Hydrodynamic Aging Process Altered Benzo(a)pyrene Adsorption on Poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) and Poly(butylene succinate) Microplastics in Seawater

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Materials

2.2. The Preparation of Hydrodynamic-Seawater-Aged MPs

2.3. Adsorption and Desorption Assays

2.4. Desorption in the Simulated Gastric Fluid

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Adsorption and Desorption of BaP on Hydrodynamic-Seawater-Aged MPs

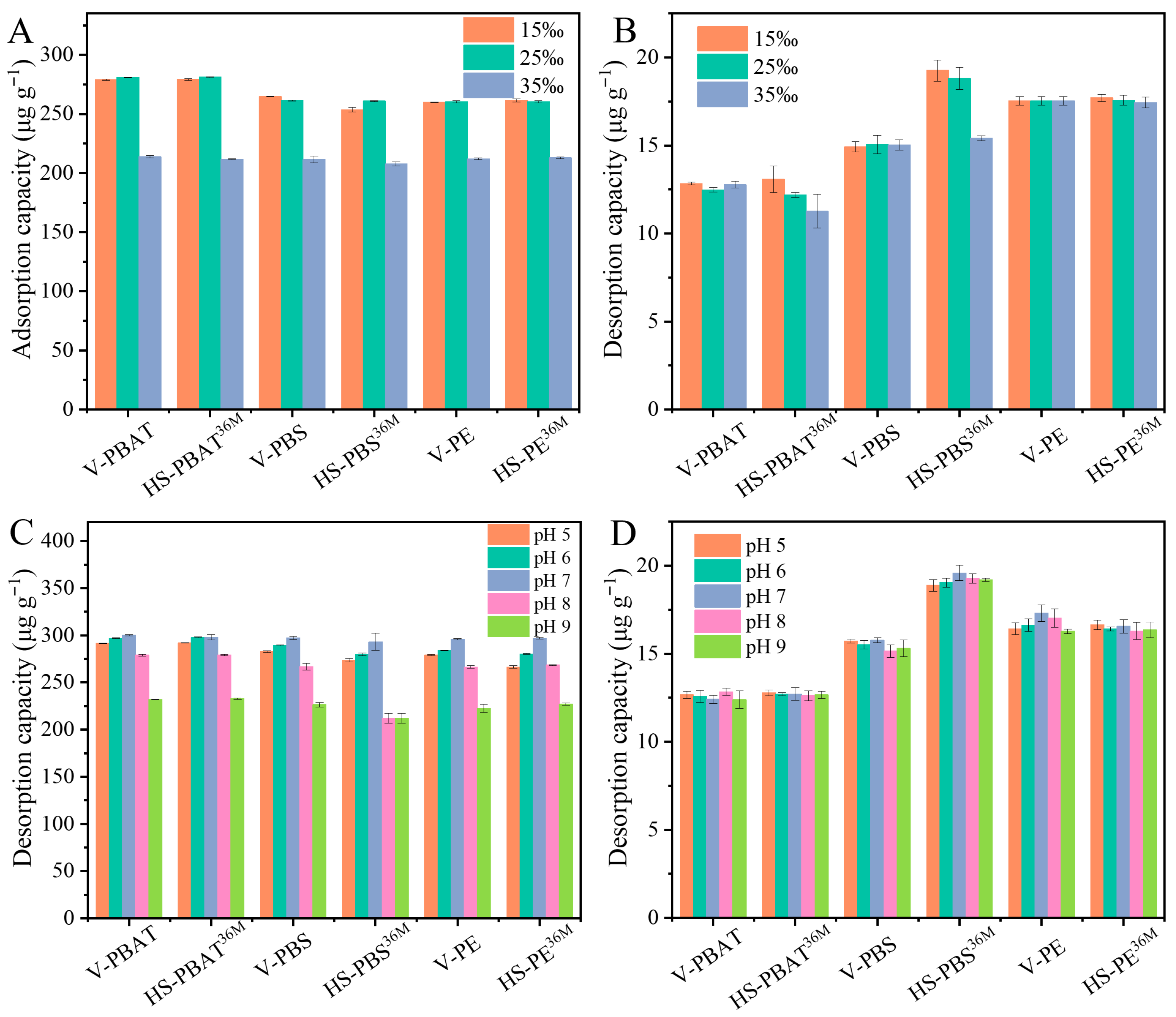

3.2. Influence of pH and Salinity on BaP Adsorption/Desorption by MPs

3.3. Desorption in the Simulated Gastric Fluid

3.4. Adsorption Isotherms of BaP on Different MPs

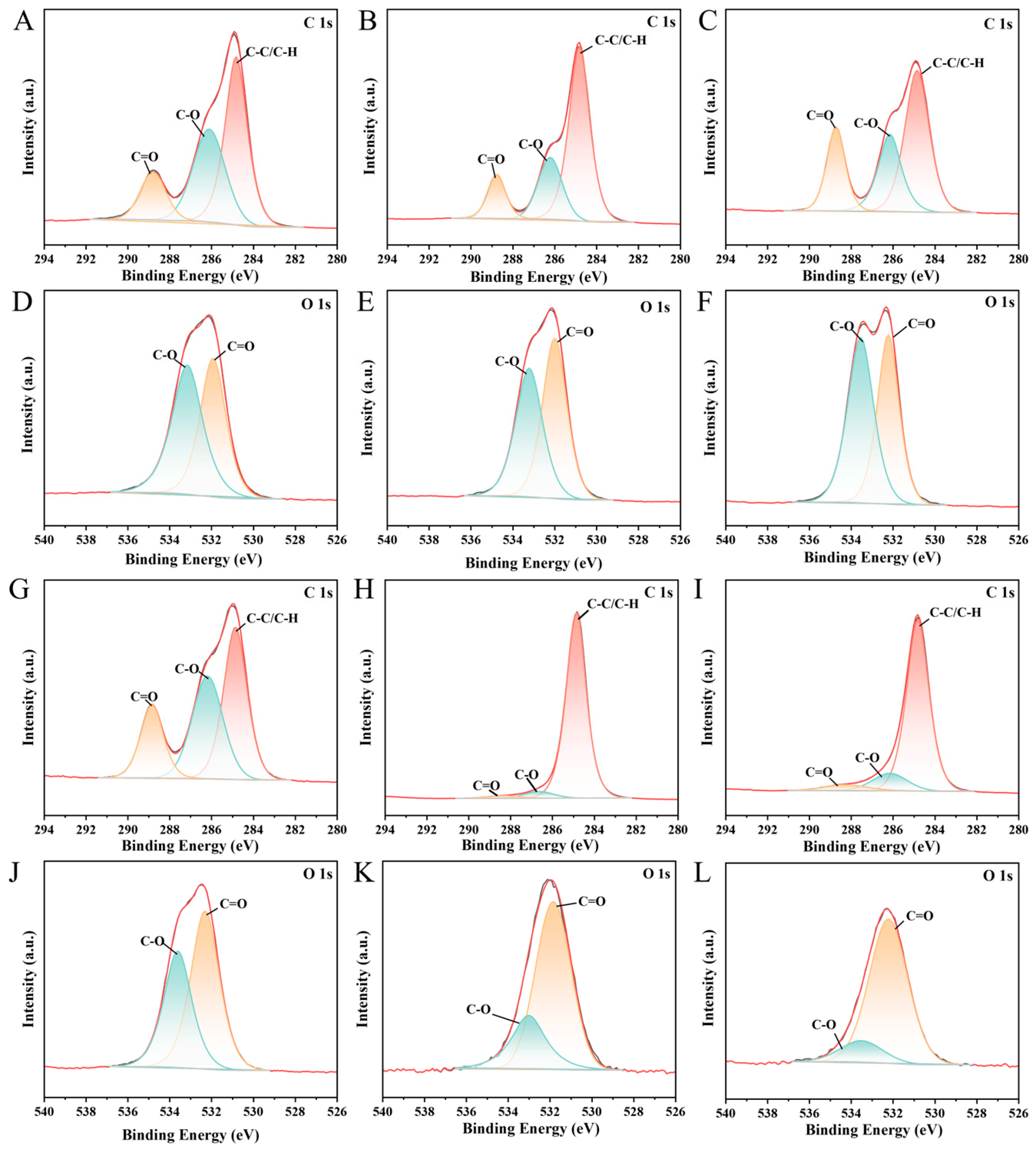

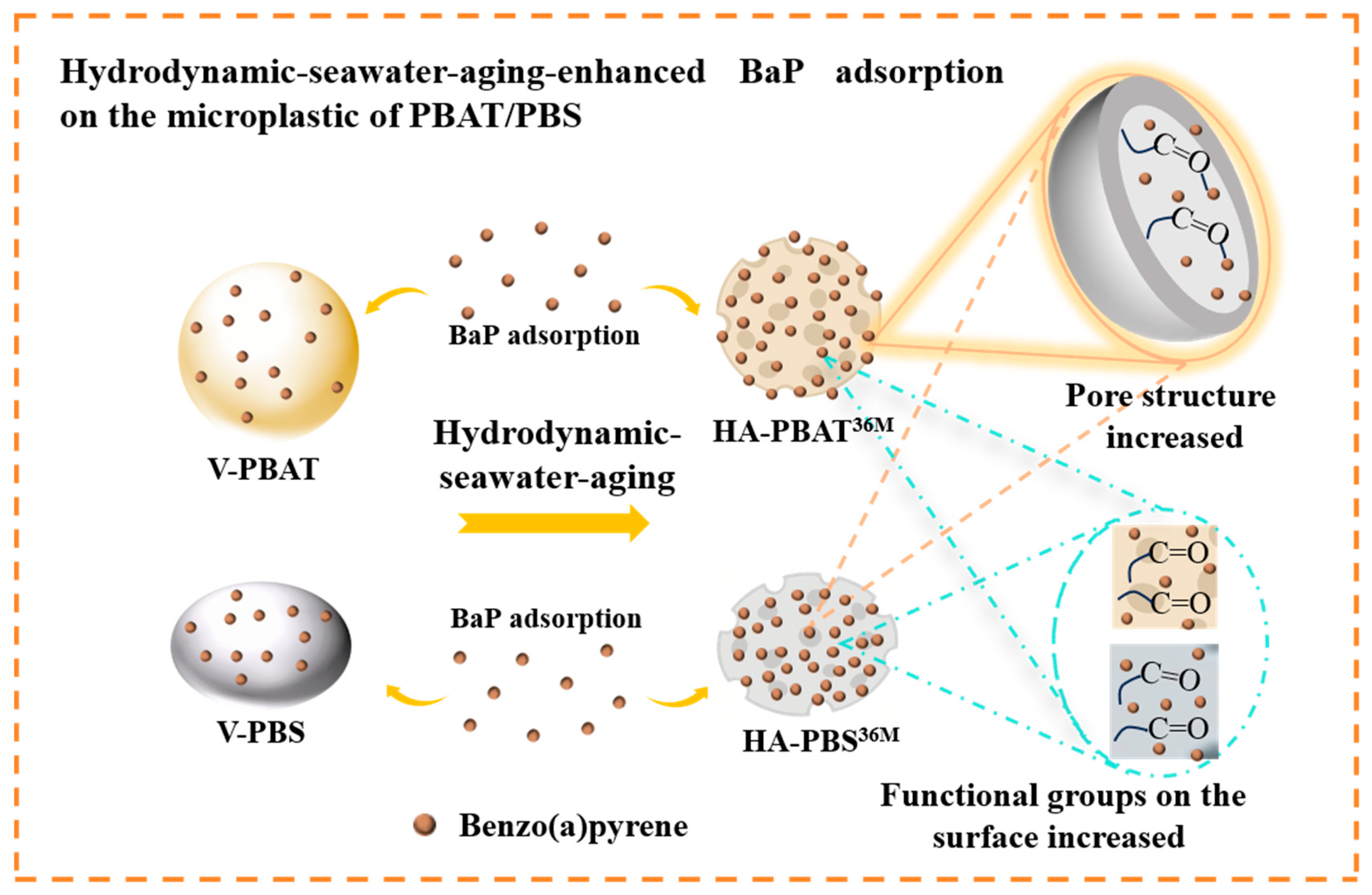

3.5. Mechanisms of BaP Adsorption onto Hydrodynamically Aged PBAT/PBS MPs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PBAT | Poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) |

| PBS | Poly(butylene succinate) |

| BaP | Benzo(a)pyrene |

| MPs | Microplastics |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller |

| FT-IR | Fourier transform infrared |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

Appendix A

| Type | BET Surface Area (m2/g) | Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Pore Size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| V-PBAT | 0.1872 | 0.000151 | 3.2300 |

| HA-PBAT36M | 0.1926 | 0.000159 | 3.3103 |

| V-PBS | 0.1920 | 0.000168 | 3.3046 |

| HA-PBS36M | 0.2475 | 0.000191 | 2.9703 |

| V-PE | 0.1875 | 0.000144 | 3.0697 |

| HA-PE36M | 0.1616 | 0.000158 | 3.8042 |

| Type | O 1s | C 1s | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C=O (eV) | C-O (eV) | C=O (eV) | C-O (eV) | C-C/C-H (eV) | |

| V-PBAT | 531.91 | 533.14 | 288.78 | 286.09 | 284.8 |

| HA-PBAT36M | 531.98 | 533.21 | 288.75 | 286.2 | 284.8 |

| V-PBS | 532.05 | 533.36 | 288.68 | 286.12 | 284.8 |

| HA-PBS36M | 532.25 | 533.55 | 288.79 | 286.13 | 284.8 |

| V-PE | 531.82 | 533 | 288.32 | 286.62 | 284.8 |

| HA-PE36M | 532.2 | 533.5 | 288.25 | 286.14 | 284.8 |

References

- Ali, N.; Khan, M.H.; Ali, M.; Sidra; Ahmad, S.; Khan, A.; Nabi, G.; Ali, F.; Bououdina, M.; Kyzas, G.Z. Insight into microplastics in the aquatic ecosystem: Properties, sources, threats and mitigation strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 913, 169489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Yang, W.; Hedenqvist, M.S. Plastic pollution amplified by a warming climate. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, S.; Cui, Y.; Brahney, J.; Mahowald, N.M.; Li, Q. Long-distance atmospheric transport of microplastic fibres influenced by their shapes. Nat. Geosci. 2023, 16, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, X.; Bank, M.S.; Dong, T.; Fang, J.K.; Leusch, F.D.L.; Rillig, M.C.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Xia, Y.; et al. The “Microplastome”—A holistic perspective to capture the real-world ecology of microplastics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 4060–4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, B.; Shi, H.; Ding, Y.; Chen, H.; Yuan, F.; Liu, R.; Zou, X. The processes and transport fluxes of land-based macroplastics and microplastics entering the ocean via rivers. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 466, 133623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, M.; Shankar, S.; Goel, D.; Singh, S.; Rahul, J.; Rachna, K.; Singh, J. Microplastics pollution in the marine environment: A review of sources, impacts and mitigation. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 209, 117109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz, R.; Rahman, M.S. Microplastics in coastal and marine environments: A critical issue of plastic pollution on marine organisms, seafood contaminations, and human health implications. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 18, 100663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Ding, J.; Yang, Y.; Huang, H.; Di, Y. Trophic-transferred hierarchical fragmentation of microplastics inducing distinct bio-adaptations via a microalgae-mussel-crab food chain. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 489, 137620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafa, N.; Ahmed, B.; Zohora, F.; Bakya, J.; Ahmed, S.; Ahmed, S.F.; Mofijur, M.; Chowdhury, A.A.; Almomani, F. Microplastics as carriers of toxic pollutants: Source, transport, and toxicological effects. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 343, 123190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleye, A.T.; Bahar, M.M.; Megharaj, M.; Fang, C.; Rahman, M.M. The Unseen threat of the synergistic effects of microplastics and heavy metals in aquatic environments: A Critical review. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2024, 10, 478–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Xu, D.; Yang, X.; Hu, J. Microplastics and PAHs mixed contamination: An in-depth review on the sources, co-occurrence, and fate in marine ecosystems. Water Res. 2024, 257, 121622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcharla, E.; Vinayagam, S.; Gnanasekaran, L.; Soto-Moscoso, M.; Chen, W.; Thanigaivel, S.; Ganesan, S. Microplastics in marine ecosystems: A comprehensive review of biological and ecological implications and its mitigation approach using nanotechnology for the sustainable environment. Environ. Res. 2024, 256, 119181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.S.; Chang, H.; Zheng, L.; Yan, Q.; Pfleger, B.F.; Klier, J.; Nelson, K.; Majumder, E.L.W.; Huber, G.W. A review of biodegradable plastics: Chemistry, applications, properties, and future research needs. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 9915–9939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binda, G.; Kalčíková, G.; Allan, I.J.; Hurley, R.; Rodland, E.; Spanu, D.; Nizzetto, L. Microplastic aging processes: Environmental relevance and analytical implications. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 172, 117566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutkar, P.R.; Gadewar, R.D.; Dhulap, V.P. Recent trends in degradation of microplastics in the environment: A state-of-the-art review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2023, 11, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ou, Q.; van der Hoek, J.P.; Liu, G.; Lompe, K.M. Photo-oxidation of micro- and nanoplastics: Physical, chemical, and biological effects in environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 991–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zou, S.; Li, P. Aging of plastics in aquatic environments: Pathways, environmental behavior, ecological impacts, analyses and quantifications. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 341, 122926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Kvale, K.F.; Zhu, L.; Zettler, E.R.; Egger, M.; Mincer, T.J.; Amaral-Zettler, L.A.; Lebreton, L.; Niemann, H.; Nakajima, R.; et al. The distribution of subsurface microplastics in the ocean. Nature 2025, 641, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; He, X. Occurrence and possible sources of antibiotic resistance genes in seawater of the South China Sea. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2024, 18, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Noori, R.; Abolfathi, S. Microplastics in freshwater systems: Dynamic behaviour and transport processes. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 205, 107578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Feng, Y.; Lu, J.; Wu, J.; Boman, B.J. Enhanced interfacial behaviors of benzo(a)pyrene on the petroleum-based degradable plastics endured long-term bio-aging. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 73, 107632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Sun, L.; Qin, Q.; Sun, Y.; Yang, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Gao, G.; Xue, Y. The adsorption process and mechanism of benzo[a]pyrene in agricultural soil mediated by microplastics. Toxics 2024, 12, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, C. Migration and fate of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in bioretention systems with different media: Experiments and simulations. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2024, 18, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Charpak, Y.D.; Kansara, H.J.; Lodge, J.S.; Eddingsaas, N.C.; Lewis, C.L.; Trabold, T.A.; Diaz, C.A. Quantitative methodology for poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT) microplastic detection in soil and compost. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Qin, Q.; Zhang, X.; Ma, J. Characteristics and adsorption behavior of typical microplastics in long-term accelerated weathering simulation. Environ. Sci. Proc. Impacts 2024, 26, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorasan, C.; Edo, C.; González-Pleiter, M.; Fernández-Piñas, F.; Leganés, F.; Rodríguez, A.; Rosal, R. Ageing and fragmentation of marine microplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 827, 154438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Xu, A. Seawater accelerated the aging of polystyrene and enhanced its toxic effects on caenorhabditis elegans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Hale, R.C.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, F.; Wu, Y.; Liang, X.; Liu, Y.; Tan, H.; Chen, D. Sorption of representative organic contaminants on microplastics: Effects of chemical physicochemical properties, particle size, and biofilm presence. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 251, 114533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Li, J.; Wang, G.; Luan, Y.; Dai, W. Adsorption behavior of organic pollutants on microplastics. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 217, 112207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagstaff, A.; Petrie, B. Enhanced desorption of fluoxetine from polyethylene terephthalate microplastics in gastric fluid and sea water. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Hua, W.; Lu, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, C. Adsorption and desorption of nonylphenol on the biodegradable microplastics in seawater. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 476, 143778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucking, C.; Wood, C. The effect of postprandial changes in pH along the gastrointestinal tract on the distribution of ions between the solid and fluid phases of chyme in rainbow trout. Aquacult. Nutr. 2009, 15, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Lu, J.; Wu, J. Effect of gastric fluid on adsorption and desorption of endocrine disrupting chemicals on microplastics. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2021, 16, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Takada, H.; Yamashita, R.; Mizukawa, K.; Fukuwaka, M.; Watanuki, Y. Facilitated leaching of additive-derived PBDEs from plastic by seabirds’ stomach oil and accumulation in tissues. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 49, 11799–11807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hua, X.; Lu, J.; Wu, J.; Feng, Y. Degradable plastics could help to protect the marine environment: Proof based on pollutant surface behaviors. New J. Chem. 2025, 49, 9829–9837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Sui, Q.; Zhou, Y. Mechanism and characterization of microplastic aging process: A review. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2023, 17, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yu, F.; Ma, J. Sorption behavior and mechanism of hydrophilic organic chemicals to virgin and aged microplastics in freshwater and seawater. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 246, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiki, C.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ifon, B.E.; Qin, D.; Chabi, K.; Yu, C.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, Q. Induced aging, structural change, and adsorption behavior modifications of microplastics by microalgae. Environ. Int. 2022, 166, 107382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ma, Y.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Shen, A.; Niu, Z.; Chen, Q.; Chen, B. Biofilm-mediated mass transfer of sorbed benzo[a]pyrene from polyethylene to seawater. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 374, 126257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Wu, X.; Yuan, S.; Lai, C.; Bian, S.; Yu, W.; Liang, S.; Hu, J.; Huang, L.; Duan, H.; et al. A potential threat from biodegradable microplastics: Mechanism of cadmium adsorption and desorption in the simulated gastrointestinal environment. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2024, 18, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, A.; Chen, S.; Liang, X.; Li, L.; Song, Y.; Lv, M.; Liang, F.; Zhou, W. Influence of microplastic aging on the adsorption and desorption behavior of Ni (II) under various aging conditions. Environ. Geochem. Health 2025, 47, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cid-Samamed, A.; Diniz, M.S. Recent advances in the aggregation behavior of nanoplastics in aquatic systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emecheta, E.E.; Borda, D.B.; Pfohl, P.M.; Wohlleben, W.; Hutzler, C.; Haase, A.; Roloff, A. A comparative investigation of the sorption of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to various polydisperse micro- and nanoplastics using a novel third-phase partition method. Microplast. Nanoplast. 2022, 2, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, P.; Qu, G.; Jing, J.; Zhang, T.; Shi, H.; Zhao, Y. Insight into the characteristics and sorption behaviors of aged polystyrene microplastics through three type of accelerated oxidation processes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 407, 124836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, Z.; Niu, J. Temperature-dependent sorption of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on natural and treated sediments. Chemosphere 2011, 82, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von, O.B.; Kördel, W.; Klein, W. Sorption of nonpolar and polar compounds to soils: Processes, measurements and experience with the applicability of the modified OECD-Guideline 106. Chemosphere 1991, 22, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zheng, L.; Huang, H.; Tian, Y.C.; Gong, Z.; Liu, P.; Wu, X.; Li, W.T.; Gao, S. Formation of nano- and microplastics and dissolved chemicals during photodegradation of polyester base fabrics with polyurethane coating. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 1894–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, E.; Wiman, C.; Muñoz, S.; Law, K.L.; Stubbins, A. Sunlight-driven photochemical removal of polypropylene microplastics from surface waters follows linear kinetics and does not result in fragmentation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 5461–5471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Feng, Y.; Hua, X.; Lu, J.; Wu, J. Hydrodynamic Aging Process Altered Benzo(a)pyrene Adsorption on Poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) and Poly(butylene succinate) Microplastics in Seawater. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411344

Liu X, Feng Y, Hua X, Lu J, Wu J. Hydrodynamic Aging Process Altered Benzo(a)pyrene Adsorption on Poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) and Poly(butylene succinate) Microplastics in Seawater. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411344

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xiaotao, Yuexia Feng, Xueting Hua, Jian Lu, and Jun Wu. 2025. "Hydrodynamic Aging Process Altered Benzo(a)pyrene Adsorption on Poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) and Poly(butylene succinate) Microplastics in Seawater" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411344

APA StyleLiu, X., Feng, Y., Hua, X., Lu, J., & Wu, J. (2025). Hydrodynamic Aging Process Altered Benzo(a)pyrene Adsorption on Poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) and Poly(butylene succinate) Microplastics in Seawater. Sustainability, 17(24), 11344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411344