Abstract

Mass concrete is prone to temperature cracks at an early age due to concentrated hydration heat, significant temperature gradients, and complex constraints, which affect structural durability and service safety. This paper reviews the relevant measures for preventing and controlling such temperature cracks, analyzing that the cracks are caused by the coupling effects of hydration heat, temperature gradients and stress distribution, material properties, environmental factors, and structural dimensions. It elaborates on two types of prevention and control measures: material optimization (low-heat cement, mineral admixtures, chemical admixtures, phase change materials, etc.) and construction process improvement (reasonable placement, cooling systems, external thermal insulation). Among these, phase change materials (PCMs) have become a research focus due to their active temperature regulation function of “peak shaving and valley filling”. This paper also introduces temperature, stress, and crack width monitoring technologies, as well as monitoring-based feedback control and intelligent systems. It summarizes the progress of numerical simulations in temperature field, stress field, and cracking prediction, with particular emphasis on their role in improving the understanding and prevention of early-age thermal cracking. The review further identifies shortcomings in multi-factor coupling mechanisms and integrated material–construction design, and proposes future research directions—such as low-heat-of-hydration binders, PCM optimization, and intelligent monitoring integration—to support more effective crack-control practices in mass concrete.

1. Introduction

Mass concrete is widely applied in large scale engineering projects such as dams [1], bridge foundations [2,3], nuclear power plants [4], and thick foundation slabs [5]. Owing to the large placement thickness and volume of mass concrete, the hydration heat generated is difficult to transfer and dissipate effectively, which consequently leads to the formation of a significant temperature gradient between the interior and the surface layer of mass concrete [6]. Once the tensile stress induced by such a temperature gradient exceeds the early age tensile strength of concrete, temperature cracks will occur in the constrained regions of the structure, which impairs the overall stability of the structure.

The occurrence of cracks not only affects the overall appearance and service function of concrete structures, but also serves as penetration channels for aggressive substances such as chloride ions and carbon dioxide, accelerating the deterioration of structural performance. At present, over 30% of concrete projects in China require maintenance; meanwhile, the total amount of funds invested in relevant repair and renovation projects in the United States reaches as high as USD 3.3 trillion [7]. Therefore, research on the prevention and control measures for temperature cracks in mass concrete is of great significance for extending the service life of structures and ensuring engineering safety.

To reduce temperature cracks in mass concrete, existing studies have adopted prevention and control measures such as precooled concrete [8], layered placement technology [9], and cooling pipe arrangement [10], and have achieved certain results. However, in the application process of the aforementioned methods, problems such as difficult construction [11], interlayer temperature diffusion [12], and difficulty in temperature control [13] still exist. In recent years, the application of PCMs in the prevention and control of temperature cracks in mass concrete has gradually become a research focus in the academic community [14,15]. PCMs can absorb and release a large amount of latent heat near their phase change temperature. When incorporated into concrete, PCMs can effectively alleviate the problems of excessive hydration heat peaks and excessively large internal temperature gradients [16], thereby reducing the risk of temperature cracks. In addition, the incorporation of PCMs not only demonstrates significant advantages in autonomous temperature regulation, but also effectively reduces building energy consumption and waste gas emissions, thereby mitigating the negative environmental impacts [17,18].

Despite the extensive body of research on thermal cracking in mass concrete, existing studies remain fragmented across materials, construction processes, monitoring technologies, and numerical simulations, and lack an integrated framework for understanding and controlling cracking behavior. Moreover, critical challenges persist, including the limited engineering-scale validation of phase-change materials (PCMs), insufficient integration of multi-sensor monitoring systems into real construction workflows, and the absence of unified criteria for evaluating cracking risk and control effectiveness. To address these gaps, this review synthesizes thermal-cracking mechanisms, influencing factors, and prevention strategies, linking material optimization, construction technologies, PCM-based thermal regulation, intelligent monitoring and feedback systems, and numerical modeling into a coordinated prevention–control framework. By critically evaluating current limitations and identifying emerging opportunities, this work outlines a forward-looking roadmap for advancing low-heat materials, intelligent monitoring, adaptive construction control, and self-healing technologies, thereby providing a consolidated foundation for improving crack-control performance and long-term durability in mass concrete engineering.

2. Analysis of the Causes of Temperature Cracks in Mass Concrete

The temperature cracks in mass concrete are mainly caused by the combined action of temperature stress and structural stress, and their formation is affected by the coupling of multiple factors such as material properties, hydration heat process and construction environment.

2.1. Hydration Heat Effect

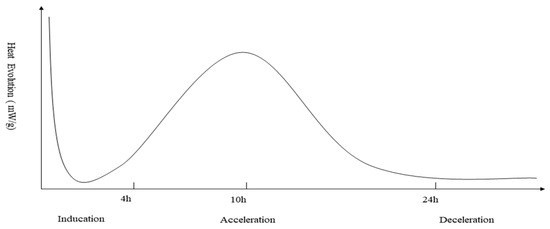

The hydration heat effect is one of the key factors leading to the formation of temperature cracks. The mechanism of calcium silicate hydration is generally divided into three stages: the induction period, the acceleration period, and the deceleration period [19], as shown in Figure 1. Under the combined action of the heat generated by cement hydration and thermal boundary conditions [20], resulting in the formation of a large temperature gradient [21,22]. With heat dissipation, the concrete temperature decreases after reaching its peak, leading to contraction; under restraint, this thermal contraction generates tensile stress that may cause cracking [23].

Figure 1.

Typical heat evolution curve of alite.

2.2. Temperature Gradient and Stress Distribution

The hydration heat in mass concrete dissipates slowly, creating a pronounced temperature gradient that induces differential thermal deformation between the inner and outer layers, leaving the interior under relatively high tensile stress. Huang et al. [2] found that the maximum temperature difference between the center and the surface of the concrete reached 30.6 °C. This temperature gradient further exacerbates the inconsistent deformation between the inner and outer layers of concrete during the thermal expansion and contraction process. Simulation results [24] indicated that tensile stress accumulates in the core during hydration, producing a persistent stress gradient responsible for shrinkage and restrained cracking [25]. The combined effects of thermal and hydration shrinkage introduce uncertainty in crack initiation and propagation. Hence, understanding the internal temperature gradient and stress evolution during construction is crucial for the effective prevention and control of cracking in mass concrete.

2.3. Material Properties and Environmental Factors

Both material properties and construction environment have a significant impact on the formation of temperature cracks in mass concrete. The thermophysical properties of aggregates determine their temperature deformation capacity to a certain extent. Aggregates with a low expansion coefficient help reduce deformation caused by temperature differences, thereby decreasing the accumulation of temperature stress [26,27].

The inherent properties of cement are the core factors affecting the early-age hydration heat and temperature stress of concrete, among which the mineral composition, fineness, and water to cement ratio of cement all play key roles. The mineral composition and hydration exothermic characteristics of cement directly determine the early-stage internal heat accumulation and temperature stress level of concrete. The order of hydration heat release per unit mass of the four main minerals in cement is as follows [28]: Tricalcium aluminate (C3A) > Tricalcium silicate (C3S) > Tetracalcium aluminoferrite (C4AF) > Dicalcium silicate (C2S). Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) has a high content of C3S and C3A, which leads to a fast hydration rate and concentrated heat release [29]. Meanwhile, water to cement ratio and cement fineness also have a certain impact on the early age hydration heat of concrete: when the water–cement ratio is greater than 0.4, the hydration rate and heat release increase significantly with the increase in water to cement ratio [22]. Termkhajornkit et al. [30] found through experiments that when the cement fineness increased from 3500 cm2/g to 6600 cm2/g, the early age hydration reaction rate accelerated significantly, and the hydration degree at the same age was higher.

In terms of fillers, the incorporation of mineral admixtures can not only reduce the hydration heat release rate and total amount, but also significantly decrease the maximum temperature (temperature peak) and temperature gradient inside concrete, thereby inhibiting the accumulation of temperature stress [31]. Fly ash (15–30% replacement) participates in pozzolanic reactions with Ca(OH)2, reducing the heat release from C3A and C3S hydration and decreasing the early age heat peak by 18–22%. [32] When ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS) is used at a dosage of 20–50%, its hydration heat is only 60–75% that of OPC, which can directly reduce the internal maximum temperature by 3–5 °C [33]. Therefore, the rational optimization of mineral admixture dosages is crucial for the temperature control of mass concrete [34].

Both the concrete placement temperature and the temperature-humidity conditions of the construction environment play a key role in controlling temperature cracks. An increase in concrete placement temperature significantly raises the temperature rise amplitude of the concrete core, accelerates the early stage hydration rate, and advances the occurrence time of the peak temperature [35]. The placement temperature is not only closely related to the mixing temperature but also affected by the number of transportation times, transportation distance, transportation method, and construction climate [36]. In addition, in both high temperature and low temperature environments, concrete will develop a temperature difference gradient, leading to the formation of temperature cracks [37]. Liu et al. [38] showed through their research that in the early hydration stage of mass concrete, surface cracks are relatively easy to form under the effect of temperature differences; during the cooling stage, the shrinkage effect under external constraints is more likely to induce penetrating cracks. In terms of humidity, a low humidity environment accelerates the evaporation of water in concrete, intensifies surface drying shrinkage, and thereby increases the possibility of crack occurrence [39]. Yuan et al.’s [40] research on mass concrete indicated that under high temperature and low humidity conditions, the temperature and humidity of concrete fluctuate drastically within the loading age of 0.6–1 day; the drying shrinkage of the structural surface is restrained by the internal concrete, generating high tensile stress and making the surface highly prone to cracking.

2.4. The Influence of Structural Dimensions

As the member thickness increases, the internal temperature accumulation effect of concrete becomes more pronounced, leading to a slower cooling rate and a larger temperature gradient, thereby increasing the probability of temperature crack occurrence. Ta et al. [41] employed the finite element method to simulate the temperature evolution and crack development of mass concrete with varying dimensions. They found that, under identical insulation and mix conditions, when the foundation’s volume to surface ratio is below 1.3 m, the maximum temperature difference increases while the minimum crack index decreases with increasing volume. Similarly, Ulm et al. [42] demonstrated through finite element simulations that the hydration heat diffusion length l can quantify the sensitivity of early age concrete structures, the smaller the l, the higher the cracking risk. Carey et al. [43] experimentally monitored internal temperature changes during hydration and confirmed that, although specimens of different sizes exhibit similar heat release trends, larger members show higher overall temperature rises and greater sensitivity of structural performance to temperature variation.

2.5. Summary of Review

Thermal stress and structural stress are the primary causes of thermal cracks in mass concrete. Material properties, hydration heat, and construction environment further influence crack formation through a coupling effect. The prevention and control of such cracks require collaborative efforts from multiple dimensions. In terms of materials, optimize the thermophysical properties of aggregates and reasonably select the components of cementitious materials to regulate the release law of hydration heat; at the construction level, strictly control the temperature of concrete at the time of placing and accurately monitor the temperature and humidity of the construction environment to reduce the adverse effects caused by temperature differences and drying shrinkage; in terms of structural design, scientifically arrange cooling systems in combination with the dimensions of components to alleviate the internal temperature accumulation effect.

3. Materials and Construction

3.1. Optimization of Traditional Cement Materials

3.1.1. Selection of Cement Types

As the primary binder in concrete, the cement type is a decisive factor governing the performance evolution and crack control of mass concrete. Compared to OPC, Low Heat Portland Cement (LHC) is chemically optimized by increasing the content of C2S while strictly limiting the proportions of highly exothermic phases, namely C3S and C3A [44]. Given that the rapid hydration of C3S and C3A governs early-age heat evolution, their reduction fundamentally mitigates the thermal load. Research confirms that the maximum heat release rate of LHC is 12.5% lower than that of OPC, with a 19.9% reduction in cumulative hydration heat over 70 h [45]. Furthermore, the microstructure of hydrated LHC is denser than that of OPC, contributing to superior compressive strength [46].

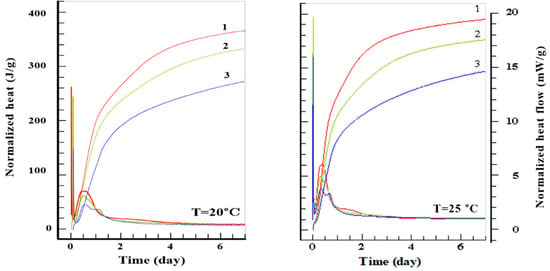

Recent investigations by Kiernożycki and Błyszko [47] revealing that Blastfurnace cement (CEM III 42.5 N) generates substantially lower total heat (272–330 J/g) over a 7-day period compared to high-strength Portland cement (CEM I 52.5 R, 366–396 J/g). As shown in Figure 2, the heat flow curves clearly illustrate that the slag-based cement exhibits a delayed and suppressed hydration peak compared to the sharp exothermic peaks of OPC. This reduction is predominantly driven by the reduced clinker fraction. However, a critical nuance lies in the non-linear dependence of hydration kinetics on curing temperature. Specifically, Blastfurnace cement demonstrates greater temperature susceptibility compared to OPC. Notably, elevated temperatures were found to induce a ‘third hydration peak’ in slag-based cements, a phenomenon driven by the thermally accelerated activation of slag via Ca(OH)2 and sulfate ions. Similar findings were reported by Zhang et al. [47] and Shabab et al. [48], confirming that while incorporating mineral admixtures effectively lowers the total heat load, the dynamic sensitivity of reaction rates to temperature must be rigorously accounted for to prevent temperature-induced cracking.

Figure 2.

Influence of different cement types (CEM I 52.5 R, CEM II 42.5 R, CEM III 42.5 N) on cumulative heat release and heat flow under curing temperatures of 20 °C (left) and 25 °C (right).

Therefore, in the mix design of mass concrete, prioritizing Medium to Low Heat Cements or incorporating Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCMs) like fly ash and slag remains the optimal strategy to moderate heat evolution and delay the thermal peak.

This figure compares the hydration heat evolution of CEM I and CEM III cements at 20 °C and 25 °C. The delayed and suppressed heat peak of slag-based cement (CEM III) highlights its superior ability to reduce early-age temperature rise and mitigate thermal-cracking risk in mass concrete.

3.1.2. Aggregates and Gradation

The main functions of aggregates in concrete are to reduce cement dosage, form the skeleton of concrete, and exert a certain inhibitory effect on the volume deformation of the paste. The thermal properties and particle gradation of aggregates have significant impacts on the temperature rise and thermal stress of concrete.

There are significant differences in the coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) among aggregates of different rock types, which directly affects the deformation and stress level of concrete when subjected to temperature changes. A higher CTE is more unfavorable to concrete. Siliceous aggregates (e.g., quartzite) have a relatively high CTE, which can reach approximately 2.5~3.6 × 10−6/°C, while the CTE of aggregates made from carbonate or basic rocks such as pure limestone, basalt, and granite is about 0.7~2.5 × 10−6/°C, less than half of that of siliceous aggregates [48]. A study by SIDDIQUI et al. [49] has confirmed that replacing aggregates with high CTE with those with low CTE can significantly reduce the CTE of concrete and enhance the crack resistance of concrete.

The thermal conductivity of aggregates also influences the internal temperature gradient of concrete. As aggregates do not generate heat, they absorb part of the hydration heat and transfer it outward, thereby reducing the temperature peak and promoting heat dissipation. However, higher aggregate thermal conductivity does not necessarily lead to better overall concrete performance. Klemczak et al. [50,51] conducted studies on four types of aggregates (gravel, basalt, granite, and limestone) and measured their thermal conductivity. The experiment used concrete mixtures with different types of cement and two types of aggregates, as shown in Table 1. Among them, Type A concrete was used with gravel and limestone aggregates, while Type B concrete was composed of basalt and granite aggregates. The measured results of thermal conductivity are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Concrete mix composition [51].

Table 2.

Influence of cement and aggregate type on concrete thermal conductivity [51].

Although gravel aggregates have the highest thermal conductivity, the concrete incorporating them exhibits the highest cracking risk. This is attributed to the significant volume change caused by the high CTE and high shrinkage of gravel aggregates, where the resulting thermal stress exceeds the gradually increasing tensile strength of concrete. Meanwhile, the excessively fast heat diffusion rate leads to the premature occurrence of stress, which further intensifies the cracking risk. Batog et al. [52] similarly reported that gravel aggregates can promote crack initiation through thermal stress accumulation under adverse conditions, and recommended granite, basalt, or limestone as preferred aggregates for mass concrete. Therefore, aggregate selection should prioritize low CTE and balanced thermal properties rather than high conductivity alone.

On the other hand, the particle gradation of aggregates exerts a certain influence on the mesoscopic hydration properties of concrete. Zhou et al. [53] investigated the effect of gradation on the early age hygrothermal and chemical properties of concrete, and found that aggregate gradations with low particle sizes (5–20 mm, 20–40 mm) can reduce the depth of influence of surface drying, thereby mitigating the negative effect of drying on surface humidity. They further suggested that such gradations be applied to the surface layer of mass concrete.

3.1.3. Incorporation of Admixtures

In mass concrete, admixtures have evolved from auxiliary additives into essential components for controlling thermal stress and early age cracking. Appropriate selection of admixtures can regulate hydration kinetics, refine the microstructure, and compensate for shrinkage while maintaining mechanical performance. Commonly used admixtures include retarders, expansive agents, and water reducers.

A retarder is an admixture that delays cement hydration and extends the setting time of fresh concrete. Its use moderates heat evolution, thereby reducing thermal stress and the risk of cracking in mass concrete [54]. In high temperature environments, the setting rate of concrete accelerates significantly with increasing temperature, which shortens the workable time and is unfavorable to the overall placement and quality control of mass concrete structures. Under such climatic conditions, the addition of retarders becomes a key technical measure [55].

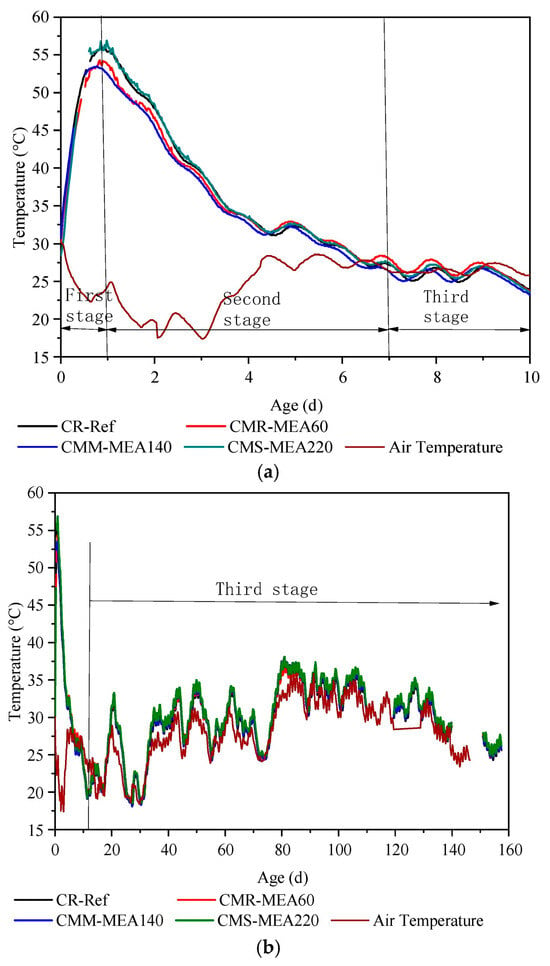

Expansive agents are generally classified into three types: CaO based, Aft based, and MgO based. CaO based agents are rarely used in practical engineering because of their excessively rapid hydration and the high solubility of the resulting calcium hydroxide. The expansion performance of Aft based agents depends on external water supply, limiting their effectiveness in the low permeability environment of high-performance concrete. Moreover, since ettringite decomposes at temperatures above 70 °C, Aft based agents are unsuitable for mass concrete under high temperature conditions [56]. In contrast, MgO-based expansive agents (MEAs) can compensate for the early autogenous shrinkage, drying shrinkage, and late age thermal shrinkage of concrete simultaneously, exhibiting a good crack resistant effect [57,58]. Figure 3 shows that the temperature evolution of concrete with MEAs of different activity levels governs the kinetics of MEA hydration. The moderate-activity MEA140 achieves the most effective coupling between hydration-expansion and shrinkage evolution, avoiding the premature expansion of MEA60 and the delayed response of MEA220. This better timing of expansion makes MEA140 more effective in reducing shrinkage and preventing cracking in mass concrete.

Figure 3.

(a,b) Temperature evolution of concrete incorporating MEAs with different activity levels and its influence on hydration–expansion behavior [59].

Water reducers can reduce the mixing water dosage while maintaining a constant slump, thereby reducing the required cement dosage accordingly. In mass concrete, high-efficiency water reducers can lower the water to binder ratio and cement dosage while preserving workability, thus effectively controlling hydration heat. Currently, the concrete water reducers widely used in the market are mostly naphthalene-based water reducers and polycarboxylate based water reducers, with a small proportion being lignosulfonate-based water reducers. Han et al. [60] studied four xylonic acid-based water reducers. At a dosage of 0.2%, these admixtures significantly enhanced the mechanical performance of concrete without affecting its slump. Compared with the blank group, the compressive strength increased by approximately 35% and 27% at 7 and 28 days, respectively, while the flexural strength rose by about 25% and 8%. Relative to the sodium lignosulfonate (SL) reducer, both strengths were further improved by 5–10%.

In mass concrete, admixtures are key materials for regulating cracks and optimizing performance. Different types of admixtures function through distinct mechanisms: retarders can delay cement hydration, regulate the release of hydration heat, and simultaneously improve workability under specific environments; expansive agents can targetedly compensate for concrete shrinkage, and some types exhibit better crack-resistant effects due to their superior adaptability; water reducers can reduce cement dosage and control hydration heat while ensuring workability, and some new type products can further enhance the mechanical properties of concrete.

3.2. Optimization of Key Construction Techniques

3.2.1. Pouring Sequence

For mass concrete with complex geometries or segmented construction, it is essential to reasonably plan segmentation, layering, and blocking to reduce thermal-cracking risk [61]. The pouring speed and segment length should be controlled to maintain a uniform temperature field, and the elevation difference between adjacent blocks should not exceed 10–12 m to avoid stress concentration at joints. The interruption time between pours must also be strictly managed to limit temperature differences between new and existing concrete and to ensure proper joint grouting. For layered pouring, the placement time of each lift should align with the hydration stage of the previous one to prevent temperature superposition. Dynamic temperature regulation during layer-by-layer construction further improves the uniformity of the internal temperature field and reduces the likelihood of thermal cracking [62].

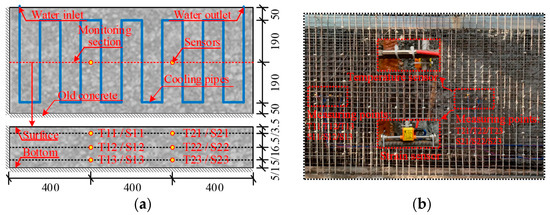

3.2.2. Cooling Systems

In the early stage of casting mass concrete, the high cement content releases substantial hydration heat, while the low thermal conductivity and large geometric dimensions of the structure hinder heat dissipation. Consequently, heat accumulates in the core, producing a pronounced temperature gradient between the interior and surface and inducing significant thermal stress [63]. To prevent cracking in mass concrete, a cooling system is installed inside mass concrete; the layout and composition of the system refer to Figure 4, which is designed to address the excessive heat generated during the engineering construction stage of mass concrete [64].

Figure 4.

Locations of cooling pipes and sensors: (a) schematic diagram (unit: cm) and (b) object pictures [65]. The layout directly influences cooling efficiency, thermal-stress reduction, and the effectiveness of construction-stage temperature control.

The cooling system was first applied in the Owyhee Dam project in Oregon [66], which significantly improved the temperature control effect during the concrete construction period. Since then, relevant studies have continuously expanded its application and optimization strategies. Lu et al. [67] combined cooling pipes with cold and heat sources to realize active temperature regulation of dam structures; Wang et al. [68] studied the layout parameters of cooling pipes in water tower concrete through numerical simulation and proposed an optimal spacing scheme to reduce early age thermal stress. Although the temperature control technology of traditional cooling systems is relatively mature in mass concrete construction and can effectively reduce the core temperature and the temperature difference between the inside and outside of concrete, there are still obvious limitations in practical application. The system design and installation are complex, requiring pre-embedded pipe networks in concrete and ensuring sealing performance; the cooling efficiency is highly sensitive to pipe diameter, flow rate, material thermal conductivity, and layout method; long-term operation consumes high energy; moreover, the inevitable mutual compression between concrete and pipes makes the structure prone to cracking.

In response to the above research, a variety of improved and alternative technologies have been developed subsequently, which can be roughly divided into three categories. The first is air cooling technology. For example, Yan et al. [69] adopted an air pipe cooling method based on pre-cooled air, eliminating the need for pre-embedding dedicated pipes in concrete. Li et al. [70] developed an automatic air cooling system, replacing cooling water pipes with air pipes or air ducts to avoid high energy consumption water circulation systems; their research showed that when the gas flow rate reaches 12 m/s, the risk of cracking can be significantly reduced. The second is flexible pipe design. Kheradmand et al. [71] designed flexible cooling pipes, which alleviate the mutual extrusion between concrete and pipes. These pipes can be recycled after concrete hardening, improving resource utilization efficiency. The third is optimization of cooling system layout and heat transfer. SEO et al. [72] pointed out that conventional cooling mostly adopts horizontal pipe arrangement, which is suitable for thick and large area structures; for slender concrete members, vertical pipe arrangement can be used to reduce cracking risk. Yang et al. [73] established a relational model between the thermal conductivity of pipe walls and concrete during the cooling stage, and derived a convective heat transfer coefficient function based on flow rate, pipe diameter, and pipe thickness.

Therefore, to achieve active regulation of the internal temperature of concrete while reducing the complexity and energy consumption of the temperature control system, it is necessary to explore and develop new temperature control approaches. PCMs can absorb or release a large amount of latent heat during the phase change process, endowing them with unique advantages in slowing down the temperature rise rate and reducing the peak temperature during the hydration heat generation stage. The combination of PCMs with concrete systems provides a new research direction and application prospect for active temperature control.

3.2.3. External Thermal Insulation and Heat Insulation

During the construction of mass concrete, to control the concrete temperature, thermal insulation is applied on the surface of mass concrete [74]. To enhance the thermal insulation performance, materials with low thermal conductivity are usually used as the thermal insulation layer [75]. Due to the presence of the thermal insulation layer, temperature changes in the ambient air do not directly affect the concrete interior. Consequently, only the region within the insulation layer experiences notable temperature variation and gradient increase, which effectively reduces the overall temperature gradient and surface thermal stress of the concrete. The thermal insulation materials and their characteristics are shown in Table 3:

Table 3.

Table of Thermal Performance and Application Characteristics of Different Thermal Insulation Materials.

In summary, external thermal insulation measures can significantly reduce the temperature difference between the interior and exterior of concrete, delay the temperature rise rate [84], and inhibit the formation of temperature-induced cracks, with their technical systems being relatively mature. However, the thermal insulation method is essentially a passive temperature control approach. Its mechanism of action mainly lies in weakening the convective heat transfer between the structure and the environment to reduce the surface temperature difference, while its ability to suppress the peak hydration heat inside the concrete is limited. In the context of long-term service and extreme climatic conditions, there are still deficiencies in its durability and stability.

3.3. Optimization of Phase Change Materials

Compared with conventional mix proportion optimization, thermophysical regulation and functional modification at the material level offer more active and intelligent strategies for mitigating temperature induced cracking in mass concrete. By incorporating aggregates with low thermal expansion coefficients, high thermal conductivity fillers, and other functional components, the thermal properties of concrete can be precisely tailored to delay the peak temperature and enhance heat dissipation. The introduction of PCMs represents a shift in temperature control strategies from passive mitigation to active regulation. Through latent heat absorption and release during phase transition, PCMs effectively buffer temperature fluctuations, thereby reducing temperature gradients and suppressing thermal stress development.

3.3.1. Mechanism of Temperature Control by Phase Change Materials

PCMs regulate temperature through latent-heat absorption and release during phase transitions, maintaining a stable thermal state and effectively mitigating rapid temperature fluctuations [85]. Their thermal control performance operates across multiple scales: at the pore scale, latent-heat effects slow the early age hydration temperature rise; at the meso scale, PCMs embedded in mortar or coated on aggregates modify local heat-transfer pathways and delay thermal conduction; at the structural scale, PCMs reduce peak temperature and attenuate temperature fluctuations, thereby limiting internal–external temperature differences and lowering the risk of thermal cracking in mass concrete.

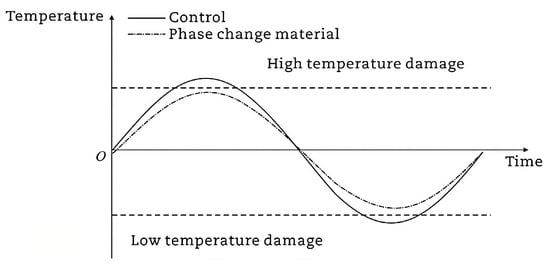

The model in Figure 5 illustrates the latent-heat absorption and release process of PCMs during phase transition.

Figure 5.

Temperature adjustment model of phase change asphalt pavement [86].

3.3.2. Types of Phase Change Materials

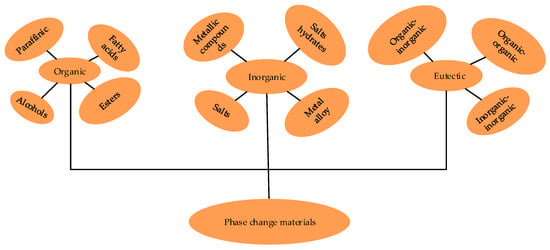

PCMs can be classified based on different characteristics, such as chemical composition, phase change form, and applicable temperature range (see Figure 6). Classified by chemical composition, PCMs mainly fall into three categories: organic PCMs, with common types including paraffins, fatty acids and their derivatives, and polyols. Their advantages lie in large phase change latent heat, good chemical stability, and the absence of supercooling and phase separation phenomena; however, they have drawbacks such as low thermal conductivity and flammability. Inorganic PCMs, which mainly include crystalline hydrated salts, molten salts, and low melting point metals or their alloys. They possess high phase change latent heat and thermal conductivity, but suffer from issues like poor thermal stability, phase separation, supercooling, and corrosiveness. Composite PCMs, composed of two or more types of materials. The purpose of compounding is to utilize the advantages of various composite materials to overcome the shortcomings of a single PCMs. Nevertheless, their application is limited due to high costs.

Figure 6.

Classification of phase change materials.

3.3.3. Incorporation Methods of Phase Change Materials

From the current research, the methods of incorporating PCMs into concrete mainly include direct incorporation and post-encapsulation incorporation. The direct incorporation method features simple process and low cost; however, the directly incorporated PCMs face the problem of leakage during phase transition, and the PCMs may react with the raw materials of concrete, which affects the durability and stability of concrete. Therefore, it is necessary to encapsulate PCMs before their incorporation into concrete.

- (1)

- Microencapsulation Method

This is a PCM encapsulation method that uses physical or chemical methods to coat solid–liquid phase change materials with synthetic polymer materials or inorganic compounds, thereby producing solid particles that are stable under normal conditions. This method can increase the specific surface area and thermal conductivity of PCMs, and improve the durability of PCMs. Currently, three main techniques are used for microencapsulating PCMs, including in situ polymerization, interfacial polymerization, and coacervation, with in situ polymerization being the most widely applied method

Choi et al. [87] successfully prepared microcapsules with melamine-formaldehyde resin as the shell and n-tetradecane as the core via in situ polymerization, using styrene-maleic anhydride methyl methacrylate copolymer as the emulsifier. Yoshinari et al. [88], on the other hand, developed phase change microcapsules with polymethyl methacrylate as the wall material and n-pentadecane as the core material. Cho JS et al. [89] fabricated the corresponding phase change microcapsules via interfacial polymerization, where the shell was formed by the polymerization of toluene diisocyanate and diethylethylenetriamine, with n-octadecane as the core material and NP-10 as the emulsifier. In addition, Hawlader et al. [90] synthesized spherical phase change microcapsules via the complex coacervation method, using gelatin and gum arabic as the composite wall materials and paraffin as the core material.

- (2)

- Porous Material Adsorption Method

The porous material adsorption method is a shape-stabilized encapsulation technique in which porous substrates are immersed in molten PCMs, allowing the liquid PCM to penetrate and fill the pore network This approach relies on surface adsorption within the pores to prevent leakage during heat absorption and release, while minimizing matrix cracking caused by volume changes. Common porous media used for PCM adsorption include expanded perlite, expanded graphite, montmorillonite, and ceramsite. Ahmet San et al. [91] fabricated shape stabilized PCMs by adsorbing fatty acids into expanded perlite and further enhanced their thermal conductivity by incorporating expanded graphite. The resulting composites exhibited good thermal stability and improved heat-transfer performance.

- (3)

- Melt Blending Method

The melt-blending method refers to a process where, at a temperature higher than the melting point of the high molecular polymer, PCMs and the high molecular polymer are melted and blended together. When the temperature drops to room temperature, the PCMs can be uniformly dispersed in the solidified high-molecular polymer, thereby achieving the goal of shaping the PCMs. Researchers often incorporate thermally conductive additives such as graphite and metal powder to improve the thermal conductivity of the PCMs prepared by this method. Ahmet Sari [92] used high-density polyethylene (HDPE) as the supporting material, two types of paraffin as the PCMs, and incorporated graphite to increase the thermal conductivity, thus preparing shape-stabilized P/HDPE PCMs. Table 4 shows the comparison of the effects of these three incorporation methods.

Table 4.

Comparison Table of the Effects of Different Doping Methods on Phase Change Material Properties.

As shown in the comparison data of Table 4, different PCM incorporation methods exhibit distinct thermal regulation characteristics. The microencapsulation method, by coating paraffins, fatty acids, and other PCMs in polymer or inorganic shell materials, can achieve a relatively wide phase change temperature range (13–58 °C). The incorporation amount is generally 3–30%, the maximum reduction in peak temperature can reach 13 °C, and the temperature rise or peak delay time is mostly between 0.3 and 8 h, making it suitable for precise temperature control. The porous adsorption method uses porous carriers such as lightweight aggregates, zeolites, and steel slags to adsorb PCMs. Its incorporation amount varies greatly, the reduction in peak temperature can reach 20 °C, and the delay time can be more than 17 h at maximum, exhibiting significant heat-storage and slow-release capabilities. The melt blending method involves directly mixing PCMs with the matrix. The temperature reduction range is generally 1.4–13 °C, the delay time is relatively short (0.16–2 h), and it has good structural stability and process simplicity.

3.3.4. Applications of Phase Change Materials

According to their functional roles in concrete, PCM applications can be generally classified into three types, with the first aiming to enhance thermal conductivity and energy storage. After incorporating composite microencapsulated PCMs into cement paste, Inaba et al. [110] found that the average thermal conductivity was increased by approximately 2.0–2.8 times compared with pure cement paste. Such materials achieve temperature control mainly by enhancing thermal conductivity and storing heat in key temperature zones, but it is necessary to minimize the adverse impact on mechanical properties while maintaining phase-change activity.

The second category is the fluid cooling coupling type. This method uses PCMs as the cooling medium and combines them with pipe embedded systems or external circulation devices to actively regulate the core temperature. Qian et al. [111] used a semi-adiabatic device and found that, compared with water cooling, PCM cooling fluid could improve the cooling efficiency by approximately 27–28% and reduce the internal to external temperature difference by 7.6–8.4%.

The third category is the phase-change energy storage coating type. By compounding PCMs with porous aggregates or mortar matrices and performing surface modification, their stable distribution in concrete can be achieved, and latent heat can be used to mitigate temperature fluctuations. Lu et al. [67] prepared high and low temperature phase change aggregates (with phase change temperatures of 42.2 °C and 5.51 °C, respectively) and incorporated them into mortar. Tests showed that compared with the control group, the internal external temperature difference of concrete coated with 10 cm thick PCM mortar was reduced by 68.36%, the time of peak temperature occurrence was delayed by approximately 3.9 h, and the minimum surface temperature was increased to 11.98 °C, which significantly reduced the risks of temperature cracks and freeze thaw damage. Kabay et al. [112] incorporated microencapsulated PCMs into LC3-based pavement materials, with the incorporation amounts accounting for 10% and 20% of the mass of cementitious materials. The results indicated that this method could effectively delay the decrease in surface temperature, and the number of applicable days for this method in winter accounted for approximately 40%; although the high incorporation amount (20%) slightly reduced the strength, microcapsule encapsulation effectively alleviated the impact on workability.

Incorporating the thermophysical parameters of PCMs into temperature field models enables in-depth analysis of their effects on heat absorption, release, and temperature distribution. Kheradmand et al. [113] used DIANA software to simulate mortar concrete containing different PCMs proportions and found that PCMs reduced early high-temperature fluctuations and smoothed temperature variations within their melting range. Proper dosage design effectively lowered the temperature peak and gradient induced by hydration heat, thus mitigating early cracking. Wang et al. [114] applied a finite element model (FEM) to analyze PCMs linings for high-geothermal tunnels, revealing that lower infrared absorptivity, narrower phase change ranges, and higher latent heat improved thermal performance. Chang et al. [115] enhanced concrete thermal performance using steel balls as PCM carriers and butyl stearate as the storage medium. Experiments and simulations showed that incorporating 10% coarse aggregate, 5% slag, and fly ash into C30 concrete significantly improved the heat transfer efficiency of energy piles. Overall, integrating PCM parameters into temperature field models optimizes internal temperature distribution and provides theoretical and practical guidance for temperature control in mass concrete.

In summary, PCMs can effectively reduce peak temperature and thermal gradients through latent heat exchange, offering clear potential for temperature control in mass concrete. However, challenges such as reduced workability, durability risks (including leakage and shell damage), high encapsulation cost, and uncertainties in field dispersion still limit their practical use. These issues also create opportunities for innovation. Advances in encapsulation durability, composite PCM design, cost reduction, and data-driven temperature prediction are improving engineering feasibility. Future work should strengthen PCM–matrix compatibility, verify long-term performance in real projects, and develop more economical and durable PCM systems.

4. Crack Monitoring and Control Measures

The initiation and propagation of cracks provide channels for aggressive ions, which accelerates steel corrosion, degrades durability, and may even lead to the loss of structural bearing capacity. Deploying crack sensors enables early detection and warning of cracks, effectively preventing structural disasters. Therefore, crack prevention and inhibition are key technologies for ensuring the long-term safety and durability of mass concrete structures. By real time monitoring of the internal temperature, stress state, and crack evolution in concrete, targeted control measures can be implemented promptly to effectively prevent crack propagation. This section will systematically elaborate on three aspects: temperature and stress monitoring, crack width monitoring and control, and feedback control technology.

4.1. Temperature and Stress Monitoring

4.1.1. Temperature Monitoring

During mass concrete construction, hydration-induced temperature variations are critical to structural quality and long-term performance. A multi-point sensor layout enables real-time acquisition of internal and surface temperatures and accurate characterization of spatiotemporal temperature differences, providing the basis for targeted temperature-control measures and mitigation of excessive thermal gradients [116,117], effectively reducing temperature gradients and preventing cracks and deformations caused by excessive temperature differences [118,119].

Traditional point-based temperature measurements offer limited spatial coverage, monitor only single locations, and cannot capture multiple parameters or support long-term performance evaluation [120]. Recent sensing advances address these limitations. Lin et al. [121] developed a BT–BFO/PVDF piezoelectric sensor capable of quantifying early-age strength with an error below 10%. Meanwhile, Liu et al. [122] proposed a Z-shaped DTS layout that provides real-time multipoint temperature monitoring while reducing fiber usage and cost, a finding also supported by Ouyang et al. [123].

Embedded ultrasonic sensing has been widely employed in non-destructive evaluation to monitor crack initiation by tracking changes in wave velocity, amplitude, and signal correlation. Experimental studies demonstrate that embedded ultrasonics can detect crack initiation and early propagation before surface cracks become visible, providing an effective means for internal defect assessment [124]. Furthermore, Zivanovic et al. [125] integrated infrared thermography with embedded sensing to achieve full-field surface temperature mapping, significantly enhancing the ability to capture early hydration heat development. Infrared thermography has also proven valuable for long-term monitoring of concrete structures, supplying essential temperature data for evaluating residual service life [126]. A broader comparison of these sensing technologies is summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of monitoring technologies for mass concrete.

In engineering practice, sensor integration has evolved toward multi-source and multi-scale monitoring. DTS/DOFS provides continuous temperature and strain information and is often combined with embedded piezoelectric or ultrasonic sensors for early stress and microcrack detection. Coordinated use of FBG systems and infrared thermography further enhances temperature–stress assessment, improving real-time evaluation of hydration heat, internal damage, and deformation

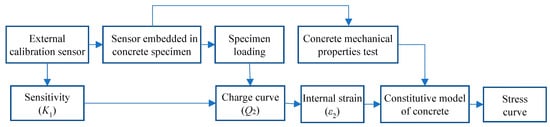

4.1.2. Stress Monitoring

The development of temperature-induced cracks is closely linked to the evolution of internal thermal stress, making the deployment of stress sensors at critical locations essential for crack prevention. Real-time stress monitoring enables accurate tracking of stress development under varying temperature conditions, allowing timely detection of tensile stresses approaching or exceeding safe limits and supporting targeted control measures [116,130]. Wu et al. [131] proposed a uniaxial piezoelectric sensing method whose charge output closely follows stress variations and remains insensitive to loading rate and stress mode (Figure 7). Liu et al. [132] further analyzed the effects of installation angle and interface roughness on embedded PZT sensors, demonstrating that a 90° configuration with optimized interface treatment provides superior sensitivity and reliability. These findings offer theoretical and experimental guidance for improving sensor configuration and enhancing the accuracy and robustness of internal stress monitoring in concrete.

Figure 7.

Flow chart of concrete stress monitoring based on uniaxial piezoelectric sensor [131].

4.2. Cack Width Monitoring and Control

4.2.1. Arrangement of Crack Sensors

Currently, the sensors applied to crack monitoring mainly include embedded ultrasonic sensors, distributed optical fiber sensors, and discrete strain sensors based on the theory of elasticity. A. Zang et al. [124] employed embedded ultrasonic sensors combined with acoustic emission and digital image correlation techniques to enhance the accuracy of crack initiation detection. Building on this, Sahay and Luo [133,134] introduced optical fiber based sensors, including bare single mode fibers and tapered polymer optical fibers, whose stress concentration effect significantly improves crack detection sensitivity. Extending from point to distributed sensing. Berroca et al. [128] developed a distributed optical fiber sensing (DOFS) system based on backscattered light frequency domain reflectometry, achieving crack localization and width measurement accuracies within ±3 cm and ±20 μm, respectively. Furthermore, Alsharqawi et al. [135] designed a discrete strain sensor network for concrete pavements based on linear elastic fracture mechanics, enabling accurate inference of crack position, depth, and propagation behavior through dense monitoring and inversion modeling.

Recent advances in crack monitoring have led to a transition from single point sensing to integrated, distributed, and networked systems. These advancements have significantly improved the sensitivity, spatial resolution, and intelligence of crack detection, thereby providing a robust foundation for real-time and quantitative structural health assessment.

4.2.2. Width Control and Early Warning

In the field of concrete crack detection, various factors such as blurry backgrounds, crack directions, and crack widths can unpredictably affect detection results [136]. To mitigate these issues, Lu et al. [137] leveraged the advantages of Transformer architectures in computer vision for crack identification. The Swin Transformer (ST), which employs a window-based self-attention mechanism, enhances global feature extraction but remains inferior to the UNet model in capturing local features [137,138,139]. Further, Zhang et al. [136] developed an improved ST-UNet (I-ST-UNet) model that achieves dual improvements in crack detection accuracy and width estimation, establishing a foundation for real-time early-warning systems. In addition, Sun et al. [140] introduced quantitative indicators to evaluate the severity of complex regional cracks and utilized the ST to automatically classify crack severity in panoramic images, providing valuable references for maintenance planning and safety assessment.

Overall, current deep learning and computer vision-based methods have substantially enhanced the accuracy and efficiency of crack identification, providing crucial technical support for quantitative crack width evaluation and the development of structural early-warning systems.

4.3. Feedback Control Technology

Building on real-time sensing information, feedback control technology enables dynamic tracking of temperature and stress evolution within concrete. By responding promptly to unfavorable thermal–mechanical conditions, it can effectively suppress crack initiation and propagation and improve the adaptability of mass concrete under complex construction environments. Consequently, structural safety and stability are significantly enhanced during both construction and early service stages.

4.3.1. Feedback Control Based on Temperature Monitoring

Feedback control technology based on real time temperature monitoring is the core of intelligent cooling systems for mass concrete. It automatically activates cooling when temperature thresholds are exceeded and dynamically adjusts water temperature and flow rate, effectively suppressing hydration heat and ensuring precise temperature control for crack prevention. Ju et al. [141] analyzed the characteristics of heat accumulation and dissipation in the early temperature field and, combined with vertical temperature gradient monitoring, implemented layered casting, thermal insulation curing, and real-time regulation measures. These strategies effectively controlled the temperature difference of the wind turbine foundation within 25 °C, thereby preventing early thermal cracking. Lin et al. [142] developed an intelligent cooling control system based on real time temperature data transmission. By integrating temperature sensing and data processing modules, the system achieves active control of temperature deformation of mass concrete, ensuring the structural integrity of large concrete structures during construction. It is particularly suitable for important projects sensitive to thermal stress, such as high arch dams. Compared with traditional systems that rely on manual data collection, the intelligent cooling system provides an intelligent, time sensitive, and precise technology for temperature control and cracking prevention of dam concrete.

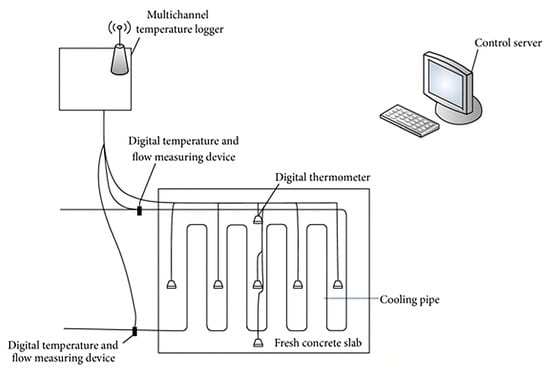

The system in Figure 8 forms the basis of real-time feedback temperature regulation, enabling dynamic adjustment of cooling intensity to suppress thermal cracking.

Figure 8.

The schematic diagram of temperature and flow acquisition, collecting, and analyzing system [142].

4.3.2. Feedback Control Based on Stress Monitoring

When the monitored tensile stress exceeds the material’s critical strength, the feedback control system automatically activates stress-relief measures, thereby limiting crack initiation and propagation [143]. Such stress-based control supports temporary reinforcement and structural strengthening, while reducing crack growth caused by stress concentrations and enhancing overall durability [129]. He et al. [144]. applied an FBG sensing system to monitor temperature and stress fields during the construction of a mass raft foundation. The system integrates multiple sensors, a high-speed data acquisition unit, and an intelligent warning module. Real-time analysis of coupled temperature–stress data showed that the maximum horizontal displacement predicted by the linear full-sliding model (2.209 mm) closely matched field measurements, confirming its accuracy and feasibility during construction. Nonetheless, its long-term applicability—particularly parameter updating, performance under complex boundary conditions, and robustness—requires further verification.

Future research should focus on multi-source data fusion, incorporation of nonlinear mechanical effects, and adaptive model updating to improve the reliability and lifecycle applicability of feedback control systems.

4.3.3. Intelligent Control System

In recent years, the rapid development of the Internet of Things (IoT) and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies has driven technological transformation in the field of temperature crack prevention and control for mass concrete. Zhang et al. [145] constructed a temperature-stress simulation and inverse analysis system, which can real-time integrate multi-source monitoring data during the construction phase and automatically generate calculation files. Relying on a high-performance computing platform, the system realizes remote real-time simulation and feedback, thereby achieving dynamic tracking of the concrete’s temperature-stress state and early warning of cracking risks. Ouyang et al. [123] proposed a crack control framework based on DTS. This framework acquires continuous temperature data through an optical backscatter reflectometer (OBR), achieve accurate assessment and prediction of crack occurrence risks.

In summary, AI technology extracts key features from large scale monitoring data to improve the accuracy and efficiency of predictive models, while the Internet of Things (IoT) ensures real time performance and interconnectivity of monitoring systems. This intelligent “perception–computation–feedback” framework can significantly enhance the safety and durability of mass concrete throughout its life cycle. However, issues such as data transmission stability, algorithm generalization under complex conditions, and long-term model adaptability still require further study.

5. Numerical Simulation and Model Prediction

Numerical simulation has become an important means to predict the evolution of temperature field, stress field and fracture development under hydration heat [146]. The researchers combined numerical simulation with field monitoring and introduced field monitoring parameters to dynamically calibrate the model [147], and the accuracy of fracture risk prediction and the effectiveness of fracture control are obviously improved. This section provides a systematic review of numerical simulation and model prediction of hydration heat of mass concrete.

5.1. Temperature Field Simulation

Most codes provide exponential or logarithmic fitting formulas based on adiabatic temperature rise curves for fast estimation of temperature rise amplitude. However, Smolana et al. [148] confirmed through an engineering case comparison that although the analytical method is simple, its applicability is mainly limited to risk pre-assessment at the initial stage of design due to a large number of simplifications and neglect of spatial effects and structural constraints, and it still depends on numerical simulation at the level of fine analysis and construction control.

5.1.1. Governing Equations and Heat Source Functions

The core of temperature field simulation lies in solving the heat conduction equation, with the heat generated by cement hydration incorporated as a heat source function. According to Fourier’s theory of heat conduction, the heat flux in a solid is proportional to the temperature gradient and oriented in the opposite direction. In accordance with the law of conservation of energy, the energy required for a temperature increase equals the sum of the external heat inflow and the internal heat released from hydration. From this, the governing equation for the concrete temperature field can be derived, namely the heat conduction differential equation:

where T is temperature, τ is time, x, y, and z are spatial coordinates, a is thermal diffusivity, θ is specific heat capacity, ρ is density, and λ is thermal conductivity.

The heat source function is a key input in temperature field simulation, and its accuracy directly affects the physical reliability of computational results. Any deviation in this function undermines the mechanistic basis of temperature field analysis and introduces systematic errors into stress and crack predictions. Currently, most heat source functions for concrete hydration are derived from empirical formulas, which fail to fully capture the effects of material properties and environmental conditions, despite their significant influence demonstrated in existing studies. Klemczak et al. [149] compared the effects of different aggregates on thermal conductivity and the coefficient of thermal expansion, finding that quartz aggregate, owing to its high thermal conductivity, can reduce temperature gradients and thereby lower the risk of surface cracking. Zhao et al. [150] through temperature humidity coupling experiments, revealed that the evolution of early-age relative humidity is closely correlated with the temperature rate, emphasizing that the humidity field should not be overlooked. In addition, Do and Hoang [151] employed a three-dimensional finite difference model to conduct an activation energy sensitivity analysis, demonstrating that variations in Ea exert a 5–10% influence on peak temperature rise and temperature differentials. It is therefore evident that future development should focus on combining high-precision characterization of the heat source function with multi-field coupling models, and dynamically calibrating them using monitoring data, so as to provide critical support for intelligent construction of mass concrete.

5.1.2. Boundary and Initial Conditions

After establishing the governing equation and heat source of the temperature field, appropriate boundary and initial conditions must be defined. Improper settings can cause significant deviations from actual conditions or even lead to numerical divergence.

For mass concrete, its outer surface typically exchanges heat with the ambient air through convection and radiation. Zhou et al. [152] simulated the temperature field of a high-rise building raft foundation using MIDAS software, and inverted the convective heat transfer coefficient based on measured temperature data. They found that variations in wind speed and surface roughness can cause a computational error of ±15% in the convective heat transfer coefficient. For concrete exposed to high-temperature or strong-radiation environments, surface heat exchange involves not only convection but also the contribution of radiation. Wang et al. [153] incorporated the Stefan–Boltzmann law into the heat balance equation, with results indicating that when the surface temperature exceeds 60 °C, radiative heat transfer can account for up to 20% of the total heat transfer. In humid environments or where temperature fluctuations are significant, it is also necessary to consider the coupled transfer of heat and moisture. Pečenko et al. [154] based on the Luikov equations, introduced composite temperature–humidity boundaries, and found that in humid environments, humidity fluctuations can lead to a peak deviation of up to 10% in the temperature field, thereby underscoring the importance of boundary conditions in temperature–humidity-coupled simulations.

The setting of the initial temperature not only determines the starting point of the early-stage temperature rise curve but also affects the timing of the peak occurrence and the prediction of temperature differentials, making it critical for temperature field simulation. Zhou et al. [152] assumed a uniform initial casting temperature, but pointed out that in practice, layered casting tends to form a gradient, which needs to be corrected using measures such as cooling pipes. Nguyen-Ngoc et al. [155] proposed a gradient-type initial temperature model and solved it using the finite difference method. They found that for every 1 °C/m increase in the gradient coefficient β, the peak temperature deviation increases by approximately 3%.

In summary, the selection of boundary and initial conditions is essential for ensuring both the physical realism and numerical stability of temperature field simulations. In recent years, research has shifted from empirical assumptions to inversion and intelligent optimization based on monitoring data, enabling more accurate parameter identification. Moreover, the incorporation of multi-physics coupled boundaries and dynamic initial hydration degrees has introduced new approaches for analyzing the temperature behavior of mass concrete under complex early-age environmental conditions.

5.1.3. Sensitivity Analysis and Result Verification

Conducting sensitivity analysis and uncertainty quantification (UQ) for temperature field models of mass concrete is a key step in transforming numerical simulation results into engineering-useful information. Sensitivity analysis aims to identify the input parameters that have the greatest impact on model outputs (e.g., peak temperature rise, maximum internal–external temperature difference, or temperature gradient), whereas uncertainty quantification characterizes the propagation of these uncertainties in the outputs and provides confidence intervals or probabilistic measures for risk assessment and decision-making. Gaspar et al. [156] combined RBD-FAST (Random Balance Design—Fourier Amplitude Sensitivity Test) with a thermo–chemical–mechanical-coupled model to perform probabilistic sensitivity analysis of the dam temperature field. The results indicated that the thermal properties of the material, particularly thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity, contribute the most to the overall uncertainty of the temperature field (contribution rate > 60%), while the sensitivity of parameters related to the rate of hydration heat release to temperature response decreases with age. This study emphasizes the need to prioritize accurate measurement of thermal parameters in early- and mid-stage analyses to enhance the reliability of predictions.

Xie and Qian [157] employed a BP neural network calibrated through semi adiabatic heat release tests to optimize the parameters of the heat source function, which was then coupled with the finite element method for sensitivity analysis. The results indicated that activation energy and the initial degree of hydration significantly affect early age peak temperatures, with prediction errors of up to ±15%. In addition, the content of supplementary cementitious materials strongly influences the delay of temperature rise. This approach effectively integrates experimental data with numerical modeling, achieving an empirical mechanistic hybrid correction of the heat source function.

It is noteworthy that current research has primarily concentrated on the uncertainty of short-term (early-age) thermal responses, while uncertainty quantification for long-term responses and multi-scale coupled processes remains inadequate. Meanwhile, for novel temperature-control materials such as PCMs, their parameter uncertainties and the effects on temperature field prediction still require in-depth investigation.

5.2. Stress Field Simulation

5.2.1. Thermo–Mechanical Coupling Mechanism

In the early age of mass concrete, the core of thermo-mechanical coupling research lies in elucidating the combined effects of temperature gradients and volumetric restraints on material deformation, stress evolution, and damage development. Early on, Lothenbach et al. [158] based on thermodynamic modeling, analyzed the influence of temperature on the stability and volumetric properties of hydration products, and proposed that thermal effects can alter the elastic modulus and coefficient of linear thermal expansion, thereby providing key material property foundations for stress evolution analysis. Subsequently, Zhang [159] proposed a model describing the evolution of the modulus with temperature during the early hydration of C3S, emphasizing the coupled characteristics of elastic modulus degradation and stress relaxation under high-temperature conditions. Yu et al. [160] established a temperature-driven damage evolution equation within a pseudo-elastoplastic framework to characterize the crack propagation rate of high-toughness ECC materials under complex temperature gradient effects.

5.2.2. Multi-Field Coupling

The heat conduction equation or a single heat-of-hydration model can no longer adequately capture the complex thermo–mechanical–hydrological interactions in the early age of mass concrete. To address this, researchers have progressively developed multi-field coupling models, in which factors such as hydration kinetics, moisture migration, autogenous shrinkage, creep, and restraint effects are incorporated on the basis of the temperature field to establish a more realistic analytical framework.

Its core concept is to use the degree of hydration as the primary governing variable, driving heat release through kinetic equations while dynamically updating the thermal and mechanical properties of concrete. By simultaneously incorporating humidity variations to account for self-drying and environmental effects, this approach provides a more realistic representation of early age behavior. Existing studies have demonstrated that such multi-field coupling more effectively reveals the fundamental mechanisms of temperature-induced cracking. Zhou et al. [161], based on a multi scale C–T–M model, compared the thermo-mechanical responses of different cementitious materials. The results indicated that concrete prepared with supersulfated cement (SSC) exhibited significantly lower heat of hydration than that with OPC, with reductions in both peak temperature rise and thermal stress, thereby potentially reducing or even eliminating the need for cooling measures. Wang et al. [153] proposed a unified “hydration–temperature–humidity–restraint” multi factor model and applied it to comparative studies between ordinary concrete and low temperature-rise materials. The findings revealed that material modification not only reduces peak temperature but also alleviates tensile stress concentrations induced by environmental wind speed and boundary restraints.

These findings highlight the advantages of multi-field coupling in elucidating the interaction mechanisms among material, structure, and environment. However, multi-field coupling models require a large number of parameters, including hydration kinetics parameters (such as activation energy and reaction rate constants), thermal parameters, moisture migration parameters, and mechanical property indices that evolve with age. The acquisition of these parameters necessitates extensive experimental support. Secondly, model coupling introduces computational complexity, particularly in large three-dimensional structures, where nonlinear iterations and simultaneous equations with multiple variables may lead to a sharp increase in computational demand, thereby limiting its real-time application in engineering practice.

5.2.3. Multi-Field Models

The phase-field and energy-driven damage models can realistically reproduce the entire process of crack initiation and propagation, significantly improving the mechanistic reliability of simulations [154,155]. With further research progress, crack simulation has evolved from mechanism-based modeling to integrated engineering applications. A thermo–hydro–mechanical (THM) coupling model has recently been developed and validated in practical projects, achieving deviations within 5.5%. Results show that different temperature control measures exhibit varying effectiveness in reducing cracking and mitigating the risk of delayed ettringite formation (DEF). Cooling pipes and layered casting effectively lower peak temperatures and temperature gradients, while aggregate substitution and mix proportion optimization help alleviate thermal expansion effects. In contrast, thermal blankets, although reducing surface temperature differences, may raise core temperatures excessively, thereby increasing the risk of DEF.

The finite element method (FEM) remains the mainstream approach for numerical simulation of mass concrete, capable of handling complex geometries and multiple boundary conditions. Yu et al. [162] constructed a flow thermal coupling model based on COMSOL, accurately reproducing the heat exchange of cooling water along its path and the local temperature gradients, and pointed out that excessively strong cooling may induce stress concentrations. In comparison, the finite difference method (FDM) exhibits higher efficiency in three dimensional problems. Do and Hoang [151] demonstrated that it offers greater advantages in capturing corner points and longitudinal temperature distributions. Fraga et al. [163] proposed a mesoscale cooling equivalence method, which effectively reduces the computational cost of discretely modeling cooling pipes.

In summary, research on crack simulation and numerical methods is showing a clear trend from mechanism-based modeling toward engineering applications. On one hand, phase field and multi field coupling models have enhanced the scientific rigor of crack prediction and the comparative evaluation of prevention measures; on the other hand, advances in FEM, FDM, and mesoscale equivalence methods have continually improved the accuracy and efficiency of simulating the temperature and stress fields in mass concrete. The combination of these approaches provides an important guarantee for the quantitative design of temperature-control and crack-prevention measures in engineering practice.

5.3. Prediction of Cracking in Mass Concrete Structures

Traditional experience and methods find it difficult to quantify the internal stresses during the construction of mass concrete, making it challenging to predict cracking risks in advance and to identify weak points. Wu et al. [164] proposed using three dimensional FEM to simulate the transient temperature and thermal stress of mass concrete structures during construction, demonstrating the feasibility of numerical simulation in crack prediction. Subsequently, Li et al. [165] further extended the application of the FEM achieving dynamic reproduction of crack development in masonry under the action of temperature-induced stress. Li et al. [165] based on the ANSYS platform, systematically analyzed the temperature field and temperature stress of large concrete blocks, clarifying the dominant role of temperature variation in crack formation.

Building on this foundation, models have evolved toward multi-factor coupling. Zhu et al. [166] through integrating finite element algorithms, developed a coupled field model and proposed a computational method for concrete crack propagation, capable of accurately and stably simulating the evolution of early age thermal cracks in mass concrete. Chiniforush et al. [167] proposed a multiphysics model for predicting early-age thermal cracking. Xu et al. [168] based on a thermodynamic theoretical framework and the phase field method, developed a coupled model that incorporates time dependent material parameters such as hydration heat, creep characteristics, and autogenous shrinkage, thereby more accurately revealing the distribution characteristics of thermal stresses as well as the mechanisms of crack initiation and propagation.

Research on crack simulation has expanded from single-field analysis to a framework that integrates multi-field coupling with real-time monitoring. This advancement has enhanced the mechanistic soundness and predictive accuracy of the models, providing practical and feasible technical support for crack prevention and temperature control optimization in mass concrete.

5.4. Construction Control and Curing Decisions

In recent years, numerical simulation has gradually become a key tool for temperature control and crack prevention in mass concrete, with its application range extending from temperature field prediction to construction process optimization and risk assessment. Zhao et al. [169] used ABAQUS to simulate tunnel lining and found that when the layer thickness was reduced from 2.5 m to 1.5 m, the peak temperature decreased by approximately 6.2 °C and the maximum temperature difference was reduced by 18%, significantly mitigating the risk of early age cracking. Wang et al. [170] demonstrated through numerical optimization of cooling pipe parameters that when the cooling water flow rate was increased from 0.5 L/s to 1.0 L/s, the peak temperature decreased by 7–9 °C and the maximum temperature difference dropped by approximately 20%.

Recent advances in numerical modeling for mass concrete have increasingly emphasized accuracy improvement through calibration with field measurements. Aniskin et al. [171] reported peak-temperature errors below 5% after inverse fitting of measured temperature curves, while Klemczak and Smolana [172] achieved temperature prediction deviations of 3 °C in critical regions using a correction factor in the three-step framework. In the study by Al-Hasani et al. [173], coupling FEM with hydration–temperature kinetics and calibrating the model against in-situ monitoring reduced discrepancies in temperature evolution to approximately 5–8%, with the predicted internal–surface temperature difference deviating by only 2–3 °C. These findings indicate that simulation–monitoring integration significantly enhances predictive reliability and provides a more robust foundation for optimizing temperature-control measures and assessing early-age cracking risks in engineering practice.

Overall, the application of numerical simulation in mass concrete has evolved from temperature prediction to integrated design and real time control. The continuous refinement of FEM-based modeling, optimization algorithms, and performance-based criteria has greatly improved the accuracy and practicality of temperature control strategies. Coupled with field monitoring, these advances have established a closed loop system for intelligent decision making in crack prevention and thermal management.

6. Problems and Future Research Directions

In summary, this review not only synthesizes the mechanisms and influencing factors of temperature-induced cracking in mass concrete but also provides a more integrated and forward-looking perspective than existing studies. A key innovation of this work is the unified framework that connects material design, construction technologies, PCMs, intelligent monitoring, and numerical simulation—areas that have traditionally been treated separately. This integration allows previously overlooked gaps to be clearly identified, including weak macro–meso coupling, the lack of quantitative material–construction coordination, limited engineering validation of PCMs, and insufficient feedback integration in monitoring systems. Based on this framework, the review proposes focused research priorities that can guide the next stage of development.

- (1)

- Development of next-generation low-heat and smart cementitious materials, supported by mechanistic models that couple hydration kinetics, heat transfer, and moisture migration, is essential for achieving performance-based mix optimization.

- (2)

- Advancement of PCM technologies—especially with respect to interfacial stability, encapsulation durability, and long-term compatibility with cementitious matrices—will be critical for transitioning PCMs from laboratory-scale feasibility to reliable engineering application.

- (3)

- Intelligent, closed-loop monitoring and control systems, enabled by multi-source sensing fusion, high-resolution field data, and AI-driven prediction models, hold the potential to achieve real-time regulation of temperature and stress evolution in mass concrete.