Abstract

The development of sustainable smart cities is closely linked to the implementation of artificial intelligence in urban services, which opens up new possibilities for efficient resource management, improving the quality of life and strengthening the participation of citizens. At the same time, the question arises as to how legal and strategic frameworks can support the use of artificial intelligence in a way that contributes to environmental, social and economic sustainability in line with the objectives of the European Union. The aim of this scientific study is to examine the interdisciplinary use of artificial intelligence, data management and sustainability at the European Union level, including support instruments such as regulatory initiatives and funding programs, and to assess their implementation in relation to smart cities. Methodologically, the research is based on a legal analysis of key European and national documents, supplemented by descriptive statistics and visualizations of indicators of digitalization and urban sustainability. In the scientific study, we use the methods of synthesis, comparison and abstraction. The results suggest that the legislative and support framework of the European Union can be a significant impetus for the transformation of individual smart cities, but requires effective coordination and strategic management at the level of local governments. The research highlights the need for an integrated legal-managerial approach that will enable the full use of the potential of artificial intelligence in supporting sustainable urban development of cities.

1. Introduction

As Dušek states, urbanization and technological transformation of cities create new opportunities for effective management of public services, improving the quality of life and overall sustainability of smart cities [1]. Smart cities represent a city concept that uses digital technologies, data solutions and innovations to strengthen the environmental, social and economic strength of cities. Smart cities are characterized by the ability to effectively handle information, support citizen participation and optimize urban processes, with a direct benefit being a significant reduction in the negative impacts of urbanization. Based on internationally recognized smart cities indices, it can be stated that the main elements of smart cities, which are also evaluated in individual international statistics, are smart governance, smart mobility, smart environment, smart living and smart economy [2].

Smart governance as one of these components, according to Kogabayev and Banerjee, represents a modern way of managing a city, which is based on the digitalization of public administration, open data and the involvement of the population in decision-making processes. Cities that want to fulfill the definition of smart governance should use electronic services, platforms that involve the population in decision-making, data analytics, as well as artificial intelligence to support decision-making processes and strategic planning. Smart governance also emphasizes the protection of personal data, cybersecurity and the ethical use of technology, thereby significantly strengthening citizens’ trust in public institutions [3].

As Funta states, smart mobility includes the implementation of digital, sustainable and interconnected transport solutions that optimize the movement of people and vehicles in the city. This concept is based on reducing traffic congestion in cities, reducing emissions and increasing safety, especially in transport, but increasing transport safety also increases the overall safety of the city [4]. Bernad argues that the basis of this concept is intelligent traffic management systems, functional public transport, multimodal transport platforms and the support of ecological forms of transport, such as bicycles, shared vehicles or electric cars. Smart mobility thus creates an efficiently connected transport system that responds to the current needs of residents and contributes to environmental sustainability [5].

A smart environment, according to Bolin, represents the use of sensors, data and digital tools to protect the environment in cities. It includes air quality monitoring, energy management of buildings, smart waste management and the use of renewable energy sources [6]. It also includes subsidies intended to support green and blue infrastructure that improves biodiversity in cities, rainwater management and significantly increases the aesthetic value of public spaces [7].

Smart living focuses on improving the quality of life of residents through technology, innovation and intelligent solutions. Smart living includes modern health services (e.g., telemedicine), digital education, but also the support of smart housing, which is also based on data analytics and a number of sensors that increase the quality of life [8]. In practice, smart living is manifested in the city trying to improve public spaces but also effectively addresses the needs of various population groups, including seniors or people with disabilities. Smart living therefore contributes to the creation of a healthy, safe and harmonious urban environment.

In particular, in the economic literature, there is an opinion that the smart economy represents the transformation of the urban economy from the so-called “paper” functioning towards digitalization, innovation and a modern economy based on data [9]. It focuses mainly on supporting startups, innovation centres, research and development, digitalization of business and the creation of qualified jobs. For this reason, according to Kollár and Matúšová, data-driven processes, automation, artificial intelligence and the development of a shared or circular economy play an important role [10].

It is also important to note that artificial intelligence (hereinafter referred to as “AI”) is playing an increasingly important role in smart cities in the areas of decision-making support, infrastructure management, transport management, energy and security. AI is expected to contribute to the efficiency of public services and resource management, which can significantly support the sustainability goals in accordance with the 2030 Agenda, in particular goal number 11—“Sustainable cities and communities” [11]. At the same time, however, according to some authors, new risks and questions arise regarding, for example, legal liability, transparency of algorithms, privacy protection or equality of access to digital services [12]. In 2025, artificial intelligence is not at a level that it can manage entire cities without human intervention. However, artificial intelligence is advanced enough that it can analyze huge amounts of data and provide outputs from it. At the same time, it is important to note that artificial intelligence is available to the general public in a free version. However, it is still not a flawless system, and several of the above-mentioned issues and risks need to be resolved [13,14].

In parallel with addressing the issue of the use of artificial intelligence, the European Union is strengthening legislative and financial instruments for sustainability. The European Green Deal (hereinafter referred to as the “Green Deal”) represents a fundamental political strategy aimed at ensuring climate neutrality by 2050 [15]. However, it should be emphasized that this initiative does not have widespread support throughout the European Union. The main problem is the fact that environmental protection is very expensive and these funds have to be paid for by taxpayers of the European Union Member States. Support for smart and climate-neutral cities is implemented, for example, through the Mission on Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities initiative and financial mechanisms such as the Cohesion Funds, Horizon Europe and the Modernisation Fund. Cities play a crucial role in this, as they are responsible for approximately 75% of energy consumption and 70% of global CO2 emissions [16].

The development of smart cities is therefore not only a technological challenge, but also an important tool for achieving the goals of the European climate agreement [17]. The key question, in our opinion, remains to what extent cities are prepared to implement AI innovations in accordance with legal, ethical and environmental requirements.

The development of smart cities represents a key trend of the current era, responding to the growing pressure on the efficiency of urban services, citizen participation and environmental sustainability. Smart cities are defined in the literature as cities that use modern digital technologies and smart data to improve governance, quality of life and resilience to social and environmental challenges [18]. The smart city model has evolved over the last two decades from an infrastructure-oriented concept, based mainly on information and communication technologies, towards an integrated approach that includes social, environmental and managerial dimensions.

Modern research identifies five basic dimensions of smart cities: smart governance, smart mobility, smart environment, smart living and smart economy [19]. These dimensions allow for comparisons of cities based on indicators, the most famous of which are the IESE Cities in Motion Index, which evaluates cities according to nine categories of urban development, or the IMD Smart City Index focused on digital services and technological readiness of cities [20].

Professional literature from the European Commission environment also points out the strengths and weaknesses of the smart cities concept. On the one hand, the benefits in the form of more efficient use of public resources, increased quality of life and expanded opportunities for citizen participation are highlighted. On the other hand, several authors point out the risk of technocratic governance and digital inequality [21,22]. According to them, this can lead to the disadvantage of socially vulnerable groups, excessive monitoring of residents through data and camera systems, as well as risks associated with data leakage. Overall, the authors emphasize the need for a “human-centric model” of smart cities that explicitly respects human rights and ethical standards [23].

Artificial intelligence is becoming an important part of smart solutions within smart cities. AI makes it possible to analyze large volumes of data and, based on the analysis of this data, recommend to the user how to make a decision. In smart cities, AI can be used primarily in the operation of services such as transport, waste management, energy, public safety and digital services [24]. Many scientific works highlight the environmental benefits of AI, for example in the form of optimizing energy consumption or predicting traffic flows, which can directly contribute to reducing CO2 emissions in cities [25].

It is undeniable that AI brings several economic and ecological benefits, both for smart cities and for the inhabitants themselves. However, it is important to remember that AI is still just software, which also brings with it important legal and ethical issues. The most prominent challenges include privacy protection, data security, algorithmic transparency and accountability for decision-making, especially when decision-making processes are automated. Predictive algorithms in the field of public safety, for example, have been criticized for the risk of discrimination based on socio-demographic characteristics. In view of several risks, the approach of “Responsible AI” comes to the fore, based on the principles of legality, ethics and trustworthiness [26].

The European Union is a global leader in this area, having been the first to adopt a comprehensive AI law—the Artificial Intelligence Act (2024), which regulates the use of artificial intelligence on a risk-based basis and establishes specific obligations for high-risk systems, including AI systems used in urban services and critical infrastructure. The regulation in question is complemented by other important legal instruments, such as the GDPR Regulation on the protection of personal data and the NIS2 Directive on the cybersecurity of critical infrastructures. Hamza and Ilyas argue that smart city management is a complex process that requires coordination between the public and private sectors. The authors emphasize that city mayors need to align technological modernization with the demands of residents, while still keeping in mind legal limits [27]. If digital solutions are implemented without a systemic strategy, they remain isolated projects without long-term added value. In their opinion, data interoperability, transparency of decision-making processes, citizen involvement and the necessity of financing are therefore essential factors for the successful digital transformation of cities.

Based on the analysis of the literature, we concluded that there is still room for further research and analysis of the issue of building smart cities, AI and sustainability issues. In particular, scientific opinions linking the legal regulation of artificial intelligence with the practical needs of cities, while also taking into account the ever-growing importance of sustainability, are lacking in professional circles. We find even fewer relevant articles and literature in relation to the Central and Eastern European region. Here, it is particularly noticeable that the development of urban digitalization is uneven and often encounters limited financial and professional capacities. At the same time, empirical analyses of the impacts of artificial intelligence on social and environmental sustainability are absent.

From the above, it follows that it is necessary and, in particular, scientifically justified to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the current regulation of artificial intelligence, its implementation and real contribution to the sustainability of smart cities. For this reason, our scientific study aims to at least partially fill this gap which consists of the mutual synergy of the individual components forming this area, i.e., on the mutual relationships of legislation, technologies and smart city management.

The main objective of our scientific study is to examine the regulation of the use of artificial intelligence, data management and sustainability at the European Union level, including support instruments such as regulatory initiatives and funding programs, as well as to assess their implementation in relation to the development of smart cities. We set this main objective in the expectation that our results will demonstrate the growing importance of European legislation as an impetus for the development of smart city innovation. In this context, however, it is necessary to state that the successful implementation of legislation is conditional on effective coordination, managerial preparedness and strengthening the protection of the fundamental rights of urban residents.

Our scientific study has the potential to clarify for both the professional and lay public how the legal, political and strategic frameworks of the European Union shape the possibilities of cities in implementing artificial intelligence, and how these frameworks influence their transformation towards sustainable urban development.

In order to achieve the main goal, we pay attention to the ways in which the regulatory and political environment of the European Union supports the implementation of artificial intelligence in urban services and what impact it has on the possibilities of developing smart, climate-neutral and sustainable cities.

From a systematic point of view, our scientific study is divided into four logically connected sections. In this introductory Section 1 we briefly place our scientific study in a broad context and emphasize its importance. We define the purpose of our scientific work and its significance, including the specific goals set. We carefully examine the current state of the research field and cite key publications. If necessary, we highlight controversial and different hypotheses. In our opinion, the introduction is understandable even for scientists working outside the topic of our scientific study. Section 2, entitled Materials and Methods, is devoted to the issue of the material used and the methods. In our opinion, we describe the materials and methods used sufficiently and in detail to enable others to replicate and build on the published results. Section 3—Results describes in detail and precisely the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the conclusions that can be drawn from them. Section 4 combines the Discussion with the Conclusion. It contains a fairly broad discussion of the results as well as how they can be interpreted in the perspective of previous studies and the stated goal. We discuss the findings and their implications in the broadest possible context and in the full conclusion of this combined chapter we emphasize the limitations of the work as well as future research directions.

2. Materials and Methods

In examining the connection between artificial intelligence, smart cities and sustainability itself, we have chosen a methodological approach capable of linking technological, legal, social and environmental aspects. Cities in the Member States of the European Union are currently confronted with rapid digitalization, the growing need to work with large amounts of high-quality data, regulations governing the use of artificial intelligence, meeting climate standards, as well as requirements for greater transparency of public administration. The above creates a complex legal environment in which the implementation of intelligent solutions is a condition for the long-term sustainability and efficiency of public services. Our scientific study therefore aims to clarify for readers how the legal, political and strategic frameworks of the European Union shape the possibilities of cities in implementing artificial intelligence, and how these frameworks influence their transformation towards sustainable urban development.

As we have already stated, our intention is to examine how the regulatory and political environment of the European Union supports the implementation of artificial intelligence in urban services and what impact it has on the possibilities of developing smart, climate-neutral and sustainable cities in the European Union and in the Slovak Republic. The intention set in this way allows us to identify not only the legal and political frameworks, but also their real impacts on cities in the transition to providing smarter and more sustainable services. In order to achieve the above-mentioned aim of this scientific study, it was necessary to use several scientific research methods. The most frequently used method is systematic legal analysis. In practice, this method is applied in such a way that the authors analyze what is precisely stated in the legal regulations, the way they are interpreted, what is the aim and purpose of a specific legal norm and what these legal regulations bring into practice. In our scientific study, we mainly work with key European legal regulations such as the following:

- Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 laying down harmonized rules in the field of artificial intelligence and amending Regulations (EC) No 300/2008, (EU) No 167/2013, (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1139 and (EU) 2019/2144 and Directives 2014/90/EU, (EU) 2016/797 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Artificial Intelligence Act): the world’s first comprehensive legal framework for the regulation of artificial intelligence [28].

- Regulation (EU) 2022/868 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2022 on European data governance and amending Regulation (EU) 2018/1724 (Data Governance Act) (DGA): rules on data sharing, data altruism and regulation of data intermediaries [29].

- Regulation (EU) 2023/2854 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 December 2023 on harmonized rules on fair access to and use of data, amending Regulation (EU) 2017/2394 and Directive (EU) 2020/1828 (Data Act) Data Act: obligations on access to and sharing of data [30].

- Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) GDPR: protection of personal data in the use of AI [31].

- Directive (EU) 2022/2555 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 concerning measures for a high common level of cybersecurity across the Union, amending Regulation (EU) No 910/2014 and Directive (EU) 2018/1972 and repealing Directive (EU) 2016/1148 (NIS Directive 2): cybersecurity for critical infrastructure and services [32].

- Directive (EU) 2019/1024 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on open data and reuse of public sector information (revised version): obligation to publish public sector data [33].

In such a demanding analysis, we place particular emphasis on the obligations of cities and local governments arising from the above-mentioned regulations, the impact of regulations on digitalization processes in smart cities, requirements for transparency, documentation, audit and data access, as well as limits and risks when introducing AI in the urban environment.

Similar to the legal analysis, we also apply an analysis of strategic documents, which we examine using qualitative content analysis. The assessment focuses on how cities define their priorities, to what extent their strategies reflect European policies, to what extent the strategies include elements of artificial intelligence and the data economy, and how they integrate sustainability aspects into them.

In our research, we try to connect the legal order, sustainability, the concept of smart cities, as well as artificial intelligence, which requires a combination of methods and their mutual application. We have chosen a triangulation methodological approach, within which we systematically compare legal requirements, strategic objectives and empirical data on the actual state of implementation. We use triangulation as a cross-validation tool, which reduces the risk of methodological bias and allows us to identify behavioral patterns and development trajectories across cities.

This approach allows us to precisely name the gaps between the legal status and reality, conflicts between legal regulation and innovation, as well as obstacles to the introduction of artificial intelligence—especially legal, personnel, financial and technological. Using this procedure, we assume that we will be able to reveal the opportunities that regulatory frameworks create.

The synthesis of findings from these three perspectives creates a clear and analytically consistent picture of how the regulatory environment of the European Union can support sustainable and smart urban environments. Ultimately, we can obtain a basis for the formulation of feasible recommendations for local governments, based on the consistency between normative requirements, strategic planning and, in particular, empirical practice.

Following the description of the research methods used, we consider it necessary to briefly summarize the sources on which we based our scientific study. We work with several sources of law at different levels of legal force, which we purposefully combine in order to connect the normative, theoretical and empirical levels of research. The primary sources are the legislation of the European Union. We base our research on the comprehensive texts of European regulations, directives and other regulatory frameworks, as well as on the decisions of the European Commission, including delegated acts. This normative framework of sources forms the basis of our legal analysis, allowing us to accurately identify specific obligations that apply to cities and local governments.

The second level consists of secondary sources, i.e., professional literature and analytical studies. We examine peer-reviewed articles published by renowned publishers, whose scientific journals and conference proceedings are indexed in the Web of Sciences and Scopus databases. Academic monographs focused on smart cities, sustainability and artificial intelligence have also found application. They are no less important than documents from the European Commission, OECD and European Investment Bank. These sources allow us to map the current state of knowledge, identify key concepts of artificial intelligence governance and link them to the sustainability agenda, while providing theoretical and conceptual anchoring for the interpretation of legal requirements. The tertiary layer includes indexes, databases and statistics that complement the legal and theoretical framework with empirical knowledge. We mainly use European Union data portals, urban open-data platforms and international research databases, from which we draw quantitative indicators and comparable metrics on the state and performance of cities. These data show us the reality in individual cities and countries and serve to verify and calibrate the conclusions resulting from the legal and literary analysis. By combining primary, secondary and tertiary sources, we build a comprehensive theoretical foundation that strengthens the validity of our findings and allows us to formulate practically feasible recommendations for urban policy and the management of digital transformation.

At the same time, we declare that this study does not work with personal data or experimental data. When analyzing urban data, we consistently apply the principles of anonymization, ethical use of data, transparency of methodology and independence of conclusions. All information used comes from open and legally available sources; we remove possible identifiers before processing; and we form our interpretations and conclusions autonomously, without external pressure or conflict of interest. With this approach, we ensure compliance with relevant ethical standards and strengthen the integrity and reproducibility of our research.

3. Results

As part of our research, we aim to provide a comprehensive picture of the regulatory environment in which the transformation of mainly Slovak cities into smart, digital and sustainable centres is taking place. By combining systematic legal analysis, content analysis of strategic documents and evaluation of secondary data, we identify the links between European Union rules, national implementation and the real capacities of cities to integrate artificial intelligence into public services. Preliminary findings already indicate that although the European Union is creating a relatively robust framework for supporting digital and climate-neutral cities, persistent differences in implementation practice, technological readiness and data infrastructure continue to represent a significant barrier.

From the point of view of the legal framework, we identify four groups of legislative instruments that most significantly affect the construction of smart cities: artificial intelligence regulation, data economy regulation, cybersecurity regulation and regulations relating to the protection of personal data. Their mutual application sets the boundaries of the responsible use of AI, data accessibility and sharing, infrastructure resilience and protection of citizens’ rights, thereby determining the pace and direction of the digital transformation of local governments.

3.1. Regulation of Artificial Intelligence—Legal Status

Just out of caution, we would like to point out at the beginning of this subsection that the state of legal regulation of artificial intelligence is in its very early stages and therefore national legal orders do not yet have comprehensive legal provisions relating to artificial intelligence. The basic and essentially the only regulation in the EU regulating the rules of artificial intelligence is Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 laying down harmonized rules in the field of artificial intelligence (“AI Act”). The Regulation is directly enforceable in all Member States of the European Union.

3.1.1. Legal Status and Subject Matter

The AI Act establishes a uniform, risk-based legal framework for the development, placing on the market, putting into operation and use of artificial intelligence systems in the EU, while ensuring the protection of the health, safety and fundamental rights of citizens of the EU Member States. In general, the Regulation guarantees the free movement of AI-based goods and services within the internal market; however, Member States cannot impose additional restrictions outside the scope of the Regulation unless the Regulation explicitly allows it. As stated by Tronnier et al., the scope of this Regulation is defined in relation to “providers”, “users”, “importers” and “distributors” of AI systems, as well as to AI systems that are security components of products regulated by sectoral legislation [34]. The Regulation does not apply in any way to activities outside European Union law, while its scope is limited to the placing on the market or use of systems within the EU; it determines the obligations of actors in the AI supply chain.

3.1.2. Prohibited Practices in the Use of AI

The Regulation clearly states that it is not permissible to use AI for covert, subliminal manipulation of human behavior if such intervention leads or may lead to physical or psychological harm. It also prohibits exploiting the vulnerability of specific groups (such as children or people with disabilities) in order to significantly influence their actions and thereby cause them harm. Social discrimination that causes disproportionate disadvantage to individuals without rational reasons is also unacceptable. The Regulation further prohibits untargeted, mass acquisition of biometric data—typically the systematic downloading of facial images [35]. The use of remote biometric identification of persons in publicly accessible places is fundamentally limited and permitted only in exceptional, precisely defined cases, while adhering to strict safeguards set out directly in the Regulation.

3.1.3. Risk Classification and High-Risk AI Systems

The AI Act works with an approach based on risk classification: unacceptable risk, high risk, limited risk (transparency obligations) and minimal risk. The AI Act clearly defines unacceptable practices/prohibited practices. It prohibits social scoring by public authorities, non-targeted collection of facial images from the internet or camera systems for the purpose of creating databases, and the use of emotion recognition in the workplace and schools [36]. Remote biometric identification of persons in real time in publicly accessible places is only allowed in very narrowly defined situations for law enforcement authorities, based on prior authorization and strictly adhering to the principles of necessity and proportionality.

High-risk systems are considered to be in particular solutions used for the management and operation of critical infrastructure (for example, in transport or energy), for ensuring access to essential public and private services, for biometric identification and categorization of persons, in the field of law enforcement, justice and democratic processes. A strict set of requirements applies to these systems: risk management, data management including the quality and representativeness of training, validation and test sets, technical documentation, record keeping and logging, transparency and clear instructions for users, adequate human supervision and parameters of accuracy, robustness and cybersecurity.

The Regulation also introduces transparency obligations. If a person interacts with an AI system and this fact is not apparent, they must be clearly informed. Synthetic and modified content (including deepfakes) should be appropriately labelled. When using emotion recognition or biometric categorization, specific information obligations apply, unless such use is prohibited by another provision [37].

Sarkar et al. [38] point out that they define high-risk systems in two basic groups: firstly, as security components of products or stand-alone products that are already subject to conformity assessment under specific sectoral regulations. Secondly, these are stand-alone systems belonging to specific areas listed in the annex to the AI Act. These include biometric identification, critical infrastructure management, education, employment and work process management, access to essential services, law enforcement, migration and asylum, the judiciary or democratic processes.

For high-risk systems, the Regulation requires providers to have in place a comprehensive risk management system, dataset management with an emphasis on their quality, relevance and representativeness (for training, validation and testing purposes), technical documentation and records, including logging. At the same time, the Regulation requires adequate transparency towards users about the features, risks and limitations of the system, human supervision appropriate for the intended purpose and compliance with requirements for accuracy, robustness and cybersecurity [39]. At the same time, there is an obligation to subject the system to conformity assessment, affix the CE marking, register selected high-risk systems in the EU central database and carry out post-market monitoring, including reporting of serious incidents. Users of high-risk systems must use the system in accordance with the provider’s instructions, ensure adequate human supervision and comply with the obligations under the Regulation.

For systems with limited risk, the Regulation introduces transparency requirements. If the system interacts with natural persons, it must be clearly stated that it is interacting with AI. Specific information obligations apply to emotion recognition systems, biometric categorization, and content generation or manipulation systems—for example, the labelling of artificially created or modified content (so-called deepfakes)—with exceptions and safeguards directly defined in the text of the Regulation.

The Regulation also pays particular attention to general-purpose models (GPAI). Providers of these models must ensure adequate documentation, inform downstream providers and take measures to manage risks. In the case of GPAI models with systemic risk, additional obligations apply, including risk assessment and mitigation or reporting of serious incidents; the technical requirements may be based on harmonized standards or common specifications. In our view, this legal framework is also intended to ensure that AI solutions are developed and deployed transparently, safely and in compliance with fundamental rights, while at the same time allowing for innovation within clearly defined rules.

The AI Act also clearly sets out the institutional control infrastructure and divides competences between the European and national levels. At the European Union level, coordination mechanisms and central databases operate, which support the uniform interpretation and application of the rules; in the EU Member States, supervision and market controls are carried out by the competent national authorities. They jointly ensure market supervision of AI systems, coordinate implementation, issue methodological guidelines and ensure uniform practice across the EU. Bignami et al. further point out that the enforcement of the rules resulting from the Regulation is enforced by a sanctioning regime that takes into account the nature and seriousness of the infringement and the level of the sanction may depend on the worldwide turnover of the entity concerned [40]. The Regulation also regulates the remedies and precise powers of the supervisory authorities so that they can intervene effectively and restore compliance with the requirements.

3.2. Regulation of Artificial Intelligence—Impact on Sustainable Smart Cities

As Sioli et al. state, the AI Act introduces uniform, risk-based rules for the development, marketing and use of AI in the EU [41]. For smart city urban services, this means three fundamental changes. The first change is the obligations and restrictions according to the risk classification, in particular for high-risk AI in critical infrastructure and access to public services. The second change consists of strict limits for biometric use of AI and transparency obligations for human–AI interaction. The third, final change is related to new compliance processes (conformity assessment, CE marking, etc.) and supervision.

Slovak local governments must prepare for AI inventory, assessment for high-risk deployments, adjustment of public procurement and strengthening of governance (competences, training, policies) in transitional periods. Links with GDPR, NIS2, Data Act or Open Data bring concurrent obligations in the areas of data protection, security, data sharing and interoperability.

As part of our research, we also pay attention to the question of how the risk-oriented framework of the AI Act Regulation reshapes the conditions for the deployment of artificial intelligence in smart cities and what obligations arise for smart cities. The AI Act is based on a risk classification, considering as high-risk in particular systems used for the management and operation of critical infrastructure, provision of services, biometric identification, law enforcement, justice or support of democratic processes. As we have already mentioned above, strict technical and organizational requirements are set for these systems, obligations of deployers, a special obligation to assess the impact on fundamental rights and transparency requirements for selected types of interactions with natural persons.

In the area of mobility and parking, there are urban AI solutions that directly control traffic flows. Examples are adaptive traffic lights, intersection management or predictive planning of urban public transport. Typically, these solutions are classified as high-risk, as they fall under the management of critical infrastructure. The provider of such a system must have risk management in place, data management (including the quality of training, validation and test sets), technical documentation and logging, transparency and human oversight, as well as requirements for accuracy, robustness and cybersecurity [42]. Before the final solution is introduced into smart cities, the system must pass the control process by assessing conformity, obtaining CE marking. In addition, where required by the Regulation, it must be registered in the relevant EU database. The deployer (city) is obliged to use the system according to the instructions, ensure competent human supervision, monitor outputs, keep logs, report serious incidents and cooperate with supervisory authorities. Since transport systems commonly work with camera and sensor inputs, the GDPR applies in parallel. The reason is that the processing of personal data requires a legal basis, a data protection impact assessment, and compliance with the principles of necessity, proportionality and minimization, especially for video recordings.

In public safety and urban surveillance, the AI Act clearly limits biometric identification and the work with such data. Remote biometric identification of persons in real time in publicly accessible places is generally prohibited with very limited exceptions intended exclusively for law enforcement agencies. And even these exceptions are issued on the basis of prior authorization and in compliance with the principles of necessity and proportionality. According to Yazici, non-addressed collection of facial images from the internet or camera systems for the purpose of building databases is also prohibited [43]. The use of emotion recognition in the workplace and schools is also prohibited. Other forms of biometric identification and categorization that are not explicitly prohibited are generally classified as high-risk and subject to the full set of requirements of the AI Act. Any solution using camera systems or object/person recognition must have a clear legal basis, go through the appropriate processes, respect the rights of the data subjects (including proper marking of monitored areas) and apply the principles of necessity and proportionality very strictly.

In the energy sector, AI solutions are used to optimize distribution, demand or public lighting. These can be classified as high-risk if they directly control the operation of critical infrastructure. Here, too, the same rules as mentioned above apply. In addition, energy providers must comply with the NIS2 requirements regarding cybersecurity as well as relevant sector regulations.

In waste management in smart cities, AI applications are used for predictive waste exports, container-filling sensors or route optimization. These are generally outside the high-risk regime. Nevertheless, they require adequate transparency where AI interacts with the population, an emphasis on work safety in dispatching, the protection of personal data arising from sensors and cybersecurity in the case of entities falling under the NIS2 Directive.

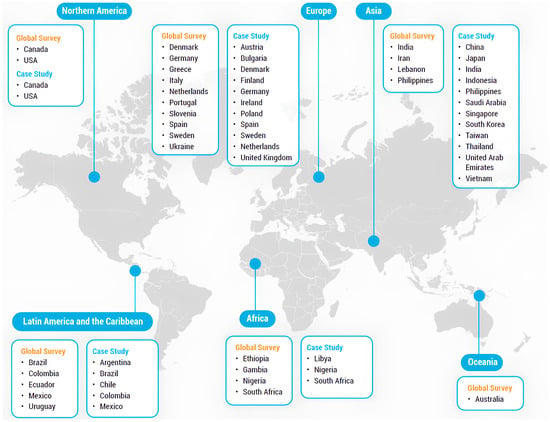

To support our claims, we also present the results of a survey conducted by the United Nations. The survey concerned the Global Assessment of Responsible Artificial Intelligence in Smart Cities (Figure 1). The questionnaire survey was distributed through various networks and communication channels, reaching mayors, experts, researchers and other stakeholders involved in urban planning. In total, the United Nations received approximately 118 responses from 122 municipalities from Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America and North America. In some cases, multiple cities from the same country provided responses.

Figure 1.

Source: United Nations—Global Assessment of Responsible AI in Smart Cities. 2024 [44].

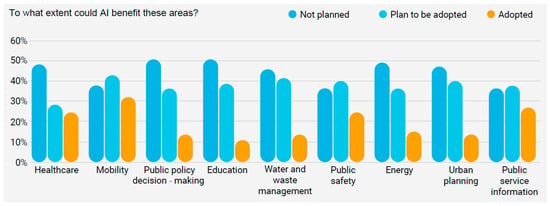

According to this survey, the possibilities of AI are very broad, while at the same time they are very beneficial in transforming a city into a smart city. The main example in the survey is the transformation of urban traffic management thanks to AI. With the advent of AI, completely new possibilities for intelligent traffic management in smart cities are opening up, the significant added value of which is the reduction in traffic jams, the reduction in emissions and, last but not least, the safer operation of cars in cities. The above is also confirmed by the conclusions of the survey, which we present in the graph below. The question was—to what extent could AI benefit these areas? The answers varied, but what can be seen from Chart 1 is that AI has been implemented to the greatest extent in the areas of transport and public services. Other areas are somewhat lagging behind, but we would like to emphasize again that practically all of the areas listed below, i.e., healthcare, transport, decision-making processes in local government, education, water and waste management, public safety, energy, urban planning, but also the provision of public services, are, according to the survey, the subject of interest for smart cities, with AI planned to be implemented in most of these areas, which will significantly increase the level of this area and thus the benefit of AI will become significant [45].

Respondents, who were predominantly mayors, local government representatives and city managers, said that the most significant benefits were seen in the areas of mobility (32%), provision of information on public services (28%), public safety (24%) and healthcare (24%). Cities that are still planning to implement AI expect the greatest benefits in particular in the mobility sector (42%), water and waste management (41%), public safety (40%) and urban planning (40%), indicating a growing perception of the potential of AI even in traditional areas of city governance (Figure 2). The survey also revealed that cities without existing plans to implement AI also see significant potential for AI in the areas of public policy-making (51%) and education (51%). Overall, respondents consider the main benefits of implementing AI to be savings through process automation (58%), increased efficiency of public services (49%), and support for better decision-making (47%), which is in line with the findings of the professional literature on the direction of smart city development. Based on the questionnaire survey, it is possible to assess the real effectiveness of deployed AI, especially in the mobility, public safety and public service sectors, where the benefits have been repeatedly confirmed in practice. At the same time, the results allow us to identify the extent of financial gaps, which are particularly evident in cities with limited budgetary capacities, where the high costs of implementing, operating and providing professional support for AI systems remain one of the main barriers to the wider spread of these solutions.

Figure 2.

Source: United Nations—Global Assessment of Responsible AI in Smart Cities. 2024 [44].

In general, when using e-government, it is important to distinguish between solutions that significantly affect access to public services, e.g., social benefits, housing, school admissions, etc. Such systems are high-risk and must meet all the conditions as we have already stated. At the same time, transparency obligations apply, consisting of the obligation to inform the population that they are communicating with AI and to mark synthetic or modified content, including deepfakes. The GDPR is also mandatory for the processing of personal data in this case [46].

Special consideration to be taken into account is biometric data acquisition in public spaces. Remote biometric identification in real time is inadmissible for ordinary self-government purposes; exceptions are reserved for law enforcement agencies and only in strictly defined situations.

It is also important to take into account the impact of the AI Act on public procurement in smart cities. The reason for this procedure is the fact that cities, as part of local government, are part of the public administration applying the legal regulation on public procurement. Public procurement and contractual practice must reflect the risk-oriented framework of the AI Act from the outset and must not deviate from the legal framework of this Act. In the technical specifications, it is necessary to explicitly require demonstrable compliance with the regulation according to the relevant category (especially for high-risk systems), with a reference to harmonized standards after their publication or with equivalent evidence. Smart cities should require complete technical documentation in the scope according to Annex IV of the AI Act, a description of the risk management system, data management and human oversight mechanisms. Evaluation criteria within the framework of public procurement should take into account auditability, data quality, robustness, cybersecurity (in accordance with NIS2), energy efficiency and sustainability of AI operations. For high-risk systems, it is essential to require CE marking, an EU declaration of conformity and—if required by the regime—registration in the relevant database before delivery and putting into practice; instructions and operator training must be included in the delivery.

The managerial and governance implications for local governments primarily require strengthening organizational capacities. In general, the establishment of an AI Officer position and the creation of cross-functional teams across IT departments, legal departments, data protection departments and cybersecurity departments are proven [47]. At the same time, an inventory of all AI systems is necessary, their classification according to the AI Act, as well as mapping of data flows and the supply chain. The internal city AI policy must regulate the principles of use, security, data quality and public engagement; establish methodologies and clear procedures for incidents and complaints. Systematic training consisting of improving AI literacy, ethical behavior, data protection, cybersecurity or AI procurement is also a prerequisite. In the case of small municipalities, so-called “compliance by design” solutions with pre-prepared documentation, shared regional platforms and cloud/edge services are preferred. Large cities usually have sufficient financial coverage and should therefore build their own governance structures [48].

As stated by Palmero et al., it is also impossible to ignore the fact that financing and support tools represent an important accelerator of smart cities [49]. At the European Union level, the Digital Europe, Horizon Europe and CEF Digital programs as well as cohesion funds can be used for the digital transformation of cities and municipalities and the modernization of infrastructure. At the national level, schemes coordinated by the Ministry of Investments, Regional Development and Informatization of the Slovak Republic (hereinafter also “MIRRI SR”) are being prepared, which will supplement the methodological materials for the AI Act for the public sector. In relation to the implementation of the AI Act in the conditions of the Slovak Republic, it will be necessary to build institutions that will control and ensure compliance with legal regulations. The Slovak Republic will gradually designate the relevant authorities for market supervision, sanctions and coordination; MIRRI SR already operates information portals and therefore has experience with such implementation, and will publish relevant updates in relation to the AI Act. In the area of personal data protection, the Personal Data Protection Office of the Slovak Republic applies guidelines regulating the use of recordings, videos and biometrics; for large-scale camera systems and biometric scenarios, a strict assessment of legality and proportionality is usually necessary.

The above views are also supported by several statistical data, while it is important to emphasize that financial support within the European Union is not intended only expressly for the development of artificial intelligence in smart cities. Member States can draw on these funds, but these funds are tied to individual cities also achieving sustainability goals and investing in research, development and innovation [50]. However, nothing prevents a city from applying for a specific call, using these funds to introduce, for example, intelligent transport in the city, which will be controlled via AI. Such use of funds will, on the one hand, support the city in building and implementing AI systems into its infrastructure and at the same time help in achieving sustainability goals. For example, thanks to AI-controlled transport, emissions in cities will be reduced, thereby pursuing sustainability goals but at the same time supporting the development of AI in smart cities.

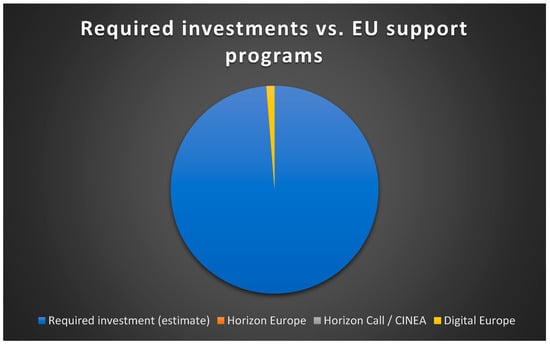

There are many such programs in the European Union alone, but even though the total amount allocated for the development of investments in smart cities is close to nine billion EUR, it is not enough. The estimated investments for approximately one hundred smart cities are close to 650 billion EUR. On the one hand, the European Union supports this plan, but on the other hand, it has not yet allocated this amount in full [51]. As shown in Figure 3 presented below, the most important support programs for smart cities are Horizon Europe with the support of 360 million EUR, Horizon/CINEA with the support of 41 million EUR and Digital Europe with the support of approximately 8.1 billion EUR [52,53]. However, it is clear from Figure 3 that support within the EU is not sufficient and if smart cities want to implement AI technologies with a view to sustainability to the full extent (650 billion EUR), external sources of funding will also need to be used.

Figure 3.

Source: Own processing based on statistical data prepared at the EU level.

However, it is also important to point out the shortcomings in the process of applying for funds from the European Union. The main challenges include the complexity and administrative complexity of the applications themselves, high demands on documentation and control, as well as the need for pre-financing of projects by municipalities, which can be problematic for smaller cities or municipalities with limited budgets. The process of approving and drawing funds is often time-consuming and requires specialized capacities for project preparation and management, which places an extremely heavy burden on municipalities with limited personnel [54].

In addition to direct EU fund programs, cities and municipalities can also use complementary financing models, such as public-private partnerships (hereinafter referred to as “PPP”). There are successfully implemented PPP projects in the Slovak Republic, especially in the field of infrastructure and public services. However, their use is often limited by the high costs and complexity of projects, which require thorough preparation and long-term financial commitments. For this reason, PPP projects are not always the preferred financing option in practice, although they represent a flexible and potentially effective way of implementing more demanding investments.

A differentiated approach to project support—taking into account the size and capacities of local governments—is therefore key. Smaller cities and municipalities may prefer to implement projects gradually with a combination of EU funds and partial co-financing from the state or local budget, while larger cities are able to implement more ambitious projects, including PPP models, using broader financing options and internal capacities to manage complex investment processes.

However, the above-mentioned programs are funding programs implemented at the European Union level, to which, in accordance with the principle of non-discrimination, all local governments within the EU can apply. Within Slovakia, several projects have been implemented in specific cities, financed both from local government funds and from European Union funds, with the aim of these projects being to support sustainable urban development using AI.

As one example, we present the SAM SUD Project—Smart Asset Management for Sustainable Urban Development, which was implemented in the city of Košice, with the total cost of the project amounting to EUR 6,088,617.60 and the city financed EUR 955,513.20 from its own funds. Košice, like many other Slovak cities, is currently facing the problem of empty or underused buildings, which represent untapped potential for community development and environmental protection. The SAM-SUD project responds to this challenge, aiming to transform unused buildings into functional, energy-efficient and socially beneficial spaces. The basis of the project is the use of modern digital tools, including solutions based on artificial intelligence. These tools enable more efficient management of city assets, better planning of building renovation and optimization of their future use. Digital systems are complemented by intelligent IoT sensors that will monitor the operation of buildings and their energy consumption. The project places great emphasis on sustainability and climate resilience. The renovation includes ecological technologies that contribute to reducing energy consumption and the carbon footprint of buildings. These solutions will be piloted during the reconstruction of the building at Hlavná 57, Košice, which will become a prime example of smart and sustainable transformation of urban space. An integral part of the SAM-SUD project is the active involvement of the local community. New multifunctional spaces will be designed to respond to the real needs of residents and support social inclusion, community activities and local development. The SAM-SUD project represents a comprehensive solution in the field of digitalization, climate adaptation and inclusive urban development in the context of AI. The expected outputs and impacts of the project include reducing operating costs and energy consumption in municipal buildings, thereby contributing to more efficient management of public finances. The project will enable better planning of repairs and investments based on data and real needs, which will lead to the long-term sustainability of municipal assets. At the same time, it will contribute to the creation of new jobs and to the strengthening of the city’s professional capacities in the field of digital governance and sustainable development. The result will also be an increase in the comfort, functionality and overall usability of public spaces for residents. Sustainable management of city assets through modern digital tools, AI and data-driven decisions will become the basis for effective and inclusive urban development [55].

Another example is the city of Banská Bystrica. For the purposes of this analysis, we deliberately choose cities other than the capital of the Slovak Republic—Bratislava—because we want to demonstrate that even at the level of smaller cities it is possible to implement AI with the aim of improving overall sustainability. In the city of Banská Bystrica, an IoT smart solution project was implemented in the operation of the City of Banská Bystrica. The project was largely financed by the European Union, which covered approximately 85% of the total costs, with the rest provided by the city from its own resources. Thanks to this support, it was possible to implement modern digital and ecological solutions aimed at more efficient management of city assets. The output of the project is mainly a reduction in the energy intensity and operating costs of city buildings, as well as better planning of their renovation and use. The project also contributed to strengthening the city’s professional capacities and the use of data in decision-making [56]. The result is a more sustainable, more functional and more beneficial urban space for residents.

Likewise, programs to support AI in sustainable smart cities are also implemented directly by the Ministry of Investments, Regional Development and Informatization of the Slovak Republic. This specifically increased the funds within the Modern Technologies call from the Operational Program Integrated Infrastructure of Finance for the so-called smart city solutions in cities. The original allocation of 7.5 million EUR has increased threefold to almost 22.5 million EUR. A total of 35 cities will be able to use the funds. Large cities such as Prešov, Žilina, Trnava, Banská Bystrica or Košice have decided to introduce the latest technologies into the everyday lives of citizens, as well as smaller ones such as Snina, Kežmarok, Bojnice, Zlaté Moravce, Vráble, Holíč and Nesvady.

The above-mentioned empirical evidence from specific Slovak cities shows that AI is also being used more at the local level with the aim of ensuring sustainability in smart cities. At the same time, it connects the above-mentioned legal frameworks with specific management practices within cities in Slovakia [57].

However, it is important to note that when assessing cities of different sizes in the Slovak Republic, it is necessary to take into account significant differences between small, medium-sized cities and the capital, especially in the area of fiscal capacities, technological reserves and availability of talent. However, these inequalities are largely compensated by financial resources from European funds, which allow smaller cities to implement projects and investments that would otherwise be beyond their local capabilities. Despite the fact that funds from European funds significantly help to reduce the differences between large cities and smaller municipalities, it is still necessary to adapt the strategy to their size from the perspective of the management of cities and municipalities. Urban management strategies and recommendations should be tailored to these specificities, taking into account the size of cities and municipalities: smaller cities may require more intensive support from external sources, for example through European funds, and a gradual implementation of technological or innovation measures, while larger cities can implement more ambitious projects with a greater degree of autonomy, but with less financial support from the EU. Such a differentiated approach ensures that the proposed measures are effective and realistically feasible in the context of the specific size and capacity of the city.

3.3. Regulation of Personal Data Protection and Cybersecurity—Legal Status

As part of our scientific study, we also point out that not only the AI Act affects sustainable smart cities, but also the GDPR Regulation and the NIS2 Directive. In relation to these two normative legal acts, it is important to note that they are older legal regulations compared to the AI Act. For this reason, in the introduction, we only briefly pay attention to the regulated area and focus more on the analysis of their impact on sustainable smart cities than on a theoretical description of the legal status.

The GDPR regulates the processing of personal data in the EU and applies to all entities that process data automatically or in structured registers if they are established in the EU. Campanile et al. emphasize that the Regulation defines the basic principles of processing (lawfulness, fairness and transparency; purpose limitation; minimization; accuracy; storage limitation; integrity and confidentiality; accountability) and the legal basis for processing personal data (e.g., legal obligation, performance of tasks in the public interest, legitimate interest, contract, consent, etc.) [58]. The Regulation specifically protects “sensitive” categories of data (e.g., health, biometrics) and their use is only possible in exceptional cases with strict safeguards on the part of the personal data processor. It grants individuals extensive rights (right to information, access, rectification, erasure, restriction, portability, right to object) and the right not to be subject to a purely automated decision with legal or similarly significant effects, except for well-defined exceptions requiring mandatory human intervention. Controllers and processors must comply with obligations such as “privacy by design/by default”, security of processing, record keeping, conclusion of processing contracts, notification of data breaches and designation of a data controller in the public sector. The GDPR also includes international rules on data portability (adequacy, appropriate safeguards, narrow derogations) and supervisory mechanisms (single point of contact) including sanctions. Activities outside European Union law are excluded from the scope of application [59].

The NIS2 Directive sets a common level of cybersecurity in the EU and imposes obligations on entities in selected sectors (e.g., energy, transport, digital infrastructure, public administration, healthcare and others). Entities must implement a set of risk management measures: security policies and organization, risk analysis and assessment, incident prevention and management, continuity and recovery, supply chain security, secure development and maintenance of information and communication technologies, risk management, training, access control, encryption [60]. All of the above measures must also be associated with regular evaluation of the effectiveness of the measures. A key obligation is the obligation to report significant incidents within set deadlines (early warning, follow-up notification, final report) and close cooperation with national authorities. Supervision varies depending on the entity to be supervised, with the content of supervision itself being inspections, corrective orders, sanctions and an emphasis on senior management responsibility for cybersecurity. NIS2 intersects with the requirements of the AI Act (in particular, cybersecurity of high-risk AI) and with the GDPR obligations regarding the security of processing. In practice, cities and municipal enterprises therefore integrate these legal frameworks into procurement, contracts and operational operations. In the Slovak Republic, NIS2 is transposed by an amendment to the Cybersecurity Act with effect from 1 January 2025; the central authority is the National Security Office of the Slovak Republic, supplemented at lower levels by a computer incident response unit called the CSIRT (Computer Security Incident Response Team) and sectoral authorities.

3.4. Regulation of Personal Data Protection and Cybersecurity—Impact on Sustainable Smart Cities

In addition to regulating a range of rights and obligations in the area of personal data protection and cybersecurity, the GDPR and the NIS 2 Directive fundamentally affect the entire life cycle of urban AI solutions—from design and procurement through deployment to subsequent oversight and accountability. As we have already mentioned, the GDPR determines under what conditions cities can process personal data in AI systems, emphasizes lawfulness, fairness and transparency, minimization, purpose limitation, accuracy, integrity and confidentiality of data, as well as the liability of controllers. The NIS 2 Directive complements this framework with a comprehensive set of cyber measures for “essential” and “important” entities in critical sectors. These include energy, transport, digital infrastructure and public administration, including risk management, supply chain management, business continuity, incident management and mandatory reporting.

These two EU legal frameworks overlap in practice with the requirements of the AI Act. The AI Act does not contradict the legal standards set out in the GDPR and NIS2 in any way. On the contrary, from the perspective of the hierarchy of legal regulations, they are equivalent due to the required mutual application. High-risk AI systems in the public sector require an impact assessment on fundamental rights, which is regulated in the GDPR Regulation. The technical requirements of the AI Act for accuracy, robustness, cybersecurity and human oversight intersect with the security measures of NIS2. This mutual application creates an integrated three-layer legal framework consisting of the following:

- − Rights and freedoms under the GDPR;

- − Resilience and cybersecurity under NIS2;

- − Responsible design and use of AI under the AI Act.

This legal framework is complemented by other important EU regulations: the Data Governance Act (trusted sharing and mediation of data), the Data Act (fair access to data), the Open Data Directive and national standards for open data. These laws, regulations and directives increase the availability of data for urban innovation, but require robust anonymization and systematic risk assessment, especially for spatial datasets [61].

In smart cities, these legal frameworks translate into specific obligations. In mobility and parking, where AI manages traffic flows (e.g., through adaptive intersections, predictive planning of urban public transport), the legal basis is usually public interest or statutory obligation. However, a process in the sense of the GDPR is usually required due to the large-scale collection of sensor and video data. Minimization (preference for aggregation and detection without identification), limited retention periods, clear marking of monitored zones and technical measures “privacy by design” are applied. We believe that from the perspective of NIS2, this is a critical infrastructure, as risk management measures, network segmentation, multi-factor authentication in dispatching, managed access, robustness and resilience tests of models, as well as contractual obligations of suppliers to regularly update and address vulnerabilities are necessary.

In public safety, video surveillance is only permissible if it is necessary and proportionate, including documented proportionality, limited scope, encryption, access control and clear information directly at the point of capture. Biometric data represent a special category—facial and emotion recognition are highly invasive and generally disproportionate in common urban scenarios. As stated in this context, Schreiber and Tippe, European data protection authorities, have repeatedly called for strict restrictions on these practices in publicly accessible spaces. If AI would interfere with rights, the limitations of automated decision-making under the GDPR and mandatory safeguards consisting in particular of human intervention, the right to express oneself as well as to challenge the decision through a remedy will apply. From the perspective of NIS2, camera and analytics platforms (edge/cloud) must be securely managed with patch management, model supply chain security, monitoring and incident response [62].

In the energy sector, the legal basis for processing consumption measurements is usually a legal obligation or public interest, while profiling requires a special process and so-called “by design/by default” measures. In practice, this means pseudonymization, access restrictions and, in particular, transparency towards households. NIS2 places strict demands on risk management, incident reporting and resilience, rigorous supplier monitoring and continuous resilience testing. The Data Act also facilitates fair access to data from connected devices for urban optimization AI, while maintaining GDPR guarantees. In waste management, it is necessary to pay special attention to the so-called DPIA (Data Protection Impact Assessment) tool for sensor and location data. This is a special tool for assessing the legitimacy and meaningfulness of the processing of personal data if the scope or frequency of monitoring significantly interferes with privacy. If a municipal enterprise according to Hansen et al. meets the sectoral and size criteria of the NIS2 Directive, mandatory risk management measures, service availability, incident reporting and resolution requirements will apply [63]. In e-government, as already mentioned above, transparency of AI interactions and information on profiling apply; purely automated decision-making is limited and associated with safeguards.

Castaldi et al. remind us that public procurement and contractual practice must reflect these requirements in technical specifications and contractual clauses [64]. From the GDPR perspective, these are precise agreements with intermediaries—defining operations, security measures, auditing and access to logs and data export for the purposes of DPIA, complaints and supervision. In joint processing, it is clearly necessary to adjust responsibilities and information in the joint controller regime. From the NIS2 perspective, it is appropriate to require the implementation of measures under Art. 21 (logging, encryption, training), incident reporting (early warning within 24 h, subsequent notification within 72 h, final within one month), regular penetration tests and security assessments, supplier due diligence and contractual sanctions for non-compliance. Where the AI Act applies (especially high-risk systems), complete technical documentation, records, instructions, evidence of security and human oversight should be required and requirements should be uniformly aligned with GDPR and NIS2.

Finally, according to Brenner, it is recommended that smart cities integrate all three of the above-mentioned regulations into a single “compliance gate”—AI Act, GDPR and NIS2 before procurement and before implementation [65]. It is also generally recommended to take into account not only the above-mentioned legal standards, but also the instructions of the National Security Office of the Slovak Republic as well as the national MIRRI standards. This integrated approach enables the development of trusted, secure and sustainable AI services that meet EU objectives, reduce risks of non-compliance, and support innovation and the quality of urban services.

3.5. AI Act, GDPR and NIS 2 Directive and Their Impact on Sustainability

As we have already mentioned, the AI Act, GDPR and NIS2 form a set of mutually complementary rules that ensure that the digitalization of cities is sustainable—environmentally, socially, and in terms of governance and resilience. Environmental sustainability is primarily manifested by the fact that the regulated, safe and transparent development of AI allows for the optimization of energy systems, transport and urban services without undue risk. In the context of mobility, these measures are reflected in lower emissions thanks to reliable adaptive signalling or predictive planning of urban public transport. In the energy sector, this is mainly about higher efficiency, demand flexibility and reduced losses in energy networks. With its emphasis on minimization and purpose limitation, GDPR leads to a smaller data burden, more efficient storage and reduction in unnecessary transfers, which also has an impact on the energy footprint of data processing. NIS2 works on preventive security and continuity—from network segmentation to vulnerability management. This reduces the risk of outages and accidents that would directly worsen environmental parameters such as unplanned congestion or forced shutdowns.

Social sustainability is based on trust, fairness and inclusion. The AI Act protects fundamental rights by prohibiting manipulative practices and social scoring, regulating high-risk uses and requiring clear information for individuals where AI interacts with humans. The GDPR guarantees predictability and control over personal data, data subjects’ rights and understandable information, while enforcing safeguards, including human intervention, in profiling and automated decision-making. NIS2 strengthens the security of the digital channels through which cities deliver services, thereby enhancing the availability and integrity of public services.

As we have shown above, sustainability in smart cities is not just about technological savings and emission reductions, but about a broader balance: safe AI increases efficiency, GDPR protects citizens and builds trust. NIS2 protects business continuity and resilience. When we apply these legal frameworks in an integrated manner with clear roles, processes and metrics, the digitalization of cities progresses faster, with less risk and with higher added value for both citizens and the environment.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1. Integrated Regulatory Framework (AI Act, GDPR, NIS2) as a Basis for the Sustainability of Urban AI Services

Interpretation of Findings and Mutual Synergies Between Regulations

By synthesizing the findings, we concluded that the AI Act, GDPR, NIS2 and the Open Data Directive form a comprehensive legal framework that, if implemented in an integrated manner, guides the entire life cycle of urban AI solutions, from design and procurement through deployment to oversight, auditability and data publication. The AI Act sets risk-based obligations for the design, marketing and use of AI, including mandatory fundamental rights impact assessments for selected high-risk uses in the public sector. The GDPR defines material boundaries for the processing of personal data and thus supports the fairness, clarity and predictability of AI decision-making. NIS2 increases the operational resilience and cybersecurity of AI-dependent urban services through risk management, incident management and supply chain security. It directly intersects with the AI Act requirements for cybersecurity of high-risk systems and with the GDPR for the security of personal data processing.

From a managerial perspective, the greatest added value is brought by the integrated “compliance gate”: the connection of the AI Act and the GDPR, supplemented by the NIS2 risk assessment before procurement or direct deployment in smart cities. The mutual application removes all duplications, harmonizes all deviations and creates a uniform basis for transparent communication with city residents.

As part of our research, we have identified potential risks and propose procedures for removing or eliminating them. The AI Act prohibits selected practices such as social scoring by public authorities, emotion recognition in work and schools, and remote biometric identification in real time in public spaces. On the one hand, this significantly strengthens the trust and protection of residents, but on the other hand, it can slow down the development of AI in smart cities. By using the above methods, targeted advertising could be applied, for example, which could ultimately bring more funds to the city itself. However, with regard to the legal regulation of the AI Act, it is necessary to state that the protection of the privacy of residents is more important in this regard than the unlimited development of AI and business. The GDPR requires that profiling and exclusively automated decision-making be accompanied by human supervision, which would control the entire process. The GDPR also guarantees the data subjects the right to express themselves, the right to rectification, the right to remove unwanted interference and the like. Again, these guarantees significantly protect the personal data of individuals and prevent unregulated processing of personal data by smart cities. On the other hand, such regulation can significantly slow down the development of smart cities. A theoretical slowdown in development can be seen at the development level because every change needs to be assessed through the protection of personal data, and it is obvious that the implementation of smart cities significantly interferes with the personal data and privacy of residents. Another aspect is the increased costs, as every city really needs to have GDPR specialists who, on the one hand, are present in automated decision-making and, on the other hand, resolve residents’ suggestions and complaints.