Abstract

The long-standing separation of agro-pastoral relations has adversely affected the agricultural economy and ecology, hindering sustainable agricultural development. The process of reconstructing agro-pastoral relations involves moving from separation to reintegration. To further verify the scientific validity of reconstructing agro-pastoral relations to improve economic and ecological benefits and enhance the capacity for sustainable agricultural development in the major corn-producing areas of Northeast China, this study used survey data from 521 sample farmers in Jilin Province, China, collected during the agricultural production cycle from 2020 to 2022. Using an endogenous switching regression (ESR) model and a counterfactual scenario, the integrated crop–livestock family farm (ICFF) model was shown to have a comparative advantage in improving economic and ecological benefits. The ICFF model can serve as a foundation for reconstructing agro-pastoral relations, thereby enhancing sustainable agricultural development capacity. Heterogeneity analysis indicates that larger-scale cultivated land, intensive cultivated land management, and higher education have a more significant impact on farmers’ choice of the ICFF model. To promote the restructuring of agro-pastoral relations through the ICFF model, farmers should be encouraged and supported to standardize the transfer of farmland, engage in livestock farming according to the principle of land-based livestock management, implement large-scale and intensive management, improve agricultural production technologies and improved varieties, strengthen publicity on the positive role of integrated crop-livestock management, and improve the financial support system.

1. Introduction

Based on the general laws of agricultural development and the experiences of agrarian modernization in developed countries, agrarian green and sustainable development is an essential characteristic of agricultural modernization [1]. It aims to establish a material and energy circulation mechanism within the agrarian production units or between different units, enabling agricultural waste to be recycled and reused, gradually forming a trend of reducing external inorganic agricultural production materials and optimizing agricultural ecology [2,3,4], and accelerating the effective connection between traditional agriculture and modern agriculture. In agrarian production practices, the combination of planting and breeding is a commonly adopted production and operational form.

Currently, China is transitioning from traditional to modern agriculture. Agricultural development faces structural contradictions, including ecological degradation, poor sustainability, and insufficient momentum to raise farmers’ incomes [5,6]. These are adverse effects arising from the long-term separation of agriculture and animal husbandry, and the relationship between the two is gradually becoming more distant. From a longitudinal perspective, the separation of agriculture and animal husbandry has disrupted the energy circulation between the spatial level and the internal operational structure of agriculture and animal husbandry [7]. Importantly, crop residue produced during the production process contains fibers, crude protein, and organic acids [8], which are suitable for animal feed [9]. Embedding crop residues in the animal husbandry breeding process not only enriches the breeding feed structure but also, to some extent, mitigates the adverse effects of straw returning to the field. However, the proportion of farming households participating in integrated crop and livestock farming has decreased from 71.00% in 1986 to 12.00% in 2017 [10]; thus, the use of straw as feed has declined. Against the background of tightening agricultural ecological environment policies, straw is usually returned to the field. However, continuous returns to the field, coupled with the cold climate in Northeast China, have led to straw accumulation due to insufficient decomposition, resulting in low seedling emergence and pest and disease problems [11], which have reduced farmers’ incomes. In terms of animal husbandry, the private marginal benefit of farmers participating in the resource utilization of manure is far less than the cost of pollution control and the loss of their environmental rights [12,13]. This undoubtedly increases the operating expenses of small-scale and individual farmers, accelerates the withdrawal of animal husbandry from family farming, narrows the channels for farmers to increase their income, and blocks farmers from using manure to maintain farmland under the family farming mechanism, thereby leading to a decline in farmland quality. Large-scale livestock enterprises face significant pressure on manure disposal, increasing the potential for agricultural non-point source pollution [14]. In a series of policies on agricultural restructuring, farmland quality protection, and the modernization of animal husbandry, the Chinese government has gradually adopted the integration of crop farming and animal husbandry as an effective measure to promote agricultural modernization and improve the environment. In particular, the “Guiding Opinions of the Ministry of Agriculture on Accelerating the Development of Modern Animal Husbandry in the Northeast Grain-Producing Areas” regard the integration of crop farming and animal husbandry as a fundamental principle guiding the development of modern animal husbandry in Northeast China. It is intended to improve the level of integrated agricultural and animal husbandry development and sustainable development capacity by integrating crop farming and animal husbandry. Jilin Province is located in the hinterland of the main corn-producing area in Northeast China. It faces pressure from straw disposal due to high corn yields [15] and the potential for non-point source pollution from the rapid expansion of large-scale beef cattle farms in recent years. This is the result of the separation of agriculture and animal husbandry and hinders the sustainable development of agriculture. Therefore, whether the reconstruction of the agro-pastoral relations can effectively improve the adverse effects of the separation of agriculture and animal husbandry at this stage is worthy of further study.

Looking at the history and current status of agricultural development in most countries, in the current commercialized agricultural system, crop farming and livestock production have largely spatially decoupled [16]. This isolated, high-input production system exacerbates the challenges of sustainable development [17]. Therefore, it is necessary to adjust the agricultural production and management structure to further promote agricultural modernization. Existing research has shown that integrated crop livestock systems (ICLSs) can improve the sustainability of agricultural production, including the sustainable development of the agricultural environment [18] and the economy [19,20]. Establishing an integrated relationship between crop farming and livestock farming has been adopted as a strategy for protecting the environment and improving resource utilization efficiency [21], as well as an agricultural production practice to decrease non-agricultural inputs, enhance soil quality, and reduce farmers’ costs [22]. For example, American agriculture has undergone a transformation from numerous small, diversified farms to large-scale, high-energy-consuming farms, and then to integrated crop–livestock systems. This is the result of changes in productivity, market demand, and the direction of agricultural development over time [23]. Currently, agro-pastoral integrated systems still dominate in Australian agricultural areas, and the history of Australian agricultural development has shown that agro-pastoral integrated systems may be an effective measure for developed agricultural economies to address the many new pressures on agricultural development [24]. Stark et al. found, through a survey in Southwestern France, that agro-pastoral integrated systems can effectively improve the resilience of agricultural systems in the face of climate change and economic crises and serve as a strategy to promote the ecological transformation of agriculture [25]. The existing literature features relatively thorough research on agro-pastoral integrated systems. It confirms the superiority of agro-pastoral integrated systems in realizing the efficient utilization of agricultural waste, enriching the feed structure of livestock, improving soil quality [21], and promoting the sustainable and coordinated development of the agricultural economy and ecological environment [26]. However, research on the implementation of agro-pastoral relationship reconstruction in the main corn-producing areas of Northeast China remains insufficient, lacking demonstration of the carriers on which it relies and empirical testing of the agro-pastoral relationship reconstruction model to improve agricultural economic and ecological benefits. Therefore, the marginal contribution of this paper is to focus on the main corn-producing area in Northeast China, use micro-survey data, and employ theoretical and empirical analysis methods to demonstrate the basic carriers and practical significance of implementing agro-pastoral relations in this region, providing theoretical support and practical reference for the reconstruction of agro-pastoral relations in other agricultural areas.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Part Two analyzes the practical significance of reconstructing the agro-pastoral relationship from a theoretical and logical perspective, as well as the theoretical feasibility of the ICFF model as a vehicle for this reconstruction. Part Three introduces the sample selection method and scope, variable setting, and empirical analysis methods. Part Four presents descriptive statistics and an analysis of the empirical results for the sample data. Part Five presents a discussion. Part Six presents the conclusions and policy recommendations.

2. Theoretical Analytical Framework for the Reconfiguration of the Relationship Between Agriculture and Animal Husbandry

The integration of agriculture and animal husbandry is not a phased assessment intended to promote agricultural modernization, but a choice made in accordance with the laws of agricultural development. Unlike the natural integration of agriculture and animal husbandry that emerged in traditional agricultural stages due to limitations in productivity and production resources, the reconfiguration of agro-pastoral relations described here has undergone significant changes in operational scale and integration methods. It is promoted jointly at the macro and micro levels by the government and multiple operating entities [27]. Based on macro-level analysis, a rational layout of diversified and composite breeding and farming bases is achieved through spatial integration of the planting and animal husbandry industries, enabling the reconfiguration of agro-pastoral relations. The overlap of planting and animal husbandry in spatial layout is conducive to promoting and strengthening the inherent connection formed by input factors between the industries, and the industrial integration within the space is beneficial to saving production costs from an economic benefit perspective and converting agricultural waste into resources locally from an ecological benefit perspective, thereby alleviating environmental pressure [28,29,30].

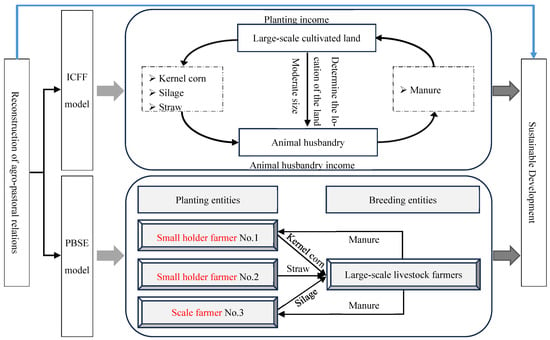

Further analysis reveals that the integration between the ICFF model and the planting and breeding single entity integrated management (PBSE) model for planting and breeding is the concrete manifestation of integration between the agricultural and animal husbandry industries at the macro level. There is a close connection between them. The ICFF model is primarily operated by farmers and is based on large-scale land cultivation. They reasonably arrange the proportion of planting and animal husbandry operations within the family operation framework according to the principle of “determining breeding based on land”, ensuring that farmers obtain an operating income not lower than the average disposable income of urban residents, and ensuring that agricultural waste is fully and rationally utilized within the agricultural production mechanism of the family. This judgment is based on the current basic conditions of agriculture in China, its system, and the laws governing modern agricultural development. Another model reconfiguring the relationships between agriculture and animal husbandry is the PBSE model. Small farmers still account for the majority of agricultural operating entities in China [31]. Therefore, in the process of reconfiguring the relationships between agriculture and animal husbandry, such entities should be fully considered so that they can all use a moderately sized ICFF model. On the other hand, livestock farms exhibit characteristics of scale and intensification. However, the existing agricultural land system cannot provide matching farmland for their scale, which is necessary to establish single-entity-operated family farms that combine breeding and farming. Therefore, a multi-party integration relationship can be established between large-scale livestock farms and small farmers to reconfigure agricultural and animal husbandry relationships (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theoretical analysis framework diagram.

A comparative analysis of the production and management mechanisms of the two agricultural-pastoral relationship reconstruction models revealed the following: Firstly, the ICFF model is mainly operated by individual large-scale farmers. Within the family-operated structure, they also engage in both agriculture and animal husbandry, which helps increase income levels and enables the household income to reach modern standards. On the other hand, the use of straw, manure, and other production inputs can effectively reduce feed and fertilizer costs and the cost of harmless manure disposal while also yielding positive externalities from improved farmland quality [32].

Secondly, the PBSE model involves cooperation among different types of entities, which may increase transaction costs or affect the depth of integration and production efficiency. According to Oliver Williams’ transaction cost theory, the transaction costs generated in this model mainly include information asymmetry costs and execution costs. This model involves a single livestock farmer cooperating with multiple crop farmers, making it challenging to establish strict contractual relationships between them. On the one hand, it is difficult for livestock farmers and crop farmers to coordinate supply and demand effectively. Specifically, the scale of livestock farming is not fixed in the long term; thus, their feed demand fluctuates. For crop farmers, by the time they learn of changes in livestock farmers’ feed demand, their planting activities may already be complete, making it impossible to adjust production decisions in time. This results in either direct sales of crop products by crop farmers or unmet feed needs of livestock farmers. Furthermore, crop farmers may be influenced by market prices, altering their production plans for silage corn or grain corn, thereby breaching the contract. Similarly, there is a possibility of a supply-and-demand imbalance in the utilization of livestock manure, which significantly reduces agricultural production efficiency. On the other hand, the flow of feed and livestock manure between entities inevitably incurs transportation costs; the more entities involved, the higher those costs. In contrast, the ICFF model can rationally plan the scale of planting and breeding to balance supply and demand for feed grain production and livestock manure utilization, thereby significantly reducing the risk of information asymmetry and increasing agricultural production efficiency. Furthermore, transporting feed grains and manure within the family unit lowers transportation costs. Therefore, in agrarian production practice, restructuring of the agro-pastoral relations should be based on the ICFF model.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and Data

The micro-sample data presented in this article are based on a field survey conducted by the research team from July to August 2023 in 6 cities, 14 counties, and 52 administrative villages across the eastern, central, and western regions of Jilin Province, China. The primary reason for selecting Jilin Province as the survey sample area is that, like other provinces in Northeast China, Jilin’s agricultural structure is dominated by corn cultivation, making it a central corn-producing region. Corn, as an essential feed ingredient for livestock production, provides favorable conditions for developing animal husbandry and thus for reconstructing agro-pastoral relations, leveraging its production areas. However, the long-term separation between crop farming and animal husbandry has led to multiple adverse effects on the economy and environment. Furthermore, as a core corn-producing area in Northeast China, Jilin Province has developed a distorted planting structure dominated by corn, facing a severe straw disposal problem. In addition, the vigorous development of large-scale beef cattle farming in Jilin Province in recent years has, on the one hand, led to significant ecological and environmental pressure, and on the other hand, laid the foundation for the reconstruction of the agro-pastoral relations. Therefore, Jilin Province is a typical and representative sampling area. The administrative villages chosen for the survey are mainly engaged in agricultural activities, and their sizes and populations are relatively similar. A questionnaire survey method was used, with 10 households randomly selected from each administrative village for one-on-one interviews. The sample size was increased for three administrative villages because their populations were significantly larger than those of the other villages. The survey data included input and output factors in crop and livestock production, as well as characteristics of individual and household farmers. The surveyed farmers included crop growers, livestock farmers, integrated crop–livestock management entities, and part-time farmers. The agricultural production cycle surveyed spanned 2020 to 2022, collecting specific data on relevant indicators for each year. During this production cycle, most of the surveyed areas did not experience severe natural disasters or force majeure events. A total of 550 questionnaires were distributed, and 521 were returned, yielding a response rate of 94.73%.

3.2. Variables and Methods

3.2.1. Variable

① Dependent variable

The benefits of the agriculture–animal husbandry integration model serve as an effective indicator for evaluating the advantages and disadvantages of different integration models in the reconfiguration path of agro-pastoral relations. The reconfiguration of the relationship between agriculture and animal husbandry aims to achieve a balance between economic and ecological benefits in agricultural production. The cost–profit ratio is the ratio of the total profit of the production and operation entity to its total cost, reflecting the profitability of the farming production activities of the operating unit. It is an effective indicator for measuring economic benefits and also facilitates direct comparison among different integration models. At the ecological level, the primary environmental issues currently facing agricultural development are soil degradation and surface pollution from livestock manure. Utilizing livestock manure for land reclamation not only solves the problem of surface pollution it may cause, but also improves soil quality, thereby achieving agricultural ecological optimization. Therefore, using the proportion of manure application for land reclamation as an indicator of ecological benefits means using the area of cultivated land that uses manure application as a proportion of the total operating cultivated land area (Table 1).

Table 1.

Variable setting and descriptive statistics.

② Explanatory variable

The reconfiguration model of agro-pastoral relations is used as the explanatory variable, where 0 indicates that the farmers use the PBSE model—that is, under this mode, the farmers only engage in either planting or breeding production and establish relationships to ensure the supply of production materials such as feed grains and the utilization of straw and manure with other breeders or farmers, thereby achieving multi-party participation in the integration of agriculture and animal husbandry. In contrast, 1 indicates that the farmers use the ICFF model—that is, the farmers concurrently engage in planting and breeding. They can realize the supply and transformation of material resources within the family-operated structure, thereby integrating agriculture and animal husbandry through a single operating entity (Table 1).

③ Control variables

The selected control variables relate to agricultural and animal husbandry production processes, farmers’ characteristics, and village features. The area of cultivated land, crop yield per unit, and the scale of livestock breeding directly determine economic benefits and are directly related to the production of straw and livestock manure, as well as the total amount of manure that the cultivated land can accommodate. These factors determine ecological benefits. Whether farmers engage in non-agricultural employment, the duration of farming, gender, educational level, and risk tolerance, to some extent, influence their participation in the business model of agricultural and animal husbandry integration, thereby affecting economic and ecological benefits (Table 1).

3.2.2. Methods

To further verify the rationality and scientificity of the ICFF model as the basic carrier for reconfiguring the agro-pastoral relations, combined with micro-sample data from the field research, an empirical analysis method was adopted for demonstration. The reconfiguration of agro-pastoral relations requires the government to design policies from a macro perspective and to promote their implementation through micro-level operating entities, such as farmers. That is, the specific executors of the reconfiguration of agro-pastoral relations should primarily be farmers and other operating entities. From the perspective of agricultural operating entities, reconfiguring the agro-pastoral relations involves adjusting operational methods and adopting an integrated farming and breeding model. This includes the ICFF model and the PBSE model. For farmers, the choice of operation mode is based on the principle of maximizing benefits—whether to integrate into the framework of the reconfiguration of agro-pastoral relations, where the farmers’ rational choice is based on market conditions, policy conditions, and family resource endowments—rather than a random production decision. The choice of the agro-pastoral relationship reconstruction model by farmers may be influenced by observable variables such as the cultivated land area, livestock scale, farmer age, and gender, as well as unobservable variables, such as farmers’ risk tolerance and cognition. Therefore, self-selection and endogeneity biases may exist. Currently, the academic community commonly uses propensity score matching (PSM) and difference-in-differences (DID) methods to address selection bias and endogeneity. However, PSM cannot correct for selection bias due to unobservable factors, whereas the DID method imposes strict data requirements. Thus, this study uses the ESR model to overcome the problem of self-selection and constructs the following model:

Firstly, the factors influencing farmers’ choice of agro-pastoral relationship restructuring mode are estimated using the Probit model, and the decision equation is constructed as follows:

In Equation (1), represents the agricultural and livestock integration model chosen by the farmers. If > 0, then = 1, indicating that the farmer has chosen the ICFF model; if ≤ 0, then = 0, indicating that the farmer has not chosen the ICFF model. represents the variable that influences the farmer’s choice of the agro-pastoral relations reconstruction model, is the identification variable, and are coefficients, and is the random disturbance term.

Secondly, an equation is constructed to represent the choice of farmers to establish or not establish the ICFF model and verify the differences among various reconfiguration models of agro-pastoral relations:

In Equations (2) and (3), represents the benefit of farmers selecting the ICFF model. In contrast, represents the benefit that farmers derive from not selecting the ICFF model but opting instead for the PBSE model. is the control variable, is the coefficient, and is the random disturbance term.

Finally, using the estimated coefficients of the ESR model, a counterfactual scenario was constructed to calculate the average treatment effect of the path chosen by farmers to reconstruct their family farms by integrating crop and livestock farming.

The predicted benefit of farmers choosing the ICFF model are:

The predicted benefits for farmers who do not choose the ICFF model are:

The average treatment effect of the path chosen by farmers to reconstruct their family farms through crop-livestock integration.

In Equation (6), represents the expected benefits for farmers who select the ICFF model, encompassing both economic and ecological benefits. represents the counterfactual situation benefits for farmers who did not select the ICFF model, but instead opted for the PBSE model.

Similarly, the average treatment effect of the benefits of not choosing the ICFF model can be obtained:

In Equation (7), represents the benefit in the counterfactual scenario in which farmers do not choose the ICFF model—that is, the PBSE model as the primary operational model. represents the expected benefit of farmers who do not choose the ICFF model.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis of Input and Output Factors in the Agricultural Production Process

From the perspective of crop production, the differences in input costs for production materials, such as seeds, pesticides, and machinery, between the ICFF model and those operating the PBSE model are relatively small and within a reasonable range. This is primarily due to the relatively fixed and transparent pricing of these inputs and agricultural social services. However, significant differences exist between the two in terms of fertilizer, labor, and unit output value. Specifically, the ICFF model reduces fertilizer input costs by approximately 14.61%, labor input costs by approximately 35.89%, and unit output value by approximately 7.96% compared to those operating the PBSE model. Regarding fertilizer inputs, under the ICFF model, livestock manure is processed within the family and returned directly to the fields. This manure production accounts for a significant portion of cultivated land, and the long-term application of organic fertilizers improves soil quality, thereby reducing the demand for chemical fertilizers to some extent. Under the integrated model of planting and breeding, however, the supply–demand relationship between planting and breeding is influenced by factors such as the breeding sector’s manure production and the number of farmers who have established a synergistic relationship. This results in an unstable total manure supply for breeding, and thus, the planting sector still relies on chemical fertilizer inputs to maintain stable production. From the perspective of labor input costs, the ICFF model relies on family labor and does not engage in non-agricultural employment. However, planting sectors may utilize their off-season time to engage in non-agricultural employment. Therefore, during the agricultural production phase, hiring labor can shorten the production cycle and reduce the opportunity cost of participating in agricultural production. Furthermore, the planting sector encompasses large-scale, specialized operations, and hiring labor is unavoidable to meet the demands of the harvest season. Hired labor costs account for a significant proportion of total agricultural expenses. From the perspective of unit output value, the ICFF model achieves an approximately 7.96% increase compared to integrated planting sectors. This is likely due to the greater ecological benefits of organic fertilizer application, which directly reflect the higher soil organic matter content of cultivated land. Regarding straw utilization, the comprehensive straw utilization rate in the ICFF model reaches 94.71%, primarily through conversion into feed. Under the integrated model of planting and breeding, however, the comprehensive utilization rate of straw by planting entities was 86.60%, with straw being returned to the fields as the primary method. This discrepancy primarily arises because, under the ICFF model, straw can meet livestock feed needs and is directly converted and utilized within the family-run mechanism. In contrast, under the PBSE model, there may be information asymmetry between the supply and demand of planting and breeding entities. On the one hand, the conversion rate of straw into feed for planting entities may be affected by the scale of breeding by breeding entities; on the other hand, breeding entities may be less motivated to purchase straw from planting entities.

From the perspective of livestock breeding, the ICFF model has similar healthcare and insurance investments compared to those operating the PBSE model. Regarding livestock costs, those operating the ICFF model are approximately 25.37% higher than those operating the PBSE model. This is primarily due to the maturity, scale, and specialization of the livestock-only model, which enables the independent breeding and rearing of livestock, thereby reducing costs associated with these activities. Regarding livestock feed structure, the costs of concentrated feed, silage, and garnish for the ICFF model are lower than those operating under the PBSE model. This is primarily because, under the ICFF model, farmers can adjust their cropping decisions in response to livestock development needs. Crop products directly contribute to a variety of feed forms for livestock breeding, enabling self-production and sales within the family-run model, significantly reducing transaction costs. However, the integrated relationship between the planting entities and breeding entities may result in supply–demand imbalances due to differences in feed grain quantity and quality. Consequently, the breeding entities still require market purchases, increasing feed costs. In terms of unit output value, breeding entities’ output is approximately 21.71% higher than that of the ICFF model. This may be due in part to differences in feeding cycles and slaughter weights, and partly to the fact that breeding entities possess scientific and sophisticated management experience and feeding plans. Regarding the proportion of manure returned to fields, the ICFF model can directly return manure to nearby fields within the framework of family farming. However, the PBSE model, due to the involvement of multiple entities, faces the risk of unstable manure supply and demand (Table 2).

Table 2.

The economic and ecological benefits of different management models are reconstructed in the context of the relationship between agriculture and animal husbandry.

4.2. Analysis of the Results of Farmers’ Choice of the Reconfiguration Model of Agricultural and Pastoral Relations

The regression results show that the log-likelihood estimate is negative, indicating that the model parameters have a high degree of fit. The Wald test was significant at the 1% level, rejecting the null hypothesis that the choice and outcome equations were independent. 0 and 1 are significant at the p < 0.01 level, indicating that there is a selection bias in the sample data—that is, the decision of farmers to choose the agro-pastoral relations reconstruction model is the result of a rational choice, not random, which further verifies the rationality of choosing the ESR model. To address endogeneity, following Hu and Wang [33], the overall cognitive level of village-level farmers regarding the improvement in economic and ecological benefits from agro-pastoral integration was selected as an instrumental variable and introduced into the decision-making model. On the one hand, the overall cognitive level of village-level farmers is determined by each farmer. As rational economic agents and risk-averse groups, farmers are very cautious in adjusting their production and management decisions and often need to engage in multifaceted argumentation when making production decisions. Farmers’ choice of the agro-pastoral relationship reconstruction model is a significant adjustment to the family management structure. Only when it is confirmed that the marginal contribution of agro-pastoral integration to economic and ecological benefits meets their profit-maximization goals can they decide to adopt the agro-pastoral integration model, thereby satisfying the relevance principle of instrumental variables. On the other hand, the overall cognitive level of village-level farmers does not directly affect the economic and ecological benefits of different agro-pastoral relationship reconstruction models and, to a certain extent, excludes the impact of individual farmers adopting new technologies due to improved cognitive levels on economic and ecological benefits, thus satisfying the exogeneity principle of instrumental variables.

Regression was performed using Stata 17.0 software. The regression results of the decision-making equation showed that cultivated land area, crop yield per unit area, livestock breeding scale, and whether farmers participated in non-agricultural employment passed the significance test at the 1%, 10%, 5%, and 5% levels, respectively. Cultivated land area, crop yield per unit area, and livestock breeding scale were positively correlated with farmers’ choice of the ICFF model. In contrast, farmers’ participation in non-agricultural employment was negatively correlated with their choice of the ICFF model. As a modern agricultural system, integrated farming and animal husbandry differ significantly from the traditional agrarian model of integrated farming and livestock breeding, with their scale and management methods undergoing substantial changes. Large-scale cultivated land management, on the one hand, promotes economies of scale, improves agricultural production efficiency, increases agricultural operating profits, and provides capital accumulation for agricultural reproduction and business restructuring. On the other hand, large-scale cultivated land management has a strong capacity to handle manure and sewage, enabling operators to raise a certain number of livestock and reducing the potential non-point source pollution from these sources. Crop yield per unit area is linked to income; higher crop yields are associated with higher operating income. The integrated farming and livestock farming model typically involves farmers operating livestock alongside their crops. While livestock farming requires high initial investment and substantial capital, the scale and high yields of crop farming increase operating income, providing the financial support needed for the development of animal husbandry. Livestock farming represents a significant difference between the ICFF model and the traditional integration of cropping and livestock farming, where the cropping sector is the primary focus. Farmers adopting the integrated farming model must achieve a specific scale of livestock farming and establish a reasonable scale of cropping operations, thereby meeting the requirements of integrated farming within a modern agricultural system. There is a conflict between farmers’ participation in non-agricultural employment and livestock farming regarding labor utilization. Participating in non-agricultural jobs means that the family has no surplus labor to engage in livestock farming, thus leading them to abandon the ICFF model.

Analyzing individual farmer characteristics, household head education level, risk tolerance, and awareness of the economic and ecological benefits of agricultural and animal husbandry integration passed significance tests at the 5%, 10%, 1%, and 5% levels, respectively, and were positively correlated with farmers’ choice of the ICFF model. Higher levels of education were associated with greater ability to acquire the necessary skills for the ICFF model. Compared to monoculture or animal husbandry, integrated farming increases household risk, leading risk-averse farmers with low risk tolerance to avoid this model. Farmer awareness is a prerequisite for their production and management decisions. Only when farmers fully understand the ICFF model and ensure its marginal contribution to economic and ecological benefits will they choose this model, enhance the sustainability of family farming, and adapt to the development of modern agriculture.

Analyzing from the perspective of village-level control variables, the proportion of permanent rural households passed the 5% significance test, with a negative coefficient. The proportion of permanent rural households is usually directly related to rural population mobility and migration, thus determining the scale of arable land available for transfer. Generally speaking, the proportion of permanent rural households varies between villages; a higher proportion indicates that more households in the village rely on agriculture as their primary source of income, thereby reducing the scale of arable land available for transfer. This further restricts farmers from developing the ICFF model through land transfer (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3.

Regression results for the decision-making equation explaining farmers’ choice of the reconfiguration model for the agro-pastoral relations.

Table 4.

Estimation of the effect of reconstructing the relationship between agriculture and animal husbandry to achieve the benefit of integrating agriculture and animal husbandry.

4.3. A Comparative Analysis of Two Agricultural and Pastoral Integration Models in Terms of Economic and Ecological Benefits

The results of whether farmers choose the integrated farming and animal husbandry family operation model are mainly analyzed from the perspectives of economic and ecological benefits. The decision-making model is used to perform regression analysis from the viewpoint of economic and environmental benefits. Combined with the regression results of the resulting equation, the economic benefits of the restructured agro-pastoral relations model were significantly correlated with cultivated land area and crop yield per unit area. This indicates that cultivated land area and crop yield per unit area directly determine total crop output and are directly linked to household operating income. Larger cultivated land areas and higher crop yields contribute significantly to improved economic benefits. However, the marginal contribution of cultivated land area and crop yield per unit area to economic benefits was greater in the selected group than in the non-selected group. The livestock breeding scale only passed the 5% significance test, with a positive coefficient, indicating that, under the family management mechanism, combining livestock breeding with crop production can improve economic benefits. In contrast, in the PBSE model, not all farmers engage in livestock farming, leaving some households without operating income from livestock. The marginal contribution of the livestock farming scale to economic benefits is smaller than that of cultivated land area. The main reason is that, in the selected group, the livestock farming scale should be maintained within a reasonable proportion of the cultivated land area to avoid disorderly expansion of the farming scale, which can lead to livestock and poultry manure exceeding the cultivated land’s carrying capacity. Generally speaking, 10 hectares of cultivated land can support 120 pigs, 50 beef cattle, or 10 to 15 dairy cows [34]. Therefore, within the range of the proportion of cultivated land area and farming scale, the operating income of animal husbandry may be lower than that of crop farming. Whether farmers participate in non-agricultural employment in the selected group passed the 10% level of significance test, and the coefficient was negative, indicating that farmers’ participation in non-agricultural employment causes reduced economic benefits. A possible reason for this is the conflict between non-agricultural employment and livestock farming in terms of labor utilization. After farmers choose the family operation model that combines farming and breeding, if they continue to engage in non-agricultural employment, they will inevitably reduce the time they spend on livestock farming, which can negatively affect livestock operations. On the other hand, the non-agricultural employment options available to farmers at this stage are mainly labor-intensive industries, and the wage income obtained may be lower than the operating income from animal husbandry. The household head’s education level and risk tolerance both passed the 10% significance test in the selected group, with positive coefficients. This suggests that higher education enables farmers to master new technologies, thereby optimizing agricultural production and management methods, and enhancing production efficiency, ultimately leading to improved economic benefits. High risks are associated with high returns. The higher the farmer’s risk tolerance, the more likely they are to improve their technology and management methods, thereby achieving higher returns.

From the perspective of the ecological benefits generated by the restructured model of agro-pastoral relations, both cultivated land area and livestock breeding scale passed the 1% significance test in the selected group, with positive coefficients. This indicates that, under the ICFF model, large-scale cultivated land can support a specific scale of livestock breeding. This is reflected not only in the ability of cultivated land to accommodate the manure produced by livestock farming, thereby replenishing soil organic matter and improving farmland quality, but also in the adequate consumption of straw by livestock farming, alleviating the adverse effects of long-term straw return to the fields and transforming agricultural waste into a resource, thus achieving improved ecological benefits. In contrast, the scale of cultivated land area and livestock breeding did not pass the significance test in the non-selected group. This is mainly due to the loose coupling between planting and breeding entities in the single-agent integration model, which prevents maintaining a reasonable balance between the scales of cropping and breeding, as seen in the selected group. Consequently, it is difficult to efficiently utilize manure and straw across multiple entities, resulting in limited ecological benefits. Whether farmers participate in non-agricultural employment also passed the 5% significance test in the selected group, with a negative coefficient. The ICFF model improves ecological benefits by returning manure to the fields and converting straw into feed, thereby reusing agricultural waste as a production input. However, both returning manure to the fields and converting straw into feed require significant labor and time, which would otherwise limit the positive externalities generated by the utilization of agricultural waste. Among the individual characteristics of farmers, the educational level of the household head passed the 10% significance test, indicating that more highly educated farmers are more likely to prioritize agricultural ecological protection during agrarian production, achieving synergy between agrarian management and sustainable agricultural development by adjusting agricultural production techniques and management methods (Table 4).

4.4. Construction of an Alternative Scenario

The economic benefits of the two groups of samples, after eliminating sample selection bias, were calculated using the ESR model. The financial benefits of selecting the ICFF model, as the model for reconstructing the agro-pastoral relations, as well as the economic benefits of the counterfactual scenario in which these farms were not selected as the model, were also calculated. The results showed that both ATT and ATU passed the significance test at the 1% level, and the coefficients were positive. ATT’s estimates indicate that if farmers who have chosen the ICFF model switch to the PBSE model, their economic and ecological benefits will decrease by 21.60% and 18.65%, respectively. ATU’s estimates indicate that if farmers who have chosen the PBSE model switch to the ICFF model, their economic and ecological benefits will increase by 19.24% and 15.16%, respectively. This indicates that selecting the ICFF model as a vehicle for reconstructing the agro-pastoral relations can improve economic benefits. Similarly, it was also verified that the ICFF model can improve ecological benefits. Therefore, compared with the unselected group—the PBSE model—the ICFF model offers greater economic and ecological benefits. Therefore, the ICFF model should be relied upon as the basic vehicle for reconstructing agro-pastoral relations (Table 5).

Table 5.

The average treatment effect of the reconstruction path of the agro-pastoral relations on the integration benefit of agriculture and animal husbandry.

4.5. Robustness Test

The robustness of the regression results is tested by replacing the explanatory variable and reducing the sample size. First, the explained variable is replaced. In calculating the economic benefit indicator, the cost–profit ratio, agricultural subsidies were included in household income. This was based on the fact that agricultural subsidies are an essential source of income for farmers. The proportion of manure returned to cultivated land was replaced with the amount of chemical fertilizer applied per unit area as a measure of ecological benefit. The primary reason is that applying livestock and poultry manure to cultivated land replenishes soil organic matter, thereby theoretically reducing the need for chemical fertilizers. A significant factor contributing to the current decline in cultivated land quality is the long-term overuse of chemical fertilizers. Although chemical fertilizers can effectively provide nutrients for crop growth in the short term, they make it difficult to replenish soil organic matter effectively. Furthermore, agricultural production currently relies on additional fertilizers to maintain crop yields, further exacerbating the decline in cultivated land quality and making development unsustainable. Second, the sample size was reduced. In the survey sample, some administrative villages experienced flooding during the 2022 agricultural production cycle, severely impacting crop cultivation and resulting in a significant reduction in corn yield and, consequently, income, potentially affecting the regression results. A total of 27 households were affected by the floods. These households were excluded from the sample before regression testing for robustness.

Re-regression with replacement of the explained variables revealed robustness tests, showing that, under counterfactual scenarios, adopting the ICFF model can improve the cost–profit ratio and enhance economic efficiency. Furthermore, it can reduce fertilizer application per unit area, thereby improving soil quality and unlocking ecological benefits. Specifically, ATT’s estimates indicate that if farmers who have chosen the ICFF model switch to the PBSE model, their economic benefits will decrease by 22.00%. In comparison, fertilizer application will increase by 15.32% from an ecological perspective. ATU’s estimates indicate that if farmers who have chosen the PBSE model switch to the ICFF model, their economic benefits will increase by 21.50%. In comparison, fertilizer application will increase by 11.50% from an ecological perspective (Table 6). Regression was repeated with a reduced sample size, and the results remained significant, validating the model’s robustness. After excluding sample farmers whose agricultural production was affected by floods, the results showed that the ICFF model had a greater advantage in improving economic and ecological benefits (Table 7), further confirming the practical significance of the ICFF model as a basic vehicle for reconstructing agro-pastoral relations.

Table 6.

The robustness test results when replacing the dependent variable.

Table 7.

The robustness test results using the sample-size-reduction method.

4.6. Heterogeneity Analysis

This study conducted heterogeneity analysis by grouping farmers according to their cultivated land size, median number of plots, and education level. Given the scale effect that cultivated land size can create in agricultural production, farmers were divided into larger- and smaller-scale groups based on the median cultivated land size of 2.73 hm2. The heterogeneity analysis results showed that the average treatment effect was significant at the 1% level, indicating that the ICFF model generated greater economic and ecological benefits for farmers operating larger-scale cultivated land than for those operating smaller-scale cultivated land (Table 8). This may be because the scale effect of larger cultivated land can save production costs to some extent, thereby increasing agricultural profits. On the other hand, farmers operating larger-scale cultivated land typically rely on agriculture as their primary source of income, while farmers operating smaller-scale cultivated land are primarily engaged in non-agricultural employment, thus lacking the time and effort required for manure application, resulting in a lower proportion of manure application than among farmers operating larger-scale cultivated land.

Table 8.

Heterogeneity analysis based on cultivated land size grouping.

China’s arable land is characterized by fragmentation and dispersion, but at present, intensive management through land transfer is quite common among some farmers. To further verify the impact of varying degrees of arable land fragmentation on the economic and ecological benefits of the ICFF model, farmers were divided into intensive and dispersed groups based on the median number of arable land plots operated by respondents (5 plots). Heterogeneity analysis showed that the average treatment effect was significant at the 1% level, indicating that the ICFF model yields greater economic and ecological benefits for farmers with intensive arable land than for those with dispersed arable land (Table 9). A possible reason is that intensive arable land is easier to manage and arrange agricultural production activities uniformly, saving transportation costs and labor time incurred from moving between different plots. Especially in terms of manure application, which requires substantial labor and time, this fragmented arable land distribution will undoubtedly further increase labor and time inputs.

Table 9.

Heterogeneity analysis based on the number of plots.

During the transition from traditional to modern agriculture, the updating of agricultural technology and production management places higher demands on farmers’ qualifications. With the entry of a new generation of farmers into the agricultural industry, differences in education levels exist among Chinese farmers. To further verify the impact of farmers’ educational level on the economic and ecological benefits of operating the ICFF model, farmers were divided into a higher education group (high school or higher) and a lower education group (junior high or lower). Heterogeneity analysis showed that the average treatment effect was significant at the 1% level, indicating that the ICFF model operated by highly educated farmers generated better economic and ecological benefits than that operated by less educated farmers (Table 10). Generally speaking, farmers’ education level is linked to their overall quality; the higher the education level, the stronger their understanding and mastery of new agricultural technologies and management methods. The agrarian modernization transition is also a process of transforming agrarian technology and production methods. Farmers with higher levels of education can quickly learn and apply new production technologies, replacing traditional agrarian methods, thereby improving agricultural production efficiency and optimizing economic benefits. On the other hand, farmers with higher levels of education have a rational understanding of sustainable agricultural development and the protection of arable land quality, so they will pay attention to maintaining arable land and thus increase the proportion of manure returned to the field.

Table 10.

Heterogeneity analysis based on farmers’ education level.

5. Discussion

The reconstruction of agro-pastoral relations is typical of agricultural development in developed countries [23,24]. It is regarded as an efficient agricultural resource allocation model that helps reduce farm production costs, increase profits and efficiency, and reduce farm waste [35]. It provides a reference experience for many developing countries to promote green and sustainable agricultural development [36,37,38]. It is also applicable to resolving the dual paradox of China’s agricultural economic growth and environmental degradation. However, the reconstruction of agro-pastoral relations in China is not a complete replication of the successful experiences of developed countries, but rather an adaptive adjustment to specific national and agricultural conditions. As a major grain-producing region, the sustainable development of agriculture in Northeast China is closely linked to food security and agricultural modernization. The current stage of agricultural development contradictions faced by this region are universal and representative in China. The main corn-producing region in Northeast China has natural resource endowment advantages in developing planting and animal husbandry. Therefore, it is feasible to designate this region as a pilot area for reconstructing the agro-pastoral relations. Although this study demonstrates the superiority of the ICFF model as the primary basis for reconstructing agro-pastoral relations, it cannot be ignored that small farmers remain the main component of agricultural operators in China at present and for the foreseeable future [31,39]. They are an indispensable group in promoting the reconstruction of the agro-pastoral relations. Therefore, the role of the PBSE model in reconstructing agro-pastoral relations deserves attention. Large-scale farms or livestock enterprises should take the lead in establishing cooperative relationships with surrounding farmers based on the resource utilization of agricultural waste and the supply and demand of production materials [40]. This would reduce the spatial separation between crop farming and animal husbandry caused by the separation of agricultural and livestock management entities.

However, a practical difficulty in reconstructing agro-pastoral relations in Northeast China’s main corn-producing areas is the control over arable land use, which subjects farmers to strict regulations regarding the construction of livestock sheds. As a major grain-producing area, most arable land in Northeast China is protected by high-standard farmland and basic farmland, which are generally only usable for grain production [41]. Applying for general farmland for non-grain production also requires multiple levels of approval, posing a challenge for farmers who engage in both grain and animal husbandry.

In previous research, scholars generally agree on the role of agro-pastoral integration systems in promoting green and sustainable agricultural development [42,43,44,45]. Many scholars have begun to focus on how agro-pastoral integration systems can address the adverse effects of climate change on crop and livestock production and on seeking strategies to enhance sustainable development capabilities [46]. They have also confirmed the advantages of agro-pastoral integration systems in reducing agricultural greenhouse gas emissions and carbon sequestration [47,48], as well as improving soil structure and microorganisms [49]. This study focuses more on the role of agro-pastoral integration in improving economic and ecological benefits. Previous research has compared the dominant specialized cropping system with the modern integrated agro-pastoral system [50], demonstrating that the latter reduces dependence on external resources, lowers production costs and market risks, and is conducive to sustainable agricultural development—a view largely consistent with this study [51]. However, this study goes a step further, comparing the advantages of the two models within the agro-pastoral integrated framework and seeking a vehicle to promote the restructuring of agro-pastoral relations. This study empirically tests the scientific validity of the ICFF model in strengthening economic and ecological benefits and enhancing sustainable agricultural development capabilities. This study also demonstrates the model’s practical value as a basis for reconstructing agro-pastoral relations.

The limitations of this study lie in its small sample size, which limits the number of family farms operating the ICFF model and the number of farmers involved in the PBSE model, making it challenging to support effective grouping and regression analysis. The sample of farmers only included those from Jilin Province, the heart of Northeast China’s main corn-producing region. While this is representative, the lack of sample data from other agricultural areas and the limited panel data may overlook differences in the reconstruction of agro-pastoral relationships across regions. Data obtained through interviews may be subject to interviewer bias, as farmers’ memories may be distorted. Regarding the quantification of ecological benefits, direct observational data on soil quality are lacking. Therefore, future research will focus on expanding the sample data from Liaoning Province, Heilongjiang Province, and Eastern Inner Mongolia, appropriately increasing sample data from non-maize-producing areas to broaden the sample base, and conducting grouping analysis from multiple perspectives to further enhance the scientific rigor and soundness of the research results. To quantify ecological benefits, this study will focus on the application rate of livestock and poultry manure, soil nutrient measurements, and carbon emissions within the agricultural system.

6. Conclusions and Policy Suggestions

6.1. Conclusions

Based on survey data of sample farmers in Jilin Province, China, this study uses an ESR model to explore the impact and differences of the ICFF model on the improvement of economic and ecological benefits, and draws the following conclusions: Firstly, descriptive statistics on the ICFF model and the PBSE model show that, in the production stages of crop and livestock farming, the ICFF model has advantages over the PBSE model in terms of the economy of factor input and output, straw feed utilization, and manure return to the field. Secondly, farmers who choose the ICFF model can significantly improve economic and ecological benefits. The cultivated land area, crop yield per unit area, livestock farming scale, and participation in non-agricultural employment are factors influencing farmers’ choice of the integrated agro-pastoral management model. Farmers’ awareness of the economic and ecological benefits of restructuring the agro-pastoral relations promotes their choice of the ICFF model. Thirdly, the economic and ecological benefits of farmers choosing the ICFF model vary. From the perspective of cultivated land size heterogeneity, the ICFF model generated greater economic and environmental benefits for farmers operating larger-scale cultivated land than for those operating smaller-scale cultivated land. From the perspective of farmland fragmentation heterogeneity, the ICFF model generated greater economic and ecological benefits for farmers with intensive farmland than for those with dispersed farmland. From the perspective of farmer education heterogeneity, the ICFF model operated by higher-education farmers generated greater economic and ecological benefits than those operated by lower-education farmers. Therefore, the ICFF model is the fundamental vehicle for restructuring the agro-pastoral relations and enhancing the sustainable development capacity of agriculture.

6.2. Policy Recommendations

To advance the restructuring of the agro-pastoral relations in an orderly manner, priority should be given to the smooth implementation of the ICFF model. Therefore, the following policy recommendations are proposed: First, it is important to encourage and support large-scale crop farmers to engage in concurrent livestock farming, adhering to the principle of “livestock farming determined by land availability”. This includes allowing some capable smallholder farmers to expand their operations by transferring farmland and establishing appropriately sized integrated agro-pastoral family farms. To this end, it is necessary to establish and improve land management systems. Firstly, it is important to allow integrated agro-pastoral family farms to construct livestock sheds using land in a standardized manner. Under the premise of not violating the basic rural and farmland system and the “red line” for arable land, farmers can be appropriately allowed to use wood materials to build livestock sheds, ensuring that arable land has the capacity to resume production. Secondly, the land transfer market should be standardized, giving it a decisive role in land transfers, providing farmers with an information platform for arable land transfers, and establishing a credit list system. By standardizing the transfer of cultivated land, the scale of operations can be expanded and intensive management achieved. Thirdly, arable land reserves should be expanded, saline–alkali land should be developed and utilized, idle homesteads should be revitalized and reclaimed, and they should be included in the annual “balance between occupation and compensation” plan for arable land. Finally, a land use monitoring mechanism should be established to conduct regular spot checks on land use, especially by strengthening the supervision of land use by family farms that integrate crop farming and animal husbandry to ensure compliance with land use standards and by imposing appropriate penalties for violations.

Secondly, agricultural production techniques and improved crop varieties should be developed to increase yields. The government should collaborate with research institutions to accelerate the breeding of high-yielding crops and superior livestock breeds, thereby enhancing crop yields and livestock production, increasing farmers’ incomes, and enabling them to expand their operations or engage in animal husbandry. At the same time, the government should provide farmers with necessary technical guidance and promote new agricultural production technologies and methods.

Third, it is important to leverage new media platforms to promote the positive effects of integrated crop and livestock farming, further enhancing farmers’ understanding of its economic and ecological benefits and motivating them to choose this model.

Fourth, it is essential to improve the financial support system. Animal husbandry is a capital-intensive industry; therefore, farmers should be provided with diversified lending channels and low-interest or subsidized loans to meet their funding needs for expanding operations or adjusting their agricultural management structures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.X. and Q.G.; methodology, H.X. and Q.G.; software, H.X.; validation, H.X. and Q.G.; formal analysis, H.X.; investigation, H.X.; data curation, H.X.; writing—original draft preparation, H.X.; writing—review and editing, H.X. and Q.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China, grant number 20BJY147, and the Major Project of the National Social Science Foundation of China, grant number 20&ZD094.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be obtained by contacting the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yue, Q.; Guo, P.; Wu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C. Towards sustainable circular agriculture: An integrated optimization framework for crop-livestock-biogas-crop recycling system management under uncertainty. Agric. Syst. 2022, 196, 103347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, R.D.; Niles, M.; Gil, J.; Dy, P.; Reis, J.; Valentim, J. Policies for Reintegrating Crop and Livestock Systems: A Comparative Analysis. Sustainability 2017, 9, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, S.; Wiesmeier, M.; Sakamoto, E.; Hübner, R.; Cardinael, R.; Kühnel, A.; Kögel-Knabner, I. Soil organic carbon sequestration in temperate agroforestry systems—A meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 323, 107689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S.; Ying, Z. Enhancing agricultural productivity and food security through circular sustainability practices: A pathway to achieving sustainable development goal 2. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 389, 126237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, C.M.; Freire, D.; Abrantes, P.; Rocha, J.; Pereira, P. Agricultural land systems importance for supporting food security and sustainable development goals: A systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; You, X.; Sun, X.; Chen, J. Dynamic assessment and pathway optimization of agricultural modernization in China under the sustainability framework: An empirical study based on dynamic QCA analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 479, 144072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, K.M.; Muñoz-Araya, M.; Martinez, I.; Marshall, K.N.; Gaudin, A.C. Long-term integrated crop-livestock grazing stimulates soil ecosystem carbon flux, increasing subsoil carbon storage in California perennial agroecosystems. Geoderma 2023, 438, 116598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Goyal, S.; Reddy, M.S. Corn steep liquor as a nutritional source for biocementation and its impact on concrete structural properties. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 45, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koul, B.; Yakoob, M.; Shah, M.P. Agricultural waste management strategies for environmental sustainability. Environ. Res. 2022, 206, 112285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Zhang, B.; Wu, B.; Han, D.; Hu, Y.; Ren, C.; Zhang, C.; Wei, X.; Wu, Y.; Mol, A.P.J.; et al. Decoupling livestock and crop production at the household level in China. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, E.; Chen, G.; Qian, X.; Liu, Q.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, K.; Li, Z. Optimizing straw return to enhance grain production and approach carbon neutrality in the intensive cropping systems. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 248, 106447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, J.; Dabert, P.; Barrington, S.; Burton, C. Livestock waste treatment systems for environmental quality, food safety, and sustainability. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 5527–5536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampat, A.M.; Hicks, A.; Ruiz-Mercado, G.J.; Zavala, V.M. Valuing economic impact reductions of nutrient pollution from livestock waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassaletta, L.; García-Gómez, H.; Gimeno, B.S.; Rovira, J.V. Agriculture-induced increase in nitrate concentrations in stream waters of a large Mediterranean catchment over 25 years (1981–2005). Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 6034–6043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xue, S.; Xie, T. Value-taking for residue factor as a parameter to assess the field residue of field crops. J. China Agric. Univ. 2012, 1, 1–8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gu, B. Recoupling livestock and crops. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 102–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, R.D.; Ryschawy, J.; Bell, L.W.; Cortner, O.; Ferreira, J.; Garik, A.V.N.; Gil, J.D.B.; Klerkx, L.; Moraine, M.; Peterson, C.A.; et al. Drivers of decoupling and recoupling of crop and livestock systems at farm and territorial scales. Ecol. Soc. 2020, 25, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, C.; Ryschawy, J.; Martin, G. Reintegrating livestock onto crop farms: A step towards agroenvironmental sustainability? Agric. Syst. 2025, 227, 104356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, L.W.; Moore, A.D.; Thomas, D.T. Diversified crop-livestock farms are risk-efficient in the face of price and production variability. Agric. Syst. 2021, 189, 103050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.D.B.; Garrett, R.D.; Rotz, A.; Daioglou, V.; Valentim, J.; Pires, G.F.; Costa, M.H.; Lopes, L.; Reis, J.C. Tradeoffs in the quest for climate smart agricultural intensification in Mato Grosso, Brazil. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 064025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russelle, M.P.; Entz, M.H.; Franzluebbers, A.J. Reconsidering Integrated Crop–Livestock Systems in North America. Agron. J. 2007, 99, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryschawy, J.; Tiffany, S.; Gaudin, A.; Niles, M.T.; Garrett, R.D. Moving niche agroecological initiatives to the mainstream: A case-study of sheep-vineyard integration in California. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulc, R.M.; Franzluebbers, A.J. Exploring integrated crop–livestock systems in different ecoregions of the United States. Eur. J. Agron. 2014, 57, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, L.W.; Moore, A.D. Integrated crop–livestock systems in Australian agriculture: Trends, drivers and implications. Agric. Syst. 2012, 111, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, F.; Mettauer, R.; Ryschawy, J.; Grillot, M.; Cassagnes, A.; Shaqura, I.; Moraine, M. Strategies to advance the agroecological transition: Insights from a case study of sheep–crop integration in southwestern France. Agric. Syst. 2026, 231, 104514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Q.; Adamowski, J.; Cao, X.; Chen, D.; Xuanyuan, M.; Elbeltagi, A.; Dai, X. Managing agricultural crop and livestock land use for synergistic energy-economy-environment development: A hybrid multi-objective optimization approach under a waste-to-energy nexus. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 486, 144544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U.; Lai, L.; Ussiri, D.A.N.; Kumar, S.; Clay, S. Role of integrated crop-livestock systems in improving agriculture production and addressing food security—A review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2021, 5, 100190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Z.; McLean, T.; Clough, A.; Tocker, J.; Christy, B.; Harris, R.; Riffkin, P.; Clark, S.; McCaskill, M. Benefits, challenges and opportunities of integrated crop-livestock systems and their potential application in the high rainfall zone of southern Australia: A review. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 235, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante, B.O.; Villano, R.A.; Battese, G.E. Evaluating complementary synergies in integrated crop-livestock systems in Ghana. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2020, 47, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puech, T.; Stark, F. Diversification of an integrated crop-livestock system: Agroecological and food production assessment at farm scale. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 344, 108300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Song, Y. Income growth and inequality reduction through rural industrial integration: Evidence from small-scale farmers in China. J. Asian Econ. 2025, 100, 102009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, S.; Wang, D.; Shen, Z.; Liao, H.; Feng, G.; Hou, W.; Tian, C.; Gao, Q.; Wang, Y. Increased farm size combined with improved crop-livestock coupling enhance agricultural outputs while reducing environmental impacts. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 530, 146865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Wang, H. Study of the income effect of farmers’ cultivated land quality protection behavior based on rural household survey datain Jiangxi province. China Land Sci. 2024, 38, 68–76. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Liu, S.; Guo, Q. From “separation” to “reconstruction”: An analytical framework and empirical test for the adjustment of the relationship between agriculture and animal husbandry of farm households. Agric. Econ. Zemědělská Ekon. 2025, 71, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swastika, D.K.S.; Priyanti, A.; Hasibuan, A.M.; Sahara, D.; Arya, N.N.; Malik, A.; Ilham, N.; Sayekti, A.L.; Triastono, J.; Asnawi, R.; et al. Pursuing circular economics through the integrated crop-livestock systems: An integrative review on practices, strategies and challenges post Green Revolution in Indonesia. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruska, R.L.; Reid, R.S.; Thornton, P.K.; Henninger, N.; Kristjanson, P.M. Mapping livestock-oriented agricultural production systems for the developing world. Agric. Syst. 2003, 77, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryschawy, J.; Choisis, N.; Choisis, J.P.; Joannon, A.; Gibon, A. Mixed crop-livestock systems: An economic and environmental-friendly way of farming? Animal 2012, 6, 1722–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lin, J.; Tan, K.; Pei, Y.; Wang, X. Cooperation between specialized cropping and livestock farms at local level reduces carbon footprint of agricultural system: A case study of recoupling maize-cow system in South China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 348, 108406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Mao, H.; Dai, C. The role of new agricultural business entities in guiding smallholder farmers’ green production: Evidence from chemical fertilizer reduction in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 114, 107963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, G.; Hu, H. Surplus manure and barren croplands: Strategies for recycling livestock manure to rebuild crop-livestock linkages beyond the farm level. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2025, 17, 773–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Gao, M.; Fan, S.; Zhu, C. Impacts of high-standard farmland construction on farmers’ income in China: A comparative analysis of moderate-scale farmers and smallholders. Food Policy 2026, 138, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyraud, J.L.; Taboada, M.; Delaby, L. Integrated crop and livestock systems in Western Europe and South America: A review. Eur. J. Agron. 2014, 57, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaire, G.; Franzluebbers, A.; Carvalho, P.C.D.F.; Dedieu, B. Integrated crop–livestock systems: Strategies to achieve synergy between agricultural production and environmental quality. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 190, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Luan, W.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y. Environmental and economic benefits of carbon emission reduction in animal husbandry via the circular economy: Case study of pig farming in Liaoning, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 238, 117968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Han, C.; Shi, Z.; Li, J.; Luo, E. Rebuilding the crop-livestock integration system in China—Based on the perspective of circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 393, 136347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, A.; Marvuglia, A.; Gutierrez, T.N.; Weis, J.P.; Conter, G.; Zimmer, S. Sustainable farming strategies for mixed crop-livestock farms in Luxembourg simulated with a hybrid agent-based and life-cycle assessment model. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 386, 135759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Lu, Y.; Jenkins, A.; Ferrier, R.C.; Li, H.; Stenseth, N.C.; Hessen, D.O.; Zhang, L.; et al. Coupling of crop and livestock production can reduce the agricultural GHG emission from smallholder farms. iScience 2023, 26, 106798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Gonzalo, D.; Vaast, P.; Oelofse, M.; Neergaard, A.D.; Albrecht, A.; Rosenstock, T.S. Farm-scale greenhouse gas balances, hotspots and uncertainties in smallholder crop-livestock systems in Central Kenya. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 248, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambus, J.V.; Awe, G.O.; de Faccio Carvalho, P.C.; Reichert, J.M. Integrated crop-livestock systems in lowlands with rice cultivation improve root environment and maintain soil structure and functioning. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 227, 105592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Z.; Accatino, F.; Hang, S.; Lv, Y.; Ouyang, Z. Comparing specialised crop and integrated crop-livestock systems in China with a multi-criteria approach using the emergy method. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 127974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryschawy, J.; Martin, G.; Moraine, M.; Duru, M.; Therond, O. Designing crop–livestock integration at different levels: Toward new agroecological models? Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2017, 108, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).