Abstract

China’s higher education system is the largest globally but faces significant spatial imbalance issues. While studies have examined the spatial distribution of universities, long-term dynamic analysis, quantitative exploration of influencing factors, and investigation of spatial heterogeneity are lacking. This study investigates the spatiotemporal evolution of China’s regular higher education institutions (HEIs) from 1952 to 2023 by using ArcGIS spatial analysis and integrating the Geographical Detector and Multi-scale Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR) models. Findings reveal that (1) the spatial distribution of China’s HEIs has become increasingly clustered, transitioning from a “point-like” to a “network-like” and finally to a “surface-like” pattern, with its center shifting southwestward—this evolution reflects the gradual formation of a spatially sustainable layout that adapts to regional development needs. (2) Multiple interacting factors influence distribution—including the number of full-time faculty, regional GDP, national universities’ presence during the Republic of China era, and fiscal expenditure on education—with significant variations in their explanatory power. Regional population size also exerts a notable influence. (3) The impact of these factors exhibits significant spatial heterogeneity, with pronounced local imbalances. Thus, multi-scale processes operating at different geographical levels have shaped HEIs’ spatial pattern and addressing this heterogeneity is a key prerequisite for achieving sustainable and equitable development of higher education. These findings provide critical insights for optimizing higher education resource allocation, promoting balanced regional development, and advancing the construction of a high-quality education system in China.

1. Introduction

China’s economy has transitioned from rapid growth to high-quality development, marking a pivotal phase of fiscal transformation and industrial upgradation. In this context, technological innovation has emerged as a core driver of national and regional development [1]. Higher education institutions (HEIs), as primary hubs of knowledge production, talent cultivation, and technological breakthroughs, not only underpin national innovation systems but also play a decisive role in narrowing regional development gaps and promoting balanced socioeconomic progress [2,3], a role that is indispensable for achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). The National Medium- and Long-Term Education Reform and Development Plan (2010–2020) explicitly emphasizes enhancing higher education quality, optimizing its structural and regional layout, and advancing equitable access to educational resources. Building on this, the 14th Five-Year Plan and the 2035 Vision Outline further advocate for constructing a diversified higher education system and improving the spatial allocation of higher education resources, reflecting the central government’s strategic focus on addressing regional disparities in higher education and fostering coordinated development of the sector.

Since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, China’s higher education sector has achieved remarkable leaps. By 2023, the total enrollment in higher education reached 47.63 million, with a gross enrollment rate of 60.2%, and the number of regular HEIs surged to 2820—making China’s higher education system the largest in the world [4,5,6]. However, beneath this quantitative expansion lies a persistent challenge: significant spatial imbalances in HEI distribution. For instance, the eastern coastal regions, represented by the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, the Yangtze River Delta, and the Pearl River Delta, concentrate a large proportion of high-quality HEIs, abundant educational resources, and superior research conditions. In contrast, the central and western regions, particularly remote areas such as the northwest and southwest, face shortages of HEIs, inadequate faculty strength, and limited access to high-quality educational opportunities. Such disparities not only hinder the realization of educational equity but also constrain the potential for technological innovation and socioeconomic development in less developed regions, creating a “Matthew effect” in regional development. Therefore, systematically analyzing the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of China’s regular HEIs and exploring the driving factors behind their spatial distribution is not only academically significant for understanding the laws of higher education spatial layout but also practically valuable for optimizing the allocation of higher education resources, promoting regional coordinated development, and advancing the construction of a high-quality education system.

Internationally, research on the spatial distribution of educational resources can be traced back to the 1950s. Early studies primarily focused on the economic dimensions of education. For example, Samuelson applied the theory of market failure to analyze the distribution of public service facilities, including educational institutions, around administrative centers, laying a theoretical foundation for understanding the spatial logic of public service provision [7]. Su highlighted the critical role of economic development in shaping the allocation of public funds across different educational stages, noting that economic prosperity directly determines the scale and efficiency of educational investment [8]. Meanwhile, S. Bowles adopted quantitative models to explore the multifaceted factors influencing the allocation of educational resources, pioneering empirical research in this field [9]. In recent decades, with the advancement of interdisciplinary research, scholars have shifted their focus to optimizing the allocation of higher education resources from the perspective of educational economics, exploring issues such as the efficiency of educational resource utilization and the equilibrium of resource distribution [10,11]. Additionally, the widespread application of geographic information system (GIS) technology has enabled researchers to conduct in-depth spatial analysis of educational facility distribution, visualizing spatial patterns and evolutionary trends and enriching the methodological system of related research [12,13].

In China, the rapid expansion of higher education since the 21st century has triggered extensive academic research on the spatial distribution of HEIs. Drawing on theories such as spatial layout, resource allocation, and new economic growth, Chinese scholars have conducted in-depth explorations into the spatial patterns [14], influencing factors [15], and socioeconomic impacts [16] of HEIs. Methodologically, research has evolved from traditional qualitative analysis [17] to a combination of mathematical modeling, GIS spatial analysis [18], and other quantitative methods, gradually improving the depth and accuracy of research. However, despite these achievements, existing studies still have obvious shortcomings. Firstly, most studies rely on cross-sectional data or short-term time series data, making it difficult to capture the long-term dynamic evolutionary characteristics of HEI distribution. As a result, the understanding of the historical evolution context and long-term development trends of China’s HEI spatial pattern remains insufficient. Secondly, although many studies have identified the influencing factors of HEI spatial distribution, most adopt global regression models that assume spatial homogeneity of influencing factors, failing to fully reveal the spatial heterogeneity of the effects of various factors. In other words, existing research cannot effectively explain why the same factor has different degrees of influence on HEI distribution in different regions. Finally, the selection of influencing factors in existing studies often focuses on a single dimension such as economy or population, lacking a comprehensive and systematic analytical framework that integrates multiple dimensions including history, policy, and society. This makes it difficult to fully grasp the complex driving mechanisms of HEI spatial distribution.

To address these research gaps, this study takes 2820 regular HEIs in China (excluding military academies and institutions in Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan) as the research object. It selects five key time nodes (1952, 1978, 2000, 2014, and 2023) that have witnessed major reforms and developments in China’s higher education sector. By integrating GIS spatial analysis methods (including nearest neighbor index, kernel density analysis, center of gravity shift, and standard deviation ellipse), this study systematically explores the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of China’s regular HEIs. Furthermore, it combines the Geographical Detector model and the Multi-scale Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR) model to quantitatively analyze the influencing factors of HEI spatial distribution and their spatial heterogeneity from both global and local perspectives. This study aims to systematically reveal the spatiotemporal evolution patterns of China’s regular higher education institutions from 1952 to 2023, identify the primary factors influencing their spatial distribution and spatial heterogeneity, and address gaps in existing research regarding long-term dynamic analysis, quantitative assessment, and spatial heterogeneity exploration. It provides practical references and scientific basis for optimizing the allocation of higher education resources, formulating policies related to building an education powerhouse, and promoting coordinated regional development. The research findings are expected to provide a scientific basis for optimizing the spatial allocation of China’s higher education resources, promoting balanced regional development of higher education, and offer valuable references for the formulation and adjustment of higher education policies.

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Processing

The list of HEIs in the People’s Republic of China—2820 institutions, including 1274 undergraduate colleges and universities and 1546 specialized colleges and universities (excluding military colleges and universities, Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, and other regions)—was obtained from the Ministry of Education (http://www.moe.gov.cn/). HEIs’ coordinates were obtained using the Baidu coordinate picking system (https://api.map.baidu.com/), and errors were corrected using GeoSharp. Administrative districts’ base map data were downloaded from the standard map service website of the State Bureau of Surveying, Mapping and Geographic Information Service (http://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn/; review number GS (2019) 1822); the base maps were not modified. Socioeconomic data were obtained from China’s Urban Statistical Yearbook 2023 and each province’s (city’s) national economic and social development statistical bulletin for that year.

2.2. Research Methodology

2.2.1. Nearest Neighbor Index

The Nearest Neighbor Index (NNI) constitutes a fundamental spatial statistical metric for assessing point-referenced geographical entities’ distribution patterns. This analytical method has been employed extensively to determine HEIs’ spatial agglomeration characteristics through quantitative measurement of their geographical dispersion [19] mathematically formulated as follows:

where R denotes the NNI; mindij is the Euclidean distance between any HEI in the region and its nearest neighboring HEI; n is the total number of HEIs; and A is the study’s geographical area. R > 1 indicates HEIs’ dispersed distribution, R < 1 indicates their clustered distribution, and R = 1 indicates their random distribution.

The study aims to determine whether the spatial distribution of Chinese universities from 1952 to 2023 exhibits clustering, randomness, or dispersion. The nearest neighbor index serves as a classic method for measuring the spatial distribution patterns of point elements. By calculating the ratio of Euclidean distances between a university and its nearest neighbor (R value), the distribution type can be directly determined, precisely addressing the core question of spatial distribution pattern evolution.

2.2.2. Kernel Density Analysis

Kernel density analysis estimates the density of point or line pattern based on moving cells that effectively depict HEIs’ agglomeration [20], with the following formula:

where f(x,y) is HEIs’ density estimation at spatial location (x,y), is the kernel function, di is HEIs’ distance at location (x,y) from the ith observation point, n is the number of sample points, and h is the bandwidth or smoothing parameter.

The determination of h (bandwidth) follows the principle of “matching the study scale + accommodating dynamic evolution characteristics + visual and logical rationality verification.” Given the national geographic scope (approximately 5200 km east–west and 5500 km north–south), h should be selected within the tens to hundreds of kilometers range. Determining h must ensure consistency across temporal cross-sections: i.e., the same or comparable h values must be used across all five years.

Research requires the intuitive visualization of core areas, diffusion pathways, and spatial disparities within university clusters. Kernel density analysis estimates point feature density through moving cells, generating continuous density surfaces that precisely identify high-value concentration centers and low-value sparse zones [21].

2.2.3. Center of Gravity Shift and Standard Deviation Ellipse

The center of gravity transfer model can summarize the spatial center of gravity change trajectory of geographic elements; therefore, with this model [22], this study analyzes HEIs’ center of gravity migration direction and distance, using the following formulas:

where X and Y denote the coordinates of HEIs’ center of gravity; Xi and Yi are the coordinates of each research unit; and Wi is the number of HEIs in the ith research unit.

The standard deviation ellipse can well express the distribution range and direction trend of geographic elements in the study area. This paper uses the ellipse to describe HEIs’ spatial distribution profile and dominant direction [23] with the following formulas:

where SDEx and SDEy represent the ellipse’s long and short axes; xi and yi represent the coordinates of college i; X and Y represent all HEIs’ average center; and n is the total number of HEIs.

Further research is needed to clarify the overall distribution pattern, extension direction, and spatial expansion extent of higher education institutions. The standard deviation ellipse, defined by its major axis (SDEx), minor axis (SDEy), and rotation angle (θ), can quantify the concentration range of distribution (increased ellipse area indicates expanded agglomeration scope), dominant direction, and typological differences.

2.2.4. Geographic Detector

The geographic detector reveals the degree to which influencing factors shape the spatial distribution of HEIs by exploring the relationship between variance and total variance within an attribute layer [24], using the following formula:

where q represents how well an influencing factor detects the spatial pattern of HEIs, the value interval is (0, 1), and a larger q-value indicates the factor’s stronger degree of influence. L is a variable’s stratification; Nh and N are the number of cells in layer h and the whole area, respectively; and and represent the variance of the Y value in layer h and the whole area, respectively. To align with the analytical requirements of the geographic detector, this study employs the natural breakpoint method for classifying population-scale variables, the equidistant grouping method for economic development variables and geographic spatial variables, and the quartile grouping method for policy environment variables.

The study must screen core drivers influencing the spatial distribution of higher education institutions from 10 candidate factors, including population, economy, policy, and history. Geographic detectors quantify each factor’s contribution to spatial differentiation in university distribution by calculating factor explanatory power q-values (ranging from 0 to 1, where higher q-values indicate stronger influence), thereby precisely identifying dominant factors.

2.2.5. Multi-Scale Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR)

To test and model spatial heterogeneity, Fotheringham et al. proposed the MGWR model, now widely used to study spatial non-stationarity [25,26] with the following formula:

where yi is the number of HEIs in city i; bwj is the bandwidth of the jth variable; (ui,vi) are the geographic coordinates of city i; Xij is the jth variable of city i; βbwj is the local regression coefficient of the jth variable; and εi is the error term.

The influencing factors of university distribution exhibit significant spatial variation. By spatially visualizing local regression coefficients, MGWR can intuitively reveal this non-stationarity, making it more aligned with the spatial heterogeneity inherent in geographic phenomena than traditional global regression methods.

2.3. Determination of the Study Period

In 1952, the Chinese government implemented large-scale restructuring in the faculty and departmental settings of HEIs across the country. In 1978, HEIs resumed the college entrance examination, aligning with the economic reform and opening-up in the country; around 2000, the expansion of universities and the merger of colleges and universities were implemented. Then, in 2014, the State Council issued the “Implementing Opinions on Deepening the Reform of Examination and Admission System,” which proposed gradually abolishing enrollment in and three admission batches of HEIs and establishing private colleges and universities on a large scale. Because these years mark significant steps in the development of China’s HEIs and have promoted the overall quality of higher education, this study selected 1952, 1978, 2000, 2014, and 2023 as its time nodes.

3. Results

3.1. Evolutionary Characteristics of General Colleges and Universities’ Spatial Distribution

3.1.1. Spatial Distribution Toward Clusters

In 1952, China’s HEIs underwent large-scale faculty restructuring, thus initiating the basic pattern of China’s higher education system. The number of general HEIs has since evolved through a systematic, diversified development trend from 201 in 1952 to 2820 in 2023—a significant growth trend that must be balanced with sustainable resource utilization to avoid redundant construction and inefficient allocation. Based on the data of Chinese general HEIs over five time periods from 1952 to 2023, the average NNI was calculated using ArcGIS10.8 software (Table 1). For each type of HEI, the NNI of undergraduate colleges and universities decreased slowly from 0.347 to 0.273, with an average annual decrease of 0.001 percentage points, while that of specialized colleges and universities steadily decreased from 0.380 to 0.258, with an average annual decrease of 0.001 percentage points. The NNI of overall HEIs decreased from 0.290 to 0.169, with an average annual decrease of 0.001 percentage points. Proximity indices of different types and universities as a whole are all less than 1 and show a fluctuating downward trend, with a p-value of less than 0.01 and a confidence level of 99%, indicating that Chinese HEIs’ distribution pattern is not only moving toward clustering but that this trend is gradually increasing-the clustering trend, when guided by rational planning, can promote resource sharing, reduce operational costs, and lay the foundation for a sustainable higher education agglomeration ecosystem.

Table 1.

Evolution of the nearest neighbor index of general colleges and universities in China.

3.1.2. Evolution of Spatial Distribution Density with a Spreading Trend

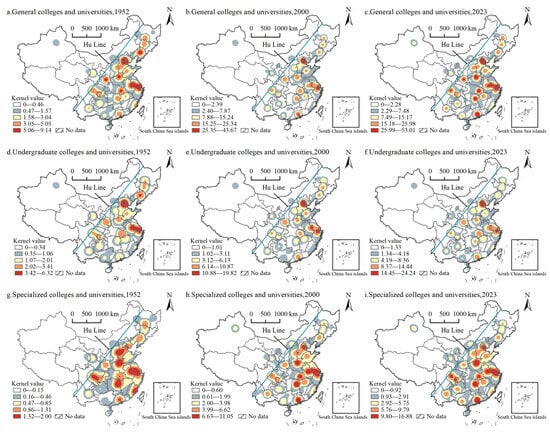

To reflect intuitively ordinary HEIs’ spatial agglomeration evolution, the kernel density estimation method was used to visually analyze the overall spatial distribution density and that of various HEI types during different time periods (Figure 1). In general, ordinary HEIs’ distribution is “dense in the southeast and sparse in the northwest” with the Hu Huanyong Line as the boundary. About 93% of ordinary HEIs are distributed to the right of the Hu Huanyong Line, and undergraduate and junior colleges account for about 94% and 92%, respectively. Ordinary HEIs’ overall spatial distribution pattern shows a “point-network-plane” evolution trend, and their scope of agglomeration is gradually expanding. In the early development stages, agglomeration was mainly point-like, but later, agglomeration began to coexist with the diffusion effect. Agglomeration centers are mainly located in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region around the Bohai Sea; the Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Shanghai Yangtze River Delta region; and the Hubei, Hunan, and Jiangxi Central Triangle region east of the Hu Huanyong Line. Not surprisingly, different types of HEIs exhibit differing spatial distribution and evolution characteristics. Specifically, (1) with the dual core of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei and Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Shanghai, undergraduate colleges radiate southwest to Shanxi, Shandong, Hubei, Hunan, and Jiangxi; they continue to extend southward to the intersection of Sichuan-Yunnan-Guizhou and the Pearl River Delta. (2) From the subgraphs of undergraduate colleges (Figure 1d–f), it can be seen that the high kernel value areas (representing high-density agglomeration) continued to expand from 1952 to 2023, and the number of secondary agglomeration centers increased significantly, showing a trend of multi-core development.

Figure 1.

“Point-Network-Surface” Evolution Spectrum of Kernel Density of Chinese Regular HEIs (1952–2023).

3.2. General Colleges and Universities’ Influencing Factors in Spatial Distribution

3.2.1. Influential Factors’ Selection and Description

General HEIs’ spatial distribution results from a combination of factors. Densely populated areas tend to have greater demand for higher education, and such regions’ population size and potential education demand are the basic conditions for HEIs’ layout. Economically developed regions can provide better financial support for education and scientific research, thus promoting HEIs’ distribution and development. As the macro-control and planning manager of HEIs’ construction and administration, the government plays an important role in regulating and supervising their distribution. Regions with long cultural history have accumulated rich educational resources, and HEIs’ early historical evolution has laid the foundation for later construction in various other locations [27]. Thus, this paper combines colleges and universities’ spatial differentiation characteristics and existing research results [14,27,28], comprehensively considers scientific, representative, and accessible indicators, and selects 10 independent variable indicators to construct an indicator system from the four dimensions of population size, socioeconomics, policy support, and historical background. Among these, population size is characterized by household population (X1). Socioeconomics is characterized by GDP (X2), GDP per capita (X3), financial expenditure for education (X4), the number of full-time instructors in HEIs (X5), the proportion of nonagricultural industries (X6), end-of-year highway mileage (X7), and the urbanization rate (X8). Policy support is characterized by mention of “colleges and universities” in the government’s annual work report (X8). Finally, historical background is characterized by the number of national universities in the Republic of China (X10). Data obtained for each indicator were categorized into five types according to the natural discontinuity method, so that they were converted from numerical to typological quantities.

3.2.2. Influence Factor Analysis Based on Geodetector

The text takes the number of general HEIs in cities of various grades and above as the detecting factor Y (dependent variable). Table 2 shows detected influencing factors; different factors significantly influence general HEIs’ spatial distribution, and their explanatory power’s magnitude varies. According to the q-value, influencing factors are divided into two levels; the top four of the 10 first-tier indicators (four dimensions) are the number of full-time instructors in HEIs (0.683) > GDP (0.495) > the number of national universities in the R.O.C. (0.433) > the financial expenditure on education (0.419). For general HEIs, economic development dominates spatial distribution; besides, the explanatory power of the number of full-time faculty and GDP ranked first and second, much higher than that of other influencing factors. In regions with higher levels of economic development, government and enterprises better support higher education by providing sufficient financial support for general HEIs, promoting educational quality, attracting more excellent teachers and students, and thus prompting general HEIs’ new construction and expansion [29]. In addition, general HEIs’ construction process is closely related to China’s historical process. In early modern times, the Qing government began to build new-style higher education, and as of 1948, 31 national universities had been built across the country (excepting Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan). National universities’ construction in the Republic of China laid an important foundation for New China’s subsequent development of higher education. In regions with better roots, higher education levels were always in the leading position, profoundly impacting the spatial distribution pattern of today’s general HEIs [23].

Table 2.

Geodetection results of factors influencing general colleges and universities’ spatial distribution in China.

In influencing factors’ second tier are household population (0.264) > urbanization rate (0.197) > proportion of nonagricultural industry (0.147) > GDP per capita (0.126) > policy support (0.079) > end-of-year road mileage (0.073), with q-values ranging from 0.073 to 0.264—relatively weak influence factors. Among these, population size and urbanization rate are the top two, respectively. This shows that general HEIs’ distribution is inseparable from the population’s support. The strong demand for education in densely populated areas attracts many general HEIs. For example, developed eastern coastal regions such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangdong have high population density and high demand for education, leading to more concentrated distribution of general HEIs. In the less populated areas of Xinjiang and Tibet, the number of general HEIs is relatively small, and educational resources are concentrated mainly in provincial capitals and other densely populated locations. At the same time, with the acceleration of urbanization, educational resources (e.g., instructors, funds, facilities) become gradually concentrated in cities, making the number of urban, general HEIs relatively superior in quantity and quality and promoting their further rapid development. Therefore, a combination of economic and demographic factors greatly influence China’s spatial distribution of general HEIs.

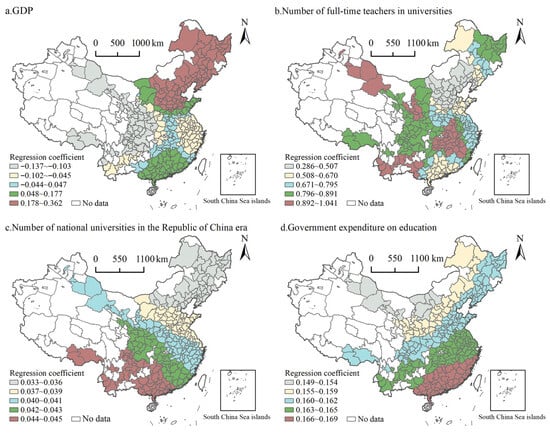

3.2.3. Influencing Factors’ Spatial Differentiation Based on MGWR

The further to explore influencing factors’ spatial differentiation characteristics of general HEIs’ distribution pattern, this paper uses the MGWR model, taking the number of general HEIs as the dependent variable, selecting influencing factors with the top four explanatory powers as independent variables, and, from a local perspective, exploring directional differences in the factors’ action and their action’s intensity. Compared with GWR, MGWR has the advantage of allowing the conditional relationship between the independent and dependent variables to vary across differing spatial scales, generating unique optimal bandwidths for each of them. Model results show that the Akaike information criterion AICc was 278.552 and that the adjusted R2 was 0.863, indicating good fit and reflecting the geoprobe results’ plausibility. At the geographic level unit, each influencing factor’s regression coefficients were counted to obtain the mean, standard deviation, minimum, median, and maximum; this shows that each influencing factor had fractional anisotropy on general HEIs’ spatial distribution. As Table 3 shows, the bandwidths of different variables vary substantially. In fact, the bandwidth of the number of full-time HEI instructors is the smallest, at 45, indicating that general HEIs’ distribution is more spatially varied with change in faculty. This is followed by GDP (bandwidth = 110), which reflects a relatively high degree of spatial heterogeneity. Educational expenditure and the number of Republican National Universities have a bandwidth of 290, suggesting that spatial heterogeneity is less significant. Each influencing factor’s effect has spatial non-stationarity, and each factor’s regression results are visualized and expressed through the natural break method (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of the MGWR model’s regression coefficients.

Figure 2.

Spatial Heterogeneity Distribution of MGWR Regression Coefficients of Core Driving Factors for Chinese Regular HEIs (2023).

- (1)

- The GDP regression coefficient is −0.137–0.362, in which 51.20% of the analyzed units positively correlated with HEIs’ distribution, and the difference between the maximum and minimum regression coefficients is 0.499, indicating a big difference in support for construction of general HEIs among various regional governments. As Figure 2a illustrates, regression coefficients are largest in the northeast, the mid-east, and the southeast, and they tend to decrease from the border of Henan and Shaanxi to the west. Economically developed regions are usually able to attract more resources and become regions of general HEI concentration, while more economically backward regions have limited resources, resulting in a smaller number of local general HEIs or a relatively low level of development.

The negative GDP regression coefficient essentially reflects a localized mismatch between the economic growth models of certain regions in central and western China and the development logic of higher education. This core discrepancy stems from the suppression of higher education demand by economic structures, disparities in fiscal resource allocation priorities, and the historical lock-in effects of university distribution patterns. This finding offers critical policy implications: optimizing university distribution in such regions cannot rely solely on economic growth drivers. Instead, it requires targeted educational policy support (such as increased central government transfer payments for university development), aligning industrial upgrading with university programs (e.g., guiding universities to establish majors tailored to regional industries), and other measures to resolve the mismatch between GDP growth and higher education development.

- (2)

- The regression coefficient of the number of full-time instructors in HEIs is 0.286–1.041, which is positively associated with the spatial distribution of general HEIs. As Figure 2b illustrates, the regression coefficient of the number of full-time instructors has significant spatial differentiation and prominent imbalance. In the northwestern Gansu and Xinjiang bordering areas, central Yunnan, Jiangxi, and its regional surrounding parts are characterized by distribution of the number of instructors at more general HEIs. In the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei and Pearl River Delta area, the remaining regression coefficients are less concentrated. Overall, construction of general HEIs in the central and western regions depends more on the number of full-time instructors.

- (3)

- Regression coefficients for the number of R.O.C. national universities range from 0.033 to 0.045, and the effects on general HEIs’ distribution are all positive in all units of analysis (3c). Overall, regression coefficients decrease in a gradient from southwest to northeast. Their fluctuation is small compared with other variables; the difference between maximum and minimum values is only 0.012, so the difference in spatial effect is weak. This indicates that the degree of reliance on historical schools in the construction of general HEIs in each region does not differ considerably. In fact, other factors exert a greater influence on the differences in general HEIs’ spatial distribution.

- (4)

- Educational expenditures’ regression coefficients are 0.149–0.169, with significant positive influence effects. The difference between their maximum and minimum values is 0.020, indicating little difference in spatial influence effects of educational expenditures on general HEIs’ distribution (3d). Overall, most regions are characterized by high educational expenditures and general HEIs’ wide distribution. Educational expenditures determine local government’s scale of investment in higher education, in turn directly impacting general HEIs’ conditions, infrastructure construction, and research funding.

4. Discussion

This study comprehensively explores the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics and influencing factors of China’s regular higher education institutions (HEIs) from 1952 to 2023 by integrating GIS spatial analysis, Geographical Detector, and Multi-scale Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR) models. The findings enrich the theoretical understanding of higher education spatial layout and provide practical implications for optimizing resource allocation, while also presenting limitations that require future attention.

The spatial distribution of China’s regular HEIs has evolved from point-based clustering to area-based diffusion over the past seven decades, with the core cluster belt extending from North China and East China to central and western core cities. Additionally, the “dense in the southeast and sparse in the northwest” distribution pattern bounded by the Hu Huanyong Line echoes Hong’s [14] research, and this study further verifies the stability of this pattern through long-time series data, supplementing evidence for the path dependence of higher education spatial layout.

In terms of research methods, this study addresses the limitation of existing research relying on cross-sectional data or short-term time series, as exemplified by Wei et al. [15]. By selecting five key time nodes covering major educational reforms, it systematically reveals the complete evolutionary process of the spatial pattern of regular HEIs, which aligns with the long-term dynamic analysis paradigm advocated by Kim and Park [21]. Moreover, combining Geographical Detector with MGWR models to quantitatively analyze spatial heterogeneity fills the gap of previous studies such as Guorui’s [29] that failed to deeply explore spatial differences in factor effects, and this approach is consistent with the analytical framework of Fotheringham et al. [25], the proposers of the MGWR model.

At the national macro-level, this study clarifies the coupling relationship between university distribution and regional development, similar to Haoran’s [16] emphasis on the role of higher education agglomeration in regional innovation. It further points out that the spatial layout of HEIs should adapt to regional development characteristics. The finding that historical factors (number of Republican-era national universities) have a sustained impact is consistent with Yichuan’s [27] research, highlighting the path dependence of higher education spatial layout on historical educational resources. Notably, this study expands the research scope to the national level and discovers the mismatch between economic growth and higher education development in some underdeveloped regions, complementing the research of Zhou et al. [29] on urban agglomerations.

This study also has limitations. It did not incorporate micro-level data at the prefecture-level city scale, and future research could refer to Tijs et al.’s [13] approach of using fine-grained data to refine the interpretation of spatial heterogeneity. Additionally, the lack of policy simulation models limits practical guidance, and future studies can draw on Ribeiro et al.’s [12] method to construct a GIS-based decision support tool. Ignoring factors such as natural geography and cultural traditions is another shortcoming, and expanding the indicator system with reference to Shuncheng et al.’s [17] multi-dimensional framework would make the analysis more comprehensive.

These findings offer important policy implications: continue supporting central and western higher education through fiscal transfers and faculty recruitment; leverage key HEIs to drive cluster development with reference to South Korea’s experience summarized by Kim and Park [21]; protect historical educational resources; and align HEI layout with regional economic needs. Future work should expand indicator systems, use panel data for dynamic analysis referring to Izadi et al.’s [11] method, deepen scale effect research with interdisciplinary theories, and explore HEI patterns at multiple spatial scales to provide targeted policy suggestions.

5. Conclusions

Among other methods, this paper uses GIS spatial analysis to explore characteristics of the spatial evolution pattern of ordinary universities in China from 1952 to 2023. It also uses a geographical detector and the MGWR model to identify influencing factors and spatial differences of the spatial pattern of ordinary universities from global and local spatial scales. The main conclusions are as follows.

- (1)

- From 1952 to 2023, the number of higher education institutions in China has shown a continuous upward trend. Their spatial clustering distribution pattern has become increasingly pronounced, with the primary aggregation centers located east of the Beijing Ring Line. The spatial distribution exhibits a northeast–southwest orientation, mirroring the distribution direction. This evolutionary trend reflects the gradual formation of a spatially sustainable layout that balances agglomeration efficiency and diffusion equity, laying the foundation for long-term stable development of higher education.

- (2)

- Results of geographic exploration reveal significant differences in influencing factors’ degrees of explanation of spatial differentiation. Among the factors are the number of full-time instructors, GDP, the number of R.O.C. national universities, and educational expenditures. Year-end highway mileage is a secondary influencing factor. Thus, HEIs’ spatial distribution results from the combined influence of multiple factors. The synergy of these factors is crucial for building a sustainable higher education ecosystem, where economic input provides the foundation, faculty strength guarantees quality, historical heritage offers continuity, and policy guidance optimizes equity.

- (3)

- The results of the MGWR model show that HEIs are concentrated in areas with high GDP levels, and their influence decreases from east to west in a circle. In the northwest and southwest regions, HEI construction relies on faculty strength more strongly than in other regions. The influence of historical background decreases stepwise from the core of the four southwestern provinces (districts) of Yungui–Guizhou–Sichuan–Guangxi to the northeast. Education expenditures significantly and positively impact HEIs’ distribution, especially in the southeast coastal region. These spatial heterogeneities imply that sustainable higher education development requires differentiated strategies, adapting to local conditions to avoid a “one-size-fits-all” approach and ensuring that resource allocation is both efficient and equitable.

- (4)

- Based on the above conclusions, the study formulated the following actionable recommendations aimed at promoting equitable access to resources: Establish a dynamic adjustment mechanism for higher education aligned with regional development: Implement differentiated policies across regions based on the spatial heterogeneity of influencing factors revealed by the MGWR model. In economically developed eastern regions, prioritize supporting universities in achieving breakthroughs in high-end, cutting-edge fields to strengthen the synergistic innovation effect between GDP and higher education. In central and western regions, prioritize faculty development through initiatives like “talent recruitment programs” and “teacher training projects” to enhance both the quantity and quality of full-time instructors. Simultaneously, leverage historical educational resources such as the sites of national universities from the Republican era to preserve institutional heritage. For central and western areas experiencing mismatches between GDP and higher education development, guide universities to establish programs aligned with local industrial needs (e.g., rural revitalization, specialty agriculture, regional cultural tourism), achieving precise alignment between higher education distribution and regional socioeconomic development (Cohen E).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.; methodology, J.S.; software, J.S. and M.C.; validation, J.S.; formal analysis, J.S. and J.Z.; resources, J.S. and M.C.; data curation, J.S. and M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S. and J.Z.; writing—review and editing, J.S. and F.Y.; visualization, M.C.; supervision, M.C.; project administration, J.S., J.L. and J.C.; funding acquisition, J.S., J.L. and J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42361028, 42271228), the Humanities and Social Science Fund of Ministry of Education (24YJC630028), the Humanities and Social Science Research Project of Guizhou Provincial Department of Education (24RWZX007).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare that we have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that could interfere with our study.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HEI | Higher education institutions |

| MGWR | Multi-scale Geographically Weighted Regression |

| NNI | Nearest Neighbor Index |

References

- Gu, H.; Shen, T. Spatial evolution characteristics and driving forces of Chinese highly educated talents. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2021, 76, 326–340. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.Y.; Cai, Q.F.; Chen, Z.J. University agglomeration, knowledge spillover and the cultivation of specialized, fined, peculiar and innovative “little giant” enterprises. Educ. Res. 2022, 43, 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.C.; Yu, Z.Y.; Li, S.H. Spatio-temporal characteristics and knowledge spillover effects of basic research output in Chinese colleges and universities. Econ. Geogr. 2024, 44, 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Liu, Z.T.; Chen, S.J. China’s road to the construction of a powerful country in higher education. J. High. Educ. Manag. 2024, 18, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gun, P.J. Comprehensive reform of higher education: Key points, difficulties and methods. China High. Educ. Res. 2024, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.G.; Li, J.; Xu, L. High-quality development of higher education in the context of invigorating China through education (journal articles)-understanding the principles of the national education conference. J. Northwest. Polytech. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2024, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson, P.A. The pure theory of public expenditure. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1954, 36, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X. Endogenous determination of public budget allocation across education stages. J. Dev. Econ. 2006, 81, 438–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, S. The efficient allocation of resources in education. Q. J. Econ. 1967, 81, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallee, J.M.; Resch, A.M.; Courant, P.N. On the optimal allocation of students and resources in a system of higher education. BE J. Econom. Anal. Policy 2008, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, H.; Johnes, G.; Oskrochi, R.; Crouchley, R. Stochastic frontier estimation of a CES cost function: The case of higher education in Britain. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2002, 21, 890–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.; Antuens, A.P. A GIS-based decision support tool for public facility planning. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2002, 29, 553–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijs, N.; Tim, S.; Frank, W. Evaluating the temporal organization of public service provision using space-time accessibility analysis. Urban Geogr. 2010, 31, 1039–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. The spatial distribution characteristics of China higher education institutions and their influential factors. J. High. Educ. 2021, 42, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, W.; Gao, W.D.; Zhang, M. Spatial distribution of higher education in China: Recent changes and influencing factors. Mod. Univ. Educ. 2013, 1, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, H.R.; Li, L.G. The layout of higher education agglomeration and its effect on regional innovation—An empirical study based on Chinese and American data. Educ. Res. 2024, 7, 92–107. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.C.; Wu, L.J.; Li, P. Spatial pattern of regional imbalance of higher education and its causes in China. Areal Res. Dev. 2020, 39, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.D.; Han, H.Y.; Liu, S.; Tang, Y.J. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of educational facilities in China. Areal Res. Dev. 2022, 41, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.W.; Li, X.J. Characteristics and influencing factors of the key villages of rural tourism in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2022, 77, 900–917. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, R.; Xiao, J.; Yang, Y.; Kong, X. The evolution of spatiotemporal patterns and influencing factors of high-level tourist attractions in the Yellow River Basin. Front. Earth Sci. 2020, 40, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, S. The evolution of university spatial agglomeration in South Korea: Evidence from kernel density and gravity center analysis. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2024, 25, 187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.X.; Li, M. The spatial interaction between inter-provincial migration and manufacturing industry transfer. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2019, 39, 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, Z.D.; Wang, T.; Yang, X.C. Spatio-temporal evolution of tourist attractions and formation of their clusters in China since 2001. Geogr. Res. 2020, 39, 1654–1666. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.F.; Xu, C.D. Geodetector: Principle and prospective. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 116–134. [Google Scholar]

- Fotheringham, A.S.; Yang, W.; Kang, W. Multiscale geographically weighted regression (MGWR). Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2017, 107, 1247–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.J.; Tang, J.Q.; Lin, H.L. Built environment effects on the spatio-temporal distribution of shared bikes based on multi-scale geographic weighted regression. Geogr. Res. 2023, 42, 2405–2418. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.C. The evolution of the spatial distribution pattern of higher education institutions in China and its influencing factors. Jiangsu High. Educ. 2022, 12, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.R. The evolution characteristics of China higher education spatial distribution and its development trends. J. High. Educ. 2019, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.L.; Zhao, Z.C.; Geng, M.R. Spatial layout of higher education resources and its impact on regional technological innovation capabilities—An empirical study based on China’s five major urban agglomerations. Mod. Univ. Educ. 2023, 39, 66–75+112. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).