Abstract

This study addresses the challenge of electric vehicle power battery recycling by proposing a dynamic deposit-refund system (DRS) under the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) framework, as an alternative to the conventional static DRS. An evolutionary game model is developed to capture the strategic interactions between local governments and responsible enterprises, incorporating a feedback mechanism where the deposit level is dynamically adjusted based on corporate EPR fulfillment rates. Using system dynamics simulation, the evolutionary paths under both static and dynamic DRS regimes are compared. The results demonstrate that the dynamic DRS effectively eliminates persistent oscillations and guides the system toward a stable equilibrium. Furthermore, by defining an ideal scenario, key factors are identified and prioritized to assist the government in steering the system toward this desired state. These findings offer actionable insights for designing adaptive regulatory mechanisms and fostering a self-sustaining battery recycling ecosystem.

1. Introduction

Given their status as a fundamental component of the new energy sector, electric vehicles (EVs) have become key contributors to international initiatives aimed at mitigating environmental degradation and bolstering energy security [1,2,3]. The industry’s significance in advancing the circular economy is underscored by projections that global EV production and sales will approach 25 million units within the next five years [4,5]. As part of its commitment to a green development strategy, China has risen to become a leading player in this sector. By 2018, the country accounted for nearly half of the world’s EV output, marking a significant stride in its industrial transformation [6,7]. Concurrently, the installed capacity of power batteries—core EV component—has experienced a remarkable surge [8,9,10] and is projected to peak at 4 Terawatt-hour(TWh) by 2040 [11]. Illustrating this growth, China’s installed power battery capacity soared from over 140 GWh in 2018 [12] to 548.4 Gigawatt-hour (GWh) by the end of 2024 [13], representing an increase of approximately 3.91-fold.

A typical EV battery pack has a service life of 4–6 years [14], after which its capacity degrades to 70–80%, rendering it unsuitable for vehicular use due to safety and performance concerns [15]. Given the widespread promotion of EVs in China since 2009, a large number of EVs have now reached their end-of-life, leading to an impending wave of retirements [16,17,18,19]. The recycling and reuse of used batteries, as a crucial part of supply chain management, poses numerous risks if not handled properly, including safety accidents, environmental pollution, and the loss of critical metal resources [20,21,22].

By emphasizing the management of waste products across the entire supply chain, EPR has become a fundamental policy mechanism for power battery recycling worldwide [23,24]. Conceptualized by Swedish economist Thomas Lindhqvist in 1990 [25], the EPR framework mandates that producers assume comprehensive responsibility for their products’ entire lifecycle, thereby formalizing their role in post-consumer recycling. This philosophy represents a paradigm shift from traditional “end-of-pipe treatment” toward “source prevention” via comprehensive lifecycle management [26], aiming to achieve resource circulation and minimize environmental pollution [27]. This approach has proven effective in clarifying responsibilities for managing retired EV batteries [28,29].

China attaches great importance to the closed-loop supply chain management of power batteries, which led to the official establishment of the EPR recycling system for retired ones in 2018 [30]. Subsequent regulatory updates, including the 2023 “Management Measures for the Comprehensive Utilization of Power Batteries for New Energy Vehicles (Draft for Comments),” have further specified the recycling obligations of various stakeholders [31]. Despite these policy efforts, compliance among responsible enterprises remains inadequate. The formal recycling rate stagnated at a low level, and in 2023, the formal recycling rate of electric vehicles in China was still below 25% [32]. This compliance gap necessitates that local government develop and implement targeted measures tailored to regional contexts to effectively incentivize EPR adoption.

Chinese local government has explored various policies within the framework of product waste recycling (EPR) to promote the management of battery recycling in a closed-loop supply chain. Examples include Shanghai’s flat subsidy of Renminbi (RMB) 1000 per unit and Hefei’s capacity-based subsidy, which was raised from RMB 10/kWh to RMB 20/kWh. While such subsidies can stimulate recycling, they concurrently impose sustained financial burdens on local government [33,34]. As a market-oriented alternative, the DRS aligns with EPR principles by imposing a processing fee at the point of battery sale, which is refunded upon the return of the retired battery, thereby incentivizing recycling outcomes [35]. This mechanism engages battery manufacturers, EV sellers, or consumers directly, promoting environmentally responsible behavior while reducing the fiscal pressure on local government. International implementations vary, with the U.S. focusing on consumers and Japan targeting manufacturers. In China, Shenzhen’s pilot DRS from 2018 to 2020, which mandated EV retailers to collect recycling fees, serves as a critical case study. Nevertheless, in the closed-loop supply chain management of battery power, a significant knowledge gap remains regarding the long-term efficacy of DRS in shaping the strategic decision-making and EPR compliance of responsible enterprises.

Consequently, this research seeks to answer the following three questions:

(1) How do local government and responsible enterprises co-evolve their strategies under the prevailing static DRS, and does a stable evolutionary strategy exist?

(2) Is adjusting the deposit-refund amount necessary for system stability and achieving an ideal scenario satisfying both parties?

(3) What key factors should local government prioritize to facilitate system convergence toward stability and the ideal scenario?

To promote the construction of a closed-loop supply chain system for battery power, this research explores the strategic dynamics between local government and responsible enterprises by applying evolutionary game theory to a conventional, static DRS framework. Subsequently, we propose a novel dynamic DRS framework where the deposit level is contingent upon the corporate EPR fulfillment rate. We analyze the evolutionary properties of this dynamic system and define an ideal scenario that aligns the interests of both stakeholders. By utilizing the relevant research data of scholars and conducting system dynamics simulations, we conducted numerical simulation comparisons of the evolution trajectories and performance results under the static and dynamic DRS systems. Finally, by identifying and analyzing the factors that critically influence the realization of the ideal scenario, we delineate prioritized areas for policy intervention.

The paper is organized as follows. Following this introduction, Section 2 first surveys the existing literature. Section 3 then proceeds to introduce the problem description, model assumptions, and the constructed model. We analyze and compare the evolutionary characteristics of local government, responsible enterprises and hybrid systems under a static deposit-refund system in Section 4. Meanwhile, we propose and establishes a dynamic deposit-refund system, define and analyzes an ideal scenario, and utilizes a system dynamics model to visually compare the evolutionary paths of static and dynamic systems (Section 5). Section 6 analyzes the sensitivity of the parameters and proposes a ranking of factors that the local government should focus on to promote the probability of the ideal scenario. Section 7 summarizes the entire study and proposes the research significance of this paper from a management perspective.

2. Literature Review

2.1. EPR for the Recycling of Power Batteries

Scholars have identified the EPR system as a viable mechanism for enhancing recycling efficiency by clarifying responsibility allocation in the closed-loop supply chain management [36,37]. For instance, Zeng et al. contended that EPR could effectively address pervasive issues within China’s battery recycling sector, including systemic fragmentation, ambiguous legal measures, and low recycling rates [38]. From the perspectives of resource recycling and environmental externalities, Compagnoni et al. demonstrated that EPR management could facilitate the export of waste power batteries by enhancing environmental recycling capabilities, especially in countries deficient in rare metals [39]. Parallelly, Yang et al. highlighted the relevance of the EU’s battery recycling experience for China, underscoring the need to refine financial responsibility and incentive structures [40]. Through a systematic comparative analysis of EPR policies in the EU, U.S., and Canada, Turner and Nugent centered their investigation on the tension between environmental objectives and cost considerations across the product lifecycle [28]. Meanwhile, Chaudhary and Jain evaluated India’s EPR implementation for power battery recycling and derived pertinent policy recommendations [41]. Quantitative research on EPR in battery recycling has yielded further insights. He and Lin identified dynamic incentives and penalties as key drivers of recycling enthusiasm among EV manufacturers, whereas high recycling costs were pinpointed as a primary barrier for unregulated enterprises [42]. Yan et al. demonstrated that the success of EPR implementation is context-specific, as supply chain member profits vary significantly with different recycling rates [43]. Xu and Tang assessed how subsidies, rewards, and penalties influence recycling decisions across different responsibility-bearing entities [44]. Furthermore, Qi et al. highlighted the critical roles of recycling technology efficacy and brand differentiation in guiding technical investment decisions for battery recycling [45]. Insights from recent EPR studies on e-waste and packaging materials also provide valuable parallels [46,47,48,49,50].

While the extant literature substantiates the role of EPR in facilitating effective battery recycling, a significant gap remains in understanding the dynamic behavioral characteristics and evolution of responsible parties’ willingness to comply.

2.2. The DRS

The DRS operates as a market-based instrument that integrates principles of taxation and subsidies, involving an upfront environmental fee levied on new products which is subsequently refunded upon their return for recycling [51]. This mechanism has seen extensive application across various waste streams, including photovoltaic modules [52], e-waste [53], beverage containers [54], and express packaging [55]. The application of DRS to retired power batteries has attracted considerable academic interest. Li et al. confirmed that DRS significantly boosts recycling rates, they also noted potential profit losses for participants [56]. Wang et al. suggested that the effectiveness of DRS is contingent on the broader energy structure [57], and Li et al. highlighted initial processing costs as a pivotal factor for system optimization [58]. Liu and Zhu, analyzing the strategic interaction between manufacturers and recyclers, proposed DRS for high raw-material-price environments and revenue-sharing contracts as an alternative [59]. Cui and Wang concluded that government-led DRS enhances sustainability goals, though its reliance on consumer incentives may be inadequate in rapidly evolving markets [60]. Wu et al. provided a nuanced analysis of decision-making under different recycling modes and fee-collection entities, elucidating DRS’s influence on supply chain performance and recycling rates [61,62]. Comparative analyses have also been conducted, pitting DRS against alternative instruments like subsidies and reward-punishment mechanisms [63,64,65,66,67]. The theoretical appeal and practical recognition of DRS largely stem from its dual capacity to alleviate government fiscal pressure while embedding punitive measures akin to taxation [62].

However, the behavioral heterogeneity of responsible parties and the adaptability of a static deposit-refund amount to these evolving behaviors remain critically underexplored.

2.3. Evolutionary Game-Theoretic Method

In contrast to traditional game theory, evolutionary game theory differs significantly in research perspective, assumptions of rationality, and analytical framework [68,69]. Traditional game theory, built on the assumption of “perfect rationality,” primarily analyzes the optimal strategies of individuals and their equilibrium states in static scenarios. Evolutionary game theory, grounded in the premise of “bounded rationality,” focuses on how populations gradually adopt and eventually stabilize around relatively successful strategies through imitation, learning, and adaptation in dynamic processes. Within this framework, collective economic behaviors are not the result of one-shot optimization but gradually converge toward an Evolutionarily Stable Strategy (ESS) through repeated interactions [69]. The ESS refers to a strategy profile that can resist invasion by any minor mutant strategies during the evolutionary process, thereby maintaining the stability of the population state, and mathematically corresponds to a stable equilibrium point in evolutionary dynamics. The application of evolutionary game theory has extended to various environmental and resource management domains, including EV promotion incentives [70], retired power batteries [60,71], and shared bicycle recycling [72]. Within the specific context of battery recycling systems, a substantial body of work employs this methodology. For example, Gao et al. modeled the transition from informal to formal recycling, advocating for dynamic penalties against informal operators [73]. Lyu et al. and Yu et al. investigated pathways to effective cooperation, recommending phased supervision or a hybrid of supervision and subsidies [74]. Zhang et al. analyzed the three-party equilibrium among the government, manufacturers, and consumers, and proposed a phased withdrawal of subsidies [75]. Yang et al. analyzed the mechanisms through which policy shapes the co-evolution of behaviors in a system involving consumers, formal, and informal recyclers [76]. The work of Du et al. centered on the evolutionary game dynamics between government entities and diverse collection points, underscoring the critical role of incentive-based regulation [77]. The necessity of governmental leadership complemented by market coordination in the early stages of battery recycling was stressed by Wang et al. [78]. Li et al. found consumer-oriented subsidies to be effective and attributed improvements in formal recycling efficiency primarily to DRS [64]. Cui and Wang demonstrated the superiority of government-participated DRS over purely market-driven systems, which often lack sufficient consumer constraints [60].

This study is grounded in the well-established theoretical framework of evolutionary game theory. Although the work of Ji et al. [70] is particularly instructive, our research distinguishes itself through its distinct focus and the specific local government incentive mechanism under investigation.

2.4. Research Gap

The current research status provides excellent references and inspirations for this study, especially in the literature [52,56,62,70]. However, our research differs to some extent from the aforementioned literature. For instance, Miao et al. [52] focused on the promoting effect of the deposit on the recycling of Photovoltaic (PV) modules, while our attention is on electric vehicle batteries. Although Li et al. [56] and Ji et al. [70] studied the impact of deposit-refund system on the recycling of electric vehicle batteries, the former focused on the cooperative behavior of recycling while the latter focused on the recycling channels, what distinguishes us from them is that we consider the behaviors between the regulatory entity and the executive entity. Ji et al. [62] provided us with valuable insights, but their research focused on how to optimize the subsidy policies for promoting the production of new energy vehicles.

EPR as imperative for managing power battery recycling, yet consistent compliance often requires supplementary local government intervention. The DRS, which simultaneously alleviates fiscal pressure on local government and penalizes non-compliance, presents a promising tool; however, its specific impact on the dynamic behavioral evolution of enterprises regarding EPR fulfillment demands deeper investigation. This paper utilizes the “bounded rationality” and dynamic strategy adjustment framework of evolutionary game theory to analyze how the strategies of both parties (whether the local government implements the DRS and whether enterprises fulfill EPR) evolve over time through learning and imitation under both static and dynamic DRS rules. Specifically, it designs a feedback mechanism where the deposit level is dynamically adjusted based on the corporate EPR fulfillment rate.

This study makes several distinct contributions as Table 1:

Table 1.

Comparison between our study and related literature.

(1) Based on the pilot operation mechanism of battery recycling in Shenzhen, our research analyzes how a local government-led DRS affects the strategic behavior of enterprises toward EPR compliance.

(2) It introduces a novel dynamic DRS framework, where the deposit is contingent upon the enterprise EPR fulfillment rate, and contrasts its evolutionary outcomes with that of a static DRS.

(3) It conceptualizes an ideal scenario that aligns the interests of both local government and responsible enterprises, and subsequently identifies a prioritized set of factors for local government to target in promoting this scenario.

3. Model Preliminaries

This section delineates the foundational elements of our study, encompassing the problem description, underlying assumptions, and model construction.

3.1. Problem Description

The effective recycling of EV power batteries necessitates the coordination of multiple stakeholders. This study narrows its focus to two key actors: local government (Based on the current situation of battery recycling in China, local government referred to in this article can represent a city, such as Shenzhen and Hefei, or a province, such as Shanghai.) and the entities bearing recycling responsibility, namely power battery manufacturers and electric vehicle sellers. The fulfillment of recycling responsibilities by battery manufacturers and electric vehicle dealers is a crucial step in achieving a closed-loop supply chain management for batteries. As mandated by China’s late-2023 “Management Measures for the Comprehensive Utilization of Power Batteries of New Energy Vehicles (Draft for Comment)”, these responsible enterprises are obliged to manage the recycling process from the point of battery installation through the consumer use phase. A critical requirement is the transfer of collected retired batteries to officially whitelisted processors, a measure designed to prevent diversion into non-compliant recycling channels.

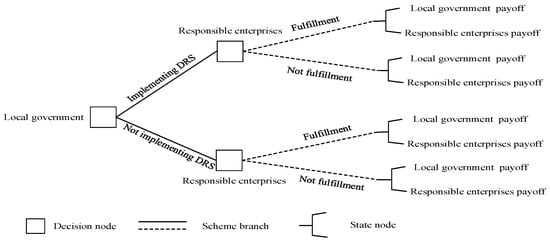

To visually illustrate the strategic interactions between local governments and responsible enterprises, this paper constructs a decision tree model as shown in Figure 1. The model clearly depicts the sequential decision-making process: first, the local government decides whether to implement the Deposit-Refund System (DRS); then, responsible enterprises choose whether to fulfill their Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) obligations based on the government’s policy. The payoffs under each strategy combination correspond to the parameter settings defined in Section 3.2 (see Table 2 for details) and are ultimately reflected in the game payoff matrix (Table 3). In the figure, solid arrows represent the local government’s decision branches, while dashed arrows represent the enterprises’ decision branches. The payoff pairs at the terminal nodes correspond to the respective gains or losses for the enterprises and the local government. Notably, when the government chooses “Not Implement DRS,” the system reverts to the traditional EPR regulatory scenario, where enterprises still face the decision of whether to comply and bear corresponding recycling costs or informal channel revenues, while the local government continues to bear environmental governance costs or gain social reputation benefits. This decision tree provides a clear strategic structure and payoff mapping for the subsequent evolutionary game analysis.

Figure 1.

Decision tree of payoffs for local government and responsible enterprises.

Table 2.

Main parameters and definitions.

Table 3.

Payoff matrix between local government and responsible enterprises.

3.2. Model Assumptions

Our model explicitly treats the EPR-based power battery recycling system as a dynamic system characterized by continuous evolution. The participating actors-local government and responsible enterprises-are assumed to be boundedly rational, continuously adapting their strategies through a process of learning and imitation to maximize their respective benefits. The formal assumptions of the model are as follows:

Assumption 1 (Strategic Spaces): In this game, the strategies available to both parties are defined as follows:

Responsible Enterprises: Fulfill EPR (probability ) or Not Fulfill (probability ).

Local Government: DRS implemented (probability ) or DRS not implemented (probability ()).

Assumption 2 (Deposit Nature): The recycling deposit is levied per unit of power battery capacity. It is assumed that this deposit does not influence decision-making during the EV sales cycle.

Assumption 3 (Enterprise Payoffs):

- (1)

- If enterprises Fulfill EPR, they incur a unit recovery cost (covering network construction, storage, transportation, etc.) and gain formal revenue (from cascade utilization or dismantling), an environmental preference benefit , and a reputational benefit . They also receive a refund of ().

- (2)

- If enterprises Do Not Fulfill EPR, they may gain revenue by outsourcing to informal recyclers but forfeit the deposit . This action imposes an environmental governance cost on the local government.

Assumption 4 (Local government Payoffs):

- (1)

- If local government Implement DRS, they incur human resource costs (for verification/admin) and a time cost (reflecting opportunity costs). They gain a social reputation benefit if enterprises fulfill EPR.

- (2)

- If enterprises Do Not Fulfill EPR and local government Has Not Implemented DRS, local government bears the environmental cost .

Definitions of the key parameters are provided in Table 2.

The payoff matrix for the strategic interactions, following from the preceding assumptions, is constructed in Table 3.

3.3. Model Construction

We apply replication dynamics to model the players’ strategic evolution. This method describes the evolution of strategy adoption rates over time, determined by the relative payoff of each strategy. Thus, the construction of these equations allows for the analysis of the evolutionary trajectory governing the strategic interactions between local government and responsible enterprises.

- (1)

- Replicator dynamics for responsible enterprises

The expected payoff for a responsible enterprise that chooses to Fulfill EPR is denoted as and given by:

The expected payoff for Not Fulfilling EPR is as follows:

The average expected payoff for responsible enterprises is therefore:

The replicator dynamic equation for the evolution of is thus:

- (2)

- Replicator dynamics for local government

The expected payoff for a local government that chooses to Implement DRS is :

The expected payoff for Not Implementing DRS is :

The average expected payoff for local government is as follows:

The replicator dynamic equation for the evolution of is thus:

- (3)

- The replicator dynamic system

Therefore, according to Equations (4) and (8), the two-dimensional dynamical system (I) governing the strategic evolution of both parties is given by:

4. Model Solution and Analysis

The long-term outcome of the strategic interactions is captured by the ESS concept, characterized by its robustness to small-scale strategic deviations. Based on the proposed model, this section first examines the ESS for each party individually, then for the coupled system.

4.1. ESS Analysis of Responsible Enterprises

The stability of the strategic outcomes for responsible enterprises is analyzed by examining the first-order derivative of the replicator dynamic equation (Equation (4)) with respect to is as follows:

An ESS must satisfy the equilibrium condition and the local stability condition . Setting yields three potential equilibrium points: or or . When , implying all states are neutrally stable, and the strategy choice of the enterprises does not evolve. When , the stability of the pure strategies ( or ) must be analyzed, leading to the following scenarios.

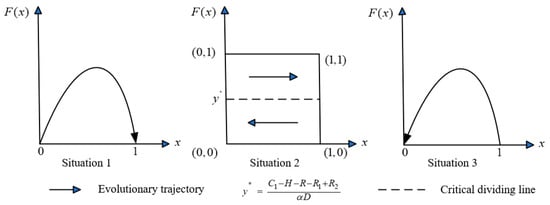

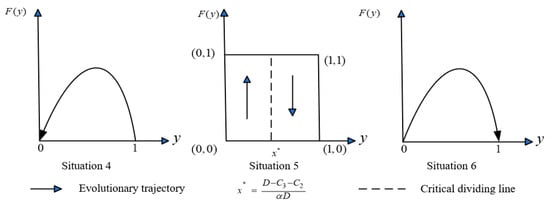

Situation 1. If Here, always holds. The derivative satisfies and , indicating that is the only ESS.

Managerial Insight: Fulfilling EPR is the dominant strategy for enterprises when the net benefit (encompassing reputational, revenue, and environmental benefits) of formal recycling outweighs the net benefit of informal recycling, irrespective of local government’s action.

Situation 2. If Local government’s strategy becomes pivotal.

- ①

- if , , , making the ESS.

- ②

- if , , , making the ESS.

Managerial Insight: A sufficiently high probability of local government implementing DRS () can steer enterprises towards EPR compliance. This represents a scenario where policy intervention is effective.

Situation 3. If Here, always holds. The derivative satisfies , , indicating that is the only ESS.

Managerial Insight: Non-compliance becomes the dominant strategy if the cost of formal recycling and the revenue from informal channels are prohibitively high, rendering the current level of DRS intervention ineffective.

According to scenarios 1, 2 and 3, the phase diagram of the evolution path and stability of responsible enterprises’ strategic choices is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Phase diagram of the evolutionary path and stability for responsible enterprises’ strategic choices.

4.2. ESS Analysis of Local Government

We now turn to the stability analysis for local government, which is conducted analogously. Differentiating Equation (8) with respect to yields:

The equilibrium points are or or . When , and all states are neutrally stable. When , the stability is analyzed based on the value of

Situation 4. If . Here, , always holds. We find , making the ESS.

Managerial Insight: Local government will not implement the DRS if the operational and time costs exceed the deposit income.

Situation 5. If , the enterprise’s strategy influences local government’s decision.

- ①

- if , and , making the ESS.

- ②

- if , , making the ESS.

Managerial Insight: A low probability of enterprise compliance makes DRS cost-ineffective, leading local government to withdraw it.

Situation 6. If , here always holds. We find, and , making the ESS.

Managerial Insight: If the operational and time costs of the DRS do not exceed the deposit income, local government will implement it.

According to scenarios 4, 5 and 6, the phase diagram of the evolution path and stability of local government’s strategic choices is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The phase diagram of the evolution path and stability of local government’s strategic choices.

4.3. ESS Analysis Between Responsible Enterprises and Local Government

We now analyze the stability of the coupled system. Given that Situations 2 and 5 most accurately reflect the realities of China’s power battery recycling market, the subsequent system-level analysis is conducted under these constraints. According to the dynamic system replication Equation (9) that describes the evolution of the strategic system of local government and responsible enterprises, we can know that when and are satisfied, the evolution system of the interactive game between the two sides contains five equilibrium points: , , , and , where and .

We employ the Jacobian matrix method (Friedman [69]) to assess local stability. Based on Equation (9), the Jacobian matrix for our evolutionary system, the and the can be obtained (The proof can be found in Appendix A).

The asymptotic stability of an equilibrium point requires that both By evaluating these conditions at each equilibrium point, we obtain the stability results summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Local stability of the equilibrium points.

The stability analysis in Table 4 yields a key conclusion: asymptotic stability is unattainable at any of the five equilibria. The pure-strategy equilibria , , and are saddle points or unstable, while the mixed-strategy equilibrium is a center. This indicates that the system under a static DRS lacks an Evolutionarily Stable State. The strategies of both players will oscillate perpetually around the center point , forming closed-loop trajectories. This implies a lack of a convergent, stable outcome in the power battery recycling game, leading to continuous strategic adjustments without a mutually satisfactory, long-term equilibrium.

5. Evolutionary Game Analysis Under Dynamic DRS

5.1. ESS Analysis Under Dynamic DRS

The analysis in Section 4.3 demonstrates that a static DRS is inherently unstable, resulting in persistent strategy oscillations. To remedy this, we introduce a dynamic DRS, wherein the deposit amount is contingent upon the EPR compliance level of responsible enterprises. This design creates a feedback mechanism to better align incentives and steer the system towards a stable equilibrium. Formally, the dynamic deposit is defined as , where is the base deposit value. This functional form embodies a core policy principle: the deposit decreases as the compliance rate rises, thereby lowering the industry’s financial burden during periods of high compliance, and conversely increasing the economic incentive for compliance when it is low.

Substituting into Equation (9) yields the corresponding system for the dynamic DRS as Equation (12):

The equilibrium conditions of the replication under dynamic DRS should be and . We can easily obtain the equilibrium points: , , , and , where and .

Corollary 1.

According to Equation (12), we can obtain the following result: there are three saddle points, one instability point and one asymptotically stable point of the five equilibrium points, where the saddle points are , , and , the instability point is and the asymptotically stable point is . The proofs of Corollary 1. is presented in Appendix B.

For the evolving system under the dynamic DRS, the Jacobian matrix yields a pair of complex conjugate eigenvalues, and the negativity of their real parts indicates local stability. We conclude that the point is a globally stable equilibrium for the evolutionary game under the dynamic DRS, with all evolutionary paths characterized by a spiral convergence to this point.

5.2. Determinants of the Equilibrium Probability of an Ideal Scenario

The ultimate policy objective is to cultivate a self-sustaining recycling market with EPR principles so deeply embedded that compliance continues independent of direct local government intervention.

Definition 1.

We define an ideal scenario

as a state where responsible enterprises achieve perfect EPR compliance without local government intervention through the DRS.

Consequently, the probability of the ideal scenario materializing in the interactive game is defined as:

By substituting the asymptotically stable point of the dynamic system into (13), we obtain the equilibrium probability of the ideal scenario:

Corollary 2.

The equilibrium probability of the ideal scenario

is negatively correlated with the unit recovery cost and the informal revenue , but positively correlated with the reputational benefit , the formal recycling revenue and the environmental preference benefit . The proofs of Corollary 1. is presented in Appendix C.

Corollary 2 shows that when conditions and are met, the higher the per unit capacity recycling cost of electric vehicle power batteries, the more responsible enterprises tend to entrust informal enterprises to complete power battery recycling tasks to obtain higher profits. Faced with this, a rational local government responds by strengthening deposit system enforcement, which consequently diminishes the likelihood of ideal scenario from being realized. On the other hand, when the environmental preference benefits of responsible enterprises fulfilling the EPR system is high, and they can also obtain more recycling benefits and more potential social reputation benefits, there is no doubt that more responsible enterprises will be willing to fulfill the EPR system. Therefore, a higher corporate EPR compliance rate leads to a lower probability of DRS implementation by local government, thereby increasing the likelihood of the ideal scenario.

5.3. System Dynamics (SD) Simulation

We formalized the evolutionary game using a System Dynamics (SD) model, leveraging replicator dynamics to enable virtual experiments and a sensitivity analysis of key parameters [42]. Our model is engineered to capture the dynamic trajectories of strategy adoption across a range of scenarios. Parameter values are based on existing literature and some data from the Chinese battery recycling industry and rigorously defined to comply with all model requirements.

5.3.1. Data Source

Parameterized for China’s power battery recycling landscape, our study acknowledges the formal EPR framework, including the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology’s (MIIT’s) “white list” and relevant “Interim Measures.” Yet, a significant implementation gap remains. The absence of a robust responsibility identification and punishment mechanism has resulted in a formal recycling rate below 25% [32]. Aligning with the methodology of [64], the initial strategy probabilities are set to for enterprise EPR fulfillment and for local government DRS implementation.

Parameter values are drawn from policy documents and prior scholarly work. The base deposit is set at 20 yuan/Kilowatt-hour (kWh), based on the 2018 Shenzhen New Energy Vehicle Promotion and Application Funding Support Policy. Following [52], local government’s human resource cost for DRS administration is 0.7125 yuan/kWh. Local government’s time cost , reflecting opportunity costs, is set to 15.5625 yuan/kWh, derived from [76] and adjusted for model consistency. For responsible enterprises, the unit recovery cost 1 yuan/kWh [79]. Fulfilling EPR yields a formal recycling revenue 243 yuan/kWh, an environmental preference benefit 31.495 yuan/kWh, and a reputational benefit 137 yuan/kWh [52,64,75]. Alternatively, outsourcing to informal recyclers provides a revenue [64]. The environmental pollution control cost borne by local government [76].

To ensure dimensional consistency across parameters, we adopt the power battery capacity density calculation from [64]. Using the BYD Qin PLUS EV—a leading model in China’s A-class sedan market—as a benchmark, we derive the energy density. Given a battery capacity of 71.7 kWh and a pack weight of 512 kg, the resulting energy density is approximately 140 kWh per ton. This value facilitates the unification of data sourced from different references.

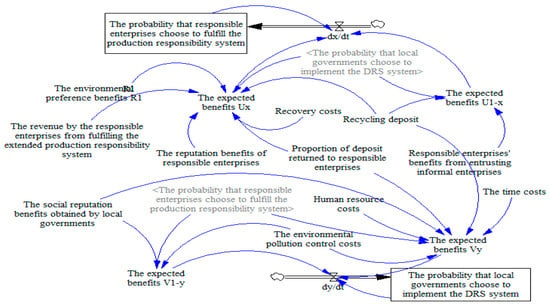

5.3.2. Simulation Analysis

The System Dynamics (SD) model, implemented in Vensim software and based on the replicator dynamic system (Equation (9)), was developed to simulate the strategic interaction (Figure 4). The model structure comprises two stock (level) variables-the strategy probabilities and - and their corresponding flow (rate) variables and , which represent their rates of change. Eleven external parameters, detailed in Table 2, influence the model, with the causal relationships rigorously defined by the payoff matrix and the replicator dynamics. The simulation was set with a time horizon of 12 months, a time unit of one month, and an integration step size of 0.001 to ensure numerical stability and accuracy. This setup enables the robust simulation of the dynamic evolutionary process governing the strategic behaviors of both parties.

Figure 4.

The SD flowchart model of the evolutionary game.

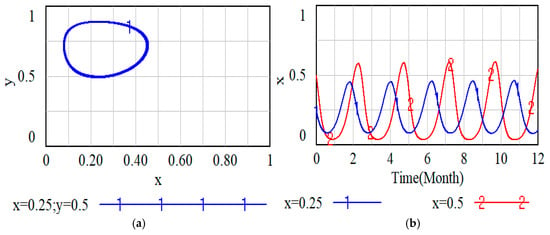

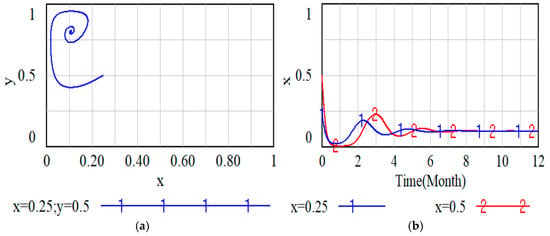

This section mainly discusses the evolution of the mixed strategies of both parties and the probability that responsible enterprises choose to fulfill the EPR system under different DRS and initial values. Figure 5 and Figure 6 present the simulation results.

Figure 5.

Replicator dynamics under static DRS. (a) Simplex for the evolutionary game under static DRS. (b) The evolving behavior of responsible enterprises under static DRS.

Figure 6.

Replicator dynamics under dynamic DRS. (a) Simplex for the evolutionary game under dynamic DRS. (b) The evolving behavior of responsible enterprises under dynamic DRS.

Figure 5a reveals that under a static DRS, the system’s evolutionary path forms a persistent closed-loop orbit around the initial point ( and ), confirming the theoretical prediction from Section 4.3 of a system incapable of reaching a stable equilibrium. Figure 5b demonstrates that for a static local government strategy , the enterprise strategy exhibits sustained periodic oscillations. The amplitude of these oscillations is sensitive to the initial value of ; a higher initial value (e.g., ) results in a wider fluctuation range compared to a lower one (e.g., ). Furthermore, the fluctuation amplitude exhibits a gradual increase over time.

In stark contrast, the dynamic DRS induces a profoundly different system behavior. Figure 6a displays a spiral trajectory that converges over time to a stable equilibrium point, confirming the asymptotic stability proven in Section 5.1. Figure 6b reinforces this finding, showing that despite different initial strategy probabilities, the enterprises’ EPR fulfillment rate consistently converges to the same stable value. While the dynamic DRS successfully ensures system stability, a key insight from the simulation is that, for the given parameter set, the effective deposit level provides insufficient incentive. This results in a stable equilibrium characterized by a relatively high local government supervision level and a sub-optimally low enterprise compliance rate .

6. Sensitivity Analysis and Discussion

This section conducts a sensitivity analysis on the key parameters influencing the evolutionary game. The objective is to identify the most critical levers for policymakers and to determine the direction for optimizing system parameters to maximize the probability of the ideal scenario. The benchmark simulation data from Section 5.3.1 is used, and when analyzing a specific parameter, all other parameters remain unchanged.

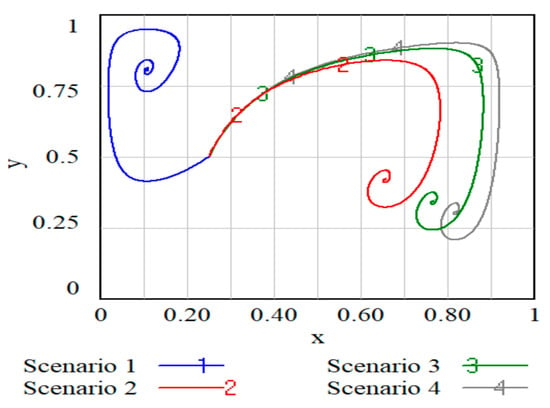

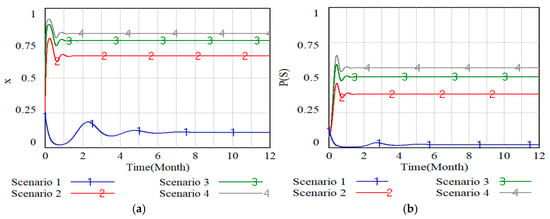

6.1. The Impact of

The base deposit is varied over the interval in increments of 80 to observe its impact, where Scenario 1 to Scenario 4 respectively represent when and Figure 7 shows the players’ evolutionary trajectories, while Figure 8 details the impact on enterprise behavior and the ideal scenario. Figure 7 and Figure 8 respectively illustrate how parameter shapes the players’ strategic evolution and their subsequent compliance behavior.

Figure 7.

Players’ evolutionary game behaviors with different .

Figure 8.

Fulfillment evolutionary dynamics under different . (a) Evolution of responsible enterprises’ behaviors under different . (b) Probability of under different .

As shown in Figure 7, when is relatively small, although local government implement the deposit-refund, responsible enterprises are not very motivated. The reason may be that the current deposit amount is low and the constraints on the responsible enterprises are insufficient. A higher value of renders the fulfillment of EPR obligations predominantly determined by the financial leverage of the recycling deposit. Combined with Figure 8a, it can be seen that when is 20 and 100 respectively, the latter evolves faster, while when is 180 and 260 respectively, the difference in evolution speed between the two is small. This also implies that a well-calibrated deposit is essential to maintain a strong incentive for enterprises, thereby preventing the diminishing marginal utility of the policy and ensuring its long-term efficacy. Figure 8 indicates that the relationship between the probability of responsible enterprises fulfilling their duties as producers and the occurrence of ideal scenarios is positively correlated with , and as increases, the system converges to an equilibrium more rapidly, resulting in a higher equilibrium value for .

Observation. The recycling deposit should satisfy the higher value and the condition of , the speed of system evolution determines the magnitude of the occurrence probability of . Therefore, the setting of the power battery recycling deposit standard should be where .

Figure 7 and Figure 8 reveal that the deposit level acts as a crucial regulatory lever, governing the speed of the evolutionary process and the strategic decisions made by local government and enterprises. The power battery recycling deposit functions as a central mechanism that governs the dynamics of the entire system, fostering a faster evolutionary process, bolstering enterprise EPR compliance, and enhancing the likelihood of the ideal outcome . However, the deposit policy has a clearly defined minimum effective threshold and policy saturation point. When implementing the deposit policy, factors such as local government’s regulatory capacity, market acceptance, and cross-regional coordination need to be taken into consideration as constraints. In the process of policy formulation and implementation, a phased strategy can be adopted: in the initial stage, set a moderate benchmark (ensuring the crossing of the effective threshold), and combine with high dynamic adjustment sensitivity; in the medium term, explore differentiated deposit rates based on the compliance history of enterprises to enhance policy efficiency and fairness; in the long term, it is necessary to collaborate in combating illegal recycling and cultivating a formal market, ultimately leading to an ideal scenario where local government can orderly withdraw its supervision.

6.2. The Impact of and

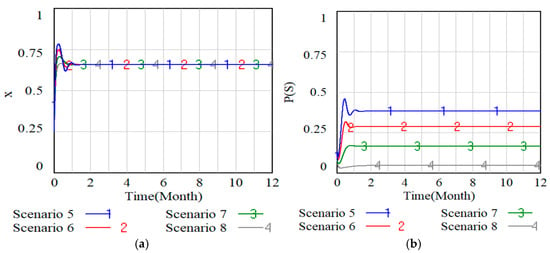

Figure 9 and Figure 10 depict the inverse impacts of and on the evolution of responsible enterprise behavior and the probability, where Scenario 5 to Scenario 8 respectively represent when and and Scenario 9 to Scenario 12 respectively represent when and .

Figure 9.

Fulfillment evolutionary dynamics under different . (a) Evolution of responsible enterprises’ behaviors under different . (b) Probability of under different .

Figure 10.

Fulfillment evolutionary dynamics under different . (a) Evolution of responsible enterprises’ behaviors under different . (b) Probability of under different .

Figure 9 reveals a clear contrast: changes in have minimal impact on the enterprises’ decision to fulfill EPR, but result in a marked, steady decrease in the probability of . Figure 10 indicates that when the added value of is small (), it has little effect on the change in the probability that the responsible enterprises choose to fulfill their responsibility. However, when increases to a certain threshold (), it has an important impact on the probability that responsible enterprises choose to fulfill their responsibility. And is monotonically decreasing with respect to , converging to zero once exceeds a critical threshold. Combining with Figure 9 and Figure 10, we can see that compared with , the decision of responsible enterprises to implement the EPR system is more influenced by the revenue . Although an increase in has little effect on current compliance, local government should view enhanced regulation as a preemptive measure. This is vital to secure the sustainable future of power battery recycling policy from its very inception. In addition, when is large enough (), the probability of responsible enterprises fulfilling their contracts and generating a responsibility system will be greatly reduced, which will inevitably increase the intensity of local government policy implementation, and local government should be more sensitive to this phenomenon (), thereby reducing the time cost in the policy implementation process. In fact, in the process of battery recycling, should be incorporated into the comprehensive engineering of “restructuring the revenue structure”. The effectiveness of the policy depends on whether it can, in a dynamic game, ensure that the overall benefits of the compliant path consistently outperform those of the illegal path. This requires that regulatory measures shift from mere punishment to the cultivation of the compliant market and the systematic squeezing of the illegal profit space.

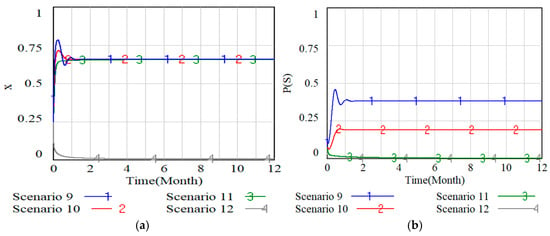

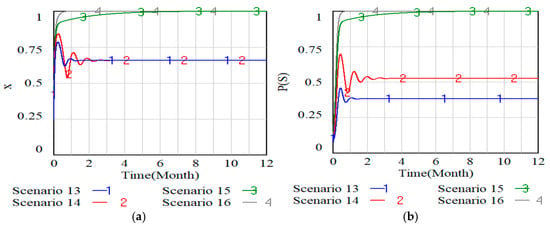

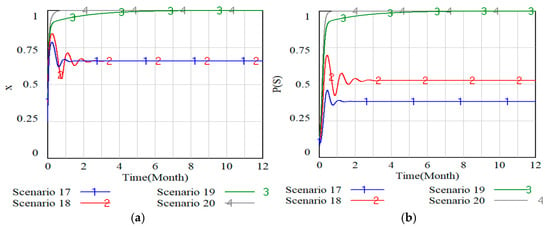

6.3. The Impact of , and

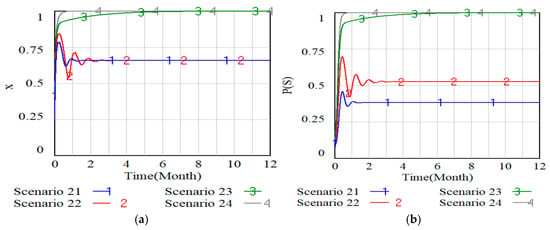

Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13 present simulations of how parameters , and shape the behavioral dynamics of enterprises and the likelihood of the scenario, where Scenario 13 to Scenario 16 respectively represent when and , Scenario 17 to Scenario 20 respectively represent when and and Scenario 21 to Scenario 24 respectively represent when and .

Figure 11.

Fulfillment evolutionary dynamics under different . (a) Evolution of responsible enterprises’ behaviors under different . (b) Probability of under different .

Figure 12.

Fulfillment evolutionary dynamics under different . (a) Evolution of responsible enterprises’ behaviors under different . (b) Probability of under different .

Figure 13.

Fulfillment evolutionary dynamics under different . (a) Evolution of responsible enterprises’ behaviors under different . (b) Probability of under different .

It can be seen from Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13 that when the step increase in the three parameters is equal, the influence of the three parameters on the probability trend of responsible enterprises fulfilling the EPR system and the probability change trend of the ideal scenario is consistent. In particular, when two of the three parameters are static and the other one reaches a certain threshold, the probability that the responsible enterprise fulfills the EPR system and the probability that the ideal scenario occurs are close to 1. In other words, when two of the three parameters are static and the other parameter increases to a certain threshold, the probability that responsible enterprises fulfill their responsibility will increase significantly. Under these conditions, a strategic reduction in direct local government enforcement creates a market environment that incentivizes enterprises to voluntarily adopt ideal practices, ultimately increasing the system’s convergence to the desired state. Our analysis reveals marked variations in how sensitively the three parameters respond to changes in EPR compliance rates and the probability of ideal outcomes. That is, has the greatest impact, is second, and is the smallest. Therefore, should be put first when promoting responsible enterprises to fulfill their responsibility and optimizing key parameters of the probability of ideal scenarios occurring.

7. Conclusions and Management Implications

Effectively managing the looming wave of retired electric vehicle (EV) power batteries hinges on robust EPR compliance. The DRS offers a market-based mechanism that mitigates local government fiscal pressure while penalizing non-compliance. However, existing implementations often assume a static policy framework, failing to account for the dynamic behavioral adaptations of enterprises. By bridging evolutionary game theory with system dynamics simulation, this study introduces a dynamic DRS and provides a rigorous analysis of its efficacy to address this gap. The following draws together the main conclusions of this research and the managerial implications to inform practice.

First, achieving stability in the DRS hinges on its redesign from a static to a dynamic framework. Our analysis establishes that a static DRS inherently precludes a stable equilibrium, as the strategic dynamics between local government and enterprises inevitably generate sustained cyclical fluctuations. This perpetual oscillation indicates a conflicted and inefficient market state. In contrast, when the deposit amount is dynamically linked to the compliance rate of enterprises , the evolutionary path of the system shifts to a spiral convergence, ultimately reaching a stable state. This key finding confirms that implementing a dynamic DRS is a necessary institutional innovation to promote the stable diffusion of EPR-compliant behaviors. Furthermore, during the evolution of the system, the initial probability of responsible enterprises fulfilling their production responsibilities is also a major factor to be considered. Carrying out comprehensive and dynamic credit evaluations for enterprises is of vital importance for the classified supervision of responsible enterprises.

Second, achieving the ideal scenario of a self-sustaining recycling market requires a nuanced understanding of key influencing factors and their prioritized management. The probability of the ideal scenario where enterprises comply without local government supervision is affected by several factors. The unit recovery cost and the revenue from informal recycling are negatively correlated with , while the reputational benefit , formal recycling revenue , and environmental preference benefit are positively correlated. More importantly, these factors exert varying degrees of influence. Therefore, local government should optimize parameters according to a three-tiered priority structure: (1) First Priority: Actively managing the base deposit , suppressing informal revenue , and enhancing formal revenue . (2) Second Priority: Cultivating reputational and environmental benefits through market-driven mechanisms. (3) Third Priority: Supporting technological advancements to reduce the formal recycling cost .

Finally, policymakers must recognize the threshold effects and seek a balance between mandatory intervention and market autonomy. The sensitivity analysis demonstrates that when reputational benefits, formal recycling revenues, and environmental benefits accumulate beyond a certain threshold, enterprises will proactively implement the EPR system. Consequently, a key goal of local government intervention should be to help the market surpass this threshold. Once this is achieved, the focus should shift to monitoring the key factors that could trigger sudden behavioral regressions (e.g., a surge in ) and local government should be prepared to let the market mechanism take over, withdrawing direct supervision at the appropriate time.

This research has certain limitations that concurrently indicate promising directions for future inquiry.

The parameters used in this simulation are mainly derived from the existing literature and some industry data. Future research can conduct empirical simulations based on all the actual operational data of the industry, and combine the specific issues of battery recycling to propose more targeted suggestions, thereby enriching the research of existing theoretical literature.

Secondly, this study focuses on DRS impact, yet subsidies, rewards, and penalties often coexist. Future work should compare multi-policy mixes and expand models to include competitors, informal recyclers, and consumers for broader stakeholder interaction analysis.

Thirdly, while this article proposes that the DRS should be dynamically adjusted based on corporate EPR behavior, it does not specify how to efficiently and accurately obtain this compliance information. To enhance the DRS, future work could leverage digital technologies such as blockchain and Internet of Things (IoT). These tools enable real-time monitoring and data-driven, dynamic fine-tuning of deposit amounts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.C. and H.G.; methodology, H.G., X.H. and L.S.; software, G.C. and X.H.; validation, G.C.; formal analysis, G.C. and L.S.; investigation, G.C. and X.H.; resources, G.C.; data curation, X.H. and L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.G., X.H. and L.S.; writing—review and editing, H.G. and G.C.; visualization, H.G. and G.C.; supervision, G.C.; project administration, G.C.; funding acquisition, H.G. and G.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study is supported by a project funded by Fundamental Funds for Humanities and Social Sciences Program of the Ministry of Education (21YJC630077, 24YJC630048); Henan Provincial Science and Technology Research Project (252102411002); Doctoral Research Fund Project of Henan Finance University (2024BS018); the Scientific Research Team Plan of Zhengzhou University of Aeronautics (23ZHTD01013).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude for the hard work of the reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| EPR | Extended Producer Responsibility |

| DRS | Deposit-Refund System |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| ESS | Evolutionarily Stable Strategy |

| SD | System Dynamics |

| MIIT | Ministry of Industry and Information Technology |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| RMB | Renminbi |

| GWh | Gigawatt-hour |

| TWh | Terawatt-hour |

| kWh | Kilowatt-hour |

Appendix A

Proof.

Based on Equation (9), we can obtain the Jacobian matrix for our evolutionary system as

The determinants (and traces (of the Jacobian matrix are given by

□

Appendix B

Proof.

The Jacobian matrix of the evolving system under dynamic DRS is

□

Appendix C

Proof.

, ,,, □

References

- Jiao, N.; Evans, S. Secondary use of electric vehicle batteries and potential impacts on business models. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, J. Vehicle product-line strategy under government subsidy programs for electric/hybrid vehicles. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 146, 102221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stekelberg, J.; Vance, T. The effect of transferable tax benefits on consumer intent to purchase an electric vehicle. Energy Policy 2024, 186, 113936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.; Gao, Y.; Li, K.W.; Huang, J. Cooperate or compete? A strategic analysis of formal and informal electric vehicle battery recyclers under government intervention. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2024, 27, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, Y. Assessing the Antecedents, Processes, and Consequences of Sustainable Electric Vehicle Battery Recycling: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2025, 282, 109551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Huang, Z.; Liu, B.; Ma, T. Sustainable lithium supply for electric vehicle development in China towards carbon neutrality. Energy 2025, 320, 135243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadnia, A.H.; Onofrei, G.; Ghadimi, P. Electric vehicles lithium-ion batteries reverse logistics implementation barriers analysis: A TISM-MICMAC approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 174, 105751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Global EV Outlook 2024; IEA: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024 (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Glock, C.H. Decision support models for managing returnable transport items in supply chains: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 183, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moawad, K.; Hummieda, A.; Musamih, A.; Salah, K. Blockchain and NFTs: Revolutionizing critical material recycling from end-of-life lithium-ion batterie. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2025, 27, 200258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, P.A.; Anderson, P.A.; Harper, G.D.; Lambert, S.M.; Mrozik, W.; Rajaeifar, M.A.; Wise, M.S.; Heidrich, O. Risk management over the life cycle of lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 148, 111240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H. What Is the Progress of Power Battery Recycling When the ‘‘Retired Tide’’ is Arriving? 2019. Available online: https://www.d1ev.com/news/shichang/93529 (accessed on 30 June 2019).

- CarNewsChina.com. Analysis of China’s Power Battery Installed Capacity from January to October in 2024. 2025. Available online: https://electrification-solutions.com/analysis-of-chinas-power-battery-installed-capacity-from-january-to-october-in-2024/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Zhu, H.; Hu, J.; Yang, Y. Towards a circular supply chain for retired electric vehicle batteries: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2025, 282, 109556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, Y.-X.; Tian, Y.-X. Collection and recycling decisions for electric vehicle end-of-life power batteries in the context of carbon emissions reduction. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 175, 108869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Recycling mechanisms and policy suggestions for spent electric vehicles’ power battery-A case of Beijing. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 186, 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dong, B.; Ge, J. How can the recycling of power batteries for EVs be promoted in China? A multiparty cooperative game analysis. Waste Manag. 2024, 186, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Ieromonachou, P.; Zhou, L.; Tseng, M. Optimising quantity of manufacturing and remanufacturing in an electric vehicle battery closed-loop supply chain. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2018, 118, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yang, L.; Tian, X.; Li, Y.; Zuo, T. Temporal and spatial analysis for end-of-life power batteries from electric vehicles in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrozik, W.; Rajaeifar, M.A.; Heidrich, O.; Christensen, P. Environmental impacts, pollution sources and pathways of spent lithium-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 6099–6121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Tian, Y. Manufacturer’s carbon abatement strategy and selection of spent power battery collecting mode based on echelon utilization and cap-and-trade policy. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 177, 109079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wei, J. Policy optimization and practical applications in blockchain-enabled electric vehicle battery recycling system. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 204, 111119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Zhu, S.X. Electric vehicle battery capacity allocation and recycling with downstream competition. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 283, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoarau, Q.; Lorang, E. An assessment of the European regulation on battery recycling for electric vehicles. Energy Policy 2022, 162, 112770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khetriwal, D.S.; Kraeuchi, P.; Widmer, R. Producer responsibility for e-waste management: Key issues for consideration–learning from the Swiss experience. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Cong, L.; Hui, Y.; Zhao, D.; Yu, B. Life cycle CO2 emissions for the new energy vehicles in China drawing on the reshaped survival pattern. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 826, 154102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, P.; Salling, K.; Pigosso, D.; McAloone, T. Designing and operationalising extended producer responsibility under the EU Green Deal. Environ. Chall. 2024, 16, 100977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.M.; Nugent, L.M. Charging up battery recycling policies: Extended producer responsibility for single-use batteries in the European union, Canada, and the United States. J. Ind. Ecol. 2016, 20, 1148–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, F.; Saari, U.; Fedoruk, M.; Iital, A.; Moora, H.; Klöga, M.; Voronova, V. An overview of the problems posed by plastic products and the role of extended producer responsibility in Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of China. 2018. Available online: https://www.miit.gov.cn/jgsj/jns/zhlyh/art/2020/art_02610d5fcf774495afb4776cbb1e565b.html (accessed on 2 February 2018).

- Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of China. 2023. Available online: https://www.miit.gov.cn/jgsj/jns/gzdt/art/2023/art_43c4326b13974aa2b78045c85d7bc583.html (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Wei, L. How to facilitate the recycling of retired electric vehicle batteries in China? A policy simulation based on system dynamics. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2025, 27, 3749–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, B.; Li, Y.; Ni, R.; Wang, Y. What influences residents’ intention to participate in the electric vehicle battery recycling? Evidence from China. Energy 2023, 276, 127563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, H.; Tang, J.; Chang, C.; Liu, Z. Optimal recovery model in a used batteries closed-loop supply chain considering uncertain residual capacity. Transp. Res. Part E-Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 156, 102516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnusdei, G.; Gnoni, M.; Sgarbossa, F. Are deposit-refund systems effective in managing glass packaging? State of the art and future directions in Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 851, 158256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Gastaldi, M.; Rosa, P. Recycling of end-of-life vehicles: Assessing trends and performances in Europe. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 152, 119887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X. Public charging station localization and route planning of electric vehicles considering the operational strategy: A bi-level optimizing approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 87, 104153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Li, J.; Liu, L. Solving spent lithium-ion battery problems in China: Opportunities and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 1759–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagnoni, M.; Grazzi, M.; Pieri, F.; Tomasi, C. Extended producer responsibility and trade flows in waste: The case of batteries. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2025, 88, 43–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, J. Bridging the regulatory gap: A policy review of extended producer responsibility for power battery recycling in China. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2025, 86, 101697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Jain, A. Organizational Sustainability: Extended Producer Responsibility Implementation in India. Int. J. Glob. Bus. Compet. 2023, 18, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Sun, B. Exploring the EPR system for power battery recycling from a supply-side perspective: An evolutionary game analysis. Waste Manag. 2022, 140, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, G.; Chen, J. Decisions for power battery closed-loop supply chain: Cascade utilization and extended producer responsibility. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Tan, K. Optimal decisions of closed-loop electric vehicle batteries supply chains under extended producer responsibility policies. Int. J. Syst. Sci. Oper. Logist. 2025, 12, 2437153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, T. Design incentives of extended producer responsibility for electric vehicle producers with competition and cooperation. Omega-Int. J. Manag. Sci. 2025, 133, 103266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faibil, D.; Asante, R.; Agyemang, M.; Addanev, C.; Baah, C. Extended producer responsibility in developing economies: Assessment of promoting factors through retail electronic firms for sustainable e-waste management. Waste Manag. Res. 2023, 41, 117–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclerc, S.; Badami, M. Extended producer responsibility: An empirical investigation into municipalities’ contributions to and perspectives on e-waste management. Environ. Policy Gov. 2024, 34, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flygansvær, B.; Dahlstrom, R. Enhancing circular supply chains via ecological packaging: An empirical investigation of an extended producer responsibility network. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 468, 142948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Sun, Q.; Zhu, X. Optimising express packaging recycling: A tripartite evolutionary game modelling government strategies under extended producer responsibility. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 33, 103510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruess, J.; Garrett, R. Potential effectiveness of extended producer responsibility: An ex-ante policy impact analysis for plastic packaging waste in Belgium, France, and Germany. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 219, 108297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, O.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wei, S. Refund policies and core classification errors in the presence of customers’ choice behavior in remanufacturing. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 3553–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, S.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, C.; Wang, L. Can the deposit-return scheme promote recycling of waste PV modules in China? Analysis of an evolutionary game. Sol. Energy 2023, 265, 112136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, M. Effects of fund policy incorporating Extended Producer Responsibility for WEEE dismantling industry in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 130, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berck, P.; Sears, M.; Taylor, R.; Trachtman, C.; Villas-Bass, S. Reduce, reuse, redeem: Deposit-refund recycling programs in the presence of alternatives. Ecol. Econ. 2024, 217, 108080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Li, X.; Bian, J.; Yang, C. Deposit or reward: Express packaging recycling for online retailing platforms. Omega-Int. J. Manag. Sci. 2023, 117, 102828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Mu, D.; Du, J.; Cao, J.; Zhao, F. Game-based system dynamics simulation of deposit-refund scheme for electric vehicle battery recycling in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 157, 104788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, W.; Nozomu, M.; Adachi, T. Closed-loop supply chain under different channel leaderships: Considering different deposit–refund systems practically applied in China. J. Mater. Cycles Waste 2021, 23, 1765–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Du, J.; Liu, P.; Wang, C.; Hu, X.; Ghadimi, P. Optimal choice of power battery joint recycling strategy for electric vehicle manufacturers under a deposit-refund system. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 7281–7301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhu, X. Incentive strategies for retired power battery closed-loop supply chain considering corporate social responsibility. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 19013–19050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Wang, Y. Research on New Energy Vehicle Power Battery Recycling Deposit System Based on Evolutionary Game Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S.; Huang, G. Optimal deposit-return strategies for the recycling of spent electric automobile battery: Manufacturer, retailer, or consumer. Transp. Policy 2025, 164, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhang, M.; Jin, D.; Ma, P.; Wu, W.; Zhang, X. Decision-making analysis of electric vehicle battery recycling under different recycling models and deposit-refund scheme. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 191, 110109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Li, M.; Huang, G. Optimal Recovery Mode for New Energy Vehicle Battery Recycling Under Government Policies. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2025, 46, 2629–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Jiao, J. Which policy can effectively promote the formal recycling of power batteries in China? Energy 2024, 299, 131445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, W.; Song, Y. Study on the impact of government policies on power battery recycling under different recycling models. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 413, 137492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Ali, A.; Qadir, S.; Shahid, M. Policy and regulatory perspectives of waste battery management and recycling: A review and future research agendas. Waste Manag. Bull. 2025, 3, 301–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Li, M.; Huang, G. Comparisons of government policies for electric automobile battery recycling using system dynamics. Waste Manag. 2025, 203, 114892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Zhao, X.; Gao, H.; Tang, M. A game theory analysis of intelligent transformation and sales mode choice of the logistics service provider. Adv. Prod. Eng. Manag. 2023, 18, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, D. Evolutionary games in economics. Econometrica 1991, 59, 637–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Zhao, D.; Luo, R. Evolutionary game analysis on local governments and manufacturers’ behavioral strategies: Impact of phasing out subsidies for new energy vehicles. Energy 2019, 189, 116064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L. Research on Decision of Echelon Utilization of Retired Power Batteries Under Government Regulation. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Chen, H.; Long, R.; Yang, J. Who will pay for the “bicycle cemetery”? Evolutionary game analysis of recycling abandoned shared bicycles under dynamic reward and punishment. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 305, 917–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Liu, S.; Gong, D.; Cao, G. Optimization decision on informal recycling channel of electric vechicle batteries and supervision strategy. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2019, 17, 1589–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Xu, Y.; Sun, D. An evolutionary game research on cooperation mode of the NEV power battery recycling and gradient utilization alliance in the context of China’s NEV power battery retired tide. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, K.; Hang, Z.; Zhou, D.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, Z. Waste battery-to-reutilization decisions under government subsidies: An evolutionary game approach. Energy 2022, 259, 124835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Tao, Y.; Li, Y. Collection policy analysis for retired electric vehicle batteries through agent-based simulation. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 382, 135269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Hou, H.; Xu, H.; Zhang, M. How to solve the problem of irregular recycling of spent lead-acid batteries in China?—An analysis based on evolutionary game theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 421, 138514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, F.; Zhang, W.; Ke, S.; Wang, X. Multi-agent behavioral strategy game and synergy evolution path of the retired power battery recycling system. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2024, 45, 3993–4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Tan, H.; Xie, J.; Xia, Z.; Liu, L. Design and simulation of a cross-regional collaborative recycling system for secondary resources: A case of lead-acid batteries. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 348, 119181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).