Abstract

The United Kingdom’s (UK) retrofit revolution is at a crossroads and the efficacy of retrofit interventions is not solely a function of insulation thickness. To truly slash emissions and lift households out of fuel poverty, we must solve the persistent problem of thermal bridging (TB), i.e., the hidden flaws that cause heat to escape, dampness to form, and well-intentioned retrofits to fail. This review moves beyond basic principles to spotlight the emerging tools and transformative strategies to make a difference. We explore the role of advanced modelling techniques, including finite element analysis (FEA), in pinpointing thermal and moisture-related risks, and how emerging materials like vacuum-insulated panels (VIPs) offer high-performance solutions in tight spaces. Crucially, we demonstrate how an integrated fabric-first approach, guided by standards like PAS 2035, is essential to manage moisture, ensure durability, and deliver the comfortable, low-energy homes the UK desperately needs. Therefore, achieving net-zero targets is critically dependent on the systematic upgrade of the building envelope, with the mitigation of TB representing a fundamental prerequisite. The EnerPHit approach applies a rigorous fabric-first methodology to eliminate TB and significantly reduce the building’s overall heat demand. This reduction enables the use of a compact heating system that can be efficiently powered by renewable energy sources, such as solar photovoltaic (PV). Moreover, this review employs a systematic literature synthesis to critically evaluate the integration of TB mitigation within the PAS 2035 framework, identifying key technical interdependencies and research gaps in whole-house retrofit methodology. This article provides a comprehensive review of established FEA modelling methodologies, rather than presenting results from original simulations.

1. Introduction

Domestic retrofit in the UK has emerged as a cornerstone of national strategies to reduce carbon emissions, improve energy efficiency, and enhance the comfort and resilience of existing dwellings [1]. Retrofit, broadly defined, refers to the upgrading of the building fabric, services, and overall energy performance of existing homes [2]. The urgency of retrofit has been underscored by the UK government’s commitment to achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, as articulated in the Climate Change Act 2008 and reinforced by subsequent policy initiatives. Residential buildings contribute approximately 20–25% of the UK’s total carbon emissions, predominantly from space heating, making the domestic sector a critical focus for emission reduction strategies [3,4]. The political landscape surrounding retrofit has evolved rapidly over the past decade. Government-led initiatives such as the Green Homes Grant, the Energy Company Obligation (ECO), and various funding mechanisms for energy efficiency improvements have aimed to stimulate investment and accelerate the uptake of domestic retrofit. These programs emphasise financial support, guidance, and quality assurance, highlighting the importance of coordinated interventions. Beyond national policies, local authorities and housing associations play a significant role in implementing retrofit schemes, particularly in areas with high concentrations of older or poorly performing housing stock. This multi-level governance structure creates both opportunities and challenges for standardisation, monitoring, and quality control [5]. A critical driver of domestic retrofit is the regulatory framework that governs energy performance in dwellings. The Building Regulations Approved Document L1 (ADL1) establishes minimum standards for the conservation of fuel and power in new and existing homes. ADL1 sets benchmarks for fabric insulation, air tightness, and heating efficiency, ensuring that any retrofit intervention meets a baseline performance [6,7,8]. However, in many cases, achieving optimal energy efficiency and occupant comfort requires exceeding these minimum standards. As a result, alternative retrofit standards, including EnerPHit, Passivhaus Retrofit, and BREEAM Domestic Retrofit, have emerged, offering more ambitious targets and holistic approaches to energy performance. These standards emphasise whole-house thinking, integrated design, and careful consideration of moisture, TB, and indoor air quality. Therefore, the aim of this review article is to evaluate current research, standards, and case study data to construct a systems model of domestic retrofit, with a specific focus on the critical yet often underestimated role of TB.

From a technical perspective, the UK housing stock presents a diverse and challenging landscape for retrofit practitioners. Homes range from Victorian terraces and Edwardian villas to post-war semi-detached houses, flats, and modern low-energy dwellings. Older properties often feature solid walls, uninsulated floors, and single-glazed windows, making them inherently less energy-efficient and more susceptible to heat loss, condensation, and moisture-related damage. In contrast, newer dwellings may incorporate cavity walls, loft insulation, and double-glazing, yet can still benefit from upgrades to achieve ultra-low energy performance or compliance with ambitious retrofit standards. This diversity necessitates a flexible, site-specific approach to retrofit that considers building typology, construction materials, occupant behaviour, and local climatic conditions. Domestic energy use patterns further highlight the importance of targeted retrofit interventions. On average, space heating accounts for 60–70% of energy consumption, followed by hot water (15–20%), with the remainder attributed to lighting, appliances, and cooking [9]. These patterns vary significantly depending on dwelling type, occupancy, and lifestyle factors. Older homes with poor insulation tend to exhibit high heating demand, whereas modern homes may have lower heating loads but higher electricity consumption due to increased use of electrical appliances. Understanding these patterns is essential for prioritising retrofit measures and estimating the potential energy and carbon savings achievable from interventions such as wall insulation, loft insulation, window replacement, and heating system upgrades [10,11,12]. A core principle underpinning effective domestic retrofit is the whole-house approach. Rather than focusing on individual measures in isolation, whole-house retrofit considers the dwelling as an integrated system in which fabric, services, ventilation, and renewable energy systems interact. This approach minimises the risk of unintended consequences, such as condensation or TB, and ensures that energy efficiency improvements are durable and effective. Closely linked is the fabric-first philosophy, which prioritises improvements to the building envelope, e.g., walls, roofs, floors, windows, and doors, before investing in mechanical systems. By addressing heat loss and air infiltration at the source, the fabric-first approach enhances comfort, reduces energy demand, and provides a solid foundation for additional interventions, including renewable energy systems [13,14,15]. TB is a critical consideration within both whole-house and fabric-first strategies. Thermal bridges occur where the building fabric allows heat to bypass insulation, typically at junctions, penetrations, and construction discontinuities. These areas can result in localised heat loss, cold spots, and increased risk of condensation and mould growth. Mitigating thermal bridges requires careful detailing, continuous insulation, and high-quality installation practices. The importance of TB in retrofit cannot be overstated, as failure to address it can significantly undermine the energy and comfort benefits of other measures [16,17,18]. Another central element of retrofit is moisture management. Retrofitting a dwelling without considering moisture dynamics can lead to serious issues such as mould growth, structural decay, and reduced indoor air quality. Standards such as PAS 2035 provide guidance on integrating moisture risk assessments into the retrofit design process, emphasising the need for coordinated planning, installation, and post-occupancy evaluation.

PAS 2035 outlines requirements for intermediate and post-retrofit monitoring, including air-tightness testing, temperature and humidity logging, fuel consumption analysis, and occupant feedback [19]. These processes provide data to assess the effectiveness of measures, identify underperformance, and guide maintenance and further improvements. By combining monitoring with robust risk management and coordination, domestic retrofit can deliver reliable energy savings, improved comfort, and reduced carbon emissions over the long term [20]. PAS 2035 mandates structured assessment, design, and evaluation processes, requiring certified Retrofit Coordinators to oversee compliance and ensure quality outcomes. Achieving effective retrofit requires a whole-house, fabric-first approach, attention to TB and moisture risks, integration of renewable energy systems, and comprehensive monitoring and evaluation. The Retrofit Coordinator plays a central role in ensuring these elements are successfully combined, delivering interventions that enhance energy efficiency, occupant comfort, and the long-term performance of diverse housing stock [21,22,23]. The Retrofit Coordinator role is particularly vital for managing interactions between measures, identifying site-specific challenges, and ensuring that energy and carbon savings are realised in practice. By coordinating multi-disciplinary teams, including Retrofit Designers, installers, and energy assessors, the Retrofit Coordinator ensures that interventions are holistic, safe, and effective. In addition to fabric and moisture considerations, modern retrofit projects increasingly integrate renewable energy systems. Technologies, e.g., PV panels, solar thermal systems, micro-combined heat and power (micro-CHP), and small-scale wind turbines offer opportunities to further reduce carbon emissions and energy costs [24,25]. However, the selection and integration of renewable systems require careful planning to ensure compatibility with existing building fabric, orientation, and energy demand profiles. Financial incentives, e.g., renewable heat incentive and feed-in tariffs, support the adoption of renewables and improve the economic viability of retrofit projects. Effective monitoring and evaluation under PAS 2035 provide significant benefits that extend beyond compliance, ensuring that retrofit interventions deliver their intended outcomes. First, assured performance is achieved by systematically verifying that energy efficiency measures, air-tightness improvements, and renewable integrations function as designed, reducing the likelihood of performance gaps. Second, risk mitigation is enhanced through early detection of issues (TB, condensation, or system malfunctions), allowing corrective action before occupant comfort or building integrity is compromised. Third, data-driven decision-making is facilitated by continuous collection of quantitative and qualitative data from smart meters, sensors, and occupant feedback enabling evidence-based adjustments to optimise energy use and inform future retrofit strategies.

This review was conducted as a structured narrative review to provide a comprehensive, systems-oriented analysis of TB within the context of UK net-zero housing retrofit, with a particular focus on the PAS 2035 framework. While not adhering to the full protocol of a systematic review, a rigorous and documented process was employed to identify, select, and synthesise the relevant literature, ensuring a representative and critical overview of the field. The literature search was performed primarily using the scholarly databases Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar to ensure broad coverage of journal articles, conference proceedings, and relevant grey literature. The search strategy combined keywords and Boolean operators related to the core themes of the review. Searches were initially conducted in yearly basis to capture the most recent publications up to the point of manuscript submission. Studies were screened for relevance based on the peer-reviewed journal articles, authoritative books, and key conference papers. The initial database searches yielded a large volume of results. Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, and the full texts of potentially relevant papers were obtained. The final selection of 123 references was synthesised to construct a coherent narrative. The synthesis was guided by a systems-thinking approach, aiming to elucidate the interconnections between policy, building physics, materials science, and on-site practice. The structure of the review emerged from this process, organised to first establish the context (UK housing, regulations) before delving into technical principles (whole-house, fabric-first), key risks (TB, moisture), and specific solutions (materials, services integration).

2. Domestic Energy Use Patterns

The UK’s domestic housing stock is remarkably diverse, reflecting centuries of architectural evolution, varying construction techniques, and regional differences in climate and socio-economic conditions. This diversity presents both opportunities and challenges for domestic retrofit, as energy efficiency interventions must be tailored to the characteristics of each dwelling type to achieve optimal performance. Understanding the typology, construction materials, and occupancy patterns of UK homes is essential for effective retrofit planning. The UK housing stock, comprising over 27 million dwellings across private, social, and rental sectors, exhibits significant diversity in age, construction, and energy performance [26]. Pre-1919 Victorian and Edwardian homes, built with solid masonry walls, high ceilings, and single-glazed windows, are among the least energy-efficient due to poor insulation and outdated heating systems. Interwar houses (1919–1945) introduced cavity walls and semi-detached layouts, yet many remained uninsulated with minimal loft insulation, leading to continued heat loss. The post-war era (1945–1975) brought rapid, large-scale construction using materials such as prefabricated concrete and steel, often resulting in TB and poor airtightness. By contrast, post-1975 homes benefited from improved building regulations mandating insulation, double glazing, and efficient heating systems, including gas combi boilers and heat pumps [27,28,29,30,31,32]. Specialist dwellings, e.g., flats, terraces, and high-rises, pose unique retrofit challenges due to shared structures and ventilation complexities. Regional differences further influence retrofit needs, with northern areas typically facing higher heating demands due to older housing and colder climates, while southern areas exhibit more modern, electrically dependent homes with distinct energy use profiles. Solid walls are inherently less thermally efficient than cavity walls, requiring internal or external insulation to reduce heat loss. Roofs range from pitched tiled designs to flat concrete constructions. Loft insulation is highly variable, particularly in older homes. Suspended timber floors are common in Victorian homes, which are prone to heat loss and moisture problems. Solid floors are easier to insulate during major retrofits. Single-glazing is prevalent in older stock, whereas modern homes generally feature double or triple glazing. Poor window positioning can exacerbate overheating or heat loss. Older homes often rely on inefficient gas or electric heating, while modern homes integrate high-efficiency boilers, heat pumps, or hybrid systems. The interaction between these factors defines the baseline energy performance of each dwelling and informs the selection of appropriate retrofit measures, including insulation, air tightness, ventilation, and heating system upgrades [33].

Domestic energy consumption in the UK is largely driven by space heating, which accounts for around 60–70% of total household energy use, especially in older, poorly insulated dwellings. Hot water heating contributes roughly 15–20%, while lighting, appliances, and cooking make up the remaining 10–15%. These figures, however, vary considerably depending on dwelling type, occupancy patterns, and user behaviour. Older homes tend to have higher heating demand due to poor insulation, TB, and outdated heating systems. Features such as single-glazed windows and uninsulated walls, floors, and roofs cause significant conductive heat loss, leading to high fuel costs and issues like condensation and dampness. In contrast, modern homes are more energy-efficient, with improved insulation, airtightness, and double or triple glazing reducing heat losses. Although their heating demand is lower, energy consumption in newer dwellings is shifting towards electricity due to the widespread use of electronic devices and appliances. The adoption of renewable technologies such as solar panels and heat pumps further supports decarbonisation. Additionally, occupant behaviour plays a crucial role in shaping energy demand, factors like household size, heating habits, and lifestyle choices influence consumption patterns. Emerging trends such as remote working and electric vehicle use are also changing energy profiles, increasing daytime electricity use and driving demand for smarter energy management solutions [34,35].

Heat Loss and Gain Mechanisms

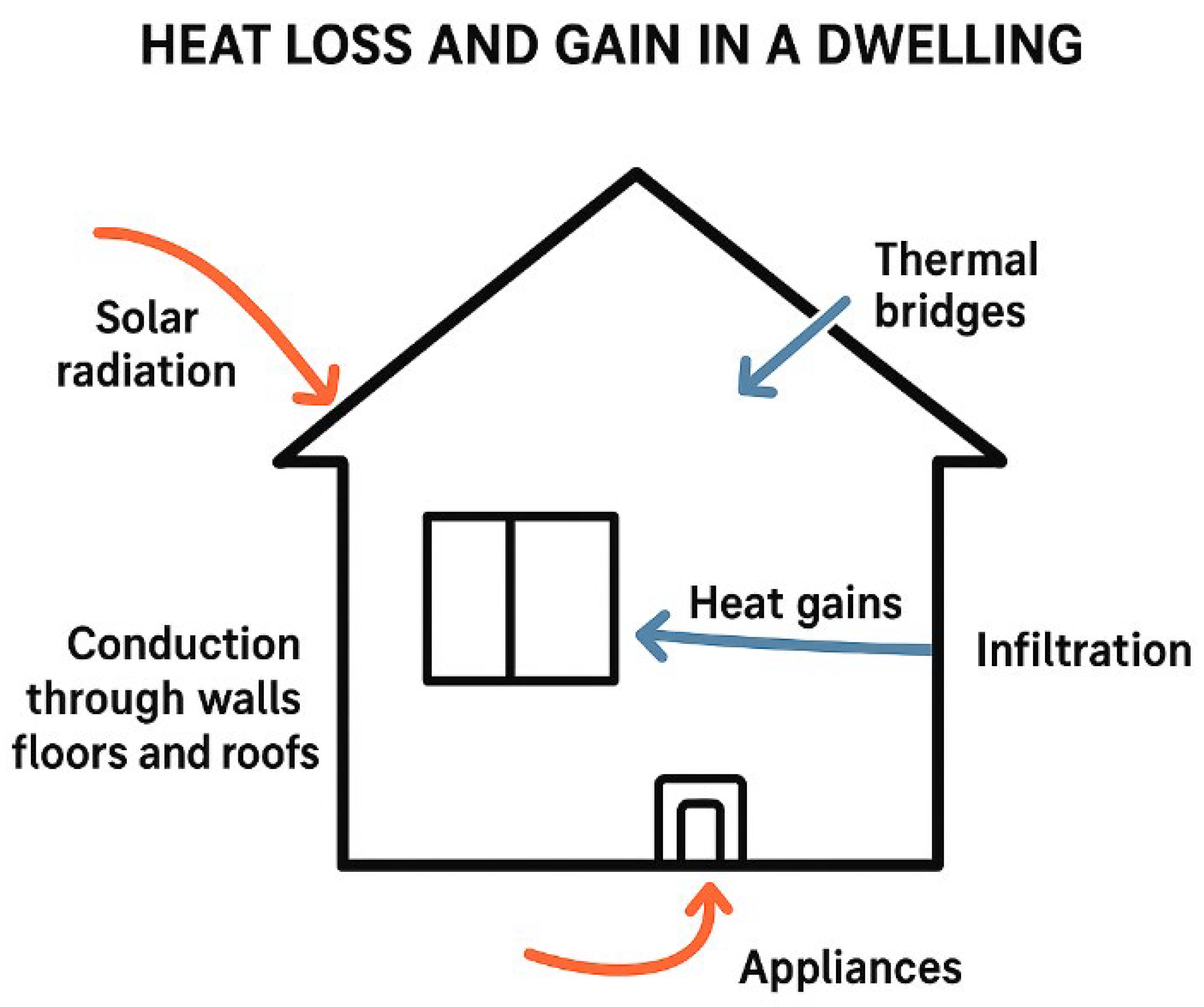

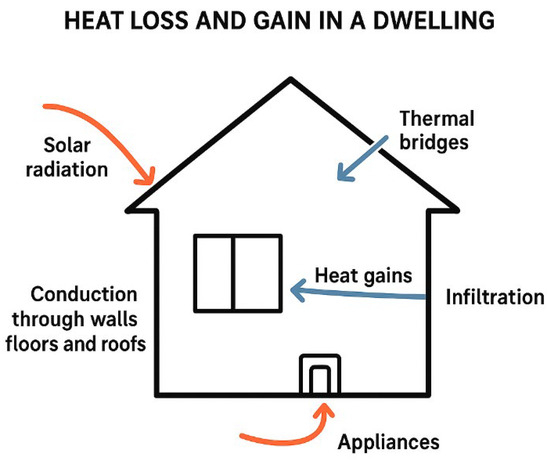

Energy use in dwellings is governed by the balance between heat loss and gain, including conduction through walls, floors, and roofs, TB at junctions, penetrations, and poorly insulated details, and infiltration through gaps in doors, windows, and service penetrations. Heat gains occur from solar radiation through windows and internal sources such as appliances, lighting, and occupants. Understanding these mechanisms is critical to predicting energy consumption and optimising retrofit interventions. Thermal modelling tools help quantify heat flows and identify the most effective combination of measures [36]. Table 1 shows the typical distribution of domestic energy use in UK households. Data are based on averages from national housing stock analysis [37].

Table 1.

Typical Domestic Energy Use Patterns [37].

The diversity of housing stock and energy use patterns directly influences retrofit strategy. Tailored interventions are necessary, with solid-wall older homes often requiring internal or external insulation, while cavity walls in post-1975 homes may only need top-up insulation. Occupant behaviour must be considered, as heating patterns, ventilation habits, and appliance use significantly affect energy savings. Energy modelling through detailed simulations helps prioritise measures that maximise carbon reduction, comfort, and cost-effectiveness. An integrated approach combines fabric improvements, heating system upgrades, ventilation strategies, and, where feasible, the integration of renewable energy systems. In practice, a whole-house, fabric-first approach is most effective, addressing heat loss at the source before implementing mechanical systems. By understanding the specific characteristics of each dwelling and its energy use profile, retrofit measures can be optimised for maximum impact [38,39,40].

3. Regulatory and Standard Frameworks

The regulatory and standards framework is fundamental to guiding domestic retrofit activities in UK, providing the structure that ensures retrofit projects meet essential energy, safety, and performance requirements. However, as the UK moves toward its net-zero carbon target, ADL1 alone is often insufficient, prompting many projects to pursue higher performance standards that exceed basic legal thresholds. To bridge these gaps, voluntary frameworks, e.g., EnerPHit, Passivhaus Retrofit, and BREEAM Domestic Retrofit have gained prominence [41,42,43]. These standards emphasise high energy efficiency, airtight construction, and excellent indoor environmental quality. EnerPHit, in particular, adapts the rigorous Passivhaus principles for existing buildings, offering practical pathways for older or heritage properties. Achieving such standards requires a detailed understanding of the building’s fabric, baseline performance, and user needs. Retrofit Coordinators play a crucial role in this process, conducting comprehensive assessments and ensuring that proposed measures improve efficiency without introducing risks like condensation or poor ventilation [44]. Financially, while meeting minimum compliance may appear cost-effective initially, higher standards deliver greater long-term benefits through energy savings, improved comfort, and reduced maintenance. Ultimately, integrating regulatory compliance with voluntary best-practice frameworks supports not only the UK’s decarbonisation targets but also the creation of healthier, more resilient, and energy-efficient homes [45]. The comparison in Table 2 highlights a performance gap between mandatory and voluntary standards. While ADL1 provides a baseline, its permissible U-values and simplified treatment of TB are insufficient for achieving deep carbon reductions, underscoring the necessity for aspirational standards like EnerPHit in a net-zero context.

Table 2.

Comparison of Retrofit Standards [46,47].

4. Whole House Retrofit and Fabric-First Principles

The whole-house retrofit approach represents a fundamental shift in how domestic energy efficiency interventions are designed and implemented. Unlike traditional, piecemeal retrofits that focus on individual measures in isolation, a whole-house approach considers the dwelling as an interconnected system, where the building fabric, services, and occupant behaviour interact. This methodology is essential for ensuring that retrofit interventions deliver the intended energy savings, improve comfort, and avoid unintended consequences such as moisture accumulation or overheating. The whole-house approach to retrofit is founded on key principles that ensure comprehensive, effective, and sustainable outcomes. It begins with a holistic assessment of all building components, e.g., walls, roofs, floors, windows, doors, and services, to understand their interconnections. Retrofit measures are carefully integrated so that improvements in insulation align with airtightness and ventilation strategies, preventing issues like condensation. A lifecycle perspective is also essential, focusing on long-term durability, comfort, and reduced maintenance rather than short-term energy savings alone. Crucially, the approach remains occupant-centred, tailoring interventions to the needs, behaviour, and comfort preferences of residents to ensure that solutions are both practical and user-friendly. At the core of the whole-house retrofit concept is the fabric-first approach, which focuses on enhancing the building envelope before implementing mechanical or renewable energy systems. This philosophy aims to minimise heat loss, improve energy efficiency, and ensure long-term building performance by addressing inefficiencies directly within the fabric of the structure. Walls are a primary focus, with solid walls upgraded through internal or external insulation depending on space, appearance, and heritage constraints, while cavity walls are insulated with careful consideration of moisture control and cold bridging prevention. Roofs and lofts are also vital areas for intervention, where adequate insulation and controlled ventilation reduce vertical heat loss and prevent condensation-related damage. Floors, particularly suspended timber ones, are insulated to limit drafts and heat loss, while solid floors may incorporate rigid insulation or underfloor heating during extensive retrofits.

Similarly, upgrading windows and doors to high-performance double or triple glazing minimises conduction and air infiltration, with airtight sealing around frames to prevent bridging. Finally, achieving airtightness throughout the dwelling by sealing gaps and service penetrations reduces uncontrolled air leakage, though it must always be balanced with proper ventilation to maintain healthy indoor air quality [48]. A comparative evaluation of different window configurations is shown in Figure 1. The left panel illustrates the difference between single-glazed and double-glazed (insulated) windows (Figure 1a). The single-glazed window consists of a single pane of glass, which provides minimal thermal insulation and allows significant heat transfer and condensation on the interior surface. In contrast, the double-glazed window comprises two panes of glass separated by an air or inert gas gap, acting as an insulating barrier that reduces heat loss and condensation, thus improving the overall thermal performance of the building envelope. In Figure 1b, the right panel compares a window without a trickle vent and a window with a trickle vent. The trickle vent, indicated in red, allows controlled ventilation by enabling small amounts of fresh air to enter the interior space, helping to reduce indoor humidity, prevent condensation, and improve indoor air quality without the need to open the window fully.

Figure 1.

Comparison of different window configurations relevant to building retrofit applications, (a) Difference of single glazed and double glazed, (b) window without trickle vent and with trickle vent.

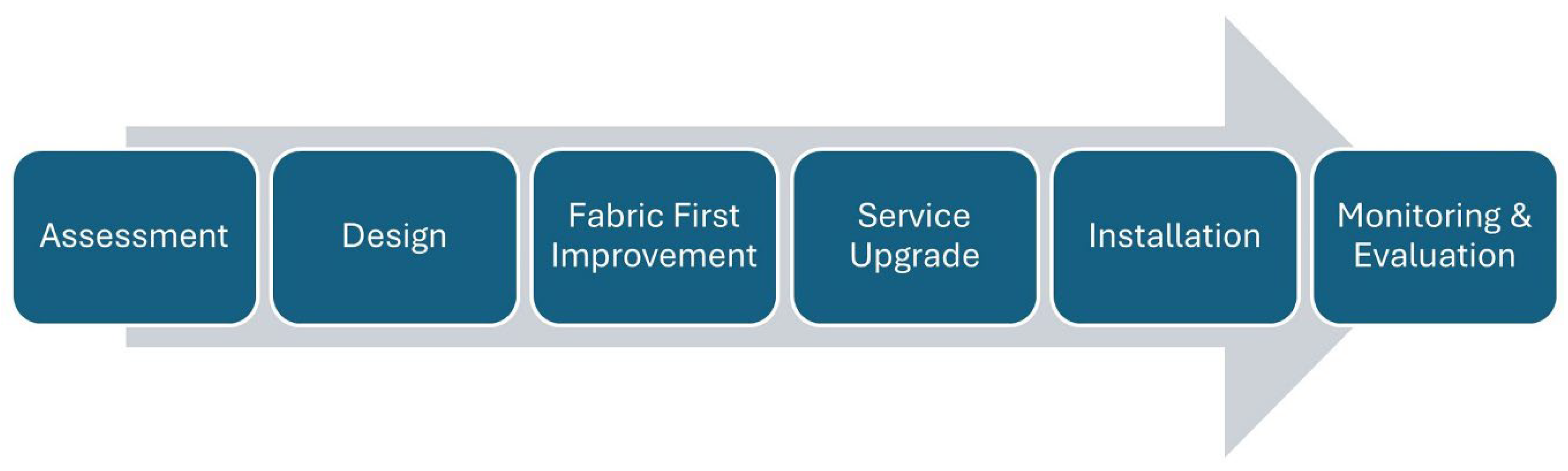

Adopting a whole-house, fabric-first retrofit strategy in UK dwellings offers multiple synergistic benefits. By prioritising enhancements to the building envelope, e.g., upgraded insulation, improved airtightness, and robust TB control, the energy demand for space heating is significantly reduced, yielding long-term operational savings and lower lifecycle costs. Improved envelope performance also leads to enhanced thermal comfort: homes become more stable in temperature, draughts are minimised and occupants report fewer cold spots and better comfort during colder seasons. Meanwhile, by reducing uncontrolled air infiltration and heat losses, fabric-first retrofits can meaningfully reduce a dwelling’s carbon emissions, aligning with the UK’s Net Zero 2050 ambitions (savings on average of 70–80% in monitored homes). In terms of moisture management, an integrated whole-house approach ensures that improved airtightness is balanced with adequate ventilation systems and correct detailing, thereby mitigating risks of condensation, mould growth, and associated health and durability issues. Figure 2 shows the flow diagram of whole house retrofit approach.

Figure 2.

A schematic of whole house retrofit approach.

5. Key Risks and Role of Retrofit Coordinators

Domestic retrofit, while offering substantial benefits in terms of energy efficiency, comfort, and carbon reduction, inherently carries a range of risks that can compromise both performance and safety if not managed appropriately. These risks arise from the complexity of existing building stock, the interactions between retrofit measures, occupant behaviour, and the technical demands of installing high-performance systems. Effective management of these risks is essential to ensuring the long-term success and reliability of retrofit interventions. The role of the Retrofit Coordinator is central to identifying, mitigating, and overseeing these risks throughout the retrofit process. Retrofit projects risks can be broadly grouped into fabric-related, service-related, and occupant-related categories. Fabric-related risks concern the physical structure of the building, where issues, e.g., TB at junctions and penetrations, poor air tightness, and gaps in insulation can lead to heat loss, condensation, and mould growth. These problems are particularly critical in older or heritage buildings, where inappropriate interventions like external wall insulation may damage original materials or create moisture traps. Service-related risks emerge when heating, ventilation, or electrical upgrades are poorly coordinated with fabric improvements, resulting in systems that are either oversized or underperforming. For instance, installing a heat pump in an inadequately insulated property may fail to deliver expected energy savings, while airtight homes lacking sufficient ventilation can suffer from poor indoor air quality and humidity issues. Operational and occupant-related risks arise when retrofit measures are misused or misunderstood, as incorrect operation of ventilation or heating systems can negate energy savings and reduce comfort. Structural concerns, fire safety, and health hazards especially in older homes containing materials like asbestos, also add to project complexity. Furthermore, poor workmanship, cost overruns, and scheduling delays can compromise retrofit quality and long-term performance, underscoring the need for rigorous planning, coordination, and quality assurance [49]. Understanding typical pitfalls in domestic retrofit underlines the critical need for coordinated risk management. One recurrent issue is TB at junctions and penetrations, which undermines insulation continuity, elevates heat loss and condensation risk, and may lead to mould growth if left unmanaged. Inadequate or poorly integrated ventilation systems further exacerbate the situation, as improved airtightness without matched mechanical or hybrid ventilation allows moisture loads to build, degrading indoor air quality and increasing fabric decay. Poor workmanship including incorrect detailing, insufficient sealing, or unskilled installation, frequently compromises retrofit outcomes and perpetuates performance gaps in the home’s thermal envelope. Uncoordinated retrofit measures, where individual upgrades (insulation, windows, services) are delivered without a coherent whole-house strategy, also heighten risk, as siloed interventions may create new thermal or moisture fault lines [50].

6. Energy Assessment and Performance Modelling

Accurate energy assessment and performance modelling are central to the planning, design, and evaluation of domestic retrofit projects in the UK. Performance modelling further allows retrofit professionals to predict outcomes, optimise interventions, and manage the risks associated with TB, moisture, and system integration [51,52]. A dwelling assessment is the essential first step in any retrofit project, conducted by energy assessors under the guidance of Retrofit Coordinators. It involves evaluating the building fabric for insulation gaps and thermal weaknesses, reviewing heating, hot water, ventilation, and electrical systems for efficiency and retrofit compatibility, analysing occupant behaviour to understand energy usage patterns, and assessing moisture and ventilation to prevent condensation and maintain indoor health. This thorough evaluation provides the foundation for selecting appropriate retrofit measures and developing a medium term improvement plan [53].

Once the assessment phase is complete, building performance modelling tools are employed to simulate the energy behaviour of dwellings under various retrofit scenarios, enabling data-driven decision-making and risk reduction. The Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP), developed by the UK Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, serves as the government’s primary methodology for calculating dwelling energy performance and compliance with Building Regulations Part L; it quantifies energy use for space and water heating, lighting, and renewable technologies. The Reduced Data SAP (RdSAP) version 10, a simplified variant designed for use in existing homes, enables assessors to model performance based on partial survey data, making it suitable for large-scale housing stock assessments and retrofit planning, albeit with limitations in sensitivity to local conditions and detailed TB effects. For more advanced analyses, dynamic thermal models, e.g., IES VE v2025, DesignBuilder v2025.1, and EnergyPlus v25.2.0, allow hourly simulation of temperature, moisture, and energy flows within buildings, accounting for occupant behaviour, solar gains, and ventilation strategies. These dynamic tools provide deeper insights into the interaction between retrofit measures (insulation, glazing, and airtightness) and occupant comfort, making them invaluable for assessing overheating risk and refining whole-house, fabric-first retrofit designs.

Although RdSAP and similar simplified energy assessment models are widely adopted for evaluating domestic retrofit performance, they exhibit several limitations that must be acknowledged by practitioners. First, such models handle TB only through generic linear transmittance values or default assumptions, which can lead to underestimation of localised heat losses and surface condensation risks, especially at junctions and penetrations. Second, the simplified algorithms in RdSAP lack dynamic representation of moisture and condensation effects, neglecting hygrothermal coupling that influences insulation performance and long-term material durability. Third, the model assumes standardised usage patterns and internal gains, meaning occupant behaviour (heating schedules, ventilation practices, and window opening habits) is treated statically, leading to discrepancies between predicted and actual energy use. In such cases, dynamic simulation environments provide a more accurate representation of whole-house performance and risk assessment. Recognising these modelling constraints is essential to ensure that energy performance predictions realistically inform retrofit design and policy [54]. In parallel, models help quantify carbon-reduction potential, translating predicted energy savings into avoided greenhouse-gas emissions and enabling alignment with national Net Zero trajectories. Equally important is the assessment of occupant comfort, encompassing thermal stability, indoor air quality, and daylight access, all of which directly influence occupant satisfaction and health. Collectively, these factors underscore that robust performance modelling is not only a technical exercise but also a decision-support tool for designing safe, cost-optimal, and low-carbon retrofit strategies [55,56].

Energy performance simulation is an essential analytical tool for informing evidence-based retrofit decision-making. Through scenario comparison, it allows practitioners to test multiple retrofit configurations under varying climatic and occupancy conditions to identify the most effective combinations for energy and carbon reduction. Simulation also supports risk mitigation by predicting potential unintended consequences, including overheating, interstitial condensation, and ventilation imbalance, thereby enabling designers to refine details before implementation. From a financial perspective, the predictive outputs of modelling assist in financial planning, allowing stakeholders to assess payback periods, whole-life cost implications, and cost–benefit ratios across alternative retrofit pathways. Finally, simulation tools play a critical role in the verification of standards compliance, ensuring that proposed retrofit designs meet or exceed regulatory benchmarks. Consequently, energy performance simulation serves not only as a diagnostic instrument but also as a strategic enabler of low-carbon, high-quality, and compliant retrofit delivery across the UK housing stock [57].

7. Heat Loss, Gain, and Moisture Management

Understanding the dynamics of heat loss, heat gain, and moisture is fundamental to the design and implementation of effective domestic retrofit measures. These factors influence not only the energy performance of a dwelling but also occupant comfort, indoor air quality, and long-term durability of building fabric. Effective management of heat and moisture is particularly critical in the UK’s varied housing stock, where older buildings with solid walls and uninsulated roofs present unique challenges, and modern buildings with high airtightness require careful ventilation strategies. The thermal performance of UK dwellings is governed by the balance between heat loss and heat gain, both of which critically influence energy demand, occupant comfort, and carbon emissions. Heat loss occurs when thermal energy escapes from the interior to the exterior, driven by temperature differences and influenced by the properties of the building envelope, the presence of thermal bridges, and the efficiency of heating systems [58,59,60]. Key pathways include conduction through the building fabric, where walls, roofs, floors, and windows allow energy transfer proportional to their thermal transmittance; TB at junctions, penetrations, and structural discontinuities, which can locally increase heat loss and condensation risk; air infiltration through gaps, cracks, or poorly sealed openings; and ventilation losses, where mechanical or natural ventilation removes conditioned air from the dwelling. Conversely, heat gain represents the absorption of energy from external and internal sources, which can be harnessed to reduce reliance on active heating. This includes solar gains through windows and opaque surfaces, internal gains from occupants, appliances, and lighting, and passive gains from building systems such as heat recovery or thermal mass utilisation. Effective management of both heat loss and heat gain is central to fabric-first retrofit strategies, ensuring that dwellings achieve optimal energy efficiency, thermal comfort, and reduced carbon emissions without compromising indoor environmental quality.

Moisture in dwellings exists in both liquid and vapour forms and interacts closely with heat flows, influencing both building durability and indoor environmental quality [61]. Excess moisture can lead to structural damage, decay of building materials, and the proliferation of mould, which adversely affects occupant health and comfort. Effective moisture management in retrofit projects requires consideration of multiple factors. Condensation risk arises when warm, humid indoor air contacts cold surfaces, leading to localised moisture accumulation; careful design of insulation, airtightness, and ventilation is essential to mitigate this risk. Relative humidity and indoor air quality must be monitored and controlled, as elevated humidity levels increase the likelihood of microbial growth and reduce occupant comfort. Capillary flow and liquid diffusion govern the movement of moisture within porous building materials, influencing the potential for interstitial condensation and long-term fabric degradation. Heat and moisture flows are closely interrelated, and mismanagement of either can compromise retrofit performance. For instance, improving airtightness without addressing ventilation can lead to high indoor humidity and condensation on cold surfaces. Similarly, insulating walls without allowing for moisture movement can trap water within the fabric, increasing the risk of decay. Effective retrofit therefore requires an integrated approach that considers the thermal and hygrothermal behaviour of the building as a system.

Figure 3 illustrates the implementation of targeted ventilation and heating controls as critical components of a holistic retrofit strategy. The figure contrasts pre- and post-retrofit conditions in key household areas, e.g., (a) kitchen, (b) bathroom, (c) boiler area, and (d) common room, respectively, lacking mechanical ventilation, a state that promotes poor indoor air quality, moisture accumulation, and mould growth. The retrofit solution, shown in panels, addresses this by installing extractor fans, which actively expel humid air and contaminants, thereby safeguarding the building fabric and occupant health. Furthermore, Figure 3d highlights the installation of thermostatic radiator valve (TRV), with the lock shield valve enabling system balancing and the TRV providing localised, room-by-room temperature control. Together, these measures significantly enhance the building’s performance by improving air quality, managing humidity, and reducing energy consumption through more precise thermal management, ensuring the retrofit delivers both efficiency and occupant comfort.

Figure 3.

Comparison of pre-retrofit and post-retrofit conditions for ventilation and heating controls in key household areas. The pre-retrofit state (left image of all selected areas) shows a lack of mechanical ventilation, leading to poor indoor air quality and moisture accumulation. The post-retrofit solution (right image) addresses this through the installation of extractor fans in (a) the kitchen and (b) bathroom to expel humid air and contaminants, (c) boiler upgrade. Panel (d) highlights the installation of a TRV and lock shield valve in the common room, enabling precise, room-by-room temperature control and system balancing. These measures collectively enhance indoor air quality, manage humidity, reduce energy consumption, and improve occupant comfort.

Effective management of heat and moisture is central to achieving durable, energy-efficient outcomes in domestic retrofit projects. The fabric-first approach, which prioritises improvements to walls, roofs, floors, windows, and doors before mechanical systems, reduces uncontrolled heat loss and stabilises indoor temperatures while minimising condensation risk. Thermal bridge mitigation, through careful detailing at junctions, penetrations, and structural interfaces, further reduces localised heat loss and the potential for interstitial condensation. Controlled ventilation, including mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR) or well-designed natural ventilation, ensures adequate air exchange while maintaining indoor humidity within safe limits, thereby protecting occupant health and indoor air quality. The use of moisture-tolerant materials, such as breathable insulation, lime-based renders, or hygroscopic finishes, allows the building fabric to safely absorb and release moisture, mitigating the risk of mould and decay [62]. An overview of heat loss and gain in a dwelling is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

An illustration of heat transfer mechanism in a dwelling.

8. Fabric Retrofitting Techniques

The performance of a building’s fabric (walls, roof, floors, windows, and doors) plays a central role in determining energy efficiency, thermal comfort, and the durability of domestic dwellings. Fabric retrofitting techniques aim to reduce heat loss, minimise TB, and improve airtightness while maintaining moisture balance. In the context of UK dwellings, which vary widely in age, construction type, and condition, the choice of retrofitting techniques must be tailored to the specific characteristics of each property.

8.1. Wall, Roof and Loft Insulation

Walls are a major source of heat loss in UK dwellings, particularly in older solid-wall properties, making their retrofit a priority for energy efficiency improvements [63]. External Wall Insulation (EWI) enhances thermal performance by applying insulation to the building’s exterior, maintaining internal space while requiring careful detailing to prevent moisture ingress and TB. While EWI is highly effective, its application is often limited by planning constraints in heritage zones and requires meticulous detailing at junctions to avoid creating new moisture traps, a challenge frequently reported in post-installation evaluations [64]. Internal wall insulation adds insulation to the interior surface, preserving the façade but potentially reducing usable floor area and necessitating careful material selection to avoid condensation and mould. Cavity wall insulation suitable for buildings with a cavity between the inner and outer wall leaves, involves injecting insulating material into the cavity to limit heat loss, though proper assessment is crucial to mitigate risks of damp and inadequate performance. A building envelope before and after EWI is presented in Figure 5. The left panel presents a before-and-after comparison of a building front retrofitted with EWI. The “Before” image shows a traditional uninsulated brick wall, which typically exhibits high heat loss through the building envelope. After the retrofit, the building is upgraded with EWI and a rendered finish, which provides a continuous layer of thermal insulation on the exterior surface. This approach effectively reduces heat transfer, enhances thermal comfort, and improves the overall energy efficiency of the structure without altering internal space. Moreover, the right panel (Figure 5b) illustrates additional advanced retrofit strategies that further enhance building performance. These include external insulation for improved thermal resistance, a green roof system for better thermal regulation and stormwater management, and thermal bridge-free detailing to eliminate localised heat loss points. Together, these measures contribute to reducing the building’s heating demand, minimising carbon emissions, and improving the aesthetic and environmental performance of existing housing stock.

Figure 5.

Examples of building envelope retrofit strategies through EWI systems, (a) External wall insulation with render finish, (b) external wall insulation, green roof and thermal bridging.

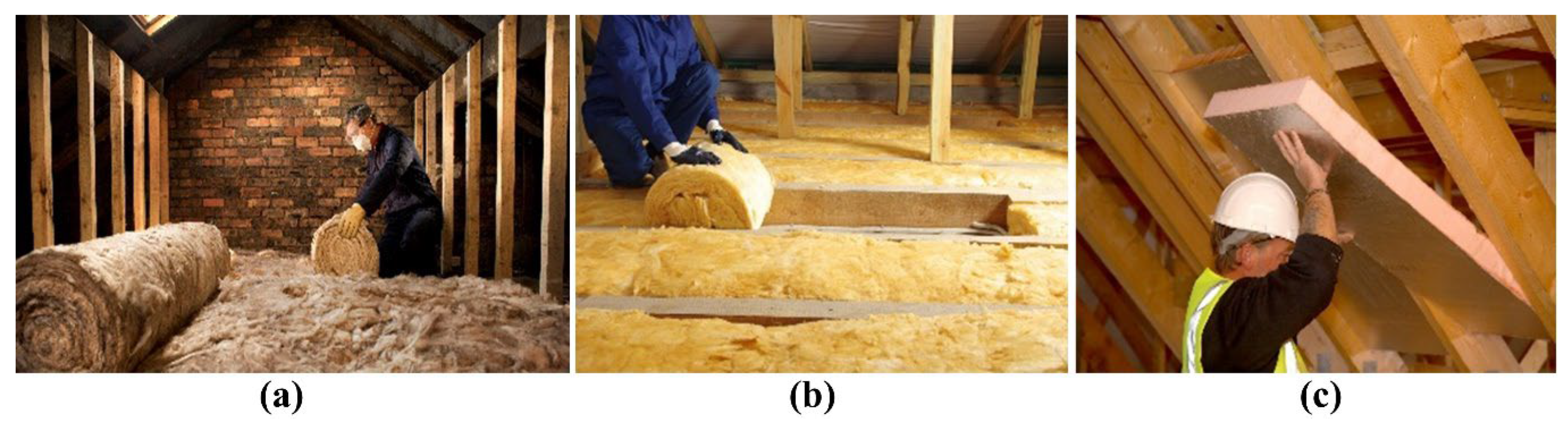

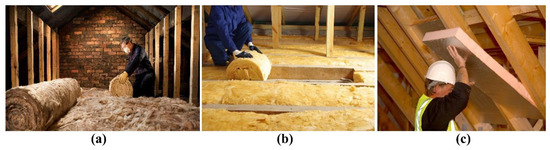

Roofs and lofts are significant sources of heat loss in UK dwellings, particularly in older properties with inadequate insulation. Retrofitting these areas is essential for improving energy efficiency and occupant comfort. Loft insulation is one of the most effective measures, with UK regulations in 2024 requiring a minimum thickness of 270 mm to achieve a U-value of 0.16 W/m2K, along with proper ventilation and fire safety compliance. Studies have shown that loft insulation can save a detached UK home up to GBP 340 in annual energy bills and reduce the domestic carbon footprint by up to 1 ton per year. For pitched roofs, insulating between the rafters or above the rafters can significantly reduce heat loss, with costs ranging from GBP 19 to GBP 45 per square metre, depending on the insulation material used and the complexity of the installation process. Flat roof insulation, particularly using polyisocyanurate foam, is effective in meeting the thermal performance and moisture control requirements of UK Building Regulations, making it suitable for all flat roofs of buildings in England regardless of height. Proper installation of these insulation measures is crucial to avoid issues such as condensation and mould growth, which can arise from substandard workmanship and inadequate ventilation [65,66]. A roof insulation method in 3 steps is presented in Figure 6. The installation of loft insulation using mineral wool rolls (Figure 6a,b), a common and cost-effective retrofit measure to reduce heat loss through the roof structure, is presented. The insulation is typically unrolled and laid between and across the ceiling joists to achieve the required thermal resistance. This method significantly improves the thermal performance of the attic space by minimising conductive heat transfer and maintaining indoor temperature stability. Figure 6c demonstrates the application of rigid insulation boards (polyurethane or polystyrene panels) fitted between or beneath rafters. This approach provides higher thermal efficiency per unit thickness and is particularly suitable for pitched roofs where additional insulation can be installed without compromising interior space.

Figure 6.

Illustration of roof insulation methods applied during building retrofit, (a) insulation unrolling, (b) laying down across the ceiling joints, (c) fitting of rigid insulation board.

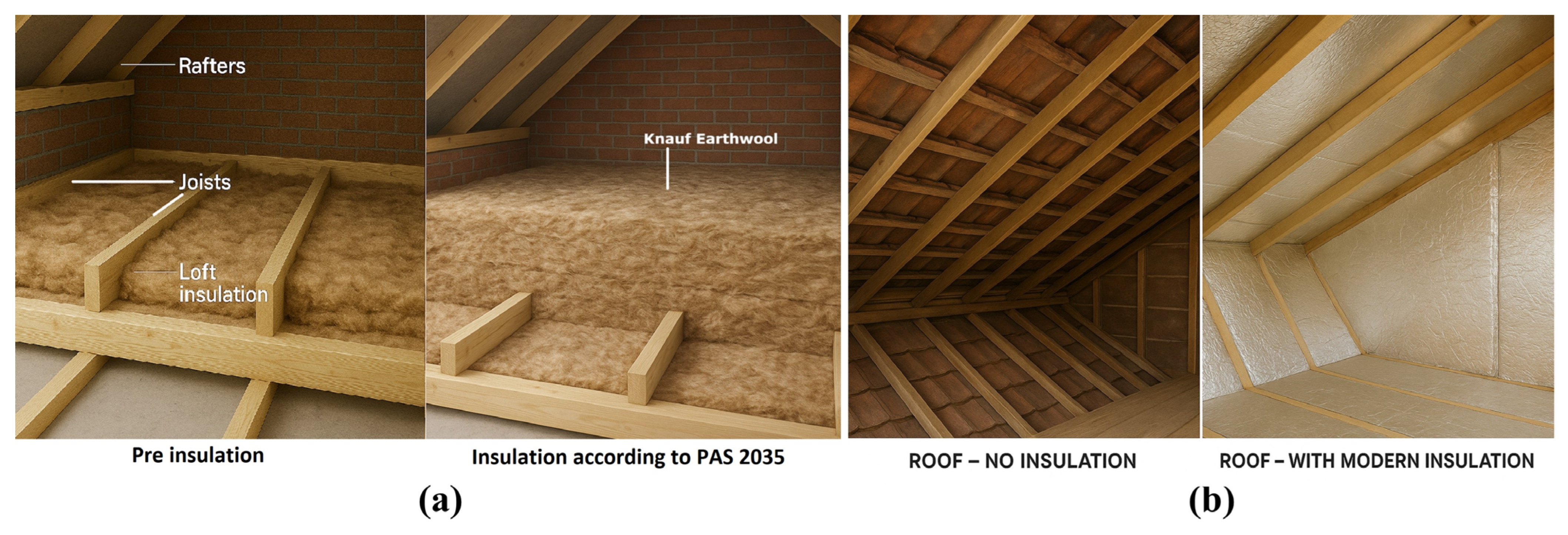

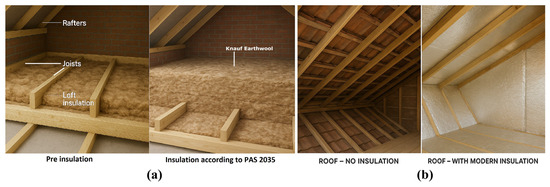

Figure 7 delineates a critical detail for the thermal retrofit of the building envelope at the roof edges junction. It contrasts the pre-retrofit condition, characterised by a lack of insulation and significant TB at the joints, with the post-retrofit solution. The modern intervention involves the installation of a continuous layer of loft insulation, specifically Knauf Earthwool by Knauf Insulation Ltd., Helens, UK, which is extended over the wall plate to create an unbroken thermal barrier. This methodology is executed in compliance with PAS 2035 standards and is fundamental to enhancing the overall thermal performance of the envelope. By effectively sealing this critical junction, the retrofit mitigates heat loss, improves airtightness, and prevents the risk of interstitial condensation, thereby ensuring the building’s energy efficiency and long-term durability.

Figure 7.

The illustration of two stages, i.e., (a) pre-retrofit: the original roof with little or no effective insulation, and (b) post-retrofit: the same roof after being upgraded with modern insulation materials and techniques, of a roof’s construction.

8.2. Floor Insulation Techniques

Floors can be a significant source of heat loss in older UK dwellings especially those with suspended timber construction, and retrofitting the floor element is a key component of a fabric-first strategy. For suspended timber floors, insulation may be installed between the joists, from below, or over the floorboards so as to reduce both conductive losses and draught infiltration; for example, monitored retrofit work on a Victorian house showed that insulating the void beneath a suspended timber floor led to reductions in floor heat loss of between 65% and 92%, depending on insulation type and detailing. Meanwhile, for solid floors, insulation is commonly introduced as rigid boards or floating screeds laid above the existing slab; careful attention must be paid to moisture control, floor-height changes, and thinner insulation depths since the ground-contact slab already moderates temperature. When selecting between techniques, retrofit designers must assess the existing floor type, sub-floor ventilation especially for suspended floors, the potential for raising finished floor level (more pronounced for solid floors), and integration with adjoining envelope upgrades to avoid creating new thermal bridges or moisture paths. The measured reductions in heat loss underpin the long-term cost-effectiveness and performance gains of floor insulation within whole-house retrofit schemes. Figure 8 delineates a fundamental retrofit strategy for improving the thermal performance of a building’s ground floor assembly. The left panel depicts the pre-retrofit condition, where the floor structure lacks any thermal barrier between the conditioned space above and the ground or crawl space below. This results in significant heat loss, cold floors, and substantial thermal discomfort for occupants, making it a major source of energy inefficiency. However, the right panel presents the comprehensive retrofit solution. This involves the installation of a high-performance insulation layer beneath the floor deck, which acts as a thermal break to minimise heat transfer downwards. Crucially, this insulation system is integrated with an underfloor heating pipe network, creating an efficient and comfortable heating solution. The synergy of insulation and heating pipe network ensures that the generated heat is directed upwards into the living space rather than being dissipated into the ground, thereby enhancing overall energy efficiency, providing radiant comfort, and modernising the building’s heating distribution system. This upgrade is critical for eliminating a key thermal bridge and transforming the floor from a liability into an active, efficient component of the building’s envelope.

Figure 8.

Comparison of uninsulated and insulated underfloor heating installation.

8.3. Windows and Doors

Retrofitting windows and doors is a critical component of a fabric-first strategy in UK dwellings, as these elements can significantly influence both heat loss and occupant comfort. Upgrading to double or triple glazing can substantially reduce heat loss: for instance, double-glazed units may achieve U-values around 1.2–1.6 W/m2K, while triple glazing can push down below ~0.8 W/m2K, thereby markedly lowering conductive and radiative heat transfer. Equally important are the window frames, since materials with high conductivity (non-thermally broken aluminium) create cold-bridging and undermined performance, whereas thermally broken frames or timber/composite profiles reduce conductive paths and condensation risk. For doors, particularly external entrance or patio-type units, similar principles apply: improved insulation, airtight sealing, and compatibility with upgraded glazing matter for reducing infiltration and TB. Moreover, shading and overheating considerations must be addressed when retrofitting: well-insulated glazing units may reduce heat losses but also reduce beneficial solar gains and potentially increase risk of summertime overheating if shading is not provided or ventilation is not managed. These improvements to windows and doors enhance thermal performance, reduce energy demand, improve comfort and indoor air quality, support carbon-reduction goals, and are best delivered as part of a holistic whole-house retrofit approach rather than as isolated upgrades [67].

8.4. Airtightness and Ventilation

Effective retrofitting demands careful attention to both, sealing gaps and penetrations, and ensuring controlled ventilation, because achieving a fabric-first upgrade without managing airflows can undermine performance and occupant health. High levels of airtightness reduce uncontrolled infiltration and heat loss through the building envelope, draught-proofing and sealing service penetrations have been shown to reduce air permeability significantly, thereby cutting heating demand and carbon emissions. At the same time, once the dwelling becomes tighter, controlled ventilation becomes essential: maintaining adequate fresh-air exchange prevents moisture accumulation, mould growth, and poor indoor air quality. For instance, research has shown that when indoor ventilation is not adapted after airtight improvements, pollutant and moisture levels can rise, jeopardising health and durability. In practice, retrofit schemes following the “build tight, ventilate right” principle must plan for airtightness improvements and select appropriate ventilation types, e.g., extract ventilation, mechanical ventilation with heat recovery, based on the building’s performance and occupant behaviour. Integrating these twin strategies ensures that fabric-first upgrades deliver their energy and comfort benefits without unintended consequences (overheating, stale air or moisture risks) thereby supporting long-term durability, indoor environmental quality, and carbon reduction goals [49].

8.5. Materials Considerations

The selection of materials is critical to the success of fabric-first retrofit interventions, particularly when aiming to balance thermal performance with long-term durability and moisture management. First, the use of moisture-tolerant insulation, i.e., materials that are vapour-open, capillary-active or otherwise compatible with hygrothermal dynamics, is essential in older or traditional building fabrics to avoid moisture trapping and subsequent degradation. A study emphasises the importance of vapour permeability and “breathability” in insulation specification for traditional construction. Second, durability of insulation materials must be considered: a 2025 UK government study found that retrofit insulation performance can deteriorate over time due to moisture, corrosion, or material change, highlighting the need for materials that resist mould growth, maintain thermal conductivity and preserve integrity. Third, compatibility of materials with the existing building fabric and construction details is paramount mismatches in vapour resistance, thermal expansion or interface behaviour can lead to unintended moisture risks, cold bridging or structural damage. For example, in historic buildings, using impermeable insulation layers behind moisture-open masonry has been shown to create condensation risk zones at the insulation-wall interface [68]. Together, these considerations underscore that effective retrofit is not just about adding insulation, but about selecting the right material for the right context one that integrates with the existing system, manages moisture and heat flows, and retains its performance over the building’s lifespan.

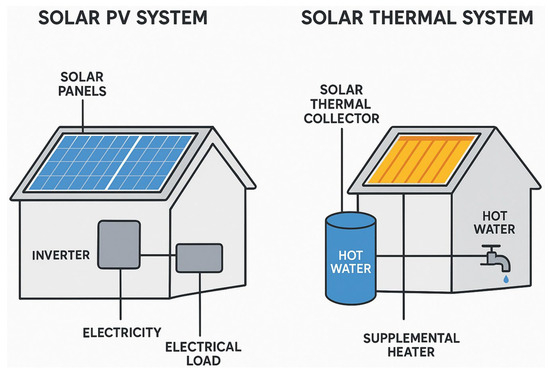

9. Building Services and Renewable Energy Integration

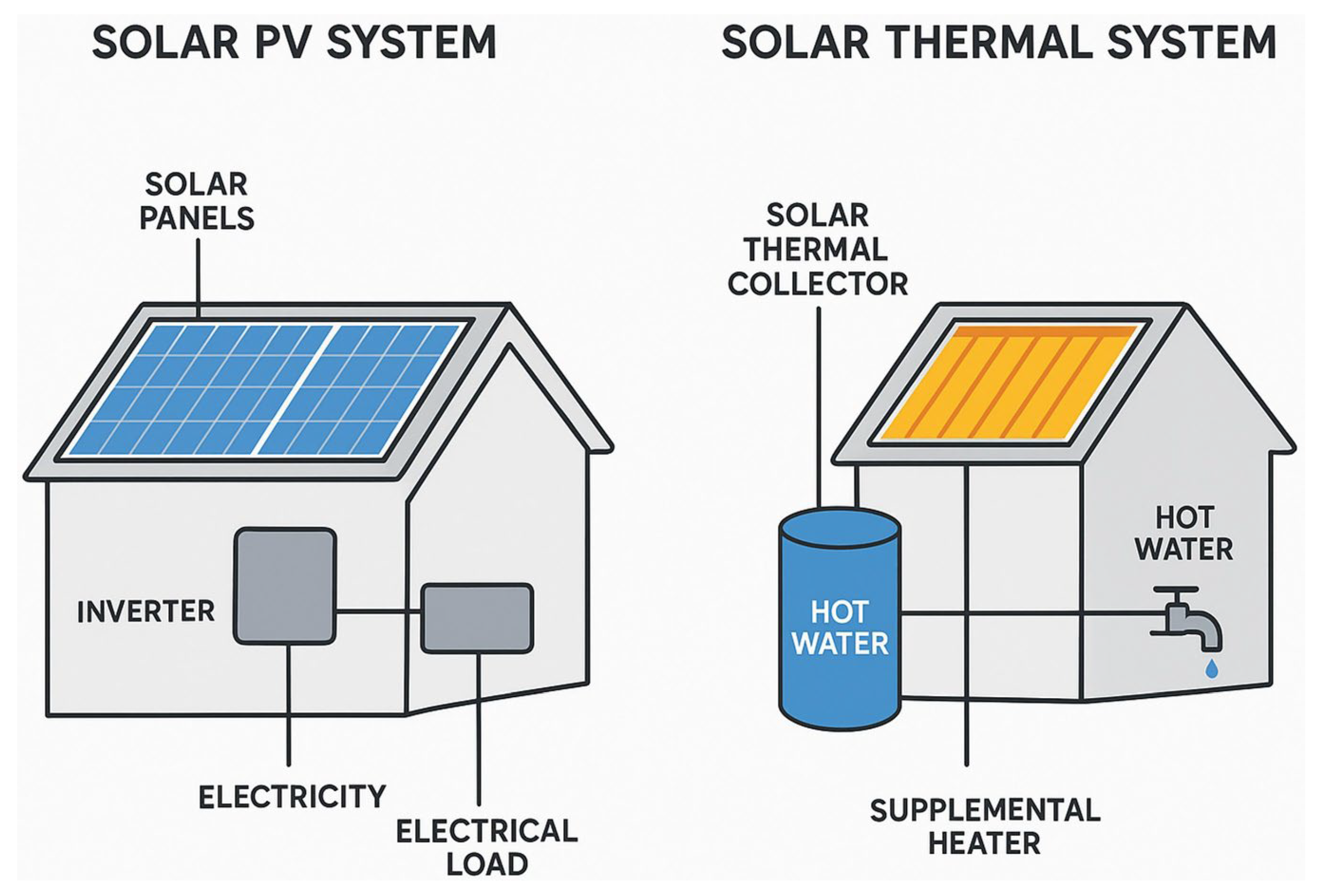

Upgrading building services and integrating renewable energy systems are key components of domestic retrofit, complementing fabric improvements to achieve whole-house energy efficiency, reduced carbon emissions, and improved comfort. While fabric-first measures reduce heat loss and improve thermal performance, efficient heating, hot water, ventilation, and electricity supply systems are essential for delivering the intended energy and carbon savings. Additionally, renewable energy technologies PV, solar thermal, heat pumps, and biomass systems provide opportunities to reduce reliance on fossil fuels, enhance sustainability, and align with the UK’s net-zero targets. Figure 9 illustrates the two principal pathways for retrofitting a building with solar energy technology, i.e., Solar PV System and solar thermal system. The diagram clearly delineates the distinct inputs and outputs of each system, providing a comparative overview for decision-making in retrofit projects. The solar PV pathway utilises panels to convert sunlight directly into electricity, which can be used to power the building’s general electrical loads, thereby reducing grid dependence and associated carbon emissions. In contrast, thermal pathway employs a solar thermal collector to capture the sun’s energy as heat, which is specifically used to produce domestic hot water. The inclusion of supplemental heating in the thermal system acknowledges the common retrofit practice of integrating the solar thermal unit with a conventional water heater to ensure a reliable supply.

Figure 9.

Pathways for solar energy retrofit: photovoltaic vs. solar thermal systems.

9.1. Heating System Upgrades

Heating typically accounts for the largest share of domestic energy use, so selecting an efficient and appropriate system is essential when undertaking a retrofit. For homes still on the gas network, gas-fired central heating remains common but its carbon emissions and dependence on fossil fuels make it less viable over the long-term under net-zero pathways. For dwellings off the mains gas grid, non-mains gas solutions (oil, LPG or biomethane) continue to be used, but they generally exhibit higher fuel cost volatility and carbon intensity, making them an interim rather than a future-proof option. Heat pumps, particularly air-source and ground-source, offer a low-carbon alternative, with studies showing that deployment across UK housing stock could reduce residential heating energy demand by up to ~40% compared with current systems when combined with fabric upgrades. The choice among these systems must consider dwelling type, existing infrastructure, fuel availability, retrofit fabric performance, and occupant needs, to maximise long-term performance, comfort and carbon reduction.

9.2. Hot Water Systems

The optimisation of domestic hot water (DHW) systems represents a critical pathway in the low-carbon building retrofit agenda, given that DHW can account for up to 25% of a typical home’s total energy demand. Key retrofit strategies focus on minimising both heat generation energy and distribution losses. The choice between storage-based and instantaneous systems is foundational, while modern instantaneous heaters eliminate standby heat loss entirely, large storage tanks are often necessary to effectively integrate low-temperature, low-output renewable technologies such as air source heat pumps and solar thermal collectors. In these scenarios, the use of a thermal store or buffer tank is a robust strategy, providing a hydraulic separation that enables efficient heat pump cycling and allows for multi-source integration, simultaneously delivering high-flow DHW at mains pressure via an internal heat exchanger. Furthermore, addressing distribution efficiency is a highly cost-effective measure; studies demonstrate that rigorous insulation of pipework particularly in unheated voids and the rationalisation of pipe runs (reducing pipe length and diameter) are essential to decrease “dead-leg” volumes and minimise the thermal energy wasted before hot water reaches the point of use [69].

9.3. Ventilation and Air Quality

Achieving improved airtightness through fabric retrofitting is fundamental to minimising thermal losses, yet this necessitates a carefully engineered ventilation strategy to maintain healthy indoor air quality (IAQ) and prevent interstitial and surface moisture accumulation [70]. MVHR is recognised as the optimal strategy for highly airtight retrofits. MVHR systems continuously supply filtered fresh air and extract stale, moist air, transferring up to 90% of the outgoing air’s heat energy to the incoming air stream via a counter-flow heat exchanger, drastically reducing the heating demand associated with ventilation. In contrast, reliance on natural ventilation, typically through background vents, trickle vents, or intermittent opening of windows, becomes problematic in highly sealed dwellings. While providing simple IAQ control, this method is fundamentally non-recoverable, leading to significant heat penalty losses and often suffering from occupant compliance issues or underperformance due to insufficient stack effect or wind pressure, thereby risking poor air exchange and potentially leading to condensation and mould growth in colder climates [71].

9.4. Renewable Energy Integration

Incorporating renewable energy technologies into domestic retrofits substantially enhances sustainability and helps meet UK decarbonisation targets by reducing grid demand and on-site carbon emissions; rooftop solar PV systems are the most widely deployed household technology and deliver predictable electricity generation, particularly where combined with battery storage and demand-shifting strategies. Solar thermal collectors remain a cost-effective option for displacing gas or electric water heating in many UK dwellings, offering high seasonal heat contribution when correctly sized and integrated with hot-water systems. Hybrid PV-T (photovoltaic-thermal) panels which produce electricity while capturing waste heat are an emerging technology that can improve overall energy yield and lower system-level costs by cooling PV cells and recovering thermal energy for domestic hot water or space-heating pre-heat. Small-scale wind turbines have been explored for some dwelling types (notably exposed or rural sites), but their variable output, siting constraints and higher per-kWh costs limit widespread domestic applicability across the UK urban stock. When selecting technologies for retrofit projects, designers should appraise roof orientation and structural capacity, local wind resource, hot-water and space-heating profiles, grid-connection constraints and whole-house decarbonisation objectives to determine the optimal mix of renewables that complements fabric-first measures [72].

Building-Integrated photovoltaics (BIPV) and smart windows represent a transformative leap in renewable energy integration, moving beyond mere energy generation to become multifunctional components of the building envelope itself. The BIPV market is experiencing rapid growth, projected to reach a global value of $42 billion by 2029, driven by innovations in materials like perovskite solar cells which offer high efficiency and versatility for facades and transparent glazing [73]. These systems do not just generate clean electricity; they replace conventional building materials, providing thermal insulation, noise reduction, and contributing directly to nearly Zero Energy Building requirements by covering a significant portion of a building’s energy demand [74]. Complementing BIPV, smart window technologies are advancing to dynamically manage solar heat gain, a critical factor given that up to 30% of a building’s heating and cooling energy is lost through windows [75]. Electrochromic and thermochromic windows can automatically adjust their tint in response to sunlight or temperature, significantly reducing cooling loads and enhancing occupant comfort. A key innovation is the development of self-powered smart windows and materials that operate without external electricity, using only solar heat to activate, thereby aligning with net-zero energy principles [76]. The synergy of BIPV and smart windows transforms the building facade from a passive element into an active, responsive, and energy-producing system, which is fundamental to achieving deep energy savings and the rigorous standards of net-zero energy buildings.

Government schemes for domestic and non-domestic properties, provide financial support for renewable installations. Energy performance modelling is essential to assess payback, carbon savings, and eligibility for incentives. Metrics such as simple payback, carbon cost-effectiveness, and total lifecycle costs help homeowners and retrofit coordinators make informed decisions. Integrating building services and renewable systems within a whole-house retrofit framework ensures that energy efficiency gains are maximised and sustained over time. First, fabric-first alignment is crucial, renewable and mechanical systems must complement a well-insulated, airtight building envelope, as poor coordination can lead to oversizing, inefficiency, and comfort issues. Second, system coordination between heating, ventilation, and renewable systems supports balanced operation, efficient energy flows, and effective demand-side management. Integrated system design supported by smart controls and real-time monitoring has been shown to enhance performance and reduce operational carbon emissions in UK dwellings. Finally, occupant education plays a pivotal role in ensuring that residents understand and operate retrofit systems effectively. Post-installation monitoring is a critical phase in ensuring that retrofit interventions achieve their intended performance outcomes and continue to deliver energy, comfort, and carbon reduction benefits over time. Energy use tracking through smart meters and sub-metering systems enables continuous evaluation of household energy consumption patterns, helping identify deviations from predicted savings and operational inefficiencies.

10. Monitoring, Evaluation, and PAS 2035 Compliance

Monitoring and evaluation are critical components of domestic retrofit, ensuring that the measures implemented deliver their intended energy savings, comfort improvements, and carbon reduction. These activities are formalised, structured, and mandated as part of a whole-house retrofit strategy. Compliance with PAS 2035 ensures quality assurance, risk management, and performance verification, providing confidence to homeowners, retrofit coordinators, and regulatory bodies that interventions are both effective and safe. Post-retrofit monitoring plays a vital role in ensuring that the predicted energy, comfort, and carbon reduction outcomes of retrofit projects are achieved in practice. First, performance verification enables the comparison of actual in-use performance against modelled expectations, validating the effectiveness of design assumptions and installation quality. This verification process supports compliance with frameworks and provides evidence of return on investment for stakeholders. Second, early problem detection through continuous data monitoring, smart metering, and thermal imaging allows practitioners to identify emerging issues, e.g., TB, poor insulation continuity, or malfunctioning systems before they compromise performance or occupant comfort. To ensure comprehensive oversight of retrofit projects, multilevel monitoring and evaluation is performed. Intermediate monitoring involves assessing the retrofit’s progress during installation to ensure compliance with design specifications and quality standards. This phase includes verifying that insulation materials are correctly installed and that air barriers are continuous. Intermediate monitoring helps identify issues early, reducing the risk of costly rectifications later. Post-retrofit testing is conducted after completion to confirm that the retrofit meets performance standards:

- Air-tightness testing measures the dwelling’s air permeability to ensure that unplanned air leakage is minimised, which is crucial for maintaining energy efficiency and indoor air quality.

- Thermography utilises infrared cameras to detect heat loss areas, identifying insulation gaps or TB that could compromise the building’s performance.

- System commissioning involves verifying that heating, ventilation, and renewable energy systems are correctly installed, calibrated, and operating as intended.

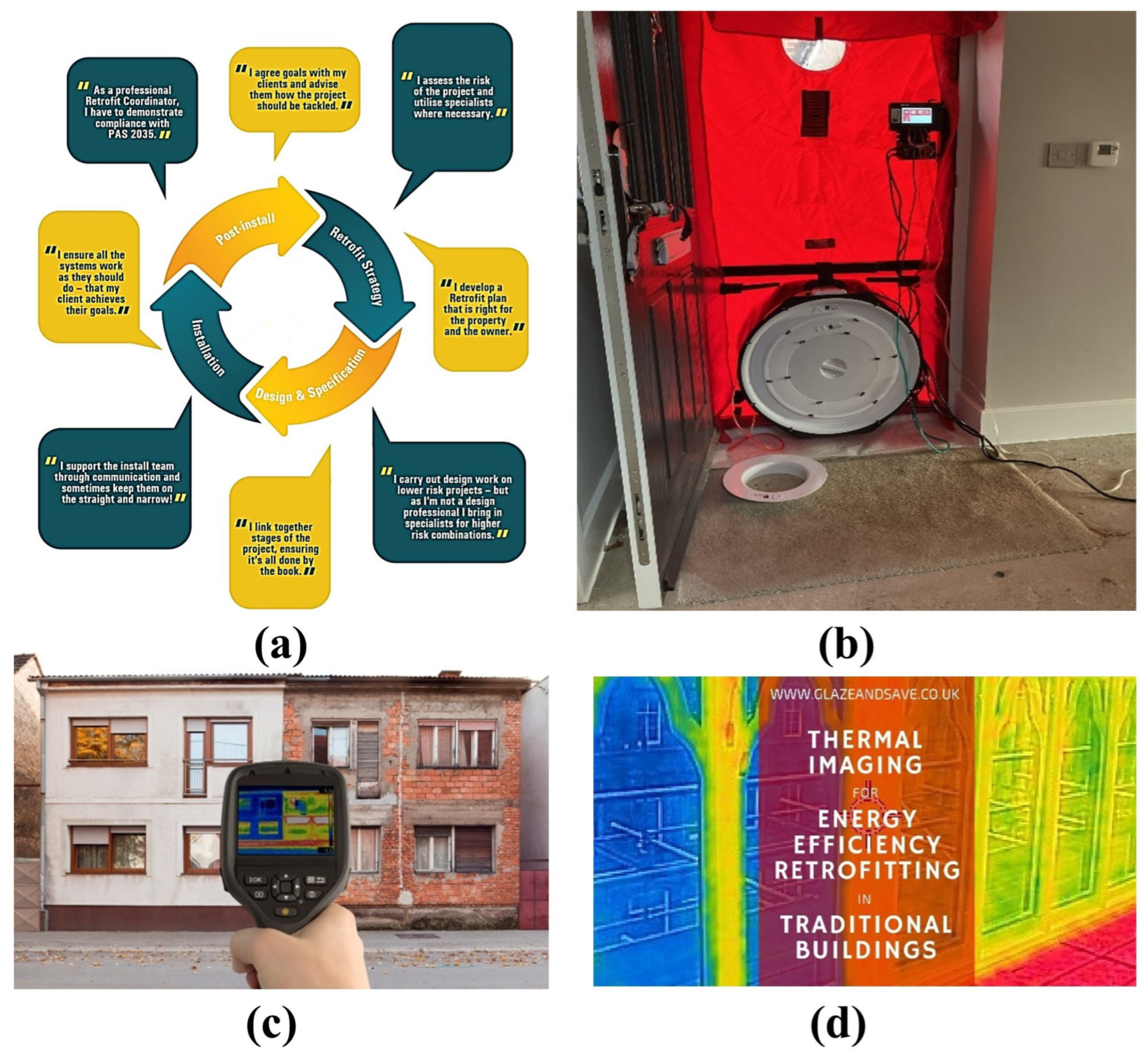

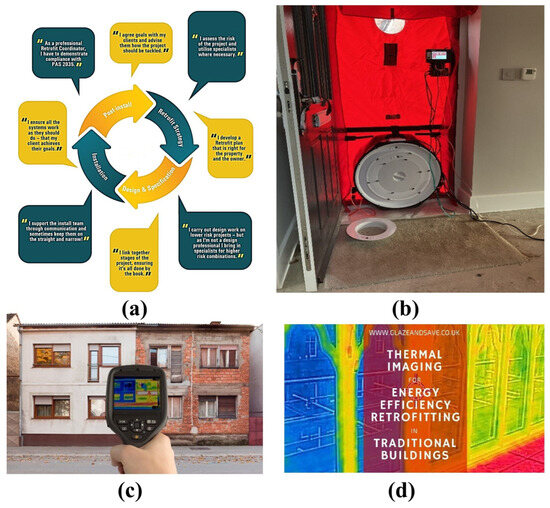

Ongoing evaluation ensures that the building performs as expected over time. This phase includes tracking energy consumption, indoor environmental conditions, and occupant feedback to identify any deviations from anticipated performance and to inform future retrofit projects. These monitoring and evaluation stages are essential for validating the success of retrofits and for ensuring that they contribute effectively to energy efficiency and carbon reduction goals [77]. Figure 10 outlines the critical responsibilities and competencies of a retrofit coordinator, a central role for energy efficiency retrofit projects. Key responsibilities include demonstrating competence, establishing project goals with clients, and conducting risk assessments to engage specialists when needed. The coordinator is further responsible for developing a suitable retrofit plan, linking all stages of the project to ensure cohesion, and supporting the installation team through communication and oversight. Effective monitoring of retrofit projects integrates both manual inspections and advanced technological tools to ensure optimal performance and compliance. Air-tightness testing, conducted using calibrated fan pressurisation methods, is mandatory for high-risk projects (Path C) and involves measuring the building’s air permeability to identify uncontrolled air leakage, which is crucial for maintaining energy efficiency and indoor air quality. Temperature and humidity sensors are utilised to monitor indoor environmental conditions, ensuring that the building’s internal climate remains within comfortable and healthy parameters. Energy monitoring systems, such as smart meters and sub-metering, track real-time energy consumption, providing data to assess the effectiveness of energy-saving measures and identify areas for improvement. Communally, these tools and techniques enable a comprehensive evaluation of retrofit interventions, ensuring they meet performance standards and contribute to the overarching goals of energy efficiency and sustainability.

Figure 10.

The multifaceted role and key competencies of a Retrofit Coordinator as mandated by the PAS 2035 framework. This schematic outlines the critical responsibilities throughout a retrofit project, including establishing client goals, conducting risk assessments, developing the retrofit plan, overseeing installation, and ensuring compliance. The coordinator acts as the central link between all stages of the project, ensuring a holistic, whole-house approach that mitigates risks related to moisture, TB, and indoor air quality, thereby guaranteeing the long-term performance and safety of the retrofit. The figure explains the following (a) responsibilities of a retrofit coordinator, (b) air tightness testing, (c) air permeability measurement, (d) temperature and humidity testing.

PAS 2035 provides a structured framework for domestic retrofit in the UK, ensuring quality, risk management, and consistent delivery of energy performance improvements. The standard mandates project oversight through the role of a Retrofit Coordinator, who manages multi-disciplinary teams and ensures that interventions align with whole-house strategies. Risk assessment is integral, identifying hazards related to moisture, structural integrity, and TB to prevent retrofit failure and protect occupant health. Compliance with design and installation standards is enforced through adherence to approved specifications, materials selection, and installation best practices, while testing and verification including air-tightness testing, thermography, and system commissioning confirms that retrofits meet performance targets. Lastly, documentation and record keeping are required to provide a comprehensive audit trail of decisions, interventions, and monitoring outcomes, supporting accountability and enabling lessons learned to inform future projects. Together, these components create a rigorous, evidence-based approach that ensures retrofits are effective, safe, and aligned with the UK’s Net Zero objective.

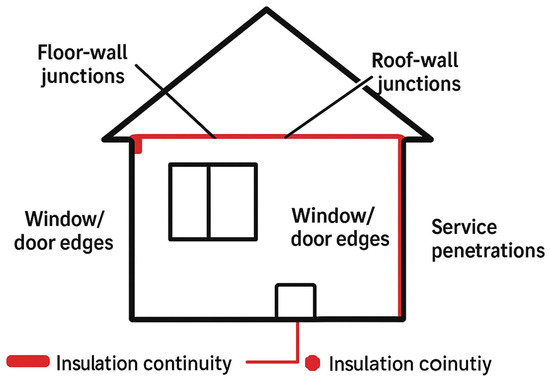

11. TB

TB is one of the most critical challenges in domestic retrofit (landscape, especially in older, solid-wall dwellings and complex geometries), directly impacting energy efficiency, occupant comfort, and the long-term durability of building fabric. The interruption of a continuous insulation layer by structural elements (concrete floor slabs or internal partition walls) creates high-conductivity pathways that drastically increase localised heat flux, which can account for up to 30% of total fabric heat loss in poorly addressed deep retrofits. A thermal bridge occurs where a discontinuity in insulation allows heat to bypass the thermal envelope, resulting in localised heat loss. Inadequately addressed thermal bridges can create cold spots, increase energy consumption, and promote condensation and mould growth. Effective thermal bridge mitigation is therefore non-negotiable for achieving high-performance standards, requiring detailed junction analysis and the use of dedicated structural or continuous insulating materials to minimise the linear thermal transmittance [78,79]. Thermal bridges are areas of a building envelope where the resistance to heat flow is lower than the surrounding insulated surfaces. They commonly occur at

- Junctions

- Openings

- Structural Elements

The impact of TB is twofold: increased heat loss and localised cold surfaces, which can result in condensation. Even a small thermal bridge can significantly reduce the overall performance of well-insulated walls or roofs, undermining energy savings and comfort. Development of innovative thermal breaks, using advanced thermal insulation and structural materials, is a top priority [80].

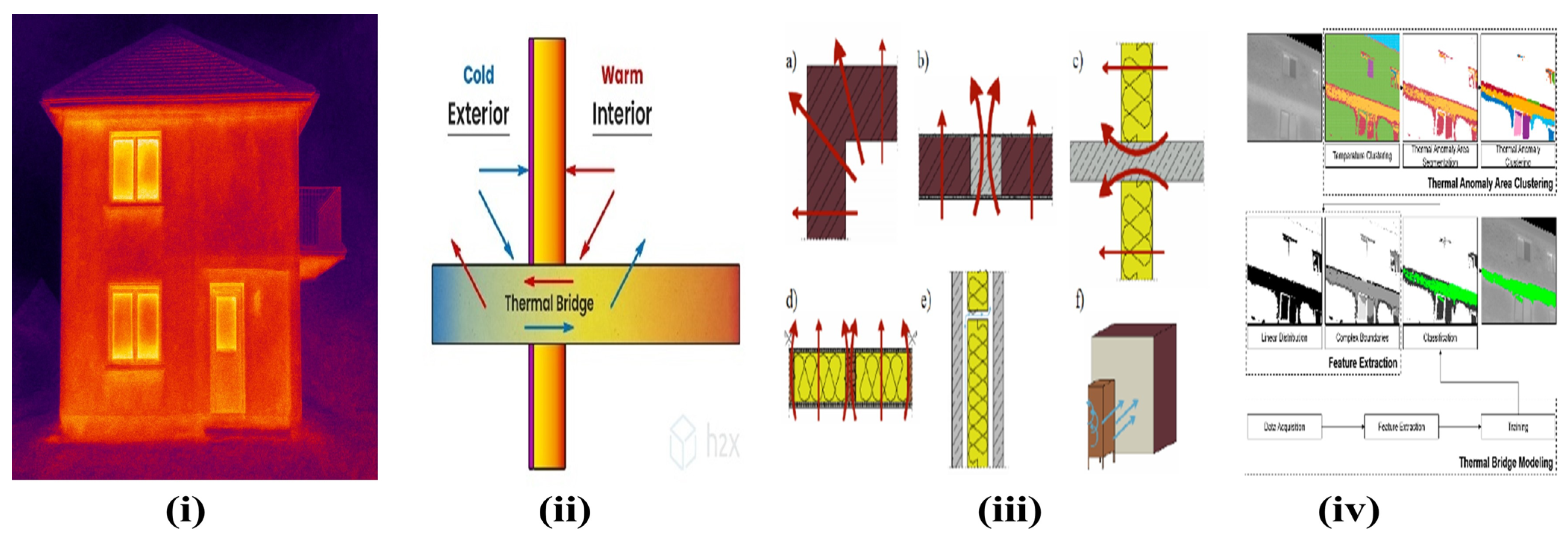

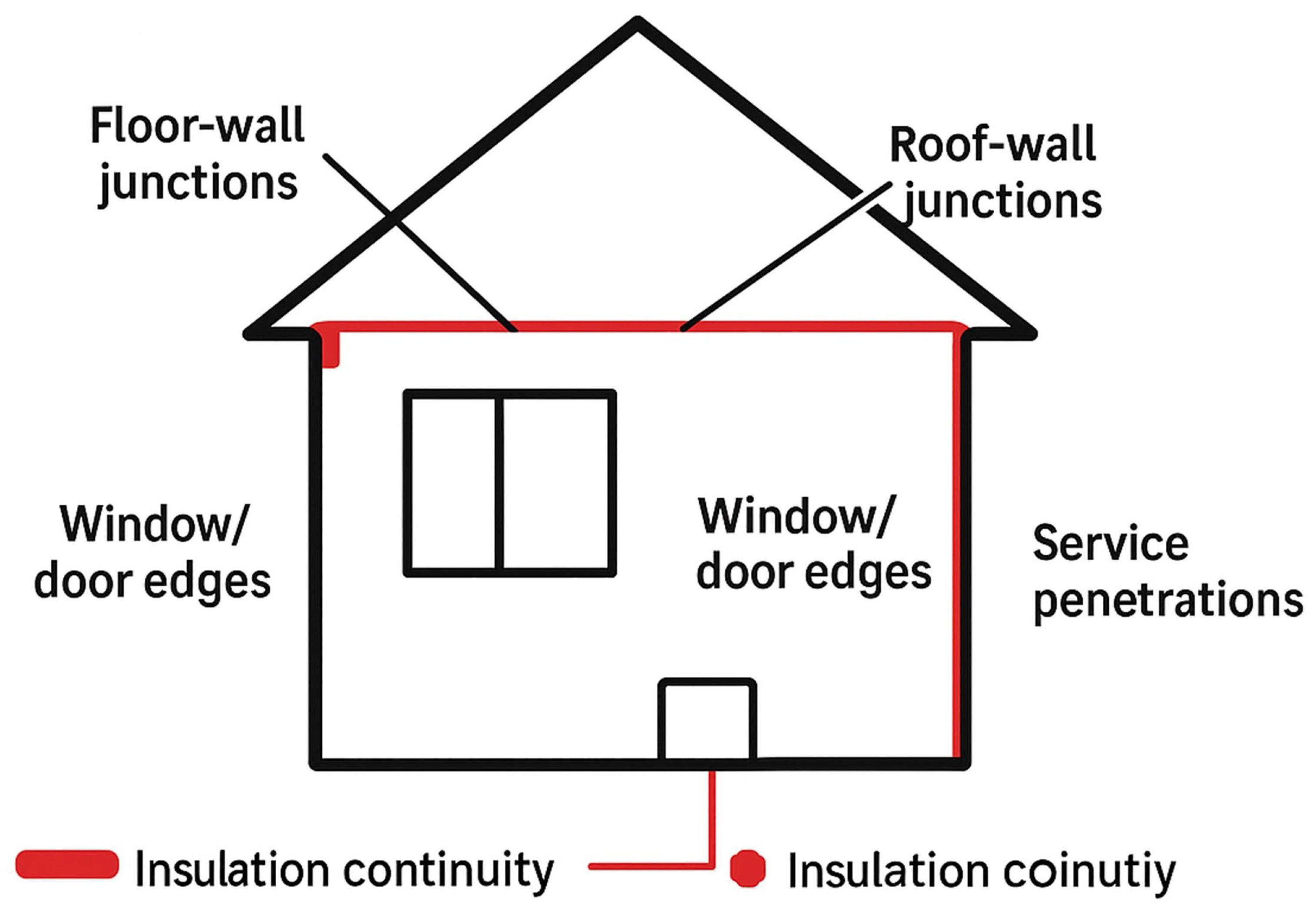

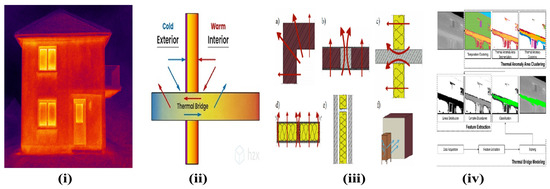

Accurate identification of thermal bridges is essential before retrofit work begins to ensure effective energy efficiency improvements. Techniques such as design and construction review involve analysing architectural and structural plans to identify potential TB points based on material properties and building geometry. On-site inspection allows for the detection of visible anomalies like gaps or discontinuities in insulation that could lead to thermal bridges. Thermography, or infrared thermal imaging, is widely used for thermal bridge detection due to its ability to identify temperature variations that indicate thermal anomalies with high spatial resolution. This technique is particularly effective in detecting linear thermal bridges, such as those at window reveals or junctions between walls and floors. For instance, a study demonstrated the use of aerial thermographic images to assess thermal bridges in urban buildings, highlighting the importance of capturing thermal anomalies from various angles to ensure comprehensive detection. Simulation and modelling complement these methods by providing quantitative analysis of heat flow through building components. Dynamic simulations can improve the accuracy of heat loss predictions, who found that detailed dynamic modelling of 2D thermal bridges improved heat loss accuracy by 5–7% compared to steady-state simulations. By integrating these techniques, a comprehensive assessment of thermal bridges can be achieved, informing targeted retrofit strategies that enhance building performance and occupant comfort. Figure 11 illustrates a critical consideration in building retrofit, i.e., the identification and remediation of a thermal bridge. A thermal bridge is a localised area in the building envelope where heat transfer is significantly higher than in the surrounding materials, often leading to heat loss, cold spots, and potential condensation and mould growth. The diagram depicts a common scenario where a cold-water pipe penetrates the interior wall, creating a path for heat to escape from the warm interior to the cold exterior. The sequence from (Figure 11i–iv) conceptually represents the retrofit process. It begins with the identification of the bridge followed by the application of appropriate insulation or a thermal break to encapsulate or isolate the conductive element. The final state represents the mitigated condition, where the continuity of the thermal barrier is restored, thereby improving the overall thermal performance of the building, enhancing occupant comfort, and reducing energy consumption. The location of thermal bridge is systematically presented in Figure 12.

Figure 11.

Sequential identification and mitigation of a thermal bridge caused by a penetrating cold-water pipe. The diagram illustrates a common retrofit challenge, (i) a cold-water pipe creates a conductive path through the insulated wall, acting as a significant thermal bridge and leading to heat loss and potential condensation. The mitigation process involves (ii,iii) the application of appropriate insulation or a thermal break to encapsulate the pipe. The final state (iv) shows the resolved condition, where the continuity of the thermal barrier is restored, thereby reducing heat loss, preventing condensation, and improving the overall energy efficiency of the building envelope.

Figure 12.

Thermal bridge locations.

Unmitigated thermal bridges can have significant adverse effects on the performance, durability, and comfort of domestic buildings. Energy loss occurs as heat bypasses insulation at junctions, penetrations, and structural discontinuities, reducing overall energy efficiency and increasing heating demand. Moreover, localised cold spots created by thermal bridges can cause condensation and mould growth, which not only compromise indoor air quality but also pose health risks to occupants. These cold areas also contribute to reduced thermal comfort, as uneven indoor temperatures can create drafts and cold surfaces despite central heating systems. Over time, repeated condensation cycles and moisture accumulation can accelerate structural degradation, particularly in masonry and timber elements, potentially leading to material decay, corrosion, or spalling.