Abstract

This paper explores the impact of sustainability practices (ESG and greenwashing) on profitability, with a special focus on crises, in particular COVID-19. We analyze the post-crisis profitability of sustainable firms, distinguishing between country groups (developed/developing and high voice and accountability/low voice and accountability). We run fixed effects difference-in-differences regressions on a dataset comprising 3832 to 14,652 firm-year observations from 47 stock exchanges. Evidence suggests that firms with a higher ESG during COVID-19 achieved higher profitability afterwards. Environmental score (E) contributed the most to profitability. Although greenwashing improved post-crisis operational performance, its effect on market value is mixed. Countries exhibited different dynamics regarding the sustainability–profitability nexus: firms in developed countries and countries with greater voice and accountability achieved higher post-crisis profitability. In the post-crisis recovery period, this pattern reversed (for ESG) or disappeared (for greenwashing). Overall, companies investing in ESG (E, S, G) during COVID-19 gained substantial benefits, but those engaging in greenwashing were not penalized much, especially those in developed countries and countries with greater voice and accountability. These findings show how institutional and stakeholder-driven pressures can play a critical role in the sustainability–profitability relationship, engendering important implications for managers and policymakers.

1. Introduction

Since 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic, declared as a pandemic by the World Health Organization, has severely affected different regions economically and socially. Despite the crisis manifesting at varying intensities, almost all areas—including sustainability—are impacted. The pandemic is seen as a ‘late lesson’ from an early warning, as it spread through interaction with sustainability-related issues such as climate change [1]. Therefore, during and after the pandemic, the transition to a sustainable society and economy has become the focal point [2]. Along with other challenges such as unequal demand levels [3], companies have been forced to change structurally and financially.

Companies that were not flexible enough to adapt to changes had to exit the market [4]. In particular, the economic contraction caused by the pandemic resulted in companies in emerging markets becoming the most severely affected [2]. So, to what extent did the financially challenged companies in both developed and emerging markets benefit from their sustainability practices? This perspective unveils a research question by demonstrating how the crisis-specific and system-level infrastructure risks faced by various country groups reshape the stakeholders’ assessment of sustainability practices. In this regard, we address a critical gap in the literature by examining the effects of crisis-period sustainability practices such as ESG and greenwashing (GW) on post-crisis profitability and the differences in these effects across country groups based on economic development (developed vs. emerging) and participatory governance (high voice and accountability vs. low voice and accountability). In fact, such a comparison is essential for understanding how institutional and stakeholder-driven pressures play a critical role in the ESG–profitability (along with E, S and G pillars) and GW–profitability relationships. In this respect, we build on various theories, especially crisis theory, which provides a comprehensive lens to explain how institutional structures, stakeholder-driven pressures, and governance-related dynamics shape firms’ responses and valuations in times of uncertainty. As underlined by crisis theory, in times of uncertainty, stakeholders demand transparent and real sustainability commitments from businesses [5]. Additionally, stakeholder-driven pressures may be higher in some countries, which, according to crisis theory, can be explained by higher expectations of transparency and accountability therein during times of crisis. In this context, good performers (e.g., high-ESG firms) are expected to be rewarded while bad performers (e.g., greenwashing firms) are expected to be penalized in the post-crisis period. Beyond being at firm level, a difference in this effect is likely across country groups due to various factors such as strategic alliances and common institutional and supranational regulatory environment. This theoretical discussion requires a deeper investigation into the cross-country differences in a methodologically robust framework.

This study contributes to the literature by offering a robust research design for: (1) analyzing the impacts of the three dimensions of ESG on profitability during crisis periods, (2) performing this analysis comparatively across economically developed and developing countries as well as countries with greater and lower voice and accountability, (3) systematically examining the impact of GW on profitability during and after the crisis period, and (4) performing this analysis comparatively across economically developed and developing countries as well as countries with greater and lower voice and accountability. In this framework, it attempts to contribute to the literature both methodologically and empirically by revealing the differential effects of sustainability practices on profitability in the context of the crisis. A review of existing research reveals that while there are some studies that focus on specific economic groups during the crisis period, the literature on the ESG–profitability and GW–profitability nexus comparing economically developed and developing countries or greater and lower voice and accountability countries is limited. Such an analysis not only contributes to academic achievement but also generates important insights for managers, policymakers, and investors.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Impact of Sustainability Practices on Profitability in Normal and COVID-19 Periods

2.1.1. Normal Periods

Research on the ESG–profitability relationship has yielded mixed results, with both positive/significant [6,7,8] and negative/insignificant associations [9,10] reported. Studies identifying a negative relationship generally align with agency and shareholder theories, which suggest that ESG investments harm shareholders through increased costs [11,12], signaling inefficiency [13], while studies that find a positive relationship align with institutional and legitimacy theories, which suggest that ESG helps maintain legitimacy by bringing about compliance with environmental norms, values, and expectations [14,15].

Regarding greenwashing (GW) and profitability, some researchers document a positive relationship [16,17,18], while others document a negative or insignificant relationship [8,19,20,21,22,23]. In these articles, the information asymmetry in stakeholder identification processes and some of the benefits obtained through GW (promoting a good social image, easing corporate resource constraints, etc.) are highlighted. These facts corroborate the mixed effects (positive or negative) of GW on profitability. From a theoretical perspective, according to agency theory, managers may tend to increase GW practices to reduce environmental pressure from stakeholders and enhance their legitimacy, but principals perceive this as a risk to company’s reputation [18]. However, none of these studies in the GW–profitability literature focus specifically on a crisis period like COVID-19.

2.1.2. COVID-19 Period

Several studies investigate the ESG–profitability relationship during the pandemic (please see Table 1 for a summary of the literature on the impact of ESG (E, S, G) and GW on profitability). Some researchers find that ESG positively affected profitability metrics such as return on assets (ROA), return on equity (ROE), Tobin’s Q (TQ), or stock returns during the COVID-19 period [24,25,26,27,28] or afterwards [29]. Moreover, it is argued that investors can use ESG performance as a signal of future returns and risk reduction since ESG investments can reduce price volatility and downside risk [26,30]. ESG increases investor confidence and strengthens social image [27,31], increases the resilience and stability of the firm [27,32], and contributes to its survival [26], which can be vital in economic downturns. Ref. [24] shows that sustainable firms had better stock performance than other firms during the pandemic. Moreover, ESG engagement can make the firm more immune to shocks [32]. Hence, these studies assert that companies with higher ESG scores are least affected by the crisis.

However, investigating the ESG–profitability relationship only for the pandemic year ignores the long-term impact of sustainability practices. According to [33], “exaggerated” or “unrealistic” ESG claims during the crisis create long-term reputational risks. According to legitimacy theory, these claims trigger erosion of trust and deterioration of legitimacy, which further leads to a long-term loss of reputation and corporate value [34]. By contrast, in line with crisis theory, fulfilled ESG claims during the crisis build trust and legitimacy [29], which may be beneficial to sustain a long-term reputation and enhance corporate value. Moreover, according to resource-based theory, ESG activities create intangible assets such as reputation [35], which in turn increases competitive advantage and corporate value [36]. However, the return of corporate reputation or social legitimacy to the firm is more likely to materialize in the long run [37]. Since firms gradually generate these positive outcomes by continuously layering their valuable activities over time, such gains are not acquired immediately. Nevertheless, investigating post-crisis impact for identifying long-term risks and rewards is largely overlooked in earlier work. Table 1 gives a summary of the studies examining the direct impact of sustainability practices (ESG, E, S, G, and GW) on profitability in a comparative way.

Based on the literature described above, we first conjecture that market value was positively influenced by ESG efforts during the crisis period. There may be several reasons for this. First of all, the increasing importance of sustainability practices for both investors and consumers in recent years is noteworthy. Consumers prioritize sustainability more in purchasing decisions, and investors invest more in highly sustainable companies. This means that ESG can be associated with higher profits and stock prices. Secondly, during the COVID-19 period, companies’ ESG efforts decreased considerably [38]. Therefore, companies that could allocate resources to ESG activities and keep their ESG scores relatively high may have earned more profits during the recovery period. Thirdly, ESG investments may also immunize firms against shocks [32] and help firms to stay in the market [26], which is critical especially in crisis periods. This immunization can be gained through increased investor confidence and strengthened image, which can provide superior benefits in the long run [39]. Finally, ESG can leverage short-term operating costs that can be a heavy burden in times of crisis. However, examining the impact on future rather than current profitability in times of crisis would be an important attempt in this investigation. Since it can be considered as an intangible-asset-driven strategy, ESG spending, from a stakeholder-centric view, can be tolerated by investors and result in higher market value. We also conjecture that market value was positively influenced by each pillar score (E, S, and G) during the crisis period, with some differences eventually emerging across these subscores. Scholars find mixed results (positive/negative/insignificant) for the effect of ESG on profitability depending on the ESG subscore [30,32,37,40,41]. Each subscore can have a different impact on profitability; however, the role of the pandemic in this differentiation is undeniable. As the pandemic spread through interaction due to sustainability-related issues such as climate change, stakeholders increased their interest in environmental issues [41]. The recent pandemic experience made environmental initiatives more visible, potentially leading investors to place disproportionately higher values on green and/or greenwashing firms, consistent with the idea of the availability heuristic [42]. Despite the pandemic being most acutely felt in 2020, its effects are clearly long-lasting and enduring. Therefore, the availability bias regarding environmental initiatives may have persisted in the post-crisis period.

With the pandemic, not only environmental, but also social and governance issues were central to stakeholders’ agendas and impacted their daily lives. For example, since the pandemic created challenges in working conditions, how companies approached social issues such as employee’s work–life balance and financial struggles became vital. Moreover, adopting a stakeholder-centric rather than a shareholder-centric focus was common, hence, stakeholder demands regarding governance such as accurate information and effective communication became central.

To conclude, given the increasing stakeholder interest and companies’ transformation towards sustainability, ESG as well as each subscore can be positively associated with post-crisis profitability. Therefore, the first set of hypotheses is as follows:

H1a.

Firms with high ESG (as well as E, S, and G) performance during the crisis had a significant increase in their operational performance (measured by ROA) in the post-crisis period.

H1b.

Firms with high ESG (as well as E, S, and G) performance during the crisis had a significant increase in their market value (measured by TQ) in the post-crisis period.

Negative information about the firm due to its greenwashing (GW) practices can increase unsystematic risk by reducing corporate environmental legitimacy [13], leading to stronger negative market reactions [34] and loss of trust [43]. However, increasing GW values indicates that firms focus on short-term profit maximization during the crisis by taking these potential negative effects into consideration. Whether greenwashers actually confronted these negative effects and achieved more short-term profits in the post-crisis period is a topic that has not been sufficiently addressed in the literature.

According to crisis theory, one of the issues that can undermine stakeholder trust in times of crisis is the inconsistency between discourse and action [5]. Moreover, in times of crisis, excessive image efforts and over-communication can be seen as a lack of sincerity [44]. Engaging in GW during crisis periods may involve long-run reputational risk [33], thereby resulting in stakeholder reaction [45,46]. In addition, with COVID-19, stakeholders expected consistency, transparency, and real action in their green communications, which has led to strict regulations with sanctions [47]. These facts signal that stakeholders demand real and proper sustainability commitments more in times of crisis. Therefore, GW can be expected to reduce profitability in the post-crisis period.

Based on these views, the second set of hypotheses is as follows:

H2a.

Firms that engaged more in GW during the crisis had a significant decrease in their operational performance (measured by ROA) in the post-crisis period.

H2b.

Firms that engaged more in GW during the crisis had a significant decrease in their market value (measured by TQ) in the post-crisis period.

2.2. Country-Level Differences in the Impact of Sustanability Practices on Profitability in the Post-Crisis Period

Many studies report country-level differences in the ESG–profitability relationship (see Table 1). There may be several reasons for regional disparities. To start, non-financial factors have not yet been fully integrated into corporate decision-making processes in developing countries [48], or even if they have been in some countries, there are financial constraints [4,9,38]. Moreover, stakeholders may have different understandings and approaches to sustainability issues that can affect company valuations. For instance, investors may not be fully aware of ESG practices [49], may have limited access to information [50], may prioritize financial returns over ESG factors, or may prioritize only certain ESG sub-factors [51]. Furthermore, economic differences among countries lead to varying levels of societal development, which in turn affects the maturity of sustainability practices and stakeholder demand [13]. Stakeholders in wealthy and developed countries are more likely to prioritize sustainability issues and more willing to pay for ESG issues [52], while stakeholders in developing countries are more likely to focus on economic survival and short-term profitability [51]. Countries with developed economies and high income account for a significant share of trade, GDP, and FDI, which promote sustainable development policies and transparency [51,53]. Countries with higher economic growth can assist companies to invest more effectively in ESG, which can reduce ESG-related costs in the long term [54]. These issues can play a vital role in economically developed countries and can affect ESG–profitability relationship.

To elaborate, developed countries have stricter regulations, more mature regulatory systems, stronger macroeconomic frameworks, and higher risk assessment capacity than developing countries [2,50]. Capital markets in developed countries have higher investment flows, so investors are more likely to demand comprehensive ESG data [55]. Developed countries have many activist consumers and pressure to obey global reporting standards [13]. Such situations may push firms to share more ESG information under high ESG pressure [50]. Thus, as stakeholders’ access to ESG-related information expands, their awareness increases. In line with stakeholder theory, stakeholders’ prioritization of ESG factors and their more conscious and enthusiastic attitude towards ESG may result in firms with higher valuations [56].

Economic differences can arise not only in stable years but also in challenging periods. During COVID-19, many companies experienced financial difficulties and were unable to survive, more prominently in developing economies [4,38]. Thus, in such companies, better ESG performance may be associated with a longer recovery period. In the short term, it may further strain the financial resources needed to stay afloat and may reduce resilience to the crisis for companies in developing economies more than in developed economies. Furthermore, companies tend to be more inclined to adopt comprehensive sustainability practices in developed countries, which usually have more robust regulatory frameworks and effective governance systems. Moreover, during crisis periods, in developing economies, since the primary focus is on shareholder wealth rather than stakeholder wealth [57], there may be less inclination by firms towards cost-increasing investments such as ESG [58]. This can reduce the ESG competitiveness of firms in developing countries more than in developed countries. These facts may allow firms located in economically developed countries to achieve higher profitability (obtain a higher return from their ESG investments) in post-crisis periods than firms in developing countries. Moreover, according to slack resources theory, when resources are limited, managers face trade-offs [59]. Because of these trade-offs, the marginal benefit obtained from sustainability practices is weakened. Managers in developing countries are more likely to face this trade-off in times of crisis. Moreover, signaling theory argues that not all ESG signals are interpreted equally [60]; hence, ESG credibility depends on the institutional ecosystem where the company is located.

In summary, we deepen the contextual effects, which have been addressed limitedly in the literature, by revealing more clearly how structural differences across developed and developing countries influence stakeholders’ valuation processes for firms.

Based on these views, the third set of hypotheses is as follows:

H3a.

Firms with higher ESG (as well as E, S, and G) during the crisis improved their operational performance (measured by ROA) in the post-crisis period more in economically developed countries than their equivalents in economically developing countries.

H3b.

Firms with higher ESG (as well as E, S, and G) during the crisis improved their market value (measured by TQ) in the post-crisis period more in economically developed countries than their equivalents in economically developing countries.

Country differences can be significant, not only in terms of the ESG–profitability nexus but also in terms of the GW–profitability nexus. According to [17], regional disparities in environmental regulations facilitate GW adoption. Weak regulations, financial constraints, and low stakeholder pressure may be more pronounced for firms in developing countries in times of crisis. This may lead to an easier adoption of unethical behaviors such as greenwashing. Hence, GW practices during COVID-19 may have been more prevalent in emerging economies [38]. Thereby, related legitimacy losses during the COVID-19 crisis might be more severe in developing countries afterwards compared to developed countries, which usually have more established legal systems and institutional infrastructures. Within a holistic framework backed by legitimacy, crisis, and resource-based theories, we inquire whether these institutional and infrastructural effects result in a long-term loss of reputation [33] and corporate value [34]. We therefore expect that developed (developing) countries with above-average GW practices during COVID-19 were penalized less (more) in the post-crisis period than their equivalents in developed economies.

Based on these views, the fourth set of hypotheses are as follows:

H4a.

Firms with higher GW during the crisis improved their operational performance (measured by ROA) in the post-crisis period more in economically developed countries than their equivalents in economically developing countries.

H4b.

Firms with higher GW during the crisis improved their market value (measured by TQ) in the post-crisis period more in economically developed countries than their equivalents in economically developing countries.

Developed countries generally have stricter regulations, more mature regulatory systems, stronger macroeconomic frameworks, and higher risk assessment capacity than developing countries [2,50]. This, in turn, can influence the impact of sustainability practices on post-crisis profitability, since institutional and stakeholder-driven pressures are key factors in this relationship. However, grouping countries based on other standards such as voice and accountability (V&A) instead of economic development might be better for reflecting stakeholder-driven pressure. Indeed, V&A is associated with higher public participation in decision-making, hence, designates higher standards in terms of transparency, public pressure, and consumer awareness [61] that may result in more awarded or penalized sustainability efforts for firms, especially in crisis periods. For instance, although the US, Japan, and Singapore are developed economies, they are not among the top countries in terms of voice and accountability. According to crisis theory, stakeholders have higher expectations of transparency during crises [5], which might also affect ESG valuation. Therefore, we argue that high ESG scores (as well as ESG pillar scores) will have a strong positive impact on post-crisis profitability for firms in countries with higher levels of V&A than in others.

Based on these views, the fifth set of hypotheses are as follows:

H5a.

Firms with higher ESG (as well as E, S, and G) during the crisis improved their operational performance (measured by ROA) in the post-crisis period more in high voice and accountability countries than their equivalents in low voice and accountability countries.

H5b.

Firms with higher ESG (as well as E, S and G) during the crisis improved their market value (measured by TQ) in the post-crisis period more in high voice and accountability countries than their equivalents in low voice and accountability countries.

Weak regulations, financial constraints, and low stakeholder pressure may also encourage greenwashing (GW). Ref. [62] argues that firms in countries with higher regulatory quality face more extensive market pressure from the institutional environment, which subsequently limits their GW involvement. Extending institutional theory, authors mention that “the symbolic responses companies provide to stakeholders can be mitigated by support from governments and regulators”, usually referred to as coercive isomorphism. By exerting coercive isomorphism, governments with high regulatory quality enforce strict environmental laws and transparency requirements, forcing firms to achieve legal accountability, authentic credibility, and measurability [62]. As a result, firms in countries with greater V&A may be less inclined to practice GW, especially in times of crisis. We therefore expect that companies with above-average GW practices during COVID-19 in high V&A countries were penalized less in the post-crisis period than their equivalents in low V&A countries.

Based on these arguments, the sixth set of hypotheses is as follows:

H6a.

Firms with high GW during the crisis improved their operational performance (measured by ROA) in the post-crisis period more in high voice and accountability countries than their equivalents in low voice and accountability countries.

H6b.

Firms with high GW during the crisis improved their market value (measured by TQ) in the post-crisis period more in high voice and accountability countries than their equivalents in low voice and accountability countries.

According to crisis theory, companies can develop trust-based communication with stakeholders during crisis through efficient ESG-related investments [29] or enhanced corporate transparency [5]. However, once the crisis is over, this may not hold or even reverse. Based on these insights, we examine whether the impact of high ESG (as well as E, S, and G) and GW during the recovery period (2021) on subsequent-year (2022) profitability is the same across developed and developing countries as well as countries with high V&A and low V&A. In other words, we test whether the impact of sustainability practices on profitability is specific to the crisis year, or also holds in the recovery year.

Based on these arguments, the seventh and eight sets of hypotheses are as follows:

H7a.

Firms with high ESG (as well as E, S, and G) during the recovery year (2021) improved their subsequent-year operational performance (measured by ROA) less in developed countries (alternatively, in countries with high voice and accountability) than their equivalents in developing countries (alternatively, in countries with low voice and accountability).

H7b.

Firms with high ESG (as well as E, S, and G) during the recovery year (2021) improved their subsequent-year market value (measured by TQ) less in developed countries (alternatively, in countries with high voice and accountability) than their equivalents in developing countries (alternatively, in countries with low voice and accountability).

H8a.

Firms with high GW during the recovery year (2021) improved their subsequent-year operational performance (measured by ROA) less in developed countries (alternatively, in countries with high voice and accountability) than their equivalents in developing countries (alternatively, in countries with low voice and accountability).

H8b.

Firms with high GW during the recovery year (2021) improved their subsequent-year market value (measured by TQ) less in developed countries (alternatively, in countries with high voice and accountability) than their equivalents in developing countries (alternatively, in countries with low voice and accountability).

Table 1.

Comparison of the studies examining the direct impact of sustainability practices (ESG, E, S, G, and GW) on profitability.

Table 1.

Comparison of the studies examining the direct impact of sustainability practices (ESG, E, S, G, and GW) on profitability.

| Panel A: Normal Period—ESG | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author(s) | Period | Sust. Practice | Profitability Metric | Country | Eco/Reg Group | Effect |

| Sahut and Pasquini-Descomps, 2015 [63] | Entire | ESG | RET | Multiple | Mixed | |

| Velte, 2017 [64] | Entire | ESG, E, S, G | ROA, TQ | Germany | Mixed | |

| Dalal and Thaker, 2019 [7] | Entire | ESG | ROA, TQ | India | (+) | |

| Ting et al., 2019 [65] | Entire | ESG, E, S, G | ROE, TQ, P/E | Multiple | Dev/Emg | Mixed |

| Garcia and Orsato, 2020 [66] | Entire | ESG | ROA, DCF | Multiple | Dev/Emg | Mixed |

| Junius et al., 2020 [10] | Entire | ESG | ROA, ROE, TQ, P/E | Multiple | (?) | |

| Duque-Grisales and Aguilera-Caracuel, 2021 [9] | Entire | ESG, E, S, G | ROA | Multiple | (−) | |

| Rahi et al., 2021 [67] | Entire | ESG, E, S, G | ROE, ROIC, EPS | Multiple | Nordic | Mixed |

| Aydoğmuş et al., 2022 [68] | Entire | ESG, E, S, G | ROA, TQ | Multiple | Mixed | |

| Bruna et al., 2022 [69] | Entire | ESG | CFPIND | Multiple | Europe | Mixed |

| Liu et al., 2022 [70] | Entire | ESG, E, S, G | ROA | China | Mixed | |

| Zahid et al., 2022 [71] | Entire | ESG, E, S, G | ROA, REV | Multiple | Europe | Mixed |

| Chen et al., 2023 [6] | Entire | ESG, E, S, G | ROA, ROE | Multiple | (+) | |

| Hamad and Cek, 2023 [72] | Entire | ESG, E, S, G | ROA, ROE, EPS | Multiple | OECD | Mixed |

| Lee and Raschke, 2023 [8] | Entire | ESG | NPM | Multiple | (+) | |

| Shin et al., 2023 [73] | Entire | ESG, E, S, G | ROA | Multiple | (+) | |

| Candio, 2024 [74] | Entire | ESG, E, S, G | ROA, ROE, EBITM, EPS, P/E, PRI | Multiple | Europe | Mixed |

| Sidney and Liao, 2025 [22] | Entire | ESG | ROA, ROE, TQ | China | (?) | |

| Panel B: Normal Period—GW | ||||||

| Author(s) | Period | Sust. Practice | Profitability Metric | Country | Eco/Reg Group | Effect |

| Walker and Wan, 2012 [23] | Entire | GW | ROA | Canada | (−) | |

| Du, 2015 [21] | Entire | GW | CAR | China | (−) | |

| Testa et al., 2018 [75] | Entire | GW | ROA, ROE, MBVE | Multiple | (?) | |

| Darendeli et al., 2022 [20] | Entire | GW | ROA, LOSS | Multiple | (−) | |

| Chen and Dagestani, 2023 [16] | Entire | GW | TQ | China | (+) | |

| Lee and Raschke, 2023 [8] | Entire | GW | NPM | Multiple | (?) | |

| Li et al., 2023 [17] | Entire | GW | ROA | China | (+) | |

| Brindelli et al., 2024 [19] | Entire | GW | RET, ROA, TQ | Multiple | Europe | (−) |

| Purnamasari and Umiyati, 2024 [18] | Entire | GW | ROA, ROE, TQ | Indonesia | (+) | |

| Sidney and Liao, 2025 [22] | Entire | GW | ROA, ROE, TQ | China | (?) | |

| Panel C: COVID-19 Period—ESG | ||||||

| Author(s) | Period | Sust. Practice | Profitability Metric | Country | Eco/Reg Group | Effect |

| Albuquerque et al., 2020 [31] | Pre/Post | ESG | RET, VOL, ROA, OPM, AT | N. America | Mixed | |

| Demers et al., 2020 [76] | During/Post | ESG | BHAR | America | (−/?) | |

| Broadstock et al., 2021 [30] | Entire/During | ESG, E, S, G | CAR | China | Mixed | |

| Engelhardt et al., 2021 [32] | During | ESG, E, S, G | CAR | Multiple | Europe | Mixed |

| Hwang et al., 2021 [37] | Pre/During | ESG | ROA | South Korea | (+) | |

| Takahashi and Yamada, 2021 [77] | Pre/During | ESG | BHAR | Japan | Mixed | |

| Yoo et al., 2021 [41] | Pre/During/Post | ESG, E, S, G | RET, VOL | Multiple | Mixed | |

| Białkowski and Sławik, 2022 [78] | During/Post | ESG, E, S, G | RET | New Zealand | (−/?) | |

| El Khoury et al., 2022 [79] | During | ESG, E, S, G | ROA, ROE, RET, P/B | Multiple | G20, Dev/Emg | Mixed |

| Li et al., 2022 [26] | During | ESG | CAR | China | (+) | |

| Aqabna et al., 2023 [80] | Entire/During | ESG, E, S, G | ROA, ROE, TQ | Multiple | MENA | Mixed |

| Al Amosh and Khatib, 2023a [81] | Pre/During | ESG | ROA, ROE, EPS | Multiple | G20 | (+) |

| Bodhanwala and Bodhanwala, 2023 [82] | Entire/During | ESG | MV, TQ, P/B, BHAR | India | (?) | |

| Cardillo et al., 2023 [24] | During | ESG | RET, VOL | Multiple | Europe | (+) |

| Lin et al., 2023 [83] | During | ESG | ROA, TQ | China | Mixed | |

| Liu et al., 2023 [70] | Entire/During | ESG, E, S, G | RET, VOL, LIQ | Japan | Mixed | |

| Aksoy and Yilmaz, 2024 [29] | Pre/During/Post | ESG, E, S, G | ROA | Multiple | (+) | |

| Cheng et al., 2024 [40] | Pre/Post | ESG, E, S, G | EV/EBT | China | Mixed | |

| Gao and Geng, 2024 [84] | During | ESG, E, S, G | CAR | China | (+) | |

| Le, 2024 [25] | During | ESG | ROA | Multiple | SE Asia | (+) |

| Gabr and ElBannan, 2025 [85] | Entire/During | ESG, E, S, G | FO (ROA, ROE) | Multiple | Mixed | |

| Yadav et al., 2025 [28] | During | ESG | RET | America | (+) | |

Notes: Abbreviations and other explanations are as follows: Entire: entire or normal period; Pre: Pre-COVID-19 Period; Post: Post-COVID-19 Period; During: During COVID-19 Period; ESG: overall ESG score; GW: Greenwashing score; E, S, G: ESG subscores; RET: Stock Returns; TQ: Tobin’s Q; ROA: Return on Assets; ROE: Return on Equity; MBVE: Market-to-Book Value of Equity; P/E: Price to Earnings; OPM: Operating Profit Margin; AT: Asset Turnover; BHAR: Buy-and-Hold Abnormal Returns; DCF: Discounted Cash Flows; ROIC: Return on Invested Capital; EPS: Earnings Per Share; VOL: Volatility; LOSS: An indicator equal to 1 if a firm’s ROA in year t − 1 is negative; P/B: Price to Book; CFPIND: an overall score based on liquidity, solvency, activity, leverage, operating efficiency, and profitability; REV: Revenue; MV: Market Value; CAR: Cumulative Abnormal Returns; NPM: Net Profit Margin; LIQ: Liquidity; EBITM: Tax Margin; PRI: Share Price; EV/EBT: Enterprise Value over EBITDA; ECO/REG: Economical or Regional Grouping; Dev: Developed Country; Emg: Emerging/Developing Country; MENA: MENA Region; OECD: OECD Countries; (+): Positive Effect; (−): Negative Effect; (?): Insignificant Effect; (−/?): Both negative and insignificant effect; Mixed: Either positive, negative, or insignificant effect (based on the periods, ESG or ESG subscores, profitability metrics, or countries).

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Variables

To measure the direct and indirect effects (through moderators) in the sustainability practice–profitability relationship, we identify several dependent and independent variables. To start with, return on assets (ROA) and Tobin’s Q (TQ), widely used in the sustainability literature [86,87,88], are identified as the dependent variables. While ROA typically reflects short-term financial performance, TQ is more commonly associated with evaluating long-term financial performance. Since ROA is an accounting-based measure and TQ is a market-based measure, profitability can be evaluated from different angles. This alternative allows for a more robust performance evaluation, since each profitability measure is subject to some problems (e.g., manipulation, window dressing).

The main independent variable is ESG (environmental, social and governance score), while alternatives include ESG subscores (E, S, and G scores) and GW (greenwashing score). ESG score and ESG subscores (E, S, and G) are calculated and provided by LSEG. We calculate GW by finding the difference between the Green Communication Index (GCI) and Green Practice Index (GPI) following [75]. If the GCI is higher than the GPI, it indicates that these companies engage in greenwashing in that year.

In order to observe the difference between country groups implied in H3a to H8b, interactions are used [89]. Hence, a moderator variable is specified for comparing economically developed and developing countries: high voice and accountability (HVA) and low voice and accountability (LVA) countries. Economic grouping of countries (developed vs. developing) follows the classification provided by MSCI and FTSE/Russell with a few exceptions (countries are identified as “developed” if they are labeled as developed by both the MSCI and FTSE/Russell indices, and “developing” otherwise. Therefore, S. Korea and Poland are classified as “developing”). These two indices group countries every year by evaluating their equity markets. Accordingly, countries can be classified as developed, emerging, frontier, or standalone market. We simply separate countries into two groups, developed (DEV) or emerging (EMG), since our country list consists mostly of these two groups.

Other groupings of countries (HVA vs. LVA) follow the classification provided by the World Bank based upon World Governance Indicators. The World Bank data source provides year-by-year voice and accountability (V&A) scores that cover the perceptions of the extent to which each country’s citizens are able to participate in choosing their government and have freedom of expression, freedom of association, and free media. After sorting countries according to their V&A score, we label the countries in the higher (lower) tertile as HVA (LVA), leaving aside the middle tertile for the purpose of prudence.

We employ several control variables that are commonly used in the sustainability literature related to financial performance. According to [79], for larger firms and firms with lower leverage, ESG can better be related with profitability. In addition, asset turnover [90] and board characteristics [91] can significantly affect the ESG–profitability or GW–profitability relationship. Among others, [92] indicate that firm- and industry-specific characteristics such as firm size, debt, firm age, and board characteristics are among the most common control variables in the research about the impact of sustainability on financial performance. To this list, we add asset turnover ratio [90] because it shows the capacity of the company to generate revenue relative to assets, thereby can be directly associated with operational performance as well as market value. Therefore, we include the following control variables in all the models: firm size (LSZE), asset turnover (ATR), leverage ratio (LEV), firm age (LAGE), number of board meetings (LNBM), and board gender diversity (BGD). These control variables are important for isolating the treatment effect within the difference-in-differences design.

3.2. Data

Annual firm-level data are collected through LSEG Workspace (formerly known as Refinitiv Eikon). Initially, we collected data from 2018 to 2022 to see the patterns and trends. While the main analysis requires data for the years 2020, 2021, and 2022, we use the data for 2018 and 2019 to see the trend in sustainability and to run placebo analysis more accurately. We take 2020 as the COVID-19 period and 2021 and 2022 as the post-COVID-19 period.

In terms of data manipulation, we removed double counting observations and winsorized the data by 0.5% in the upper and lower percentiles. The final sample consists of 2327 to 8227 firms from 47 different stock exchanges and 3832 to 14,652 firm-year observations, depending on the analysis. Regarding country groups, our dataset includes observations of 8781 (3875) firms from 22 developed (25 developing) countries and 3730 (3278) firms from 18 high V&A (14 low V&A) countries. This provides a sufficiently fair number of observations with relative homogeneity achieved through country grouping and fixed effect modeling, which strengthens the generalizability of the results.

The dataset consists of sustainability indicators such as ESG score, ESG subscores (E, S, and G), and GPI (Green Practice Index); sustainability communication indicators such as GCI (Green Communication Index); financials such as sales revenue, total assets, total liabilities, market capitalization, and net income; and company information such as country of headquarters, date of establishment, and board statistics such as number of board meetings and number of female and male board members. From this dataset, we obtain GW as the difference between GCI and GPI [75]; natural logarithm of company size (LSZE) [10,64,69,75]; asset turnover rate (ATR) by dividing total assets by sales [90]; leverage ratio (LEV) by dividing total liabilities by total assets [10,64,69,75]; natural logarithm of firm age (LAGE) [10,90]; natural logarithm of number of board meetings (LNBM) [91]; and board gender diversity (BGD) as a percentage of female board members [91]. COVID-19 period is set as 2020 following the literature [24,29,79,82] and the post-crisis period as 2021 and 2022 because ESG actions are generally intended to improve intangible assets [39] and financials over the long term.

3.3. Empirical Model and Estimation Procedure

To assess the impact of an intervention or crisis, we use the revised version of the difference-in-differences (DID) regression model widely recognized in the literature [93] as follows. First, we run parallel-trend tests and placebo analysis to decide the suitability of difference-in-differences methodology. To check whether the parallel-trend assumption holds, we adopted an event-study approach. Parallel-trend test results mostly reveal no significant trend difference between our treatment and control groups in the pre-COVID-19 period [94,95] except for a few models (ESG on TQ for 2022; E on TQ for 2022; S on ROA for 2021). Still, to measure the reliability of this preliminary finding, we conduct a placebo test using a dummy treatment year (2019) as a placebo shock year when the treatment (COVID-19) had not yet occurred. By taking 2019, we re-estimated the treatment effect as if the shock had taken place in that year. The test result indicates that placebo interaction terms are insignificant for all dependent variables and all treatment groups, meaning that difference-in-differences (DID) estimates are not random [95]. These findings show that the limited pre-trend volatility observed in some models in the event-study results do not exhibit a systematic bias. Therefore, DID seems to be an appropriate design.

For representing the COVID-19 period in which the effects of the 2020 crisis were felt most severely, firms ranked above (below) the median in terms of their sustainability variable (ESG, E, S, G, or GW) are classified as treatment (control) group. This classification does not generate outlier variation because symmetrical halves of the same distribution ensure natural comparability. Moreover, the time dimension distinguishes the COVID-19 period (2020, time = 0) from the post-COVID-19 period (2021, alternatively 2022, time = 1). The treatment effect is captured by the interaction between the treatment-group indicators and the post-COVID-19 dummy (e.g., [Treat (X) × Post] where X is one of ESG, E, S, G, and GW). We incorporate DEV and HVA dummies as moderators to show the interaction with the treatment effect.

We perform the DID analysis with a fixed effects (FE) estimator since the measured effects can be explained by fixed firm characteristics. The FE estimation improves the quality of the model and reduces concerns about omitted-variable bias. The Hausman test result confirms the validity of FE modeling.

The FE-based DID model designed to capture the direct impacts of crisis-period ESG (as well as E, S, and G) and GW on post-crisis profitability (H1a, H1b, H2a and H2b) is shown in Equation (1).

where Y is profitability (either ROA or TQ), X is one of the sustainability practices (ESG, E, S, G, or GW), LSZE to BGD are control variables, and e is the error term.

In the equation, a positive (negative) treatment effect, i.e., β1 > 0 (β1 < 0), means that firms with a higher crisis-year ESG (E, S, and G) or GW score had a relatively better (worse) financial performance in 2021 or 2022. β2 to β7 show the impacts of control variables, and αi and λt capture firm and year FEs, respectively.

Given in Equation (2), the second model captures the impact of moderators used to test hypotheses H3a to H6b.

where MOD is country group (either DEV or HVA).

In the equation, a positive (negative) treatment effect, i.e., β3 > 0 (β3 < 0), means that firms with a higher crisis-year (2020) ESG (E, S, and G) or GW score in DEV (alternatively in HVA) countries had a relatively better (worse) profitability than their equivalents in EMG (alternatively in LVA) countries in 2021 or 2022.

To test hypotheses H7a, H7b, H8a, and H8b, we use exactly the same model, but run it only for the post-COVID-19 period. In detail, a positive (negative) treatment effect, i.e., β3 > 0 (β3 < 0), means that firms with a higher post-crisis-year (2021) ESG (E, S, and G) or GW score in EMG (alternatively in LVA) countries had a relatively better (worse) profitability in the subsequent year (2022) than their equivalents in DEV (alternatively in HVA) countries.

One of the core challenges in empirical modeling is endogeneity. In order to control for potential endogeneity, we take some precautions. First, we employ several control variables in the models as highlighted in the sustainability literature (explained in Section 3.1). Besides the theoretical context, we assess validity by comparing the R2s of the models with and without control variables. This step is important for preventing omitted-variable bias and alleviating potential endogeneity problems. Only in one specification out of many, the inclusion of a variable (LAGE) marginally decreases model fit. Nonetheless, given its strong relevance in the literature and its significance in ESG specifications, all the control variables (including LAGE) are retained in the final specifications. Second, although our analysis does not rely on additional macro-level indicators, firm-fixed effects (FEs) and year FEs do account for exogenous sources of variation. Our regression models incorporate firm-specific characteristics that reflect persistent structural differences (e.g., board management quality) and incorporate year-specific characteristics that reflect macroeconomic fluctuations (e.g., changes in government policies). With year FEs, external factors such as economic and macro-institutional differences across countries can be controlled. We absorb these factors by using a combination of firm and year FEs in all of the models [94,96]. Note that using FEs reduces the likelihood of omitted-variable bias and alleviates the potential endogeneity concern, thereby improving the quality of the model. Third, we perform several prediagnostic tests to assess the validity of the regression assumptions. For instance, Breusch–Pagan and Wooldridge tests reveal that the data are not free from heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation. To account for this problem, we use heteroskedasticity-robust (HC1) standard errors [97,98] and clustered standard errors at the firm level [99]. Confirmed by several diagnostic checks (parallel-trend analysis, placebo-year tests, heteroskedasticity tests, autocorrelation tests, Hausman tests), we ensure that all the models are conceptually well specified and empirically valid.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Among others, [82] show that ESG investments gradually rise over years. Displayed in Table 2, the ESG scores of 3026 firms included in the dataset exhibit a parallel uptrend from 2018 to 2022. Though not necessarily matched with ESG investments, the rapid increase in ESG scores is related to the growing demand for sustainable products and services or ethical expectations from a consumer perspective. From an investor perspective, this increase is related to the growing demand for green investments and ESG funds. Note that the increase in ESG scores is not specific to the COVID-19 period, but reveals a general trend.

Table 2.

(a) Descriptive statistics about sustainability practices (by year). (b) Descriptive statistics about sustainability practices during and after the COVID-19 period per country (with country groupings).

Given the increasingly negative attitude of various stakeholders towards unethical sustainability practices and the measures taken by governments against these practices, one might expect GW to decline from year to year. However, in 2022, the average GW score of the firms in our sample is 16%. Converting the maximum GW score to 100, which can be seen in the table, the score reaches its maximum value in 2022, indicating that GW practices are being adopted by companies more and more. Interestingly, although the biggest leap was from 2018 to 2019, it is noteworthy that the growth rate of GW scores is higher than that of ESG scores. Looking at the differences between each ESG subscore, the fastest growth is in E, S, and G scores. Considering especially the change from 2021 to 2022, the upward trend in the E score, the stability in the S score, and the downward trend in the G score are striking.

Alternatively, Table 2b explores descriptive statistics about sustainability practices by country for the COVID-19 period (2020–2022). According to the table, average ESG values exhibit marked differences. For instance, Saudi Arabia (34.1), UAE (37), China (39.3), and the USA (41.9) have low averages, whereas Spain (67.7), Portugal (64.8), the Netherlands, and Turkey (54.9) have high averages. Results are similar for median values. Note that a large portion of both ESG and GW data comes from a few countries (e.g., 8974, 3353, 1514, and 1467 observations for ESG from USA, China, UK, and India, respectively) while other countries’ share within the dataset is considerably smaller (e.g., 15, 16, 28, and 29 observations for ESG from Malta, Hungary, Iceland, and Cyprus). In general, ESG (GW) scores are higher (lower) in developed countries, with some exceptions (e.g., Turkey).

Regarding GW, Israel (−0.42), Taiwan (−0.39), and Japan (−0.22) have low average scores whereas Malta (0.85), South Africa (0.58), and Sweden (0.56) have high average scores. The gap between developed and developing countries is less clear when it comes to GW levels. For example, the average GW value in a high-ESG country like Sweden is high, while the average GW value in a low-ESG country like the USA is low.

The lower part of the table reveals that, in general, ESG scores in HVA countries are higher than in LVA countries. However, GW does not exhibit this clear pattern (median values have a slight difference, but averages have less). This signals that GW practices do not really depend on the standards of freedom or participation in certain countries.

4.2. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF)

Table 3 gives the VIF values for the ESG-ROA and GW-ROA model specifications shown in Equation (1). Accordingly, the highest VIF score is 3.66. A check for all the regressions shows that the highest score is 3.8, which is considerably lower than the critical value. Therefore, we do not expect any multicollinearity problems in the regressions.

Table 3.

VIF results for the ESG-ROA and GW-ROA models (2020–2021).

4.3. Panel Regressions

4.3.1. FE Difference-in-Difference Results on the Direct Effect of ESG (Alternatively E, S, and G) and Greenwashing (GW) on Profitability

Table 4 presents the results of the analyses conducted to test hypotheses H1a and H1b (for ROA and TQ, respectively). Accordingly, β1 is positive and significant in all the models (with ROA or TQ as the dependent variable for the impact of 2020 scores on 2021 or 2022 results), except for the governance score’s impact on ROA in 2022 (in the last column). Considering the regression coefficients (Treat × Post), companies with higher ESG scores during the COVID-19 period (2020) achieved an average of 0.005 (0.004) units more operational performance (ROA) in 2021 (2022) and an average of 0.288 (0.299) units more market value (TQ) in 2021 (2022) compared to companies with lower ESG scores. Looking at the results for ROA, the coefficients for the subscores exhibit very similar patterns (they are all positive and mostly significant), the coefficient of E usually being higher than S and G (e.g., 0.007 vs. 0.005 for 2021). We also notice that significance is slightly higher for the impact on the 2021 results compared to the 2022 results. When TQ is chosen to show profitability, the significance and coefficients are very close to each other for the years 2021 and 2022, but there are differences among subscores. E is the subscore with the highest coefficient (0.343), followed by G (0.260), and S (0.166) for 2021. Thus, we infer that firms with high ESG (or E, S, and G) scores during the crisis period had higher profitability measured by ROA and TQ in the post-crisis period than firms with low ESG (or E, S and G) scores. These findings strongly support H1a and H1b and demonstrate that, while costly, ESG investment contributed to the post-COVID-19 operational performance and market value. Moreover, those who increased their E score during the crisis experienced a higher increase in their ROA and TQ after the crisis in comparison to S and G. The coefficients are low but significant.

Table 4.

FE difference-in-difference estimation results: Comparison of the COVID-19 period (2020) with 2021 and 2022 regarding the direct effect of ESG (alternatively, E, S, and G) on ROA and TQ.

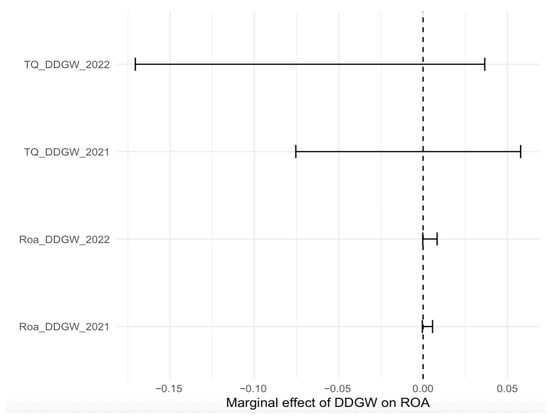

Table 5 presents the results of the analyses conducted to test hypotheses H2a and H2b (for ROA and TQ, respectively). Accordingly, β1 is positive and weakly significant (at 10%) in models with ROA (for both 2021 and 2022), but insignificant in models with TQ. Considering the regression coefficients (Treat × Post), companies with higher GW score during the COVID-19 period (2020) achieved an average of 0.003 (0.004) units more operational performance (ROA) in 2021 (2022). The low marginal effects and their confidence intervals can also be observed in Figure 1. These findings do not support H2a or H2b.

Table 5.

FE difference-in-difference estimation results: Comparison of the COVID-19 period (2020) with 2021 and 2022 regarding the direct effect of GW on ROA and TQ.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the COVID-19 period (2020) with 2021 and 2022 regarding the marginal effect of GW on ROA and TQ.

4.3.2. FE Difference-in-Difference Estimation Results on the Indirect Effects of ESG (Alternatively, E, S, and G) and Greenwashing (GW) on Profitability in Developed and Developing Countries

Table 6 presents the results of the analyses conducted to test hypotheses H3a and H3b (for ROA and TQ, respectively). Accordingly, β3 is mostly positive and partially significant in various models (with ROA or TQ as the dependent variable for the impact of 2020 scores on 2021 or 2022 results). Considering the regression coefficients (Treat × Post × DEV), companies in developed countries with high ESG scores during the COVID-19 period (2020) achieved an average of 0.005 (0.004) units more operational performance (ROA) in 2021 (2022) and an average of 0.188 (0.070) units more market value (TQ) in 2021 (2022), compared to companies in developing countries with high ESG scores (though the last figure for TQ in 2022 is insignificant). Looking at the results for ROA, the coefficients for subscores exhibit similar patterns (they are all positive, but partially significant), the coefficients of E and G usually being higher and more significant than S (e.g., 0.006 vs. 0.002 for 2021). We also notice that the significance is slightly higher for the impact on 2021 results compared to 2022 results, except for S. When TQ is chosen to show profitability, the significance and coefficients are close to each other for the year 2021 for ESG and different subscores, but less so for year 2022, and there are marked differences among subscores. E is the subscore with the highest coefficient (0.244), followed by G (0.132) and S (0.129) for 2021. Thus, we infer that firms in developed countries with high ESG (or E, S, and G) scores during the crisis period had higher profitability measured by ROA and TQ in the post-crisis period than firms in developing countries with high ESG (or E, S, and G) scores. These findings generally support H3a and H3b and demonstrate that ESG investment contributed to the post-COVID-19 operational performance and market value more in developed countries than in developing countries, and more prominently in the first year following COVID-19 (2021).

Table 6.

FE difference-in-difference estimation results: Comparison of the COVID-19 period (2020) with 2021 and 2022 regarding the indirect effect of ESG (alternatively, E, S, and G) on ROA and TQ with DEV as a secondary moderator.

Table 7 presents the results of the analyses conducted to test hypotheses H4a and H4b (for ROA and TQ, respectively). Accordingly, β3 is mostly positive and partially significant in various models (with ROA or TQ as the dependent variable for the impact of 2020 scores on 2021 or 2022 results). Considering the regression coefficients (Treat × Post × DEV), companies in developed countries with high GW scores during the COVID-19 period (2020) achieved an average of 0.005 (0.004) units more operational performance (ROA) in 2021 (2022) and an average of 0.278 (0.231) units more market value (TQ) in 2021 (2022) compared to companies in developing countries with high GW (though the evidence remains particularly weak for ROA). Moreover, for both ROA and TQ, the coefficients are slightly higher and more significant for the one-year impact (on 2021 results) than the two-year impact (on 2022 results). Thus, we infer that firms in developed countries with high GW during the crisis period had higher profitability measured by ROA and TQ in the post-crisis period than firms in developing countries with high GW. These findings partially support H4a and strongly support H4b, and demonstrate that practicing GW contributed to the post-COVID-19 operational performance and market value more in developed countries than in developing countries, and more prominently in the first year following COVID-19 (2021).

Table 7.

FE difference-in-difference estimation results: Comparison of the COVID-19 period (2020) with 2021 and 2022 regarding the indirect effect of GW on ROA and TQ with DEV as a secondary moderator.

4.3.3. FE Difference-in-Difference Estimation Results on the Indirect Effects of ESG (Alternatively, E, S, and G) and Greenwashing (GW) on Profitability in High V&A and Low V&A Countries

Table 8 presents the results of the analyses conducted to test hypotheses H5a and H5b (for ROA and TQ, respectively). Accordingly, β3 is positive and significant in all the models (with ROA or TQ as the dependent variable for the impact of 2020 scores on 2021 or 2022 results). Considering the regression coefficients (Treat × Post × DEV), companies in high voice and accountability (HVA) countries with high ESG scores during the COVID-19 period (2020) achieved an average of 0.014 (0.009) units more operational performance (ROA) in 2021 (2022) and an average of 0.381 (0.198) units more market value (TQ) in 2021 (2022), compared to companies in low voice and accountability (LVA) countries with high ESG scores. Looking at the results for ROA, the coefficients for the subscores exhibit very similar patterns (they are all positive and significant), the coefficients of E being slightly higher than S and G (e.g., 0.015 vs. 0.013 for 2021). When TQ is chosen to show profitability, the significance and coefficients across ESG and subscores are close to each other for the year 2021 (as well as 2022), yet both are higher for the year 2021 than for 2022. E and S are the subscores with the high coefficients (0.394 and 0.377, respectively), followed by G (0.276), for 2021. Thus, we infer that firms in HVA countries with high ESG (or E, S, and G) scores during the crisis period had higher profitability measured by ROA and TQ in the post-crisis period than firms in LVA countries with high ESG (or E, S, and G) scores. These findings strongly support both H5a and H5b and demonstrate that ESG investment contributed to the post-COVID-19 operational performance and market value more in HVA countries than in LVA countries, and more prominently in the first year following COVID-19 (2021).

Table 8.

FE difference-in-difference estimation results: Comparison of the COVID-19 period (2020) with 2021 and 2022 regarding the indirect effect of ESG (alternatively, E, S, and G) on ROA and TQ with HVA as a secondary moderator.

Table 9 presents the results of the analyses conducted to test hypotheses H6a and H6b (for ROA and TQ, respectively). Accordingly, β3 is mostly positive and partially significant in various models (with ROA or TQ as the dependent variable for the impact of 2020 scores on 2021 or 2022 results). Considering the regression coefficients (Treat × Post × DEV), companies in high voice and accountability (HVA) countries with a high GW score during the COVID-19 period (2020) achieved an average of 0.009 (0.004) units more operational performance (ROA) in 2021 (2022) and an average of 0.324 (0.178) units more market value (TQ) in 2021 (2022) compared to companies in low voice and accountability (LVA) countries with high GW (though the evidence remains particularly weak for 2022). Moreover, for both ROA and TQ, the coefficients are markedly higher and more significant for the one-year impact (on 2021 results) than the two-year impact (on 2022 results). Thus, we infer that firms in HVA countries with high GW during the crisis period had higher profitability measured by ROA and TQ in the post-crisis period than firms in LVA countries with high GW. These findings partially support H6a and strongly support H6b, and demonstrate that practicing GW contributed to the post-COVID-19 operational performance and market value more in HVA countries than in LVA countries, and more prominently in the first year following COVID-19 (2021).

Table 9.

FE difference-in-difference estimation results: Comparison of the COVID-19 period (2020) with 2021 and 2022 regarding the indirect effect of GW on ROA and TQ with HVA as a secondary moderator.

A comparison between Table 6 and Table 8 reveals that all the β3 coefficients in Table 6 are higher and usually more significant than their peers in Table 8. This suggests that a grouping of countries based on voice and accountability might better explain profitability than a grouping based on economic development when ESG (alternatively, E, S, and G) is the main independent variable. A similar comparison between Table 7 and Table 9 reveals the same finding for the impact of GW on 2021 profitability, but not on 2022 profitability.

4.3.4. Recovery Period: FE Difference-in-Difference Estimation Results on the Indirect Effects of ESG (Alternatively, E, S, and G) and Greenwashing (GW) on Profitability in Developed and Developing Countries (Alternatively, in High and Low V&A Countries)

Table 10 presents the results of the analyses conducted to test hypotheses H7a and H7b (for ROA and TQ, respectively). Accordingly, β3 is mostly negative and partially significant in various models (with ROA or TQ as the dependent variable for the impact of 2021 scores on 2022 results). Looking at the results for ROA, the coefficients for ESG as well as the subscores are all insignificant and mostly negative for both the model with DEV and the model with HVA. When TQ is chosen to show profitability, coefficients are again mostly negative and some become significant. For example, in the model with DEV (HVA), the coefficients of ESG and S are −0.240 and −0.283 (−0.305 and −0.329) and strongly significant. For other subscores, significance remains considerably low. These findings do not support H7a, but support H7b (the latter for ESG and S, but not for E and G) and demonstrate that ESG investment during the recovery period did not contribute very much to the subsequent year’s operational performance, but contributed to market value, more in developing (or low voice and accountability) countries than in developed (high voice and accountability) countries.

Table 10.

FE difference-in-difference estimation results for the recovery period: Comparison of the post-COVID-19 period (2021) with 2022 regarding the indirect effect of ESG (alternatively, E, S, and G) on ROA and TQ with DEV (alternatively, HVA) as a secondary moderator.

Table 11 presents the results of the analyses conducted to test hypotheses H8a and H8b (for ROA and TQ, respectively). Accordingly, β3 is insignificant in all the models (with ROA or TQ as the dependent variable for the impact of 2021 scores on 2022 results). These findings do not support H8a or H8b, and demonstrate that practicing GW in the recovery period did not contribute to the subsequent year’s operational performance or market value more in developing (or low voice and accountability) countries than in developed (high voice and accountability) countries.

Table 11.

FE difference-in-difference estimation results for the recovery period: Comparison of the post-COVID-19 period (2021) with 2022 regarding the indirect effect of GW on ROA and TQ with DEV (alternatively, HVA) as a secondary moderator.

4.3.5. Summary Results

Table 12 summarizes the results by giving the hypothesis number; relevant model; dependent, independent, and moderator variables in this model; expected sign for the moderator; whether the hypothesis is supported; and the location in terms of table number.

Table 12.

Summary of the hypotheses and empirical support.

4.3.6. Robustness

We test the robustness of the findings in several ways. Explained in more detail below, these consist of using an alternative dependent variable of market value and re-estimating the models excluding any insignificant control variables upon assessing the significance of each.

First, we make an alternative specification for the dependent variable Tobin’s Q (TQ) and define it as market capitalization summed with total liabilities and divided by total assets. When regressions are run with this new measure, coefficient signs and significances are mostly consistent with the previous findings, while their magnitudes are occasionally larger.

Secondly, we reevaluate all the control variables in the models in terms of their significance and consider whether they increase the model power. Consequently, we find that only the firm age variable (LAGE) in the GW model slightly decreases the model power, in spite of its strong relevance in the literature. By re-estimating the GW model without LAGE, we find that results remain consistent in sign and magnitude, thereby confirming that the main findings are not sensitive to the inclusion of this variable.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Key Findings

This study provides a new perspective to the literature on the sustainability–finance interaction by examining the relationship between sustainability practices and profitability with a special focus on a particular crisis period (COVID-19). In this context, we analyze this relationship using data from 47 different stock exchanges over the 2020–2022 period, with up to 14,652 firm-year observations depending on the specification. We mainly investigate the impact of ESG score and its subscores (E, S, and G) as well as greenwashing (GW) on return on assets (ROA) and Tobin’s Q (TQ) based on difference-in-differences (DID) regressions. The results reveal the effects of sustainability practices on short- and long-term profitability, as well as the different dynamics observed during and after the crisis. Although existing studies have examined the relationship between certain sustainability practices (mostly for ESG and its subscores) and post-crisis profitability, the roles of economic development and public governance (apparent by voice and accountability) in shaping this profitability remain relatively unexplored. Motivated by this gap, we perform an empirical analysis on a large global dataset. Our findings provide important clues by explaining the impact of sustainability practices on post-crisis profitability through the mechanisms associated with country-specific dynamics (economic development and public governance), complemented by firm-level dynamics.

The first notable result (without differentiating by country groups) is that firms with a higher ESG score increased their operational performance and market value in the post-crisis period more than those with a lower ESG score. In this respect, our findings coincide with the findings of [29], who find similar results, but for a limited sample (banking sector). Moreover, this positive effect holds not only for the first year after the crisis (2021), but also for the second year (2022). This result aligns with crisis theory, which posits that businesses are better positioned to recover from downturns when they concentrate on strengthening their organizational reputation and social legitimacy in those periods by developing a trust-based communication with stakeholders and managing their sustainability investments effectively [2,95]. It also confirms that organizational reputation and social legitimacy [35,36] may influence the extent to which firms with high ESG enhance post-crisis profitability, and the persistence of this effect in 2022 further corroborates this view. This probably stems from the fact that positive returns of corporate reputation and social legitimacy are likely to persist [37], with increased investor confidence and strengthened image [39]. Since firms gradually generate these positive outcomes by continuously layering their valuable activities over time, such intangible assets cannot be acquired immediately. Hence, supporting [55,100], this study confirms that it is necessary to examine lagged effects in order to properly assess the ESG–profitability relationship.

As for the ESG sub-dimensions, considering the increased stakeholder interest in ESG, it is not surprising that each sub-dimension had a direct positive impact on post-crisis profitability. In addition, among the subscores, E exhibits the highest correlation with profitability and the post-COVID-19 effect of E on both operational performance and market value is the most noticeable. Two potential reasons for this outcome are as follows. First, the descriptive statistics show that E scores are on an upward trend compared to S and G, but remained lower than S and G during the crisis period. This could mean that businesses are more likely to be rewarded for successfully implementing their realistic environmental pledges. Secondly, during the COVID-19 period, stakeholders started to pay more attention to environmental issues [41] and allocated more funds to green investments as part of post-COVID-19 recovery policies (EU: “Green Deal”, US: “Green Recovery”). COVID-19 was expected to trigger a green recovery and the protection of the environment was a priority [31]. Therefore, stakeholders might have placed greater emphasis on E-related issues than on S- and G-related ones.

This corresponds with the argument of the availability heuristic bias [42], which holds that recent experiences (e.g., the pandemic) may have made some initiatives (e.g., environmental issues) more accessible, which leads stakeholders to assign disproportionately higher values to these initiatives. One possible explanation is that the availability bias may have shaped stakeholder behavior in this context, thereby magnifying the extent to which high E exerted a stronger effect on profitability than high S and G during the crisis period.

Unexpectedly, firms which were more engaged in GW during the crisis increased their ROA afterwards. This result contrasts with [75], and contrary to [47], supports the view that strict regulations with sanctions were limited or ineffective. With this finding, we partially support [75] in that companies need to communicate about their environmental commitments (“negative effects of brownwashing on profits”) to some extent, even after crisis periods. Nevertheless, it should be noted that we also find mixed results for operational performance and market value in terms of post-crisis profitability. Specifically, although statistically insignificant, after controlling for the marginal effects in Figure 1, we observe that high GW during crisis could also lead to substantial declines in post-crisis market value, a pattern that became more pronounced in the long run (2022). The lack of a significantly positive effect, as observed for ROA, is also consistent with—and partially supportive of—this view, which argues that stakeholder priorities and reactions are clearly visible in the GW–profitability relationship [45,46], especially in the long run with reputational risks [33]. The fact that this effect becomes insignificant particularly for market value indicates that GW is a potentially reaction-eliciting practice, especially in the long run.

As for country effects, our results confirm that ESG can have different impacts on profitability depending on economic development, supporting [101]. We find that firms in developed countries with high ESG scores during the crisis period had higher profitability in the post-crisis period than firms in developing countries with high ESG scores. The same results hold for the subscores (E, S, and G). This evidence may plausibly support the argument that stakeholders in developed countries are more likely to prioritize sustainability issues and more willing to pay for ESG issues [52], while stakeholders in developing countries are more likely to focus on economic survival and short-term profitability [51], especially in crisis periods.

During COVID-19, many companies experienced financial difficulties and were unable to survive, more prominently so in developing economies [4,38]. According to slack resources theory, when resources are limited, managers face trade-offs [59]. Because of the trade-offs, the marginal benefit of sustainability practices on profitability may be more weakened in developing countries than in developed countries. A complementary view supporting our findings is offered by signaling theory, which argues that not all ESG signals are interpreted equally [60]; ESG credibility depends on the institutional ecosystem in which they are issued. Given that credibility plays a central role in influencing stakeholders’ valuations, signaling theory provides additional support for our findings. Thus, drawing on the theoretical justifications provided by slack resources and signaling theories, we confirm that economic development significantly influences the relationship between ESG (alternatively E, S, and G) and post-crisis profitability.

In general, companies in developed countries that focused on the E, G, and S subscores achieved better profitability after COVID-19. Our results support the view that, during the COVID-19 period, stakeholders—especially investors in developed economies—placed greater emphasis on, and more strongly rewarded, environmental performance. According to [38], during COVID-19, developing-country firms showed greater interest in S and G topics—such as employee health, stakeholder support, and transparency—than in E topics. Moreover, the strong emphasis placed on E-related issues in developed countries may be attributed to the comparatively stronger social and technological infrastructure which they possess. As shown in Figure 1, although firms in developing countries achieved much higher E scores during the COVID-19 period, companies in developed countries attained higher levels of post-crisis profitability. Ultimately, this finding requires further research.

As for the GW–profitability relationship across developed and developing countries, we find that firms with high GW in developed countries generally obtained a higher post-crisis profitability than those in developing countries. This outcome contrasts with the view that public awareness, pressure, and lawsuits were more pronounced in developed economies, and therefore GW practices during COVID-19 would have been more penalized by the public than in developing economies. Because stakeholder pressure is higher on companies in developed countries, firms in developing contexts may consequently display higher GW values [38]. Thus, the losses in legitimacy observed during COVID-19 may manifest more prominently in developing countries in the subsequent period, despite developed countries exhibiting higher levels of established legal systems and institutional infrastructures that may impose greater penalties on GW. This result might stem from the stronger corporate governance in developed-country firms which disguises their window dressing. Indeed, companies in developed countries might have turned the crisis into an opportunity despite strong regulatory pressures (e.g., the rise of GW in 2020 and the implementation of the EU taxonomy in July 2020). More specifically, companies in developed countries may have improved their post-crisis profitability because they better managed GW (e.g., complying with some regulations while avoiding others). GW practices in developed countries are managed in a way that does not provoke stakeholder backlash, even though there is more public pressure therein. In developed-country firms, GW practices seem to have worked better and increased visibility more without harming image. In other words, companies in developed countries might have masked their GW practices by highlighting the areas they wish to signal, as suggested by signaling theory [60]. In summary, it seems that, even during a crisis period, strict policies against GW practices may not prevent firms performing GW and obtaining higher profitability and market value afterwards.