Abstract

Short-term wind speed forecasting is challenged by the nonlinear, non-stationary, and highly volatile characteristics of wind speed series, which hinder the performance of traditional prediction models. To improve forecasting capability, this study proposes a hybrid modeling framework that integrates multi-strategy adaptive particle swarm optimization (MASPSO), a convolutional neural network (CNN), a gated recurrent unit (GRU), and an attention mechanism. Within this modeling architecture, the CNN extracts multi-scale spatial patterns, the GRU captures dynamic temporal dependencies, and the attention mechanism highlights salient feature components. MASPSO is further incorporated to perform global hyperparameter optimization, thereby improving both prediction accuracy and generalization. Evaluation on real wind farm data confirms that the proposed modeling framework delivers consistently superior forecasting accuracy across different wind speed conditions, with significantly reduced prediction errors and improved robustness in multi-step forecasting tasks.

1. Introduction

In the context of the global energy transition, wind energy, as a clean and renewable resource, plays a crucial role in optimizing the energy structure and supporting carbon-neutrality goals [1,2]. However, the inherent randomness and volatility of wind speed cause fluctuations in wind power output, posing significant challenges for grid dispatching and system security. Enhancing the accuracy and reliability of wind speed forecasting has therefore become essential for ensuring the stable grid integration of wind power and promoting the sustainable development of the wind energy industry [3,4,5].

In recent years, the fusion of deep learning methods and intelligent optimization algorithms has become a prominent research trend in wind speed forecasting. For deep model fusion, ref. [6] proposed a CNN–GRU hybrid model for offshore wind farms, where CNN extracted spatial correlations among turbines and terrain effects, and GRU modeled temporal dependencies such as short-term trends and diurnal variations, enabling joint spatiotemporal representation. Ref. [7] incorporated an attention mechanism into wind speed forecasting models to dynamically weight key temporal features, such as pre-gust periods and peak wind speed intervals, thereby improving the stability of multi-step forecasting. Ref. [8] developed a variational mode decomposition (VMD)–CNN–GRU model to address wind speed non-stationarity by preprocessing fluctuating sequences prior to feature extraction.

Regarding optimization algorithm enhancement, PSO and its variants are widely employed because of their effectiveness in parameter tuning. Ref. [9] introduced a dynamic-inertia PSO to optimize support vector regression parameters for improved nonlinear wind speed modeling. Ref. [10] proposed an adaptive inertia weight strategy based on a Sigmoid function and a linearly decreasing scheme, markedly improving PSO’s optimization performance. Ref. [11] integrated an improved PSO with a deep belief network and an Elman neural network to construct a PSO–Hilbert–Huang transform (PSO-HHT) wind speed prediction model, achieving higher prediction accuracy and stability compared with traditional neural networks. Additionally, refs. [12,13,14,15] applied PSO to hyperparameter optimization in deep architectures such as the bidirectional gated recurrent unit (BiGRU), further demonstrating the effectiveness of improved PSO algorithms in complex wind speed forecasting tasks.

Overall, existing studies have achieved certain improvements in wind speed forecasting accuracy and stability through model fusion and algorithm enhancement. Nevertheless, several gaps remain, mainly reflected in the following aspects:

- Most existing CNN–GRU–Attention models rely on a serial structure that separates spatial and temporal feature learning, limiting the effective characterization of dynamic spatiotemporal interactions and resulting in degraded performance under highly fluctuating wind speed conditions.

- Existing PSO variants are sensitive to initialization and lack adaptive search and diversity-preserving mechanisms, making them prone to premature convergence and unstable performance in high-dimensional hyperparameter optimization.

- Attention mechanisms that primarily emphasize temporal weighting often insufficiently capture spatial feature heterogeneity, which reduces robustness and leads to degraded accuracy under stochastic, fluctuating, and extreme wind conditions.

To address the above limitations, this study develops an integrated hybrid forecasting framework combining spatiotemporal collaborative representation and adaptive parameter optimization. The main contributions are summarized as follows:

- A unified spatiotemporal learning architecture integrating CNN, GRU, and attention mechanisms is constructed to enhance the modeling of non-stationary and highly volatile wind speed sequences.

- An improved MASPSO algorithm is designed to improve hyperparameter optimization efficiency, expand the effective search space, and reduce sensitivity to initialization.

- A MASPSO–CNN–GRU–Attention hybrid forecasting model is developed to jointly optimize spatiotemporal feature learning and adaptive parameter tuning.

- Extensive experiments based on real wind farm data demonstrate the superior accuracy, robustness, and generalization performance of the proposed model across diverse operational scenarios.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the CNN–GRU–Attention hybrid forecasting model. Section 3 introduces the improved adaptive-strategy PSO algorithm and the overall hybrid prediction framework. Section 4 conducts model validation using a real wind farm case and evaluates prediction performance under different scenarios. Section 5 provides the conclusions.

2. CNN–GRU–Attention Prediction Model

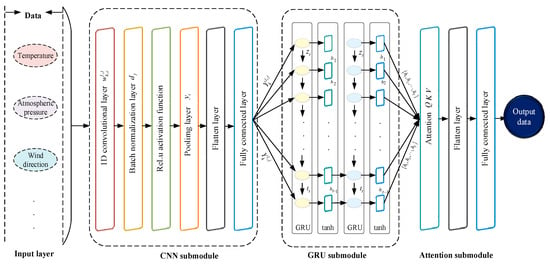

To address the heterogeneity of multi-source data in distributed wind turbines, this section develops CNN- and GRU-based models to extract spatial correlations among wind-speed–related features and to capture their temporal dynamic evolution. By further integrating an attention mechanism, the model adaptively assigns weights to multimodal inputs, enabling more accurate characterization of wind-speed variability. The overall architecture of the proposed CNN–GRU–Attention hybrid prediction framework is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

CNN–GRU–Attention prediction architecture.

2.1. Model Prediction Workflow

Figure 1 illustrates the CNN–GRU–Attention prediction architecture. The modeling process consists of the following steps:

- (1)

- Spatial feature extraction with CNN. Spatial correlations among multi-source inputs are extracted using stacked convolutional layers, followed by average pooling to reduce dimensionality and mitigate overfitting.

- (2)

- Temporal dynamic modeling with GRU. The extracted spatial features are fed into a GRU network to capture temporal dependencies across successive time steps through gated information flow.

- (3)

- Adaptive feature integration via attention. An attention mechanism is applied to assign adaptive weights to GRU hidden states, emphasizing informative temporal features.

- (4)

- Prediction generation. The attention-weighted features are passed through a fully connected layer to generate the final wind speed prediction.

2.2. Model Architecture and Component Design

2.2.1. Convolutional Neural Network

CNNs are primarily composed of convolutional and pooling layers, which serve as fundamental components for hierarchical feature extraction [16]. Convolutional layers perform localized scanning of input data using learnable filters to capture spatial feature patterns, while nonlinear activation functions further enhance the network’s ability to represent complex relationships. Pooling layers reduce spatial dimensionality, lower computational complexity, and mitigate overfitting, while retaining the most salient feature information.

During the convolution process, the size of each output feature map is determined by , and the convolution operation is expressed in Equation (1).

where is the output value at the neuron in the feature map of layer ; is an activation function, which is used to introduce nonlinear characteristics to the neuron; is the bias term; , are the convolution kernel weight and the element, respectively; is the number of input elements involved in the calculation; is the number of output feature maps.

The output at the first spatial position after convolution is further defined in Equation (2).

In the subsequent model construction, the pooling layer receives the convolutional output and performs dimensionality reduction through average pooling, as described in Equation (3).

where is the pooled output for the neuron in the feature map of layer ; is the number of elements within the pooling window; is the element in the pooling region.

2.2.2. Gated Recurrent Unit Network

While CNN captures spatial dependencies in wind speed observations, short-term forecasting performance is largely determined by the model’s ability to represent transient variations and local temporal trends. The GRU utilizes update and reset gates to balance historical memory and current inputs, alleviating gradient degradation in standard recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and facilitating accurate modeling of short-term dynamics [17,18]. Accordingly, GRU is selected as the temporal modeling component.

In this section, the pooling layer output (Section 2.1) is concatenated along the temporal dimension to form a sequence vector , where denotes the number of samples, represents the length of the wind speed time series, and is the flattened feature dimension. The resulting vector , derived from the CNN pooling output in Equation (3) at time , serves as the GRU input. The core computational process of the GRU is formulated in Equations (4)–(7).

The update gate regulates the retention of the previous hidden state and the incorporation of new information, as expressed in Equation (4).

where is the update gate at time ; is the sigmoid activation function, which maps the computed value to the range [0–1]; , are the input-to-gate and hidden-to-gate weight matrices, respectively; is the hidden state at the previous time step; is the bias term.

The reset gate determines the extent to which past information is suppressed based on the previous hidden state, as defined in Equation (5).

where is the reset gate at time ; , , are the corresponding weight matrices and bias term, respectively.

The candidate hidden state is computed from the current input vector and the reset-modulated previous hidden state, representing the potential new information to be incorporated into the GRU, as expressed in Equation (6).

where is the candidate hidden state at time ; is the hyperbolic tangent activation function, which maps the computed value to the interval [−1, 1]; , , are the corresponding weight matrices and bias term, respectively; is the element-wise multiplication operation.

The final hidden state is obtained by combining the new and previous information under the control of the update gate, as shown in Equation (7).

where is the final hidden state of the GRU at time , capturing both short- and long-term dependencies within the sequence.

2.2.3. Attention Mechanism

Although the GRU effectively models temporal dependencies in wind speed data, it cannot adaptively assess the relative importance of multi-source inputs. To address this limitation, an attention mechanism is introduced to enable dynamic feature weighting. Inspired by the selective focus of the human visual system, the attention mechanism assigns higher weights to salient features while suppressing less informative ones, thereby enhancing the model’s representation capability [19]. The basic steps are as follows.

(1) The computation begins by generating the query, key, and value vectors. As shown in Equation (7), the GRU aggregates spatiotemporal wind speed information into the final hidden state sequence , which serves as the input matrix for the attention module, enabling a transition from temporal feature learning to attention-driven weighting.

where , , are the query, key, and value vectors, respectively; , , are the learnable weight matrices, respectively.

(2) The attention scores are computed to quantify the similarity between the query and key vectors. For each query, the dot product with all keys is performed to obtain the corresponding attention scores. The formulation is given in Equation (9).

where , are the attention scores before and after normalization, respectively; is the key vector; is the transpose of the query vector; is the scaling factor.

(3) The attention weights are normalized to obtain a stable attention distribution. The raw attention scores are transformed into a probability distribution via the Softmax function, ensuring that all weights sum to one. This normalization prevents excessive emphasis on individual elements and promotes a balanced contribution to the final output. The detailed formulation appears in Equation (10).

where is the attention weight of the key under the query.

(4) The weighted summation is then performed to generate the attention output, aggregating the relevant feature information. The corresponding formulation is shown in Equation (11).

where is the final output of the attention mechanism; is the value vector in the attention mechanism.

2.3. Comparative Architecture Analysis

The proposed wind speed prediction model integrates CNN, GRU, and attention mechanisms to construct a deep learning framework capable of capturing both spatial correlations and temporal dependencies from multi-source input data. Following ref. [20], representative benchmark models—including graph convolutional networks (GCN), long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, Transformer, and non-temporal classifiers such as support vector machines (SVM) and random forests (RF)—are selected for comparative evaluation, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Architecture comparison.

3. MASPSO-Based Hybrid Wind Speed Prediction

3.1. MASPSO Algorithm

As an enhanced variant of PSO, the MASPSO algorithm improves global search capability and mitigates premature convergence through adaptive mechanisms [21]. In the standard PSO framework, each particle updates its velocity and position iteratively, as described in Equation (12).

where , are the updated velocity and new position of the particle for the decision variable at iteration , and , represent their corresponding values at iteration , respectively; is the personal best position searched by the particle ; is the global best position searched by the whole particle swarm; , are random numbers within the interval [0, 1]; is the inertia weight; , are the learning factors.

Accordingly, an adaptive two-stage optimization strategy is introduced, consisting of a fast screening stage and a fine-tuning optimization stage. The detailed mechanisms of each stage are described as follows.

(i) Phase I: Fast screening

This stage allocates 40% of the iterations and 60% of the particles to perform global exploration with a large inertia weight and expanded search bounds.

(ii) Phase II: Fine-tuning optimization

(1) Quantile-based adaptive boundary updating

Building on the boundary values and of the decision variables obtained in the first phase, the search boundaries and for the second phase are adaptively adjusted as defined in Equation (13).

where , are the 25th and 75th percentiles of the first-phase solution set for the decision variable; , are the boundary relaxation coefficient and interquartile range of the decision variable, respectively.

(2) Adaptive parameter adjustment

A nonlinearly decreasing inertia weight is applied to balance early global exploration and later rapid convergence, as shown in Equation (14).

where , are the maximum and minimum values of , respectively; is the maximum number of iterations.

The learning factors and are assigned nonlinearly decreasing and increasing strategies, respectively, to guide particles toward both individual and global optima.

where , , are the maximum and minimum values of the individual and global learning factors.

(3) Elite mutation mechanism

In later iterations, mutation is applied to the top 5% elite solutions in the external archive based on crowding-distance ranking. The mutation intensity decreases progressively and is adaptively adjusted according to the distance of each solution from the archive center, thereby enhancing population diversity and reducing the likelihood of premature convergence.

(1) Adaptive mutation intensity

The position after mutation is given by the following:

where is the iteration-dependent mutation intensity; is the base mutation factor; is a random disturbance factor.

The mutation operator varies with iteration progress and particle–archive proximity:

① Early stage (): Gaussian mutation strengthens global exploration:

② Middle stage (): Uniform mutation maintains a balanced search:

③ Middle stage (): Cauchy mutation enhances jump capability and helps escape local optima:

(2) Distance-adaptive regulation

The Euclidean distance used to measure the proximity between particle and its nearest archive solution is expressed as follows:

where is the external archive that stores all non-dominated solutions.

To maintain numerical stability, the distance is normalized:

where is the normalized distance of the sample; , are the maximum and minimum distances among all samples, respectively.

Finally, the mutation intensity is adjusted as follows:

where is the adjusted mutation intensity for the sample.

3.2. MASPSO–CNN–GRU–Attention Forecasting Workflow

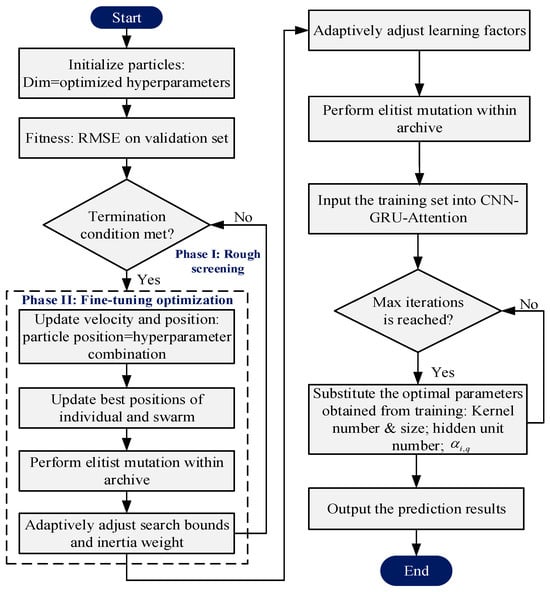

The short-term wind speed hybrid forecasting workflow based on the MASPSO–CNN–GRU–Attention framework consists of the following steps, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Forecasting workflow of the hybrid model.

- (1)

- Data preprocessing. Multi-source wind farm data are cleaned, normalized, and screened for relevant features. The samples are then partitioned into training, validation, and testing sets at a ratio of 7:2:1.

- (2)

- Model construction. The CNN module extracts spatial representations of the input variables, the GRU captures temporal dependencies, and the attention mechanism adaptively reweights salient features. A fully connected layer maps the fused spatiotemporal features to the prediction output.

- (3)

- Hyperparameter optimization. The validation-set root mean square error (RMSE) is used as the fitness function for the two-stage MASPSO search. The optimization variables and their corresponding search ranges include the number and size of convolutional kernels in the CNN submodule, the number of hidden units in the GRU submodule, and the weighting coefficients in the attention submodule.

- (4)

- Model training and validation. The model is trained using the Adam optimizer, while MASPSO determines the optimal hyperparameters. The validation and testing sets are used to assess forecasting accuracy and generalization.

- (5)

- Prediction generation. New input data are passed sequentially through the CNN, GRU, and attention modules to produce the final wind speed forecasts, supporting operational decision-making for wind power scheduling.

4. Case Study

4.1. Experimental Environment and Parameter Settings

4.1.1. Hardware and Software Environment

This study is conducted on a high-performance computing platform equipped with an NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPU, 128 GB of memory, and an Intel Xeon Gold 6248R CPU operating at 2.4 GHz. The software environment is developed based on Python 3.9, with TensorFlow 2.6.0 and PyTorch 1.9.0 employed for model construction and training. Experimental data are stored in a distributed file system to ensure efficient data access and processing.

4.1.2. Data and Feature Parameters

The experimental data are derived from measured wind-speed records collected at a regional wind farm. The wind farm is equipped with 2.5 MW permanent magnet synchronous generators, featuring a hub height of 90 m, a rotor diameter of 130 m, and an operating wind-speed range of 3–25 m/s. Wind speed and direction are measured using an ultrasonic anemometer installed approximately 50 m from the wind farm center and averaged at 15-min intervals. The dataset spans January to March 2024 and includes 8640 samples.

During data preprocessing, Min–Max normalization is applied to scale all variables into the range [0, 1]. The dataset is then partitioned into training, validation, and testing subsets with a ratio of 7:2:1. Input features are selected based on the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) and information value (IV) criteria [22]. Features with PCC ≥ 0.25 and IV ≥ 0.45 are retained for model construction, and the corresponding results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Feature selection results.

4.1.3. Model Architecture and Training Parameters

The core architecture of the proposed MASPSO–CNN–GRU–Attention model is configured as follows. The CNN module adopts the ReLU activation function. The GRU module consists of a single layer with 64 hidden units and a dropout rate of 0.2. An additive attention mechanism with a hidden dimension of 32 is employed to enhance feature representation. The final output is generated by a fully connected layer with a linear activation function. The corresponding hyperparameter search ranges optimized by MASPSO are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Key hyperparameter value ranges.

After optimization using the MASPSO algorithm, the training parameters are configured according to different forecasting horizons. Specifically, the learning rate is set to 0.004 for 1-h-ahead forecasting to accelerate convergence and capture local wind-speed fluctuations. For 2-h-ahead and longer horizons, the learning rate is reduced to 0.003 to suppress noise overfitting and improve long-term forecasting stability. The number of training iterations is uniformly fixed at 200, the batch size is set to 32, and the Adam optimizer is adopted for all prediction tasks. To ensure fair and consistent performance evaluation, the architectures and training settings of all comparative models are aligned with those of the proposed model.

4.2. Performance Evaluation Metrics

To ensure consistent evaluation across experiments, Table 4 summarizes the performance metrics adopted in this study, including mean absolute error (MAE), RMSE, and the coefficient of determination (). Here, denotes the total number of samples, represents the actual value of the sample, is the corresponding predicted value, and denotes the mean of the actual observations. Interval uncertainty analysis is conducted under the 95% confidence interval (95% CI), where denotes the distribution quantile with degrees of freedom, and is the sample standard deviation, using prediction interval coverage probability (PICP) and prediction interval normalized average width (PINAW).

Table 4.

Evaluation metrics.

4.3. Model Performance Analysis

4.3.1. Wind Speed Forecasting Results

(1) Baseline vs. proposed model performance

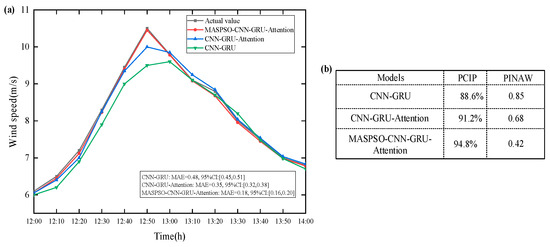

The CNN–GRU model is selected as the baseline. The forecasting results and statistical values of different models, including CNN–GRU–Attention with and without hyperparameter optimization, are compared against the actual wind speed, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Wind speed prediction results and statistical values. (a) Wind speed forecasting results; (b) Prediction interval metrics.

Figure 3a shows that all models generally follow the overall trend of wind speed variation, but clear performance differences appear during rapid changes. Around the peak period near 12:50, the actual wind speed reaches about 10.5 m/s, while the MASPSO-CNN–GRU–Attention model maintains a very small deviation of approximately 0.1 m/s (MAE = 0.18, 95% CI = [0.16, 0.20]), indicating stable prediction accuracy under extreme wind conditions. In contrast, the CNN–GRU–Attention model (MAE = 0.35, 95% CI = [0.32, 0.38]) and the CNN–GRU model (MAE = 0.48, 95% CI = [0.45, 0.51]) exhibit larger errors of roughly 0.3–0.5 m/s and slower responses to the wind speed peak. Moreover, the non-overlapping 95% CIs between the proposed and comparison models (upper bound: 0.20 vs. lower bound: 0.32) confirm the statistical significance of the accuracy improvement, while a PICP close to the nominal 95% level and a PINAW reduction exceeding 40% further demonstrate reliable uncertainty quantification, as shown in Figure 3b.

(2) Multi-period generality validation

To evaluate the generality of the proposed model, two additional representative time periods are introduced in addition to the simulated period (Figure 3), and the MAE and 95% CIs for each period are reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Model error comparison across multiple wind-speed forecasting horizons.

Table 5 shows that the proposed model consistently achieves lower MAE values than the benchmark models across different wind-speed scenarios and forecasting periods. The non-overlapping 95% CIs indicate that the observed accuracy improvement is statistically significant. Even under highly fluctuating wind conditions, the MAE remains below 0.24, corresponding to an approximate 60% reduction compared with the CNN–GRU model. These results demonstrate the stable and robust performance of the proposed model across varying time intervals and wind-speed regimes.

(3) Component-wise ablation analysis

On this basis, this section constructs five gradient models to conduct ablation experiments, aiming to quantitatively evaluate the contribution of each individual component in the proposed forecasting framework to prediction accuracy. The corresponding results are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Ablation study results.

Table 6 indicates that each component contributes significantly to prediction accuracy. CNN extracts spatial features to complement GRU-based temporal modeling, attention enhances key features via dynamic weighting, and MASPSO improves generalization through hyperparameter optimization. Their synergistic integration yields a 69.0% accuracy improvement, confirming the effectiveness of the proposed hybrid architecture.

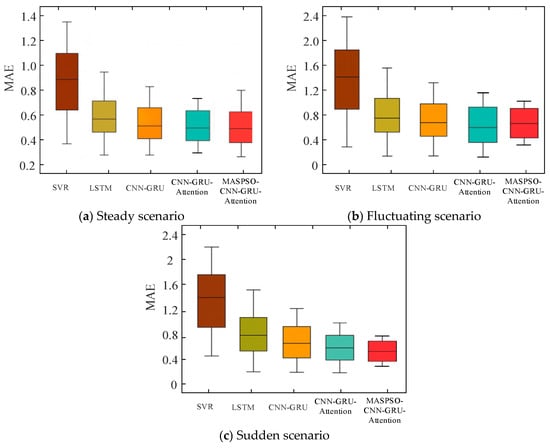

(4) Comparison with classical models under wind-speed fluctuations

The proposed approach is further evaluated under different meteorological conditions by comparison with representative forecasting methods, including support vector regression (SVR) and LSTM. Three typical wind-speed scenarios are considered, and MAE is used as the evaluation metric. The results are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Model performance under different meteorological conditions.

As shown in Figure 4, the proposed MASPSO–CNN–GRU–Attention model consistently achieves the lowest MAE across all wind speed scenarios. In particular, its MAE is approximately 40% lower than that of the traditional SVR model, demonstrating a substantial improvement in forecasting accuracy. Furthermore, the proposed model maintains stable error levels under fluctuating and abrupt wind speed conditions, indicating strong robustness and adaptability to complex meteorological variations.

4.3.2. Prediction Performance Analysis

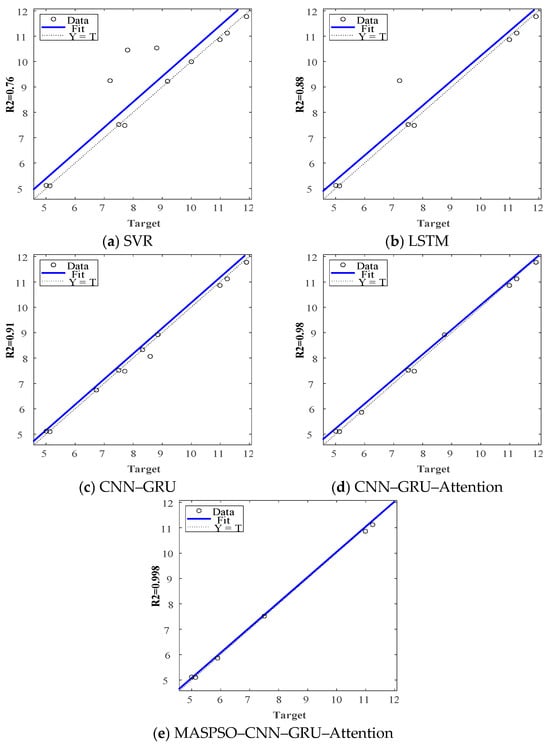

To further compare model performance on the test set, the fitting accuracy of five representative forecasting models is analyzed, and the comparative results are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Prediction accuracy analysis.

As shown in Figure 5, the SVR and LSTM models exhibit widely scattered points that deviate from the diagonal, resulting in relatively low values of and indicating limited fitting capability. The CNN–GRU and CNN–GRU–Attention models show a closer concentration around the diagonal, reflecting improved fitting accuracy due to enhanced spatiotemporal feature extraction. The MASPSO–optimized CNN–GRU–Attention model achieves the tightest alignment with the diagonal and the highest value of , demonstrating that adaptive hyperparameter optimization further improves the model’s ability to capture short-term wind speed trends and local fluctuations.

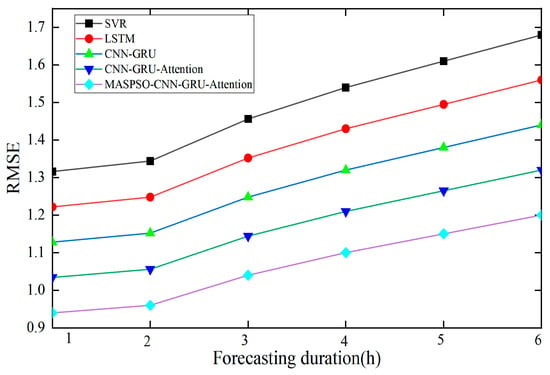

4.3.3. Multi-Step Forecasting Performance

Figure 6 shows that the RMSE of all models increases with the extension of the forecasting horizon. However, baseline models such as SVR and LSTM exhibit a much steeper error growth, particularly at longer horizons. In contrast, the proposed model maintains the lowest RMSE with a relatively smooth increasing trend, indicating effective suppression of error accumulation and superior stability in multi-step wind speed forecasting.

Figure 6.

Variation in multi-step forecasting errors.

Error growth mainly stems from cumulative uncertainty in wind speed sequences and from a degradation in capturing long-horizon spatiotemporal dependencies. As forecast horizons extend, random errors accumulate, and the information retention of GRU hidden states declines, whereas the MASPSO-optimized attention mechanism dynamically reweights long-term features to mitigate error growth.

4.3.4. Computational Time Performance

According to the hardware configuration specified in Section 4.1.1, the total training and inference times for each model are measured over 200 iterations, and the results are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Time performance metrics of different models.

Although the training time of the proposed model increases by approximately 34% due to MASPSO-based hyperparameter optimization, its inference speed is improved by 15–20% compared with the benchmark models. The single-sample inference time is 2.5 ms, which satisfies the real-time dispatch requirement of wind farms, where the inference latency is required to be less than 10 ms.

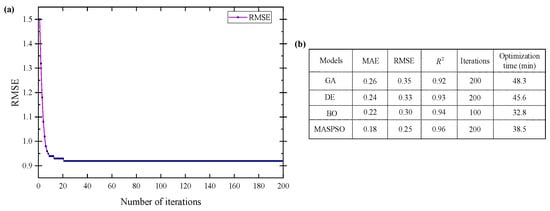

4.4. MASPSO Parameter Optimization Analysis

The MASPSO algorithm is evaluated using RMSE as the fitness metric. With the CNN–GRU–Attention architecture fixed, identical hyperparameters are optimized using MASPSO, genetic algorithm (GA), differential evolution (DE), and Bayesian optimization (BO), as illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

MASPSO optimization performance and comparison with other algorithms. (a) RMSE convergence; (b) Performance comparison.

Figure 7a demonstrates the convergence behavior of the MASPSO algorithm over 200 iterations, showing a fast initial error reduction, followed by gradual convergence and final stabilization. As shown in Figure 7b, the MASPSO-optimized model outperforms GA, DE, and BO across all evaluation metrics. Compared with GA, DE, and BO, MAE is reduced by 30.8%, 25.0%, and 18.2%, respectively; RMSE by 28.6%, 24.2%, and 16.7%; and is improved by 4.3%, 3.2%, and 2.1%. Although BO is executed for 100 iterations and MASPSO for 200 iterations, MASPSO incurs only a slight increase in optimization time relative to BO and remains significantly faster than GA and DE. Moreover, MASPSO exhibits markedly faster convergence than GA and DE, while achieving superior final solution quality compared with BO. This advantage stems from the two-stage search and elite mutation mechanisms of MASPSO, which balance global exploration and local refinement, leading to simultaneous improvements in error metrics and goodness-of-fit.

5. Conclusions

This study develops a hybrid short-term wind speed forecasting model based on the MASPSO–CNN–GRU–Attention framework and validates its effectiveness using measured wind farm data. By jointly enhancing spatiotemporal feature learning and hyperparameter optimization, the proposed model achieves consistently superior forecasting accuracy and stability. Comparative results demonstrate that it performs robustly under steady, fluctuating, and abrupt wind speed conditions, effectively capturing both short-term trends and local variations, while maintaining low error growth in multi-step forecasting tasks. These findings confirm the proposed approach as an effective and reliable solution for short-term wind speed prediction.

Despite its effectiveness, the proposed method exhibits sensitivity to noisy training data, and the absence of embedded wind-field physics limits its transferability and interpretability. Future work will incorporate physics-informed constraints and Shapley additive explanations together with attention-weight visualization to enhance robustness and explainability, and will further assess generality using multi-wind-farm and long-term datasets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.D. and Y.S.; Methodology, H.D.; Software, H.D.; Validation, H.D. and Y.S.; Formal analysis, H.D.; Investigation, H.D.; Resources, Y.S.; Data curation, H.D.; Writing—original draft preparation, H.D.; Writing—review and editing, Y.S.; Visualization, H.D.; Supervision, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by “Key Laboratory of Smart Grid of Ministry of Education for Tianjin University” and “North China University of Water Resources and Electric Power”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cheng, R.; Yang, D.; Liu, D.; Zhang, G. A reconstruction-based secondary decomposition-ensemble framework for wind power forecasting. Energy 2024, 308, 132895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.; Akimov, A.; Gray, E.M.A. Techno-economics of offshore wind-based dynamic hydrogen production. Appl. Energy 2024, 374, 124030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Kou, H.; Zou, R. A review of predictive uncertainty modeling techniques and evaluation metrics in probabilistic wind speed and wind power forecasting. Appl. Energy 2025, 396, 126234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiliotis, E.; Theodorou, E. Improving wind power forecasting accuracy through bias correction of wind speed predictions. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 83, 104599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Che, J.; Hu, K.; Qin, W. Deterministic and probabilistic wind speed forecasting using decomposition methods: Accuracy and uncertainty. Renew. Energy 2025, 243, 122515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Wan, A.; Ji, Y.; AL-Bukhaiti, K.; Yao, Z. Improving short-term offshore wind speed forecast accuracy using a VMD-PE-FCGRU hybrid model. Energy 2024, 295, 131016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, D.; Cui, H.; Lv, L.; Guo, J. A novel decomposition-prediction hybrid model improved by dual-channel cross-attention mechanism for short-term wind speed prediction. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 162, 112550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Yun, S.; Jia, L.; Guo, J.; Meng, Y.; He, N.; Li, X.; Shi, J.; Yang, L. Hybrid VMD-CNN-GRU-based model for short-term forecasting of wind power considering spatio-temporal features. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 115, 105982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladipo, S.; Sun, Y.; Adeleke, O. An Improved Particle Swarm Optimization and Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System for Predicting the Energy Consumption of University Residence. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy 2023, 18, 8508800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q.A.; Elsakka, M.M.; Korovkin, N.V.; Refaat, A. A novel EPSO algorithm based on shifted sigmoid function parameters for maximizing the energy yield from photovoltaic arrays: An experimental investigation. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 102967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.-Y.; Rioflorido, C.L.P.P.; Zhang, W. Hybrid deep learning and quantum-inspired neural network for day-ahead spatiotemporal wind speed forecasting. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 64, 122645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Chen, X.; Han, H. A novel hybrid ensemble approach for wind speed forecasting with dual-stage decomposition strategy using optimized GRU and transformer models. Energy 2025, 329, 136739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruque, M.O.; Hossain, M.A.; Alam, S.M.M.; Khalid, M. Constraint-aware wind power forecasting with an optimized hybrid machine learning model. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 27, 101026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, F.; Song, X.; Wang, Y.; Qin, C. A New Combined Prediction Model for Ultra-Short-Term Wind Power Based on Variational Mode Decomposition and Gradient Boosting Regression Tree. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chen, F.; Liu, Z.; Qiao, H. Overcoming Data Scarcity in Wind Power Forecasting: A Deep Learning Approach with Bidirectional Generative Adversarial network and Neighborhood Search PSO Algorithm. IEEE Access 2024, 245, 3507154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. CNN-GRU model based on attention mechanism for large-scale energy storage optimization in smart grid. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1228256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Hu, S.; Shao, H.; Shi, P.; Li, R.; Li, D. A spatio-temporal forecasting model using optimally weighted graph convolutional network and gated recurrent unit for wind speed of different sites distributed in an offshore wind farm. Energy 2023, 284, 128565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Gao, G.; Li, B.; Wang, W.; Ghannouchi, F.M. A Novel Lightweight Grouped Gated Recurrent Unit for Automatic Modulation Classification. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2024, 446, 3402975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Niu, D.; Gao, T.; Wang, K.; Sun, L.; Li, M.; Xu, X. A novel framework for ultra-short-term interval wind power prediction based on RF-WOA-VMD and BiGRU optimized by the attention mechanism. Energy 2023, 269, 126738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyangon, J. Physics informed neural networks for maritime energy systems and blue economy innovations. Mach. Learn. Earth 2025, 1, 011002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Su, X.; Wei, B. A self-adjusting representation-based multitask PSO for high-dimensional feature selection. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 98, 102084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, B.; Wang, X. A new filter feature selection algorithm for classification task by ensembling pearson correlation coefficient and mutual information. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 131, 107865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.