Abstract

Contemporary environmental challenges necessitate the adoption of active learning methods within educational frameworks, particularly those that foster the development of environmental awareness among young people. The 2030 Agenda underscores the importance of project-based learning as a strategy for building the competencies required to achieve sustainable development goals. In this context, the attitudes and behavior of young people towards the environment serve as critical indicators of future social transformations within the sphere of sustainable development. The aim of this research was to determine whether project-based learning in geography, as opposed to traditional teaching methods, exerts a more pronounced influence on the formation of environmental values, attitudes, and pro-environmental behavior among students in their final year of primary school. The research was conducted using a convenience sample (n = 255) and employed pedagogical experimental surveys with parallel group designs. In the experimental group, project-based learning was implemented, whereas the control group continued with traditional teaching approaches. To assess environmental values and attitudes, the research employed a scale grounded in the EAATE framework, and pro-environmental behavior was evaluated using a measurement scale derived from the PEB and GEB scales. The obtained results are attributed to the influence of project-based learning. Although they cannot be generalized to the entire population, they indicate the potential of project-based learning as a more effective strategy in environmental education. Furthermore, these findings provide opportunities for further professional and scientific research in this area.

1. Introduction

Contemporary society is confronted with an escalating ecological crisis and is increasingly focused on identifying sustainable solutions that will foster a lasting balance between human needs and the preservation of nature and its systems. In this context, education is regarded as a fundamental mechanism for shaping future generations that will be able to act responsibly in alignment with the principles of sustainable development. Young people play a crucial role in the pursuit of sustainability, a fact explicitly highlighted in the 2030 Agenda [1], since they have been recognized as the primary agents of future societal change. The choices young people make—ranging from career paths to family roles and everyday habits—will position them as key contributors to sustainable development initiatives in the future. Given the decisive impact young people will have on the future direction of global ecological processes, contemporary approaches to environmental education increasingly emphasize the cultivation of eco-centric values and the promotion of pro-environmental behavior among students. This educational focus seeks to empower youth to integrate sustainability into their personal and collective actions, thus shaping a more responsible and ecologically conscious society.

Research in the field of environmental education demonstrates that traditional teaching approaches, primarily based on lectures, presentations and reliance on textbooks, tend to facilitate the development of declarative knowledge, but not the formation of enduring values, attitudes and pro-environmental behavior among students [2,3]. On the other hand, active teaching methods that incorporate Project-Based Learning (PjBL) have increasingly been recognized as a more effective than traditional ones because they help foster experiential learning, critical thinking, active student participation in solving problems in their local communities, as well as development of environmental values and pro-environmental behavior [4].

Since project-based learning involves integrative approach that blends problem-based learning and independent research, it also enables students to develop cognitive, emotional, social, and behavioral competencies. Research has shown that project-based learning contributes not only to the acquisition of procedural knowledge but also to the development of essential skills and attitudes that underpin students’ interests and motivation, which presents the key prerequisite for adopting eco-centric values and pro-environmental behavior.

However, project-based learning is still not sufficiently implemented, which indicates the existence of a gap between theoretical recommendations and the teaching practice. Despite the recognized theoretical importance of integrative and active teaching strategies, in primary education in general, and in geography teaching in Serbia, traditional teaching methods continue to prevail, relying heavily on lectures, presentations and the use of textbooks [5]. As a result, such teaching turns students mostly into passive recipients of knowledge. It also restricts opportunities for the development of environmental attitudes and limits the likelihood of students adopting pro-environmental behavior [2,3]. Research in the field of environmental education has identified two contrasting perspectives on how environmental values and attitudes are formed.

One group of authors emphasizes the anthropocentric approach, which prioritizes environmental protection primarily in terms of its benefits to human well-being [6], while another group highlights the eco-centric approach, which values nature independently of its usefulness to humans [7,8]. Although both approaches can lead to development of pro-environmental behavior, research indicates that the eco-centric orientation demonstrates a stronger predictor of such behavior [9]. Given these insights, the question of which teaching strategies are most effective in encouraging the development of different value orientations has emerged as a central concern in contemporary pedagogical theory and practice.

Pro-environmental behavior can be defined as the conscious and deliberate actions taken by an individual aimed at minimizing negative impact on the natural environment [10]. It is evident in numerous aspects of daily life: consumer habits and choices, rational use of electricity and water, selective waste disposal, use of public transportation, responsible attitude towards the protection of plant and animal life, as well as active participation in pro-environmental community events and actions [2,8,9,11].

It is only when these environmentally responsible behaviors become lasting habits that a person can truly be regarded as ecologically conscious [12,13]. The complexity of developing desirable forms of behavior during one’s education is reflected in the need for teaching, despite numerous objective and subjective social constraints, to provide students with clear arguments, vision, and goals related to pro-environmental action within the context of contemporary society.

Over the past several decades, extensive research has led to the creation of multiple theoretical frameworks aimed at understanding the motivations behind pro-environmental behavior, as well as which obstacles may slow down or prevent the adoption of such behavior. These theories emphasize the influence of a wide array of psychological and situational variables, including institutional structures, economic realities, social dynamics, and cultural contexts that shape one’s behavior. Bearing this in mind, the impact of environmental education and teaching strategies (project-based learning, discovery learning, and problem-based learning) is increasingly highlighted within educational research. This method is particularly valued for its effectiveness in facilitating the acquisition of relevant knowledge and practical experiences. It also enhances not only the comprehension of key concepts but also stimulates the development of environmental awareness and contributes to the formation of sustained patterns of pro-environmental behavior [14].

Building upon the previously outlined theoretical and practical frameworks, this research centres on the practical implementation of project-based learning in geography and its role in fostering pro-environmental attitudes among students. Specifically, the main focus of the research is to answer the following questions: (1) To what extent does project-based learning contribute to the development of eco-centric and anthropocentric attitudes, as well as pro-environmental behavior, in comparison to traditional teaching approaches? (2) Are there statistically significant differences in the attitudes of students from the experimental and control groups with regard to the observed categories? The aim of this research is to determine whether project-based learning, as opposed to traditional teaching such as lecture, illustrative-demonstrative, and dialogue-based approaches, has a statistically significant impact on the development of students’ anthropocentric and eco-centric values and attitudes, and on their pro-ecological behavior in their daily lives.

The initial null hypotheses of the research are as follows:

- There is no statistically significant difference between students in the experimental group and those in the control group regarding the development of anthropocentric and eco-centric values and attitudes at the initial testing;

- There is no statistically significant difference between students in the experimental group and those in the control group regarding the development of anthropocentric and eco-centric values and attitudes at the final testing;

- There is no statistically significant difference between students in the experimental group and those in the control group concerning the development of pro-environmental behavior at the initial testing;

- There is no statistically significant difference between students in the experimental group and those in the control group concerning the development of pro-environmental behavior at the final testing;

This research holds considerable importance by advancing empirical understanding of how teaching methods and strategies influence the development of ecological values and pro-environmental behavior among students. One of its central contributions is providing evidence-based insights into the effectiveness of project-based learning in comparison with traditional approaches. The practical significance of this research is further underscored by the detailed guidelines and models it offers to teachers seeking to enhance their teaching practice. The project-based learning frameworks and research results presented in this paper serve as valuable resources for teachers, enabling them to design project-oriented lessons focused on sustainable development. They also help teachers understand the underlying mechanisms that foster the growth of ecological values and pro-environmental behavior within the classroom. Moreover, the findings of this research have broader implications for educational policymakers. By providing concrete evidence of the benefits of project-based learning, the research supports the argument for revising curricula to better align with sustainable development goals. In addition to expanding the knowledge base regarding the impact of various teaching methods and strategies on development of environmental attitudes and behaviors, this research provides space for inquiry and future questions on the topic.

2. Research Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

Over the past few decades, there has been significant progress in the development of various theoretical frameworks aimed at understanding the factors that influence pro-environmental behavior. For example, according to the Theory of Environmentally Responsible Behavior—ERB [13]—the intention to act is central, supported by factors such as self-control, values and attitudes, a sense of personal responsibility, and necessary knowledge and skills. The Theory of Planned Behavior—TPB [15]—emphasizes that intentions, along with objective situational factors, serve as the direct determinants of pro-environmental behavior. These intentions develop through the interaction between cognitive elements (knowledge and skills) and socio-psychological variables (self-control, attitudes, and a sense of responsibility). In this framework, behavior is influenced by beliefs about the outcomes of one’s actions, prevailing social norms, and contextual conditions that can either encourage or constrain pro-environmental behavior. Similarly, the Theory of Reasoned Action—TRA [16]—asserts that behavior is shaped by the degree to which individuals value the outcomes of their actions. Here, attitudes are rooted in personal norms and beliefs, and intentions, which derive from them, directly influence the behavior. Finally, the Value–Belief–Norm Theory of Environmentalism [10] highlights the role of environmental values and attitudes in forming a distinct worldview. This perspective leads individuals to develop beliefs about the negative consequences of their actions on both natural and anthropogenic objects of value. Such beliefs shape the perception of responsibility and contribute to the formation of intentions and behaviors that are aligned with environmental protection. Research by Barr [9] indicates that environmental values and attitudes serve as the principal foundation for pro-environmental behavior. These elements are critical because they have a direct influence on an individual’s intention to engage in actions that benefit the environment. In addition, situational and psychological variables also play an important role in determining pro-environmental behavior. Psychological factors include a range of attributes such as personal responsibility, respect of moral norms, self-efficacy, self-control and personal beliefs. Additionally, awareness of environmental risks and an understanding of the broader, global consequences of human actions are crucial in shaping environmentally responsible behavior. On the other hand, situational variables include institutional structures, economic realities, social dynamics, and cultural contexts. Together, these variables shape the context of pro-environmental behavior.

Project-based learning (PjBL) has been widely recognized as an effective pedagogical approach in environmental education, particularly within geography instruction at the lower secondary level [17,18]. Its effectiveness can be theoretically explained by linking the core characteristics of PjBL—experiential learning, collaboration, and problem-oriented inquiry—to established behavioral frameworks such as the Value–Belief–Norm (VBN) Theory [8] and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [15]. According to the VBN theory, pro-environmental behavior develops through a causal chain that begins with environmental values, continues through beliefs about environmental consequences and the ascription of personal responsibility, and culminates in the activation of personal moral norms [8,10]. In the context of eighth-grade geography education, project-based activities that address concrete and locally relevant environmental issues—such as waste management, water pollution, or land-use changes—enhance students’ awareness of environmental consequences and foster a sense of personal responsibility. By actively engaging students in investigating and addressing real-world environmental problems, PjBL creates conditions that support the activation of personal norms, thereby strengthening eco-centric values. In this sense, project-based learning operationalizes the norm activation mechanism central to the VBN framework [8]. From the perspective of the Theory of Planned Behavior, PjBL also influences the three primary determinants of behavioral intention: attitudes toward behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control [15]. Experiential and inquiry-based learning activities contribute to the formation of more positive and enduring attitudes toward environmental protection by enabling students to directly observe the consequences of human–environment interactions. Collaborative group work, a defining feature of PjBL, reinforces subjective norms by promoting shared responsibility, peer discussion, and collective decision-making, which are particularly influential during early adolescence. Additionally, practical project tasks—such as field observations, data collection, and the development of local environmental solutions—enhance students’ perceived behavioral control, increasing their confidence in their ability to engage in pro-environmental behavior [19]. Compared to traditional, teacher-centered instruction, which primarily focuses on the transmission of factual knowledge, project-based learning engages students across cognitive, emotional, and social dimensions. This integrated engagement is especially important for students in the eighth grade, as environmental values, attitudes, and norms are still forming during this developmental period [20]. Geography, as a school subject that inherently links natural and social systems, provides a particularly suitable context for such an approach. By situating learning within real and locally meaningful environmental contexts, PjBL facilitates the internalization of eco-centric values and supports the translation of environmental knowledge into responsible attitudes and behaviors [1]. Overall, explicitly mapping project-based learning onto the VBN and TPB theoretical frameworks helps explain why project-based geography instruction is more effective than traditional teaching methods in fostering eco-centric values, pro-environmental attitudes, and environmentally responsible behavior among eighth-grade students. This theoretical integration strengthens the conceptual foundation of project-based environmental education and contributes to the advancement of pedagogical theory in environmental and geography education.

In the 1980s, [13] conducted an extensive analysis of 128 studies, which led to the development of a model aimed at understanding responsible environmental behavior. This model is based on the idea that, beyond personal responsibility, individuals must also possess the necessary knowledge and intention to act in environmentally responsible ways. It also highlights that having the skills to effectively apply this knowledge is equally important for fostering such behaviour. In the following years, a new model of environmental behavior was created taking account of three key variables that may influence human behavior regarding the environment. These variables include environmental sensitivity, personal investment in the environment, and the practical knowledge and skills required to interact with the environment [13].

Bogner [21] asserts that environmental values and attitudes are fundamental to the development of pro-environmental behavior. Values, defined as the fundamental priorities, interests, beliefs, and attitudes held by a society, group, or individual, establish the principles guiding personal conduct [22]. These values play a crucial role in shaping attitudes towards the environment, influencing individuals’ perceptions of the outcomes of their actions, and fostering a willingness to accept responsibility, thus contributing significantly to environmentally acceptable behavior [23].

Bai et al. [24] emphasizes the importance of knowledge as an essential tool for social groups and individuals to acquire experience and understanding of environmental issues. Attitudes, in this context, serve as a pathway for individuals to develop values and demonstrate care for the environment, motivating them to take an active role in environmental improvement and protection. Skills further empower individuals by enabling them to identify and address environmental problems effectively. Other authors concludes that human behavior related to the environment is determined by a combination of attitudes, information, beliefs, and value systems regarding environmental issues [25,26] explored the ways in which children interact with nature, focusing on both the frequency and manner of their contact with the natural environment. Their research demonstrated that frequent exposure to nature is directly or indirectly closely linked to children’s pro-environmental behavior, with this relationship being mediated by the development of positive attitudes toward the environment. Several studies have also investigated the combined effect of direct exposure to nature and environmental education on children’s pro-environmental behavior. For example, researchers compared groups of children who participated in overnight camps either with or without dedicated environmental education programs [26] and children engaged in nature-based educational programs in traditional educational settings [27]. The findings of numerous studies consistently highlight that a strong connection with nature fosters more evident pro-environmental behavior among children [28].

Extensive empirical research has examined the relationship between attitudes and behaviors in the context of environmental protection. Many studies focus on identifying the diverse factors that influence how individuals choose to act in environmentally responsible ways. These investigations have highlighted that personal concern for the environment plays a critical role in motivating behaviors related to waste reduction and that frugal attitude has been shown to significantly contribute to efforts aimed at decreasing gas and electricity consumption [29]. Within the broad spectrum of influences on individual environmental behavior, two primary value orientations have emerged as particularly significant: anthropocentric and eco-centric. The anthropocentric perspective supports environmental protection primarily because of its benefits to human needs, whereas the eco-centric orientation values environmental protection for its inherent worth [30,31,32].

Recent research underscores the importance of adopting alternative teaching and learning strategies across all educational fields, including environmental education, as a necessary response to the limitations of traditional teaching methods [33]. Furthermore, a key aspect of such education is the incorporation of constructivist approaches to teaching [34,35]. In examining the influence of teaching practices on the development of values and attitudes towards the environment and pro-environmental behavior, research highlights the effectiveness of teaching strategies that immerse students in real-life environmental challenges within their own communities [36,37]. Within this context, project-based learning (PBjL) [38,39] emerges as a particularly effective teaching and learning strategy.

Interest in adopting project-based learning lies in the desire to move away from educational approaches based on knowledge transfer to approaches where students take an active role in their education. This shift encourages more meaningful and reflective learning experiences and promotes more frequent interactions among teachers, students, and the wider community [40,41]. Project-based learning is firmly rooted in socio-constructivist theory and principles, which places emphasis on meaningful learning and the active construction of knowledge. Within this framework, students engage with content through social interaction and problem-solving, often addressing challenges in real-life contexts [42,43]. The origins of project-based learning are found in educational philosophies, notably Dewey’s concept of “learning by doing” and Kilpatrick’s project method [44]. These foundational principles have been adapted and refined for contemporary classrooms, so that the learning needs of the 21st-century students are successfully met.

Innovation and proactive engagement are fundamental drivers in the transformation of educational practices. In this regard, Project-Based Learning (PBjL) has emerged as a particularly effective strategy, distinguishing itself by moving beyond the conventional constraints of the classroom environment. It fosters an educational atmosphere that “... leads students beyond the traditional classroom setting into a vivid, experimental” [45]. This approach supports the call for educational renewal by establishing a new framework that places students at the center of their own learning journey. It also promotes cognitive skills and nurtures social and affective development [46]. Given the realities of the global landscape, it is increasingly important to align PBjL with sustainability objectives in order to equip students with the abilities necessary to address real-world problems. Furthermore, this educational approach is in harmony with the Fourth United Nations Sustainable Development Goal, which advocates for inclusive, equitable, and high-quality education. PBjL’s interdisciplinary and research-oriented nature makes it an effective means of supporting these global educational goals.

The application of project-based learning (PBjL) faces a variety of challenges that are multifaceted, encompassing regulatory, organizational, social, and contextual factors. Such challenges diminish the feasibility of PBjL in certain educational environments. One of the major issues is uncertainty surrounding the successful acquisition of knowledge and the development of key competencies through PBjL. This uncertainty is further compounded by a lack of adequate material, technological, and financial resources, which are essential for supporting project-based learning methods [47]. Despite evidence from research indicating that PBjL can enhance problem-solving skills, foster student engagement, and facilitate deeper learning experiences [48,49], the overall impact of this approach remains a subject of debate [50].

Van den Bergh et al. (2006) have identified notable drawbacks associated with project-based learning, particularly the increased workload for teachers and difficulties in evaluating student achievements within PBjL frameworks [51]. Markam et al. (2003) similarly point out that implementing PBjL is demanding for teachers, highlighting the challenge of establishing a stimulating and focused learning environment [52]. Research by [53,54] underscores additional challenges related to cooperative work within project-based learning. These authors note that when collaborative methods are employed, there is a risk of students acquiring fragmented or selective knowledge, rather than generalized concepts and a comprehensive understanding of the environmental issues being studied. Furthermore, these studies highlight the potential for uneven distribution of student participation in project tasks. Some students may take on more responsibilities while others contribute less, leading to imbalances in workload and learning opportunities. Problems may also arise during the execution of project activities at various stages, which can disrupt the overall flow of the project and negatively impact student autonomy [53,54]. In addition to these concerns, effective planning and completion of projects remain persistent obstacles to the successful adoption of project-based learning.

Teachers frequently face significant obstacles in both the design and implementation of Project-Based Learning (PBjL). These challenges are largely attributed to limited opportunities for professional development and a lack of sufficient methodological training [55]. Given these challenges, it is essential to systematically assess and organize the existing knowledge regarding the application of PBjL in various educational settings. Furthermore, a comprehensive understanding of how PBjL fosters the development of key competencies—such as collaboration, critical thinking, and social responsibility—enables its integration with the broader objectives of sustainable education.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

The research employed a convenience sample comprising 255 students in the final (eighth) grade of primary school, all of whom were approximately 14 years old. The study was conducted in six primary schools in the Belgrade area (Serbia). These participants were divided into two groups: the experimental group, which included 128 students (four classes), and the control group, consisting of 127 students (four classes). Careful attention was paid to ensure that the groups were balanced, both in terms of the number of participants and the initial testing results, to maintain comparability. The selection of final-year students was deliberate, based on the assumption that these pupils had acquired the greatest amount of knowledge and experience related to environmental protection through their formal education in geography and biology, as well as through participation in extracurricular activities. The selection of final-year primary school students was also based on the fact that the geography curriculum for this grade is the only one that includes the application of project-based learning in the study of the local environment [56]. It is important to note that the sample was not representative of the entire population of primary school students, and that it was relatively limited in size. This means that the findings from this research should be interpreted as indicative of trends regarding the impact of project-based learning on the development of students’ values, attitudes, and pro-environmental behaviors. However, these results cannot be generalized to all primary school students in Serbia.

3.2. Procedure

Before the experiment commenced, the approval was obtained from the participating schools, ensuring their willingness to be involved in the research. In addition, parental consent forms were distributed by the research team or designated school staff to the families of all potential participants. After a one-week period, the signed parental consent forms were collected. The pretest was administered in classroom settings during regular school hours, using a standardized paper-and-pencil format under the supervision of teachers and/or members of the research team.

An initial testing was then administered to all participants (a total of 280 students). The results of this pre-test was used to form the final sample (a total of 255 students), ensuring that both the experimental (a total of 128 students) and control groups (a total of 127 students) were balanced. Namely, based on the analysis of scores obtained through five-point scales (EAATE and developed pro-environmental behavior scales), students identified as extreme cases were excluded from each class. These were students whose scores deviated by ±10% of the standard deviation from the mean value within the normal distribution of scores. As a result, the final sample was formed in the experimental and control groups. At this stage, the questionnaire items were also reviewed and revised. Initially, the EAATE scale was composed of 31 items. During the preliminary testing phase, the internal consistency of the scale was assessed using the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient. The result of this analysis showed a coefficient of α = 0.57, which is below the generally accepted threshold of 0.7 for satisfactory reliability. A closer examination revealed that nine items had item–total correlation values below 0.3, which suggested that these items contributed negatively to the overall reliability of the scale. Consequently, these items were removed from further analysis in order to enhance the scale’s reliability.

The experimental teaching intervention was implemented over the course of one academic year. The research was designed as a pedagogical experiment employing parallel groups. Students in the experimental group studied environmental content through group work and the application of project-based learning approaches. In contrast, students in the control group covered the same material using traditional teaching approaches, which included a combination of monologic, illustrative, and dialogic lecture methods, along with the use of textbooks. Upon completion of the experimental teaching phase, a final testing was conducted with all participants.

3.3. Research Instruments

The Eco-centric and Anthropocentric Attitudes Towards the Environment (EAATE) scale [7] was implemented to assess students’ values and attitudes concerning environmental issues. To measure pro-environmental behavior, the researchers developed a composite scale by selecting items from two instruments: the Self-reported Proenvironmental Behaviors (PEB) [57] and the General Ecological Behavior (GEB) [58] scales. The questionnaire was carefully adapted to reflect the cultural context of Serbia, and revisions were made to the original PEB and GEB scales based on research findings that supported their modification [57,58]. The final pro-environmental behavior scale in this study included a total of 22 items, comprising 5 items from the PEB and 17 items from the GEB scales. Students’ attitudes were evaluated using a five-point Likert scale, with response options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The frequency of pro-environmental behaviors was measured using a five-point frequency scale, where 1 represented “never” and 5 indicated “very often”.

The Eco-centric and Anthropocentric Attitudes Towards the Environment (EAATE) scale has demonstrated reliability and validity across several studies [7,32,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66]. The final version of the EAATE scale in our study consisted of 22 items, evenly divided between two subcategories: 11 items measuring anthropocentric attitudes and 11 items measuring eco-centric attitudes. The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was α = 0.75, indicating acceptable reliability. The item–total correlation ranged from 0.32 to 0.63, demonstrating satisfactory internal consistency among the items retained for analysis.

The reliability of the pro-environmental behavior scale was assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient. The resulting coefficient was α = 0.82, which is considered to be within the acceptable range. Additionally, the item–total correlation values for the scale ranged from 0.48 to 0.79, further confirming that the items within the scale were satisfactorily reliable. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test indicated that the distribution of scores was normal, with the following frequency distribution: z = 0.045, n = 255, and p = 0.25. Given these findings, it can be concluded that the applied pro-environmental behavior scale was sufficiently discriminative for the purposes of this research.

3.4. Data Analysis

The data collected during both the initial and follow-up assessments were subjected to statistical analysis. Specifically, an independent-samples t-test was employed to determine whether the observed differences were statistically significant, thereby confirming or rejecting the proposed hypotheses. In addition, the analysis included the calculation and examination of the frequencies of results, such as the arithmetic mean, standard deviation, and percentages. The findings were systematically organized and presented using tables and graphs.

Beyond the experimental approach, the research incorporated descriptive methods to gain deeper insights into the data. This involved a series of analytical procedures, including comparison, contrast, evaluation, and interpretation of the results obtained throughout the research. The research concluded with the formulation of evidence-based conclusions. Throughout the research process, systematic monitoring and documentation of students’ activities were carried out. The products generated by participants were assessed to provide a qualitative perspective on the effects of project-based learning.

3.5. Experimental Treatment

The experimental treatment was conducted over the course of one academic year and centred on the topic of “Water Pollution in the Local Environment”. The control group addressed this topic through traditional lecture-based teaching, employing monologue, illustrative, and dialogue methods, as well as using a textbook as the primary instructional resource. In contrast, the experimental group was divided into six smaller groups, and each was assigned a task to complete a distinct project related to the central topic.

During the initial phase of the experimental treatment, a period of five weeks was allotted for the creation of the project drafts. Throughout this process, the teacher played a facilitative role, offering expert guidance and clarifying the essential elements and criteria necessary for defining each project. The project drafts were required to include several specific components: the research title; the subject, objectives, expected outcomes, specific tasks and activities, and the distribution of roles among group members; defined phases of the project; details regarding the sample; the number and locations of measurement points; a list of tools and instruments to be used; the anticipated duration of individual phases and activities; sources of information; and the procedures to be followed for organizing, presenting, and interpreting the research results and collected data. Upon completion of their drafts, each group presented their project outline to the rest of the class through a PowerPoint presentation. Following the drafting and presentation of their project plans, the groups proceeded to independently execute their respective projects.

The first group of students engaged in comprehensive field research as part of their educational project. Their work focused on sections of the Danube and Sava riverbanks that were located near their school. To begin, the group made several visits to these riverbanks with the objective of identifying illegal dumps in the area. They systematically located and counted the number of illegal dumps present along the banks, ensuring that each site was precisely marked on a map that had been prepared beforehand to represent that section of the city. Following the mapping of illegal dumps, the students proceeded to record detailed observations regarding the types of waste found at each dump site, as well as in the river itself. They carefully logged all collected data into tables that had been set up in advance for this purpose.

After collecting and analyzing data on illegal dump sites along the Danube and Sava riverbanks, the group was tasked with formally communicating their findings to the local municipal waste collecting company. They prepared a detailed letter that included the specific locations of the illegal dumps, accompanied by a comprehensive list of the types of waste identified at each site. The letter further explained the processes and rates of natural decomposition for each category of observed waste, both on the riverbanks and within the watercourse itself. In addition, the letter emphasized the significant risks these illegal dumps posed to the river ecosystem and its wildlife, highlighting the damaging effects of leachate generated from the waste. Students also underscored the environmental and community benefits of recycling waste and outlined specific recommendations for the removal of existing dumps as well as strategies to prevent the formation of new ones in the future. The group presented both the letter and an accompanying film documenting their research to their classmates, ensuring that the entire class was informed about the investigation and its outcomes. Subsequently, the letter and film were formally submitted to the municipal waste service responsible for that region of Belgrade. To further raise public awareness, the film and other materials created during the group’s project were showcased at an informational booth near the school in order to educate the local community.

The second group of students conducted field research just like the previous one. The main task was to identify locations where municipal wastewater is discharged into the river and to mark them on a previously prepared map of that part of the city. Then, they drafted a letter to the Ministry of Environmental Protection and the Hydrometeorological Institute. The letter requested information on whether sewage water is treated before being discharged into the river, the methods used for treating municipal wastewater, the sources of municipal water (households, industry, agriculture, leachate from landfills), as well as the presence and concentrations of chemical, biological, and physical pollutants in the wastewater being discharged into the watercourse. The final segment of the activity was carried out in cooperation with biology and chemistry teachers, who provided students with the necessary instruments and chemical reagents, as well as the training needed for field sampling and conducting chemical–biological analyses of the sampled water in the laboratory. In addition to the letter, the results of the second group’s work included maps marking the locations of municipal wastewater discharge into the river and a table with the requested data. Based on the obtained results, the group was given the task to create an informative brochure on river pollution caused by municipal wastewater, which was then distributed to residents at the booth. The content of the brochure aimed to inform the public about the types of pollutants discharged into the river via sewage system, the consequences of waterway pollution on wildlife and human health, and ways individuals can act responsibly in their daily use of water at home.

The third group of students conducted field research on the sections of the Danube and Sava riverbanks in the area where municipal wastewater is discharged. On the imagined area of 5 m2, located 50 m upstream from the discharge point, the students assessed the diversity of plant species (tall-emergent, and floating) using previously prepared photographs as supplementary material. They photographed the area and the aquatic plants on-site, and for each identified species, they determined the coverage. The same procedure was repeated 50 m downstream from the wastewater discharge point. The students recorded the obtained data in tables and based on them, created a river pollution scale with bioindicators. The results of this group’s work included tables with recorded data, photographs of aquatic plants, the river pollution scale, as well as a photo-essay on river eutrophication due to the presence of organic pollutants in municipal wastewater, which was all displayed on a panel and presented at the booth.

The fourth group of students conducted an experiment to determine water pollution by detergents. On the banks of the Danube and the Sava, they collected water in a transparent bottle, shook the sample for 30 s, and then measured with a ruler the height of the foam formed on top and the time it too to disappear with a stopwatch. In accordance with the instructions (if the foam disperses in one second, large bubbles disappear in 35 s, and small ones in an hour, it is considered that the water is not significantly polluted by detergents), they drew conclusions about the degree of pollution. All results were recorded in previously prepared tables, and the students also composed a written conclusion and analysis. The process of sampling and conducting the experiment was filmed, and this video was shown to residents at the booth.

The fifth group of students researched the problem of water pollution and scarcity using the information on the web. They found relevant websites and texts about water pollution, the depletion of sources of drinking water, and the extinction of plant and animal species in aquatic ecosystems as a consequence of new lifestyles and industrialization. They selected the most important information, based on which they wrote an essay. Then they created a joint “historical timeline” that showed the occurrence of these problems over the last twenty years, divided into five-year intervals. For each period, they presented the studied phenomenon or process with a text, photographs, tables, and charts found on the web. The historical timeline was displayed at a common booth.

The sixth group of students created an educational comic with the aim of showing the ways in which individuals can pollute natural water sources in everyday activities, as well as how to use water rationally at home. The comic contained appropriate illustrations and a text, and the students distributed printed copies to residents at a stand.

Having finished their work in groups, students had an intergroup evaluation of the research projects and their products. In this way, the results obtained by all groups were consolidated, the most important ones highlighted, and conclusions were drawn about the causes of existing water pollution problems, as well as measures that the local community should take to address them. The joint activity also involved designing the booth and improvement of the materials that would be displayed there. They developed a relevant audio text for the video presentation; shaped the content of the brochure; and made panels for the photo essay and historical timeline. Besides displays at the booth, students held a public presentation in the school hall with the presence of students from other classes and parents. The results of the project and each group’s products were posted on the school websites.

4. Results

This chapter presents the results of the research of the impact of project-based learning compared to traditional lecturing that uses illustrative and dialogue methods, on the development of eco-centric and anthropocentric attitudes, as well as on the pro-environmental behavior of students.

The results of the descriptive statistics for the initial and final testing of values and attitudes and pro-environmental behavior in the experimental and control groups are shown in Table 1. In the initial testing, the arithmetic mean (M) of anthropocentric attitudes was slightly higher in the control group (M = 31.91; SD = 5.95) compared to the experimental group (M = 31.65; SD = 5.38). In the final testing, a different trend across the groups was observed, as in the experimental group the mean value remained almost unchanged (M = 31.72), but the standard deviation increased (SD = 6.40), indicating greater individual differences among students. In the control group, the mean value increased (M = 32.46), whereas the standard deviation decreased (SD = 5.29), suggesting somewhat more uniform responses among students regarding anthropocentric attitudes.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics Results.

At the initial assessment, it was observed that the mean value of eco-centric attitudes was slightly higher in the experimental group (M = 45.66; SD = 8.23) compared to the control group (M = 44.15; SD = 8.34). At the follow-up assessment, this difference becomes even more evident: the experimental group shows a higher mean value (M = 46.02), but also greater variability (SD = 8.88), whereas in the control group, the mean value decreases (M = 43.53) and the higher standard deviation (SD = 8.58). These findings indicate that during the experiment, there was an increase in eco-centric attitudes in the experimental group, while a decrease was observed in the control group.

Regarding the pro-environmental behavior of students, in the initial assessment, both groups had almost identical mean values for pro-environmental behavior (EG: M = 66.09; CG: M = 66.02), with slightly higher SD in the experimental group. However, in the final testing, a clear increase is observed in the experimental group (M = 69.07; SD = 11.33), while in the control group, the mean value decreased (M = 65.02; SD = 10.93). This result indicates that project-based learning had a strong effect on students’ pro-environmental behavior, unlike traditional teaching, where no progress was observed.

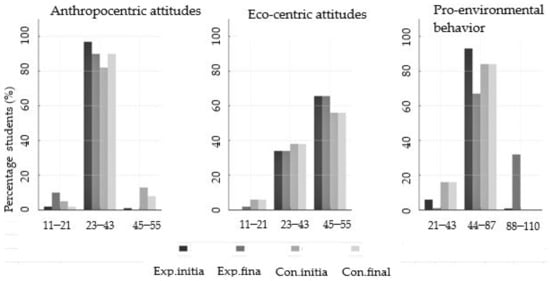

In terms of values and anthropocentric attitudes, the analysis of the results shows that the majority of students in both the experimental (initial 93.7%; final 90%) and control groups (initial 82%; final 90%), both in the initial and final testing, achieved results in the range of 23 to 43 points. In the experimental group, the proportion of students within this range was very high in the initial testing (over 97%), but in the final testing, it slightly decreased to around 90%. On the other hand, in the control group, the percentage of students in the same range increased from approximately 82% in the initial testing to around 90% in the final testing. In the lower score range (11–21 points), a slight increase in the proportion of students in the experimental group (initial 4.6%; final 7.8%) was observed in the final testing compared to the initial testing, which can be ascribed to normal variation. In contrast, in the control group, the percentage of students in this range was slightly higher in the initial testing (12.5%) but decreased in the final testing (7%), which can be explained by typical variation. In the highest range (45–55 points), the percentage of students in both groups was relatively low (experimental group-initial 1.7%, final 2.2%; control group-initial 5.5%, final 3%). In the control group, the findings fall within the range of common variation. These results suggest that project-based learning has, to some extent, contributed to reducing the expression of anthropocentric attitudes by some students in experimental group, while traditional teaching methods in the control group can be explained by typical variation.

Regarding values towards eco-centric attitudes, the analysis of the results of the experimental group showed that the highest number of points on the initial and final testing was achieved in the range of 44 to 55 points. The percentage of students in this interval was approximately the same in both measurements, amounting to about 65.6% (Figure 1). A similar pattern was observed in the range of 23 to 43 points, where the percentage of students was 34%. In the control group, the largest number of students also achieved results in the range of 45 to 55 points, with a share of 56%, while in the interval of 23 to 43 points, there were 38% of students (Figure 1). In the range of 11 to 21 points, in both examined groups, the results of the initial and final testing exhibited typical (normal) variation (less than 5%). Students who achieved results in the range of 23 to 43 points in both groups (experimental group—initial 34.4%, final 34%; control group—initial 37.5%, final 39%) showed approximately the same percentages in the final testing compared to the initial testing. In the range of 45 to 55 points, the percentages of students in both the experimental (initial 65.6%; final 73%) and control groups (initial 57.8%; final 58.5%) were higher in the final testing compared to the initial testing, indicating some shift in results in higher ranges of the scale.

Figure 1.

Pro-environmental values and attitudes and the pro-environmental behavior of students. Source: Authors, based on the results of the research.

The number of students scoring between 44–87 points in the experimental group had a lower percentage on the final test compared to the initial testing, whereas the percentage of students in the control group within the same range was approximately the same on both the initial and final tests. Analyzing the percentages of students in the experimental and control groups on the initial and final testing in the interval of 22–43 points, we observed that the percentages of students in the experimental group on the initial testing were slightly higher (5.5%) compared to the final testing (1%) (Figure 1). The percentages of students in the control group within the 22–43 point range were similar on the initial and final tests, remaining at approximately 5% (Figure 1). By comparing the scores of students in the experimental and control groups on the initial and final testing in the range of 44–87 points, we observed that the percentages of students in the experimental group on the initial testing were higher (93.7%) compared to the final testing (67%) (Figure 1). The percentages of students in the control group within the 44–87 point range were comparable on the initial and final tests and remained at approximately 84% (Figure 1). When we compared students in the experimental and control groups on the initial and final tests within the range of 88–110 points, we observed that the percentages of students in the experimental group on the final test were statistically significantly higher compared to the initial test (Figure 1). The percentage of students in the control group within the 88–110-point range showed no statistically significant difference between the initial and final tests.

In accordance with the first and third hypotheses, it was examined whether the results of the control and experimental groups differed statistically significantly in terms of values and attitudes and pro-environmental behavior before the introduction of the experimental treatment. This was important to demonstrate that the experimental and control groups were comparable in terms of values and attitudes and pro-environmental behavior. The results of the independent-samples t-test (Table 2) from the initial testing indicate that there were no statistically significant differences between the experimental and control groups regarding: anthropocentric attitudes (t = −0.373; p = 0.710), eco-centric attitudes (t = 1.452; p = 0.148), and pro-environmental behavior (t = 0.057; p = 0.955). These findings confirm our initial assumption that students from the experimental and control groups were relatively comparable before the experiment, which was one of the basic prerequisites for further research.

Table 2.

T-test statistics of independent samples.

In accordance with the second and fourth hypotheses, at the end of the eighth grade, following the implementation of the experimental treatment, a control testing was conducted. The results of the t-test for independent samples (Table 2) from the control testing show that there was a statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups in terms of the development of eco-centric values and attitudes (t = 2.28; p = 0.023) and regarding students’ pro-environmental behavior in everyday life (t = 2.90; p = 0.004). Conversely, in terms of anthropocentric attitudes, the difference did not reach statistical significance (t = −1.014; p = 0.312). These findings indicate that the application of project-based learning during the teaching of environmental content had a positive effect on the development of eco-centric orientation and pro-environmental behavior, while its impact on anthropocentric attitudes was limited. Thus, it was demonstrated that students who study environmental protection content through project-based learning can further develop eco-centric values and attitudes and forms of pro-environmental behavior in everyday life than students who study environmental content through lecture-based teaching. In addition to independent-samples t-tests, effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated to assess the magnitude of the observed differences between the experimental and control groups at the final testing stage. The difference in anthropocentric attitudes yielded a very small effect size (d ≈ −0.13). For eco-centric attitudes, the effect size was small to moderate (d ≈ 0.29), indicating a modest practical impact of project-based learning. The largest effect was observed for pro-environmental behavior, with a moderate effect size (d ≈ 0.36), suggesting a meaningful practical advantage for students in the experimental group.

5. Discussion

The aim of this research was to examine the impact of project-based learning compared to traditional methods (lectures, illustrative–demonstrative, and dialogue methods) on the development of eco-centric and anthropocentric attitudes, as well as pro-environmental behavior in students. The initial null hypotheses were formulated to assume the absence of statistically significant differences between the experimental and control groups, both in the initial and follow-up measurements. The results of the initial measurement showed that there were no statistically significant differences between the experimental and control groups in terms of anthropocentric and eco-centric attitudes, as well as in pro-environmental behavior. In the follow-up measurement, the existence of statistically significant differences between the experimental and control groups was not confirmed regarding anthropocentric attitudes, while it was confirmed regarding eco-centric attitudes and pro-environmental behavior. Based on these results, we fully accepted the first and third null hypotheses, and partially accepted the second (the segment related to anthropocentric attitudes) and regarding them, we accepted an alternative hypothesis that the students of the experimental and control groups differ statistically significantly in terms of the development of eco-centric value attitudes and pro-ecological behavior in the final testing.

The results obtained from the initial measurement confirmed that, before the application of the experimental treatment, the experimental and control groups were approximately comparable in terms of the observed parameters. Such homogeneity of the groups ensures the internal validity of the research. According to Thomas (2000) and Bell (2010), the comparability of groups represents a prerequisite for valid conclusions about the effects of instructional interventions [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67]. This finding ensures the validity of introducing the experimental factor (project-based learning), allowing the differences in the final test of environmental values and attitudes and student behavior to be attributed to the effects of the experimental treatment (project-based learning versus traditional lecture-based teaching), rather than to random factors. A similar methodological approach in ensuring controlled conditions is highlighted by Thomas (2000) and Bell (2010) in their works on the evaluation of teaching methods [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67].

Regarding the anthropocentric values and attitudes, the results of descriptive statistics show relative stability of anthropocentric attitudes in the experimental group, with a slight decrease trend in the proportion of students in the higher score intervals, whereas in the control group a slight increase in the mean value was observed and a simultaneous decrease in variability. In this group, there was a slight increase in the percentage of students in the middle and higher ranges of the scale. This finding suggests that project-based learning, although it did not lead to statistically significant differences, encouraged some students to reconsider human dominance over nature, whereas traditional teaching in the other group led to a slight strengthening of the anthropocentric orientation. Namely, a descriptive analysis of the obtained results showed that there are, nevertheless, significant differences in the way students in the experimental and control groups developed their pro-environmental values and attitudes and pro-environmental behavior. In terms of anthropocentric attitudes, it was observed that in the experimental group there was a slight decrease in the number of students who achieved high results in the range of 23 to 43 points and an increase in the number in the lower result interval (11–21 points). This change can be interpreted as an indicator of a weakened anthropocentric orientation in some students, which is in line with the expectation that innovative teaching strategies, such as project-based learning, encourage critical reconsideration of humans’ dominant position in relation to nature [32]. In contrast, in the control group, where traditional teaching was applied, there was a slight strengthening of anthropocentric attitudes, indicating that conventional forms of teaching do not sufficiently encourage the reconsideration of such value orientations. Similar trends have also been described in earlier research, which indicates that active and inquiry-oriented teaching strategies can lead to a reduction in the anthropocentric perspective [68]. However, the t-test did not confirm statistically significant differences between the experimental and control groups, suggesting that project-based learning did not significantly impact the reduction in the anthropocentric orientation. This finding aligns with the results of Kortenkamp and Moore (2001), who emphasize that anthropocentric attitudes are more stable because they have a more deeply rooted basis in cognitive values and are therefore less susceptible to change through short-term pedagogical interventions [61]. In other words, project-based learning more efficiently encourages an eco-centric perspective but does not affect the attitudes that view nature instrumentally to the same extent. Certain shifts within the range of lower scores may, however, indicate the beginning of a reassessment of humans’ dominant position relative to nature, which has also been observed in the previous studies [32,68]. Slight improvements in the experimental group can be interpreted as an indicator of an initial change in students’ cognitive and affective attitudes toward nature. Frantz & Mayer (2014) emphasize that experiential and interactive teaching strategies can contribute to weakening anthropocentric attitudes, but long-term effects require more systematic and continuous educational interventions [69].

Regarding the eco-centric values and attitudes, the results of the descriptive statistics showed that the experimental group experienced a slight increase compared to the initial measurement and a decrease in the mean value was observed in the control group. While there was a slight decline in the proportion of students with higher eco-centric attitude scores in the control group, this percentage increased in the experimental group. Based on the results, it is evident that the majority of students in both groups exhibited a relatively high expression of these attitudes, which is most clearly seen in the range of 45 to 55 points. However, the percentage of students in the experimental group was somewhat higher compared to the control group, indicating that project-based learning had a moderate positive effect on strengthening eco-centric orientation.

When comparing the results of students in the experimental group at the initial and final assessments with regard to anthropocentric value orientations, a slight decrease within the 23–44 point range can be observed, as the proportion of students in this range declined from 93.7% at the initial measurement to 90% at the final one. Similarly, when analyzing ecocentric value orientations within the same 23–44 point range, a slight decrease was also noted—from 34.4% at the initial assessment to 34% at the final assessment. A minor decline was further observed within the 45–55 point range, where the proportion of students decreased from 65.6% at the initial testing to 64% at the final testing. Overall, these results suggest that the decline in both anthropocentric and ecocentric value orientations was negligible (approximately 3–4%). Specifically, within the experimental group (n = 128), the percentage of students with lower scores (23–44 points) in anthropocentric value orientations slightly increased from 6.3% at the initial testing to 10% at the final testing (a 3.7% rise). In contrast, for ecocentric orientations, the percentage of students within the same score range remained almost unchanged—34.4% at the initial assessment and 34% at the final one.

It is particularly important to note the increase in the proportion of students with lower results within the experimental group, which points to a possible heterogeneity in the effects of the teaching approach. This finding indicates that project-based learning, although overall having a favorable impact on eco-centric values, due to the emergence of heterogeneity within the experimental group, may affect individual students differently, which is consistent with research that emphasizes the role of individual characteristics in the formation of ecological attitudes [69]. The observed heterogeneity of results in a smaller number of students within the experimental group manifested as a decline in scores in the lowest category, which can be attributed to individual differences in motivation or cognitive styles among students, as well as the limited time exposure to project activities. This finding corresponds with Milfont & Duckitt (2010), who point to the strong influence of personal values and personality on the adoption of the eco-centric perspective [68]. The results of the t-test, however, confirmed a statistically significant advantage in favor of the experimental group, indicating that project-based learning promoted the strengthening of eco-centric orientation. This is consistent with the previous research suggesting that active and participatory teaching, such as project-based, reinforces the connection between values and nature, and encourages the development of an eco-centric perspective [18,70]. Stevenson (1986) points out that active students’ involvement in solving authentic environmental problems, their collaboration, and active search for solutions allows them to recognize the real interdependence of humans and nature, develop an emotional connection with nature, as well as responsibility toward the environment, which directly influences the formation of eco-centric values and attitudes [70]. According to him, this teaching strategy not only develops knowledge but also strengthens empathy towards nature and ethical responsibility for its preservation. Kopnina and Cocis (2017), in their research, examined eco-centric attitudes after completing the course based on the environmental subjects, with the aim of determining to what extent teaching specific environmental values influences the development of eco-centric orientations [65]. At the same time, the research highlighted the limitations of post-course evaluations. Namely, according to this research, results measured through competencies and quantitative skills do not always reflect the value orientation of the participants, nor can they fully predict their behavior. The development of a deeper understanding of the more challenging aspects of environmental sustainability most often occurs after cognitive content has been internalized and when the affective attitudes of the participants gradually form through continuous learning. This learning is not limited to the educational process alone, but is also supported by various formative experiences in everyday life. Accordingly, Stern (2000) emphasizes that students attending courses in the field of sustainability are not necessarily motivated by eco-centric values; their engagement may also be driven by social interests [10]. This finding confirms the need to strengthen eco-centric values that encourage stronger pro-environmental behavior [66].

The most evident effect of project-based learning in this study was observed in terms of pro-environmental behavior. While both groups showed almost identical results in the initial measurement, the experimental group achieved significantly higher values in the control measurement, whereas the control group experienced a slight decrease. These findings strongly support the theoretical positions of Hungerford and Volk (1990), who emphasize that direct experience in addressing environmental problems increases the likelihood of transferring knowledge into actual behavior [71]. Similar results are reported by Jensen and Schnack (2006), who highlight that participatory forms of learning contribute to the adoption of lasting environmental habits because the acquired knowledge is transformed into practical action [72].

The effect size analysis provides additional insight into the practical significance of the findings. While changes in anthropocentric attitudes were negligible, project-based learning demonstrated a small to moderate practical effect on the development of eco-centric attitudes and a moderate effect on pro-environmental behavior. These results suggest that project-based learning may be particularly effective in promoting behavioral change, even when shifts in value orientations are more gradual.

The results of our research indicated that project-based geography learning has a significant impact on the development of pro-ecological behavior and ecocentric attitudes of students, while its effect on anthropocentric attitudes is more limited. This can be explained by the specificities of cognitive and affective processes that are activated by the application of project-based learning. Through direct research into environmental problems, fieldwork, and solving concrete tasks that require cooperation and critical thinking, students develop empathy for nature and a sense of personal responsibility for its preservation. Such experiences encourage an ecocentric orientation because they connect knowledge with emotional experience and value attitudes towards nature. On the other hand, anthropocentric attitudes, which view nature as a means to meet human needs, are more deeply rooted in social, cultural, and economic contexts and are created over a longer period of time. Other authors have come to similar conclusions, emphasizing that project-based learning, based on the investigation of real-life environmental problems, fosters empathy for nature and develops an ecological identity in students [70,73]. Through fieldwork, joint activities, and the implementation of research in the local environment, students emotionally connect with nature and develop a sense of personal responsibility for its preservation, which is confirmed by the results of research by Palmer and Rickinson [74,75], who emphasize the affective role in the formation of ecocentric values. Such results confirm the view that experiential and contextualized learning, characteristic of project-based learning, has a more effective impact on ecocentric rather than anthropocentric attitudes, because it allows students to experience nature as a value in itself [21,76,77]. On the other hand, anthropocentric attitudes are deeply rooted in cultural and social values and are often formed outside the school context, as confirmed by the findings of Schultz (2001) and Karpudewana (2013) [60,78]. Therefore, short-term pedagogical interventions, such as project-based learning, are unlikely to lead to significant changes in this domain. However, the gradual introduction of project-based activities that connect human needs with the principles of sustainable development can, in accordance with the recommendations of Genc (2015), contribute to the gradual transformation of value orientations and the development of an integrated and environmentally responsible value system in students [79]. In the present study, effect size analysis offers additional insight into the practical relevance of the findings. Whereas changes in anthropocentric attitudes were minimal, project-based learning yielded a small-to-moderate effect on the development of eco-centric attitudes and a moderate effect on pro-environmental behavior. These results indicate that project-based learning may be particularly effective in facilitating behavioral change, even when shifts in underlying value orientations occur more gradually. With respect to pro-environmental behavior, a negligible decrease was observed within the 22–43 point range, declining from 5.5% at the initial assessment to 1% at the final measurement, likely reflecting normal variation rather than a meaningful change. Conversely, the proportion of students scoring within the 44–85 point range increased markedly, from 6.3% to 33%, suggesting that approximately one-third of participants (around 38.3%) exhibited a relatively substantial improvement in this domain. These findings may reflect systemic constraints, including a potential bias toward socially desirable responding—a tendency frequently documented in self-reported measures of environmental attitudes and behaviors [68,80]. These findings indicate that, although the majority of students demonstrated progress, a smaller subset exhibited stagnation or a decline in performance, which may be attributed to individual differences in motivation, cognitive styles, and the level of engagement during project-based activities. Similar observations have been reported by Milfont and Duckitt (2010) and Kortenkamp and Moore (2001), who emphasized that personal characteristics can influence the degree of internalization of environmental values and behaviors [61,68].

Descriptive statistics showed that the experimental group made considerable progress also in the highest range of scores (88–110 points), where the share increased by about 31% in the follow-up measurement. This finding clearly indicates that the application of project-based learning encouraged students not only to develop eco-centric values and attitudes but also to translate them into more evident behavior in everyday life. There were no significant changes in the control group, which further confirms the relevance and effectiveness of the applied pedagogical approach. Similar results were obtained in other research that highlights the strong impact of active and participatory learning on the development of pro-environmental behavior [72]. The results of the t-test, which did not confirm a statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups at the initial measurement, confirmed the statistical significance of the differences between the groups at the follow-up measurement, explicitly indicating that project-based learning has a more evident effect on the formation of pro-ecological behavior compared to traditional teaching. This finding supports the results of Hungerford & Volk (1990), who emphasize that environmental education programs with active student participation increase the likelihood that students will adopt behaviors consistent with environmental values [71]. Similarly, Rickinson (2001), in his meta-analysis, highlights that direct experience in addressing environmental problems enhances both cognitive and behavioral outcomes, as well as the likelihood of transferring knowledge into actual behavior [75]. The advantages of project-based learning observed in this research (development of critical thinking, collaboration, integration of acquired knowledge, and strengthening of environmental responsibility) align with the conclusions of Krajcik & Blumenfeld (2006), who emphasize the importance of active learning in contemporary education [81]. However, limitations such as the complexity of planning and implementation, motivation, and institutional support are also noted in the literature [17]. The results of the research conducted by Cetin Kalburan and Selcuk Burak Hasiloglu (2018) show that eco-centric attitudes positively affect pro-environmental behavior, while anthropocentric attitudes do not have a statistically significant effect on pro-environmental behavior [66]. This result largely corresponds with the findings indicating a correlation between eco-centric attitudes and pro-environmental behavior in the research of Casey and Scott (2006) [3]. Similarly, research conducted by Thompson and Barton (1994) suggests that there is a positive correlation between an eco-centric attitude and pro-environmental behavior [7]. De Groot and Steg (2008) show that environmental values have a greater impact on behavior when eco-centric attitudes dominate [4]. At the national level, research by Jovanović and colleagues (2015) indicates that a positive perception of the seriousness of environmental problems promotes the development of environmental responsibility and eco-centric values and attitudes, which results in the development of pro-environmental behavior [63]. Their later findings (Jovanović et al., 2016) emphasize the importance of strengthening eco-centric, rather than anthropocentric, attitudes during the formal education of young people in Serbia in order to foster pro-environmental behavior, with a particular emphasis on the need for children and adolescents in urban areas to have more opportunities for direct contact with nature [64]. On the other hand, Kortenkamp and Moore (2001) believe that an individual’s orientation toward the environment (eco-centric or anthropocentric) is more conditioned by individual differences in attitudes than by situational factors [61].

The application of project-based geography learning in practice involved students who exchanged ideas through mutual communication and collaboration. This teaching strategy encouraged students’ listening skills, which increased their creativity, too. Students were guided to respect others and to collectively come up with solutions or new ideas. The discussion process was essential for project-based learning. The timeframe and deadline for completing the project motivated students to be disciplined. The role of the teacher consisted of monitoring students’ activities. The teacher guided students on how to conduct a group project and how to present their results. Also, the teacher was able to measure each student’s progress, encourage creativity, and provide feedback on the level of content acquisition. The feedback provided encouragement to students during the learning process. On the other hand, students who were in the control group did not have the task of creating a product, and therefore the teacher was not able to develop their creativity. The final step of project-based learning involved conducting the evaluation. Students were required to express their feelings and experiences regarding the completion of the project. The evaluation was conducted to ensure that students could identify shortcomings in the completion of their group work. At the end of the project-based learning, students assessed their own learning and the overall success of the group. In this way, they learned how to use their time efficiently during lessons and remain focused in order to achieve success.

6. Practical Implications for Teacher Training and Institutional Support

The findings of the present study indicate that project-based learning (PjBL) has considerable potential to foster eco-centric values and pro-environmental behavior among students; however, prior research consistently emphasizes that its successful implementation depends on adequate institutional support and well-developed teacher capacity. The literature suggests that teachers implementing PjBL require a specific set of competencies, including the ability to design authentic, curriculum-aligned projects, facilitate collaborative and inquiry-based learning processes, apply formative assessment strategies, and engage in reflective teaching practices [17,47,67]. In addition to individual teacher competencies, institutional conditions play a critical role in supporting PjBL, particularly through access to instructional resources, flexible curricular structures, and administrative support.