for the differences in the prevalence of claims between other alcohol types are less clear and warrant further research.

5.2. Recycling Information

In contrast to environmental claims, recycling information was widely featured on alcohol products (72%). Prevalence varied across alcohol product types being significantly higher on premix products relative to all other product categories except cider. Wine had a significantly lower prevalence of recycling information compared to all other product categories. The reasons for these observed differences are unclear. One possible explanation for the high prevalence on premix products is that it indicates industry efforts to appeal to young people, as premix products are often marketed to this group [48]. Providing recycling information to these more environmentally conscious consumers could enhance their sense of actively contributing towards reducing environmental harm. Conversely, the lower prevalence on wine products may reflect a preference among manufacturers for minimalist or sophisticated branding [49], thus avoiding additional labelling to maintain a refined aesthetic. Additionally, wine is predominantly packaged in glass containers [50], widely recognised by consumers as recyclable [51]. However, further research is needed to understand whether the provision of recycling information at all and in particular formats, is intended to appeal to specific market segments. The prevalence of recycling information was significantly lower on local compared to imported products overall but there was variation between product categories.

The majority presence of recycling information is likely to be a result Australia’s co-regulatory framework, where recycling information is not legally required on product labels, but producers are strongly encouraged to provide guidance on appropriate packaging disposal. The incomplete uptake of recycling information on all products may reflect the difficulties of applying the co-regulatory framework. Such challenges may arise due to jurisdictional differences that create ambiguity around obligations [32], compounded by the varying scope of recycling operations across Australian states and territories, and even between local councils [4]. This complexity makes it difficult for brand owners to give accurate disposal guidance, increasing the risk of providing wrong information. In an effort to mitigate this risk, it is possible that recycling information may be omitted from product packaging. Alternatively, the incomplete provision of recycling information across products could reflect the use of non-recyclable packaging materials, as it has been identified that not all packaging in the Australian market has good recycling potential [25]. Both issues—uncertainty around regulatory obligations and the use of non-recyclable packaging—were highlighted in the government’s recent consultation paper on packaging regulatory reform [25]. Future reforms may help facilitate more consistent inclusion of recycling information on both locally made and imported products.

5.3. Study Implications

Being among the first studies of its kind globally, our study provides initial evidence for the need to implement strategies to restrict greenwashing of alcohol products. Given that most of the identified claims were broad and lacked specificity, a precautionary approach should be taken whereby the use of environmental claims on alcohol products is prohibited, given that such claims may deflect from the health, social and environmental harms caused by alcohol production and consumption [17,20,52]. However, if this approach is not taken, at the very least, regulation should establish clear rules for when and how environmental claims may be made on alcohol products. Rather than self-regulation, which has been criticised for ineffectively protecting populations [53], yet is commonplace in the alcohol industry [16], regulation should be in the hands of an independent statutory agency [9], such as the ACCC.

Consumers desire clear information on how to recycle products [54]. Yet, the current regulatory framework contributes to confusion about how to properly dispose of packaging [25]. This confusion can lead to incorrect separation of packaging materials for recycling, contaminating waste streams and reducing the quality, value and consistency of recycled materials [25]. Moreover, unclear manufacturer obligations and liabilities under the framework may contribute to the lack of recycling information on alcohol products. To address these issues, regulatory reform is needed and is currently underway. As part of these reforms, mandating a standardised, easy-to-understand recycling labelling on all consumer goods—including alcohol products—should be a priority. Such labelling could improve recycling outcomes, prevent consumer confusion and better help individuals to minimise their environmental impact.

5.4. Study Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has several limitations of note. First, as it included data from products collected in-store from three alcohol retailers located in Sydney, the sample may not be representative of the entire Australian alcohol supply. However, the alcohol industry is dominated by large national and international suppliers [55], making it likely that products available for purchase in Sydney are similar to those sold elsewhere around the country. Second, this study focused on text and logo claims located on the package of physical alcohol products. Future research should assess the prevalence of visual elements such as graphics and pictures (e.g., of trees, mountains, waves, animals), which also constitute a form of claims and can contribute to greenwashing [4,56], as well as claims made in the online retail environment. Third, this research focused solely on environmental claims, although the concept of sustainability also includes social and economic considerations [57]. Future research should also assess the prevalence of claims relating broader corporate social responsibility and transparency of supply-chain activities, such as ‘B Corporation’ or ‘Fairtrade’, which were excluded from this analysis due to their broader scope than environmental issues. Finally, this study did not assess how consumers interpret environmental claims on alcohol products or how they are influenced by such content. This is an important area for future research to identify the extent to which consumers are misled or distracted by such claims, potentially resulting in increased alcohol consumption.

6. Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrate that while environmental claims are not yet widespread on alcohol products, they are present and in their current ‘generic’ form may be contributing to greenwashing. These claims can mislead consumers about the environmental impacts of alcohol and have the potential to distract from the harms caused by alcohol, with young people being particularly vulnerable due to their greater concerns about the environment. Stronger regulation is needed to prevent greenwashing and ensure that environmental sustainability messaging does not draw consumers’ attention away from the harms associated with alcohol. In contrast, recycling information is widespread on alcohol products, but a fragmented regulatory approach may be preventing this information from being adequate, accurate and present on all products. Regulatory reforms are needed to address these issues. As part of this, mandating a standardised recycling label should be prioritised as it could prevent consumer confusion and provide the necessary information to minimise the environmental impact of alcohol packaging.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: L.B. and S.P.; Methodology: L.B., A.Y. and S.P.; Formal analysis: L.B. and A.Y.; Funding acquisition: S.P., J.B., P.O. and M.I.J.; Investigation: B.S., A.Y. and S.P.; Writing—original draft: L.B.; Writing—review and editing: S.P., A.Y., S.H., P.O., J.B., M.I.J. and B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (APP2021186). S.P. is funded by NHMRC Investigator Grant #2034602. M.J. is funded by NHMRC Investigator Grant #1194713.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Simone Pettigrew.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Szabo, S.; Webster, J. Perceived greenwashing: The effects of green marketing on environmental and product perceptions. J. Bus. Ethics. 2021, 171, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Montgomery, A.W. The means and end of greenwash. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikkha, V.; Agarwal, P.; Rajwanshi, R. Assessing greenwashing practices with special relevance to the food & beverage industry. Int. J. Env. Agric. Res. 2024, 10, 472–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Competition & Consumer Commission. Making Environmental Claims: A Guide for Business; Australian Competition & Consumer Commission: Canberra, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton, F.; Houghton, S.; Doherty, D.O.; McInerney, D.; Duncan, B. ‘Greenwashing’ tobacco products through ecological and social/equity labelling: A potential threat to tobacco control. Tob. Prev. Cessat. 2018, 4, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, T.; Denner, N. Different shades of green deception. Greenwashing’s adverse effects on corporate image and credibility. Public Relat. Rev. 2025, 51, 102521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Competition & Consumer Commission. Greenwashing by Businesses in Australia: Findings of the ACCC’s Internet Sweep of Environmental Claims; Australian Competition & Consumer Commission: Canberra, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hastak, M.; Mazis, M. Deception by Implication: A Typology of Truthful but Misleading Advertising and Labeling Claims. J. Public Policy Mark. 2011, 30, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.; Schoenberger, S.; Keen, J. People, Planet, or Profit: Alcohol’s Impact on a Sustainable Future; The Institute of Alcohol Studies: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, C.; Bagnara, J.; Parker, C.; Obeid, A. Seeing Green—Prevalence of Environmental Claims on Social Media; Consumer Policy Research Centre: Melbourne, Australia; The ARC Centre of Excellence for Automated decision-Making and Society: Melbourne, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, L.; Kim, Y. “I Drink It Anyway and I Know I Shouldn’t”: Understanding Green Consumers’ Positive Evaluations of Norm-violating Non-green Products and Misleading Green Advertising. Environ. Commun. 2015, 9, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.J.; Rotman, J.; Weber, V.; Kumar, P. How meaningless and substantive green claims jointly determine product environmental perceptions. Int. J. Advert. 2025, 44, 396–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nes, K.; Antonioli, F.; Ciaian, P. Trends in sustainability claims and labels for newly introduced food products across selected European countries. Agribusiness 2024, 40, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health and Treatment of Substance Use Disorders; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Scobie, G.; Patterson, C.; Rendall, G.; Brown, L.; Whitehead, R.; Scott, E.; Greci, S.; Donaghy, G.; Pulford, A.; Scott, S. Review of Alcohol Marketing Restrictions in Seven European Countries; Public Health Scotland: Edinburgh, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Reducing the Harm from Alcohol—By Regulating Cross-Border Alcohol Marketing, Advertising and Promotion: A Technical Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, M.; Critchlow, N.; O’Donnell, R.; MacLean, S. Alcohol’s contribution to climate change and other environmental degradation: A call for research. Health Promot. Int. 2024, 39, daae004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, A.; Dixon, H.; Wakefield, M. Virtue marketing: Trends in health-, eco-, and cause-oriented claims on the packaging of new alcohol products in Australia between 2013 and 2023. J. Stud. Alcohol. Drugs. 2024, 85, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L. The Interplay Between Knowledge, Perceived Efficacy, and Concern About Global Warming and Climate Change: A One-Year Longitudinal Study. Risk Anal. 2012, 32, 1003–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J.; Fairbrother, H.; Livingston, M.; Meier, P.S.; Oldham, M.; Pennay, A.; Whitaker, V. Youth drinking in decline: What are the implications for public health, public policy and public debate? Int. J. Drug Policy 2022, 102, 103606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- bigalcohol.exposed. Unveiling Greenwashing: Absolut Vodka’s Paper Bottle Initiative and Sustainability Challenges in the Alcohol Industry. Available online: https://bigalcohol.exposed/unveiling-greenwashing-absolut-vodkas-paper-bottle-initiative-and-sustainability-challenges-in-the-alcohol-industry/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Buelow, S.; Lewis, H.; Sonneveld, K. The role of labels in directing consumer packaging waste. Manag. Environ. Qual. An. Int. J. 2010, 21, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Council of Recycling. Audit and Review of Packaging Environmental Labelling and Claims; Australian Council of Recycling: Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Alcohol, Tobacco & Other Drugs in Australia. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/alcohol/alcohol-tobacco-other-drugs-australia/contents/data-by-region/international-comparisons (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Department of Climate Change Energy the Environment and Water. Reform of Packaging Regulation: Consultation Paper; Department of Climate Change Energy the Environment and Water: Canberra, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of Australia. Greenwashing. Available online: https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Environment_and_Communications/Greenwashing (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Australian Government. Competition and Consumer Act 2010, Schedule 2 Australian Consumer Law. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/C2004A00109/latest/text (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Nonchalant Pty Ltd. (in liq) [2013] FCA 605 [10].

- Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd. (2009) 238 CLR 304 [102].

- Sustainable Winegrowing Australia. The Certification Process. Available online: https://sustainablewinegrowing.com.au/membership/the-certification-process/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Climate Active. About Us. Available online: https://www.climateactive.org.au/what-climate-active/about-us (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Matthews Pegg Consulting Pty Ltd. Review of the Co-Regulatory Arrangement Under the National Environment Protection (Used Packaging Materials) Measure 2011—Final Report; Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment: Canberra, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Department of Climate Change Energy the Environment and Water. National Environment Protection (Used Packaging Materials) Measure 2011; Australian Government Department of Climate Change Energy the Environment and Water: Canberra, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- NSW Government. Protection of the Environment Operations (Waste) Regulation 2014 (NSW). Available online: https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/sl-2014-0666 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- APCO. The Australian Packaging Covenant. Available online: https://apco.org.au/the-australian-packaging-covenant (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- APCO. Packaging Sustainability Framework. Available online: https://apco.org.au/packaging-sustainability-framework (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- APCO. Covenant Obligations. Available online: https://apco.org.au/covenant-obligations (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Department of Climate Change Energy the Environment and Water. Reforming Packaging Regulation. Available online: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/protection/waste/packaging/reforming-packaging-regulation (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Australian Government. Country of Origin Food Labelling Information Standard 2016. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/F2016L00528/latest/text (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Dunford, E.; Trevena, H.; Goodsell, C.; Ng, K.H.; Webster, J.; Millis, A.; Goldstein, S.; Hugueniot, O.; Neal, B. FoodSwitch: A Mobile Phone App to Enable Consumers to Make Healthier Food Choices and Crowdsourcing of National Food Composition Data. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2014, 2, e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapley, E.; O’Keeffe, S.; Midgley, N. Developing Typologies in Qualitative Research: The Use of Ideal-type Analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2022, 21, 16094069221100633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Villegas, R.; Bernabéu, R.; Rabadán, A. Effects on beer attribute preferences of consumers’ attitudes towards sustainability: The case of craft beer and beer packaging. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 15, 101050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movendi International. Big Alcohol Targets Millennials with “Wellness” Products, Youth-Specific Marketing; Movendi International: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Salguero, R.B.; Bogueva, D.; Marinova, D. Australia’s university Generation Z and its concerns about climate change. Sustain. Earth 2024, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wine Australia. How Consumers are Responding to Sustainability. Available online: https://www.wineaustralia.com/news/market-bulletin/issue-302 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Wynne, T. Craft Beer—Bucking the Trend in Australia. Available online: https://www.deloitte.com/au/en/Industries/consumer-products/perspectives/craft-beer-bucking-the-trend-in-australia.html (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Brewers Association of Australia. Australian Brewing: Our Economic and Social Contribution; Brewers Association of Australia: Griffith, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, J.; Stevenson, R.J.; Gates, P.; Dillon, P. Young Australians and alcohol: The acceptability of ready-to-drink (RTD) alcoholic beverages among 12–30-year-olds. Addiction 2007, 102, 1740–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prestige Wine Labels. Minimalist Chic with the Rise of Simplicity in Wine Label Art. Available online: https://prestigewinelabels.au/minimalist-chic-with-the-rise-of-simplicity-in-wine-label-art/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Ruggeri, G.; Mazzocchi, C.; Corsi, S.; Ranzenigo, B. No more glass bottles? Canned wine and Italian consumers. Foods 2022, 11, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Feo, G.; Ferrara, C.; Minichini, F. Comparison between the perceived and actual environmental sustainability of beverage packagings in glass, plastic, and aluminium. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 333, 130158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidler, A.-C.; Bury, K. Making Every Global Crisis a Marketing Opportunity: Alcohol Industry Corporate Activism; Intouch Public Health: Canberra, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Keric, D.; Stafford, J. Proliferation of ‘healthy’ alcohol products in Australia: Implications for policy. Public Health Res. Pract. 2019, 29, e28231808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleanaway. Recycling Behaviours Report 2024; Cleanaway: Melbourne, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, M. Liquor Retailing in Australia; IBISWorld: Melbourne, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, A.; Chen, Y.J.M.; Dixon, H.; Ng Krattli, S.; Gu, L.; Wakefield, M. Health-oriented marketing on alcoholic drinks: An online audit and comparison of nutrition content of Australian products. J. Stud. Alcohol. Drugs. 2022, 83, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, G.J.; Best, M. An exploration of consumer perceptions of sustainable wine. J. Wine Res. 2023, 34, 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.