Abstract

The aim of this study is to analyze how public and private museums adopt digital innovations and to evaluate their contribution to sustainability strategies. The study explores the reasons for implementing digital innovation in museums, how digital innovation contributes to museums’ sustainability, and how museums’ governance model (state-funded or private) influences their capacity for digital innovation and sustainability. The analysis uses a multiple-case study in Lithuania, focusing on the following three museums in Vilnius: the state-funded Lithuanian National Museum, the privately managed MO Museum, and the Lithuanian Art Centre TARTLE. Empirical insights come from semi-structured interviews with museum representatives. Data are collected through online interaction and included in the study dataset. The findings show a clear tendency among museums to adopt digital innovations both to make the visitor experience more interactive and immersive, and to enhance internal management. The results suggest that the adoption of such innovations depends less on the museum’s form (public or private) and more on its size and related financial capacities. Large museums—whether public or private—have more financial capacity to implement digital innovations than smaller ones. Still, the results show that the lack of funds for technological innovations does not prevent museums from achieving sustainability. This research contributes to the field of sustainability by reviewing the scientific literature on the aspects of sustainability (economic, social, environmental, cultural, communicative) in museums’ digital innovation, and by offering exploratory insights from the Lithuanian context into the strategies that museums use to implement digital innovation and promote sustainable development.

1. Introduction

General remarks, problems, and sustainability issues. Museums are an important sector of the creative industries. They lead in economic growth, job creation, and national product export in many countries. Art products also contribute to cultural identity and strengthen social capital. Creative industries, especially museums, play a central role in sustainable development. They promote innovative solutions and support sustainability [1,2]. However, there is also a controversy. First, social capital does not always ensure creative capital and vice versa [3,4], and it does not necessarily ensure economic prosperity [5]. Second, creative activity, generally, and creative industries, specifically, do not necessarily contribute to the sustainable development [6]. Third, preserving cultural heritage does not necessarily presuppose digital innovations to contribute to sustainable development [7,8]. Finally, sustainable development is an ambiguous concept, especially when applied to the cultural sector, which can ignore economic aspects [9,10,11].

Sustainability in the museum sector is discussed in different ways. Table 1 presents aspects of sustainability in museums influenced by digital innovations.

Table 1.

Aspects of sustainability in museums’ digital innovations (prepared by the authors).

Table 1 presents five aspects of sustainability related to museums’ digital innovations: economic, social, environmental, cultural, and communicative. The theoretical model is based on the synthesis of all the mentioned aspects.

Scholars analyze these aspects, but most of them focus on a single aspect while ignoring the others. For example, Agostino [12] presents an economic approach focused on the sustainability of museums affected by digital technologies.

The social approach is presented by several scholars. Wang et al. [13] focus on the sustainable exhibition mechanism of cultural relics. Markopoulos et al. [14] see museums’ sustainability in terms of learning and entertainment enabled by digital technologies. For Fu et al. [15], sustainability lies in successful heritage preservation ensured by AI-enhanced systems. Wang and Zhou [17] interpret sustainable development as overcoming negative societal transformations or intergenerational transmission gaps.

The environmental approach covers several aspects. Ozdemir and Zonah [16] analyze how digital technologies help to reduce carbon footprints and support cultural preservation. Ai et al. [18] examine sustainability in the digital transformation of regional museums. Borda and Bowen [19] study sustainable aspects of smart digital culture services in museums. Tzouganatou [20] focuses on sustainability of digital ecosystems across galleries, museums, archives, and libraries.

The cultural approach covers attention to cultural content. For example, Arrigoni et al. [21] examine how museums’ cultural content supports the sustainability of cultural organizations amid digital transformation. Kasemsarn and Nickpour [22] see the sustainability of heritage tourism in the close interaction between storytelling, cultural tourism, and social media. According to Cappa et al. [23], digital technologies contribute to the sustainability of cultural organizations by providing visitor feedback. Hou and Riccò [24] relate sustainability to a better understanding of cultural artefacts in museums and the interconnection between visitors’ visual, auditory, and tactile senses. Wang and Zhou [13] define sustainable development as overcoming challenges such as the loss of cultural memory. Sandriester et al. [25] speak of both the cultural heritage sector, which is sustainable thanks to digitalisation, and sustainable regional development, to which the activities of museums contribute. In addition, a balance between culture conservation and visitor engagement also promotes more sustainable tourism.

The communicative approach means both sustainable communication and the impact of communication on sustainability. Pagán et al. [26] speak of sustainable development inseparable from the promotion of creative industries. According to Tsoukala et al. [27], sustainability in the integration of digital media into cultural institutions is ensured by sufficient resources, strategic planning, and a user-centred approach. Liu and Chen [8] stress sustainable cultural communication of museums in the digital age. Scholars [28] investigate aspects of sustainability in digital mediation systems and the sustainable dissemination and preservation of cultural heritage [29].

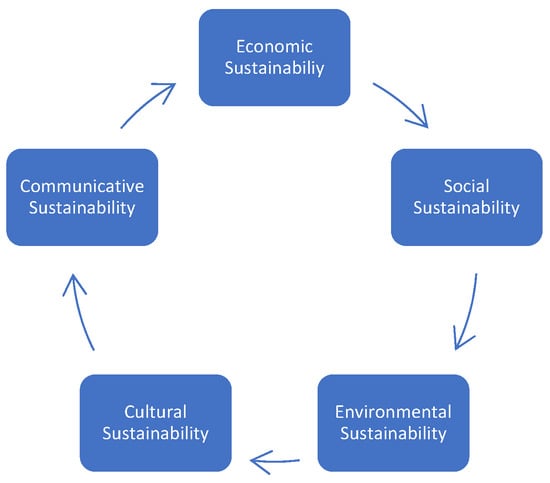

In sum, while scholars tend to focus separately on different aspects of sustainability, they often overlook others. Figure 1 illustrates the interconnections between economic, social, environmental, cultural, and communicative sustainability in museums under the influence of digital innovations.

Figure 1.

Interconnections between different aspects of museums’ sustainability under the influence of digital innovations (prepared by the authors).

This study is about digital innovations in museums and their role in fostering sustainable cultural development.

The research goal is to analyze how public and private museums adopt digital innovations and to evaluate their contribution to sustainability strategies.

General and specific research questions. The general research questions are: How does digital innovation contribute to a museum’s sustainability? How does the museum’s governance model (state-funded or private) influence its capacity for digital innovation and sustainability? The specific research question is: How do institutional structures influence museums’ ability to integrate digital innovations that support long-term sustainability goals?

The current state of the research field/literature review. Scholars [19] discuss creative cities’ digital services and tools within the museum sector. Agostino [12] analyzes how digital technologies can contribute to new revenue models for the sustainability of museums. Ai et al. [18] focus on digital innovations in regional museums and their sustainable issues. Del Villar et al. [7] investigate the innovative aspects of museums as a crucial social and economic element of creative industries and show the limits of new technologies within this sector. Tsoukala et al. [27] explore the impact of digital innovations on cultural institutions. Wang et al. [13] analyze digital content in museum management, focusing on protecting cultural heritage and promoting social education. Lian and Xie [29] investigate the application of digital technologies to cultural heritage from a communication perspective. Sousa and Providência [28] promote virtualization, observation distance, and interactivity within the digital mediation system to ensure sustainability, inclusivity, and accessibility. Arrigoni et al. [21] analyze the role of cultural content in shaping technological development. Markopoulos et al. [14] present the use of avatar technology in the museum sector to help it survive during the financial crisis and pandemic restrictions. Fu et al. [15] analyze the AI-driven innovation in the intangible cultural heritage. Kasemsarn and Nickpour [22] develop a digital storytelling approach in social media. Liu and Chen [8] promote a cross-cultural cooperation that covers advanced technologies, resource systems, engagement mechanisms, and institutional frameworks. Pagán et al. [26] deal with a museum’s cultural heritage in the context of creative industries and design innovation. Wang and Zhou [17] show that generative AI can promote the dissemination of innovation, digital transformation, and, ultimately, the sustainable development of intangible cultural heritage. Cappa et al. [23] promote the use of digital technologies to collect visitors’ ideas, improve exhibitions, and ultimately create a more satisfying museum experience. Hou and Riccò [24] review multisensory experiences based on digital technology in museums. Sandriester et al. [25] focus their attention on small museums’ digitalisation and its impact on sustainable regional development. On the contrary, Ozdemir and Zonah [16] focus on leading European museums and the applied digital technologies within them to preserve heritage, increase visitor engagement, and contribute to sustainable tourism. Tzouganatou [20] develops the issue of fairness and social inclusion through AI technologies in museums, galleries, archives, and libraries. Most scholars (Borda and Bowen [19], Agostino [12], Del Villar et al. [7], Tsoukala et al. [27], Sousa and Providência [28], Arrigoni et al. [21], Markopoulos et al. [14], Kasemsarn and Nickpour [22], Pagán et al. [26], Cappa et al. [23], Hou and Riccò [24], Sandriester et al. [25], Ozdemir and Zonah [16], Tzouganatou [20]) analyze cases in Europe, while some of them (Ai et al. [18], Wang et al. [13], Xie [29], Fu et al. [15], Liu and Chen [8], Wang and Zhou [17]) investigate museums in Asia. However, the Web of Science does not show any research of digital innovations in museums of Central and Eastern Europe.

Controversial and diverging hypotheses. The general hypothesis is as follows: Digital innovations contribute to economic, communicative, social, cultural, and environmental sustainability. The specific hypothesis is as follows: Private museums are oriented toward economical and communicative sustainability, while state museums are oriented toward social, cultural and environmental sustainability.

New distribution. Although studies examine digital innovations in museums to promote sustainable cultural development, there is a gap in analyzing the interconnections between these innovations and museums’ structures and governance models (state-funded or private). Additionally, the paper examines digital innovations in museums, offering exploratory insights derived from the Lithuanian context, a setting that has been largely underrepresented in recent research.

Structure. In Section 2, applied methods, including research design, selected cases, and data collection, are presented. In Section 3 of this research, the following aspects are analyzed: digital innovation in the last five years, including innovations for the visitor experience and innovations for museum management, objectives for the adoption of innovations, digital innovations as a factor of economic, communicative, social, cultural and environmental sustainability, museums’ legal status, challenges in adopting digital innovations, and digital innovation in museums’ long-term sustainability strategy.

2. Methods

2.1. Research Design

This research is based on a comparative (multiple) case study of three museums in Lithuania: one public (the National Museum of Lithuania) and two private (Mo Museum and Lithuanian Art Centre TARTLE). The case study, as a research method, has been described by Creswell [30] as a “qualitative approach in which the investigator explores a bounded system (a case) or multiple bounded systems (cases) over time, through detailed, in-depth data collection involving multiple sources of information (e.g., observations, interviews, audio-visual material, and documents and reports), and reports a case description and case-based themes” ([30], p. 97). In other words, case studies focus on a single or a limited number of cases, chosen by the researcher(s) because they are considered particularly significant and fully representative of the phenomenon under investigation. The three museums in question were selected based on the researchers’ access to them and on the museums’ own willingness to participate in this study.

Regarding this research, a specific type of case study, the comparative (multiple) case study [31] was employed, as the aim was to collect and analyze data from paradigmatic examples of public and private museums in Lithuania. Conducting a comparative analysis of different and holistic cases is useful in order to “strengthen the precision, the validity, and the stability of the findings” [32,33].

Furthermore, the analysis of the three selected cases is important not only in order to investigate how the integration of digital innovation in museums influences their sustainability (economic, communicative, social, cultural, environmental), but also to understand how and if the institution’s form (public or private) influences a museum’s capability to adopt digital innovation seeking sustainability.

The sources of information used for this comparative analysis are of two types: interviews with experts (one expert from each museum) and content analysis of the museums’ websites.

2.2. General Notes About the Selected Cases

Mo Museum. The Mo Museum (hereinafter, MO) is arguably the most significant private museum in Lithuania. It was founded in 2018 by philanthropists Danguolė Butkienė and Viktoras Butkus, and it houses approximately 6000 modern and contemporary Lithuanian artworks spanning the 1950s to the present day.

National Museum of Lithuania. The National Museum of Lithuania (hereinafter, NML) is one of the oldest state-sponsored museums of Lithuania, founded in 1952. With a collection of approximately 1.5 million artefacts preserved in various structures, mostly in the city of Vilnius, it is the largest historical museum in Lithuania.

Lithuanian Art Centre TARTLE. Founded in 2018 by the art collector Rolandas Valiūnas and the Lithuanian Art Foundation, the Lithuanian Art Centre TARTLE (hereinafter, TARTLE) is located in the district of Užupis (Vilnius) and houses Lithuanian artistic and historical artefacts from pagan times to contemporary art.

2.3. Data Collection and Participants

After selecting the cases to be analyzed to examine the adoption of digital innovations by museums and their potential impact on various aspects of sustainability, the museums were contacted via their general email addresses. The three museums immediately welcomed the proposal to collaborate on this research and designated a representative from each museum to answer the researchers’ questions and provide any information useful to the study. Subsequently, the designated representatives of the museums were contacted. Representatives of two museums (NML and MO) preferred to answer the questions in writing, so the information was collected via email. The representative of the third museum (TARTLE) chose to respond orally, and a video interview was therefore conducted via Microsoft Teams. Both the email exchange and the interview were transcribed and translated from Lithuanian into English and included in the dataset for this study. Although the representatives of the museums are presented anonymously in this article, it should be emphasized that they were informed of the purpose (research aimed at producing a scientific publication) and the subject (digital innovations and sustainability in the context of museums) of the interaction, and freely agreed to participate in this research by signing a consent form. An overview of the respondents and the dates of their interactions is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Representatives of museums (prepared by the authors).

3. Results

3.1. Digital Innovation in the Last Five Years

Museum representatives were asked to provide information on the digital innovations that have been integrated into their museums over the last five years. In general, the digital innovations adopted by the museums can be grouped into two macro-areas: (1) innovations for the visitor experience and (2) innovations for the management of the museum itself.

3.1.1. Innovations for the Visitor Experience

The MO has, first of all, renewed its website by adopting a more user-friendly UX solution and introducing a new section—the blog—which offers a variety of virtual content for anyone interested in the artistic world. The collection has also been digitized, making it accessible online with expanded information on the featured artists, interviews, and other related content. The MO’s e-guide, available online, has likewise been renewed; it presents the museum’s current exhibitions, its history, and the so-called “talking sculptures” of Vilnius. In addition to Lithuanian and English versions, the digital guide is also available in Lithuanian Sign Language. The visitor’s virtual experience has been further enriched with virtual tours, video-guided visits, interactive quizzes, and an online shop. The museum has also organized the Virtual Olympics of Modern Art—the MOdyssey—and offers other virtual experiences for visitors (for example, Instagram filters featuring works from the MO collection, etc.).

The NML has focused on the 3D digitization of artefacts belonging to its collections and the creation of digital exhibitions and expositions accessible in 360°, available on its website within a section called the “virtual museum” (https://lnm.lt/en/virtual-museum/, accessed on 18 September 2025), which also provides e-guides, both in Lithuanian and English, as well as original podcasts. Moreover, the NML has also developed a digital shop for the sale of publications, souvenirs and gift items inspired by the artefacts preserved in its collections.

While the first two museums have progressively integrated digital innovations over the past five years, the account provided by TARTLE presents a somewhat different picture. In the last five years, TARTLE has not adopted new digital technologies beyond those already in place at the time of its founding: projectors, touchscreen displays, tablets, and QR codes placed next to artefact descriptions, allowing visitors to access additional content on their phones. The representative underscores that this reflects the reality of a small private museum, which lacks the financial resources available to larger institutions (whether public or private), and where “any changes […] cost a great deal of money”. Yet, this decision—though driven by financial and spatial constraints—also results in a sustainability-oriented approach. The representative explains that even the few technologies in use are employed only when necessary: “The projector is hidden in the ceiling. This means that when needed, it comes down using a lift, and then we can display content either on a special screen or directly on an empty wall. If we do not need it and are not using it, it hides back into the ceiling”. The same applies to the screens which, if not required for a given exhibition, “close like a cabinet door and become a white cupboard”. During the interview, the representative also discussed artificial intelligence (hereinafter, AI), noting that numerous forums in Lithuania are currently addressing how AI might be integrated into museums. In her view, however, AI-generated text for museum activities raises concerns: “We are being very cautious for now, because you have to verify what it writes—AI invents a great deal of things that never existed, so you have to check everything very thoroughly. You cannot ask it to write texts if you do not know the context, because it will generate details you never imagined”.

3.1.2. Innovations for Museum Management

The MO has implemented an automated registration system for guided tours and other educational activities, including reminders for booked activities and payments, and the feedback collection. Solutions for automating the management of MO’s annual memberships are also being introduced, including automated emails, reminders, and other tools.

Regarding the NML, in 2019, the Lithuanian Integral Museum Information System was introduced to catalogue and disseminate digitized museum artefacts. Subsequently, in 2023, the General Document Management Information System was implemented to manage the museum’s internal documentation. In the same year, the Lithuanian Integral Museum Information System was fully adopted.

TARTLE, by contrast, has not adopted any particular innovations related to museum management.

3.2. Objectives for the Adoption of Innovations

Several factors have led the museums to adopt the digital innovations described above. Regarding the MO, the primary objectives were to enhance visitor engagement by creating interactive and virtual experiences that provide enjoyment, particularly for younger audiences, individuals with disabilities, or those living at a distance. Additionally, the museum’s representative mentioned the objective of preserving the collection and the need to make informed decisions based on the analysis of visitor behaviour data.

The NML, in addition to its goal of reaching a wider audience, also highlighted improvements in operational process quality (digitization of museum artefacts, management and administration of accounting documentation), as well as increased transparency.

As for TARTLE, the representative emphasizes that adopting digital innovations aligns with the broader direction in which museums are currently moving. As she notes: “For a long time, the museum was understood as a space perhaps intended for seniors, where a few portraits hang on the wall. But now you realize that audiences need to be ‘entertained’, and that you need something interactive in order to attract people”. Although sustainability was not among the primary reasons for adopting these innovations, further reflection (developed below) led the representatives to acknowledge that these innovations have produced outcomes, particularly in sustainability across its various dimensions (economic and communicative, social and cultural, and ecological).

3.3. Digital Innovations as a Factor of Sustainability

Museums’ representatives were asked to illustrate how the integration of digital technologies influences their museums’ sustainability in its various aspects (economic and communicative, social and cultural, environmental).

3.3.1. Economic and Communicative Sustainability

The representative of MO stated that the launch of the online shop has constituted a supplementary and/or new source of income. In addition, the introduction of digital innovations related to data collection and visitor behaviour monitoring contributes to the optimization of activities and more targeted marketing. The representative of NML further argued that the creation of digital products and services reduced the need to physically accommodate every visitor, thereby lowering costs associated with travel, transportation, and ticketing. Moreover, the development of virtual products does not require the use of material resources, such as the production of exhibition materials or the adaptation of spaces (e.g., display cases, panels). Even in terms of economic sustainability, TARTLE’s position differs from that of the other two museums. In this case, economic sustainability is not achieved through strategies of digital innovation but through strategies of exchange and material reuse. The representative first acknowledges that museums, as organizations, can sometimes be “unsustainable”. The central issue concerns the materials left over when an exhibition closes. If a museum is large and has storage facilities, it can keep these materials for future use; however, as the representative points out, there is a strong likelihood that the remaining materials will simply be discarded. Because TARTLE lacks storage space and seek to reduce material waste, it has, from the very beginning, adopted strategies of reuse and exchange to save resources and achieve economic sustainability. Regarding reuse, the representative cites paintings and graphic works as examples. To avoid damaging the walls and then having to repair them, TARTLE has “installed hanging systems—rails—throughout the museum, and all paintings hang from these rails. This means I do not touch the walls: I hang a painting, remove it, hang another one—no nails, no holes, no renovations”. In addition, the museum decided to paint the walls in a soft grey so they could suit different types of exhibitions. As for graphic works, a single type of frame is used, which can be reused to display other works in the future. TARTLE’s exchange strategies will be discussed in the section on communicative sustainability.

With regard to communicative sustainability, as mentioned in the introduction, it is necessary to consider both the sustainable communication of the museum’s activities, and the communication of the museum’s own sustainability in its various dimensions. Regarding the first aspect, sustainable communication cannot disregard the museum’s presence on today’s main tools of creative communication—social media. In addition to comprehensive websites with online shops or digital content, museums maintain a presence across several social media platforms: they each have profiles on major platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and LinkedIn, and adapt their creative communication strategies to each platform’s affordances. Moreover, since October 2022, the NML has also been using TikTok. As for the communication of the museums’ sustainability, it permeates the communication strategies of the three institutions, but it is worth noting that the MO has a dedicated section on its website addressing sustainability (https://mo.lt/en/sustainability/, accessed on 25 August 2025).

Moreover, in 2021, as part of the project “Museums Facing Extinctions”, TARTLE and the Kazys Varnelis House-Museum (part of the NML) created a Facebook group called “Muziejai prieš klimato kaitą” (Museums Against Climate Change). Within this group, Lithuanian museums share their sustainability initiatives and make available leftover materials from various exhibitions that might be useful to other museums. This approach to sustainability brings together economic, communicative, and social aspects. Those who participate in the exchange of materials through the Facebook group become part of a community—a group that discusses and advances sustainability strategies, enabling them to save on the purchase of new materials, communicate their initiatives, and build a sense of solidarity. It is a form of sustainability that probably stems from greater awareness of the issue but also from scarcity, as the TARTLE respondent notes: “these solutions often come from a lack of resources. When you have no money, you start thinking a few steps ahead. You become very creative”.

3.3.2. Social and Cultural Sustainability

The representative of MO argues that, thanks to digital innovations, the MO has become “an open, inclusive museum accessible to different social groups”. She emphasizes increased accessibility through virtual solutions that enable to reach people regardless of location, age, or physical ability. Digital innovations have also made the NML more accessible to a broader audience, including international visitors, regardless of their geographical location. Likewise, the museum’s services have been adapted for people with disabilities who previously were unable to benefit from, or even access, certain sections of the museum’s collections.

Regarding cultural sustainability—understood as an enhanced understanding of cultural artefacts resulting from greater interaction between visitors and the exhibited works—this aspect is particularly developed at one of the NML’s facilities, the House of Histories, whose exhibitions are organized around interactive, multisensory pathways. This approach is also reflected in the philosophy of the MO Museum, one of whose latest exhibitions—2025’s GamePlay. Playing for Impact, the first video game exhibition in Lithuania—invites visitors to play a series of video games created by various artists and creators that address socially relevant themes. While acknowledging the importance of immersive experiences, the TARTLE representative believes it is necessary to strike a balance between interactivity and immersivity on the one hand, and the very nature of the museum as a place of cultural heritage on the other, “so that heritage and history are presented and interpreted properly, while digital innovation provides an additional treat”.

3.3.3. Environmental Sustainability

Museums’ representatives agree that virtual solutions reduce the need for physical travel (with a consequent decrease in CO2 emissions); moreover, the digitization of documentation enables the use of less paper, thereby reducing printing and transportation costs. Additionally, the MO has implemented a system for energy optimization and CO2 footprint calculation, thereby contributing to the institution’s energy savings and reducing emissions. Similarly, TARTLE is equipped with “smart home” solutions. All lighting fixtures are adjustable to illuminate artworks as needed. The fixtures are mounted on rails and held in place by magnets, allowing them to be repositioned as required. Moreover, the light intensity can be regulated via a smart-home application on a tablet.

3.4. Museums’ Legal Status

All representatives emphasize that the institution’s legal status (state-funded or private) significantly impacts the implementation of digital innovations and achieving sustainability.

The NML, as a state museum, is regulated by legislation and internal procedures; therefore, every decision must be made in accordance with the established requirements. On the one hand, this ensures transparency and accountability, but on the other, it slows down processes and limits the museum’s ability to respond promptly to technological changes or emerging needs. Financial constraints are equally relevant: the main part of the budget comprises state allocations, which, while ensuring operational stability, are limited and often insufficient for implementing innovative ideas. To carry out broader digitization and sustainability projects, the state museum must necessarily resort to additional funding sources, such as various support funds and programmes, or initiate new forms of partnership.

According to the MO and TARTLE representatives, the private museum enjoys greater flexibility and freedom of action, as decisions are made more quickly and effectively, without being bound by an extensive bureaucratic apparatus, and it can operate with a “start-up” logic. Conversely, the private museum must secure its own financial stability; as a result, “every digital innovation must pay off” (MO). Moreover, private museums “have very limited financial resources and must manage with what you have. In contrast, when you are a public institution and have access to substantial funds and a long-standing tradition—often with guaranteed financing for exhibitions—you may not need to consider how to make ends meet” (TARTLE).

3.5. Challenges in Adopting Digital Innovations

The process of integrating digital innovations within a museum—whether state-funded or privately funded—entails several challenges.

For the MO and TARTLE, the main issues have been primarily financial. As stated by the MO representative, when dealing with digital solutions: (a) substantial initial investments are often required; (b) project continuity is not guaranteed; (c) funding frequently occurs in phases; (d) innovations may be introduced, but financial support for their technical maintenance is not always ensured; (e) the profitability of such investments is not always easily predictable. Furthermore, integrating these types of innovations also requires enhancing the team’s digital competencies.

For the NML, the major challenge primarily concerns the sustainability of the innovative solutions implemented, as their introduction must comply with public procurement law. Consequently, there are cases in which tenders are won by companies offering the lowest price. The representative notes that, in such situations, technological solutions do not always stand out for their durability: equipment wears out or breaks down more quickly, making the long-term use of innovations more difficult.

3.6. Digital Innovation in the Long-Term Sustainability Strategy

All the museums regard digital innovations and sustainability as integral components of their long-term sustainability strategy.

In the NML’s 2025–2028 operational strategy, several priority directions have been identified: (a) the exploration of possibilities for applying artificial intelligence tools to the digitization of museum assets; (b) the updating of pricing and accounting systems; (c) the creation and implementation of an efficient management system for existing electronic resources; and (d) the optimization of the management of the museum’s heritage and resources. According to the representative, “these measures will make it possible not only to ensure greater transparency and efficiency of activities, but also to create the conditions for long-term access to cultural heritage and for its sustainable use”.

In MO’s long-term strategy, the museum plans to continue expanding accessibility to diverse audiences, strengthen its bond with visitors through inclusive and interactive experiences, extend its social mission by further consolidating its active role in education, and to enhance its competitiveness and visibility within a broader context. As the representative affirmed, “the museum’s conception and orientation with regard to sustainability encompasses not only the environment, but also the human dimension”—an idea encapsulated in the slogan of a 2021 campaign: “the climate of the inner world is equally important. Through art we contribute to shaping and nurturing a sustainable personality”.

For TARTLE, the future adoption of new digital innovations will depend on its financial capacities; however, as a small museum, it will continue to rely on the same successful sustainability strategies based on the reuse and exchange of materials and practices with other museums.

In summary, the findings reveal a clear tendency among museums to adopt digital innovations both to make the visitor experience more interactive and immersive, and to enhance internal management processes. Although sustainability was not among the primary reasons for adopting these innovations, the results show that digital innovations strongly contribute to museums’ sustainability across all its aspects, consistent with the general hypothesis of this research.

At the same time, the results seem to suggest that the adoption of such innovations depends less on the museum’s institutional form (public or private) and more on its size (small or large). Large museums—whether public or private—possess far greater financial capacity to implement digital innovations than smaller institutions. Nevertheless, the lack of funds for technological innovations does not prevent achieving sustainability, as demonstrated by TARTLE.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Hypotheses. The general hypothesis has been fully supported, as digital innovations strongly contribute to museums’ sustainability in all its aspects (economic, communicative, social, cultural and environmental). However, the specific hypothesis has not been approved.

Indeed, the results show that the various forms of sustainability achieved by a museum—with or without the contribution of digital innovations—do not stem from its being public or private, but rather from the management’s greater or lesser sensitivity to these issues, or even from economic constraints. All three museums examined in this research address all the aforementioned aspects of sustainability, as they are interconnected. For example, when communication takes place through social media, as in the case of the Facebook group that facilitates the exchange of materials among Lithuanian museums (communicative sustainability), networking occurs and a community is formed (social sustainability); likewise, when financial shortages require saving strategies (economic sustainability), the practices of recycling and reusing materials are reinforced (ecological sustainability). It is equally true that, unlike a public museum—which benefits from the security of receiving a substantial and stable financial contribution—the private museum (whether small or large) operates according to a business logic and must therefore “balance the books” (economic sustainability). Consequently, the adoption of technological innovations becomes an investment that largely depends on the institution’s financial capacity and must “pay off.” Nevertheless, the findings show that the lack of funds for technological innovations does not prevent achieving sustainability, which has now become an integral part of everyday museums (both public and private) practices.

Placement of research among other research. This research contributes to the scientific debate on the integration of technological innovations into museums and on the relationship between this process and achieving environmental, cultural, communicative, social, and economic sustainability objectives. To this end, the study situates itself within a body of scholarly literature that addresses the topic of digital innovations in knowledge management systems [33], the Metaverse, augmented reality, and AI as tools for immersive experiences in the fields of tourism [34] and museums [35,36], the online presence of museums [37], and the role of digital innovation in fostering the organizational performance within the cultural sector [38], as well as the increasing application of digital interactive installation in museums [39]. Moreover, while this research contributes to the theme of the sustainable development of museums [40,41,42], it advances a different perspective by adding a fundamental dimension—namely, the legal status of the museum (state-funded or private) and how this influences the institution’s ability to adopt digital innovations and, consequently, to pursue sustainability objectives.

Limitations of the study. This research inevitably presents several limitations. First, as it is a case study, albeit comparative, it necessarily entails a purposive selection of cases. Furthermore, since the study is based on expert interviews, it also depends on the willingness and availability of the institutions and their representatives to participate and be interviewed. A different selection of museums would likely have produced different results. In addition, the choice of two of the three respondents to opt for a written interaction over oral interviews, while ensuring the collection of not only general information but also of concrete data and experiences, inevitably results in the loss of some of the spontaneity and depth of an interview. In any case, to ensure the validity of the responses, follow-up emails were sent. The follow-up process consisted of clarifying questions from respondents and requests for additional details from the researcher. For example, in one case, a respondent sought clarification about the definitions of cultural sustainability and communicative sustainability in order to answer more accurately. In other cases, the researcher requested further information, such as details regarding the integration of Lithuanian museums into the national system for digitizing and cataloguing museum assets.

Further research. Future research could involve other museums in Vilnius to measure, using quantitative methods, the adoption of technological innovations and their impact on sustainability goals. Furthermore, a broader perspective could be adopted by conducting research that selects individual museums (both state-funded and private) from other European capitals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K.; Methodology, S.S.; Formal analysis, S.S.; Investigation, T.K.; Resources, S.S.; Data curation, S.S.; Writing—original draft, S.S.; Writing—review and editing, T.K.; Supervision, T.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was performed by the ethical standards as laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Given the nature of the research, written approval from an ethics review board was not requested (Article 25). Participants’ identities were anonymized, and no personally identifying data were collected or disclosed. All data was used exclusively for academic analysis (Article 24). The confidentiality and anonymity of all respondents have been maintained and will continue to be maintained, in full accordance with the prevailing ethical regulations of Vilnius Gediminas Technical University (VILNIUS TECH). No personally identifiable information has been collected.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| MO | Mo Museum |

| NML | National Museum of Lithuania |

| TARTLE | Lithuanian Art Centre TARTLE |

References

- Soini, K.; Dessein, J. Culture-sustainability relation: Towards a conceptual framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocchi, D. The cultural dimension of sustainability. In Sustainability: A New Frontier for the Arts and Culture; Kagan, S., Kirchberg, V., Eds.; Verlag für Akademische Schriften: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2008; pp. 26–58. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A.S.C. Its origin and applications in modern sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R. The Rise of the Creative Class; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Woolcock, M.; Narayan, D. Social capital: Implications for development theory, research, and policy. World Bank Res. Obs. 2000, 15, 225–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kačerauskas, T. Creative Society; Peter Lang: Berlin, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Del Villar, R.C.D.; Cortina, J.D.; Palomino, O.M.; Rojas, R.R. Pursuing innovation: Exploring the relationship between museum size and creative possibilities. Int. J. Incl. Mus. 2025, 18, 125–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, M.W. Iconological reconstruction and complementarity in Chinese and Korean museums in the digital age: A comparative study of the National Museum of Korea and the Palace Museum. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The field of cultural production, or: The economic world reversed. In The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature; Johnson, R., Ed.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 29–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ardery, J.S. ‘Loser wins’: Outsider art and the salvaging of disinterestedness. Poetics 1997, 24, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalora, S. Introduction. In Over-Loaded with Wisdom: A Selection of Contemporary American Folk Art; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 13–53. [Google Scholar]

- Agostino, D. COVID-19 and the economic sustainability of Italian museums: Can digital technologies enhance new revenue models? Mus. Manag. Curatorsh. 2024, 39, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Chen, C.L.; Deng, Y.Y. Museum-authorization of digital rights: A sustainable and traceable cultural relics exhibition mechanism. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markopoulos, E.; Ye, C.; Markopoulos, P.; Luimula, M. Digital museum transformation strategy against the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. In Advances in Creativity, Innovation, Entrepreneurship and Communication of Design, Proceedings of the AHFE Virtual Conferences on Creativity, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, and Human Factors in Communication of Design, Virtual, 25–29 July 2021; Markopoulos, E., Goonetilleke, R.S., Ho, A.G., Luximon, Y., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.A.; Shi, K.; Xi, L. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in the preservation and innovation of intangible cultural heritage: Ethical considerations and design frameworks. Digit. Scholarsh. Humanit. 2025, 40, 487–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, G.; Zonah, S. Revolutionising heritage interpretation with smart technologies: A blueprint for sustainable tourism. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.D.; Zhou, Y.X. Artificial intelligence-driven interactive experience for intangible cultural heritage: Sustainable innovation of blue clamp-resist dyeing. Sustainability 2025, 17, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Y.T.; Zhu, X.R.; Nohara, K. Sustainable digital innovation for regional museums through cost-effective digital reconstruction and exhibition co-design: A case study of the Ryushi Memorial Museum. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borda, A.; Bowen, J.P. Smart cities and digital culture: Models of innovation. In Museums and Digital Culture: New Perspectives and Research; Giannini, T., Bowen, J.P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 523–549. [Google Scholar]

- Tzouganatou, A. Openness and privacy in born-digital archives: Reflecting the role of AI development. AI Soc. 2022, 37, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigoni, G.; Schofield, T.; Pisanty, D.T. Framing collaborative processes of digital transformation in cultural organisations: From literary archives to augmented reality. Mus. Manag. Curatorsh. 2020, 35, 424–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasemsarn, K.; Nickpour, F. Digital storytelling in cultural and heritage tourism: A review of social media integration and youth engagement frameworks. Heritage 2025, 8, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappa, F.; Rosso, F.; Capaldo, A. Visitor-sensing: Involving the crowd in cultural heritage organizations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, W.H.; Riccò, D. Accessible design for museums: A systematic review on multisensory experience based on digital technology. In Advances in Design and Digital Communication V, Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Design and Digital Communication, DIGICOM, Barcelos, Portugal, 7–9 November 2024; Martins, N., Brandăo, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 291–305. [Google Scholar]

- Sandriester, J.; Harfst, J.; Kern, C.; Zuanni, C. Digital transformation in the cultural heritage sector and its impacts on sustainable regional development in peripheral regions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagán, E.A.; Salvatella, M.d.M.G.; Pitarch, M.D.; Muñoz, A.L.; Toledo, M.d.M.M.; Ruiz, J.M.; Vitella, M.; Lo Cicero, G.; Rottensteiner, F.; Clermont, D.; et al. From silk to digital technologies: A gateway to new opportunities for creative industries, traditional crafts and designers. The SILKNOW Case. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoukala, S.; Kalliampakou, I.; Theodoropoulou, A.; Giannoukou, I. Digital engagement in cultural institutions: Enhancing visitor experience through innovative technologies. In Innovation and Creativity in Tourism, Business and Social Sciences, Proceedings of the 11th International Conference, IACuDiT, Naxos, Greece, 3–5 September 2024; Katsoni, V., Costa, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 1, pp. 375–412. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, F.; Providência, F. Critical digital: A taxonomy to classify digital integration in the museum domain. In Advances in Design and Digital Communication IV, Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Design and Digital Communication, DIGICOM, Barcelos, Portugal, 9–11 November 2023; Martins, N., Brandăo, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.T.; Xie, J.F. The evolution of digital cultural heritage research: Identifying key trends, hotspots, and challenges through bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B.; Tisdell, E.J. Qualitative Research. A Guide to Design and Implementation, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebooks, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Di Vaio, A.; Palladino, R.; Pezzi, A.; Kalisz, D.E. The role of digital innovation in knowledge management systems: A systematic literature review. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, S.; Sacchi, G. Travelling the Metaverse: Potential Benefits and Main Challenges for Tourism Sectors and Research Applications. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serravalle, F.; Ferraris, A.; Vrontis, D.; Thrassou, A.; Christofi, M. Augmented reality in the tourism industry: A multi-stakeholder analysis of museums. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 32, 100549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzanti, P.; Bertini, M. Reshaping Museum Experiences with AI: The ReInHerit Toolkit. Heritage 2025, 8, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostino, D.; Arnaboldi, M.; Lampis, A. Italian state museums during the COVID-19 crisis: From onsite closure to online openness. Mus. Manag. Curatorsh 2020, 35, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.; Kottasz, R.; Yuan, P.Y. The mediating role of digital innovation capability on the relationship between organisational agility and performance: The case of the UK arts and culture sector. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2465893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, M. Research on User Experience and Continuous Usage Mechanism of Digital Interactive Installations in Museums from the Perspective of Distributed Cognition. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loach, K.; Rowley, J.; Griffiths, J. Cultural sustainability as a strategy for the survival of museums and libraries. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2016, 23, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianou-Lambert, T.; Boukas, N.; Christodoulou-Yerali, M. Museums and cultural sustainability: Stakeholders, forces, and cultural policies. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2014, 20, 566–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, I.L.; Borza, A.; Buiga, A.; Ighian, D.; Toader, R. Achieving Cultural Sustainability in Museums: A Step Toward Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).