1. Introduction

Road traffic accidents (RTAs) remain a major global public health and economic challenge, causing around 1.19 million deaths and up to 50 million injuries annually, many resulting in permanent disabilities [

1]. Although leading road-safety organisations increasingly recommend the terms “crash” or “collision” to emphasise preventability, the term “accident” continues to be widely used in the European scientific literature and in official Portuguese statistics, including reports from the National Authority for Road Safety (ANSR). In this manuscript, the term is retained to ensure consistency with national data sources and with the terminology adopted in related studies. Nonetheless, it is acknowledged that most road traffic events are not random or unavoidable: they often arise from a sequence of preventable human, environmental, or infrastructural factors. In Portugal, the National Authority for Road Safety (ANSR) reported 477 fatalities in 2024 [

2], with the socioeconomic impact of road crashes estimated at nearly 3% of the national GDP [

3]. Beyond the immediate human loss, severe accidents impose long-term consequences such as productivity reduction, post-traumatic effects, and strain on healthcare systems [

4], reinforcing the importance of data-driven strategies for prevention and resource optimization [

5].

The growing availability of digital accident records and advances in Artificial Intelligence (AI) have created new opportunities for understanding and preventing RTAs. Traditional statistical approaches, such as linear and logistic regression, though valuable, struggle to capture the complex non-linear relationships between environmental, temporal, and human factors [

6]. In contrast, classical Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) models, including Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, and Deep Neural Networks (DNN), can process large heterogeneous datasets and identify hidden patterns that enhance predictive accuracy [

7,

8,

9].

However, challenges such as class imbalance, where severe or fatal crashes are underrepresented, and the need for interpretable and generalizable models remain major obstacles to practical deployment. These limitations motivate the present study, which applies Machine Learning and Deep Learning approaches to predict accident severity using real data from the Portuguese Guarda Nacional Republicana (GNR), covering the years 2019–2023 and including diverse environmental, temporal, and situational features. The results show that deep learning architectures, particularly DNNs combined with class weighting, achieved the best balance between sensitivity and overall performance. In this context, sensitivity refers to the model’s ability to correctly identify severe and fatal crashes (minority classes). The DNN model achieved higher recall for severe classes compared with tree-based models, while maintaining stable accuracy across all categories, demonstrating its capacity to detect critical crash patterns more effectively. Among the analyzed variables, lighting conditions emerged as one of the strongest predictors of accident severity, indicating that low visibility substantially increases the risk of serious or fatal crashes. These findings suggest that law enforcement agencies, such as the GNR, can benefit from predictive models that support targeted interventions, such as adjusting patrol schedules and improving lighting conditions in high-risk areas.

In summary, this study contributes to the growing field of AI-driven road safety by demonstrating the comparative performance of classical ML and DL models under different class-balancing strategies, establishing class weighting as the most effective approach for addressing imbalance, and highlighting lighting conditions as a key determinant of accident severity. By leveraging real-world law enforcement data, this research provides a methodological framework that can support data-informed decision-making, resource allocation, and the development of proactive road safety policies in Portugal.

In addition, the source code developed for this project has been made publicly available, representing a valuable contribution to the state of the art (see

Appendix A).

3. Materials and Methods

This section describes the dataset, preprocessing steps, model architectures, and evaluation metrics used in this study. First, we provide an overview of the data source and its characteristics, followed by the methods employed to prepare the data for analysis, address class imbalance, and implement predictive models. Finally, the metrics used to evaluate model performance are outlined.

3.1. Data Source and Description

The dataset used in this study was provided by the GNR and contains all road traffic accidents (RTAs) recorded between 2019 and 2023 on roads under GNR jurisdiction, which comprises approximately 94% of Portugal’s national territory [

23]. Each record includes contextual and situational variables such as date, time, location, weather conditions, road surface, lighting conditions, accident nature and type, and accident severity. After preprocessing, the dataset comprised approximately 330,000 valid entries. Severe accidents (classified as fatalities or serious injuries) accounted for less than 5% of all records, reflecting the natural imbalance typical of real-world accident data.

Road safety indicators in 2020 were strongly influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic [

24]. The mobility restrictions implemented during lockdown phases resulted in a marked reduction in road usage and, consequently, exposure to accident risk. According to the Portuguese National Road Safety Authority (ANSR), ref. [

25] road fuel consumption, (used as a proxy for kilometres travelled), decreased by approximately 14.4% in 2020 compared to 2019.

As this phenomenon introduced atypical temporal behaviour into the dataset, these effects were taken into account during interpretation. Nonetheless, rather than removing pandemic-year data, which could introduce temporal bias, these records were retained to preserve chronological continuity. Data cleaning focused only on objectively verifiable issues, namely the removal of entries with missing severity classification, invalid location identifiers, or incomplete timestamp fields.

3.2. Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

Prior to model training, the dataset underwent several preprocessing steps to ensure data quality and compatibility with machine learning algorithms. Missing values were first addressed, since incomplete records can bias the learning process and reduce model performance. Depending on the feature type, missing entries were either imputed with statistical measures (such as the mean or mode) or removed when the amount of missing data was negligible. This ensured that no invalid or incomplete samples were passed to the training stage.

Irrelevant or redundant columns were then removed to reduce noise and dimensionality, retaining only features with meaningful predictive power.

A key step was the transformation of categorical variables into numerical representations through One-hot encoding. Many ML algorithms, such as Random Forest and XGBoost, require numerical inputs and cannot process raw categorical labels directly. One-hot encoding addresses this issue by converting each category into a binary vector in which all components are zero except for a single index corresponding to the observed category. For example, if a variable

x takes values from the set

, then

a,

b, and

c are encoded as

,

, and

, respectively [

5]. This approach avoids the introduction of artificial ordinal relationships between categories, which could otherwise mislead the learning process.

Temporal information was also simplified to reduce dimensionality and improve model efficiency. Fine-grained time components such as seconds, minutes, and days were removed, as encoding them would result in an excessive number of features after one-hot encoding, leading to a highly sparse and computationally expensive dataset. Instead, the temporal structure was aggregated at the monthly level, extracting only the year and month (Date_Year and Date_Month) from each record. This approach preserved relevant seasonal and yearly trends in accident severity while preventing the combinatorial explosion of features associated with more granular temporal variables.

In addition, continuous features were normalized where necessary to ensure that they contributed proportionally during model training, particularly for models sensitive to feature scaling such as neural networks. Finally, the dataset was split into training and testing subsets to allow for unbiased performance evaluation.

The overall methodological framework followed in this study is illustrated in

Figure 1.

3.3. Addressing Class Imbalance

Road traffic accident datasets are inherently imbalanced, as severe or fatal accidents account for only a small fraction of the total records. To mitigate this issue and improve model sensitivity to critical cases, three data balancing strategies were employed: Class Weighting, Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE), and Random Undersampling (RUS). Each method was tested independently to assess its impact on predictive performance.

3.3.1. Class Weighting

Class weighting adjusts the loss function during model training to give more importance to minority classes, thereby penalizing misclassifications of severe accidents more heavily than those of majority classes. The weights for each class were calculated inversely proportional to the class frequencies using the formula:

where:

is the weight for class i,

N is the total number of samples in the dataset,

is the number of samples in class i,

is a hyperparameter controlling the magnitude of the weights.

To calibrate the class-weighting exponent

, a small-scale sensitivity analysis was conducted using a reduced dataset, in order to save processing time,

. Lower values (e.g.,

–

) produced insufficient penalization of severe-accident classes, leading to unstable recall and a strong bias toward majority outcomes. Conversely, higher values (

–

) excessively amplified minority-class loss, causing overfitting and degraded overall G-Mean. The intermediate value

consistently provided the most stable trade-off between minority-class recall and global performance across models, avoiding both under-weighting and over-weighting effects. This choice is aligned with the effective-range recommendations observed in prior imbalance-learning literature [

26,

27], while remaining computationally feasible under the hardware constraints of this study.

3.3.2. SMOTE and Random Undersampling

SMOTE generates synthetic samples for minority classes by interpolating between existing instances, helping to increase their representation in the training dataset [

6]. Conversely, Random Undersampling (RUS) reduces the number of majority-class samples until class proportions are balanced. These methods complement class weighting by providing alternative ways to address imbalance, allowing the models to better learn from critical but scarce events.

3.4. Model Architectures

Four machine learning models were selected to address the problem of road accident severity prediction: Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), and Deep Neural Network (DNN). The choice of these models reflects a balance between interpretability, robustness to data imbalance, and predictive capacity across structured tabular datasets.

Random Forest is an ensemble learning method based on decision trees that combines multiple classifiers to reduce overfitting and improve generalization performance. It has been widely applied in traffic accident prediction tasks due to its robustness to noisy data and its ability to handle nonlinear feature interactions [

7,

9,

13]. RF also provides feature importance measures, allowing for interpretability, which is crucial in safety-related contexts. However, its main limitations include increased computational complexity with large datasets and a tendency to produce less smooth decision boundaries compared to gradient boosting approaches [

28].

XGBoost, or Extreme Gradient Boosting, extends gradient boosting by introducing regularization and efficient parallelization, leading to superior accuracy and faster convergence compared to traditional tree ensembles [

8]. XGBoost has demonstrated strong performance in imbalanced data environments typical of crash-severity prediction tasks [

28]. Nonetheless, its disadvantages include sensitivity to hyperparameter tuning and the potential to overfit if regularization is not properly configured.

Multilayer Perceptron represents a class of feed-forward neural networks capable of modeling complex nonlinear relationships among crash-related features. MLPs are computationally efficient and adaptable for classification problems with multidimensional input features [

29]. However, they are highly sensitive to initialization, architecture depth, and learning rate, which can lead to unstable training behavior and suboptimal performance on small or imbalanced datasets [

30].

Deep Neural Networks generalize MLPs by incorporating additional hidden layers and activation functions, allowing for the extraction of hierarchical feature representations. In transportation research, DNNs have shown high predictive accuracy in crash severity modeling and driver injury analysis [

12,

15]. Despite these advantages, DNNs require large, well-balanced datasets to achieve optimal generalization and are computationally intensive, often necessitating extensive hyperparameter optimization and GPU acceleration [

30].

In summary, Random Forest and XGBoost were chosen for their interpretability and robustness on tabular and imbalanced datasets, while MLP and DNN were included to explore the potential of deep learning architectures in identifying complex patterns underlying road accident severity.

3.5. Evaluation Metrics

Model performance was assessed using metrics suitable for imbalanced datasets, namely Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and the Geometric Mean (G-Mean). These measures provide a balanced view of predictive capability across both majority and minority classes, focusing particularly on the correct identification of severe accidents.

Precision measures the proportion of correctly predicted positive cases among all predicted positives:

Recall quantifies the model’s ability to correctly identify actual positive (severe) cases:

Specificity evaluates how well the model identifies negative (non-severe) cases, avoiding false alarms:

F1-Score represents the harmonic mean of precision and recall, balancing false positives and false negatives:

G-Mean combines recall and specificity to ensure consistent performance across both minority and majority classes:

Accuracy was not used, as it can be misleading in imbalanced datasets dominated by non-severe accidents. Confusion matrices were also examined to analyse class-specific performance, with particular attention to false negatives, cases where severe accidents were misclassified as less severe, due to their critical operational implications for timely response and resource allocation.

4. Results

The primary goal of this research was to implement classical Machine Learning and Deep Learning algorithms to support Law Enforcement Agencies (LEAs) in optimizing patrol resource allocation and reducing the risk of severe road traffic accidents. This section presents the experimental findings derived from the dataset provided by the GNR, covering road accidents between 2019 and 2023. The discussion focuses on model performance, class imbalance handling, and the implications of the results for operational decision-making.

4.1. Dataset Overview and Preprocessing

The dataset used in this study comprises detailed road traffic accident (RTA) reports collected by the GNR between 2019 and 2023 on roads under its jurisdiction. Each record includes temporal, spatial, and environmental variables such as date and time, location, weather, lighting conditions, road type, and accident nature. Records were carefully cleaned, irrelevant or inconsistent columns removed, and categorical variables were one-hot encoded to ensure compatibility with the machine learning and deep learning models. The final dataset contained over 300,000 valid entries.

Accidents were categorized into four severity levels:

0: Material damage only

1: Minor injuries

2: Severe injuries

3: Fatalities

A significant class imbalance was observed, with minor and material-damage accidents (classes 0 and 1) greatly outnumbering severe or fatal cases (classes 2 and 3). To address this issue, three data balancing strategies were applied, Class Weighting, Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) and Random Undersampling (RUS).

The dataset was divided into training (80%) and testing (20%) subsets using a stratified split to preserve proportional class distributions.

Spatially, the data revealed clear geographic patterns in accident occurrence. The heatmap presented in

Figure 2 visualizes the density of recorded accidents per square kilometer across the five-year period (2019–2023). Lighter tones (0–5 accidents/km

2) correspond to rural or sparsely populated regions, whereas darker tones (35–45 accidents/km

2) indicate high-incidence areas. Accidents were most concentrated in the northern coastal districts, namely Porto, Braga, and Aveiro, as well as within the Lisbon metropolitan area, which aligns with regions of higher population density and traffic exposure. Conversely, the interior regions such as Guarda, Portalegre, and Beja exhibited lower densities, reflecting reduced mobility and lighter traffic volumes.

These spatial variations illustrate how population density, infrastructure, and traffic intensity influence accident distribution. However, spatial density alone cannot fully explain accident severity or causality. Therefore, the integration of additional environmental and behavioral variables, such as lighting, atmospheric conditions, and probable causes, were essential to enhance model interpretability and predictive performance.

4.2. Feature Analysis

A comprehensive summary of the categorical features included in the dataset is presented in

Table 2. Each attribute captures key contextual and situational information relevant to accident severity prediction, encompassing environmental, temporal, behavioral, and infrastructural dimensions. These variables provide the foundation for understanding accident dynamics and for developing predictive models capable of identifying high-risk scenarios.

The correlation matrix in

Figure 3 reflects the relationships among the cleaned set of input features used for model training. It is important to note that the variable

Accident Type exists in the original dataset but was not included as an input feature. Instead, it served as an intermediate attribute used solely to construct the final

Severity target variable. For this reason,

Accident Type was removed from the feature set and is not represented in the correlation matrix.

Among the correlations observed, the strongest association is between Road Type and Location (0.37). This reflects the structural logic of Portugal’s road network: highways, main itineraries, and national roads are predominantly located outside urban centres, while municipal and regional roads are more common within localities. Such a pattern naturally generates a moderate spatial–infrastructural relationship.

Several weaker correlations also provide meaningful insights. For example, Probable Cause shows a mild positive correlation with both Accident Nature (0.20) and Atmospheric Factors (0.12), which is consistent with real-world expectations: certain causes—such as distraction or unexpected obstacles are more likely under adverse weather conditions or in particular accident configurations. Similarly, the correlation between Accident Nature and Lighting Conditions (0.13) highlights that some accident categories (e.g., pedestrian collisions) tend to occur more frequently under low-visibility scenarios.

The correlation between Probable Cause and Location (0.11) also aligns with practical experience: rural areas tend to present specific risk factors (e.g., animal crossings or speed-related incidents), whereas urban zones more commonly involve side-impact collisions or pedestrian accidents. Conversely, several variable pairs show little or no linear relationship. For instance, the correlation between Road Type and Probable Cause is effectively null (0.00), suggesting that causes of accidents are widely distributed across road categories, despite intuitive expectations that certain road types might predispose specific risks. The correlation between District and Location is similarly weak (0.06), indicating that regional boundaries do not substantially influence whether an accident occurs inside or outside localities. Taken together, these correlation patterns show that, beyond a few structurally expected relationships, the dataset does not exhibit strong multicollinearity.

4.3. Model Implementation

Four models were implemented: Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), and Deep Neural Network (DNN). Each model was trained using the same preprocessed data and evaluated across different balancing techniques. The evaluation metrics included F1-score, Recall, and G-Mean to assess both predictive performance and robustness to class imbalance.

4.4. Model Comparison and Discussion

The models were trained using four different imbalance-handling approaches (Original, Class Weighting, RUS, and SMOTE). Their macro-level performance is summarised in

Table 3, while the corresponding class-wise F1-score and Recall values are provided in

Table 4. Together, these two tables allow for a detailed comparison of how each balancing technique affects not only overall performance but also the detection capability for each severity class—particularly the minority classes (2 and 3).

The micro-class analysis reveals that nearly all models achieve near-perfect performance for classes 0 and 1 across all balancing techniques, confirming that majority classes dominate the learning process in highly imbalanced datasets. However, large differences arise in the behaviour of models when predicting severe (class 2) and fatal (class 3) accidents, which are the most relevant for operational decision-making but also the hardest to detect.

Notably, the class-weighting strategy significantly improved recall for minority classes in both neural-network architectures (MLP and DNN), while Random Forest and XGBoost benefited more from RUS. These findings underscore the importance of matching the balancing strategy to the model family rather than relying on a one-size-fits-all solution.

The main observations from the experiments are as follows:

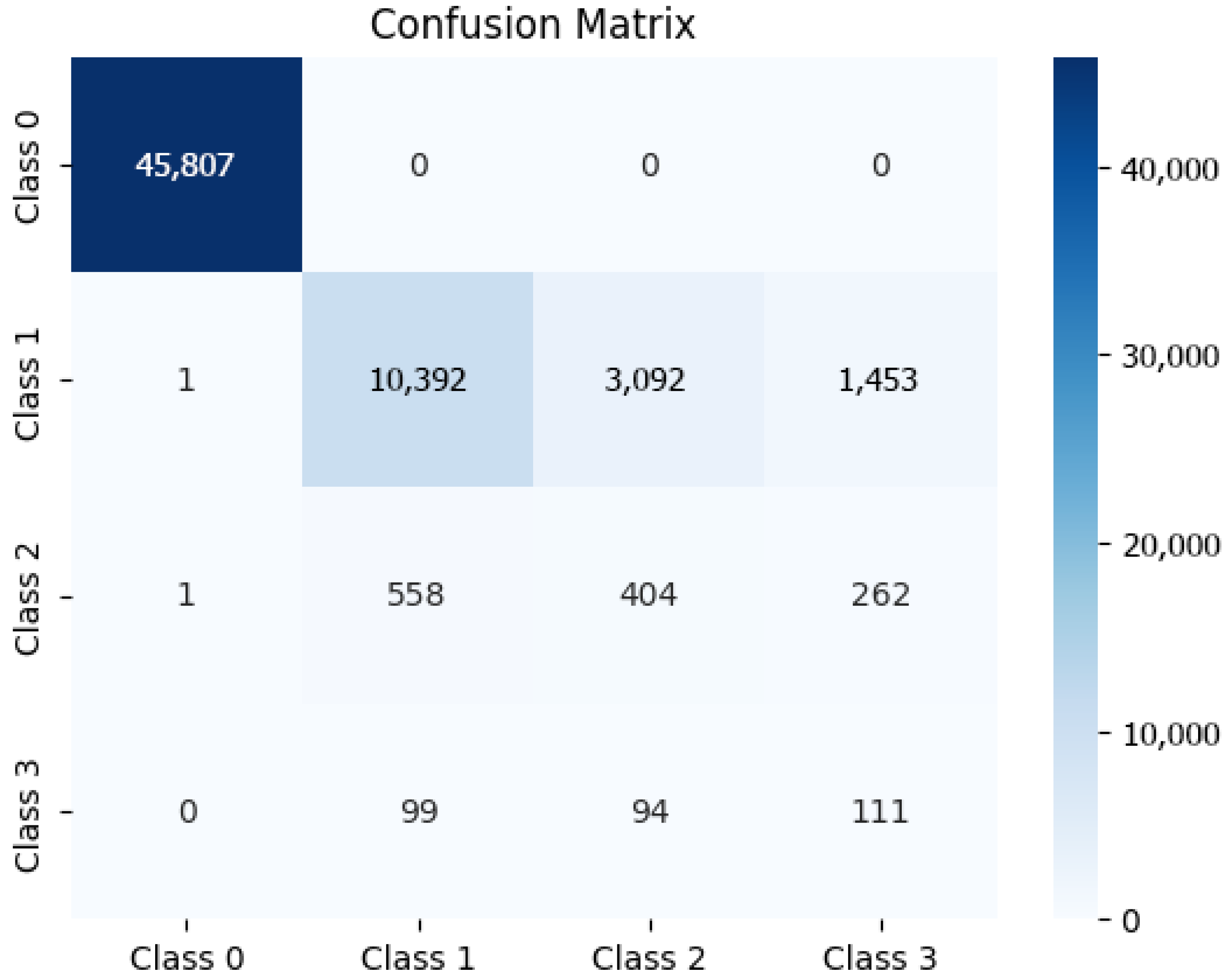

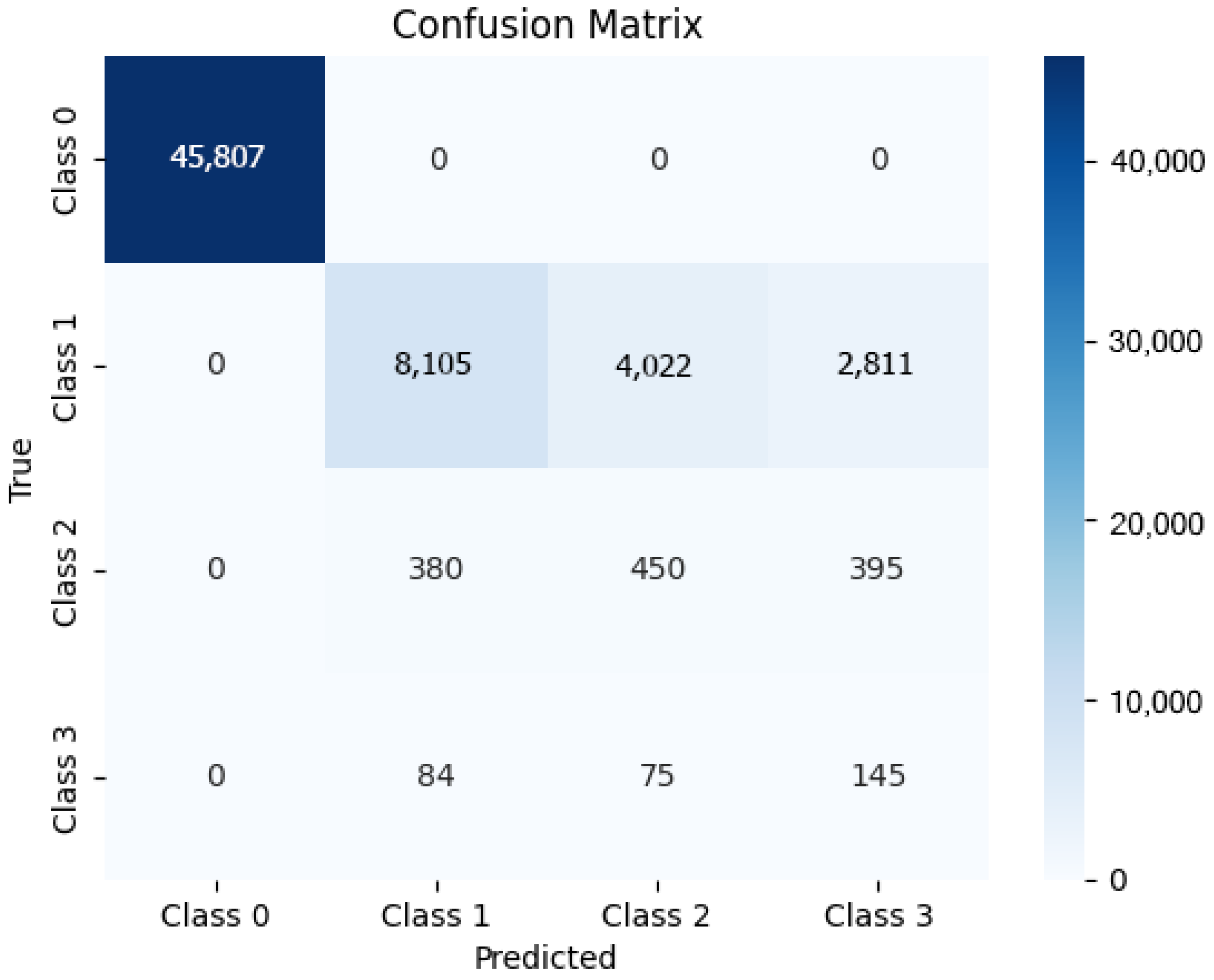

Random Forest: Despite its structural robustness, Random Forest struggled to recognise minority classes under severe imbalance. Its best performance was obtained with RUS (G-Mean = 0.53), which increased recall for severe and fatal accidents, though at the cost of discarding a large proportion of majority-class samples. The micro-class metrics show that class-weighting provided only marginal gains for RF, suggesting that tree-based ensembles are less sensitive to loss reweighting compared to neural models.

XGBoost: XGBoost exhibited slightly higher stability than RF, also achieving its best results with RUS (G-Mean = 0.54). Class-weighting produced moderate improvements, particularly for classes 2 and 3, but remained insufficient for high-severity detection. The behaviour of XGBoost reinforces that boosting algorithms, although powerful still require substantial restructuring of the data distribution to effectively learn minority-class boundaries.

MLP: The MLP showed considerable gains with class weighting (G-Mean = 0.54, Recall = 0.59). This improvement is visible in the micro metrics, where class-weighted MLP increases Recall for class 2 from 0.00 to 0.15 and for class 3 from 0.00 to 0.25, outperforming tree-based models under the same conditions. This demonstrates that shallow neural networks adapt effectively when guided by an imbalance-aware loss.

DNN: The deep neural network achieved the best overall recall (0.60) when combined with class weighting, confirming its ability to extract hierarchical representations beneficial for complex classification tasks. The minority-class recall improvements for weighted DNN mirror those of the weighted MLP but with slightly superior stability, indicating that deeper architectures enhance the model’s capacity to learn subtle patterns in heterogeneous traffic-accident data.

Although RUS produced higher G-Mean values for RF and XGBoost, this came with a significant reduction in majority-class information, potentially harming generalisation. In contrast, class weighting preserved the full dataset and consistently improved the performance of neural models, which achieved the best overall results: MLP reached the highest G-Mean (0.54) and DNN reached the highest Recall (0.60).

The micro-class analysis confirms this trend: only class weighting produces meaningful recall for severe and fatal classes in deep models without sacrificing performance in majority classes. This reinforces class weighting as the most reliable and stable strategy when the goal is to detect high-severity accidents, which are operationally the most critical for law enforcement and emergency management.

In summary, while no single technique universally outperformed the others, class weighting demonstrated the strongest balance sensitivity to minority classes, particularly for complex architectures capable of hierarchical feature extraction. It therefore emerges as the most suitable approach for real-world applications where the early detection of severe and fatal accidents is essential.

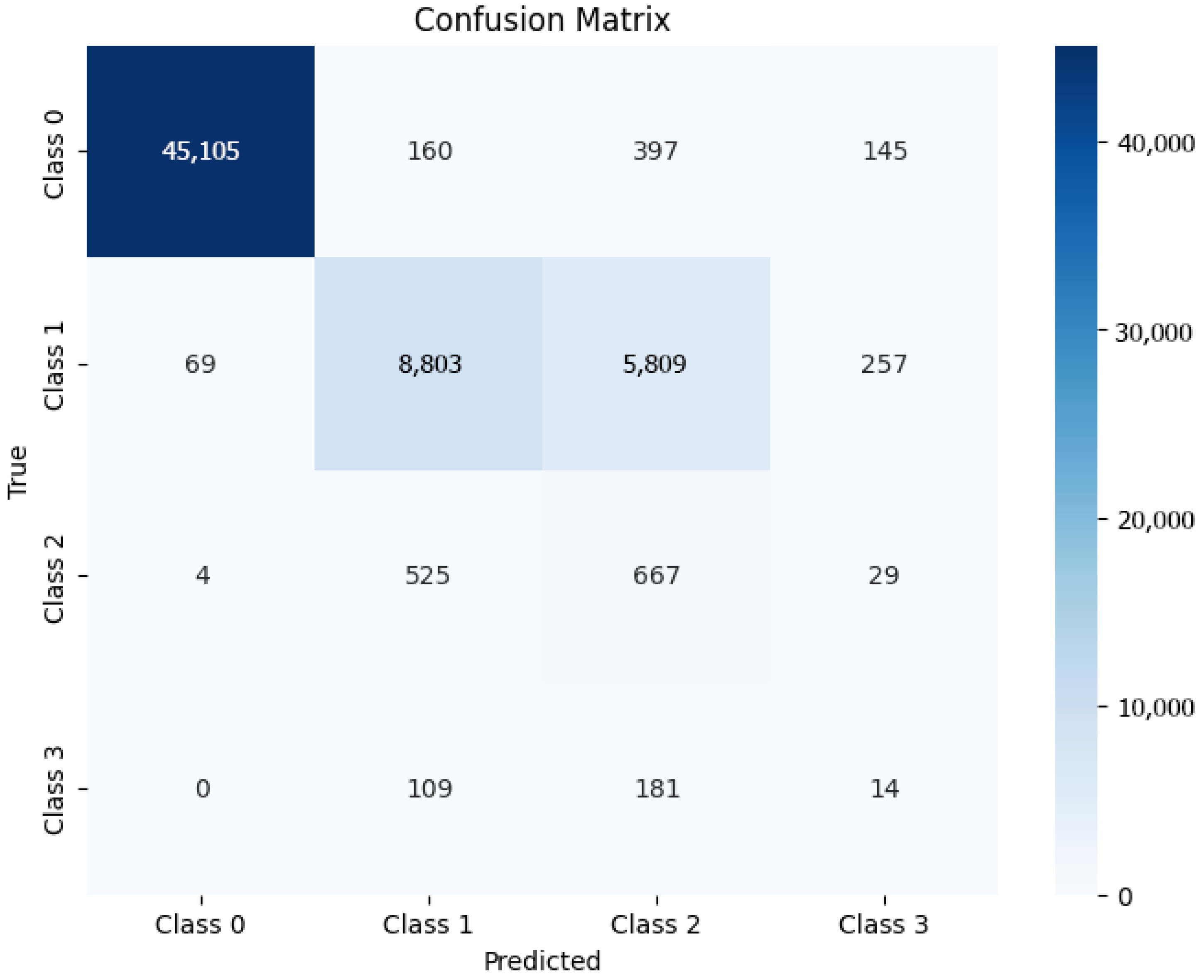

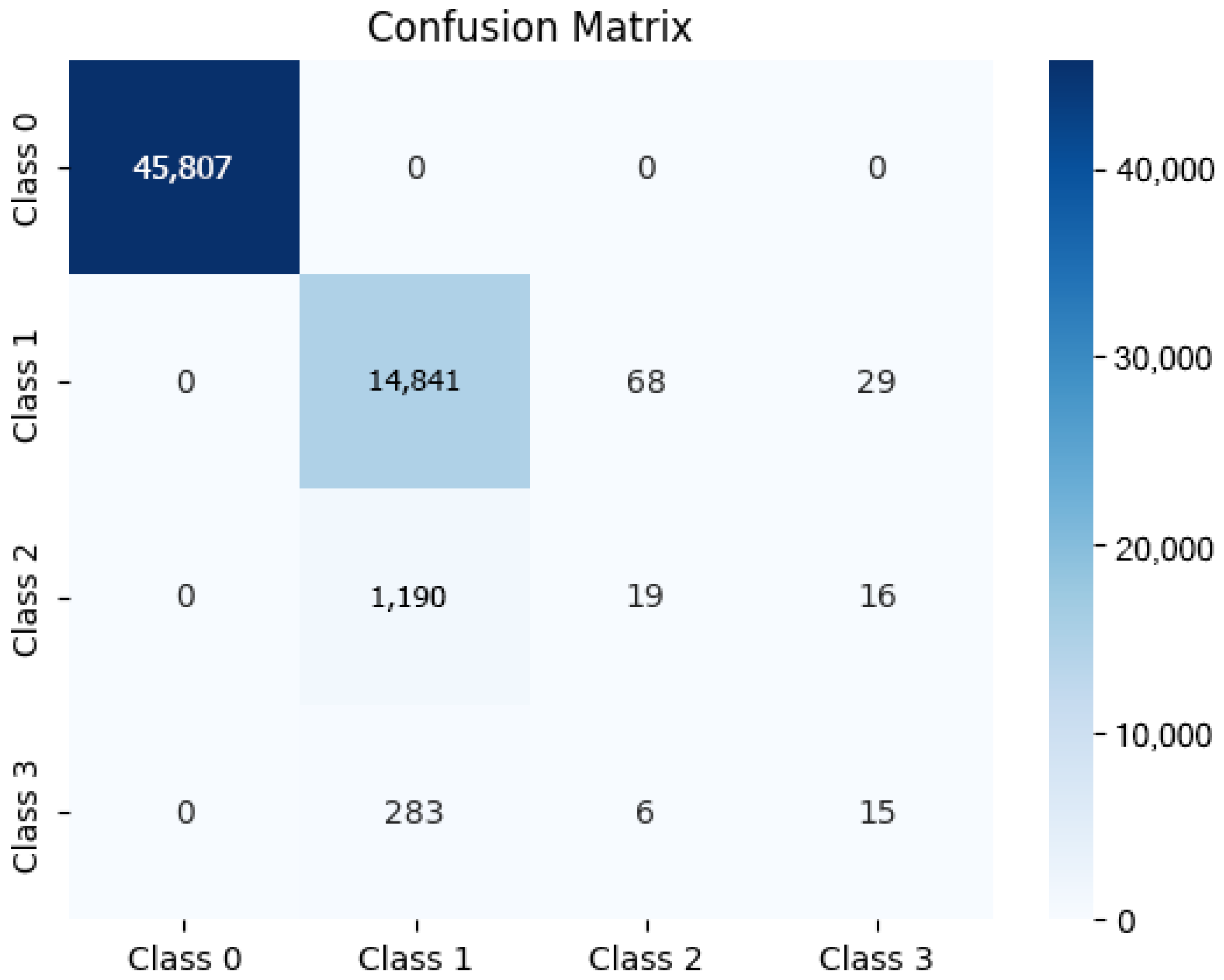

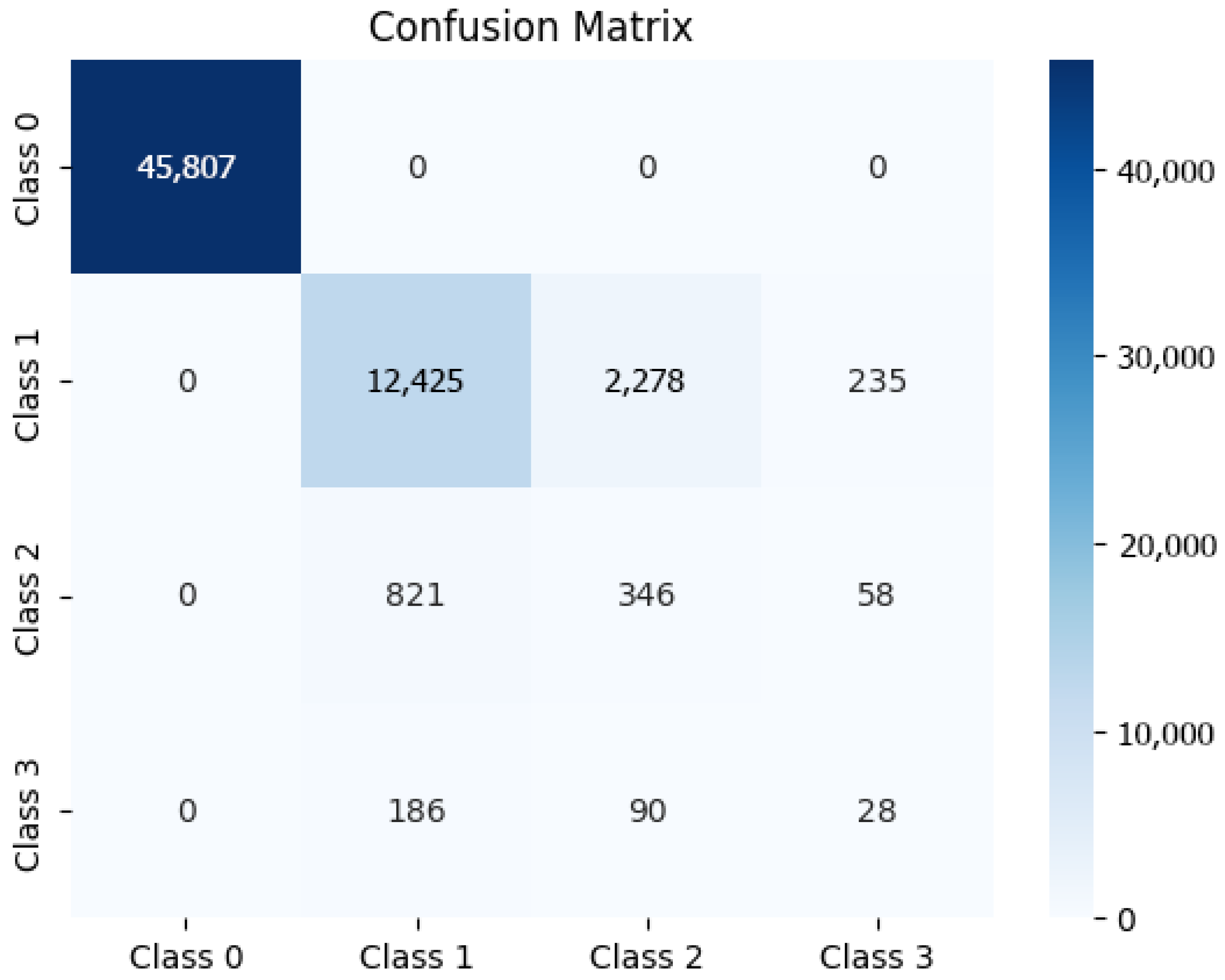

4.5. Confusion Matrix Analysis

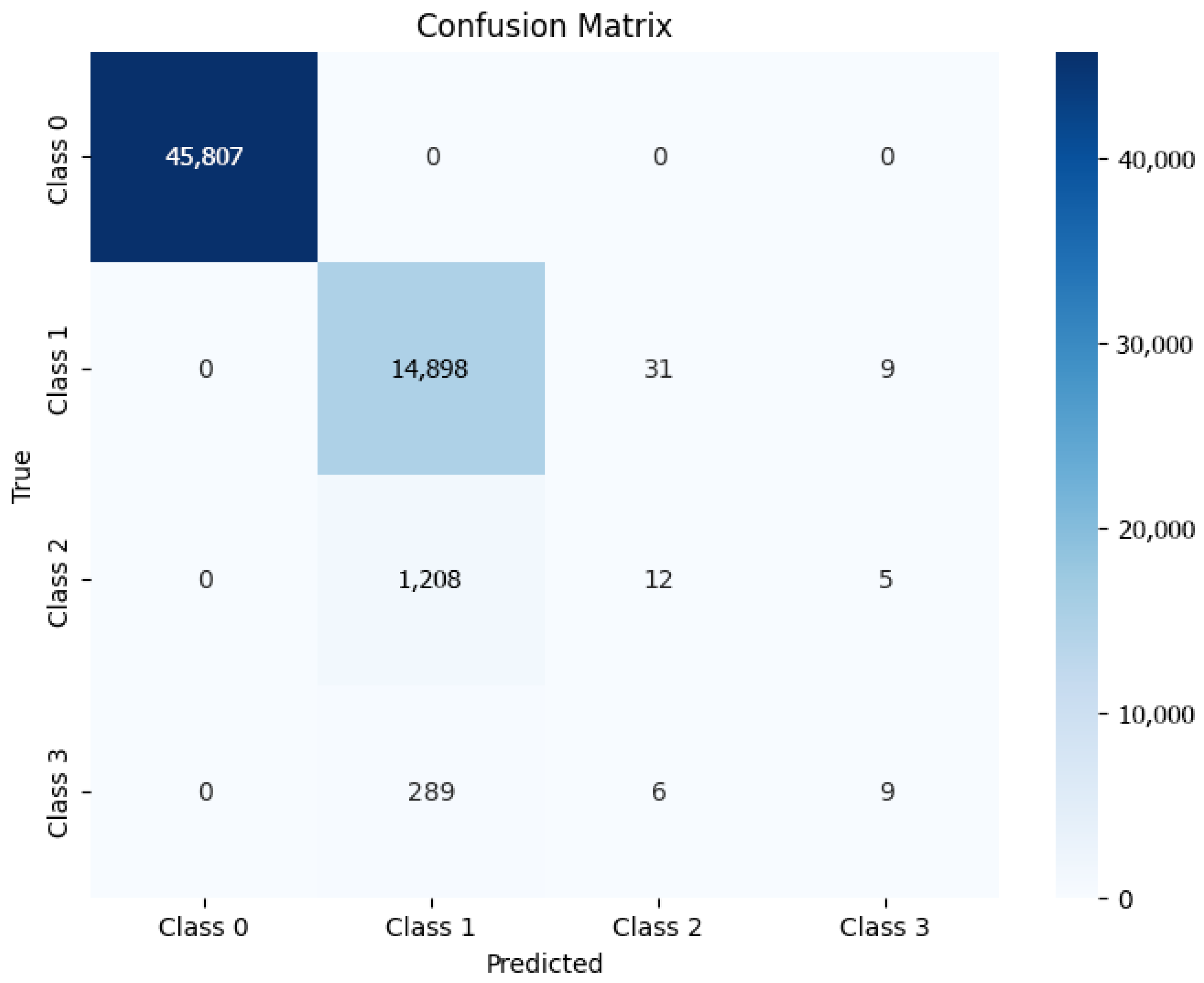

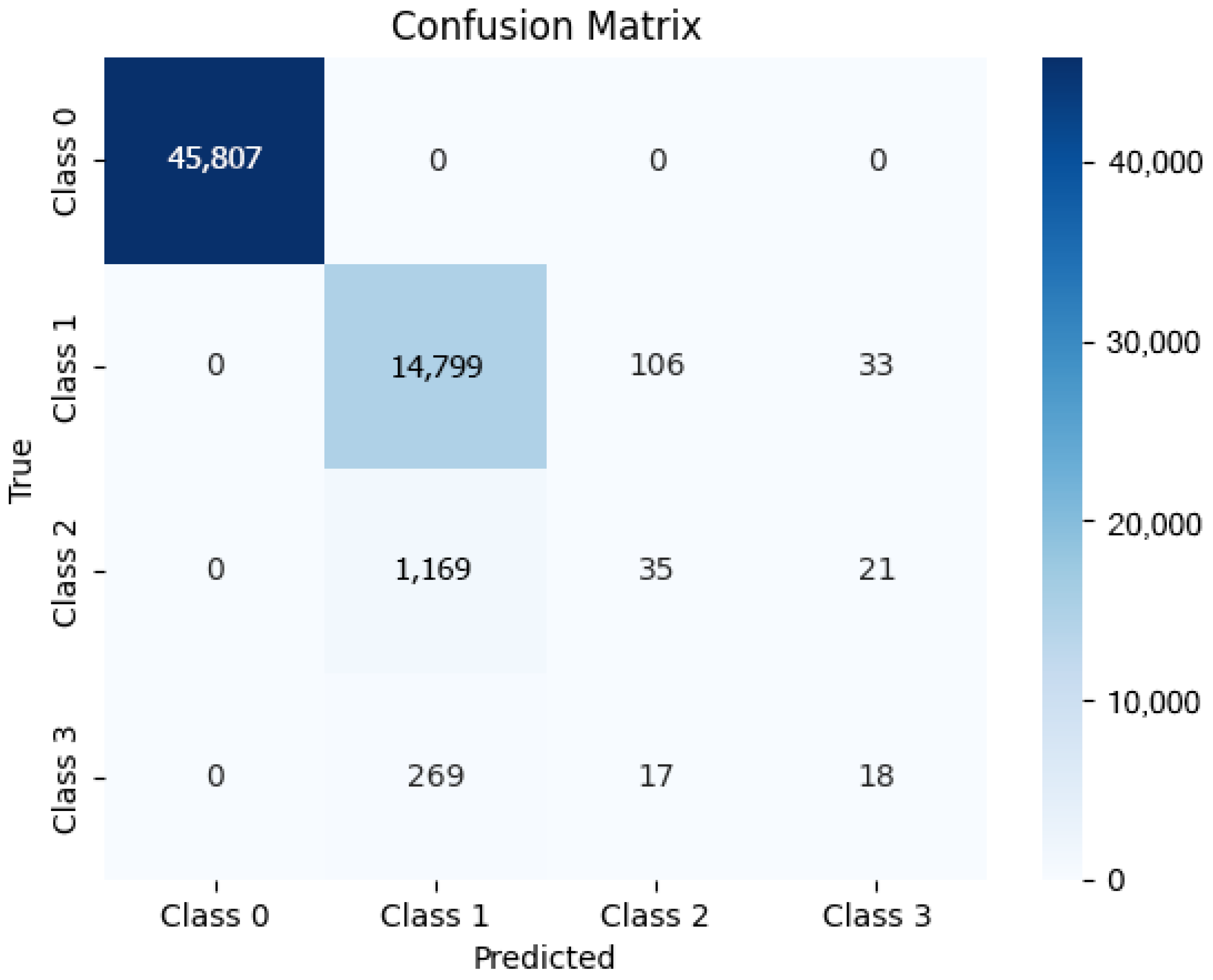

Across all models and balancing strategies, confusion matrices (see

Appendix B) confirmed that the models effectively predicted non-severe accidents but often misclassified severe ones. This conclusion was derived from the distribution of true negatives and false negatives across all configurations, where the majority of correctly classified cases corresponded to class 0 (property damage only), while classes 2 and 3 (hospitalization and fatality) showed lower recall values and higher misclassification rates.

Weighted DNN and MLP configurations showed the highest number of correctly classified severe accidents, as evidenced by higher recall values (0.60) and G-Mean scores (0.53) compared to other models. These metrics suggest that weighting the loss function helped the models assign greater importance to minority classes, thereby improving their ability to detect severe cases that were underrepresented in the dataset.

However, the persistence of false negatives in severe categories suggests that model performance is still limited by data constraints. Specifically, the absence of high-resolution contextual variables, such as real-time traffic flow, precise lighting intensity, and road geometry, reduces the models’ capacity to capture the situational nuances that often precede severe outcomes.

4.6. Limitations and Data Context

Despite the improvements obtained through resampling strategies and model optimization, the recall for severe accidents (classes 2 and 3) remained below 0.60 across all predictive models. This limitation is primarily associated with two structural characteristics of the dataset:

- (a)

Class imbalance: Severe accidents represent less than 3% of the observed cases, providing limited examples for the models to learn high-severity patterns. This scarcity reduces model sensitivity to rare but critical events.

- (b)

Pandemic-related temporal distortion: Mobility restrictions during the COVID-19 period (2020–2021) altered traffic volume and exposure profiles, resulting in an atypical decrease in accident frequency. Because these years reflect a non-standard operational context, models trained on the full 2019–2023 timeframe may learn temporal patterns that do not generalize to post-pandemic conditions.

Furthermore, an inherent limitation of this study is that crash severity was treated as a nominal multiclass variable, despite its ordinal nature (0 < 1 < 2 < 3). This approach was intentionally chosen to maintain comparability with prior research, as most existing studies on crash severity prediction adopt a nominal classification framework using algorithms such as Random Forest, XGBoost, or Deep Neural Networks (see

Section 2).

An additional limitation concerns the availability of certain explanatory variables at prediction time. The feature Probable Cause, while informative for understanding accident mechanisms, is an ex-post attribute determined by law enforcement during post-accident investigation. In this study, it was included in the training process because the objective was to explore the upper-bound predictive performance obtainable from the full police dataset. This choice aligns with exploratory research practices but means that the resulting models do not yet reflect a fully operational pre-event or real-time prediction setting.

We also Acknowledge that, although the original dataset contained fine-grained timestamps (day, hour, and minute), these variables were intentionally excluded from the modelling stage. Retaining them would have required high-dimensional one-hot encoding, substantially increasing computational demands given the 330,000+ records and already large number of categorical features. To preserve temporal information in a computationally feasible way, only the year and month were retained as temporal predictors. The exclusion of finer temporal granularity is acknowledged as a limitation of the present work, and future research with greater computational resources should incorporate cyclic encodings of hour-of-day and day-of-week to better capture periodic crash patterns.

An additional limitation concerns the geographic coverage of the dataset. The current dataset primarily represents mainland rural areas, with limited or no data from major urban centers, as well as the autonomous regions of Madeira and Açores. Since traffic patterns, exposure levels, and accident dynamics differ in large cities and islands, the models’ generalizability to these contexts is limited. Including these regions in future studies would improve the spatial representativeness and robustness of predictive models.

To move toward deployable systems, future work should also explicitly evaluate model performance under operationally realistic feature constraints, excluding ex-post attributes such as Probable Cause and retaining only information available at or before emergency dispatch. In parallel, research should explore ordinal-aware learning approaches (e.g., ordinal regression, cost-sensitive models, or focal loss) that reflect the progressive nature of crash severity. Such advances would complement the improved feature design and ultimately produce models that are both methodologically robust and practically applicable for real-world road safety decision-making.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the potential of classical Machine Learning and Deep Learning techniques to predict the severity of road traffic accidents using operational data provided by the GNR. The comparative analysis across models—Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), and Deep Neural Network (DNN), showed that performance strongly depends on the approach used to address class imbalance, a recurring challenge in accident datasets where severe events are rare.

Among the tested configurations, the DNN weighted provided the strongest ability to detect severe and fatal crashes, achieving the highest recall for minority classes while maintaining robust performance on majority categories. This conclusion is supported by the class-wise metrics reported in

Table 4, which reveal that neural network models benefited substantially from loss reweighting, unlike tree-based models whose improvements were more limited. While aggregated metrics such as macro recall and G-Mean offer a global perspective, the per-class analysis confirms that the proposed weighting strategy produced the most operationally meaningful gains for classes 2 and 3, which are of greatest importance for road safety management.

The feature analysis also highlighted the relevance of contextual factors, which showed meaningful associations with severity levels. Although correlation does not establish causation, the observed relationships align with established road safety evidence and can support targeted interventions such as improving street lighting, reinforcing visibility conditions in rural areas, and prioritizing patrol presence during low-light periods.

Model performance was nonetheless constrained by the dataset’s imbalance, limited feature diversity, and atypical mobility patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic.

These factors reduced the availability of representative examples of severe crashes and likely hindered generalisation. The results therefore reinforce that predictive systems should complement, rather than replace, expert operational judgment and must be interpreted as probabilistic decision-support tools.

From a sustainability perspective, this work contributes by demonstrating how data-driven risk estimation can support safer mobility systems, reduce human and economic losses, promote more efficient deployment of public resources, and assist in designing targeted preventive actions aligned with sustainable development goals. Improved prediction of severe accidents directly supports long-term road safety strategies, ultimately fostering more resilient and sustainable transport infrastructures.

Future research should explore richer spatiotemporal representations, cyclic encodings of time variables, operationally realistic feature constraints, and advanced imbalance-aware methods such as ordinal regression or focal loss. Additionally, exploring out-of-time and spatially grouped validation, when computationally feasible, would improve the assessment of model robustness. Integrating these models into operational platforms could enable real-time severity risk estimates, supporting proactive patrol allocation, more efficient emergency response, and evidence-based infrastructure planning.