Abstract

To ensure healthcare is environmentally sustainable for future generations, it is crucial to analyze the environmental impact of medical activities. With the rise of single-use medical devices, there is a growing need to compare their environmental footprint with that of conventional multiple-use solutions. This study aimed to review existing literature on the life cycle assessment (LCA) of single-use and multiple-use endoscopes, focusing on how system boundaries, goals, and scopes are defined, as well as identifying environmental impacts and hotspots. A literature review was conducted using the PRISMA framework, with searches performed on the Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed. A multi-stage screening process resulted in the selection of 12 studies for detailed review. The analysis revealed a significant lack of comprehensive, comparative LCA studies that evaluate the environmental trade-offs between these two endoscope types across their entire lifecycles. Many existing studies focus only on specific life cycle stages, making comparison between results impossible. This review highlights the need for more holistic, cradle-to-grave analyses to inform more sustainable healthcare decisions.

1. Introduction

Environmental issues have been gaining increasing attention and significance worldwide, with escalating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions emerging as one of the most existential challenges of the 21st century [1]. The healthcare sector is a significant contributor to environmental pollution, accounting for up to 5% of global GHG emissions (approximately 2 gigatons of CO2 equivalent emissions) across the entire life cycle, including raw material extraction, manufacturing, transportation, and end of life [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Statistics from the health care sector are particularly alarming. The climate footprint of the global healthcare sector is equivalent to the annual greenhouse gas emissions from 514 coal-fired power plants [4]. If the healthcare sector were considered a country, it would rank as the fifth-largest emitter worldwide [4]. The United States, China, and European Union collectively account for more than half of all combined health care’s climate footprint [7].

Therefore, the healthcare sector, as a significant GHG contributor, can play a leading role in resolving the crisis [8]. In recent years, there has been increasing demand for evidence of the environmental impact of products used in healthcare settings and of methods to reduce that impact [9]. To ensure high-quality healthcare for future generations, healthcare activities must be delivered while considering the environmental aspects [10].

Trend analyses indicate that healthcare GHG emissions have increased by nearly one-third over the past two decades in both low- and high-income countries [11]. One of the most important factors contributing to this escalating trend is the fact that many devices used in healthcare are intended for single patient use and are subsequently disposed of, resulting in significant waste and cost [12]. Furthermore, the increasing use of disposable plastic medical and personal protective equipment (PPE) in healthcare systems significantly contributes to the global carbon footprint [13].

In the healthcare sector, the environmental footprint is dominated by procedure-oriented specialties such as surgery and endoscopy [14]. Traditional reusable flexible endoscopes are technologically advanced and expensive equipment that require repeated sterilization and periodic repair. These issues have led to the development of single-use (SU) flexible endoscopes that are disposed of after each case. Although this may have some advantages, the environmental impact of such technology is yet to be fully determined [15].

Healthcare professionals and policymakers are increasingly incorporating environmental considerations into their decision-making processes [16]. SU products are defined as products disposed of after one use, whereas reusable goods can be used at least twice and in the case of Multiple-use (MU) endoscopes, many times. A recent study suggests that one particular hospital site conducts 14,000 endoscopies per year, and estimated the expected lifetime of endoscopes to be around 5–10 years [17]. However, it should be noted that hospitals will typically have multiple endoscopes per site, so getting an exact number of procedures per endoscope over the course of its lifetime is challenging.

SU endoscopes may have some advantages over reusable devices; however, their environmental footprint has been widely criticized yet is mostly unknown. Although MU endoscopes appear to reduce medical waste, it is hypothesized that sterilization may offset this benefit. Sterilization, which must be conducted to guarantee the safety and efficacy of these devices for reuse, requires energy, water, and chemicals. These resources add to the healthcare sector’s negative environmental impact and have the potential to counteract waste reduction achieved through device reuse [18].

The aim of this study is to review and synthesize the existing literature on the life cycle assessment (LCA) of SU and MU endoscopes. Specifically, this review aims to explore how different research approaches define and delineate the life cycle stages, system boundaries, and functional units for SU and MU endoscopes, as well as to identify the primary environmental impacts and hotspots reported in these comparative studies. A clear understanding of these methodological approaches from literature review is crucial for identifying best practices, recognizing existing data gaps, and guiding the development of more robust and comprehensive future LCA studies in the healthcare sector. Understanding these methodological approaches and the specific environmental outcomes across the endoscopes’ life cycles is crucial for healthcare professionals and policymakers to make informed decisions regarding sustainable practices and the adoption of medical technologies, ensuring high-quality healthcare while minimizing environmental impact.

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 details the research methods, including an introduction to the databases and keywords used for article searching, the inclusion criteria, and the study selection process. Section 3 then presents the results of our literature search and study selection, visually represented in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram [19], and further provides a detailed analysis and review of the final selected studies, specifically examining them through the lens of the different stages of the SU and MU life cycle and aligning with the primary objectives of this research. Finally, Section 4 outlines the conclusions drawn from this research and proposes a future research agenda. Specifically, the research agenda identifies the difficulties currently faced by decision makers in this space trying to use environmental analysis as a tool, and gives clear indications as to the direction of future research in this space.

2. Materials and Methods

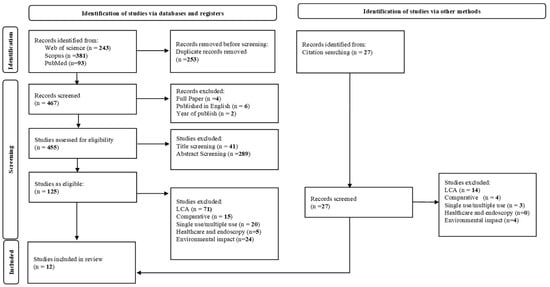

A review was conducted by applying the PRISMA 2020 framework, which was specifically developed for reviews and meta-analysis of clinical data. The PRISMA flow diagram illustrates the flow of information throughout the distinct phases of the review. It outlines the number of records identified, included, and excluded as well as the reasons for exclusion. Various templates are available based on the type of review and the sources used to identify studies [19]. The PRISMA flow diagram was used in three main steps: identification, screening, and inclusion. The following subsections discuss the search strategy, inclusion criteria, and the general and specific data items used for reviewing the final selected articles.

2.1. Search Strategy

Three main databases, Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed—were selected for this study. These databases were carefully chosen because of their comprehensive coverage and relevance to the primary objectives of this research. Searches were conducted across the Title, Abstract, and Keywords fields using the following keywords and queries. The Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” were applied to combine search terms in the search strategies for the selected databases. In addition to the records identified through the keyword searches, further studies were considered and added through an iterative citation search process during the full-text review of studies. The last searches for all databases were conducted in October 2025.

Title/Abstract/Keywords = (“Single-use” OR “Expendable” OR “Disposable” OR “Non-reusable” OR “Throwaway” OR “Use-and-throw” OR “One-time use” OR “One-off” OR “Non-renewable” OR “Multiple-use” OR “Multiple-purpose use” OR “Reusable” OR “Recyclable” OR “Washable” OR “Long-lasting” OR “Durable” OR “Replicable” OR “Resealable” OR “Refold able” OR “Single-use versus Multiple-use” OR “Single-use VS Multiple-use” OR “Single-use Multiple-use comparison”) AND Title/Abstract/Keywords = (“Endoscope” OR “Endoscopy” OR “Gastroenterology”.

AND Title/Abstract/Keywords = (“Life-cycle assessment” OR “Life cycle assessment” OR “Lifecycle assessment” OR “Life-cycle analysis” OR LCA OR “Life cycle analysis” OR “Cradle-to-grave analysis” OR “Life cycle inventory” OR “Life cycle evaluation” OR “Life cycle sustainability assessment” OR “Life cycle impact assessment” OR “Product life cycle assessment” OR “Environmental life cycle assessment” OR “Eco-balance analysis” OR “Environmental impact” OR “Sustainability assessment” OR “Circular economy” OR “Circular design” OR “Ecological impact” OR “Carbon cost” OR “Carbon footprint” OR “ CO2 footprint” OR “Carbon emission” OR “Eco-responsible” OR “Environmental-footprint”).

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Two main sets of inclusion criteria were considered for this study. The first set included inclusion criteria concerning the nature of the publications. These criteria include full-text articles/manuscripts, research published in English, and research published between 1 January 2010, and 30 June 2025. Given that few articles based on the keywords and queries used were published before 2010, this literature review focuses on studies from 2010 onward. Older studies may not be relevant because healthcare has evolved significantly in recent years. Advances in medical technology, changes in infrastructure, and shifts in energy sources mean that studies conducted prior to 2010 may not comprehensively represent the current healthcare landscape. The second set of inclusion criteria, which can be considered as specific criteria included the performance of an LCA and examining SU and/or MU endoscopes, taking the environmental impact into account.

2.3. Reviewing Final Selected Articles

To review the final selected articles, two main categories of data items were considered. The first category comprised general data items, which included general information about the articles, such as title, authors, publication years, countries/regions, research methodology, and titles of the journals. The second category of data items consisted of specific elements of LCA, such as the defined goal and scope, product category, Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) method, and comparisons from an environmental perspective.

3. Results

Figure 1 presents an overview of the search results, formatted as a PRISMA flowchart. The search in the three databases identified a total of 717 records. After removing duplicate records and applying first set of inclusion criteria, including full paper, published in English, and year of publication, 452 studies remained for title and abstract screening. Following this step, 330 studies were excluded, leaving 125 studies eligible for full-text screening. At this stage, 115 studies were excluded based on the specific inclusion criteria resulting in 10 studies for a detailed full-text review. Additionally, 27 studies were identified as possible inclusions from checking reference lists of these studies. After applying the specific inclusion criteria, two studies met these criteria and was added to the 10 studies identified via a database search. Consequently, 12 studies were selected for a detailed review based on general and specific data items.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram of Study Selection Process.

3.1. Single-Use (SU) Versus Multiple-Use (MU) Endoscopes

Table 1 provides a comprehensive summary of the 12 key studies included in this review, organized by the specific SU and MU endoscope product categories examined in each. This table delineates the diverse range of endoscope types, such as flexible cystoscopes, ureteroscopes, duodenoscopes, and bronchoscopes, that were the focus of the environmental impact assessments in the selected literature. Understanding the product categories assessed in each study is crucial for contextualizing their findings and identifying specific areas of focus within the broader field of endoscope life cycle assessment.

Table 1.

Summary of 12 Final Key Studies on SU&MU Product Categories.

3.2. SU and MU Endoscope Life Cycle

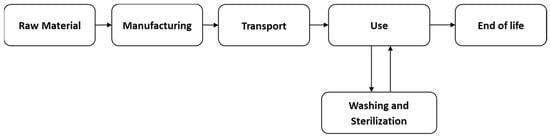

From the selected 12 journal articles, an in-depth review of the upstream and downstream stages of the life cycle of SU and MU endoscopes was conducted. These stages can be broadly categorized into several stages, including manufacturing, transportation, usage processes, washing and sterilization, and waste management practices (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Exploring each of these steps provides valuable insights into the assessment of the environmental impacts of endoscopic practices.

Figure 2.

MU Endoscope Life Cycle.

Figure 3.

SU Endoscope Life Cycle.

Each step of the SU and MU endoscope life cycle includes the various inputs and outputs required to perform the LCA. The inputs may include resources, such as raw materials, energy, water, and chemicals used at various stages of the SU and MU endoscope life cycle. Additionally, outputs include greenhouse gas emissions to air, water, and land, as well as the waste generated at each stage of the SU and MU life cycles of endoscopes. Based on a review of these studies, it can be noted that the authors often considered only a subset of the possible inputs and outputs. This selective focus may limit the comprehensiveness of the findings and suggests the need for a more comprehensive approach.

According to seven of these studies [2,10,20,22,24,25,26] examined both SU and MU endoscopes across stages like raw materials and manufacturing. Transportation was evaluated for both endoscope types by [2,10,25,26,27]. When it comes to the usage stage, eight studies [2,5,10,20,23,24,25,26] examined both endoscope types. The washing and sterilization stage, relevant only for MU endoscopes, appeared in nine studies [2,5,9,10,21,22,24,25,26]. Finally, six studies [5,10,24,25,26,27] looked at waste management for both SU and MU endoscopes.

4. Discussion

4.1. Raw Materials and Manufacturing

Raw materials and manufacturing processes are consistently identified as critical factors in the LCA of endoscopes, though their specific importance varies between SU and MU devices and across different study methodologies. For SU endoscopes, manufacturing is frequently cited as the primary contributor to their environmental and health impacts. For instance, the manufacture of SU duodenoscopes (SUDs) is responsible for a significant majority, 91% to 96% of their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [26,28]. Similarly, the production stage for SU gastroscopes accounts for 56% of their carbon footprint and 84% of water depletion [29], and for SU flexible ureterorenoscopes (fURS), the production phase accounts for most of the impact [25]. An average across various SU medical devices shows manufacturing contributing 68 ± 14% to the life-cycle process [27]. These devices are typically composed predominantly of plastics (e.g., 74% for SU gastroscopes, 95.6% for SU cystoscopes, and 96% for SU bronchoscopes) [9,24,29]. However, obtaining detailed material composition data for endoscopes is challenging, as it is often scarce and not publicly available, leading studies to rely on estimations or surrogate data [13,28]. This lack of transparency means that while individual studies highlight the significance of manufacturing for the specific SU devices they examine, a comprehensive, consistently derived analysis of raw materials and manufacturing across all endoscope types remains limited by data availability and methodological assumptions.

The role of raw materials and manufacturing in MU endoscopes presents a more nuanced picture, often amortized over many uses, yet still important. While initial manufacturing for SU devices can have a higher absolute carbon footprint per device (e.g., a SU duodenoscope’s lifetime carbon footprint of 152 kg CO2eq vs. SU duodenoscopes at 10,512–12,640 kg CO2eq over the same lifetime) [13] this impact becomes very low on a per-case basis due to repeated use (e.g., 0.013 kg CO2 for a MU cystoscope compared to 1.34 kg CO2 for a SU one) [21]. MU devices, such as duodenoscopes, are often substantially heavier and primarily composed of metal alloys (95%), whose production is energy-intensive but offers higher recycling potential [13]. In contrast, certain plastics used in SU devices, such as polytetrafluoroethylene, have significantly higher environmental impacts per kilogram than some metal alloys [13]. For MU devices, the reprocessing phase typically dominates the per-case environmental footprint, accounting for 84% of total emissions for MU duodenoscopes and 45% of the carbon footprint for MU gastroscopes [13,29]. Critically, some studies explicitly exclude the manufacturing phase for MU devices or limit their scope, potentially underestimating their overall environmental footprint and complicating comprehensive comparisons [2,18]. While individual papers consistently emphasize the importance of manufacturing and material choices, a unified framework with transparent, disaggregated data on raw materials and manufacturing for all endoscope categories is not comprehensively presented in the existing literature, thus hindering a complete understanding and direct comparison of this critical life cycle stage across the board [13,27].

4.2. Transportation

The transportation stage is an imperative consideration in the life cycle assessment (LCA) of endoscopes due to the globalized nature of medical device supply chains and its direct contribution to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [21,27,30]. Medical products often traverse vast distances, making the mode and distance of transport directly relevant to their environmental footprint [13,27]. For SU endoscopes, transportation (often termed delivery or distribution) is identified as a contributing factor, though its significance varies considerably across studies. Some analyses indicate that distribution accounts for an average of 20% (with a standard deviation of 12%) of the carbon footprint for SU devices, making it the second-largest contributor after manufacturing [27]. This suggests a substantial impact when considered across the entire product lifecycle. However, other studies present a more modest contribution; for SU duodenoscopes (SUDs), transportation and packaging might account for as little as 3% to 5% of GHG emissions, with manufacturing being overwhelmingly dominant at 91% to 96% [26,28]. Similarly, transport for SU cystoscopes was found to be a minor element, contributing only 0.049 kg CO2per case, the smallest component of its total carbon footprint [21]. For SU flexible ureterorenoscopes (fURS), delivery amounted to a small fraction of the overall health impact [25]. This variability in reported significance highlights a critical analytical challenge, as methodological differences, scope boundaries, and data estimations can lead to inconsistent findings regarding transportation’s actual environmental burden for SU devices.

For MU endoscopes, the direct impact of device transportation is generally reported as negligible or is explicitly excluded from some analyses due to data limitations. For instance, studies on MU flexible cystoscopes often do not account for raw material extraction, production, assembly, and distribution due to a lack of specific data from companies [2]. When reported, such as for MU fURS, the delivery phase is shown to have a minuscule carbon footprint per use [25]. The imperative to accurately assess transportation aligns with broader calls for harmonized LCA methodologies, such as those consistent with ISO 14040/44 standards [31,32] and the Product Environmental Footprint (PEF) guide [2,27,29]. However, the existing literature frequently acknowledges an absence of a widely accepted or standardised methodology for evaluation of environmental impact specific to medical devices, making product comparisons challenging and unreliable [27]. This extends to the transportation stage, where reliance on online sources or surrogate data, as noted in some studies, underscores the need for greater transparency and consistency in data disclosure from manufacturers [13,30]. Ultimately, while transportation is an integral part of the supply chain, its contribution is often overshadowed by manufacturing (for SU devices) and reprocessing (for MU devices), and its precise impact is frequently limited by data availability and methodological inconsistencies across the current body of research.

4.3. Use Phase

The use phase is often a complex stage within the LCA of endoscopes, demanding critical analysis to accurately quantify environmental impacts and ensure adherence to standardized methodologies, such as ISO 14040/44 [2,25,27]. For SU endoscopes, the direct use phase (e.g., electricity during a procedure) is generally reported as having a comparatively low impact, often overshadowed by manufacturing. For example, the overall use-phase for SU medical devices contributes an average of 2 ± 4% to the life-cycle carbon footprint, significantly less than manufacturing [27]. In the case of SU flexible ureterorenoscopes (fURS), delivery and use collectively constituted only a small fraction of the total potential health impact, with the direct use portion contributing 0.14 kg CO2eq per use [25]. Similarly, for SU gastroscopes, the main environmental impacts are driven by production [29]. However, the precise contribution of the use phase for SU devices can be difficult to discern or compare across studies due to varying methodologies. Some studies on SU devices, such as flexible cystoscopes, explicitly detail manufacturing, packaging, sterilization before shipping, transportation, and solid waste but do not disaggregate a distinct use-phase contribution, implicitly assuming it is negligible or subsumed within other categories [24]. Critically, many analyses, including those for SU gastroscopes and general endoscopic procedures, deliberately exclude significant use-related aspects like patient and staff travel, energy consumption for heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) in the operating room, or other ancillary supplies, under the assumption that these factors are identical across both SU and MU strategies [5,25,29]. This methodological limitation hinders a complete and comprehensive understanding of the use phase for SU devices and its actual environmental burden, underscoring the imperative for more consistently defined and reported LCA boundaries in future research.

In contrast, the use phase for MU endoscopes is dominated by the energy and resource-intensive reprocessing and decontamination processes, making it a significant environmental hotspot that demands thorough assessment [23]. For MU duodenoscopes, electricity use alone contributes a substantial 62% of GHG emissions, with cleaning and disinfection accounting for an additional 26% [28]. Similarly, for MU flexible cystoscopes, reprocessing is identified as the primary contributor to per-case carbon costs, with sterilization generating 3.5 kg CO2 per case, vastly exceeding manufacturing’s 0.013 kg CO2 [21,33]. Reprocessing involves considerable energy and water consumption, often up to 165 L per cleaning cycle, in addition to the use of chemicals and personal protective equipment (PPE) [21,23]. For MU gastroscopes, decontamination accounts for 45% of the carbon footprint and over 90% of water consumption [29]. However, current studies often fall short of providing a truly exhaustive use phase analysis for MU devices. Many explicitly exclude aspects like the carbon footprint for repairs and maintenance, or the environmental impact of detergents used in reprocessing, citing data unavailability or perceived insignificance [21,33]. Furthermore, some LCAs for MU devices, such as flexible cystoscopes and bronchoscopes, limit their scope to reprocessing only, omitting manufacturing and disposal of the devices themselves, which, despite amortization over many uses, can underestimate the total environmental footprint [2,9]. These methodological inconsistencies and incomplete data disclosures present a critical challenge to a holistic comparative analysis between SU and RU endoscopes.

4.4. Washing and Sterilization

The washing and sterilization phase, often referred to as reprocessing, represents a critical and environmentally significant stage primarily for MU endoscopes within their life cycle, demanding robust and comprehensive LCAs to accurately determine their environmental burden [23]. For these devices, reprocessing is consistently identified as a major environmental hotspot, contributing substantially to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, energy consumption, and water usage [9,24,25,28,29]. For instance, cleaning and disinfection processes for MU duodenoscopes can account for 26% of GHG emissions, with electricity during the procedure itself contributing an even larger 62% [26,28]. Similarly, reprocessing is the primary contributor to per-case carbon costs for MU flexible cystoscopes, with sterilization generating 3.5 kg CO2 per case using one type of reprocessing, significantly more than the manufacturing cost of 0.013 kg CO2 per case when amortized over lifetime uses [24,30]. This energy consumption can be substantial, with one reprocessing machine using 10.5 kW per cycle, equating to 10.5 kg CO2 per cycle for three cystoscopes [21]. Water usage is also considerable, with some machines consuming 68 L per cycle for cystoscopes and up to 165 L per cleaning cycle for ureterorenoscopes and duodenoscopes [20,21,24]. For MU gastroscopes, decontamination accounts for 45% of the carbon footprint and over 90% of water consumption [29]. Chemicals and personal protective equipment (PPE) further add to the environmental impact; for example, PPE for reprocessing a MU cystoscope could amount to 1176 kg over its lifetime, and reprocessing chemicals like peracetic acid can have toxic effects on aquatic organisms and healthcare workers [2,24]. Critically, studies often face limitations, with some LCAs on MU cystoscopes specifically excluding the environmental impact of detergents due to modeling uncertainties or repairs and maintenance, potentially underestimating the total burden of this phase [24,30]. Furthermore, while the explicit scope of some studies on MU bronchoscopes is limited to cleaning and sterilization, excluding their manufacturing and disposal, this can lead to a conservative and potentially incomplete assessment of the overall environmental impact for MU devices [9]. These methodological inconsistencies highlight the challenge in drawing truly comprehensive comparisons.

4.5. Waste Management

From a critical analysis perspective, the waste management and end-of-life stage for MU endoscopes presents a nuanced environmental profile. While the actual disposal of the MU device itself contributes to a comparatively low environmental impact on a per-case basis, as its burden is amortized over its many uses [23,24,26] the ongoing reprocessing phase is a significant generator of waste [26]. For instance, the solid waste from a MU cystoscope contributes only 0.0001 kg CO2 per case when amortized over its lifetime, with approximately 0.57 kg going to landfill over 3920 uses [24]. Similarly, MU flexible ureterorenoscopes (fURS) contribute 7.6 × 10−2 kg CO2eq per use at the disposal stage [25]. However, the reprocessing of these devices involves substantial consumption of personal protective equipment (PPE), which can amount to 1176 kg over a cystoscope’s lifetime [24]. Repackaging materials also contribute to landfill waste [21,24].

In contrast, SU endoscopes entirely shift the waste burden to their disposal after a single procedure, leading to a dramatically increased volume and mass of solid waste per case [5,26]. Each SU endoscopy procedure generates approximately 2.1 kg of disposable waste, increasing to 2.4 kg when considering the reprocessing waste avoided by MU devices [5]. For SU fURS, the disposal stage alone contributes 1.2 kg CO2eq per use [25]. If all 18 million annual endoscopic procedures in the USA were performed with SU endoscopes, an estimated 38,000 metric tons of waste would be generated, an amount equivalent to 25,000 passenger cars or enough to cover 117 soccer fields to a depth of 1 m. This widespread adoption is projected to quadruple the net waste mass that would otherwise come from MU reprocessing and device disposal [5,26]. A substantial portion of SU waste, particularly plastic components, is disposed of through incineration [5,13] a process mandated for biomedical waste [25,26]. Incineration generates significant greenhouse gas emissions (e.g., 1.1 kg CO2eq/kg for nonplastics and 3–6 kg CO2eq/kg for plastics) [13], releases more greenhouse gases than coal plants, and produces toxic byproducts and fine particles. For these reasons, medical waste incineration is deemed not an environmentally sustainable practice [5]. While some SU manufacturers may dismantle and recycle metal or electronic components, the overall proportion of waste that is recycled remains low (10%) [5], and for fURS, recycling would not noticeably change the results [25]. The current linear economy model for SU devices, where they are not typically returned, refurbished, or remanufactured, leads to an ever increasing amount of recyclable waste [5,26]. Therefore, the seeming elimination of reprocessing waste by SU devices is merely a transfer of the environmental impact to a significantly larger and more environmentally problematic solid waste stream at the disposal stage [5,26].

4.6. Reviewing the Defined System Boundary

As elaborated above, the life cycle of SU and MU endoscopes comprises five main stages, including manufacturing, transportation, the endoscopy, washing and sterilization, and waste management practices. As mentioned above, various studies defined different boundaries for their environmental assessment of endoscopes. Some studies have focused on specific stages of the endoscope’s life cycle, such as manufacturing or the end-of-life option, while others have adopted a cradle-to-grave approach, considering all stages from manufacturing to end-of-life.

Table 2 outlines the scope of analysis for each of the included studies by detailing their defined system boundaries and the life cycle stages considered for both SU and MU endoscopes. This table specifically indicates which stages—including raw material, manufacturing, transportation, usage, washing and sterilization, and waste management—were encompassed within each study’s assessment. Understanding these system boundaries is critical for evaluating the comprehensiveness and comparability of the LCA results presented in the literature, as variations in scope can significantly influence reported environmental impacts. As a consequence of this approach, with differing definitions of system boundaries, goal and scope of research studies as well as varying degrees of compliance with ISO 14040/44 make it practically impossible to compare the results across studies.

Table 2.

System Boundaries and Analytical Units of Reviewed Studies.

4.7. LCA of SU vs. MU Endoscopes

LCA is one of the most effective tools available for quantitatively analysing the environmental impact of healthcare products [2]. By considering a cradle-to-grave approach, LCA allows a holistic understanding of the environmental consequences of healthcare products. This enables decision makers to determine areas for improvement, prioritize interventions, and develop targeted strategies to minimize environmental impacts. In addition, LCA enables a comparison of different scenarios and alternatives. However, the deployment of LCA methods in the healthcare sector is still under development [2].

Table 3 presents an expanded summary of the methodological characteristics of the 12 reviewed studies from a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) perspective. In accordance with ISO 14040/44, the table includes detailed information on the endoscope type or study focus, goal and scope/system boundaries, functional unit, LCI database and version, LCIA method and software used, allocation method(s), assumptions on electricity mix or energy source (when available), and the presence of any sensitivity or uncertainty analysis. This expanded structure enables a more comprehensive and transparent appraisal of the methodological quality of each study. It allows for the identification of similarities and differences in system boundaries, data sources, modelling assumptions, and impact assessment methods, all of which influence the comparability and robustness of results. Where certain methodological elements were not reported in the original publications, these have been indicated as Not Reported (NR) in the table. As is evident from the table, there are too many variations within the studies to make the results comparable.

Table 3.

Summary of 12 Final Key Studies on SU and MU From LCA Lens.

However, in order to understand general trends and the primary comparative findings from the reviewed studies, the conclusions regarding the environmental performance of SU versus multiple-use (MU) endoscopes are summarized in Table 4. This table summarizes the key conclusions reached by each study concerning the environmental impact trade-offs between these two endoscope types. While the detailed qualitative and quantitative aspects of these comparisons are elaborated in the preceding discussion within the ‘LCA of SU vs. MU Endoscopes’ section, Table 4 serves as a quick reference to the overall environmental assessment outcomes reported in the literature.

Table 4.

Comparison of SU and MU.

5. Conclusions

This study conducted a comprehensive literature review of 12 studies to analyze the life cycle assessment (LCA) process and compare SU and MU endoscopes, considering their entire life cycle from manufacturing to the end-of-life stage through an environmental impact lens.

The review reveals key insights into the environmental impacts at each life cycle stage of SU and MU endoscopes, showing notable differences and similarities between the two. Furthermore, this study identifies significant gaps and inconsistencies in the literature concerning the use of LCA to assess these environmental impacts.

Based on our findings, only three articles have conducted a comparative Investigation of all stages of the life cycle of SU and MU endoscopes. Even then, those studies have used different impact assessment methodologies and are studying different pieces of equipment, so only general comparisons about the trends identified can be reasonably made.

Each stage of the life cycle of SU and MU endoscopes can have significant environmental effects. Therefore, future research in this space should use a cradle-to-grave approach by considering all life cycle stages compliant with ISO 14040/44, PEF or equivalent international standards can lead to better, comparable and more reliable results, providing policymakers and decision-makers in the health sector with a clearer understanding of the environmental implications of choosing between SU and MU endoscopes.

Future research should improve environmental impact comparisons between SU and MU endoscopes using LCA. Researchers can consider the impact of technological developments on the environmental impact of SU and MU endoscopes at different stages of their lifespan, including materials, manufacturing methods, washing and sterilization, and waste management. Additionally, analyzing the environmental impact of these two options of endoscopes in various regions will help demonstrate how end-of-life practices, accessibility to different resources, sources of energy used, and local regulations affect the overall life cycle of SU and MU endoscopes. For a comprehensive LCA, it is also important to include economic and social factors, such as cost analysis and potential health impacts, in environmental assessment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. and S.R.C.; methodology, S.R.C.; validation, S.R.C.; formal analysis, M.A. and S.R.C.; investigation, M.A.; resources, M.A. and S.R.C.; data curation, M.A. and S.R.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.; writing—review and editing, M.A. and S.R.C.; visualization, M.A.; supervision, S.R.C.; project administration, S.R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to thank the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) for funding this research (NIHR 152311).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. The data featured in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

On behalf of the SUMU Endo project group: Lazaros Andronis, Ramesh P. Arasaradnam, Anna Brown, Yen-Fu Chen, Anjan Dhar, Julia Gauly, Amy Grove, Bu Hayee, Yufei Jiang, Thomas Matthews, Violet Matthews, Poonam Parmar, Shaji Sebastian, Natalie Tyldesley-Marshall, Norman Waugh and Mandana Zanganeh.

References

- Misrai, V.; Rijo, E.; Cottenceau, J.B.; Zorn, K.C.; Enikeev, D.; Elterman, D.; Bhojani, N.; De La Taille, A.; Herrmann, T.R.W.; Robert, G.; et al. A Standardized Method for Estimating the Carbon Footprint of Disposable Minimally Invasive Surgical Devices: Application in Transurethral Prostate Surgery. Ann. Surg. Open 2021, 2, e094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baboudjian, M.; Pradere, B.; Martin, N.; Gondran-Tellier, B.; Angerri, O.; Boucheron, T.; Bastide, C.; Emiliani, E.; Misrai, V.; Breda, A.; et al. Life Cycle Assessment of Reusable and Disposable Cystoscopes: A Path to Greener Urological Procedures. Eur. Urol. Focus 2023, 9, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayman, R.V. Comment on: “The Carbon Footprint of Single-Use Flexible Cystoscopes Compared with Reusable Cystoscopes” by D. Hogan et al. J. Endourol. 2022, 36, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karliner, J.; Slotterback, S.; Boyd, R.; Ashby, B.; Steele, K. Health Care’s Climate Footprint, How the Health Sector Contributes to the Global Climate Crisis and Opportunities for Action; Health Care Without Harm (HCWH): Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Namburar, S.; von Renteln, D.; Damianos, J.; Bradish, L.; Barrett, J.; Aguilera-Fish, A.; Cushman-Roisin, B.; Pohl, H. Estimating the environmental impact of disposable endoscopic equipment and endoscopes. Gut 2022, 71, 1326–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanfilippo, F.; Zeidan, A.; Hasanin, A. Disposable versus reusable medical devices and carbon footprint: Old is gold. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 2023, 42, 101285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Health care’s climate footprint: The health sector contribution and opportunities for action. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, ckaa165. 843. [Google Scholar]

- Grimmond, T.R.; Bright, A.; Cadman, J.; Dixon, J.; Ludditt, S.; Robinson, C.; Topping, C. Before/after intervention study to determine impact on life-cycle carbon footprint of converting from single-use to reusable sharps containers in 40 UK NHS trusts. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e046200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, B.L.; Grüttner, H. Comparative study on environmental impacts of reusable and single-use bronchoscopes. Am. J. Environ. Prot. 2018, 7, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, L.V.; Agrawal, D.; Skole, K.S.; Crockett, S.D.; Shimpi, R.A.; von Renteln, D.; Pohl, H. Meeting the environmental challenges of endoscopy: A pathway from strategy to implementation. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2023, 98, 881–888.e881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decroly, G.; Hassen, R.B.; Achten, W.M.J.; Grimaldi, D.; Gaspard, N.; Deviere, J.; Delchambre, A.; Nonclercq, A. Strong Sustainability of Medical Technologies: A Medical Taboo? The Case of Disposable Endoscopes. In Proceedings of the 2023 45th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Sydney, Australia, 24–27 July 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renton, D.; Denk, P.; Varban, O. Reprocessed single-use devices in laparoscopy: Assessment of cost, environmental impact, and patient safety. Surg. Endosc. 2018, 32, 4310–4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Muñoz, P.; Martín-Cabezuelo, R.; Lorenzo-Zúñiga, V.; Vilariño-Feltrer, G.; Tort-Ausina, I.; Vidaurre, A.; Beltran, V.P. Life cycle assessment of routinely used endoscopic instruments and simple intervention to reduce our environmental impact. Gut 2023, 72, 1692–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darak, H.; Giri, S.; Sundaram, S. Disposable duodenoscopes in the era of climate change—A global perspective. J. Gastrointest. Infect. 2022, 12, 011–017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Ong, A.; Juliebø-Jones, P.; Davis, N.F.; Skolarikos, A.; Somani, B. Single-Use Ureteroscopy and Environmental Footprint: Review of Current Evidence. Curr. Urol. Rep. 2023, 24, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, D.; Tang, Z. Sustainability of Single-Use Endoscopes. Tech. Innov. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2021, 23, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanganeh, M.; Jiang, Y.; Waugh, N.; Hayee, B.; Sebastian, S.; Gillespie, T.; Arasaradnam, R.P.; Andronis, L. Cost of reusable gastrointestinal endoscopes to the NHS: Findings from a micro-costing study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2025, 12, e002013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baboudjian, M.; Bastide, C.; Lechevallier, E. Comment on ‘environmental impact of single-use and reusable flexible cystoscopes’. BJU Int. 2023, 131, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br. Med. J. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, N.F.; McGrath, S.; Quinlan, M.; Jack, G.; Lawrentschuk, N.; Bolton, D.M. Carbon Footprint in Flexible Ureteroscopy: A Comparative Study on the Environmental Impact of Reusable and Single-Use Ureteroscopes. J. Endourol. 2018, 32, 214–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, D.; Rauf, H.; Kinnear, N.; Hennessey, D.B. The Carbon Footprint of Single-Use Flexible Cystoscopes Compared with Reusable Cystoscopes. J. Endourol. 2022, 36, 1460–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, N.N.T.; Hernandez, L.V.; Vakil, N.; Guda, N.; Patnode, C.; Jolliet, O. Environmental and health outcomes of single-use versus reusable duodenoscopes. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2022, 96, 1002–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddhi, S.; Buttery, L.; Teahon, M.; Trujillo, J.A.; Campbell, A.; Campbell, D. Life Cycle Analysis—Single Use Scopes vs. Reusable Scopes: A Framework for Sustainable Endoscopy. Gut 2022, 71, A15–A16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemble, J.P.; Winoker, J.S.; Patel, S.H.; Su, Z.T.; Matlaga, B.R.; Potretzke, A.M.; Koo, K. Environmental impact of single-use and reusable flexible cystoscopes. BJU Int. 2023, 131, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thone, M.; Lask, J.; Hennenlotter, J.; Saar, M.; Tsaur, I.; Stenzl, A.; Rausch, S. Potential impacts to human health from climate change: A comparative life-cycle assessment of single-use versus reusable devices flexible ureteroscopes. Urolithiasis 2024, 52, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabi, Z.; Tang, R.S.Y.; Sundaram, S.; Lakhtakia, S.; Reddy, D.N. Single-use accessories and endoscopes in the era of sustainability and climate change—A balancing act. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 39, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizan, C.; Bhutta, M.F. Policy Brief: Reducing the Environmental Impact of Medical Devices Adopted for Use in the NHS; Brighton and Sussex Medical School: Brighton, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Velly, R. When Competition Meets Sustainability: The Introduction of Sustainable Development in Public Procurement Law. Droit Soc. 2022, 110, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pioche, M.; Poh, H.; Neves, J.A.C.; Laporte, A.; Mochet, M.; Rivory, J.; Grau, R.; Jacques, J.; Grinberg, D.; Boube, M.; et al. Environmental impact of single-use versus reusable gastroscopes. Gut 2024, 73, 1816–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, D.; Hennessey, D.B. Response to Rizan et al.: “The Carbon Footprint of Single-Use Flexible Cystoscopes Compared with Reusable Cystoscopes”—Clarification of Methods Due to Apparent Misinterpretation. J. Endourol. 2023, 37, 1145–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006+A1:2020; Environmental Management. Life Cycle Assessment. Principles and Framework. ISO (the International Organization for Standardization): Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- ISO 14044:2006+A2:2020; Environmental Management. Life Cycle Assessment. Requirements and Guidelines. ISO (the International Organization for Standardization): Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Kemble, J.; Koo, K. Response to comment on ‘Environmental impact of single-use and reusable flexible cystoscopes’. BJU Int. 2023, 131, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).