Abstract

Homegardens are traditional agroforestry systems that harbor genetic resources and ancestral knowledge, as well as contributing to food security and self-sufficiency in many rural communities. In this study, we analyze homegardens in a Mixtec community in coastal Oaxaca, Mexico, to document their arrangement and components, the useful flora and fauna they contain, and the social, cultural and economic aspects associated with their management. We used snowball sampling to perform semistructured interviews with 36 women in charge of homegardens, which represented 10% of the total homes in the community. During guided tours, we diagrammed the homegardens and collected and identified plant specimens to compile a full floristic listing. Plant specimens were deposited in the CHAP herbarium. We also calculated the Jacknife alpha diversity index and Sorensen’s beta diversity index to quantify the diversity of the garden flora. We summarized the interview data using descriptive statistics and performed a multiple regression analysis to evaluate the effects of the size of the homegarden and the homegarden owner’s age, years of school attendance, and language use on the number of useful plant species in the garden. Additionally, we conducted a multiple correspondence analysis on the homegardens, the sociodemographic variables, and the plant species contained. The components of the homegardens were the main dwelling, patio, kitchen, bathroom, chicken coop, and pigpen. We documented 15 animal species from 15 genera and 13 families and 236 plant species from 197 genera and 84 families. The most represented plant families were Araceae, Fabaceae and Apocynaceae. The main plant uses were ornamental, edible, and medicinal. The multiple correspondence analysis and multiple regression both showed sociodemographic variables to make a very low contribution to homegarden species richness (evidenced by low percentage variance explained and no statistically significant effects, respectively). The first-order Jacknife diversity index estimated a total of 309 plant species present in the homegardens, indicating high agrobiodiversity. The Sorensen index value ranged from 0.400 to 0.513. Similarity among the gardens was mostly due to high similarity among edible plants. There was community-level resilience in family food self-sufficiency, as 80.56% of the interviewees use harvest from their homegardens to cover their families’ food needs. Women play a central role in the establishment and management of the gardens. Overall, our findings demonstrate that homegardens in this community are sustainable; have high agrobiodiversity; provide food, medicine, and well-being to residents; contribute to food self-sufficiency; and conserve agrobiodiversity as well as traditional culture and knowledge.

1. Introduction

Agroforestry systems (AFS) are a method of natural resource use and management in which woody perennial species (trees, shrubs, palms), agricultural crops and/or livestock occupy the same land, either simultaneously or in temporal sequence, such that their interaction provides benefits [1,2,3]. Traditional agroforestry systems (TAFS) are the result of land management practices that have developed over the past 10,000 years [4,5]. They represent a knowledge base generated by the interaction of local people with their environments [6]. TAFS are highly varied, including systems used in pre-Hispanic, colonial, contemporary, and recent times and in rural, peri-urban, and urban areas [7,8,9]. TAFS promote the conservation of diverse ecosystems, genetic resources, and community biocultural heritage [9,10,11].

One of the oldest and most important TAFS are homegardens. Homegardens are areas near the family dwelling [12,13] where multi-use tree, shrub, and herbaceous species are cultivated in the presence of domestic or sometimes wild animals, all under the family’s management [14]. These spaces are also known as kitchen gardens, dooryard gardens, or house lot gardens in English. In Mexico, they can be called solares, traspatios, patios, or tecorrales in Spanish; calmil in Náhuatl; ekuaro in Purépecha, and patxoconna in Maya [9,15]. They are a complex and diversified system of traditional agricultural production, in which the domestication, conservation, and diversification of plant and animal species occur [16,17].

Homegardens generally contain plants with diverse uses (e.g., medicinal, ornamental, edible, aromatic). They contain cultivated, semicultivated and wild plants with varying degrees of management. They provide healthy and nutritious foods, and they are mostly managed by women [18,19,20]. In Mexico, there is evidence that edible plants were domesticated by indigenous peoples, showing that human sociocultural factors and resource management can have evolutionary effects on plants [21].

Homegardens constitute a reservoir of agrodiversity and biodiversity associated with indigenous regions [22]. This includes the knowledge, use, and management of a large number of plant species through complex interactions between the local communities and their environment [23]. Given their importance around the world, homegardens have been the subject of numerous studies of topics including their diversity, their capacity to provide healthy and nutritious food and thus improve food security, their impact on conserving agrobiodiversity, their provision of ecosystem services, and their role in climate change mitigation and adaptation [17,18,24,25,26,27,28], which is why they are considered one of the most sustainable agroecosystems in the world. They have high value in stability, diversity and adaptability [15,17].

Today, this ancestral practice represents a form of resistance against the current economic model [29] that has impacted the lives of inhabitants. This is especially the case in rural and indigenous populations, where there has been a loss of culture around the management and use of natural resources [30], endangering traditional production processes, biocultural diversity, and food safety, sovereignty, and self-sufficiency [29,31]. In Mexico specifically, homegardens are threatened by a lack of market for their products, environmental degradation, pressure from outside technologies [32] and the increase in consumption of imported and processed foods [31]. For example, in a study of homegardens in Yucatán, community members mentioned that younger people had begun to prefer processed foods purchased from shops [33]. They are also affected by increasing urbanization in rural areas, which leads to a decrease in productive spaces and a reduction in species diversity [31]. However, in small communities where indigenous languages are spoken, homegardens continue to contribute strongly to food security and self-sufficiency [34,35].

The different historical, socioeconomic, and geographical contexts in rural areas have helped preserve more sustainable peasant production systems, such as homegardens [32]. In indigenous communities, these systems have persisted for centuries, meeting their basic needs and contributing to their social, economic, and environmental well-being [32]. In these cases, the sustainability of homegardens is enhanced by soil fertility properties, agricultural heterogeneity, the connection of practices with other homegardens, family participation, and local traditional knowledge [18].

Several studies have examined the role of gardens in food security and self-sufficiency. We define food self-sufficiency as a population’s ability to satisfy its food needs through local production [36,37]. Food security is the constant and year-round access to food that is sufficient in both quantity and quality to satisfy the food needs of all members of a household, enabling them to have an active and healthy life [13,38]. Food sovereignty is the capacity of a country or region to guarantee the sustained production and supply of food and allow every family and person to exercise their right to adequate food [38,39]. Various useful species have been documented in these gardens, with numbers ranging from 76 to 369, most of them edible, ornamental and medicinal [6,17,18,40,41,42]. Several studies have examined the influence of sociodemographic variables (age, gender, occupation, years of school) on homegardens [24,43,44].

Oaxaca is the Mexican state with the highest biological, cultural, and agroecological diversity in the country, resulting from a long pre-Hispanic ethno-agroecological tradition [22]. Despite this marked biodiversity and the presence of 16 distinct ethnic groups, there are regions and communities where no ethnobotanical studies have been performed [45]. According to Manzanero-Medina et al. [46], by 2018, there had been 50 studies related to homegardens distributed among the different regions of the state. Four additional studies have since been published: one on the use and management of plant resources in the state [47], one on the homegardens in the coastal region of the state [48], one on the agroforestry systems of coastal Mixtec and Afro-mexican communities [49], and one on the floristic diversity and socioeconomic aspect of homegardens in Santa María Temaxcalapa, Villa Alta, Oaxaca [50].

The coastal region of Oaxaca comprises three districts, Pochutla, Juquila and Jamiltepec, which include areas that are highly ecologically and floristically diverse and well conserved [23]. The ethnic groups present are coastal Mixtec, Chatino, Afro-Mexican, and mestizo [46]. In this region, homegardens are a source of conserved genetic resources, ancestral knowledge, and food security, and they provide resources used by marginalized communities daily to meet their basic needs [23]. However, as is the case in Mexico more generally, homegardens in this region are threatened by the cultivation of introduced species [48], land-use change, and deforestation [49].

Previous studies in this region have shown a diversity of homegarden systems in the region. For example, Méndez-Pérez [48] documented the homegardens of the coast of Oaxaca, Mexico, where they chose 30 random sites in the region and recorded 106 species grouped into six clusters: coconut-palm, Leucaena-soursop, coconut-noni, zapote-mango, banana-palm, and zapote-papaya. Pérez-Nicolás et al. [49] described six agroforestry systems: pineapple groves in Mixtec communities, coconut groves in Afro-mexican communities, and milpas, potreros, and acahuales in both communities. One of these communities was Santiago Tetepec, which belongs to the Mixtec ethnic group, with a tropical semi-deciduous forest vegetation type [51]. It has diverse TAFS, including homegardens, and still conserves many traditional knowledge and management practices [49]. In this study, we aimed to document and describe the components and arrangement of the homegardens of Santiago Tetepec, including the diversity and uses of flora and fauna that are housed in homegardens. We also analyzed whether the number of plant species in the homegardens was affected by the size of the garden or sociodemographic variables of the garden’s owners. Finally, we analyzed the role of edible plants in the community’s food self-sufficiency.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

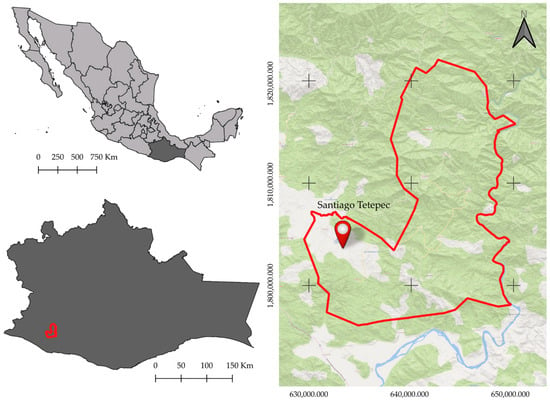

Santiago Tetepec is located in the district of Jamiltepec in the coastal region of the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, between the coordinates of 16°19′20″ north latitude and 97°44′53″ west longitude, with an area of 290.9 km2 (Figure 1). It is located in the coastal range of the Sierra Madre del Sur at an altitude ranging from 260 to 1700 m above sea level. The climate is warm subhumid with summer rains, the average annual temperature is 26.5 °C and the average annual precipitation is 1103 mm [52,53]. The soil types present in the municipality are Cambisol in 65.7% (19,113 ha), Regosol in 18.4% (5371 ha), Gleysol in 8.2% (2403 ha), Acrisol in 6% (1750 ha) and less than 2% Fluvisol (382 ha) and Phaeozem (69 ha) [54]. The community is located in the Costa Chica-Río Verde hydrological region. The perennial rivers present in the municipality are the Coyul, Gallango, Arena, Soledad and Verde [53].

Figure 1.

Map of the location of Santiago Tetepec, Oaxaca.

The land uses in the municipality include cultivated grassland, rain-fed agriculture, and human settlements. The vegetation present is pine–oak forest, secondary vegetation to pine–oak forest, secondary vegetation to tropical semi-deciduous forest, and secondary vegetation to montane cloud forest [51]. Wildlife species include white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), raccoon (Procyon lotor), European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus), nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus), green iguana (Iguana iguana), Mexican spiny-tailed iguana (Ctenosaura pectinata), rattlesnakes (Crotalus sp.), and orange-fronted parakeet (Eupsittula canicularis), among others [55].

The community has 1200 inhabitants, comprising 637 women (53.08%) and 563 (46.92%) men residing in 351 dwellings [56,57]. There is a primary school, electricity, running water, paved and dirt roads, internet and phone service, but no sewer system. The main economic activities are agriculture, followed by animal husbandry and commerce [55].

2.2. Diagnosis and Request for Authorization

We received authorization to perform the study from the municipal president of Santiago Tetepec, during a meeting in which we explained the objectives and methods and committed to delivering the results of the study in writing to the municipal authority in the form of a printed thesis. Then, during the month of September 2023, we performed 10 tours of the community in order to provide a diagnosis of the location, approach the residents, and select the homegardens to be considered in the study.

2.3. Survey Application

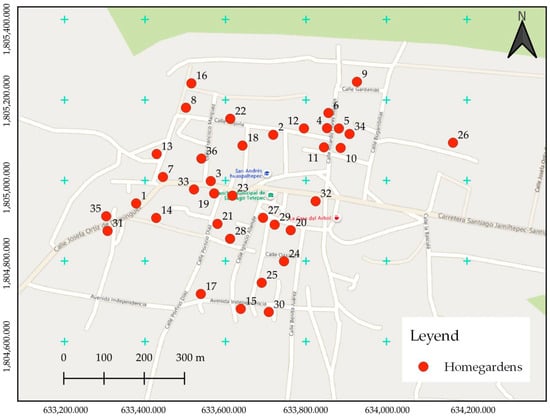

We interviewed women from 36 homes, which represents 10% of the total dwellings in the community [58,59]. We used “snowball sampling” [13,58,60], which consisted of selecting an initial sample of individuals, who then during the course of their interviews identified other potential interviewees, in order to complete the sample [61], since not all of the people could participate due to lack of time. This sampling method has some limitations, including the possibility of generating a limited sample that may not be useful for drawing conclusions at the population level, and that recommended participants may be oriented toward a profile that the researcher is seeking. However, it is advantageous in terms of practicality and efficiency since the initial participants make introductions with additional participants, which can also facilitate the establishment of trust with new participants [62]. Our interviewees included homegardens from both the center and edges of the community (Figure 2). We ensured that interviewees were distributed across the whole community and that the sample was as representative as possible.

Figure 2.

Dwellings with homegardens where we performed interviews and tours in the community of Santiago Tetepec, Oaxaca.

We designed a semi-structured interview form covering the following topics: socioeconomic data, components and arrangement of the homegarden, species uses, management of the homegarden, agroforestry practices, cultural value, and production of the garden. We visited the homegardens, asking women over the age of 18 whether they wished to participate and had time to grant us an interview and guided tour of their homegarden. Both initial contact and interviews/garden tours were performed in October and November 2023. The initial contact meeting consisted of introducing ourselves to the female head of the household, explaining the motivation behind the thesis project and its objectives, inquiring about their willingness to participate, and scheduling a date and time for the interview. The interview and tour were then performed on the agreed upon date, as described in the following section.

2.4. Tours and Collections

We toured each garden with the interviewee to observe its arrangement and generate a diagram. In June 2024, we collected specimens of wild species in the gardens to be identified, herborized and deposited in the CHAP herbarium at the Division of Forestry Sciences at the Autonomous University of Chapingo. Each specimen was tagged with the following data: municipality, vegetation type, soil characteristics, altitude, geographic coordinates, life form, and height of the individual, collection date, and name of the collector. Well-known species—especially ornamentals, cultivated species, and fruit trees—were identified and photographed without collecting specimens for the herbarium.

2.5. Species Identification

Plant species were identified using floristic listings from the following works from the same region: Catálogo de nombres vulgares and científicos de plantas mexicanas [63]; Flora de la costa de Oaxaca, México (2): Lista florística comentada del Parque Nacional Huatulco [64]; Recursos vegetales útiles en diez comunidades de la Sierra Madre del Sur, Oaxaca, México [23]; Home gardens sustain crop diversity and improve farm resilience in Candelaria Loxicha, Oaxaca, México [65]; Sistema agroforestal de los huertos familiares en la costa de Oaxaca, México [48]; and Sistemas agrosilvícolas de comunidades mixtecas and afromexicanas en la costa de Oaxaca, México [49], in addition to keys from the Flora de Guerrero and Flora de Veracruz. Species identifications were confirmed by comparing with specimens from the CHAP herbarium.

In Botanical Garden Tropicos [66], we reviewed the scientific names and compiled a full list of plants fund in the gardens including the family, genus, species, Spanish common name, Mixtec common name, use, life form, biogeographic origin, and degree of management.

We also compiled a list of the animals housed in the homegardens, with the species, genus, family, Spanish common name, Mixtec common name, and number of homegardens where it was found. The scientific names of the animals were listed in accordance with the Integrated Taxonomic Information System [67]. This listing included only (domesticated, feral, or wild) animal species that were intentionally kept in the homegardens. We did not perform a rigorous ecological sampling of wild, feral, or synanthropic animals that may occupy or pass through the homegardens, as that was outside the scope of our study.

2.6. Data Analysis

We systematized the information obtained from the interviews and calculated percentages using the following socioeconomic data: age, origin, language use, occupation, years of school attendance, marital status, number of family members, utilities in the home, and migration of relatives.

For the arrangement and components of the homegardens, we noted the name of the spaces where plants and animals were kept, components of the homegarden, reason for the arrangement of the components, and reason for the arrangement of the plants. For the vertical structure, we classified the species according to their life form as herbs, shrubs, trees or vines. For the horizontal arrangement, we described the different components of the homegardens and drew representative diagrams.

We compiled a list of plants that included the species, genus, Spanish common name, Mixtec common name, use (medicinal, edible, ornamental, ceremonial, lumber, shade, living fence, condiment, food wrapping, magical-religious, soil retention, or utensil), life form (vine, herb, shrubs, or tree), biogeographic origin (native, introduced, endemic, or cosmopolitan) and degree of management (cultivated, tolerated, protected, or encouraged).

We determined four categories of biogeographic origin for each plant species: native (originally distributed in Mexico, Central America, tropical America and/or Mesoamerica); introduced (originally distributed in South America or other continents); endemic (distributed only in Mexico); or cosmopolitan (found throughout the world). The degree of management was defined according to the descriptions provided by Casas et al. [68], Casas et al. [69], and Vásquez-Dávila [47] as cultivated (species in the process of domestication that receive management and care); tolerated (species that grow spontaneously in areas of anthropogenic vegetation and are allowed to remain without receiving any kind of management or care); protected (species that grow spontaneously within crop fields or gardens and receive direct care); or encouraged (species that grow spontaneously within crop fields or gardens and that receive only indirect care).

For the plant species, we calculated the first-degree non-parametric Jacknife alpha diversity index [70], according to the presence and absence of species in the homegardens, to obtain an estimate of the total species present in the homegardens of Santiago Tetepec.

S = Total number of species

L = Number of species present in a single sample

m = Total number of samples

We calculated the Sorensen beta diversity index [70] between all pairs of homegardens, using the presence and absence data of the plant species recorded in the 36 homegardens to quantify the degree of similarity among the flora of the homegardens and identify which gardens were most similar to each other. A value of 0 indicates no shared species between two gardens, while a value of 1 indicates identical species.

Sorensen formula:

a = Number of species present in garden A

b = Number of species present in garden B

c = Number of species present in both gardens

We described the management and agroforestry practices, the establishment of the homegarden, source of the plants, preparation of the land, cleaning of the garden, tools used, irrigation methods, use of fertilizers, disposal of plant and animal waste, sources and care of trees, presence of living fences, and arrival of wild animals. For cultural knowledge, we described the family member from whom the interviewee acquired their traditional knowledge with respect to the homegarden, contribution of the homegarden to nature conservation, importance of the homegarden, feelings generated by the homegarden, participation of the family members in activities related to the homegarden, interest of the children, increase or decrease of the space designated to the homegarden, magical and religious practices associated with the homegarden, and perceptions of animals related to the homegarden. The production of the garden was analyzed using bar graphs, and we analyzed the economic costs (purchase of plants, inputs, etc.), the benefits of the garden (food, health, income, etc.), time to harvest, destination of the harvest, and where the harvest is sold.

We used a multiple regression to evaluate whether the number of plant species in the homegardens is affected by the sociodemographic variables of age, years of school attendance, or language used (speaks Spanish and understands Mixtec (Ums) versus bilingual (Blg) or the area of the homegarden. We used a dummy variable for the linguistic competence and the reference was Blg. Prior to the analysis, the data were transformed using the Box–Cox method, and normality was confirmed with a Shapiro–Wilk test, which is recommended when sample size is below 50.

We performed a multiple correspondence analysis that included the identifier of each homegarden, the number of species, the sociodemographic variables, and the area to determine the association among them. The sociodemographic variables were categorized as follows: area categories in m2: 284 to 499—Small; 500 to 1000—Medium; >1000—Large. Age, in years: 18 to 39—Young; 40 to 60—Adult: >61—Senior. Linguistic competence: Speaks Spanish and understands Mixtec (Ums) or bilingual (Blg).

We performed an analysis of proportions on the biogeographic origin and degree of management to determine whether there was a difference between the categories of biogeographic origin and degree of management. We then performed pairwise comparisons, applying a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons with an adjusted alpha = 0.008. All statistical analyses were performed in R version 4.0.0 (Austria) [71,72].

3. Results

3.1. Socioeconomic Characteristics

The women in charge of homegardens in the community ranged in age from 18–71 years, with 50% aged 20–49 years and 41% aged 50–71. Eighty-nine percent of the women were originally from the community of Santiago Tetepec. Moreover, 69% of the women spoke Mixtec, 61% had completed all or part of primary school, and 83% had no occupation outside the home. The homes of the women all had electricity and running water, and 89% had a septic tank. Additionally, 69% of them had always lived in the community, 19% had emigrated in search of employment (mainly in Mexico City) and returned to the community, while 11% were from other community (Supplementary Materials). In the multiple regression analysis, none of the variables included (age, years of school attendance, linguistic competence, or garden size) had a significant effect on the number of species present in the gardens (Table 1).

Table 1.

Multiple regression analysis.

3.2. Arrangement and Composition of the Homegardens

The women distinguished the following spaces as different types of homegardens. Patios were characterized by an open space surrounded by medicinal, edible, and ornamental plants and fruit trees. Solares were defined by the presence of tall native trees used for shade. Jardines contained predominantly ornamental plants and sometimes grass. Huertos had predominantly edible tree (fruit trees), shrub, and herbaceous species.

3.3. Horizontal Arrangement

The main dwelling and patio components were found in all of the homegardens. The main dwelling is where the family generally rests and sleeps. It is characterized by walls made of wood, adobe or cinderblock; tiled, tin or concrete roof; and a corredor, which is a covered walkway around the house surrounded by a 50 cm tall half-wall to keep rainwater from splashing onto the house. In the patio there are trees, plants, and sometimes animals, and it commonly used as a space to dry the harvest of corn, beans, and hibiscus. In this space there is also a lavadero (wide, shallow elevated concrete sink with a washboard) and pileta (open water deposit, usually concrete in the form of a trough) under the shade of the trees, fuelwood piled and protected from the rain, and plants with different uses (Supplementary Materials).

The kitchen was separate from the main dwelling in 95% of the homegardens to prevent the health effects of inhaling the smoke generated by cooking with fuelwood. Generally, it was located alongside or across from the main dwelling. Kitchens were made of wood, bamboo, or adobe to keep them cool. The kitchen is used to prepare food and handmade tortillas. The bathroom in 83% of the homegardens was constructed across the patio, as far as possible from the main dwelling because it was connected to the septic tank. They were generally concrete and, in some cases, there was a tank or pileta for water storage. In some of the more recently built homes, the kitchen and bathroom were found inside the main dwelling.

There were chicken coops in 44% of the homegardens. Most were built with chain-link fence and housed hens and turkeys; in some cases, they contained trees or branches where the birds could roost. There were low, roofed pig pens referred to as chiqueros in 25% of the homegardens. These were surrounded with a brick or cinderblock wall up to one meter high and covered with a tin roof, away from the main dwelling and the kitchen.

In general, the ornamental plants were arranged by the type of flower or color, often in pots in front of the house or along the edges of the patio. The edible and medicinal plants were placed in a single location in front of the main dwelling, for easy access. Plants with spines were arranged along the edges of the patio, medium size trees surrounded the patio or were used as living fences and in some cases in the middle of the patio to provide shade. Large, old trees were beside or behind the house (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Different components of the homegardens of Santiago Tetepec, Oaxaca. (A) Conservation area beside the home with native trees. (B) Living fence with the species cacahuanano (Gliricidia sepium), nanche (Byrsonima crassifolia) and ciruelo (Spondias purpurea). (C) Fuelwood stacked at one end of the patio for use in the kitchen. (D) Arrangement of medicinal, ornamental, and condiment plants in the center of the patio. (E) Chicken coop used to enclose fowl and keep them from damaging the plants. (F) Space for the chickens to roost. (G) Pig pen or chiquero behind the house for housing swine. (H) Kitchen, built of bamboo. Photographs by Plácida López-Gallardo.

Sixty-nine percent of the women preferred to place plants around or along the outer perimeter of the patio to beautify their gardens and to have more space for fiestas de mayordomía (a traditional local celebration in which many neighbors are received at the home) and to keep dust from the street from entering the main dwelling. Thirty-one percent of the women preferred to have plants throughout the space rather than along the edges to prevent the fruit from being stolen or branches cut from outside the garden.

3.4. Vertical Structure

Thirty-five percent of the plant were herbs. The most frequently present herbs were basil (Ocimum basilicum), epazote (Dysphania ambrosioides), chili (Capsicum annuum), Mexican marigold (Tagetes erecta), and spearmint (Mentha spicata). Thirty percent were trees; the most frequently present were mango (Mangifera indica), jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus), almendro (Terminalia catappa), coconut (Cocos nucifera) and lime (Citrus × aurantiifolia). Twenty eight percent were shrubs and included hierba santa (Piper auritum), crown-of-thorns (Euphorbia milii), flor de clavito (Ixora coccinea), aloe (Aloe vera) and croto (Codiaeum variegatum). Seven percent were vines, such as flor de copa (Allamanda cathartica), yuva kaxi (Ipomoea sp.), beans (Phaseolus vulgaris), teléfono (Epipremnum aureum) and huaco (Aristolochia sp.).

3.5. Floristic Component

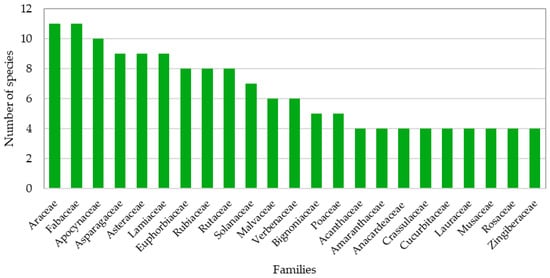

We identified 236 species of plants from 197 genera and 84 families (Appendix A). Of those, 212 have common names in Spanish and 121 have common names in Mixtec. The families with the most species were Araceae, Fabaceae, Apocynaceae, Asparagaceae, Asteraceae, and Lamiaceae. Araceae was represented by 11 species with ornamental and ceremonial uses, present in 14 homegardens. There were 11 species of Fabaceae, used for food, medicine, ornamentals, wood, and living fences, present in 27 homegardens. Apocynaceae was represented by 10 species with ornamental, ceremonial and medicinal uses, present in 27 homegardens. Asparagaceae had nine species with ornamental, ceremonial, medicinal and soil retention uses, present in 20 homegardens. Asteraceae was represented by nine species with ornamental, medicinal, ceremonial and magical-religious uses, present in 24 homegardens. Lamiaceae had nine species with medicinal, condiment, magical-religious, ornamental and ceremonial uses, present in 28 homegardens (Figure 4). The genus with the most species was Citrus with six species. The genera Plectranthus, Solanum and Musa were represented by four species each, and Annona, Agave, Dracaena, Kalanchoe, Persea and Hibiscus by three species each.

Figure 4.

Main botanical families present in the homegardens of Santiago Tetepec, Oaxaca.

Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum), spider lily (Crinum asiaticum), Mexican marigold (T. erecta), and cockscomb (Celosia argentea var. cristata) are used to decorate for all saint’s day. Banana leaf is used for wrapping tamales. Hierba santa (P. auritum), epazote (D. ambrosioides), oregano (Origanum vulgare), and avocado leaf (Persea americana var. drymifolia) are used to flavor dishes. Many flowers are used in posadas (traditional celebrations around Christmas), to decorate the church, to bring to the mayordomos (community member responsible for organizing the mayordomía) and for prayers. Plants are also donated to the school.

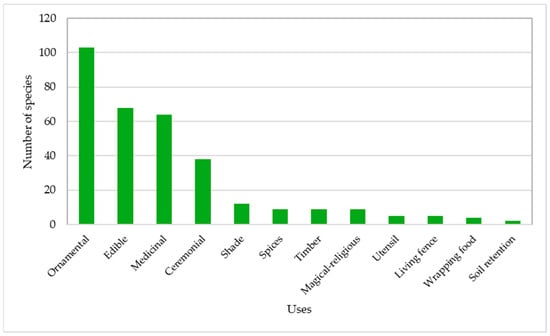

The biogeographic origin of the plants was 45.3% native (107 species), 52.5% introduced (124 species), 1.3% endemic (3 species) and 0.8% cosmopolitan (2 species). The proportion test showed that the distribution was not homogeneous across categories (χ2 = 218.9, p < 0.0001). All pairwise comparisons between categories were significant (p < 0.001 for all comparisons) except for native–introduced (χ2 = 2.17, p = 0.140) and endemic–cosmopolitan (χ2 = 0, p = 1). The degree of domestication was 78.4% cultivated (185 species), 15.7% protected (37 species), 2.5% encouraged (6 species) and 3.4% tolerated (8 species). The proportion test showed that plant species were not evenly distributed across management categories (χ2 = 492, p < 0.0001). All pairwise comparisons were significant (p < 0.001 for all comparisons) except encouraged–tolerated (χ2 = 0.07, p = 0.78). The most frequent uses of the plants were ornamental (103 species; 43.7%), edible (68 species; 28.9%) and medicinal (64 species; 27.1%), and 74 species had more than two use categories (Figure 5). The most common species in the homegardens were coconut (C. nucifera) in 22 gardens, mango (M. indica) in 22 gardens, hierba santa (P. auritum) in 22 gardens, jackfruit (A. heterophyllus) in 21 gardens, and crown-of-thorns (E. milii) in 21 gardens.

Figure 5.

Uses of the plants in the homegardens of Santiago Tetepec, Oaxaca.

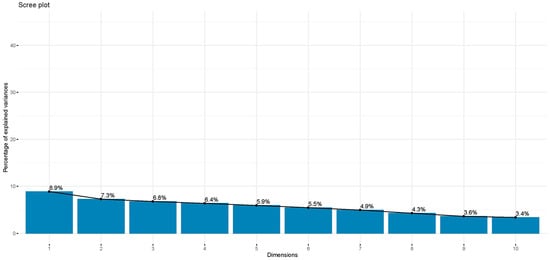

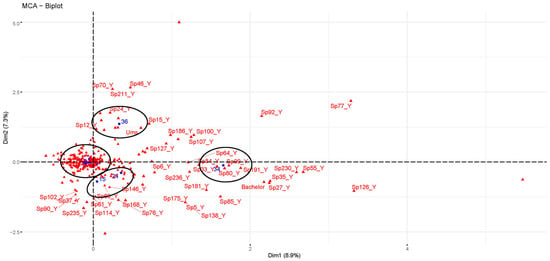

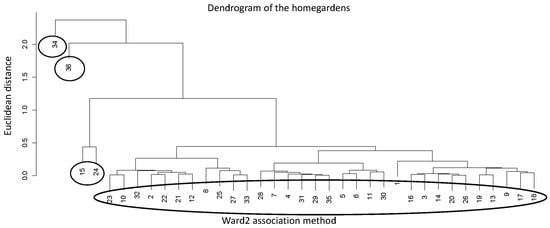

Figure 6 shows the percentage of variance explained by each dimension of the multiple correspondence analysis. The first two components explained very little of the total variance (8.9% and 7.3%, for a total of 16.2%). Figure 7 shows the spread of the homegardens sampled with respect to the first two dimensions. Gardens 34 and 36 are separated out as unique, in addition to a group comprising gardens 15 and 24, and, finally, a group formed by the rest of the gardens. This is clear in Figure 8, which shows the dendrogram built from the multiple correspondence analysis. Garden 34 is separated due to the presence of ornamental species.

Figure 6.

Graph of the percent variance explained by each dimension of the multiple correspondence analysis.

Figure 7.

Graph of the arrangement of the gardens and variables of the first two dimensions of the multiple correspondence analysis. The red triangle represents the plant species, the blue symbol indicates the number of each homegarden, and the black circle represent the associated groups of species and homegardens.

Figure 8.

Dendrogram showing four groups of homegardens.

The homegardens with the largest number of plant species were garden 24 with 69 species, garden 34 with 60 species, garden 36 with 60 species, garden 15 with 59 species and garden 1 with 53 species. Garden 17 was the one with the fewest species, with 11. Garden 34 had the most exclusive species, with 12, followed by garden 36 with 8 exclusive species and garden 15 with 7 exclusive species. For the first-order Jacknife diversity, we obtained an estimated total of 309 plant species present in the homegardens, which shows high agrobiodiversity among the homegardens. The pairwise similarity values ranged from 0.04 to 0.51 with a median of 0.25. With respect to the Sorensen beta diversity index for plant species, the gardens that had the highest similarity were gardens 3 and 28 with 0.513, gardens 5 and 24 with 0.460, gardens 4 and 5 with 0.456, and gardens 15 and 19 with 0.452. The gardens share similar edible species, with the majority of the gardens having coconut palms, mango trees, and hierba santa, and differing in the ornamental species they contained.

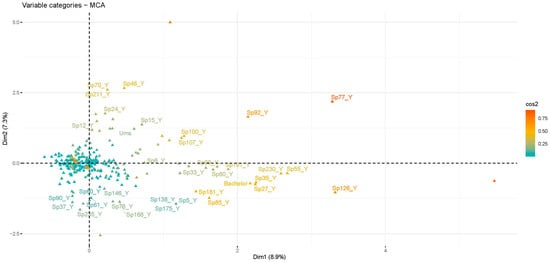

Figure 9 shows the sociodemographic variables or species that are best represented in the first two dimensions and influence the distributions of the gardens, for which we calculated the cosine squared for each variable. We observed that species 77 (Crossandra infundibuliformis—Ornamental), 126 (Jasminum multiflorum—Ornamental), 55 (Citrullus lanatus—Edible), 230 (Verbena hybrida—Ornamental), 35 (Begonia bracteosa—Ornamental), 27 (Aristolochia sp.—Medicinal), 92 (Dracaena sanderiana—Ornamental) and the bachelor degree had a greater influence on the representation of the gardens in the graph. Meanwhile, species 90 (Dioscorea bulbifera—Edible), 37 (Bursera simaruba—Timber), 235 (Zingiber officinale—Medicinal), nearly all of the other sociodemographic variables, and the area of the garden, were not as important. Of the sociodemographic variables, Ums had some influence on the distribution of the gardens. In fact, it is associated with garden 36 (Figure 7). The gardens were concentrated near zero and, of the 68 edible species, 60 were concentrated close to the gardens and are more related among each other due to edible species such as banana (Musa acuminata), mango (Mangifera indica), icaco (Chrysobalanus icaco), nopal (Opuntia ficus-indica), etc. The species with other uses, ornamentals, and medicinals were located far from the majority of the gardens.

Figure 9.

Cosine squared graph showing the variables that are best represented by the first two multiple correspondence analysis dimensions, with red points further from zero having more influence and blue points closer to zero having less influence.

3.6. Animals

We recorded 15 species of animals from 15 genera and 13 families that were intentionally kept in the homegardens. Fifteen have Spanish common names and 10 have common names in Mixtec (Appendix A). Of these, 12 were domestic species and 3 were captive wild species. Geese, doves, guinea pigs, ducks, goats, and donkeys were relatively infrequent in the homegardens.

There was some variation in the housing of chickens (including hens and roosters) and turkeys among homegardens. In some gardens they were loose in the garden with a log to roost; in others they were housed in enclosures, either at night or all the time, to keep them from damaging or consuming edible plants. Dogs were generally left loose, though some were tied up in the patio. Cat, geese and ducks were always loose. Rabbits, parakeets, guinea pigs, and doves were kept in cages. Cows, donkeys, and goats were tied up, while pigs were enclosed in pig pens (chiqueros) and turtles were in a tub or container with water (Supplementary Materials).

3.7. Management of the Garden and Agroforestry Practices

The establishment of the garden consists of acquiring and preparing the land; when there is “monte” (referring to spiny scrub, agaves and cactus) present, it is cleared, while naturally growing useful trees are left and additional plants are sown/planted and established. In some cases, the plants present had already been planted by the interviewees’ in-laws or grandparents, such as soursop trees (Annona muricata), cuajinicuil (Inga inicuil), icaco (Chrysobalanus icaco), mango (M. indica) and jícara (Crescentia cujete).

Family members and neighbors in the community or other towns gift vegetative parts of plants such as flor de muñeca (Cordyline fruticosa), epazote (D. ambrosioides), crown-of-thorns (E. milii), huichicata (Xanthosoma sagittifolium), capricho (Plectranthus scutellarioides), basil (O. basilicum) and banana (Musa sp.). Other plants are purchased for their flowers, such as flor de clavito (I. coccinea), cola de camarón (Pachystachys lutea), aloe (A. vera), rose (Rosa chinensis), spider lily (Crinum asiaticum) and teléfono (E. aureum). Sometimes plants are purchased, such as cacao (Theobroma cacao), cuajinicuil (Inga inicuil), anona (Annona cherimola), orange (Citrus x sinensis), starfruit (Averrhoa carambola), jackfruit (A. heterophyllus) and coconut palm (C. nucifera). Other species are obtained from seeds that are sorted and stored to be sown during the rainy season, such as squash (Cucurbita moschata), Mexican marigold (T. erecta), corn (Zea mays), bean (P. vulgaris), cucumber (Cucumis sativus), watermelon (Citrullus lanatus), cockscomb (Celosia argentea var. cristata), chili (C. annuum) and sesame (Sesamum indicum). Seeds from fruits that are consumed are also thrown out onto the land and, if they germinate, the seedlings are transplanted.

Plant species such as basil (O. basilicum), spearmint (M. spicata), oregano (Origanum vulgare) and candor (Lippia alba) are propagated vegetatively and placed in pots, tins, jugs, or buckets with soil and compost. Species including capricho (P. scutellarioides) and roses (R. chinensis) are planted directly in the ground, and “pacholes” (germination trays) are made with repurposed dishes or bags with soil and compost for species such as chicozapote (Manilkara zapota), almendro (T. catappa), avocado (Persea americana), starfruit (A. carambola), jackfruit (A. heterophyllus), guava (Melicoccus oliviformis), anona (A. cherimola), cuajinicuil (I. inicuil), soursop (A. muricata), and tamarind (Tamarindus indica).

Other trees are propagated with stakes, such as the cacahuanano (Gliricidia sepium) and ciruelos (Spondias spp.). Others germinate from seeds dispersed by animals such as bats, or by wind, such as the seeds of the macuil (Tabebuia rosea). Species including epazote (D. ambrosioides), corn (Z. mays), bean (P. vulgaris), Mexican marigold (T. erecta), squash (C. moschata) and chili (C. annuum) are sown directly in ground that was previously prepared with compost. The compost used is decomposing leaves (ñutavi, abono de tierra negra) from adjacent forest or on the owners’ land that is transported with wheelbarrows or in sacks by car, manure of animals such as cows, chickens, and goats, lime, mud from the river, eggshells, fruit peels, ash, or fertilizer for corn fields. In some cases, insecticides are used to eliminate leafcutter ants.

During the rainy season, species such as chepil (Crotalaria longirostrata), hierba mora (Solanum americanum), and medicinal plants including hierba vieja (Datura innoxia) are germinated. Other plants are extracted from natural areas, such as hierba de zorrillo (Petiveria alliacea), hierba de la gangrena (Tournefortia hartwegiana), berenjena (Solanum torvum) and huaco (Aristolochia sp.), all of which are used medicinally.

During the dry season, plants are watered daily, if water is available. Some gardens are watered every third day, which is when water is pumped into the water system or is acquired from wells, rivers, and streams. In extreme cases, water can be purchased to fill 1000 L storage tanks. Sometimes plants die due to lack of water. Plants are watered with jícaras (small bowls made from the fruit of C. cujete), buckets, or hoses. Trees are completely cut back or some branches are removed, which are later used as fuelwood. Dead leaves are removed from some species such as bananas (Musa spp.). Insecticides are applied to some species such as tamarind (T. indica) to protect against leafcutter ants.

Gardens are weeded by hand, with machetes, or with tarecua and yata (types of hoes). Sometimes, chickens are allowed to eat weeds, and herbicide use was also recorded. The leaves that fall off of the trees are swept with brooms or raked. Sometimes, tree leaves are deposited in a particular place to be composted with organic waste, and sometimes they are burned, and, if there is not sufficient space available, they can be thrown into a ravine, brought to crop fields, or disposed of as trash to a garbage truck. The tools used in the gardens include shovels, machetes, brooms, rakes, knives, wheelbarrows, pruning shears, jugs, buckets, drums, trowels, loppers, and pry bars, as well as traditional local tools, including the coa, tarecua, and yata.

The wildlife mentioned by the interviewees as present in the homegardens included geckos (Hemidactylus frenatus), mice (Mus musculus), squirrels (Sciurus aureogaster), bobcats (Lynx rufus), opossums (Didelphis marsupialis), turtles (Rhinoclemmys pulcherrima), skunks (Mephitis macroura), armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus), coatis (Nasua narica), rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus), iguanas (Iguana iguana), snakes (Colubridae), grackles (Quiscalus mexicanus), doves (Streptopelia decaocto), finches (Haemorhous mexicanus), swallows (Hirundinidae), jays (Calocitta Formosa), woodpeckers (Dryobates scalaris), parakeets (Eupsittula canicularis), orioles (Icterus pectoralis, Icterus pustulatus), quails (Colinus virginianus), hawks (Accipitridae), eagles (Accipitridae), ants (Formicidae), pollinators including butterflies (Lepidoptera), hummingbirds (Trochilidae), and domestic animals such as cats (Felis catus) and dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) of neighbors.

3.8. Cultural Value

Knowledge of cultivating and taking care of plants and animals was transmitted by both parents in 27.78% of the cases of the women interviewed. Another 25% mentioned that they learned from their mothers only, 8.33% from their grandmothers, 11.11% from their husbands and in-laws, and 27.78% that they learned by themselves. They also mentioned learning from observing and repeating what other women do in their gardens.

They considered that having a homegarden helps to conserve nature: “Los árboles mitigan el calor por la sombra, producen oxígeno, refrescan el hogar, limpia el aire por lo que mejora la salud, son atrayentes de lluvias…entre más arboles hay más agua en los ríos” (Trans.: “The trees mitigate the heat with their shade, they produce oxygen, they refresh the home, they clean the air, so they improve our health, they attract rain…the more trees there are, the more water in the rivers”). In addition, “las plantas se ocupan para todo” (Trans.: “the plants are used for everything”), so they prefer to have plenty of plants and plant fruit trees that, in addition to shade, provide fruit. They consider that they should plant more plants and trees because “el planeta se está acabando por la tala de árboles” (Trans.: “The planet is dying because the trees are being cut down”), in addition to perceiving increasing temperatures during the warm seasons.

Gardens are considered important because they harbor useful species of plants and animals. The trees provide shade and edible fruits; they contain edible wild plants such as hierba mora and chepiles and cultivated ones including nopales (Opuntia ficus-indica), chilies (C. annuum), and beans (P. valgaris). They provide meat and eggs to consume in the family or to sell. They produce flowers to take to events, funerals, or the cemetery. There are ornamental plants to beautify the home, while the patio is a space for recreation and rest. The possession of a garden is associated with happiness, tranquility, beauty, nostalgia, pleasure, and love for plants. It is associated with decreased expenses, since families do not have to buy products at stores.

In general, all members of the family participate in activities to maintain the homegarden; the children help to sweep and pick up fallen leaves, water the plants, sow plants, and feed the animals, and husbands help mainly with trimming trees and weeding. In 58.33% of the homes interviewed, there were children, all of whom were interested in the care and helping with the activities of the homegarden. In 88.89% of the homegardens, the size of the garden has remained the same, in 5.56% it has become larger, and in 5.56% it has become smaller, depending on the dry season or increase in the size of the river.

Fifty percent of the homegardens had associated magical–religious practices. The interviewees mentioned planting basil (O. basilicum), rue (R. graveolens), lengua de suegra (Sansevieria trifasciata), aloe (A. vera), pino (Polyscias fruticosa), ruda de monte (Adenophyllum aurantium), cacahuanano (G. sepium), and hierba de zorrillo (P. alliacea) to ward off culture-bound syndromes such as mal de ojo, envidia, and malas vibras. Sometimes a bow is tied on them to ward off mal de ojo and for good luck, protection, and abundance. Leaves of lime (Citrus limettioides), basil (O. basilicum), rue (R. graveolens) and candor (L. alba) are also used for spiritual cleansing to remove mal de ojo. There are also specific beliefs surrounding planting, including several surrounding the influence of the moon. For example, it is believed that planting coconut palm (C. nucifera) when the moon is out at 2 or 3 am will make the palm bear fruit sooner; that sowing corn (Z. mays) when the moon is waxing will ensure a better harvest; and that ornamentals should be planted under a full moon so that they will flower. Inhabitants also speak to the fruit trees, telling them that, if they do not flower, they will be cut down. Older people believe that trees such as avocado (P. americana) should be struck with a machete so that they continue to bear fruit.

3.9. Homegarden Production

In 63.89% of the homegardens, there have been expenses related to buying plants. In 19.44%, they hire workers to trim large trees, apply liquid fertilizer (once a month, every two months or once a year), or plant fruit trees. In 11.11%, they spend on inputs such as compost, fertilizer, or insecticides. In 5.56%, they buy water. In 27.78% of the homegardens, the interviewees reported that there were no economic expenses.

In 88.89% of the homegardens, the family reported benefitting from food from the garden, such as fruit, vegetables, condiments, and greens (quelites). In 42% of the homegardens, they reported benefits to well-being due to shade, recreation space, plants, and food. In 38.89%, they received health benefits from access to medicinal plants such as estafiate (Artemisia ludoviciana) prepared as a tea to treat stomachache, indigestion, inflammation, “coraje” (anger and discomfort caused by an argument or gossip) and “latido” (a pulsing sensation near the navel); huele de noche (Cestrum nocturnum) for fever; tea of tender shoots of vaporub (Plectranthus hadiensis) for cough and colds, baths with lengua de vaca (Critonia quadrangularis) for fever and cough, among many others. Nearly 14% reported benefits to their family economy because they do not have to spend to buy food, and a smaller percentage due to the profits from selling products from their gardens.

The frequency of harvest from homegardens was distributed as follows: 61.11% reported harvesting once a year from fruits such as ciruela (Spondias purpurea), anona (A. cherimola), mamey (Pouteria sapota), chicozapote (M. zapota), almendro (T. catappa), mango (M. indica), jícara (C. cujete), coffee (Coffea arabica) and guava (P. guajava); 5.56% reported two harvests per year of fruits such as guava (P. guajava) and bitter lime (C. x aurantiifolia); 2.77% harvested every two months, such as jackfruit (A. heterophyllus); 2.77% once per month, such as banana (Musa spp.); 11.11% occasionally, such as hierba mora (S. americanum) and anona (A. cherimola); 5.56% nearly all the time, such as banana (Musa spp.), sugarcane (S. officinarum), and soursop (A. muricata); and 11.11% all the time, such as starfruit (A. carambola), lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus), coconut (C. nucifera), icaco (C. icaco) and nopal (O. ficus-indica).

In 80.56% of the homegardens, the products harvested are consumed by the family. In 63%, they are given away, and, in 38.89%, they are sold. Seasonal edible plants include corn (Zea mays), beans (Phaseolus vulgaris), chili (Capsicum annuum), squash (Cucurbita moschata), chepiles (Crotalaria longirostrata), hierba mora (Solanum americanum), yuva kaxi (Ipomoea sp.), and ciruelas (Spondias ssp.); and those that are available year-round include nopales (Opuntia ficus-indica), bananas (musa spp.), coconut (C. nucifera), starfruit (A. carambola) and icaco (Chrysobalanus icaco). These plants are supplemented with those harvested from the milpas, including corn (Z. mays), beans (P. vulgaris), and squash (C. moschata). Furthermore, there are few shops, and people only infrequently buy food. Dishes that are prepared include ciruelas or squash in syrup, squash soup, stewed nopales, boiled quelites, salsas, boiled beans, egg prepared in different ways, and tortillas, as well as drinks prepared with seasonal fruits.

They give away chepiles (C. longirostrata), nopal (O. ficus-indica), and leaves of hierba santa (P. auritum); branches of rue (R. graveolens), oregano (O. vulgare) and basil (Ocimum basilicum); and fruits such as mango (M. indica), banana (Musa spp.), coconut (C. nucifera) and anona (A. cherimola). Nearly 65% of sales are within the community and 35.71% are to other communities. For sale in the community, they offer caprichos (P. scutellarioides) for candles, some ornamental plants for prayer rituals, banana leaves (Musa spp.), avocado leaves (P. americana var. drymifolia), seasonal fruits such as mangoes (M. indica), bananas (Musa spp.), and limes (A. x aurantiifolia), as well as eggs, chickens, and pigs. Hibiscus (Hibiscus sabdariffa) and sesame (Sesamum indicum) are sold in Pinotepa, and mango (M. indica) and coconut (C. nucifera) to other communities.

4. Discussion

4.1. Socioeconomic Characteristics

Women are in charge of the management of the homegardens, and more than two thirds of them (69.44%) are between the ages of 40 and 69 years old. The most diverse gardens in the community belonged to women over 40 years old who share their household with younger married couples. This is similar to findings in other states in Mexico, where women over 40 have a central role in conserving spaces that generate and harbor agrobiodiversity and traditional knowledge [13,73,74]. The participation of women in the family garden has also been widely observed in other regions [35,75,76], especially where women are charged with feeding the family and spend the most time within the home [13].

In the community of Santiago Tetepec, it is women who are in charge of the care and management of the family garden, performing activities such as weeding, watering, and planting edible and medicinal species, as well as the activities of the home and preparing food and tortillas. The women of the community decide which plants to sow in accordance with knowledge acquired from both of their parents or their mothers only. Women are the ones who transmit knowledge to their children, such as which edible plants are most consumed and which medicinal plants are used for which symptoms and ailments. As such, women contribute to the conservation and permanence of traditional knowledge [35,77]. While women perform these activities with the help of their children, men perform activities such as pruning trees and fencing the garden. This has also been documented in several other regions, where men and women perform different activities within the homegarden [25,29,39].

The multiple regression analysis showed no effect of the variables of age, educational attainment, language use, or garden size on the number of species. This is contrary to the cases documented in other studies, where factors such as gender, occupation, and educational attainment affected the number of species [24,43,44,78]. For example, in communities in Mexico, small homegardens showed complex and diverse physiognomy [34]. Meanwhile, in northeastern India, the diversity of plants and productivity of homegardens depended strongly on the size of the homegarden [79], and, in southeastern Ethiopia, the practices and size of the homegarden had a significant positive effect on the composition of plant species [80].

This could indicate that the studied group shares knowledge. This could be because it is a small community, which may result in a more dynamic exchange of knowledge. This is similar to a study of two communities in Serbia [81], which showed that small communities are important reservoirs of ethnobotanical knowledge. A similar conclusion could be reached from the results of the multiple correspondence analysis, since the arrangement of the gardens was found close to a value of zero on both dimensions, in addition to the fact that the percentage variance explained was very low.

4.2. Arrangement and Plant Species Richness in Homegardens

The most common name given to the homegarden is patio or solar, as reported by Moreno-Calles and collaborators [7] in the state of Oaxaca. The components of the homegardens follow the same general scheme as homegardens on the coast of Oaxaca indicated by Méndez-Pérez [48], who mentioned the main dwelling, patio, kitchen, bathroom, and chicken coop. An additional feature in our study was the pig pen (chiquero), which was present in most of the homegardens in the community.

We observed that the most recently constructed homegardens had changed their arrangement, including the kitchen and bathroom within the main dwelling, replacing adobe with concrete as the main construction material, and, in a few cases, introducing grass, converting the homegardens into something more akin to a yard.

The vertical structure of 35% herbs, 30% trees, 28% shrubs and 7% vines is similar to other data obtained in the region [82,83]. With respect to diversity, the 236 plant species, 197 genera, and 84 families we recorded in the Mixtec gardens demonstrate higher floristic diversity than the communities of other regions of Oaxaca, such as the Sierra Sur, Valles Centrales, Sierra Norte and Sierra Mazateca [6,65,75,76]. The diversity is also higher than that recorded in communities in other states in the country, such as Guerrero (129 species [84], Chiapas (209 species) [85], or Veracruz [86]. However, Maya gardens presented a similar or higher number of species, reporting 212–387 species in Yucatán [26,42] and 96–369 species in Campeche [40,41]. This floristic diversity is high compared to that recorded in other regions of the world, such as the 108 species recorded in Indonesia, 145 in Bulgaria, 36 in Ethiopia, and 87 in South Africa [17,18,27,28].

The botanical families with the highest number of species are Araceae, Fabaceae and Apocynaceae. This differs from data obtained by Méndez-Pérez [48] in the coastal region of Oaxaca, where are the most representative families are Anacardiaceae, Solanaceae and Annonaceae, and where Araceae was not recorded, Fabaceae had only seven species and Apocynaceae had only two species. Our findings are more similar to those obtained in the southeast of the state of Morelos by Tegoma-Coloreano [83], where the most representative families were Fabaceae, Araceae and Asparagaceae.

The biogeographic origin of the plants was 45% native and 53% introduced. Other study found a higher number of native species than introduced species [34,84]. However, Gómez-Pompa [87] and Olvera [29] mention that many of these introduced plants now have new uses and indigenous names and have been adopted, selected, and improved. This is reflected in some plants in the community, such as the orange tukua china (C. x sinensis), capricho ita tɨkɨndɨ (P. scutellarioides), and tamarind yutu ndokuva (T. indica), among others. Fruit trees such as the jackfruit and noni do not have names in Mixtec, as these were only recently introduced due to their medicinal and beneficial health properties.

With respect to the degree of domestication, most plants (78%) are cultivated and the rest were protected, encouraged, and tolerated. This is similar to other regions [58], as is the fact that there was a moderate degree of similarity among individual homegardens in terms of the plant species they contained [84].

The homegardens are similar; the differences among homegardens were due mainly to differences in the large number of ornamental plants, while edible plants were similar. In the community, the most frequent use recorded was ornamental, followed by edible and medicinal. This contrasts with some other regions where the highest number of species is edible [17,18,48], though, in others, higher numbers of ornamental species have been recorded [83,84]. The prevalence of ornamentals that we recorded in the community is likely because most families have other plots where they cultivate agricultural crops such as corn or that they use for raising livestock, and many of the edible plants they use are established on those plots rather than in the homegardens.

4.3. Food Security and Self-Sufficiency

Although ornamental species outnumbered other uses, there were 68 species of edible plants. The family gardens are more closely related to each other due to 60 edible species, such as banana (Musa acuminata), mango (Mangifera indica), icaco (Chrysobalanus icaco), and nopal (Opuntia ficus-indica). This indicated food resilience at the community level, and that the people share similar foods. In addition, in 80.56% of the homegardens, the products harvested are consumed by the family, such that homegardens guarantee food self-sufficiency and food security in the community.

The economy of the community is local and the source of their food is homegardens, since the resident do not have access to many shops. Community members sell and give away many foods, including chepiles, nopales, and fruits, and they sell chickens and eggs, such that families depend directly on their homegardens and harvest from their milpas to buffer against periods of food scarcity. The homegardens of Santiago Tetepec are sources of foods such as fruits, chepiles, sweet potatoes, nopales, beans, condiments, tomatoes, chilies, squash, corn and hibiscus, which are the most consumed foods in the community.

Many of these are provided, at least partially, by the homegardens, supplementing the foods families acquire from their crops, livestock, and purchased from stores or markets. In addition to edible plants, all of the homegardens provided complementary foods of animal origin, such as eggs and poultry. Indeed, chickens were the most common animal (69.44%) in the homegardens of the community of Santiago Tetepec, as in many communities in Mexico [32,39,86]. This supports the family’s food needs and contributes to food security and self-sufficiency in the community.

The harvest from the homegardens is used for family consumption, gifting, or sale, in the same order of importance as was reported in different sites [39,82,86]. The sale of seasonal fruits and of animals translates into extra income that can be used to buy other necessary goods. As such, the homegardens are of great importance for the economies of the families of the community.

In the coastal region, Santiago Tetepec is one of the communities where the Mixtec language is still used and learned by children. However, it is perceived that some families are incentivized to use Spanish. This could lead to the loss of their language and knowledge of their place of origin, the Mixtec cosmovision, and knowledge of the use of the plants present in the community. In addition, some young people emigrate in search of employment in other states. As stated by Cano [84], migration leads to changing roles, changes in the family dynamic, and loss of customs and knowledge of culture. In this case, it leads to the abandonment of rural areas, leaving older people to continue with the labor of the homegardens and cultivating their land. Even so, the homes in the community are food self-sufficient and conserve traditional knowledge. Women continue to be the ones who can transmit their knowledge to their children at early ages [12,20].

5. Conclusions

The homegardens of coastal regions are sustainable and diverse, with 236 documented species of plants and 15 species of animals with different uses. The ornamental, edible, and medicinal uses had the highest number of species. The arrangement of the homegardens includes a main dwelling, patio, kitchen, bathroom, chicken coop, and pig pen. The gardens provide the residents diverse plant and animal foods, and, together with the plots where they establish milpas (traditional corn-bean-squash polycultures) or livestock, it is their main source of food. Homegardens therefore contribute to food security and self-sufficiency in the community. The homegardens were mostly related to each other by 60 edible species. The homegardens also contribute to the conservation of culture and traditional knowledge of the agroforestry practices and management that is performed in them. Women have a particularly central role in caring for and managing these spaces.

In the multiple regression analysis, none of the variables had a significant effect on the number of species present in the garden. In the multiple correspondence analysis, there was no statistical significance of any of the sociodemographic variables. Women showed uniformity in their knowledge and in the variety of plants they keep in their homegardens. Future research should focus on the plant cover within homegardens, a more detailed evaluation of the role of the homegardens in the family economy, ecosystem services, and adaptation to climate change, as well as studies of the fauna in the gardens and the amounts harvested and dishes prepared with each plant.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18010394/s1, Table S1: Socioeconomic data of the women interviewed (n = 36); Table S2: Homegarden pairs presenting the highest values of the Sorensen similarity index, a. species in the first garden, b. species in the second garden, c. species present in both gardens; Figure S1: Homegarden 8; Figure S2: Homegarden 9; Figure S3: Homegarden 13; Figure S4: Homegarden 25; Figure S5: Homegarden 26; Figure S6: Plants used as condiments (with English, Spanish, and/or Mixtec common names and scientific name); Figure S7: Medicinal Plants (with English, Spanish, and/or Mixtec common names and scientific name); Figure S8: Edible Plants (with English, Spanish, and/or Mixtec common names and scientific name); Figure S9: Ornamental and Ceremonial Plants (with English, Spanish, and/or Mixtec common names and scientific name); Figure S10: Fruit Trees (with English, Spanish, and/or Mixtec common names and scientific name); Figure S11: Plants with other uses; Figure S12: Animals in homegardens.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.V.L.-G. and M.P.-N.; methodology, P.V.L.-G. and M.P.-N.; formal analysis, P.V.L.-G., A.S.-V., M.P.-N. and I.A.-T.; investigation, P.V.L.-G., A.d.l.R.-G. and O.J.-V.; resources, A.d.l.R.-G., O.J.-V. and V.E.C.C.; data curation, P.V.L.-G. and M.P.-N.; writing—original draft preparation, P.V.L.-G.; writing—review and editing, M.P.-N., J.A.G.V.-C., A.S.-V., I.A.-T., A.d.l.R.-G., O.J.-V. and V.E.C.C.; supervision, M.P.-N., J.A.G.V.-C. and I.A.-T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is waived for ethical review by Chapingo Autonomous University, Division of Forest Sciences. Due to the research involving only anonymous questionnaires with oral consent, which is exempt from ethics review under the institution’s current policies.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the population of Santiago Tetepec for sharing their knowledge, beliefs, traditions and laughter. Pérez-Nicolás received a postdoctoral fellowshipfrom Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of useful species recorded in homegardens. Use: M = Medicinal, E = edible, O = Ornamental, C = Ceremonial, L = Lumber, S = Shade, F = Living Fence, D = Condiment, W = Food wrapping, R = Magical-religious, T = Soil retention, U = Utensil. LF = Life form: T = Trees, S = Shrubs, H = Herbs, V = Vines. BO = Biogeographic Origin: I = Introduced, N = Native, E = Endemic, C = Cosmopolitan. DM = Degree of management: C = Cultivated, P = Protected, E = Encouraged, T = Tolerated.

Table A1.

List of useful species recorded in homegardens. Use: M = Medicinal, E = edible, O = Ornamental, C = Ceremonial, L = Lumber, S = Shade, F = Living Fence, D = Condiment, W = Food wrapping, R = Magical-religious, T = Soil retention, U = Utensil. LF = Life form: T = Trees, S = Shrubs, H = Herbs, V = Vines. BO = Biogeographic Origin: I = Introduced, N = Native, E = Endemic, C = Cosmopolitan. DM = Degree of management: C = Cultivated, P = Protected, E = Encouraged, T = Tolerated.

| Num. | Family | Genus | Specie | Spanish Common Name | Mixtec Common Name | Use | LF | BO | DM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acanthaceae | Crossandra | Crossandra infundibuliformis (L.) Nees | O | H | I | C | ||

| 2 | Acanthaceae | Megaskepasma | Megaskepasma erythrochlamys Lindau | Antorcha, cabezona | O, C | S | I | C | |

| 3 | Acanthaceae | Pachystachys | Pachystachys lutea Nees | Cola de camarón | O, C | S | I | C | |

| 4 | Acanthaceae | Ruellia | Ruellia simplex C. Wright | O | H | N | T | ||

| 5 | Amaranthaceae | Alternanthera | Alternanthera brasiliana (L.) Kuntze | Sangre de cristo | Neñereño | O, C | H | N | T |

| 6 | Amaranthaceae | Celosia | Celosia argentea var. cristata (L.) Kuntze | Cresta de gallo, Santa Teresa | Ita lo’o, ita xini loo | O, C | H | I | C |

| 7 | Amaranthaceae | Disphania | Dysphania ambrosioides (L.) Mosyakin & Clemants | Epazote | Mino, mino chatu | D, M | H | N | C |

| 8 | Amaranthaceae | Gomphrena | Gomphrena globosa L. | Olotillo | Ita sañɨ | O, C | H | N | P |

| 9 | Amaryllidaceae | Crinum | Crinum asiaticum L. | Flor blanca | Ita kuichi | O, C | H | I | C |

| 10 | Amaryllidaceae | Hippeastrum | Hippeastrum puniceum (Lam.) Voss | Azucena, orquídea | O, C | H | I | C | |

| 11 | Anacardeaceae | Amphipterygium | Amphipterygium adstringens (Schltdl.) Standl. | Cuachalala | M | T | E | E | |

| 12 | Anacardeaceae | Mangifera | Mangifera indica L. | Mango | Mangu, yutu mangu | E, M | T | I | C |

| 13 | Anacardeaceae | Spondias | Spondias mombin L. | Ciruela amarilla, ciruela naranja | Tɨkava kuan | E | T | N | C |

| 14 | Anacardeaceae | Spondias | Spondias purpurea L. | Ciruela ahumada, ciruela roja | Tɨkava ñu’umaa, Tɨkava isu, tikava kuaa | E, M, F | T | N | C |

| 15 | Annonaceae | Annona | Annona cherimola Mill. | Anona, nona | Ndoko | E, S | T | N | C |

| 16 | Annonaceae | Annona | Annona reticulata L. | Anona roja o morada | Ndoko kua’a | E, S | T | N | C |

| 17 | Annonaceae | Annona | Annona muricata L. | Guanábana, guanabo | Ndokoo iñu | E, M, S | T | N | C |

| 18 | Apiaceae | Eryngium | Eryngium foetidum L. | Cilantro, cilantro casero | D | H | N | P | |

| 19 | Apocynaceae | Adenium | Adenium obesum (Forssk.) Roem. & Schult. | Flor del desierto | O | S | I | C | |

| 20 | Apocynaceae | Allamanda | Allamanda cathartica L. | Flor de copa, copa de oro | O | V | I | C | |

| 21 | Apocynaceae | Catharanthus | Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don. | Paragüita, teresita | Ita sombrilla, ita uva | O, M | H | I | C |

| 22 | Apocynaceae | Cryptostegia | Cryptostegia grandiflora R. Br. | O | V | I | C | ||

| 23 | Apocynaceae | Huernia | Huernia schneideriana A. Berger | Cactus | O | H | I | C | |

| 24 | Apocynaceae | Nerium | Nerium oleander L. | Chamizo, clavel | O, C | S | I | C | |

| 25 | Apocynaceae | Plumeria | Plumeria rubra L. | Flor de mayo, cacaloxochitl | Ita ti’ita | O, C | T | N | C |

| 26 | Apocynaceae | Plumeria | Plumeria pudica Jacq. | Ramo de novia | O | S | I | C | |

| 27 | Apocynaceae | Stapelia | Stapelia gigantea N.E. Br. | Flor de estrella | O | H | I | C | |

| 28 | Apocynaceae | Tabernaemontana | Tabernaemontana divaricata (L.) R. Br. ex Roem. & Schult. | Bertha | Ita | C | S | I | C |

| 29 | Araceae | Aglaonema | Aglaonema commutatum Schott | Huichicata | O | H | I | C | |

| 30 | Araceae | Anthurium | Anthurium andraeanum Linden | Anturio | C | H | I | C | |

| 31 | Araceae | Caladium | Caladium bicolor (Aiton) Vent. | Huichicata | Da’kata | O | H | N | C |

| 32 | Araceae | Colocasia | Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott | Camote | Ñami ndyoko | E | H | I | C |

| 33 | Araceae | Dieffenbachia | Dieffenbachia seguine (Jacq.) Schott | O | S | N | C | ||

| 34 | Araceae | Epipremnum | Epipremnum aureum (Linden & André) G.S. Bunting | Teléfono | O | V | I | C | |

| 35 | Araceae | Monstera | Monstera adansonii Schott | Esqueleto | O | V | N | C | |

| 36 | Araceae | Spathiphyllum | Spathiphyllum wallisii Regel | Cuna de Moisés | O | H | N | C | |

| 37 | Araceae | Xanthosoma | Xanthosoma sagittifolium (L.) Schott | Huichicata | Vixikata | W | H | N | C |

| 38 | Araceae | Xanthosoma | Xanthosoma violaceum Schott | Huichicata | Daa vixi | O | H | N | T |

| 39 | Araceae | Zamioculcas | Zamioculcas zamiifolia (Lodd.) Engl. | O | H | I | C | ||

| 40 | Araliaceae | Dendropanax | Dendropanax arboreus (L.) Decne. & Planch. | Palo de mano | U | T | N | C | |

| 41 | Araliaceae | Polyscias | Polyscias balfouriana (André) L.H. Bailey | O | S | I | T | ||

| 42 | Araliaceae | Polyscias | Polyscias fruticosa (L.) Harms | Pino | O, C, R | S | I | C | |

| 43 | Araucariaceae | Araucaria | Araucaria heterophylla (Salisb.) Franco | Pino | O | T | I | C | |

| 44 | Arecaceae | Acrocomia | Acrocomia aculeata (Jacq.) Lodd. ex Mart. | Coyul de monte | Tɨkachi | E | T | N | P |

| 45 | Arecaceae | Cocos | Cocos nucifera L. | Palma de coco, coco | Tɨka’a, ndɨka’a | E | T | I | C |

| 46 | Arecaceae | Dypsis | Dypsis lutescens (H. Wendl.) Beentje & J. Dransf. | Palma areca, palmilla | O, U | T | I | C | |

| 47 | Aristolochiaceae | Aristolochia | Aristolochia sp. | Huaco | Yukutakiyoo | M, R | V | N | P |

| 48 | Asparagaceae | Agave | Agave desmetiana Jacobi | Maguey | O | S | N | C | |

| 49 | Asparagaceae | Agave | Agave tequilana F.A.C. Weber | M | S | N | C | ||

| 50 | Asparagaceae | Agave | Agave angustifolia Haw. | Maguey | O | S | N | C | |

| 51 | Asparagaceae | Beaucarnea | Beaucarnea recurvata Lem. | Pata de elefante | O | S | E | C | |

| 52 | Asparagaceae | Chlorophytum | Chlorophytum comosum (Thunb.) Jacques | Lazo de amor | O | H | I | C | |

| 53 | Asparagaceae | Cordyline | Cordyline fruticosa (L.) A. Chev. | Flor de muñeca | O, C | S | I | C | |

| 54 | Asparagaceae | Dracaena | Dracaena fragrans (L.) Ker Gawl. | Palo de brasil | O | S | I | C | |

| 55 | Asparagaceae | Dracaena | Dracaena sanderiana Sander ex Mast | Cañita, carrizo | O | S | I | C | |

| 56 | Asparagaceae | Sansevieria | Sansevieria trifasciata Prain | Lengua de suegra | Yavi | O, C, T | H | I | C |

| 57 | Asphodelaceae | Aloe | Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f. | Sábila | Yavi | M | S | I | C |

| 58 | Asteraceae | Adenophyllum | Adenophyllum aurantium (L.) Strother | Ruda de monte | Yuku kaya | M, R | H | N | P |

| 59 | Asteraceae | Artemisia | Artemisia absinthium L. | Hierba maestra | Yuku uva | M | H | I | C |

| 60 | Asteraceae | Artemisia | Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt. | Estafiate | Yuuku uva | M | H | N | C |

| 61 | Asteraceae | Chrysanthemum | Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat. | Margarita | O, C | H | I | C | |

| 62 | Asteraceae | Critonia | Critonia quadrangularis (DC.) R.M. King & H. Rob. | Lengua de vaca | Ita viyo | M | S | N | P |

| 63 | Asteraceae | Montanoa | Montanoa grandiflora DC. | Artemisa | ita kuichi | O, C | S | N | C |

| 64 | Asteraceae | Porophyllum | Porophyllum ruderale (Jacq.) Cass. | Papalo quelite | Yuvakoli | M | H | N | P |

| 65 | Asteraceae | Tagetes | Tagetes erecta L. | Cempasúchitl | Ita kuan | O, C, M | H | N | C |

| 66 | Asteraceae | Zinnia | Zinnia elegans Jacq. | Girasoles de colores | Ita | O, C | H | N | C |

| 67 | Balsaminaceae | Impatiens | Impatiens balsamina L. | Flor de china | O | H | I | C | |

| 68 | Begoniaceae | Begonia | Begonia bracteosa A. DC. | Flor de corazón, corazon de cristo | O | H | I | C | |

| 69 | Bignoniaceae | Crescentia | Crescentia cujete L. | Jícara | Yutu ñachinda’a | M, U | T | N | C |

| 70 | Bignoniaceae | Parmentiera | Parmentiera aculeata (Kunth) Seem. | Cuajilote | Tyitya’anda | M | T | N | C |

| 71 | Bignoniaceae | Podranea | Podranea ricasoliana (Tanfani) Sprague | O | V | I | C | ||

| 72 | Bignoniaceae | Tabebuia | Tabebuia rosea (Bertol.) DC. | Macuil, macuil del monte | Tɨkundyi | S, L | T | N | P |

| 73 | Bignoniaceae | Tecoma | Tecoma stans (L.) Juss. ex Kunth | Flor de San José, Santa María, San Pedro | Ndɨkaki, Ndɨkayi | M | T | N | P |

| 74 | Bromeliaceae | Ananas | Ananas comosus (L.) Merr. | Piña | Vichi | E | H | N | C |

| 75 | Burseraceae | Bursera | Bursera simaruba (L.) Sarg. | Palo mulato | Yutundiya | S, F | T | N | P |

| 76 | Cactaceae | Acanthocereus | Acanthocereus tetragonus (L.) Hummelinck | Nopal estrella | Vinyaa iñu | E | S | N | C |

| 77 | Cactaceae | Opuntia | Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mili. | Nopal | Vinyaa, viitya | E | S | N | C |

| 78 | Cactaceae | Pereskia | Pereskia aculeata Mill. | Uña de gato | M | V | I | C | |

| 79 | Calophyllaceae | Calophyllum | Calophyllum brasiliense Cambess. | Tigrillo | Diyo | L | T | N | P |

| 80 | Cannaceae | Canna | Canna indica L. | O | H | N | C | ||

| 81 | Caricaceae | Carica | Carica papaya L. | Papaya | Yutu ndapapaya | E | T | N | C |

| 82 | Chrysobalanaceae | Chrysobalanus | Chrysobalanus icaco L. | Ciruela de mar, icaco blanco, morado | Tɨtkava chañu’u | E, S | T | N | C |

| 83 | Chrysobalanaceae | Couepia | Couepia polyandra (Kunth) Rose | Frailecillo | Yica sañɨɨ | E | T | N | P |

| 84 | Chrysobalanaceae | Licania | Licania platypus (Hemsl.) Fritsch | Zapote cabezón | Yica tini yoo | E | T | N | P |

| 85 | Cleomaceae | Cleome | Cleome houtteana Schltdl. | Flor de Oaxaca | O | H | I | C | |

| 86 | Combretaceae | Terminalia | Terminalia catappa L. | Almendro, árbol de almendra | Ntɨka lamendra, nyika lamendra | E, M, S | T | I | C |

| 87 | Commelinaceae | Tradescantia | Tradescantia pallida (Rose) D.R. Hunt | O | H | E | C | ||

| 88 | Commelinaceae | Tradescantia | Tradescantia zebrina Bosse | Siempre viva | Dɨɨ | M | H | N | C |

| 89 | Convolvulaceae | Ipomoea | Ipomoea sp. | Yuva kaxi | E | V | N | P | |

| 90 | Cordiaceae | Cordia | Cordia alliodora (Ruiz & Pav.) Oken | Hormiguillo | L | T | N | E | |

| 91 | Crassulaceae | Echeveria | Echeveria gigantea Rose & Purpus | Oreja de elefante | M | H | N | C | |

| 92 | Crassulaceae | Kalanchoe | Kalanchoe blossfeldiana Poelln. | O | H | I | C | ||

| 93 | Crassulaceae | Kalanchoe | Kalanchoe x houghtonii D.B. Ward | Da’a coco | M | H | I | C | |

| 94 | Crassulaceae | Kalanchoe | Kalanchoe pinnata (Lam.) Pers. | Siempre viva | M | H | I | C | |