Abstract

This paper investigates the impact of U.S. monetary policy on capital flows to emerging market economies and examines the role of capital controls in moderating this effect. Using a fixed-effects model with panel data from 19 developing nations spanning 2005Q1 to 2024Q3, we find that U.S. monetary tightening significantly reduces net capital inflows to these economies, undermining stable financing conditions necessary for long-term development. Countries with stronger capital controls are more insulated from these shocks and demonstrate greater financial resilience. This is because well-designed capital controls primarily target volatile short-term flows that are most susceptible to external policy shocks, while leaving stable, long-term productive investment largely unaffected. The study further reveals that during periods of unconventional monetary policy, the negative impact of U.S. policy shocks was more pronounced; short-term capital flows were highly responsive to policy changes, while foreign direct investment remained largely stable; and low- and middle-income nations experienced more severe disruptions than their high-income counterparts. These findings highlight the value of composition-targeted capital flow management in safeguarding financial stability and supporting sustainable development in emerging markets amid external monetary volatility.

1. Introduction

As global financial integration has deepened over the past two decades, Emerging Market Economies (EMEs)—economies that meet specific size, liquidity, and market accessibility requirements but do not fully satisfy the economic development and institutional stability criteria for developed market status—have gained substantial economic prominence. The combined GDP share of the world’s 10 largest EMEs, including China, India, Brazil, Russia, and South Korea, and others, has more than doubled from 13% in 2000 to 31% in 2023. However, EMEs remain particularly susceptible to advanced economy monetary policies. This was exemplified by the post-2008 period: while the Fed’s quantitative easing (QE) drove significant capital inflows to EMEs [1,2], the 2013 taper tantrum caused a dramatic reversal, with low-reserve countries experiencing nearly 15 percent currency depreciation and increased financing premia [3].

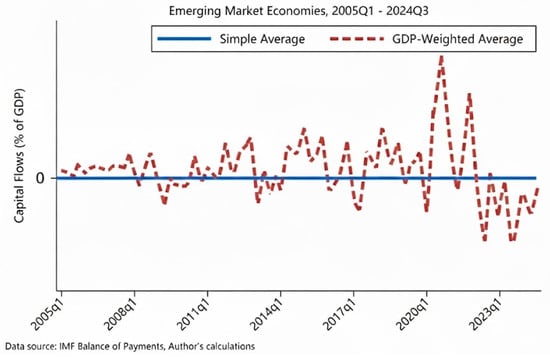

Figure 1 illustrates the dramatic boom–bust cycles in net capital inflows to our 19-EME sample over 2005Q1–2024Q3, with surges during Fed QE and sharp reversals during the 2013 taper tantrum and 2022–2023 tightening. The exceptional 2020–2022 spike reflects unprecedented Fed pandemic-era accommodation ($120 billion monthly asset purchases), while the 2023 decline followed the Fed’s rapid 525-basis-point tightening cycle. The sample comprises 19 EMEs: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Russia, South Africa, Thailand, Turkey, and Vietnam.

Figure 1.

Evolution of Cross-Border Capital Flows.

In response to U.S. monetary policy spillovers, numerous EMEs have implemented targeted capital flow management measures designed to mitigate external pressures while preserving domestic financial stability and long-term development capacity. U.S. monetary policy, whether conventional monetary policy (CMP) or unconventional monetary policy (UMP), exerts profound influence on EMEs [4,5]. CMP tightening creates severe external pressures through currency appreciation and elevated debt servicing costs. During the 2015–2018 Fed rate hike cycle, the federal funds rate rose from 0.25% to 2.5%, resulting in a 17% appreciation of the U.S. dollar index and causing Turkey and Argentina’s currencies to plummet by 45% and 50%, respectively, in 2018 [6,7]. Conversely, UMP creates equally challenging dynamics by driving excessive capital inflows to EMEs seeking higher yields [8]. During COVID-19, the Fed’s unprecedented QE triggered substantial portfolio investment flows, with EMEs receiving over $90 billion in inflows between April 2020 and December 2021 [9,10]. Both policy stances complicate local monetary policy by forcing EME authorities to balance growth objectives against financial stability risks [11].

These measures differentiate between flow types: stricter restrictions on volatile short-term capital—such as portfolio flows and bank lending—that are highly sensitive to global financial conditions, while maintaining openness to more stable, long-term investment. During the 2013 taper tantrum, Brazil eliminated taxes on foreign debt investment while deploying FX swaps, achieving 10% real appreciation within a month [12]. India tightened outflow regulations, while Argentina combined FX controls with interest rate hikes [13]. Conversely, Turkey’s exclusive reliance on rate hikes without capital controls proved less effective. These varied responses demonstrate that properly implemented capital controls generally provided more effective insulation than monetary interventions alone, with economies employing such measures experiencing only marginal long-term growth reductions of 0.1–0.3%, compared to 2–3% contractions in those without [14]. This underscores the critical importance of strategic capital controls in shielding domestic economies from destabilizing external financial shocks and maintaining resilient growth trajectories.

Against this background, this study addresses two central research questions:

RQ1:

How does U.S. monetary policy affect cross-border capital flows to emerging market economies?

RQ2:

To what extent do capital controls moderate the impact of U.S. monetary policy on capital flows to EMEs?

To answer these questions, this study employs a panel dataset of 19 EMEs from 2005Q1 to 2024Q3, utilizing a fixed-effects regression to investigate how U.S. monetary policy affects cross-border capital flows and how capital controls moderate this relationship. The empirical analysis yields three key findings. (1) Baseline results show U.S. monetary tightening significantly reduces net capital inflows to EMEs, potentially disrupting financing stability. (2) Capital controls weaken the impact of U.S. monetary policy on EME capital flows, providing empirical evidence that capital flow management measures help build financial resilience against external shocks. (3) Heterogeneity analysis reveals that compared with CMP, EMEs exhibit heightened sensitivity to UMP tools; portfolio and other investments respond more strongly to U.S. policy changes than foreign direct investment (FDI), reflecting inherent differences in risk characteristics, liquidity, and contributions to economic stability; low- and middle-income countries demonstrate greater sensitivity than high-income EMEs.

This paper contributes to the literature in two key aspects.

First, it provides an EME-focused empirical analysis. While prior literature has predominantly examined U.S. monetary policy impacts on global capital flows [5,15] or used samples limited to developed economies [16,17,18], specific attention to EMEs has been limited. Given that EMEs occupy a distinct position in the international monetary system and face significant exposure to external financial conditions [19,20] this study examines panel data from 19 EMEs spanning 2005Q1 to 2024Q3. Recognizing substantial heterogeneity among EMEs in income levels, financial development, and capital flow composition, the paper explores differential impacts across CMP versus UMP periods, capital flow types (FDI, portfolio investment, and other investments), and income levels. Understanding these heterogeneous responses is critical for promoting stable capital flow patterns, as different EMEs face varying capacities to absorb external shocks [21] and capital flow types exhibit distinct sensitivities to monetary policy shifts [22]. This multidimensional analysis provides targeted empirical evidence for constructing effective external financial risk prevention systems.

Second, this paper investigates the moderating role of capital controls in the context of U.S. monetary policy spillovers. While substantial research has examined capital control effectiveness [23,24] and U.S. monetary policy cross-border effects [16,25]. However, empirical research on how capital controls buffer these spillovers remains limited, particularly for EMEs. Given the significant role of cross-border capital movements in EME financial systems [19], examining this moderating mechanism is particularly relevant for EMEs seeking to maintain financial stability amid volatile external conditions. By constructing interaction terms between capital control intensity measures and U.S. monetary policy indicators, this study assesses whether capital flow management measures can buffer monetary policy spillovers, contributing to the understanding of policy tools that support long-term financial stability and sustainable development in EMEs.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. U.S. Monetary Policy and Cross-Border Capital Flows in EMEs

U.S. monetary policy represents one of the most significant external factors affecting EMEs, operating as a global force that simultaneously influences capital allocation decisions across all EMEs through its impact on global liquidity conditions and investor risk appetite [4,5]. Interest rate adjustment is a key component of monetary policy. While other instruments face instability and uncertain transmission mechanisms, interest rate changes provide a more direct and observable channel for influencing cross-border capital movements. We argue that U.S. interest rate adjustment policies impact capital flows in emerging market economies primarily through several channels:

First, from the perspective of investment yield differentials, rising U.S. Treasury bond yields prompt global investors to reallocate portfolios based on yield differentials [26,27], often shifting towards U.S. assets and creating carry trade outflows, particularly when EME interest rates are low and unsynchronized with the U.S. Second, the exchange rate fluctuations amplify outflows as dollar appreciation increases foreign currency debt repayment costs for EMEs and reduces the attractiveness of domestic assets to foreign investors, especially in countries with weaker institutions [28]. This currency depreciation also triggers adverse balance sheet effects for EME banks, weakening net worth and constraining lending capacity [29], thereby reducing domestic investment returns and prompting further asset divestment [30]. Third, asset price movements create a vicious cycle: rising U.S. rates depress global risk asset prices, leading to declines in EME equities and bonds [31]. This declining risk appetite prompts foreign investors to sell EME assets, intensifying downward price pressure and exacerbating capital outflows [32]. Fourth, investor expectations play a crucial amplifying role. U.S. rate increases fundamentally alter risk perceptions of emerging economies, leading to expected return adjustments as investors perceive heightened risks and reduce their EME exposure. This expectation transmission accelerates capital withdrawal when U.S. rate increases coincide with global uncertainty [28].

These mechanisms support our first hypothesis, directly addressing RQ1:

H1.

Rises in the U.S. federal funds rate result in reduced capital inflows to emerging market economies.

2.2. The Moderating Effect of Capital Control

Capital controls represent regulatory measures to restrict cross-border capital movements, ranging from administrative restrictions to sophisticated macroprudential tools. Their effectiveness in moderating external spillovers remains contentious: critics document limited defensive capabilities during heightened global risk aversion [33] and unintended consequences through increased foreign currency lending. Conversely, proponents demonstrate their stabilizing role through reduced crisis-related growth losses [14], effective restraint of excessive inflows [34], and enhanced resilience to U.S. monetary policy fluctuations [35].

Capital controls moderate U.S. monetary policy spillovers through two primary channels:

First, the composition effect filters short-term speculative flows while preserving long-term investment. When U.S. rates rise, capital controls impose transaction costs and regulatory compliance requirements that disproportionately deter “hot money” flows—short-term speculative capital characterized by high sensitivity to marginal return differentials and rapid reallocation strategies. These flows face diminished net returns when controls raise explicit costs (taxes, approval delays) and implicit costs (reduced liquidity, convertibility constraints). In contrast, long-term investors such as FDI pursuing fundamental returns based on market size and institutional quality remain relatively insulated, as they amortize regulatory costs over extended horizons and exhibit lower sensitivity to short-term interest rate fluctuations. This differential filtering systematically shifts EMEs’ capital structure toward stability-anchored investment.

Second, the risk-taking channel modifies perceived risk–return tradeoffs across investor types. For short-term investors, capital controls introduce policy uncertainty (reversal risk, enforcement unpredictability and exit constraints) that elevates required risk premiums and reduces risk-adjusted returns below acceptable thresholds. Conversely, long-term institutional investors may interpret stringent controls as credible signals of policymakers’ commitment to financial stability, paradoxically enhancing the investment environment’s perceived quality for fundamentals-focused capital.

Through these mechanisms, capital controls mitigate pro-cyclical volatility by elevating the share of stable, long-maturity capital in EMEs’ external liability structure. Long-term capital exhibits lower elasticity to interest rate differentials, greater tolerance for temporary valuation fluctuations, and higher exit costs that discourage panic-driven withdrawals, thereby reducing “sudden stops” risk [14] and dampening procyclical amplification of global financial shocks.

This framework supports our second hypothesis, directly addressing RQ2:

H2.

The negative impact of U.S. monetary policy tightening on capital flows to EMEs is significantly moderated in countries with stronger capital control measures.

3. Data and Empirical Strategy

3.1. Data and Variables

Our sample comprises 19 major EMEs, including Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Russia, South Africa, Thailand, Turkey, and Vietnam. These countries were selected based on their classification as internationally recognized EMEs, such as the BRICS nations and the Tiger Cub Economies. The selection of these countries is crucial because they represent a diverse set of economies with varying levels of income, financial development, and capital flow dynamics, which allows us to capture a broad range of responses to U.S. monetary policy shifts. The sample period spans from the first quarter of 2005 to the third quarter of 2024, chosen to encompass significant monetary policy shifts and major global financial disruptions, including the 2008 global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic.

The data used in this study primarily come from three categories: first, capital flow indicators. Data concerning net capital flows (NCF) to EMEs were obtained from the IMF’s Balance of Payments Statistics [36], encompassing Net Foreign Direct Investment (Net FDI), Net Portfolio Investment (Net Ptf.Inv.), and Net Other Investment (Net Oth.Inv.). Second, the Effective Federal Funds Rate (EFFR) is derived from the Federal Reserve Economic Data database [37] and the Shadow Short-term Rates (SSR) is based on [38]; Global risk measures such as the VIX index are sourced from the Chicago Board Options Exchange [39] and commodity price indices are obtained from the Commodity Research Bureau. The third category comprises internal factors affecting capital flows in EMEs, with key indicators derived from nominal exchange rates against the U.S. dollar, GDP deflators, and government debt levels, all extracted from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators [40] and IMF International Financial Statistics [41].

3.1.1. The Dependent Variable

Net Capital Flows (NCF) serve as our dependent variable, where positive values indicate net capital inflows and negative values indicate net capital outflows. NCF comprises Net FDI, Net Ptf.Inv., and Net Oth.Inv. Following Ahmed and Zlate and Forbes and Warnock [16,34], we normalize these flows by GDP to facilitate cross-country comparability.

3.1.2. The Key Independent Variable

Our sample period covers both QE and non-QE periods of U.S. monetary policy. Distinguishing between these policy regimes is essential for identifying transmission channels to emerging economies. During conventional periods, policy adjustments via short-term rates influence EMEs primarily through direct interest rate expectations and exchange rate channels. Conversely, at the zero lower bound, the shift to quantitative easing affects external markets through alternative transmission channels, including portfolio rebalancing effects and longer-term yield compression. During QE periods—specifically 2008Q4–2014Q4 and 2020Q1–2022Q2—we employ the SSR developed by Krippner [38] to measure U.S. monetary policy stance, which effectively captures the stimulative effects of unconventional monetary policy, particularly during periods when yield curve inversions occur (where short-term rates equal or exceed long-term rates) and standard interest rates are constrained at the zero lower bound. During non-QE periods, we use the EFFR obtained from the Federal Reserve Economic Data as our policy indicator, which serves as the standard measure of conventional monetary policy stance under normal market conditions [42,43]. Following Anaya et al. [44], this dual-indicator approach enables comprehensive analysis of monetary policy transmission effects across different policy regimes, providing consistent measurement that captures both conventional rate adjustments and unconventional policy interventions throughout our sample period.

3.1.3. Control Variables

Our control variables include both push and pull factors influencing capital flows, consistent with the framework of [19]. Push factors include the VIX index, which measures global financial market volatility and investor risk aversion [19]. Rising VIX levels are typically associated with capital outflows from EMEs [4,15]. We also include the Commodity Research Bureau index to capture commodity price fluctuations, which significantly affect resource-dependent EMEs—rising prices often attract inflows, while declines can trigger outflows [45]. Pull factors comprise the nominal exchange rate against the U.S. dollar. Currency depreciation often undermines investor confidence, potentially triggering capital outflows [46]. We consider changes in the level of total external debt, as these fluctuations impact investor risk perception, thereby amplifying the volatility of capital flows in emerging market economies during external monetary shocks [47] and increasing the risk of capital outflows. Finally, we include the GDP deflator as an indicator of the general price level, as high inflation may deter capital inflows by signaling macroeconomic instability [48].

3.1.4. The Moderating Variable

Capital controls represent regulatory measures implemented by countries to manage cross-border capital movements. To examine the moderating effects in the relationship between U.S. monetary policy and capital flows, we employ the KAOPEN index developed by [49] as a proxy for capital account restrictions. The index is constructed using principal component analysis of binary dummy variables reflecting the presence of multiple exchange rates, restrictions on current and capital account transactions, and requirements for surrendering export proceeds. This de jure measure quantifies the degree of capital account liberalization by analyzing restrictions on cross-border financial transactions. Higher KAOPEN values indicate fewer restrictions on cross-border financial transactions.

Before proceeding to empirical tests, we acknowledge a critical identification challenge inherent in analyzing capital control effectiveness: capital controls may respond endogenously to the capital flow pressures they are designed to regulate. Specifically, EMEs experiencing substantial outflows during U.S. monetary tightening episodes might reactively strengthen controls, creating reverse causality that complicates causal inference. While employing the KAOPEN index as a de jure measure partially mitigates concerns about contemporaneous policy responses, this endogeneity cannot be fully resolved without genuinely exogenous variation in capital account restrictions. Consequently, we interpret H2’s empirical results as robust conditional correlations indicating that countries maintaining historically stronger capital controls tend to experience dampened spillover effects, rather than as definitive causal estimates of control effectiveness. This interpretive constraint should be considered when drawing policy implications from our moderating effect analysis.

For data sources and variable definitions, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable Definitions and Data Sources.

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for our panel dataset of 19 EMEs, comprising 1501 country-quarter observations. NCF, our dependent variable, demonstrates high volatility with a mean of $4540.19 million and a standard deviation of 21,462.52. The substantial variation, ranging from outflows of $191.03 billion to inflows of $231.27 billion, reflects the characteristic volatility of EMEs’ capital flows. The U.S. interest rate in our sample has a mean of 0.91%, ranging from −3.74% to 5.35%, and exhibits a standard deviation of 2.72. This range encompasses the post-2008 accommodative period and subsequent normalization, providing crucial variation for identifying policy transmission effects. It is therefore essential to control for country-specific variables and country fixed effects in our baseline model.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 3 presents the correlation matrix to assess preliminary bivariate relationships and examine potential multicollinearity. The matrix reveals a statistically significant negative correlation between NCF and the U.S. interest rate (−0.1535), consistent with the expected push factor mechanism. Importantly, all pairwise correlations among independent variables remain well below 0.80, with the largest being 0.2246 between exchange rates and GDP deflators, indicating that multicollinearity is unlikely to bias our subsequent regression estimates.

Table 3.

Correlation coefficient matrix between variables.

3.2. Empirical Strategy

3.2.1. Baseline Regression Model

Following Rey [15], we employ an OLS panel regression model to identify the effect of U.S. monetary policy on cross-border capital flows to EMEs. This specification controls for both time-invariant country-specific characteristics and common time-varying global shocks, allowing us to isolate the independent effect of U.S. monetary policy changes on capital flows. The inclusion of time fixed effects () is crucial for controlling potential omitted variable bias stemming from common, unobserved global shocks occurring in period t. To ensure the efficiency of coefficient estimation, especially given the presence of global variables in our model, we incorporate a comprehensive set of time-varying control variables [5,15], including the VIX index (measuring global risk appetite) and the CRB commodity price index (capturing commodity market conditions). Standard errors are clustered at the country level to account for potential within-country correlation of error terms across time periods. This approach follows the methodological framework established in studies published in China Industrial Economics and other leading journals. This approach follows the methodological framework established in studies published in China Industrial Economics and other leading journals that address similar identification challenges in time series cross-sectional analysis.

The baseline regression specification takes the following form:

where represents total cross-border capital flows to EMEs economic I in period t, denotes the U.S. interest rate in period t. and represent push factors, while , , represent pull factors. captures country fixed effects and denotes time fixed effects to control for common global shocks in period t. The coefficient is our primary focus, as it captures the effect of U.S. interest rate on EMEs capital flows.

3.2.2. Moderating Effect Model

To further examine whether capital controls in EMEs can mitigate the impact of U.S. monetary policy on their capital flows, this study extends the baseline regression model by introducing an interaction term between the core explanatory variable and the degree of capital account openness. The specific model specification is as follows:

where represents the intensity of capital account openness for EMEs economic I in period t, and all other variables remain consistent with the baseline regression model.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Baseline Results

Table 4 reports the baseline results from OLS panel regressions with country and time fixed effects. All specifications include both two-way fixed effects and control for both push factors (VIX, CRB index) and pull factors (GDP deflator, exchange rate, external debt) that influence cross-border capital flows to EMEs. In columns (1)–(6), the coefficient of the interest rate variable is always negative and statistically significant at 5% level, ranging from −0.0070 to −0.0087 across models with increasing controls, indicating that U.S. monetary policy tightening significantly reduces capital inflows to emerging market economies. Specifically, a one standard deviation increase in U.S. interest rates would reduce net capital flows to EMEs by roughly 0.7 percentage points of GDP. The coefficients of most control variables are statistically insignificant, with only the CRB index showing significant effects. This significance stems from the CRB index’s direct influence on EMEs’ primary commodity export revenues and investor sentiment. These results suggest that domestic economic fundamentals and global risk factors have less impact on cross-border capital flows than the impact of U.S. monetary policy.

Table 4.

Baseline regression results. U.S. Monetary Policy and NCF to Emerging Markets: Baseline Two-Way Fixed Effects Results.

4.2. Robustness Tests

Following the baseline regression analysis, this study conducts multiple robustness checks to enhance the reliability of our findings, including the introduction of the lagged independent variable to control for potential endogeneity concerns, the substitution of interest rate variables with shadow rates to better capture monetary policy stance under zero lower bound constraints, and the inclusion of additional control variables to mitigate omitted variable bias.

First, we examine whether we still have predictive power for cross-border capital flows when the key explanatory variable, interest rates, is lagged by one period (T-1). The results demonstrate that the coefficient of the lagged U.S. interest rate variable remains −0.0091, achieving statistical significance and indicating that previous-period U.S. monetary policy exerts a significant negative influence on current-period capital inflows. More importantly, the inclusion of this lagged explanatory variable leaves the coefficient and significance level substantially unchanged compared to our baseline specification, suggesting that our baseline regression results are not significantly driven by reverse causality concerns.

Second, we use the shadow interest rate as a proxy variable studied by Krippner [38], to better measure the effectiveness of our regression model during periods when conventional interest rates are constrained by the zero lower bound. We find that, after replacing key explanatory variables, US monetary policy still has a significant negative impact on capital flows in emerging market economies. The regression coefficient for the shadow interest rate is −0.0106, demonstrating that our findings are robust to the choice of monetary policy indicator. This coefficient is approximately 22% larger in absolute magnitude compared to the conventional rate specification, suggesting that unconventional monetary policy (QE) may have stronger spillover effects than conventional rate adjustments alone.

Third, we augment the control variables to include the Geopolitical Risk Index (GPR), which captures the non-economic impact of international political uncertainty, and the domestic short-term interest rate (STR) to account for variations in country-specific monetary policy. The impact of U.S. monetary policy on capital flows is re-estimated. As shown in Column (3) of Table 5, the effect of U.S. monetary policy on capital flows reveals a statistically significant and robust coefficient of −0.0086 for the U.S. interest rate.

Table 5.

Robust tests.

Fourth, we address potential issues arising from extreme values by applying wilsonization to key variables. Following standard practice in financial econometrics [50], we wilsonize the dependent variable (NCF) and independent variables at the 1st and 99th percentiles. Subsequent to the implementation of this truncation procedure, a re-estimation of the baseline model was conducted. The coefficient of the U.S. interest rate variable retained its value of −0.0090, exhibiting no alteration in both its magnitude and statistical significance. This result confirms that our findings are not driven by extreme observations.

4.3. Moderating Effect Results

Using a moderation effect model (2), this section examines the moderating role of capital control in the relationship between U.S. monetary policy and cross-border capital flows to EMEs. The regression results are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Moderating effect of Capital Account Openness results.

According to columns (1)–(6), the interaction term between KAOPEN and the U.S. interest rate consistently yields a significantly negative coefficient. Substantively, a one standard deviation increase in the capital control intensity strengthens this protective effect, reducing the sensitivity of capital flows to U.S. monetary policy by approximately 0.12 percentage points of GDP. This result indicates that stronger capital controls help mitigate the negative impact of U.S. monetary tightening on EMEs’ capital inflows, suggesting a buffering capacity afforded by capital controls. This conclusion aligns with findings by [51]. This finding carries significant policy implications, suggesting that EMEs should exercise prudence in managing capital account liberalization, especially during periods of tightening external financial conditions or anticipated U.S. monetary policy contraction. The judicious and appropriate use of capital flow management measures may serve as a valuable tool to help buffer the adverse spillover effects associated with shifts in U.S. monetary policy, thereby helping maintain macroeconomic and financial stability.

4.4. Heterogeneity Results

To investigate the differential effects of conventional monetary policy (CMP) and unconventional monetary policy (UMP) on EMEs, we conduct a sub-period regression analysis. Following the Federal Reserve’s policy practices and the conventional/unconventional policy environment distinctions established by [52], we define the periods of 2008Q4–2014Q4 and 2020Q1–2022Q2 as UMP periods. The remaining periods are classified as CMP periods. While the quarterly data frequency imposes limitations on precise date-based delineation, these periods representatively capture the primary implementation intervals of these policy measures.

The results, presented in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 6, reveal a notable difference between the two periods. Specifically, the negative impact of the U.S. interest rate on EMEs’ capital inflows is substantially stronger during UMP compared to CMP periods. The coefficient is approximately four times larger in magnitude under UMP (−0.008) than under CMP (−0.002); in economic terms, a one standard deviation increase in the policy rate (or shadow rate) reduces net capital inflows by only 0.2 percentage points of GDP during CMP, but by 0.8 percentage points of GDP during the UMP episode. This indicates a more pronounced sensitivity of capital flows to changes in U.S. monetary policy during UMP periods.

This amplified effect can be attributed to several theoretical mechanisms. First, UMP carries enhanced signaling power compared to routine CMP adjustments, as unconventional measures send stronger signals about future economic conditions and policy persistence [25]. Second, UMP directly affects long-term yields and risk premiums across asset classes through large-scale asset purchases, creating more powerful portfolio rebalancing effects that drive investors to seek higher yields in emerging markets. Third, UMP contributes to a more synchronized global financial cycle, where capital flows become increasingly sensitive to global risk factors and monetary policy changes from major central banks [15].

To further examine the heterogeneous effects of U.S. monetary policy across different types of capital flows, we decompose net capital inflows into three subcomponents: Net FDI, Net Ptf. Inv., and Net Oth. Inv. Using model (1), we estimate the impact of changes in the U.S. federal funds rate on these three types of capital flows in emerging market economies. The regression results are presented in columns (3)–(5) of Table 7.

Table 7.

Heterogeneity regression results.

The coefficient on net FDI is statistically insignificant. In contrast, the coefficients on net Ptf. Inv. and net other investment are both negative and statistically significant at the 5% level. These findings indicate that portfolio and other investment flows are significantly more sensitive to changes in U.S. monetary policy than FDI, with the effect on other investment being approximately 2 times larger than the effect on portfolio investment. The reason for the above heterogeneous results lies in the characteristics of different capital flows. Portfolio and other investments exhibit higher volatility due to their inherent higher liquidity [53], making them more susceptible to changes in short-term returns and risk preferences caused by U.S. monetary policy. In contrast, foreign direct investment, driven by long-term strategic considerations [54], exhibits greater stability and is less susceptible to U.S. monetary policy shocks.

Employing a classification approach informed by the sample countries’ GDP per capita distribution (using the upper quartile as an initial threshold) and initially guided by the World Bank’s 2024 GNI per capita income classification criteria as reported by Our World in Data [55], we make necessary adjustments to ensure balanced representation for meaningful cross-group comparisons. The sample is accordingly divided into higher-income EMEs, including Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Poland, Russia, and Turkey (7 countries, representing the upper quartile of the sample distribution), and lower-income EMEs, including Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Hungary, Malaysia, Mexico, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, South Africa, Thailand, and Vietnam (12 countries, representing the remaining sample). While this classification deviates partially from strict World Bank income thresholds, it maintains the analytical rigor of using international standards as a reference point while ensuring sufficient observations in each group for robust econometric analysis.

Results presented in columns (6) and (7) of Table 7 reveal notable differences across income categories. The coefficient representing the impact of U.S. monetary policy on capital inflows is −0.0068 for high-income emerging markets versus −0.0148 for low-and middle-income emerging markets. This suggests that low-and middle-income EMEs experience substantially greater capital flow volatility in response to U.S. monetary tightening. This heterogeneous response across income groups reflects differences in financial market quality and macroeconomic stability. High-income emerging market economies typically have deeper domestic financial markets and a more comprehensive system, factors that together enhance their ability to absorb large swings in capital flows. In contrast, low-income emerging market economies, due to their greater reliance on external financing and relatively weaker economic fundamentals, are more vulnerable to capital flows. These findings are consistent with existing literature documenting differential capital flow volatility across income groups following adjustments in US monetary policy [5].

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Conclusions

This paper examines how changes in U.S. monetary policy influence net capital inflows to emerging market economies and their implications for financial sustainability. Three main findings emerge.

First, U.S. monetary tightening significantly reduces net capital inflows to EMEs. External monetary shocks from systemically important advanced economies are major determinants of cross-border capital flows in EMEs and can disrupt the stable financing conditions necessary for sustainable development.

Second, capital account openness amplifies the transmission of external monetary shocks to domestic financial markets. Countries with greater financial integration experience more pronounced capital flow volatility, while those with stronger capital are more insulated from U.S. monetary policy shocks. Capital flow management measures moderate external financial spillovers and preserve the financial stability essential for long-term growth.

Third, the estimated effects vary substantially across CMP versus UMP, capital flow types, and income levels. UMP phase-including quantitative easing and forward guidance-are associated with stronger spillover effects, which may reflect heightened market sensitivity and uncertainty during periods of non-standard central bank interventions. Portfolio flows and other short-term capital components demonstrate substantially greater sensitivity than foreign direct investment, reflecting their distinct liquidity characteristics and risk profiles as well as their differential contributions to sustainable economic development—with FDI supporting productive capacity and long-term growth while short-term flows often introduce destabilizing volatility. Low- and middle-income EMEs experience larger adverse effects than high-income counterparts, indicating that financial depth, institutional quality, and macroeconomic fundamentals determine shock absorption capacity and the ability to maintain sustainable development under external financial pressures.

5.2. Implications

Several policy implications emerge for EMEs seeking to strengthen resilience and advance financial sustainability under volatile global financial conditions.

First, capital controls should function as integral components of a comprehensive macro-financial stability framework that complements monetary, fiscal, and prudential policies in support of sustainable development objectives. The empirical evidence demonstrates that economies with stronger capital control regimes experience smaller capital outflows in response to U.S. monetary tightening, underscoring the stabilizing role of strategic capital flow management in maintaining the continuous access to financing that sustainable development requires. Policymakers should adopt dynamic and countercyclical CFMs that can be flexibly adjusted in response to global liquidity cycles—tightening during excessive inflows to prevent overheating and relaxing during sudden stops to sustain liquidity. Such an adaptive policy framework can enhance systemic resilience while preserving the long-term benefits of financial openness and integration, thereby supporting both stability and sustainable transformation.

Second, sustainable financial systems should promote efficient and environmentally responsible investment, not merely stabilize flows. Short-term capital is more sensitive to U.S. policy shocks than long-term FDI, highlighting the need for differentiated treatment across capital types based on their contributions to sustainable development. EMEs could adopt targeted measures that discourage speculative and volatile inflows while incentivizing stable, sustainability-oriented investments. Examples include imposing higher reserve requirements or transaction taxes on short-term portfolio inflows and offering preferential financing or tax incentives for green infrastructure, clean technology, and inclusive growth projects. Aligning capital flow management with sustainable development objectives achieves dual goals: mitigating financial instability while supporting structural transformation toward low-carbon, resilient growth.

Third, institutional capacity and domestic financial development remain central to building long-term resilience. High-income EMEs are more resilient to external monetary shocks due to deeper financial markets, broader investor bases, and stronger policy credibility. For low- and middle-income EMEs, improving market depth, governance quality, and transparency is essential for creating stable conditions that attract long-term sustainable investment. Strengthening local bond and equity markets, enhancing financial literacy, and developing credible monetary and fiscal institutions reduce dependence on volatile foreign funding. These measures improve shock absorption capacity and contribute to a more inclusive, sustainable financial ecosystem capable of supporting long-term development aligned with environmental, social, and governance principles.

Fourth, greater international coordination is indispensable for ensuring a stable and sustainable global financial environment. Given the systemic spillover effects of U.S. monetary policy, EMEs should actively engage in multilateral platforms—the IMF, G20, and regional financial arrangements—to advocate for global frameworks that internalize cross-border spillovers and improve transparency in policy communication while promoting sustainable finance standards and climate-related financial risk management. Domestic regulators should integrate sustainability and climate considerations into macroprudential and capital flow management frameworks. Central banks can incorporate climate-related financial risks into stress testing and capital adequacy assessments, ensuring that short-term financial stability measures are consistent with long-term environmental and social sustainability objectives and contribute to the global transition toward a resilient, low-carbon economy.

6. Discussion

6.1. Overview and Contribution

U.S. monetary tightening reduces EMEs’ NCF in economically meaningful magnitudes. In the fully controlled specification (Table 4, col. 6), the policy-rate coefficient is −0.0087 (t = −3.24): a 100 bp increase lowers quarterly NCF by 0.87% of GDP (95% CI: −1.40% to −0.34%), roughly 0.41 within-country SDs given a dispersion of ≈2.1%. Effects are small during CMP (≈−0.002; 95% CI: −0.47% to +0.07%) but large and precise under UMP and post-COVID normalization (≈−0.008; 95% CI: −1.44% to −0.16%); including one lag preserves significance (Interest Rate (T–1) ≈ −0.0091; t = −2.64). Results are similar to the shadow short rate (≈−1.06% per 100 bp; 95% CI: −1.59% to −0.53%) [38].

The study offers an EME-centered, disaggregated account of transmission that: (i) identifies which flow components adjust—portfolio and bank-intermediated other investment, while FDI is comparatively stable; (ii) demonstrates state contingency—stronger transmission under UMP than CMP; (iii) documents systematic income-group heterogeneity, with effects about twice as large in low/lower-middle-income EMEs; and (iv) examines policy interaction, showing that more restrictive de jure capital-account regimes are associated with smaller pass-through. These results situate the paper within the global financial-cycle literature [5,10,15] while clarifying when and through which channels U.S. policy matters for EMEs, where evidence remains thinner than for advanced economies [5,15,16,17,18].

6.2. Economic Magnitudes and Heterogeneity

Disaggregation clarifies policy-relevant magnitudes. Portfolio (≈−0.25% of GDP per 100 bp; 95% CI: −0.46% to −0.04%) and other investment flows (bank-intermediated; ≈−0.55%; 95% CI: −0.92% to −0.18%) drive the aggregate response, whereas FDI is small and statistically insignificant (≈−0.07%). Hence, a 100 bp tightening typically induces ≈0.8% of GDP reversals in the volatile components—sufficient to create exchange-market pressure and motivate FX reserve sales or domestic rate hikes in more vulnerable EMEs. By income group, effects are ≈−1.48% per 100 bp (95% CI: −2.10% to −0.86%) for low/lower-middle-income EMEs versus ≈ −0.68% (95% CI: −1.32% to −0.04%) for higher-income EMEs [56], consistent with differences in market depth and policy space. These patterns help explain heterogeneous findings in prior work: when hikes mainly convey favorable demand/information, growth channels can offset tighter financial conditions [3,31,32]; when balance-sheet contraction and uncertainty dominate, risk-off and liquidity-withdrawal channels generate larger adverse spillovers [5,26,27,54,56,57].

6.3. Capital-Control Moderation: De Jure Measurement and Endogeneity

Capital-account restrictiveness is proxied by KAOPEN [48], constructed from the IMF’s AREAER. KAOPEN summarizes the legality (de jure) of restrictions; it does not measure enforcement intensity or effectiveness. Jurisdictions may appear restrictive on paper yet apply rules leniently—or maintain strict enforcement despite formal liberalization. This de jure de facto gap cautions against treating KAOPEN as a sufficient statistic for effective controls and can attenuate—or bias—interaction estimates if enforcement varies within or across countries. A practical refinement is to complement KAOPEN with policy-action-level CFM datasets (measure-by-measure records and effective dates) or proxies for enforcement (e.g., residency-based frictions, transaction limits, administrative intensity).

A second issue is identification in H2. Capital controls can respond to contemporaneous flow pressures: during U.S. tightening, outflows may prompt tighter controls, generating reverse causality in the moderation term. Country fixed effects and KAOPEN’s slow-moving nature reduce—but do not eliminate—this concern. We therefore interpret the interaction as a robust conditional association—historically stricter de jure regimes correlate with smaller pass-through—rather than a definitive causal effect. A path to stronger identification is IV/2SLS, exploiting institutional timing/diffusion (clustered legal updates, peer adoption), supranational rollouts/standards, or domestic political clocks; combined with action-level CFM data, these strategies help separate policy supply from flow-driven demand for controls.

6.4. Policy Implications and Sustainable Financial Stability

Given where sensitivity concentrates, policy should prioritize macroprudential tools and liquidity backstops targeted at portfolio and bank-intermediated segments, while preserving openness to FDI, which supports productive capacity and medium-term growth [22,35]. The documented UMP–CMP asymmetry suggests that backstops and capital-flow management are most valuable when balance-sheet and expectations channels are active. Aligning these tools with sustainable financial stability means damping volatile inflow components while safeguarding long-duration (including green) investment needs that are central to transition financing [58].

6.5. Limits of Causal Interpretation and Avenues for Improvement

The evidence should be read as conditional associations, not structural causal effects. Constraints arise from: (i) policy endogeneity in capital-control settings and potential reverse causality; (ii) omitted/time-varying confounders (macroprudential moves, FX intervention, fiscal stance, global risk appetite) imperfectly observed at quarterly frequency; (iii) measurement error—KAOPEN does not capture enforcement; and (iv) simultaneity/dynamics as authorities may react within the quarter. Fixed effects, rich controls, regime stratification (CMP/UMP), lags, and the shadow-rate proxy mitigate but do not eliminate these issues. Future work could deploy high-frequency U.S. surprises, policy-action-level CFM data, and IV-based moderation to strengthen causal interpretation.

Bottom line. U.S. tightening reduces EMEs’ NCF on impact—especially via portfolio and bank-related channels—with stronger effects under UMP and for lower-income EMEs, while FDI remains broadly stable. De jure restrictiveness is associated with smaller pass-through, but establishing causality requires richer enforcement data and stronger identification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.L. and X.L.; methodology, T.L. and L.L.; software, T.L.; validation, T.L., L.L. and X.L.; formal analysis, T.L.; investigation, T.L. and L.L.; resources, X.L.; data curation, T.L.; writing—original draft preparation, T.L.; writing—review and editing, T.L., L.L. and X.L.; visualization, T.L.; supervision, X.L.; project administration, X.L.; funding acquisition, X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Youth Fund for Humanities and Social Science Research of the Ministry of Education of China (Name: Study on the Long-term Mechanism for Alleviating Relative Poverty in the Child Education Poverty Alleviation Project) [No. 21YJC880043].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EMEs | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| UMP | unconventional monetary policy |

| CMP | conventional monetary policy |

| NCF | Ner Capital Flows |

References

- Bhattarai, S.; Chatterjee, A.; Park, W.Y. Effects of US Quantitative Easing on Emerging Market Economies. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 2021, 122, 104031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamizar-Villegas, M.; Arango-Lozano, L.; Castelblanco, G.; Fajardo-Baquero, N.; Ruiz-Sanchez, M.A. The Effects of Monetary Policy on Capital Flows: An Emerging Market Survey. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2024, 62, 101167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Economic Letter 2021. Available online: https://www.dallasfed.org/research/economics/2021/0810 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Rey, H. International Channels of Transmission of Monetary Policy and the Mundellian Trilemma; NBER Working Paper 21852; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda-Agrippino, S.; Rey, H. US monetary policy and the global financial cycle. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2020, 87, 2754–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Why did Turkey and Argentina seek IMF assistance in 2018? Econ. Synop. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, S.; Eggertsson, G.B.; Gafarov, B. Effects of US Quantitative Easing on Emerging Market Economies; Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas location: Dallas, TX, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrian, T.; Xie, W. Monetary Policy Spillovers and the Global Financial Cycle; IMF Working Paper WP/22/114; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, J.; Kose, M.A.; Ohnsorge, F. Inflation in Emerging and Developing Economies: Evolution, Drivers, and Policies; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund. Global Financial Stability Report: Preempting a Legacy of Vulnerabilities; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gelos, G.; Miyajima, K.; Zhang, Y. Capital Flows at Risk: Taming the Ebb and Flow; IMF Working Paper WP/22/140; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chamon, M.; Kaplan, E. The iceberg theory of campaign contributions: Political threats and interest group behavior. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2013, 5, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, I.; Shah, A.; Singh, N. Foreign investors under stress: Evidence from India. Int. Financ. 2013, 16, 213–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostry, J.; Ghosh, A.R.; Habermeier, K.; Chamon, M.; Qureshi, M.S.; Reinhardt, D.B. Capital Inflows: The Role of Controls; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Rey, H. Dilemma Not Trilemma: The Global Financial Cycle and Monetary Policy Independence; NBER Working Paper 21162; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, K.J.; Warnock, F.E. Capital flow waves—Or ripples? Extreme capital flow movements since the crisis. J. Int. Money Financ. 2021, 116, 102394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizenman, J.; Jinjarak, Y.; Park, D. Fundamentals and sovereign risk of emerging markets. Pac. Econ. Rev. 2016, 21, 151–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obstfeld, M. Financial flows, financial crises, and global imbalances. J. Int. Money Financ. 2012, 31, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheubel, B.; Stracca, L.; Tille, C. The global financial cycle and capital flows: Taking stock. J. Econ. Surv. 2025, 39, 219–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelos, G.; Patelli, P.; Shim, I. The US dollar and capital flows to EMEs. BIS Q. Rev. 2024, 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund. Emerging Market Resilience: Good Luck or Good Policies? World Economic Outlook 2025. Available online: https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/WEO/2025/October/English/ch2.ashx (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Forbes, K.J.; Warnock, F.E. Capital flow waves: Surges, stops, flight, and retrenchment. J. Int. Econ. 2012, 88, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M.W.; Shambaugh, J.C. Rounding the corners of the policy trilemma: Sources of monetary policy autonomy. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 2015, 7, 33–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, R.; Aalbers, M.B. Financialization and housing: Between globalization and varieties of capitalism. Compet. Change 2016, 20, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratzscher, M. Capital flows, push versus pull factors and the global financial crisis. J. Int. Econ. 2012, 88, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Akinci, O.; Queralto, A. U.S. Monetary Policy Spillovers to Emerging Markets: Both Shocks and Vulnerabilities Matter; International Finance Discussion Papers 1321r1; Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Akinci, O.; Queralto, A. U.S. Monetary Policy Spillovers to Emerging Markets: Both Shocks and Vulnerabilities Matter; Staff Report No. 972; Federal Reserve Bank of New York: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallaro, E.; Cutrini, E. Institutional quality and cross-border asset trade: Are banks less worried about diversification abroad? In Università degli Studi di Roma-La Sapienza Collana WP-Dipartimento di Economia Pubblica; La Sapienza: Rome, Italy, 2018; ISSN 1974–2940. [Google Scholar]

- Ranciere, R.; Tornell, A.; Vamvakidis, A. A New Index of Currency Mismatch and Systemic Risk; IMF Working Paper WP/10/263; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fisera, B.; Workie Tiruneh, M.; Yin, H. Currency depreciations in emerging economies: A blessing or a curse for external debt management? Int. Econ. 2021, 168, 132–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, J.; Kamin, S.; Yoldas, E. Are higher U.S. interest rates always bad news for emerging markets? J. Int. Econ. 2022, 137, 103585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakdawala, A. The growing impact of US monetary policy on emerging financial markets: Evidence from India. J. Int. Money Financ. 2021, 119, 102482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Prabheesh, K.P. Do capital controls absorb global financial shocks? Evidence from emerging market economies. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2024, 39, 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Meng, J.; Ren, J.; Zhang, L. The impact of capital inflow’s features on the effectiveness of capital controls—Evidence from multinational data. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 93, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erten, B.; Korinek, A.; Ocampo, J.A. Capital controls: Theory and evidence. J. Econ. Lit. 2021, 59, 45–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund. Balance of Payments Statistics. Available online: https://data.imf.org/?sk=7A51304B-6426-40C0-83DD-CA473CA1FD52 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED): Effective Federal Funds Rate. Available online: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/EFFR (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Krippner, L. Measuring the stance of monetary policy in zero lower bound environments. Econ. Lett. 2013, 118, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE). VIX Index Historical Data. Available online: https://www.cboe.com/tradable-products/vix/vix-historical-data (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- World Bank. World Development Indicators. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- International Monetary Fund. International Financial Statistics. Available online: https://data.imf.org/IFS (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Hamilton, J.D. The daily market for federal funds. J. Polit. Econ. 1996, 104, 26–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernanke, B.S.; Mihov, I. The liquidity effect and long-run neutrality. In Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; Volume 49, pp. 149–194. [Google Scholar]

- Anaya, P.; Hachula, M.; Offermanns, C.J. Spillovers of US unconventional monetary policy to emerging markets: The role of capital flows. J. Int. Money Financ. 2017, 73, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.S.; Zlate, A. Real Exchange Rates and the Global Financial Cycle; Working Paper No. 2416; Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas: Dallas, TX, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ilzetzki, E.; Reinhart, C.M.; Rogoff, K.S. The Country Chronologies to Exchange Rate Arrangements into the 21st Century: Will the Anchor Currency Hold? NBER Working Paper 23135; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017.

- Chui, M.; Kuruc, E.; Turner, P. Leverage and currency mismatches: Non-financial companies in the emerging markets. World Econ. 2018, 41, 3269–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.S.; Zlate, A. Monetary policy divergence and net capital flows: Accounting for endogenous policy responses. J. Int. Money Financ. 2019, 94, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinn, M.D.; Ito, H. What matters for financial development? Capital controls, institutions, and interactions. J. Dev. Econ. 2006, 81, 163–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cerdeiro, D.A.; Komaromi, A. Financial openness and capital inflows to emerging markets: In search of robust evidence. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2021, 73, 444–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matschke, J.; von Ende-Becker, A.; Sattiraju, S.A. Capital flows and monetary policy in emerging markets around Fed tightening cycles. Econ. Rev. 2023, 108, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlhaus, T.; Vasishtha, G. Monetary policy news in the US: Effects on emerging market capital flows. J. Int. Money Financ. 2020, 109, 102251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koepke, R. Fed policy expectations and portfolio flows to emerging markets. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2018, 55, 170–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- OECD. Supporting Emerging Markets and Developing Economies in Developing Their Local Capital Markets; OECD Policy Briefs No. 24; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. G20/OECD Report on Assessing and Promoting Capital Flow Resilience in Emerging Markets and Developing Economies; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Alessi, L.; Di Girolamo, E.F.; Pagano, A.; Giudici, M.P. Accounting for climate transition risk in banks’ capital requirements. J. Financ. Stab. 2024, 73, 101269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).