Analyzing Added Wave and Superstructure Resistance Based on North Pacific Ocean Sea State

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Material

2.1. Ship Characteristics

| Parameters | Values | Unit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ship-Scale | Model-Scale | ||

| Displacement tonnage | 53,330 | 1.645 | t (ship)–kg (model) |

| Displacement volume | 52,030 | 1.649 | m3 |

| Length on waterline (Lwl) | 232.5 | 7.357 | m |

| Length between perpendiculars (Lbp) | 230.0 | 7.279 | m |

| Breadth (B) | 32.2 | 1.019 | m |

| Depth (D) | 19.0 | 0.601 | m |

| Draft amidships (T) | 10.8 | 0.342 | m |

| Wetted area (Aw) (rudder incl.) | 9645 | 9.553 | m2 |

| Froude number range | 0.108; 0.152; 0.195; 0.227; 0.260; 0.282 | – | |

| Speed range | 9.97; 14.04; 18.01; 20.96; 24.01; 26.04 | 0.9126; 1.2844; 1.6478; 1.9182; 2.1970; 2.3829 | knots; m/s |

2.2. Dimensionless Parameters

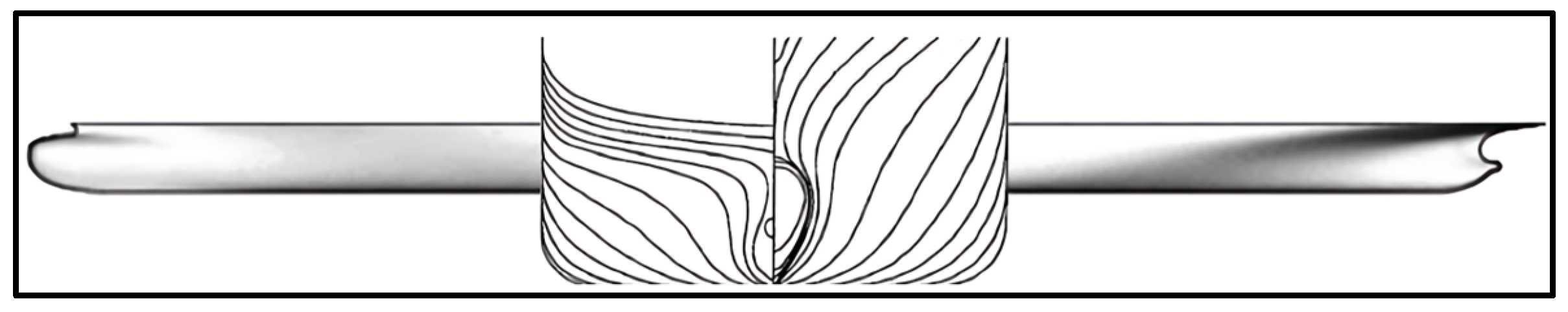

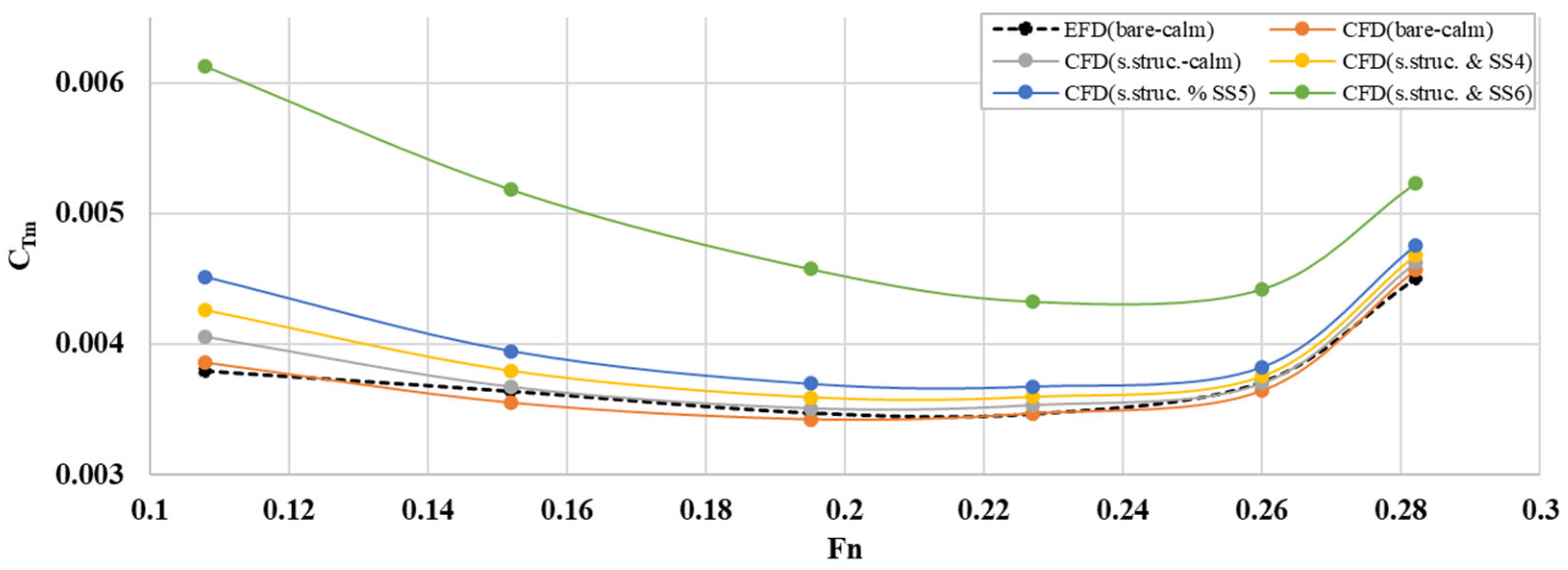

2.3. Calm Water Resistance

2.4. Added Wave Resistance

2.5. Added Air Resistance

2.6. Environmental Factors and Their Effects

2.7. Route and Environmental Conditions

3. Methodology

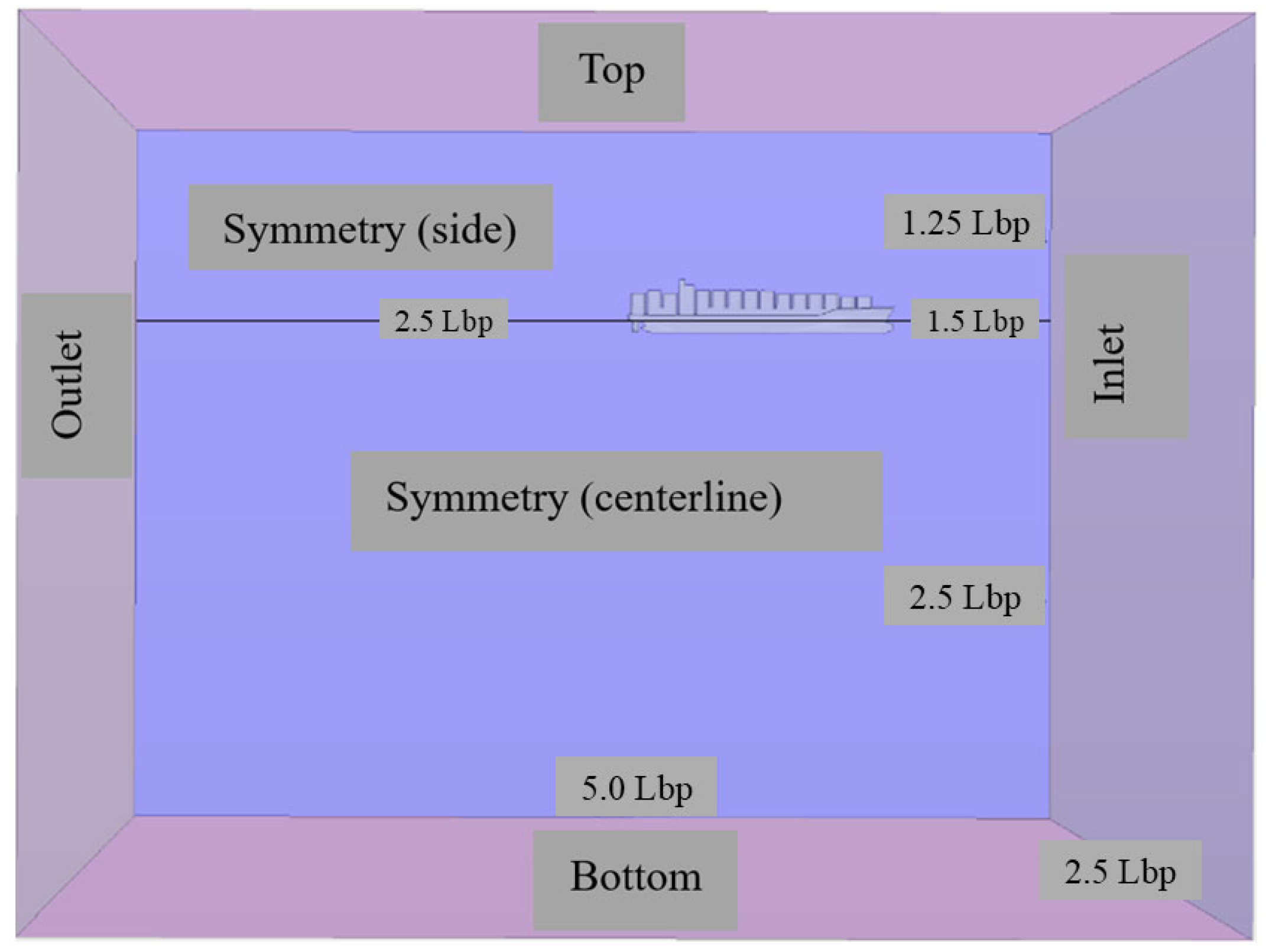

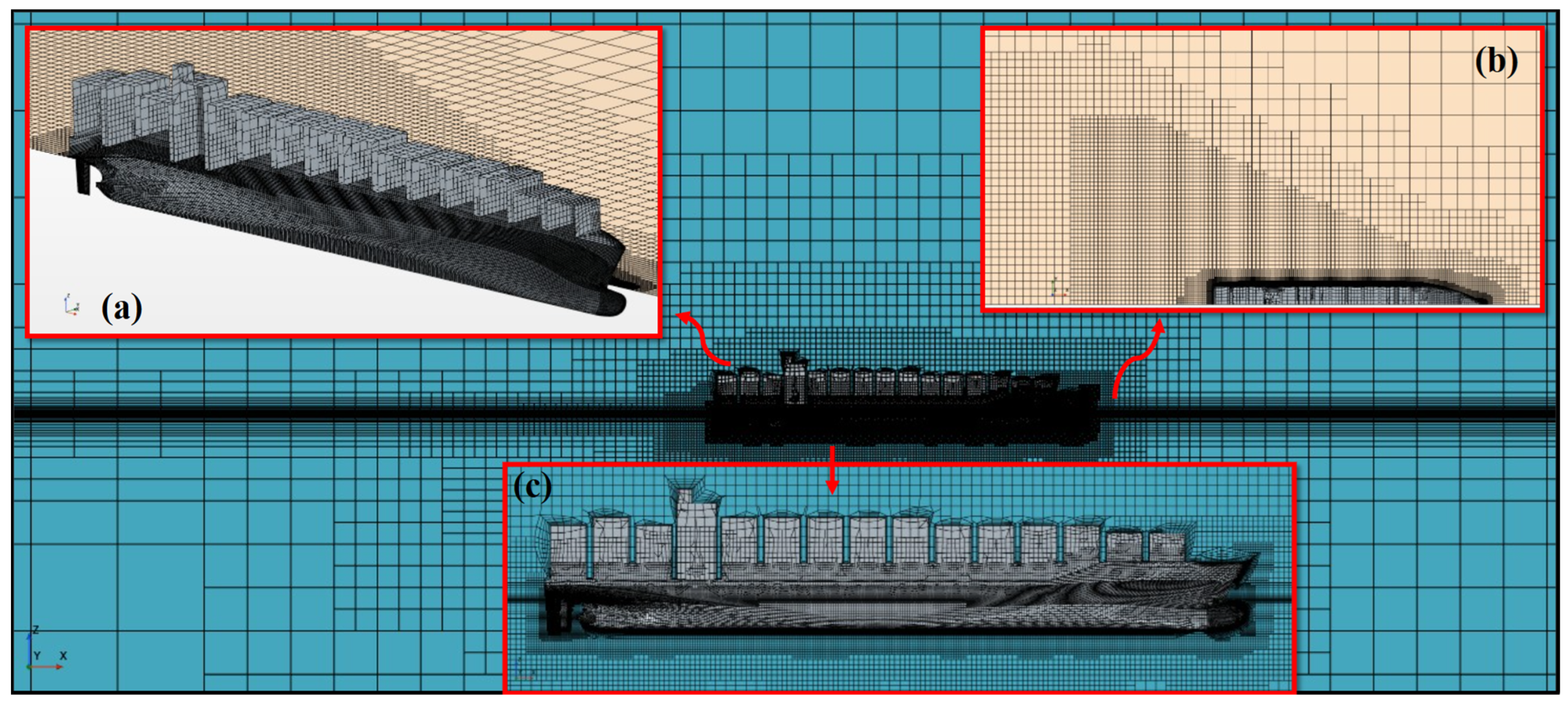

3.1. Numerical Analysis Parameters

- Determining the size of the control volume;

- Defining the fluid properties;

- Defining initial and boundary conditions;

- Defining the ship’s allowed degrees of freedom, and;

- Defining mesh characteristics.

- Unsteady Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes equations;

- Multiphase flow condition;

- Volume of Fluid methodology with HRIC (High-Resolution Interface Capturing) algorithm to simulate free surface and multiphase interactions;

- Segregated flow solver for velocity and pressure calculations;

- Turbulent flow modelling with Realizable k-epsilon two-layer wall treatment algorithm;

- Dynamic Fluid Body Interaction (DFBI) motion with activated heave and pitch motions for ship geometry;

- Ship release time 1.0 s and ramp time 5.0 s to mitigate errors during initial iterations;

- Total simulation time 250 s.

3.2. Verification Study

- for : Monotonic convergence;

- for : Oscillatory convergence;

- for : Divergence.

3.3. Benchmarking Air Resistance Against Standardized Methods

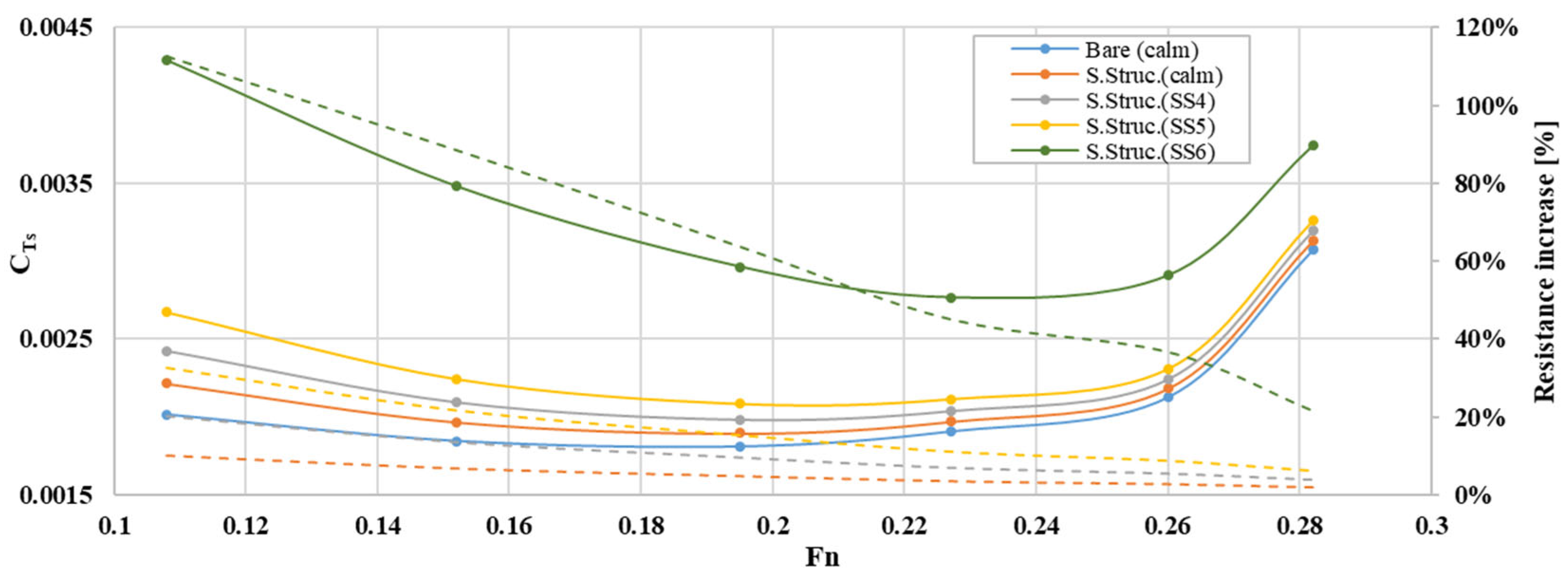

4. Results

5. Discussions and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Roman Symbols | Definition | Unit |

| Aw | Wetted area | m2 |

| AVX | Transverse projected area of the windage surface | m2 |

| B | Breadth (of ship) | m |

| Bwl | Width of the hull at waterline | m |

| CAA | Air resistance coefficient | - |

| CDA | Air drag coefficient above the waterline | - |

| CDAX | Non-dimensional air load coefficient | - |

| CF | Frictional resistance coefficient | - |

| CT | Total resistance coefficient | - |

| CTM | Total resistance coefficient (model-scale) | - |

| CV | Viscous resistance coefficient | - |

| CW | Wave-making resistance coefficient | - |

| D | Depth (of ship) | m |

| fext | Extrapolated solution (for uncertainty analysis) | - |

| f1, f2, f3 | Solution results (fine, medium, coarse grid) | - |

| Fn | Froude number | - |

| g | Acceleration due to gravity | m/s2 |

| H1/3 | Mean significant wave height | m |

| k | Form factor | - |

| L | Characteristic length | m |

| Lbp | Length between perpendiculars | m |

| Lm | Calculation length of the model | m |

| Ls | Calculation length of the ship | m |

| Lwl | Length on waterline | m |

| p | Order of accuracy (for uncertainty analysis) | - |

| R | Convergence ratio (for uncertainty analysis) | - |

| r | Refinement ratio (for uncertainty analysis) | - |

| RAAX | Air load force (added air resistance) | N |

| RAW | Added resistance due to waves | N |

| Re | Reynolds number | - |

| RT | Total resistance | N |

| RT,air | Average drag force with superstructure | N |

| RT,calm | Calm water resistance | N |

| RT,wave | Average drag force in waves | N |

| RTM | Total resistance (Model scale) | N |

| S | Wetted surface area | m2 |

| SS | Wetted surface area of ship hull | m2 |

| T | Draft amidships | m |

| Te | Encounter wave period | s |

| Tm | Modal (most probable) wave period | s |

| V | Speed of ship or model | m/s |

| VAA | Relative air velocity | m/s |

| Vm | Model ship speed | m/s |

| Vs | Full-scale ship speed | knot |

| y+ | Dimensionless wall distance | - |

| Greek Symbols | Definition | Unit |

| α | Wave direction angle | ° |

| ϵ21 | Change between medium and fine solution | - |

| ϵ32 | Change between coarse and medium solution | - |

| ζa | Harmonic amplitude of incident wave | m |

| λ | Wavelength | m |

| μ | Dynamic viscosity of fluid | Pa·s |

| Density of fluid (water) | kg/m3 | |

| Density of air flow | kg/m3 | |

| Density of sea water | kg/m3 | |

| Added wave resistance coefficient | - |

References

- Nguyen, H.P.; Hoang, A.T.; Nizetic, S.; Nguyen, X.P.; Le, A.T.; Luong, C.N.; Chu, V.D.; Pham, V.V. The Electric Propulsion System as a Green Solution for Management Strategy of CO2 Emission in Ocean Shipping: A Comprehensive Review. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2020, 31, e12580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMO Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC 76), 10 to 17 June 2021 (Remote Session). Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/MeetingSummaries/Pages/MEPC76meetingsummary.aspx (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Kaya, A.Y.; Erginer, K.E. An Analysis of Decision-Making Process of Shipowners for Implementing Energy Efficiency Measures on Existing Ships: The Case of Turkish Maritime Industry. Ocean Eng. 2021, 241, 110001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.; Park, S.; Koo, B.Y. Effect of Wave Periods on Added Resistance and Motions of a Ship in Head Sea Simulations. Ocean Eng. 2017, 137, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grlj, C.G.; Degiuli, N.; Tuković, Ž.; Farkas, A.; Martić, I. The Effect of Loading Conditions and Ship Speed on the Wind and Air Resistance of a Containership. Ocean Eng. 2023, 273, 113991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepowski, T.; Drozd, A. Measurement-Based Relationships between Container Ship Operating Parameters and Fuel Consumption. Appl. Energy 2023, 347, 121315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, R.F.; Haglind, F.; Larsen, U. Design and Modeling of an Advanced Marine Machinery System Including Waste Heat Recovery and Removal of Sulphur Oxides. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 85, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Moctar, O.; Lantermann, U.; Shigunov, V.; Schellin, T.E. Experimental and Numerical Investigations of Effects of Ship Superstructures on Wind-Induced Loads for Benchmarking. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 045124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, N.R.; Seddiek, I.S. Enhancing Energy Efficiency for New Generations of Containerized Shipping. Ocean Eng. 2020, 215, 107887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgili, L. Determination of the Weights of External Conditions for Ship Resistance. Ocean Eng. 2023, 276, 114141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujimoto, M.; Yasukawa, H.; Yamamoto, K.; Lee, T. Il Validation of Added Resistance in Waves by Tank Tests and Sea Trial Data. Ship Technol. Res. 2023, 70, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himaya, A.N.; Sano, M. Course-Keeping Performance of a Container Ship with Various Draft and Trim Conditions under Wind Disturbance. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahab, H.S.; Wang, S.; Parunov, J.; Guedes Soares, C. A New Model Uncertainty Measure of Wave-Induced Motions and Loads on a Container Ship with Forward Speed. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, C.; Paik, K.J.; Kim, H.; Chun, J. A Numerical Study of Added Resistance Performance and Hydrodynamics of KCS Hull in Oblique Regular Waves and Estimation of Resistance in Short-Crested Irregular Waves through Spectral Method. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2024, 16, 100563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Papanikolaou, A.; Zaraphonitis, G. Prediction of Added Resistance of Ships in Waves. Ocean Eng. 2011, 38, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITTC 7.5-04-01-01.1; Full Scale Measurements Speed and Power Trials Preparation and Conduct of Speed/Power Trials. ITTC: Zürich, Switzerland, 2005.

- ISO 15016; Ships and marine technology—Specifications for the Assessment of Speed and Power Performance by Analysis of Speed Trial Data. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025.

- Wang, J.; Bielicki, S.; Kluwe, F.; Orihara, H.; Xin, G.; Kume, K.; Oh, S.; Liu, S.; Feng, P. Validation Study on a New Semi-Empirical Method for the Prediction of Added Resistance in Waves of Arbitrary Heading in Analyzing Ship Speed Trial Results. Ocean Eng. 2021, 240, 109959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, H.; Rahaman, M.M.; Akimoto, H.; Islam, M.R. Calm Water Resistance Prediction of a Container Ship Using Reynolds Averaged Navier-Stokes Based Solver. Procedia Eng. 2017, 194, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, J.; Park, J.C. Comparative Study of Air Resistance with and without a Superstructure on a Container Ship Using Numerical Simulation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITTC. ITTC—Recommended Procedures and Guidelines Resistance Test. 2021. Available online: https://www.ittc.info/media/9595/75-02-02-01.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Holtrop, J.; Mennen, G.G.J. An Approximate Power Prediction Method. Int. Shipbuild. Prog. 1982, 29, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITTC. ITTC—Recommended Procedures and Guidelines 1978 ITTC Performance Prediction Method. 2017. Available online: https://www.ittc.info/media/8017/75-02-03-014.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Söding, H.; Shigunov, V.; Schellin, T.E.; El Moctar, O. A Rankine Panel Method for Added Resistance of Ships in Waves. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2014, 136, 031601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martić, I.; Degiuli, N.; Farkas, A.; Gospić, I. Evaluation of the Effect of Container Ship Characteristics on Added Resistance in Waves. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Paik, K.J.; Lee, J.H. A Study on Ship Performance in Waves Using a RANS Solver, Part 2: Comparison of Added Resistance Performance in Various Regular and Irregular Waves. Ocean Eng. 2022, 263, 112174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Hizir, O.; Turan, O.; Day, S.; Incecik, A. Estimation of Added Resistance and Ship Speed Loss in a Seaway. Ocean Eng. 2017, 141, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepowski, T. Utilizing Artificial Neural Network Ensembles for Ship Design Optimization to Reduce Added Wave Resistance and CO2 Emissions. Energies 2024, 17, 5326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Lee, P.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Lee, H.; Lee, Y. Study on the Estimation Method of Wind Resistance Considering Self-Induced Wind by Ship Advance Speed. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Papanikolaou, A. Improvement of the Prediction of the Added Resistance in Waves of Ships with Extreme Main Dimensional Ratios through Numerical Experiments. Ocean Eng. 2023, 273, 113963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Papanikolaou, A. Fast Approach to the Estimation of the Added Resistance of Ships in Head Waves. Ocean Eng. 2016, 112, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, T. A New Estimation Method of Wind Forces and Moments Acting on Ships on the Basis of Physical Components Models. J. Japan Soc. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2005, 2, 243–255. [Google Scholar]

- Blendermann, W. Parameter Identification of Wind Loads on Ships. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 1994, 51, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITTC. ITTC—Recommended Procedures and Guidelines Guideline on the CFD-Based Determination of Wind Resistance Coefficients. 2024. Available online: https://www.ittc.info/media/11962/75-03-02-05.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Prpić-Oršić, J.; Vettor, R.; Faltinsen, O.M.; Guedes Soares, C. The Influence of Route Choice and Operating Conditions on Fuel Consumption and CO2 Emission of Ships. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2016, 21, 434–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentin, M.; Zastrau, D.; Schlaak, M.; Freye, D.; Elsner, R.; Kotzur, S. A New Routing Optimization Tool-Influence of Wind and Waves on Fuel Consumption of Ships with and without Wind Assisted Ship Propulsion Systems. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 14, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD Review of Maritime Report 2021. 2021. Available online: https://unctad.org/publication/review-maritime-transport-2021 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Marinetraffic MarineTraffic: Global Ship Tracking Intelligence. Available online: https://www.marinetraffic.com/en/ais/home/centerx:-164.9/centery:42.8/zoom4 (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Bales, S.L. Designing Ships to the Natural Environment. Nav. Eng. J. 1983, 95, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.T.; Bales, S.L. Standardized Wind and Wave Environments for North Pacific Ocean Areas. 1985. Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA159393.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Durante, D.; Broglia, R.; Diez, M.; Olivieri, A.; Campana, E.F.; Stern, F. Accurate Experimental Benchmark Study of a Catamaran in Regular and Irregular Head Waves Including Uncertainty Quantification. Ocean Eng. 2020, 195, 106685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Hu, Q.; Hu, S.; Su, J.; Xu, J.; Wei, J.; Huang, G. Numerical Analysis of Full-Scale Ship Self-Propulsion Performance with Direct Comparison to Statistical Sea Trail Results. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molland, A.F.; Turnock, S.R.; Hudson, D.A. Ship Resistance and Propulsion: Practical Estimation of Ship Propulsive Power, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; Volume 3, ISBN 9781107142060. [Google Scholar]

- Terziev, M.; Tezdogan, T.; Incecik, A. A Geosim Analysis of Ship Resistance Decomposition and Scale Effects with the Aid of CFD. Appl. Ocean Res. 2019, 92, 101930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S. Modeling Mean Relation between Peak Period and Energy Period of Ocean Surface Wave Systems. Ocean Eng. 2021, 228, 108937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMO Revised Guidance To The Master For Avoiding Dangerous Situations In Adverse Weather And Sea Conditions. 2007. Available online: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/OurWork/Safety/Documents/Stability/MSC.1-CIRC.1228.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Wackers, J.; Deng, G.; Guilmineau, E.; Leroyer, A.; Queutey, P.; Visonneau, M.; Palmieri, A.; Liverani, A. Can Adaptive Grid Refinement Produce Grid-Independent Solutions for Incompressible Flows? J. Comput. Phys. 2017, 344, 364–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITTC. ITTC—Recommended Procedures and Guidelines Uncertainty Analysis in CFD Verification and Validation Methodology and Procedures. Available online: https://www.ittc.info/media/9765/75-03-01-01.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Celik, I.B.; Ghia, U.; Roache, P.J.; Freitas, C.J.; Coleman, H.; Raad, P.E. Procedure for Estimation and Reporting of Uncertainty Due to Discretization in CFD Applications. J. Fluids Eng. ASME 2008, 130, 078001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göksu, B.; Garad, S.; Pandini, S.; Sirolla, E.; Palin, R.; Townsend, N.; Tezdogan, T. Impact of Leeway and Rudder Angles on Ship Resistance: A Numerical Planar Motion Mechanism Approach. Ocean Eng. 2025, 338, 121952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, H.O.; Lützen, M. Prediction of Resistance and Propulsion Power of Ships; University of Southern Denmark: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shigunov, V.; el Moctar, O.; Papanikolaou, A.; Potthoff, R.; Liu, S. International Benchmark Study on Numerical Simulation Methods for Prediction of Manoeuvrability of Ships in Waves. Ocean Eng. 2018, 165, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sea State | Mean H1/3 [m] (Model Ship) | [s] (Model Ship) |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | 0.0595 | 1.5655 |

| 5 | 0.1029 | 1.7256 |

| 6 | 0.1582 | 2.4549 |

| Vm [m/s] | Fn | Sea State 4 | Sea State 5 | Sea State 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [s] | ||||

| 0.9126 | 0.108 | 1.14 | 1.29 | 1.98 |

| 1.2844 | 0.152 | 1.02 | 1.16 | 1.83 |

| 1.6478 | 0.195 | 0.93 | 1.07 | 1.71 |

| 1.9182 | 0.227 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 1.63 |

| 2.1970 | 0.260 | 0.82 | 0.95 | 1.55 |

| 2.3829 | 0.282 | 0.79 | 0.91 | 1.51 |

| Features | Values |

|---|---|

| Base mesh size | 0.1125 m |

| Target mesh size (for fluid domain) | 0.05625 m |

| Target mesh size (for ship hull) | 0.028125 m |

| Minimum mesh size (for all surfaces) | 0.00703125 m |

| Maximum mesh size (for outer surfaces) | 1.8 m |

| Mesh surface growth rate | 1.3 |

| Boundary layer thickness on ship hull/superstructure | 0.0987 m/0.175 m |

| Boundary layer quantity on ship hull/superstructure | 20/6 |

| Boundary layer growth rate on ship hull/superstructure | 1.13/1.23 |

| Meshing model | Trimmed cell mesher |

| Vm [m/s] | Fn | Re (×107) | RTm (EFD) [N] | CTm (EFD) | RTm (CFD) [N] | CTm (CFD) | Error [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.913 | 0.108 | 0.75 | 15.064 | 0.003796 | 15.30 | 0.003856 | 1.57 |

| 1.284 | 0.152 | 1.06 | 28.620 | 0.003641 | 27.89 | 0.003548 | −2.55 |

| 1.648 | 0.195 | 1.36 | 44.955 | 0.003475 | 44.26 | 0.003421 | −1.55 |

| 1.918 | 0.227 | 1.58 | 60.780 | 0.003467 | 60.75 | 0.003465 | −0.05 |

| 2.197 | 0.260 | 1.81 | 85.348 | 0.003711 | 83.74 | 0.003641 | −1.88 |

| 2.383 | 0.282 | 1.97 | 121.776 | 0.004501 | 123.55 | 0.004566 | 1.45 |

| Mesh Type | Base Mesh Sizes [m] | Time Step Size [s] |

|---|---|---|

| Coarse mesh | 0.2250 | 0.0120 |

| Medium mesh | 0.1575 | 0.0084 |

| Fine mesh | 0.1125 | 0.0060 |

| Base Mesh Sizes [m] | Time Steps [s] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0120 | 0.0084 | 0.0060 | |

| 0.2250 | 87.774 | 85.884 | 85.734 |

| 0.1575 | 86.336 | 85.060 | 84.124 |

| 0.1125 | 85.372 | 84.424 | 83.744 |

| Rt for Mesh Base Size Convergence (with Monotonic Convergence) | Rt for Time Step Convergence (with Monotonic Convergence) | |

|---|---|---|

| r21, r32 | ||

| f1 | 83.744 | 83.744 |

| f2 | 84.124 | 84.424 |

| f3 | 85.734 | 85.372 |

| R | 0.236 | 0.717 |

| p | 4.166 | 0.959 |

| fext | 83.627 | 82.019 |

| GCI21 | 1.37% | 2.45% |

| ITTC Method | Kristensen and Lützen | Computational Fluid Dynamics Results | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Froude Numbers | |||||||||

| 0.108 | 0.152 | 0.195 | 0.227 | 0.260 | 0.282 | Average | |||

| 0.8 | 0.6895 | 1.5541 | 0.9549 | 0.6651 | 0.5085 | 0.4445 | 0.4536 | 0.7634 | |

| 1000 | 0.1034 | 0.0900 | 0.2029 | 0.1246 | 0.0868 | 0.0664 | 0.0580 | 0.0592 | 0.0996 |

| Fn | Added Air Resistance at Calm Water | Added Wave Resistance at SS 4 | Added Wave Resistance at SS 5 | Added Wave Resistance at SS 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | ||||

| 0.108 | 5.21 | 5.33 | 11.83 | 53.76 |

| 0.152 | 3.48 | 3.50 | 7.76 | 42.60 |

| 0.195 | 2.51 | 2.51 | 5.56 | 31.25 |

| 0.227 | 1.90 | 1.88 | 4.17 | 22.95 |

| 0.260 | 1.58 | 1.56 | 3.46 | 19.89 |

| 0.282 | 1.28 | 1.26 | 2.81 | 13.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Göksu, B.; Erginer, K.E. Analyzing Added Wave and Superstructure Resistance Based on North Pacific Ocean Sea State. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11245. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411245

Göksu B, Erginer KE. Analyzing Added Wave and Superstructure Resistance Based on North Pacific Ocean Sea State. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11245. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411245

Chicago/Turabian StyleGöksu, Burak, and Kadir Emrah Erginer. 2025. "Analyzing Added Wave and Superstructure Resistance Based on North Pacific Ocean Sea State" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11245. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411245

APA StyleGöksu, B., & Erginer, K. E. (2025). Analyzing Added Wave and Superstructure Resistance Based on North Pacific Ocean Sea State. Sustainability, 17(24), 11245. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411245