Abstract

Background: Overweight and obesity frequently occur as comorbid conditions in people with asthma, particularly among those with poor disease control or more severe clinical profiles. However, the extent to which exposure to grey spaces may influence the link between overweight/obesity and asthma remains insufficiently explored. Aim: To assess the association between overweight/obesity and asthma in an Italian general population sample and the influence of residential grey space on such relationship. Methods: A total of 2841 individuals (54.7% women; age range 8–97 years) residing in Pisa, Italy, were surveyed in 1991–1993 using a standardised questionnaire on health conditions and relevant risk factors. The proportion of grey space within a 1000 m buffer around each participant’s home was quantified using the CORINE Land Cover database. Multinomial logistic regression models were applied to assess the association between asthma status (1. asthma symptoms without doctor diagnosis, 2. diagnosis ± symptoms, 3. no diagnosis/symptoms − reference category) and overweight/obesity, adjusting for sex, age, educational level, smoking, physical activity and grey space exposure. Analyses were further stratified according to high vs. low grey space exposure (above vs. below 63%, corresponding to the second tertile). Mediation and interaction analyses were also performed. Results: The prevalence of asthma diagnosis ± symptoms, overweight and obesity was 18.7%, 35.8% and 12.8%, respectively. In the full sample, asthma symptoms without medical diagnosis were positively associated with overweight (Odds Ratio—OR 1.43; 95% Confidence Interval—CI 1.08–1.88), obesity (OR 1.99; 95% CI 1.38–2.88) and residential grey space (OR 1.06; 95% CI 1.01–1.13). Stratified models showed that, among participants with high exposure to grey areas, asthma symptoms were linked to both overweight (OR 2.03; 95% CI 1.29–3.19) and obesity (OR 2.57; 95% CI 1.36–4.86). In individuals with low grey space exposure, an association was observed only with obesity (OR 1.80; 95% CI 1.15–2.82). Mediation analysis did not reveal any weight-related effect modification. Measures of additive interaction indicated that 32% of asthma symptoms were attributable to the interaction between excess body weight and high grey space exposure. Conclusions: This study showed that overweight/obesity and grey space exposure are factors associated with asthma symptoms. These findings advocate for an early identification of overweight/obese-asthma symptom phenotype since it may help prevent the onset or worsening of asthma, particularly in urban environments. These insights highlight the need for integrated public health and urban planning strategies to promote more sustainable, health-supportive environments.

1. Introduction

Asthma is a common condition caused by chronic inflammation of the lower respiratory tract. This disease is characterised by symptoms such as wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness and cough [1]. Asthma is a global public health issue, with an estimated 260 million people worldwide suffering from this disease in 2024, and it is responsible for over 450,000 deaths each year worldwide [2]. In the last decades, the prevalence of asthma has doubled in Westernised countries and may have reached a plateau in recent years [3,4,5]. The causes of this alarming change are unclear, but cannot be attributed only to changes in diagnosis and patient awareness over time [5]. Since the East–West Germany comparison [6], many studies have shown an association between the rise in allergic diseases and modern Westernised lifestyle, which is characterised by increased urbanization, air pollution, time spent indoors, unhealthy dietary patterns and antibiotic usage [4,7]. Lifestyle-related factors, such as high body mass index (BMI), smoking, salty-snack eating and time spent on television watching, have been associated with increased asthma prevalence in the literature from Western countries [8,9,10].

As reported by the Global Burden of Diseases study (GBD) in 2021, obesity is a risk factor for asthma [11,12]. It is also considered a disease modifier for asthma in both adults and children, and it is associated with increased asthma severity [13]. A meta-analysis of prospective epidemiologic studies has quantified the relationship between categories of Body Mass Index (BMI) and incidence of asthma in adults and has concluded that the more overweight an individual is, the greater the likelihood of having or developing asthma [14]. Compared with normal weight people, asthma in obese individuals is associated with poorer asthma-related quality of life, greater health care utilization and a worst control partly due to reduced response to standard drug therapy [13,15,16]. Moreover, different studies have reported that weight loss leads to significant improvements in asthma control and lung function [13,17].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 90% of individuals worldwide, especially those in urban areas, inhale air contaminated with levels of pollutants above the WHO Guidelines, and it was estimated that approximately 7 million people die each year due to particles in polluted air [18,19]. More recently, the State of Global Air report has estimated 8.1 million deaths annually due to air pollution, which has become the 2nd leading cause of avoidable deaths [20]. Many studies have so far demonstrated a clear association between short-term exposure to outdoor air pollutants and different asthma outcomes, including asthma control [21], lung function [22], consumption of asthma medications [23], asthma exacerbations [24], hospitalizations [25] and deaths [26]. Particulate matter (PM) has the greatest impact on human health and is commonly used as a measure of air quality [27,28]. Evidence suggests that air pollution has a negative impact on asthma outcomes in both adult and paediatric populations, and 13% of the global incidence of asthma in children could be attributable to traffic-related air pollution, a complex urban mixture rich in PM [29].

Recently, data from the Coordination of the Information on the Environment (CORINE) Land Cover (CLC) [30,31] were used in epidemiological studies [32]. CLC is a European-wide standardised land cover map, managed by the European Environmental Agency (EEA), combining geospatial environmental information from national databases and satellite images [33] to provide data about specific land cover types such as urban/grey spaces, green spaces and proximity to agricultural areas or water bodies (blue space). In particular, the grey spaces, including several urban places such as industries, urban fabric and transport infrastructures, can be used as a proxy of urban environment exposure, where various pollutants abound.

Most previous research has separately analysed the role of extra weight and grey space in asthma risk assessment. Recent evidence suggests that PM may trigger inflammation in adipose tissue, oxidative stress injury and metabolic dysfunction, affecting weight status [34]. At the same time, obesity can worsen the adverse effects of air pollution on the human body, enhancing susceptibility to the PM-related harmful effects, and also enhancing the association of PM exposure with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension and cardiovascular disease [34]. Thus, the interaction between weight and grey space, as a proxy of air pollution exposure, is biologically plausible. Nevertheless, no studies have exhaustively explored the role of this interaction on asthma.

This study aims to assess the association between overweight/obesity and asthma in an Italian general population sample and the influence of residential grey space on such a relationship.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population and Design

A multistage stratified random sample of the general population living in Pisa, Italy, was investigated in three subsequent cross-sectional surveys [35]: first survey (PI1) (1985–1988); second survey (PI2) (1991–1993); third survey (PI3) (2009–2011). In this paper, data from the second survey (PI2), consisting of 2841 subjects, have been used. Data were collected through the use of a standardised interviewer-administered questionnaire developed by the National Research Council on the basis of the National Heart Blood and Lung Institute questionnaire [36]. At the time of the PI2 study, Italian law did not require Ethical Committee approval. The protocol was approved by an Internal Review Board. The study was carried out in accordance with the fundamental principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

2.2. Health Outcome

Subjects answered questions about lifetime asthma symptoms and asthma doctor diagnosis. The following asthma symptoms were considered: wheezes or whistles and attacks of shortness of breath with wheeze and whistle.

In order to detect possible effects at an early disease stage, the following mutually exclusive outcome variables were computed: 1. asthma symptoms without doctor diagnosis (“symptoms without diagnosis”), 2. asthma diagnosis with or without symptoms (“diagnosis ± symptoms”), 3. no asthma diagnosis nor asthma symptoms (“no diagnosis/symptoms” − reference category).

2.3. Exposure

BMI categories and grey space exposure were considered exposure variables.

BMI categories were computed as follow: 1. underweight and normal weight (BMI < 25 kg/m2), 2. overweight (25 ≤ BMI < 30 kg/m2), 3. obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2).

The percentage of grey spaces within a 1000 m buffer surrounding the geocoded home address was computed through the CLC. Grey space was analysed in two ways: (a) as a continuous variable, considering 10% increments; (b) as a categorical variable, stratifying the subjects in highly exposed to grey spaces (those with a surrounding residential grey space ≥ 63% (2nd tertile)) and lowly exposed to grey spaces (<63%)). Moreover, a combined variable considering both the weight and grey exposure was computed as follows: 1. underweight-normal weight and low grey exposure (reference category); 2. underweight-normal weight and high grey exposure; 3. overweight-obese and low grey exposure; 4. overweight-obese and high grey exposure.

2.4. Confounding Factors

Different potential confounders collected through questionnaire were considered: sex; age (1. ≤18 years, 2. >18 and ≤59 years, 3. >59 years); educational level (1. literate/elementary/middle high school (≤8 years of education), 2. college/high school (9–13 years of education), 3. graduate (>13 years of education)); smoking habits (1. non-smoker (subjects who had never smoked any kind of tobacco), 2. smoker (subjects who were smoking), 3. ex-smoker (subjects who had smoked in the past but were not smoking at the time of the survey)); active lifestyle in terms of daily time spent outdoors (1. ≥2 h, 2. <2 h) [37].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The characteristics of the study sample have been summarised with the use of frequency distribution (%). Bivariate analyses were carried out using a chi-square test to compare categorical variables and analysis of variance to compare continuous variables.

A multinomial logistic regression model was carried out to estimate the independent effects of overweight/obesity and grey space (10% increase) on asthma outcome, adjusting for the potential confounders described above.

In order to consider the possible effect modification by grey space exposure on the relationship between overweight/obesity and asthma outcomes (that is if there is a heterogeneous effect according to grey space exposure), the analyses were also carried out by stratifying the subjects into highly exposed and lowly exposed to grey spaces. The analyses were adjusted for the potential confounders. A Causal Mediation Analysis (CMA) was also carried out to determine whether overweight or obesity mediated, either partially or entirely, the association between grey space exposure and asthma. To assess potential effect modification by weight status, we tested an interaction term between grey space and weight group in the multivariable logistic regression model. The interaction was evaluated by including the product term (grey × weight) and examining its statistical significance while adjusting for all covariates. Finally, a multinomial logistic regression model was used to assess the interaction between grey and overweight/obesity using the combined variable and adjusting for the potential confounders. To assess the additive interaction between exposure to grey (high vs. low) and weight status (overweight/obese vs. normal/underweight), the two variables were combined into a four-level joint exposure variable (00 = low grey/underweight-normal weight; 10 = high grey/underweight-normal weight; 01 = low grey/overweight-obese; 11 = high grey/ overweight-obese). A binary logistic regression model was fitted to estimate the odds ratios for each exposure category, adjusting for relevant covariates. Based on these estimates, we calculated the following standard additive interaction measures: the Relative Excess Risk due to Interaction (RERI), the Attributable Proportion due to interaction (AP), and the Synergy Index (S). Confidence intervals of 95% were computed using the Delta method. More details on calculating additive measures are reported in the Supplementary Materials.

The odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. The statistical significance level was set at a p-value of 0.05.

Statistical analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 26.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) or R statistical software (R version 2025.09.2 Core Team, 2024).

3. Results

This study was conducted on a sample of 2841 subjects who filled in the questionnaire, as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the study sample (frequency distributions, means + SD) (n = 2841).

The sample consisted of 54.7% females, aged 8–97 years (mean age 48.0 ± 20.6 years), mainly with a low education level (75.6% with ≤8 years of education). The percentage of overweight people was 35.8%, while the percentage of obese people was 12.8%. Smokers made up 23.1% of the sample. Most of the subjects spent ≥2 h outdoors daily (56.4%) and had a low grey space exposure (67.6%); 18.7% had an asthma diagnosis or symptoms (Table 1).

In Table 2, the distribution of risk factors in relation to asthma diagnosis/symptoms is reported.

Table 2.

Prevalence (%) or mean value of risk factors in relation to asthma symptoms/diagnosis.

The table shows that all the variables considered in the analyses present a statistically significant difference between the three categories of the outcome. A higher percentage of subjects ≤ 18 yrs emerged in those without asthma symptoms and diagnosis (37.2%), while a higher percentage of >59 yrs subjects emerged in those with an asthma diagnosis (38.8%); males were prevalent in those with symptoms without diagnosis (66.2%). With regard to education levels, low education level (≤8 yrs) was significantly more frequent in those with an asthma diagnosis (81.1%). Smokers and ex-smokers were more frequent in those with symptoms without diagnosis (44.3% and 33.8%, respectively). The percentage of subjects who spent less than two hours a day outdoors was higher in subjects with asthmatic symptoms without diagnosis (49.5%). Although the mean level of grey space did not significantly differ across the asthma symptoms/diagnosis categories (p-value = 0.19), high grey exposure was borderline associated with having symptoms without diagnosis (37.8%). Finally, considering BMI categories, both overweight and obese subjects had a higher percentage in those with asthmatic symptoms without diagnosis (44.3% and 17.5%, respectively).

Table 3 shows the results of the multinomial logistic regression model on the total sample (n = 2834).

Table 3.

Risk factors for asthma symptoms/diagnosis in the total sample (n = 2834): OR and 95% CI.

Apart from males, smokers, ex-smokers and <2 h a day outdoor, being overweight (OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.08–1.88), being obese (OR 1.99, 95% CI 1.38–2.88) and an increase of 10% in grey space exposure (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.01–1.13) were associated with asthma symptoms without diagnosis. No association was found with asthma diagnosis ± symptoms.

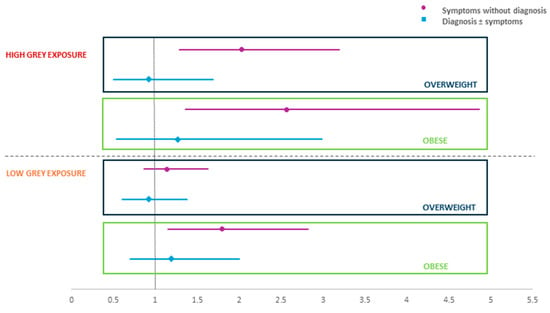

Figure 1 shows the results of the multinomial logistic regression models after stratification by high exposure to grey spaces (n = 919) and low exposure (n = 1915).

Figure 1.

Effect of BMI on asthma symptoms/diagnosis in subjects with high/low grey space exposure: OR and 95% CI.

Being overweight (OR 2.03, 95% CI 1.29–3.19) and being obese (OR 2.57, 95% CI 1.36–4.86) were significantly associated with asthma symptoms in subjects with high grey exposure. Obesity (OR 1.80, 95% CI 1.15–2.82) was also found to be associated with asthma symptoms in subjects with a low grey exposure. More detailed results are contained in Tables S1 and S2 of the Supplementary Materials.

In addition to the main models, we performed a causal mediation analysis to evaluate whether the association between grey space (exposure) and asthma (outcome) was mediated by weight status, while adjusting for age, sex, level of education, smoking habits and hours spent outdoors.

We fitted a logistic regression model for the mediator (weight status) and a logistic regression model for the outcome, including both grey space and weight status, and then applied the mediate function (R package mediation) with 4000 simulations and robust standard errors. The mediation analysis showed that the indirect effect of grey space on asthma through weight status was essentially absent and not statistically significant, indicating that weight does not act as a mediator in this relationship. Conversely, the direct effect of grey space on asthma remained statistically significant, and the total effect closely reflected this direct component.

We also evaluated whether the effect of grey space on asthma differed by weight status by including an interaction term between grey space and weight group in the logistic regression model, adjusting for age, sex, education, smoking and hours outdoors. The interaction term was not statistically significant, and we did not observe any clear pattern suggesting effect modification by weight status.

Taken together, the mediation and interaction analyses suggest that weight status neither mediates nor modifies the association between grey space and asthma in this cohort.

Table 4 shows the results of the multinomial regression model in which the combined variable of grey and BMI was used.

Table 4.

Risk factors for asthma symptoms/diagnosis considering the combined variable BMI–grey space exposure: OR and 95% CI.

Exposure to both overweight/obesity and high grey space (≥63%) was associated with a 2.5-fold higher odds of having asthma symptoms without diagnosis (OR 2.53, 95% CI 1.36–4.71) compared to subjects without symptoms/diagnosis; subjects exposed only to overweight/obesity showed borderline lower odds (OR 1.37, 95% CI 0.99–1.88). These results suggest a synergistic interaction between BMI and grey space exposure.

To estimate the interaction effect of weight and grey, the calculation of the additive measures was carried out, and the results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results of the calculation of additive measures.

The results show a positive interaction on an additive scale (relative excess risk due to interaction—RERI: 0.84), an attributable proportion (AP) of 0.32, namely 32% of the effect (asthma symptoms) in subjects exposed to both overweight/obesity and high grey spaces is attributable to interaction and a synergistic interaction (i.e., the joint effect is 1.5 times larger than what would be expected if exposures were simply additive) (synergy index—S: 1.47). All the three measures indicate the presence of a positive interaction, although only AP is statistically significant, indicating that the interaction contributes significantly to symptoms among those exposed to both factors. Results regarding the diagnosis ± symptoms category are shown in the Supplementary Materials.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the association between body weight and asthma, as well as the role of the urban environment, particularly exposure to grey spaces in this relationship. In particular, our findings show that overweight or obesity is associated with increased odds of having asthma symptoms, and that this relationship is further enhanced by living in densely built and likely polluted urban areas. The association between overweight/obesity and asthma varies according to strata of grey space exposure, and the additive interaction analysis showed a significant attributable proportion, suggesting a possible positive departure from additivity.

The results showed that being overweight or obese increases the odds of asthma symptoms, in line with other evidence showing that a high BMI is associated with asthma and impaired lung function [38,39,40]. Moreover, asthma and obesity frequently co-occur, and individuals with obesity often experience a more severe form of asthma. This has led to the recognition of an “obesity-related asthma” phenotype, which may require tailored therapeutic approaches [41]. In fact, asthma patients with obesity usually have more frequent difficult-to-treat asthma, are less responsive to steroids, have poorer symptom control, larger use of medications, poorer quality of life and larger disease severity [42,43,44,45,46,47]. People with severe asthma begin to be less active, which leads to weight gain and is also linked to a larger use of drugs [48]. Indeed, several studies have highlighted how obesity worsens the inflammatory condition of patients, for example, by increasing the quantity of eosinophils and neutrophils in the blood and the release of pro-inflammatory mediators [49,50]. This pathogenic role of obesity and inflammatory conditions has been seen to play an important role in several diseases, including COPD and asthma [48,51]. High BMI has also a direct impact on the airways through increased airway hyperresponsiveness in asthmatic populations [52], and the effect of obesity on human airway smooth muscle is exaggerated in adult females [53]. The reduction of weight, leading to an improvement in systemic inflammation, is one of the intervention strategies that are currently used to contain the pathological complications related to obesity [54,55,56].

Moreover, our findings showed that an increase of 10% in grey space exposure is associated with asthma symptoms without diagnosis. Other studies have shown that air pollution is related to the prevalence of asthmatic symptoms, increased odds of asthma prevalence, hospital admissions for asthma and decreased lung function [57,58,59,60]. In particular, a more recent study suggests that elevated levels of vehicle exhaust outside the home increase the risk of onset and incident asthma among adults [61]. Some studies have also demonstrated epidemiological links between air pollution and increased respiratory tract infections in patients of all ages, which are considered the cause of asthma exacerbations [62,63]. Indeed, several inflammatory mechanisms link pollution to asthma, with airway epithelial cells forming the respiratory mucosa that acts as both a physical and immune barrier through tight junctions, mucus production, and innate immune responses [64]. Some epidemiological studies have also reported links between air pollution and increased respiratory tract infections, which are considered the cause of asthma exacerbations [65].

In our study, a modification effect emerged. Contrary to the absence of a mediation effect by weight, the results from the additive interaction analysis were still noteworthy. Although RERI and S did not reach statistical significance, the Attributable Proportion due to interaction (AP) indicated a meaningful departure from additivity, suggesting that a non-negligible share of the joint effect between grey space exposure and weight may be attributable to their interaction. The possible link between pollution and weight has been studied mainly in the paediatric population, highlighting that among children and adolescents in urban communities, the relationship between household pollution (fine particulate matter, nitric oxide and nicotine) and asthma symptoms was more pronounced among overweight and obese children [66,67]. The authors of these studies suggest that overweight may increase susceptibility to the pulmonary effects of indoor PM2.5 and NO2, and that the combination of overweight and high exposure to indoor pollutants in urban children with asthma may explain part of the disproportionate asthma morbidity observed in their population [66]. A very recent review suggests another type of relationship between pollution and obesity and, in particular, highlights that pollution promotes stress, leading to obesity [68].

A limitation of our study is that the data were collected in the 90’s, so there could be some differences compared to the conditions of the general population today. There is certainly no risk of overestimating the number of asthma cases given the growth in the disease prevalence of asthma in recent decades, which has reached a plateau only in recent years although not in all areas of the world [69]. Even considering the environment, in recent years an increase in urbanization has been observed which has led to an increase in the prevalence of allergic diseases and in the development and exacerbation of asthma [7]. Furthermore, as highlighted in previous studies [70,71] and other major European investigations [72,73], traffic-related air pollutants tend to exhibit strong spatial stability, with within-city spatial patterns remaining consistent over time, even when overall mean concentrations change. Based on this evidence, it is reasonable to assume that the relative differences (spatial contrasts) in average levels of grey space exposure across residential locations have also remained quite stable. In other words, the effect associated with a 10% increase in grey exposure in the past is likely still informative for present-day populations. The use of a questionnaire for data collection on one hand can be considered a limitation because it can be affected by a reporting bias; however, for large analytical epidemiology studies, it remains the primary means of data collection [74]. In addition, asthma status in our study was solely based on self-reported diagnosis and/or symptoms without objective clinical validation (e.g., spirometry or bronchodilator testing). This might introduce recall or diagnostic bias and should be taken into account when interpreting prevalence estimates. Future studies should include lung function measurements in order to avoid misclassification errors. The strength of our study is instead the large size of the population sample considered and in the use of a standardised questionnaire.

In summary, it has been increasingly recognised in recent decades that asthma is a highly heterogeneous disorder with diverse underlying mechanisms and pathways that result in variable responses to standard treatment in different subgroups or clinical phenotypes [75]. This highlights the need to identify the various asthmatic phenotypes and all the environmental and host factors that can influence such disease in order to create personalised intervention strategies for patients affected by different forms of the disease.

5. Conclusions

Our findings show that overweight and obesity are associated with increased odds of having asthma symptoms, and that these relationships are influenced by residential grey exposure: living in densely built and likely polluted urban areas increases the odds of asthma symptoms. Early identification of at-risk phenotypes may help prevent disease occurrence and progression, particularly in urban areas. By identifying environmental and individual factors that interact to increase asthma risk, this study provides evidence that can inform sustainable public health policies. Reducing exposure to grey space and improving preventive strategies for high-risk groups may help reduce long-term clinical burden and contribute to the sustainability of healthcare systems. Future longitudinal studies are needed to clarify causal pathways and guide effective prevention strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172411300/s1, Table S1. Risk factors for asthma symptoms in subjects with high grey space exposure (≥63%): OR and 95% CI; Table S2. Risk factors for asthma symptoms/diagnosis in subjects with low grey space exposure (<63%): OR and 95% CI; Table S3. Results of the calculation of additive measures for the variable Diagnosis ± symptoms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B. and I.S.; methodology, S.B. and I.S.; validation, G.V.; formal analysis, I.S. and A.A.A.; investigation, S.B. and G.V.; data curation, A.A.A., G.S. and S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, I.S.; writing—review and editing, I.S., S.M., G.S., P.S., S.T., G.V. and S.B.; supervision, S.B.; project administration, P.S.; funding acquisition, G.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the CNR-ENEL (Italian Electric Power Authority) ‘Interaction of Energy Systems with Human Health and Environment’ Project (1989) and by the Italian National Research Council Targeted Project ‘Prevention and Control Disease Factors-SP 2’ (Contract No. 91.00171.PF41; 1991).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because at the time of the survey, Italian regulations did not require approval from an Ethical Committee. An Internal Review Board within the National Research Council (CNR) Preventive Medicine Targeted Project endorsed the protocol in 1985.

Informed Consent Statement

Participants voluntarily and verbally agreed to take part in the study after they have been fully informed about all relevant aspects, including the purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits by the physicians/research personnel. Participants’ data were completely anonymised, ensuring that individuals could not be identified.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. 2024. Available online: https://ginasthma.org/2024-report/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Global Initiative for Asthma—GINA. World Asthma Day. 2024. Available online: https://ginasthma.org/world-asthma-day-2024/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Asher, M.I.; García-Marcos, L.; Pearce, N.E.; Strachan, D.P. Trends in Worldwide Asthma Prevalence. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 2002094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldacci, S.; Maio, S.; Cerrai, S.; Sarno, G.; Baïz, N.; Simoni, M.; Annesi-Maesano, I.; Viegi, G. Allergy and Asthma: Effects of the Exposure to Particulate Matter and Biological Allergens. Respir. Med. 2015, 109, 1089–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Moual, N.; Jacquemin, B.; Varraso, R.; Dumas, O.; Kauffmann, F.; Nadif, R. Environment and Asthma in Adults. Presse Med. 2013, 42, e317–e333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trepka, M.J.; Heinrich, J.; Wichmann, H.E. The Epidemiology of Atopic Diseases in Germany: An East-West Comparison. Rev. Environ. Health 1996, 11, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrison, L.B.; Brandt, E.B.; Myers, J.B.; Hershey, G.K.K. Environmental Exposures and Mechanisms in Allergy and Asthma Development. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 1504–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuder, M.M.; Nyenhuis, S.M. Optimizing Lifestyle Interventions in Adult Patients with Comorbid Asthma and Obesity. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2020, 14, 1753466620906323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvaniti, F.; Priftis, K.N.; Papadimitriou, A.; Yiallouros, P.; Kapsokefalou, M.; Anthracopoulos, M.B.; Panagiotakos, D.B. Salty-Snack Eating, Television or Video-Game Viewing, and Asthma Symptoms among 10- to 12-Year-Old Children: The PANACEA Study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamga, A.; Rochefort-Morel, C.; Guen, Y.L.; Ouksel, H.; Pipet, A.; Leroyer, C. Asthma and Smoking: A Review. Respir. Med. Res. 2022, 82, 100916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute For Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021) Socio-Demographic Index (SDI) 1950–2021. 2024. Available online: https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/global-burden-disease-study-2021-gbd-2021-socio-demographic-index-sdi-1950%E2%80%932021 (accessed on 15 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Tao, J.; Wang, J.; She, W.; Zou, Y.; Li, R.; Ma, Y.; Sun, C.; Bi, S.; Wei, S.; et al. Global, Regional, National Burden of Asthma from 1990 to 2021, with Projections of Incidence to 2050: A Systematic Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. EClinicalMedicine 2025, 80, 103051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, U.; Dixon, A.E.; Forno, E. Obesity and Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 141, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuther, D.A.; Sutherland, E.R. Overweight, Obesity, and Incident Asthma: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Epidemiologic Studies. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 175, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Rio, F.; Alvarez-Puebla, M.J.; Esteban-Gorgojo, I.; Barranco, P.; Olaguibel, J.M. Obesity and Asthma: Key Clinical Questions. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2019, 29, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacon, S.L.; Lemiere, C.; Moullec, G.; Ninot, G.; Pepin, V.; Lavoie, K.L. Association between Patterns of Leisure Time Physical Activity and Asthma Control in Adult Patients. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2015, 2, e000083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pistelli, F.; Bottai, M.; Carrozzi, L.; Pede, F.D.; Baldacci, S.; Maio, S.; Brusasco, V.; Pellegrino, R.; Viegi, G. Changes in Obesity Status and Lung Function Decline in a General Population Sample. Respir. Med. 2008, 102, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). 7 Million Premature Deaths Annually Linked to Air Pollution. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/25-03-2014-7-million-premature-deaths-annually-linked-to-air-pollution (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Health Effects of Particulate Matter. 2013. Available online: https://unece.org/DAM/env/documents/2013/air/Health-effects-of-particulate-matter-final-Eng.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- State of Global Air State of Global Air Report. 2024. Available online: https://www.stateofglobalair.org/resources/report/state-global-air-report-2024 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Li, Z.; Xu, X.; Thompson, L.A.; Gross, H.E.; Shenkman, E.A.; DeWalt, D.A.; Huang, I.-C. Longitudinal Effect of Ambient Air Pollution and Pollen Exposure on Asthma Control: The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Pediatric Asthma Study. Acad. Pediatr. 2019, 19, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentz, G.; Robins, T.G.; Batterman, S.; Naidoo, R.N. Effect Modifiers of Lung Function and Daily Air Pollutant Variability in a Panel of Schoolchildren. Thorax 2019, 74, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; Phaneuf, D.J.; Barrett, M.A.; Su, J.G. Short-Term Impact of PM2.5 on Contemporaneous Asthma Medication Use: Behavior and the Value of Pollution Reductions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 5246–5253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, B.; Liu, C.; Chen, R.; Kan, H.; Sun, J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, C.; Sun, Q.; Bai, H. Associations between Short-Term Exposure to Fine Particulate Matter and Acute Exacerbation of Asthma in Yancheng, China. Chemosphere 2019, 237, 124497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcala, E.; Brown, P.; Capitman, J.A.; Gonzalez, M.; Cisneros, R. Cumulative Impact of Environmental Pollution and Population Vulnerability on Pediatric Asthma Hospitalizations: A Multilevel Analysis of CalEnviroScreen. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Pan, J.; Zhang, H.; Shi, C.; Li, G.; Peng, Z.; Ma, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L. Short-Term Exposure to Ambient Air Pollution and Asthma Mortality. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sompornrattanaphan, M.; Thongngarm, T.; Ratanawatkul, P.; Wongsa, C.; Swigris, J.J. The Contribution of Particulate Matter to Respiratory Allergy. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 38, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manisalidis, I.; Stavropoulou, E.; Stavropoulos, A.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Environmental and Health Impacts of Air Pollution: A Review. Front. Public. Health 2020, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GINA Reports. Global Initiative for Asthma-GINA. Available online: https://ginasthma.org/reports/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Copernicus CORINE Land Cover. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/en/products/corine-land-cover (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Cos’è la Copertura del Suolo CORINE? Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/it/help/domande-frequenti/cos2019e-la-copertura-del-suolo-corine (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Parmes, E.; Pesce, G.; Sabel, C.E.; Baldacci, S.; Bono, R.; Brescianini, S.; D’Ippolito, C.; Hanke, W.; Horvat, M.; Liedes, H.; et al. Influence of Residential Land Cover on Childhood Allergic and Respiratory Symptoms and Diseases: Evidence from 9 European Cohorts. Environ. Res. 2020, 183, 108953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosztra, B.; Büttner, G.; Hazeu, G.; Arnold, S. Updated CLC Illustrated Nomenclature Guidelines. 2019. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/content/corine-land-cover-nomenclature-guidelines/docs/pdf/CLC2018_Nomenclature_illustrated_guide_20190510.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Lin, L.; Li, T.; Sun, M.; Liang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Wang, F.; Duan, J.; Sun, Z. Global Association between Atmospheric Particulate Matter and Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Res. 2022, 209, 112785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maio, S.; Baldacci, S.; Carrozzi, L.; Pistelli, F.; Simoni, M.; Angino, A.; La Grutta, S.; Muggeo, V.; Viegi, G. 18-Yr Cumulative Incidence of Respiratory/Allergic Symptoms/Diseases and Risk Factors in the Pisa Epidemiological Study. Respir. Med. 2019, 158, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegi, G.; Pedreschi, M.; Baldacci, S.; Chiaffi, L.; Pistelli, F.; Modena, P.; Vellutini, M.; Di Pede, F.; Carrozzi, L. Prevalence Rates of Respiratory Symptoms and Diseases in General Population Samples of North and Central Italy. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 1999, 3, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Simoni, M.; Biavati, P.; Carrozzi, L.; Viegi, G.; Paoletti, P.; Matteucci, G.; Ziliani, G.L.; Ioannilli, E.; Sapigni, T. The Po River Delta (North Italy) Indoor Epidemiological Study: Home Characteristics, Indoor Pollutants, and Subjects’ Daily Activity Pattern. Indoor Air 1998, 8, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaaby, T.; Taylor, A.E.; Thuesen, B.H.; Jacobsen, R.K.; Friedrich, N.; Møllehave, L.T.; Hansen, S.; Larsen, S.C.; Völker, U.; Nauck, M.; et al. Estimating the Causal Effect of Body Mass Index on Hay Fever, Asthma and Lung Function Using Mendelian Randomization. Allergy 2018, 73, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.E.; Wood, L.G.; Gibson, P.G. Obesity and Childhood Asthma–Mechanisms and Manifestations. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 12, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Soomer, K.; Vaerenberg, H.; Weyler, J.; Pauwels, E.; Cuypers, H.; Verbraecken, J.; Oostveen, E. Effects of Weight Change and Weight Cycling on Lung Function in Overweight and Obese Adults. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2024, 21, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tooba, R.; Wu, T.D. Obesity and Asthma: A Focused Review. Respir. Med. 2022, 204, 107012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.; Mannino, D.; Brown, C.; Crocker, D.; Twum-Baah, N.; Holguin, F. Body Mass Index and Asthma Severity in the National Asthma Survey. Thorax 2008, 63, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutherland, E.R.; Goleva, E.; Strand, M.; Beuther, D.A.; Leung, D.Y.M. Body Mass and Glucocorticoid Response in Asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 178, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanescu, S.; Kirby, S.E.; Thomas, M.; Yardley, L.; Ainsworth, B. A Systematic Review of Psychological, Physical Health Factors, and Quality of Life in Adult Asthma. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2019, 29, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klepaker, G.; Svendsen, M.V.; Hertel, J.K.; Holla, Ø.L.; Henneberger, P.K.; Kongerud, J.; Fell, A.K.M. Influence of Obesity on Work Ability, Respiratory Symptoms, and Lung Function in Adults with Asthma. Respiration 2019, 98, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthe, S.K.; Hirayama, A.; Goto, T.; Faridi, M.K.; Camargo, C.A.J.; Hasegawa, K. Association Between Obesity and Acute Severity Among Patients Hospitalized for Asthma Exacerbation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 1936–1941.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pate, C.A.; Zahran, H.S.; Bailey, C.M. Impaired Health-Related Quality of Life and Related Risk Factors among US Adults with Asthma. J. Asthma 2019, 56, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Cowan, D.C. Obesity, Inflammation, and Severe Asthma: An Update. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2021, 21, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalovich, D.; Rodriguez-Perez, N.; Smolinska, S.; Pirozynski, M.; Mayhew, D.; Uddin, S.; Van Horn, S.; Sokolowska, M.; Altunbulakli, C.; Eljaszewicz, A.; et al. Obesity and Disease Severity Magnify Disturbed Microbiome-Immune Interactions in Asthma Patients. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunadome, H.; Matsumoto, H.; Izuhara, Y.; Nagasaki, T.; Kanemitsu, Y.; Ishiyama, Y.; Morimoto, C.; Oguma, T.; Ito, I.; Murase, K.; et al. Correlation between Eosinophil Count, Its Genetic Background and Body Mass Index: The Nagahama Study. Allergol. Int. 2020, 69, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, C.; LeVan, T. Obesity and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Recent Knowledge and Future Directions. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2017, 23, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampuch, A.; Milewski, R.; Rogowska, A.; Kowal, K. Predictors of Airway Hyperreactivity in House Dust Mite Allergic Patients. Adv. Respir. Med. 2019, 87, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orfanos, S.; Jude, J.; Deeney, B.T.; Cao, G.; Rastogi, D.; van Zee, M.; Pushkarsky, I.; Munoz, H.E.; Damoiseaux, R.; Di Carlo, D.; et al. Obesity Increases Airway Smooth Muscle Responses to Contractile Agonists. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2018, 315, L673–L681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, K.; Pontillo, A.; Di Palo, C.; Giugliano, G.; Masella, M.; Marfella, R.; Giugliano, D. Effect of Weight Loss and Lifestyle Changes on Vascular Inflammatory Markers in Obese Women: A Randomized Trial. JAMA 2003, 289, 1799–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farias, T.D.S.M.D.; Paixao, R.I.D.; Cruz, M.M.; de Sa, R.D.C.D.C.; Simão, J.D.J.; Antraco, V.J.; Alonso-Vale, M.I.C. Melatonin Supplementation Attenuates the Pro-Inflammatory Adipokines Expression in Visceral Fat from Obese Mice Induced by A High-Fat Diet. Cells 2019, 8, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Gay, M.A.; De Matias, J.M.; Gonzalez-Juanatey, C.; Garcia-Porrua, C.; Sanchez-Andrade, A.; Martin, J.; Llorca, J. Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Blockade Improves Insulin Resistance in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2006, 24, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Nitta, H.; Sato, T.; Nakai, S.; Maeda, K.; Aoki, S.; Ono, M. Respiratory Health Associated with Exposure to Automobile Exhaust. I. Results of Cross-Sectional Studies in 1979, 1982, and 1983. Arch. Environ. Health 1993, 48, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemp, E.; Elsasser, S.; Schindler, C.; Künzli, N.; Perruchoud, A.P.; Domenighetti, G.; Medici, T.; Ackermann-Liebrich, U.; Leuenberger, P.; Monn, C.; et al. Long-Term Ambient Air Pollution and Respiratory Symptoms in Adults (SAPALDIA Study). The SAPALDIA Team. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1999, 159, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckeridge, D.L.; Glazier, R.; Harvey, B.J.; Escobar, M.; Amrhein, C.; Frank, J. Effect of Motor Vehicle Emissions on Respiratory Health in an Urban Area. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002, 110, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, D.; Zhu, Y.; Luo, J.; Zhang, Y. Associations among Air Pollution, Asthma and Lung Function: A Cross-Sectional Study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modig, L.; Torén, K.; Janson, C.; Jarvholm, B.; Forsberg, B. Vehicle Exhaust Outside the Home and Onset of Asthma among Adults. Eur. Respir. J. 2009, 33, 1261–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, S.; Galeone, C.; Lelii, M.; Longhi, B.; Ascolese, B.; Senatore, L.; Prada, E.; Montinaro, V.; Malerba, S.; Patria, M.F.; et al. Impact of Air Pollution on Respiratory Diseases in Children with Recurrent Wheezing or Asthma. BMC Pulm. Med. 2014, 14, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwa, K.; Eckert, C.M.; Vedal, S.; Hajat, A.; Kaufman, J.D. Ambient Air Pollution and Risk of Respiratory Infection among Adults: Evidence from the Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2021, 8, e000866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bontinck, A.; Maes, T.; Joos, G. Asthma and Air Pollution: Recent Insights in Pathogenesis and Clinical Implications. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2020, 26, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiotiu, A.I.; Novakova, P.; Nedeva, D.; Chong-Neto, H.J.; Novakova, S.; Steiropoulos, P.; Kowal, K. Impact of Air Pollution on Asthma Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 6212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.D.; Brigham, E.P.; Peng, R.; Koehler, K.; Rand, C.; Matsui, E.C.; Diette, G.B.; Hansel, N.N.; McCormack, M.C. Overweight/Obesity Enhances Associations between Secondhand Smoke Exposure and Asthma Morbidity in Children. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 2157–2159.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.D.; Breysse, P.N.; Diette, G.B.; Curtin-Brosnan, J.; Aloe, C.; Williams, D.L.; Peng, R.D.; McCormack, M.C.; Matsui, E.C. Being Overweight Increases Susceptibility to Indoor Pollutants among Urban Children with Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 131, 1017–1023, 1023.e1–1023.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kouche, S.; Halvick, S.; Morel, C.; Duca, R.-C.; van Nieuwenhuyse, A.; Turner, J.D.; Grova, N.; Meyre, D. Pollution, Stress Response, and Obesity: A Systematic Review. Obes. Rev. 2025, 26, e13895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, J.; Pier, J.; Litonjua, A.A. Asthma Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Semin. Immunopathol. 2020, 42, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, G. Methods for Assessing Long-Term Exposures to Outdoor Air Pollutants. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2017, 4, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasola, S.; Maio, S.; Baldacci, S.; La Grutta, S.; Ferrante, G.; Forastiere, F.; Stafoggia, M.; Gariazzo, C.; Viegi, G.; Group, O.B.O.T.B.C. Effects of Particulate Matter on the Incidence of Respiratory Diseases in the Pisan Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, S.H.; Schindler, C.; Liu, L.-J.S.; Keidel, D.; Bayer-Oglesby, L.; Brutsche, M.H.; Gerbase, M.W.; Keller, R.; Künzli, N.; Leuenberger, P.; et al. Reduced Exposure to PM10 and Attenuated Age-Related Decline in Lung Function. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 2338–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schikowski, T.; Adam, M.; Marcon, A.; Cai, Y.; Vierkötter, A.; Carsin, A.E.; Jacquemin, B.; Al Kanani, Z.; Beelen, R.; Birk, M.; et al. Association of Ambient Air Pollution with the Prevalence and Incidence of COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 44, 614–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakke, P.S.; Rönmark, E.; Eagan, T.; Pistelli, F.; Annesi-Maesano, I.; Maly, M.; Meren, M.; Vermeire Dagger, P.; Vestbo, J.; Viegi, G.; et al. Recommendations for Epidemiological Studies on COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2011, 38, 1261–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiteneder, H.; Peng, Y.-Q.; Agache, I.; Diamant, Z.; Eiwegger, T.; Fokkens, W.J.; Traidl-Hoffmann, C.; Nadeau, K.; O’Hehir, R.E.; O’Mahony, L.; et al. Biomarkers for Diagnosis and Prediction of Therapy Responses in Allergic Diseases and Asthma. Allergy 2020, 75, 3039–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).