Abstract

Communication and writing skills are critical for employability and leadership in sustainability and STEM fields, but few studies examine how interdisciplinary, problem-based learning (PBL) environments foster these competencies amongst undergraduates. This three-year study examined how human resource management (HRM) and Chemistry students collaborated on Sustainable Development Goal (SDG)-themed projects within a Global Classroom model. We used LIWC-22, a validated text analysis tool to assess students’ written reflections about their discipline-specific PBL exercises (e.g., debates about UBI) and their SDG-focused inter-disciplinary group projects (e.g., vaccine access). We found that the HRM students (n = 84) demonstrated increased use of curiosity and cognition language during in-person and synchronous collaboration contexts. Chemistry students collaborating synchronously with their HRM teammates exhibited enhanced curiosity in their writing, though findings for this group are tentative due to the small sample size. Our findings suggest that both discipline-specific and SDG-focused interdisciplinary PBL activities can improve undergraduates’ metacognitive skills and their curiosity, which are critical for addressing sustainability challenges. Our Global Classroom offers a scalable model of how SDG-focused PBL activities can be used to create collaborations between STEM and management undergraduates and enable them to develop context-specific solutions for global sustainability challenges while improving their communication and writing.

1. Introduction

There has been a growing emphasis on adopting innovative pedagogical approaches that better equip students to tackle complex global sustainability challenges like food insecurity, vaccine access, and soil and water pollution. Traditional teacher-centered methodologies are seen as insufficient for cultivating the skills needed to address these pressing issues [1,2,3]. Educators and employers alike now recognize the importance of developing student skills in interdisciplinary collaboration, communication, critical thinking, and data literacy—collectively known as essential soft skills [4,5]. However, many employers still perceive that graduates lack the key competencies needed for contemporary workplaces [6,7]. A recent review of experiential learning in sustainability education finds that existing published studies lack robust measurement and assessment of workforce-relevant ‘soft skills’ that employers seek—like communication [8].

Recent research shows that important gaps persist in the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) curriculum itself. For example, a comprehensive 2025 review of 60 articles [9] highlighted that most published studies continue to focus on higher education and are concentrated in Asia and Europe, while research conducted in the Global South is markedly lacking. Even when SDG-relevant competencies—like collaborative problem solving or engineering for sustainability—are addressed in academic programs, this review suggests these efforts often lack systematic long-term evaluation of student outcomes and robust implementation. Such blind spots reinforce the urgent need for rigorous, interdisciplinary pedagogical research—such as the current study—that directly measures practical skill gains and real-world engagement with sustainability challenges [8,9]. Furthermore, few studies in this rapidly expanding literature rigorously explain why innovative, interdisciplinary approaches drive measurable improvements in students’ writing—particularly for higher-order thinking, reflection, and curiosity—across multiple attempts and cohorts [8,9].

To fill this gap, we conducted a three-year Global Classroom intervention in which human resource management (HRM) and chemistry students collaborated virtually and in-person to solve problems that address United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs). We embedded structured writing tasks for HRM and chemistry students throughout the semester and analyzed textual outcomes with validated LLM linguistic tools [10]. Our design enables detailed comparison of delivery context and collaboration mode—where some cohorts collaborated asynchronously, providing rare multi-cohort and multi-modal evidence on learning, teamwork, and written communication development [9,10].

The writing and communication skill gains documented here not only address academic competencies but also support students’ capacity to transfer their skills to sustainability problems in the workplace, as called for in a recent review [8]. By systematically tracking these changes across successive cohorts in an interdisciplinary learning environment, our empirical study offers actionable models for educators to foster employability and real-world impact in contemporary sustainability education [8,9].

1.1. Global Classroom

The Global Classroom [11] enhances learning through interdisciplinary collaboration, experiential learning, and practical applications addressing global issues (e.g., sustainable farming). The first iteration of the Global Classroom—started during the COVID-19 pandemic, was delivered virtually and synchronously. It was offered in an in-person and synchronous format in the second and third years. The Chemistry course, an independent supervised research study course, was offered in both asynchronous and synchronous formats during these three years.

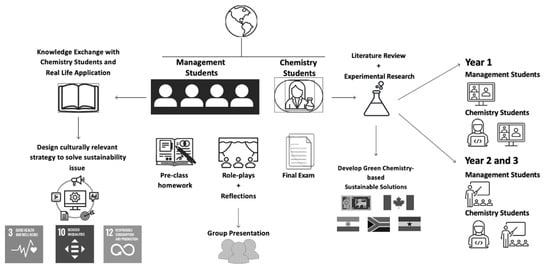

In the first year, the interdisciplinary group projects addressed global healthcare—increasing COVID-19 vaccination rates in countries of the Global South. While sustainability—food security and environmental pollution—were the central themes in the second and third years. The overall structure of the Global Classroom initiative, including the integration of synchronous and asynchronous instructional modes and the interdisciplinary collaboration between HRM and chemistry students, is illustrated in Figure 1. The Global Classroom model supports the assessment of sustainability competencies through students’ written reflections and project deliverables. In all three years, around the mid-point of the semester, HRM and chemistry students formed interdisciplinary teams and participated in a workshop or went on a field trip related to the topic of the SDG-focused project for that cohort (In Year 1, the inter-disciplinary team building launch and stress management workshop was virtual and synchronous for HRM and chemistry students).

Figure 1.

The Global Classroom model outlines interdisciplinary collaboration between HRM and chemistry students. In Year 1 (due to COVID-19), the HRM course was delivered virtually in synchronous mode; in Years 2 and 3, it was delivered in-person and synchronously. The chemistry course was offered in both synchronous and asynchronous formats across all three years. The arrows illustrate the sequence of activities completed by students in the HRM and Chemistry courses, including pre-session plans, post-session reflections, experimental research, knowledge exchange activities, and final presentations. The figure indicates the topics of the SDG group projects completed in the three years while the country’s flags denote the regions of focus for the SDG projects.

1.1.1. Experience of Chemistry Students in the Global Classroom

For chemistry students, the Global Classroom experience consisted of three distinct phases. In the initial phase, they were introduced to SDG-focused problems, such as inequitable vaccine access during the COVID-19 pandemic (SDG 3), food insecurity (SDG 2), or water pollution (SDG 6). They then embarked on a comprehensive literature review and reviewed existing empirical data to gain a well-rounded insight into the complexities surrounding these SDG-focused challenges. This foundational research phase was crucial for chemistry students in order for them to grasp the global significance of the problem at hand, as well as the scientific principles and concepts relevant to chemistry.

In the second phase, the chemistry students presented their research in five-minute modules to the HRM students, who would in turn form country- and crop- (or drug) specific teams to find solutions to the SDG-focused challenges the Chemistry students had researched. To facilitate their interdisciplinary collaborations, we took the HRM and chemistry students on a topic-relevant field trip or workshop that provided real-world context to the challenge they were investigating that year. These experiential learning opportunities were instrumental in helping HRM and chemistry students consolidate their knowledge. Through the practical knowledge they gained from the workshop or field trip and through the team building experiences they gained from jointly attending them, these experiential learning opportunities enabled the students to better formulate and refine their proposed questions. For example, when visiting a local organic farm, the chemistry and HRM students learned the practical constraints of maintaining an organic farm while being surrounded by farms that used harmful synthetic pesticides.

For the final phase of the project, both the HRM and chemistry students researched and articulated discipline-specific methodologies to address the SDG-focused problem. Students from both disciplines crafted detailed plans for their approaches and shared their findings with each other. Such sharing occurred through structured sessions, synchronously allowing for real-time discussion and feedback. For example, HRM student teams presented their country- and crop-specific research on the supply and availability of pomegranate in India.

Chemistry students who were working asynchronously in a semester first reviewed the research theses and reflections written by the chemistry students who had collaborated with the HRM students in the previous semester. They also viewed the presentations made by the HRM students. Then, these chemistry students continued adding to the literature and experimental research on that topic. For example, research conducted by the cohort of chemistry students on using coffee for hydrogels (Year 2) was expanded by a later cohort to test the viability of grapefruit skin as a hydrogel (Year 3). Such types of asynchronous collaborations between chemistry and HRM students enabled flexibility in how and when the chemistry students could learn, integrate, and conduct their research while maintaining continuity to the Global Classroom initiative. Such asynchronous collaboration opportunities promoted the conducting and accumulating of chemistry research on the topic when the HRM course was not offered in that semester, thus allowing for a continuation of the inter-disciplinary approach at solving the SDG-focused problem.

1.1.2. Experience of HRM Students in the Global Classroom

For HRM students, the Global Classroom comprised two phases. First, they participated in weekly PBL activities to learn about core concepts in labor relations. These labor-relations-focused PBL activities were created to foster the skills they needed for the SDG-focused interdisciplinary group project. For example, in the first labor-relations-focused PBL activity, students brainstormed in teams and identified different types of barriers (e.g., physical, virtual, visual, auditory, etc.) that limit people’s accessibility to different types of environments (e.g., public transit, universities, libraries, schools, etc.). Through this activity, the HRM students cultivated perspective-taking, learned to pinpoint how and why barriers are created, and gained a deeper appreciation for the complexity and nuances of the different locations and stakeholders who use them. In subsequent labor-relations-focused PBL activities, teams of students engaged in negotiation and arbitration role-play cases set in the healthcare and agricultural context. In such exercises, the HRM students were assigned to prepare ahead for different roles in the negotiation or arbitration cases (e.g., of an employee, a union steward, a union lawyer, an arbitrator, a supervisor, or the lawyer for the management side). Student teams switched perspectives across the negotiations and arbitration role-play cases. For example, for the negotiation case, one team would take the role of the management side while in the arbitration case they would take the role of the union. By switching their roles of union vs. management perspectives across cases and engaging in negotiation and arbitration role plays, the HRM students honed their perspective-taking skills while simultaneously developing their argumentation skills—ultimately improving their critical thinking and communication skills.

Such labor-relations-focused PBL activities helped the HRM student teams to collaborate with chemistry students on an SDG-focused interdisciplinary problem and develop appropriate solutions. HRM students were able to draw on their perspective and knowledge of different stakeholders in a labor-relations context (e.g., farmers, under-represented groups) and develop empathy while recommending training initiatives and governmental policies for those most affected by such initiatives. In doing so, the HRM students developed innovative strategies that directly accounted for and overcame these challenges. Furthermore, these labor-relations-focused PBL activities help HRM students become effective communicators, empowering them to make the most of their interdisciplinary collaboration with the chemistry students.

In the second phase, HRM students collaborated on an SDG-focused problem as described earlier. Their primary role involved developing country- and crop- or drug-specific HRM strategies using the research provided by chemistry students. For example, in one year, students collaboratively addressed water pollution caused by synthetic pesticides. Chemistry students researched creating hydrogels from local crops (e.g., coffee, seaweed, and pomegranate) to purify contaminated water. They then presented their research to the HRM students, who in turn conducted country- and crop-specific labor-relations research. For example, they developed and presented policy, training, or educational interventions targeted for these crops in different countries (e.g., India, Canada) that would promote sustainable agriculture of these crops to supply the raw materials for these hydrogels. The HRM and chemistry students maintained regular communication to ensure technical accuracy of their understanding and the feasibility of their proposed strategies.

1.2. Synchronous vs. Asynchronous Collaboration Between Chemistry and HRM Students

The course delivery modes depicted in Figure 1 allowed us to examine how synchronous versus asynchronous collaboration environments impact student writing. As depicted in Figure 1, the chemistry course within the Global Classroom was offered in both synchronous and asynchronous formats, providing a unique opportunity to examine how these modalities of collaboration between Chemistry and HRM students influence student curiosity and cognition.

Recent scholarship highlights that the collaboration modality—whether synchronous or asynchronous—significantly impacts students’ engagement and learning outcomes [12]. Synchronous collaboration environments enable immediate feedback and enhanced social presence, fostering student confidence, and reflective dialogue [13]. Conversely, asynchronous collaboration environments may support task completion and structural consistency, yet often with reduced depth in metacognitive engagement [14]. These findings are consistent with collaborative cognitive load theory, suggesting that shared, real-time interactions facilitate higher order thinking by distributing cognitive effort across peers [15]. Fostering metacognitive reflection through purposeful writing, pauses, and self-questioning is crucial for more profound, analytical, and insightful learning [16].

By enabling HRM and chemistry students to collaborate and address concrete sustainability challenges, the Global Classroom model effectively integrates social scaffolding and iterative reasoning emphasized by these theoretical frameworks, thereby helping students develop writing voices grounded in both evidence and empathy.

1.3. Problem-Based Learning

An important aspect of the Global Classroom is that the first half of the course is focused on helping HRM students develop the necessary communication and perspective-taking skills they need to collaborate with chemistry students on the SDG-focused interdisciplinary project. To do this, we used multiple, labor-relations-focused PBL exercises and integrated them with writing development frameworks [17] and used validated pedagogical methods [18] to achieve this goal.

Problem-based learning (PBL) flips the traditional teaching approach on its head—turning students from passive learners to active learners. It is similar in approach to experiential learning, work-integrated learning, active-blended learning, gamification, community-engaged, and project-based learning [3,19,20,21]. Such pedagogical approaches empower students to take control of their learning by experimenting—through trial and error. For example, in the field of medicine [22,23], PBL is used as an “instructional (and curricular) learner-centered approach that empowers learners to conduct research, integrate theory and practice, and apply knowledge and skills to develop a viable solution to a defined problem” [24]. Compared to traditional classroom teaching, PBL in management courses [25,26] can increase student satisfaction with their learning, improve the quality of their reflections from their learning, improve teamwork skills, and help them develop transferable skills for the workplace [27,28].

Despite the benefits that PBL provides, it is not without its limitations. Research suggests that educators can have difficulties in ensuring adequate scaffolding for their students and motivating them to be active learners [29]. It is difficult to motivate students to fully engage in PBL activities when they do not fully understand what they are supposed to learn from such activities [30]. To overcome such motivational issues with PBL activities, it is important to ensure that students understand how the PBL activities they are engaging in are relevant to them [31,32]. To circumvent these pitfalls of PBL learning, we designed the labor-relations-focused PBL exercises to be personally relevant to the students and provided adequate scaffolding. For example, the “identifying barriers” exercise described earlier required students to identify accessibility issues at various buildings on the university campus, and in the city’s local transit system. Further, before engaging in the PBL activity, HRM students first reviewed the textbook chapter readings, prepared a memo to discuss in class and used that memo to complete the labor-relations-focused PBL exercise with other HRM classmates during the session, and participated in a guided debrief discussion. This pedagogical process ensures HRM students have the background, practice, and reflection needed for effective knowledge acquisition. These steps ensured that the HRM students acquired the relevant and important labor-relations knowledge and skills they needed to maximize their benefits from collaborating on the SDG-focused interdisciplinary project and developing their writing and communication competencies in that context.

1.4. Using Relevance and Interdisciplinary Collaboration to Improve Writing

As with any skill, improving writing requires practice [33] and self-reflection [17,34]. Yet, in the age of generative AI, students may be even less motivated to practice writing than ever before. Our study addressed the question of how educators can improve such communication skills that are highly sought after by employers. Research shows that an important aspect of increasing student motivation to improve their writing is to demonstrate the relevance of the writing material for students [35,36]. Relevance can be established by relating the HRM course activities to local issues (e.g., accessibility of buildings), everyday applications (e.g., Women’s march), and current global crisis (e.g., food insecurity crisis; [37]). In the Global Classroom, to engage students in reflective writing, we established the relevance to both HRM and chemistry students in a number of ways. First, for HRM students, we created labor-relations-focused PBL exercises that were relevant to students’ careers and the local issues the city was facing (e.g., identifying accessibility issues at the university and the city transit system). We then broadened the relevance of the issues beyond that of their city to more locations in the global South—e.g., Sri Lanka, India. We engaged them on SDG-focused issues such as problems with traditional farming practices (e.g., use of synthetic pesticides leading to soil and water pollution) and the need to implement sustainable practices to ensure sustainable farming and thus reducing food insecurity. In this way, we created an SDG-focused problem that required HRM students to collaborate with chemistry students to solve it. To further motivate and engage the students in the project, students were given the choice of which crops they wanted to research as well as which country they wanted to investigate the issue in. HRM students typically picked crop and country combinations that were related to their diasporic country of origin (e.g., India, Sri Lanka, Canada, Ghana), making it more relevant to them. For chemistry students, relevance was created for them by having them conduct research on a crop (e.g., coffee, seaweed) they were interested in and presenting their findings to the HRM students.

All students were required to reflect and write about their experiences in the discipline-specific PBL activities they engaged in throughout the semester. HRM students had to prepare for and reflect on their labor-relations-focused PBL activities (e.g., debates on Universal Basic Income) that they completed throughout the semester. Meanwhile, chemistry students had to write bi-weekly reflections on the progress of their primary literature research, their experimental work, their thesis, and their collaborations with HRM students. At the same time the HRM and chemistry students had many opportunities to communicate with each—during the 5-min science presentations, the group project launch day when teams were formed, during the field trip, during virtual synchronous meetings, and through chats or email messages. Together, all these activities helped them improve their communication and writing skills while they collaborated on their SDG-focused interdisciplinary group project.

1.5. Theoretical Framework

This study draws on two complementary models of writing development: Hillocks’ [38] inquiry-based framework and Kellogg’s [17] cognitive model of writing. Hillocks’ model emphasizes the importance of sustained inquiry, explicit framing of writing tasks, and the strategic use of social scaffolds. In this view, writing is best developed through structured opportunities for students to explore authentic problems, receive feedback, and iteratively revise their thinking in response to evidence and discussion. This approach aligns closely with the design of both the HRM and chemistry courses, where assignments are grounded in socially relevant issues and scaffolded across time.

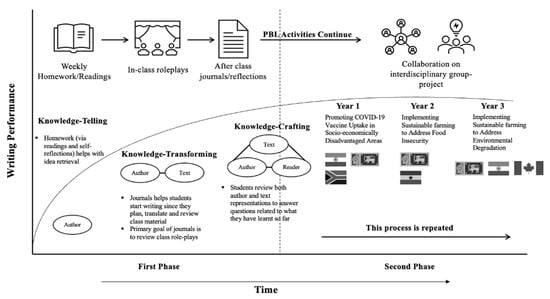

Kellogg’s [17] model extends this by focusing on the cognitive processes involved in writing—planning, translating, and reviewing—and how these processes are strengthened through verbal interaction with peers during the experiential exercise that they are to write about and oral debriefing with instructors and classmates after the exercise. In an earlier empirical study [39], we applied this model (see Figure 2) to demonstrate how management students develop stronger analytical and metacognitive language when they talk through complex ideas (like creating joint value in the famous Ugli Orange negotiation exercise). This problem-based interactive and experiential learning by talking to peers supports students in developing their communication skills and promotes the articulation of nuanced, critical perspectives in writing.

Figure 2.

An illustration of how writing about a concept (e.g., effectiveness of UBI) and talking about it in a debate with fellow students enables students to go from “telling” about their knowledge of a concept to “transforming” their understanding of that concept, and finally to “crafting” their communication about it because of their increased awareness of the audience they are writing to about it [18]. The country’s flags denote the regions for which the SDG projects were developed.

Together, these frameworks support our investigation into how interdisciplinary, problem-based, and experiential learning environments help HRM and chemistry students develop transferable communication skills, thinking, and the desire to obtain new knowledge—analyzed here through Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC-22; [10]) linguistic markers such as cognition (thinking) and curiosity (interest in new knowledge or experiences).

We chose to investigate language that reflects cognition because it reflects features of good communication skills (i.e., to be able to clearly articulate what you are thinking about, to others). Language that reflects curiosity was also chosen because it reflected the experiential learning elements of the Global Classroom course. We predicted that, through the new experiences garnered from engaging in the labor-relations-focused PBL activities and the SDG-focused global and interdisciplinary group-project, the HRM students would become increasingly curious. By conducting primary literature research on the crop or drug of their choice, and by communicating with and collaborating with HRM students, while reflecting on all these experiences as they progress on their thesis, this would make chemistry students more curious.

Furthermore, from a curricular perspective, it also builds on the interdisciplinary pedagogical principles outlined in Radhakrishnan, Thavarajah, and Romain [11], which highlight the value of global classroom models, lived experience, and reflective assessment in shaping inclusive and socially responsive learning outcomes. We used LIWC-22 [10] metrics to assess the presence of thinking and interest in obtaining new knowledge or experiences.

1.6. Purpose and Research Questions

Building upon Hillocks’ [38] inquiry-based framework and Kellogg’s [17] cognitive model of writing, we explore:

- How do course-level relevant PBL activities (e.g., for the HRM and chemistry students) impact writing metrics that reflect cognition and curiosity?

- Does collaboration mode (synchronous vs. asynchronous for chemistry students) and instructional mode (virtual synchronous vs. in person for HRM students—Year 1 vs. Years 2 and 3) matter in shaping students’ use of language that reflects thinking and curiosity?

We describe and compare how the interdisciplinary collaboration unfolds—including group processes, role assignments, and modes of interaction—across synchronous and asynchronous, virtual, and in-person settings.

2. Materials and Methods

We collected data from three cohorts of HRM, and chemistry undergraduates enrolled in the Global Classroom over 3 years. Such cohort data serves as the foundation for analyzing the representation of different disciplines of students and to evaluate the impact of our project. At the end of every semester, the cohort of students were asked if their course work could be used for research purposes. They were assured that the instructors would not know of their consent, that their data would only be analyzed after final grades were submitted, and that there would be no negative consequences to them regardless of whether or not they consented to the use of their course work for this project. We report data of students who consent. This study was approved by the University Research Ethics Board approval (IRB: 00035602). All data, analytic pipelines, and computational code (R scripts for statistical analysis, LIWC-22 custom dictionaries) are available from the corresponding author via an open-access repository. There are no data sharing restrictions. No new materials or protocols outside of those described below were used.

2.1. Participants

Across three years of the Global Classroom, there were a total of 84 HRM students enrolled in a 3rd year required HR course on Labor Relations and 13 Chemistry students enrolled in an elective 2nd year supervised independent research study course. Year 1 consisted of 15 HRM students and 3 Chemistry students; in Year 2, there were 36 HRM students and 5 Chemistry students; in Year 3, 33 HRM students and 5 Chemistry students. The majority of the HRM students across the 3 years identified as women (65–89%) and East-Asian (27–61%) or South-Asian (33–45%). Demographic details for each cohort, including self-reported ethnicity for HRM students, and predicted ethnicity for Chemistry students, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic composition of each cohort 1.

2.2. Procedure

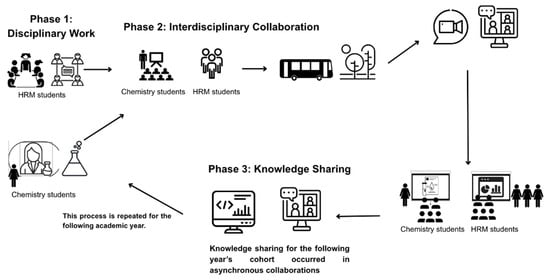

The Global Classroom was delivered in three consecutive cohorts: Year 1 (virtual for both HRM and Chemistry), Years 2–3 (in-person). The HRM cohort was always synchronous when virtual or face-to-face when in-person. Meanwhile, chemistry students enrolled synchronously with the HRM students or enrolled asynchronously depending on the cohort, described below (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

HRM and chemistry students engage in parallel discipline-specific PBL at the start of the semester, form interdisciplinary SDG project teams at mid-semester, participate jointly in experiential activities, and make final presentations in teams (HRM) and as individuals (chemistry). Arrows show the temporal progression from Phase 1 (disciplinary work) → Phase 2 (team formation and collaboration via literature search and experimental research) → Phase 3 (joint knowledge sharing through presentations to stakeholders), with the process repeating annually for subsequent cohorts addressing new sustainability challenges.

HRM Course. In each of the 3 years, HRM students engaged in scaffolded labor-relations-focused PBL activities, all of which required them to write a preparatory memo before engaging with their classmates. The first one consisted of brainstorming discussions on accessibility barriers, followed by a preparatory memo exercise on what unions should do to involve youth in them. A third writing exercise was to write a 1-page memo on the role of the Women’s March (or the Million-man March) on the Labor Relations movement or vice versa. The fourth exercise was to prepare for and against a debate on the effectiveness of governmental policies like Universal Basic Income.

During each session, the professor introduced key labor relations concepts (e.g., governmental initiatives on equity), followed by the PBL exercise (e.g., a debate on the effectiveness of Free University Tuition) and a class discussion afterward. Figure 2 illustrates the process of how HRM students wrote and engaged with each other in their writing. We report the results of the 4 PBL activities in which students had to write about something (i.e., identifying barriers to accessibility, how youth can be engaged in unions, The role of Women’s March in the Labor Relations movement, The effectiveness of equitable governmental initiatives like universal basic income and free university tuition) and give their reflections of these activities in their term exam (a reflective, open-book, open-notes exam on the labor-relations-focused PBL activities they did throughout the course and about their collaborations with the chemistry students). These learning and writing activities were designed to teach HRM students the key concepts in labor relations while giving them the skills needed for collaborating with chemistry students and taking the perspective of the stakeholders engaged in the SDG-focused problem (see Figure 2).

As seen in Figure 3, midway through the 12-week semester, the professor introduced the HRM students to the Global Classroom approach by identifying the SDG-focused problem (e.g., food insecurity, vaccine access) for that cohort. The HRM students were reminded of the usefulness of participating in such a project—as an interdisciplinary and global project; it was meant to simulate modern-day human-resource management contexts requiring them to collaborate with a peer in STEM. At this point, their STEM peers for the cohort (chemistry students who were enrolled in a supervised research study course with the chemistry professor) delivered a short, 5-min oral presentation about their research so far on the SDG-focused problem (e.g., mitigating food insecurity through cultivating seaweed and using it as a decontaminant) for that cohort.

The HRM students then formed country- and crop- (or drug- and country-) specific teams to develop solutions to these SDG-focused problems for local and international community stakeholders engaged in solving them. For example, one team focused on developing training programs for farmers in Sri Lanka on how to use hydrogels developed with seaweed to decontaminate polluted water. The HRM student teams simultaneously continued developing their perspective taking and communication skills by writing about, planning, and participating in negotiation and arbitration role-play exercises (see Figure 2) set in the agriculture and health sectors.

The HRM students’ teams along with their chemistry peers then went on a field trip to a farm or attended a workshop together (see Figure 3). Such structured, experiential and problem-based learning opportunities to collaborate with each other enabled the HRM and chemistry students to build good interdisciplinary teams while learning about the practicalities of the SDG-focused issue for that cohort (e.g., the problem of maintaining an eco-system for organic farms). These interdisciplinary HRM and chemistry student teams further met as needed throughout the rest of the semester to clarify their understanding of the scientific knowledge and the research findings about the crop. For instance, during the collaborative farm field trip, chemistry students served as subject-matter experts, discussing the relevance of their research on their crop, while HRM students conducted stakeholder interviews to make appropriate policy change vs. stakeholder training recommendations. The teams of HRM students also met with the chemistry students to discuss the relevance of their HRM research in solving the SDG-focused problem for that cohort and take the stakeholder perspective. This sequence of collaboration is mapped in Figure 3. This sequence allowed the HRM students to understand the complexity of the SDG-focused problem they were dealing with and to develop accurate tools while recommending broader country- and crop-specific solutions (e.g., how and where to grow seaweed in India) to solve the SDG-focused problem (e.g., of water pollution). In the last class of the semester, these HRM students then made a 15-min team presentation to the Global Classroom, which included their HRM and chemistry peers for that cohort. The recordings of these HRM team presentations were then made available to the next cohort of chemistry students to conduct literature research or primary experimental work on the next cohort’s SDG-focused problem (see Figure 3).

Chemistry Course. The chemistry students were supervised individually to conduct literature or experimental research on the SDG-focused problem while enrolled in a Supervised Research study course. Each chemistry student collaborated with one or more HRM student teams either synchronously or asynchronously. As seen in Figure 3, Phase 2 of the semester—the interdisciplinary collaboration—started with chemistry students making a short, 5-min research presentation to the HRM students. The chemistry students then participated in interdisciplinary team building PBL activities by going on a field trip to an organic farm with them or cooking with them in a culinary workshop (see Figure 3). These chemistry students also met with the HRM students in real time as needed and communicated with each other via emails or virtual synchronous meetings (on MS-Teams or Zoom). The chemistry students then made their final thesis presentations to a panel of chemistry professors, separate from the chemistry professor supervising their independent research for this interdisciplinary SDG-focused project.

All throughout, and at the end of the semester, these chemistry students wrote reflections about their independent research study and the interdisciplinary group project with the HRM students. Finally, the chemistry students submitted a written thesis summarizing the outcome of their literature and experimental research. We used these writings for our text-based analysis.

As seen in Figure 1, in Year 1, both chemistry and HRM courses were virtually synchronous due to the COVID-19 pandemic, while in years 2 and 3, the courses were in person. In each of the three years, the interdisciplinary collaboration started at week 6 of the 12 weeks (Phase 2), with the chemistry students presenting their research to the HRM students, and the HRM and chemistry students doing their final presentations at week 12 (Phase 3). The HRM and chemistry presentations from Year 1 were then used to develop SDG-focused topics for the project in Year 2, and the research from Year 2 was used to develop SDG-focused topics for research in Year 3, resulting in further knowledge sharing across semesters and collaboration modalities (asynchronous and synchronous). The project sequence, delivery mode, and student groupings are summarized in Figure 3.

Chemistry students in the asynchronous collaboration mode conducted their supervised research, literature review, and experimental research after watching the recordings of the presentations made by HRM and chemistry students in the previous year’s course. This then formed the basis for the next cohort’s interdisciplinary group project.

2.3. Text Analysis of Student Writing: LIWC-22 and Google Notebook Language Model

To assess improvements in writing, we used LIWC-22 (Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count, version 22) to analyze the HRM and chemistry students’ writing. LIWC-22 is a psychometrically validated text analysis software that consists of 12,000 words, word stems, phrases, and select emoticons and maps them onto psychosocial constructs [10]. The LIWC-22 software analyzes text and returns a score for each linguistic dimension (e.g., cognition) based on the percentage of words that match the corresponding dictionary category. Because these scores are calculated from the proportion of words in each dimension, they can be treated as continuous outcomes and analyzed using linear mixed-effects models.

We chose linear mixed-effects models for the HRM student data because each student completed five writing exercises over the term—which is a clear repeated-measures structure—and our goal was to examine whether writing performance improved (indexed by increases in cognition- and curiosity-related language) as students progressed through labor-relations-focused PBL activities and their SDG-focused project with chemistry students. Linear mixed-effects models also allow us to compare between cohorts.

For each sample of each student’s writing (e.g., for each labor relations exercise plan or chemistry student reflection), we applied LIWC-22’s validated internal dictionaries of “Cognition” and “Curiosity” to examine for changes in the use of cognition and curiosity language as they progressed throughout the semester.

The LIWC-22 metric for curiosity and cognition extracted from each student’s reflection was then analyzed using R-version that allowed us to conduct multivariate statistical tests for improvements within and between cohorts.

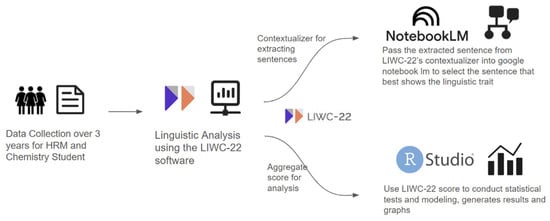

To further examine the context of the sentences where curiosity or cognition language is used, we first pre-processed all the text by converting it to lowercase, removing all punctuation except periods, and omitting sentences shorter than 10 words. Scores on cognition and curiosity extracted from using the LIWC-22 dictionary, along with word counts, were then aggregated per student and per reflection. The LIWC-22’s sentence extraction tool—the contextualizer—was then used to identify all sentences that were in the dictionary for cognition or curiosity (see Figure 4 for a diagram illustrating the pre-processing of sentences).

Figure 4.

This figure represents how the data was processed for the student’s reflections with LIWC-22 and Google Notebook LM before conducting statistical analysis. The arrows represent the temporal order and software(s) used to process the data.

We used the pre-defined categories of LIWC-22 to first identify key sentences containing specific language of curiosity and cognition relevant to our research questions. The scoring for each sentence or phrase was assigned by LIWC-22. For example, in the inputted sentence: “The experiment made me curious about clean water problems”, the words “experiment” and “problem” belong to the “cognition” category, and the word “curious” belongs to the “curiosity” category, and the word count = 12. From this, the LIWC-22 output would be as follows: Cognition = 16.7 = 100 × (2/12), and Curiosity = 8.3 = 100 × (1/12). This process enabled us to find writing samples from HRM and chemistry students that strongly exemplify the linguistic features that allow us to illustrate high- and low-use cases of cognition and curiosity in their writing (see Table 2 and Table 3 for examples) based on how many words are written.

Table 2.

Examples of high and low use of cognition language in HRM and chemistry students identified by LIWC-22 and extracted with the Google Notebook Language Model.

Table 3.

Examples of high and low use of curiosity language in writing by HRM and chemistry students identified by LIWC-22 and extracted with the Google Notebook Language Model.

We then used LIWC-22’s sentence extraction feature, called the contextualizer, which automatically selects and isolates all sentences in the dataset that contain words from our chosen dictionary category, namely cognition and curiosity. These extracted sentences from LIWC-22 were then combined with their source paragraph and inputted through the Google Notebook Language Model (NotebookLM) for secondary analysis and comparison. We carefully crafted a prompt that instructed the NotebookLM to act as a semantic decider, comparing the extracted sentences to the full text. The prompt’s objective was to identify the single most representative sentence from the extracted set of sentences that best encapsulated the semantic intent of the original paragraph. The NotebookLM selected the single most representative quote of the language type per assignment for each student. Importantly, NotebookLM was used solely for qualitative illustration rather than for automated evaluation or scoring—which was performed by LIWC–22, as seen in Figure 4. Table 1 and Table 2 show example phrases or sentences of the two categories and illustrate high- and low-use cases of cognition and curiosity language demonstrated by HRM and chemistry students.

Language illustrating “cognition” within the LIWC-22 dictionary reflects the development of thinking and metacognitive skills [10]. It encompasses dimensions such as cognitive processes (e.g., insightful language, causal language), language that highlights memory (i.e., consists of the use of words such as “remember” and “forget”) and all-or-none thinking (i.e., absolutist language which consists of the use of words such as, “all”, “none”, and “ever”). Table 1 shows examples of high- and low-use cases of cognition language demonstrated by the HRM and chemistry students. It illustrates how reflecting more deeply (i.e., meta cognizing) on the discipline-specific PBL activities (e.g., on the arbitration role play by the HRM students in their final exams) helps them uncover a solution to the SDG-focused interdisciplinary problem.

Writing reflecting “curiosity” highlights interest in new knowledge or experiences. It encompasses words such as “look for”, “research”, and “wonder” and is predicted to be correlated with the personality dimension of openness to new experiences [10]. Curiosity ignites innovation and cultivates critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Table 2 shows examples of high and low-use cases of curiosity demonstrated by HRM and chemistry students. The curiosity language used by the chemistry student illustrated in that table demonstrates an appreciation for learning the complexities of the SDG-focused interdisciplinary problem.

2.4. Analysis Plan

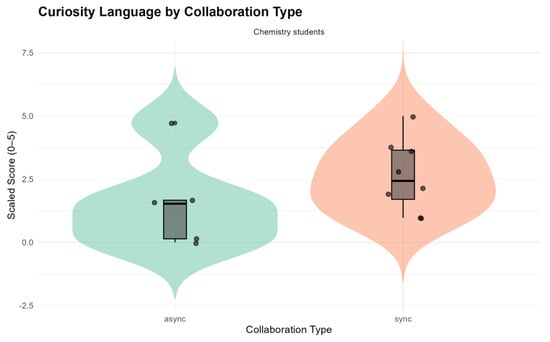

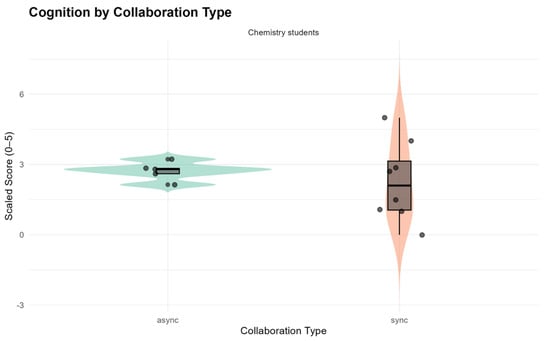

All statistical analyses were conducted in R, and we used the dplyr and ggplot2 packages for data cleaning and visualization. The lme4 and means package were used to conduct linear mixed-effects models. The dependent variables were LIWC-22 category scores for Curiosity and Cognition, which represent the percentage of words in each text that matched the corresponding LIWC dictionary. For descriptive comparisons, these scores were rescaled to a 0–5 range to facilitate visualization (e.g., for the violin plots seen in Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Violin plot depicting the distributions and means of curiosity (top panel) and cognition (bottom panel) language scores amongst chemistry students collaborating asynchronously and synchronously with HRM students. The squares represent box plots, and the dots represent individual data points.

For HRM students, we used linear mixed-effects models to assess whether their use of cognition- and curiosity-related language increased across the semester. This analytical approach was chosen because each HRM student completed multiple writing exercises over the term (5 preparatory memos and reflections, plus their final exam reflections), creating a clear repeated-measures structure. Furthermore, LIWC-22 analyzes text and returns a score for each linguistic dimension -- cognition and curiosity -- based on the percentage of words that match the corresponding dictionary category. Specifically, for each writing sample, the LIWC-22 score is calculated as follows: (number of words matching the dictionary/total word count) × 100. Because these scores represent proportions scaled from 0 to 100, they can be treated as continuous outcomes suitable for the linear mixed-effects analyses. Our goal was to examine whether writing as indexed by increases in cognition- and curiosity-related language improved s students progressed through labor-relations-focused PBL activities in the semester and collaborated with chemistry students on their SDG-focused project.

We acknowledge that the small chemistry student sample limits statistical power to detect significant differences. Non-significant permutation test results should be interpreted cautiously as inconclusive rather than as definitive evidence of no effect. The descriptive statistics and violin plots (Figure 5) provide complementary information about distributional patterns and potential trends that warrant investigation into larger, future samples. Our primary goal with the chemistry student data was exploratory -- to document preliminary patterns that could inform hypothesis generation for subsequent research. Furthermore, because the chemistry sample was small (n = 13), a non-parametric exact permutation test was used instead of standard parametric models. The permutation test compared the mean LIWC scores between the asynchronous and synchronous collaboration groups without assuming normality or equal variances. This approach provides valid p-values and controls Type I error in small-sample settings but does not increase statistical power. For each variable, the difference in group means (sync–async) was computed, and 10,000 random label permutations were used to estimate the null distribution. Effect sizes were reported using Cliff’s Δ with 95% confidence intervals.

3. Results

Building on Hillocks’ [38] inquiry-based framework and Kellogg’s [17] cognitive model, our results address two core questions: (1) How do labor-relations-focused PBL activities influence the use of language reflecting cognition and curiosity in writing? (2) Does collaboration mode (synchronous vs. asynchronous for chemistry students; virtual vs. in-person for HRM students) shape these outcomes?

We found that HRM students taking in-person classes showed significant increases in the use of curiosity-related language across the semester compared to those in virtual classes (see Table 4). Chemistry students who collaborated synchronously with HRM students displayed higher curiosity in their writing than those who learned in asynchronous environments.

Table 4.

Statistical comparison of in-person synchronous classes versus virtual synchronous classes for HRM students.

3.1. Impact of Labor-Relations-Focused PBL Activities

We explored how labor-relations-focused PBL activities impacted the HRM students across the three years. We conducted linear mixed effects analyses by including the assignment type (nested within student), year, and instruction modality as fixed effects and random intercepts for students. This allowed us to account for each HR student’s writing baseline and the sequential nature of the writing they did. We used all five reflections that the HRM students wrote during the semester in addition to their reflections about these activities on the reflective final exam.

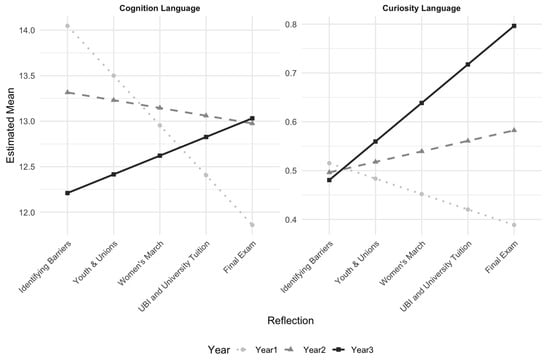

Over the three years, we found that there was a significant increase in the use of curiosity-related language among HRM students reflecting a greater interest in new knowledge or experiences (see Figure 6 for comparison of yearly slopes).

Figure 6.

Estimated model-based means for the use of language that reflects thinking and metacognition (Cognition) and language that reflects curiosity.

However, the effect of labor-relations-focused PBL activities on cognition-related language was mixed: HRM students in Year 1 (during the COVID-19 pandemic) showed a steady decline, Year 2 remained flat, while only Year 3 demonstrated a consistent and positive increase over time (see Figure 3). When aggregated across all three years, this pattern resulted in no significant increase in the number of words that reflect thinking and metacognition (β = −0.046, SE = 0.106, p = 0.665).

3.2. Impact of Synchronous vs. Asynchronous Learning on Chemistry Students

We found that in general, chemistry students in the synchronous setting tend to use more varied and expressive language. Their scores are more dispersed across several categories, though not always higher on average.

For this analysis, we rescaled the original LIWC-22 scores obtained from the software (as described earlier) to a scale from 0 to 5 to better visualize the data and observe outliers (see Figure 6). We found that chemistry students in synchronous learning environments demonstrated more of an interest in learning new knowledge or gaining new experiences (Msync = 2.64, SDsync = 1.42) when compared to those in the asynchronous environments (Masync = 1.61, SDasync = 1.9).

In contrast, chemistry students in asynchronous collaborative learning environments were more likely to use language reflecting thinking and metacognition (Masync = 2.72, SDasync = 0.4) than those collaborating synchronously (Msync = 2.27, SDsync = 1.68).

Due to the small sample size of chemistry students (n = 13), we used an exact permutation test on these rescaled LIWC-22 scores rather than rely on the typical parametric tests that assume larger sample distributions. This approach reduces the risk of inflated Type I error; however, it does not enhance statistical power to detect significant differences. On the permutation test, group means for cognition were Masync = 8.57 and Msync = 8.15 (difference = −0.42; exact p = 0.58; Cliff’s Δ = −0.20). While for curiosity language, the permutation test group means were Masync = 0.45 and Msync = 0.52, (difference = +0.07; exact p = 0.28; Cliff’s Δ = 0.45). The test showed that there were no statistically significant differences between chemistry students collaborating synchronously or asynchronously on their use of cognition and curiosity language. Nevertheless, Figure 6 shows that overall, synchronous collaborations tended to show more dispersed and varied curiosity-related language scores amongst chemistry students while asynchronous collaborations were associated with narrower range and higher cognition-related language gains.

3.3. Impact of Virtual vs. In-Person Synchronous Class on HRM Students

To examine the impact of virtual vs. in-person synchronous instruction on HRM students, we repeated the same linear mixed effects analyses as described earlier, except in this analysis we also examined whether the type of instruction had an impact (Year 1 was coded as virtual; years 2 and 3 were coded as in person). This analysis allowed us to account for each student’s baseline writing characteristics, the sequential nature of the writing that the HRM students did and compare the slopes across cohorts. This analysis tests whether there was an effect of modality of instruction -- virtual vs. in person -- on writing.

We found a significant difference between the virtual and in-person mode of instruction on HRM students’ writing. For the virtual synchronous instruction mode, there was a significant negative slope (t(77.795) = −2.471, β = -0.547, SE = 0.221, p = 0.016), while for classes taught in the in-person synchronous mode, the slopes were non-significant for Year 2 and positive but non-significant for Year 3 (see Figure 5). More importantly, this analysis showed that compared to Year 1, students in Year 3 used significantly more words reflecting thinking and metacognition (t(74.8) = 2.685, β = 0.752, SE = 0.280, p = 0.024; see Figure 5), which indicates, compared to Year 1, HRM students in Year 3 were using significantly more words that reflect thinking and metacognition.

When examining HR students’ use of curiosity language, we see a similar pattern: Year 3 showed a significant increase compared to Year 1 (t(73.4) = 2.648, β = 0.111, SE = 0.042, p = 0.027). In Year 1, there was a negative—but non-significant—slope, for Year 2 the slope was more positive albeit still non-significant, and for Year 3 the slope was both positive and significant (t(84.94) = 3.39, β = 0.095, SE = 0.0279, p = 0.001, see Figure 5).

4. Discussion

In our study, we investigated how SDG-focused collaborations between HRM and chemistry students shape their curiosity and cognition. We show that (1) HRM students participating in in-person synchronous classes demonstrated significant gains in curiosity-related language over the semester, with more nuanced patterns observed for cognition-related language; and (2) chemistry students collaborating synchronously with these HRM students displayed higher curiosity in their writing than those in asynchronous environments, with collaboration mode distinctly influencing the expression of both curiosity and cognitive language. These results contribute to new evidence supporting the value of structured, experiential, interdisciplinary, and collaborative learning approaches for fostering communication skills in higher education institutions.

Across the three years of the interdisciplinary Global Classroom, we found evidence that discipline-specific PBL activities (conducting literature searches, writing plans on debates about UBI) and SDG-focused interdisciplinary PBL group activities can improve both chemistry and HRM students’ writing to reflect increasing cognition and curiosity. These are important features of writing that enable such students to be effective communicators in the workforce—an attribute that employers seek in those they hire [6,7].

To better understand these patterns, it is important to consider how the structure and experience of the labor-relations-focused PBL activities, the chemistry-relevant supervised research study experiences, and the SDG-focused group project as the backdrop for how the type of collaboration shaped the learning and writing of the HRM and chemistry students. The collaboration process between the HRM and chemistry students, visually mapped in Figure 3, synthesizes the sequence of interdisciplinary team building and knowledge sharing experiential activities that students from both disciplines engaged in. This visualization underscores how deliberate structuring of interdisciplinary collaboration enabled HRM and chemistry students to develop expertise in the SDG-focused problem to be solved and in their interdisciplinary teamwork skills.

4.1. Writing Improvements in HRM Students

HRM students progressively enriched their writing with language signaling curiosity and a pursuit of new knowledge as they engaged in the labor-relations PBL activities (like advocating for youth in unions) and the SDG-focused group project. The patterns observed for increases in curiosity language showed consistent growth throughout the semester, with the most pronounced gains occurring in Year 3, coinciding with the resumption of in-person, synchronous learning and collaboration after the COVID-19 pandemic disruptions.

In-person and synchronous learning environments provide more frequent opportunities for asking questions, engaging in meaningful dialogue, and receiving immediate feedback. Such learning environments encourage students to seek out new information, question assumptions, and engage more deeply in the subject matter, all of which strengthen curiosity. These labor-relations-focused PBL experiences (e.g., debating UBI policy) introduce novel contexts that supported the three stages of the HRM students’ writing process—telling, transforming, and crafting—as described by Kellogg [17] and validated with management students taking leadership skills courses by Howard et al. [18]. This iterative labor-relations-focused writing enhanced HRM students’ ability to communicate the knowledge they acquired effectively.

Importantly, writing and debriefing about their labor-relations-focused PBL experiences (e.g., debating the effectiveness of UBI) was transferable. When the HRM students transitioned to the interdisciplinary SDG-focused group project, where they were required to collaborate and communicate with their chemistry teammates, these HRM students were then better able to effectively communicate with them—an ability that was understandably lowered as the pandemic progressed. Since the return to in-person teaching, however, and with more robust inter-disciplinary team building activities like field trips to organic farms and culinary workshops—we showed that the shared, concrete team building and knowledge sharing experiences that were essential for building trust and effective communication between HRM and chemistry students improved their curiosity, thinking, and metacognitive skills.

However, there are caveats on the extent to which the HRM students’ writing improved in our study. We did not find an overall significant increase in the use of cognition language across the different assignments within each, although there is a positive trend in Year 3. Year 1 was virtual and synchronous only and conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic where we see the HRM students’ use of such language declining over the course of the semester. The topic of the SDG-focused interdisciplinary group project (i.e., vaccine access) along with the challenges of online synchronous courses, such as poor-quality technical infrastructure, possibly resulted in the lack of adequate verbal and nonverbal cues, all inhibiting communication and feedback, and leading to poorer quality interpersonal interactions and inter-group collaborations. This in turn may have decreased the quality of teamwork and engagement, leading to lowered use of cognition language. By contrast, Year 3’s return to face-to-face instructional and collaboration formats enabled richer peer interactions, continuous group engagement, and more authentic team-building activities—supporting both general writing growth and more effective interdisciplinary communication.

4.2. Writing Improvements in Chemistry Students

Our analysis of the chemistry students’ reflections reveals important insights into how relevant SDG-focused topics and the collaboration modality with HRM students shape the cognitive and linguistic features of their written work. Our findings suggest that real-time interpersonal interactions in global classroom projects provide chemistry students collaborating synchronously with their HRM peers opportunities to express themselves more richly and integrate their novel learning experiences into their reflections. The benefit is particularly pronounced for chemistry students engaging in the synchronous PBL activities (e.g., making a 5-min presentation on their SDG-focused chemistry research on the crop or vaccine to the HRM students) and real-time team interactions like going together on field trips to local farms, cooking together in a culinary workshop, or attending a presentation about current research on COVID-19 vaccine development, with their HRM teammates. These activities create opportunities for chemistry students to speak about their learning from their laboratory and literature research to their HRM peers. By “talking” to their HRM teammates about their research, these chemistry students also “transformed” the relevance of their disciplinary research [18], thus improving the “crafting” of their reflections and theses. These chemistry students became more curious and acquired metacognitive skills by thinking about the broader implications of their disciplinary research in their reflections and theses.

Synchronous collaborations, by facilitating immediate dialogue, explanation of ideas, and constructive peer feedback, appeared to support more curiosity-related language use, as reflected in the broader dispersion of LIWC-22 scores for that category. In contrast, asynchronous collaborations—with no real-time interaction and dialogue—were associated with higher use of cognition-related language but narrower score distributions, suggesting a more standardized writing style. The absence of frequent, live interdisciplinary exchanges may constrain chemistry students collaborating asynchronously in their ability to incorporate new learning moments—the experience emphasizing instead individual processing and structured reasoning.

These patterns indicate that synchronous interdisciplinary collaboration fosters engagement, boldness, and emotionally expressive writing, while asynchronous collaboration supports deeper cognitive processing, reflection, and careful reasoning—both supporting distinct aspects of writing development in STEM career development contexts such as the supervised research study course. Overall, the findings from these chemistry students’ reflections underscore the role of collaboration modality in shaping how they reflected on their global interdisciplinary, SDG-focused PBL project experiences.

4.3. Future Directions and Limitations

Because the Global Classroom brings together students from diverse disciplines and cultural backgrounds, solving global problems contextualized in specific countries or communities, future research is ripe. One area we are currently investigating is how cultural and gender norms intersect in predicting how these students are rated as leaders [40] and how their writing quality predicts how they are rated as leaders [41]. This would be the first step in a program of research establishing that the writing and communication gains observed in this study persist beyond the cohort and translate into other career outcomes. Longitudinal follow-up with the chemistry students after course completion could clarify the long-term impact of these interdisciplinary, collaborative, PBL-based pedagogical interventions.

Another potential limitation of our approach is that all written samples—though authentically produced as graded deliverables for PBL and SDG-focused projects—were generated as part of a formal assignment-based coursework. As such, the observed improvements in curiosity and metacognition could reflect both genuine engagement and responses tailored to academic prompts and grading expectations. While the HRM students’ written products included plans for debates, accessibility audits, final exam answers analyzing labor-relations issues—distinct from traditional long-form reflective essays—these texts still offer rich, contextually grounded insight into their curiosity and metacognitive skill development. Future research may expand analysis to professional or co-curricular writing samples to further test generalizability.

Here, we would like to note that our findings for chemistry students should be taken with caution given their small number in our sample; future work should examine whether these trends are robust in larger and more diverse cohorts. In addition, the present results reflect the experiences of undergraduate students in one institutional setting; comparative studies at other universities, with collaborations amongst students from different academic disciplines, and at the graduate or professional level, are needed to improve generalizability.

4.4. Implications for Research, Pedagogy, and Student Learning Outcomes

The current study provides new evidence that PBL activities coupled with SDG-focused interdisciplinary collaboration significantly enhance students’ writing skills—including curiosity, cognition, and metacognitive language—attributes increasingly valued by employers [20]. Prior research shows that language reflecting metacognition is a strong predictor of employability, underscoring the importance of pedagogies that promote these skills [42].

To better prepare students for the workforce, future research should identify which types of PBL activities most effectively develop different writing and communication competencies. For example, future studies can vary the specific features of our labor-relations-focused PBL activities to determine which features best supported writing gains—a gap that points to the need for a taxonomy of PBL scenarios tailored for various disciplines and learning outcomes.

Our findings also illustrate the utility of text analysis tools for educators, providing a scalable way to monitor whether their pedagogical activities are producing the desired improvements in student writing. With the growing integration of large language models (LLMs) into social science research, our study also adopted these tools to enhance qualitative interpretation. Recent work has demonstrated the potential of LLMs for social simulation and qualitative analysis, highlighting their role in extending traditional research methods with computational depth [43,44]. Following this line of work, we incorporated both LIWC-22 and the Google Notebook Language Model into our text analyses to assess how both HRM and chemistry students develop in their communication and written skills across the semester while they collaborated on an SDG-focused problem.

Further research should systematically evaluate PBL course design features—including feedback processes, opportunities for practice, and incentive structures—to determine how these elements contribute to student learning. By integrating empirical assessment and pedagogical innovation, future work can guide the development of more effective, discipline-specific, and transferable models of problem-based and collaborative learning.

5. Conclusions

The Global Classroom demonstrates that embedding PBL activities and enabling structured SDG-focused collaboration between students from different disciplines on projects involving sustainability can meaningfully shape their writing. It amplifies the use of language associated with curiosity and cognition -- skills highly sought after by employers. The increased use of language associated with curiosity and cognition is the greatest when collaboration is synchronous and in-person. HRM students who engage in live, face-to-face PBL exercises showed greater gains in metacognitive and exploratory language in Year 3 (compared to Year 1). Similarly, chemistry students who collaborated in real time with HRM peers exhibited richer, more varied reflections than those in the asynchronous settings, highlighting the power of immediate dialogue and shared experiences in driving deeper cognitive engagement.

These results carry important implications for both pedagogy and future research. Educators should prioritize authentic, discipline-specific PBL scenarios and real-time collaboration modalities to foster essential communication skills that employers value. At the same time, text-analysis tools like LIWC-22 offer a scalable way to monitor, give feedback on, and refine writing outcomes [39]. Moving forward, scholars should probe which PBL design elements most effectively cultivate writing competencies across diverse fields and explore methods to replicate the benefits of synchronous interaction in virtual or hybrid environments. This ensures that all students, regardless of context, gain the metacognitive and curious mindset needed to tackle complex, contemporary sustainability problems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.R. and N.T.; methodology, P.R. and N.T.; data analysis, Y.P. and J.H.; investigation, P.R. and N.T.; data curation, Y.P. and J.H.; writing—original draft preparation, P.R., N.T., Y.P. and J.H.; writing—review and editing, P.R., N.T. and J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Toronto (#35602 6 January 2018 to 9 January 2027).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Gen AI Use: Generative artificial intelligence tools, including large language models, were used with human oversight for three purposes in this study: aiding in selecting the qualitative quotes for text analysis as described above, assisting in the summary of peer-reviewed sustainability literature, and clarifying text in the manuscript. All AI-generated outputs were reviewed, critically edited, and verified for accuracy and interpretive integrity by the authors. No GenAI was used for data analysis, raw data interpretation, or scientific conclusions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Prensky, M. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. Horizon 2001, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, J.K.; Wood, W.B. Teaching More by Lecturing Less. Cell Biol. Educ. 2005, 4, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sadik, A.; Al Abdulmonem, W. Improvement in Student Performance and Perceptions through a Flipped Anatomy Classroom: Shifting from Passive Traditional to Active Blended Learning. Anat. Sci. Ed. 2021, 14, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoun, J. Robot-Proof: Higher Education in the Age of Artificial Intelligence; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0-262-34431-9. [Google Scholar]

- Deeley, S.J. Summative Co-Assessment: A Deep Learning Approach to Enhancing Employability Skills and Attributes. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2014, 15, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finley, A. How College Contributes to Workforce Success; Hanover Research; Association of American Colleges and Universities: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, K.; Lower, C.L.; Rudman, W.J. The Crossroads between Workforce and Education. Perspect. Health Inf. Manag. 2016, 13, 1g. [Google Scholar]

- Sundman, J.; Feng, X.; Shrestha, A.; Johri, A.; Varis, O.; Taka, M. Experiential Learning for Sustainability: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda for Engineering Education. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2025, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham Xuan, R.; Håkansson Lindqvist, M. Exploring Sustainable Development Goals and Curriculum Adoption: A Scoping Review from 2020–2025. Societies 2025, 15, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R.L.; Ashokkumar, A.; Seraj, S.M.; Pennebaker, J.W. The Development and Psychometric Properties of LIWC-22; University of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX, USA, 2022; Volume 10, pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan, P.; Thavarjah, N.; Romain, J. Engaging Management and STEM Students in Solving Global Problems of Sustainable Development. In The Palgrave Handbook of Social Sustainability in Business Education; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 271–288. ISBN 978-3-031-50167-8. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, F.; Sun, T.; Westine, C.D. A Systematic Review of Research on Online Teaching and Learning from 2009 to 2018. Comput. Educ. 2020, 159, 104009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wempe, B.; Collins, R.A. Students’ Perceived Social Presence and Media Richness of a Synchronous Videoconferencing Learning Environment. Online Learn. 2024, 28, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liskala, T.; Volet, S.; Lehtinen, E.; Vauras, M. Socially Shared Metacognitive Regulation in Asynchronous CSCL in Science: Functions, Evolution and Participation. Frontline Learn. Res. 2015, 3, 78–111. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, J.; Kirschner, P.A. Applying Collaborative Cognitive Load Theory to Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning: Towards a Research Agenda. Educ. Tech. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, K.D. Promoting Student Metacognition. Life Sci. Educ. 2012, 11, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellogg, R.T. Training Writing Skills: A Cognitive Developmental Perspective. J. Writ. Res. 2008, 1, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Z.; Hoang, J.; Radhakrishnan, P. Problem-Solving Activities and Business Students’ Writing and Performance. In Proceedings of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology Annual Conference, Boston, MA, USA, 19–22 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gossman, P.; Stewart, T.; Jaspers, M.; Chapman, B. Integrating Web-Delivered Problem-Based Learning Scenarios to the Curriculum. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2007, 8, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Saab, N.; Post, L.S.; Admiraal, W. A Review of Project-Based Learning in Higher Education: Student Outcomes and Measures. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 102, 101586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, H.M.; Fossum, M.; Vivekananda-Schmidt, P.; Fruhling, A.; Slettebø, Å. Teaching Clinical Reasoning and Decision-Making Skills to Nursing Students: Design, Development, and Usability Evaluation of a Serious Game. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2016, 94, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrows, H.S. Problem-based Learning in Medicine and beyond: A Brief Overview. New Dir. Teach. Learn. 1996, 1996, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.F. ABC of Learning and Teaching in Medicine: Problem Based Learning. BMJ 2003, 326, 328–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savery, J.R. Overview of Problem-Based Learning: Definitions and Distinctions. Interdiscip. J. Probl. -Based Learn. 2006, 1, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, G.; Elden, M. Introduction to the Special Issue: Problem-Based Learning as Social Inquiry—PBL and Management Education. J. Manag. Educ. 2004, 28, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, Y.; Pattinson, B.; McCarthy, J.; Beecham, S. Transitioning from Traditional to Problem-Based Learning in Management Education: The Case of a Frontline Manager Skills Development Programme. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2017, 54, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A. The Impact of PBL on Transferable Skills Development in Management Education. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2016, 53, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, S.A.; Stroup-Benham, C.A.; Litwins, S.D. Cognitive Benefits of Problem-Based Learning: Do They Persist through Clinical Training? Acad. Med. 2001, 76, S84–S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, W. Theory to Reality: A Few Issues in Implementing Problem-Based Learning. Educ. Tech. Res. Dev. 2011, 59, 529–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckenna, T.; Gibney, A.; Richardson, M.G. Benefits and Limitations of Adopting Project-Based Learning (PBL) in Civil Engineering Education—A Review. In Proceedings of the IV International Conference on Civil Engineering Education (EUCEET), Barcelona, Spain, 5–8 September 2018; pp. 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Harun, N.F.; Yusof, K.M.; Jamaludin, M.Z.; Hassan, S.A.H.S. Motivation in Problem-Based Learning Implementation. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 56, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotgans, J.I.; Schmidt, H.G. Problem-Based Learning and Student Motivation: The Role of Interest in Learning and Achievement. In One-Day, One-Problem; Springer: Singapore, 2012; pp. 85–101. ISBN 978-981-4021-74-6. [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan, P.; Schimmack, U.; Lam, D. Repeatedly Answering Questions That Elicit Inquiry-Based Thinking Improves Writing. J. Instr. Psychol. 2011, 38, 247–252. [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan, P.; Kerr, E. Prompted Written Reflection as a Tool for Metacognition: Applying Theory in Feedback. Teach. Metacognition 2018, 2, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Frymier, A.B.; Shulman, G.M. “What’s in It for Me?”: Increasing Content Relevance to Enhance Students’ Motivation. Commun. Educ. 1995, 44, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, J.R.; Karabenick, S.A. Relevance for Learning and Motivation in Education. J. Exp. Educ. 2018, 86, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kember, D.; Ho, A.; Hong, C. The Importance of Establishing Relevance in Motivating Student Learning. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillocks, G. Research on Written Composition: New Directions for Teaching. In National Conference on Research in English; ERIC Clearinghouse on Reading and Communication Skills, National Institute of Education: New York, NY, USA; Urbana, IL, USA, 1986; ISBN 978-0-8141-4075-8. [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan, P.; Hoang, J.; Howard, Z. Telling, Transforming, and Crafting: How Reflecting on Career-Relevant Problem Based e-Learning Activities Improved Students Writing Skills. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual Technological Advances in Science, Medicine, and Engineering Conference, Toronto, ON, Canada, 7–8 July 2024. [Google Scholar]