Abstract

Mangrove sediments in the South China Sea, particularly in the Hainan Island region, play a crucial role in regulating heavy metal migration and sequestration. However, the impact of converting mangrove areas to fish and shrimp culture ponds on heavy metal pollution in the Bamen Bay Mangrove Reserve is unclear. This study evaluates the pollution levels and ecological risks of Cr, Zn, Pb, Cu, and As in sediments from three land-use types using pollution indices (CF, PLI, RI) and the geo-accumulation index (Igeo). Multivariate analysis explores the relationships between metals and their potential sources. The results show significant differences in pollution levels (p < 0.05), with culture ponds having the highest pollution and ecological risk (RI = 73). As is the primary ecological risk factor (Er = 129). Zn and Cr are positively correlated with organic matter, while As and Pb show negative correlations with pH and salinity. Culture ponds increase heavy metal load and ecological risk, adversely impacting the mangrove ecosystem. These findings provide scientific support for land-use management and pollution control in mangrove wetlands.

1. Introduction

Mangroves are halophytic woody plant communities that grow in tropical and subtropical intertidal zones, providing critical ecological, social, and economic functions. The eastern coast of Hainan Island, located in the tropics, hosts one of the most well-preserved mangrove wetlands in China. Its sediments have been shown to effectively sequester heavy metals derived from riverine inputs and nearshore anthropogenic activities, thereby serving as an important medium for the transport and ultimate fate of regional pollutants [1,2]. Previous studies have demonstrated that different land-use types can markedly influence the speciation and accumulation levels of heavy metals in mangrove sediments, consequently altering their environmental behavior [3]. As a key coastal ecosystem involved in nutrient cycling, pollutant retention, and ecological stability, the mangroves of Hainan play an irreplaceable role in contaminant immobilization, nutrient dynamics, and sustaining coastal fishery production [4,5].

Behind these ecological functions, mangrove sediments play a crucial role as a key medium in biogeochemical cycles, particularly in the migration and transformation of heavy metals. Through processes such as physical interception, adsorption, and precipitation, mangrove sediments effectively sequester and immobilize pollutants from both terrestrial and marine sources [6,7]. Additionally, the unique environmental conditions of mangroves, characterized by high organic matter content, fluctuating redox states, and intense microbial activity, significantly influence the transformation and migration of heavy metals [8]. Furthermore, influenced by tidal processes, the redox potential, salinity, and inundation frequency of mangrove sediments exhibit clear gradients across the intertidal zone, further shaping the physicochemical properties of the sediments. These complex physicochemical heterogeneities not only control the distribution of heavy metal chemical forms but also determine their mobility, bioavailability, and ecological risk levels [9].

Mangrove sediments, typically characterized by an anaerobic environment and high organic matter content, are widely regarded as significant sinks for various pollutants due to their strong adsorption and immobilization capacities [10,11,12]. This is particularly true for heavy metals, which attract considerable attention because of their high toxicity, persistence, non-degradability, and potential for bioaccumulation through the food chain [6,13,14]. Numerous studies have shown that elements such as As, Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Mo, Ni, Pb, and Zn are frequently detected in mangrove sediments [15,16], indicating a widespread pattern of contamination [10,13]. These heavy metals have consequently been recognized as one of the major potential threats to mangrove ecosystems [17]. These metals exhibit different environmental behaviors within ecosystems: Cr, Cu, and Zn play important roles in biological metabolism, but their excessive accumulation can lead to chronic toxicity [18], while elements like As, Cd, and Pb are not easily metabolized by organisms and pose significant toxicity even at very low concentrations, presenting long-term threats to both ecosystems and human health [19]. Therefore, understanding the sources, distribution, and geochemical behavior of heavy metals in mangrove sediments is crucial for assessing their environmental risk mechanisms.

However, the presence and migration of heavy metals in mangrove ecosystems are not only controlled by the inherent physicochemical conditions of the sediments but are also significantly influenced by external environmental factors, particularly land-use practices. For instance, in culture ponds, intensive feeding, the use of pharmaceuticals, and wastewater discharge often lead to the significant accumulation of heavy metals such as Cu [20]. In contrast, mudflats, acting as natural “sediment sinks” at the land–sea interface, are prone to accumulating metals like Cu, Pb, and Zn from river and estuarine inputs [21]. These differences indicate that various land-use types profoundly influence the spatial distribution and environmental behavior of heavy metals by altering the geochemical environment of sediments.

As one of China’s most species-rich mangrove wetlands with the most intact vegetation structure [22], the Bamen Bay Nature Reserve encompasses multiple land-use types, including mangroves, mudflats, and culture ponds, with a total area of 29.48 km2. Among these, mangroves cover 27.328 km2, while culture ponds occupy approximately 4 km2, accounting for 13% of the reserve area [23]. This adjacent spatial distribution provides ideal conditions for comparing the effects of different land-use types on heavy-metal behavior under the same natural environmental background. Previous studies have reported relatively high ecological risks associated with certain metals in mangrove sediments of Bamen Bay [24], further emphasizing the necessity of conducting comprehensive, cross-land-use-type investigations in this region.

However, existing studies have predominantly focused on the overall patterns of heavy-metal pollution in mangroves, while paying insufficient attention to how different land-use types within the same estuarine system influence sediment physicochemical properties as well as the accumulation and risk profiles of heavy metals. This knowledge gap limits the development of land-use-based, targeted pollution management strategies. Therefore, fine-scale comparative investigations across land-use types are needed to elucidate their specific effects on heavy-metal mobility and ecological risk. The objectives of this study are as follows: (1) characterize the spatial distribution, source apportionment, and ecological risks of heavy metals (Cr, Zn, Pb, Cu, and As) in mangrove sediments under different land-use types in Bamen Bay; (2) examine the influence of specific land-use categories on the enrichment and migration of heavy metals in mangrove sediments; (3) provide fundamental data to support the development of scientifically grounded pollution-control and ecological-restoration strategies for the mangrove region of Bamen Bay. By comparing multiple land-use types within a single estuarine system and integrating source apportionment, risk mechanisms, and geochemical processes, this study offers a comprehensive assessment of the environmental behavior of heavy metals, thereby providing scientific support for establishing a sustainable mangrove socio-ecological system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Soil Sampling

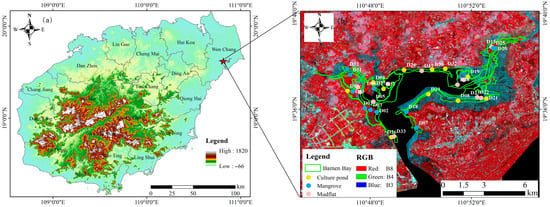

The study area is located within the Bamen Bay Nature Reserve in Wenchang City, Hainan Province, at the confluence of eight rivers, including the Wenchang River, which flows into the northern side of Qinglan port (Figure 1). This area exemplifies a typical estuarine wetland ecosystem. The climate is tropical marine monsoon, with an average annual temperature of 23.2 °C and annual precipitation of approximately 2000 mm, characterized by high temperatures and humidity. The tidal regime is diurnal, with a wide intertidal zone, a maximum tidal range of 2.38 m, a minimum tidal range of 0.01 m, and an average tidal range of 0.75 m [25]. Multiple potential sources of heavy-metal inputs are present in the vicinity of the study area. Agricultural zones located to the northwest may contribute metals to the estuarine system through surface runoff containing fertilizers and pesticides. Along the eastern and southern coastal margins, numerous marine culture ponds operate, where feed, detergents, and disturbances associated with aquaculture activities can introduce additional metal loads. Frequent vessel traffic and tourism activities in and around Bamen Bay may further influence water quality through antifouling paints, oil leaks, and waste discharge. Moreover, domestic wastewater effluents from surrounding villages and towns provide a background source of contamination for the region.

Figure 1.

(a) Map of the study area in Hainan Province; (b) Distribution of sampling sites and land-cover types in the Bamen Bay National Nature Reserve.

Sampling was conducted in the study area in May 2024, focusing on three distinct land-use types: mangrove, mudflat, and culture pond. Thirty-three representative sampling sites were established to ensure comprehensive spatial coverage (Table 1, Figure 2). At each sampling site, three small quadrats (25 cm × 25 cm) were established, from which five surface sediment sub-samples (0–5 cm) were collected in each quadrat. The 15 sub-samples (3 quadrats × 5 sub-samples) were then thoroughly mixed to form a composite sample representing the sampling site. All samples were stored in a refrigerated box, transported to the laboratory, and subsequently stored at −20 °C for further analysis.

Table 1.

Information about the sampling locations in Bamen Bay Natural Reserve.

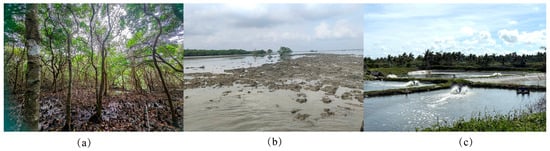

Figure 2.

Representative landscapes in Bamen Bay Natural Reserve: (a) mangrove, (b) mudflat, (c) culture pond.

2.2. Sample Preparation and Analytical Procedures

Frozen sediments were equilibrated to room temperature (approximately 24 °C) by passive thawing in airtight polyethylene bags. No drying or heating was applied during thawing to avoid water loss and changes in geochemical speciation. After complete thawing, the samples were homogenized and immediately subjected to physicochemical and metal analyses. Sediment samples were freeze-dried, ground, and sieved through a 100-mesh sieve. Following the US EPA 3052, approximately 0.3 g of each sample was weighed, and 10 mL of HNO3 and 2 mL of HF were added. The sample was then digested in a microwave digestion vessel at 600 W, with the temperature increasing from 30 °C to 150 °C at a rate of 5 °C·min−1. The digestion residue was dissolved in 1 mL of HNO3 and diluted to volume with ultra-pure water for Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) analysis. To ensure the accuracy and precision of the results, three replicate samples, method blanks, internal standards, and certified reference materials were included for quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC).

The concentrations of heavy metals (Cr, Zn, Pb, Cu, and As) in the sediments were determined using ICP-MS. To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the data, all samples underwent spike-recovery tests and procedural blanks were included for QA/QC. All glassware used in the experiment was soaked in 10% HNO3 for at least 24 h, followed by rinsing with boiling water and distilled water, and then dried. The measured concentrations of each element deviated from the reference values by less than ±10%, with analytical precision controlled within a range of 5–10% [26], the standard deviations ranged from 0.02 to 0.15 mg/kg. The recovery rates for Cr, Zn, Pb, Cu, and As were 97.9%, 106.0%, 95.7%, 99.4%, and 98.2%, respectively, with detection limits of 0.044, 0.026, 0.017, 0.032, and 0.053 μg·L−1 for each element [1].

In addition to heavy metals, several sediment environmental factors were measured, including pH, nitrogen (N), available phosphorus (AP), available potassium (AK), salinity, soil moisture content (SMC), soil organic matter (SOM), and cation exchange capacity (CEC). Sediment pH was measured in a 1:2.5 (w/v) sediment-to-deionized water suspension using a calibrated pH meter. N was determined using the Kjeldahl digestion method. AP was extracted with 0.5 mol·L−1 NaHCO3 (pH 8.5) and analyzed by the molybdenum blue colorimetric method, while AK was extracted with 1 mol·L−1 ammonium acetate and quantified using flame photometry. Salinity was measured from the electrical conductivity of a 1:5 sediment–water extract. SMC was calculated based on mass loss after oven-drying the samples at 105 °C to constant weight. SOM was determined using the dichromate oxidation (Walkley–Black) method. CEC was analyzed using the ammonium acetate (1 mol·L−1, pH 7) saturation method, followed by measurement of exchanged NH4+.

2.3. Contamination Assessment

To assess the degree of heavy metal contamination in sediments, the Contamination Factor (CF) and Pollution Load Index (PLI) were used for analysis. The calculation of CF and PLI was based on the method proposed by Tomlinson [27], with the following formulas:

In this context, Cn denotes the measured concentration of heavy metals in sediments, while Bn represents the background value for the corresponding element. The background value (Bn) refers to the natural concentration of heavy metals in the soil or sediments of a specific area when there is no pollution. Due to technical limitations, undisturbed deep (>50 cm) sediment cores were not obtained from the study area to establish local geochemical background values. This study adopted the background values reported by Sun et al. [28]. These studies systematically covered the major parent materials and soil types across Hainan Island, providing comprehensive elemental concentration ranges and statistical characteristics that represent the natural levels of soils in the region. The specific background values used in this study are listed in Table 2. The interpretation criteria for CF are as follows: CF < 1 indicates low pollution levels, 1 < CF < 3 indicates moderate pollution, 3 < CF < 6 indicates relatively high pollution, and CF ≥ 6 indicates very high pollution levels. PLI is used to assess overall environmental quality: PLI = 0 indicates no pollution, PLI = 1 indicates the presence of baseline pollution levels, and PLI > 1 indicates that the area is overall polluted.

Table 2.

The background value (Bn) of heavy metal concentrations in mangrove sediments.

2.4. Potential Ecological Risk Assessment

To assess the potential ecological risk of heavy metals in sediments, the potential ecological risk factor (Er) and potential ecological risk index (RI) were used for analysis. Er represents the potential ecological risk of an individual metal, whereas RI denotes the integrated ecological risk posed by all assessed metals. The calculation formulas are as follows:

Among these, represents the potential ecological risk factor for a single heavy metal, is the toxicity response coefficient for that element, is the pollution factor, and and are the measured concentration and background value (Bn as mentioned earlier) of the heavy metal, respectively. According to Hakanson [29], the values for Cu, Zn, Pb, Cr, and As are 5, 1, 5, 2, and 10, respectively. The classification standards for the Er and RI risk levels are also based on this study, as detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Classification of ecological risk indices used in this study.

2.5. Geo-Accumulation of Metals

The Geo-accumulation Index () is used to assess the degree of accumulation of heavy metals in sediments relative to geochemical background values, as detailed in the formula [30]:

The value is divided into seven levels to characterize different degrees of pollution: ≤ 0 indicates no pollution; 0 < ≤ 1 indicates no pollution to moderate pollution; 1 < ≤ 2 indicates moderate pollution; 2 < ≤ 3 indicates moderate-to-severe pollution; 3 < ≤ 4 indicates severe pollution; 4 < ≤ 5 indicates severe-to-extreme pollution; > 5 indicates extremely polluted [31].

2.6. Statistical Analysis of Data

To identify the potential sources of heavy metals in the sediments and the factors controlling their distribution, multivariate statistical analyses were applied to the elemental concentration data. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for significant differences in heavy-metal concentrations among different land-use types, thereby determining whether spatial variations were statistically meaningful. ANOVA is a commonly used and robust method for comparing multiple groups of sampling sites. Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to evaluate linear relationships among elements, revealing patterns of covariation that can indicate possible shared sources or similar migration behaviors [32]. To further resolve the complexity of mixed-source contamination, hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) was employed to group heavy metals with similar distribution patterns, while principal component analysis (PCA) was used to extract the major controlling factors and reduce data dimensionality, enabling the identification and validation of potential pollution sources from a multivariate perspective. In addition, a positive matrix factorization (PMF) model was introduced to quantitatively apportion the potential sources of heavy metals. By examining factor contributions and characteristic profiles, PMF provides a clearer understanding of the relative contributions and source features of various pollution categories, thereby enabling comprehensive source identification and cross-validation of heavy-metal inputs to the sediments.

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Distribution of Heavy Metal Concentrations

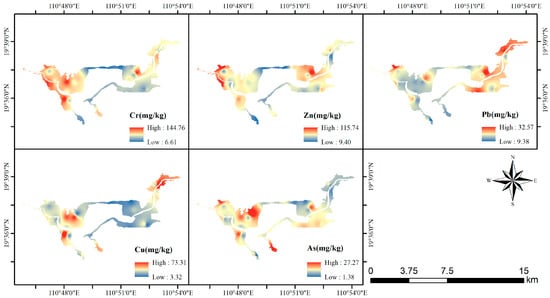

All heavy metals in Bamen Bay exhibited pronounced spatial heterogeneity, with high-concentration zones primarily distributed in the western and northeastern parts of the bay, while the central and southern areas generally displayed lower levels. Figure 3 illustrates the spatial distribution patterns of Cr, Zn, Pb, Cu, and As across the study area. The high-value regions of total Cr and Zn showed similar spatial patterns, forming a continuous belt of elevated concentrations along the western margin of the bay. Pb displayed marked enrichment in the northeastern sector, whereas Cu exhibited localized hotspots in the northern portion of the bay. Elevated As concentrations were mainly concentrated in the southwestern and northeastern extremities.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of heavy metals in Bamen Bay.

Overall, the five heavy metals demonstrated distinct spatial distribution characteristics. In certain areas, multiple metals appeared simultaneously enriched, forming localized high-value clusters, while other regions were dominated by low concentrations, resulting in a clearly differentiated spatial pattern.

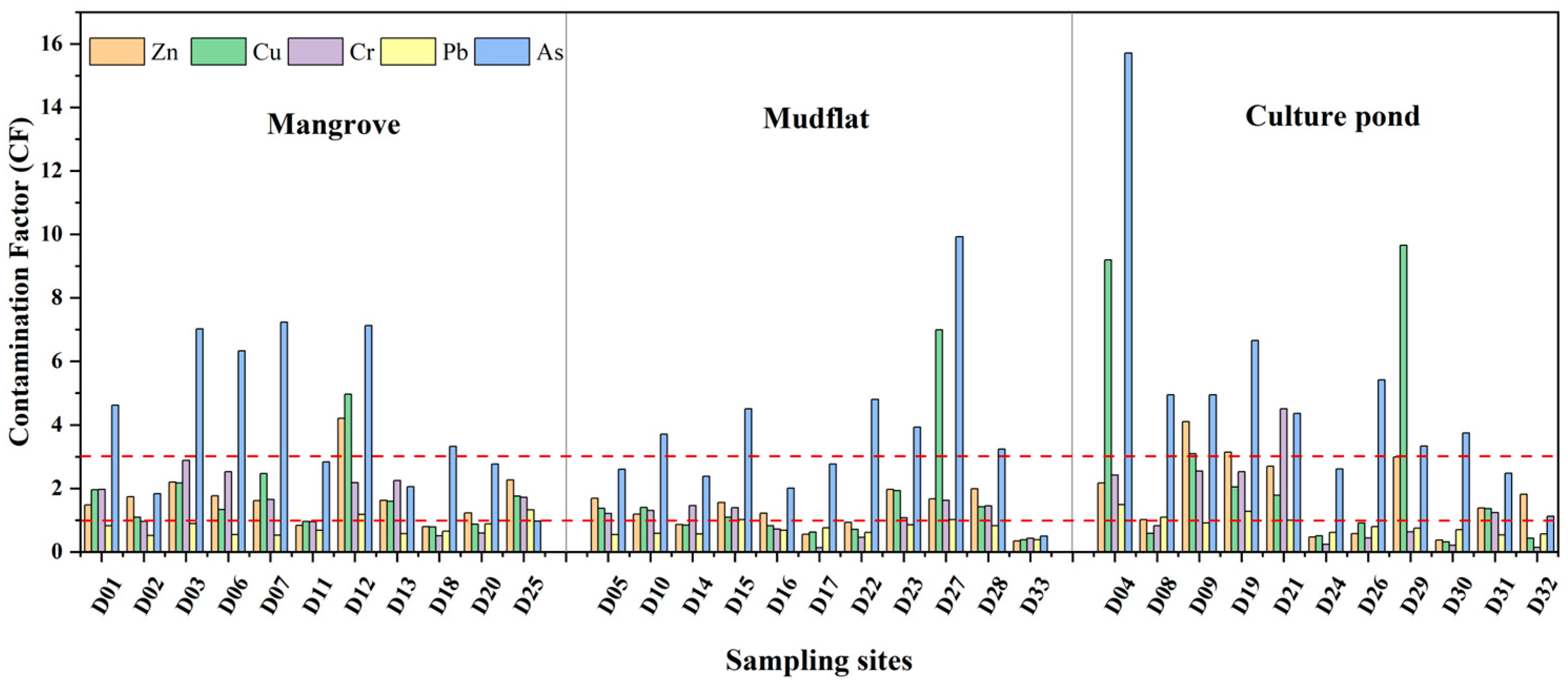

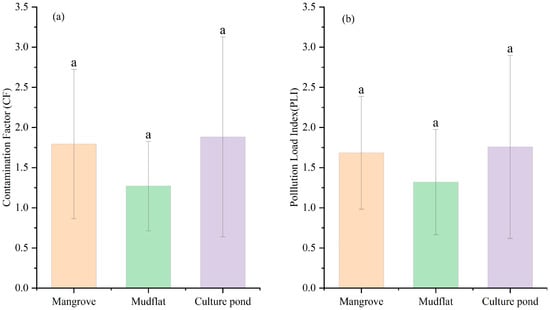

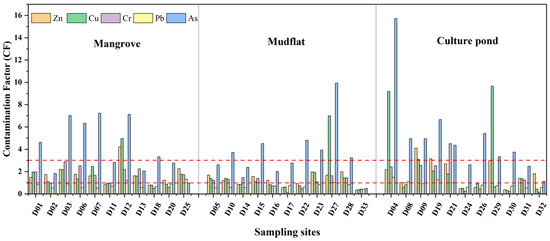

3.2. Heavy Metal Pollution Risks

The degree of heavy metal pollution varies across different regions (Figure 4a). Pb pollution is the least severe across all regions, while As pollution is generally more severe. As shown in Figure 5, Pb pollution is the least severe in mangrove areas, while Zn, Cu, and Cr predominantly exhibit moderate levels of pollution. As, with 45% of samples showing severe contamination, is the most significant pollutant in this region and requires special attention. In mudflat, Pb pollution remains the least severe, while Zn and Cr show varying levels of accumulation. Cu pollution is a mixture of mild and moderate levels. As accounts for 55% of severe pollution, making it the primary pollutant. In a culture pond, Pb and Cr were mostly mildly polluted, while Zn shows moderate pollution levels, but 18% of samples exhibit severe contamination, indicating a risk of accumulation. Cu pollution is relatively evenly distributed, whereas As has a severe pollution rate of 73%, making it the most prominent pollutant.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the (a) Contamination Factor (CF) and (b) Pollution Load Index (PLI) among different land-use types. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). Bars sharing the same letter are not significantly different, whereas bars with different letters differ significantly.

Figure 5.

Contamination factor (CF) of heavy metals in surface sediments of Bamen Bay mangrove.

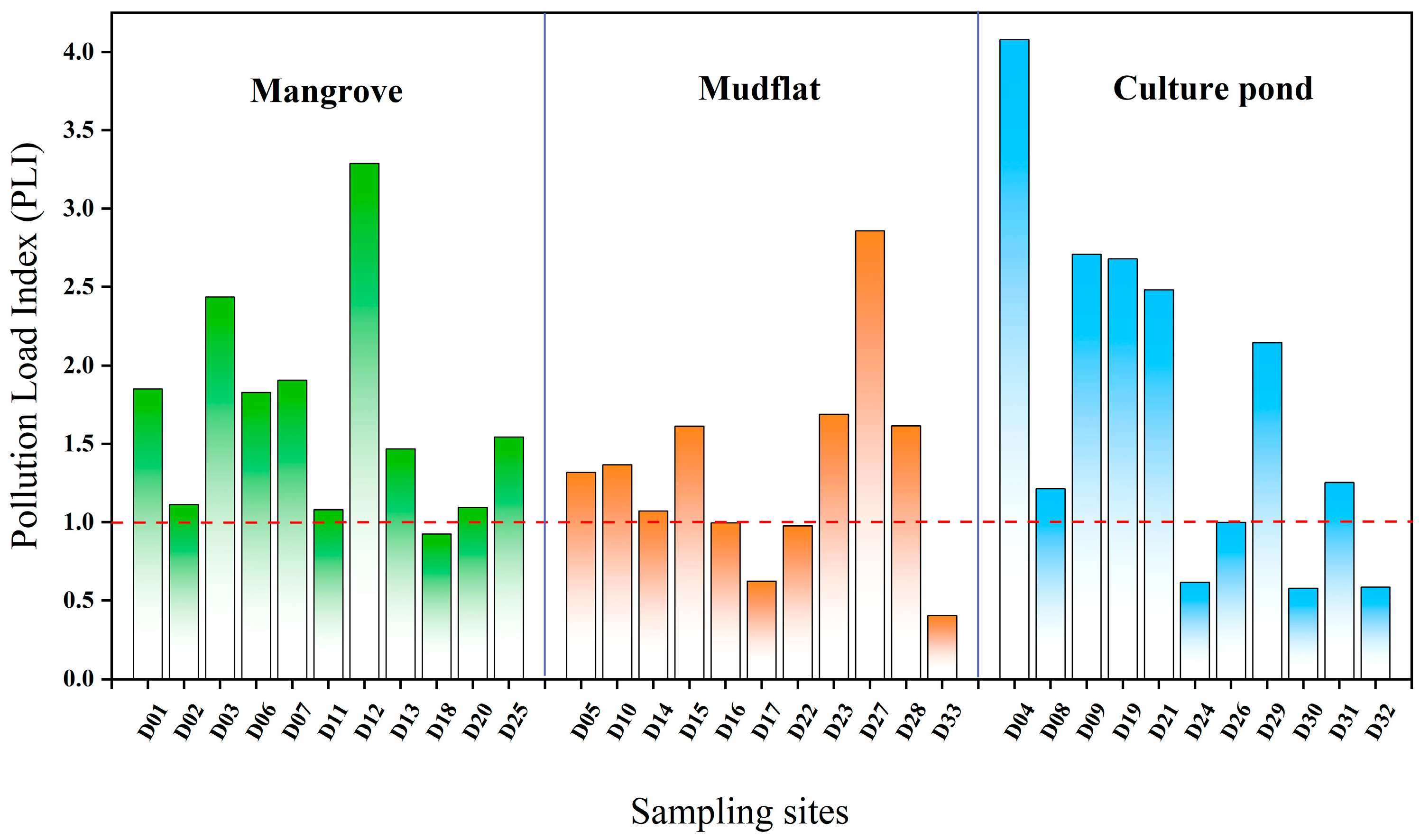

The pollution in the culture pond is the most significant, with localized high values and a more heterogeneous distribution. In contrast, the mangrove area has a broader extent of pollution, indicating significant variation in heavy metal pollution across different land-use types. Further identification of potential pollution sources is needed, in conjunction with land-use characteristics (Figure 4a). Figure 6 illustrates the distribution of PLI values at each sampling point across different land-use types. In mangrove, approximately 91% of sampling points had PLI values exceeding 1, with an average of 1.68, indicating widespread heavy metal accumulation and a broad range of pollution levels. In mudflat, around 64% of sampling points had PLI values greater than 1, with an average of 1.32, but there was considerable variation between points. For instance, the PLI value at sampling point D27 was notably higher than those at other points in the same area, while the PLI values at D17 and D33 were significantly below 1, highlighting substantial spatial heterogeneity in heavy metal pollution. In the culture pond, 63% of sampling points had PLI values exceeding 1, with an average of 1.76. The PLI value at sampling point D04 exceeds 4, the highest value in the entire study area, suggesting it may be influenced by strong anthropogenic pollution inputs, with significant local pollution load and generally higher overall pollution levels.

Figure 6.

Pollution load index (PLI) of heavy metals in surface sediments of Bamen Bay mangrove.

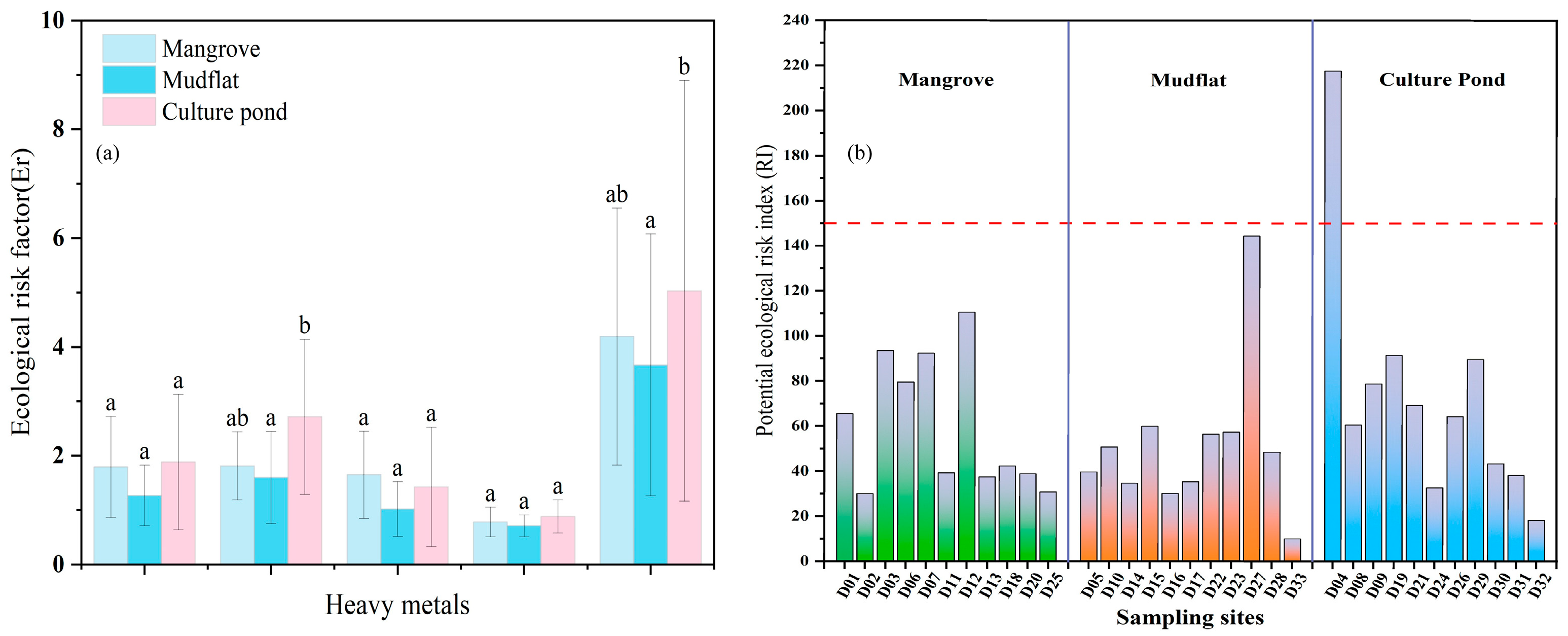

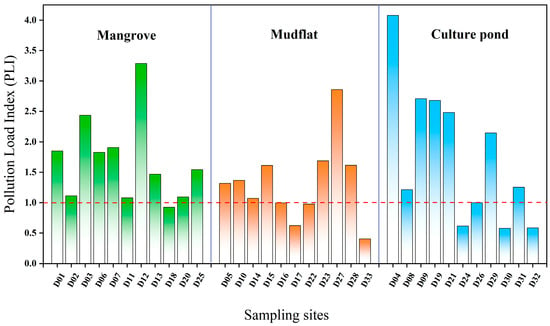

3.3. Potential Ecological Risk Evaluation

The ecological risk of the culture pond was higher than that of mangrove and mudflat, and As is the main ecological risk factor. As shown in Figure 7a, the Er for heavy metals in sediments from different land-use types display significant variability. The average Er values for Zn, Cu, Cr, and Pb are all below 40 across all regions, indicating that these metals pose a low ecological risk. In mudflat, the average Er value for As is also below 40. However, in mangrove and culture pond, the average Er values for As exceed 40, indicating a moderate ecological risk, with culture pond showing the highest value, reaching up to 50. When comparing the Er values of various heavy metals, the risk intensity follows this order: As > Cu > Pb > Cr > Zn, highlighting As as the primary contributor to potential ecological risk.

Figure 7.

Ecological risk factors ((a) Er and (b) RI) of heavy metals in surface sediments of Bamen Bay mangrove. The purple line indicates RI = 150, which represents the threshold for low risk. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). Bars sharing the same letter are not significantly different, whereas bars with different letters differ significantly.

Further integrating the results of the Ecological Risk Index (RI) allows for a comprehensive assessment of the overall risk level (Figure 7b). The RI values across the three areas range from 10 to 218, with an average of 60, ordered as follows: culture pond (73) > mangrove (60) > mudflat (52). Except for the D04 sampling point in the culture pond area (RI = 217), all other sampling points have RI values below 150, indicating a low ecological risk level. The high risk at D04 may be primarily attributed to its proximity to the culture pond, where wastewater discharge from aquaculture is likely the main source of contamination.

3.4. Geo-Accumulation of Heavy Metals

As is the most serious pollutant in all areas, but its performance varies in different areas, being relatively light in mudflat areas and highest in the culture pond. Table 4 presents the Igeo values for Zn, Cu, Cr, Pb, and As across different land-use types. Overall, the average Igeo values of heavy metals decrease in the order of As > Zn > Cu > Cr > Pb. Except for As, with an average Igeo value of 1.22, the average Igeo values for all other elements are below 0. When analyzed by region, in mangrove areas, the average Igeo values for Cr and Pb are both less than 0, indicating relatively low pollution. The average Igeo values for Zn and Cu range between 0 and 1, suggesting mild contamination, while the average Igeo values for As are between 1 and 2, indicating moderate contamination. As is the most severely contaminated element among all heavy metals in this region. In both mudflat and culture pond regions, the contamination pattern for As is similar, while the average Igeo values for the other metals remain below 0, indicating no contamination.

Table 4.

The values for the geo-accumulation index (Igeo) of metals in mangrove wetland with different land uses.

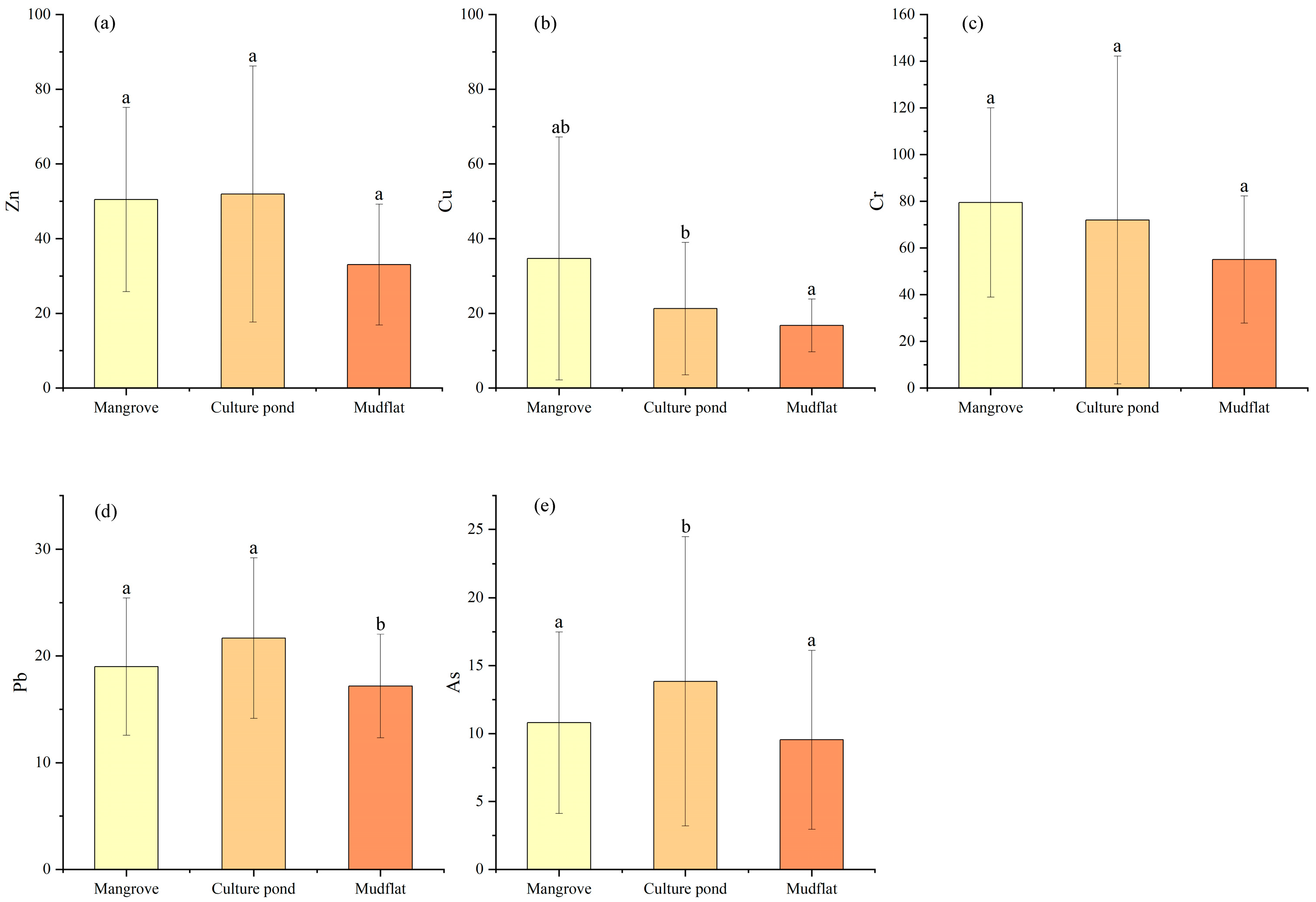

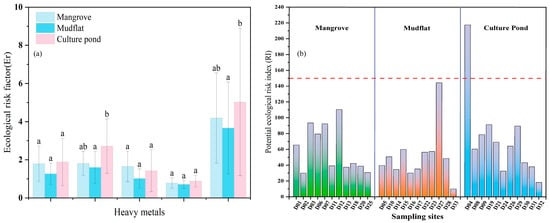

3.5. Differences and Source Distribution of Heavy Metals Under Different Land-Use Types

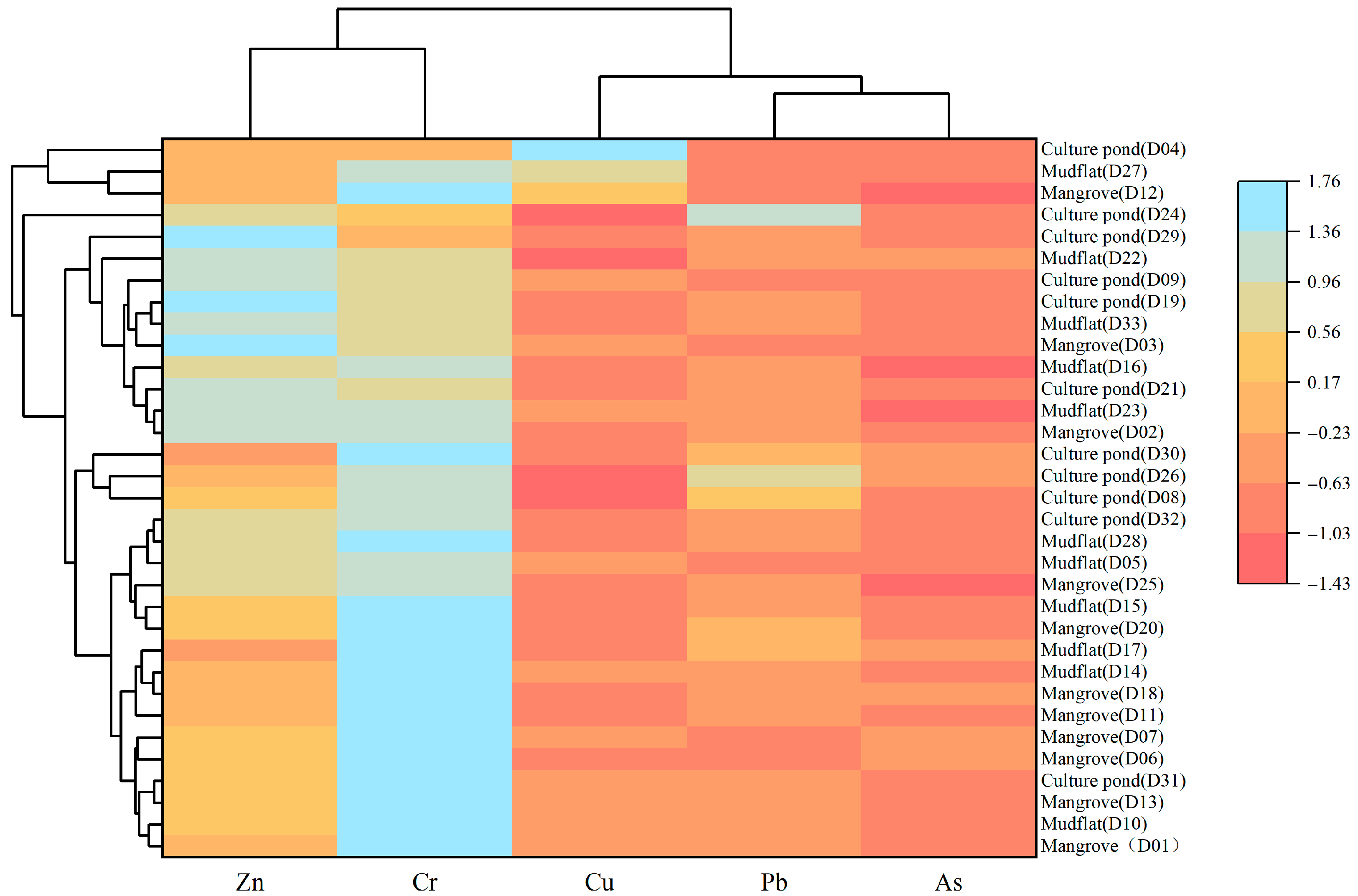

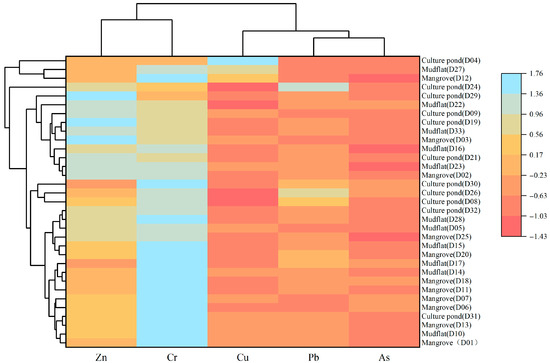

Zn and Cr may originate from similar pollution sources, while As and Pb appear to share a common source; however, the degree of contamination of these heavy metals varies among different land-use types, indicating spatial variability in pollution sources under different environmental conditions. ANOVA (Figure 8) revealed that several heavy metals showed significant differences among land-use types: only As exhibited a significant difference between the mangrove and culture pond, only Pb differed significantly between the mangrove and mudflat, while Cu, Pb, and As all showed significant differences between the mudflat and culture pond. Consistent with these findings, the HCA (Figure 9) grouped the five heavy metals into three distinct categories: Zn and Cr in one group, As and Pb in another, and Cu as a separate group. Cr showed relatively uniform distribution across all sampling sites with minimal variation, suggesting a relatively stable pollution source. In contrast, Cu, Pb, and As exhibited marked variations among land-use types, particularly between the mudflat and culture pond areas, suggesting stronger influence of land-use practices on their sources and accumulation processes.

Figure 8.

(a–e) Comparison of heavy metal concentrations across different land-use types. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05), bars sharing the same letter are not significantly different, whereas bars with different letters differ significantly.

Figure 9.

Heavy metal distribution patterns in different land-use based on heat maps and cluster analysis.

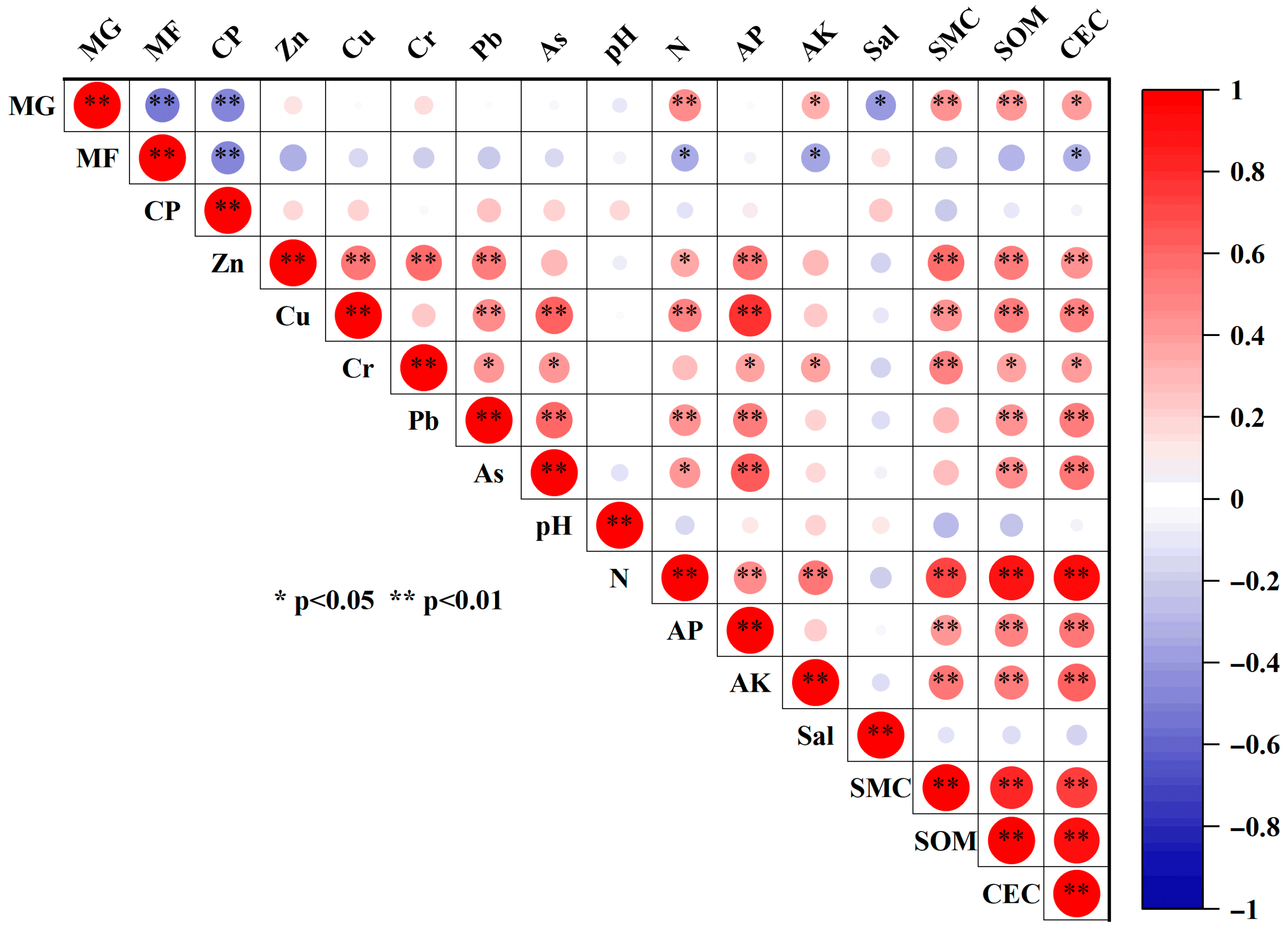

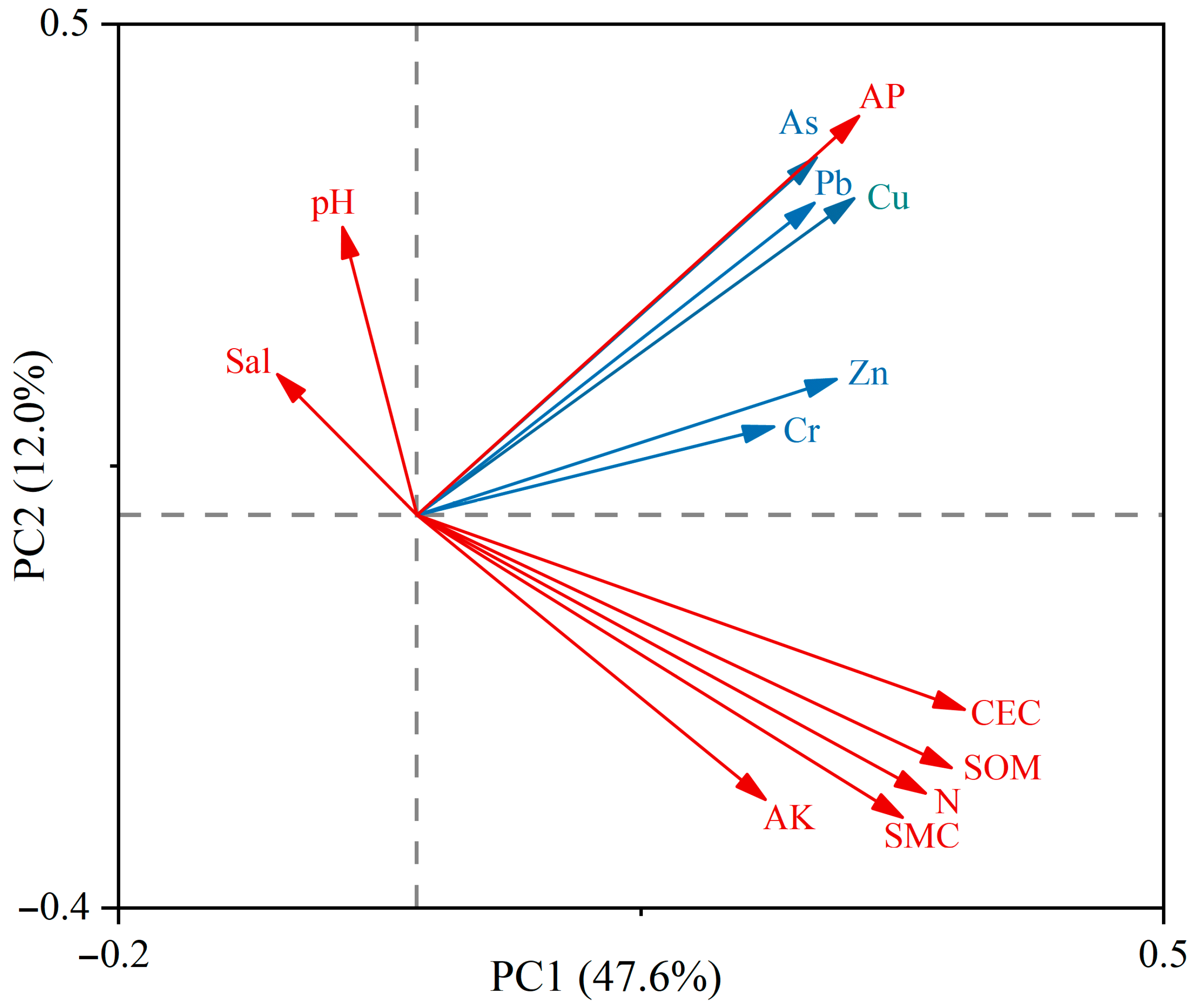

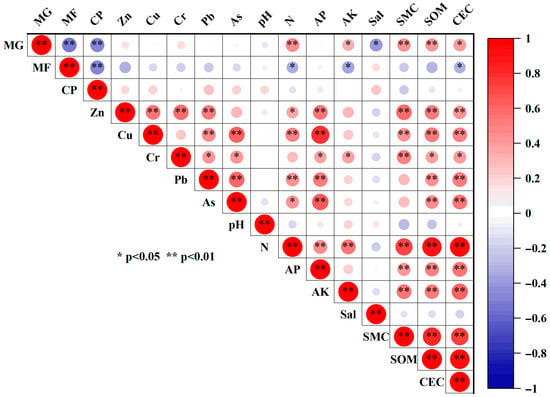

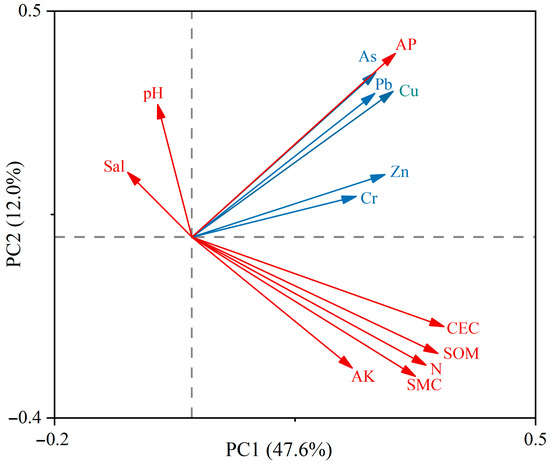

Zn and Cr were significantly positively correlated with sediment organic matter and cation exchange capacity (CEC), whereas As, Cu, and Pb were negatively correlated with pH and salinity. Pearson correlation analysis (Figure 10) further showed that all metals were highly positively correlated with soil P, organic matter, and CEC (p < 0.01). In conjunction with the PCA (Figure 11), Zn and Cr were closely associated with high organic matter and strong CEC, with variance contributions of 12.80% and 13.40%, respectively, indicating that Zn and Cr are more readily adsorbed and retained in sediments under organic-rich and high-CEC conditions. By contrast, As, Cu, and Pb were positively correlated with available phosphorus and exhibited loadings opposite to pH and salinity on the same principal component, with variance contributions of 16.50%, 8.62%, and 2.00%, respectively. This pattern suggests that higher pH and salinity may suppress the mobility and bioavailability of Cu, Pb, and As, whereas P-enriched conditions may enhance their adsorption and co-precipitation in sediments. Additionally, except for Cr, the concentrations of the other metals were significantly positively correlated with total nitrogen (p < 0.05), implying possible inputs from metal-bearing fertilizers or aquaculture wastes [33].

Figure 10.

Correlation between heavy metals and land use and other environmental factors in mangrove wetland. Note: MG, mangrove; MF, mudflat; CP, culture pond; AP, available phosphorus; AK, available potassium; Sal, salinity; SMC, soil moisture content; SOM, soil organic matter; CEC, cation exchange capacity. * indicates correlation is significant (p < 0.05); ** indicates correlation is very significant (p < 0.01).

Figure 11.

Principal component analysis (PCA) for the relationship between heavy metals and environmental factors. Blue arrows represent heavy metals, and red arrows represent environmental factors. AP, available phosphorus; AK, available potassium; Sal, salinity; SMC, soil moisture content; SOM, soil organic matter; CEC, cation exchange capacity.

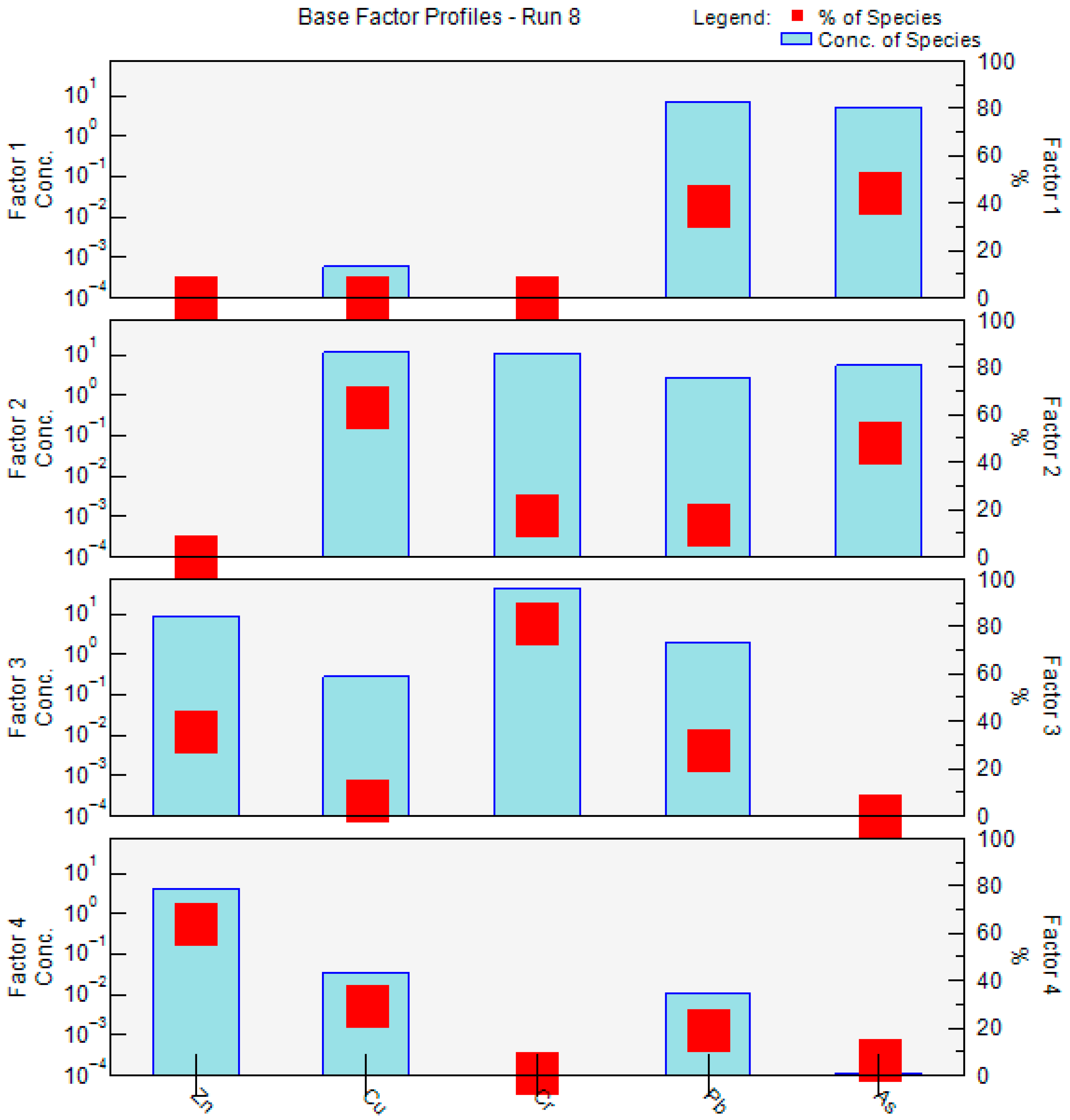

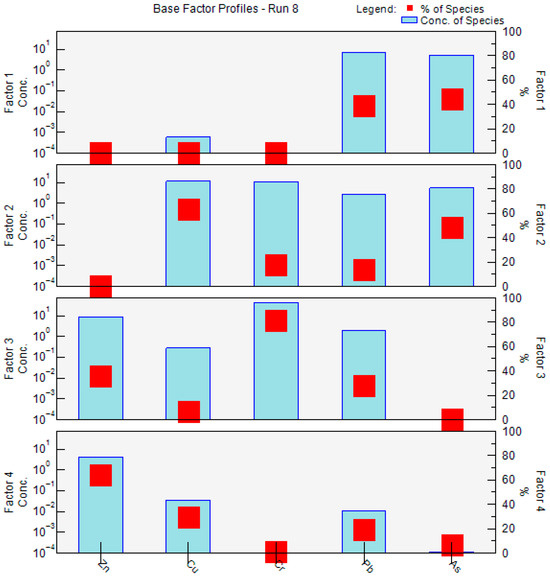

The PMF model was also applied to quantify the contributions of potential heavy-metal sources, revealing substantial differences in factor contributions across metals, which reflect the distinct emission characteristics of the underlying pollution sources. Figure 12 presents the concentration profiles of the four factors extracted by the PMF model. Pb and As were predominantly associated with Factor 1, with these two metals showing markedly higher contributions than the others, indicating strong source specificity. Factor 2 exhibited relatively high contributions to Cu, Cr, Pb, and As, with Cu reaching a contribution rate of 63.5%, suggesting a typical mixed-source pattern involving multiple metals. Factor 3 was overwhelmingly dominated by Cr, with a contribution rate of 81.3%, far exceeding that of other metals, implying a highly concentrated single-metal signature. Similarly, Factor 4 showed the greatest contribution to Zn, accounting for 64.2%, indicating the dominance of Zn in this factor. The distinct composition patterns of the four factors provide a robust basis for identifying pollution sources and attributing their relative contributions.

Figure 12.

Source profiles and source contributions of heavy metal from PMF.

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Land-Use-Driven Changes in Sediment Physicochemical Properties on Heavy-Metal Accumulation

Different degrees of heavy-metal accumulation were observed across various land-use types. Deng et al. [34] reported that land-use changes can significantly influence the spatial distribution of heavy metals in soils and are considered one of the key driving factors enhancing metal accumulation within mangrove ecosystems [3,35].

Our results show that, compared with other land-use types, culture pond sediments exhibited the highest levels of heavy metal contamination and the greatest potential ecological risk. PCA indicated that Zn and Cr had strong positive loadings with sediment organic matter, suggesting that their enrichment is closely associated with organic matter content. Aquaculture activities typically introduce substantial organic inputs, such as uneaten feed and fertilizer application, which increase sediment organic matter and consequently enhance the adsorption and complexation of metal ions. High molecular weight organic fractions can reduce the solubility of heavy metals through complexation and precipitation, promoting their retention in more stable binding forms [36]. This mechanism explains the pronounced metal accumulation observed in culture ponds. In contrast, mangrove wetlands host complex biogeochemical processes that can effectively mitigate exogenous metal inputs through filtration, co-precipitation, ion exchange, microbial decomposition, and uptake by mangrove plants [37,38].

In this study, the mudflat zone exhibited relatively low pH and salinity. Lower salinity implies reduced ionic strength, which diminishes competition from cations such as Na+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ for sorption sites and thereby favors the association of heavy metals with humic substances and other organic constituents [36]. However, under low pH conditions, H+ competes with metals for adsorption sites and can disrupt metal–organic complexes, while simultaneously promoting the dissolution of Fe/Mn oxides [39]. These processes weaken metal retention and increase their mobility [40,41]. In addition, the formation of humic acids during organic matter decomposition can induce local acidification [42], further enhancing the potential for metal remobilization. Consequently, although reduced salinity in the mudflat may to some extent facilitate metal adsorption, concurrent acidification and organic matter decomposition collectively diminish sediment metal retention. These findings indicate that different land-use types, by altering sediment physicochemical properties such as pH, salinity, and organic matter content, exert a significant influence on the speciation and transport behavior of heavy metals, ultimately shaping their ecological risk profiles.

4.2. Influencing Factors and Source of Heavy Metal Concentration for Mangrove Wetlands

Sediment pollution can result from both natural processes and human activities. Natural processes include geological weathering of rocks and atmospheric deposition, while human inputs such as aquaculture, agriculture, wastewater discharge, and shipping are considered significant sources of pollution [32,43]. In marine ecosystems, sediments can effectively accumulate heavy metals, making the identification of specific sources crucial for risk management [44].

In our study, HCA indicated that Zn and Cr share similar natural sources, as they are predominantly influenced by Factor 3 and Factor 4, respectively. On the other hand, Pb and As are more closely related to human activities, with both metals being largely influenced by Factor 1 and Factor 2. The strong correlation between Zn and Cr is attributed to their control by geological factors, suggesting that Factor 3 and Factor 4 are likely of natural origin. These two metals primarily originate from the weathering and erosion of parent rocks [45,46], particularly in the basalt regions of Hainan [47]. In contrast, Cu, Pb, and As are closely associated with anthropogenic sources. Cu pollution is typically linked to inputs from aquaculture, such as feed, disinfectants, and antifouling paints, as well as wastewater discharge from marine aquaculture [48]. This suggests that Factor 2 is likely linked to anthropogenic activities related to aquaculture. Pb contamination in coastal wetlands is often associated with agricultural fertilizer residues, aquaculture wastewater, and urban sewage discharge [43,49].

As frequently accumulates in estuarine and marine organisms [50]. In estuarine environments, iron oxides and oxyhydroxides, which are abundant and highly reactive, serve as the primary sorbents for As through the formation of inner-sphere surface complexes [51,52]. On MnO2 surfaces, As forms inner-sphere complexes where electrons are transferred from As(III) to Mn(IV), resulting in the oxidation of As(III) to As(V) and the reduction of Mn(IV) to Mn(II). Most As(V) are subsequently adsorbed onto MnO2 surfaces and may be released into the estuarine environment. In the ecological risk assessment, As was identified as the main risk factor in both culture pond and mangrove sediments. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that aquaculture practices, through the use of feed additives, lime disinfectants, and wastewater discharge, contribute to elevated As concentrations in sediments [20,53]. He et al. further demonstrated that aquaculture sediments release considerable amounts of As across the sediment–water interface [54], suggesting that Factor 1 is primarily influenced by aquaculture activities, with additional contributions from agricultural runoff and domestic wastewater inputs, forming a mixed anthropogenic source.

4.3. Management Strategies for Heavy-Metal Pollution in Mangrove Forests

The overall ecological risk in the study area is relatively low; however, the significant enrichment of As in culture ponds and the higher RI indicate notable potential risks in localized areas. An investigation of mangrove wetlands in the northern part of Hainan Island also revealed significant spatial variability in the concentrations of heavy metals such as As, Cr, and Zn in sediments [55], with concentrations at most sites exceeding inland background levels. Combined with the differences in metal sources between mudflats and culture ponds revealed by HCA, this further highlights the critical role of external inputs and land-use changes in metal accumulation, thus emphasizing the necessity of regional monitoring [56]. Similarly, sediments in the Guangxi Shankou Mangrove Nature Reserve are generally at low pollution levels, but the potential ecological risks at most sites are moderate. Based on these findings, researchers have recommended limiting large-scale coastal aquaculture and industrial expansion [57]. In Zhanjiang Bay, mangrove surface and core sediments also exhibit moderate to severe enrichment of metals such as Cu and Zn, influenced by port trade and industrial emissions, with the overall RI at a moderate level [58]. In comparison with these regional studies, the As enrichment and ecological risk in culture ponds of Bamen Bay have reached or exceeded levels observed in some neighboring bays, indicating that aquaculture remains a key pollution source that needs to be prioritized in the region’s management efforts.

In addition to aquaculture activities, several mangrove reserves in Hainan have recently developed eco-tourism. Studies have indicated that without proper management, tourism-related activities such as vessel traffic, shoreline infrastructure construction, and visitor activities may alter sedimentary environments and increase pollutant inputs [59]. The rapid expansion of eco-tourism in the Bamen Bay mangrove area further suggests that such disturbances are a tangible concern in the region. Future assessments of heavy metal pollution and long-term changes in its sediments should incorporate the intensity of tourism development into a comprehensive analytical framework to differentiate metal responses under various disturbance scenarios. This aligns with recent research focusing on the ecological resilience of Chinese mangroves under multiple pressures [60].

5. Conclusions

This study, using the Bamen Bay Mangrove Reserve in Hainan Island as a case study, investigates the distribution and accumulation differences in heavy metals in mangrove sediments under different land-use types. The results indicate that heavy metal pollution is most severe in the sediments of culture ponds, where ecological risk is also highest. This is likely closely related to the use of agricultural chemicals in aquaculture activities. As has a high ecological risk and shows a potential shared source with Pb. Zn and Cr are primarily influenced by organic matter content and cation exchange capacity, suggesting similar sources. Land-use types significantly affect the migration, accumulation, and ecological risks of heavy metals by modulating the physicochemical properties of sediments, such as pH, salinity, organic matter, and cation exchange capacity. The findings of this study provide scientific evidence for pollution control and ecological restoration in mangrove wetlands, as well as offer a valuable reference for the formulation of wetland conservation strategies. Future research should further investigate the source apportionment and migration mechanisms of key heavy metals to optimize management strategies and support long-term monitoring.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.; methodology, R.Y.; software, Y.H.; validation, F.L.; formal analysis, J.L.; investigation, Y.H.; resources, B.Z.; data curation, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, X.Z.; visualization, X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Science and Technology Innovation Foundation of Survey Center of Comprehensive Natural Resources (KC20250020), Geological Survey Project of China Geological Survey (DD20240100810), Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (424MS116), National Natural Science Foundation of China (42261064).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the reviewers for their valuable feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, P.; Li, X.; Bai, J.; Meng, Y.; Diao, X.; Pan, K.; Zhu, X.; Lin, G. Effects of land use on the heavy metal pollution in mangrove sediments: Study on a whole island scale in Hainan, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 824, 153856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Chen, S.; Long, R.; Ma, B.; Chang, Y.; Mao, C. Distribution of Heavy Metals in Surface Sediments of a Tropical Mangrove Wetlands in Hainan, China, and Their Biological Effectiveness. Minerals 2023, 13, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, K.; Huang, X.; Hu, J.; Li, C.; Yang, X.; Arndt, S.K. Land use change impacts on heavy metal sedimentation in mangrove wetlands—A case study in Dongzhai Harbor of Hainan, China. Wetlands 2014, 34, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alongi, D.M. Mangrove forests: Resilience, protection from tsunamis, and responses to global climate change. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2008, 76, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alongi, D.M. Carbon cycling and storage in mangrove forests. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2014, 6, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, R.; Deobagkar, D.; Zinjarde, S. Metals in mangrove ecosystems and associated biota: A global perspective. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 153, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Chai, M.; Qiu, G.Y. Distribution, fraction, and ecological assessment of heavy metals in sediment-plant system in mangrove forest, South China Sea. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrooz, R.D.; Khammar, S.; Poma, G.; Rajaei, F. Occurrence and patterns of metals in mangrove forests from the Oman Sea, Iran. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 198, 115866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, L.; Chunxiang, L.; Jin, L.; HU, W.; Danyi, W.; Yongze, X.; Xiang, S. Heavy Metals Fate in Mangrove Wetlands: Integrated Insights into Sediment-Microbe-Plant Interactions and Fraction Control. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 499, 140191. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, N.F.; Wong, Y.S. Spatial variation of heavy metals in surface sediments of Hong Kong mangrove swamps. Environ. Pollut. 2000, 110, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, S.R.; Santos, I.R.; Brown, D.R.; Sanders, L.M.; van Santen, M.L.; Sanders, C.J. Mangrove sediments reveal records of development during the previous century (Coffs Creek estuary, Australia). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 122, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ram, S.; Aich, A.; Sengupta, P.; Chakraborty, A.; Sudarshan, M. Assessment of trace metal contamination of wetland sediments from eastern and western coastal region of India dominated with mangrove forest. Chemosphere 2018, 211, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, C.; Lallier-Vergès, E.; Baltzer, F.; Albéric, P.; Cossa, D.; Baillif, P. Heavy metals distribution in mangrove sediments along the mobile coastline of French Guiana. Mar. Chem. 2006, 98, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uluturhan, E.; Kucuksezgin, F. Heavy metal contaminants in Red Pandora (Pagellus erythrinus) tissues from the eastern Aegean Sea, Turkey. Water Res. 2007, 41, 1185–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.; Pryor, R.; Wilking, L. Fate and effects of anthropogenic chemicals in mangrove ecosystems: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 2328–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Lin, C.; Qiu, P.; Song, Y.; Yang, W.; Xu, G.; Feng, X.; Yang, Q.; Yang, X.; Niu, A. Tungsten-and cobalt-dominated heavy metal contamination of mangrove sediments in Shenzhen, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 100, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacFarlane, G.; Burchett, M. Toxicity, growth and accumulation relationships of copper, lead and zinc in the grey mangrove Avicennia marina (Forsk.) Vierh. Mar. Environ. Res. 2002, 54, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cen, D.; Huang, D.; Li, X.; Xu, J.; Fu, S.; Cai, R.; Wu, X.; Tang, M.; Sun, Y. Detection and analysis of 12 heavy metals in blood and hair sample from a general population of Pearl River Delta area. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 70, 1663–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.; Ding, H.; Zan, Q.; Li, R. Spatial variation and ecological risk assessment of heavy metals in mangrove sediments across China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 143, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cui, H.; Guo, Y.; Li, P.; Han, J.; Li, W. Aquaculture exacerbates the accumulation and ecological risk of heavy metal from anthropogenic and natural sources, a case study in Hung-tse Lake, China. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; You, W.; Hu, H.; Hong, W.; Liao, X.; Xiao, S.; Wang, R.; Cai, J.; Fan, X.; Tan, Y. Spatial distribution of heavy metals (Cu, Pb, Zn, and Cd) in sediments of a coastal wetlands in eastern Fujian, China. J. For. Res. 2015, 26, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J. Composition and degradation of lipid biomarkers in mangrove forest sediments of Hainan Island, China. J. Trop. Oceanogr. 2011, 30, 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Yu, Y.; Wu, G.; Ma, M. Characteristics of surface water quality and stable isotopes in Bamen Bay watershed, Hainan Province, China. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Zhao, Z.; Ji, Y.; Wang, J. The Spatial Distribution and Pollution Assessment of Heavy Metals in the Surface Sediments of Bamenwan mangrove wetland, Hainan Island. J. Hainan Norm. Univ. Nat. Sci. 2015, 28, 432–437. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Guo, J.; Wu, G.; Lü, L.; Li, W. Mangrove Landscape Changes Process and Land Use and Coverage Change in Its Surrounding Area: A Case Study of Qinglangang Bay in Hainan Province. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2013, 49, 169–175. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Kang, X.; Li, X.; Li, Q.; Song, J.; Jiao, N.; Zhang, Y. Heavy metals in surface sediments along the Weihai coast, China: Distribution, sources and contamination assessment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 115, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, D.L.; Wilson, J.G.; Harris, C.; Jeffrey, D. Problems in the assessment of heavy-metal levels in estuaries and the formation of a pollution index. Helgoländer Meeresunters. 1980, 33, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, K.; Gong, J.; Gao, J.; Wang, Z.; Cai, Y.; Zhao, K.; Hu, S.; Fu, Y. Differentiating environmental scenarios to establish geochemical baseline values for heavy metals in soil: A case study of Hainan Island, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 898, 165634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanson, L. An ecological risk index for aquatic pollution control. A sedimentological approach. Water Res. 1980, 14, 975–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, G. Index of geoaccumulation in sediments of the Rhine River. GeoJournal 1969, 2, 108–118. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, L.; Xie, Z.; Du, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, C.; Long, T. Contaminations of Heavy Metals in Surface Soils of Various Lands and Their Health Risks in Tianjin Qilihai Ancient Lagoon Wetlands, China. Wetl. Sci. 2016, 14, 700–709. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Ren, F.; Xiong, X.; Gao, H.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W.; Leng, P.; Li, Z.; Bai, Y. Spatial distribution and contamination assessment of heavy metal pollution of sediments in coastal reclamation areas: A case study in Shenzhen Bay, China. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Peng, R.; Yang, Y.; He, L.; Wang, W.; Zheng, T.; Lin, G. Mariculture pond influence on mangrove areas in south China: Significantly larger nitrogen and phosphorus loadings from sediment wash-out than from tidal water exchange. Aquaculture 2014, 426, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, A.; Wang, L.; Chen, F.; Li, Z.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y. Soil aggregate-associated heavy metals subjected to different types of land use in subtropical China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2018, 16, e00465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branoff, B.L. Quantifying the influence of urban land use on mangrove biology and ecology: A meta-analysis. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2017, 26, 1339–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Laing, G.; Rinklebe, J.; Vandecasteele, B.; Meers, E.; Tack, F.M. Trace metal behaviour in estuarine and riverine floodplain soils and sediments: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 3972–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, N.F.; Wong, Y.-S. Accumulation and distribution of heavy metals in a simulated mangrove system treated with sewage. Hydrobiologia 1997, 352, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, S.K.; Chowdhury, A. Effects of anthropogenic pollution on mangrove biodiversity: A review. J. Environ. Prot. 2013, 4, 1428–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yu, Z.-G.; Zeng, G.-M.; Jiang, M.; Yang, Z.-Z.; Cui, F.; Zhu, M.-Y.; Shen, L.-Q.; Hu, L. Effects of sediment geochemical properties on heavy metal bioavailability. Environ. Int. 2014, 73, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guven, D.E.; Akinci, G. Effect of sediment size on bioleaching of heavy metals from contaminated sediments of Izmir Inner Bay. J. Environ. Sci. 2013, 25, 1784–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belzile, N.; Chen, Y.-W.; Gunn, J.M.; Dixit, S.S. Sediment trace metal profiles in lakes of Killarney Park, Canada: From regional to continental influence. Environ. Pollut. 2004, 130, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobi, E.; Dilipan, E.; Thangaradjou, T.; Sivakumar, K.; Kannan, L. Geochemical and geo-statistical assessment of heavy metal concentration in the sediments of different coastal ecosystems of Andaman Islands, India. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2010, 87, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Duan, Z.; Liu, G.; Kalla, P.; Scheidt, D.; Cai, Y. Evaluation of the possible sources and controlling factors of toxic metals/metalloids in the Florida Everglades and their potential risk of exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 9714–9723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.-G.; Lin, Q.; Yu, Z.-L.; Wang, X.-N.; Ke, C.-L.; Ning, J.-J. Speciation and risk of heavy metals in sediments and human health implications of heavy metals in edible nekton in Beibu Gulf, China: A case study of Qinzhou Bay. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 101, 852–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanesch, M.; Scholger, R.; Dekkers, M.J. The application of fuzzy c-means cluster analysis and non-linear mapping to a soil data set for the detection of polluted sites. Phys. Chem. Earth Part A Solid Earth Geod. 2001, 26, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micó, C.; Recatalá, L.; Peris, M.; Sánchez, J. Assessing heavy metal sources in agricultural soils of an European Mediterranean area by multivariate analysis. Chemosphere 2006, 65, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Bao, K.; Yan, Y.; Neupane, B.; Gao, C. Spatial distribution of potentially harmful trace elements and ecological risk assessment in Zhanjiang mangrove wetland, South China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 182, 114033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutherland, T.; Petersen, S.; Levings, C.; Martin, A. Distinguishing between natural and aquaculture-derived sediment concentrations of heavy metals in the Broughton Archipelago, British Columbia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2007, 54, 1451–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuana, R.A.; Okieimen, F.E. Heavy metals in contaminated soils: A review of sources, chemistry, risks and best available strategies for remediation. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2011, 2011, 402647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavhane, S.; Sapkale, J.; Susware, N.; Sapkale, S. Impact of heavy metals in riverine and estuarine environment: A review. Res. J. Chem. Environ. 2021, 25, 226–233. [Google Scholar]

- Manceau, A. The mechanism of anion adsorption on iron oxides: Evidence for the bonding of arsenate tetrahedra on free Fe (O, OH) 6 edges. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1995, 59, 3647–3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, D.M.; Randall, S.R. Surface complexation of arsenic (V) to iron (III)(hydr) oxides: Structural mechanism from ab initio molecular geometries and EXAFS spectroscopy. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2003, 67, 4223–4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Chen, K.-C.; Li, K.-B.; Nie, X.-P.; Wu, S.C.; Wong, C.K.-C.; Wong, M.-H. Arsenic contamination in the freshwater fish ponds of Pearl River Delta: Bioaccumulation and health risk assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 4484–4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Yan, W.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Li, Q.; Yu, Z.; Wu, T.; Luan, C.; Shao, Y. Arsenic distribution characteristics and release mechanisms in aquaculture lake sediments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 476, 135141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, R.; Li, X.; Wang, J. Bioaccumulation characteristics of heavy metal in intertidal zone sediments from northern Hainan Island. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2014, 23, 842–846. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Saenger, P.; McConchie, D. Heavy metals in mangroves: Methodology, monitoring and management. Envis For. Bull. 2004, 4, 52–62. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Z.; Zhu, G.; Xu, M.; Zhang, H.; Yi, W.; Jiang, Y.; Liang, M.; Wang, Z. Risk assessment of heavy metals in a typical mangrove ecosystem—A case study of Shankou Mangrove National Natural Reserve, southern China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 178, 113642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Luo, S.; Deng, S.; Huang, R.; Chen, B.; Deng, Z. Heavy metal pollution status and deposition history of mangrove sediments in Zhanjiang Bay, China. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 989584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q. Analysis of the Development Path of Mangrove Ecotourism. J. Humanit. Arts Soc. Sci. 2023, 7, 2256–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.U.; Han, J.-C.; Zhou, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, Y.; Farman, A.; Zhao, X.; Riaz, L.; Yasin, G.; Ullah, S. Eco-resilience of China’s mangrove wetlands: The impact of heavy metal pollution and dynamics. Environ. Res. 2025, 277, 121552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).