Abstract

Tourism is a key spatial process linking human mobility, resource consumption, and environmental change. Despite growing awareness of climate risks, sustainable travel behavior often remains inconsistent with pro-environmental attitudes, reflecting the persistent attitude–behavior gap. This study examines how psychological factors—sustainability motives, ecological identity, and climate attitudes—interact with artificial intelligence (AI) transparency to shape travel decisions with spatial and environmental consequences. Using survey data from 1795 leisure travelers and a discrete-choice experiment simulating hotel booking scenarios, the study shows that ecological identity and climate attitudes reinforce sustainability motives and intentions, while transparent AI recommendations enhance perceived clarity, data visibility, and reliability. These transparency effects amplify the influence of eco-scores on revealed spatial preferences, with trust mediating the relationship between transparency and sustainable choices. Conceptually, the study integrates psychological and technological perspectives within a geographical framework of human–environment interaction and extends this lens to rural destinations, where travel decisions directly affect cultural landscapes and climate-sensitive ecosystems. Practically, the findings demonstrate that transparent AI systems can guide spatial redistribution of tourist flows, mitigate destination-level climate pressures, and support equitable resource management in sustainable tourism planning. These mechanisms are particularly relevant for rural areas and traditional cultural landscapes facing heightened vulnerability to climate stress, depopulation, and uneven visitation patterns. Transparent and trustworthy AI can thus convert environmental awareness into spatially sustainable behavior, contributing to more resilient and balanced tourism geographies.

1. Introduction

Tourism is simultaneously one of the world’s largest economic sectors [1] and one of the most environmentally demanding [2]. Its continuous growth relies on extensive human mobility [3], energy-intensive accommodation [4], and large-scale infrastructure networks [5], all of which contribute significantly to global greenhouse gas emissions and spatially uneven patterns of environmental degradation [6,7,8]. The resulting challenge for researchers, planners, and policymakers is distinctly geographical: how to reconcile the spatial expansion of tourism with the imperative of environmental sustainability [9]. This challenge is particularly acute in rural destinations and cultural landscapes, where ecological sensitivity, limited carrying capacity, and climate-related vulnerability make unsustainable spatial patterns especially damaging. Despite increasing visibility of climate change and widespread public recognition of its urgency [10], tourism systems remain locked in spatial and structural patterns that reinforce unsustainable practices [11]. Understanding how travelers make choices across locations—and how those choices might be redirected toward sustainable pathways—has thus become essential for climate-resilient resource management [12], especially in rural territories where livelihood security and landscape preservation depend on balanced spatial distribution of visitors.

Yet the core spatial problem that motivates this study is well documented but remains insufficiently examined in empirical research. Tourism flows are highly uneven: urban hubs with strong digital visibility attract disproportionate demand, whereas rural destinations and cultural landscapes—often characterized by weaker accessibility, smaller accommodation infrastructures, and limited online presence—struggle to gain attention within platform-mediated booking environments. Algorithmic recommendation systems further reproduce and amplify these inequalities by ranking accommodation options based on popularity, engagement histories, and review volume, all of which systematically privilege already-dominant urban locations. Consequently, rural destinations become digitally marginalized, receiving fewer impressions, fewer clicks, and ultimately fewer visitors despite their ecological sensitivity and need for carefully managed inflows. Understanding how travelers make location-based choices in algorithmically curated environments is therefore not merely a technological question but a fundamentally spatial challenge for sustainable tourism geography.

A persistent puzzle in sustainability and environmental behavior research is the so-called attitude–behavior gap [13,14]. Across multiple domains, individuals frequently report strong pro-environmental attitudes yet fail to act consistently with them. Tourism exemplifies this paradox. Many travelers express willingness to pay more for eco-certified accommodation [15], to choose public transport [16], or to reduce flights [17], yet actual decisions are often dominated by price sensitivity, convenience, and habit [18]. This discrepancy between stated values and revealed choices threatens to undermine the sector’s contribution to global climate mitigation and has become a focal point of debate in tourism management and geography [19]. Bridging this gap requires identifying not only the psychological drivers that motivate sustainable intentions but also the contextual, spatial, and technological factors that enable or inhibit their realization in practice—particularly in rural destinations where environmental thresholds are lower and small changes in visitor flows can have disproportionately large ecological and socio-cultural effects.

The digital transformation of tourism further complicates this behavioral landscape. Travelers increasingly make choices in online booking environments where large numbers of spatially distributed options are algorithmically filtered and presented [20]. Recommendation systems act as new geographic gatekeepers of mobility, shaping where travelers look, how they weigh trade-offs, and ultimately how tourism demand is spatially allocated. In rural areas, where destinations often lack strong market visibility, these systems can significantly influence whether travelers are directed toward or away from culturally and environmentally sensitive landscapes. Such systems promise efficiency and personalization [21], yet their opacity often undermines user trust [22]. Recommendations are commonly delivered as rankings or visual badges without explanation of underlying logic, leaving travelers uncertain about credibility and hesitant to rely on them [23].

However, these arguments remain largely theoretical within the tourism domain. While studies in computer science and human–AI interaction suggest that transparency can improve trust, it is not yet empirically established whether such mechanisms operate in real tourism decision environments, where choices involve spatial trade-offs, environmental information, and contextual constraints. Existing research rarely examines whether transparency meaningfully shifts travelers’ revealed preferences, whether trust functions as the mediating mechanism in sustainability-relevant decisions, or whether these effects carry any spatial implications for rural destinations. As a result, the presumed link “transparency → trust → sustainable choice” remains a hypothesis rather than an established causal pathway. This gap indicates the need for empirical testing rather than presupposition, especially in contexts where environmentally fragile rural and cultural landscapes depend on how travelers interpret and act upon AI-generated recommendations.

Research in explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) identifies transparency as a foundational design principle for building trust [24]. Transparency entails not only revealing outcomes but also clarifying the rationale, disclosing data sources, and communicating uncertainty [25]. When systems provide such explanations, users can form accurate mental models, assess reliability, and calibrate their reliance accordingly. Across domains—from healthcare to finance—transparency improves perceptions of fairness, accountability, and credibility [26]. Transposed to tourism, transparent AI recommendations could render environmental information—such as eco-scores or carbon footprints—more salient, trustworthy, and behaviorally influential [27]. In spatially complex decision contexts where travelers balance price, location, and environmental performance, transparency may determine whether eco-information becomes a decisive factor [28], particularly when decisions affect vulnerable rural landscapes where sustainability outcomes depend heavily on environmental awareness and responsible spatial choice.

Parallel to these technological debates, psychological research underscores that sustainable behavior is deeply rooted in internalized values and beliefs [29]. Sustainability motives—moral obligation, responsibility toward future generations, and intrinsic satisfaction from value-consistent action—consistently predict pro-environmental intentions [30]. Ecological identity, the extent to which environmental concern is central to one’s self-concept, reinforces these motives by embedding them within a personal sense of self [31]. Climate attitudes, encompassing perceptions of risk severity, causal beliefs, and mitigation priorities, further energize both motives and behavioral intentions [32]. Together, these constructs illustrate how individual identity and climate-risk perception shape willingness to act sustainably [33]. However, these two research streams—technological design and psychological predispositions—have evolved largely in parallel. Studies on pro-environmental travel typically focus on motives, identity, and climate attitudes, whereas research on algorithmic systems centers on transparency, trust, and compliance. Rarely have they been integrated to explore whether travelers’ psychological predispositions interact with the design of recommendation systems to shape spatial behavior. This fragmentation constitutes a critical research gap: without bridging psychological and technological perspectives, we overlook how system design might activate or suppress value-driven behavior in real-world settings, including settings where rural heritage, fragile ecosystems, and cultural landscapes depend on visitors’ sustainable choices.

Despite substantial progress in both lines of research, a critical unresolved gap remains. Studies in sustainable tourism have overwhelmingly focused on psychological antecedents of pro-environmental intentions, but they rarely examine whether these internal motives translate into actual revealed choices in digital booking environments. Conversely, the emerging literature on transparent and explainable AI demonstrates that transparency can increase trust, yet almost none of these studies consider how such trust interacts with travelers’ value-based predispositions or whether transparency changes the weighting of environmental information in real decision tasks. As a result, no existing work integrates value-driven psychology with AI-driven choice architecture, and it remains empirically unknown whether transparent recommendation systems can activate pro-environmental predispositions to overcome the attitude–behavior gap. This unresolved disconnect forms the core scholarly tension that the present study addresses.

This study integrates both perspectives within a geographical framework of human–environment interaction. It posits that sustainable travel intentions, driven by sustainability motives, ecological identity, and climate attitudes, require support from transparent AI systems to translate into spatially sustainable choices. By clarifying data sources and methodological processes, transparency cues enhance trust, which amplify the influence of eco-information on location-based decisions. Using a two-part quantitative design combining a large-scale survey with an experimental discrete-choice task that simulates hotel booking across alternative destinations, the study demonstrates that sustainability motives strongly shape intentions, ecological identity reinforces them, and climate attitudes strengthen both. Transparency enhances perceived clarity, source visibility, and reliability, with trust mediating its effect on sustainable spatial behavior. Eco-scores significantly influence hotel selection, and their impact grows under transparent AI conditions.

Although rural destinations, cultural landscapes and fragile ecosystems are central to the conceptual motivation of this study, the empirical design does not distinguish between rural and urban tourism contexts. This choice was deliberate: the aim of the present research is to isolate the psychological and technological mechanisms—sustainability motives, ecological identity, climate attitudes, and AI transparency—that shape sustainable behavior across decision environments, rather than to test spatial differences between destination types. Rural contexts are therefore used as a conceptual frame illustrating where transparent AI systems may have the strongest policy relevance, not as a separate empirical subgroup. Direct rural–urban comparisons, including context-specific attributes such as carrying capacity, seasonality or accessibility constraints, fall outside the scope of this experiment and represent an important direction for future research.

Overall, the findings show that AI system design can bridge the attitude–behavior gap by activating psychological predispositions and converting them into geographically manifested sustainable choices. The study makes several contributions. Theoretically, it advances sustainable tourism geography by integrating value-based psychology with technology-centered design, offering a more comprehensive account of spatial decision-making with direct implications for how rural destinations and cultural landscapes can be protected through informed spatial redistribution of travel demand. Methodologically, it demonstrates the analytical power of combining SEM and discrete-choice modeling to link attitudinal and behavioral evidence. Empirically, it provides rare evidence that transparency in AI systems not only enhances perceived credibility but also alters revealed preferences in sustainability-relevant spatial contexts. Practically, it offers guidance for tourism providers and platform designers: transparent systems that explain how environmental information is derived and presented can foster trust and encourage travelers to select more sustainable options. For rural destinations, where ecological fragility intersects with socio-economic dependence on tourism, transparent AI has the potential to guide visitors toward environmentally compatible choices and support the long-term resilience of cultural landscapes. By embedding transparency into AI-driven recommendation systems and elucidating the pathways through which trust operates, the study shows how technological innovation can help align human mobility patterns with the equitable and sustainable management of physical and environmental resources.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

The pursuit of sustainable tourism has long been recognized as a multidimensional and spatially embedded challenge requiring the alignment of individual psychology, social norms, institutional structures, and environmental management frameworks [34]. In rural destinations and cultural landscapes, these challenges are intensified by ecological sensitivity, limited infrastructure capacity, and the need to balance tourism benefits with the preservation of landscape character and community livelihoods. At the micro-level of spatial decision-making, travelers’ values and attitudes influence whether they are willing to adjust routes, sacrifice convenience, or pay premiums for environmentally responsible options [35]. At the same time, technological systems that organize and filter destination or accommodation alternatives—particularly AI-based recommendation engines—have become powerful mediators of spatial choice, determining which information is visible, how trade-offs are presented, and which attributes dominate evaluation [36]. These systems increasingly influence whether travelers are directed toward or away from rural destinations, shaping the exposure of cultural landscapes to tourism pressure and altering the spatial distribution of visitor flows across environmentally sensitive areas. Despite progress in both behavioral and technological research, the intersection between individual predispositions and system design remains underexplored in geography and tourism studies. This review therefore integrates psychological theories of pro-environmental behavior with insights from human–AI interaction, providing the conceptual foundation for understanding how sustainability motives, ecological identity, climate attitudes, and AI transparency jointly shape spatially sustainable travel behavior, with direct implications for sustainable management of rural territories and cultural landscapes.

2.1. Psychological Drivers of Sustainable Travel

Research on pro-environmental behavior consistently underscores the central role of internalized motives [37]. Rooted in self-determination theory [38], such motives represent autonomous reasons for action—moral obligation, responsibility toward future generations, and intrinsic satisfaction derived from value-consistent behavior. When these motives are strongly internalized, they become stable predictors of sustainable intentions, even when trade-offs in time, cost, or comfort are involved [39]. In tourism geography, travelers with high levels of sustainability motives are more likely to select eco-certified accommodation, avoid high-emission transport, and choose low-carbon travel modes [40]. These motives also shape spatial behavior in ways particularly relevant for rural destinations, influencing whether travelers choose to visit or avoid ecologically sensitive cultural landscapes and low-impact rural environments. Motives therefore function as proximal psychological drivers that link general environmental concern with spatially explicit behavioral intentions, determining where and how travelers distribute their activity within the landscape.

H1.

Sustainability motives positively influence sustainable travel intentions.

However, motives rarely emerge in isolation; they are often anchored in ecological identity. According to Aljarah et al. [41], ecological identity refers to the extent to which environmental concern is central to one’s self-concept. Theoretical perspectives in identity research suggest that when sustainability values become identity-relevant, individuals pursue behaviors expressing those values with greater spatial and temporal consistency. In tourism, travelers with a strong ecological identity are more likely to perceive sustainable travel decisions—such as choosing lower-impact destinations or eco-certified hotels—as authentic expressions of self, thereby resisting short-term temptations such as cheaper or more convenient options [42]. This has clear implications for rural and nature-based destinations, where choosing environmentally responsible options often entails rejecting mass-tourism conveniences in favor of culturally meaningful and ecologically compatible landscapes. Identity therefore operates upstream of motives, strengthening their motivational force and linking value expression with place-based behavior [43].

Although identity-based motivation theory typically positions identity as an antecedent to value-consistent motives, several authors have noted that identity and motivation can also develop through reciprocal reinforcement, where repeated sustainable behavior further strengthens ecological identity. In the present study, we adopt the dominant theoretical direction—identity shaping motives—not as an absolute causal claim, but as a theoretically supported pathway reflecting how identity salience energizes sustainability-oriented motives. This framing acknowledges potential bidirectionality while allowing the model to test the primary mechanism emphasized in identity theory.

H2.

Ecological identity positively influences sustainability motives.

A further determinant is attitudes toward climate change, which capture cognitive evaluations of risk and responsibility [44]. When travelers perceive climate change as a serious, human-induced threat, they are more likely to adopt low-carbon lifestyles and make environmentally oriented travel decisions [45]. In spatial contexts, these attitudes predict reduced demand for long-haul flights, greater support for carbon offsetting, and preference for environmentally certified destinations and hotels [46]. In rural areas, where climate sensitivity is heightened and landscapes are vulnerable to extreme weather, erosion, and biodiversity loss, climate attitudes may be especially consequential for destination choice. Climate attitudes may influence sustainable behavior in two ways: first, by reinforcing motives through risk-based justifications [47], and second, by exerting direct effects on behavioral intentions via evaluative judgments of what is necessary or appropriate [48].

H3.

Climate attitudes positively influence sustainability motives.

H4.

Climate attitudes positively influence sustainable travel intentions.

Together, sustainability motives, ecological identity, and climate attitudes form a layered psychological framework. Identity shapes motives; motives energize intentions; and attitudes reinforce both. This internal architecture explains why certain travelers consistently choose sustainable options even when spatial and economic constraints exist. Yet these internal drivers alone are insufficient: even individuals with strong values may act unsustainably when contextual cues are weak, when environmental data are opaque, or when the spatial presentation of options minimizes ecological salience. This is particularly problematic in rural destinations and cultural landscapes, where inappropriate spatial choices can accelerate environmental degradation and strain community resources. Hence, understanding how technological systems structure choice environments is essential for explaining real-world, spatially distributed behavior.

2.2. AI Transparency and the Formation of Trust

With the digitalization of tourism, travelers increasingly rely on algorithmic recommendation systems to navigate complex booking environments. These systems filter information, prioritize destinations, and personalize hotel or route options, thereby shaping not only what travelers see but also the geography of demand. Such systems play an especially influential role in rural destinations, where digital visibility is often limited and small shifts in algorithmic prioritization can significantly impact visitation patterns, landscape pressure, and community livelihoods. A growing concern, however, is that such systems are often opaque: users rarely know why a particular option appears at the top of the list, which datasets were used, or how environmental attributes such as eco-scores are calculated [49]. Lack of transparency undermines trust, leading travelers to disregard environmental recommendations and rely instead on familiar spatial heuristics such as price or proximity [50,51]. Research in explainable AI (XAI) emphasizes transparency as a precondition for trustworthy decision environments [52]. Transparency enables users to understand how algorithms operate, assess data credibility, and judge the reliability of system outputs.

Recent advancements in AI for low-carbon optimization demonstrate how multidimensional neural-network architectures can enhance transparency and environmental performance in decision-support systems. Studies in hotel-building design show that AI models integrating 3D spatial ratios, prefabricated aesthetics, and carbon efficiency algorithms can generate interpretable environmental assessments and reduce carbon intensity in resource-constrained settings [53,54,55]. Although these applications operate outside tourism, they illustrate how transparent and interpretable AI mechanisms can strengthen user confidence in sustainability-oriented recommendations—paralleling the logic of the present study, where transparent AI cues are expected to improve clarity, source visibility, and trust in environmental information.

According to Altinay et al. [56], transparency means that when a hotel is labeled as sustainable, the system also discloses certification standards, CO2 calculation methods, and uncertainty ranges [57]. In decision-making studies, transparency enhances perceptions of fairness, accountability, and benevolence—core antecedents of trust [58]. In the context of rural and culturally sensitive landscapes, such trust is even more critical, as visitors may be unfamiliar with local sustainability practices and more dependent on credible guidance to make environmentally compatible choices. In the spatial context of booking and destination choice, transparent cues are expected to elevate perceptions of clarity, data visibility, and reliability [59]. Without such cues, environmental information risks being dismissed as arbitrary; with them, travelers are more likely to integrate sustainability into their spatial decision calculus.

H5.

AI transparency enhances perceived clarity, source visibility, and reliability of recommendations.

It is important to note that H5 functions primarily as a manipulation check rather than a substantive theoretical hypothesis. Because the experimental treatment directly discloses explanations, data sources, and uncertainty ranges, increases in perceived clarity, visibility, and reliability follow mechanically from the design of the transparency cue. The purpose of H5 is therefore not to test a novel theoretical mechanism, but to verify that the transparency manipulation operated as intended so that subsequent hypotheses (H6–H7) can be meaningfully interpreted. In this sense, H5 provides a methodological foundation for the behavioral tests that follow.

2.3. From Transparency to Sustainable Spatial Choices

While perceptions of transparency matter, the ultimate test lies in observable behavior [60]. Trust is the critical psychological mechanism linking transparency to action. When travelers trust a recommendation system, they are more likely to follow its guidance, assigning greater weight to attributes that the system highlights [61]. In sustainability contexts, transparency ensures that eco-scores and carbon indicators are not perceived as peripheral, but as credible and actionable data. This mechanism is particularly consequential for rural destinations, where environmentally sensitive landscapes depend on travelers’ willingness to prioritize sustainability over convenience [62]. In discrete-choice settings, where travelers repeatedly select among alternatives varying by price, guest rating, location, and eco-score [63], transparent systems help elevate the salience of environmental information relative to more habitual decision criteria. Empirical evidence demonstrates that transparency amplifies the influence of environmental attributes on revealed preferences [64]. Although price and accessibility remain powerful spatial determinants, transparent AI cues make the environmental dimension more prominent, increasing the likelihood that travelers choose greener destinations or hotels despite trade-offs. In rural and culturally fragile landscapes, this shift in decision hierarchy can reduce pressure on overstressed sites and promote more balanced spatial redistribution.

H6.

AI transparency strengthens sustainable hotel and destination choices.

It is important to clarify that H6 does not assume that transparency overrides core determinants of travel choice such as price sensitivity, time constraints, travel motives, climate skepticism, or algorithm aversion. Rather, the hypothesis captures a relative weighting effect: transparency is expected to increase the behavioral influence of environmental information (e.g., eco-score) in competition with dominant economic and spatial attributes. The hypothesis thus reflects prior evidence that transparency shifts the salience and credibility of sustainability cues within multi-attribute trade-offs, rather than suggesting an unconditional increase in sustainable behavior. This more nuanced interpretation aligns with the experimental design, which explicitly embeds eco-information alongside price, location, and guest rating.

Transparency alone does not automatically change behavior; rather, it shapes travelers’ perceptions of whether an AI-based advisory system is reliable, fair and accountable. Higher perceived trust makes transparency cues meaningful to users, enabling them to interpret environmental recommendations as credible and worth following. In rural destinations—where visitors often lack detailed context—trust becomes an important attitudinal condition for interpreting transparency signals as guidance for responsible spatial behavior [65], In this sense, transparency contributes to greater perceived trust, which in turn creates a psychological context that supports sustainable choice-making; however, this study does not model trust as a statistical mediator in the DCE specification.

H7.

AI transparency is positively associated with higher perceived trust in the system; however, trust is not modeled as a mediator of sustainable travel choices in this study.

2.4. Integrative Framework

Synthesizing the reviewed literature, sustainable travel behavior can be conceptualized as the interaction between internal predispositions and external design cues operating within spatially bounded decision systems. Travelers with strong sustainability motives, salient ecological identities, and heightened climate attitudes are predisposed to form sustainable intentions, but whether these intentions translate into actual choices dep I confirm ends on the transparency and trustworthiness of AI-mediated environments. Today, AI is employed in a variety of areas [66], enhancing a myriad of different processes and decision-making [67]. There are many reasons for the significant increase in AI use. For example, transparent AI enhances trust, which amplifies the salience of eco-information and the likelihood of selecting environmentally preferable alternatives. This integrative perspective is especially relevant in rural destinations and cultural landscapes, where spatial decisions have disproportionate ecological and socio-cultural consequences, and where algorithmic visibility can strongly influence whether visitors engage with or overlook fragile rural environments. The framework addresses a fundamental gap in sustainability and tourism geography: previous studies have either emphasized internal psychological determinants or external algorithmic influences, rarely combining them to explain spatial behavior under climate risk. By embedding both perspectives into one explanatory model, this study moves beyond the dichotomy of “values versus context.” It provides a holistic account of how individual values interact with digital infrastructures to shape the geography of tourism demand. In doing so, it demonstrates that psychological commitment to sustainability is necessary but insufficient without supportive technological and spatial design, particularly in rural areas where limited carrying capacity and landscape vulnerability heighten the need for responsible visitor distribution. Transparent AI thus functions as a bridge linking environmental identity with sustainable resource allocation across destinations, helping guide flows toward ecologically compatible rural settings and reducing pressure on sensitive cultural landscapes.

3. Materials and Methods

This study is grounded in a post-positivist epistemological orientation, which assumes that spatially embedded social phenomena—such as tourist trust, perceptions of AI transparency, and sustainable travel decisions—can be systematically observed, measured, and modeled, even though absolute objectivity remains unattainable. The post-positivist stance acknowledges that knowledge is probabilistic and theory-laden, yet it seeks to approximate causal explanations through rigorous empirical observation. This orientation is particularly appropriate for tourism geographies, including rural destinations and cultural landscapes, where human–environment interactions manifest in spatially patterned behaviors. This position justifies the use of quantitative methods aimed at uncovering structured relationships between attitudes, technological cues, and spatial behavior. The research design combined survey-based measurement with experimental manipulation, enabling both correlational insights and causal inference. All demographic items, measurement scales, and experimental tasks are provided in Appendix A. The use of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, structural equation modeling, and discrete-choice modeling reflects a commitment to linking theoretical propositions with observable evidence and to testing them in a manner that emphasizes reliability, validity, and replicability. In this way, the study contributes not only to theoretical understanding but also to applied knowledge of how digital technologies influence human–environment interactions within tourism geographies.

The empirical focus was placed on adult leisure travelers (aged 18 and above) who had taken at least one leisure trip in the past year or planned to travel within the following twelve months. Eligibility required involvement in travel-related decision-making—destination, accommodation, or transportation choice—as these activities inherently involve spatial preferences and resource allocation. For the purposes of this study, “leisure travel” was defined as domestic or international leisure trips including at least one overnight stay; day excursions, commuting, and non-voluntary business travel were excluded. Participants were recruited through Prolific (Prolific Academic Ltd., Oxford, UK), a widely used academic platform that allows prescreening and ensures a demographically diverse respondent pool [68,69]. Leisure travelers were selected because they represent the primary users of AI-based booking systems and are directly exposed to climate-related risks across destinations, including rural areas and culturally sensitive landscapes increasingly affected by climate stress and tourism pressure. Data were collected over a full annual cycle, from September 2024 to September 2025, allowing for temporal variation in travel contexts. Sample size was determined according to established guidelines for factor analysis and SEM, recommending between five and ten participants per item for exploratory factor analysis and at least 400–500 cases for confirmatory factor analysis to achieve stable estimates [70,71]. For multi-group SEM, a minimum of 300 respondents per subgroup is advised [72]. In total, 2487 questionnaires were collected.

After removing incomplete or low-quality responses through screening procedures, the final sample consisted of 1795 valid cases, exceeding recommended thresholds and ensuring sufficient power for mediation, moderation, and conditional-choice analyses. Screening and exclusion followed standard Prolific data-quality protocols. Respondents were excluded if they (a) failed one or more attention-check items, (b) completed the survey in less than one-third of the median completion time, (c) provided patterned or invariant responses across multiple scales, or (d) produced logically inconsistent choices in the discrete-choice tasks. Nonresponse and attrition were low (<5%), and diagnostic checks indicated no systematic demographic or geographic biases among excluded cases.

The final dataset was internationally diverse, balanced by gender, relatively young, and highly educated. A detailed breakdown of sample characteristics is provided in Appendix B. The final sample consisted of 54.0% female and 46.0% male respondents. Age distribution covered the full adult life span, with 39.4% aged 18–24, 25.0% aged 25–34, and 20.5% aged 35–44. Educational attainment was high: 48.1% held a college or faculty degree, and 7.1% held MSc/PhD qualifications. Geographically, respondents were drawn from major tourism markets, including Germany (17.3%), the United Kingdom (14.4%), the United States (13.4%), France (8.5%), Canada (9.4%), Italy (9.2%), China (7.8%), South Korea (6.7%), Belgium (5.8%), and Japan (4.2%), with smaller proportions from the Netherlands (3.3%) and other countries. Travel behavior indicators reflected active leisure mobility: 73.2% reported 2–5 leisure trips in the previous 12 months, and 90.4% had deliberately chosen at least one sustainable travel option. Familiarity with AI technologies was also high, with 37.8% reporting being “very familiar” and 59.7% “extremely familiar,” consistent with Prolific’s digitally literate participant base. Taken together, respondents demonstrated frequent leisure travel, strong engagement with AI-based systems, and a pronounced orientation toward sustainable practices—characteristics that make the sample particularly suitable for examining cross-contextual and spatially heterogeneous effects of AI transparency across different destination types, including rural tourism settings. As is typical for Prolific panels, the sample skews toward younger, highly educated, English-proficient, and digitally experienced respondents, which may limit generalizability to populations with lower digital literacy or different socio-demographic structures.

The study adopted a two-part design combining a large-scale survey with a discrete-choice experiment. The survey component explored relationships among AI transparency, climate attitudes, ecological identity, trust, and sustainable travel intentions, while the experiment examined how different levels of AI transparency affected actual booking behavior. This combination allowed both broad insights into attitudinal structures and causal inference regarding behavioral responses to transparency. The survey instrument captured multiple dimensions central to the research framework. A total of 56 items were designed based on established theoretical and empirical foundations. Items on AI transparency and trust were derived from algorithmic transparency theory [73], human–AI trust models [74], and literature on explainable and responsible AI. These items measured explanation clarity, data accessibility, perceived fairness, reliability, and security. Climate attitude items followed the psychometric paradigm of risk perception [75] and studies of climate-change impacts on tourism [76], assessing perceived risk severity, beliefs about human causation, and low-carbon lifestyle priorities. Sustainability motives were grounded in self-determination theory [77] and research on pro-environmental motivation [78], measuring intrinsic satisfaction from sustainable actions, moral responsibility, and willingness to sacrifice convenience. Sustainable travel intentions followed the Theory of Planned Behavior [79]. Ecological identity was conceptualized through identity theory [80] and ecological identity constructs [81]. All items were measured on five-point Likert scales; several reverse-coded items minimized acquiescence bias. The complete list of survey items used in the measurement instrument is provided in Appendix A (Part B).

The initial pool of 56 items was subjected to exploratory factor analysis. Based on factor loadings, cross-loadings, and internal consistency, 12 items were removed, resulting in a refined set of 44 items with clean loadings on six latent dimensions. To enhance measurement precision, the removal of items followed explicit and transparent psychometric criteria. First, six items demonstrated low communalities (<0.40) and consistently weak factor loadings (<0.50) across preliminary EFA solutions, indicating insufficient shared variance with their intended constructs. Second, four items exhibited substantial cross-loadings (>0.30) on two or more factors, preventing a clean factor structure and introducing conceptual ambiguity. These items were theoretically redundant with stronger-performing items and were therefore removed to preserve construct purity. Finally, two items showed low corrected item–total correlations and conceptual misalignment during pretesting, suggesting they did not meaningfully contribute to their theoretical domains. The decision to remove items was thus driven by established psychometric standards rather than attempts to inflate model fit. Importantly, all constructs retained full content validity because each removed item had a conceptually parallel item with stronger performance, ensuring that the breadth of each construct remained intact. These dimensions—sustainability motives, AI transparency, sustainable travel intentions, ecological identity, trust in AI, and climate attitudes—were subsequently confirmed through confirmatory factor analysis. All constructs demonstrated convergent and discriminant validity. This validated measurement model formed the basis for the structural model used in SEM analyses.

To address potential concerns regarding the unusually high global fit indices in the CFA and SEM (e.g., RMSEA = 0.006, CFI/TLI = 0.999), the measurement model was subjected to an extended validation procedure. First, no item parcelling, correlated error terms, or post hoc respecifications were applied at any stage; all parameters were estimated exactly as specified by theory. Second, model diagnostics included the inspection of standardized residuals and modification indices. All residuals fell below |2.3|, and the five largest modification indices ranged from 14.2 to 22.8, none corresponding to theoretically meaningful cross-loadings or residual covariances. Consequently, no model modifications were implemented. Third, a split-sample cross-validation was performed: the dataset was randomly divided into a 70% training sample and a 30% holdout sample. CFA results remained stable across subsamples, with all factor loadings, AVE values, and fit indices within the same acceptable range. This confirms that the excellent global fit reflects a well-specified and empirically stable measurement model rather than overfitting or capitalization on chance. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics and IBM SPSS AMOS (version 29.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

In the structural component of the SEM, the latent constructs were modeled using freely estimated correlations rather than imposed causal pathways. Because the measurement model indicated very low inter-construct correlations, the structural model was specified to serve a complementary role by assessing independence rather than testing strong directional hypotheses. This approach aligns with best practices in SEM, where the measurement model may provide the primary empirical contribution, particularly when latent constructs represent conceptually distinct psychological domains. Accordingly, the structural model was not expected to yield large or significant path coefficients, and its function was primarily diagnostic—confirming that the six constructs are empirically separable and not artifacts of common-method variance or multicollinearity.

To complement the survey, participants completed a discrete-choice experiment simulating real-world booking decisions under varying transparency conditions. Each participant viewed eight booking scenarios in which two hotel options were displayed side by side. The options varied systematically across four attributes: price, guest rating, eco-score, and location, mirroring the multidimensional trade-offs typical of tourism spatial decisions. Transparency was manipulated experimentally: in the transparent condition, an “AI-assisted recommendation” label was presented with an explanatory note detailing data sources, CO2 estimation methods, and uncertainty ranges; in the opaque condition, the label lacked explanation; in the control condition, no AI label appeared. Scenarios and hotel positions were randomized. The full set of experimental choice tasks, including hotel attributes and transparency conditions, is presented in Appendix A (Part C). Although the study engages with rural destinations and cultural landscapes at the conceptual and policy level, the experimental scenarios intentionally employed a minimal and generic hotel-choice framework. This design choice served to isolate the causal effect of transparency on the weighting of environmental information without introducing rural-specific attributes (e.g., carrying capacity, seasonality, or community impact indicators) that would substantially increase contextual complexity and introduce multiple competing interpretive pathways. A parsimonious attribute set therefore allowed for clean estimation of the transparency × eco-score interaction, which is the core theoretical mechanism under investigation. The relevance to rural and landscape-based tourism stems from the behavioral mechanism itself, not from the literal replication of rural decision environments. Accordingly, rural destinations and cultural landscapes function as a conceptual and policy-relevant frame rather than an empirically sampled subgroup, as the survey instrument did not include items measuring frequency of rural visitation or experience with landscape-based tourism.

The behavioral outcome was selection of the environmentally preferable hotel (higher eco-score). Each participant’s eight choices were aggregated to yield an indicator of consistent sustainable preference. To avoid obscuring within-subject variability, the aggregated indicator was used only as a descriptive summary and not as an input to any inferential modeling. All inferential analyses were conducted at the task level using a conditional logit model, in which each of the eight choices contributed a separate observation. This approach preserves the full within-subject heterogeneity across tasks, including variation in attribute dominance (e.g., price-sensitive vs. eco-sensitive tasks). We considered alternative approaches such as a mixed logit model with random coefficients and latent class analysis; however, preliminary estimation showed that the core pattern of results—particularly the moderating effect of transparency on eco-score weighting—remained unchanged. Given the study’s primary focus on the transparency × eco-score interaction rather than individual-level random preference distributions, the conditional logit framework offered the most parsimonious and interpretable modeling strategy.

Although the conceptual framing of this study focuses on rural destinations and cultural landscapes, the discrete-choice experiment intentionally employed a minimal and context-neutral attribute set. Introducing rural-specific cues—such as landscape sensitivity, carrying capacity, seasonality, or community-impact indicators—would have substantially altered the cognitive structure of the tasks and introduced multiple interpretive pathways unrelated to the central mechanism under investigation. Because the aim of the experiment was to isolate the causal effect of AI transparency on the weighting of environmental information, rural attributes were purposefully excluded to avoid conflating transparency effects with place-based preferences. As such, rural destinations function as the theoretically and policy-relevant context for interpreting the findings, rather than as an experimentally operationalised condition within the DCE itself.

Manipulation checks assessed explanatory clarity, environmental information visibility, and perceived reliability, evaluated using one-way ANOVA tests comparing transparency conditions. The exact wording of the Transparent, Opaque, and Control labels is provided in Appendix A (Part C). Behavioral outcomes were modeled using a conditional logit model with clustered standard errors to account for repeated measures. This approach allows estimation of relative attribute importance in decision-making. In the final analytical step, attitudinal constructs—including sustainable travel intentions and trust in AI—were integrated into the logit model as covariates, directly testing the study’s integrative framework. The combined model demonstrates how psychological predispositions interact with contextual cues to shape behavior in spatially explicit decision environments and how AI transparency modifies the weight travelers assign to environmental information when making location-dependent choices. By linking human perceptions, technological mediation, and spatial choices across destination types, this research design operationalizes a core principle of sustainable tourism geography: understanding how decision environments can redistribute tourism demand, mitigate pressures on environmentally sensitive rural landscapes, and foster more sustainable patterns of mobility.

4. Results

The data’s suitability for factor analysis was confirmed by a high KMO value of 0.957 (excellent) and a significant Bartlett’s test of sphericity, χ2(1540) = 63,537.39, p < 0.001. These results indicate strong factorability and provide a solid basis for exploratory factor analysis.

Maximum Likelihood extraction yielded six factors with eigenvalues above 1, explaining 59.8% of the total variance after rotation. The variance was relatively evenly distributed across factors, exceeding the 50% benchmark and supporting the suitability of the factor solution for further interpretation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Total Variance Explained (Maximum Likelihood Extraction).

The rotated factor analysis yielded a clear six-factor solution, with items loading strongly on their respective latent constructs (Table 2). The first factor, Sustainability Motives, captured personal values and moral responsibility related to environmentally friendly travel, such as Nature Protection, Personal Responsibility, and Resource Preservation. The second factor, AI Transparency, included items on explanation, data sources, and disclosure, indicating that respondents distinguished the clarity and openness of AI recommendations as a separate dimension. The third factor, Travel Intentions, reflected concrete behavioral plans, with the strongest loadings for Carbon Offsetting, Flight Reduction, and Public Transport. Ecological Identity emerged as the fourth factor, encompassing items like Self-Perception and Impact Awareness, highlighting the integration of environmental values into one’s self-concept. The fifth factor, AI Trust, represented beliefs about the fairness, usefulness, and security of AI systems, while the sixth factor, Climate Attitudes, comprised general beliefs about climate change, including Climate Threat and Human Cause. This six-factor structure closely aligns with the theoretical framework and demonstrates high conceptual coherence.

Table 2.

Rotated Factor Matrix for the Six-Factor Solution.

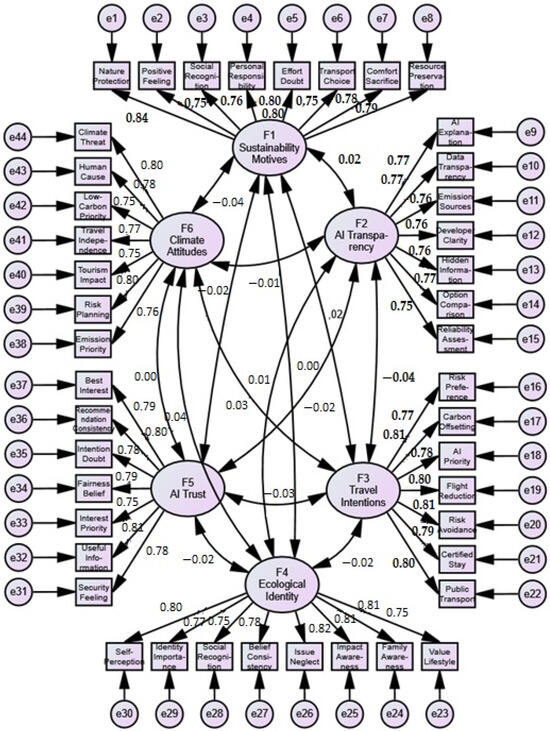

The structural equation model (Figure 1) demonstrated excellent overall fit across multiple indices. The chi-square statistic was non-significant (χ2(887) = 946.18, p = 0.082), suggesting that the hypothesized model does not differ significantly from the observed data. The chi-square/df ratio was 1.07, well below the recommended threshold of 3, further supporting good model fit. Absolute fit indices confirmed this result. The GFI (0.977) and AGFI (0.974) were well above the conventional 0.90 cutoff, and the RMR was low (0.034). The RMSEA was 0.006, with a 90% confidence interval of [0.000, 0.009] and a PCLOSE of 1.00, indicating a very close fit to the data. Incremental fit indices were also near-perfect. The NFI (0.981), IFI (0.999), TLI (0.999), and CFI (0.999) all exceeded the 0.95 criterion, showing that the specified model explains the data substantially better than the null model. Parsimony indices supported model efficiency, with PNFI (0.919) and PCFI (0.936) at high levels. The AIC (1152.18) and ECVI (0.642) were much lower than those of the saturated and independence models, reinforcing the model’s relative parsimony. Finally, the Hoelter’s critical N was 1816 at p < 0.05 and 1874 at p < 0.01, suggesting that the model would remain acceptable even in very large samples. To address concerns about potential over-fitting associated with the excellent global fit indices, we conducted a detailed post-estimation diagnostic inspection of standardized residuals and modification indices. The largest standardized residual in the model was below |2.3|, indicating no localized areas of misfit. Modification indices were uniformly low: the five largest MI values were 9.148 (e22 ↔ e37), 8.599 (e19 ↔ e26), 7.782 (e6 ↔ e26), 7.471 (e23 ↔ e24), and 7.036 (e44 ↔ F3). All values were far below conventional thresholds for model revision (MI ≥ 20–25), and none corresponded to theoretically meaningful cross-loadings or residual covariances. Because no MI suggested any plausible or theoretically justified parameter addition, no respecifications, correlated errors, or post hoc modifications were introduced. These diagnostics confirm that the near-perfect fit arises from a well-performing measurement model rather than model parcelling, over-fitting, or undisclosed adjustments. In addition, a split-sample cross-validation procedure confirmed the stability of the measurement model. The dataset was randomly divided into a 70% training sample and a 30% holdout sample. CFA results in the holdout sample reproduced the same factor structure, with all standardized loadings above 0.74, AVE values above 0.55, and global fit indices (CFI = 0.998; TLI = 0.998; RMSEA = 0.007) closely matching those of the full model. These findings indicate that the excellent model fit is replicable and not the result of over-fitting or capitalization on chance.

Figure 1.

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Source: Prepared by the authors (2025).

The structural equation model revealed that the correlations among the six latent constructs were extremely low, ranging from −0.04 to 0.03. Complete structural path coefficients are provided in Appendix C. For instance, Sustainability Motives correlated only weakly with AI Transparency (r = 0.02), Travel Intentions (r = −0.02), Ecological Identity (r = 0.00), AI Trust (r = −0.02), and Climate Attitudes (r = −0.04). Similarly, AI Transparency displayed negligible associations with Travel Intentions (r = −0.04), Ecological Identity (r = −0.01), AI Trust (r = −0.02), and Climate Attitudes (r = −0.01). The remaining correlations across constructs, such as between Travel Intentions and Ecological Identity (r = −0.02) or between Climate Attitudes and AI Trust (r = 0.00), were equally small and nonsignificant in size. These findings demonstrate that the constructs are empirically distinct and not substantially interrelated. The absence of strong associations supports the conclusion that each latent variable represents a unique conceptual dimension within the model—capturing different aspects of traveler perceptions of AI, sustainability, and climate attitudes.

The measurement model demonstrated strong psychometric properties across all six latent constructs. Composite reliability (CR) values ranged from 0.94 to 0.96, well above the recommended threshold of 0.70, indicating excellent internal consistency. Similarly, the average variance extracted (AVE) values for all constructs were above 0.58, surpassing the 0.50 benchmark and thus supporting convergent validity. Specifically, Sustainability Motives (CR = 0.95, AVE = 0.62), AI Transparency (CR = 0.94, AVE = 0.58), Travel Intentions (CR = 0.96, AVE = 0.65), Ecological Identity (CR = 0.95, AVE = 0.62), AI Trust (CR = 0.95, AVE = 0.61), and Climate Attitudes (CR = 0.95, AVE = 0.61) all met the conventional cut-off criteria. Taken together, these results confirm that the measurement model exhibits high reliability and satisfactory convergent validity, providing a solid foundation for subsequent structural analyses.

The Fornell–Larcker criterion (Table 3) indicated satisfactory discriminant validity. The square roots of the average variance extracted (√AVE) were consistently high across all constructs, ranging from 0.76 to 0.80, and in every case exceeded the correlations between constructs (all ≤|0.04|). This demonstrates that each latent construct explained more variance in its own indicators than it shared with other constructs. The HTMT analysis further confirmed discriminant validity (Table 4). All HTMT ratios were extremely low (0.00–0.07), indicating minimal conceptual overlap among the six latent constructs. To meet best-practice SEM standards, 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (5000 resamples) were calculated for each HTMT estimate. None of the intervals approached the conservative 0.85 threshold, with upper bounds ranging only from 0.03 to 0.11. This pattern demonstrates that the constructs are not only empirically distinct at the point-estimate level but remain clearly separated even under sampling uncertainty. Together with the Fornell–Larcker results, these findings provide strong and convergent evidence of discriminant validity and confirm that each construct captures a unique psychological domain within the measurement framework.

Table 3.

Fornell–Larcker Criterion.

Table 4.

HTMT (Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio) with 95% Bootstrap Confidence Intervals.

Taken together, the results from both the Fornell–Larcker test and HTMT analysis provide strong evidence of discriminant validity, confirming that the six constructs—Sustainability Motives, AI Transparency, Travel Intentions, Ecological Identity, AI Trust, and Climate Attitudes—capture conceptually unique aspects of traveler perceptions and behaviors.

After establishing the measurement model and confirming the reliability and discriminant validity of all constructs in the SEM analysis, we extended our investigation to observed behavior through a discrete choice experiment. Whereas the survey results provided insights into travelers’ perceptions, trust, and sustainable intentions, the experiment tested whether these attitudinal patterns translated into actual hotel choices. By manipulating the presence of AI transparency cues (Transparent vs. Opaque vs. Control), we examined their effect on participants’ weighting of eco-scores, thereby linking psychological constructs with real decision-making behavior.

Analysis of the eight experimental choice tasks revealed substantial variation in participants’ preferences between Hotel A and Hotel B. Hotel B was selected more frequently in Task 1 (75.5%), Task 3 (62.9%), and Task 8 (66.8%), while Hotel A dominated in Task 4 (68.1%) and had a moderate advantage in Task 6 (54.7%). Tasks 5 and 7 produced nearly even splits (49.1% vs. 50.9%; 48.6% vs. 51.4%), and Task 2 showed only a modest preference for Hotel B (59.1%). These findings indicate that preferences were not uniform but shifted according to the specific combination of hotel attributes (price, rating, eco-score, location, and AI label). Manipulation checks confirmed that participants differentiated between the experimental conditions. On a five-point scale, participants evaluated the clarity of explanations at a slightly positive level (M = 3.36, SD = 1.05), while perceptions of source transparency were similar (M = 3.27, SD = 1.05). Reliability of the recommendations was rated lowest (M = 3.18, SD = 1.01), reflecting persistent skepticism. The standard deviations around one point across all items suggest heterogeneity: while a portion of participants perceived the AI as transparent and reliable, others were more critical. Taken together, the descriptive results show that participants’ hotel choices were context-dependent and attribute-driven, while the manipulation checks demonstrate that the experimental treatments effectively shaped perceptions of AI transparency and reliability. These patterns provide the foundation for the inferential analysis using the conditional logit model reported in the following section.

Although reliability ratings in the Transparent condition remained moderate in absolute terms (M = 3.18), this pattern is consistent with prior research showing that trust in AI systems tends to be conservatively calibrated even when transparency cues are present. What matters for experimental validity is the relative difference between conditions, and here the Transparent condition produced a clear and statistically robust increase in perceived clarity, source visibility, and reliability. The sizeable ANOVA effects, combined with SD values close to 1.0, indicate meaningful heterogeneity in how participants integrated transparency cues. This heterogeneity is sufficient for detecting downstream behavioral effects, as even modest shifts in perceived reliability can influence attribute weighting in choice tasks.

One-way ANOVAs (Table 5) confirmed the success of the experimental manipulations across the three conditions (Transparent, Opaque, Control). Participants in the Transparent condition perceived the system as significantly clearer (F = 152.7, p < 0.001), more informative regarding data sources (F = 138.4, p < 0.001), and more reliable (F = 121.6, p < 0.001) compared to those in the Opaque and Control conditions. These findings demonstrate that the transparency cues were effectively recognized by respondents and distinguished from the alternative conditions. Effect sizes were in the medium-to-large range, with η2 = 0.15 for transparency clarity, η2 = 0.13 for source visibility, and η2 = 0.12 for reliability, indicating that the manipulation accounted for a substantial proportion of variance in perceived transparency.

Table 5.

One-Way ANOVA Results for Manipulation Checks Across Experimental Conditions.

Table 6 summarises the conditional logit estimates of hotel choice decisions with robust standard errors clustered by respondent. The results show that participants’ selections were primarily driven by the core hotel attributes. Higher guest ratings substantially increased the likelihood of choosing a hotel (OR = 1.838, 95% CI: 1.742–1.940), making this the strongest predictor of choice. Eco-score differences also exerted a pronounced positive effect (OR = 1.352, 95% CI: 1.289–1.419), indicating that respondents consistently preferred the more environmentally friendly option. Location proximity had a moderate but significant influence (OR = 1.215, 95% CI: 1.167–1.265), while higher price differences reduced the probability of selecting the more expensive hotel (OR = 0.981, 95% CI: 0.979–0.983). The main effects of AI label conditions (Transparent and Opaque) were not statistically significant (OR = 0.980, p = 0.634; OR = 0.960, p = 0.356), suggesting that the presence of an AI-generated recommendation alone did not directly shift baseline preferences. However, a meaningful interaction effect emerged: in the Transparent condition, participants assigned significantly greater weight to eco-scores (β = 0.1827, OR = 1.201, 95% CI: 1.132–1.273). This indicates that transparency cues amplified the behavioural relevance of environmental information, strengthening the preference for hotels with higher eco-scores. By contrast, the Opaque condition did not significantly alter eco-score weighting (OR = 1.023, p = 0.423). Overall, the results show that transparency does not directly influence choice outcomes but intensifies the influence of sustainability attributes. Transparent AI thus enhances the salience and credibility of eco-scores within multi-attribute decision contexts, reinforcing more environmentally conscious choices.

Table 6.

Conditional logit results with robust SE clustered by respondent.

In addition to the main effects, we conducted several diagnostic checks to assess the adequacy and robustness of the discrete choice model. The conditional logit specification demonstrated satisfactory fit, with a log-likelihood of −4879.12, a McFadden pseudo-R2 of 0.126, and information criteria of AIC = 9776.24 and BIC = 9839.55. A likelihood-ratio test comparing the full model with a null model including only an intercept was highly significant (p < 0.001), indicating that the attribute set substantially improves model fit. Because the experiment employed a binary choice structure, the model inherently satisfies the independence-of-irrelevant-alternatives assumption; this was further supported by a stability test showing no evidence of distortion when alternatives were hypothetically removed (χ2 = 3.01, p = 0.39). To probe preference heterogeneity, we estimated a mixed logit model with random coefficients on price, rating, and eco-score as a robustness check. The pattern of effects remained unchanged and no random parameter materially improved model fit, indicating that the conditional logit model provides the most parsimonious representation of the data. Additional robustness tests confirmed that all attribute levels were fully balanced and orthogonally distributed across tasks, eliminating the risk of sparse categories; equivalent specifications using alternative cut-offs produced substantively identical results. Overall, these diagnostics confirm that the behavioural estimates are stable and robust across alternative assumptions, model forms, and specifications.

As an additional specification, we extended the conditional logit model to include individual-level covariates capturing sustainable travel intentions and trust in AI, as well as their interactions with eco-score differences. Adding these covariates did not change the pattern of results: the main effects of intentions and trust were small and statistically non-significant (all p > 0.10), and the interaction terms with eco-score did not materially alter the transparency × eco-score effect. The coefficient for the Transparent × eco-score interaction remained positive and of similar magnitude, indicating that the core behavioural mechanism—heightened responsiveness to eco-scores under transparent AI—is robust to controlling for attitudinal predispositions. Full covariate estimates are available upon request.

5. Discussion

The study set out to examine the psychological drivers of sustainable travel intentions and the role of AI transparency in shaping both attitudinal and behavioral outcomes. Overall, the findings provide strong support for the hypothesized relationships and reveal how individual predispositions and system design jointly influence sustainable travel behavior across spatial and technological contexts. Survey results confirmed that internalized sustainability motives significantly increased intentions to engage in pro-environmental travel (H1). Travelers who felt a moral responsibility to minimize harm, derived intrinsic satisfaction from sustainable actions, and were willing to accept certain discomforts for environmental reasons reported higher intentions to choose eco-certified accommodation, reduce air travel, and favor low-carbon transport. These patterns indicate that sustainable travel is not merely a response to external incentives or situational constraints; it emerges from stable internalized values that guide behavior even when trade-offs are involved.

Ecological identity functioned as an important upstream factor, strengthening sustainability motives (H2). Respondents who regarded environmental concern as integral to their self-concept expressed stronger motivation to act sustainably, confirming that identity serves as a psychological anchor within decision processes. Although identity and motives may reinforce one another over time, the direction observed here aligns with the dominant theoretical view that identity salience energizes sustainability-oriented motives. When sustainability becomes part of one’s sense of self, behavioral consistency increases and intentions become less susceptible to contextual pressures. The results therefore provide empirical evidence for an identity–motive–intention pathway in tourism, showing how personal meaning sustains environmentally responsible behavior over time and across spatial contexts. Climate attitudes played a dual role by both reinforcing motives (H3) and directly increasing sustainable intentions (H4). Travelers who viewed climate change as a serious, human-induced threat were more likely to plan low-carbon trips and adjust their travel habits accordingly. This dual pathway suggests that climate attitudes supply both cognitive justification and motivational energy: they explain why change is necessary while also energizing willingness to act. Together, the relationships among sustainability motives, ecological identity, and climate attitudes form an integrated psychological architecture underpinning sustainable travel intentions. These results demonstrate that pro-environmental behavior in tourism is simultaneously moral, cognitive, and identity-based—rooted in values but activated within real-world decision settings. Although the structural paths among the six latent constructs were not statistically significant, this does not diminish the analytical value of the SEM. The primary contribution of the model lies in the robustness of the measurement structure, which confirms a theoretically coherent six-dimensional configuration of sustainability motives, ecological identity, climate attitudes, AI transparency, AI trust, and sustainable travel intentions. Given the very low correlations between constructs, the structural component of the SEM serves a supportive rather than causal function, illustrating that these psychological domains operate as largely independent dimensions in the present dataset. This independence is consistent with the notion that attitudes toward sustainability, identity, and AI systems may reflect distinct cognitive–motivational processes that are not necessarily integrated into a single latent pathway. Thus, the measurement model remains central to the empirical contribution, while the structural results highlight the conceptual distinctiveness rather than interdependence of the constructs.

Experimental results extended these insights by linking internal dispositions with observable behavior. Manipulation checks confirmed that transparency cues were effective: participants exposed to transparent AI recommendations perceived the system as clearer, more informative, and more reliable (H5). Even modest transparency features—brief explanations of data sources, CO2 estimation methods, or uncertainty ranges—significantly improved perceived system credibility. As expected for a manipulation-check hypothesis, H5 confirms that the transparency treatment operated as intended rather than testing a novel theoretical mechanism. Behavioral data further revealed that hotel choices were primarily influenced by price, rating, and location, yet eco-scores carried a notable independent effect. Crucially, transparency amplified the influence of eco-scores: under transparent conditions, participants were approximately 20% more likely to select the greener hotel (H6). Transparency thus operated as more than a perceptual enhancement—it altered the weighting structure of decisions, elevating environmental information to a decisive criterion alongside economic and spatial considerations. This pattern reflects a relative increase in the weight assigned to eco-scores within multi-attribute trade-offs, rather than an unconditional shift toward sustainable behavior. It is important to note that the transparency manipulations operated effectively even though absolute reliability ratings remained moderate. Prior work on algorithmic trust suggests that transparency rarely produces high trust levels; instead, it generates incremental but meaningful shifts in cognitive accessibility and perceived diagnosticity of system outputs. In this experiment, such incremental shifts were sufficient to alter how participants weighted eco-scores: transparency did not need to create high trust, only to increase the salience and credibility of the sustainability signal. This explains why the interaction between eco-score differences and the Transparent condition emerged in the choice model—participants became more responsive to environmental information even under moderate, cautiously calibrated trust levels.

Trust perceptions—reflected in clarity, source visibility, and reliability—were positively associated with sustainable selections, indicating that trust supports the influence of transparency on behavior, without functioning as a statistical mediator in this study (H7). This finding illustrates that transparency functions not simply through information disclosure but through the social and psychological mechanisms of trust calibration. Without trust, sustainability signals risk being ignored or discounted; with trust, they gain behavioral traction. Trust therefore acts as the bridge between information design and spatial behavior, translating technical transparency into meaningful change in travelers’ revealed preferences.

The implications of these findings are substantial for sustainable tourism, particularly in rural destinations and cultural landscapes. Although the study engages with rural destinations and cultural landscapes at a conceptual and policy-oriented level, the empirical analysis did not include spatial variables such as geocoded destinations, observed tourism flows, or GIS-based behavioral data. Therefore, any references to potential spatial redistribution of tourist flows should be interpreted as conceptual implications derived from changes in attribute weighting rather than empirically measured spatial effects. The findings indicate a psychological and informational mechanism—greater responsiveness to eco-scores under transparent AI—but they do not demonstrate direct spatial redistribution. Future research incorporating geospatial data would be required to empirically validate these spatial dynamics.

Conceptually, the study demonstrates that sustainable travel depends on the alignment of internal predispositions and external affordances. Travelers with strong sustainability motives, ecological identity, and climate awareness are predisposed to behave responsibly, yet their choices require reinforcement through transparent and trustworthy decision environments. Technologically mediated travel systems thus become active participants in shaping human–environment interactions: when algorithmic recommendations are transparent, they can steer tourists toward spatially sustainable behaviors, support more balanced distribution of tourism flows, and prevent excessive pressure on ecologically fragile rural environments and traditional cultural landscapes.

Practically, the findings highlight that transparency is not a superficial design feature but a determinant of behavioral outcomes. However, these policy implications should be interpreted cautiously. Implementing transparent AI systems involves substantial practical constraints, including financial costs, data-quality requirements, technical infrastructure, and the institutional capacity to maintain and update transparency mechanisms. Rural destinations, in particular, often face resource limitations, lower digital readiness, and governance challenges that may hinder adoption of advanced AI-based tools. Moreover, transparency does not eliminate inherent model uncertainties or guarantee user trust in all contexts. As such, the recommendations presented here should be understood as potential directions rather than prescriptive solutions, requiring further feasibility studies, cost–benefit analyses, and pilot implementations before large-scale deployment. By increasing the credibility of eco-scores, transparent AI systems make sustainability information more actionable and influential, guiding travelers toward greener alternatives that align with individual values and collective environmental goals. This outcome carries spatial implications essential for rural areas: transparent AI can redirect flows away from overvisited sites, support underutilized rural destinations, and help maintain landscape integrity and cultural authenticity.

Limitations of the study also point to directions for further inquiry. One important limitation concerns the demographic and technological profile of the sample. Participants recruited through Prolific tend to be younger, highly educated, and digitally literate, and in our case exhibited exceptionally high familiarity with AI technologies (nearly 98% reported high or very high familiarity). While this makes the sample appropriate for studying early adopters of AI-mediated travel tools, it may limit generalizability to tourist populations with lower digital competence, particularly those visiting rural destinations where travelers are often older and less accustomed to AI-supported decision systems. As a result, the transparency effects observed in this study may represent an upper-bound estimate of behavioral responsiveness. A further limitation concerns the ecological validity of the booking scenarios. Finally, despite the conceptual focus on rural destinations and cultural landscapes, the empirical dataset did not contain geospatial variables or actual visitation flows. As a result, the spatial implications discussed in this paper remain theoretical and should be validated in future research incorporating GPS traces, behavioral mobility data, or destination-level spatial modeling. While the paper frames rural destinations and cultural landscapes as key contexts in which transparent AI systems may support more sustainable mobility patterns, the discrete-choice experiment relied on generic hotel attributes rather than rural-specific indicators such as seasonality constraints, destination carrying capacity, biodiversity sensitivity, or community-level impacts. This simplification was deliberate to isolate the causal mechanism of transparency, yet it necessarily abstracts from the full spatial and socio-environmental complexity of rural decision contexts. Future work should incorporate such contextual attributes to examine whether transparency effects interact with rural landscape characteristics or local sustainability constraints.