Towards Sustainable Factories: A Systematic Review of Energy-Conscious Job-Shop Scheduling Models and Algorithms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations

2.1. Job-Shop Foundations

2.2. Energy Efficiency in Manufacturing Systems

- Economic: reducing energy costs and improving resource utilization to enhance competitiveness.

- Environmental: lowering carbon emissions, minimizing waste, and supporting regulatory compliance.

- Social: promoting sustainable industrial practices that contribute to broader societal goals, including job security, worker health, and alignment with the SDGs.

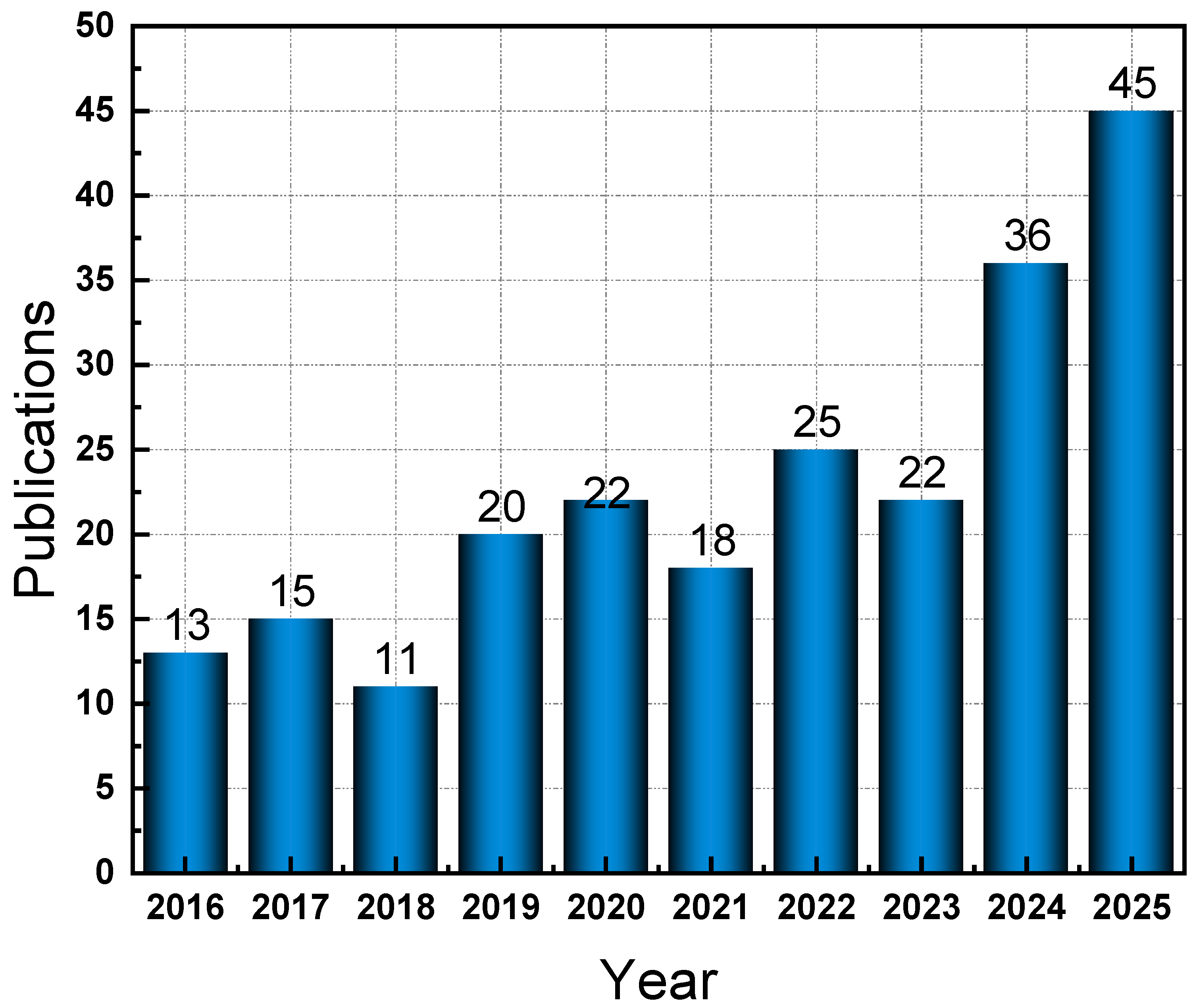

3. Review Methodology

- (1)

- An updated and expanded classification of energy-aware models that incorporates machine states, dynamic pricing, speed scaling, and renewable integration.

- (2)

- The first structured mapping of EEJSS research to U.N. Sustainable Development Goals and Industry 4.0 capabilities, clarifying the role of scheduling in low-carbon smart manufacturing.

- (3)

- A sector specific analysis that contextualizes findings in high-impact industries such as aerospace, automotive, and electronics.

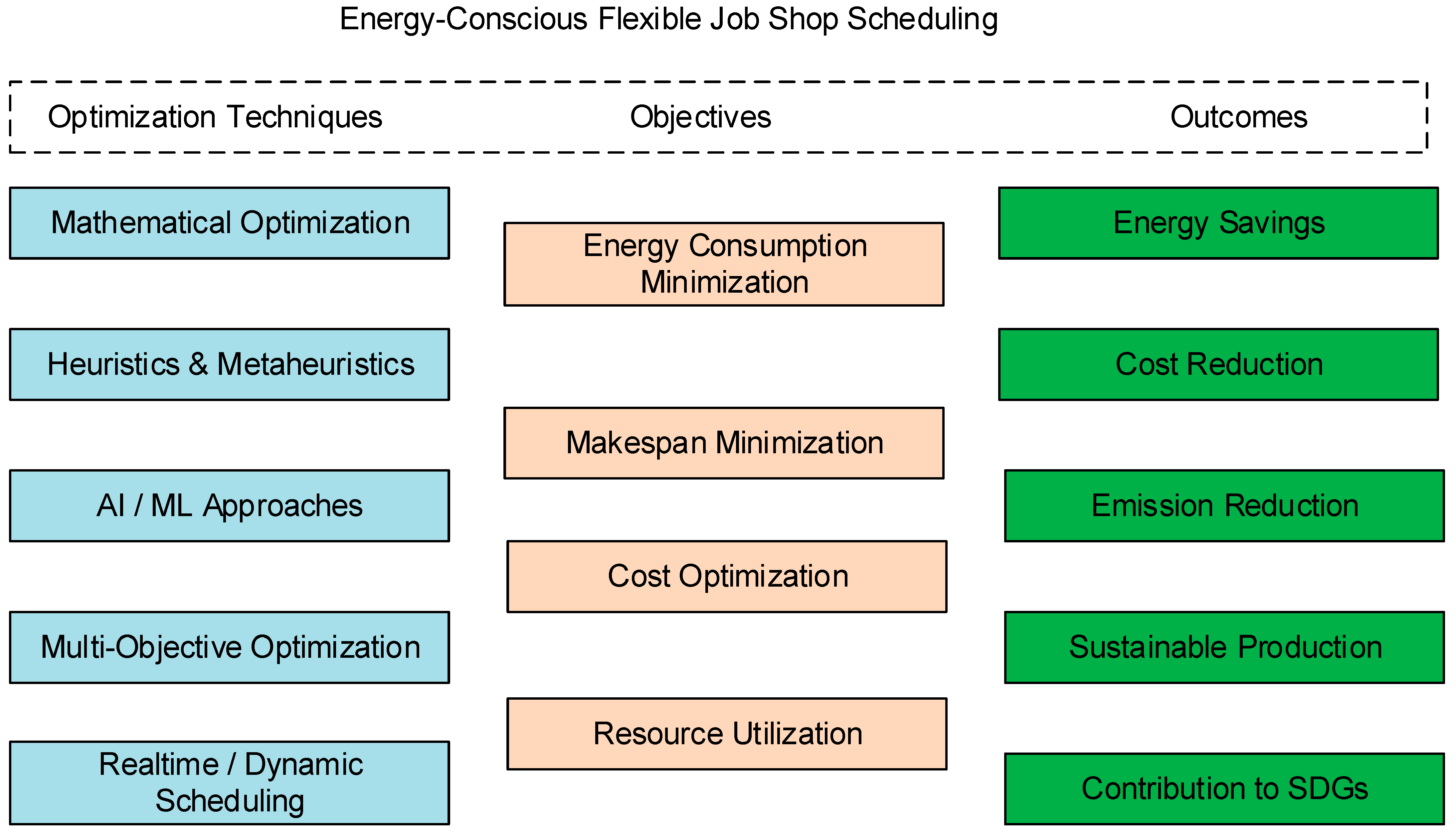

4. Methods for Energy-Efficient Job-Shop Scheduling

4.1. Problem Modeling and Formulations for EEJSSP

4.2. Exact and Mathematical Optimization Methods

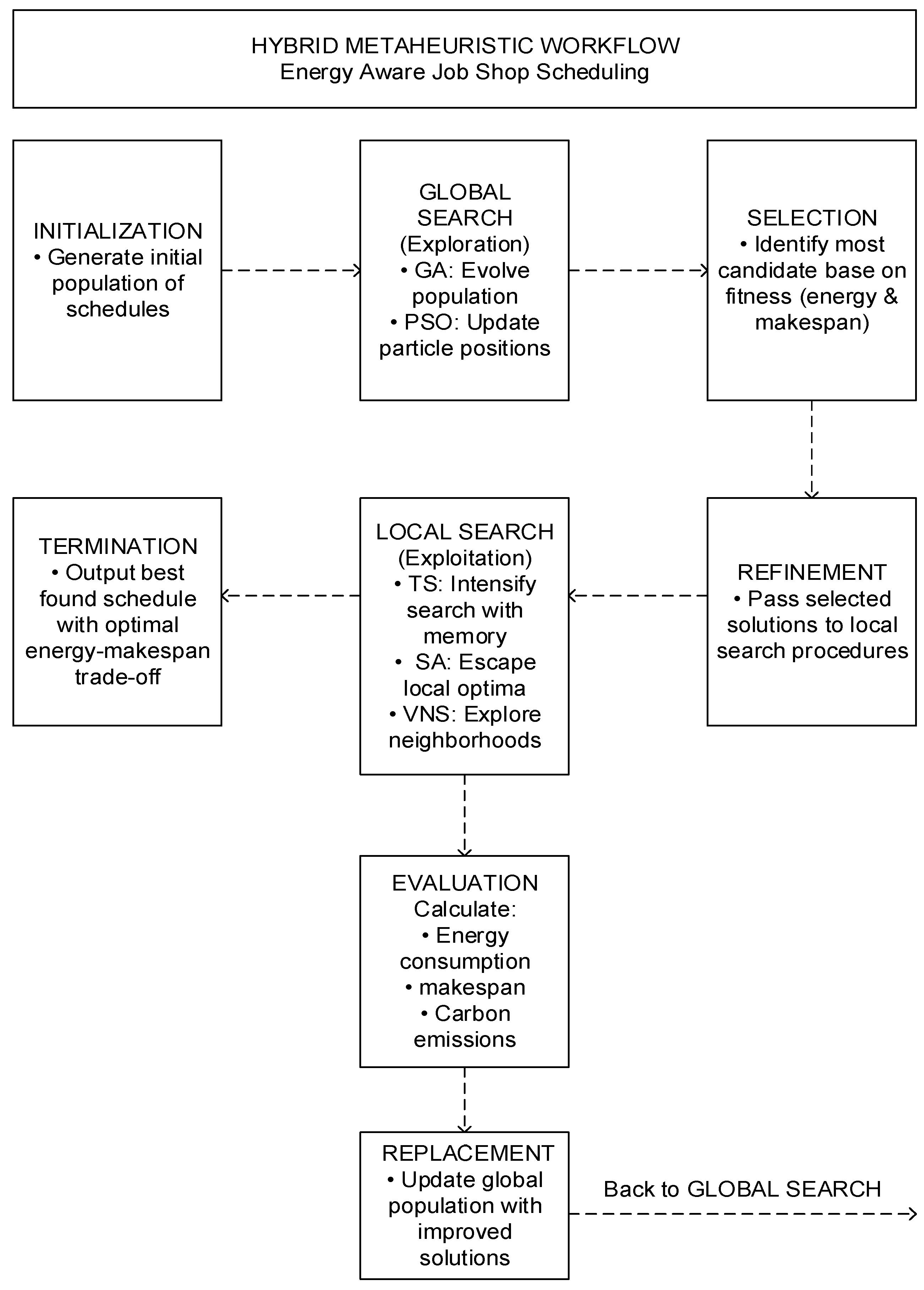

4.3. Heuristic and Metaheuristics

4.3.1. Comparative Analysis of Common Metaheuristics

4.3.2. Parameter Tuning and Algorithm Configuration

4.4. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Approaches

4.4.1. Key Techniques and Applications

4.4.2. Challenges and Pathways to Industrial Adoption

4.5. Multiobjective Approaches

4.6. Real-Time and Dynamic Scheduling

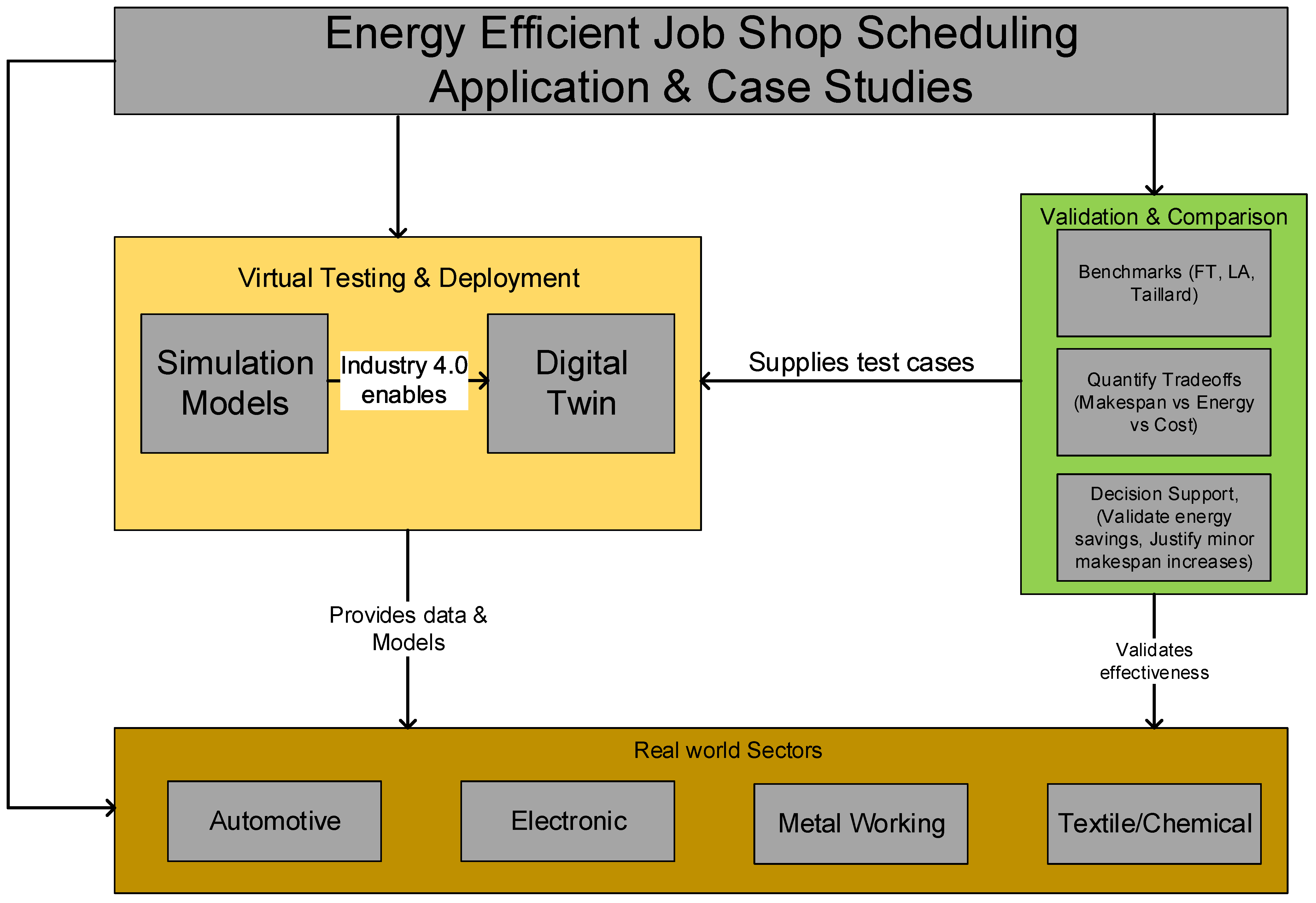

5. Application and Case Studies

5.1. Industrial Application

5.2. Simulation and Digital Twin Studies

5.3. Benchmarking Studies

6. Challenges and Research Gaps

6.1. Computational Complexity of Large Scale JSSP

- Solution quality: measured by primary objectives like makespan, total energy consumption, total cost, and carbon emissions. In multiobjective optimization, quality is assessed via Pareto front analysis using indicators such as hypervolume and spread.

- Computational efficiency: quantified by CPU/wall-clock time, convergence speed (iterations to a target solution), time-to-target quality, and scalability with problem size.

Complexity of Renewable Integration: Uncertainty and Storage

6.2. Integration of Renewable Energy and Smart Grids

6.3. Lack of Standardized Benchmarks for Energy-Aware Scheduling

- Dynamic carbon intensity: Time-varying grid carbon emission factors and on-site renewable generation profiles.

- Comprehensive energy flows: Power states of machinery (processing, idle, standby) and energy costs of essential logistics (e.g., crane movements, AGV transport).

- Circular economy indicators: Parameters related to waste reduction, tool wear, and resource reuse that extend the environmental assessment beyond direct energy use.

- Transparent verification: Independent validation of claimed carbon and energy savings from scheduling algorithms.

- Informed decision making: Equipping industry practitioners with robust, comparable data to select technologies that genuinely advance their sustainability targets.

- Targeted innovation: Focusing research efforts on solving the most material challenges in industrial decarbonization, directly aligning with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 9 (Industry, Innovation) and 12 (Responsible Consumption).

6.4. Limited Real-World Implementation Compared to Simulation

6.5. Need for Holistic Sustainability Metrics

7. Future Directions

7.1. Scalable and Hybrid Optimization Frameworks

7.2. Integration of Renewable Energy and Smart Grids

7.3. Development of Standardized Energy-Aware Benchmarks

7.4. Transition from Simulation to Real-World Implementations

7.5. Holistic Sustainability-Oriented Scheduling

7.6. Towards Autonomous and Intelligent Scheduling Systems

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| JSSP | Job-Shop Scheduling Problem |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| EEJSS | Energy-Efficient Job-Shop Scheduling |

| FJSP | Flexible Job-Shop Problem |

| SDGs | United Nations Sustainable Development Goals |

| MIP | Mixed-Integer Programming |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| DOE | Design of Experiments |

| RL | Reinforced Learning |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| NSGAII | Nondominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II |

| MOEA/D | Multiobjective Evolutionary Algorithm based on Decomposition |

| IBEA | Indicator-Based Evolutionary Algorithm |

| DT | Digital Twin |

| VRE | Variable Renewable Energy |

References

- Agency, I.E. Global Energy Review 2025; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Chen, K.; Wang, H.; Yang, B.; Leng, J. Job shop scheduling by Deep Dual-Q Network with Prioritized Experience Replay for resilient production control in flexible manufacturing system. Comput. Oper. Res. 2025, 183, 107190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, G.-Y. A literature review of reinforcement learning methods applied to job-shop scheduling problems. Comput. Oper. Res. 2025, 175, 106929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Pineda, J.L.; Canca, D.; Gonzalez-R, P.L.; Calle, M. Scheduling a dual-resource flexible job shop with makespan and due date-related criteria. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 291, 5–35. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Gao, L.; Wang, C.; Chen, H. A multitasking workforce-constrained flexible job shop scheduling problem: An application from a real-world workshop. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 83, 196–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Pan, Q.-K.; Gao, L.; Neufeld, J.S.; Gupta, J.N.D. Minimising Makespan and total tardiness for the flowshop group scheduling problem with sequence dependent setup times. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2025, 324, 436–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chung, H.; Lee, P.-H.; Shao, C. Enhancing sustainability and energy efficiency in smart factories: A review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahm, C.; Denz, F.; Dirr, M.; Tuma, A. Energy-efficient scheduling in manufacturing companies: A review and research framework. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 248, 744–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Gao, K. A genetic programming based cooperative evolutionary algorithm for flexible job shop with crane transportation and setup times. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 169, 112614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S. Optimal energy management of multi-energy multi-microgrid networks using mountain gazelle optimizer for cost and emission reduction. Energy 2025, 329, 136640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qin, C.; Xu, G.; Chen, Y.; Gao, Z. An energy-saving distributed flexible job shop scheduling with machine breakdowns. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 167, 112276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Viagas, V.; Talens, C.; Prata, B.d.A. A speed-up procedure and new heuristics for the classical job shop scheduling problem: A computational evaluation. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2025, 322, 783–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Sun, S.; Yu, S. Optimizing makespan and stability risks in job shop scheduling. Comput. Oper. Res. 2020, 122, 104963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Peng, T.; Li, X.; He, J.; Liu, W.; Tang, R. An integrated simulation–optimization method for flexible assembly job shop scheduling with lot streaming and finite transport resources. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 200, 110790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekara Reddy, M.B.S.; Ratnam, C.h.; Agrawal, R.; Varela, M.L.R.; Sharma, I.; Manupati, V.K. Investigation of reconfiguration effect on makespan with social network method for flexible job shop scheduling problem. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 110, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsmony, M.; Mor, B.; Mosheiov, G. Minimizing tardiness scheduling measures with generalized due-dates and a maintenance activity. Comput. Oper. Res. 2023, 152, 106133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; He, R.; Yuan, J. Preemptive scheduling to minimize total weighted late work and weighted number of tardy jobs. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 167, 107969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoufi, K.; Sutherland, J.W.; Zhao, F.; Clarens, A.F.; Rickli, J.L.; Fan, Z.; Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Lee, W.J.; Mathur, N.; et al. Current state and emerging trends in advanced manufacturing: Smart systems. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 134, 3031–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, X.; Yang, S. A systematic review of supply and demand side optimal load scheduling in a smart grid environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dong, H.; Lohse, N.; Petrovic, S.; Gindy, N. An investigation into minimising total energy consumption and total weighted tardiness in job shops. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Wang, J. Energy-efficient scheduling for a flexible job shop with machine breakdowns considering machine idle time arrangement and machine speed level selection. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 161, 107677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi-Aliabad, H.; Reisi-Nafchi, M.; Moslehi, G. Energy-efficient scheduling in an unrelated parallel-machine environment under time-of-use electricity tariffs. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 249, 119393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunke, F.; Nickel, S. Approximate and exact approaches to energy-aware job shop scheduling with dynamic energy tariffs and power purchase agreements. Appl. Energy 2025, 380, 125065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Wang, W.; Zhu, N.; Xu, T. An inverse reinforcement learning algorithm with population evolution mechanism for the multi-objective flexible job-shop scheduling problem under time-of-use electricity tariffs. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 170, 112764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Huang, H.; Zhao, F.; Sutherland, J.W.; Liu, Z. An Energy-Saving Method by Balancing the Load of Operations for Hydraulic Press. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2017, 22, 2673–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouakkaz, A.; Mena, A.J.G.; Haddad, S.; Ferrari, M.L. Efficient energy scheduling considering cost reduction and energy saving in hybrid energy system with energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2021, 33, 101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-j.; Wang, L. A cooperative memetic algorithm with feedback for the energy-aware distributed flow-shops with flexible assembly scheduling. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 168, 108126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xu, H.; Cheng, J.; Li, R.; Gu, Y. A decomposition-based memetic algorithm to solve the biobjective green flexible job shop scheduling problem with interval type-2 fuzzy processing time. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 183, 109513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Si, J.; Zhang, J.; Pang, Z.; Chen, H.; Ding, G. A deep reinforcement learning method based on Hindsight experience replay for multi-objective dynamic job-shop scheduling problem. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 284, 127989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglio, D.; Paolucci, M.; Roshani, A. Integrated lot sizing and energy-efficient job shop scheduling problem in manufacturing/remanufacturing systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 148, 624–641. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, J.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, J.; Zhou, Y. Genetic programming hyper-heuristic-based solution for dynamic energy-efficient scheduling of hybrid flow shop scheduling with machine breakdowns and random job arrivals. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 254, 124375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yuan, G.; Pham, D.T.; Zhang, H.; Wang, D.; Tian, G. Lot-streaming in energy-efficient three-stage remanufacturing system scheduling problem with inequal and consistent sublots. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 120, 109813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudaifah, H.; Saleh, H.; Alghazi, A.; Kolus, A.; Alturki, U.; Elferik, S. Human-aware scheduling for sustainable manufacturing: A review of dynamic job shop scheduling in the era of Industry 5.0. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2026, 98, 103143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Khalid, Q.S.; Alkahtani, M.; Khan, A.M. A Mathematical Model for Optimizing NPV and Greenhouse Gases for Construction Projects Under Carbon Emissions Constraints. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 31875–31891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, S.; Briskorn, D. A survey of variants and extensions of the resource-constrained project scheduling problem Cc: 000. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2011, 51, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Penas, D.R.; Henriques, D.; González, P.; Doallo, R.; Saez-Rodriguez, J.; Banga, J.R. A parallel metaheuristic for large mixed-integer dynamic optimization problems, with applications in computational biology. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaoui, F.Z.E.; Jabri, A.; Barkany, A.E. Optimization techniques for energy efficiency in machining processes—A review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 125, 2967–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.; Ahmed, I.; Khan, K.; Khalid, M. Emerging trends and approaches for designing net-zero low-carbon integrated energy networks: A review of current practices. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 49, 6163–6185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z. Multi-objective optimization of energy-efficient remanufacturing system scheduling problem with lot-streaming production mode. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, B.; Gao, K.; Ren, Y.; Sang, H. MILP modeling and optimization of multi-objective flexible job shop scheduling problem with controllable processing times. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2023, 82, 101374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, B.; Li, J.-Q.; Sang, H.; Zhang, C. MILP modeling and optimization of energy-efficient distributed flexible job shop scheduling problem. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 191191–191203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Zhu, H.; Liu, L.; Gong, Q. Energy-conscious flexible job shop scheduling problem considering transportation time and deterioration effect simultaneously. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2022, 35, 100680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmeister, S.C.; Guericke, D.; Schryen, G. A two-level approach for multi-objective flexible job shop scheduling and energy procurement. Clean. Energy Syst. 2025, 10, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza-Santisteban, F.; Sánchez-Pámanes, R.; Puente-Rodríguez, L.A.; Amaya, I.; Ortiz-Bayliss, J.C.; Conant-Pablos, S.; Terashima-Marín, H. A simulated annealing hyper-heuristic for job shop scheduling problems. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Wellington, New Zealand, 10–13 June 2019; pp. 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Sun, J.; Lu, X.; Zhang, H. An improved memetic algorithm for the flexible job shop scheduling problem with transportation times. Meas. Control 2020, 53, 1518–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Rey, G.M.; González-Neira, E.M.; Forero-Ortiz, G.F.; Ocampo-Monsalve, M.J.; Rivera-Torres, A. Minimizing the expected maximum lateness for a job shop subject to stochastic machine breakdowns. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 338, 801–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Dai, M.; Salido, M.A.; Giret, A. Energy-efficient dynamic scheduling for a flexible flow shop using an improved particle swarm optimization. Comput. Ind. 2016, 81, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-Q.; Li, X.-W.; Qian, B.; Jin, H.-P.; Hu, R.; Yang, J.-B. Multi-Agent Cooperative Multi-Network Group Framework for Energy-Efficient Distributed Fuzzy Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 181, 113474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chryssolouris, G.; Subramaniam, V. Dynamic scheduling of manufacturing job shops using genetic algorithms. J. Intell. Manuf. 2001, 12, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Li, J.-Q.; Luo, C.; Meng, L.-L. A hybrid estimation of distribution algorithm for distributed flexible job shop scheduling with crane transportations. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2021, 62, 100861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Tang, Q. Matheuristic and learning-oriented multi-objective artificial bee colony algorithm for energy-aware flexible assembly job shop scheduling problem. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güven, A.F.; Mengi, O.Ö.; Bajaj, M.; Azar, A.T.; El-Shafai, W. Integrated techno-economic optimization and metaheuristic benchmarking of grid-connected hybrid renewable energy systems using real-world load and climate data. e-Prime-Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2025, 13, 101099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Para, J.; Del Ser, J.; Nebro, A.J. Energy-Aware Multi-Objective Job Shop Scheduling Optimization with Metaheuristics in Manufacturing Industries: A Critical Survey, Results, and Perspectives. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yan, S.; Song, X.; Zhang, D.; Guo, S. Evolutionary algorithm incorporating reinforcement learning for energy-conscious flexible job-shop scheduling problem with transportation and setup times. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 107974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Rui, Z.; Zhang, X.; Ge, M.; Ling, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, C. EFJSP-IBDR: Energy-efficient flexible job shop scheduling under incentive-based demand response via graph reinforcement learning with dual attention mechanism. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 280, 127340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, M.; Ling, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Sun, M. Graph reinforcement learning for flexible job shop scheduling under industrial demand response: A production and energy nexus perspective. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 193, 110325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Cui, M.; Tian, M.; He, Y. Surrogate model-based energy-efficient scheduling for LPWA-based environmental monitoring systems. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 59940–59948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.-J.; Ham, A. Energy-aware flexible job shop scheduling under time-of-use pricing. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 248, 108507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samek, W.; Montavon, G.; Lapuschkin, S.; Anders, C.J.; Müller, K.-R. Explaining deep neural networks and beyond: A review of methods and applications. Proc. IEEE 2021, 109, 247–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Shen, W.; Fan, J.; Vogel-Heuser, B.; Zhang, C. An improved non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II for distributed heterogeneous hybrid flow-shop scheduling with blocking constraints. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 77, 990–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-B.; Lou, Y.-J.; Yang, J.-R.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, C.-L. Balancing economic growth and carbon peaking in China: An integrated LSTM-NSGA-III framework for sustainable energy transitions. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 27, 100784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Gong, W.; Li, R.; Lu, C. Problem-specific knowledge MOEA/D for energy-efficient scheduling of distributed permutation flow shop in heterogeneous factories. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 123, 106454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Yang, L.; Li, K.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, J.; Wang, D. An enhanced diversity indicator-based many-objective evolutionary algorithm with shape-conforming convergence metric. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 166, 112161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Yang, D.; Zhou, B.; Yang, Z.; Liu, T.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Hu, K. Adaptive Population NSGA-III with Dual Control Strategy for Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem with the Consideration of Energy Consumption and Weight. Machines 2021, 9, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Zhang, L.; Fan, Y. Energy-efficient scheduling for multi-objective flexible job shops with variable processing speeds by grey wolf optimization. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 234, 1365–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yang, K.; Wang, Y.; Su, L.; Hu, H. Long-term multi-objective power generation operation for cascade reservoirs and risk decision making under stochastic uncertainties. Renew. Energy 2021, 164, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiue, Y.-R.; Lee, K.-C.; Su, C.-T. Real-time scheduling for a smart factory using a reinforcement learning approach. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2018, 125, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Fang, X.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, S.; Li, Q. Joint multi-objective dynamic scheduling of machine tools and vehicles in a workshop based on digital twin. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 70, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Gu, F.; Li, L.; Guo, J. A framework of cloud-edge collaborated digital twin for flexible job shop scheduling with conflict-free routing. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2024, 86, 102672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y. Game theory based real-time multi-objective flexible job shop scheduling considering environmental impact. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 665–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Chiong, R. Solving the energy-efficient job shop scheduling problem: A multi-objective genetic algorithm with enhanced local search for minimizing the total weighted tardiness and total energy consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 3361–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Ren, S.; Wang, C.; Ma, S. Edge computing-based real-time scheduling for digital twin flexible job shop with variable time window. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2023, 79, 102435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Zhang, C.; Shao, X.; Ren, Y. MILP models for energy-aware flexible job shop scheduling problem. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 710–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Duan, P.; Gao, K.; Zhang, B.; Zou, W.; Han, Y.; Zhang, C. MIP modeling of energy-conscious FJSP and its extended problems: From simplicity to complexity. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 241, 122594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darghouth, M.; Attia, A. Sustainable scheduling for job shops with joint maintenance, machine speed scaling, and uncertain processing times. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2026, 97, 103091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Ye, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Pei, F.; Gu, W. Multi-objective energy-efficient scheduling of distributed heterogeneous hybrid flow shops via multi-agent double deep Q-Network. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 98, 102076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Ma, R.; Du, J.; Han, H. Decomposition-based multi-objective reinforcement learning for dynamic disassembly job shop scheduling with urgency guidance. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 97, 102040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Zhang, C.; Meng, L.; Zhang, B.; Gao, K.; Sang, H. Deep reinforcement learning for solving efficient and energy-saving flexible job shop scheduling problem with multi-AGV. Comput. Oper. Res. 2025, 181, 107087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; El Baz, D.; Xue, R.; Hu, J. Solving the dynamic energy aware job shop scheduling problem with the heterogeneous parallel genetic algorithm. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 108, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, L.; Tang, H.; Sun, L.; Guo, S. A hybrid imperialist competitive algorithm for energy-efficient flexible job shop scheduling problem with variable-size sublots. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 172, 108641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, J. An enhanced memetic algorithm for energy-efficient and low-carbon flexible job shop scheduling problem considering machine restart. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 80, 457–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, A.; Jeon, H.W.; Lee, S.; Wang, C. Minimizing total energy cost and tardiness penalty for a scheduling-layout problem in a flexible job shop system: A comparison of four metaheuristic algorithms. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 141, 106295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Shao, L.; Yao, B.; Zhou, Z.; Pham, D.T. Perception data-driven optimization of manufacturing equipment service scheduling in sustainable manufacturing. J. Manuf. Syst. 2016, 41, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Jiang, X.; Liu, W.; Li, Z. Dynamic energy-efficient scheduling of multi-variety and small batch flexible job-shop: A case study for the aerospace industry. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 178, 109111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, H. A teaching-learning-based optimization with feedback for LR fuzzy flexible assembly job shop scheduling problem with batch splitting. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 224, 120043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y. A hybrid multi-objective evolutionary algorithm to integrate optimization of the production scheduling and imperfect cutting tool maintenance considering total energy consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 121540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Qian, L.; Zhang, K.; Li, D.; Zhao, S.; Li, J. A self-learning classification-based multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for machine multi-state energy-efficient flexible job shop scheduling under time-of-use pricing. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 99, 102142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Jia, Y.; Liu, C.; Xu, G.; Li, K. A self-learning multi-population evolutionary algorithm for flexible job shop scheduling under time-of-use pricing. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 189, 110004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondran, M.; Kemmoe, S.; Lamy, D.; Tchernev, N. Bi-objective optimisation approaches to Job-shop problem with power requirements. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 162, 113753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; De Pessemier, T.; Martens, L.; Joseph, W. Energy-and labor-aware flexible job shop scheduling under dynamic electricity pricing: A many-objective optimization investigation. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 1078–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Chiong, R.; Li, W. Energy-efficient open-shop scheduling with multiple automated guided vehicles and deteriorating jobs. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2022, 30, 100387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Jin, M.; Du, N. Energy-efficient scheduling of a single batch processing machine with dynamic job arrival times. Energy 2020, 209, 118420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; Gao, L.; Xia, K. Knowledge-based multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for energy-efficient flexible job shop scheduling with mobile robot transportation. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 62, 102647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Lei, Q.; Song, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y. Knowledge-enhanced multi-objective memetic algorithm for energy-efficient flexible job shop scheduling with limited multi-load automated guided vehicles. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 159, 111771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, W.; Ab Rashid, M.F.F.; Mu’tasim, M.A.N. Greedy-assisted teaching-learning-based optimization algorithm for cost-based hybrid flow shop scheduling. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 273, 126955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Lu, C.; Zhou, J.; Yin, L.; Wang, K. A knowledge-guided bi-population evolutionary algorithm for energy-efficient scheduling of distributed flexible job shop problem. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 128, 107458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Yin, F.; Zhang, J.; Xu, T.P. A learning-based co-evolution optimization framework for energy-aware distributed heterogeneous flexible flow shop lot-streaming scheduling problem. Expert Syst. Appl. 2026, 296, 128986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Li, L.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, Q. A multi-level optimization approach for energy-efficient flexible flow shop scheduling. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, M.; Chiong, R.; Noman, N.; Zhang, R. A multi-population, multi-objective memetic algorithm for energy-efficient job-shop scheduling with deteriorating machines. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 157, 113348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, C.; March, C.; Salido, M.A. Driving Energy Efficiency in Scheduling Manufacturing: An Advanced Instance Generation and a Metaheuristic Approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 288, 128138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Gao, L.; Li, X.; Li, P.; Tasgetiren, M.F. Energy-efficient distributed permutation flow shop scheduling problem using a multi-objective whale swarm algorithm. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2020, 57, 100716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Liao, W.; Zhang, L. Hybrid energy-efficient scheduling measures for flexible job-shop problem with variable machining speeds. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 197, 116785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Cao, Z. An improved multi-objective evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition for solving re-entrant hybrid flow shop scheduling problem with batch processing machines. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 169, 108236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Qin, H. A single-individual based variable neighborhood search algorithm for the blocking hybrid flow shop group scheduling problem. Egypt. Inform. J. 2024, 27, 100509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, M.; Mohamadi, P.H.A.; Aernouts, M.; Singh, R.K.; Vanderborght, B.; Weyn, M.; Famaey, J. Energy-aware multi-robot task scheduling using meta-heuristic optimization methods for ambiently-powered robot swarms. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2025, 186, 104898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Tian, Z.; Liu, W.; Suo, Y.; Chen, K.; Xu, X.; Li, Z. Energy-efficient scheduling of flexible job shops with complex processes: A case study for the aerospace industry complex components in China. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2022, 27, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Guo, S.; Wang, L. Integrated green scheduling optimization of flexible job shop and crane transportation considering comprehensive energy consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 765–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Gong, W.; Lu, C. Self-adaptive multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for flexible job shop scheduling with fuzzy processing time. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 168, 108099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Zou, Z.; Liang, X. Solving multi-objective energy-saving flexible job shop scheduling problem by hybrid search genetic algorithm. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 200, 110829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Tian, G.; Fathollahi-Fard, A.M.; Ahmadi, A.; Zhang, C. Stochastic multi-objective modelling and optimization of an energy-conscious distributed permutation flow shop scheduling problem with the total tardiness constraint. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathollahi-Fard, A.M.; Woodward, L.; Akhrif, O. Sustainable distributed permutation flow-shop scheduling model based on a triple bottom line concept. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2021, 24, 100233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, X.; Gao, L.; Li, P. Energy-efficient distributed heterogeneous welding flow shop scheduling problem using a modified MOEA/D. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2021, 62, 100858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, A.; Liu, X.; Gong, G.; Yuan, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J. Multi-objective optimization for distributed flexible job shop scheduling problem with job priority. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 98, 102075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, H.; Han, Y.; Wang, Y. An improved multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for the low-carbon flexible job shop scheduling with automated guided vehicles. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 175, 113048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Lu, B. Energy-aware operations management for flow shops under TOU electricity tariff. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 151, 106942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-Q.; Wu, F.-C.; Qian, B.; Hu, R.; Wang, L.; Jin, H.-P. A Q-learning-based hyper-heuristic evolutionary algorithm for the distributed flexible job-shop scheduling problem with crane transportation. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 234, 121050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, H.; Hasani, A. An energy-efficient multi-objective optimization for flexible job-shop scheduling problem. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2017, 104, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Li, X.; Gao, L.; Lu, C.; Zhang, Z. A novel mathematical model and multi-objective method for the low-carbon flexible job shop scheduling problem. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2017, 13, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, K.; Bhutta, M.U.; Butt, S.I.; Jaffery, S.H.I.; Khan, M.; Khan, A.Z.; Faraz, Z. A Pareto-optimality based black widow spider algorithm for energy efficient flexible job shop scheduling problem considering new job insertion. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 164, 111937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.A.; Rasconi, R.; Oddi, A. Metaheuristics for multiobjective optimization in energy-efficient job shops. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 115, 105263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-Q.; Deng, J.-W.; Li, C.-Y.; Han, Y.-Y.; Tian, J.; Zhang, B.; Wang, C.-G. An improved Jaya algorithm for solving the flexible job shop scheduling problem with transportation and setup times. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2020, 200, 106032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, S.; Schönheit, M.; Neufeld, J.S. Multi-objective carbon-efficient scheduling in distributed permutation flow shops under consideration of transportation efforts. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Che, A. An enhanced decomposition-based multi-objective evolutionary algorithm with neighborhood search for multi-resource constrained job shop scheduling problem. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 93, 101834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Peng, S.; Su, H. An improved MOEA/D for multi-objective flexible job shop scheduling by considering efficiency and cost. Comput. Oper. Res. 2024, 167, 106674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Liao, X.; Chen, G.; Chen, Y. Co-Evolutionary NSGA-III with deep reinforcement learning for multi-objective distributed flexible job shop scheduling. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 203, 110990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Guan, Z.; Luo, D.; Yue, L. Data-driven hierarchical multi-policy deep reinforcement learning framework for multi-objective multiplicity dynamic flexible job shop scheduling. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 80, 536–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, R.; Gong, W. Deep reinforcement learning-based memetic algorithm for energy-aware flexible job shop scheduling with multi-AGV. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 189, 109917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhou, H. Learning-driven memetic algorithm for solving integrated distributed production and transportation scheduling problem. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 96, 101945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, K.; Gan, S.; Cameron, C. Analysis of energy saving potentials in intelligent manufacturing: A case study of bakery plants. Energy 2019, 172, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, D. DQL-assisted competitive evolutionary algorithm for energy-aware robust flexible job shop scheduling under unexpected disruptions. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2024, 91, 101750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Xu, G.; Zhang, Y. Distributed assembly flexible job shop scheduling with dual-resource constraints via a deep Q-network based memetic algorithm. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 98, 102086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Fujimura, S.; El Baz, D.; Plazolles, B. GPU based parallel genetic algorithm for solving an energy efficient dynamic flexible flow shop scheduling problem. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2019, 133, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tang, Q.; Wu, Z.; Wang, F. Mathematical modeling and evolutionary generation of rule sets for energy-efficient flexible job shops. Energy 2017, 138, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z. Multi-objective Q-learning-based hyper-heuristic with Bi-criteria selection for energy-aware mixed shop scheduling. Swarm. Evol. Comput. 2021, 69, 100985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Gong, G.; Peng, N.; Zhu, K.; Huang, D.; Luo, Q. An effective memetic algorithm for distributed flexible job shop scheduling problem considering integrated sequencing flexibility. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 242, 122734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Ahmad, R. An energy-efficient multi-objective scheduling for flexible job-shop-type remanufacturing system. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 66, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghelinejad, M.M.; Masmoudi, O.; Ouazene, Y.; Yalaoui, A. Multi-state two-machine permutation flow shop scheduling optimisation with time-dependent energy costs. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 11156–11161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Fang, S.; Dong, H. Multi-fidelity digital twin based optimization for aircraft overhaul shop scheduling. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 82, 700–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Shen, Y.; Liu, W.; Lü, M. Digital twin-based optimization of AGV scheduling under energy constraints in plant factories. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 519, 146016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, H.; Tan, J.; Li, Z.; Hou, W.; Guo, Y. Capacity configuration optimization of multi-energy system integrating wind turbine/photovoltaic/hydrogen/battery. Energy 2022, 252, 124046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Lu, Y.; Wu, N.; Zhu, Q.; Yao, L.; Zhang, T. A renewable energy aware multi-agent reinforcement learning approach for the dynamic flexible job shop scheduling problem. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2026, 70, 104113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liang, J.; Xue, Y.; Tan, S. Optimization of agricultural biomass Supply: Dual reduction of cost and carbon emissions based on multi-objective arithmetic optimization algorithm. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 511, 145670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez Flores, I.A.; Mendoza Paz, S.; Villazón Gómez, M.F.; Willems, P.; Gobin, A. Impacts of climate change on the hydropower potential of a multipurpose storage system project in Bolivian Andes. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 62, 102903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiron, J.; Göransson, L.; Normann, F.; Johnsson, F. Flexibility provision by combined heat and power plants—An evaluation of benefits from a plant and system perspective. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 16, 100318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tan, C.; Chen, P.; Lu, M.; Feng, G.; Gao, X.; Liu, B.; Jing, L. Optimization of staggered peak intermittent pumping operation scheduling of pumping unit well clusters under wind, solar and energy storage microgrid with improved adaptive GAPSO hybrid algorithm. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 252, 213897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Simulated Annealing (SA) | Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | Tabu Search (TS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core inspiration | Biological evolution (natural selection). | Thermodynamics (annealing of metals). | Social behavior (flock of birds, school of fish). | Memory and learning. |

| Solution representation | Typically, a “chromosome” (bit string, integer list, etc.). | A single state (any data structure). | A swarm of “particles” with position & velocity. | A single current solution (any data structure). |

| Search strategy | Population-based, explores multiple areas in parallel. | Single solution, stochastic hill climbing with a “temperature”. | Population-based, particles fly through the space influenced by personal and social best. | Single solution, guided local search using memory to avoid cycles. |

| Key operators/mechanisms | Selection, crossover, mutation. | Neighbor generation, acceptance probability (Boltzmann criterion). | Velocity update (inertia, cognitive, social components). | Neighborhood search, Tabu list (short-term memory). |

| Strengths | Good for complex, multimodal problems. Explores diverse areas of the search space. | Simple to implement. Very effective at escaping local optima, especially in early stages. | Fast convergence on many problems. Simple concept, few parameters to tune. | Excellent intensification. Systematically explores promising regions without repeating moves. |

| Weaknesses | Can be computationally heavy. Sensitive to parameter tuning (crossover/mutation rates). | Convergence can be slow. Cooling schedule is critical and problem-dependent. | Can converge prematurely to a local optimum if not careful. | Defining an effective neighborhood and Tabu list can be problem specific. |

| Best suited for | Discrete and combinatorial problems (e.g., scheduling, routing). | Problems where a good enough solution is needed quickly, or as a component of a hybrid algorithm. | Continuous optimization problems, but also applied to discrete spaces. | Combinatorial problems like vehicle routing, graph coloring, and scheduling. |

| Category | Study |

|---|---|

| Exact methods | [30,74,75,76] |

| Artificial intelligence and machine learning | [29,55,56,77,78,79] |

| Real time | [47,69,71,80] |

| Heuristic and metaheuristic | [20,27,28,50,61,66,72,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114] |

| Hybrid | [43,48,51,54,70,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137] |

| Energy Aspect | Study |

|---|---|

| On/off (machine state control) | [27,28,29,50,74,77,81,82,83,84,85,86,120,121,122,134] |

| Energy cost (pricing, tariffs) | [30,55,56,70,79,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,115,116,117,118,128,129,130,133,138] |

| Machine speed (variable energy consumption) | [20,43,47,48,51,54,61,69,71,75,76,78,107,113,114,123,124,125,126,127,131,132,136,137] |

| Other considerations (e.g., temperature, renewables) | [66,72,80,102,103,119,135] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Makhoabenyane, M.; Guo, S.; Leburu, E. Towards Sustainable Factories: A Systematic Review of Energy-Conscious Job-Shop Scheduling Models and Algorithms. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11330. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411330

Makhoabenyane M, Guo S, Leburu E. Towards Sustainable Factories: A Systematic Review of Energy-Conscious Job-Shop Scheduling Models and Algorithms. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11330. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411330

Chicago/Turabian StyleMakhoabenyane, Motlokoa, Shunsheng Guo, and Ely Leburu. 2025. "Towards Sustainable Factories: A Systematic Review of Energy-Conscious Job-Shop Scheduling Models and Algorithms" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11330. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411330

APA StyleMakhoabenyane, M., Guo, S., & Leburu, E. (2025). Towards Sustainable Factories: A Systematic Review of Energy-Conscious Job-Shop Scheduling Models and Algorithms. Sustainability, 17(24), 11330. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411330