Abstract

The lack of research on organisational efforts in managing work–life conflict across different working contexts is considered a major barrier to sustainable employment. In response, this study examines how organisational segmentation strategies can help reduce burnout and improve sustainable work–life balance by minimising work–life conflict among both teleworkers and office workers. A two-wave survey, conducted six months apart, involved 359 white-collar employees from various industries. The results show that segmentation supplies—defined as the extent to which organisations facilitate maintaining boundaries between work and personal life—lead to decreased work–life conflict for both teleworkers and office workers. Additionally, the findings indicate that higher levels of work–life conflict are associated with a reduced appreciation for organisational efforts to support the management of professional and personal life demands among teleworkers. Still, this effect was not observed for office workers. Ultimately, work–life conflict was found to increase burnout and reduce work–life balance, specifically among teleworkers, highlighting the importance of organisational initiatives aimed at preventing work–life conflict to enhance their well-being.

1. Introduction

Despite the evolving nature of work life and the growing diversity and complexity of roles in personal life, the two areas—work and family responsibilities—remain some of the most significant aspects of adult life. Interest in the intersection between these two roles has surged in recent decades, both in academia and public discourse. Navigating numerous demands across professional and private life domains, which often overlap or are incompatible, is known to lead to a work–life conflict (WLC) [1]. The interest in WLC has intensified with the rise of telework, as it integrates work within the nonwork environment, significantly impacting how different roles interact with one another [2].

The negative effects of work–life conflict (WLC) on employee burnout [3], family and work well-being [4], and work–life balance [5] have led to significant efforts to understand its causes. Notably, researchers and policymakers alike consider work–life balance a critical prerequisite for a sustainable workforce and personal well-being [6]. However, most research has concentrated on individual-focused solutions, such as detachment [7], managing the boundaries between work and personal life [8], or self-regulation [9]. In contrast, there has been considerably less attention paid to the organisational resources and contexts that can either support or hinder individual efforts in managing work and personal demands (e.g., [10]). Furthermore, very little is known about the role of organisations in addressing WLC among teleworkers. Paradoxically, while for employees, one of the primary motives for teleworking is the greater ease of managing competing work and family responsibilities [11], existing research suggests that telework might not only facilitate compatibility between work and family (e.g., [12]) but also lead to more work–family conflict (e.g., [13]).

Importantly, remote work has been a crucial strategy for maintaining economies and production throughout the COVID-19 pandemic [14]. It is expected that remote working will continue under favourable economic conditions, as suggested by Eurofound [15]. Moreover, telework is a modern work design practice that could support a sustainable workforce and workplace development, in accordance with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 8 [16]. Nevertheless, the successful implementation of remote work is likely to depend on organisational practices, such as technological readiness, communication, and investment in personnel training [15]. Considering that WLC antecedents among teleworkers are mostly researched as individual factors, research on its organisational antecedents is also greatly needed.

To address this gap, we posit that organisational segmentation supplies—defined as the degree to which organisations support maintaining boundaries between work and personal life—serve as a valuable resource that helps reduce WLC, which in turn lowers burnout and enhances work–life balance.

With this study, we make several contributions which are both timely and relevant. Firstly, drawing on the conservation of resources (COR) theory [17,18] and boundary and border theories [19,20], we demonstrate that segmentation supplies predict lower WLC over time among both office workers and teleworkers. In this way, we contribute empirical findings to the existing equivocal research (e.g., [21]) and enhance the robustness of the existing research, which is mainly cross-sectional (e.g., [22]). Notably, the relationship between segmentation supplies and WLC was reciprocal for teleworkers but not for office workers. This suggests that failing to manage WLC may hinder perceptions of organisational efforts to support boundary maintenance between professional and personal life.

Second, we investigate the temporal relationships between WLC and work–life balance, thereby answering the call of Allen and French [2] for longitudinal research in the work–family area. While WLC was envisioned over ten years ago as a precursor to work–life balance [23], there is still a lack of empirical evidence regarding their connections, largely due to significant differences in how balance is defined. We therefore employ the most recent and exhaustive conceptualisation of work–life balance provided by Casper et al. [24] and demonstrate the longitudinal relationship between WLC, affective, involvement, and effectiveness balance, thereby providing a more nuanced understanding of how WLC is connected to various aspects of work and life interaction, complementing existing research.

Third, we contribute to the existing literature by demonstrating the differential effects of organisational segmentation supplies on burnout and work–life balance through work–life conflict (WLC) for teleworkers compared to office workers. More precisely, using a two-wave design study, we demonstrate that while segmentation supplies can lower WLC for both teleworkers and on-site workers, the impact of WLC on employee well-being is observed only among teleworkers. We thereby respond to the recent invitation by Allen and French [2] to re-examine what is known about flexible work and work–family experiences, thereby advancing work–life research.

Finally, our study offers practical implications for the importance of providing office workers and, above all, teleworkers with actions and resources to support their ability to maintain boundaries between work and personal life, thereby ensuring sustainable modern work design.

2. Theory and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Work–Life Conflict and Its Implications

In society, people assume various roles, including employees, caregivers, spouses, and volunteers. Each of us is responsible for different tasks at work, at home, and in our communities. However, when the demands and pressures from work and personal life are incompatible, it leads to work–life conflict (WLC). These incompatibilities can be categorised as time-based, strain-based, or behaviour-based [1]. For instance, time-based conflicts may arise when work and personal schedules overlap. Strain-based conflicts can occur when fatigue from work affects our ability to perform tasks at home. Behaviour-based conflicts might happen when someone uses a tone of voice at home that is more suitable for the workplace. Research indicates that both time- and strain-based conflicts are particularly associated with negative outcomes in both work and home settings [25].

Conservation of resources theory (COR) [17,18] explains work–life conflict as a struggle to manage limited resources (time, energy, and other resources). More precisely, people strive to retain, protect, and build resources, while the potential or actual loss of these valued resources is highly unwanted. However, when work demands increase—whether through long hours, high pressure, or excessive responsibilities—they deplete the resources people would usually use for their personal life, family, or leisure. As resources are depleted, individuals experience stress and dissatisfaction as they cannot fulfil nonwork obligations (e.g., [26]). Not surprisingly, WLC leads to various detrimental outcomes, such as stress, dissatisfaction, lower performance, and withdrawal behaviours across work and life domains [27].

2.2. The Relationship Between Segmentation Supplies and Work–Life Conflict

Different roles and tasks have distinct contexts and objectives, so people use boundaries to clarify the environment and ease transitions between roles [28,29]. According to border theory [19], individuals establish and maintain physical, behavioural, and psychological borders between work and life domains to achieve work–life balance. For example, using different laptops for work and personal use enables physical boundaries between the two domains. Similarly, boundary theory [20] posits that people engage in boundary management work to establish and control the permeability and flexibility of role boundaries, thereby achieving desired levels of segmentation or integration between roles. For example, a person can decide if they want to answer a call from a relative while at work. These two theories offer complementary perspectives on how individuals navigate transitions between their various social roles and inherently posit that boundary management is essential for achieving balance between work and nonwork domains [30].

Moreover, as switching from one domain to another requires cognitive, physical, and/or emotional efforts (e.g., [30]), the segmentation strategies employed by individuals can mitigate the adverse effects of work–life interference [31,32,33]. The latest findings indicate that when people proactively segment their work and nonwork domains, it enables them to detach from work, which in turn helps diminish work–nonwork conflict [34]. On the contrary, boundary violations are associated with lower satisfaction in both work and nonwork domains [35].

Following theoretical reasoning and existing research that posit segmentation as beneficial for managing work and private life domains, we suggest that organisations might play an active supporting role in helping employees separate or integrate work and nonwork domains [32]. As defined by Kreiner [36], segmentation supplies from organisations are present when workplaces allow employees to forget and mentally, emotionally, and physically leave work after working hours. In other words, segmentation supplies could be seen as a resource from the organisation’s side, which can be used when needed and if wanted. For example, organisations can establish a norm that responding to work emails outside of working hours is not necessary. Segmentation supplies can help minimise unwanted transitions between different domains (e.g., [37]), and this, in turn, could lower work–life conflict. Unfortunately, the empirical examination of the segmentation supplies and their links to WLC is very scarce [2]. Thus, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H1.

Higher segmentation supplies T1 predict lower work–life conflict T2.

2.3. Work–Life Conflict, Burnout, and Work–Nonwork Balance

While the interest in work–life conflict stems from its adverse effects on employees and organisations (for an extensive review, see [27]), this study focuses on two key aspects: burnout and work–life balance.

Work–life conflict is one of the most prominent predictors of burnout. While boundary theories [20] posit that the incompatibility of life roles can create strain, COR explains that strain, when not accompanied by adequate resources and recovery time, is likely to result in exhaustion [17,18] and, subsequently, in burnout. Researchers have found longitudinal relationships using related constructs, e.g., work–family conflict being positively associated with elevated burnout symptoms over a multi-wave longitudinal 6-year study [38], work–life interference after one year increasing the odds of burnout [39], as well as meta-analytic results, confirming the relationship between work–nonwork conflict and burnout subscales of emotional exhaustion and cynicism [40], and many cross-sectional studies with work–family conflict significantly predict burnout (e.g., [41,42]). Consistent with prior research, we raise the following hypothesis:

H2a.

Higher work–life conflict T1 predicts higher burnout T2.

Much less studied is the relationship between WLC and work–life balance. Although WLC was conceptualised as an antecedent of work–life balance more than a decade ago [23], the empirical evidence on their relationships remains scarce, mainly because of substantial disagreement about how to define balance. Although balance has been described in various ways, it is generally considered a holistic perception of how work and family intersect [24]. In this study, we adopt the definition of balance provided by Casper et al. [24], who emphasised its conceptual difference from work–life conflict, enrichment, effectiveness, and satisfaction. They defined balance as “employees’ evaluation of the favourability of their combination of work and nonwork roles arising from the degree to which their affective experiences and their perceived involvement and effectiveness in work and nonwork roles are commensurate with the value they attach to these roles.” [24] (p. 197). This definition has prompted Wayne et al. [43] to develop and validate a multidimensional scale to assess affective, involvement, and effectiveness balance. Affective balance refers to the experience of enjoyable emotions. In comparison, involvement balance reflects the perception of appropriate engagement in multiple roles, proportional to the value ascribed to those roles, with effectiveness denoting the perception of being effective in one’s roles. These three distinct dimensions of work–life balance uniquely predict different outcomes relevant to employees and employers: employee engagement, organisational commitment, turnover intentions, and emotional exhaustion [43].

While meta-analytic evidence suggests that WLC is linked to work–life balance [44], their findings are based solely on a limited number of cross-sectional studies. Moreover, existing studies (e.g., [45,46]) typically do not distinguish between the balance dimensions but instead measure balance satisfaction. Therefore, research has yet to respond to calls for greater attention to the organisational antecedents and mechanisms of multidimensional balance [43]. In their initial research, Wayne et al. [43] found that different balance dimensions are linked to various constructs in a distinct manner, corresponding to the areas they are covering, e.g., job and family satisfaction tend to show stronger correlations with affective balance. In comparison, performance tends to show stronger correlations with effectiveness balance. The few existing studies in this area suggest that different balance dimensions might have distinct relationships with WLC: conflict initiated the relational cycle with effectiveness balance, but not satisfaction balance (comparable to affective balance) [47]. However, other relevant research, where work–family balance satisfaction was measured, indicated different results: work interpersonal conflict predicted work–family balance satisfaction (via negative work reflection) [48].

In summary, the existing research does not provide answers regarding the longitudinal relations between WLC and work–nonwork balance dimensions. We address this research gap and, based on theoretical links, raise the following hypothesis:

H2b1.

Higher work–life conflict T1 predicts lower effectiveness balance T2;

H2b2.

Higher work–life conflict T1 predicts lower involvement balance T2;

H2b3.

Higher work–life conflict T1 predicts lower affective balance T2.

2.4. Segmentation Supplies, Work–Life Conflict, Burnout, and Work–Life Balance When Teleworking

While this study posits that segmentation supplies provided by organisations serve as a valuable resource that helps reduce WLC, which in turn lowers burnout and enhances work–life balance, we also expect these effects might be different among teleworkers and office workers. We base our assumption on the following rationale.

First, as suggested by some studies, for teleworkers who split their working time between the office and non-office settings, the picture of WLC, its antecedents, and outcomes becomes less straightforward [49]. More precisely, while teleworkers face increased autonomy and flexibility, which can reduce WLC [50], relieve stress, and improve well-being [51], they also experience more boundary blurring through unwanted or unintentional role transitions [13], leading to more job strain and exhaustion [52]. In other words, the results of very scarce research on the relationship between WLC, burnout, and work–life balance are equivocal.

Second, the role of segmentation supplies in managing work–life conflict for teleworkers might be dual. On the one hand, due to the pervasive use of information and communication technologies, teleworkers frequently remain connected and monitor work-related communications during their off-hours [53]. Therefore, setting temporal, physical, communicative, and technological boundaries might enable teleworkers to recover from job demands and devote more time and energy to personal and family demands [54]. In this case, teleworkers might benefit from organisational efforts to allow them to distance themselves from work-related matters. On the other hand, as teleworkers possess autonomy in terms of time and space, they may respond to family demands during working hours and vice versa [12]. For example, a diary study by Delanoeije et al. [55] showed that teleworkers more frequently interrupted work activities during work hours to handle home demands, which in turn reduced work–life conflict. In this situation, the segmentation resources provided by the organisation might not benefit teleworkers in reducing WLC.

Summing up, the existing scarce research provides equivocal results on the relationship between segmentation supplies, work–life conflict, burnout, and work–life balance, leading to the research question of our study:

RQ: Are segmentation supplies related over time to lower burnout and higher work–life balance through lower work–life conflict for office-based workers and teleworkers?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

A two-wave survey was conducted in the spring and autumn of 2024, using convenience sampling, with 359 employees participating. Respondents originated from various industries, with the largest being science and education (19.2%), followed by medicine and social care (12.3%), wholesale and retail trade (10%), and finance and insurance (9.2%). The sector distribution suggests that the sample is largely drawn from white-collar environments, which often involve high cognitive demands, professional responsibility, and a service-oriented approach. Before conducting the survey, informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The time lag between the first (T1) and the second (T2) measurements was approximately 6 months; the participation rate at T2 was 42.3% (N = 152).

The mean age of the sample was 39.3 years (SD = 12.5), and, on average, people had worked in their current organisations for 8.5 years (SD = 9.7). A total of 83% worked full-time, and 91.9% had permanent contracts. A total of 23.7% were supervisors, and 57.9% indicated that they worked only in the office (vs. 42.1% who teleworked at least part of their working time).

More than half (51.8%) of the sample were married, around one-fifth (20.3%) were unmarried, and another major group (18.7%) were living with a partner. Remaining participants were divorced (7%) or widowed (2.2%). A total of 41.2% of participants were living with minor children, and the majority (76.6%) were women. The majority of the sample (67.1%) had a university education, 15.6% had a higher non-university education, 11.7% had secondary education, and the remaining 5.6% had vocational training.

3.2. Measures

The questionnaires were initially translated from English to Lithuanian, utilising a backtranslation process to guarantee that all items retained their original meaning [56]. Respondents were asked to evaluate, in general, their perceptions of various aspects of their work and personal life.

Segmentation supplies were measured at T1 and T2, and segmentation preferences, serving as a control variable, were measured at T1. The constructs were measured using four items each, adopted from Kreiner [36]. Items were rated on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). A sample segmentation supplies item is “Where I work, people can keep work matters at work”, and a sample segmentation preferences item is “I don’t like work issues creeping into my home life”.

Work–life conflict was measured at T1 and T2 using four items from Geurts et al. [25] on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always/almost always). A sample item is “Your work schedule makes it difficult to fulfil your responsibilities at home.”

Work–nonwork balance was measured at T1 and T2 using a scale by Wayne et al. [43]. The scale has three dimensions, each measured with five items: (1) involvement balance (a sample item: “I am able to devote enough attention to important work and nonwork activities”), (2) effectiveness balance (e.g., “I perform well in the life roles that I really value”), and (3) affective balance (e.g., “I am happy in the work and nonwork roles that are most important to me”). Items were measured on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree).

Burnout was measured at T1 and T2 using the 12-item short version of the Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT) [57]. It measures the core symptoms of burnout: exhaustion, mental distance, cognitive impairment, and emotional impairment (a sample item: “At work, I feel mentally exhausted”). All items were rated on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1—never to 5—always.

The telework vs. office group division was based on respondents’ answers about which working mode they use: fully on-site or telework (at least partially not on-site).

The reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s αs) for all used measures are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics, Spearman’s correlation coefficients, and reliability statistics of the study variables.

3.3. Data Analyses

Longitudinal semi-mediated multigroup models were tested using Mplus v8.4. Correlational analyses and descriptive statistics were performed using the SPSS 28 software. Analyses were conducted using the maximum likelihood (MLR) estimator, which accounts for missing data via full-information maximum likelihood (FIML). We tested the drop-out patterns of all relevant variables in the models. The two variables that differed in the groups were working mode and segmentation supplies: slightly more people in the drop-out group worked in a telework setting (ΔM = −0.11, p = 0.047), and they had slightly more segmentation supplies (ΔM = −0.22, p = 0.032). To ensure that drop-out cases did not alter results, primary analyses were repeated on cases with no missing data, and the patterns were the same as reported using FIML.

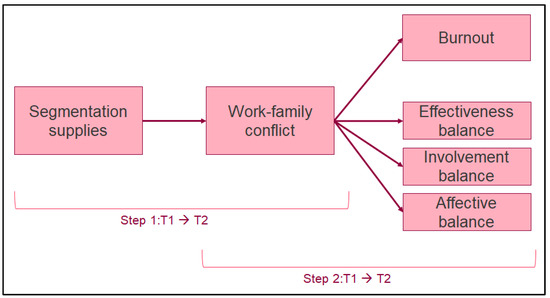

Since full mediation testing is not possible with two waves of data, a two-step procedure was applied for hypothesis testing, as shown in Figure 1. We followed the guidelines of Cole and Maxwell [58] and a procedure by Taris et al. [59]. In the first step, we tested the longitudinal relationship between the hypothesised predictor (segmentation supplies) and the mediator (work–life conflict). In the second step, we explored the longitudinal relationships between the mediator and the outcomes (burnout and work–life balance dimensions). If the predictor is related to the mediator over time and the mediator predicts the outcomes, this pattern suggests a likely mediating role of the intermediary construct.

Figure 1.

Conceptual research model, tested for office-based employees and teleworkers.

In the first step, four models were tested to evaluate their fit to the data: a stability model, a forward model (predicting the expected direction), a reverse model, and a reciprocal model. The stability model had autoregressive paths only, with no cross-lagged effects. The forward model added a cross-lagged path from segmentation supplies T1 to work–life conflict T2. The reverse model specified the opposite direction, with work–life conflict T1 predicting segmentation supplies T2. The reciprocal model incorporated both the autoregressive and the bidirectional paths between the two constructs.

In the second step, four sets of analyses were conducted, each focusing on a different outcome variable. Each set of the analyses followed the same model structure as in step 1, testing the four competing models. The stability models included only autoregressive paths; the forward models had work–life conflict at T1 as a predictor of one of the outcomes at T2; the reverse models had one of the outcome variables at T1 predicting work–life conflict at T2; and the reciprocal models included both autoregressive and cross-lagged paths in both directions.

To analyse whether the relationships were the same or differed for office and teleworkers, the Mplus multi-group function was applied. Model comparisons were conducted using the Satorra–Bentler scaled Δχ2 test (T-statistic, an alternative to Δχ2 when MLR is used), which allows for assessing whether increasing model complexity results in substantive and statistically meaningful gains in fit. Additionally, the standard comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were used. A good fit is indicated by conventional CFI and TLI values of at least 0.90 [60], and an RMSEA value of 0.08 or less is expected [61].

Controlling for demographics (age, gender, and having or not having minor children) and segmentation preferences, segmentation supplies were modelled to predict different outcomes (different dimensions of work–life balance and burnout) through work–life conflict. Models were tested in telework and office-based employee groups.

4. Results

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1, and the descriptive statistics for telework and office-based groups are provided separately in Appendix A, Table A1. All correlations were in the expected direction. Segmentation supplies were negatively correlated with work–nonwork conflict and burnout. Segmentation supplies and work–life balance dimensions were either positively correlated or had no relationship.

Table 2 presents the fit indices for all the tested models. In step 1, the reciprocal model showed the best fit based on all fit criteria, and it was significantly better compared to the second-best-fitting model.

Table 2.

Fit indices of the tested models.

In step 2, four sets of analyses were conducted to examine the relationships between work–life conflict and the four outcomes: burnout, effectiveness balance, involvement balance, and affective balance. As shown in Table 2, the forward model provided the best fit to the data across all sets.

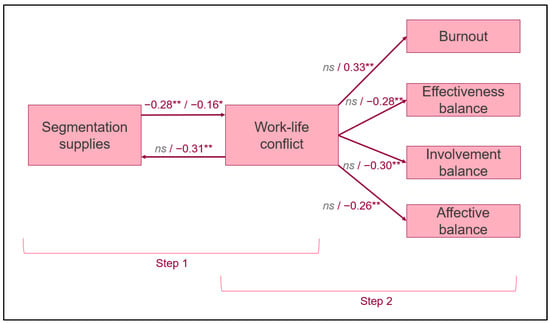

Group analyses in step 1 revealed that segmentation supplies predicted lower work–life conflict after six months for both telework and office settings. In contrast, work–life conflict predicted lower segmentation supplies after six months for the telework setting only. In step 2, all tested models showed that cross-lagged effects were present for teleworkers but not for office workers. As shown in Figure 2, for teleworkers, work–life conflict predicted the modelled outcomes after six months in the theoretically expected direction: higher burnout and lower effectiveness, involvement, and affective balance. The autoregressive paths were significant for all variables in both groups.

Figure 2.

Analyses results for telework and office workers (final models). Standardised (Beta) regression coefficients are provided before and after the slash sign: for office workers/teleworkers. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01. ns—non-significant.

The findings supported hypotheses H1 (in both groups, office and telework) and H2 (in the telework group only). In the telework group, higher work–life conflict was associated with lower work–life balance in all three dimensions and higher burnout. For the office workers group, no relationships were confirmed between work–life conflict and all the tested outcomes (neither work–life balance nor burnout).

5. Discussion

Using a cross-lagged design, this study aimed to test the role of organisational segmentation supplies in reducing burnout and enhancing work–life balance through diminishing WLC among teleworkers and office workers. The results of our study show that organisational support for employees in maintaining boundaries between work and personal life indeed acts as resources that prevent WLC, even when accounting for individual segmentation preferences. This suggests that organisational segmentation supplies act as a resource independently of personal preferences. This finding aligns with boundary theory [20] and adds robustness to some previous studies (e.g., [32,37,62]) that were primarily cross-sectional. Moreover, the longitudinal link between segmentation supplies and WLC was weaker for teleworkers than for office-based employees. There might be several related, yet different, explanations for this result. First, telework usually involves more permeable physical boundaries [63]. Even when organisations provide segmentation-supporting practices, it is difficult to avoid reading work emails when the surroundings of work and nonwork are the same, especially if the same communication devices are used for both personal and work matters (e.g., [64]). Second, teleworking requires more self-discipline to implement segmentation well. With fewer social cues and weaker external pressure, such as work monitoring, it may be challenging for employees to effectively apply the segmentation supplies provided by the company [65].

The results of our study also found that WLC predicts lower segmentation supplies over time among teleworkers. In other words, experiencing WLC led employees to lower perceptions of organisational segmentation-supportive policies. Although contrary to expectations, this result aligns with the self-undermining processes identified in previous research, indicating that impaired states of well-being predict lower resources and higher demands over time. This suggests that strained employees create more demands for themselves (see [66]). Furthermore, as teleworking is expected to improve the management of work and home demands [11], failing to achieve this might cause employees to attribute it to a lack of organisational resources. For example, using the perspective of source attribution, which posits that when people experience work–family conflict, they psychologically attribute blame to the domain that is the source of the conflict and thus develop a negative attitude toward this domain, Zhao et al. [67] found that work conflict predicts lower job satisfaction. Similarly, a study by Darouei and colleagues [68] found that it is not work–home interference itself that has implications for employees’ well-being but rather how the employee perceives that interference. Our findings also provide empirical evidence that not only the actual organisational environment and its resources but also their cognitive appraisals should be evaluated in studies exploring work–life interaction.

The results of our study also showed that for teleworkers, segmentation supplies predict lower burnout and higher work–life balance through lower WLC over time. Importantly, these beneficial effects of segmentation supplies through WLC were evident among teleworkers but not office workers. In other words, the results of our study indicate that it is teleworkers who benefit from organisational resources, enabling them to separate work and private life. This implies that when boundaries are blurred, as in telework, segmentation resources become particularly valuable, whereas office arrangements provide physical separation that diminishes their importance. Moreover, these results also suggest that telework arrangements uniquely amplify the adverse effects of work–life conflict on employee burnout and work–life balance. This finding aligns with Wang et al.’s [65] research, which identified work–home interference as the most frequently mentioned challenge during the COVID-19 pandemic, having deleterious effects on employee well-being. This illustrates that employees identified permeable or blurred boundaries as their primary strain in telework arrangements. An additional argument also comes from the boundary management field, suggesting that telework settings might offer fewer transition rituals, which benefit office workers. In contrast to office-based employees, teleworkers usually do not have a clear-cut marking where the working ends, e.g., closing office doors or arriving home [69]. Another line of thought to explain the relationships in a telework setting stems from the conservation of resources theory [17]. Grounded in it, work-related stressors can deplete personal resources when external support is weak. Hence, work–life conflict might be more deleterious when organisational support is weak, and telework settings might suggest lower levels of support from colleagues and the organisation. This finding is consistent with previous research, which has shown that the impact of working at home on health outcomes is strongly influenced by the degree of organisational support [70].

By demonstrating the longitudinal relationship between WLC and work–life balance for teleworkers, we broaden the understanding of WLC outcomes and answer the call by Wayne et al. [47] to study the antecedents of different types of work–life balance, using a longitudinal design [2]. Importantly, the results of our study show that when WLC is lower, teleworkers report higher involvement balance and better effectiveness balance in highly valued roles, as well as more positive emotions in these roles over time. From a COR theory perspective, this reflects not only the prevention of resource loss but also suggests the initiation of a positive resource spiral, where segmentation supplies predict lower WLC, which in turn predicts better work–nonwork balance dimensions. Our findings support the interpretation that segmentation supplies not only prevent resource depletion (and, hence, burnout) but also create conditions for resource gain, as organisational segmentation supplies can increase the likelihood that employees actually obtain recovery experiences at home. Finally, although we did not find the longitudinal relationship between WLC, burnout, and work–life balance among office workers, the cross-sectional relationships were present and in the expected direction. This suggests that although the adverse effects of WLC may not persist over time for on-site workers, they may be observed concurrently, thereby calling for efforts to manage WLC.

In summary, our study posits that organisational support for segmentation serves as a resource that reduces work–life conflict for both teleworkers and onsite workers, thereby demonstrating the role of organisational efforts in employees’ efforts to manage work and home demands. This comprehension contributes to the realisation of Sustainable Development Goal 8 established by the United Nations [16], which seeks to foster sustainable economic growth and ensure decent work opportunities for all individuals. Moreover, the results of our study demonstrate that organisational resources for segmentation are the most beneficial for teleworkers in helping them to reduce WLC and burnout and increase work–life balance. Understanding the aspects of work and employee well-being in the modern telework setting is key to sustainable workforce and workplace development.

5.1. Practical Implications

The findings of our study provide valuable insights that can be applied in practical settings. First and foremost, as our research highlights the importance of segmentation supplies in managing work–life conflict for both teleworkers and on-site workers, organisations should consider directing their efforts to support employees’ ability to maintain clear boundaries between work and personal life. Notably, an organisational culture that openly values work–life boundaries, discourages overwork, and supports utilisation of offered flexibility reinforces individual efforts to segment work and personal domains [71]. The importance of maintaining work–life boundaries is reflected in the discourse on the “right to disconnect” among policymakers and leaders [72].

Establishing clear boundaries between professional and personal life can be accomplished by implementing specific policies related to organisational expectations regarding employee availability outside of working hours (for instance, employees should not be required to—or, ideally, should refrain from—responding to work emails during weekends and vacations or after a predetermined time on weekdays). Importantly, formal policies within organisations should be complemented by informal practices that embody these expectations, particularly through the behaviours demonstrated by supervisors. For instance, supervisors play a crucial role in modelling appropriate behaviours; by adhering to established temporal and physical boundaries—such as refraining from sending emails outside designated hours—they can encourage employees to emulate these practices [73].

Moreover, organisations could train supervisors to be attuned to their employees’ boundary management preferences and empower them to provide family-supportive supervision, which has been shown to substantially reduce boundary blurring and burnout [74]. The role of supervisors is pivotal in fostering an environment where employees feel empowered to communicate their needs and receive tailored support that aligns with their individual circumstances [75]. Similarly, direct interventions, such as boundary management training programs, help employees learn and practice strategies to manage and defend their boundaries [10] actively. Organisations could guide employees on how to establish “microborders,” such as scheduling regular nonwork periods, which can empower them to maintain boundaries even under flexible or remote work arrangements [76].

Notably, when employing policies and cultivating a culture focused on boundary management, organisations should be aware of employee preferences. Some research shows that a misfit between individual boundary preferences and the organisational environment might increase the risk of dissatisfaction and conflict [77]. Moreover, as boundary challenges differ across demographic groups, including generational and parental status differences [75], organisational actions should be attuned to the differing actual needs of employees.

5.2. Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations of the study should be considered when evaluating our findings.

First, we have investigated segmentation supplies as organisational resources, which appeared to be important in managing WLC for both teleworkers and office workers. However, there might also be other resources relevant for managing work and life demands, such as family-supportive supervisor behaviours that have not received much attention in the context of telework [78].

Second, when examining the role of segmentation supplies on WLC, it might be important to consider the interplay between individual preferences for segmentation and the segmentation resources provided by organisations. While we have accounted for segmentation preferences in our analysis, findings from studies such as Basile and Beauregard ([21,79]) indicate that an important factor may not lie in the individual preferences or the organisational resources themselves but rather in how well they align with one another, also taking into account the fluctuating demand of family needs. Therefore, future studies could examine the fit between varying segmentation preferences and supplies and their role for WLC, burnout, and work–life balance.

It should be noted that the study used a convenience sample, which limits the possibility of generalising these findings. Naturally, we invite other scholars to investigate the same questions in different work settings and cultures and with various samples, such as examining the possible effects of age, gender, having minor children, and different professions, among others. For example, segmentation supplies could be more influential in autonomy-rich sectors where employees have greater control over work scheduling or different industries that may have different availability norms, as well as possible differential dynamics for individuals with high versus low education, which contributes to jobs with, respectively, higher and lower autonomy. Additionally, in our study, participants were asked to evaluate their general perception of work and personal life. There is a possibility that other reference points, such as the previous day or week, could introduce additional insights—this also offers a path for future analyses.

Finally, scholars should consider a broader range of outcome variables to capture a more comprehensive and precise picture of the consequences of segmentation supplies and WLC, especially considering their importance among teleworkers. Going beyond employee well-being indicators and focusing on performance or work well-being evaluations [4] or taking into account more family-specific outcomes, such as partners’ well-being [5], may reveal additional benefits or trade-offs associated with organisational segmentation practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, R.J., J.L.-Z. and I.U.; methodology, R.J. and I.U.; formal analysis, R.J. and A.Ž.; investigation, R.J., J.L.-Z. and A.Ž.; data curation, J.L.-Z.; writing—original draft preparation, R.J. and J.L.-Z.; writing—review and editing, R.J., J.L.-Z., A.Ž. and I.U.; visualisation, R.J.; supervision, J.L.-Z.; project administration, J.L.-Z.; funding acquisition, J.L.-Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant (No. S-MIP-23-11) from the Research Council of Lithuania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study by the Institutional Committee due to Legal Regulations (https://www.e-tar.lt/rs/actualedition/2c05c6603d4011ec992fe4cdfceb5666/yFgWpOSkij/format/OO3_ODT/ accessed on 29 October 2025), as the approval of an institutional review board is not required for the type of research conducted in this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WLC | Work–life conflict |

| COR | Conservation of resources theory |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics of the main variables in the study for telework and office-based groups.

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics of the main variables in the study for telework and office-based groups.

| M for Office Workers | SD for Office Workers | M for Teleworkers | SD for Teleworkers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Segmentation preference T1 | 3.94 | 0.75 | 3.95 | 0.73 |

| 2. Segmentation supplies T1 | 3.30 | 0.99 | 3.38 | 0.90 |

| 3. Segmentation supplies T2 | 3.21 | 0.87 | 3.45 | 0.89 |

| 4. Work–life conflict T1 | 2.39 | 0.98 | 2.26 | 0.86 |

| 5. Work–life conflict T2 | 2.32 | 0.87 | 2.08 | 0.82 |

| 6. Burnout T1 | 2.36 | 0.56 | 2.27 | 0.53 |

| 7. Burnout T2 | 2.37 | 0.53 | 2.26 | 0.52 |

| 8. Involvement balance T1 | 3.71 | 0.65 | 3.76 | 0.63 |

| 9. Involvement balance T2 | 3.58 | 0.66 | 3.76 | 0.65 |

| 10. Effectiveness balance T1 | 3.76 | 0.66 | 3.75 | 0.66 |

| 11. Effectiveness balance T2 | 3.65 | 0.69 | 3.69 | 0.61 |

| 12. Affective balance T1 | 3.72 | 0.70 | 3.79 | 0.74 |

| 13. Affective balance T2 | 3.64 | 0.76 | 3.77 | 0.59 |

Notes. N (office workers) for measurements at T1 = 208 and T2 = 78–80. N (teleworkers) for measurements at T1 = 171 and T2 = 81–84.

References

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of Conflict between Work and Family Roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; French, K.A. Work-family Research: A Review and next Steps. Pers. Psychol. 2023, 76, 437–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, B.; Chen, C. Examining the Relationship between Work-Life Conflict and Burnout. J. Natl. Inst. Career Educ. Couns. 2024, 47, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Joshanloo, M.; Yu, G.B. How Does Work-Life Conflict Influence Wellbeing Outcomes? A Test of a Mediating Mechanism Using Data from 33 European Countries. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2025, 20, 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lott, Y.; Wöhrmann, A.M. Spillover and Crossover Effects of Working Time Demands on Work–Life Balance Satisfaction among Dual-Earner Couples: The Mediating Role of Work–Life Conflict. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 12957–12973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. EU Strategic Framework on Health and Safety at Work 2021–2027; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0323 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Wang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, W. Relationship between Daily Work Connectivity Behavior after Hours and Work–Leisure Conflict: Role of Psychological Detachment and Segmentation Preference. PsyCh J. 2023, 12, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oseghale, O.R.; Pepple, D.; Brookes, M.; Lee, A.; Alaka, H.; Nyantakyiwaa, A.; Mokhtar, A. COVID-19, Working from Home and Work–Life Boundaries: The Role of Personality in Work–Life Boundary Management. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 35, 3556–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althammer, S.E.; Wöhrmann, A.M.; Michel, A. Meeting the Challenges of Flexible Work Designs: Effects of an Intervention Based on Self-Regulation on Detachment, Well-Being, and Work–Family Conflict. J. Happiness Stud. 2025, 26, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinke, K.; Ohly, S. Examining the Training Design and Training Transfer of a Boundary Management Training: A Randomized Controlled Intervention Study. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2024, 97, 864–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.J.; Payne, S.C.; Alexander, A.L.; Gaskins, V.A.; Henning, J.B. A Taxonomy of Employee Motives for Telework. Occup. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 149–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laß, I.; Wooden, M. Working from Home and Work–Family Conflict. Work Employ. Soc. 2023, 37, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abendroth, A.-K.; Reimann, M. Chapter 15 Telework and Work–Family Conflict across Workplaces: Investigating the Implications of Work–Family-Supportive and High-Demand Workplace Cultures. In Contemporary Perspectives in Family Research; Blair, S.L., Obradović, J., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2018; Volume 13, pp. 323–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Dealing with Digital Security Risk During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Crisis; OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19); OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. Right to Disconnect: Implementation and Impact at Company Level; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023; Available online: https://eurofound.link/ef23002 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Department of Economic And Social Affairs. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2025; United Nations Research Institute for Social Development: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2025/ (accessed on 29 October 2025)ISBN 978-92-1-107159-7.

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources: A New Attempt at Conceptualizing Stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.-P.; Westman, M. Conservation of Resources in the Organizational Context: The Reality of Resources and Their Consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.C. Work/Family Border Theory: A New Theory of Work/Family Balance. Hum. Relat. 2000, 53, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Kreiner, G.E.; Fugate, M. All in a Day’s Work: Boundaries and Micro Role Transitions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, K.; Beauregard, T.A. Oceans Apart: Work-Life Boundaries and the Effects of an Oversupply of Segmentation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 1139–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauner, C.; Wöhrmann, A.M.; Michel, A. Congruence Is Not Everything: A Response Surface Analysis on the Role of Fit between Actual and Preferred Working Time Arrangements for Work-Life Balance. Chronobiol. Int. 2020, 37, 1287–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Allen, T.D. Work–family balance: A review and extension of the literature. In Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology, 2nd ed.; Quick, J.C., Tetrick, L.E., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, W.J.; Vaziri, H.; Wayne, J.H.; DeHauw, S.; Greenhaus, J. The Jingle-Jangle of Work–Nonwork Balance: A Comprehensive and Meta-Analytic Review of Its Meaning and Measurement. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 182–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geurts, S.A.E.; Taris, T.W.; Kompier, M.A.J.; Dikkers, J.S.E.; Van Hooff, M.L.M.; Kinnunen, U.M. Work-Home Interaction from a Work Psychological Perspective: Development and Validation of a New Questionnaire, the SWING. Work Stress 2005, 19, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.J.; Carlson, D.S.; Kacmar, K.M.; Vogel, R.M. The Cost of Being Ignored: Emotional Exhaustion in the Work and Family Domains. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, J.S.; Clark, M.A.; Beiler, A.A. Work–Life Conflict and Its Effects. In Handbook of Work–Life Integration Among Professionals; Major, D.A., Burke, R.J., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-78100-929-1. [Google Scholar]

- Urbanavičiūtė, I.; Lazauskaitė-Zabielskė, J.; Žiedelis, A. Re-drawing the Line: Work-home Boundary Management Profiles and Their Dynamics during the Pandemic. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 72, 1506–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nippert-Eng, C. Calendars and Keys: The Classification of “Home” and “Work”. Sociol. Forum 1996, 11, 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Cho, E.; Meier, L.L. Work–Family Boundary Dynamics. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Merlo, K.; Lawrence, R.C.; Slutsky, J.; Gray, C.E. Boundary Management and Work-Nonwork Balance While Working from Home. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 70, 60–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucreault, A.; Ollier-Malaterre, A.; Ménard, J. Organizational Culture and Work–Life Integration: A Barrier to Employees’ Respite? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 2378–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Ruderman, M.N.; Braddy, P.W.; Hannum, K.M. Work–Nonwork Boundary Management Profiles: A Person-Centered Approach. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 81, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelides, G.; Niven, K.; Wood, S.; Inceoglu, I. A Dual-process Model of the Effects of Boundary Segmentation on Work–Nonwork Conflict. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2024, 97, 1502–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerman, K.; Korunka, C.; Tement, S. Work and Home Boundary Violations during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Segmentation Preferences and Unfinished Tasks. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 71, 784–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiner, G.E. Consequences of Work-home Segmentation or Integration: A Person-environment Fit Perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, W. Effects of Segmentation Supply and Segmentation Preference on Work Connectivity Behaviour after Hours: A Person–Environment Fit Perspective. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 28146–28159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocalevent, R.; Pinnschmidt, H.; Selch, S.; Nehls, S.; Meyer, J.; Boczor, S.; Scherer, M.; Van Den Bussche, H. Burnout Is Associated with Work-Family Conflict and Gratification Crisis among German Resident Physicians. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gynning, B.E.; Christiansen, F.; Lidwall, U.; Brulin, E. Impact of Work–Life Interference on Burnout and Job Discontent: A One-Year Follow-up Study of Physicians in Sweden. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2024, 50, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichl, C.; Leiter, M.P.; Spinath, F.M. Work–Nonwork Conflict and Burnout: A Meta-Analysis. Hum. Relat. 2014, 67, 979–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Zhao, J.; Wu, H.; Ji, X. The Impact of Work-Family Conflict on Job Burnout among Community Social Workers in China. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0301614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zábrodská, K.; Mudrák, J.; Šolcová, I.; Květon, P.; Blatný, M.; Machovcová, K. Burnout among University Faculty: The Central Role of Work—Family Conflict. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 38, 800–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, J.H.; Vaziri, H.; Casper, W.J. Work-Nonwork Balance: Development and Validation of a Global and Multidimensional Measure. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 127, 103565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaziri, H.; Wayne, J.H.; Casper, W.J.; Lapierre, L.M.; Greenhaus, J.H.; Amirkamali, F.; Li, Y. A Meta-analytic Investigation of the Personal and Work-related Antecedents of Work–Family Balance. J. Organ. Behav. 2022, 43, 662–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattusamy, M.; Jacob, J. A Test of Greenhaus and Allen (2011) Model on Work-Family Balance. Curr. Psychol. 2017, 36, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, J.H.; Matthews, R.; Crawford, W.; Casper, W.J. Predictors and Processes of Satisfaction with Work–Family Balance: Examining the Role of Personal, Work, and Family Resources and Conflict and Enrichment. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 59, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, J.H.; Michel, J.S.; Matthews, R.A. Balancing Work and Family: A Theoretical Explanation and Longitudinal Examination of Its Relation to Spillover and Role Functioning. J. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 107, 1094–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.; Shaffer, M.A.; Singh, R.; Zhang, Y. Spoiling for a Fight: A Relational Model of Daily Work-family Balance Satisfaction. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2022, 95, 60–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Huang, Y. Work from Home and Employee Well-Being: A Double-Edged Sword. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, E. The Origins of Emerging Adults’ Work–Family Balance Self-Efficacy: A Dyadic Study. J. Career Dev. 2024, 51, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanis, E. The Relationship between Flexible Employment Arrangements and Workplace Performance in Great Britain. Int. J. Manpow. 2018, 39, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giauque, D.; Renard, K.; Cornu, F.; Emery, Y. Engagement, Exhaustion, and Perceived Performance of Public Employees Before and During the COVID-19 Crisis. Public Pers. Manag. 2022, 51, 263–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booker, L.; Mowbray, P.K.; Townsend, K.; Chan, X.W. Connectivity Agency in Telework: A Qualitative Analysis of Facilitators and Barriers. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2025, 47, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haun, V.C.; Remmel, C.; Haun, S. Boundary Management and Recovery When Working from Home: The Moderating Roles of Segmentation Preference and Availability Demands. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Z. Für Pers. 2022, 36, 270–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanoeije, J.; Verbruggen, M.; Germeys, L. Boundary Role Transitions: A Day-to-Day Approach to Explain the Effects of Home-Based Telework on Work-to-Home Conflict and Home-to-Work Conflict. Hum. Relat. 2019, 72, 1843–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and Content Analysis of Oral and Written Materials. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; Volume 2, Methodology; pp. 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; De Witte, H.; Desart, S. Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT)—Test Manual; Internal Report; KU Leuven: Leuven, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, D.A.; Maxwell, S.E. Testing Mediational Models With Longitudinal Data: Questions and Tips in the Use of Structural Equation Modeling. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003, 112, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taris, T.W.; Van Beek, I.; Schaufeli, W.B. The Motivational Make-Up of Workaholism and Work Engagement: A Longitudinal Study on Need Satisfaction, Motivation, and Heavy Work Investment. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Evaluating model fit. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 76–99. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-0-203-80764-4. [Google Scholar]

- Žiedelis, A.; Lazauskaitė-Zabielskė, J.; Urbanavičiūtė, I. Reconciling Home and Work During Lockdown: The Role of Organisational Segmentation Supplies for Psychological Detachment and Work-Home Conflict. Psichologija 2021, 64, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazauskaite-Zabielske, J.; Ziedelis, A.; Urbanaviciute, I. When Working from Home Might Come at a Cost: The Relationship between Family Boundary Permeability, Overwork Climate and Exhaustion. Balt. J. Manag. 2022, 17, 705–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Peters, P.; Van Wingerden, P. Work-Related Smartphone Use, Work–Family Conflict and Family Role Performance: The Role of Segmentation Preference. Hum. Relat. 2016, 69, 1045–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Qian, J.; Parker, S.K. Achieving Effective Remote Working During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Work Design Perspective. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 70, 16–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K.; Zhang, M.; Kraimer, M.L.; Yang, B. Source Attribution Matters: Mediation and Moderation Effects in the Relationship between Work-to-family Conflict and Job Satisfaction. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darouei, M.; Delanoeije, J.; Verbruggen, M. When Daily Home-to-Work Transitions Are Not All Bad: A Multi-Study Design on the Role of Appraisals. Work Stress 2024, 38, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiley, A.; Shafaei, A.; Nejati, M.; Onnis, L.; Bentley, T. The Autonomy Paradox, Working from Home and Psychosocial Hazards. J. Ind. Relat. 2025, 67, 356–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakman, J.; Kinsman, N.; Stuckey, R.; Graham, M.; Weale, V. A Rapid Review of Mental and Physical Health Effects of Working at Home: How Do We Optimise Health? BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, K.; Sutter, C.; Sülzenbrück, S. The Concept of “Work-Life-Blending”: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1150707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Bergen, C.; Bressler, M. Work, non-work boundaries and the right to disconnect. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. 2019, 21, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyghebaert-Zouaghi, T.; Berjot, S.; Gillet, N. Benefits of Psychological Detachment from Work in a Digital Era: How Do Job Stressors and Personal Strategies Interplay with Individual Vulnerabilities? Scand. J. Psychol. 2022, 63, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Porter, C.M.; Rosokha, L.M.; Wilson, K.S.; Rupp, D.E.; Law-Penrose, J. Advancing Work–Life Supportive Contexts for the “Haves” and “Have Nots”: Integrating Supervisor Training with Work–Life Flexibility to Impact Exhaustion or Engagement. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 63, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, H.; Pensar, H.; Rousi, R. I Wouldn’t Be Working This Way If I Had a Family—Differences in Remote Workers’ Needs for Supervisor’s Family-Supportiveness Depending on the Parental Status. J. Vocat. Behav. 2023, 147, 103939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adisa, T.A.; Antonacopoulou, E.; Beauregard, T.A.; Dickmann, M.; Adekoya, O.D. Exploring the Impact of COVID-19 on Employees’ Boundary Management and Work–Life Balance. Br. J. Manag. 2022, 33, 1694–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gieter, S.; De Cooman, R.; Bogaerts, Y.; Verelst, L. Explaining the Effect of Work–Nonwork Boundary Management Fit on Satisfaction and Performance at Home through Reduced Time- and Strain-based Work–Family Conflict. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 71, 129–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.L.; Murphy, L.D.; Billeaud, M.L.; Strasburg, A.E.; Cobb, H.R. Supported Here and Supported There: Understanding Family-Supportive Supervisor Behaviors in a Telework Context. Community Work Fam. 2024, 27, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, K.A.; Beauregard, T.A. Boundary Management: Getting the Work-Home Balance Right. In Agile Working and Well-Being in the Digital Age; Grant, C., Russell, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 35–46. ISBN 978-3-030-60282-6. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).