Abstract

Amid intensifying challenges of global climate change, China—as the world’s largest carbon emitter and a major manufacturing hub—occupies a pivotal position in the global industrial green transformation. Drawing on environmental federalism theory and China’s decentralized governance model, this study develops a framework of “green finance–local government competition–industrial green transformation.” Using panel data from 283 cities in China, we employ spatial econometrics and mediation effect models to test the dual mechanisms by which green finance promotes industrial green transformation. The findings indicate that (1) green finance promotes industrial green transformation; (2) green finance advances industrial green transformation by dismantling China’s traditional local government competition–based development model and removing the institutional suppression arising from “race-to-the-bottom competition”; (3) the effect of green finance exhibits long-run characteristics and a “benchmark–imitation” pattern; (4) baseline environmental conditions strengthen the influence of green finance on industrial green transformation; (5) incorporating ecological civilization development into officials’ performance evaluations can effectively reshape policy incentives and amplify the positive role of green finance. Thus, we propose differentiated green finance policies, the construction of a governance mechanism that integrates fiscal–financial–ecological compensation, and the optimization of ecological civilization assessment indicators to curb campaign-style governance.

1. Introduction

The governance pathways explored by various countries to address climate change can be summarized as dual mechanisms of market and non-market approaches. The former centers on green finance, guiding resource concentration toward low-carbon sectors through capital pricing; the latter relies on administrative regulation, such as carbon taxes, to forcibly internalize environmental costs. Some EU member states (e.g., Bulgaria) have embedded green projects in regional recovery funds and have used green investment and other green finance instruments to address climate change [1]. The underlying logic is that high carbon taxes may significantly harm economic growth, reduce employment, and erode public support. In contrast, green finance may stimulate growth, expand employment, and improve public backing [2]. As the world’s largest carbon emitter, the effectiveness of China’s industrial green transformation depends on the success or failure of humanity’s response to climate issues [3]. The Chinese government attaches considerable importance to the role of green finance. In 2016, the People’s Bank of China and seven other ministries jointly issued the “Guidance on Building a Green Financial System,” positioning it as a key tool for addressing climate change. (Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/gkml/hbb/gwy/201611/t20161124_368163.htm (accessed on 9 December 2025)). In 2024, the People’s Bank of China and four other departments issued the “Opinions on Leveraging the Role of Green Finance to Serve Beautiful China Construction,” explicitly proposing that local governments should guide financial resources to support industrial greening and digitalization integration through policy tools such as “interest subsidies, subsidies, and rewards.” (China Government Website. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/202410/content_6979595.htm (accessed on 9 December 2025)). This signals China’s attempt to forge a distinctive pathway in which local governments—by improving the model of local government competition—integrate market incentives (green finance) with non-market governance (administrative guidance) to respond to environmental challenges.

Unlike direct-democracy systems, since the reform and opening-up period, China has developed a model of development rooted in a centrally coordinated, indirect-democracy institutional arrangement, characterized by salient “horizontal government competition.” This model promotes economic growth, but it also generates adverse environmental consequences. Cheung’s [4] “county competition theory” reveals the driving mechanism of the dual structure of fiscal decentralization and political centralization. Fiscal decentralization enables local governments to compete through investment attraction and industrial policies to pursue economic growth, whereas political centralization determines local official promotions according to superior government assessments of economic growth, thereby strengthening local competition [5,6]. However, this model has internalized significant negative environmental incentives. For instance, to compete for mobile capital and tax bases, local governments tend to relax environmental regulations and access thresholds, forming “race-to-the-bottom competition.” This not only leads to systematic weakening of environmental regulations, suppressing the institutional effect of industrial green transformation, but also excessively tilts fiscal resources toward traditional infrastructure and heavy industry, crowding out green technology R&D and environmental facility investment. Additionally, the official tenure system strengthens short-term performance demands, marginalizing the long-term investments necessary for green transformation and further solidifying the “race-to-the-bottom competition” logic.

Against this background, it is important to examine whether it is reasonable and practical for China to implement green finance policies with local governments as key actors. In the context of indirect democracy, whether local-government-led green finance can promote industrial green transformation is also an important theoretical question. Accordingly, this study addresses the question: Can green finance reconstruct China’s traditional model of “local government competition”? If so, through what mechanisms does it reshape that model and influence the trajectory of industrial green transformation?

To address environmental difficulties caused by government incentive misalignment, the 1970 U.S. Clean Air Act required the federal government to establish unified national environmental standards, with state governments being responsible for primary implementation, monitoring, and program execution. This model was summarized by Oates and Schwab [7] as environmental federalism theory, which applies traditional fiscal decentralization theory to environmental policy, advocating assigning decision-making authority to the government level closest to the cost–benefit subjects to ensure complete internalization of benefits and burdens. The EU Emissions Trading System further validated the high efficiency of multi-level governance, with covered sectors achieving a 43% reduction in emissions from 2005 to 2020 [8]. Millimet [8] summarized research on environmental federalism and proposed an environmental management system, indicating that optimal allocation of environmental protection functions at various government levels through quality management procedures addresses the vertical quality management defects of the environmental federalism theory [9].

Drawing on environmental federalism and environmental management theory, the Chinese government adopted mixed governance strategies targeting the domestic “horizontal competition” model. On the one hand, it uses non-market measures such as incorporating ecological civilization development into performance assessments to dismantle traditional “race-to-the-bottom competition” incentives. On the other hand, it develops market-based measures, such as green finance, to address funding needs and maturity mismatch issues in industrial green transformation, thereby compensating for the damage caused by local government competition under fiscal decentralization. This unique mechanism of “green finance reshaping local government competition” constitutes an important feature of China’s environmental governance. However, its internal transmission logic and specific effects on industrial green transformation still lack systematic theoretical elaboration and empirical testing.

Although existing research confirms the promotional role of green finance in industrial green transformation [10,11], it has two major limitations. First, the local government competition perspective is missing. China’s industrial green transformation is embedded in the institutional context of local “competition for growth.” The effectiveness of green finance is inevitably strengthened or weakened by local government strategic behaviors, such as selective implementation and policy arbitrage. However, existing literature does not incorporate such behaviors into analytical frameworks. Second, the environmental regulation theory is ambiguous. Although environmental decentralization theory emphasizes local autonomy in regulatory implementation, Chinese local governments simultaneously face the dual mechanism constraints of “vertical environmental supervision” and “horizontal government competition,” whose interactions may trigger more complex “race-to-the-bottom competition” or induce strategic “green races,” requiring clarification of their internal relationships.

Using panel data for 283 prefecture-level cities in China from 2003 to 2023, we test the hypotheses with a dynamic spatial lag modeling approach. Preliminary evidence suggests: (1) green finance promotes industrial green transformation, with lag and spatial spillover effects; (2) green finance advances transformation by dismantling the traditional local government competition model and eliminating the institutional suppression from race-to-the-bottom competition; (3) green finance’s influence is long-run and exhibits a benchmark–imitation effect; (4) baseline environmental conditions strengthen green finance’s effect; and (5) incorporating ecological civilization into officials’ assessments reshapes incentives and amplifies green finance’s positive role.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews relevant literature and develops the theoretical framework. Section 3 presents the research design, including data sources, methods, and variable definitions. Section 4 reports empirical results, including baseline regressions, mechanism analysis, and further analyses. Section 5 concludes, discusses implications, limitations, and policy recommendations.

2. Theoretical Framework

We follow Liu, Kumar, and Xu to define the core concepts. Kumar conceptualizes green finance as the increased flow of funds from governments, businesses, and the nonprofit sector toward achieving sustainable development goals [12]. Liu et al. emphasize that industrial green transformation centers on industrial pollution control and aims at low-carbon industrial development [13]. Xu defines local government competition as cross-regional competition among local governments in economic, environmental, and public service domains to attract labor, capital, and other production factors [14].

This study analyzes the internal logic of the theoretical framework of “green finance—local government competition—industrial green transformation,” from three aspects.

2.1. The Dual Impact Mechanism of Green Finance on Industrial Green Transformation

The impact mechanism of green finance on industrial green transformation is a collaborative mechanism between market-based measures and non-market governance. But scholars have not conducted sufficient research on it yet.

In the market dimension, green finance directly promotes industrial green transformation through capital allocation optimization and technological innovation empowerment. Its capital formation effect quantifies the environmental externalities of industrial projects, with risk-pricing tools guiding cross-period capital flows, creating market crowding-out effects on high-carbon assets while catalyzing industrial investment in green technology. This forms a capital allocation structure of “survival of the fittest” for the green industry [15]. It also empowers innovative technologies, with green credit, bonds, and venture capital to address the laboratory-to-market transformation gap dilemma of green technology development, reducing capital barriers and uncertainties in technological innovation [16]. Simultaneously, derivative instruments such as carbon market futures and green technology insurance accelerate knowledge spillover through price discovery mechanisms, driving industrial technology systems to leap from end-of-pipe treatment to low-carbon process revolution [17].

In the non-market transmission dimension, green finance indirectly drives industrial green transformation by dissolving traditional “local government competition.” Under China’s unique model of “central-local vertical decentralization” plus “horizontal government competition,” green credit scale and green bond issuance are adopted as performance measurement indicators for policy implementation. Consequently, green finance becomes critical in reconstructing official promotion incentive mechanisms. This prompts local governments to gradually withdraw from traditional GDP tournament models, elevating environmental cost internalization from enterprise micro-decisions to regional governance strategic levels, dissolving traditional industrial path dependence through the transmission chain of “green finance signals → institutional incentive reconstruction → industrial ecological reconstruction” [18], driving industrial green transformation [19].

Meanwhile, the mechanism by which green finance affects the green transformation of China’s industry remains underexplored. Therefore, we put forward the following hypothesis:

H1a.

Green finance positively affects industrial green transformation.

H1b.

The impact of green finance on industrial green transformation exhibits “benchmark-imitation” behavior.

H2a.

Green finance has a direct positive impact on industrial green transformation.

H2b.

Green finance indirectly drives industrial green transformation by dissolving traditional “local government competition”.

2.2. The Four-Dimensional Impact Mechanism of Green Finance on Local Government Competition

In direct-democracy systems, residents may directly elect municipal leaders, and public environmental preferences and participation can strongly shape local environmental action [20]. In many developing countries, however, local executives and councils may be appointed or determined by higher-level governments. In this context, China’s nested structure of “central-local vertical decentralization” and “horizontal government competition” creates a crucial institutional pathway through which green finance can foster industrial green transformation.

The current administrative division system in China operates under a four-tier management structure: province, prefecture, county, and township. Appointments of local government officials at all levels are typically initiated through preliminary nomination recommendations by higher-level governments, followed by election and decision-making by the People’s Congress of the corresponding administrative region. Residents directly elect People’s Congresses at the county and township levels, whereas members of People’s Congresses at the prefectural and provincial levels are elected by the People’s Congresses of the next lower tier. As of 2025, China’s prefectural-level governments consist of 293 prefecture-level cities, 7 prefectures, 30 autonomous prefectures, and 3 leagues. The prefecture-level city is the most prevalent form of prefectural-level government in China, while prefectures, autonomous prefectures, and leagues are special types of prefectural-level governments established by the Chinese government in response to the unique economic and social conditions of local areas. Appointments of prefectural-level government officials are usually proposed by provincial governments and subsequently elected and determined by prefectural-level People’s Congresses. Notably, neither provincial governments nor prefectural-level People’s Congresses are directly elected by residents. This institutional arrangement implies that the promotion prospects of prefectural-level government officials hinge on whether the development of their jurisdiction outperforms that of other prefecture-level cities within the same province during their tenure—i.e., whether they prevail in “horizontal government competition.” Additionally, only the National People’s Congress, provincial People’s Congresses, and prefectural-level People’s Congresses possess the authority to formulate laws and regulations. Prefectural-level governments and prefectural-level People’s Congresses serve as critical actors in the “vertical decentralization between the central and local governments,” endowed with the powers necessary for advancing local economic and social development.

Therefore, under China’s unique nested structure of “vertical decentralization between the central and local governments” and “horizontal competition among local governments,” the question of whether green finance can promote industrial green transformation lies in whether it can reshape the competition model of local governments. However, scholars have not conducted sufficient research on this. This study argues that green finance can dismantle the traditional “GDP competition” through four channels—fiscal expenditure structure, human capital flow, tax sources, and investment orientation—and can stimulate a positive feedback loop of “environmental quality–financial resources–industrial upgrading”.

In fiscal expenditure, traditional local government competition relies on fiscal investment in productive infrastructure to drive short-term GDP, displacing environmental protection and technology R&D investment while increasing long-term environmental governance costs [21,22]. Green finance significantly lowers financing thresholds for local government clean energy and pollution control projects through instruments such as green bonds and subsidized loans. This increases financing thresholds for traditional projects, forcing local governments to compress traditional infrastructure spending and increase investment in green areas such as pollution control and ecological restoration, and reducing long-term environmental governance costs.

In human capital flow, official promotional mechanisms that significantly positively influence economic performance lead local governments to “compete for growth,” thereby focusing on the short-term economic benefits of high-pollution labor-intensive industries. This deteriorates residential environmental quality and weakens cities’ attractiveness to high-quality talent [23]. Therefore, high-quality ecological environments supported by green finance are essential for attracting knowledge-based talent and providing a competitive advantage.

In tax sources, traditional tax reliance on land sales and heavy industry exacerbates environmental risks and fiscal vulnerability. Green finance enhances surrounding land premiums through ecological restoration projects, increasing “green premiums” in government land sale revenues. Moreover, it reduces tax burdens for compliant enterprises by subsidizing clean technology, but increases financing costs for high-pollution enterprises, providing new tax sources [24].

In investment orientation, traditional competition attracts high-pollution investment by relaxing environmental thresholds. Green finance breaks this race-to-the-bottom model by reconstructing incentive mechanisms as follows: reducing financing costs for green projects through policies such as green bond interest subsidies and central bank refinancing, improving their returns and attracting social capital to replace fiscal investment [25]; and through measures such as mandatory environmental information disclosure, increased risk weights for polluting enterprises, and environmental legal liability traceability that increases financing difficulties and costs for high-pollution industries [26].

The reshaping effect of green finance on local government competition models is moderated by their degree of path dependence, which is influenced by basic environmental levels. In regions with higher environmental levels, existing environmental governance facilities and policy systems strengthen the institutional stickiness of traditional competition models, forming a “high environmental endowment → high competition intensity” lock-in effect [27,28]. However, higher environmental quality entices human and financial factors to loosen the environmental constraints, thereby reducing the friction costs of institutional transformation, which allows green finance to dismantle traditional local government competition models. In regions with lower environmental quality, “fiscal—ecological” dual constraints easily induce suppressive path dependence. Although traditional competition models are not strengthened, transformational resource constraints significantly limit the competitive reshaping effectiveness of green finance, making it harder for green finance to dismantle traditional local government competition models.

At the same time, the mechanism of the impact of green finance on local government competition has not been fully studied. Therefore, we obtain the following hypothesis:

H3a.

Traditional local government competition models negatively affect industrial green transformation.

H3b.

Green finance negatively affects traditional local government competition models.

H4.

Basic environmental levels affect the magnitude of green finance’s adverse effects on traditional local government competition.

2.3. Impact Mechanism of Vertical Environmental Governance Decentralization and Horizontal Local Government Competition

China’s “vertical decentralization-horizontal competition” collaborative framework in environmental governance is a localized adaptation of environmental federalism. Coordination is achieved through political centralization that integrates ecological civilization construction into party-government joint responsibility assessments, constraining local discretionary power and enhancing institutional implementation rigidity under the dual framework of central standard-setting and local implementation; however, scholars have not studied this in depth. This institutional system transforms market-based tools such as green credit, environmental assessments, and green bond certifications into quantifiable environmental performance measures through environmental performance signal completion and reconstruction of incentives, embedding them in vertical governance procedures such as central environmental inspections and ecological civilization assessments [29]. These signals directly affect superior fiscal transfer payment amounts and official promotion probabilities, forcing local governments to adopt environmental quality as a new core competitiveness.

However, this institutional system faces dual dilemmas: (1) the paradox of fiscal authority centralization and implementation resource misallocation; and (2) resource endowment heterogeneity and the polarization effects of competitive strategies. In the former, the central government strengthens environmental standard control through measures such as cross-regional pollution control authority centralization and environmental vertical management reforms, weakening local government intervention capabilities. Nevertheless, the implementation of industrial green transformation still highly depends on local resource allocation and policy adaptation capabilities. This creates structural gaps between central environmental goals and local implementation resources—the central government controls standard-setting but lacks implementation mechanisms. In contrast, localities bear primary responsibility but face constraints in fiscal capacity and technical support. For the latter, resource endowment differences cause local governments to fall into “dual-track competition traps.” For instance, resource-rich regions form “high-carbon lock-in” due to traditional industry tax dependence (e.g., coal provinces relying on resource taxes) and relaxed environmental regulations to maintain short-term fiscal revenue, triggering “race-to-the-bottom competition,” whereas technology-intensive regions develop comparative advantages through green industry cultivation, forming “benchmark effects” of green technology diffusion, but face negative incentives owing to innovation spillover by neighboring regions [30]. This differentiation causes environmental regulation implementation to present regional fragmentation with coexisting “race-to-the-bottom competition” and “benchmark-imitation.”

The green finance system can address the deficiencies of the above mechanisms through a double-loop integration mechanism: the core problem of fiscal centralization and execution resource misallocation is whether the ecological environment is linked to the promotion of officials, and whether green finance can address this problem through the signal integration loop. In this loop, the market-oriented evaluation of green finance on local environmental performance exerts pressure on local governments to pursue green transformation through vertical assessment. It promotes industrial green transformation by reconstructing local government competition. The core issue of the heterogeneous polarization effect of resource endowments is the institutional distance between the central government and cities (measured by population size). In the capital transmission loop, we should guide capital to reconstruct the competitive incentives of local governments through the four channels of fiscal expenditure, human capital flow, tax source, and investment orientation, and promote the positive feedback cycle of “environmental quality–financial resources–industrial upgrading,” to improve environmental performance and realize the comprehensive green transformation of industry [31].

Meanwhile, the mechanism by which local government competition affects the green transformation of industry within the context of green finance remains underexplored. Therefore, we draw the following hypothesis:

H5.

The relationship between green finance, local government competition, and industrial green transformation is influenced by central-local relations.

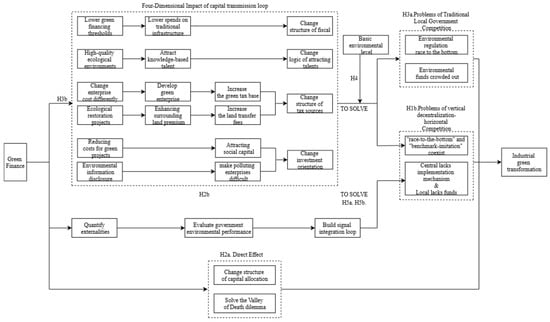

The mechanisms reveal that modern finance affects industrial green transformation through direct and indirect pathways. In direct channels, green finance promotes the green transformation of industry by optimizing capital allocation and fostering technological innovation. In indirect channels, modern finance not only dismantles problems brought by traditional local government competition but also resolves internal problems of the “vertical decentralization-horizontal competition” model, thereby promoting local industrial green transformation. It is specifically shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Impact mechanisms of capital transmission.

3. Research Design

3.1. Data Sources

Prefecture-level cities are key carriers of regional economic development and urban–rural coordination in China. We conducted empirical analysis using panel data for 283 prefecture-level cities from 2003 to 2023. China’s political system remained relatively stable during 2003–2025, and data for 2024–2025 were not yet fully released; thus, we focused on 2003–2023. Between 2003 and 2010, China had 283 prefecture-level cities; from 2011 onward, ten “regions” (another prefecture-level unit) were converted into prefecture-level cities. To maintain a consistent sample, we used the 283 cities established by 2003.

This study conducted empirical testing based on panel data from 283 prefecture-level cities in China from 2003 to 2023, obtaining variable data from the China City Statistical Yearbook (China’s Economic and Social Big Data Research Platform. Available online: https://data.cnki.net/yearBook/single?id=N2025020156&pinyinCode=YZGCA (accessed on 9 December 2025)), China Environmental Statistical Yearbook (China’s Economic and Social Big Data Research Platform. Available online: https://data.cnki.net/yearBook/single?id=N2025050388&pinyinCode=YHJSD (accessed on 9 December 2025)), China Agricultural Statistical Yearbook (China’s Economic and Social Big Data Research Platform. Available online: https://data.cnki.net/yearBook/single?id=N2024081134&pinyinCode=YZGNV (accessed on 9 December 2025)), China Agricultural Statistical Report (China’s Economic and Social Big Data Research Platform. Available online: https://data.cnki.net/yearBook/single?id=N2019120059&pinyinCode=YZGNT (accessed on 9 December 2025)), China Rural Statistical Yearbook (China’s Economic and Social Big Data Research Platform. Available online: https://data.cnki.net/yearBook/single?id=N2025020018&pinyinCode=YMCTJ (accessed on 9 December 2025)), China Tourism Statistical Yearbook (China’s Economic and Social Big Data Research Platform. Available online: https://data.cnki.net/yearBook/single?id=N2020030028&pinyinCode=YBGTE (accessed on 9 December 2025)), China Energy Statistical Yearbook (China’s Economic and Social Big Data Research Platform. Available online: https://data.cnki.net/yearBook/single?id=N2024050932&pinyinCode=YCXME (accessed on 9 December 2025)), China Water Resources Bulletin (Water Resources of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://www.mwr.gov.cn/sj/tjgb/szygb/(accessed on 9 December 2025)), China Compendium of Statistics 1949–2008 (China’s Economic and Social Big Data Research Platform. Available online: https://data.cnki.net/yearBook/single?id=N2010042091&pinyinCode=YXZLL (accessed on 9 December 2025)), China Science and Technology Statistical Yearbook (China’s Economic and Social Big Data Research Platform. Available online: https://data.cnki.net/yearBook/single?id=N2025020147&pinyinCode=YBVCX (accessed on 9 December 2025)), China Financial Yearbook (China’s Economic and Social Big Data Research Platform. Available online: https://data.cnki.net/yearBook/single?id=N2025110624&pinyinCode=YXCVB (accessed on 9 December 2025)), environmental bulletins of various provinces and cities, and statistical yearbooks of some provinces and cities. Based on China city maps with review number GS(2024)0650, this study used the Albers projection coordinate system to calculate China’s geographical distance matrix, combining GDP data from the China City Statistical Yearbook to obtain China’s geographical-economic distance matrix.

3.2. Models

3.2.1. Baseline Model

To verify the impact of green finance on industrial green transformation, we established a baseline spatial econometric model. A spatial Durbin model was used to capture spatial correlations among variables:

where represents the industrial green transformation level of city in year ; represents the green finance index of city in year . is the spatial weight matrix, is the spatial autoregressive coefficient (represented as RHO in the table below), represents control variables, and are city fixed effects and time fixed effects, respectively, and is the residual. Equation (1) establishes a Spatial Durbin Model to identify both local and spillover effects of green finance on industrial green transformation. The spatial lag of the dependent and explanatory variables allows the model to capture spatial autocorrelation and cross-city diffusion mechanisms.

3.2.2. Mediation Effect Model

To test the mediating role of local government competition in the effect of green finance on industrial green transformation, we constructed spatial mediation effect models, following Baron and Kenny [32].

First, we explored the impact of green finance on industrial green transformation, with the model set the same as Equation (1).

Equation (1) serves as the baseline estimation of the total effect of green finance on industrial green transformation. By including spatial lags, it quantifies how local green finance and neighboring cities’ green finance jointly influence green transformation outcomes.

Second, the model for the impact of green finance development on local government competition was set as

Equation (2) evaluates the impact of green finance on local government competition. The spatial lag structure indicates that government competition is shaped not only by local financial development but also by competitive dynamics in adjacent cities.

Third, the model for the joint impact of green finance development and local government competition on industrial green transformation was set as

Here, represents the local government competition level of the city in year . The magnitude of the mediation effect is measured by , where and represent the impact coefficients for green finance on government competition and government competition on green transformation, respectively. Equation (3) incorporates both green finance and government competition into the spatial model to test the mediating mechanism, while spatial lags identify how mediation effects propagate across geographic space.

3.2.3. Moderated Mediation Effect Model

Because the path dependence intensity of traditional local government competition models varies under different environmental levels, we constructed a moderated mediation effect model. Using urban green space area as a proxy for environmental level, the moderating effect of urban green space on green finance dismantling traditional local government competition models is explored as follows:

where represents the moderating variable. Urban garden green space area proxies the differences in the impact of green finance on industrial green transformation under environmental factors. Equation (4) introduces a moderated mediation framework by combining government competition with environmental conditions. The model assesses how urban green space alters the strength of the mediation channel and how this moderated mechanism generates spatial spillover effects.

3.2.4. Grouped Regression

The core of the resource endowment heterogeneity polarization effect problem is the institutional distance between central and local governments, which determines the effective allocation of resources across regions. Traditional administrative hierarchies cannot accurately reflect the closeness of central-local governance. Drawing on the Chinese Communist Party’s “people-oriented” governing philosophy, this study uses differences in urban population to measure the central government’s attention to cities, representing the institutional distance between central and local levels. For cities with large populations, the central government employs various tools, including cities under separate planning, special administrative regions, and central government municipalities. For cities with small populations, the central government delegates provincial governments to manage cities. To verify H5, this study discusses the impact of green finance and local government competition separately for megacities, super cities, large cities, medium cities, and small cities.

3.3. Variable Settings

3.3.1. Dependent Variable

Following Chen and Golley [33] and Zhang et al. [34], this study measures industrial green transformation using green total factor productivity (TFP) to calculate TFP based on the SBM model and Malmquist-Luenberger productivity index. Desired output selects secondary industry GDP, undesired outputs select solid waste, industrial wastewater, industrial waste gas, carbon emissions, and PM2.5, and input factors select secondary industry fixed asset investment calculated by the perpetual inventory method and secondary industry average employment.

3.3.2. Core Explanatory Variable

Drawing on Li et al. [35], Yin et al. [36], and Guo et al. [37], we use the entropy method to calculate green finance indices, employing standardized green finance indices of Chinese prefecture-level cities to represent the development level of green finance. The green finance index encompasses several key dimensions, including green credit, green investment, green insurance, green bonds, green support, green funds, and green equity. Table 1 lists the information on core variables.

Table 1.

Composition of core variables.

3.3.3. Mediating Variable

This study measures traditional local government competition levels from four aspects: local human capital, local fiscal tax revenue, local fiscal general budget expenditure, and local direct investment, using principal component analysis to reduce dimensions and obtain local government competition levels [38]. The principles of this measurement are as follows. (1) Constructing government competition indicators based on tax competition: Chinese local governments can influence actual corporate tax rates by changing tax collection intensity, engaging in tax competition to attract financial factors. (2) Constructing government competition indicators based on human capital: Chinese local governments can reduce specific talent living costs through talent introduction subsidies, public rental housing, and other policies, engaging in talent competition to attract talent. (3) Constructing government competition indicators based on local fiscal general budget expenditure: to attract external capital, local governments compete by investing resources to improve investment environments related to investment projects through fiscal competition. (4) Constructing government competition indicators based on local direct investment: to stimulate local economies, Chinese local governments directly invest in heavy industry and infrastructure construction industries, driving more industrial development. Because appointments and promotions of Chinese prefecture-level city cadres are mainly handled by provincial party committees and provincial organization departments, officials in each city only need to compete with officials from other cities within the province for promotion. Therefore, this study divides city data by provincial data averages to obtain local government competition levels related to official promotions and demotions.

3.3.4. Control Variables

To ensure reliability and validity of measurement results, this study selects economic development level (PERGDP), environmental regulation level (ERS), per capita infrastructure stock (PERINV), and tourist attractiveness (TOUR) as model control variables. The specific approach is as follows:

- Economic development level is affected by long-term local government competition, local resource endowments, and regional policy allocation, but may not significantly affect short-term local government competition. Chinese official terms are generally within five years, while local industrial development usually requires more than five years, indicating obvious term mismatches. Using the economic development level to measure local government competition would create obvious errors; therefore, this study treats it as a control variable for constraint. This study uses per capita GDP, measured by total regional population, as the economic development level. Regions with higher economic development levels have higher TFP [39].

- Environmental regulation levels are affected by central government regulation and local government competition. The central government prescribes high vs. low environmental regulation levels for cities located in central government-planned nature reserves or ecologically fragile areas vs. those in planting or breeding planning areas to ensure national food security. Additionally, local environmental regulation levels are important measures for promoting industrial green transformation. This study uses weighted averages of waste treatment and sewage treatment rates to measure the environmental regulation level [40]. Environmental regulation levels may have inverted U-shaped effects on industrial green transformation: when environmental regulation levels are low, environmental regulation suppresses traditional industrial development, creates comparative advantages for green industry, and promotes green industrial development; when environmental regulation levels are high, it will not only suppress traditional industrial development but also suppress green industrial development. In empirical testing, this study uses environmental regulation levels (environmental regulation level squares) to control the first (second) half of the inverted U-shaped effect.

- Per capita infrastructure investment stock has causes like those of the economic development level. This study uses per capita infrastructure investment, measured by total regional population, as the infrastructure investment indicator . The greater the infrastructure investment, the higher the TFP [39].

- Traditional Chinese industrial city transformation has two main pathways: industrial green transformation and tourism development [41]. This study focuses solely on the impact of industrial green professional pathways, rather than tourism pathways, which constrains the development of tourism pathways. This study uses domestic tourists (10,000 person-times) as the tourist attractiveness indicator .

3.3.5. Moderating Variable

According to Zhou et al. [42], green space construction level is a representative variable of urban environmental level, with significant positive spatial spillover effects that may attract talent and investment. Hence, regions with better green space construction levels have lower friction costs for institutional transformation and weaker “fiscal-environmental” dual constraints, enabling green finance to dismantle local traditional government competition models more easily. This study selects the weighted average urban green space area as the moderating variable.

3.4. Descriptive Statistics of Variables and Collinearity Analysis

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistical results of all variables in this study. From the perspective of core explanatory variables, the average value of green finance is 0.3053, the average value of local government competition is 1.3867, and the average value of industrial green transformation is −1.2491.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 3 shows the collinearity among the variables. From the perspective of the core explanatory variables, there is a significant negative correlation between local government competition and the green transformation of industry (Coef. = −0.0182, p < 0.001), which is consistent with hypothesis H3a. There is a significant positive correlation between green finance and the green transformation of industry (Coef. = 4.1837, p < 0.001), which is consistent with Hypothesis H1a.

Table 3.

Collinearity analysis.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Baseline Regression

Table 4 Baseline regression presents the baseline regression results. The results verify the positive impact of green finance on industrial green transformation and its cross-regional policy coordination effects, supporting H1a and H1b. The no-control variable model in (1) and the complete model regression in (2) show that the R2 of the impact of green finance on the green transformation of industry is approximately 0.2, indicating that the direct effects and “benchmark-imitation” effects of green finance can explain approximately 20% of industrial green transformation variation. The green transformation of China’s industry may also be influenced by factors such as technological progress, urbanization, and the carbon tax system. Therefore, the R2 of the impact of green finance on the green transformation of industry is relatively low. The spatial interaction term has a significant positive impact on the green transformation of industry. This indicates that the green finance practices in leading regions will prompt neighboring regions to complete the industrial green transformation, that is, green finance may have a “benchmark-imitation effect”.

Table 4.

Baseline regression.

4.2. Robustness Testing

4.2.1. Changing Spatial Distance Matrix

As China’s official promotion assessment has long centered on economic development performance, geographical proximity may struggle to capture the core logic of institutional learning effectively—convergence in economic development levels between cities is the key constraint on policy imitation feasibility. This study replaces the geographical distance matrix with a geographical-economic distance matrix, integrating geographical and economic distances through the following formula:

where is geographical-economic distance, is the straight-line distance between cities, is city i’s per capita GDP annual average, and is all cities’ per capita GDP annual average.

Table 5 Baseline regression after replacing the weight matrix presents the regression results after replacing the weight matrix. The positive impact of green finance on industrial green transformation and its cross-regional policy coordination effects remains significant, supporting the robustness of H1a and H1b. Compared with the geographical distance matrix, the geographical-economic distance matrix increases the green finance effect from 0.1405 to 0.2747 and the “benchmark-imitation” effect from 0.2082 to 0.2334. This reveals spatial selection preferences for institutional learning under the central “vertical assessment-local bidding” governance framework—cities that are geographically proximate and within economic convergence ranges have stronger policy learning motivations.

Table 5.

Baseline regression after replacing the weight matrix.

4.2.2. Setting Instrumental Variables

Green finance affects not only the current industrial green transformation through green subsidies, but also the long-term transformation through green infrastructure. Meanwhile, regions with better industrial green transformation may obtain green finance support more easily; although lagging industrial green transformation by one period does not affect local green finance acquisition difficulty, it effectively solves endogeneity problems. Therefore, this study uses industrial green transformation lagged by one period as an instrumental variable for current industrial green transformation to control endogeneity and conduct robustness testing.

Table 6 Baseline regression with a one-period lag presents the regression results with a one-period lag. The positive impact of green finance on industrial green transformation and its cross-regional policy coordination effects remains significant, confirming the robustness of the results for H1a and H1b. Using green finance data lagged by one period, the effect is 0.1060, indicating that green finance also affects industrial green transformation through long-term means such as green loans and green infrastructure. The “benchmark-imitation” effect of 0.1208 reveals that these effects have policy time lags, with local governments experiencing decision response delays, manifesting as information transmission and competitive strategy adjustment delays, in cross-regional institutional learning.

Table 6.

Baseline regression with a one-period lag.

4.3. Mechanism Analysis

Table 7 and Table 8, presents the test results of the mediation effect models, which reveal that green finance drives industrial green transformation through dual institutional logic. The market-based transmission pathway (direct effect β = 0.1387, p < 0.05) confirms the collaborative mechanism of capital reallocation and technology promotion, supporting H2a. Green finance guides cross-period capital flows through risk pricing tools, creating market crowding-out effects on high-carbon assets while catalyzing green technology industrialization investment by breaking through the “valley-of-death” dilemma from green technology laboratories to mass production.

Table 7.

Mediating effect test.

Table 8.

Coefficient of mediating effect.

The mediating effect test results (Table 7 and Table 8) indicate that green finance drives industrial green transformation through dual institutional logics, thereby supporting Hypotheses H2a, H2b, H3a, H3b, and H4.

The influence coefficient for the direct effect is 0.1381 (p < 0.05), indicating that green finance directly promotes industrial green transformation; thus, H2a is supported. The influence coefficient for the indirect effect is 0.0087 (p < 0.05), indicating that green finance promotes industrial green transformation by influencing traditional local government competition. In (3), the influence coefficient of local government competition on industrial green transformation is −0.0064 (p < 0.05), and traditional local government competition will negatively affect industrial green transformation; thus, Hypothesis H3a is established. In (2), the influence coefficient of green finance on local government competition is −1.3637 (p < 0.05), indicating that green finance inhibits traditional local government competition; therefore, H3b is supported.

This study further explores how green finance affects local government competition under basic environmental level constraints by introducing interaction terms to verify whether basic environmental levels influence the green finance effect on local government competition. Table 9 Moderated mediation effect presents the moderation effect testing results.

Table 9.

Moderated mediation effect.

According to Table 9, the basic environment level has a significantly positive impact on traditional local government competition (β = 0.0000, p = 0.0010), which means that in regions with a good environment, the traditional local government competition level is stronger. The coefficient of the cross term between green finance and the basic environmental level is significantly negative (β = 0.0000, p = 0.0120), indicating that in regions with a good environment, the impact of green finance on industrial green development is lower. Although the moderating effect is minimal, this test result indicates that green finance should consider eliminating the promotional effect of high environmental levels on local government competition through ecological compensation.

4.4. Further Analysis

Cities of different scales have different relationships with the central government. The Chinese government tends to directly manage cities with large populations through direct administration and separate planning, and indirectly manages cities with small populations through provincial governments. Therefore, this study separately analyzes cities by five population categories: small cities (less than 500,000), medium cities (500,000–1 million), large cities (1–5 million), super cities (5–10 million), and megacities (over 10 million). Table 10, the impact results under different city sizes, presents the regression results for different city sizes. The grouped regression reveals the “institutional distance-financial capital-competitive strategy” framework for green finance’s effect on industrial green transformation.

Table 10.

The impact results under different city sizes.

The grouped regression in Table 10 reveals the impact of green finance on industrial green transformation in different city sizes, thereby supporting H5a.

The influence coefficient of local government competition on industrial green transformation is negative and significant in all cities except megacities, with little variation across city groups. In contrast, local government competition in megacities has no significant impact on industrial green transformation. The difference between the two may be attributable to the intensity of local government competition.

The influence coefficient of green finance on industrial green transformation shows differentiated impacts. In many small cities in China, green finance has a significantly positive effect on industrial green transformation. In large and medium-sized cities in China, the impact of green finance on industrial green transformation is not significant. The difference between the two may be related to the degree of capital abundance across cities: it is relatively high in large and medium-sized cities, whereas it is lower in small cities.

The influence coefficient of the spatial interaction term in green finance exhibits a third-order differentiation pattern, indicating a third-order differentiation in the “benchmark-imitation” effect. Differences in national positioning in megacities inhibit horizontal imitation, and the “benchmark-imitation” effect is significantly negative (β = −0.1455). Megacities and large cities exhibit characteristics of homogeneous competition, and the “benchmark-imitation” effect is significant, with a high coefficient (β > 0.2). Small and medium-sized cities tend to develop characteristic green industries based on local resource endowments, and the “benchmark-imitation” effect is positive but weak (β ≤ 0.1).

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

By integrating the panel data of 283 prefecture-level cities in China from 2003 to 2023, this study examines the dual impact of green finance on industrial green transformation. It reveals the mechanism by which China’s unique “vertical decentralization and horizontal competition” environmental governance framework affects industrial green transformation and the important role of green finance. We formulated nine hypotheses based on theoretical analysis and tested them using a spatial econometric model and a mediation model. The empirical results show that all hypotheses hold. We obtained five core findings: (1) Green finance has a positive effect on industrial green transformation, with a lagged effect and spatial spillover effect. (2) By disintegrating China’s traditional development model of local government competition, green finance eliminates the institutional inhibition of the “race to the bottom” on industrial green transformation. (3) The impact of green finance on industrial green transformation has the characteristics of long-term impact and the “benchmark-imitation” effect. (4) The basic environmental level can promote the impact of green finance on industrial green transformation. (5) Incorporating the development of ecological civilization into the assessment of local officials can effectively change policy incentives and enhance the positive role of green finance in industrial green transformation.

5.2. Discussion

Most prior research focused on the role of government in sustainable development under the system of direct democracy. In contrast, our research discusses the role of local government in sustainable development under the government system of “horizontal government competition” + “vertical central-local decentralization” in China. It discusses the path of green finance affecting industrial green transformation in detail. It provides a reference for the government’s sustainable development policy-making under the indirect democratic system.

Unlike other studies, we construct the dual institutional logic of green finance driving industrial green transformation based on the theory of environmental federalism. The core of this logic lies in the construction of institutional infrastructure for the synergy between market incentives and administrative regulations. In the market dimension, green finance reshapes the factor allocation structure through the capital pricing mechanism, and promotes green technologies to overcome the transformation fault dilemma from laboratory to market through financial support. In the administrative dimension, green finance systematically disintegrates the traditional “GDP tournament” through the four paths of fiscal expenditure structure, human capital flow, tax sources, and investment orientation, and weakens the institutional problems of China’s “vertical decentralization and horizontal competition” model through the signal integration loop and capital transmission loop.

We further consider the cross-temporal and cross-spatial impacts of green finance under the framework of dual institutional logic. We put forward the long-term impact characteristics of the dual impact of green finance and the “leverage-imitation” effect, which further improves the positive feedback cycle of “environmental quality–financial resources–industrial upgrading” of green finance. Under the incentive of an official promotion tournament, local governments gain promotion advantages by imitating the practices of the leading regions in green finance policy. This forms a “leverage-imitation” effect, accelerating the collapse of the traditional “race to the bottom” local government competition mode. In cross-regional institutional learning, local governments have delayed decision-making responses, and it takes time to verify the technical details and implementation effects of green finance policies, which weakens the short-term imitation motivation among different cities.

In view of the characteristics of local government competition in China, we propose that green finance systematically disintegrates the traditional “GDP tournament” through the four paths of fiscal expenditure structure, human capital flow, tax source, and investment orientation. In terms of basic environment level, in places with a high basic environment level, although there is a lock-in effect of “high environmental endowment → high competition intensity,” the friction cost of institutional transformation is low, and green finance can easily disintegrate traditional local government incentives. In terms of assessment and incentive, after ecological civilization was included in the assessment, the triple incentive reconstruction of financial incentive and policy coordination strengthened the role of green finance in industrial green transformation. In terms of city size, the hierarchical competition of urban governance in China makes the “benchmark-imitation” effect of green finance present a third-order differentiation pattern.

5.3. Theoretical and Practical Significance

This research has significant theoretical and practical importance. At the theoretical level, we discuss the detailed mechanism of green finance affecting industrial green transformation, construct the functional framework of “green finance–local government competition remolding–industrial green transformation” and the collaborative analysis framework of “vertical decentralization–horizontal competition”, and identify the reshaping effect of green finance and the response mechanism of industrial green transformation. This paper also explores the “benchmark-imitation” effect of green finance through a spatial econometric model, which expands the application boundary and explanatory power of environmental federalism theory. At the practical level, we explain a green transition path suitable for centralized indirect democracies, which provides an empirical case similar to the national situation for developing countries, and provides a reference for developing countries to formulate governance policies integrating market and non-market mechanisms, so as to achieve sustainable development.

5.4. Suggestions

Based on the study’s findings, we offer the following recommendations for governments in countries that adopt indirect democracies:

Local governments need to build appropriate green finance toolkits based on urban endowment characteristics to reduce the frictional costs of institutional transformation. Megacities should strengthen the hub function of green finance and provide risk mitigation and intellectual property pledge financing services for cross-regional technology transformation by setting up regional green technology innovation funds. Megacities and large cities need to establish a dual-track mechanism of “special debt for high-carbon industrial transformation + ecological restoration trust.” Part of the tax revenue from traditional energy, such as coal and steel, is converted into a green transformation fund, which is used for subsidies for clean technology research and development, and the loan pledged by carbon sink earnings is simultaneously developed to realize the transformation of ecological value into fiscal revenue. Small and medium-sized cities need to focus on the securitization of characteristic ecological resources, utilize localized resources to develop exclusive financial derivatives to form comparative advantages, and avoid homogeneous competition with large cities and megacities.

The central government should take green fiscal power reform as the core to break the dilemma of resource misallocation. First, a dynamic adjustment system of transfer payment based on environmental performance is established to link the growth rate of local green TFP with the amount of central transfer payment, forming a positive incentive of “governance improvement → fiscal benefit.” Second, trans-regional ecological compensation funds should be piloted in resource-based provinces. Finally, financial guarantees for green projects should be implemented to enhance credit, green bonds should be set up to provide risk reserves, and green funds should be allowed to participate in long-term projects through preferred stock agreements.

It is necessary to balance the contradiction between long-term transformation and short-term behavior through the fine design of the assessment system, restrain the government’s motion-type governance, build an institutional framework to ensure that the social costs of industrial iteration are controllable, set tolerance thresholds for unemployment rate fluctuations and output value losses during the transformation period, and avoid “one-size-fits-all” shutdown. This could involve establishing an embedded audit mechanism for central environmental protection inspectors, conducting special audits on the efficiency of local governments’ green finance funds, and making it mandatory that plans to shut down polluting enterprises be accompanied by plans to resettle workers and restructure industries.

5.5. Limitations

The research in this paper has the following limitations, which can be further examined by future researchers:

- Limitations of the research sample. This paper discusses the role of local government competition in China. However, since different countries have different political systems, broader discussions are needed that are based not only on one country’s political system. In order to make up for this limitation, we divide the political systems of each country according to direct democracy and indirect democracy, and limit the scope of application of this study (that is, countries that adopt indirect democratic systems). Future scholars may further explore the role of local government competition in direct democracies and make a comparative analysis of the role of local government competition among different countries and political systems.

- Limitations of methodology. This paper discusses the impact of green finance over time, but it does not solve the problem of how green finance affects each market and each factor. In the future, scholars can further refine the theory of environmental federalism and employ economic models and methods, such as dynamic multiregion computable general equilibrium models, to broaden its applicability.

- Limitations of mechanism analysis. Based on the theory of environmental federalism, this paper incorporates local government competition into the analysis of sustainable development. However, it does not use other political and sociological theories to further discuss local government competition. In the future, scholars can further explore the role of organizational form, incentive mode, and behavior mode of local government officials in the field of sustainable development, and use the specific models of political science and sociology to solve future problems in sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, visualization, investigation, H.L.; data curation, writing—original draft preparation, Y.D.; supervision, writing—review and editing, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Mendeley Data at http://doi.org/10.17632/trcd7kpv55.1, reference number trcd7kpv55.

Acknowledgments

My deepest appreciation goes to my colleagues for their unwavering support and understanding. I am also grateful to my tutors for their encouragement and assistance during this process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| R&D | Research & development |

| GDP | Gross domestic product |

| TFP | Total factor productivity |

| SBM | Slacks-Based Measure |

References

- Kotseva-Tikova, M.; Dvorak, J. Climate policy and plans for recovery in Bulgaria and Lithuania. Rom. J. Eur. Aff. 2022, 22, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Rao, R. Exploring the impacts of a carbon tax on the Chinese economy using a CGE model with a detailed disaggregation of energy sectors. Energy Econ. 2014, 1, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.; Li, H.; Tan, S. Carbon markets, energy transition, and green development: A moderated dual-mediation model. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1257449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S.N.S. The Economic System of China; AP Press: Beijing, China, 2008; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, L.; Ding, Y.; Li, X. Environmental regulation competition and carbon emissions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maskin, E.; Qian, Y.; Xu, C. Incentives, information, and organizational form. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2000, 67, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, W.E.; Schwab, R.M. Economic competition among jurisdictions: Efficiency-enhancing or distortion-inducing? J. Public Econ. 1988, 35, 333–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millimet, D.L. Environmental federalism: A survey of the empirical literature. Case West. Res. Law Rev. 2013, 64, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondinelli, D.; Vastag, G. Panacea, common sense, or just a label? Eur. Manag. J. 2000, 18, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Song, L.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, C. Does green finance promote the green transformation of China’s manufacturing industry? Sustainability 2023, 15, 6614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhong, H.; Wang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Tang, D. The effect of green finance on the transformation and upgrading of manufacturing industries in the Yangtze River economic belt of China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1473621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Kumar, L.; Kumar, A.; Kumari, R.; Tagar, U.; Sassanelli, C. Green finance in circular economy: A literature review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 16419–16459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xin, L.; Li, J.; Sun, H. The impact of renewable energy technology innovation on industrial green transformation and upgrading: Beggar thy neighbor or benefiting thy neighbor. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ge, W.; Liu, G.; Su, X. The impact of local government competition and green technology innovation on economic low-carbon transition: New insights from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 23714–23735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, D.Y.; Zhang, Y. Do shareholders benefit from green bonds? J. Corp. Financ. 2020, 61, 101427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mašek, J.; Plaček, J. Exploring the role of venture capital in advancing green innovation: A systematic literature review. Acta Montan. Slovaca 2024, 29, 839–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Wei, Y.; Tan, L. Low-carbon technology adoption and diffusion with heterogeneity in the emissions trading scheme. Appl. Energy 2024, 369, 123537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Xing, X.; Iqbal, N. Multi-dimensional competition in local governments, performance pressures, and corporate green innovation in China. J. Appl. Econ. 2024, 27, 2351267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikau, S.; Volz, U. Central Bank mandates, sustainability objectives, and the promotion of green finance. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 184, 107022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitálišová, K.; Dvořák, J. Differences and similarities in local participative governance in Slovakia and Lithuania. In Participatory and Digital Democracy at the Local Level: European Discourses and Practices; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 125–146. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.; Treisman, D. Does competition for capital discipline governments? Decentralization, globalization, and public policy. Am. Econ. Rev. 2005, 95, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X. Reforms, investment, and poverty in Rural China. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 2004, 52, 395–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yue, Q.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, M. Air pollution, human capital, and urban innovation in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 38031–38051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, B.; Bao, H.; Liang, Y. A study of the effect of a high-speed rail station on spatial variations in housing price based on the hedonic model. Habitat Int. 2015, 49, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Green bond issuance and corporate cost of capital. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2021, 69, 101626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, J. Asymmetric impacts of the policy and development of green credit on the debt financing cost and maturity of different types of enterprises in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecere, G.; Corrocher, N.; Gossart, C.; Ozman, M. Lock-in and path dependence: An evolutionary approach to eco-innovations. J. Evol. Econ. 2014, 24, 1037–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp-Benedict, E. Shifting to a green economy: Lock-in, path dependence, and policy options. In MPRA Paper 60175; University Library of Munich: Munich, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Oates, W.E.; Portney, P.R. The political economy of environmental policy. In Handbook of Environmental Economics; Mäler, K.-G., Vincent, J.R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 325–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Wan, K.; Wu, F.; Zou, W.; Chang, T. Local government competition, development zones and urban green innovation: An empirical study of Chinese cities. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2022, 29, 1509–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinping, L.; Zeeshan, M.; Rehman, A.; Uktamov, K. A green revolution in the making: Integrating environmental performance and green finance for China’s sustainable development. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1388314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Golley, J. ‘Green’ productivity growth in China’s industrial economy. Energy Econ. 2014, 44, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, R.; Zhang, J. Understanding the green total factor productivity of manufacturing industry in China: Analysis based on the super-SBM model with undesirable outputs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-X.; Xia, G. China Green Finance Report; Chinese Finance Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Z.-B.; Sun, X.-Q.; Xin, M.-Y. Research on the impact of green finance development on green total factor productivity. Stat. Dec. 2021, 37, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.-Q.; Wang, X.; Cao, D.-D.; Hou, Y.-G. The impact of green finance on carbon emission—Analysis based on mediation effect and spatial effect. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 844988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, X.; Bi, S.; Yin, Y. The impact of fiscal decentralization and intergovernmental competition on local government debt risk: Evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1103822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsina, G.; Stern, D.I.; Das, D.K. Physical infrastructure and economic growth. Appl. Econ. 2024, 56, 2142–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domazlicky, B.R.; Weber, W.L. Does environmental protection lead to slower productivity growth in the chemical industry? Environ. Resour. Econ. 2004, 28, 301–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, H.; Maqbool, S.; Tarique, M. The relationship between tourism and economic growth among BRICS countries: A panel cointegration analysis. Future Bus. J. 2021, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Liu, Y.; He, M. The spatial interaction effect of green spaces on urban economic growth: Empirical evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).