Abstract

Nature-Based Solutions (NBSs) have proven to be effective and reliable for climate change adaptation and risk reduction. Among these, Floating Treatment Wetlands (FTWs) have recently gained significant attention. FTWs are floating NBS systems that enhance the biological self-cleaning capacity of aquatic environments. Since the performance of FTWs is derived from the rhizosphere suspended beneath a buoyant frame and the interactions between biofilm and macrophytes (rhizosphere), it is crucial to operate and design FTWs in a way that supports the specific pollutant removal pathways of FTWs. Key parameters to consider are plant selection, choice of planting medium, length of plant establishment phase, treatment medium depth, surface coverage ratio, hydraulic retention time (HRT), and placement of FTWs. Despite recent advances, there is a lack of established guidelines for FTW development, which has led to diverse construction and operational practices. This review aims to collate the latest advances in FTW research, identify gaps, and suggest a coherent classification and construction framework. By highlighting best practices, performance factors, and operational parameters, this review seeks to guide the future development and implementation of FTWs.

1. Introduction

The deterioration in the quality of freshwater resources restricts the extent to which they can be used. At the same time, reports indicate that the EU will lose 50% of its water resources by 2050 [1]. The ongoing decline in water quality, which is already restricting use—especially in high-demand sectors—will further intensify biosphere water stress [1].

Therefore, it is essential to implement solutions that will improve the quality of water resources and their quantity in order to mitigate the effects of water stress and the potential impact of global warming. Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) are reported to be an effective and reliable fit-for-purpose treatment solution for climate change adaptation and risk reduction [2].

One type of NBS that has recently attracted significant attention is Floating Treatment Wetlands (FTWs). FTWs are floating systems designed to enhance the biological self-cleaning capacity of aquatic environments [3,4,5,6]. The core components of FTWs are the planting medium and the plants themselves. A diverse range of macrophyte plants can be employed, resulting in a variety of possible applications. These include, but are not limited to, the treatment of stormwater and wastewater, the removal of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs), the treatment of agricultural and urban runoff, the treatment of industrial wastewater, the restoration of eutrophic ponds, the restoration of urban inland waters, and the reduction in algal blooms [3,5,6,7].

The treatment mechanism of these systems is based on the uptake of pollutants by plants in their rhizosphere, which develops beneath a buoyant frame. The rhizosphere acts as a biological filter and a net, slowing down the flow of the treatment medium and promoting sedimentation [3,4,5,6].

Of particular importance for the efficiency of the treatment process is the development of a biofilm/rhizosphere symbiosis. This results in the formation of a thin layer of microorganisms, collectively known as a biofilm, which supports the bioaccumulation process by increasing the biologically active surface area of the rhizosphere. The biofilm itself also accumulates pollutants as the layer of microorganisms grows and propagates within the treatment medium column [3,4,5,6].

The principal benefits of such systems include their relatively low operating and installation costs, as well as the minimal land requirements [3,4,5,6,7]. For example, the maintenance and construction costs of wastewater stabilization ponds and constructed wetlands range from 11.8 EUR/PE/year to 33.3 EUR/PE/year (PE—population equivalent) [8]. In the case of FTWs (with surface coverage ratios above 5%), maintenance and construction costs range from 3.67 EUR/m2/year for basic solutions to 137.22 EUR/m2/year for advanced systems [9].

Given these factors, FTWs are a viable option for direct or indirect nature restoration and global climate change mitigation efforts. Despite growing interest, classification of these systems remains unclear, as evidenced by the plethora of nomenclature employed in the literature on the subject. Similarly, there is a considerable diversity in the construction and dimensions of these solutions, given the absence of established guidelines for their development.

The review aims to synthesize recent developments in FTW research, identify existing gaps in research and application, and propose a coherent classification and design framework to support further development of these systems. By outlining best practises, key performance indicators, and operational considerations, this review provides a foundation for the optimized and sustainable implementation of FTWs in ecological applications and water management.

2. Classification

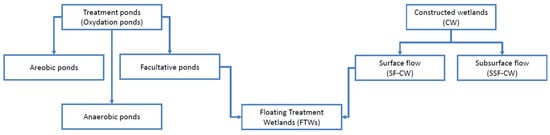

The concept of implementing floating systems to improve the ecological status and water quality of water bodies originated from naturally occurring floating islands [10,11]. FTWs create space for emergent macrophytes on ponds on their buoyant frame, combining the properties of both ponds and constructed wetlands [10]. Therefore, Floating Treatment Wetlands integrate the treatment properties of ponds and Surface Flow Constructed Wetlands (SF-CWs) while offering relatively low implementation and operating costs (Figure 1) [10,12]. FTWs can be further classified according to their construction, planted macrophytes, planting medium, or subsequent modifications (hybrid solutions).

Figure 1.

Floating Treatment Wetlands classification.

It is important to note that the classification of FTW systems is not always clear, and there is a wide variety of nomenclature associated with them.

Additionally, several NBSs are similar to FTWs but have structural and functional differences that exclude them from being considered FTWs. For example, free-floating macrophyte systems are based on the growth of small, free-floating plants on the surface of ponds, which grow freely on the surface without a fixed mat or any means of restricting plant growth to a selected area [13]. This creates operational problems, such as secondary pollution from dead plants after the vegetation season, displacement of plants by wind, or washing out of plants during high-flow conditions.

Hydroponic solutions are systems focused primarily on growing plants (e.g., for food) using irrigation water with high nutrient concentrations instead of soil. Treated wastewater can be used instead of prepared irrigation water to utilize nutrients present in the treated wastewater. In hydroponic systems, plants are often grown without any planting medium, directly in nets covering channels with irrigation medium, and in closed buildings under controlled conditions. Hydroponic solutions focus primarily on plant growth rather than on pollutant removal [12]. Therefore, free-floating macrophyte systems and hydroponic systems should not be considered as falling under the category of FTWs [10,12].

2.1. Floating Treatment Wetlands (FTWs) Nomenclature

The use of FTWs for treating diverse media remains a relatively recent innovation, as evidenced by the absence of established design guidelines to date. This results in a great variety of different construction solutions and a similar variety of nomenclature of those systems in the literature.

The nomenclature used in this article has been most frequently reported in the literature [4,10,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Other terminology reported in the literature includes the following:

- Free surface constructed wetlands (FSCWs) [21];

- Constructed floating wetlands [4,22,23,24];

- Floating wetland islands [25,26];

- Hydroponic root mats [4];

- Artificial floating islands [4,27];

- Natural floating wetlands [4];

- Ecological floating beds [4,5];

- Artificial floating ecosystems (AFESs) [28].

The use of inconsistent nomenclature can lead to unnecessary confusion, particularly among those without specialized knowledge in this field. FTWs often resemble hydroponic systems or the use of free-floating macrophytes for water treatment, which increases the risk of misclassification—especially when they are referred to by various alternative terms in the literature. The term “Floating Treatment Wetlands” has been proposed as the most accurate and appropriate nomenclature for these systems due to their characteristics [10], a view that the authors fully support. Standardizing this terminology will help avoid ambiguity and promote the coherent development of FTW technologies.

2.2. Applications

In the 20th century, FTWs were originally used for bird habitats and fish spawning areas. In the 1980s, the first applications of FTWs emerged for the treatment of stormwater and the remediation of polluted ponds [10,11,29]. In the 1990s, FTW applications were introduced in Japan, China, the USA, and other regions of Europe as a solution for the remediation of polluted urban rivers, lakes, and reservoirs and for ecological improvement. They can be seen as an integral part of large-scale engineering projects aimed at improving the quality of inland waters, enhancing biodiversity, or reducing the intensity of eutrophication [10,29].

The application of FTWs has enabled the remediation of polluted landscapes with low implementation and operational costs (as passive systems) compared to physical and chemical methods of remediation of polluted waters [4,29].

In the early 2000s, various applications of FTWs emerged with equally varied success, including wastewater treatment, mine drainage, livestock effluent, and industrial wastewater treatment [10].

To date, various applications of FTWs have been reported in the literature, including the following:

- Remediation of eutrophicated waters (e.g., [32]);

- Raw wastewater treatment (e.g., [4,14,20]);

- Post-treatment of urban wastewater effluent with a combination of other NBS solutions (e.g., [15,25]);

- Antibiotics removal (e.g., [16,28]);

- Treatment of petroleum hydrocarbons (e.g., [19]);

- Textile effluent treatment (dye decolorization) (e.g., [34]);

- Fish farming effluent treatment (e.g., [35]);

- Bioremediation of oil spills (hydrocarbon-contaminated water) (e.g., [19,36]).

The use of FTWs in stormwater and agricultural runoff treatment, environmental enrichment, eutrophication remediation, or wastewater treatment has been tested under full-scale conditions in Australia, the UK, China, Sweden, the USA, Brazil, Germany, and Spain [7,22,24,25,27,30,33]. However, few studies have conducted long-term studies, which is crucial to our understanding of the long-term performance of FTWs in specific climatic conditions and with corresponding macrophyte species. For example, San Miguel et al. [24] described the performance of FTWs operating from 2019 to 2022, with applications for the treatment of a river contaminated by livestock and agricultural runoff in Spain (Table 1). In the first 2 years of operation, the performance of FTWs based on nitrogen removal was 94.9% and 92.8%, respectively. In the following year, the performance decreased to 65.9%. The authors attribute the lower uptake capacity after the second year of operation to the stabilization of the submerged fraction of the FTW (rhizosphere–biofilm matrix).

Table 1.

Summary of FTW design considerations.

A study conducted by Rocha et al. [30] in Brazil lasted nearly 6 months, with FTWs deployed in a small pond environment. The maximum surface coverage ratio achieved was 10%. The authors observed reductions in turbidity, conductivity, and dissolved solids fractions. In the initial 3 months of the study, total nitrogen (TN) removal was limited and unstable. During the remaining 3 months, ammonia reduction was observed; however, the authors did not report the percentage of removed ammonia nitrogen or TN. Total phosphorus (TP) removal followed the same trend as TN in the initial 3 months; orthophosphates were reduced by 39.1% during the 2 summer months.

Hanna et al. [37] performed a study that lasted 16 months. The experiments were conducted in four parallel lagoons, built downstream of an existing agri-food tertiary treatment lagoon. Each lagoon had a capacity of 6.5 m3 and depth of 1 m. The treatment medium was fed semi-continuously from feeding tanks. Experiments were conducted with a surface coverage of 24%, 48%, and 72% and with an HRT of 16 and 8 days. The 24% coverage had a mean TN removal efficiency of 56 ± 9%, 48% coverage a had mean TN removal efficiency of 55 ± 16%, and 72% coverage had 55 ± 13%. The 72% coverage variant showed the highest difference in removal performance in comparison to the control, with up to 55% greater removal (on average 13%). The 16-day HRT showed up to 56% TN removal efficiency; under the 8-day HRT, 40% TN removal was achieved.

Other studies focused on short-term performance: Chen et al. [27] evaluated FTWs as part of a surface flow stormwater treatment system (SF-CW) in Ohio, USA (Table 1). The experiment lasted 104 days. Boynukisa et al. [33] applied FTWs for heavy metal removal in stormwater treatment in Sweden. Conducted over 84 days, the study demonstrated effective removal of cadmium (Cd), copper (Cu), lead (Pb), and zinc (Zn) (Table 1). Li et al. [25] examined FTWs applied as the third stage of a domestic wastewater treatment plant in an eco-park in China. Although the testing period was limited to one month, the authors reported a positive influence of FTWs on effluent quality.

On a much larger scale, experiments have been carried out under laboratory conditions, including novel implementations of FTWs for the treatment of petroleum hydrocarbons and the removal of antibiotics.

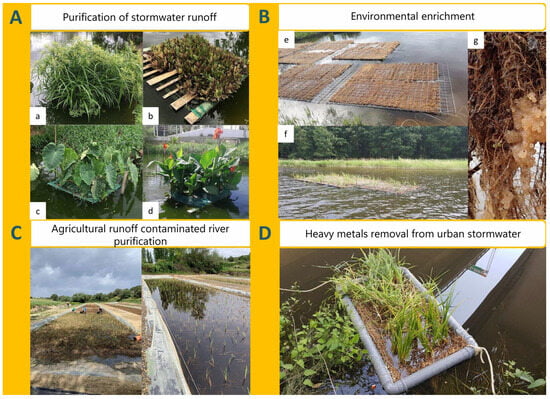

Figure 2.

Examples of Floating Treatment Wetlands. (A) Purification of stormwater runoff [30]; (B) Environmental enrichment [31]; (C) Agricultural runoff contaminated river purification [24]; (D) Heavy metals removal from urban stormwater [33]; (a) Cyperus papyrus; (b) Tradescantia pallida; (c) Xanthosoma sagittifolium; (d) Canna x generalis; (e) Buoyant frame before planting the plants; (f) Working FTW; (g) Roots of plants with the eggs of roach.

3. Design and Performance Factors

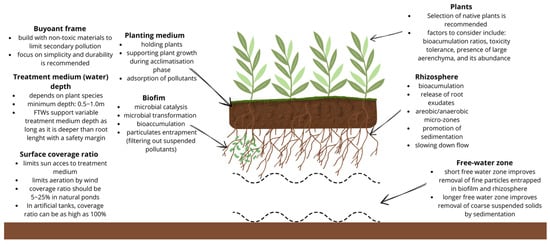

In the subsections of this chapter, key aspects of FTW design are outlined, with implications for FTW performance subsequently discussed, followed by the relevant design decisions. The main design considerations and performance factors are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Summary of design and performance factors for Floating Treatment Wetlands.

As the performance of FTWs is derived from the rhizosphere suspended under a buoyant frame and the interactions of biofilm/macrophytes, it is crucial to start design considerations from the available water depth [10,38]. Recognizing depth variability in the desired location for FTW deployment may prove helpful when considering macrophyte species suitable for local conditions, as the rooting depth limits the minimum depth for FTW deployment [5,10]. Design considerations for the buoyant frame should focus on the long-term durability and sustainability of the system while maintaining aesthetic values [22,39]. The shape of the system has not been reported to influence the efficiency of FTWs [10]; thus, simplicity is recommended. Surface coverage ratio has a major influence on FTW performance and treatment characteristics, as surface coverage affects dissolved oxygen concentrations, redox potential, access to sunlight, and overall planting density [5,10].

The placement of FTWs should maximize contact of the FTWs with the treatment medium, thus limiting short-circuiting of the treatment medium. FTWs designated for canals and rivers should be applied across the width of the canal; spacing between FTW units can increase removal efficiency in canal and river applications [40]; FTWs designated for the treatment of highly specific treatment mediums, which can be easily collected (i.e., hospital and industrial wastewater, airport runoff), should be applied with use of a balancing tank connected to several tanks with FTWs. FTWs deployed on ponds should be installed across the width of the pond in several lines, offset from each other. If that is not possible, FTWs can be installed in several clusters in random positions [40].

International efforts have been made with regard to developing guidelines. Batista et al. [41] discuss advanced computational modelling, sustainable materials, and community involvement as a key to scaling FTW use globally. Kumar et al. [42] emphasize that FTWs require careful design, standardized monitoring protocols, and regular maintenance to ensure long-term operation.

3.1. Buoyant Frame and Buoyancy

The buoyant frame is the base of FTW construction, maintaining its shape, containing the growth of macrophytes, supporting the planting medium, and ensuring the buoyancy of the structure during the adaptation period of the plants [10]. Therefore, it is important to carefully select materials based on the planned treated medium and local conditions to ensure sustainability of FTWs in the long-term [10,38]. Materials used to construct the buoyant frame should be durable, able to float on the treated medium, and must not lead to the degradation of the existing environment or its aesthetic value when FTWs are installed in public spaces [22,39].

Integral buoyancy of FTWs can be achieved by using various available buoyant materials (e.g., synthetic foams, bamboo, sealed PP or PVC pipes, recycled bottles, polystyrene, and cork) [5,10,23]. FTWs, like naturally occurring floating islands, can achieve self-buoyancy by entrapping methane produced by the anaerobic metabolism of organic deposits and by creating “air pockets” in the rhizosphere [5,10]. The occurrence of these two processes varies depending on plant species, age, growth stage, temperature, and microbial activity [5,10]. Due to the deterioration of the FTW frame and the overall structure that provides artificial buoyancy over time, self-buoyancy becomes an important aspect in the long-term operation of FTW solutions.

The use of natural materials, such as bamboo and wooden pallets, in FTW construction has been reported to provide adequate buoyancy, offering a sustainable alternative to synthetic components [20,30]. However, the use of natural materials may pose durability issues, as the decay of organic components can compromise the structural integrity of FTWs [30]. Nevertheless, other studies have reported FTWs constructed with natural materials that remained buoyant for the intended operational period [20,43,44]. It is recommended to combine natural construction frames with artificial buoyant structures to allow for the establishment of self-buoyancy after a few years of operation. Synthetic materials such as PVC, PP, or HDPE pipes and frames, plastic nets, and stainless steel frames or nets combined with natural or synthetic filling have been used in several studies and commercial applications [5,22,23]. Recent design solutions and their applications are summarized in Table 1.

It is worth considering shapes that can be easily interconnected to streamline anchoring or maintenance. Anchoring is recommended to limit the displacement of installed FTWs, and the use of simple solutions can limit its influence on the hydraulic retention time (HRT) of FTWs. Anchoring should take into account variability in the treatment medium’s depth to prevent damage to the structure [42].

Aesthetic considerations regarding shape should be taken into account whenever FTWs are installed in public spaces. It has been reported that FTWs are met with positive emotions from citizens, especially when installations are connected with citizen engagement and education [22,39].

3.2. Planting Medium

The primary function of the planting medium is to support plant growth and development over time. When selecting an appropriate medium, several factors should be considered, including its potential impact on the treatment medium (e.g., risk of secondary pollution), its influence on microbial diversity (e.g., provision of organic matter or a porous structure conductive to microbial colonization), its biodegradability, and its absorptive capacity.

Varius materials can be chosen as a planting medium depending on their availability in specific regions. For example, Samal et al. [5] reported the use of coarse peat, soil, coconut fiber, bamboo, compost, charcoal, rice straw, vermiculite, or pumice in a number of articles. Bi et al. [4] reported the use of bamboo fiber, wood, and coconut coir. The use of materials with a high surface area and high biodegradability can have a positive effect on the efficiency of pollutant removal rates by providing additional areas for biofilm growth and organic material for microbes to thrive on [4,5,45]. Another desirable effect that can be achieved with planting medium is the adsorption of pollutants from the treated medium (e.g., pumice, perlite, coarse peat, or zeolite) [4]. Examples of recently used planting media are collected in Table 1.

3.3. Plant Selection and Establishment Phase

Selected plants should be characterized by the presence of large aerenchyma or air-filled cavities in their roots and rhizomes, which increase the potential for buoyancy, as in naturally occurring floating islands [5,10,46]. When selecting macrophytes, the factor of bioaccumulation ratios and tolerance to increased toxicity should be considered [5,19]. Due to the risk of spreading invasive species, it is crucial to use native plant species [5,19]. Table 2 lists specific macrophyte species along with their applications and locations.

Table 2.

Reported macrophytes in various locations and applications.

The most commonly cited plant species in applications of FTWs are from the genera Canna, Carex, Cyperus, Juncus, Phragmites, Lollium, and Typha [4,5,10]. For applications of FTWs in urban or public spaces in general (e.g., stormwater treatment, restoration of eutrophicated waters), the aesthetic values of selected plants should be considered, as aesthetic values are reported to be important to citizens [10,22].

The establishment phase of plants requires special attention from FTW operators [10]. Plants grown from seeds or seedlings should be planted in a separate nursery section to allow them to establish properly under local conditions [10]. Developed, healthy plants should be placed in the FTW planting medium for the establishment phase. The establishment phase for plants will vary depending on the local climate, plant species, plant age, and treated medium. A more fertile medium may be used to replace the intended treated medium for the establishing phase.

The plant establishment phase reported by the researchers varied from 14 days to 3 months (Table 1). The plant establishment phase is essential for the performance of FTWs, during which time the rhizosphere and the biofilm on its surface can develop. Nevertheless, in studies carried out under natural conditions, the plant establishment phase was carried out outside the FTWs [23,24,27,33], and plant plugs were conditioned/acclimatized to local conditions and then replanted on the FTWs. The described approach yielded good results despite the absence of a developed rhizosphere under the floating frame. According to [27], macrophytes should be planted in mid-to-late spring.

3.4. Biofilm and Rhizosphere

Biofilm is a complex, diverse community of bacteria, fungi, and algae held together by an extracellular polymeric substance [4,5,19,26]. Biofilm formation in rhizosphere matrices is of great importance, as many pollutants can only or mainly be transformed by microbial catalysis [26,46]. Biofilm is reported to have higher catabolic rates, greater taxonomic diversity, greater catabolic range, and grater resilience towards disturbances than bacterial communities in open water [4,5,27]. The microbial community in the rhizosphere of plants includes heterotrophic and autotrophic denitrifiers (AOBs and HAOBs), archaea (AOA), and phosphate-accumulating organisms (PAOs) [26,32,47], the presence and taxonomic composition of which affect the performance of FTWs.

As biofilm is essential for sufficient performance of FTWs, researchers have performed experiments using synthetic fibrous biofilm carriers (inert), achieving a greater specific surface (3000–7000 m2/m3) [48,49] than the specific area of plant roots (7–114 m2/m3) [46,50].

However, biofilm formed on synthetic (or inert) biofilm carriers is less effective despite a larger specific area due to a lack of support from the plant rhizosphere or a lack of easily biodegradable biomass for microbial life to thrive on [4,32].

Another approach is emerging, with recent research by [32,51] highlighting the use of biodegradable biofilm carriers. Biodegradable carriers have shown improved performance in biological denitrification and phosphate removal by phosphate-accumulating organisms (PAOs) [32,51].

Nandy et al. [32] used rice straw as a biofilm carrier with a reported surface area of 145 m2/m3; taxonomic profiling showed that the use of biodegradable carriers had a positive effect on microbial population and biodiversity. Peng et al. [47] used inert biofilm carriers, which showed increased abundance of AOBs, HAOBs, and AOAs while having no effect on the abundance of PAOs. Planting media in FTWs can perform the function of biofilm carriers, depending on their construction solution [45,47]. Recent studies proposed the application of biochar as a biocarrier due to its high specific surface area; furthermore, the adsorption properties of biochar can support growth of macrophytes and FTW removal ratios [26,52].

Biofilm carriers can be used for bioaugmentation of the microbial population to achieve higher nutrient removal rates or to remove specific pollutants (e.g., hydrocarbons, antibiotics, heavy metals) [19,34,36,47,52,53].

3.5. Treatment Medium Depth

The required depth of the treated medium depends mainly on the macrophyte species; other factors include treatment purpose, inflow variations, and type of treated medium [10,46]. Low depth and leaving a short free-water zone (0.1–0.3 m) between the rhizosphere and the sediments can be more effective in removing fine particles and dissolved pollutants. Creating a longer free-water zone (0.5–2.0 m) is more suitable for treatment media with a high content of coarse suspended solids removed by sedimentation [46]. Reported root lengths vary from 17 cm to even 266 cm [10,53,54,55]. Root length is reported to increase as an adaptation to low nutrient concentrations [40,54]. High nutrients loads and phytotoxicity can limit root length [55].

FTWs can operate under fluctuations in the depth of the treatment medium; however, the growth of some plants can be adversely affected by changes in the depth of the treatment medium. Macrophyte genera such as Typha, Scirpus, and Juncus and species such as P. australis and Phalaris arundinacea show a high degree of morphological adaptation to changes in treatment medium depth [46]. Longer and denser root systems are expected to improve performance [40].

The depth required for FTWs depends on the selection of macrophyte species, especially in natural conditions where depth can only be partially controlled. The selection of macrophyte species (Table 2) can be made according to the expected length of the roots, so that it is adapted to the depth. Taking this into account, the authors recommend that the minimum depth to be maintained in FTW treatment is 0.5–1.0 m.

3.6. Surface Coverage Ratio

The surface coverage ratio influences the light penetration of the treated medium column, the redox potential, and the dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration [5,46]. The effect on light penetration is the most significant; FTWs with dense vegetation restrict sunlight from reaching the treated medium and limit the growth of photosynthetic algal species (mainly green algae). Research has shown that eutrophicated water passing through an FTW buoyant frame will limit the population of photosynthetic algae, as the overall velocity of passing treatment medium will be relatively slow [10]. Algal cells entering the submerged zone beneath the buoyant structure can be retained by the rhizosphere and associated biofilm, whose adhesive properties facilitate entrapment. The limited light availability in this zone restricts photosynthetic activity, ultimately resulting in cell death [46]. DO concentrations in reservoirs are regulated mainly by oxygen production by green algae during the day and aeration by wind action; FTWs influence DO concentrations mainly by limiting green algae growth and by limiting wind contact with the treated medium. The rhizosphere suspended in the treated medium releases oxygen to the surrounding environment, creating local aerobic conditions. However, oxygen secreted by plants is depleted by aerobic microbial populations or by aerobic decomposition of organic matter. Several researchers reported that the DO concentration under FTWs with high coverage ratio rapidly decreased to zero and did not increase thereafter [5,10].

High (>50%) coverage can facilitate anoxic conditions and thus limit anaerobic processes (e.g., oxidation, nitrification). Although DO concentrations in the surrounding water decrease, oxygen is still available in certain zones of the rhizosphere [5,46]. A high coverage ratio can be advantageous for application in treated media with high concentrations of nitrogen and phosphates [37].

Interestingly, ref. [56] reported a significant increase in DO concentrations, ranging from 15% to 67%, after the deployment of FTWs creating a barrier (just after the pond inlet zone). The authors attributed this increase to the selected plant, Cyperus papyrus.

Coverage is related to performance, and increasing coverage usually improves the overall performance of the system; however, some researchers have reported decreased performance with coverage above 50% [5,10,35,46]. Hanna et al. [37] reported increased plant bioaccumulation rates with a surface coverage of 72%.

In applications of FTWs in natural water bodies, a coverage ratio in the range of 5–25% can provide an adequate effect [5,53], while a coverage ratio above 50% can have a negative impact on the pond biotope. In the application of FTWs in artificial tanks or ponds for wastewater treatment, the coverage ratio of the surface can be in the range of 50–100% [5,53].

3.7. Hydraulic Retention Time (HRT)

The HRT describes the contact time of FTWs with the treated medium and should therefore be one of the key aspects of FTW performance. HRTs ranged from 4.7 days to 48 days in different studies (Table 1). HRTs reported in other review papers range from 2.1 h, 1–3 days, 22–49 days, or even 540 days [53]. While a lower HRT may increase the volume of treated media, it may also result in unsatisfactory treatment performance. Therefore, future operators of FTW systems should optimize the HRT to achieve satisfactory contaminant removal rates while maintaining cost efficiency.

However, as reported in several studies, changing the HRT from 14–25 days to 5–10 days did not result in significant changes in pollutant removal [53]. Ref. [56] recommended a minimum HRT of 5 days for FTW treatment, which is consistent with other researchers’ reported HRT-related performance.

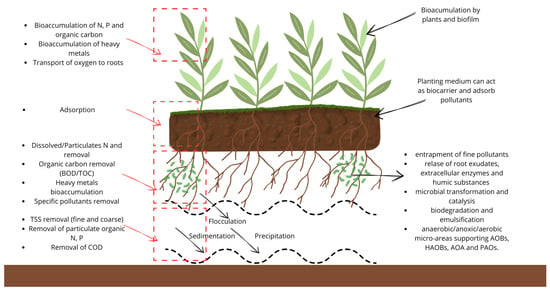

4. Pollutant Removal Mechanisms

Pollutant removal pathways of FTWs are related directly to biofilm–rhizosphere interface and treatment medium depth. The macrophyte species, HRT, and surface coverage ratio influence further pollutant removal. Key pollutant removal pathways include the release of root exudates, extracellular enzymes, and humic substances, development of biofilm (bioaccumulation), and promotion of flocculation of particulate matter at the surface of the rhizosphere/biofilm interface [10,56]. Other important processes include uptake of nutrients and metals by plants, formation of anaerobic zones in the rhizosphere [38] and surrounding water column, promotion of sedimentation, and binding of pollutants in sediments [10]. Table 3 presents the overall removal performance of specific pollutants by FTWs. Figure 4 presents a graphical summary of pollutant removal mechanisms.

Table 3.

Overall removal performance of various pollutants by Floating Treatment Wetlands, where each “+” displays 25% removal performance.

Figure 4.

Summary of pollutants removal mechanisms.

The most important pathways for removal of suspended solids and particulate pollutants (organic nitrogen and phosphorus, suspended solids, BOD, COD) by FTWs include promotion of flocculation, entrapment of particulates in the rhizosphere, and promotion of sedimentation [10,26,54]. The fate of selected suspended solids in the treated medium depends on the size of the pollutants, the flow velocity (HRT), and the available surface area of the rhizosphere. For example, a specific root surface area of 15 m2 could harbour 0.3 kg/m2 of suspended solids [46]. Organic compounds suspended in the treated medium can be immobilized in the rhizosphere, settling on roots and on the surface of the biofilm cover [35,46]. Immobilized organic pollutants are then degraded thanks to the activity of enzymes from the root system or by aerobic/anaerobic decomposition [19,26,56], allowing for bioaccumulation or uptake by the biofilm and macrophytes [19,26]. Pollutants that are not trapped by the rhizosphere can be subjected to reduced-flow conditions enforced by the plant rhizosphere as it creates good conditions for sedimentation of pollutants. As suspended pollutants flow through the rhizosphere, they slow down and settle to the bottom of the pond or tank, creating a layer of sediment, which leads to a reduction in the concentration of pollutants in the effluent [10,46,54]. The fate of pollutants deposited in sediments is not permanent. However, FTWs limit sediment resuspension by limiting the influence of wind action and by promoting laminar flow conditions in the open water layer between the FTW rhizosphere and sediments [46]. In most applications, sediments in the vicinity of FTWs can be easily dredged due to the mobility of FTWs. The flux of nutrients and heavy metals from sediments has been widely reported and thus creates a major operational issue for FTWs. Under aerobic conditions, organic pollutants (and bioaccumulated in organics heavy metals) are decomposed and reintroduced to the treatment medium [57]. Under anaerobic/anoxic (reducing) redox conditions, organic pollutants are decomposed through methanogenic processes. Furthermore, phosphates under these conditions may be mobilized from insoluble iron, aluminium, or calcium compounds or clay, leading to an internal load higher than the external load in warmer seasons [57,58].

The fate of biogenic pollutants (nitrogen, phosphorus, and organics) in FTWs is mostly related to the presence of AOBs, HAOBs, AOAs, and PAOs in the rhizosphere–biofilm interface. Anaerobic/anoxic/aerobic micro-areas developing in the rhizosphere by DO root secretion support both nitrifiers and denitrifiers [26,38]. Microbial population abundance and taxonomic diversity are further supported by root exudates [26,32,47]. Removal of nitrogen and organic carbon in the rhizosphere is carried out mostly by ammonification, denitrification, nitrification, and the presence of extracellular enzymes [26,47,56]. Products of microbial transformation can be bioaccumulated by both macrophytes and microbes, creating positive feedback, further increasing removal performance.

Phosphorus can be removed in FTWs mainly by precipitation, sedimentation, and bioaccumulation [38,56]. The presence of PAOs in low-oxygen conditions and the presence of anoxic/aerobic micro-areas allow for a reduction in phosphates by microbial dephosphatation [26,32,47].

The predominant nutrient removal mechanism in FTWs varies depending on the plant species used and local conditions. Phosphorus and nitrogen uptake by plants varies greatly between plant species, including differences in nutrient uptake by roots and shoots [38,54].

The performance of FTWs decreases during colder seasons due to reduced biological activity [4,37,47,59]. To some extent, the decrease in performance can be mitigated by using native macrophyte species or by extending the HRT, as in the case with other NBSs. However, a reduction in treatment efficiency should be expected, as nature has its limitations [37]. At temperatures below 15 °C, a shift from biological processes to physical should begin to occur, as microbial processes rapidly slow down at this temperature [37].

Removal of heavy metals from the treated medium with FWTs occurs mainly by bioaccumulation [17,33]. In waters with elevated levels of heavy metals, heavy metals are primarily accumulated in the rhizosphere as a means of mitigating shoot stress, whereas in environments with lower levels of heavy metals, this disproportion in less pronounced [17,33].

The rhizosphere and shoot biomass have an effect on the efficiency of heavy metal and nutrient removal, with root biomass having a greater effect as the rhizosphere is in contact with the treated medium [33,54]. High nutrient concentrations in the treatment medium can have a negative impact on heavy metal removal performance [17,54].

Hydrocarbon removal by FTWs is based on the rhizosphere–biofilm interface, with bioaugmentation of hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria [19,36]. The primary processes shaping hydrocarbon removal include microbial degradation, phytovolatilization, phytostabilization, phytoaccumulation, metabolic transformation, mineralization, and phytoextraction [19,36]. As in the case of nutrient removal, plants promote the growth of bacteria (biofilm) on the surface of the rhizosphere; the bacteria release surfactants that allow for the emulsification of hydrocarbons, which can be bioaccumulated by the bacteria and decomposed by enzymatic reactions within the bacteria [19,36]. Recent studies have reported promising results for the removal of hydrocarbons by FTWs, showing the removal of 70–95% of hydrocarbons [19,36]. The removal of specific pollutants by FTWs can be problematic due to increased toxicity, resulting in reduced plant growth. The use of specific bacterial strains can limit the toxicity of hydrocarbons, and similar results have been reported for the removal of antibiotics [36,52].

The removal of antibiotics using microbial bioaugmentation of antibiotic-degrading bacteria has shown promising results. Up to 97% (HRT 20d) removal of amoxicillin was achieved [52]. The primary pathway for antibiotic removal is through symbiosis between antibiotic-degrading bacteria (biodegradation) and macrophytes, and the authors indicate that the abundance of bacteria increases with the availability of nutrients [52]. The removal and degradation of dyes from industrial wastewater have been reported to follow a similar pathway to the removal of antibiotics. Bioaugmentation of specific bacteria yielded outstanding results in the degradation of dyes from various treatment media, achieving removal rates of up to 90–100% (HRT 3d) [34].

5. Conclusions and a Principal Design Criterion for FTWs

Floating Treatment Wetlands (FTWs) have the potential to offer an effective and sustainable solution for the removal of pollutants. However, there is still a knowledge gap regarding the long-term operation of FTWs in natural conditions in Central Europe, as well as the removal of various emerging pollutants. A further issue is the lack of clear guidelines and norms regarding the construction and operation of FTWs. As a result, each FTW is constructed based on the engineering knowledge and construction solutions reported by other authors, leading to a significant variety in construction solutions that also vary in removal performance. In the absence of clear guidelines for FTW construction, the authors have collected the best practices and operational parameters from previous FTW implementations with a view to facilitating further development of FTW solutions and the creation of clear guidelines:

- The design of FTWs should focus on creating durable, simple, and easy-to-maintain constructions. Durable and sustainable materials are essential. Common options include synthetic foams, bamboo, PVC/HDPE pipes, and recycled materials. Self-buoyant vegetation or materials like cork or sealed pipes should be taken into consideration as well as long-term stability and resistance to degradation.

- The planting medium should be selected from biodegradable materials to enhance pollutant removal (e.g., coconut fiber, pumice, biochar). Clean, non-toxic planting media should be selected to avoid secondary pollution.

- Selected plants should be characterized by the presence of large aerenchyma or air-filled cavities in their roots and rhizomes. Bioaccumulation ratios, tolerance to increased toxicity, and native occurrence in the ecosystem of selected plants should also be considered. Plants should be acclimatized to local conditions (including elevated nutrient concentrations and toxicity); this can be achieved by gradually increasing concentrations of treated medium. Plant plugs should be grown in a nursery so that the grown plants can be planted in FTWs. Macrophytes should be sufficiently grown during the deployment of FTWs so that the young plants will not be damaged by wind or animals.

- The depth of the treatment medium and the surface coverage ratio have an immense influence on the removal performance of FTWs. The depth should be considered along with the length of the plant root system to maintain a safe margin between sediments and roots. A short free-water zone (0.1–0.3 m) can be more effective in removing fine particles and dissolved pollutants, while a longer free-water zone is more suitable for a treatment medium with a high content of coarse suspended solids removed by sedimentation. The surface coverage ratio influences the light penetration of the treated medium column, the redox potential, the dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration, and the pollutant removal performance. A surface coverage ratio in the range of 5–25% can provide an adequate effect; however, higher coverage will increase the performance of FTWs. A surface coverage ratio ≥50% can create adverse effects under natural conditions by creating anaerobic conditions that would endanger the local biotope and reduce overall removal performance. Special consideration should be given to the selection of plant species, treatment medium depth, and surface coverage ratio.

- The HRT should be optimized between 5–14 days to balance treatment efficiency. A shorter HRT (less than 5 days) may suffice for initial removal processes, but extending it can improve outcomes for complex pollutants.

- Maximizing contact with the treatment medium should be considered to avoid short-circuiting. In canals and rivers, FTWs should be spread across the width to optimize flow conditions.

Other important design considerations are listed below:

- The performance of FTWs in long-term operation is highest in the first year of operation, with a gradual decline in performance in subsequent years. Performance can be restored by replanting plants and dredging sediments.

- Plants should be harvested regularly to enable higher rates of bioaccumulation and to prevent the sinking of biomass into sediments. The harvested biomass has potential for composting, anaerobic digestion, or pyrolysis, making it suitable for a circular economy approach in specific scenarios [37].

- During the acclimatization phase of FTWs, frequent monitoring is required (ranging from weekly checks to once a month depending on the location) to observe the growth of plant plugs and to check whether they have been eaten by birds or otherwise damaged. At the later stage, monitoring can be limited to harvesting the biomass.

- Pretreatment (at least mechanical treatment) should be considered if FTWs are planned to treat wastewater.

- FTW performance is expected to be lower in colder seasons due to reduced biological activity and nitrification/denitrification rates. Similar to the operation of wastewater stabilization ponds, BOD/COD loading rates should be limited during the cold season to maintain desired effluent concentrations. Another approach may be to increase the HRT time.

- The shape of FTWs does not affect performance; however, it can affect durability, planting density, maintenance, cost-effectiveness, and aesthetics.

Despite recent advancements, there are currently no design guidelines for planting density, the loading rates per unit surface area, and the removal rates of specific plants. Further studies should be undertaken with FTW development guidelines in mind.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.; methodology, S.K.; formal analysis, S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.; writing—review and editing, K.P.; visualization, S.K.; supervision, K.P.; funding acquisition, K.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC/BPC is financed by Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NBS | Nature-based Solutions |

| FTW | Floating Treatment Wetland |

| PPCPs | Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products |

| SF-CWs | Surface Flow Constructed Wetlands |

| CW | Constructed Wetlands |

| FSCWs | Free Surface Constructed Wetlands |

| AFES | Artificial Floating Ecosystem |

| TN | Total Nitrogen |

| TP | Total Phosphorus |

| HRT | Hydraulic Retention Time |

| DO | Dissolved Oxygen |

| BOD | Biochemical Oxygen Demand |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| TSS | Total Suspended Solids |

| PAOs | Phosphate Accumulating Organisms |

| AOBs | Ammonia-Oxidizing Bacteria |

| HAOBs | Heterotrophic Ammonia-Oxidizing Bacteria |

| AOAs | Ammonia-Oxidizing Archaea |

| LECA | Lightweight Expanded Clay Aggregate |

| EVA | Ethylene–Vinyl Acetate |

| PE | Population Equivalent |

References

- EEA. Europe’s Nature; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. Nature-Based Solutions in Europe: Policy, Knowledge and Practice for Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, N.; Yeh, P.; Chang, Y.-H. Artificial floating islands for environmental improvement. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, R.; Zhou, C.; Jia, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, P.; Reichwaldt, E.S.; Liu, W. Giving waterbodies the treatment they need: A critical review of the application of constructed floating wetlands. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 238, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, K.; Kar, S.; Trivedi, S. Ecological floating bed (EFB) for decontamination of polluted water bodies: Design, mechanism and performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 251, 109550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.; Li, X.; Lu, X. Recent developments and applications of floating treatment wetlands for treating different source waters: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 62061–62084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucke, T.; Walker, C.; Beecham, S. Experimental designs of field-based constructed floating wetland studies: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 660, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mburu, N.; Tebitendwa, S.M.; van Bruggen, J.J.; Rousseau, D.P.; Lens, P.N. Performance comparison and economics analysis of waste stabilization ponds and horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetlands treating domestic wastewater: A case study of the Juja sewage treatment works. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 128, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, J.; Walker, C.; Page, D.; Arslan, M.; White, S.A.; Lucke, T.; Beecham, S.; Winston, R.J.; Strosnider, W.H.J.; Nicodemus, P.; et al. Assessing the Costs of Constructed Floating Wetlands for the Treatment of Surface Waters and Wastewater. ACS ES&T Water 2025, 5, 4737–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headley, T.R.; Tanner, C.C. Constructed wetlands with floating emergent macrophytes: An innovative stormwater treatment technology. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 42, 2261–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeger, S. Schwimmkampen. J. Soil Water Conserv. 1988, 43, 304–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, K.; Tondera, K.; Rizzo, A.; Andrews, L.; Pucher, B.; Istenič, D.; Karres, N.; Mcdonald, R. Nature-Based Solutions for Wastewater Treatment: A Series of Factsheets and Case Studies; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sayanthan, S.; Abu Hasan, H.; Abdullah, S.R.S. Floating Aquatic Macrophytes in Wastewater Treatment: Toward a Circular Economy. Water 2024, 16, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, L.H.; Arenzon, A.; Molle, N.D.; Rigotti, J.A.; Borges, A.C.A.; Machado, N.R.; Rodrigues, L.H.R. Floating treatment wetland for nutrient removal and acute ecotoxicity improvement of untreated urban wastewater. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 18, 3697–3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colares, G.S.; Dell’oSbel, N.; Paranhos, G.; Cerentini, P.; Oliveira, G.A.; Silveira, E.; Rodrigues, L.R.; Soares, J.; Lutterbeck, C.A.; Rodriguez, A.L.; et al. Hybrid constructed wetlands integrated with microbial fuel cells and reactive bed filter for wastewater treatment and bioelectricity generation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 22223–22236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, M.; Zhang, D.; Niu, X.; Ma, J.; Lin, Z.; Fu, M. Insights into the fate of antibiotics in constructed wetland systems: Removal performance and mechanisms. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 321, 116028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuruzzaman, M.; Anwar, A.F.; Sarukkalige, R. Metal Removal Kinetics, Bio-Accumulation and Plant Response to Nutrient Availability in Floating Treatment Wetland for Stormwater Treatment. Water 2022, 14, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mufarrege, M.d.L.M.; Di Luca, G.A.; Carreras, Á.A.; Hadad, H.R.; Maine, M.A.; Campagnoli, M.A.; Nocetti, E. Response of Typha domingensis Pers. in floating wetlands systems for the treatment of water polluted with phosphorus and nitrogen. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 50582–50592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mfarrej, M.F.B.; Wang, X.; Fahid, M.; Saleem, M.H.; Alatawi, A.; Ali, S.; Shabir, G.; Zafar, R.; Afzal, M.; Fahad, S. Floating Treatment Wetlands (FTWs) is an Innovative Approach for the Remediation of Petroleum Hydrocarbons-Contaminated Water. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 1402–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arivukkarasu, D.; Sathyanathan, R. Phytoremediation of domestic sewage using a floating wetland and assessing the pollutant removal effectiveness of four terrestrial plant species. H2Open J. 2023, 6, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allami, M.H.M.; Whelan, M.J.; Boom, A.; Harper, D.M. Ammonia removal in free-surface constructed wetlands employing synthetic floating Islands. Baghdad Sci. J. 2021, 18, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karstens, S.; Dorow, M.; Bochert, R.; Stybel, N.; Schernewski, G.; Mühl, M. Stepping Stones Along Urban Coastlines—Improving Habitat Connectivity for Aquatic Fauna with Constructed Floating Wetlands. Wetlands 2022, 42, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karstens, S.; Langer, M.; Nyunoya, H.; Čaraitė, I.; Stybel, N.; Razinkovas-Baziukas, A.; Bochert, R. Constructed floating wetlands made of natural materials as habitats in eutrophicated coastal lagoons in the Southern Baltic Sea. J. Coast. Conserv. 2021, 25, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, G.S.; Martín-Girela, I.; Ruiz, D.; Rocha, G.; Curt, M.D.; Aguado, P.L.; Fernández, J. Environmental and economic assessment of a floating constructed wetland to rehabilitate eutrophicated waterways. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 884, 163817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Jin, Y.; Huang, Y. Water quality improvement performance of two urban constructed water quality treatment wetland engineering landscaping in Hangzhou, China. Water Sci. Technol. 2022, 85, 1454–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Zhong, M.; Lin, B.; Zhang, Q. Roles of Floating Islands in Aqueous Environment Remediation: Water Purification and Urban Aesthetics. Water 2023, 15, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Costa, O.S. Nutrient Sequestration by Two Aquatic Macrophytes on Artificial Floating Islands in a Constructed Wetland. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, J.; Cui, J.; Li, D.; Huang, L. Membrane combined with artificial floating ecosystems for the removal of antibiotics and antibiotic-resistance genes from urban rivers. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Ni, F. Review of Ecological Floating Bed Restoration in Polluted Water. J. Water Resour. Prot. 2013, 5, 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, E.G.; Feitosa, P.H.C.; Coura, M.d.A.; Barbosa, D.L. Temporal and spatial trends of a floating islands system’s efficiency. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 277, 111367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Moraes, K.R.; Souza, A.T.; Muška, M.; Hladík, M.; Čtvrtlíková, M.; Draštík, V.; Kolařík, T.; Kučerová, A.; Krolová, M.; Sajdlová, Z.; et al. Artificial floating islands: A promising tool to support juvenile fish in lacustrine systems. Hydrobiologia 2023, 850, 1969–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandy, S.; Kalra, D.; Kapley, A. Designing efficient floating bed options for the treatment of eutrophic water. AQUA—Water Infrastruct. Ecosyst. Soc. 2022, 71, 1332–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boynukisa, E.; Schück, M.; Greger, M. Differences in Metal Accumulation from Stormwater by Three Plant Species Growing in Floating Treatment Wetlands in a Cold Climate. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahreen, S.; Mukhtar, H. Development of Bacterial Augmented Floating Treatment Wetlands System (FTWs) for Eco-Friendly Degradation of Malachite Green Dye in Water. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osti, J.A.S.; Carmo, C.F.D.; Cerqueira, M.A.S.; Giamas, M.T.D.; Peixoto, A.C.; Vaz-Dos-Santos, A.M.; Mercante, C.T.J. Nitrogen and phosphorus removal from fish farming effluents using artificial floating islands colonized by Eichhornia crassipes. Aquac. Rep. 2020, 17, 100324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahid, M.; Arslan, M.; Shabir, G.; Younus, S.; Yasmeen, T.; Rizwan, M.; Siddique, K.; Ahmad, S.R.; Tahseen, R.; Iqbal, S.; et al. Phragmites australis in combination with hydrocarbons degrading bacteria is a suitable option for remediation of diesel-contaminated water in floating wetlands. Chemosphere 2020, 240, 124890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, R.A.; Borne, K.E.; Andrès, Y.; Gerente, C. Effect of floating treatment wetland coverage ratio and operating parameters on nitrogen removal: Toward design optimization. Water Sci. Technol. 2024, 89, 1466–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, L.J.; Messer, T.L.; Mittelstet, A.R.; Comfort, S.D. A biological and chemical approach to restoring water quality: A case study in an urban eutrophic pond. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 318, 115463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falfán, I.; Lascurain-Rangel, M.; Sánchez-Galván, G.; Olguín, E.J.; Hernández-Huerta, A.; Covarrubias-Báez, M. Visitors’ Perception Regarding Floating Treatment Wetlands in an Urban Green Space: Functionality and Emotional Values. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, T.N.; Walker, C.; Janzen, J.G.; Nepf, H. Flow distribution and mass removal in floating treatment wetlands arranged in series and spanning the channel width. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2022, 44, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, G.d.S.; Rocha, E.G.; de Lacerda, M.C.; Filho, M.N.M.B.; Calheiros, C.S.C. Applications of floating treatment wetlands for remediation of rainwater and polluted waters: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 33, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Singh, B.; Chen, Y.; Kafle, A.; Zhu, W.; Ray, R.L.; Kumar, S.; Shan, X.; Balan, V. The Bioremediation of Nutrients and Heavy Metals in Watersheds: The Role of Floating Treatment Wetlands. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billore, S.K.; Prashant; Sharma, J.K. Treatment performance of artificial floating reed beds in an experimental mesocosm to improve the water quality of river Kshipra. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 2851–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Xi, S.; Yang, X.; Yang, W.; Li, J.; Gu, B.; He, Z. Purifying eutrophic river waters with integrated floating island systems. Ecol. Eng. 2012, 40, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, M.I.; Espenberg, M.; Hauber, M.M.; Kasak, K.; Hylander, S. Application of Floating Beds Constructed with Woodchips for Nitrate Removal and Plant Growth in Wetlands. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Cuervo, D.P.; Müller, J.A.; Wiessner, A.; Köser, H.; Vymazal, J.; Kästner, M.; Kuschk, P. Hydroponic root mats for wastewater treatment—A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 15911–15928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.-X.; Niu, N.-Q.; Li, T.-M.; Yu, L.-J.; Gu, L.-K.; Liu, M.-H. Research on the Purification Performance of a Floating Island System Treating the Effluent of WWTP Under Different Seasons. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Chu, S. A novel bamboo fiber biofilm carrier and its utilization in the upgrade of wastewater treatment plant. Desalination Water Treat. 2015, 56, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felföldi, T.; Jurecska, L.; Vajna, B.; Barkács, K.; Makk, J.; Cebe, G.; Szabó, A.; Záray, G.; Márialigeti, K. Texture and type of polymer fiber carrier determine bacterial colonization and biofilm properties in wastewater treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 264, 824–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, C.C.; Headley, T.R. Components of floating emergent macrophyte treatment wetlands influencing removal of stormwater pollutants. Ecol. Eng. 2011, 37, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Li, J.; Wu, H.; Yang, S.; You, Y.; Li, D.; Xing, W.; Zou, C.; Guo, X.; Li, J.; et al. Using rice straw-augmented ecological floating beds to enhance nitrogen removal in carbon-limited wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 402, 130785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, S.; Tahira, S.A.; Naqvi, S.N.H.; Tahseen, R.; Shabir, G.; Iqbal, S.; Afzal, M.; Amin, M.; Boopathy, R.; Mehmood, M.A. Improved remediation of amoxicillin-contaminated water by floating treatment wetlands intensified with biochar, nutrients, aeration, and antibiotic-degrading bacteria. Bioengineered 2023, 14, 2252207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colares, G.S.; Dell′OSbel, N.; Wiesel, P.G.; Oliveira, G.A.; Lemos, P.H.Z.; da Silva, F.P.; Lutterbeck, C.A.; Kist, L.T.; Machado, Ê.L. Floating treatment wetlands: A review and bibliometric analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 714, 136776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwammberger, P.F.; Lucke, T.; Walker, C.; Trueman, S.J. Nutrient uptake by constructed floating wetland plants during the construction phase of an urban residential development. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 677, 390–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barco, A.; Bona, S.; Borin, M. Plant species for floating treatment wetlands: A decade of experiments in North Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olguín, E.J.; Sánchez-Galván, G.; Melo, F.J.; Hernández, V.J.; González-Portela, R.E. Long-term assessment at field scale of Floating Treatment Wetlands for improvement of water quality and provision of ecosystem services in a eutrophic urban pond. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 584–585, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søndergaard, M. Redox Potential Definitions and General Aspects. Encycl. Inland Waters 2009, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondergaard, M.; Jensen, P.J.; Jeppesen, E. Retention and internal loading of phosphorus in shallow, eutrophic lakes. Sci. World J. 2001, 1, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhard, A. The Nitrogen Cycle: Processes, Players, and Human Impact. Nat. Educ. Knowl. 2010, 3, 25. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).