Abstract

The integration of biomimetics and artificial intelligence (AI) in architecture is reshaping the foundations of computational design. This paper provides a comprehensive review of the current research trends and applications that combine AI-driven modeling with biologically inspired principles to optimize architectural forms, material efficiency, and fabrication processes. By examining recent studies from Q1–Q2 journals (2019–2025), the paper identifies five primary “interfaces” through which AI expands the field of biomimetic design: biological pattern recognition, structural optimization, generative morphogenesis, resource management, and adaptive fabrication. The paper highlights the transition from conventional simulation-based design toward iterative, data-driven workflows integrating machine learning (ML), deep generative models, and reinforcement learning. The findings demonstrate that AI not only serves as a generative tool but also as a learning mechanism capable of translating biological intelligence into architectural logic. The paper concludes by proposing a methodological and educational framework for AI-driven biomimetic optimization, emphasizing the emergence of Artificial Intelligence in Architectural Design (AIAD) as a paradigm shift in architectural education and research. This convergence of biology, algorithms, and material systems is defining a new, adaptive approach to sustainable and intelligent architecture.

1. Introduction

The superposition of biomimicry and artificial intelligence in architecture opens up new ways of optimising shape, mass, material consumption, and manufacturing methods. On the one hand, mature paradigms inspired by nature are visible: from adaptive facades to hierarchical materials. For example, biomimetic adaptive facade designs show that it is possible to change the geometry of a partition in relation to external conditions and reduce energy losses [1]. On the other hand, there is a growing repertoire of methods based on Machine Learning (ML), designed to predict structural responses and control the generative design process. Artificial Intelligence in Architectural Design (AIAD) in structural engineering illustrates that ML techniques can generate innovative structural systems and optimise the multi-criteria design process [2]. Recent trends in the literature show that biomimetic coatings and bio-adaptive solutions can effectively reduce energy losses and switch the functions of building envelopes while at the same time requiring the systematisation of methods and taxonomy for transferring biological principles into the AEC sector practice (which is one of the main conclusions from studies analysing the evolution of adaptive facades) [3,4]. Understanding modern tools supporting architectural design is becoming an essential skill for architects, designers, materials technologists, and materials contractors [5].

The 21st century has seen a significant increase in the use of artificial intelligence in biomimetic contexts, particularly where the aim is to optimise form, structure, material and manufacturing processes in architectural designs. AI is increasingly playing the role not only of a generator of variants but also of an ‘intelligent filter’, selecting biological patterns, parameterising them, and adapting their variants to structural, material, and production constraints. In practice, growth is visible in several parallel areas that are key fields for the integration of biomimetics with ML/AI:

- Generative AI models (GAN, VAE, diffusion models) are now used to create biomimetic geometries, which can then be optimised for increased load-bearing capacity or weight optimisation. A review of the research shows that generative models are increasingly being adapted to design stages—from loading biological patterns to generating spatial variants—and incorporated into iterative optimisation processes [6,7,8].

- AI integrates with BIM/IA systems, creating BIM + AI (or BIM + ML) hybrids in which the building information model becomes input for optimisation algorithms. This integration enables the automatic generation of structural or material variants without manual data transfer between platforms. One recent project, ‘Generative AIBIM,’ demonstrates a pipeline that integrates BIM with AI in structural design, using a diffusion model conditioned by physical constraints [5,9].

- AI supports topological and multi-criteria optimisation in the context of biomimetics, for example, through surrogate modelling, which accelerates optimisation iterations, or by combining predictive architecture with FEM analyses. In some studies, artificial intelligence acts as a ‘meta-optimiser’ layer, controlling the geometry generator based on feedback from simulations.

- In the field of fabrication, we are increasingly encountering AI-controlled adaptive processes, ML-controlled robots, and algorithms for translating biological patterns into machine motion trajectories (e.g., 3D printers, industrial robots) in the context of biomimetic geometry. Work on generative morphologies for 3D printing shows how AI can coordinate geometry, material constraints, and manufacturing strategies in a single workflow [10,11,12,13].

At the same time, in structural engineering, ML methods have become the tool of choice for prediction, identification, and optimisation, from surrogate learning for expensive simulations to topology automation. The literature emphasises that deep networks, Gaussian processes, and reinforcement learning reduce computational costs and facilitate multi-criteria optimisation, while reviews in the field of ML-assisted topology optimisation already organise typical schemes (iterative and non-iterative) and research gaps, including generalisation to 3D and coupling with constraints [9].

For decades, biomimicry has been an experimental and cognitive tool for architecture, translating the principles of matter organisation in nature into design, construction and material strategies. Frei Otto studied the natural processes of structure formation, recognising minimal surface area and optimal flow of forces as the common denominator of organic forms and engineering structures. Stéphane du Château developed ideas of self-organisation in spatial structures, showing that geometric simplicity can result from biological logic. Janine Benyus popularised the term ‘biomimicry’ as a systemic approach to design in accordance with the principles of nature. Neri Oxman and Achim Menges expanded this field by combining biological simulations with digital fabrication, material design, and structural parameterisation (examples in the literature show that material ecology aims to blur the boundaries between material and biological form) [14,15]. Skylar Tibbits introduced self-assembling architecture: a design in which the process of spatial transformation becomes part of the construction strategy. In this context, AI appears not so much as an external technology but as a ‘design microscope’ capable of analysing, classifying, and translating complex patterns of nature into parameterisable design representations. As a result, biomimicry ceases to be the domain of aesthetic analogies and becomes a quantitative tool. In recent years, there has been a growing body of work showing that AI supports generative processes in architecture (e.g., GAN models, VAEs, diffusion models) and can guide the exploration of design spaces. The literature emphasizes that the integration of AI with biomimetic methods leads to so-called data-driven biomimetic optimization: the selection of biological patterns, the prediction of structural behavior, and the generation of parametric structures that comply with material and manufacturing constraints [16].

This article aims to demonstrate how contemporary artificial intelligence tools (ML, LLM, generative algorithms, neural networks) can not only inspire but also co-create and optimize the biomimetic process in architecture, from the analysis of natural patterns to structural, energy, and material optimization and their digital prefabrication. On the one hand, the article is review-based (systematising existing works from the last 10–15 years). On the other hand, it is interpretative, pointing to new areas of integration that have not yet been sufficiently described (e.g., generative collaboration between LLMs and the designer, learning biological patterns from environmental data, intelligent prefabrication planning). The article will explore this trend, demonstrating that the combination of biomimetics and AI can lay the foundation for a new architectural paradigm. This design process resembles nature’s processes: adaptive, iterative, and based on the interplay between form, material, and environment.

1.1. Biomimetics and Bionics in Architecture: Development Trends

The following section presents the use of biomimicry in architecture as a pluralistic field: from form-shaping strategies and processes to materials and increasingly frequent close cooperation between them. In the organic literature [15] there is a strong trend towards problematising the taxonomy and definition of biomimetics, which makes comparisons between fields difficult [15]. Reviews of façades emphasise that many conceptual designs do not take into account structural and manufacturing constraints [3]. In the field of materials, current work on lattice and hierarchical materials shows strong potential for integration with digital fabrication techniques.

In architectural and engineering design, three main groups of biomimetic strategies can be distinguished (Table 1). The approach where geometric patterns serve as the primary inspiration for solids and structures (morphology, shell, network, fibrous, and lattice structures) is most often referred to as biomimicry of form. Another approach concerns growth mechanisms, self-organisation, adaptation to environmental conditions, and adaptive systems that can reorganise themselves in response to stimuli, known as process biomimetics. The last type of processes are nature-inspired strategies in the field of materials, hierarchical structures, gradient material transport, composites, and multifunctional materials.

Table 1.

Strategies, examples of characteristics and selected implementations (or research projects).

Table 2 lists ten representative examples of biomimetic objects and installations completed in recent years within the research and design environment. This table aims to organise various biomimetic strategies according to the type of imitation (form, process, material, or combinations thereof) and to show how biological inspirations are transferred in practice to the level of design, optimisation, and manufacture of architectural structures. The table also serves as a starting point for further analysis of the possibilities of integrating artificial intelligence methods with biomimetic design and fabrication processes. Organising the examples in terms of the type of biomimicry, the material used, the mechanism of action and the architectural significance facilitates the identification of research gaps. It thus defines areas where AI algorithms can perform an optimising or predictive function.

1.1.1. Biomimetic and Structural Forms

In the field of architectural form, numerous works showcase adaptive coatings, structures, advanced geometries and biomimetic networks. Sommese et al. (2022) present a critical review of nature-inspired climate-adaptive facades and point out that many solutions remain more conceptual than implemented [17]. Bijari et al. (2025) analyse plant-inspired biomimetic technologies that influence both the form and energy efficiency of buildings [18]. In the literature, Dixit (2023) discusses the evolution of nature-inspired architecture in ‘Bio-logic’—showing examples where nature provides the matrix for structural and aesthetic form [19]. Projects such as the ICD/ITKE Pavilion (from the University of Stuttgart) and designs by Menges and Oxman illustrate how biomimetic form has been put into practice.

1.1.2. Biomimetic Processes

Process approaches in which architecture ‘grows’ or changes over time are becoming increasingly common thanks to sensors and automation. Interactive façade systems and adaptive structures, although still in the research phase, demonstrate this trend. In the literature, AlAli et al. (2023) describe mechanisms of adaptation, thermoregulation and environmental feedback as central areas for further research [20]. Work on self-assembling architectures in design laboratories (including Tibbits) combines conceptual designs with the potential for adaptation at the material and structural levels.

1.1.3. Biomimetic Materials

This is an area where inspiration from nature is powerful—hierarchical structures (micro → macro), component gradients and functional composites. Examples of inspiration include nacre shells, bone, wood, and natural structures with a high strength-to-weight ratio. The paper ‘Hierarchical bioinspired architected materials and structures’ (2023) discusses lattice materials with a hierarchical structure that offer synergistic properties (lightness, damping, resistance) thanks to their multiscale organization [21]. Rohner (2022) describes classifications of biomimetic materials (e.g., inspired by process, function, structure) and implementation challenges in the construction sector in a review of biomimetic materials in construction [22]. The study ‘Biomimetic Materials in Our World: A Review’ also describes the diversity of hierarchical materials inspired by nature and their functions [23].

1.1.4. ICD/ITKE Research Pavilion (2009–2019, Stuttgart University) [24]

The ICD/ITKE research pavilions are one of the most well-known studies on the application of biomimicry principles in architectural design. Each edition of this series was based on the analysis of a biological model—from the structure of crustaceans to the morphology of cellulose fibres in plant organisms—and its translation into geometric and structural parameters. The structures were created using digital modelling, physical simulations and robotic fabrication of fibre composites (e.g., glass and carbon fibres in 2016).

An example is the ICD/ITKE Pavilion 2016–17, inspired by the exoskeleton structure of the Elytra beetle. In this project, chitin microstructures were scanned, and their geometry was reconstructed in Rhinoceros 5 using the Grasshopper software plugin [24]. The data was then used to control a robotic arm that wound fibres in a way that mimicked natural stresses [24].

These pavilions showed that the principles of biological organisation (hierarchy, fibre directionality, adaptation to external forces) can be translated into structural logic, and that the design process can combine biological analysis, generative parameterisation and digital prefabrication [25].

1.1.5. Hylozoic Ground (2010, Philip Beersley, Canada) [26]

The Hylozoic Ground installation is an example of biomimicry of processes and behaviours. The project combines elements of responsive architecture, synthetic biology and artificial intelligence. The structure, built of lightweight acrylic modules, microsensors, and actuators, reacts to human presence through vibrations, changes in light, and air flow.

The inspiration for this project was the metabolic processes in living organisms: energy exchange, reactivity, and adaptability. Here, architecture becomes an organism that reacts to its environment, rather than a static object. The technical solutions used (sensor networks and micro-control systems) form the basis for so-called ‘bio-responsive’ architecture, in which information flows replace traditional material relationships [26]. From a scientific point of view, Beesley’s installation demonstrates the potential of process biomimicry, not only replicating the shapes found in nature, but also simulating biological behaviour [27].

1.1.6. Deep Surface (2008, Orkan Telhan & Philip Beesley) [17]

The Deep Surface project represents an early stage of exploration of interactive architectural coatings inspired by the principles of tissue organisation and microscopic biological structures. The surface, constructed from modular components, reacted to light and movement by changing its tension and transparency.

Ideologically, the project referred to the concept of ‘living skin’, a dynamic boundary between the external and internal environments that can adapt to the surrounding conditions. This concept has a direct translation into contemporary research on adaptive bio-inspired coatings and facades that use photoreactive polymers [17].

Table 2.

Overview of selected biomimetic projects and installations in architecture, classified by type of imitation and mechanism of action.

Table 2.

Overview of selected biomimetic projects and installations in architecture, classified by type of imitation and mechanism of action.

| Project/Installation | Biomimetic Type | Key Mechanism | What Does This Illustrate in the Context of Architecture? |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICD/ITKE Research Pavilion 2013–14: Modular Coreless Filament Winding (Beetle Elytra) [28] | form + material | coreless fibre winding inspired by beetle wings (elytra) | translation of fibre logic into a lightweight shell structure |

| ICD/ITKE Research Pavilion 2014–15: Fibre Placement on Pneumatic Mould [29] | form + material | reinforcing pneumatic moulds with fibres (imitating plant and animal networks/nests) | material-efficient coating shaped by the process |

| ICD/ITKE Research Pavilion 2016–17: Composite Lattice Cantilever [30] | form + material | truss, composite console wound core-free | integration of design, MES and robotics in a biology-inspired structure |

| BUGA Wood Pavilion (2019) [31,32] | form + material + process | segmented wooden cladding (hollow cassettes), integrative design optimisation and detailing of the segmented cassette system | integration of design, MES and robotics in a biology-inspired structure; scaling biomimetics to a functional object; workflow from optimisation to prefabrication |

| BUGA Fibre Pavilion (2019) [33] | form + material | fibre networks, computational co-design and composite fabrication | combining geometry, detail and performance |

| Maison Fibre (2021) [34] | form + material | hybrid FRP-wood system manufactured using coreless winding | long spans made of fibrous components, co-design of material-form-fabrication |

| FlexMaps Pavilion (2020) [35] | form + process | ‘bending-active’—controlled deformation of panels through local mesogeometry | first multi-storey structure made of fibre components; experimental validation |

| FIBERBOTS [36] | Process + material | a swarm of autonomous fibre winding robots (composite tubes) | shape optimisation pipeline through elastic properties and FEM |

| Hylozoic Ground [27] | process (responsivity) | ‘living’ sensor-actuator tissue; bio-responsive coating | równoległa, adaptacyjna fabrykacja struktur fibrowych w skali architektonicznej |

1.1.7. Silk Pavilion (2013, MIT Media Lab/Neri Oxman) [36]

The Silk Pavilion is an example of material biomimicry and cooperation between humans, machines, and biological organisms. The installation consists of a metal frame with a substructure stretched over it, on which silkworm larvae (Bombyx mori) wove a cocoon-like structure. The project combined robotic fibre weaving with the biological process of formation.

Oxman’s experiment aimed to explore the possibility of creating hybrid manufacturing systems in which design is achieved through the control of environmental conditions rather than direct modelling of form. The structure of the silk, analysed using micro-tomography, was later used to model gradient materials with variable fibre density.

This project illustrates how material biomimetics can intersect with robotics and machine learning to create complex nature-inspired manufacturing systems that are increasingly being used in research at the intersection of architecture.

The above examples represent another aspect of the development of biomimicry in architecture. The ICD/ITKE research pavilions at the University of Stuttgart (2013–2019) illustrate the transition from morphological imitation of biological structures to integration with digital fabrication and numerical modelling. Projects such as the BUGA Wood Pavilion and BUGA Fibre Pavilion show that nature-inspired principles can be applied in full-scale projects, not just in demonstrators. Other examples, such as Maison Fibre and FlexMaps Pavilion, focus on optimising form based on material properties and controlling the deformation process, i.e., bending-active systems.

In turn, the FIBERBOTS and Hylozoic Ground installations represent the biomimetics of processes and behaviours. In the first case, we are dealing with an autonomous system of robots co-creating a structure from composite fibres, and in the second, with responsive architecture that reacts to environmental stimuli in real time. Both examples expand the concept of biomimetics to include machine learning and artificial intelligence in the process of controlling material and shape.

1.2. AI-Driven Biomimetic Frameworks

Contemporary research on AI in architecture is gradually shifting its focus from generating geometric variants to systems that learn to design by analysing, predicting, optimising and adapting structural forms based on data. In this context, AI-driven biomimetic optimisation combines biological knowledge, machine learning and the design process, aiming to develop architectural structures inspired by nature but optimised for technical conditions and performance.

One of the most frequently studied areas is optimal topology supported by ML/deep learning. Traditional optimal topology uses the Finite Element Method (FEM) and iterative optimisation algorithms, which can be very computationally expensive. In recent years, ML models have been increasingly proposed as tools to accelerate these processes. For example, Senhora et al. (2022) used a convolutional neural network with residual links to predict sensitivities in topological optimisation tasks, achieving up to a 30-fold acceleration in computation without loss of accuracy [37]. Another essential review, ‘Topology Optimisation via Machine Learning and Deep Learning’ (Shin et al. 2023), discusses several hybrid methods (e.g., supplementing classical optimisation with ML, accelerating iteration stages, surrogate models) and points out limitations, such as generalisation between geometric domains [38]. In addition to topology, generative models are widely used in architecture, both in formal generation and in the synthesis of nature-inspired variants. Li et al. (2024) discuss the application of GANs, VAEs, diffusion models (DDPMs) and generative 3D models in various stages of architectural design, from the generation of conceptual schemes to final solid models [6]. In practice, an example is the work Generative AI-powered architectural exterior conceptual design (2024), which combines text prompting, sketches, and diffusion models to generate façade concepts based on input data. The article provides a framework for linking design intent with geometric generation [39]. Similarly, the review Generative AI in architectural design: Application, data, and challenges (2025) analyses how generative models are becoming an analytical tool in design (i.e., not just visualisations, but the generation of criteria-related metrics) and identifies implementation barriers such as domain data scarcity and difficulties in interpreting models [40].

Among hybrid techniques, the integration of supervised/unsupervised learning with the design process is attracting increasing attention. Autoencoder models and latent networks are used to compress the geometry of biomimetic structures (e.g., biological micro-scans) into feature representations, which can then be used as inputs for optimisation algorithms. Li et al. (2024) point to such applications in the context of generative steps in the design process [6]. Reinforcement learning (RL) also appears in some studies, especially in adaptive problems, where an agent makes successive decisions about geometric changes in response to simulated environmental conditions. Although specific applications of RL in biomimetic architecture are rare, reviews of AI in architecture mention this possibility as a future direction (e.g., ‘The role of artificial intelligence (AI) in architectural design’, 2025) [41].

In recent years, there has been a clear shift from AI used solely for generative design towards systems that learn, select, predict, and control design parameters—also based on biological and environmental data. In this sense, AI is becoming a genuine factor in biomimetic optimisation, rather than just an automatic sketchbook.

Below is an overview of AI/ML methods currently used as the most common techniques in design and optimisation:

- Neural networks (NNs/deep learning)

In the context of topological structural optimisation, deep neural networks are used to predict sensitivities, replace costly FEM calculations, and accelerate the optimisation process. Example: Senhora et al. (2022) describe a network architecture with convolutional layers for predicting material sensitivities in 3D topology [37]. Another example is the work ‘Machine-learning assisted topology optimisation for architectural design with artistic flavour’ by Zhang et al. (2023), which integrates geometric stylisation with structural optimization [42].

- Supervised learning and unsupervised learning

In architecture, supervised learning may involve training models on biological structure parameters (e.g., bone microtomography, tissue pores) and then predicting mechanical or experimental metrics. Unsupervised learning (e.g., autoencoders) is sometimes used to extract morphological patterns and reduce data dimensions—they can serve as an indirect representation of ‘biological aesthetics’ in the optimisation process. In their review, Li et al. (2024) discuss the VAE model and other generative techniques that often combine supervised and unsupervised aspects [6]

- Evolutionary algorithms/stochastic algorithms

In generative design, genetic algorithms, swarm algorithms, and simulated annealing are popular for exploring design space—especially when the solution space is complex and multidimensional. AI can enrich these methods, for example, by controlling mutations or selection based on feedback data. Such hybrids often appear in the literature on generative architecture (see reviews of generative AI for AEC). For example, the review ‘Generative AI in built environment design analyses mixed strategies of automation and optimization’ [43].

- Reinforcement Learning (RL)

RL is used when optimisation must account for a sequence of decisions or for adaptation to variable conditions in the troposphere. In the context of biomimetics, it can be used to ‘supervise the growth’ of a structure—the RL agent makes decisions about local changes in geometry in response to environmental signals. Although specific examples of RL in biomimetic architecture are still rare, this trend is gaining visibility in adaptive design and multi-agent optimisation (see reviews of AI in architecture) [41].

- Generative Design/generative models (GAN, diffusion, LLM as creator)

In recent years, the primary focus has been on generative models: GANs, VAEs, diffusion models, and large language models (LLMs), which are treated as creative interfaces or form description generators. In their paper ‘Generative AI Models for Different Steps in Architectural Design’ [6], review the applications of GANs, diffusion models, and generative 3D models in conceptual, façade, structural, and other phases. In the context of architecture, the paper ‘Generative AI-powered architectural exterior conceptual design’ shows how diffusion models (e.g., Stable Diffusion) can generate geometric proposals based on sketches and prompts [39]. The review ‘Generative AI in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction’ (Onatayo et al. 2024) analyses the presence of LLM and generative models in AEC practices and education [44].

Modern artificial intelligence systems in architecture are increasingly moving beyond the function of a simple form generator and becoming an active participant in the design process, capable of self-learning, reasoning and optimisation based on biological, material and environmental data. Their role is shifting towards design learning mechanisms—tools that can analyse the links between geometry, material, and manufacturing process, creating a process model similar to adaptive natural systems. One of the most critical areas of this approach is surrogate modelling. This method allows costly finite element method (FEM) calculations to be replaced with a predictive machine learning model that approximates the distributions of stresses, displacements, or deformation energy in the structure. A classic example is the work by Chi et al. (2021), ‘Universal machine learning for topology optimisation’, in which the authors integrated the learning process with the optimisation loop, without the need to create a separate training set [45]. The developed model reduced the calculation time by up to ten times compared to traditional topology optimisation [45]. In turn, Shin and co-authors (2023) showed that deep learning can not only accelerate but also improve the stability of the iterative process by introducing physical constraints into the neural network architecture (‘Physics-informed deep learning for topology optimisation’, Journal of Computational Design and Engineering) [46].

In recent years, feature learning has also been gaining importance, in which AI analyses biological microstructures and translates them into geometric and mechanical data useful in architectural design. In biomaterials research, this approach allows macroscale properties to be predicted based on fibre morphology, porosity or micro-layer distribution. An example is the work of Saimi et al. (2023), ‘Deep learning-based structure–property prediction of hierarchical composites’ [47], in which convolutional networks were trained to recognise microstructural patterns and link them to the prediction of Young’s modulus and material strength. Similar approaches have begun to be used in architectural design—models trained on biological data (e.g., nacre morphology or tissue structures) are used to generate forms optimised for stiffness and mass [6].

The third area of research is AI-based feedback-driven fabrication, i.e., the use of artificial intelligence to control the fabrication process in real time. In this type of solution, data from sensors (temperature, stress, robot arm movement speed) is analyzed by neural networks that learn to optimize the manufacturing strategy and minimize production errors. Such approaches are described, among others, in [48], where learning algorithms controlled the winding of fibres in ICD/ITKE composite structures. A similar direction is presented in the review by Zhang et al. (2024) [49], which systematises ways of integrating machine learning with adaptive robotics, 3D printing and process monitoring systems. Experimental studies [50] showed that coupling neural networks with sensors can reduce dimensional deviations by more than 40% and improve material consumption.

The examples collected show that the role of AI in architecture today goes far beyond formal creativity. These systems are increasingly involved in the decision-making process, learning from physical and environmental data. Their ability to predict and adapt is becoming crucial for the development of biomimetic architecture. Thanks to the integration of surrogate models, morphometric feature learning, and real-time control, a new, synergistic design paradigm is emerging—AI-driven biomimetic optimisation, in which the machine not only creates form but also learns design principles that previously belonged exclusively to the domain of nature.

1.3. Directions for Development and Challenges

In design practice, the boundaries between these approaches are becoming increasingly blurred. For example, in recent years, ICD/ITKE projects have combined fibre structure optimisation (surrogate modelling) with biological morphology analysis (feature learning) and adaptive robotic control (feedback control). This convergence of methods leads to a new paradigm—learning architecture, in which design, material, and process form a common, intelligent ecosystem.

The three approaches represent different levels of AI integration with architecture: from digital simulations (surrogate modelling) through biological data analysis and generation (feature learning) to physical materialisation and real-time feedback (feedback-driven fabrication) (Table 3). All are based on the same logic—the system’s ability to learn the relationships between form, material, and function.

Table 3.

Main approaches to the use of artificial intelligence in biomimetic optimisation of design and fabrication.

2. Points of Connection: How AI Is Expanding Biomimetics

The development of artificial intelligence in biomimetic architecture is not merely about adding an algorithmic component to existing design methods. AI increasingly acts as a ‘translator’ of nature—a tool that allows us to understand, translate, and reconstruct biological processes in the language of data, simulations, and models. In this sense, five main points of contact can be identified, which together form a new paradigm of AI-empowered biomimetic design.

2.1. AI as a Biology Translator

Computer vision, deep learning, and image segmentation techniques allow microscopic images, tomographic data, and biological scans to be analysed in ways previously unavailable to designers. In materials research, AI is used to identify hierarchical structures that determine mechanical properties, as in the work of Saimi et al. (2023) [47], where convolutional neural networks predicted the stiffness of composites based on microscopic images. A similar approach was used in the analysis of wood, Luo et al. 2024 [51], where AI enabled the classification of fibre orientation and porosity.

In the context of architecture, the same machine learning and image analysis techniques can be used to extract geometric patterns from biological data and translate them into design parameters. A good reference point is the work that quantitatively describes the microarchitecture of insect wings and translates it into rules for shaping composites: Liu et al. (2017) showed how the morphology and anisotropy of wings affect the mechanical properties of artificial wings, providing measurable descriptors (veining patterns, node density, field proportions) that can be directly parameterised in CAD/BIM environments as panel meshes or perforation patterns [52].

Xu et al. (2021) demonstrated that the architecture of a dragonfly wing—combining stiffness with fracture resistance through a hierarchical network of veins and bridges—can be translated into ‘composite rules’ resulting in composites that are both stiff and resistant, which provides a direct indication of how to model load-bearing patterns in lightweight shells and adaptive façades [53]. From a broader perspective, the review by Goyes-Balladares et al. confirms that the systematic identification of biological structures and systems is a key step in transferring the principles of nature to AEC design, with AI acting as an ‘interpreter’ between biological data and design metrics [54].

2.2. AI as a Structural Optimization Tool

Supervised learning and surrogate modeling methods allow expensive FEM calculations to be replaced with predictive ML models. In the work of Chi et al. (2021), Universal machine learning for topology optimization [45], the authors proposed a model that learns local relationships between stress distribution and geometry, which reduced optimization time by up to tenfold. In turn, physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) allow the introduction of constraints resulting from the laws of physics into the network, as shown in the work of Kim et al. (2023), Physics-informed deep learning for topology optimization [46].

In this context, AI acts like an engineer analyzing thousands of variants and selecting structures with the best mass-to-stiffness ratio. An example of practical implementation is the research conducted by the ICD/ITKE team (Stuttgart), where learning models predicted deformations in composite structures in real time, enabling dynamic shape correction during robotic fabrication [48]. A comprehensive overview of these methods is provided in ‘A Review of Artificial Intelligence in Enhancing Architectural Design’ [7], in which the authors systematize the applications of AI in structural design, pointing out that the integration of learning methods with structural analysis is becoming standard in computational design.

2.3. AI as a Biomimetic Geometry Generating Tool

Models such as GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks), VAEs (Variational Autoencoders), and diffusion models enable the generation of nature-inspired forms without the need for direct parametric modeling. A current overview showing how these models are used in subsequent stages of the design process, including for varying the geometry of facades and structures, was presented by Li et al. (2024) [6]. Complementarily, a study by Horváth & Pouliou (2024) discusses the practical applications of text-to-image and image-to-image tools in architectural design, with an emphasis on the role of generative AI in shaping morphology and the language of forms [55]. In turn, Zhang et al. 2023demonstrate an integrated “domain prompts + sketch → image” workflow for early facade design, illustrating how diffusion models and fine-tuning support the generation of geometric variants consistent with design intent [42].

A new direction is the integration of large language models (LLMs) with generative design tools. For example, LLMs can translate a verbal description of a biological pattern into a Grasshopper script or parametric code, becoming an intermediary between natural language and geometric morphology. Applications of this type are discussed in the review [56]. The text points out that generative AI, combined with biological data, enables the creation of morphologies with a degree of complexity that cannot be achieved with classical methods. Practical examples include projects by creators such as Neri Oxman and Achim Menges, where generative algorithms mimic the process of tissue growth and differentiation in architectural structures (e.g., Silk Pavilion II, MIT Media Lab, 2019) [57]. It is also worth mentioning the review ‘A Systematic Review’ by Adewale et al. (2024) [57], which indicates that generative applications in architecture increasingly include morphology and structure, not just conceptual visualizations.

2.4. AI as a Resource and Material Manager

Machine learning systems can analyze the carbon footprint, energy consumption, and emissions throughout a building’s life cycle and then identify solutions with the least environmental impact. In the context of biomimetics, systems that optimize local prefabrication strategies are particularly interesting—e.g., generating module layouts depending on available materials and transport conditions. This approach is being developed in projects at ETH Zurich (Spatial Timber Assemblies, Gramazio Kohler Research, 2020–2022), where AI analyzes the availability of wooden elements with different cross-sections and adapts the geometry of structural nodes to material and environmental parameters. Machine learning systems can analyze the carbon footprint, energy consumption, and emissions throughout the entire life cycle of a building.

In turn, Diaz-Parra et al. (2025) [16] show how integrated biomimetic and AI approaches can support urban planning, material logistics, and prefabrication strategy.

AI-driven resource management is also emerging in highly standardized building typologies, where geometry, prefabrication, and carbon emissions are jointly optimized. Recent studies on chain hotel buildings use multidimensional neural networks and algorithmic models to couple prefabricated aesthetics, room 3D ratios, and low-carbon 3D-printed construction, demonstrating that indoor volumetric proportions can be treated as active variables in carbon-efficiency optimization rather than fixed design by-products [58,59]. Complementary work on robot in situ 3D printing for prefabricated decoration shows how multidimensional algorithm models can link indoor room 3D ratios with emission reduction strategies at the scale of repetitive hotel rooms [60]. Together, these examples indicate that AI can act as a carbon-aware configurator of space, materials, and fabrication methods, offering a transferable logic for future biomimetic, low-carbon prefabricated systems.

2.5. AI in Bio-Inspired Manufacturing Processes

AI not only analyzes and generates but also increasingly controls the manufacturing process—from 3D printing with biocomposites to adaptive robotics. In research on printing with biological materials (e.g., biopolymers, lignin, cellulose), algorithms learn to correlate printing parameters with the morphology of biological growth. An example is the BioMat Pavilion project (2023, Stuttgart University), which uses neural networks to control the extrusion process of biocomposites and compensate for material shrinkage during drying. Similarly, in the FIBERBOTS project erected at MIT in 2018 [33], Tibbits’ team developed a system of autonomous robots that participated in forming a structure based on local data and self-organization principles.

More and more studies are also linking AI to so-called growth algorithms—models that learn from biological processes, such as coral growth or root systems. The review [61] indicates that such approaches lead to the emergence of a new class of “self-fabricating” architecture, in which the design and manufacturing processes are integrated into a single data cycle. It is also worth mentioning the review ‘A Systematic Review’ by Adewale et al. (2024) [57], which indicates that generative applications in architecture increasingly include morphology and structure, not just conceptual visualizations. Similar conclusions are presented in Faragalla et al. (2022) [1], where the authors analyze façade systems that respond to environmental stimuli, controlled by supervised learning models.

3. Materials and Methods

Bionic architecture assumes that the form, structure, or function of a building is inspired by nature, just as a leaf, shell, or bone has an optimal structure for its purpose. Algorithms can therefore analyze patterns found in natural systems (such as stress distribution in bones, shapes of shells, branches, or cells), model architectural forms based on these patterns, and optimize them with respect to function (for example, strength, airflow, lighting, or material efficiency).

The purpose of the study is to define a theoretical framework and workflow that could guide future applications of artificial intelligence in bionic architectural design. The methodology combines four complementary areas of research:

- Analysis of existing approaches in generative modeling and form finding;

- Review of biological structures and their computational abstraction;

- Examination of AI and machine learning techniques relevant to geometry and performance optimization; and

- Integration of these domains into a coherent workflow for design exploration.

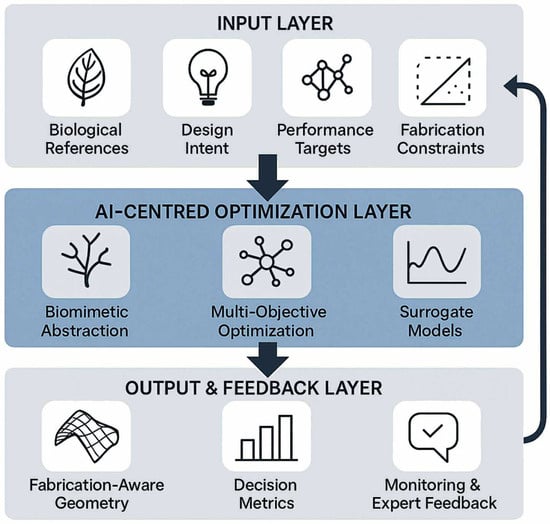

A workflow (Figure 1) was developed to illustrate how AI could interact with parametric design environments. The process begins with the collection of biological references, forms, and structures that exhibit functional adaptation. These are conceptually represented in a database that includes geometric, mechanical, and functional descriptors. In the next stage, AI models are assumed to learn from these biological features, identifying structural and functional principles that can be translated into computational models. Based on this learning process, AI supports the generation of architectural forms, which are then tested conceptually for efficiency, adaptability, and sustainability.

Figure 1.

Proposed Bionic Architecture Design Cycle. Authors Compilation generated with Napkin AI.

The methodology follows a design science approach, where the goal is to construct and evaluate a conceptual model rather than produce numerical results. The proposed framework was reviewed against current practices in computational design, parametric modeling, and bioinspired engineering to ensure logical coherence and practical feasibility.

4. Results

4.1. Biological Pattern Database

The foundation of the proposed system is a database of biological structural patterns, serving as a reference for learning the relationships between form and function. The database would include several categories of information:

- 3D scans of natural structures—such as bones, leaves, shells, or corals, capturing their geometric and morphological characteristics;

- Physical and biomechanical data—including density, elastic modulus, porosity, and other measurable parameters that describe material behavior;

- Functional descriptions—for example, “stress dispersion,” “optimal ventilation,” or “light diffusion,” representing the natural functions that specific structures perform.

Each record would contain both geometric data and a set of quantitative metrics describing how form relates to function. By linking these features, the database would allow machine learning algorithms to study and model the underlying dependencies between biological morphology and performance. This dataset forms the knowledge base for AI-driven generative processes, enabling the translation of natural design principles into computational frameworks. It not only documents biological efficiency but also serves as a source of learning for algorithmic creativity, where architectural forms evolve from the same functional logic that guides natural structures.

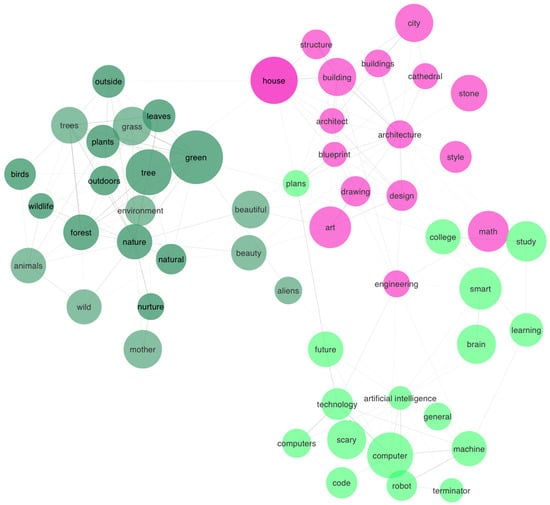

Figure 2 shows a semantic network of word associations, revealing how people intuitively connect concepts such as architecture, nature, and artificial intelligence. In the context of bionic architectural design using AI, this network highlights the cognitive bridges between natural systems (trees, greenery, environment) and human-made structures (buildings, design, architecture). These associations illustrate how artificial intelligence can help translate biological principles into architectural forms by learning from patterns in natural systems and integrating them into computational design processes. The map represents linguistic relationships and also the conceptual foundation for merging organic thinking with intelligent architectural modeling.

Figure 2.

Forward association network visualization ARCHITECTURE—NATURE—ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE from the Small World of Words project (De Deyne & Storms, University of Leuven and University of Melbourne), colours in the diagram: dark green refer to NATURE based topics, light green refer to ARTIFICIAL based topis, magenta refer to ARCHITEKCTURE based topis. [Source: https://smallworldofwords.org (accessed on 11 November), Figure provided by Simon De Dedeyne and Gert Storm, and used with their permission].

The proposed Biological Pattern Database (BPD) is designed as a modular and representation-agnostic system for storing, describing, and analyzing biological structural patterns. It serves as the foundation for learning the relationships between form and function in natural systems and enables their translation into architectural applications.

Given that current AI models for 3D geometry analysis are still developing, the BPD is designed to handle multiple levels of data representation, from full 3D models to simplified or derived 2D and numerical datasets. This flexibility ensures that the same specimen can be used with both present-day machine learning techniques (e.g., multi-view 2D image analysis) and future 3D-specific architectures (e.g., graph neural networks or point-cloud networks).

Each biological specimen is stored under a unique Specimen_ID and may contain several interconnected data layers. The structure is summarized in Table 4 below.

Table 4.

Structure of the Biological Pattern Database (BPD).

This layered approach allows for consistent and scalable data management. For instance, a single coral specimen can include a 3D mesh (RAW_3D), a set of twelve rendered 2D views (DERIVATIVES), curvature and porosity metrics (FEATURES), a “load branching” tag with a stress dispersion score (LABELS), and metadata describing its biological category and acquisition process (METADATA).

By keeping these representations logically connected yet independent, the database ensures long-term adaptability: today it can support AI trained on 2D projections, while in the future it can be seamlessly expanded to fully 3D deep learning workflows.

The BPD is designed to comply with the FAIR data principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) and can be populated with open-access resources such as MorphoSource, Smithsonian 3D, or Zenodo. This ensures transparency, reusability, and interoperability with computational design and simulation tools such as Rhino, Grasshopper, Karamba3D, or TensorFlow.

4.2. Machine Learning

The collected biological data can be analyzed and processed using machine learning algorithms to identify relationships between form and function in natural structures. In particular, deep learning models (such as convolutional, graph-based, or autoencoder networks) can recognize hidden geometric and functional patterns in spatial data and translate them into computationally usable representations.

The proposed learning process consists of four interconnected stages (Table 5). Each stage feeds into the next, forming a closed loop of continuous learning and design improvement.

Table 5.

Stages of the AI-driven Bionic Design Process.

This iterative cycle creates a closed learning loop, where every generated design contributes new information to the model. Through repeated evaluation and retraining, the system gradually develops an understanding of efficient geometric principles similar to those found in natural evolution. To improve interpretability, intermediate models can visualize learned feature maps or activation patterns, showing which parts of a structure influence performance predictions. These visualizations not only help verify model reliability but also support the designer’s creative process, providing insights into the morphological logic of biological efficiency. In this framework, artificial intelligence acts as a mediator between the complexity of nature and the rationality of engineering. It not only reproduces natural shapes but also learns the underlying principles that govern their adaptability and performance. As a result, AI becomes a tool for functional translation, transforming the logic of natural systems into architectural forms that are simultaneously expressive, efficient, and environmentally responsive.

4.3. System Integration and Workflow Implementation

The proposed system could be implemented within a design environment that combines parametric modeling (for example, Rhino + Grasshopper) with developed artificial intelligence modules. The biological dataset would serve as input for neural networks, which would generate parameter sets controlling the architectural model. The interface could enable:

- Selection of a design objective (e.g., maximizing stiffness while minimizing material use),

- Choice of biological reference patterns,

- Automatic generation and evaluation of multiple design variants.

This setup creates a complete learning-based design cycle: from the observation of nature, through computational modeling and simulation, to automatic refinement of the design. The system can be integrated with BIM tools, allowing results from AI-driven analyses to be incorporated into subsequent stages of architectural and structural design.

From a methodological point of view, the integration of AI and biomimetics requires a change in the way architectural research is conducted. The sequential model (analysis–design–implementation) is being replaced by an iterative and concurrent model, in which biological data, learning models, and the fabrication process coexist in real time. This model of work requires interdisciplinarity—combining knowledge from the fields of architecture, computer science, materials science, robotics, and biology. For the scientific community, this means the need to develop validation methods that combine simulation with experimentation. For design practice, it means creating design environments that integrate AI with CAD/BIM tools.

In terms of education, there is a clear need to redefine the training of architects and engineers. Future teaching programmes should combine the themes of biological morphogenesis, parametric design, and the basics of machine learning. AIAD (Artificial Intelligence in Architectural Design) is becoming a natural extension of CAAD. On this stage, students learn not only to model but also to train algorithms, interpret data, and understand their impact on the shape of space. In this context, design laboratories, where simulations, environmental data and the fabrication process are integrated into a single workflow, can become a key teaching tool (Table 6).

Table 6.

Potential future applications of AI-driven biomimetic optimisation methods in architecture and engineering.

From a sustainability perspective, the combination of AI and biomimetics points the way towards designing systems that not only minimise resource consumption but also adapt to climate and environmental change. This type of ‘living architecture’ may in the future combine digital technologies with biological processes to create self-regulating, responsive, and renewable structures.

Biomimicry enhanced by artificial intelligence is becoming less of a formal inspiration and more of a cognitive and educational method. Its significance lies in its ability to transform biological observation into a design system based on data, learning, and cooperation between humans, machines, and nature. It is in this triad—biology–algorithm–material—that the future of digital architecture is taking shape.

5. Conclusions

The paper has proposed an AI-driven biomimetic optimisation framework that links biological precedents, material systems and geometry processing with performance-based criteria and fabrication constraints. By bringing together biomimetic pattern extraction, multi-objective optimisation and digital prefabrication workflows, the study has outlined how AI can structure the design search space rather than only accelerate conventional simulation. In this sense, AI is repositioned from a purely analytical tool to an active mediator between biological reference logics, structural performance and constructional feasibility.

Despite these contributions, several research gaps remain. Current AI models used in architectural and structural optimisation rely on fragmented datasets that rarely couple biological morphology, mechanical performance, fabrication tolerances, and long-term environmental data consistently. The lack of shared benchmarks makes it difficult to compare models or to evaluate to what extent “biomimetic” solutions genuinely approximate the behaviour of biological systems. Moreover, most workflows still treat uncertainty, model bias, and explainability as secondary issues, even though they are critical when AI-generated geometries are intended for real-world construction.

These gaps suggest clear future research directions. One priority is the creation of open, cross-scale datasets that integrate biological typologies, structural response, life-cycle metrics, and fabrication metadata, enabling more rigorous training and validation of AI models. Another is the coupling of generative algorithms with differentiable solvers and surrogate models, enabling AI to directly navigate multi-objective trade-offs among structural efficiency, material use, carbon footprint, and constructability. There is also a need for human–AI co-design protocols, in which designers can interrogate, steer, and selectively adopt AI-generated biomimetic strategies, rather than post-rationalise them.

The proposed AI-driven biomimetic optimisation framework has practical implications for design and construction. It can support early-stage decision making by rapidly exploring families of geometry and material configurations that satisfy structural and environmental targets while remaining compatible with specific prefabrication and assembly systems. For industry stakeholders, such a framework may inform the development of design guidelines and digital pipelines that connect parametric modelling environments with robotic or modular fabrication, reducing both design iteration time and material waste. At the urban and territorial scale, the same principles can be extended to coordinate multiple biomimetic systems, turning AI into an integrative layer between architectural expression, structural logic, and low-carbon construction practice.

5.1. Study Limitations

Although this study provides a broad overview of recent research, the scope of the analysis was limited to English-language sources indexed in Q1–Q2 databases, which may have omitted some important experimental or design-related publications. The article also does not include code-level implementation analyses or full case studies of AI implementations in architectural practice. Due to the rapid pace of development of generative models (especially LLM and diffusion models), some of the technologies mentioned may become obsolete within a few years. The authors have deliberately limited the scope to AI applications in the field of biomimetic design and fabrication, omitting the broader applications of AI in building management and operation.

5.2. Future Scope of the Study

Further research plans to expand the analysis into two parallel streams:

- (1)

- Experimental implementations—integrating ML models with robotic fabrication processes and biocomposite printing to verify the effectiveness of AI in adaptive structural optimisation;

- (2)

- Didactic research—testing AIAD models in an educational environment to determine how artificial intelligence influences the design thinking of architecture students.

Future work should also aim to develop standardised methods for evaluating the quality of AI-generated biomimetic designs, covering structural, energy, and environmental aspects. Another critical challenge is the issue of data ethics: the responsible use of models trained on biological and creative materials, which requires transparency, traceability and intellectual property protection.

In the long term, AI-driven biomimetic optimisation has the potential to define a new branch of architectural research: ‘digital biomimetics’—a field combining computational biology, generative design, and physical fabrication into a coherent, self-learning system.

The proposed AI-driven Biomimetic Optimisation Framework can be synthesised in three interconnected layers (Figure 3). The input layer aggregates biological references, design intents, performance targets and fabrication constraints, translating them into a structured set of parameters and objectives. The AI-centred optimisation layer integrates biomimetic abstraction modules, multi-objective search algorithms and fast surrogate models that iteratively generate and evaluate candidate geometries and material systems. The output and feedback layer delivers implementable design solutions, fabrication-aware geometries and decision-support metrics while feeding back monitoring data and expert evaluation into the model. This structure highlights that AI does not operate in isolation but within a continuous loop that couples biological inspiration, structural logic and construction processes.

Figure 3.

AI-driven Biomimetic Optimisation Framework for architectural and structural design. The model links biological references, design objectives and fabrication constraints (input layer) with AI-based biomimetic abstraction and multi-objective optimisation (AI-centred layer) and with fabrication-aware design outputs and decision-support metrics (output and feedback layer).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and M.K.; methodology, A.S. and M.K.; software, M.K.; validation, A.S. and M.K.; formal analysis, A.S. and M.K.; investigation, A.S.; data curation, A.S. and M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, A.S. and M.K.; visualization, M.K.; supervision, A.S.; project administration, A.S.; funding acquisition, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing does not apply to this article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used Grammarly for editing style and grammar. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Faragalla, A.M.A.; Asadi, S. Biomimetic Design for Adaptive Building Façades: A Paradigm Shift towards Environmentally Conscious Architecture. Energies 2022, 15, 5390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, Y.; Li, S.; Duan, H. Artificial Intelligence-Aided Design (AIAD) for Structures and Engineering: A State-of-the-Art Review and Future Perspectives. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2025, 32, 4197–4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommese, F.; Ausiello, G. From Nature to Architecture for Low Tech Solutions: Biomimetic Principles for Climate-Adaptive Building Envelope. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Technological Imagination in the Green and Digital Transition, Rome, Italy, 30 June–2 July 2022; pp. 429–438. [Google Scholar]

- Cocho-Bermejo, A. Adaptive Architectural Facades: Review 1985–2024. A Comparative Analysis of Media-TIC, the Arab Institute, and Al Bahar Towers Dynamic Facades Approaches. Nexus Netw. J. 2025, 27, 925–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etim, B.; Al-Ghosoun, A.; Renno, J.; Seaid, M.; Mohamed, M.S. Machine Learning-Based Modeling for Structural Engineering: A Comprehensive Survey and Applications Overview. Buildings 2024, 14, 3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, T.; Du, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, H. Generative AI Models for Different Steps in Architectural Design: A Literature Review. Front. Archit. Res. 2025, 14, 759–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Yu, P.; Yang, L. A Review of Artificial Intelligence in Enhancing Architectural Design Efficiency. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocho-Bermejo, A. Artificial Intelligence and Architectural Design Before Generative AI: Artificial Intelligence Algorithmics Approaches 2000–2022 in Review. Eng. Rep. 2025, 7, e70114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, H.-T. Machine Learning for Structural Engineering: A State-of-the-Art Review. Structures 2022, 38, 448–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koffler, J. The Future of Biomimetic 3D Printing. J. 3D Print. Med. 2019, 3, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Joralmon, D.; Li, X. 3D Printing of Biomimetic Functional Nanocomposites via Vat Photopolymerization. In Advances in 3D Printing; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Xuan, S.; Sun, S.; Xu, Z.; Li, J.; Gong, X. 3D Printing Magnetic Actuators for Biomimetic Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 30127–30136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-X.; Zha, X.-J.; Xia, Y.-K.; Ling, T.-X.; Xiong, J.; Huang, J.-G. 3D Foaming Printing Biomimetic Hierarchically Macro–Micronanoporous Hydrogels for Enhancing Cell Growth and Proliferation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 10813–10821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamei, E.; Vrcelj, Z. Biomimicry and the Built Environment, Learning from Nature’s Solutions. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbrugghe, N.; Rubinacci, E.; Khan, A.Z. Biomimicry in Architecture: A Review of Definitions, Case Studies, and Design Methods. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Parra, O.; Trejo-Macotela, F.R.; Ruiz-Vanoye, J.A.; Aguilar-Ortiz, J.; Ruiz-Jaimes, M.A.; Toledo-Navarro, Y.; Penna, A.F.; Barrera-Cámara, R.A.; Salgado-Ramirez, J.C. Integrated Biomimetics: Natural Innovations for Urban Design, Smart Technologies, and Human Health. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommese, F.; Badarnah, L.; Ausiello, G. A Critical Review of Biomimetic Building Envelopes: Towards a Bio-Adaptive Model from Nature to Architecture. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 169, 112850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijari, M.; Aflaki, A.; Esfandiari, M. Plants Inspired Biomimetics Architecture in Modern Buildings: A Review of Form, Function and Energy. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Stefańska, A. Bio-Logic, a Review on the Biomimetic Application in Architectural and Structural Design. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 101822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAli, M.; Mattar, Y.; Alzaim, M.; Beheiry, S. Applications of Biomimicry in Architecture, Construction and Civil Engineering. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musenich, L.; Stagni, A.; Libonati, F. Hierarchical Bioinspired Architected Materials and Structures. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 2023, 58, 101945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohner, M. Biomimetic Materials in the Construction Industry Development, Awareness and Potential. Ph.D. Thesis, TU Wien, Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, O. Biomimetic Materials in Our World: A Review. IOSR J. Appl. Chem. 2013, 5, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, G.; Nachtigall, W. Biomimetics for Architecture & Design: Nature-Analogies-Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dambrosio, N.; Zechmeister, C.; Pérez, M.G.; Dörstelmann, M.; Stark, T.; Rinderspacher, K.; Knippers, J.; Menges, A. Livmats Pavilion: Design and Development of a Novel Building System Based on Natural Fibres Coreless-Wound Structural Components for Applications in Architecture. J. Int. Assoc. Shell Spat. Struct. 2024, 65, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianciardi, A.; Becattini, N.; Cascini, G. How Would Nature Design and Implement Nature-Based Solutions? Nat.-Based Solut. 2023, 3, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beesley, P. Hylozoic Ground: Canadian Pavilion, Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy-2010/Philip Beesley (Living Architecture Systems Group); Riverside Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 9781926724997. [Google Scholar]

- Doerstelmann, M.; Knippers, J.; Menges, A.; Parascho, S.; Prado, M.; Schwinn, T. ICD/ITKE Research Pavilion 2013-14: Modular Coreless Filament Winding Based on Beetle Elytra. Archit. Des. 2015, 85, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerstelmann, M.; Knippers, J.; Koslowski, V.; Menges, A.; Prado, M.; Schieber, G.; Vasey, L. ICD/ITKE Research Pavilion 2014–15: Fibre Placement on a Pneumatic Body Based on a Water Spider Web. Archit. Des. 2015, 85, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solly, J.; Früh, N.; Saffarian, S.; Aldinger, L.; Margariti, G.; Knippers, J. Structural Design of a Lattice Composite Cantilever. Structures 2019, 18, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechert, S.; Sonntag, D.; Aldinger, L.; Knippers, J. Integrative Structural Design and Engineering Methods for Segmented Timber Shells-BUGA Wood Pavilion. Structures 2021, 34, 4814–4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil Pérez, M.; Rongen, B.; Koslowski, V.; Knippers, J. Structural Design, Optimization and Detailing of the BUGA Fibre Pavilion. Int. J. Space Struct. 2020, 35, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menges, A.; Kannenberg, F.; Zechmeister, C. Computational Co-Design of Fibrous Architecture. Archit. Intell. 2022, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil Pérez, M.; Früh, N.; La Magna, R.; Knippers, J. Integrative Structural Design of a Timber-Fibre Hybrid Building System Fabricated through Coreless Filament Winding: Maison Fibre. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 49, 104114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laccone, F.; Malomo, L.; Pérez, J.; Pietroni, N.; Ponchio, F.; Bickel, B.; Cignoni, P. A Bending-Active Twisted-Arch Plywood Structure: Computational Design and Fabrication of the FlexMaps Pavilion. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, M.; Cai, L.; Falcone, S.; Bader, C.; Inglessis, N.; Darweesh, B.; Oxman, N. FIBERBOTS: An Autonomous Swarm-Based Robotic System for Digital Fabrication of Fiber-Based Composites. Constr. Robot. 2018, 2, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senhora, F.V.; Chi, H.; Zhang, Y.; Mirabella, L.; Tang, T.L.E.; Paulino, G.H. Machine Learning for Topology Optimization: Physics-Based Learning through an Independent Training Strategy. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2022, 398, 115116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Shin, D.; Kang, N. Topology Optimization via Machine Learning and Deep Learning: A Review. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2023, 10, 1736–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Seo, J.; Cha, S.H.; Xiao, B.; Chi, H.-L. Generative AI-Powered Architectural Exterior Conceptual Design Based on the Design Intent. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2024, 11, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Roh, H.; Lee, G. Generative AI in Architectural Design: Application, Data, and Evaluation Methods. Autom. Constr. 2025, 174, 106174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albukhari, I.N. The Role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Architectural Design: A Systematic Review of Emerging Technologies and Applications. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Eng. Archit. 2025, 16, 1457–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Du, Z.; Liu, C.; Youn, S.-K.; Guo, X. Machine-Learning Assisted Topology Optimization for Architectural Design with Artistic Flavor. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2023, 413, 116041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, R. Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Built Environment Design and Planning—A State-of-the-Art Review. Prog. Eng. Sci. 2025, 2, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onatayo, D.; Onososen, A.; Oyediran, A.O.; Oyediran, H.; Arowoiya, V.; Onatayo, E. Generative AI Applications in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction: Trends, Implications for Practice, Education & Imperatives for Upskilling—A Review. Architecture 2024, 4, 877–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, T.L.E.; Mirabella, L.; Dalloro, L.; Song, L.; Paulino, G.H. Universal Machine Learning for Topology Optimization. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2021, 375, 112739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, C.H.; Suh, C.; Chae, M.; Yoon, H.; Youn, B.D. MPARN: Multi-Scale Path Attention Residual Network for Fault Diagnosis of Rotating Machines. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2023, 10, 860–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saimi, A.; Bensaid, I.; Civalek, Ö. A Study on the Crack Presence Effect on Dynamical Behaviour of Bi-Directional Compositionally Imperfect Material Graded Micro Beams. Compos. Struct. 2023, 316, 117032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Kim, H.; Lim, H.J.; Liu, P.; Sohn, H. Automated Visualization of Steel Structure Coating Thickness Using Line Laser Scanning Thermography. Autom. Constr. 2022, 139, 104267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Guo, J.; Fu, X.; Tiong, R.L.K.; Zhang, P. Digital Twin Enabled Real-Time Advanced Control of TBM Operation Using Deep Learning Methods. Autom. Constr. 2024, 158, 105240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasri, W.; Danglade, F.; Bettebghor, D.; Adjed, F.; Ababsa, F. Deep Learning for Additive Manufacturing-Driven Topology Optimization. Procedia CIRP 2022, 109, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Z.; Hu, Q.; Hoque, M.A.; Ahmed, A. Enhancing Deep Line Segment Detection and Performance Evaluation for Wood: A Deep Learning Approach with Experiment-Based, Domain-Specific Implementations. Forests 2024, 15, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yan, X.; Qi, M.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, D.; Zhang, X.; Lin, L. Artificial Insect Wings with Biomimetic Wing Morphology and Mechanical Properties. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2017, 12, 056007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, K.; Lei, C.; Fu, Q.; Fu, J. Dragonfly Wing-Inspired Architecture Makes a Stiff yet Tough Healable Material. Matter 2021, 4, 2474–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyes-Balladares, A.; Moya-Jiménez, R.; Molina-Dueñas, V.; Chaca-Espinoza, W.; Magal-Royo, T. What Inspires Biomimicry in Construction? Patterns, Trends, and Applications. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, A.-S.; Pouliou, P. AI for Conceptual Architecture: Reflections on Designing with Text-to-Text, Text-to-Image, and Image-to-Image Generators. Front. Archit. Res. 2024, 13, 593–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjari Nabi, R.; Rezaei, N.; Mohammad Zadeh, R.; Haghparast, F. A Study on the Form Contemporary Developments of Tabriz Leather and Shoe Bazaar (Marketplace) from the Late Qajar to Current Period. Front. Archit. Res. 2024, 13, 741–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewale, B.A.; Ene, V.O.; Ogunbayo, B.F.; Aigbavboa, C.O. A Systematic Review of the Applications of AI in a Sustainable Building’s Lifecycle. Buildings 2024, 14, 2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Lou, Y.; Lu, F. AI Enhancing Prefabricated Aesthetics and Low Carbon Coupled with 3D Printing in Chain Hotel Buildings from Multidimensional Neural Networks. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, G.; Liu, D.; Wu, Z. Multidimensional Algorithms-Based Carbon Efficiency Model of Building Geometric 3D Ratios for Prefabricated 3D Printing Design and Construction. npj Clean Energy 2025, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Sun, L.; Liu, D.; Xu, B.; Mo, Z. Potential of Indoor Room 3D Ratio in Reducing Carbon Emissions by Prefabricated Decoration in Chain Hotel Buildings via Multidimensional Algorithm Models for Robot In-Situ 3D Printing. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 101, 111757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, M.; Mekkattu, M.; Katzschmann, R.K. Sustainable Biofabrication: From Bioprinting to AI-Driven Predictive Methods. Trends Biotechnol. 2025, 43, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).